Critical Thinking Chapter 11 Inductive Reasoning Lecture Notes

- Slides: 46

Critical Thinking Chapter 11 Inductive Reasoning Lecture Notes © 2008 Mc. Graw Hill Higher Education 1

Introduction ¡ ¡ Inductive Argument: an argument in which the premises are intended to provide support, but not conclusive evidence, for the conclusion. Strong Inductive Argument: an inductive argument in which the premises actually do make the conclusion more likely to be true (rather than false). l Remember, strength comes in degrees. Cogent Inductive Argument: a strong inductive argument with true premises. How can you know if the argument is inductive? l If the argument is invalid, the charitable thing to do is treat it as inductive. l Indicator words: likely, probably, it’s plausible to suppose that, etc. 2

Inductive Generalizations ¡ ¡ Generalization: statement made about all or most members of a group. Inductive generalization: inductive argument that relies on characteristics of a sample population (i. e. , a portion of the population) to make a claim about the population as a whole. l ¡ i. e. , an inductive argument with a generalization as a conclusion. Example: All the bass Hank caught in the Susquehanna have been less than 1 lb. So, most of the bass in the Susquehanna are less than 1 lb. 3

Making Inductive Generalizations stronger by making conclusions weaker. ¡ Notice… l ¡ ¡ All the bass Hank caught in the Susquehanna have been less than 1 lb. So, all of the bass in the Susquehanna are less than 1 lb. . . is a pretty weak argument. Even if Hank fishes often, the Susquehanna is a big river and his catches are not enough to justify such a “sweeping conclusion. ” However, if we changed the conclusion to “most of the bass are…” or, better yet, “many of the bass are…” the argument would be much stronger. 4

Practice ¡ Page 288, Exercise 11. 1 5

Evaluating Inductive Generalizations ¡ ¡ ¡ Three questions to ask: Are the premises true? Use the skills you learned in chapter 8 to determine whether you are justified in accepting the premises. Is the sample large enough? In general, the larger the population you are generalizing about, the larger your “sample population” will need to be. Is the sample representative? Only if the sample shares all the relevant “percentages” with the population as a whole. l Maybe Hank only fished with lures that were attractive to smaller fish. 6

Are the premises true? A deductive argument that is valid and has all true premises leading to a true conclusion is called a sound argument ¡ A deductive argument can have good – that is, valid – argumentation and still be unsound if the premises are not all true. ¡ So, likewise an inductive argument…. ¡ l 7

Are the premises true? Premises of an inductive generalization can provide strong support for its conclusion ¡ But if the premises are not all true, it is not a cogent inductive argument. ¡ A cogent argument has all true premises and supplies strong support for its conclusions. ¡ 8

Are the premises true? ¡ One or more false premises makes an inductive argument uncogent, even if its argumentation, its support for the conclusion, is strong. l l l Most CEOs of Fortune 500 companies are women. So, the CEOs of most big businesses are probably women. Weak 9

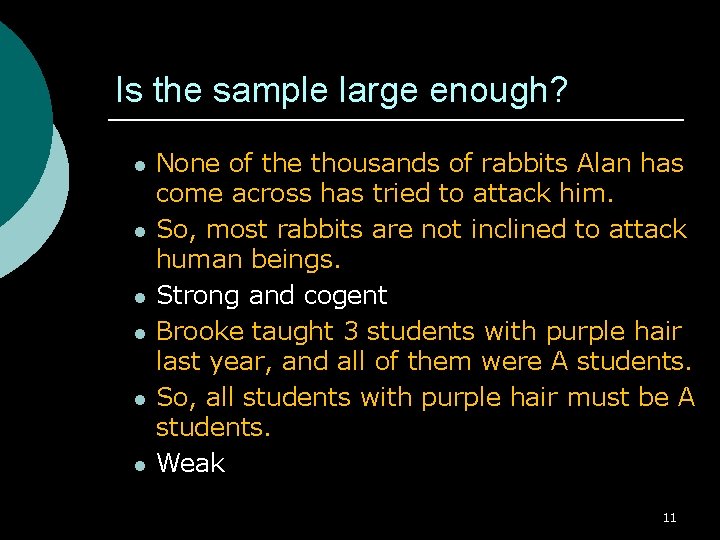

Is the sample large enough? The size of the sample population must be sufficient to justify the conclusion about the population as a whole. ¡ If it is not, the argument is a hasty generalization. ¡ 10

Is the sample large enough? l l l None of the thousands of rabbits Alan has come across has tried to attack him. So, most rabbits are not inclined to attack human beings. Strong and cogent Brooke taught 3 students with purple hair last year, and all of them were A students. So, all students with purple hair must be A students. Weak 11

