CS 252 Graduate Computer Architecture Lecture 16 Cache

![12. Reducing Misses by Compiler Optimizations • Mc. Farling [1989] reduced caches misses by 12. Reducing Misses by Compiler Optimizations • Mc. Farling [1989] reduced caches misses by](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/f911bb85d7f4f70fec054fa4283a1e6d/image-17.jpg)

![Merging Arrays Example /* Before: 2 sequential arrays */ int val[SIZE]; int key[SIZE]; /* Merging Arrays Example /* Before: 2 sequential arrays */ int val[SIZE]; int key[SIZE]; /*](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/f911bb85d7f4f70fec054fa4283a1e6d/image-18.jpg)

![Sparse Matrix – Search for Blocking for finite element problem [Im, Yelick, Vuduc, 2005] Sparse Matrix – Search for Blocking for finite element problem [Im, Yelick, Vuduc, 2005]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/f911bb85d7f4f70fec054fa4283a1e6d/image-26.jpg)

![Avoiding Bank Conflicts • Lots of banks int x[256][512]; for (j = 0; j Avoiding Bank Conflicts • Lots of banks int x[256][512]; for (j = 0; j](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/f911bb85d7f4f70fec054fa4283a1e6d/image-51.jpg)

- Slides: 62

CS 252 Graduate Computer Architecture Lecture 16 Cache Optimizations (Con’t) Memory Technology John Kubiatowicz Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences University of California, Berkeley http: //www. eecs. berkeley. edu/~kubitron/cs 252 http: //www inst. eecs. berkeley. edu/~cs 252

Review: Cache performance • Miss oriented Approach to Memory Access: • Separating out Memory component entirely – AMAT = Average Memory Access Time 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 2

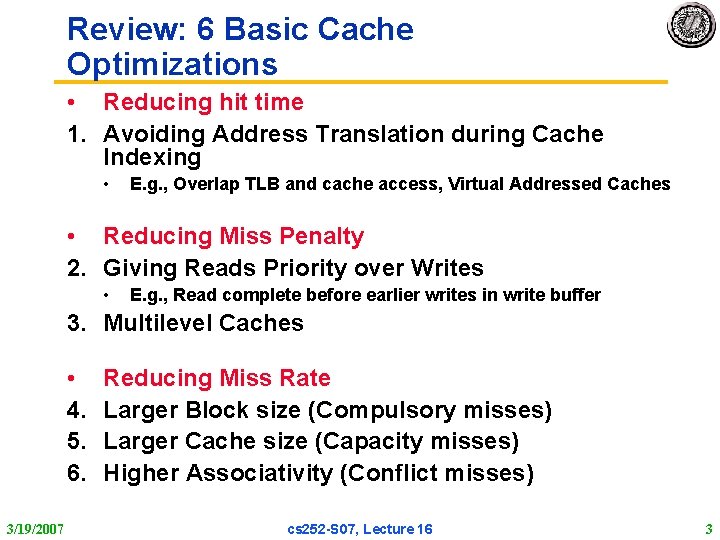

Review: 6 Basic Cache Optimizations • Reducing hit time 1. Avoiding Address Translation during Cache Indexing • E. g. , Overlap TLB and cache access, Virtual Addressed Caches • Reducing Miss Penalty 2. Giving Reads Priority over Writes • E. g. , Read complete before earlier writes in write buffer 3. Multilevel Caches • 4. 5. 6. 3/19/2007 Reducing Miss Rate Larger Block size (Compulsory misses) Larger Cache size (Capacity misses) Higher Associativity (Conflict misses) cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 3

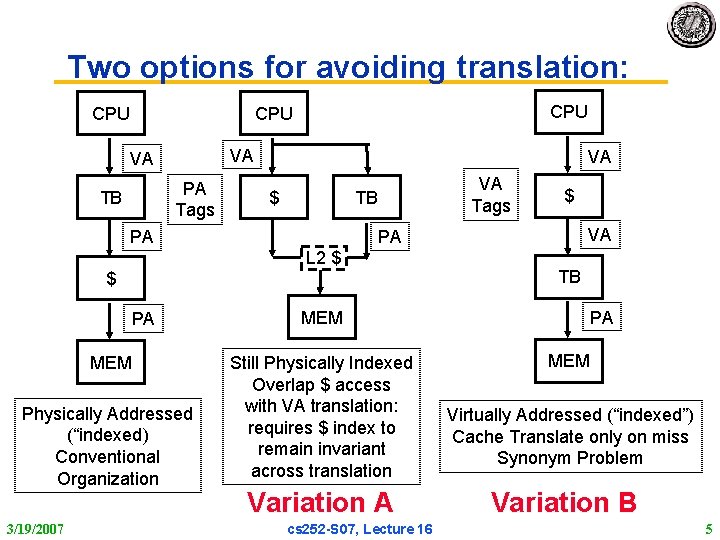

1. Fast hits by Avoiding Address Translation • Send virtual address to cache? Called Virtually Addressed Cache or just Virtual Cache vs. Physical Cache – Every time process is switched logically must flush the cache; otherwise get false hits » Cost is time to flush + “compulsory” misses from empty cache – Dealing with aliases (sometimes called synonyms); Two different virtual addresses map to same physical address – I/O must interact with cache, so need virtual address • Solution to aliases – HW guaranteess covers index field & direct mapped, they must be unique; called page coloring • Solution to cache flush – Add process identifier tag that identifies process as well as address within process: can’t get a hit if wrong process 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 4

Two options for avoiding translation: CPU CPU VA VA PA Tags TB VA $ VA Tags TB PA $ MEM Physically Addressed (“indexed) Conventional Organization 3/19/2007 VA PA L 2 $ PA $ MEM Still Physically Indexed Overlap $ access with VA translation: requires $ index to remain invariant across translation Variation A cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 TB PA MEM Virtually Addressed (“indexed”) Cache Translate only on miss Synonym Problem Variation B 5

3. Multi level cache • L 2 Equations AMAT = Hit Time. L 1 + Miss Rate. L 1 x Miss Penalty. L 1 = Hit Time. L 2 + Miss Rate. L 2 x Miss Penalty. L 2 AMAT = Hit Time. L 1 + Miss Rate. L 1 x (Hit Time. L 2 + Miss Rate. L 2 + Miss Penalty. L 2) • Definitions: – Local miss rate— misses in this cache divided by the total number of memory accesses to this cache (Miss rate. L 2) – Global miss rate—misses in this cache divided by the total number of memory accesses generated by the CPU (Miss Rate. L 1 x Miss Rate. L 2) – Global Miss Rate is what matters 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 6

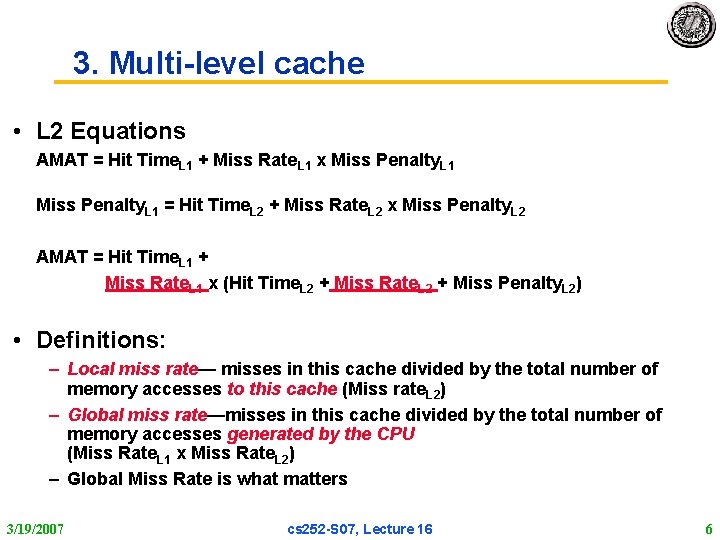

Review: (Con’t) 12 Advanced Cache Optimizations • Reducing hit time 1. Small and simple caches 2. Way prediction 3. Trace caches • Reducing Miss Penalty 7. Critical word first 8. Merging write buffers • Increasing cache bandwidth 4. Pipelined caches 5. Multibanked caches 6. Nonblocking caches 3/19/2007 • Reducing Miss Rate 9. Victim Cache 10. Hardware prefetching 11. Compiler prefetching 12. Compiler Optimizations cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 7

4: Increasing Cache Bandwidth by Pipelining • Pipeline cache access to maintain bandwidth, but higher latency • Instruction cache access pipeline stages: 1: Pentium 2: Pentium Pro through Pentium III 4: Pentium 4 - greater penalty on mispredicted branches - more clock cycles between the issue of the load and the use of the data 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 8

5. Increasing Cache Bandwidth: Non Blocking Caches • Non-blocking cache or lockup-free cache allow data cache to continue to supply cache hits during a miss – requires F/E bits on registers or out of order execution – requires multi bank memories • “hit under miss” reduces the effective miss penalty by working during miss vs. ignoring CPU requests • “hit under multiple miss” or “miss under miss” may further lower the effective miss penalty by overlapping multiple misses – Significantly increases the complexity of the cache controller as there can be multiple outstanding memory accesses – Requires muliple memory banks (otherwise cannot support) – Penium Pro allows 4 outstanding memory misses 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 9

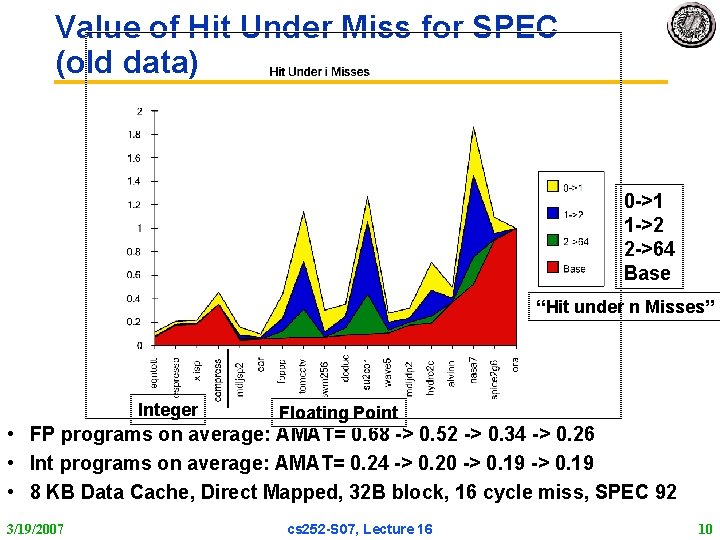

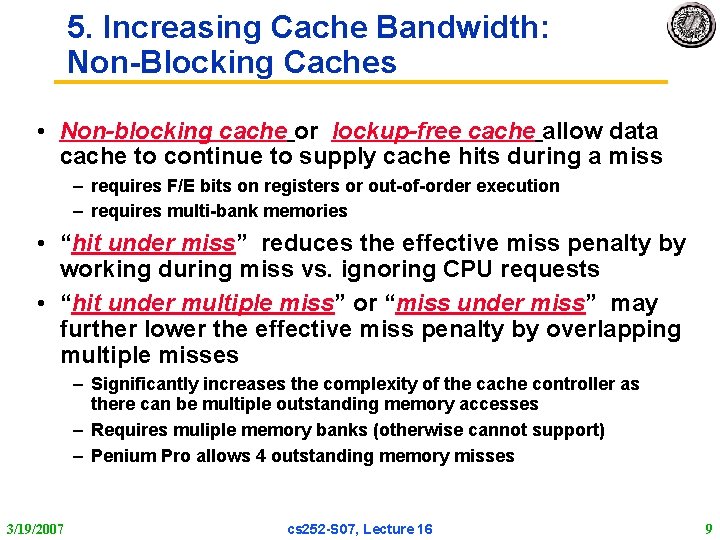

Value of Hit Under Miss for SPEC (old data) 0 >1 1 >2 2 >64 Base “Hit under n Misses” Integer Floating Point • FP programs on average: AMAT= 0. 68 > 0. 52 > 0. 34 > 0. 26 • Int programs on average: AMAT= 0. 24 > 0. 20 > 0. 19 • 8 KB Data Cache, Direct Mapped, 32 B block, 16 cycle miss, SPEC 92 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 10

6: Increasing Cache Bandwidth via Multiple Banks • Rather than treat the cache as a single monolithic block, divide into independent banks that can support simultaneous accesses – E. g. , T 1 (“Niagara”) L 2 has 4 banks • Banking works best when accesses naturally spread themselves across banks mapping of addresses to banks affects behavior of memory system • Simple mapping that works well is “sequential interleaving” – Spread block addresses sequentially across banks – E, g, if there 4 banks, Bank 0 has all blocks whose address modulo 4 is 0; bank 1 has all blocks whose address modulo 4 is 1; … 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 11

7. Reduce Miss Penalty: Early Restart and Critical Word First • Don’t wait for full block before restarting CPU • Early restart—As soon as the requested word of the block arrives, send it to the CPU and let the CPU continue execution – Spatial locality tend to want next sequential word, so not clear size of benefit of just early restart • Critical Word First—Request the missed word first from memory and send it to the CPU as soon as it arrives; let the CPU continue execution while filling the rest of the words in the block – Long blocks more popular today Critical Word 1 st Widely used block 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 12

8. Merging Write Buffer to Reduce Miss Penalty • • • 3/19/2007 Write buffer to allow processor to continue while waiting to write to memory If buffer contains modified blocks, the addresses can be checked to see if address of new data matches the address of a valid write buffer entry If so, new data are combined with that entry Increases block size of write for write through cache of writes to sequential words, bytes since multiword writes more efficient to memory The Sun T 1 (Niagara) processor, among many others, uses write merging cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 13

9. Reducing Misses: a “Victim Cache” • How to combine fast hit time of direct mapped yet still avoid conflict misses? • Add buffer to place data discarded from cache • Jouppi [1990]: 4 entry victim cache removed 20% to 95% of conflicts for a 4 KB direct mapped data cache • Used in Alpha, HP machines 3/19/2007 TAGS DATA Tag and Comparator One Cache line of Data cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 To Next Lower Level In Hierarchy 14

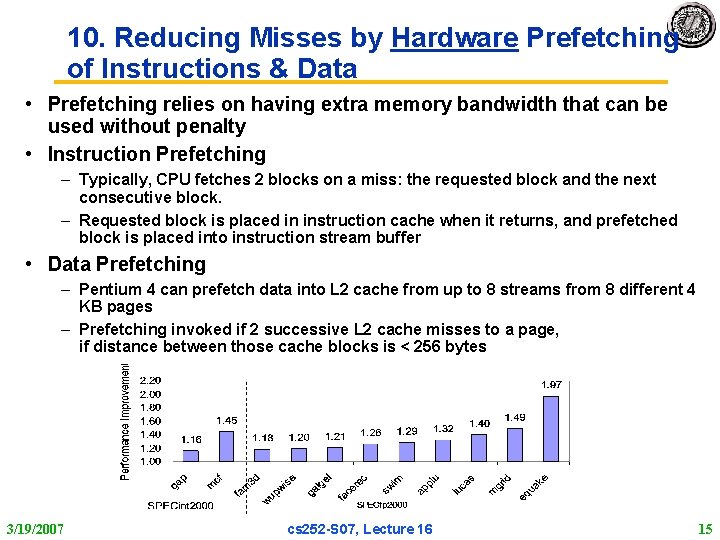

10. Reducing Misses by Hardware Prefetching of Instructions & Data • Prefetching relies on having extra memory bandwidth that can be used without penalty • Instruction Prefetching – Typically, CPU fetches 2 blocks on a miss: the requested block and the next consecutive block. – Requested block is placed in instruction cache when it returns, and prefetched block is placed into instruction stream buffer • Data Prefetching – Pentium 4 can prefetch data into L 2 cache from up to 8 streams from 8 different 4 KB pages – Prefetching invoked if 2 successive L 2 cache misses to a page, if distance between those cache blocks is < 256 bytes 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 15

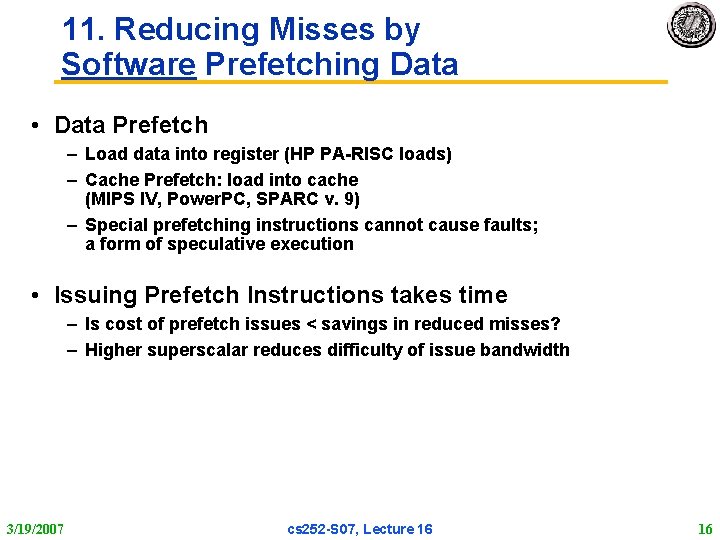

11. Reducing Misses by Software Prefetching Data • Data Prefetch – Load data into register (HP PA RISC loads) – Cache Prefetch: load into cache (MIPS IV, Power. PC, SPARC v. 9) – Special prefetching instructions cannot cause faults; a form of speculative execution • Issuing Prefetch Instructions takes time – Is cost of prefetch issues < savings in reduced misses? – Higher superscalar reduces difficulty of issue bandwidth 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 16

