Course Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences

- Slides: 48

Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ISU – BA course: Concepts of Applied Ecology, Forestry and Natural Resources 1. Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Introduction Forest and Natural Resources, Ecology – professional and career opportunities in management, education and science I. Concepts of Natural Resources and their Use ● Climate and Weather ● Forests ● Soils ● Rangelands ● Water, Watersheds & Wetlands ● Agricultural Lands II. Man and Nature, an introduction to sustainable Land Biodiversity Management ● Forestry ● Nature Protection Management ● Agriculture ● Water Management ● Rangeland Management ● Urban Nature Management ● Wildlife Management III. Introduction to General and Ecosystems Ecology ● General Ecology ● Terrestrial Biomes of the Earth 1. ����������� – ����������� ������� , �������������� I. ���������� ���������� ● ������� ● ����� , ������ ������� ������ II. �������� , �������� ����������� ●������� ● ���������� ● �������� ●������� ● ���������� III. �������������� ● ��������� Seminars, Intro and Mid-term Exams, Group Work, Presentation & Evaluation, Final Exam Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management ������ , ���������� , ����������� ����� Joachim PUHE ����� , �������� , ���������

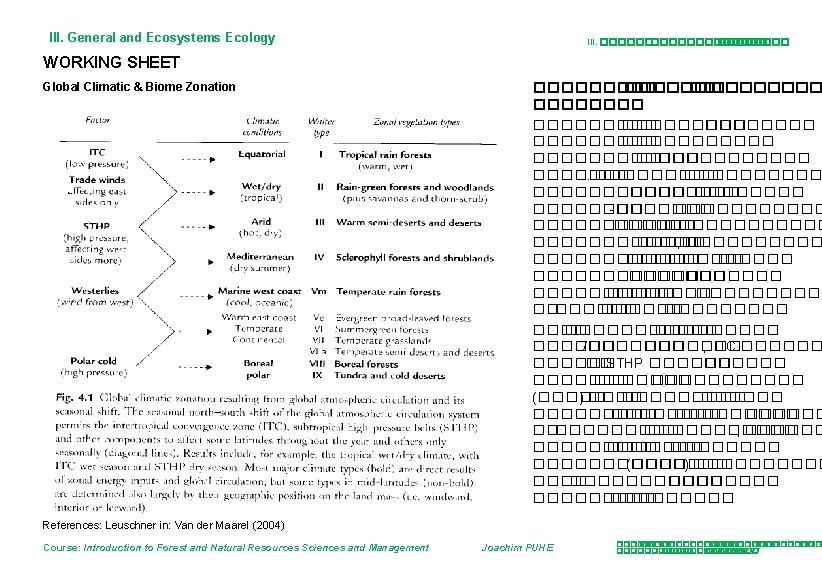

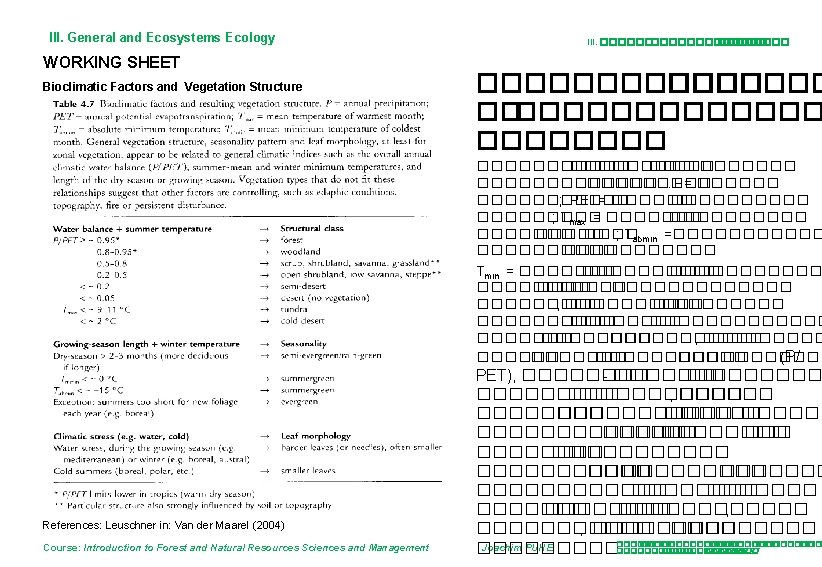

5. General and Ecosystems Ecology III. General and 5. and Ecosystems Ecology III. ������ �� ������� Cycles Ecosystems Ecology • Solar Irradiation • Ocean & Atmospheric Circulation • Climates and Climate Classification • Vegetation Classification • Primary Production • Working Sheets: Energy Flow, NPP, Carbon Uptake and Storage, Climates and Biome Classification, Terrestrial Biome Types, Bioclimatic Factors and Vegetation Structure, Vegetation Types and Plant Forms • Limits of Tree Growth: Tree and Timber Line • Ecological Range and Competitiveness of Tree Species • Biodiversity • ������������� • ���������� ������ • ��������� • ��������� : ������ , NPP, ���������� , ���������� ������ , ��������������� , ��������� • ������ : �� ������ • ������ ��������� • ��������� Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