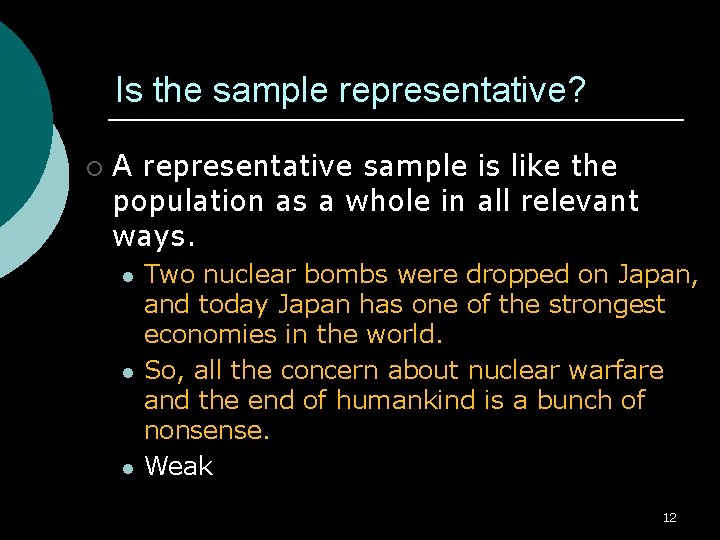

Is the sample representative? ¡ A representative sample is like the population as a whole in all relevant ways. l l l Two nuclear bombs were dropped on Japan, and today Japan has one of the strongest economies in the world. So, all the concern about nuclear warfare and the end of humankind is a bunch of nonsense. Weak 12

Practice ¡ Pages 291 -92, Exercise 11. 2 Lecture Notes © 2008 Mc. Graw Hill Higher Education 13

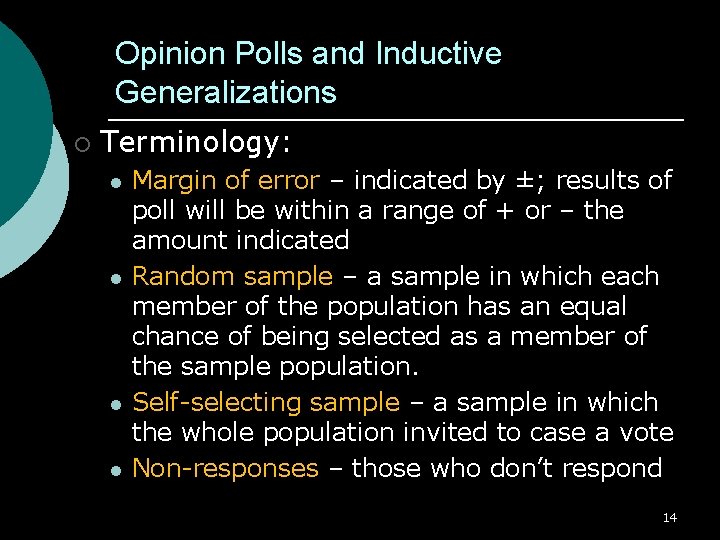

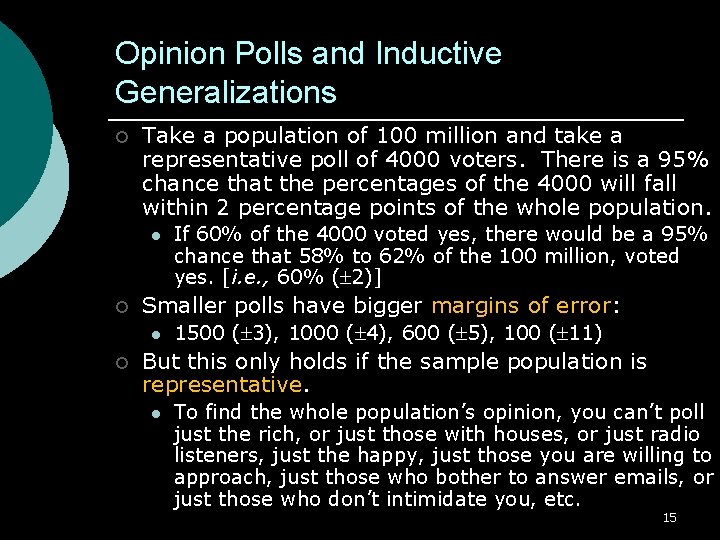

Opinion Polls and Inductive Generalizations ¡ Terminology: l l Margin of error – indicated by ±; results of poll will be within a range of + or – the amount indicated Random sample – a sample in which each member of the population has an equal chance of being selected as a member of the sample population. Self-selecting sample – a sample in which the whole population invited to case a vote Non-responses – those who don’t respond 14

