CS 2403 Programming Languages Evolution of Programming Languages

- Slides: 27

CS 2403 Programming Languages Evolution of Programming Languages Chung-Ta King Department of Computer Science National Tsing Hua University (Slides are adopted from Concepts of Programming Languages, R. W. Sebesta; Modern Programming Languages: A Practical Introduction, A. B. Webber)

Consider a Special C Language t No dynamic variables l All variables are global and static; no malloc(), free() int i, j, k; float temperature[100]; If, in addition, no type-define, then void init_temp() { you pretty much for (i=0; i<100; i++) { have the first hightemperature[i] = 0. 0; level programming language: FORTRAN } } l How to program? How about hash table? binary tree? Problems: developing large programs, making errors, being inflexible, managing storage by programmers, … 1

Outline t Evolution of Programming Languages (Ch. 2) l Influences on Language Design (Sec. 1. 4) l Language Categories (Sec. 1. 5) l Programming Domains (Sec. 1. 2) 2

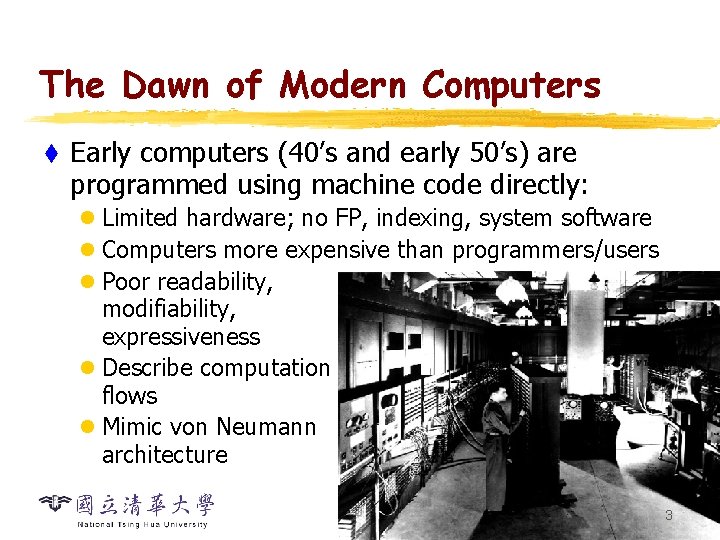

The Dawn of Modern Computers t Early computers (40’s and early 50’s) are programmed using machine code directly: l Limited hardware; no FP, indexing, system software l Computers more expensive than programmers/users l Poor readability, modifiability, expressiveness l Describe computation flows l Mimic von Neumann architecture 3

Early Programming t Programmers have to enter machine code to program the computer l Floating point: coders had to keep track of the exponent manually l Relative addressing: codes had to be adjusted by hand for the absolute addresses l Array subscripting needed l Something easier to remember than octal opcodes t Early aids: l Assembly languages and assemblers: English-like phrases 1 -to-1 representation of machine instructions t Saving programmer time became important … 4

Fortran t First popular high-level programming language l Computers were small and unreliable machine efficiency was most important l Applications were scientific need good array handling and counting loops t "The IBM Mathematical FORmula TRANslating System: FORTRAN", 1954: (John Backus at IBM) l To generate code comparable with hand-written code using simple, primitive compilers l Closely tied to the IBM 704 architecture, which had index registers and floating point hardware 5

Fortran t Fortran I (1957) l Names could have up to six characters, formatted I/O, user-defined subprograms, no data typing l No separate compilation (compiling “large” programs – a few hundred lines – approached 704 MTTF) l Highly optimize code with static types and storage t Later versions evolved with more features and platform independence l Almost all designers learned from Fortran and Fortran team pioneered things such as scanning, parsing, register allocation, code generation, optimization 6

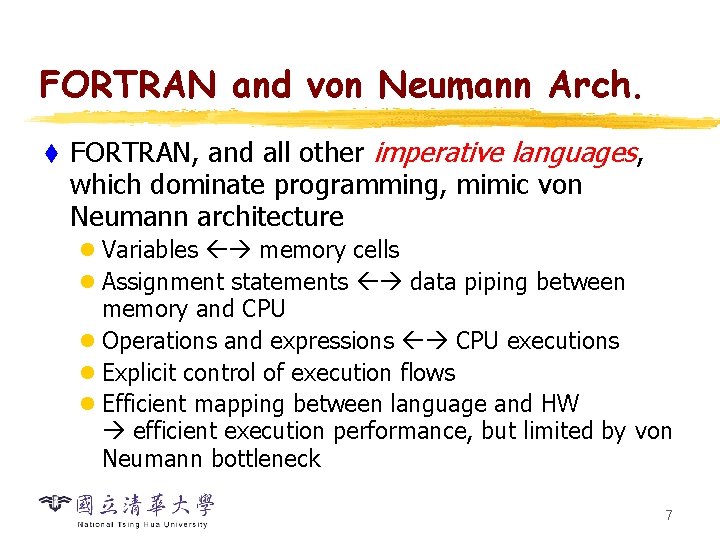

FORTRAN and von Neumann Arch. t FORTRAN, and all other imperative languages, which dominate programming, mimic von Neumann architecture l Variables memory cells l Assignment statements data piping between memory and CPU l Operations and expressions CPU executions l Explicit control of execution flows l Efficient mapping between language and HW efficient execution performance, but limited by von Neumann bottleneck 7