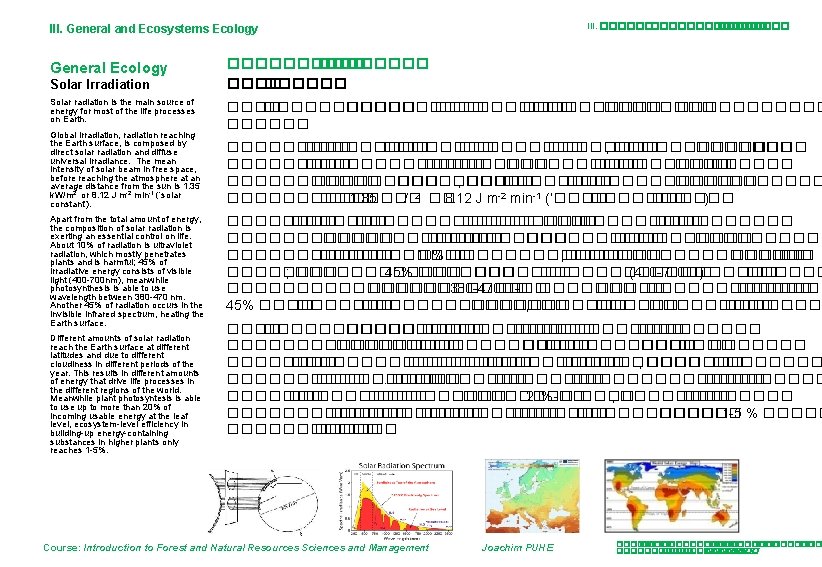

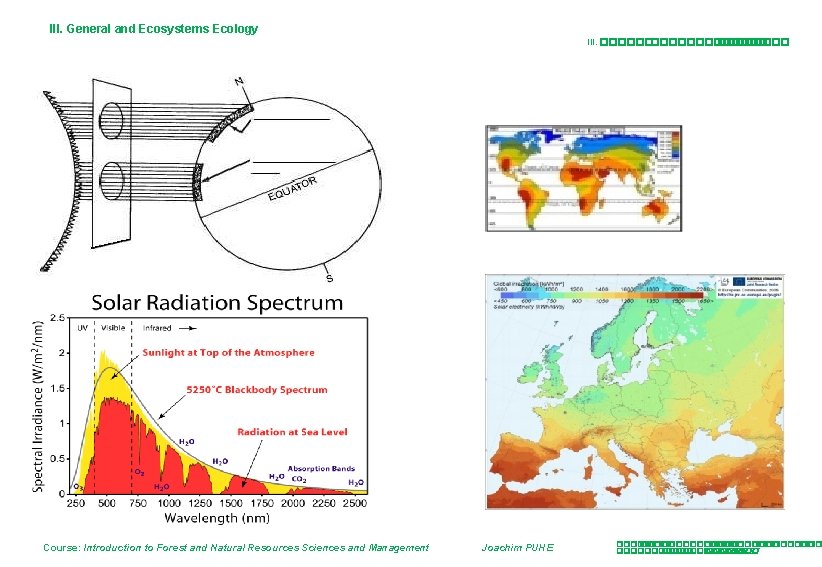

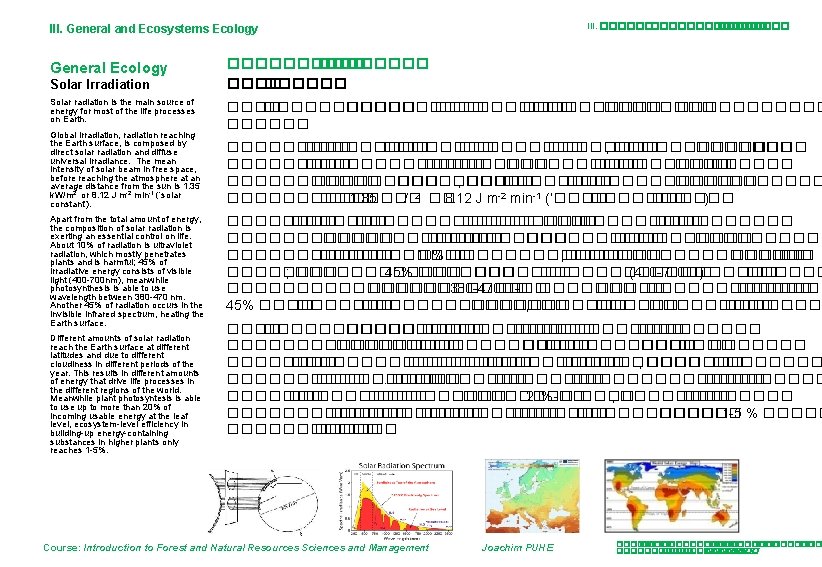

III. ����������� III. General and Ecosystems Ecology General Ecology Solar Irradiation Solar radiation is the main source of energy for most of the life processes on Earth. Global irradiation, radiation reaching the Earth surface, is composed by direct solar radiation and diffuse universal irradiance. The mean intensity of solar beam in free space, before reaching the atmosphere at an average distance from the sun is 1. 35 k. W/m 2 or 8. 12 J m-2 min-1 (‘solar constant’). Apart from the total amount of energy, the composition of solar radiation is exerting an essential control on life. About 10% of radiation is ultraviolet radiation, which mostly penetrates plants and is harmful; 45% of irradiative energy consists of visible light (400 -700 nm), meanwhile photosynthesis is able to use wavelength between 380 -470 nm. Another 45% of radiation occurs in the invisible infrared spectrum, heating the Earth surface. Different amounts of solar radiation reach the Earth surface at different latitudes and due to different cloudiness in different periods of the year. This results in different amounts of energy that drive life processes in the different regions of the world. Meanwhile plant photosyntesis is able to use up to more than 20% of incoming usable energy at the leaf level, ecosystem-level efficiency in building-up energy-containing substances in higher plants only reaches 1 -5%. ����� �������������� �������� ��������� ���� , ������� ����������� ���������� ���� , �������� ������� 2 -2 -1 ������ 1. 35 ��� /� �� 8. 12 J m min (‘������ ). ������������� ������������� ���������� ������ 10% ������� , ������������� �� ���� ; ������ 45% ������� (400 -700�� ) �������� ������ 380 -470�� -�� ������� 45% ������� ������� , ������� ����������� ��������� �������������� ���������� , ��������� ������ ������������� 20%-�� ���� , �������� ����������� ������ 1 -5 % �����������. Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology III. ����������� Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

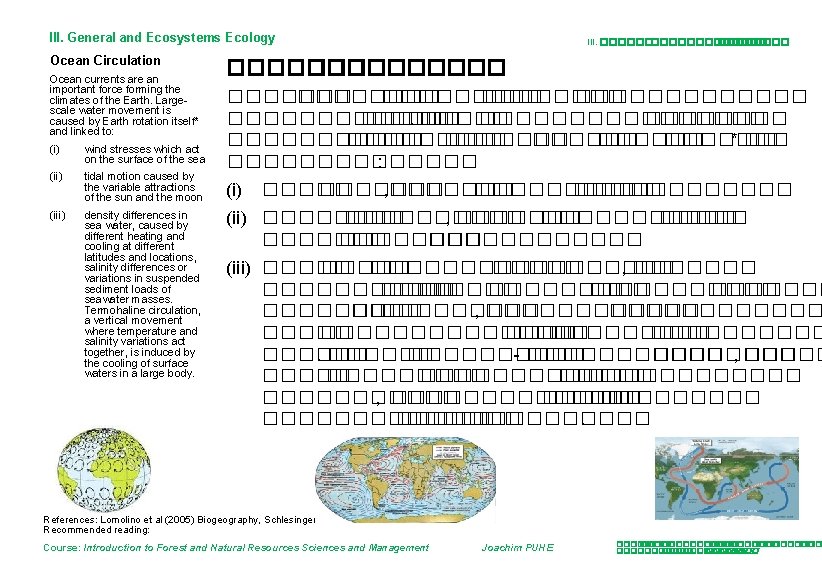

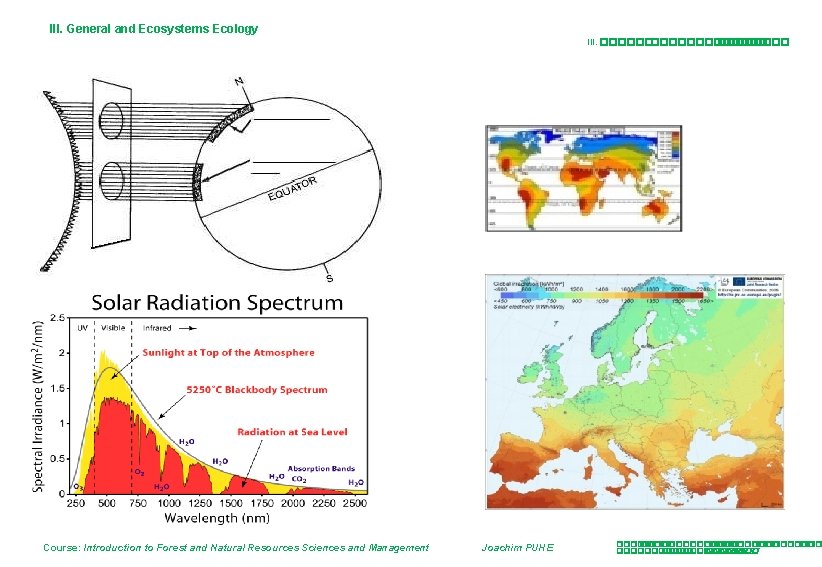

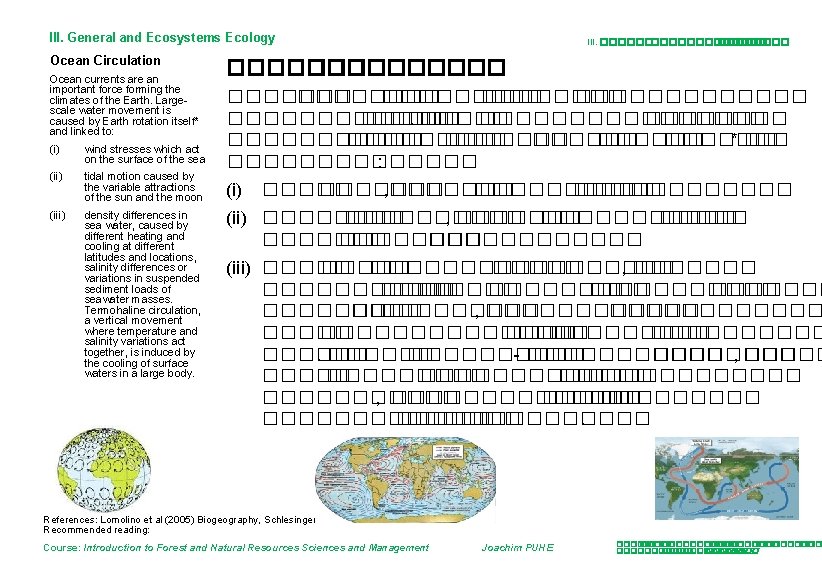

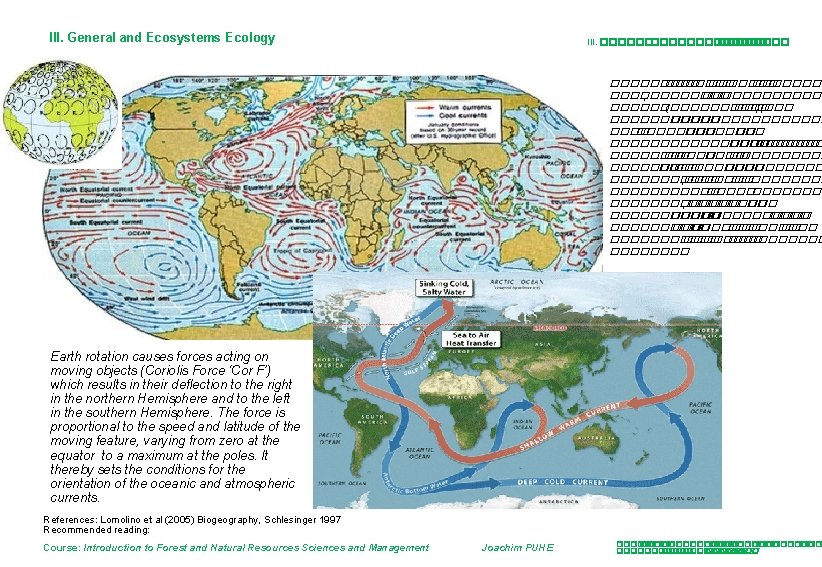

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology Ocean Circulation Ocean currents are an important force forming the climates of the Earth. Largescale water movement is caused by Earth rotation itself* and linked to: (i) wind stresses which act on the surface of the sea (ii) tidal motion caused by the variable attractions of the sun and the moon (iii) density differences in sea water, caused by different heating and cooling at different latitudes and locations, salinity differences or variations in suspended sediment loads of seawater masses. Termohaline circulation, a vertical movement where temperature and salinity variations act together, is induced by the cooling of surface waters in a large body. III. ����������� �������� ������������������� ������� * �� ������� : (i) ������� , ��������� (ii) ���������� , ����������� ������ (iii) ������� ������� , ����������� ��������� ������ , ������������ ���������������� - ������ , ���������������� , ������� ����������. References: Lomolino et al (2005) Biogeography, Schlesinger 1997 Recommended reading: Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