Opinion Polls and Inductive Generalizations ¡ Take a population of 100 million and take a representative poll of 4000 voters. There is a 95% chance that the percentages of the 4000 will fall within 2 percentage points of the whole population. l ¡ Smaller polls have bigger margins of error: l ¡ If 60% of the 4000 voted yes, there would be a 95% chance that 58% to 62% of the 100 million, voted yes. [i. e. , 60% ( 2)] 1500 ( 3), 1000 ( 4), 600 ( 5), 100 ( 11) But this only holds if the sample population is representative. l To find the whole population’s opinion, you can’t poll just the rich, or just those with houses, or just radio listeners, just the happy, just those you are willing to approach, just those who bother to answer emails, or just those who don’t intimidate you, etc. 15

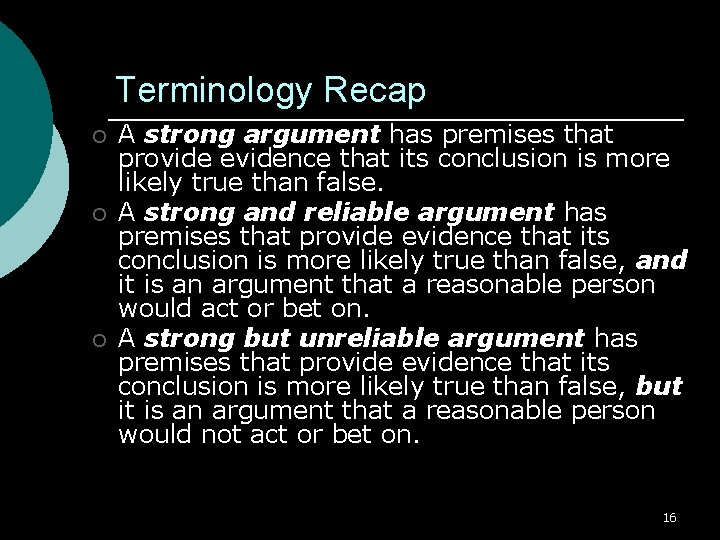

Terminology Recap ¡ ¡ ¡ A strong argument has premises that provide evidence that its conclusion is more likely true than false. A strong and reliable argument has premises that provide evidence that its conclusion is more likely true than false, and it is an argument that a reasonable person would act or bet on. A strong but unreliable argument has premises that provide evidence that its conclusion is more likely true than false, but it is an argument that a reasonable person would not act or bet on. 16

Practice ¡ Page 296, Exercise 11. 3 17

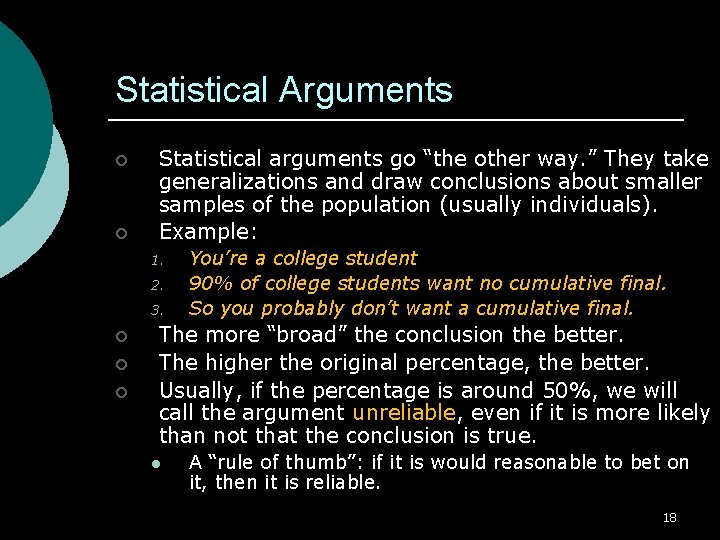

Statistical Arguments ¡ ¡ Statistical arguments go “the other way. ” They take generalizations and draw conclusions about smaller samples of the population (usually individuals). Example: 1. 2. 3. ¡ ¡ ¡ You’re a college student 90% of college students want no cumulative final. So you probably don’t want a cumulative final. The more “broad” the conclusion the better. The higher the original percentage, the better. Usually, if the percentage is around 50%, we will call the argument unreliable, even if it is more likely than not that the conclusion is true. l A “rule of thumb”: if it is would reasonable to bet on it, then it is reliable. 18

Reference Class ¡ ¡ ¡ The reference class is the group to which statistics apply. As a rule, the more specific the reference class is, the better the argument is. A statistical argument can be used to support a conclusion about a group rather than an individual. l l 90% of college students are in favor of not having a final exam. So, 90% of Ling 21 students are in favor of not having a final exam. 19

