Course title Economics of Innovation Prof Davide Infante

![References Abramovitz, M. [1986], Catching Up, Forging Ahead, and Falling Behind, in «Journal of References Abramovitz, M. [1986], Catching Up, Forging Ahead, and Falling Behind, in «Journal of](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/7563301ba4414338ddf65fcb3210c2cc/image-38.jpg)

- Slides: 38

Course title Economics of Innovation Prof. Davide Infante Department of Economics and Statistics University of Calabria - Italy d. infante@unical. it Notes on lecture 3: Technical progress and economic growth INF

Introduction_1 • Why do economists study technical change and innovation? • 1. 1. Macroeconomics - to understand economic growth • 2. 2. Microeconomics - to learn how the process works and what motivates the actors • 3. 3. Strategy (business economics) - to help choose strategies • 4. 4. Policy for choosing and designing government policy INF

Introduction_2 In this lecture we focus on economic growth Improvements in our standard of living come from productivity growth, getting more output per unit of input or more output per unit of input How? - Investment leading to more capital per worker - Scale or size effects (e. g. , from commercial expansion), due to fixed costs, specialization expansion) - Increases in the stock of knowledge via technical and institutional change How do we model and measure the magnitude of these effects? We start from some growth indicators INF

On convergence 1 • • • We start from an analysis of cross-country data from: - table 1 - Size of the economy in World Development Report (2005) of World Bank - Annex table 1 Economic Outlook (December 2005), OECD. • On the base of this analysis we deduct the following facts: INF

On convergence 2 • • Fact # 1 There is a strong variation in the income per capita between economies. The poorer countries have income per capita that are less then 5% of income per capita in the richest countries. Fact # 2 The rates of growth change substantially between countries. Fact # 3 The rates of growth are not necessarily constant over time. Fact # 4 The relative position of a country in the world distribution of income per capita is non immutable. Countries can change their position from poor to rich and viceversa. INF

On convergence 3 • • Lucas practical rule (1988): a country that grows at a g rate per year will double it income per capita every 0. 7/g years. We can explain this rule as the following: Let’s assume y(t) as the income per capita at time t and let’s take y 0 as some initial value of the per-capita income. Hence: The time span to double a per-capita income is given by y(t)=2 y 0. Henceforth: INF

On Convergence 4 • The rule derives from the fact that the log of 2 is =. 7 • Hence if a country grows at a rate of 1. 4% per year than it will double its pro-capita income in about 50 years, while a country that grows at a rate of 2. 9% will double its pro-capita income in about 24 years. INF

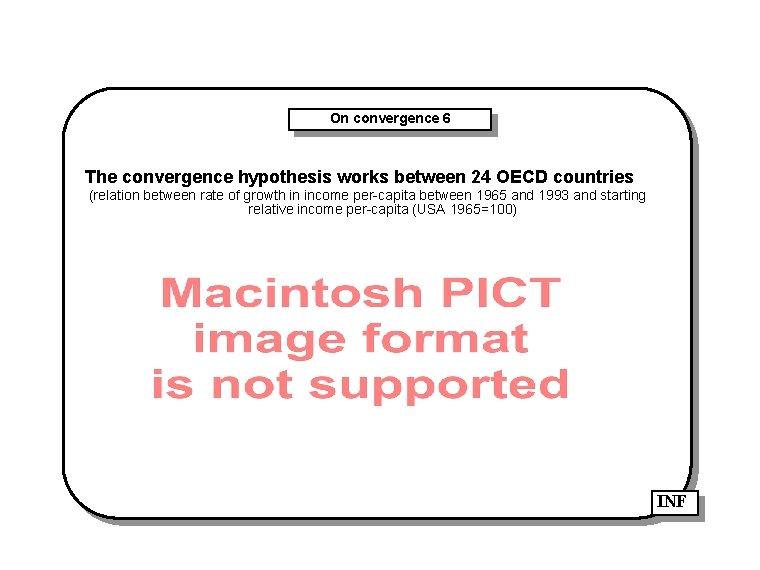

On convergence 5 In the current literature the term "catching up" has been often identified with the “controversy on convergence" The hypothesis convergence states the existence of a convergence between countries income per capita. This means that there is a negative relationship between productivity and relative income per-capita. Mechanism: being backward in the productivity level allows to a strong potential for productivity. INF

