CS 140 Introduction to Computer Systems Kenneth Louden

- Slides: 20

CS 140 Introduction to Computer Systems Kenneth Louden (adapted from http: //csapp. cs. cmu. edu/public/lectures. html) slides 01. ppt CS 140 Spring, 2006

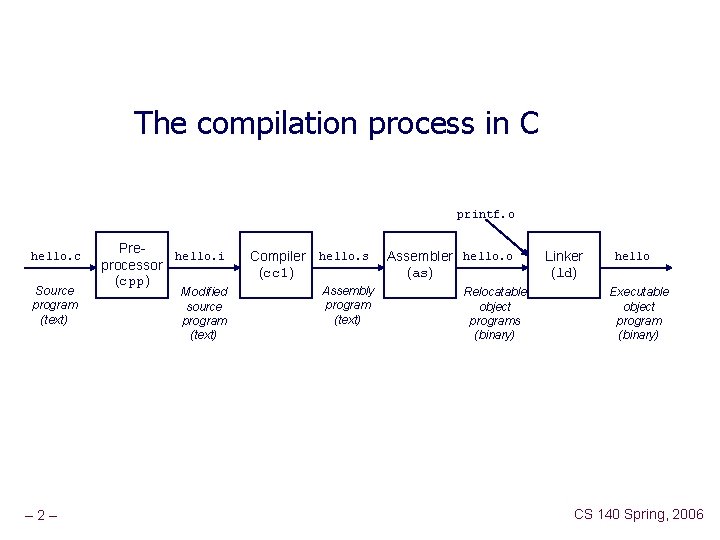

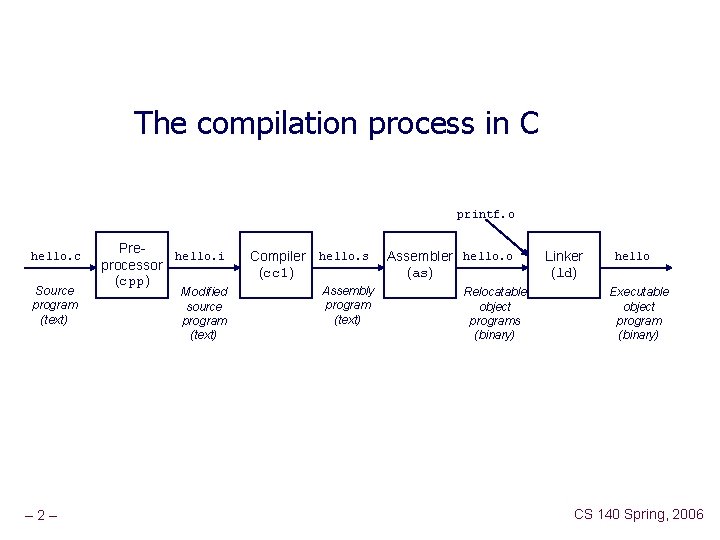

The compilation process in C printf. o hello. c Source program (text) – 2– Prehello. i processor (cpp) Modified source program (text) Compiler hello. s (cc 1) Assembly program (text) Assembler hello. o (as) Relocatable object programs (binary) Linker (ld) hello Executable object program (binary) CS 140 Spring, 2006

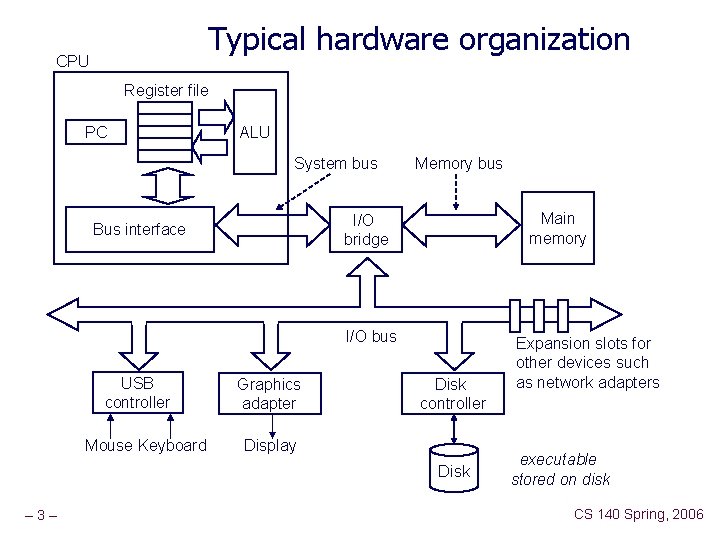

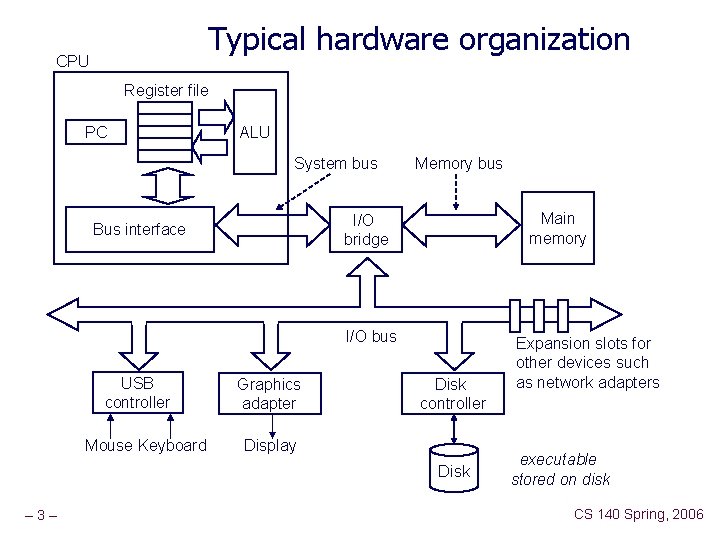

Typical hardware organization CPU Register file PC ALU System bus Memory bus Main memory I/O bridge Bus interface I/O bus USB controller Mouse Keyboard Graphics adapter Disk controller Display Disk – 3– Expansion slots for other devices such as network adapters executable stored on disk CS 140 Spring, 2006