Reference Class ¡ ¡ In a statistical argument, if you find out more information about the person in question, you “narrow” the group (class) the person is in. Example: 1. 2. 3. ¡ You are a college student who likes essays. 85% of college students who like essays want cumulative fails. Thus you probably want a cumulative final. This additional information weakened our justification for believing that you don’t want a final. Lecture Notes © 2008 Mc. Graw Hill Higher Education 20

Practice ¡ Pages 301 -302, Exercise 11. 4 21

Argument by Analogy ¡ ¡ ¡ Analogy: comparison of things based on similarities. Argument from analogy: an argument that suggests that the presence of certain similarities is evidence for further similarities. Common Form: 1. 2. 3. ¡ A and B have characteristic X A has characteristic Y So B probably has characteristic Y too. Example: 1. 2. 3. Tiffany and Heather are both tall and play basketball. Tiffany also plays volleyball. So, Heather probably plays volleyball too. Lecture Notes © 2008 Mc. Graw Hill Higher Education 22

Evaluating Arguments from Analogy Most arguments from analogy are inductive arguments, so they are neither valid nor invalid. ¡ Unlike deductive arguments, there are no clear-cut ways to tell if inductive arguments are strong or weak. ¡ But there are good questions to ask to help determine if an argument from analogy is strong or weak. ¡ 23

Evaluating Arguments from Analogy l l l Squirrels and rats are rodents of similar size and appearance. Rats cause problems in the city, and squirrels cause problems in the suburbs. Rats should be exterminated. So, squirrels should be exterminated. Is this a good argument? 24

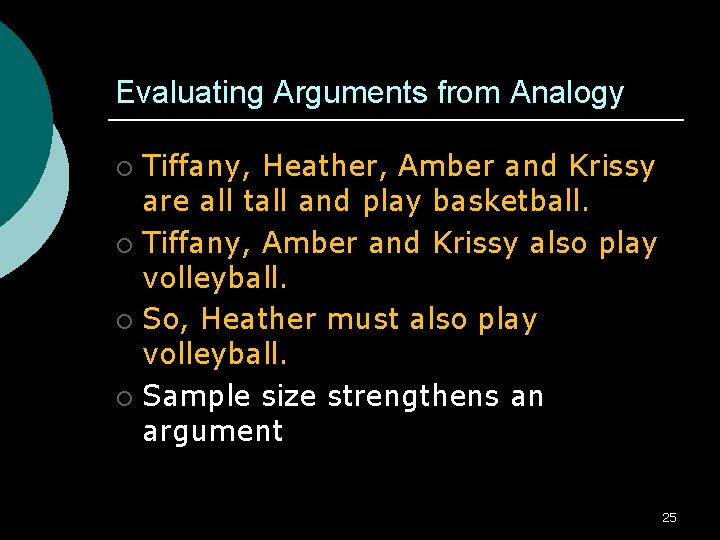

Evaluating Arguments from Analogy Tiffany, Heather, Amber and Krissy are all tall and play basketball. ¡ Tiffany, Amber and Krissy also play volleyball. ¡ So, Heather must also play volleyball. ¡ Sample size strengthens an argument ¡ 25

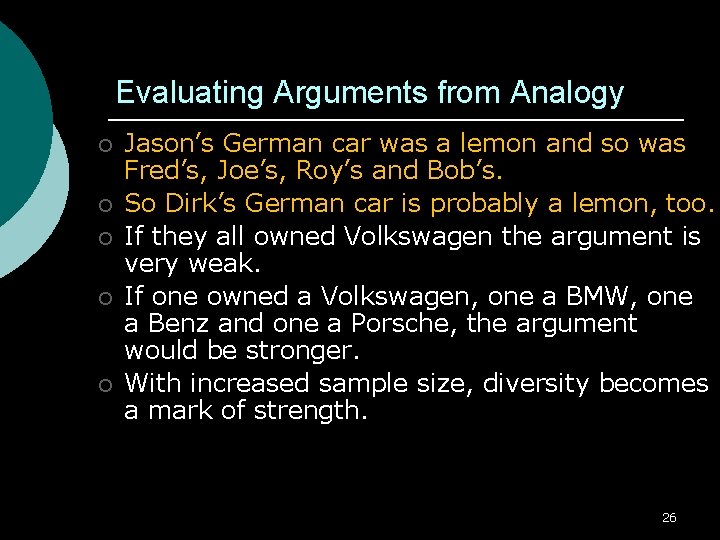

Evaluating Arguments from Analogy ¡ ¡ ¡ Jason’s German car was a lemon and so was Fred’s, Joe’s, Roy’s and Bob’s. So Dirk’s German car is probably a lemon, too. If they all owned Volkswagen the argument is very weak. If one owned a Volkswagen, one a BMW, one a Benz and one a Porsche, the argument would be stronger. With increased sample size, diversity becomes a mark of strength. 26