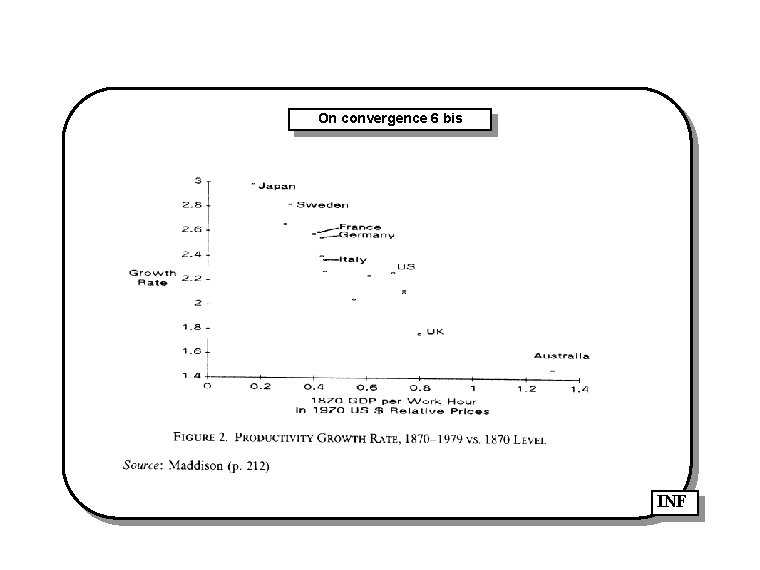

On convergence 6 The convergence hypothesis works between 24 OECD countries (relation between rate of growth in income per-capita between 1965 and 1993 and starting relative income per-capita (USA 1965=100) INF

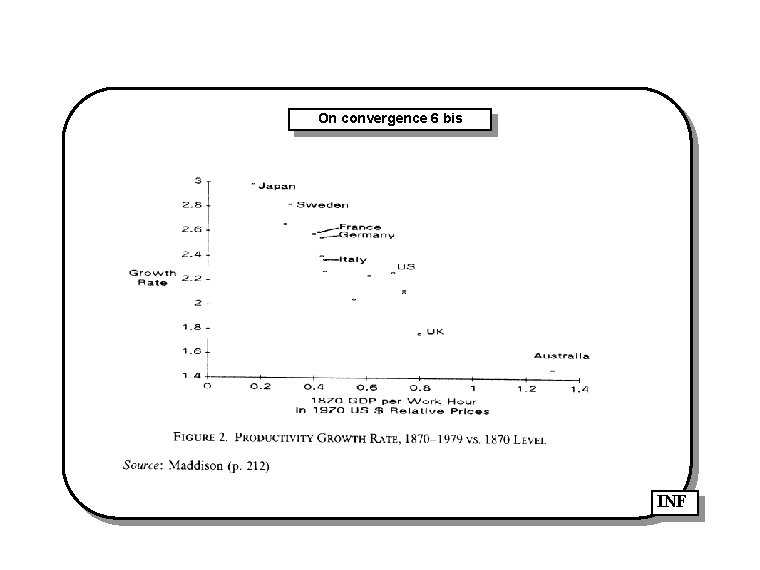

On convergence 6 bis INF

On convergence 7 INF

On convergence 7 bis The convergence hypothesis does not work at global level (relation between rate of growth in income per-capita between 1965 and 1993 and starting relative income per-capita (USA 1965=100) INF