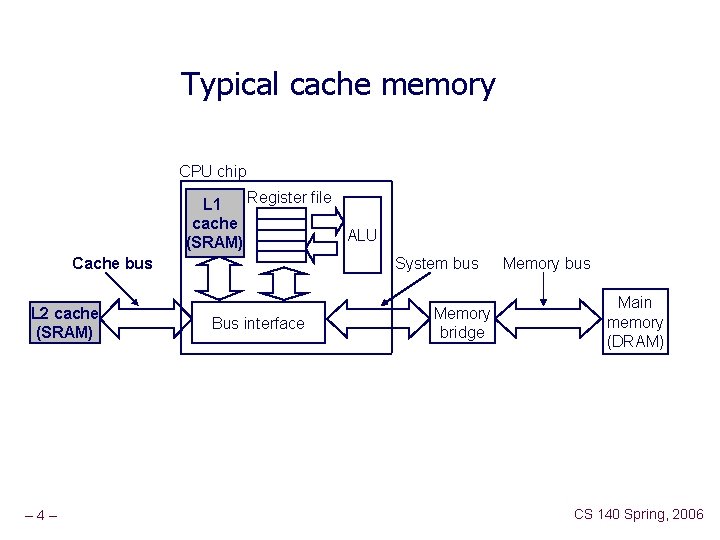

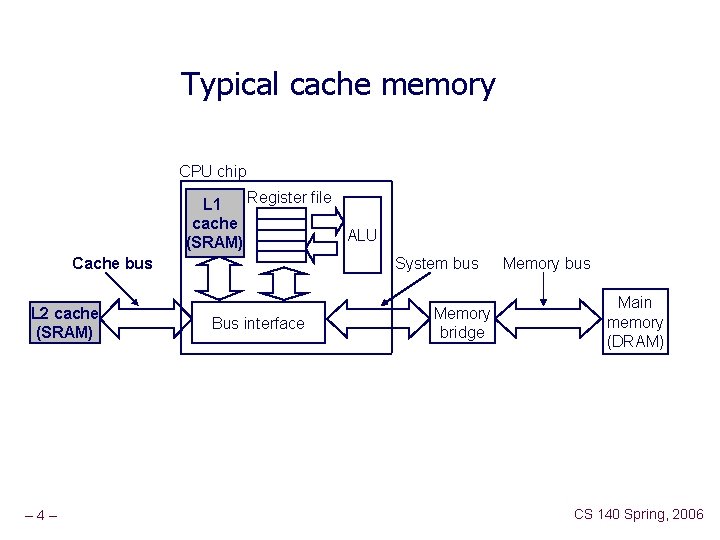

Typical cache memory CPU chip Register file L 1 cache ALU (SRAM) Cache bus L 2 cache (SRAM) – 4– System bus Bus interface Memory bridge Memory bus Main memory (DRAM) CS 140 Spring, 2006

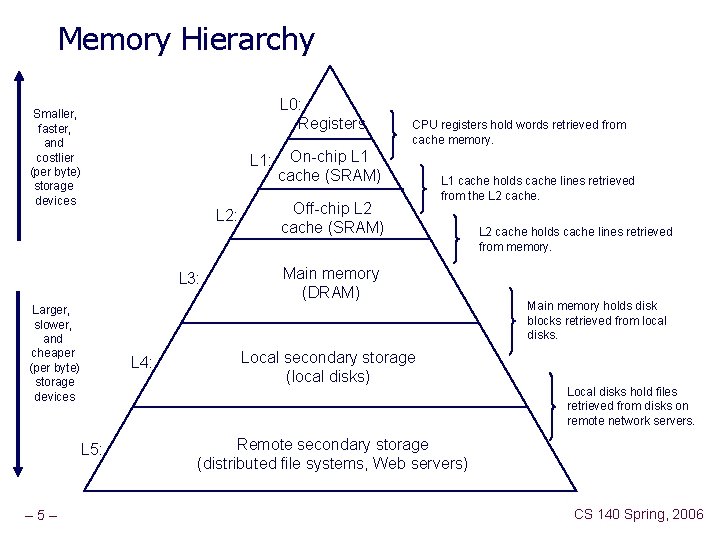

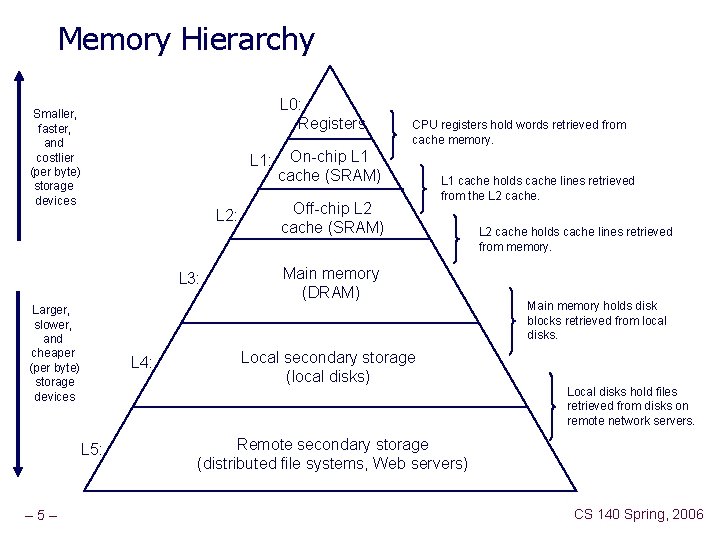

Memory Hierarchy L 0: Registers Smaller, faster, and costlier (per byte) storage devices L 1: L 2: L 3: Larger, slower, and cheaper (per byte) storage devices L 4: L 5: – 5– CPU registers hold words retrieved from cache memory. On-chip L 1 cache (SRAM) Off-chip L 2 cache (SRAM) L 1 cache holds cache lines retrieved from the L 2 cache. Main memory (DRAM) Local secondary storage (local disks) L 2 cache holds cache lines retrieved from memory. Main memory holds disk blocks retrieved from local disks. Local disks hold files retrieved from disks on remote network servers. Remote secondary storage (distributed file systems, Web servers) CS 140 Spring, 2006