![12 Reducing Misses by Compiler Optimizations Mc Farling 1989 reduced caches misses by 12. Reducing Misses by Compiler Optimizations • Mc. Farling [1989] reduced caches misses by](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/f911bb85d7f4f70fec054fa4283a1e6d/image-17.jpg)

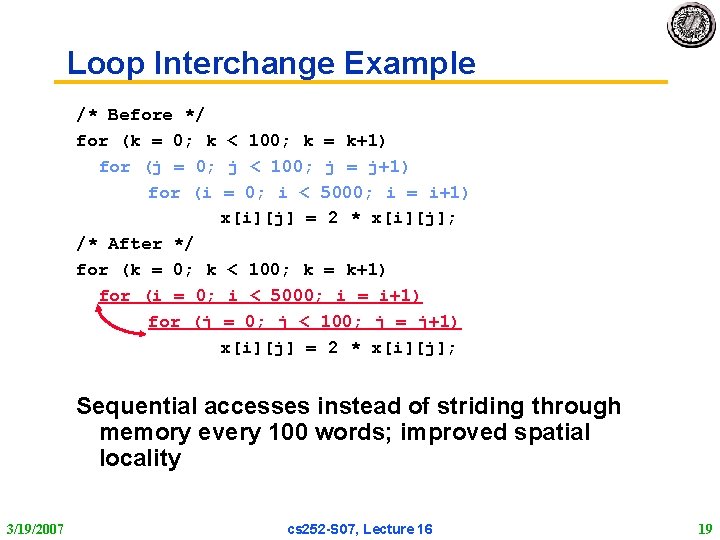

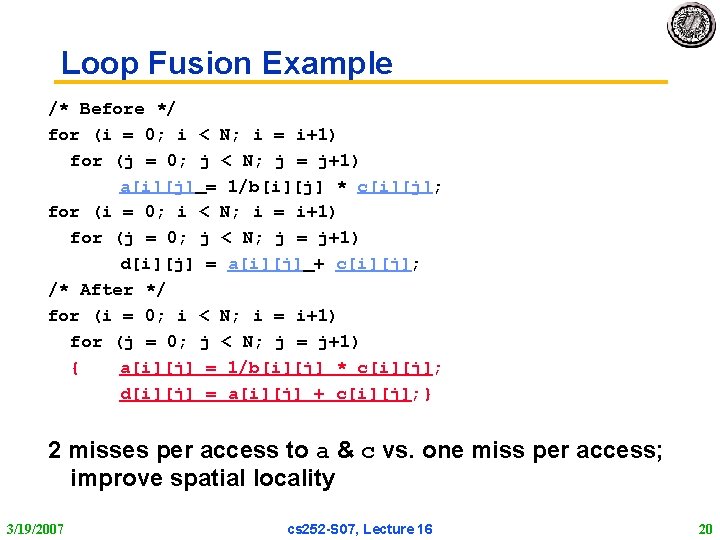

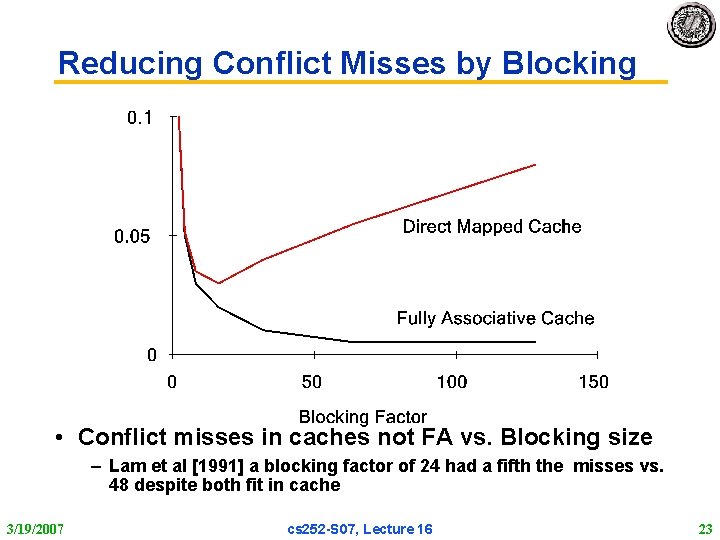

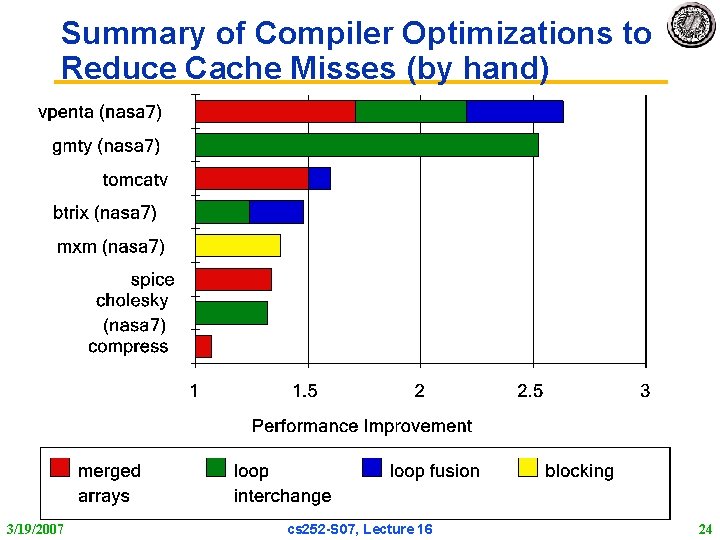

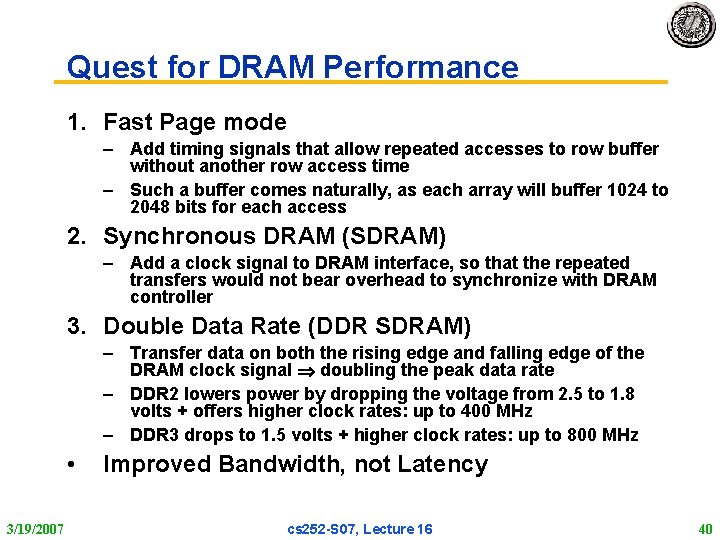

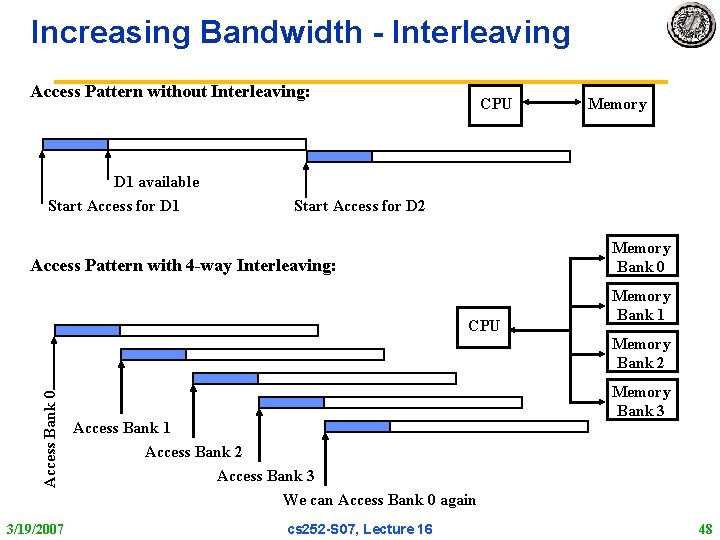

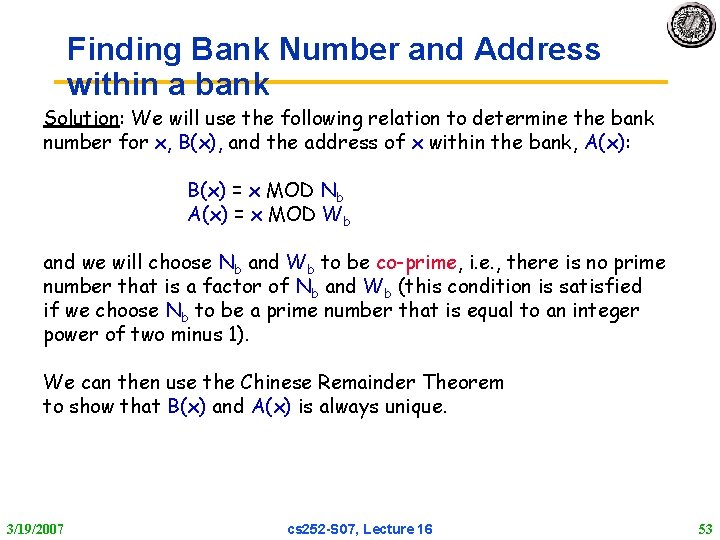

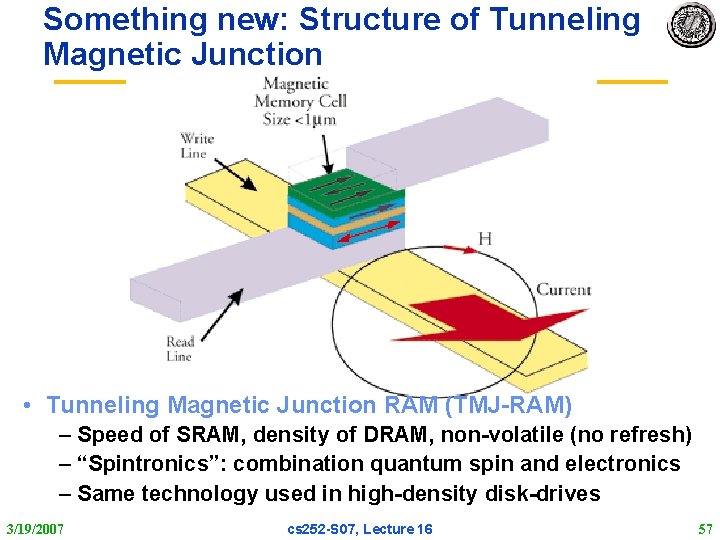

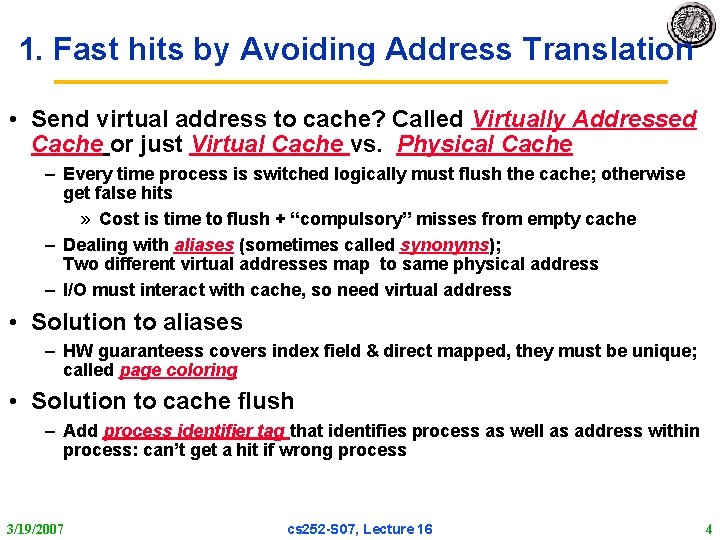

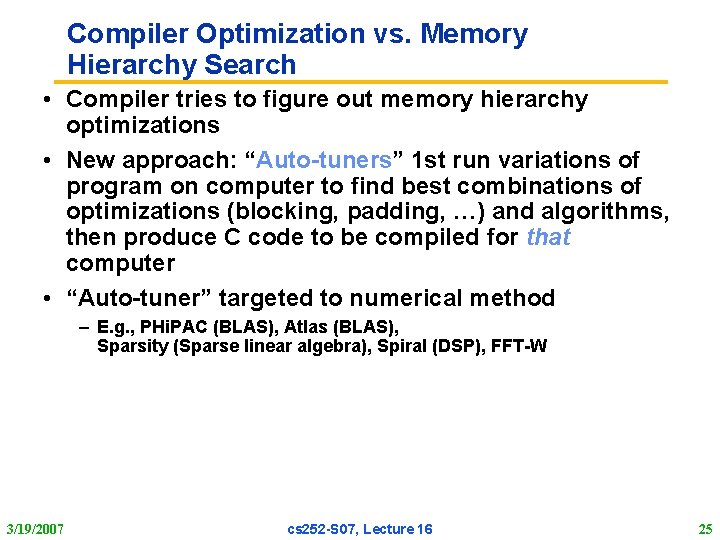

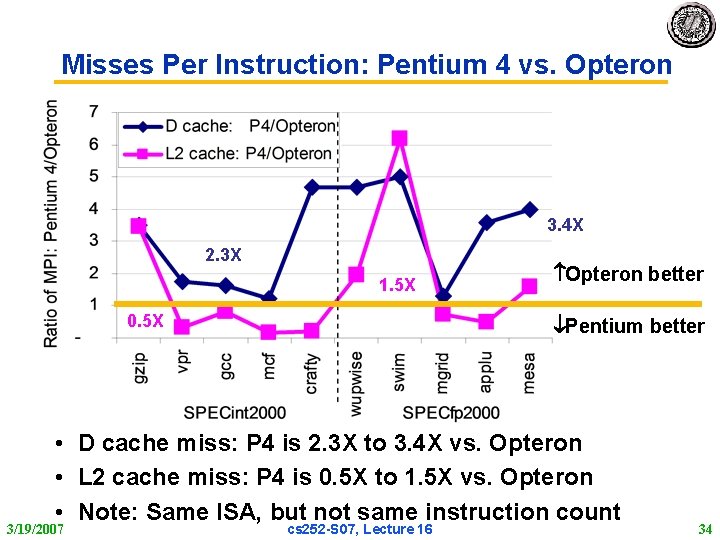

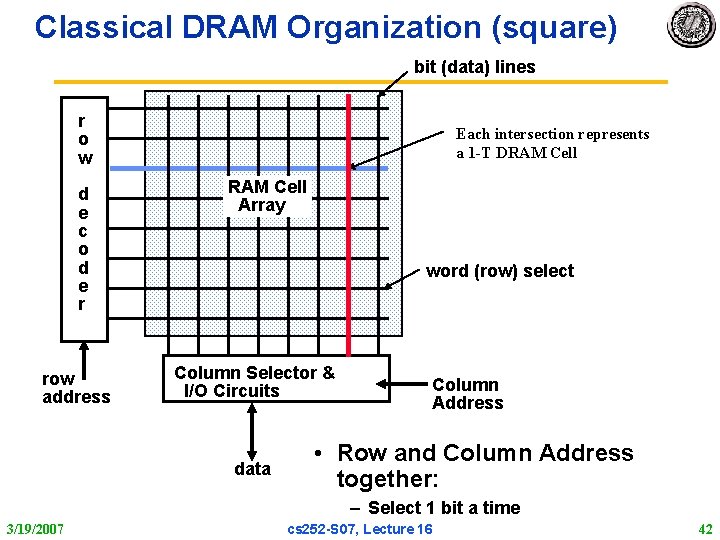

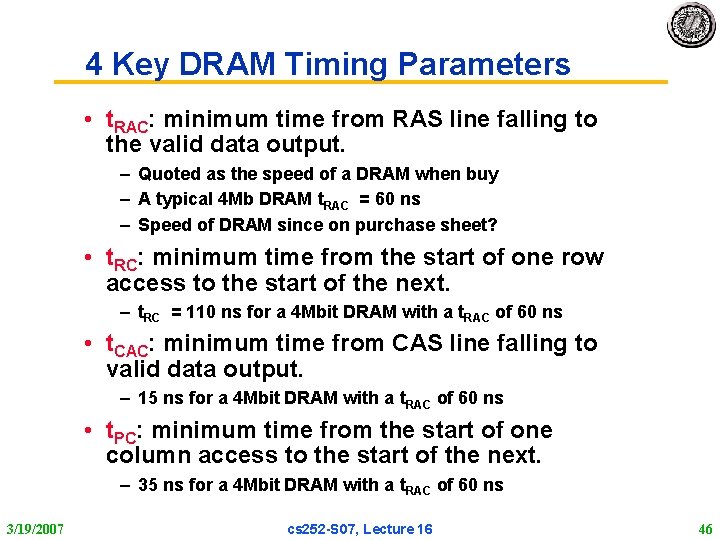

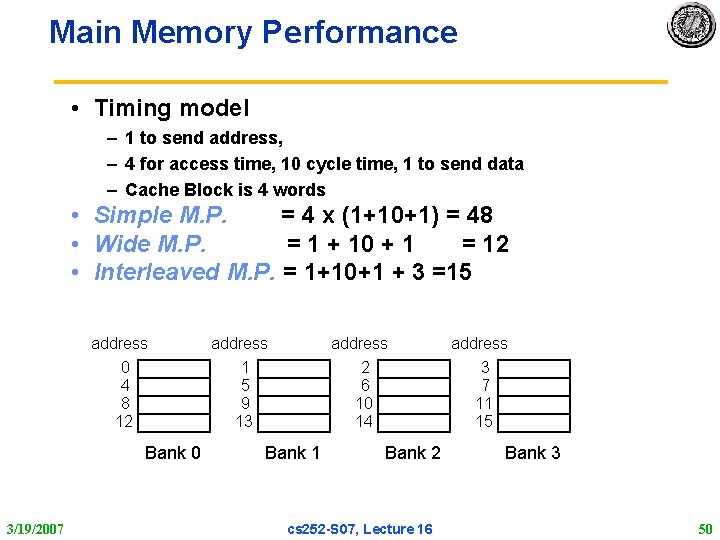

12. Reducing Misses by Compiler Optimizations • Mc. Farling [1989] reduced caches misses by 75% on 8 KB direct mapped cache, 4 byte blocks in software • Instructions – Reorder procedures in memory so as to reduce conflict misses – Profiling to look at conflicts(using tools they developed) • Data – Merging Arrays: improve spatial locality by single array of compound elements vs. 2 arrays – Loop Interchange: change nesting of loops to access data in order stored in memory – Loop Fusion: Combine 2 independent loops that have same looping and some variables overlap – Blocking: Improve temporal locality by accessing “blocks” of data repeatedly vs. going down whole columns or rows 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 17