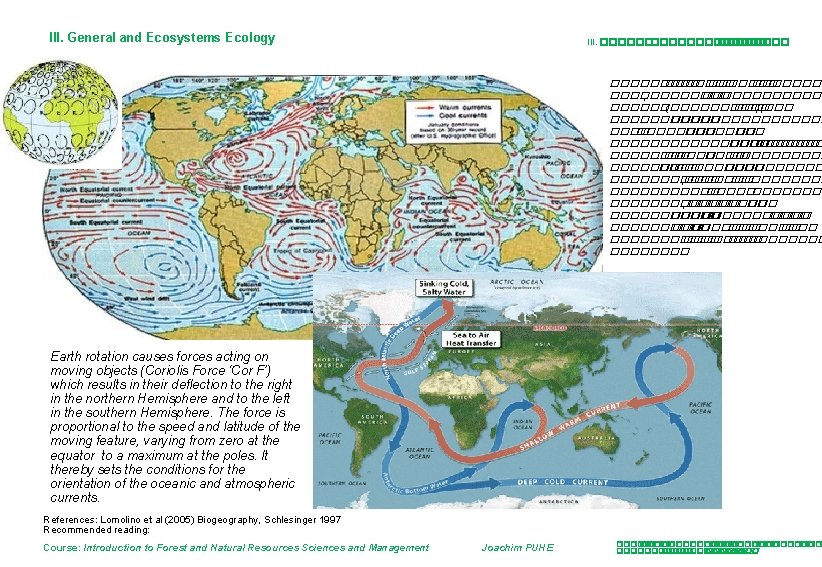

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology III. ����������� ������� , ���������� (����� ), �������� �������� �� ����������� ���� �� ���������� ������ , ���������� ����� ������� , ����� �� ������������� �� ����������. Earth rotation causes forces acting on moving objects (Coriolis Force ‘Cor F’) which results in their deflection to the right in the northern Hemisphere and to the left in the southern Hemisphere. The force is proportional to the speed and latitude of the moving feature, varying from zero at the equator to a maximum at the poles. It thereby sets the conditions for the orientation of the oceanic and atmospheric currents. References: Lomolino et al (2005) Biogeography, Schlesinger 1997 Recommended reading: Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