On convergence 8 In this version the catch-up hypothesis seems a sort of long-run growth insurance. To avoid this criticism Abramovitz qualifies his definition introducing from one side some conditions: 1) rapid productivity growth 2) dynamic economies of scale 3) modernization of technologies 4) structural change On the other side he defines the necessary characteristics for catching-up: 1) social capability (competences, education, institutions, firms) 2) adaptability (capacity of a country to exploit the power of technologies) INF

On convergence 9 It comes back the concept relative backwardness. Abramovitz does not explain because and why new technologies transfer from leader to follower countries. Baumol explains it with the nature of public good of technical progress and investment. If a leader countries introduces innovations this, in the long run, will turn out positively on lagging countries. Through the following mechanisms: 1) The Schumpeterian competition 2) The theorem of factor prices equalisation INF

On convergence 10 The catching-up idea of Abramovitz and Baumol can be synthesised as the following: 1) the technological progress is exogenous 2) the technological progress is a non-excludible good 3) the technological progress depends on the learning capacity of the catching-up country 4) existence of decreasing returns of capital. INF

On convergence 11 Limits of convergence hypothesis Three group of countries: 1) OECD countries convergent club. 2) Countries that present some similar characteristics to OECD Countries and are able to converge to the club. 3) Countries that present very low rates of growth. They do not have external inflow of technologies and their learning capacity is so low that it is not so profitable to introduce technical progress incorporated in machineries. INF

On convergence 12 The growth model of convergence hypothesis is based on the following production function equation: A = a catch-all parameter excluded by the assumption of constant returns to scale (technical progress, returns to scale, learning by doing, managerial efficiency). INF

On convergence 13 The hypothesis underlining this growth model are: 1) technology is exogenous (is independent from capital and labour) 2) constant returns to scale [hence factors decreasing return ( <1)] The existence of factors decreasing return, full information and factor mobility are the basis for catching up-convergence theory. The investment in capital is much more productive where is scarce. This makes possible the convergence hypothesis. INF

On convergence and NGT 14 The new growth theory: the persistent divergence between advanced and backward countries leaves the neoclassical model of growth without credibility. Romer (1990) states the existence of five principal factors for the growth of a economic system: 1. existence of many firms on the market 2. absence of rivalry in information 3. possibility to replicate activities (firms operate at the Minimum Efficient Scale) 4. the rate of new discoveries is linked to what firms do 5. firms can have market power and gain monopoly profits. INF

On convergence and NGT 15 The neoclassical growth model can satisfy conditions 1 -3 but not 4 and 5 that presume the endogeneity of technical progress and the appropriability of innovation benefits (innovation is an excludable good) The facts 4 e 5 are those that permit either the catching-up (convergence) or the lagging-behind (divergence). For Romer the divergence between neoclassical growth theory and the empirical evidence of low rates of growth of less developed countries is due to: a) existence of endogenous technical progress, that derives from knowledge spillovers that add on normal returns of capital and labour. b) to the uprising of a monopoly power (patents, product differentiation). INF

On convergence and NGT 16 It is just the assumption of increasing returns to scale that makes possible the continuous divergence in per capita GDP level between countries. To construct its first growth model Romer (1986) recurs to the idea of Arrow´s learning by doing: the growth of productivity depends on the accumulation of capital in the industry (economy). This is because new knowledge is discovered as investment and output increase. INF

On convergence and NGT 17 Romer (1986): where y = output per worker k = capital per worker Romer demonstrates that the decreasing return of capital of a single firm 0<a<1 is counterbalanced by external spillovers. INF

On convergence and NGT 18 For Lucas (1988) the neo-classical model is not able to explain, during time, the differential of growth between countries. The neoclassical model is able to explain only the convergence between some rich countries. For Lucas the growth of income per capita can be explained through the accumulation of human capital. INF

On convergence and NGT 19 The Lucas (1988) model has the same cultural background of Romer´s model. Both consider the idea of spillovers through learning by doing. Lucas assumes that the growth of income per capita is determined only by the accumulation of human capital. con dove y = outpu per worker h = human capital In (1993) Lucas introduces the stock of human capital at world level in j country INF