![Merging Arrays Example Before 2 sequential arrays int valSIZE int keySIZE Merging Arrays Example /* Before: 2 sequential arrays */ int val[SIZE]; int key[SIZE]; /*](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/f911bb85d7f4f70fec054fa4283a1e6d/image-18.jpg)

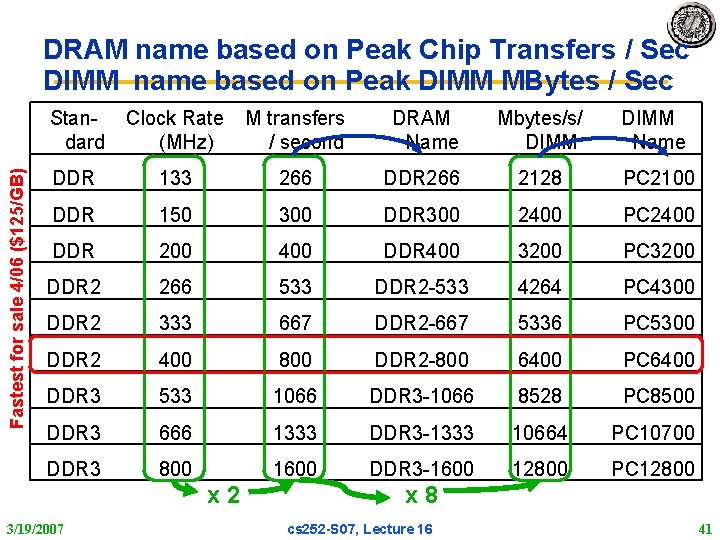

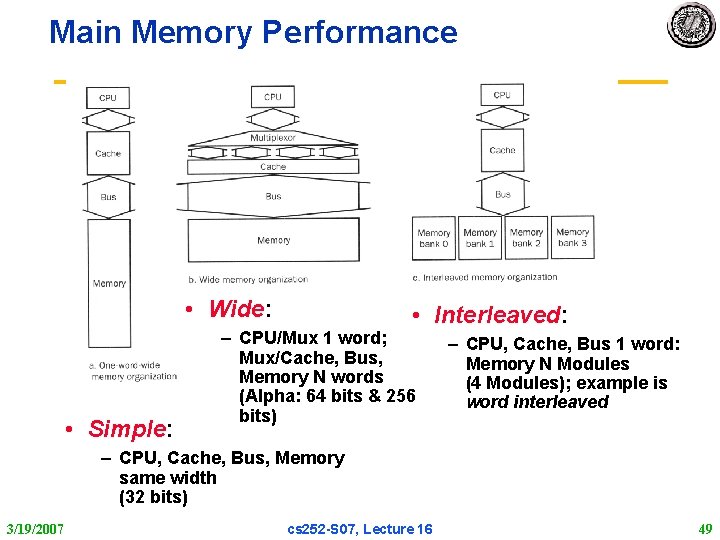

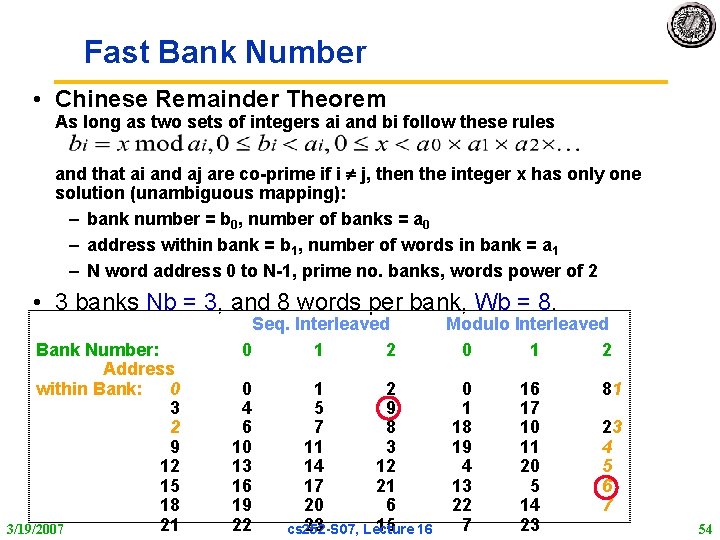

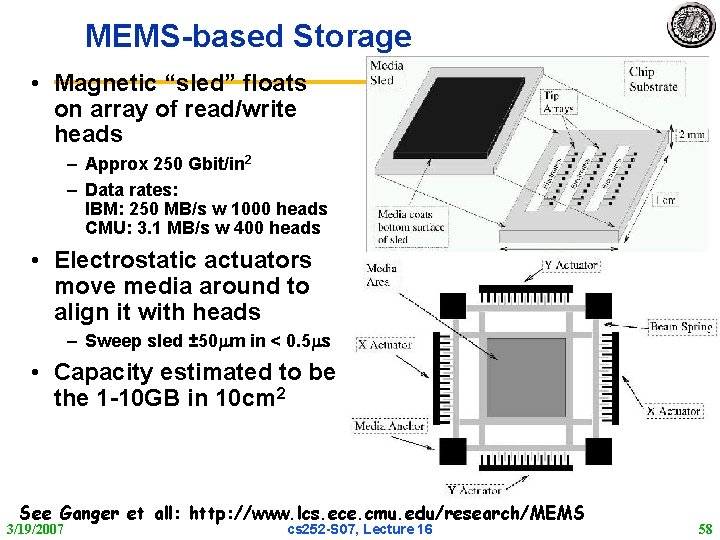

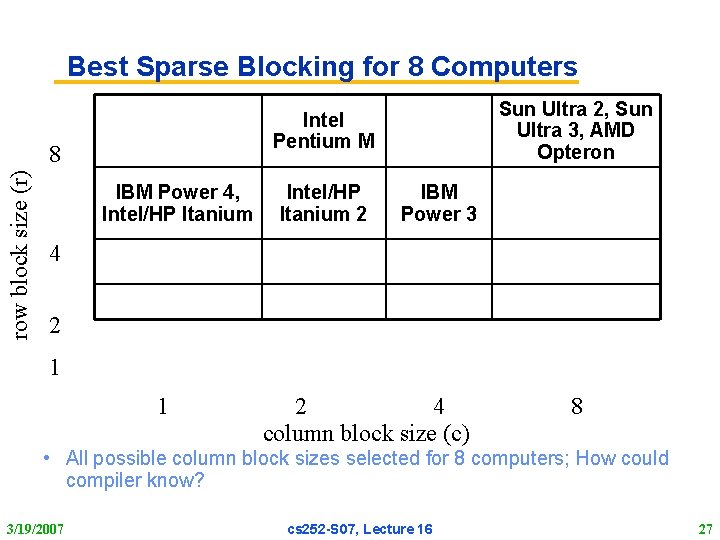

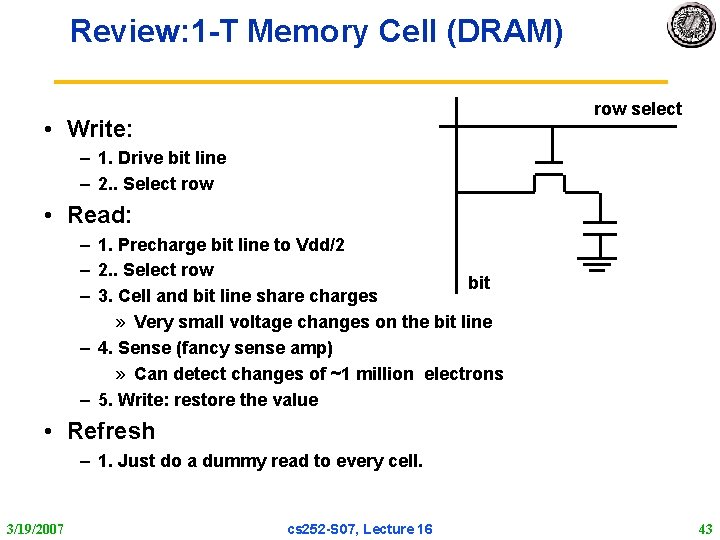

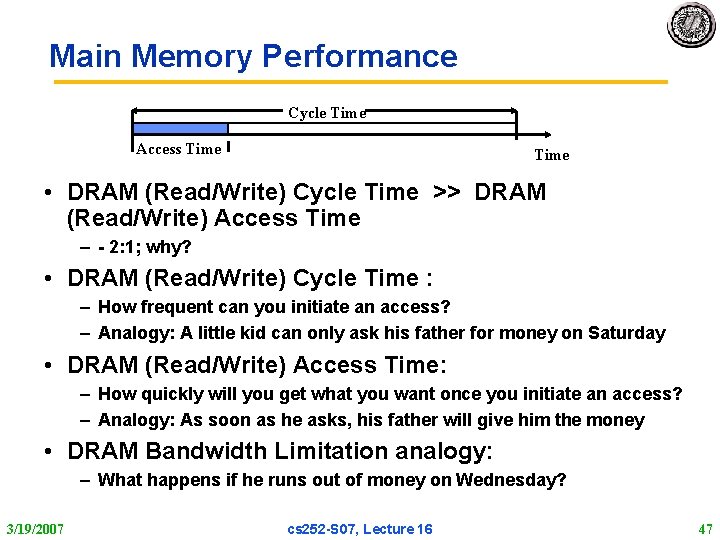

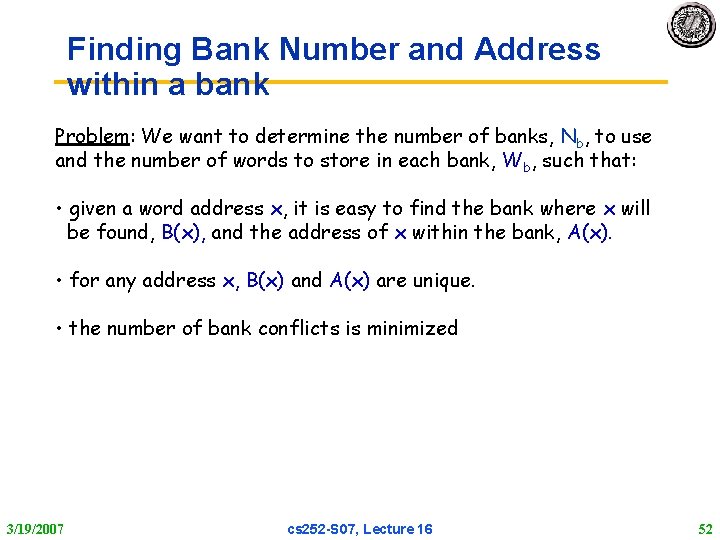

Merging Arrays Example /* Before: 2 sequential arrays */ int val[SIZE]; int key[SIZE]; /* After: 1 array of stuctures */ struct merge { int val; int key; }; struct merged_array[SIZE]; Reducing conflicts between val & key; improve spatial locality 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 18

Loop Interchange Example /* Before */ for (k = 0; k < 100; k = k+1) for (j = 0; j < 100; j = j+1) for (i = 0; i < 5000; i = i+1) x[i][j] = 2 * x[i][j]; /* After */ for (k = 0; k < 100; k = k+1) for (i = 0; i < 5000; i = i+1) for (j = 0; j < 100; j = j+1) x[i][j] = 2 * x[i][j]; Sequential accesses instead of striding through memory every 100 words; improved spatial locality 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 19

Loop Fusion Example /* Before */ for (i = 0; i < N; i = i+1) for (j = 0; j < N; j = j+1) a[i][j] = 1/b[i][j] * c[i][j]; for (i = 0; i < N; i = i+1) for (j = 0; j < N; j = j+1) d[i][j] = a[i][j] + c[i][j]; /* After */ for (i = 0; i < N; i = i+1) for (j = 0; j < N; j = j+1) { a[i][j] = 1/b[i][j] * c[i][j]; d[i][j] = a[i][j] + c[i][j]; } 2 misses per access to a & c vs. one miss per access; improve spatial locality 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 20

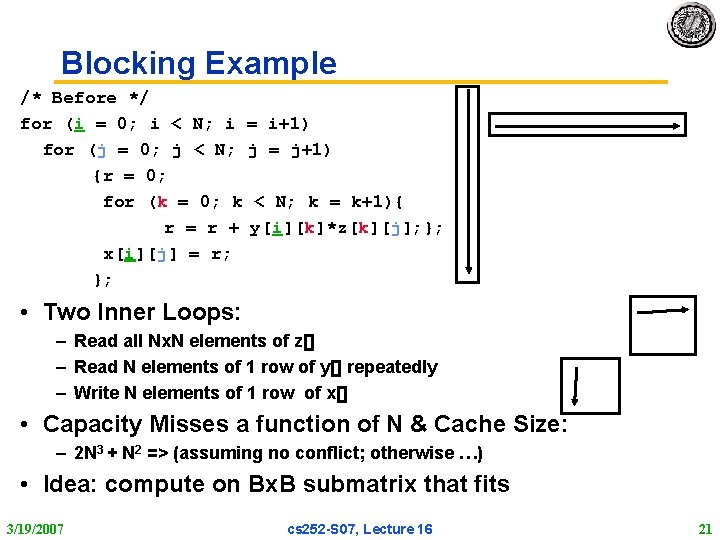

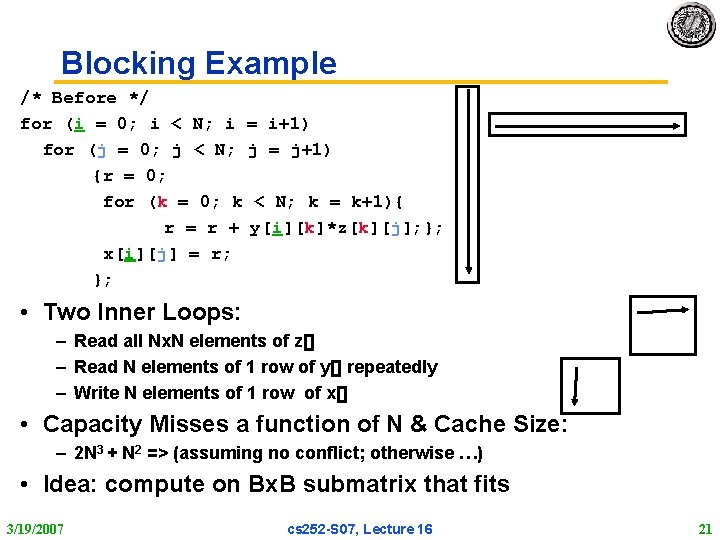

Blocking Example /* Before */ for (i = 0; i < N; i = i+1) for (j = 0; j < N; j = j+1) {r = 0; for (k = 0; k < N; k = k+1){ r = r + y[i][k]*z[k][j]; }; x[i][j] = r; }; • Two Inner Loops: – Read all Nx. N elements of z[] – Read N elements of 1 row of y[] repeatedly – Write N elements of 1 row of x[] • Capacity Misses a function of N & Cache Size: – 2 N 3 + N 2 => (assuming no conflict; otherwise …) • Idea: compute on Bx. B submatrix that fits 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 21