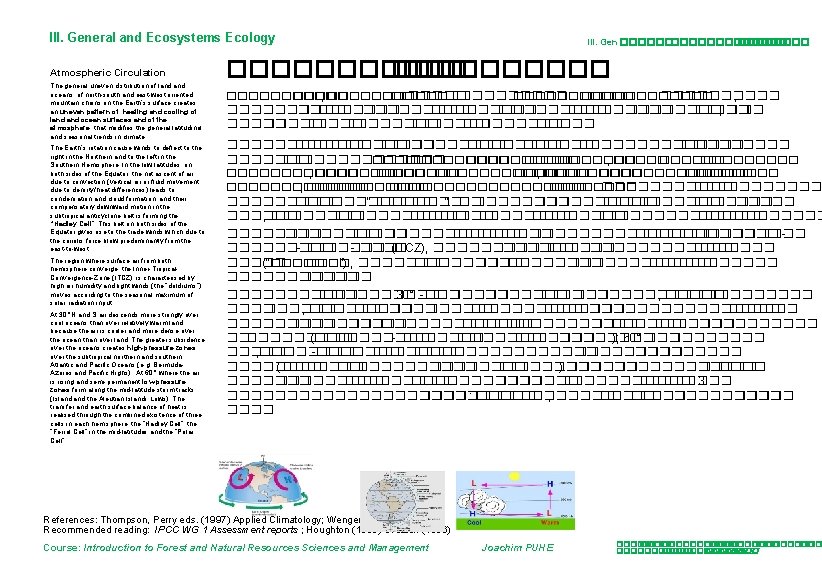

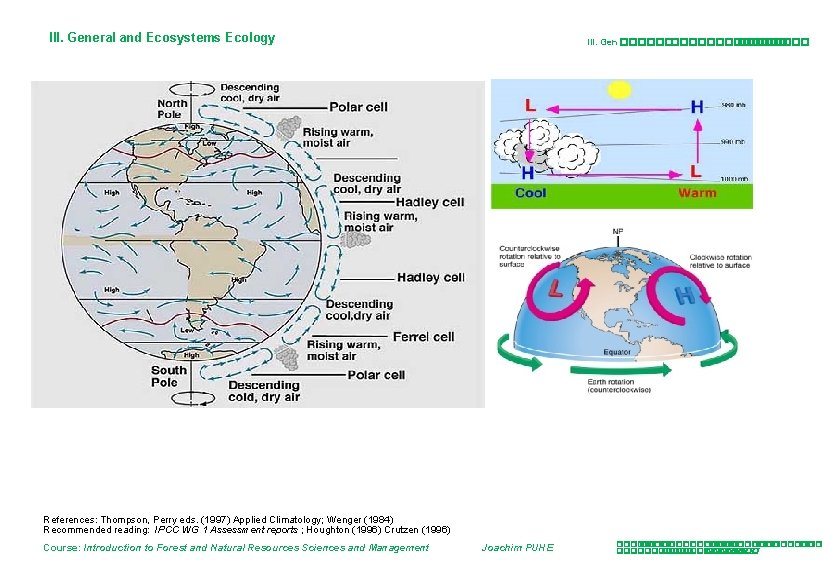

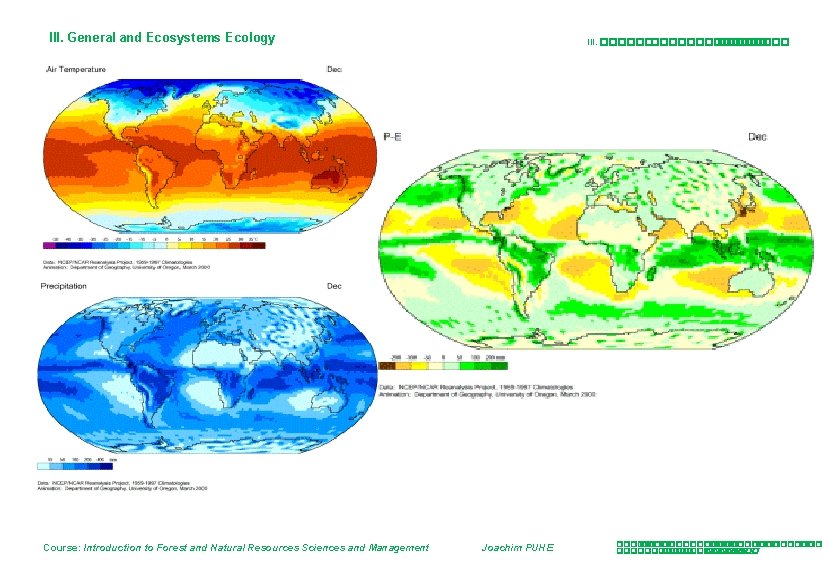

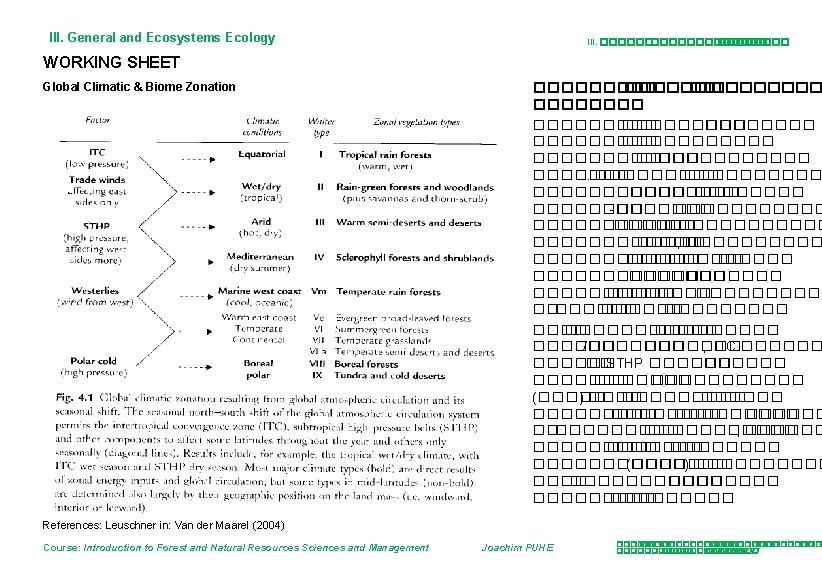

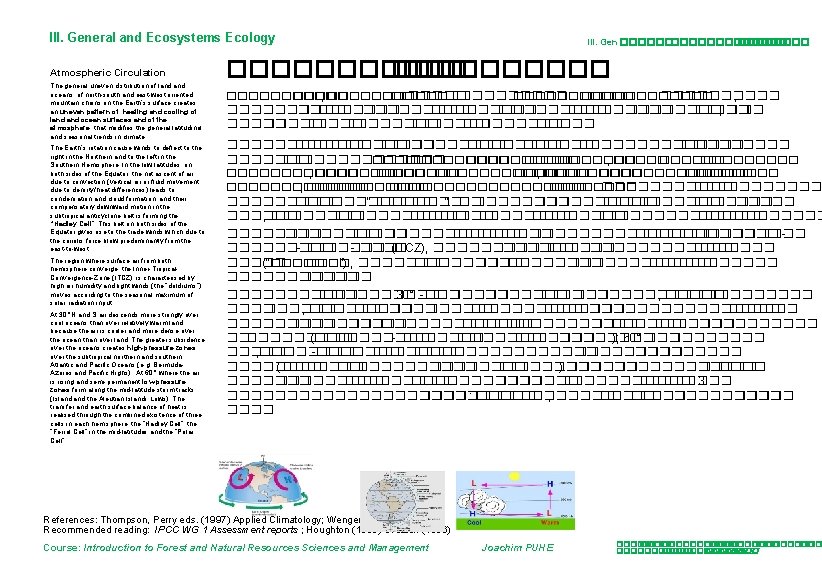

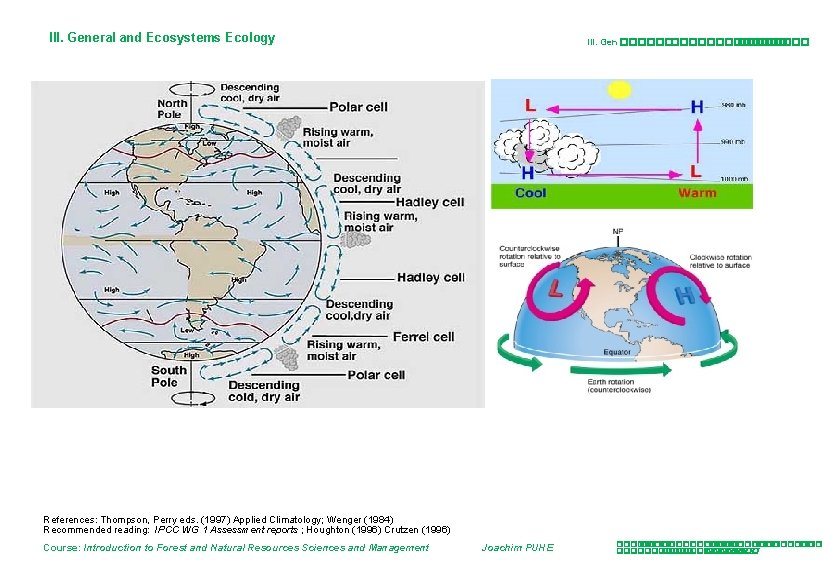

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology Atmospheric Circulation The general uneven distribution of land oceans, of north-south and east-west oriented mountain chains on the Earth’s surface creates an uneven pattern of heating and cooling of land ocean surfaces and of the atmosphere, that modifies the general latitudinal and seasonal trends in climate. The Earth’s rotation cause winds to deflect to the right in the Northern and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere. In the low latitudes, on both sides of the Equator, the net ascent of air due to convection (vertical air or fluid movement due to density/heat differences) leads to condensation and cloud formation, and their compensatory downward motion in the subtropical anticyclone belt is forming the “Hadley Cell”. This belt on both sides of the Equator gives rise to the trade winds which due to the coriolis force blow predominantly from the east-to-west. The region where surface air from both hemisphere converge, the Inner-Tropical. Convergence-Zone (ITCZ), is characterised by high air humidity and light winds (the “doldrums”) moves according to the seasonal maximum of solar radiation input. At 30° N and S air descends more strongly over cool oceans than over relatively warm land, because the air is cooler and more dense over the ocean than over land. The greater subsidence over the oceans creates high-pressure zones over the subtropical northern and southern Atlantic and Pacific Oceans (e. g. Bermuda. Azores and Pacific Highs); . At 60°, where the air is rising and semi-permanent low-pressure zones form along the mid-latitude storm tracks (Island the Aleutian Islands Lows). The transfer and earth surface balance of heat is realised through the combined existence of three cells in each hemisphere, the “Hadley Cell”, the “Ferrel Cell” in the mid-latitudes and the “Polar Cell”. III. Gen ����������� ���������� , ������������������ , ����������������� ����� , �� �� �������� ��������� ������ ������� �������������� ������� , ����� �� ��������� , �������������� , �������������� , �� ��������������� ������������ “����� ”. �� ��������� ������ , ���������� ������� ��������� �������� ���� ����� -���� - ���� (ITCZ), ������ ������ ����� (“����� ”) , �������� ����������� ����������� 30° -��� ������� ��� ����� , ��������� , ������ ��������� ������������� �����������. (���. ���� - �������� ); 60° ����� , ���� -������� ����� ������� (�������� ����� ). ������������ ����������� 3 ������������� : ����� , ���������. References: Thompson, Perry eds. (1997) Applied Climatology; Wenger (1984) Recommended reading: IPCC WG 1 Assessment reports ; Houghton (1996) Crutzen (1996) Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology III. Gen ����������� References: Thompson, Perry eds. (1997) Applied Climatology; Wenger (1984) Recommended reading: IPCC WG 1 Assessment reports ; Houghton (1996) Crutzen (1996) Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