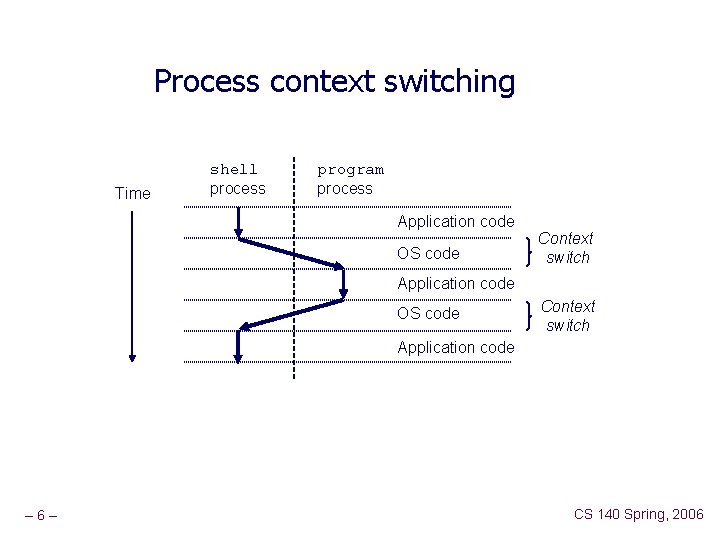

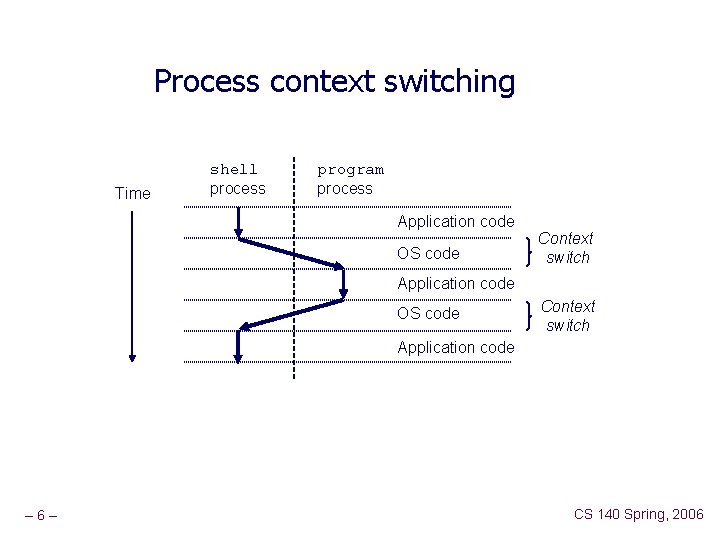

Process context switching Time shell process program process Application code OS code Context switch Application code – 6– CS 140 Spring, 2006

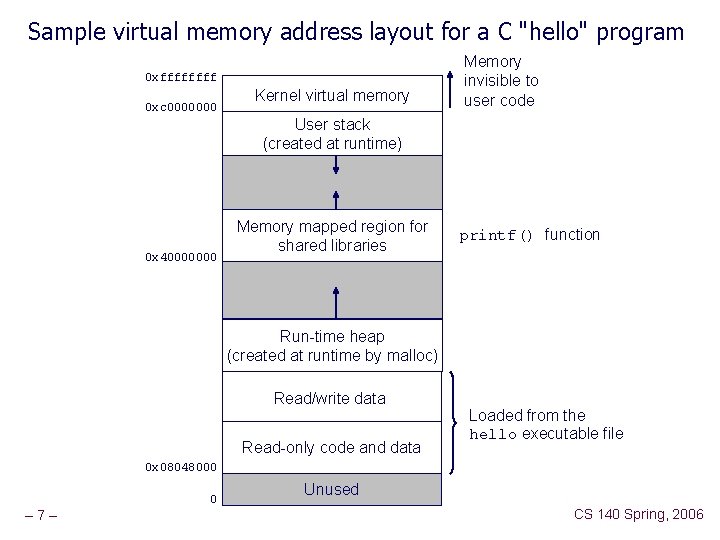

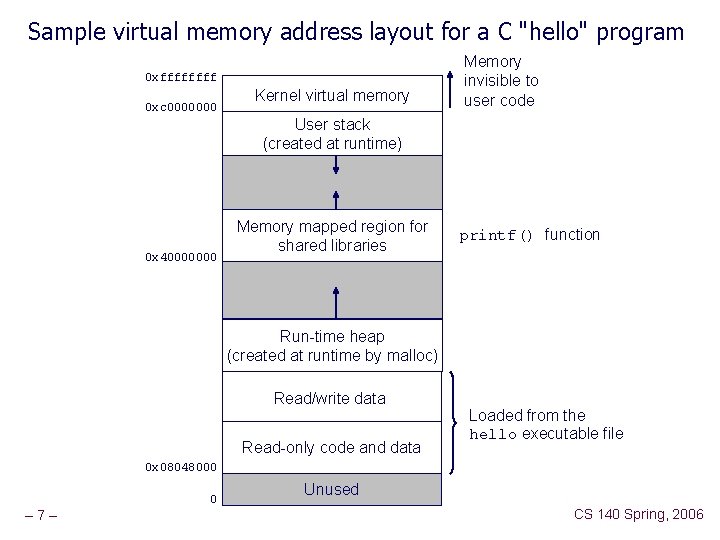

Sample virtual memory address layout for a C "hello" program 0 xffff 0 xc 0000000 Kernel virtual memory Memory invisible to user code User stack (created at runtime) 0 x 40000000 Memory mapped region for shared libraries printf() function Run-time heap (created at runtime by malloc) Read/write data Read-only code and data Loaded from the hello executable file 0 x 08048000 0 – 7– Unused CS 140 Spring, 2006