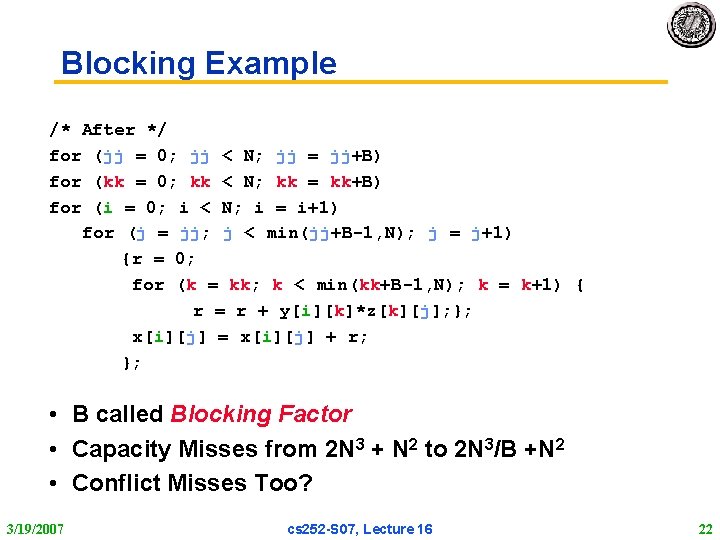

Blocking Example /* After */ for (jj = 0; jj < N; jj = jj+B) for (kk = 0; kk < N; kk = kk+B) for (i = 0; i < N; i = i+1) for (j = jj; j < min(jj+B-1, N); j = j+1) {r = 0; for (k = kk; k < min(kk+B-1, N); k = k+1) { r = r + y[i][k]*z[k][j]; }; x[i][j] = x[i][j] + r; }; • B called Blocking Factor • Capacity Misses from 2 N 3 + N 2 to 2 N 3/B +N 2 • Conflict Misses Too? 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 22

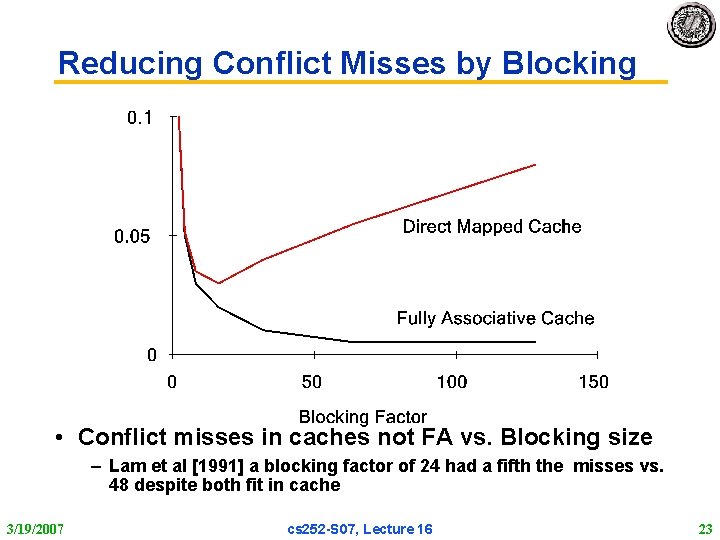

Reducing Conflict Misses by Blocking • Conflict misses in caches not FA vs. Blocking size – Lam et al [1991] a blocking factor of 24 had a fifth the misses vs. 48 despite both fit in cache 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 23

Summary of Compiler Optimizations to Reduce Cache Misses (by hand) 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 24