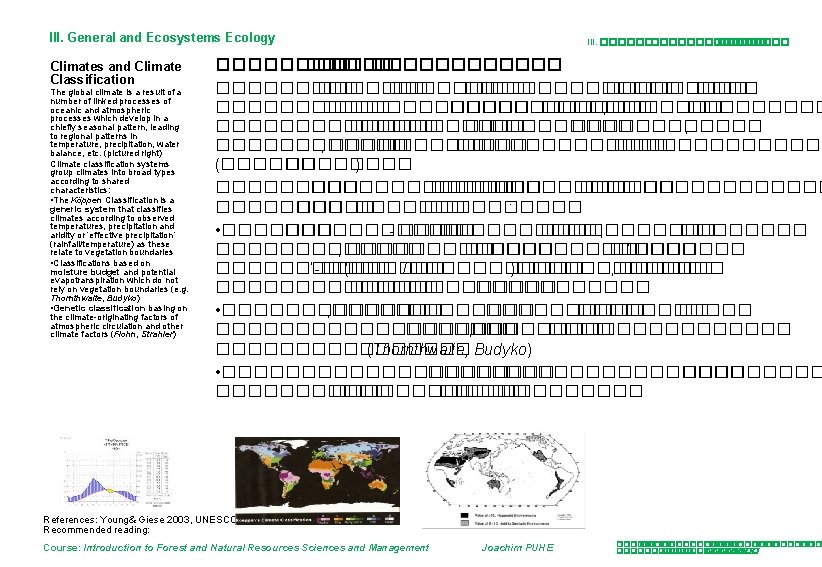

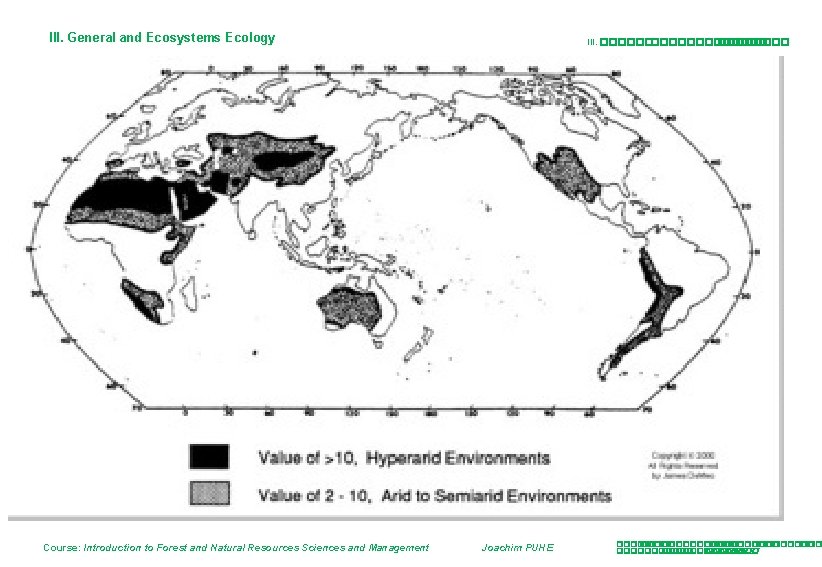

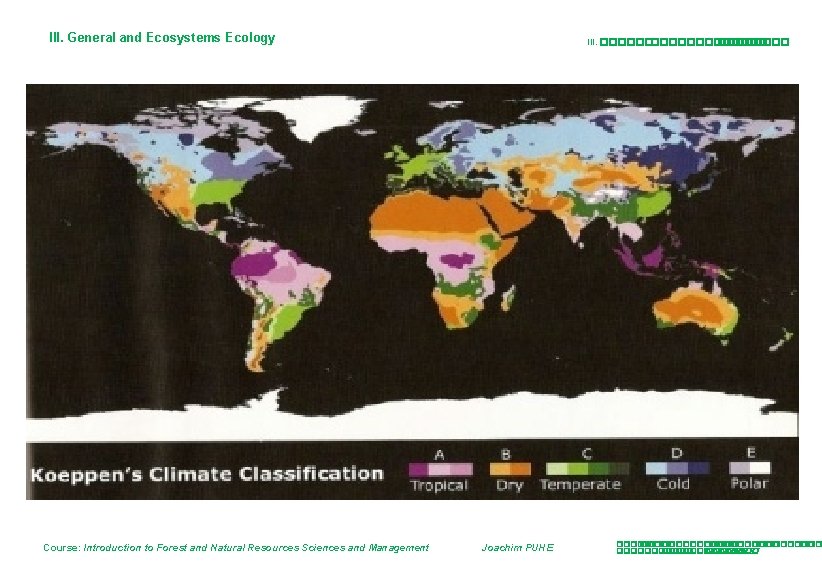

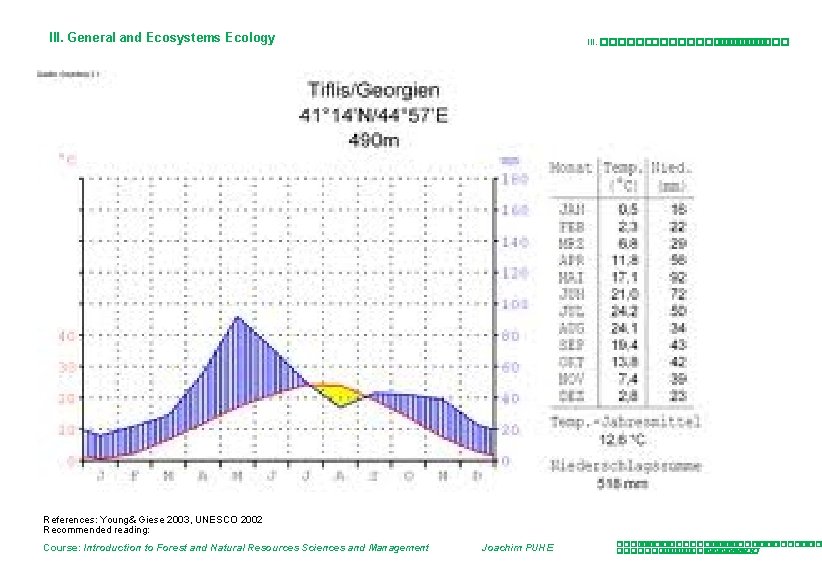

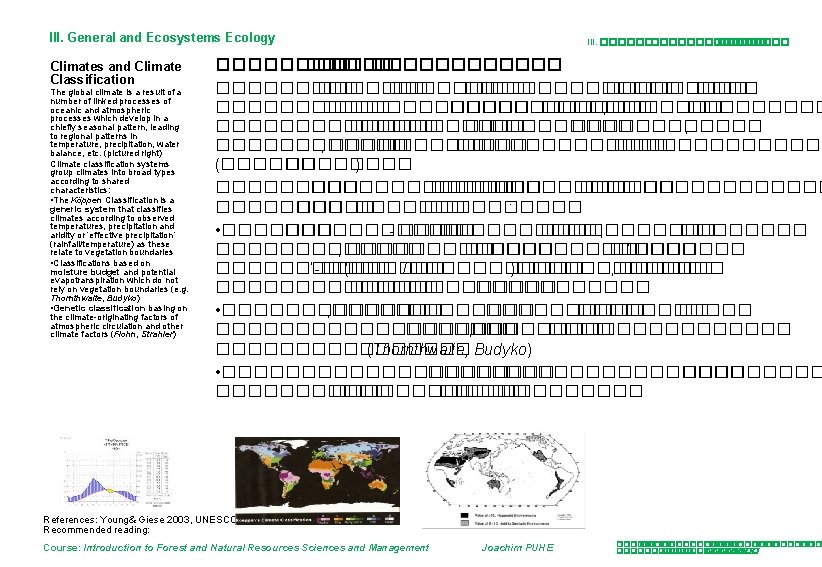

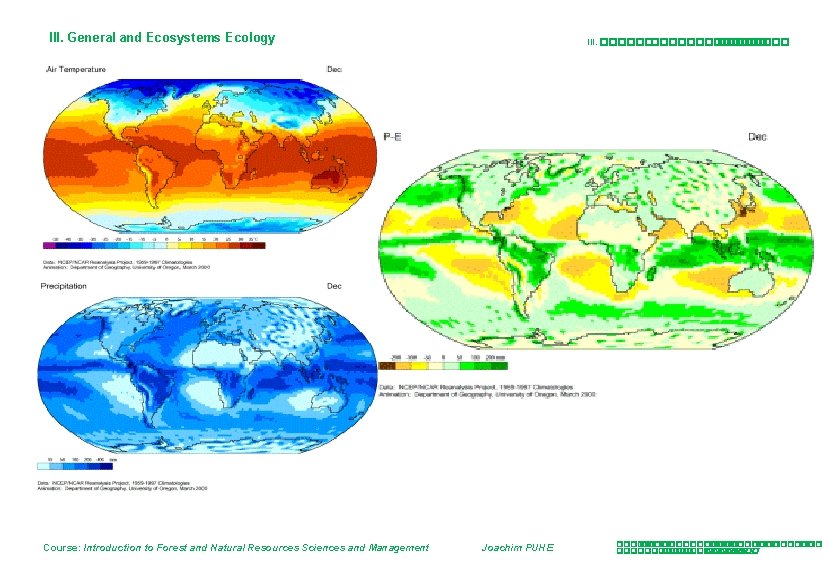

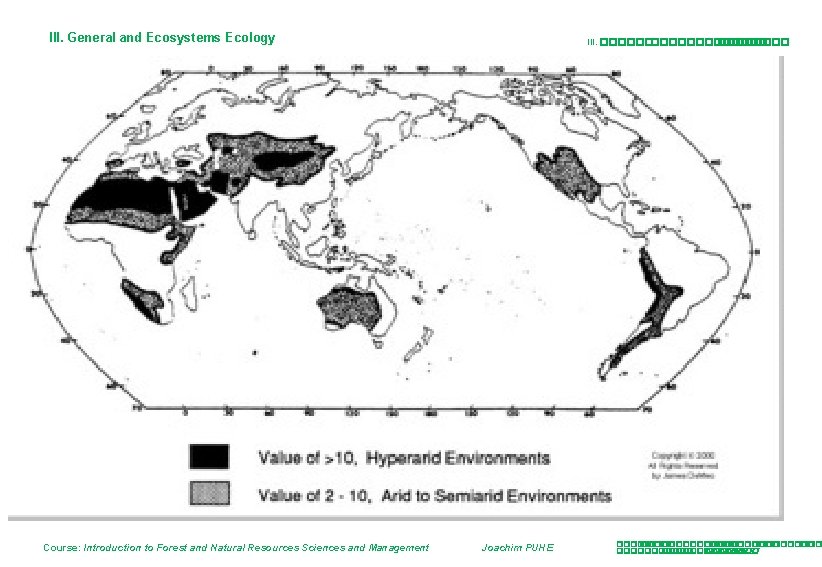

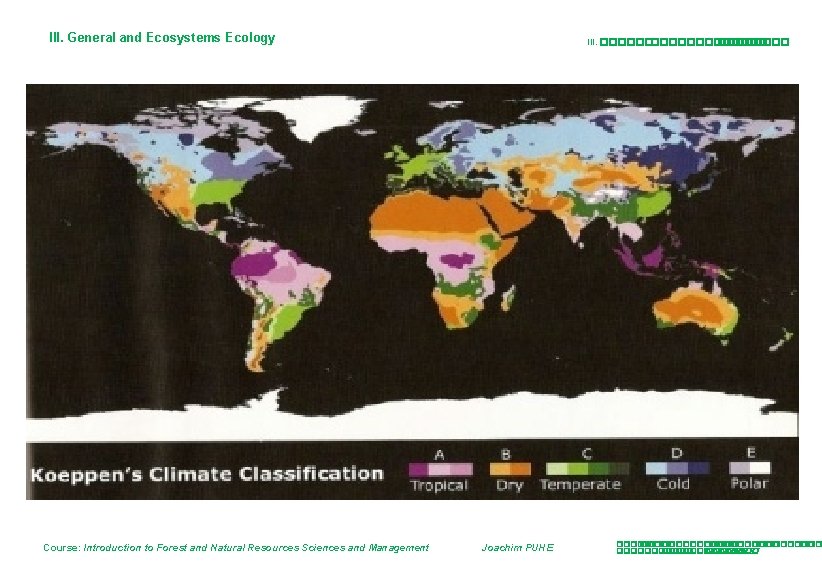

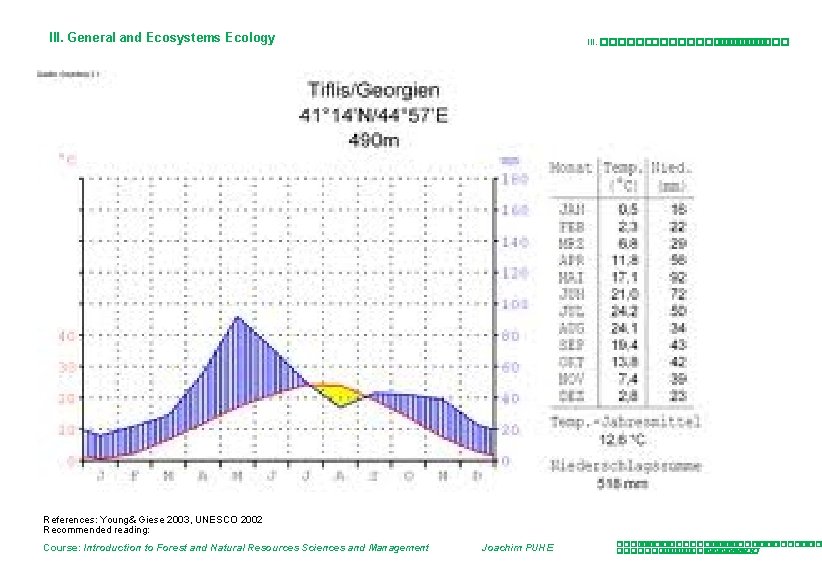

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology Climates and Climate Classification The global climate is a result of a number of linked processes of oceanic and atmospheric processes which develop in a chiefly seasonal pattern, leading to regional patterns in temperature, precipitation, water balance, etc. (pictured right) Climate classification systems group climates into broad types according to shared characteristics: • The Köppen Classification is a generic system that classifies climates according to observed temperatures, precipitation and aridity or ‘effective precipitation’ (rainfall/temperature) as these relate to vegetation boundaries • Classifications based on moisture budget and potential evapotranspiration which do not rely on vegetation boundaries (e. g. Thornthwaite, Budyko) • Genetic classification basing on the climate-originating factors of atmospheric circulation and other climate factors (Flohn, Strahler) III. ����������� ������������ ��������� ����������� ������� , ��������� ������������ , ������������. (������ ) ������������� ������ ������� : • ������������ - ���������� ������� , ��������������� �� “������� ”-�� (������ /������ )������ , ������� �������. • ������ , ����������� �� ���������� , ������� �������� (Thornthwaite, Budyko) • ������������ ����������� ���������. References: Young& Giese 2003, UNESCO 2002 Recommended reading: Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management III. ����������� Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management III. ����������� Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management III. ����������� Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology III. ����������� References: Young& Giese 2003, UNESCO 2002 Recommended reading: Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