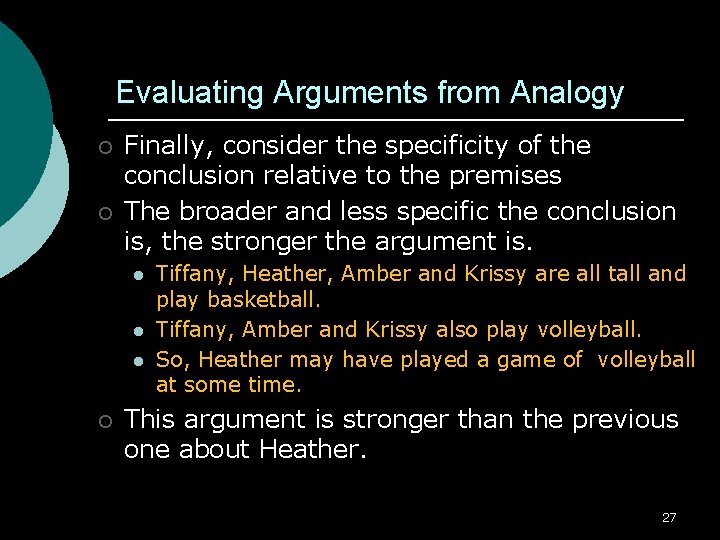

Evaluating Arguments from Analogy ¡ ¡ Finally, consider the specificity of the conclusion relative to the premises The broader and less specific the conclusion is, the stronger the argument is. l l l ¡ Tiffany, Heather, Amber and Krissy are all tall and play basketball. Tiffany, Amber and Krissy also play volleyball. So, Heather may have played a game of volleyball at some time. This argument is stronger than the previous one about Heather. 27

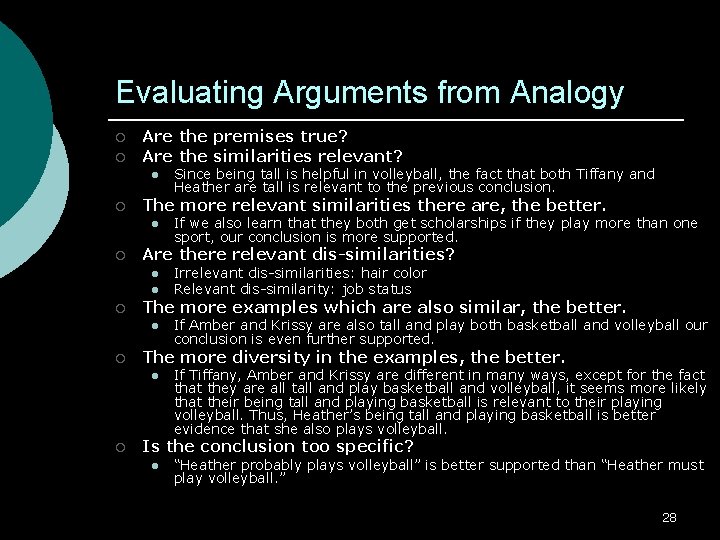

Evaluating Arguments from Analogy ¡ ¡ Are the premises true? Are the similarities relevant? l ¡ The more relevant similarities there are, the better. l ¡ l If Amber and Krissy are also tall and play both basketball and volleyball our conclusion is even further supported. The more diversity in the examples, the better. l ¡ Irrelevant dis-similarities: hair color Relevant dis-similarity: job status The more examples which are also similar, the better. l ¡ If we also learn that they both get scholarships if they play more than one sport, our conclusion is more supported. Are there relevant dis-similarities? l ¡ Since being tall is helpful in volleyball, the fact that both Tiffany and Heather are tall is relevant to the previous conclusion. If Tiffany, Amber and Krissy are different in many ways, except for the fact that they are all tall and play basketball and volleyball, it seems more likely that their being tall and playing basketball is relevant to their playing volleyball. Thus, Heather’s being tall and playing basketball is better evidence that she also plays volleyball. Is the conclusion too specific? l “Heather probably plays volleyball” is better supported than “Heather must play volleyball. ” 28

Arguing by Analogy Employ the same questions and evaluation as you construct your own arguments from analogy. ¡ Don’t be too specific. ¡ Use relevant similarities. ¡ Use many similarities. ¡ Use a diverse and large group. ¡ Use true premises. 29

Practice Page 308 -09, Exercise 11. 6 ¡ Page 309 -11, Exercise 11. 8 ¡ 30

I So far in this Chapter, we have looked at Inductive Reasoning and … Opinion polls ¡ Statistical arguments ¡ Reference class ¡ Arguments from analogy ¡ Today we will look at ¡ Causal arguments Lecture Notes © 2008 Mc. Graw Hill Higher Education 31