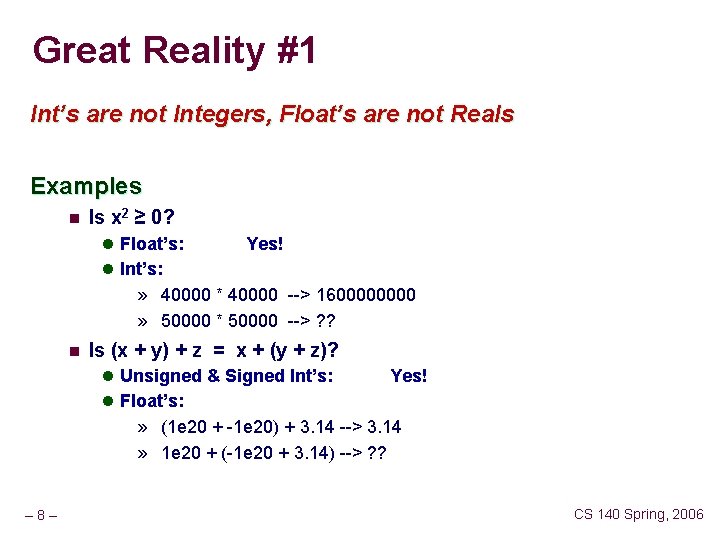

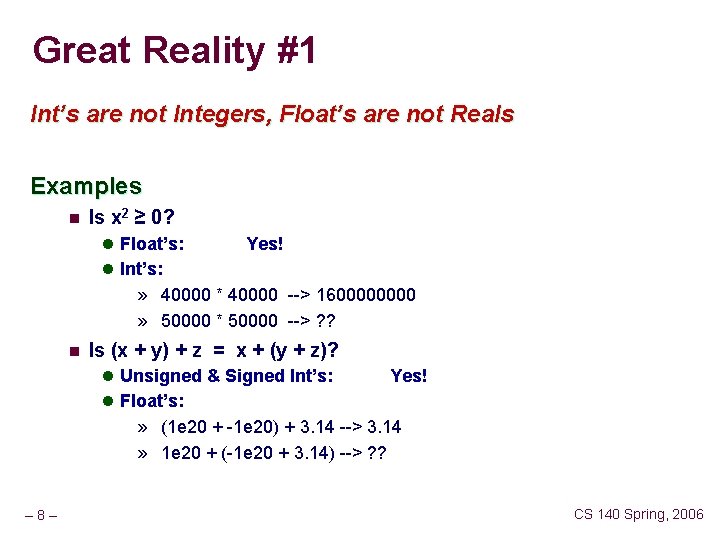

Great Reality #1 Int’s are not Integers, Float’s are not Reals Examples n Is x 2 ≥ 0? l Float’s: Yes! l Int’s: » 40000 * 40000 --> 160000 » 50000 * 50000 --> ? ? n Is (x + y) + z = x + (y + z)? l Unsigned & Signed Int’s: Yes! l Float’s: » (1 e 20 + -1 e 20) + 3. 14 --> 3. 14 » 1 e 20 + (-1 e 20 + 3. 14) --> ? ? – 8– CS 140 Spring, 2006

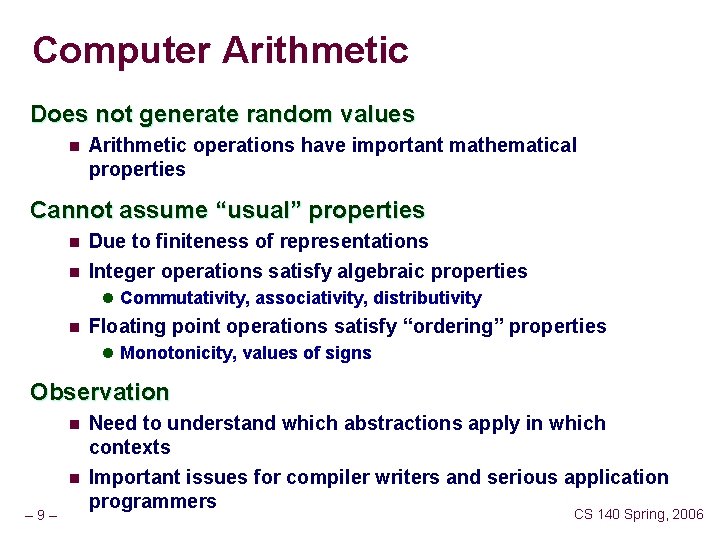

Computer Arithmetic Does not generate random values n Arithmetic operations have important mathematical properties Cannot assume “usual” properties n n Due to finiteness of representations Integer operations satisfy algebraic properties l Commutativity, associativity, distributivity n Floating point operations satisfy “ordering” properties l Monotonicity, values of signs Observation n n – 9– Need to understand which abstractions apply in which contexts Important issues for compiler writers and serious application programmers CS 140 Spring, 2006

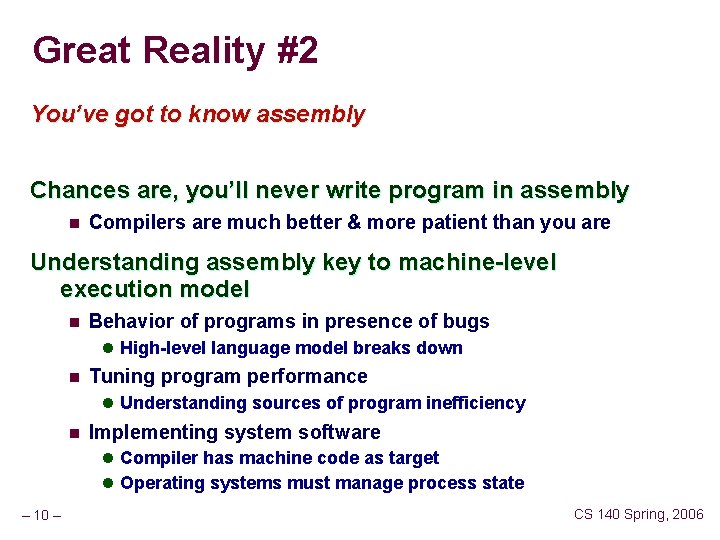

Great Reality #2 You’ve got to know assembly Chances are, you’ll never write program in assembly n Compilers are much better & more patient than you are Understanding assembly key to machine-level execution model n Behavior of programs in presence of bugs l High-level language model breaks down n Tuning program performance l Understanding sources of program inefficiency n Implementing system software l Compiler has machine code as target l Operating systems must manage process state – 10 – CS 140 Spring, 2006