On convergence and NGT 20 The Romer and Lucas´s models solve point 4 but not point 5, because technology is treated as public good. On the contrary one of the primary sources of the productivity differentials is exactly the property of excludability that very often is presented by knowledge. Appropriability Monopoly power Innovation The neo-schumpeterian approach to the growth theory: growth is determined by endogenous innovations. The development of new intermediate goods leads to a higher specialisation in the use of resources and to a higher productivity. INF

On convergence and NGT 21 Romer (1990): Three economic sectors: final goods, intermediate goods, research Y = final output Hy = human capital L = labour Z = aggregated measure of intermediate goods INF

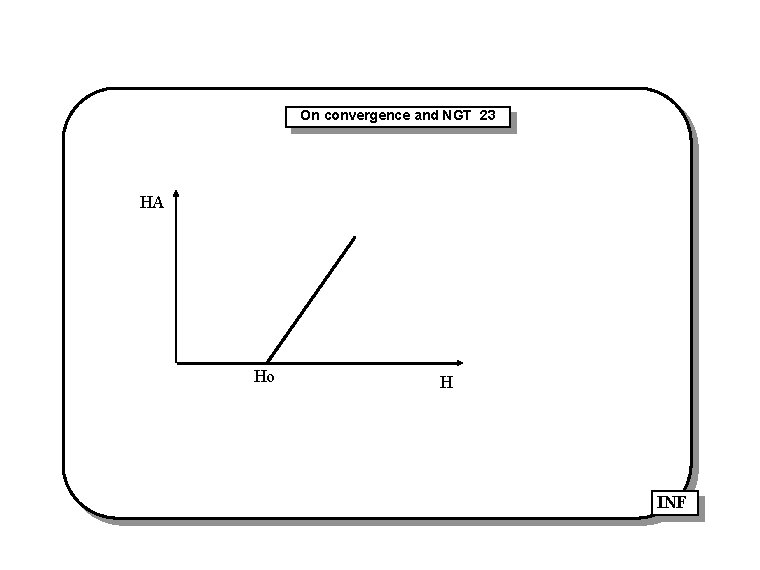

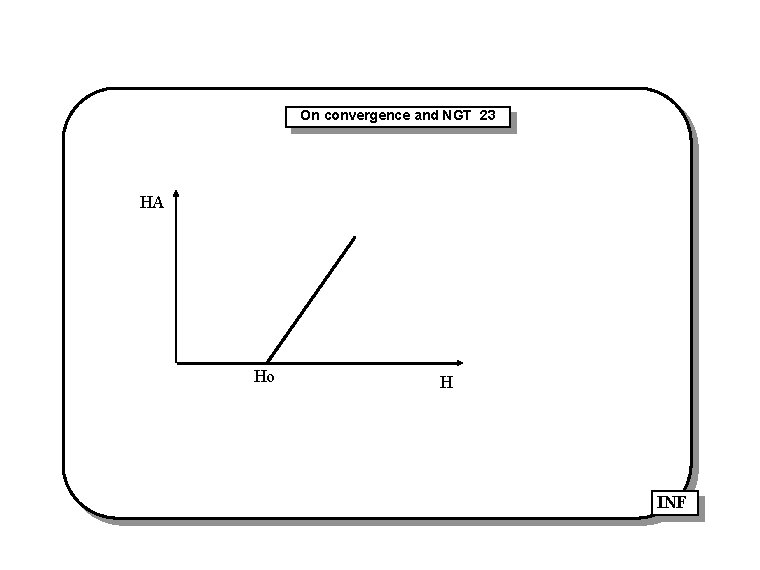

On convergence and NGT 22 Romer uses a model of product differentiation (Dixon e Stiglitz), assuming a continuum of intermediate goods in the interval (0, A), hence equation (1) becomes: The sector presents increasing returns because of incomplete property rights (part of the generated knowledge can be utilised by other firms). Hence an increase in the stock of human capital HA increases the rate of growth. INF