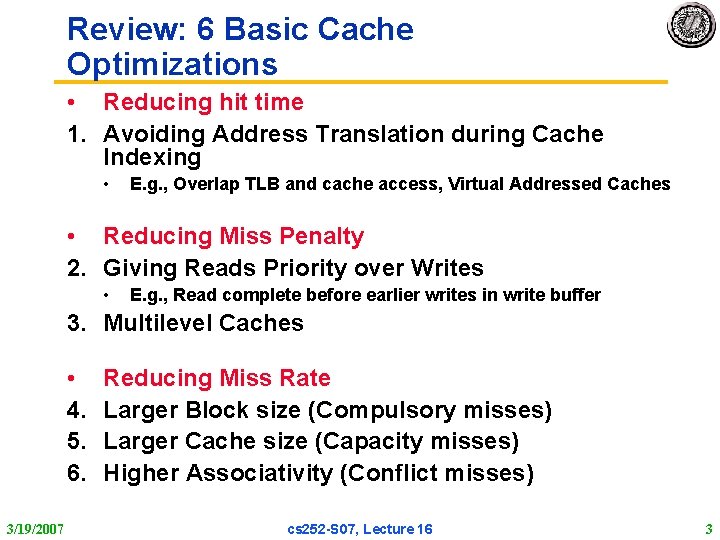

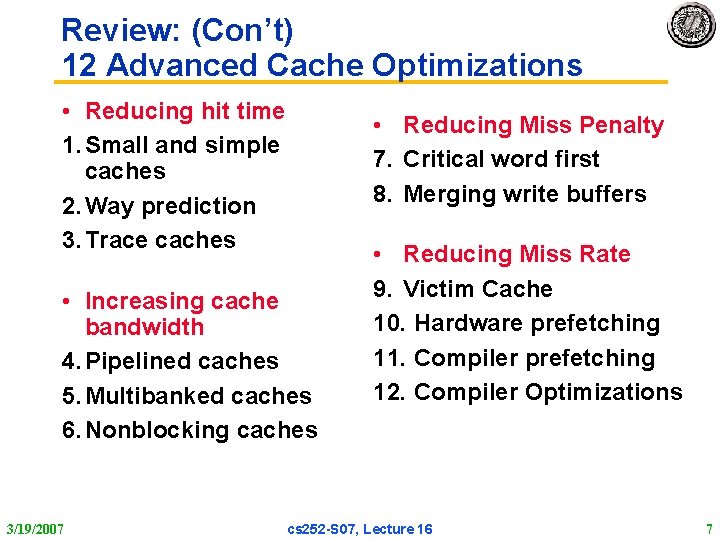

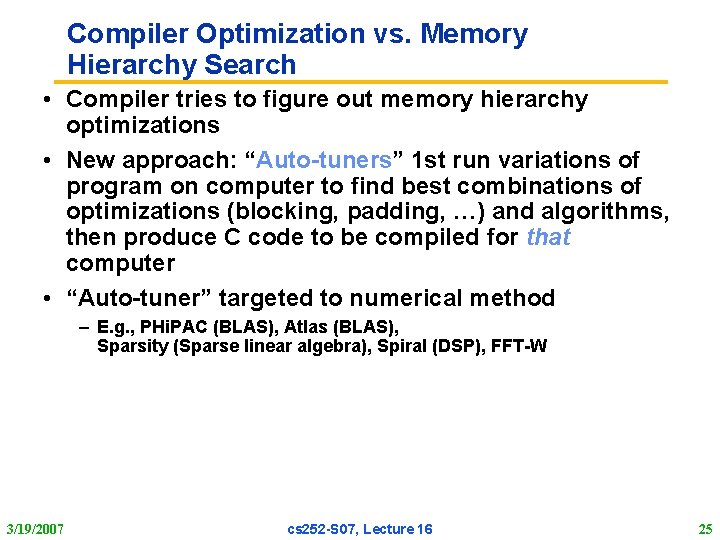

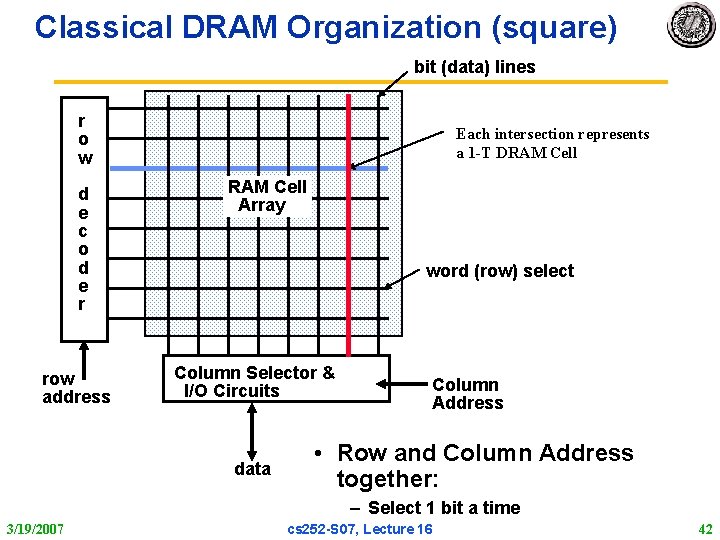

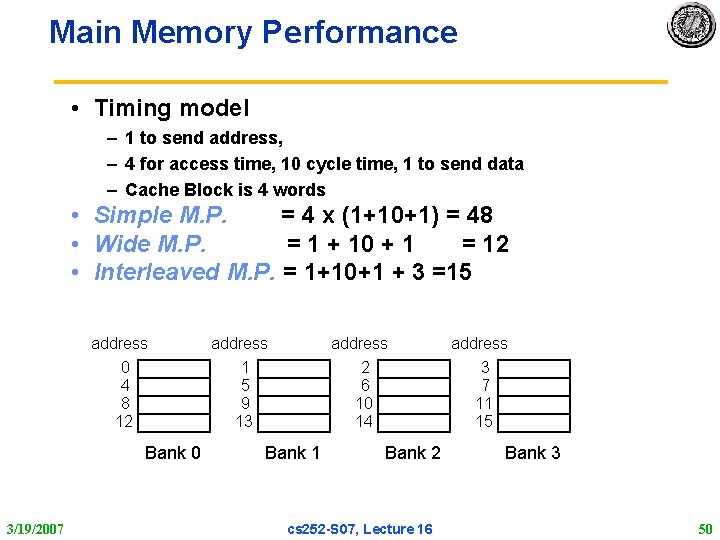

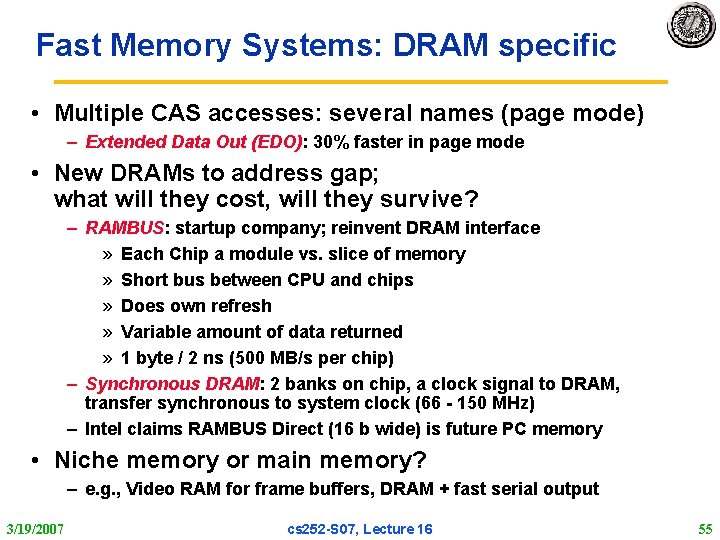

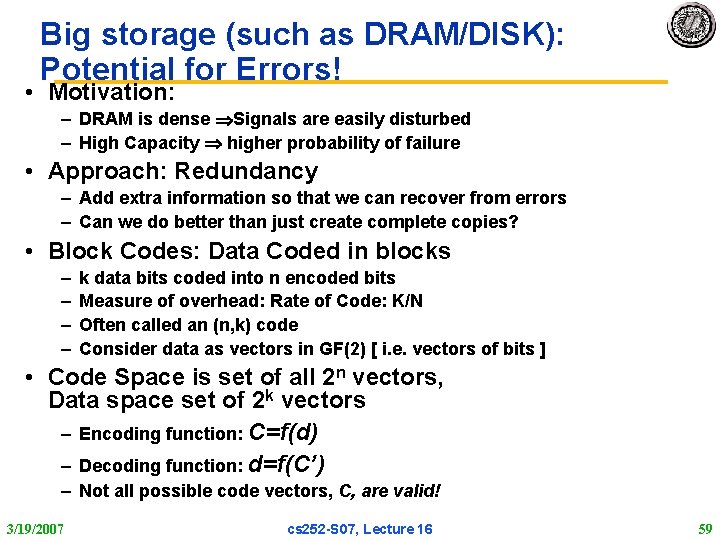

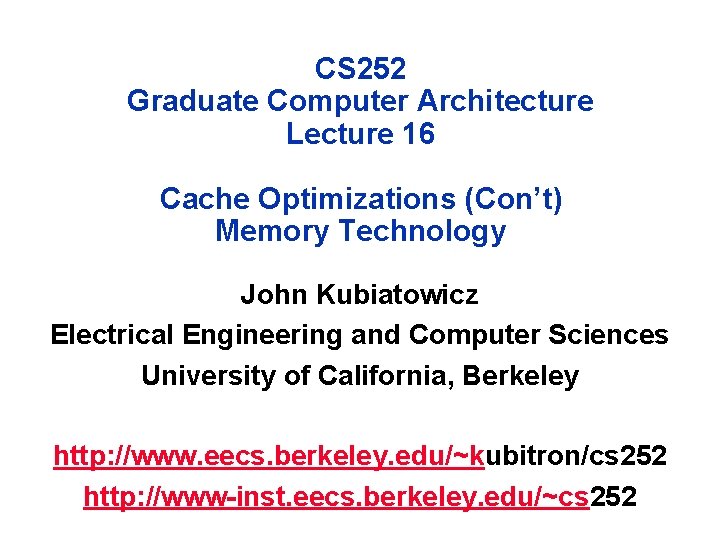

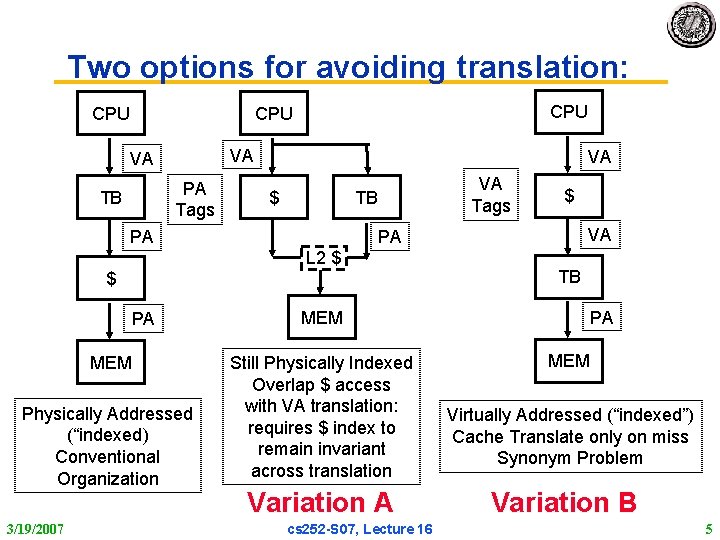

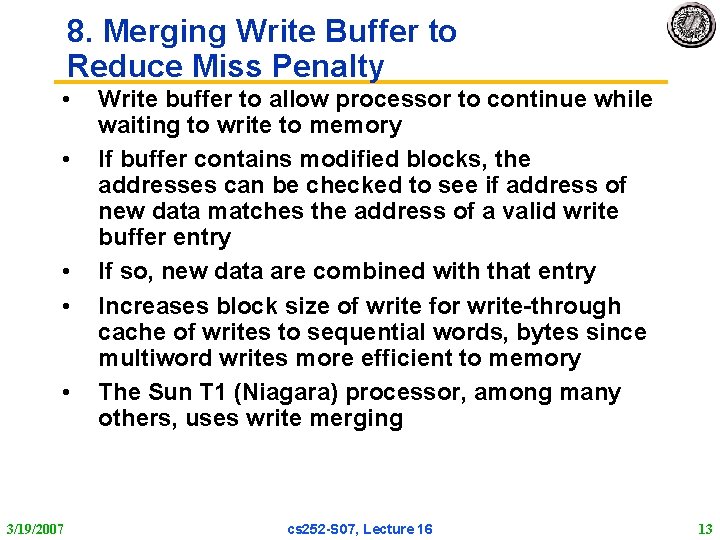

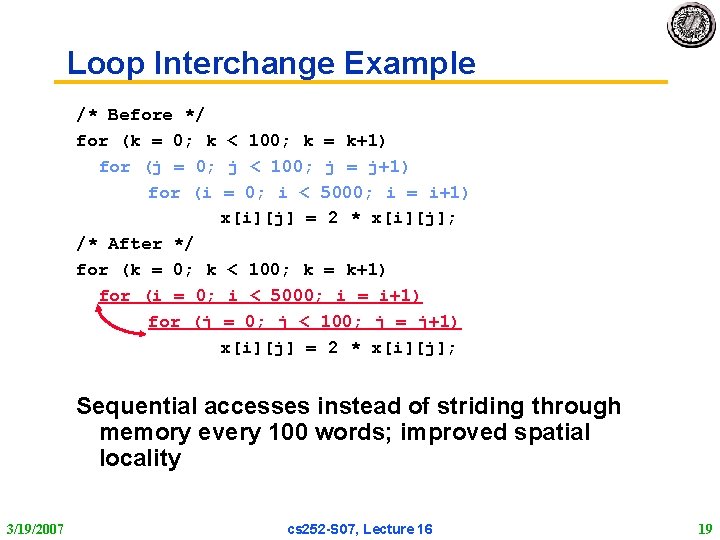

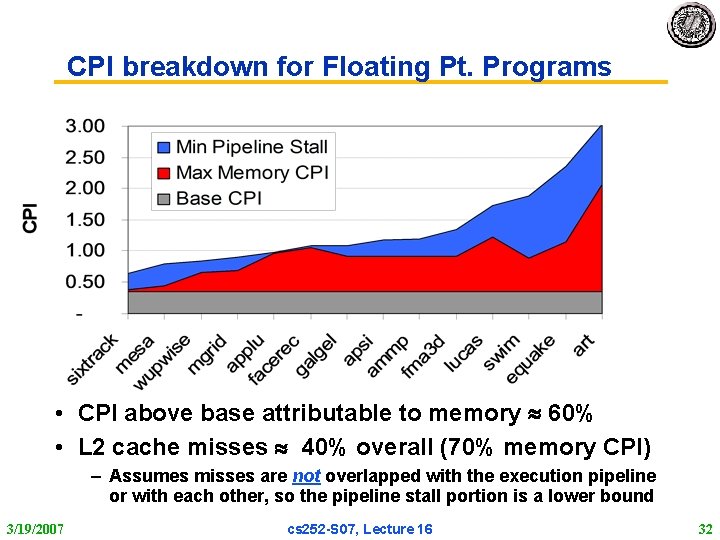

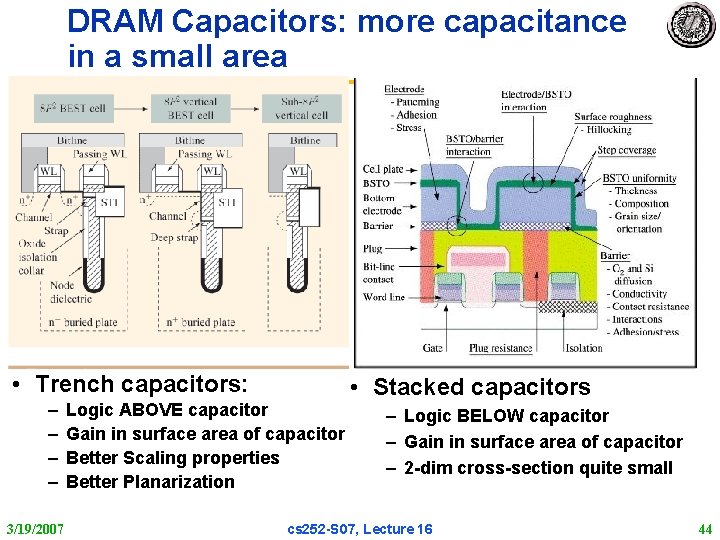

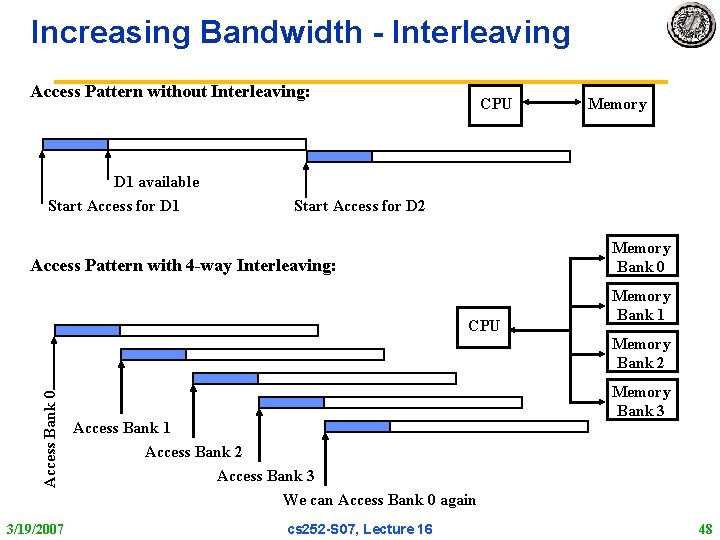

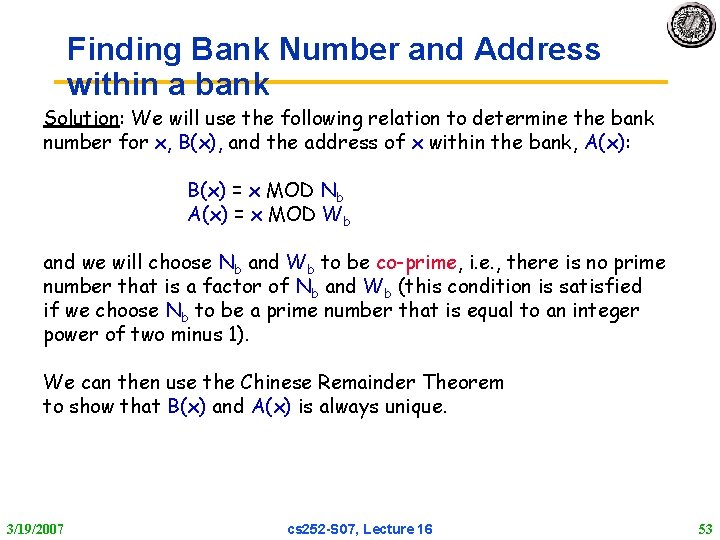

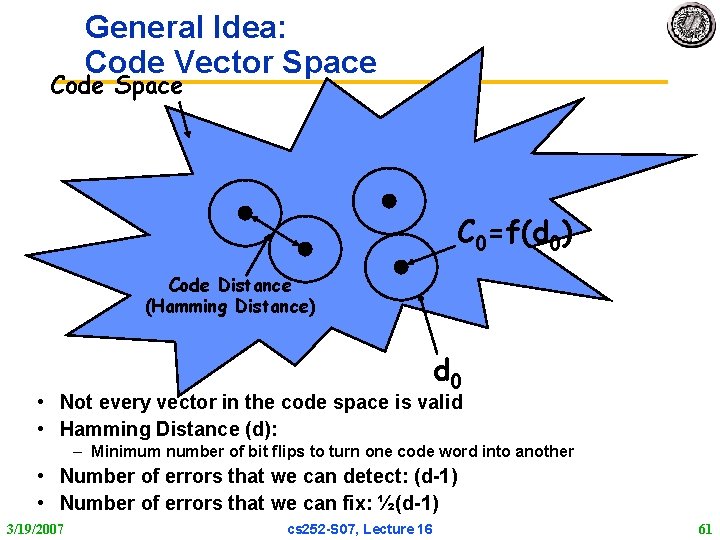

Compiler Optimization vs. Memory Hierarchy Search • Compiler tries to figure out memory hierarchy optimizations • New approach: “Auto tuners” 1 st run variations of program on computer to find best combinations of optimizations (blocking, padding, …) and algorithms, then produce C code to be compiled for that computer • “Auto tuner” targeted to numerical method – E. g. , PHi. PAC (BLAS), Atlas (BLAS), Sparsity (Sparse linear algebra), Spiral (DSP), FFT W 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 25

![Sparse Matrix Search for Blocking for finite element problem Im Yelick Vuduc 2005 Sparse Matrix – Search for Blocking for finite element problem [Im, Yelick, Vuduc, 2005]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/f911bb85d7f4f70fec054fa4283a1e6d/image-26.jpg)

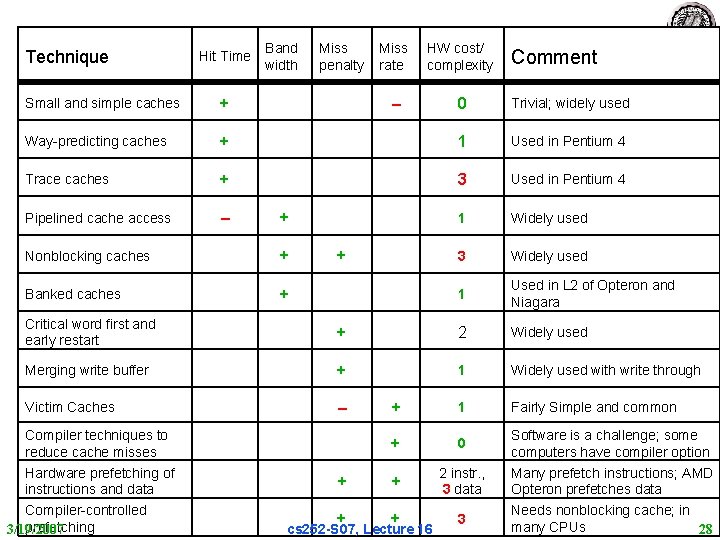

Sparse Matrix – Search for Blocking for finite element problem [Im, Yelick, Vuduc, 2005] Mflop/s Best: 4 x 2 Reference 3/19/2007 Mflop/s cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 26

Best Sparse Blocking for 8 Computers 8 row block size (r) Sun Ultra 2, Sun Ultra 3, AMD Opteron Intel Pentium M IBM Power 4, Intel/HP Itanium 2 IBM Power 3 4 2 1 1 2 4 column block size (c) 8 • All possible column block sizes selected for 8 computers; How could compiler know? 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 27

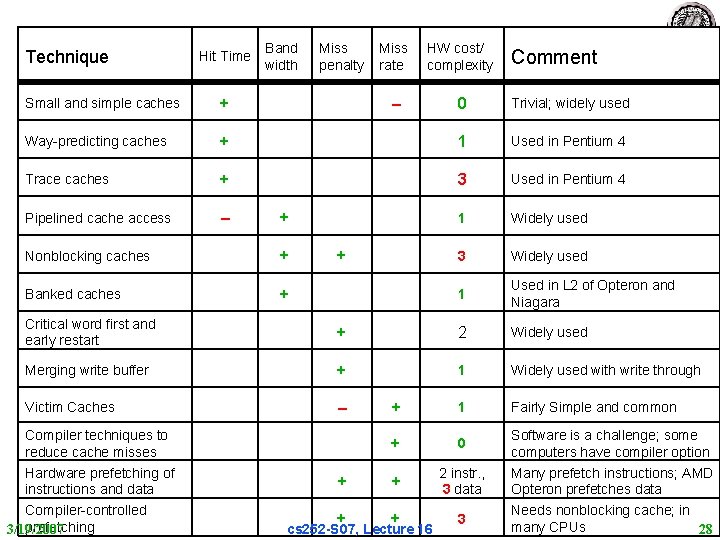

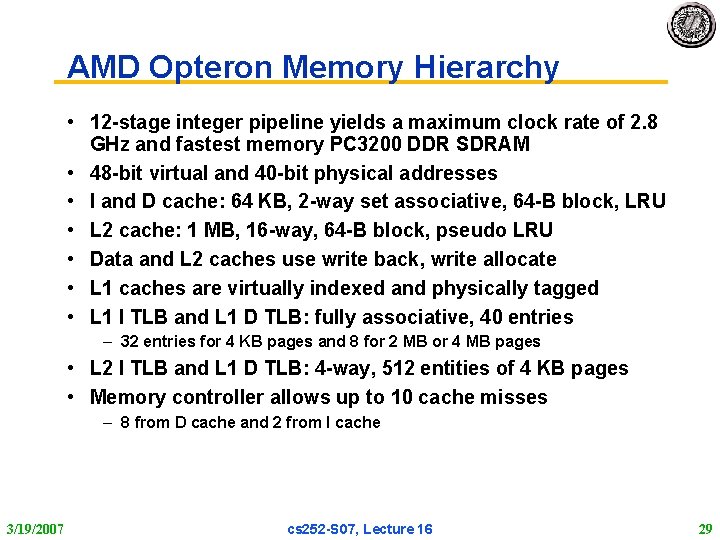

Technique Hit Time Band width Miss penalty Miss rate HW cost/ complexity – 0 Trivial; widely used Comment Small and simple caches + Way-predicting caches + 1 Used in Pentium 4 Trace caches + 3 Used in Pentium 4 Pipelined cache access – 1 Widely used 3 Widely used 1 Used in L 2 of Opteron and Niagara + Nonblocking caches + Banked caches + + Critical word first and early restart + 2 Widely used Merging write buffer + 1 Widely used with write through Victim Caches – + 1 Fairly Simple and common + 0 + + 2 instr. , 3 data + + 3 Compiler techniques to reduce cache misses Hardware prefetching of instructions and data Compiler-controlled prefetching 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 Software is a challenge; some computers have compiler option Many prefetch instructions; AMD Opteron prefetches data Needs nonblocking cache; in many CPUs 28

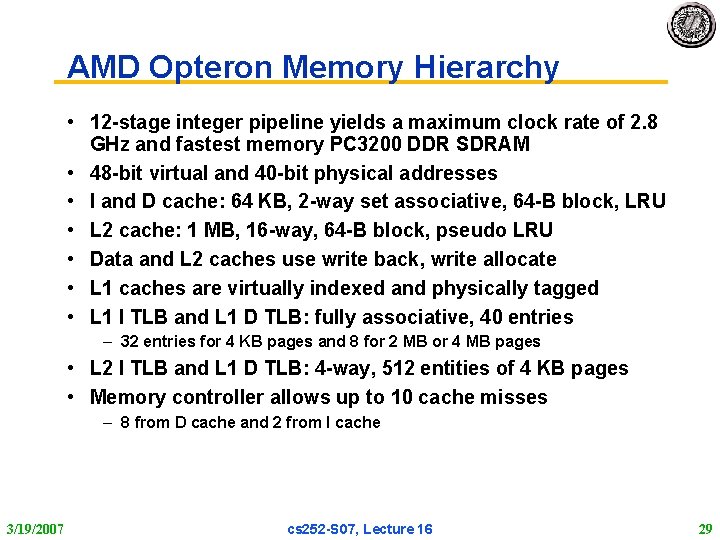

AMD Opteron Memory Hierarchy • 12 stage integer pipeline yields a maximum clock rate of 2. 8 GHz and fastest memory PC 3200 DDR SDRAM • 48 bit virtual and 40 bit physical addresses • I and D cache: 64 KB, 2 way set associative, 64 B block, LRU • L 2 cache: 1 MB, 16 way, 64 B block, pseudo LRU • Data and L 2 caches use write back, write allocate • L 1 caches are virtually indexed and physically tagged • L 1 I TLB and L 1 D TLB: fully associative, 40 entries – 32 entries for 4 KB pages and 8 for 2 MB or 4 MB pages • L 2 I TLB and L 1 D TLB: 4 way, 512 entities of 4 KB pages • Memory controller allows up to 10 cache misses – 8 from D cache and 2 from I cache 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 29

Opteron Memory Hierarchy Performance • For SPEC 2000 – I cache misses per instruction is 0. 01% to 0. 09% – D cache misses per instruction are 1. 34% to 1. 43% – L 2 cache misses per instruction are 0. 23% to 0. 36% • Commercial benchmark (“TPC C like”) – I cache misses per instruction is 1. 83% (100 X!) – D cache misses per instruction are 1. 39% ( same) – L 2 cache misses per instruction are 0. 62% (2 X to 3 X) • How compare to ideal CPI of 0. 33? 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 30

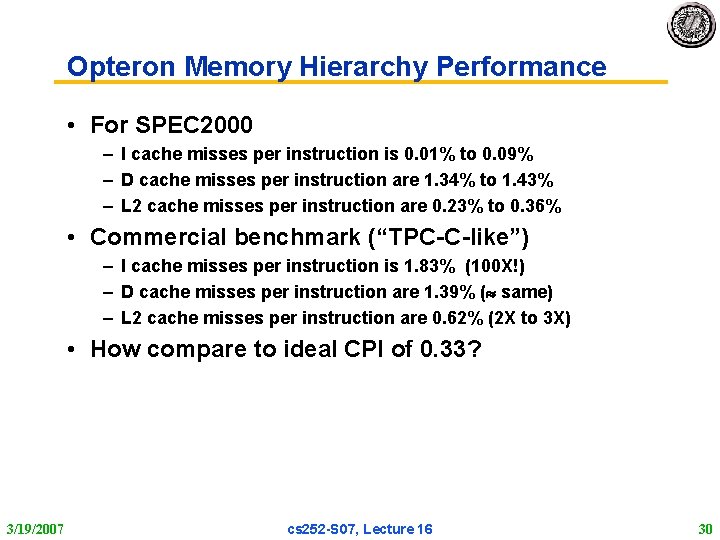

CPI breakdown for Integer Programs • CPI above base attributable to memory 50% • L 2 cache misses 25% overall (50% memory CPI) – Assumes misses are not overlapped with the execution pipeline or with each other, so the pipeline stall portion is a lower bound 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 31

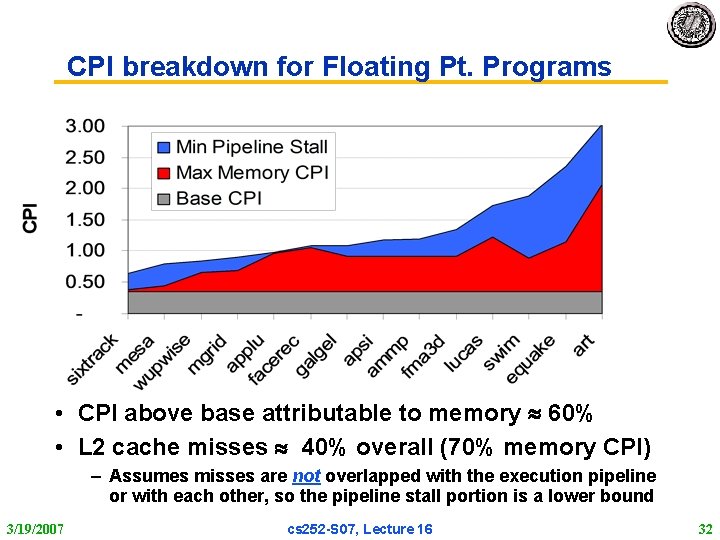

CPI breakdown for Floating Pt. Programs • CPI above base attributable to memory 60% • L 2 cache misses 40% overall (70% memory CPI) – Assumes misses are not overlapped with the execution pipeline or with each other, so the pipeline stall portion is a lower bound 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 32