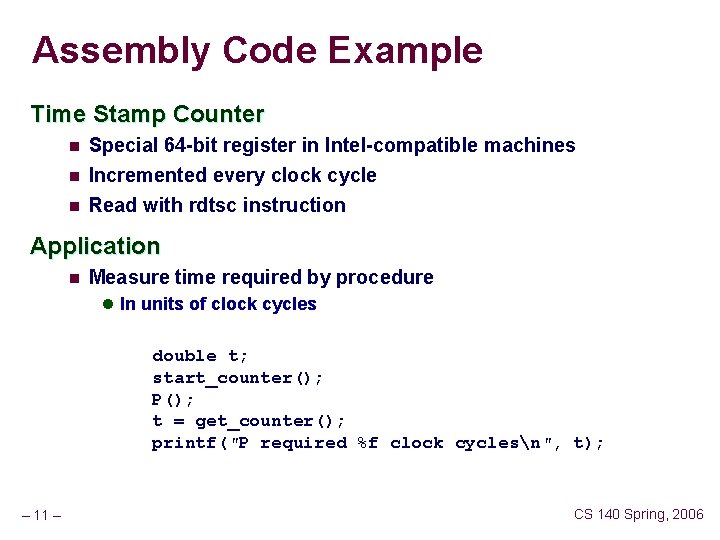

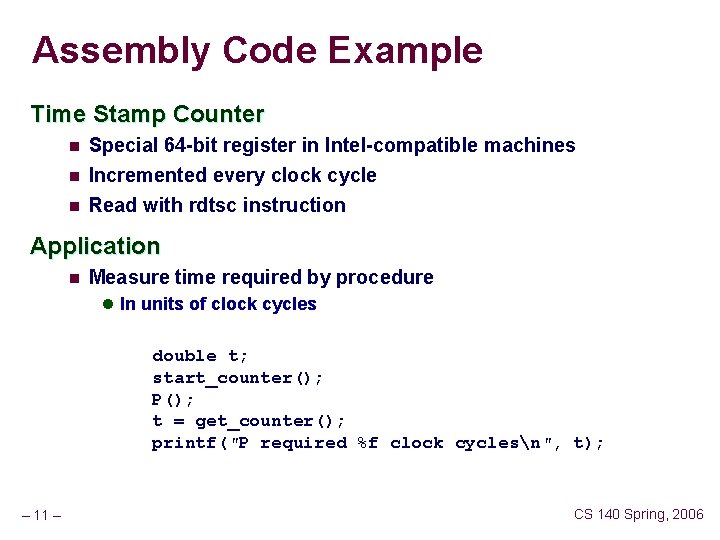

Assembly Code Example Time Stamp Counter n Special 64 -bit register in Intel-compatible machines n Incremented every clock cycle Read with rdtsc instruction n Application n Measure time required by procedure l In units of clock cycles double t; start_counter(); P(); t = get_counter(); printf("P required %f clock cyclesn", t); – 11 – CS 140 Spring, 2006