On convergence and NGT 23 HA Ho H INF

On convergence and NGT 24 The specification of the technology that holds in the R&D sector is of the following form: where H denotes the stock of human capital used in reaserch and A a measure of the general accumulated knowledge, freely available for all firm in the research sector. Romer assumes that if the research firm j invest an amount of human capital Hj and has access to a portion Aj of the total amount of knowledge already existing in the research sector, the rate of production of new designs by the research firm j will be where delta stands for the research productivity parameter. INF

On convergence and NGT 25 In the Romer model each intermediate good is produced by a “local monopolist”. This hypothesis is coherent with the existence of growing or complement markets, but it is not with the Schumpeterian creative destruction. This aspect is faced in 1992 Aghion and Howitt´s model (see Infante 1995). INF

On convergence and NGT 26 In Aghion and Howitt (1992) model the final output depends on the input of an intermediate good, x. It does not take into account capital accumulation. In their interpretation, the model is changed according to: Y = AF(x) where Y is the final output, and x is the intermediate good. The labour stock is used in two activities: a) The production of intermediate goods (i. e. , one unit of labour produces a unit of intermediate good x); b) The creation of innovations in the research sector. Innovation is the invention of a new intermediate product x, that replaces the existing ones and raises the technology parameter, A. INF

On convergence and NGT 27 When n units of labour are employed in the research sector, innovations occur randomly according to the Poisson arrival date, , where > 0 is given and represents the productivity research sector parameter. When the innovation is introduced, it takes over the entire market for the production of the intermediate good. Each successive innovation raises productivity forever, because it allows the productivity parameter A to increase by the same factor > 1 and there is no lag in the introduction of technology, so that: where t (=0, 1, . . ) represents subsequent innovation. INF

On convergence and NGT 28 Aghion and Howitt model differs from Romer's model because it embodies the Schumpeterian idea of "creative destruction". In their model, the discounted expected value for the innovative firm is: where t+1 is the flux of monopoly profits generated by the t+1 st innovation, r the interest rate, n the amount of labour applied to R&D, and the Poisson arrival date of innovation after the t+1 th innovation. INF

On convergence and NGT 29 The firm is induced to innovate because it can capture the entire market, so gaining monopoly profits. Some negative effects: a) a firm that introduces innovation has no incentive for further research. The "business-stealing effect" works either against rivals or the innovator's expected profits that would be b) assuming free entry in the research sector, only outside firms will do new research. In order to innovate, they need to increase the number of research people, thus: (i) increasing the wage rate (ii) raising the rate of creative destruction, hence, decreasing the expected profits of innovation, (iii), increasing n will accelerate the expected date of discovery thus decreasing the time interval for monopoly rents. INF

On convergence and NGT 30 The Aghion and Howitt's model is a strong advance on the socalled neo-Schumpeterian approach of the New Growth Theory. Some of the essential features ("creative destruction" and persistence of monopoly power in the innovative sectors) of Schumpeter's approach in this model are endogenised. Some reservations: - “memoryless” mechanism: the assumption that innovation occurs according to a Poisson probability distribution is fairly strong. INF

On convergence and NGT 31 - In addition, the memoryless mechanism assumption leads to a situation in which the monopolist has no incentive to further research whilst outside firms have because they have the same probability of discovering a new intermediate good and becoming a monopolist. - The absence of experience (Poisson assumption of independence), weaken the Schumpeterian idea of innovation as a source of monopoly rents. - Another problem is that regarding , the factor affecting the productivity parameter A, which is assumed to be constant; i. e. the rate of increase in the parameter A is proportional to the amount reached in the current time (technology), this means that the following relationship exists between A and x INF