Induction and Causal Arguments ¡ Causes precede and are constantly conjoined with their effects. l l ¡ ¡ Cause and effect on a billiard table To argue that they are causally connected, we would cite the fact that the cue ball’s striking of the other balls always precedes and is constantly conjoined with the movement of the other balls. But (chapter 6) two things being constantly conjoined isn’t enough to conclude a causal connection. Additionally, one thing preceding another is not enough to conclude a causal connection. So how can we argue and conclude that two things are causally connected? 32

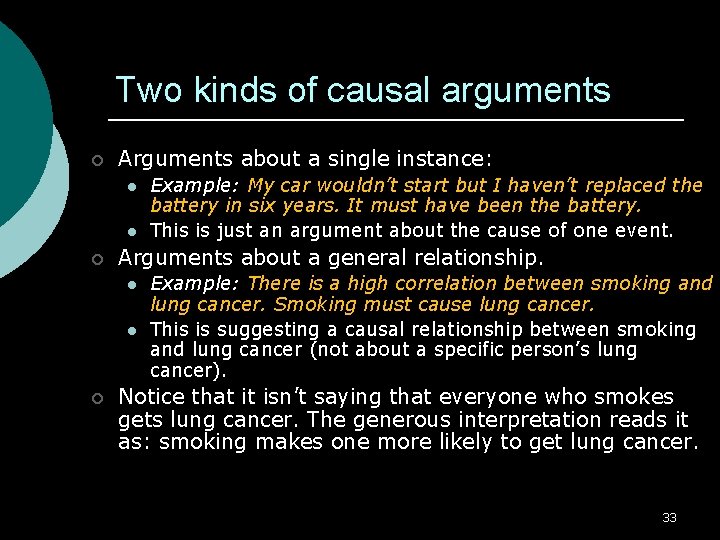

Two kinds of causal arguments ¡ Arguments about a single instance: l l ¡ Arguments about a general relationship. l l ¡ Example: My car wouldn’t start but I haven’t replaced the battery in six years. It must have been the battery. This is just an argument about the cause of one event. Example: There is a high correlation between smoking and lung cancer. Smoking must cause lung cancer. This is suggesting a causal relationship between smoking and lung cancer (not about a specific person’s lung cancer). Notice that it isn’t saying that everyone who smokes gets lung cancer. The generous interpretation reads it as: smoking makes one more likely to get lung cancer. 33

Two kinds of causal arguments These arguments are inductive. ¡ The premises provide evidence (strong evidence) for the conclusion. ¡ The conclusion does not follow with strict necessity from the premises. ¡ 34

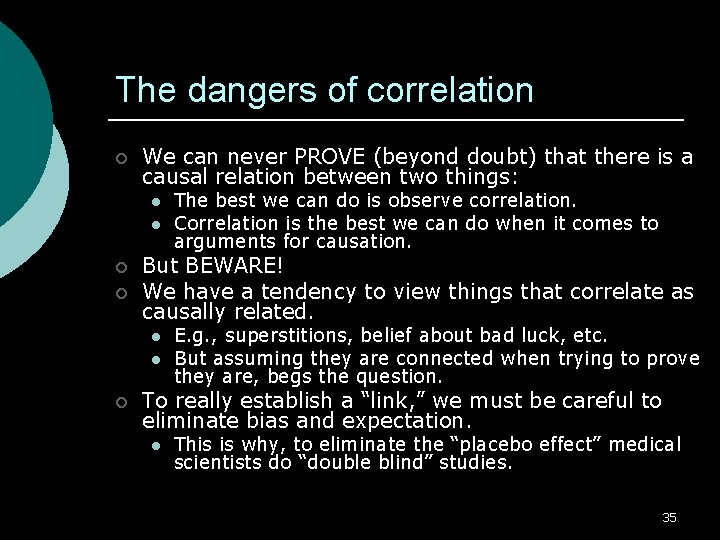

The dangers of correlation ¡ We can never PROVE (beyond doubt) that there is a causal relation between two things: l l ¡ ¡ But BEWARE! We have a tendency to view things that correlate as causally related. l l ¡ The best we can do is observe correlation. Correlation is the best we can do when it comes to arguments for causation. E. g. , superstitions, belief about bad luck, etc. But assuming they are connected when trying to prove they are, begs the question. To really establish a “link, ” we must be careful to eliminate bias and expectation. l This is why, to eliminate the “placebo effect” medical scientists do “double blind” studies. 35