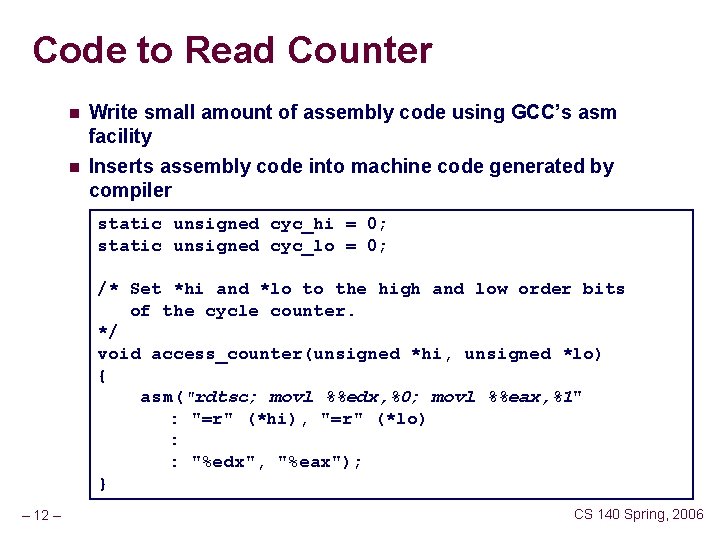

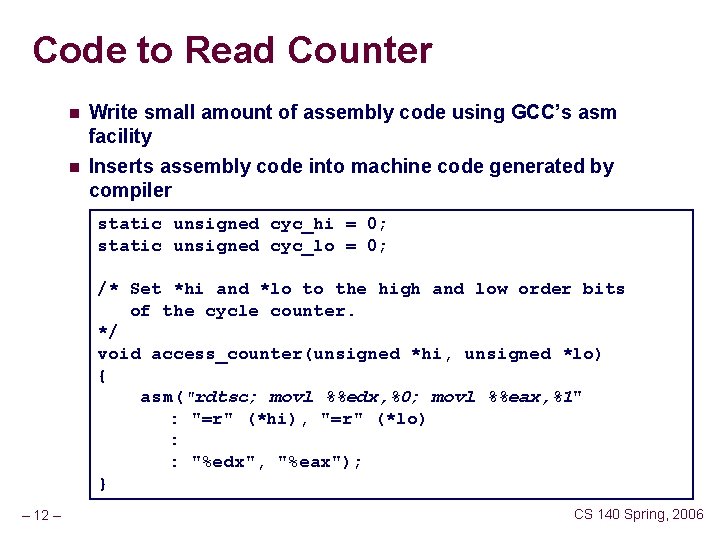

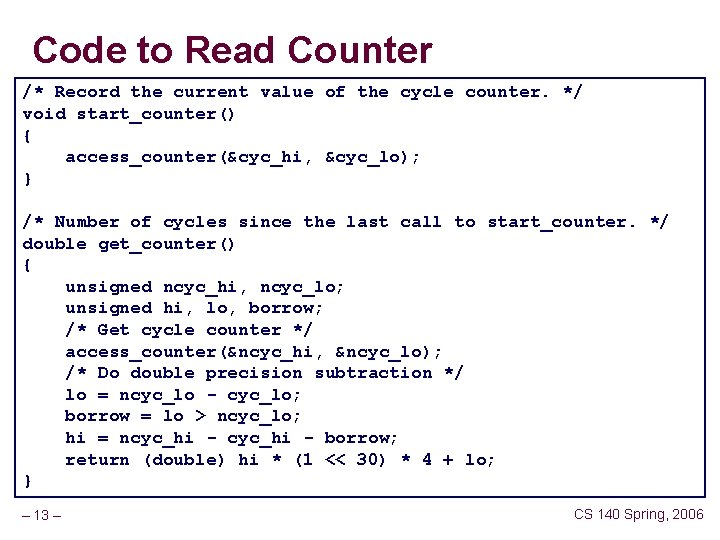

Code to Read Counter n Write small amount of assembly code using GCC’s asm facility n Inserts assembly code into machine code generated by compiler static unsigned cyc_hi = 0; static unsigned cyc_lo = 0; /* Set *hi and *lo to the high and low order bits of the cycle counter. */ void access_counter(unsigned *hi, unsigned *lo) { asm("rdtsc; movl %%edx, %0; movl %%eax, %1" : "=r" (*hi), "=r" (*lo) : : "%edx", "%eax"); } – 12 – CS 140 Spring, 2006

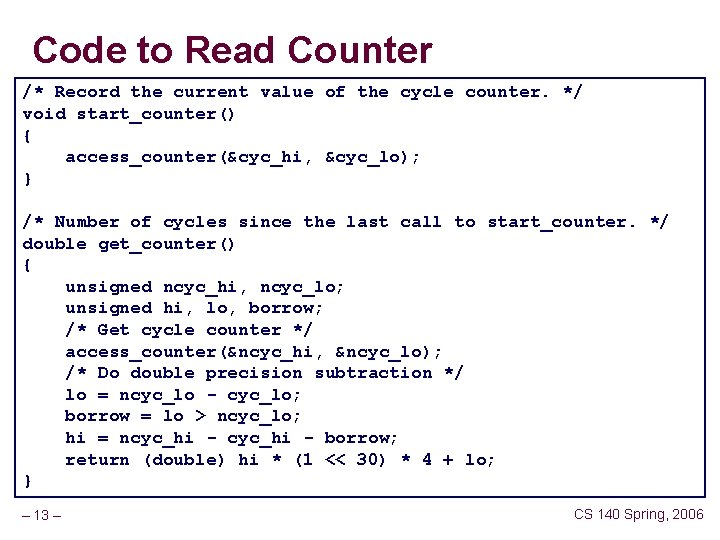

Code to Read Counter /* Record the current value of the cycle counter. */ void start_counter() { access_counter(&cyc_hi, &cyc_lo); } /* Number of cycles since the last call to start_counter. */ double get_counter() { unsigned ncyc_hi, ncyc_lo; unsigned hi, lo, borrow; /* Get cycle counter */ access_counter(&ncyc_hi, &ncyc_lo); /* Do double precision subtraction */ lo = ncyc_lo - cyc_lo; borrow = lo > ncyc_lo; hi = ncyc_hi - borrow; return (double) hi * (1 << 30) * 4 + lo; } – 13 – CS 140 Spring, 2006

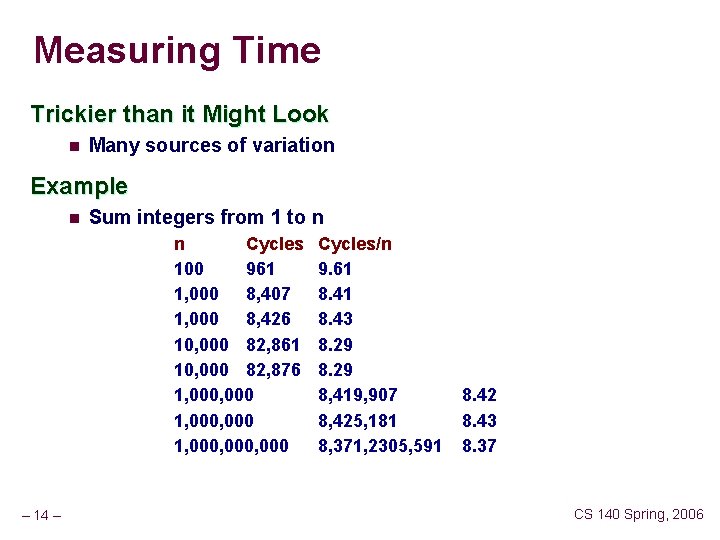

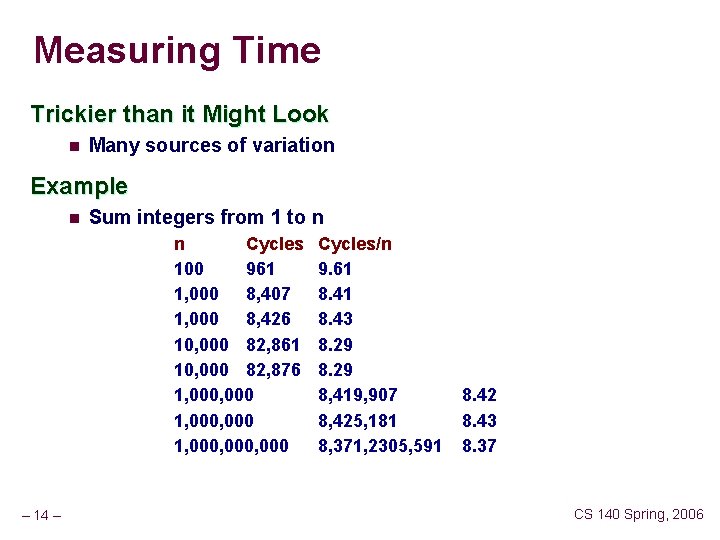

Measuring Time Trickier than it Might Look n Many sources of variation Example n Sum integers from 1 to n n Cycles 100 961 1, 000 8, 407 1, 000 8, 426 10, 000 82, 861 10, 000 82, 876 1, 000, 000 – 14 – Cycles/n 9. 61 8. 43 8. 29 8, 419, 907 8, 425, 181 8, 371, 2305, 591 8. 42 8. 43 8. 37 CS 140 Spring, 2006