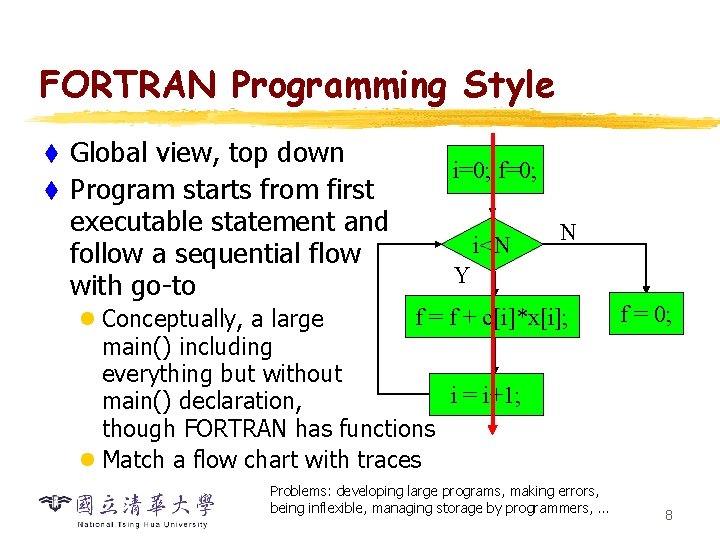

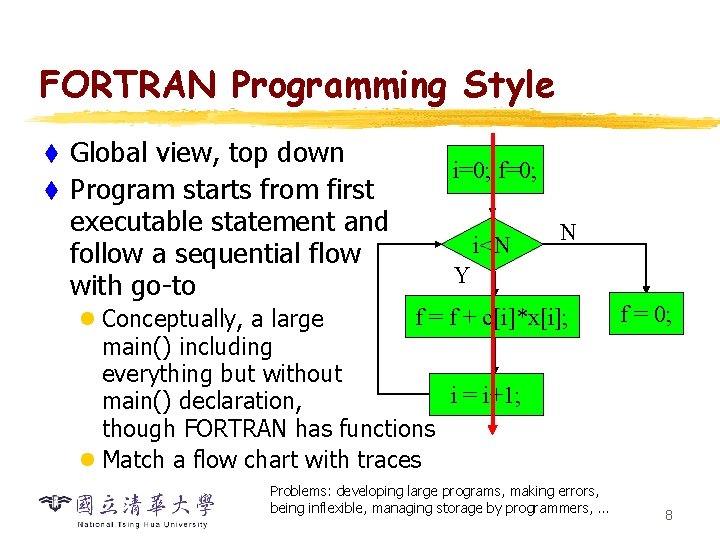

FORTRAN Programming Style Global view, top down t Program starts from first executable statement and follow a sequential flow with go-to t l Conceptually, a large i=0; f=0; i<N N Y f = f + c[i]*x[i]; f = 0; main() including everything but without i = i+1; main() declaration, though FORTRAN has functions l Match a flow chart with traces Problems: developing large programs, making errors, being inflexible, managing storage by programmers, … 8

Functional Programming: LISP t AI research needed a language to l Process data in lists (rather than arrays) l Symbolic computation (rather than numeric) John Mc. Carthy of MIT developed LISP (LISt Processing language) in 1958 t A LISP program is a list: (+ a (* b c)) t l List form both for input and for function l Only two data types: atoms and lists 9

LISP t Example: a factorial function in LISP (defun fact (x) (if (<= x 0) 1 (* x (fact (- x 1))) ) ) t Second-oldest general-purpose programming language still in use l Ideas, e. g. conditional expression, recursion, garbage collection, were adopted by other imperative lang. 10

LISP t Pioneered functional programming l Computations by applying functions to parameters l No concept of variables (storage) or assignment n Single-valued variables: no assignment, not storage l Control via recursion and conditional expressions n Branches conditional expressions n Iterations recursion l Dynamically allocated linked lists 11

First Step Towards Sophistication t Environment (1957 -1958): l FORTRAN had (barely) arrived for IBM 70 x l Many other languages, but all for specific machines no universal lang. for communicating algorithms l Programmer productivity became important t ALGOL: universal, international, machineindependent (imperative) language for expressing scientific algorithms l Eventually, 3 major designs: ALGOL 58, 60, and 68 l Developed by increasingly large international committees 12