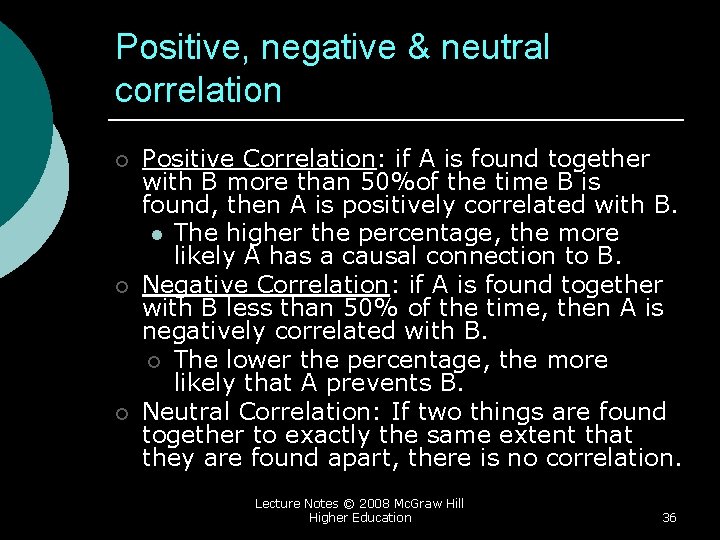

Positive, negative & neutral correlation ¡ ¡ ¡ Positive Correlation: if A is found together with B more than 50%of the time B is found, then A is positively correlated with B. l The higher the percentage, the more likely A has a causal connection to B. Negative Correlation: if A is found together with B less than 50% of the time, then A is negatively correlated with B. ¡ The lower the percentage, the more likely that A prevents B. Neutral Correlation: If two things are found together to exactly the same extent that they are found apart, there is no correlation. Lecture Notes © 2008 Mc. Graw Hill Higher Education 36

Correlation and Cause ¡ Even large amounts of correlation are not enough to establish a causal connection. l l ¡ When arguing from correlation, you need to make sure that there aren’t any other factors that might account for the correlation. l ¡ Example: Vitamin C study & proper rest (p. 329) But all in all, correlation is most often due to coincidence… l ¡ Example: big-feet and competence in math (p. 318 -19) News reporters have this problem all the time. Even if x is correlated with y, it could be due to the fact that they are both the causal result of some other thing z …so it is wise to always be suspicious. 37

Practice ¡ Pages 319 -20, Exercise 11. 10 38

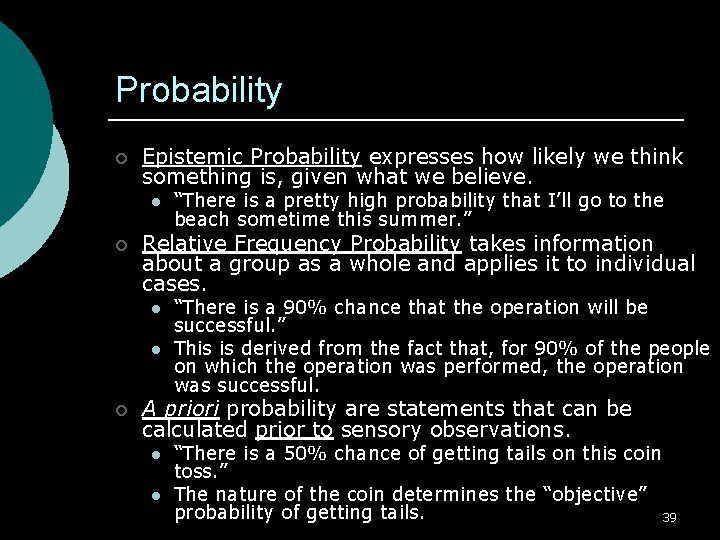

Probability ¡ Epistemic Probability expresses how likely we think something is, given what we believe. l ¡ Relative Frequency Probability takes information about a group as a whole and applies it to individual cases. l l ¡ “There is a pretty high probability that I’ll go to the beach sometime this summer. ” “There is a 90% chance that the operation will be successful. ” This is derived from the fact that, for 90% of the people on which the operation was performed, the operation was successful. A priori probability are statements that can be calculated prior to sensory observations. l l “There is a 50% chance of getting tails on this coin toss. ” The nature of the coin determines the “objective” probability of getting tails. 39