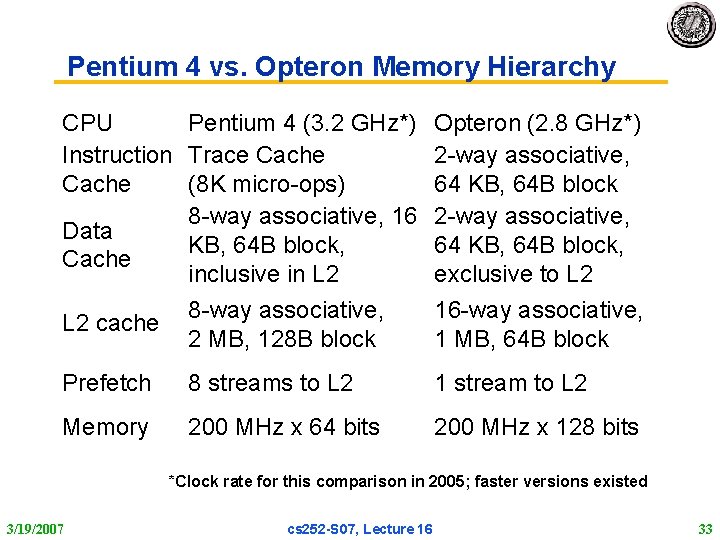

Pentium 4 vs. Opteron Memory Hierarchy CPU Pentium 4 (3. 2 GHz*) Instruction Trace Cache (8 K micro-ops) 8 -way associative, 16 Data KB, 64 B block, Cache inclusive in L 2 Opteron (2. 8 GHz*) 2 -way associative, 64 KB, 64 B block, exclusive to L 2 cache 8 -way associative, 2 MB, 128 B block 16 -way associative, 1 MB, 64 B block Prefetch 8 streams to L 2 1 stream to L 2 Memory 200 MHz x 64 bits 200 MHz x 128 bits *Clock rate for this comparison in 2005; faster versions existed 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 33

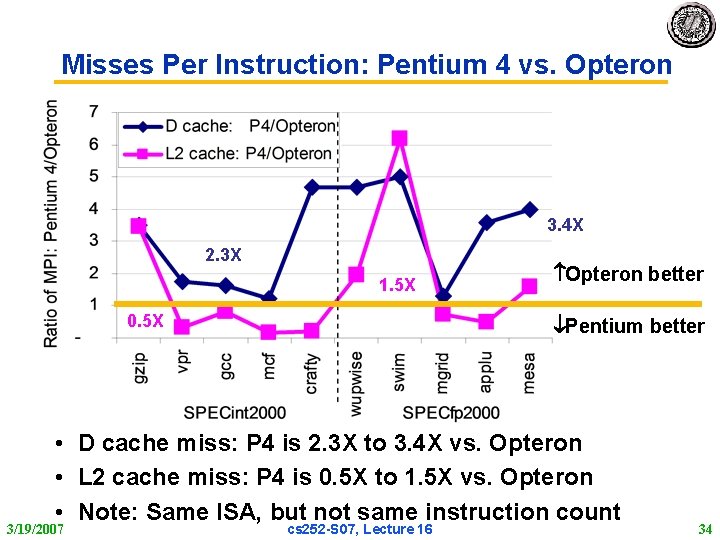

Misses Per Instruction: Pentium 4 vs. Opteron 3. 4 X 2. 3 X 1. 5 X 0. 5 X Opteron better Pentium better • D cache miss: P 4 is 2. 3 X to 3. 4 X vs. Opteron • L 2 cache miss: P 4 is 0. 5 X to 1. 5 X vs. Opteron • Note: Same ISA, but not same instruction count 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 34

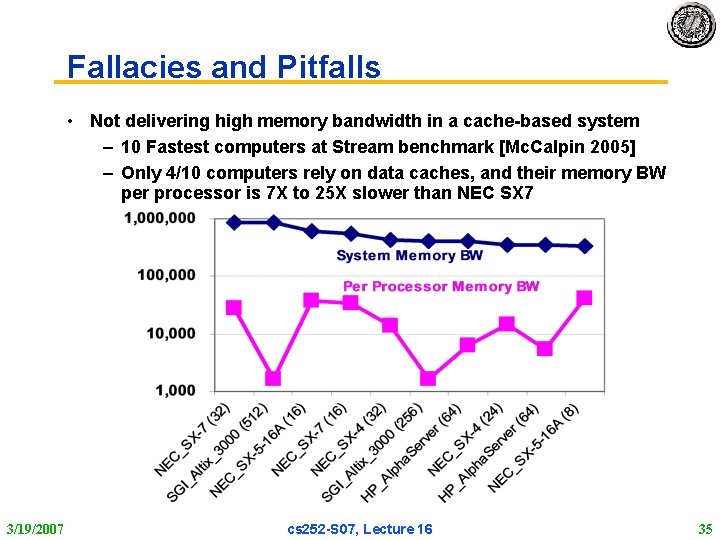

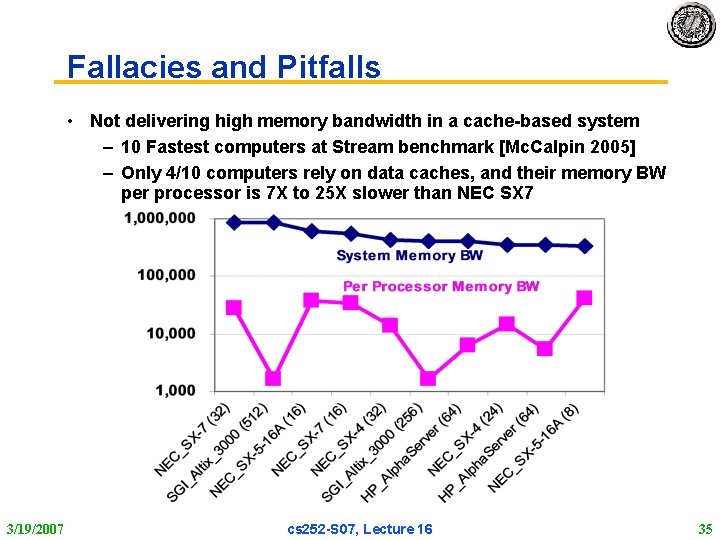

Fallacies and Pitfalls • Not delivering high memory bandwidth in a cache based system – 10 Fastest computers at Stream benchmark [Mc. Calpin 2005] – Only 4/10 computers rely on data caches, and their memory BW per processor is 7 X to 25 X slower than NEC SX 7 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 35

Main Memory Background • Performance of Main Memory: – Latency: Cache Miss Penalty » Access Time: time between request and word arrives » Cycle Time: time between requests – Bandwidth: I/O & Large Block Miss Penalty (L 2) • Main Memory is DRAM: Dynamic Random Access Memory – Dynamic since needs to be refreshed periodically (8 ms, 1% time) – Addresses divided into 2 halves (Memory as a 2 D matrix): » RAS or Row Address Strobe » CAS or Column Address Strobe • Cache uses SRAM: Static Random Access Memory – No refresh (6 transistors/bit vs. 1 transistor Size: DRAM/SRAM 4 -8, Cost/Cycle time: SRAM/DRAM 8 -16 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 36

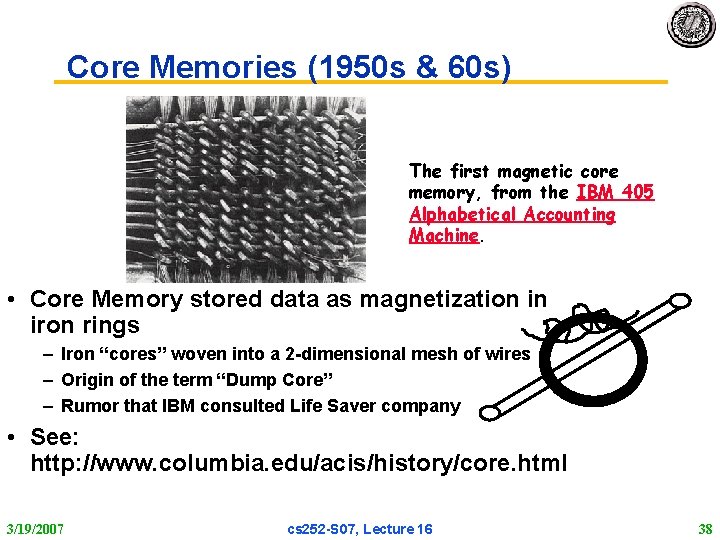

Main Memory Deep Background • • • “Out of Core”, “In Core, ” “Core Dump”? “Core memory”? Non volatile, magnetic Lost to 4 Kbit DRAM (today using 512 Mbit DRAM) Access time 750 ns, cycle time 1500 3000 ns 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 37

Core Memories (1950 s & 60 s) The first magnetic core memory, from the IBM 405 Alphabetical Accounting Machine. • Core Memory stored data as magnetization in iron rings – Iron “cores” woven into a 2 dimensional mesh of wires – Origin of the term “Dump Core” – Rumor that IBM consulted Life Saver company • See: http: //www. columbia. edu/acis/history/core. html 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 38

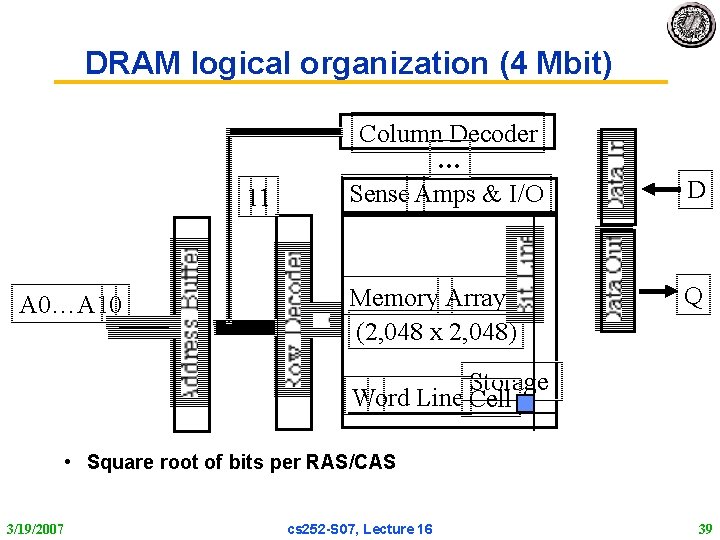

DRAM logical organization (4 Mbit) 11 A 0…A 10 Column Decoder … Sense Amps & I/O Memory Array (2, 048 x 2, 048) D Q Storage Word Line Cell • Square root of bits per RAS/CAS 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 39

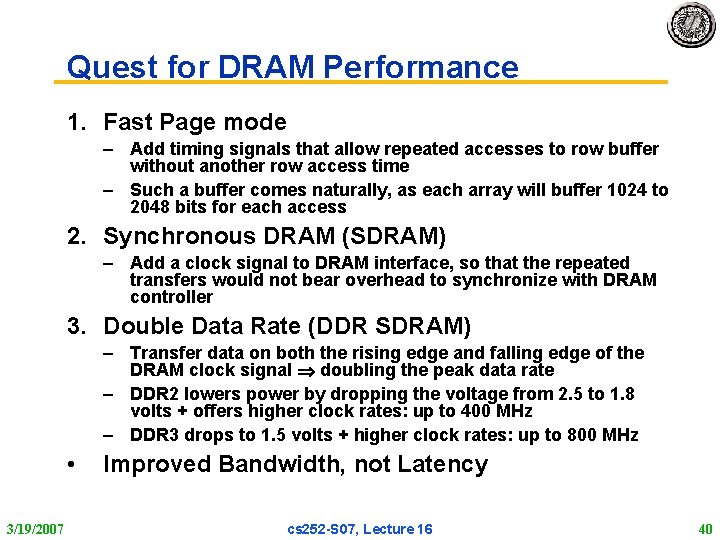

Quest for DRAM Performance 1. Fast Page mode – Add timing signals that allow repeated accesses to row buffer without another row access time – Such a buffer comes naturally, as each array will buffer 1024 to 2048 bits for each access 2. Synchronous DRAM (SDRAM) – Add a clock signal to DRAM interface, so that the repeated transfers would not bear overhead to synchronize with DRAM controller 3. Double Data Rate (DDR SDRAM) – Transfer data on both the rising edge and falling edge of the DRAM clock signal doubling the peak data rate – DDR 2 lowers power by dropping the voltage from 2. 5 to 1. 8 volts + offers higher clock rates: up to 400 MHz – DDR 3 drops to 1. 5 volts + higher clock rates: up to 800 MHz • 3/19/2007 Improved Bandwidth, not Latency cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 40

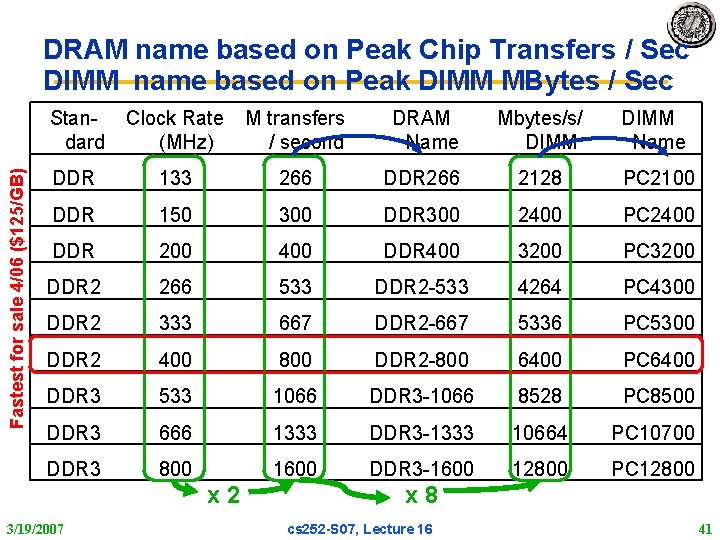

Fastest for sale 4/06 ($125/GB) DRAM name based on Peak Chip Transfers / Sec DIMM name based on Peak DIMM MBytes / Sec Standard Clock Rate (MHz) M transfers / second DRAM Name Mbytes/s/ DIMM Name DDR 133 266 DDR 266 2128 PC 2100 DDR 150 300 DDR 300 2400 PC 2400 DDR 200 400 DDR 400 3200 PC 3200 DDR 2 266 533 DDR 2 -533 4264 PC 4300 DDR 2 333 667 DDR 2 -667 5336 PC 5300 DDR 2 400 800 DDR 2 -800 6400 PC 6400 DDR 3 533 1066 DDR 3 -1066 8528 PC 8500 DDR 3 666 1333 DDR 3 -1333 10664 PC 10700 DDR 3 800 1600 DDR 3 -1600 12800 PC 12800 x 2 3/19/2007 x 8 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 41

Classical DRAM Organization (square) bit (data) lines r o w d e c o d e r row address Each intersection represents a 1 -T DRAM Cell Array word (row) select Column Selector & I/O Circuits data Column Address • Row and Column Address together: – Select 1 bit a time 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 42

Review: 1 T Memory Cell (DRAM) row select • Write: – 1. Drive bit line – 2. . Select row • Read: – 1. Precharge bit line to Vdd/2 – 2. . Select row bit – 3. Cell and bit line share charges » Very small voltage changes on the bit line – 4. Sense (fancy sense amp) » Can detect changes of ~1 million electrons – 5. Write: restore the value • Refresh – 1. Just do a dummy read to every cell. 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 43

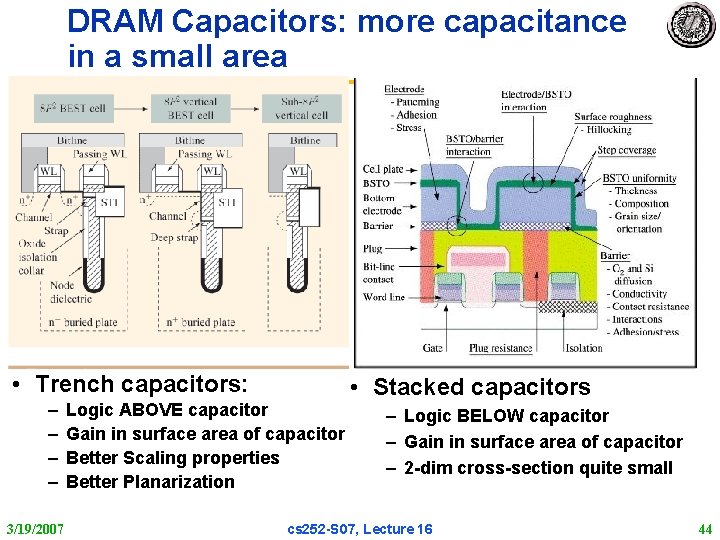

DRAM Capacitors: more capacitance in a small area • Trench capacitors: – – 3/19/2007 Logic ABOVE capacitor Gain in surface area of capacitor Better Scaling properties Better Planarization • Stacked capacitors – Logic BELOW capacitor – Gain in surface area of capacitor – 2 dim cross section quite small cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 44