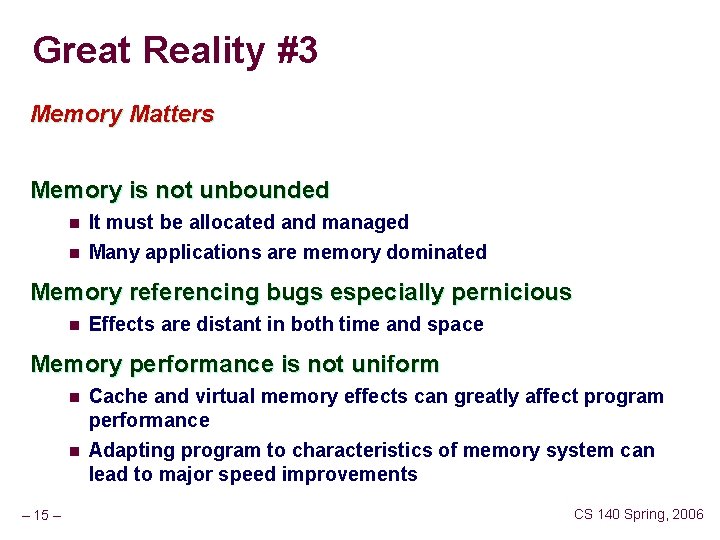

Great Reality #3 Memory Matters Memory is not unbounded n n It must be allocated and managed Many applications are memory dominated Memory referencing bugs especially pernicious n Effects are distant in both time and space Memory performance is not uniform n n – 15 – Cache and virtual memory effects can greatly affect program performance Adapting program to characteristics of memory system can lead to major speed improvements CS 140 Spring, 2006

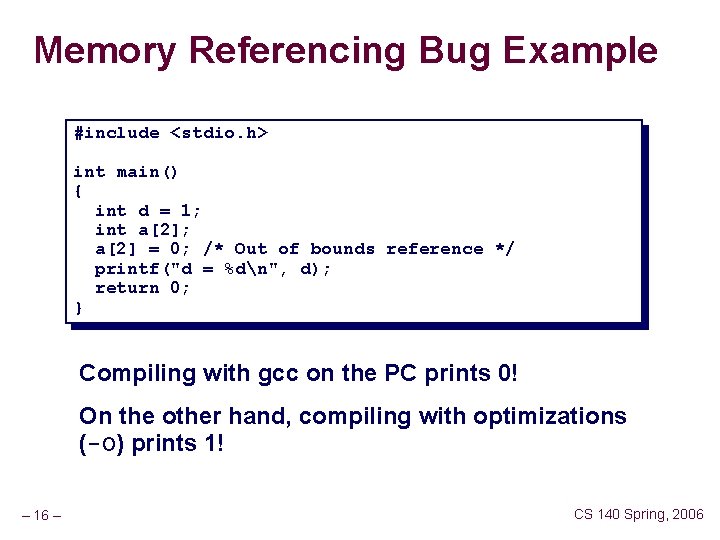

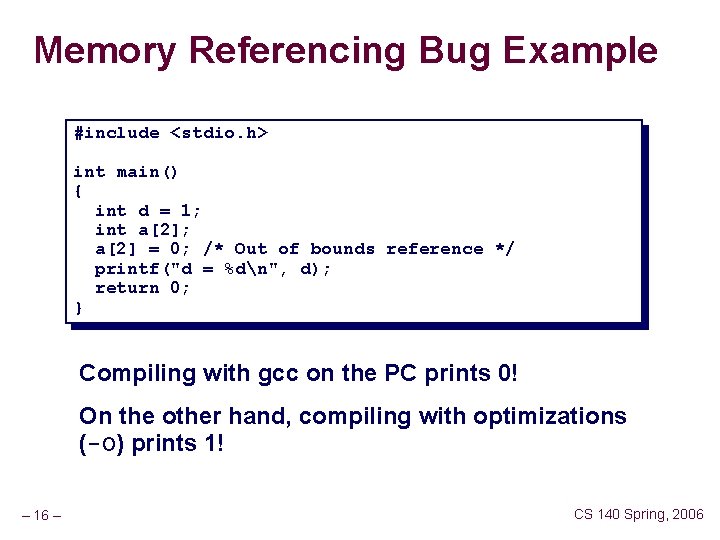

Memory Referencing Bug Example #include <stdio. h> int main() { int d = 1; int a[2]; a[2] = 0; /* Out of bounds reference */ printf("d = %dn", d); return 0; } Compiling with gcc on the PC prints 0! On the other hand, compiling with optimizations (-O) prints 1! – 16 – CS 140 Spring, 2006

Memory Referencing Errors C and C++ do not provide any memory protection n Out of bounds array references n Invalid pointer values Abuses of malloc/free n Can lead to nasty bugs n n Whether or not bug has any effect depends on system and compiler Action at a distance l Corrupted object logically unrelated to one being accessed l Effect of bug may be first observed long after it is generated How can I deal with this? n n – 17 – n Program in Java, Lisp, or ML Understand what possible interactions may occur Use or develop tools to detect referencing errors CS 140 Spring, 2006