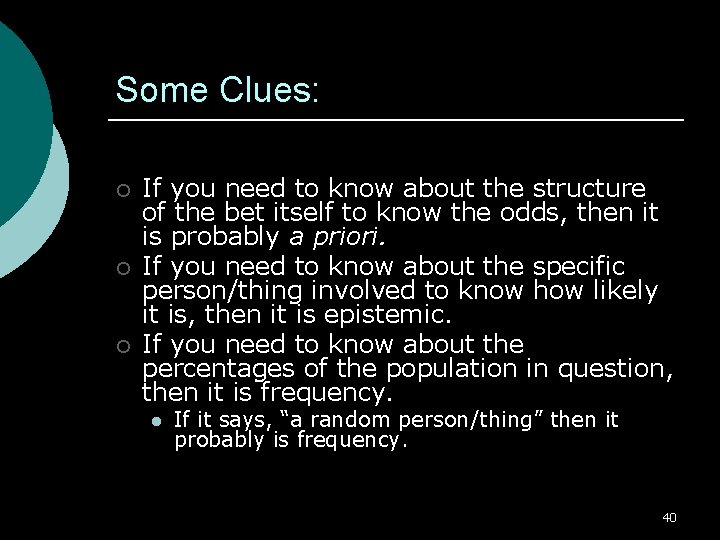

Some Clues: ¡ ¡ ¡ If you need to know about the structure of the bet itself to know the odds, then it is probably a priori. If you need to know about the specific person/thing involved to know how likely it is, then it is epistemic. If you need to know about the percentages of the population in question, then it is frequency. l If it says, “a random person/thing” then it probably is frequency. 40

Practice ¡ Pages 321 -22, Exercise 11. 11 41

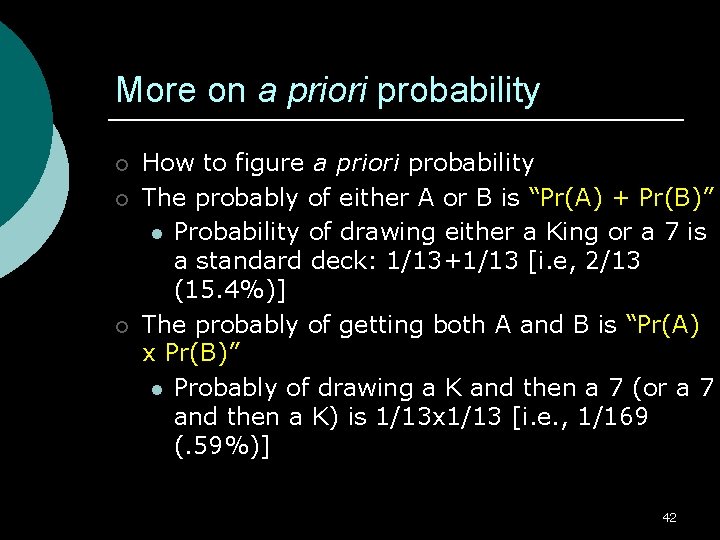

More on a priori probability ¡ ¡ ¡ How to figure a priori probability The probably of either A or B is “Pr(A) + Pr(B)” l Probability of drawing either a King or a 7 is a standard deck: 1/13+1/13 [i. e, 2/13 (15. 4%)] The probably of getting both A and B is “Pr(A) x Pr(B)” l Probably of drawing a K and then a 7 (or a 7 and then a K) is 1/13 x 1/13 [i. e. , 1/169 (. 59%)] 42

Gambler’s fallacy: ¡ Thinking that previous chance occurrences affect future ones. l The probably of a roulette wheel coming up black is always 47. 37%, even if it just came up black 28 times in a row. l Granted, if you haven’t started spinning the wheel yet, the probably of it hitting black 29 times in a row is low. l But, if you have already hit black 28 times, the probably of getting 29 in a row now is the same as the probably of hitting it once (because one more is all you need for 29): 47. 37%. 43

Bet values ¡ ¡ Expected Value: The payoff or loss you can expect from a bet. How to figure expected value: take the payoff and multiple it by your odds. l The expected value of a 1/100 chance at $100 is $1. ¡ ¡ If there are multiple payoff, you average them: l l ¡ 1/100 x$100=$1 1/3 rd chance at 0, 1/3 chance at $50, 1/3 chance at $100. Expected value $50. (0+50+100)/3=$50 Deal or no deal? : l The “banker” always offers less than expected value (the average of the amounts left), until the end when he wants them to take the deal. 44

Relative Value ¡ ¡ ¡ Of course, there are other reasons to take bets other than payoffs. Your own needs, preferences and resources can affect the “value” of a bet as well. The value a bet has, given such considerations, is the “relative value. ” l ¡ Example: The relative value of betting $100 for a long shot at a billion is high for a millionaire (he can afford it), but low for a homeless person (who wouldn’t want to risk money he can use to eat on a long shot at a billion). Diminishing marginal value: as quantity of bets increase, the relative value of the bets tends to decrease. l If you are really hungry, you are willing to buy a piece of pizza for $10 (if that is all that is available). It’s relative value is really high. But after you eat it, and your hunger subsides somewhat, its relative value drops and you are less willing to pay so much. Buy enough pizza, and you won’t be willing to pay much at all. Buy too much (and eat it) and you won’t take it for free. 45

Practice ¡ Page 326, Exercise 11. 12 46