On convergence and NGT 32 , therefore, is a proportional constant that is completely independent of the variable x. It does not depend on the type (and numbers) of innovation (radical, incremental, cross-sector) discovered. - If varies its impact on A, it would increase (decrease) the flow of monopoly profits generated by the t+1 st innovation, matching the decrease in its expected value, generated by an increase of n (the labour stock dedicated to research activities). INF

![References Abramovitz M 1986 Catching Up Forging Ahead and Falling Behind in Journal of References Abramovitz, M. [1986], Catching Up, Forging Ahead, and Falling Behind, in «Journal of](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/7563301ba4414338ddf65fcb3210c2cc/image-38.jpg)

References Abramovitz, M. [1986], Catching Up, Forging Ahead, and Falling Behind, in «Journal of Economic History» , June 1986, 46, pp. 383 -406. Aghion, P. , and Howitt, P. [1992], "A Model of Growth Through Creative Destruction", Econometrica, March 1992, 60: 2, 323 -51 Baumol, W. J. [1986], Productivity Growth, Convergence and Welfare: What Long-Run Data Show, The American Economic Review, 76 (5), pp. 1072 -1085. Dixit, A. K e Stiglitz, J. E. [1977], Monopolistic Competition and Optimum Product Diversity, «American Economic Review» , 67, 3, pp. 297 -43. Gerschenkron, A. [1962], Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge. Infante, D. [1995], Catching-up, Growth and Innovation Processes, Research Report No. 2/1995, Centre for Southern European and Mediterranean Studies, Roskilde University, Roskilde. Infante, D. [2005], Crescita e catching up nell’Unione Europea allargata, in Crescita e prospettive nell’Unione Europea allargata (a cura di D. Infante), Centro di Documentazione Europea, Università della Calabria, pp. 29 -32 Jones, C. I. [1998], Introduction to Economic Growth, W. W. Norton and Company, New York. Lucas, E. R. [1988], On the Mechanics of Economic Development, in «Journal of Monetary Economics» , 21, pp. 3 -42. Lucas, E. R. [1993], Making a Miracle, in «Econometrica» , 61, 2, pp. 251 -72 Romer, P. M. [1986], Increasing Returns and Long-Run Growth, in «Journal of Political Economy» , 94, pp. 1002 -37. Romer, P. M. [1990], Endogenous Technological Change, in «Journal of Political Economy» , 98, pp. S 71 -S 102. INF

Course title and course number

Course title and course number Oliver infante

Oliver infante Casa del infante el escorial

Casa del infante el escorial Michele infante

Michele infante Mision y vision de loreal

Mision y vision de loreal Amélia de orleães

Amélia de orleães Besigheidsplan

Besigheidsplan Radical vs disruptive innovation

Radical vs disruptive innovation Maastricht university school of business and economics

Maastricht university school of business and economics Mathematical economics vs non mathematical economics

Mathematical economics vs non mathematical economics Title fly and title page

Title fly and title page Title title

Title title Course title examples

Course title examples Course title

Course title English bond t junction elevation

English bond t junction elevation Course interne course externe

Course interne course externe Davide maccabruni

Davide maccabruni Venzano davide oculista genova

Venzano davide oculista genova Osanna al figlio di davide testo

Osanna al figlio di davide testo Davide morotti

Davide morotti Davide soloperto

Davide soloperto Davide carlino psichiatra

Davide carlino psichiatra Davide schinetti

Davide schinetti Davide ravasi

Davide ravasi Davide piva

Davide piva Davide falchieri

Davide falchieri Emilio promette al figlio davide

Emilio promette al figlio davide Davide mongelli

Davide mongelli Davide lauro

Davide lauro Davide salomoni

Davide salomoni Davide ruggieri unibo

Davide ruggieri unibo Victoria mazza

Victoria mazza Davide damosso

Davide damosso Salvatore davide porzio

Salvatore davide porzio Univaq mail

Univaq mail Davide baroni

Davide baroni Esempio di girata su cambiale

Esempio di girata su cambiale Davide fiammenghi

Davide fiammenghi Davide ruggieri

Davide ruggieri