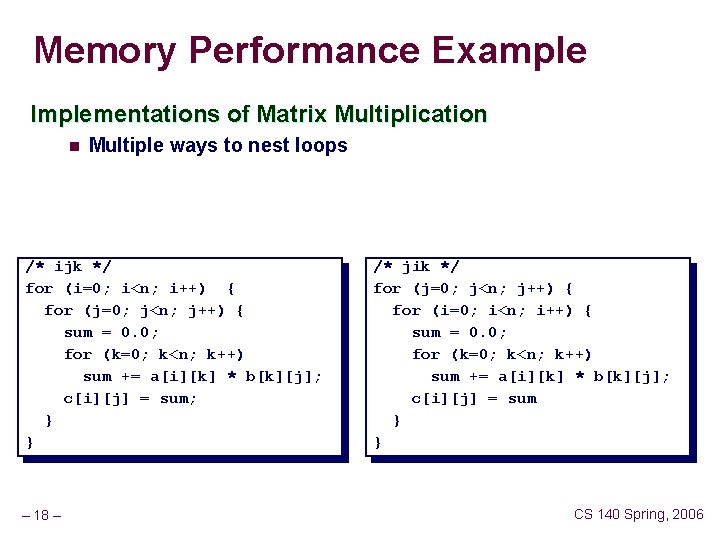

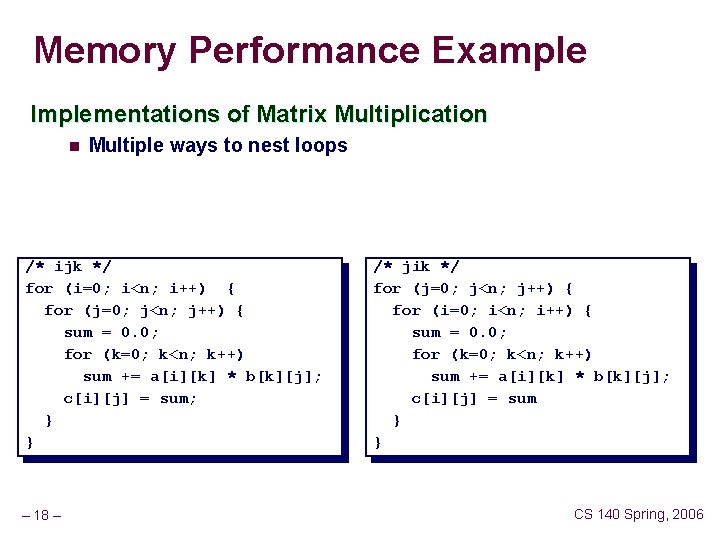

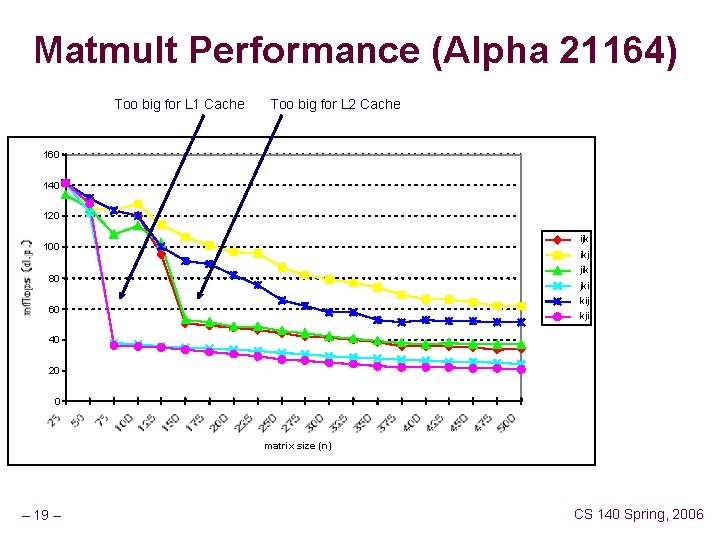

Memory Performance Example Implementations of Matrix Multiplication n Multiple ways to nest loops /* ijk */ for (i=0; i<n; i++) { for (j=0; j<n; j++) { sum = 0. 0; for (k=0; k<n; k++) sum += a[i][k] * b[k][j]; c[i][j] = sum; } } – 18 – /* jik */ for (j=0; j<n; j++) { for (i=0; i<n; i++) { sum = 0. 0; for (k=0; k<n; k++) sum += a[i][k] * b[k][j]; c[i][j] = sum } } CS 140 Spring, 2006

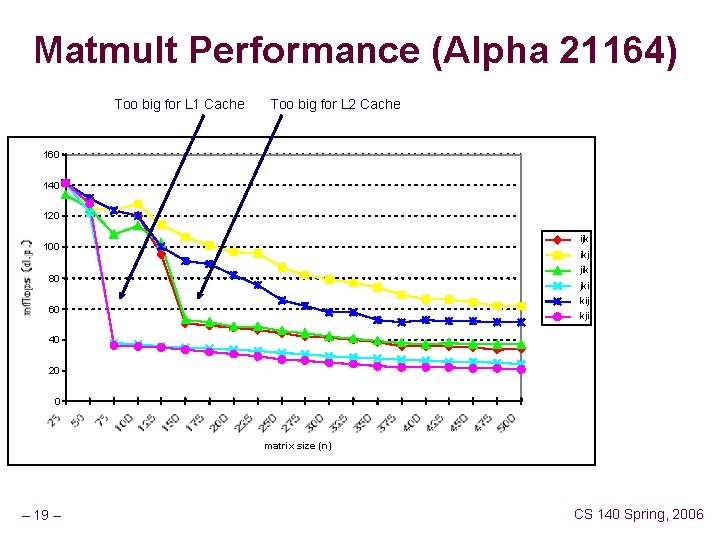

Matmult Performance (Alpha 21164) Too big for L 1 Cache Too big for L 2 Cache 160 140 120 ijk 100 ikj jik 80 jki kij 60 kji 40 20 0 matrix size (n) – 19 – CS 140 Spring, 2006

Great Reality #4 There’s more to performance than asymptotic complexity Constant factors matter too! n n Easily see 10: 1 performance range depending on how code written Must optimize at multiple levels: algorithm, data representations, procedures, and loops Must understand system to optimize performance n n n – 20 – How programs compiled and executed How to measure program performance and identify bottlenecks How to improve performance without destroying code modularity and generality CS 140 Spring, 2006