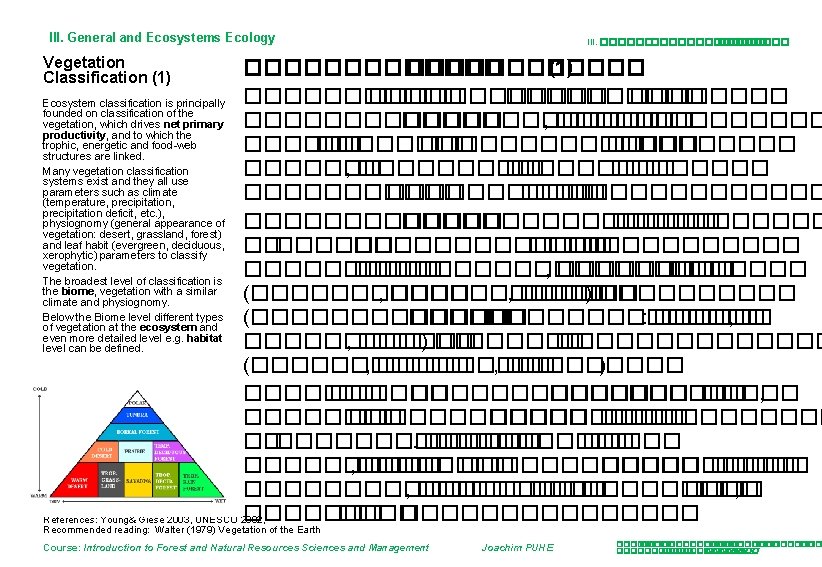

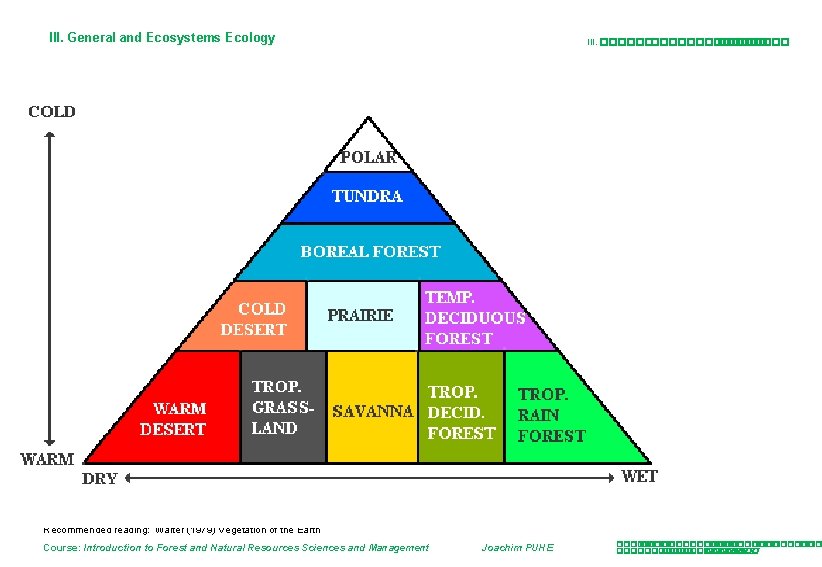

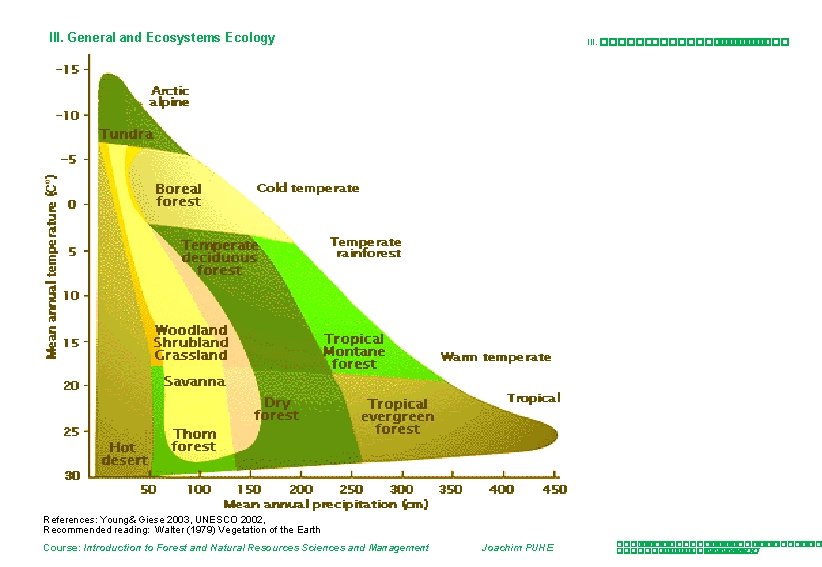

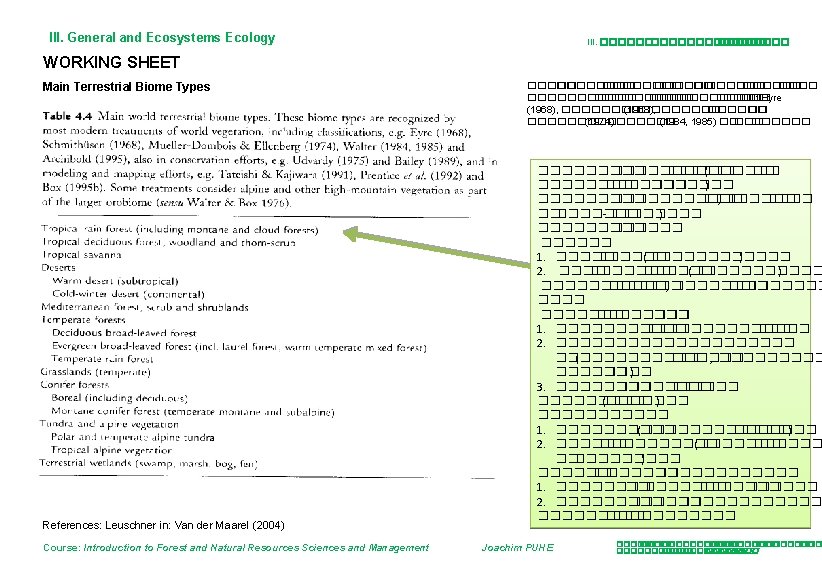

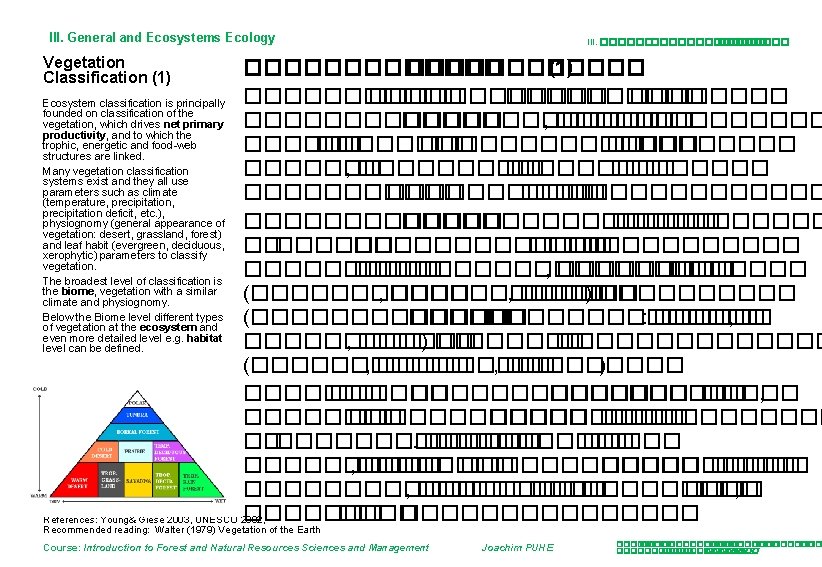

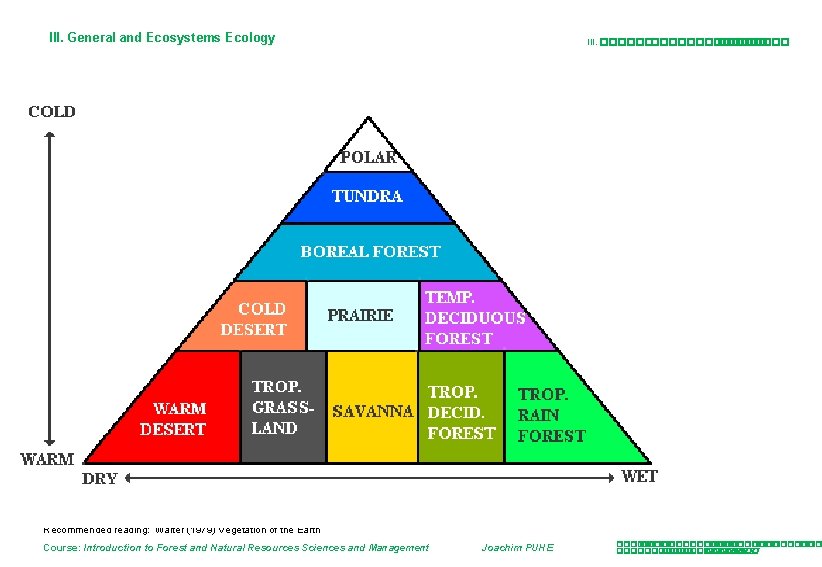

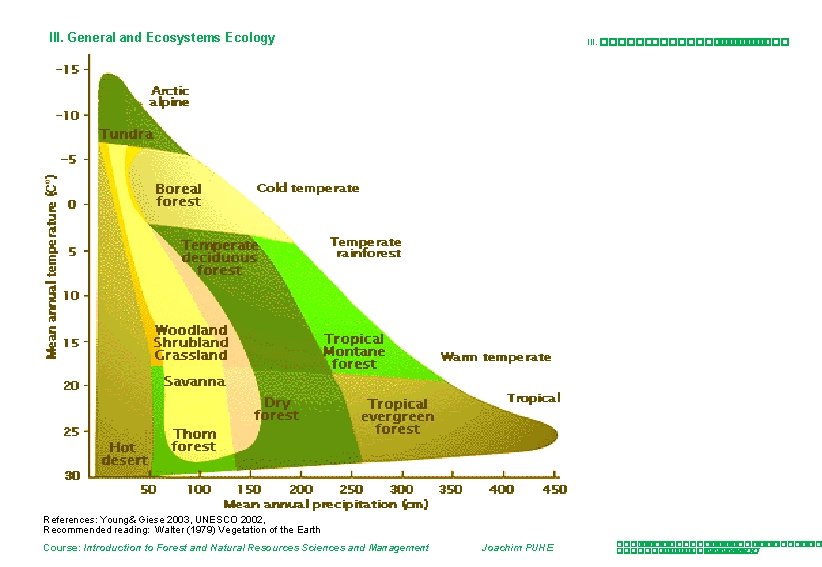

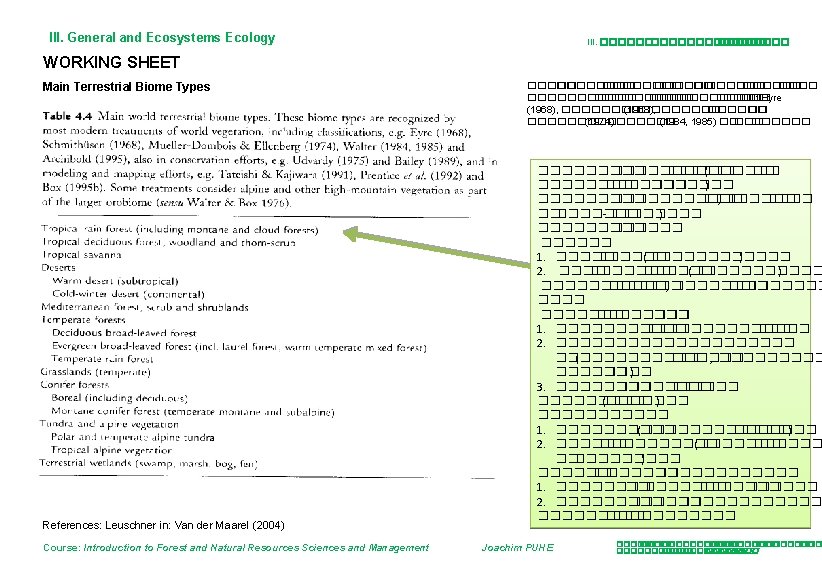

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology III. ����������� Vegetation Classification (1) ������� (1) ������������ ���� Ecosystem classification is principally founded on classification of the ������������� , ��������� vegetation, which drives net primary productivity, and to which the trophic, energetic and food-web �������� ����� structures are linked. Many vegetation classification ������� , ������ ���� systems exist and they all use parameters such as climate �����������. (temperature, precipitation deficit, etc. ), physiognomy (general appearance of ������������� ������� vegetation: desert, grassland, forest) and leaf habit (evergreen, deciduous, ����������� xerophytic) parameters to classify vegetation. ����������������� , ������� The broadest level of classification is the biome, vegetation with a similar (����������� , ������ ) ����� climate and physiognomy. Below the Biome level different types (���������� : ������ , of vegetation at the ecosystem and even more detailed level e. g. habitat ����� , ������ ) �������������� level can be defined. (������ , ��������� ) ������� ������� , ������������ ���������� , ������������ ���������� , ������ ���� , ��������. References: Young& Giese 2003, UNESCO 2002, Recommended reading: Walter (1979) Vegetation of the Earth Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