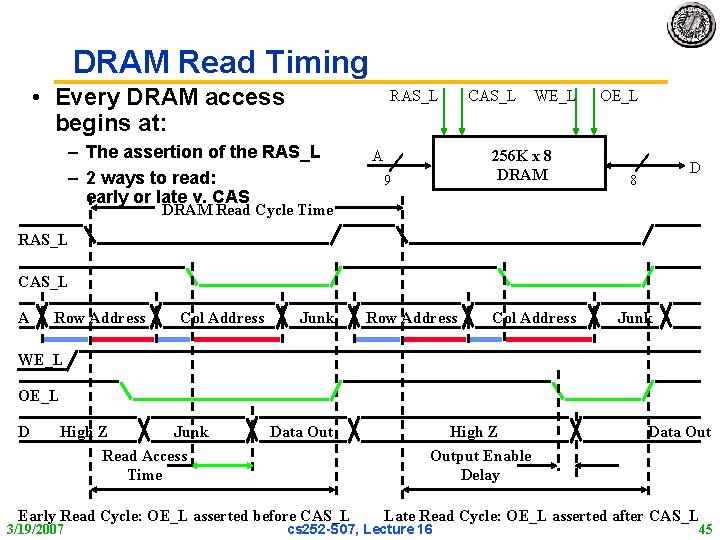

DRAM Read Timing • Every DRAM access begins at: RAS_L – The assertion of the RAS_L – 2 ways to read: early or late v. CAS A CAS_L WE_L 256 K x 8 DRAM 9 OE_L D 8 DRAM Read Cycle Time RAS_L CAS_L A Row Address Col Address Junk WE_L OE_L D High Z Junk Read Access Time Data Out Early Read Cycle: OE_L asserted before CAS_L 3/19/2007 High Z Output Enable Delay Data Out Late Read Cycle: OE_L asserted after CAS_L cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 45

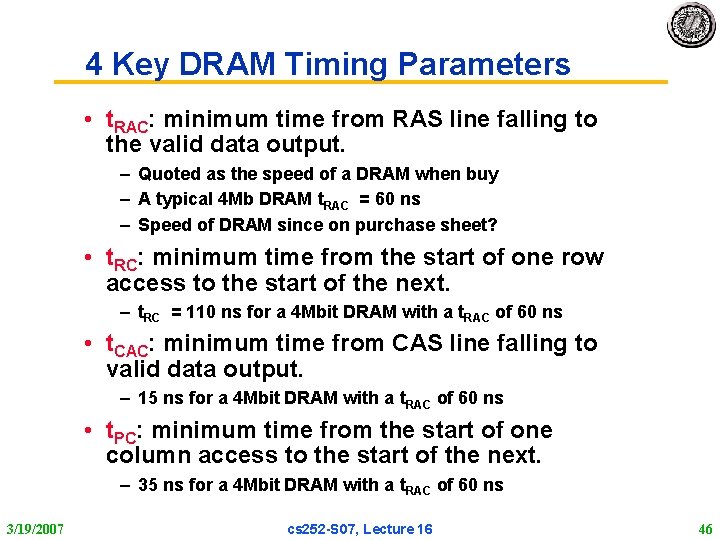

4 Key DRAM Timing Parameters • t. RAC: minimum time from RAS line falling to the valid data output. – Quoted as the speed of a DRAM when buy – A typical 4 Mb DRAM t. RAC = 60 ns – Speed of DRAM since on purchase sheet? • t. RC: minimum time from the start of one row access to the start of the next. – t. RC = 110 ns for a 4 Mbit DRAM with a t. RAC of 60 ns • t. CAC: minimum time from CAS line falling to valid data output. – 15 ns for a 4 Mbit DRAM with a t. RAC of 60 ns • t. PC: minimum time from the start of one column access to the start of the next. – 35 ns for a 4 Mbit DRAM with a t. RAC of 60 ns 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 46

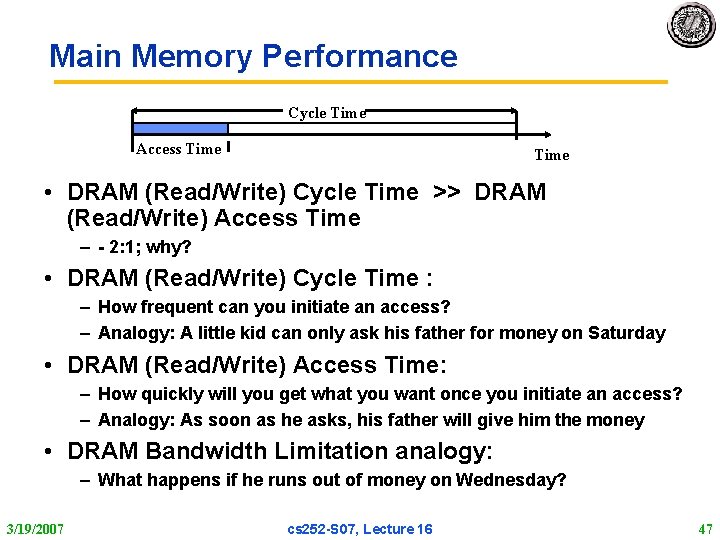

Main Memory Performance Cycle Time Access Time • DRAM (Read/Write) Cycle Time >> DRAM (Read/Write) Access Time – 2: 1; why? • DRAM (Read/Write) Cycle Time : – How frequent can you initiate an access? – Analogy: A little kid can only ask his father for money on Saturday • DRAM (Read/Write) Access Time: – How quickly will you get what you want once you initiate an access? – Analogy: As soon as he asks, his father will give him the money • DRAM Bandwidth Limitation analogy: – What happens if he runs out of money on Wednesday? 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 47

Increasing Bandwidth Interleaving Access Pattern without Interleaving: D 1 available Start Access for D 1 CPU Memory Start Access for D 2 Memory Bank 0 Access Pattern with 4 -way Interleaving: CPU Memory Bank 1 Access Bank 0 Memory Bank 2 3/19/2007 Access Bank 1 Access Bank 2 Access Bank 3 We can Access Bank 0 again cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 Memory Bank 3 48

Main Memory Performance • Wide: • Simple: • Interleaved: – CPU/Mux 1 word; Mux/Cache, Bus, Memory N words (Alpha: 64 bits & 256 bits) – CPU, Cache, Bus 1 word: Memory N Modules (4 Modules); example is word interleaved – CPU, Cache, Bus, Memory same width (32 bits) 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 49

Main Memory Performance • Timing model – 1 to send address, – 4 for access time, 10 cycle time, 1 to send data – Cache Block is 4 words • Simple M. P. = 4 x (1+10+1) = 48 • Wide M. P. = 1 + 10 + 1 = 12 • Interleaved M. P. = 1+10+1 + 3 =15 address 0 4 8 12 Bank 0 3/19/2007 address 1 5 9 13 Bank 1 address 2 6 10 14 3 7 11 15 Bank 2 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 Bank 3 50

![Avoiding Bank Conflicts Lots of banks int x256512 for j 0 j Avoiding Bank Conflicts • Lots of banks int x[256][512]; for (j = 0; j](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/f911bb85d7f4f70fec054fa4283a1e6d/image-51.jpg)