Issues to Address (I) t Early languages used label-oriented control: 30 GO TO 27 IF (A-B) 5, 6, 7 ALGOL supports sufficient phrase-level control, such as if, while, switch, for, until structured programming t Programming style: t l Programs consist of blocks of code: blocks functions files directories l Bottom-up development possible l Easy to develop, read, maintain; make fewer errors 13

Issues to Address (II) t ALGOL designs avoided special cases: l Free-format lexical structure l No arbitrary limits: n Any number of characters in a name n Any number of dimensions for an array l Orthogonality: every meaningful combination of primitive concepts is legal—no special forbidden combinations to remember n Each combination not permitted is a special case that must be remembered by the programmer 14

Example of Orthogonality Integers Arrays Procedures Passing as a parameter Storing in a variable Storing in an array Returning from a procedure By ALGOL 68, all combinations above are legal t Modern languages seldom take this principle as far as ALGOL expressiveness vs efficiency t 15

Influences t Virtually all languages after 1958 used ideas pioneered by the ALGOL designs: l Free-format lexical structure l No limit to length of names and array dimension l BNF definition of syntax l Concept of type l Block structure (local scope) l Compound stmt (begin end), nested if-then-else l Stack-dynamic arrays l Call by value (and call by name) l Recursive subroutines and conditional expressions 16

Beginning of Timesharing: BASIC t BASIC (Beginner’s All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) l Kemeny & Kurtz at Dartmouth, 1963 t Design goals: l Easy to learn and use for non-science students l Must be “pleasant and friendly” l Fast turnaround for homework l Free and private access l User time is more important than computer time t First widely used language with time sharing l Simultaneous individual access through terminals 17

Everything for Everybody: PL/I t IBM at 1963 -1964: l Scientific computing: IBM 1620 and 7090, FORTRAN l Business computing: IBM 1401 and 7080, COBOL l Scientific users began to need elaborate I/O, like in COBOL; business users began to need FP and arrays t The obvious solution l New computer to do both IBM System/360 l Design a new language to do both PL/I t Results: l Unit-level concurrency, exception handling, pointer l But, too many and too complex 18

Beginning of Data Abstraction t SIMULA l Designed primarily for system simulation in University of Oslo, Norway, by Nygaard and Dahl Starting 1961: SIMULA I, SIMULA 67 t Primary contributions t l Co-routines: a kind of subprogram l Implemented in a structure called a class, which include both local data and functionality and are the basis for data abstraction 19

Object-Oriented Programming Smalltalk: Alan Kay, Xerox PARC, 1972 t First full implementation of an object-oriented language t l Everything is an object: variables, constants, activation records, classes, etc. l All computation is performed by objects sending and receiving messages l Data abstraction, inheritance, dynamic type binding t Also pioneered graphical user interface design Dynabook (1972) 20

Programming Based on Logic: Prolog Developed by Comerauer and Roussel (University of Aix-Marseille) in 1972, with help from Kowalski (University of Edinburgh) t Based on formal logic t Non-procedural t l Only supply relevant facts (predicate calculus) and inference rules (resolutions) l System then infer the truth of given queries/goals t Highly inefficient, small application areas (database, AI) 21

Logic Languages t Example: relationship among people fact: mother(joanne, jake). father(vern, joanne). rule: grandparent(X, Z) : - parent(X, Y), parent(Y, Z). grandparent(vern, jake). goal: t Features of logic languages (Prolog): l Program expressed as rules in formal logic l Execution by rule resolution 22

Genealogy of Common Languages (Fig. 2. 1) 23

Summary: Application Domain t Application domains have distinctive (and conflicting) needs and affect prog. lang. l Scientific applications: high performance with a large number of floating point computations, e. g. , Fortran l Business applications: report generation that use decimal numbers and characters, e. g. , COBOL l Artificial intelligence: symbols rather than numbers manipulated, e. g. , LISP l Systems programming: low-level access and efficiency for SW interface to devices, e. g. , C l Web software: diff. kinds of lang. markup (XHTML), scripting (PHP), general-purpose (Java) 24

Summary: Programming Methodology in Perspective 1950 s and early 1960 s: simple applications; worry about machine efficiency (FORTRAN) t Late 1960 s: people efficiency important; readability, better control structures (ALGOL) t l Structured programming l Top-down design and step-wise refinement t Late 1970 s: process-oriented to data-oriented l Data abstraction t Middle 1980 s: object-oriented programming l Data abstraction + inheritance + dynamic binding 25

Theory of PL: Turing Equivalence t Languages have different strengths, but fundamentally they all have the same power {problems solvable in Java} = {problems solvable in Fortran} =… t And all have the same power as various mathematical models of computation = {problems solvable by Turing machine} = {problems solvable by lambda calculus} =… t Church-Turing thesis: this is what “computability” means 26