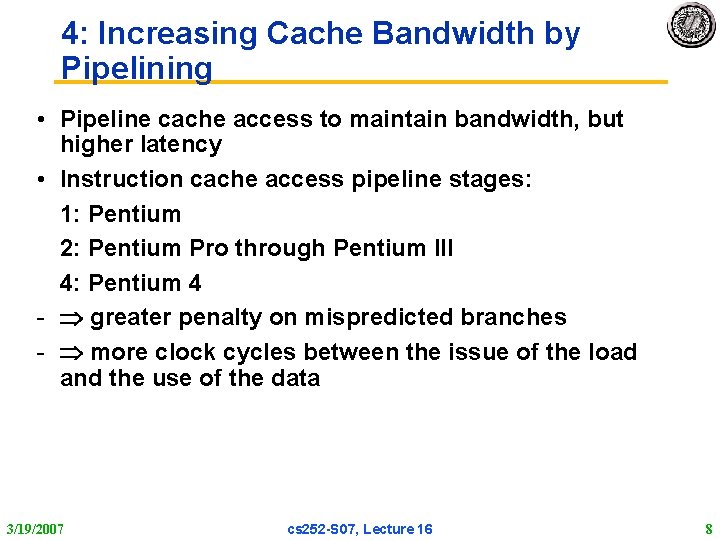

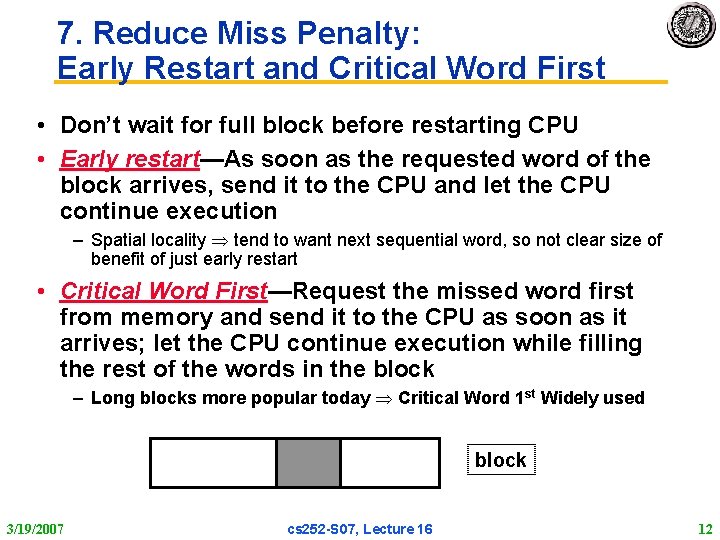

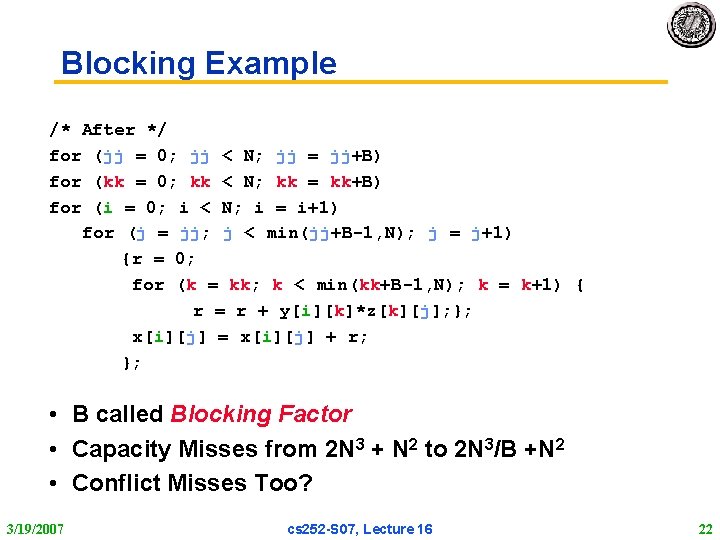

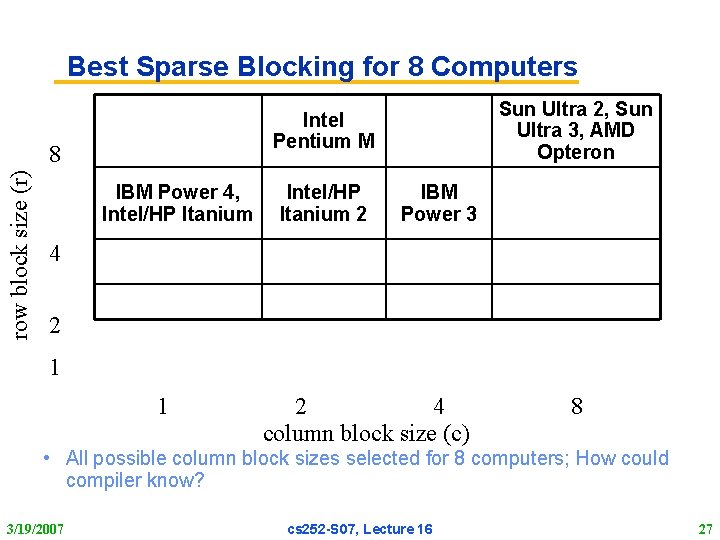

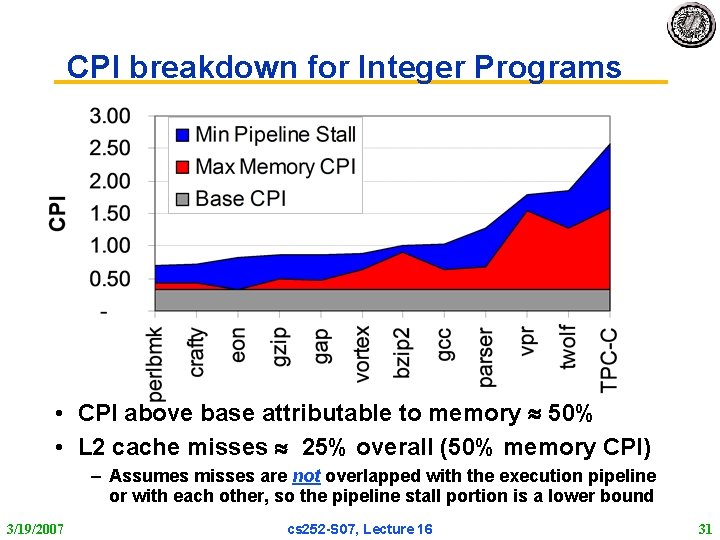

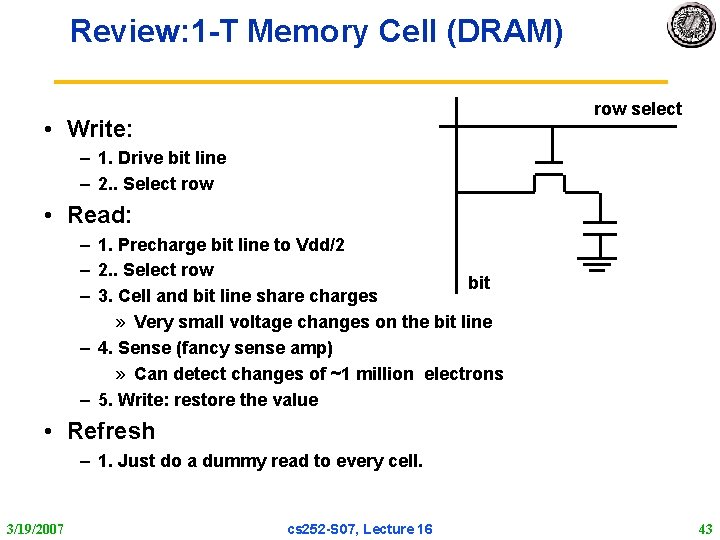

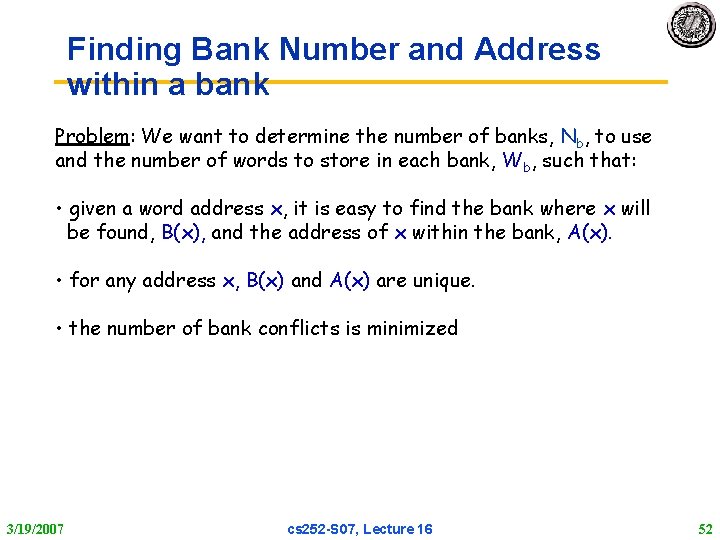

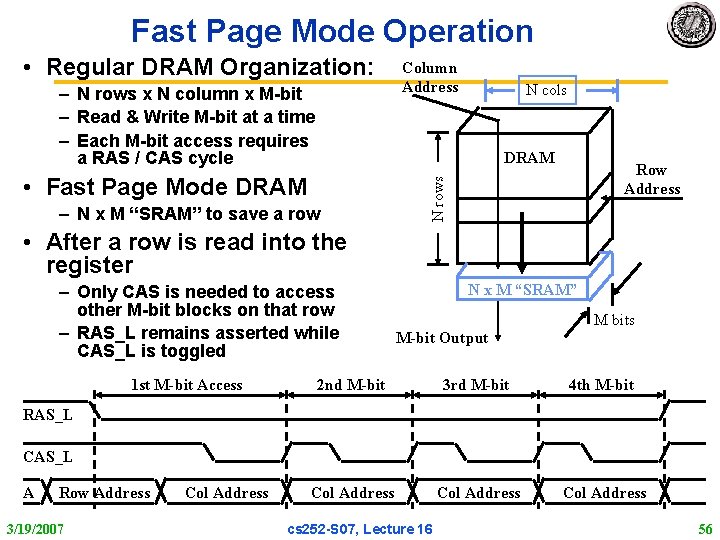

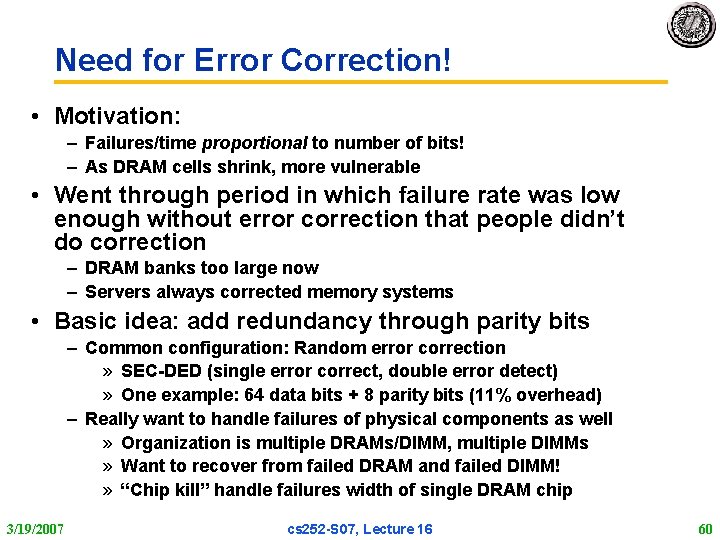

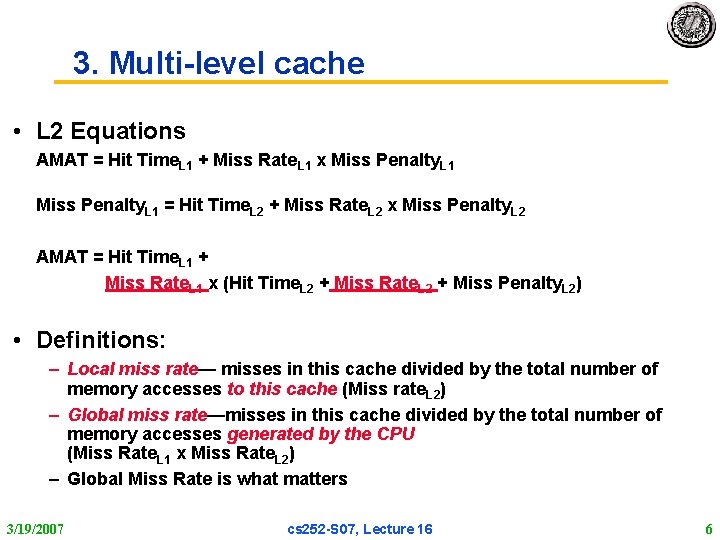

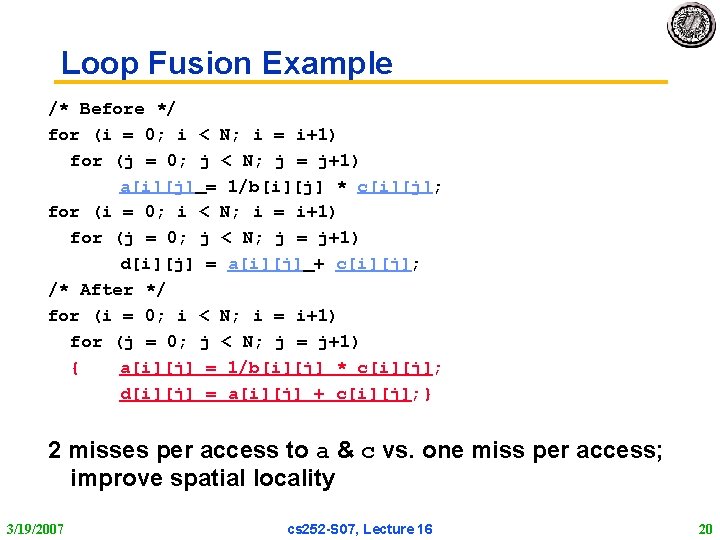

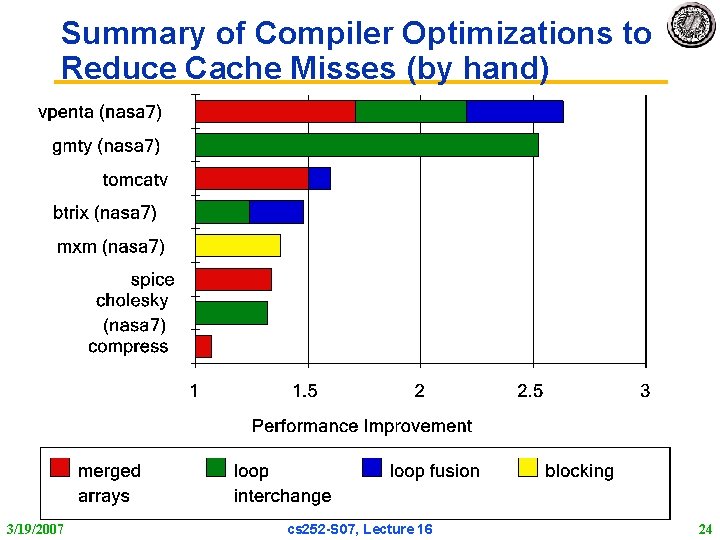

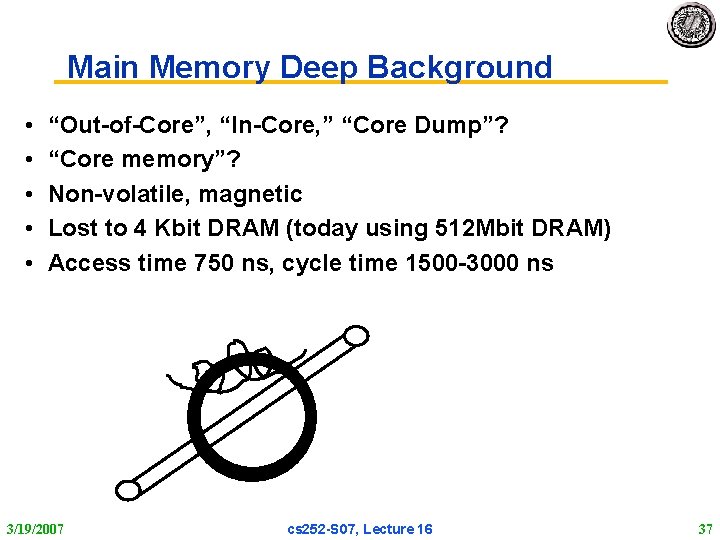

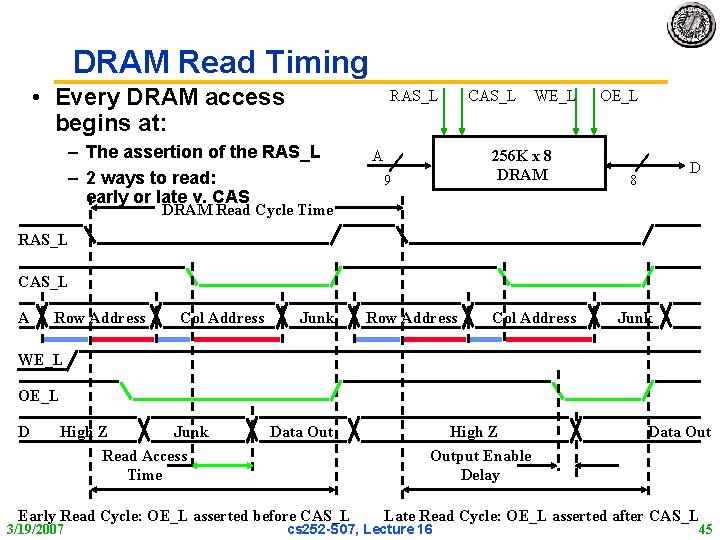

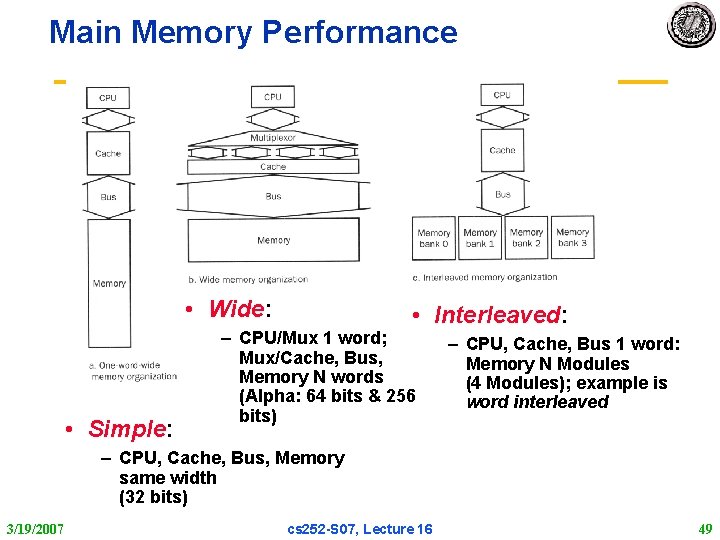

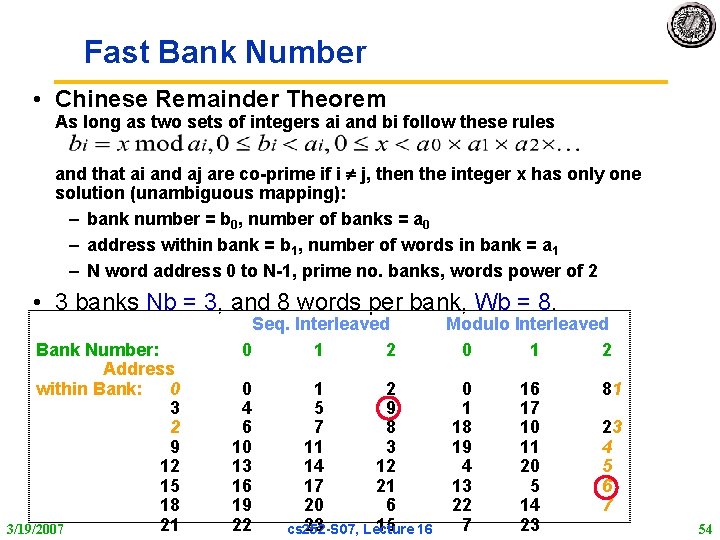

Avoiding Bank Conflicts • Lots of banks int x[256][512]; for (j = 0; j < 512; j = j+1) for (i = 0; i < 256; i = i+1) x[i][j] = 2 * x[i][j]; • Even with 128 banks, since 512 is multiple of 128, conflict on word accesses • SW: loop interchange or declaring array not power of 2 (“array padding”) • HW: Prime number of banks – – 3/19/2007 bank number = address mod number of banks address within bank = address / number of words in bank modulo & divide per memory access with prime no. banks? cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 51

Finding Bank Number and Address within a bank Problem: We want to determine the number of banks, Nb, to use and the number of words to store in each bank, Wb, such that: • given a word address x, it is easy to find the bank where x will be found, B(x), and the address of x within the bank, A(x). • for any address x, B(x) and A(x) are unique. • the number of bank conflicts is minimized 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 52

Finding Bank Number and Address within a bank Solution: We will use the following relation to determine the bank number for x, B(x), and the address of x within the bank, A(x): B(x) = x MOD Nb A(x) = x MOD Wb and we will choose Nb and Wb to be co-prime, i. e. , there is no prime number that is a factor of Nb and Wb (this condition is satisfied if we choose Nb to be a prime number that is equal to an integer power of two minus 1). We can then use the Chinese Remainder Theorem to show that B(x) and A(x) is always unique. 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 53

Fast Bank Number • Chinese Remainder Theorem As long as two sets of integers ai and bi follow these rules and that ai and aj are co prime if i j, then the integer x has only one solution (unambiguous mapping): – bank number = b 0, number of banks = a 0 – address within bank = b 1, number of words in bank = a 1 – N word address 0 to N 1, prime no. banks, words power of 2 • 3 banks Nb = 3, and 8 words per bank, Wb = 8. Bank Number: Address within Bank: 0 3 2 9 12 15 18 21 3/19/2007 Seq. Interleaved 0 1 2 0 4 6 10 13 16 19 22 1 2 5 9 7 8 11 3 14 12 17 21 20 6 23 15 16 cs 252 S 07, Lecture Modulo Interleaved 0 1 2 0 1 18 19 4 13 22 7 16 17 10 11 20 5 14 23 81 23 4 5 6 7 54

Fast Memory Systems: DRAM specific • Multiple CAS accesses: several names (page mode) – Extended Data Out (EDO): 30% faster in page mode • New DRAMs to address gap; what will they cost, will they survive? – RAMBUS: startup company; reinvent DRAM interface » Each Chip a module vs. slice of memory » Short bus between CPU and chips » Does own refresh » Variable amount of data returned » 1 byte / 2 ns (500 MB/s per chip) – Synchronous DRAM: 2 banks on chip, a clock signal to DRAM, transfer synchronous to system clock (66 150 MHz) – Intel claims RAMBUS Direct (16 b wide) is future PC memory • Niche memory or main memory? – e. g. , Video RAM for frame buffers, DRAM + fast serial output 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 55

Fast Page Mode Operation • Regular DRAM Organization: – N rows x N column x M bit – Read & Write M bit at a time – Each M bit access requires a RAS / CAS cycle Column Address N cols DRAM – N x M “SRAM” to save a row N rows • Fast Page Mode DRAM Row Address • After a row is read into the register – Only CAS is needed to access other M bit blocks on that row – RAS_L remains asserted while CAS_L is toggled 1 st M-bit Access N x M “SRAM” M bits M-bit Output 2 nd M-bit 3 rd M-bit 4 th M-bit Col Address RAS_L CAS_L A Row Address 3/19/2007 Col Address cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 56

Something new: Structure of Tunneling Magnetic Junction • Tunneling Magnetic Junction RAM (TMJ RAM) – Speed of SRAM, density of DRAM, non volatile (no refresh) – “Spintronics”: combination quantum spin and electronics – Same technology used in high density disk drives 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 57

MEMS based Storage • Magnetic “sled” floats on array of read/write heads – Approx 250 Gbit/in 2 – Data rates: IBM: 250 MB/s w 1000 heads CMU: 3. 1 MB/s w 400 heads • Electrostatic actuators move media around to align it with heads – Sweep sled ± 50 m in < 0. 5 s • Capacity estimated to be in the 1 10 GB in 10 cm 2 See Ganger et all: http: //www. lcs. ece. cmu. edu/research/MEMS 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 58

Big storage (such as DRAM/DISK): Potential for Errors! • Motivation: – DRAM is dense Signals are easily disturbed – High Capacity higher probability of failure • Approach: Redundancy – Add extra information so that we can recover from errors – Can we do better than just create complete copies? • Block Codes: Data Coded in blocks – – k data bits coded into n encoded bits Measure of overhead: Rate of Code: K/N Often called an (n, k) code Consider data as vectors in GF(2) [ i. e. vectors of bits ] • Code Space is set of all 2 n vectors, Data space set of 2 k vectors – Encoding function: C=f(d) – Decoding function: d=f(C’) – Not all possible code vectors, C, are valid! 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 59

Need for Error Correction! • Motivation: – Failures/time proportional to number of bits! – As DRAM cells shrink, more vulnerable • Went through period in which failure rate was low enough without error correction that people didn’t do correction – DRAM banks too large now – Servers always corrected memory systems • Basic idea: add redundancy through parity bits – Common configuration: Random error correction » SEC DED (single error correct, double error detect) » One example: 64 data bits + 8 parity bits (11% overhead) – Really want to handle failures of physical components as well » Organization is multiple DRAMs/DIMM, multiple DIMMs » Want to recover from failed DRAM and failed DIMM! » “Chip kill” handle failures width of single DRAM chip 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 60

General Idea: Code Vector Space Code Space C 0=f(d 0) Code Distance (Hamming Distance) d 0 • Not every vector in the code space is valid • Hamming Distance (d): – Minimum number of bit flips to turn one code word into another • Number of errors that we can detect: (d 1) • Number of errors that we can fix: ½(d 1) 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 61

Conclusion • Memory wall inspires optimizations since so much performance lost there – Reducing hit time: Small and simple caches, Way prediction, Trace caches – Increasing cache bandwidth: Pipelined caches, Multibanked caches, Nonblocking caches – Reducing Miss Penalty: Critical word first, Merging write buffers – Reducing Miss Rate: Compiler optimizations – Reducing miss penalty or miss rate via parallelism: Hardware prefetching, Compiler prefetching • “Auto tuners” search replacing static compilation to explore optimization space? 3/19/2007 cs 252 S 07, Lecture 16 62