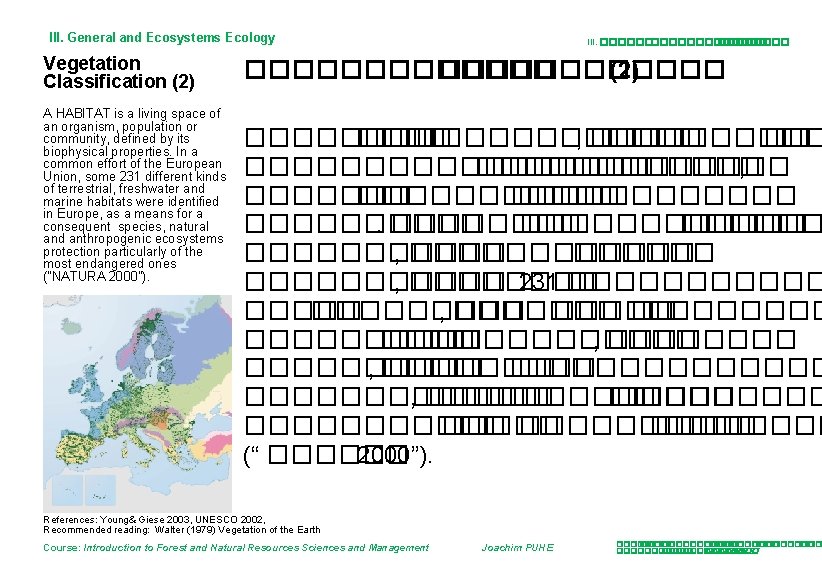

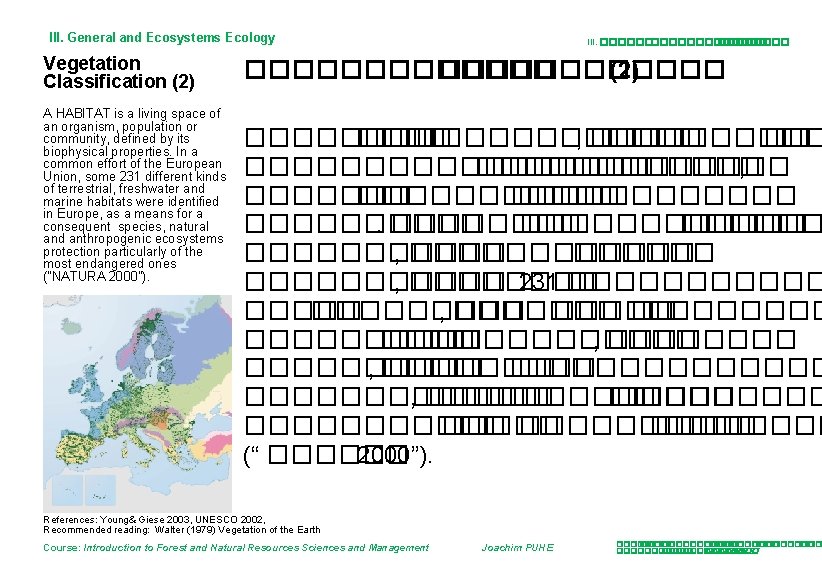

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology Vegetation Classification (2) A HABITAT is a living space of an organism, population or community, defined by its biophysical properties. In a common effort of the European Union, some 231 different kinds of terrestrial, freshwater and marine habitats were identified in Europe, as a means for a consequent species, natural and anthropogenic ecosystems protection particularly of the most endangered ones (“NATURA 2000”). III. ������������� ������ (2) �������� , ����� �� ��������� ������ , ����������� ������������ ����������� , �������� 231 ��������� , ��������� ������ , ����������������� , ������� �� �������� ����� (“ ������ 2000”). References: Young& Giese 2003, UNESCO 2002, Recommended reading: Walter (1979) Vegetation of the Earth Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

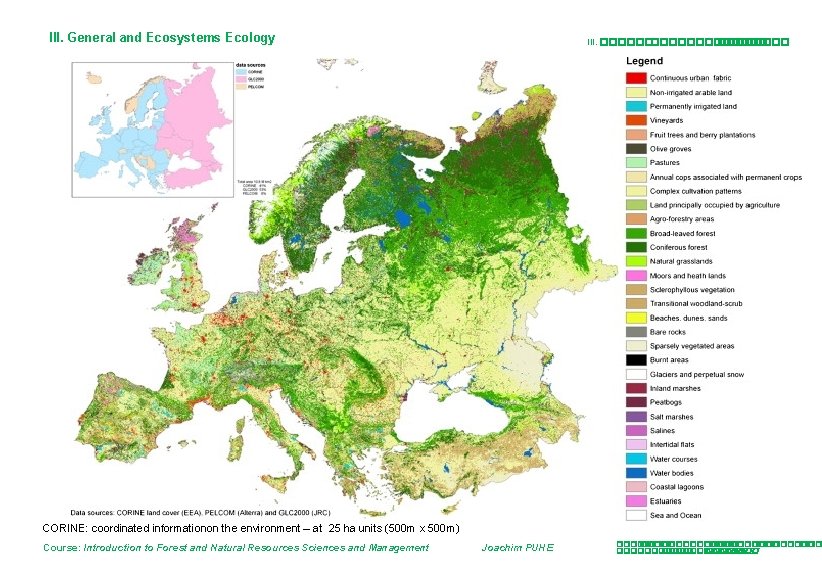

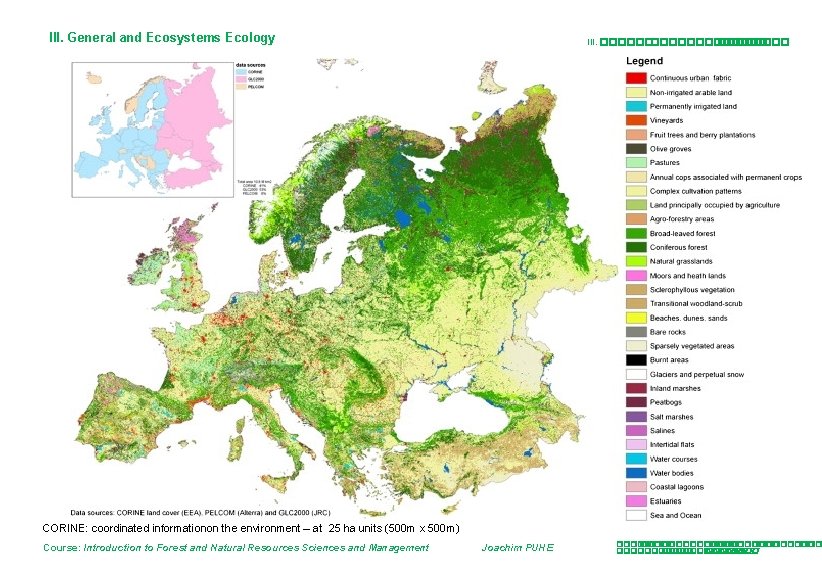

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology III. ����������� CORINE: coordinated informationon the environment – at 25 ha units (500 m x 500 m) Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

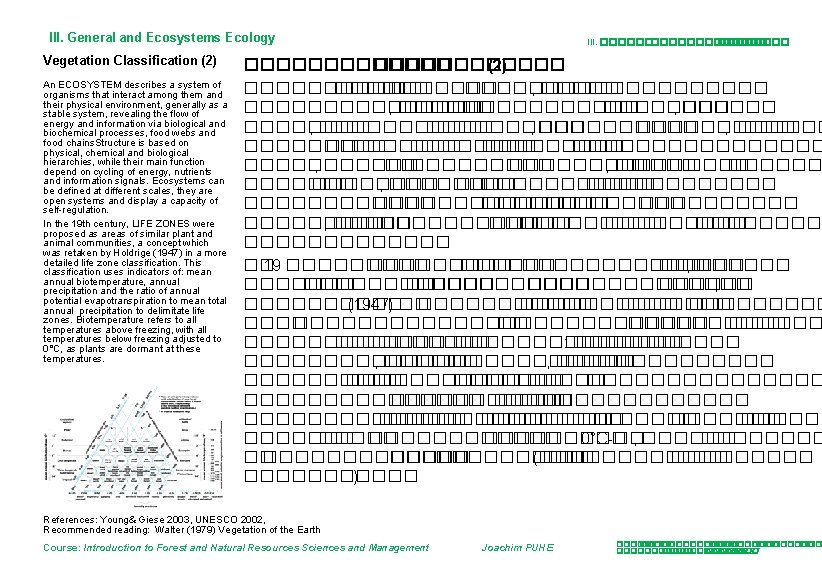

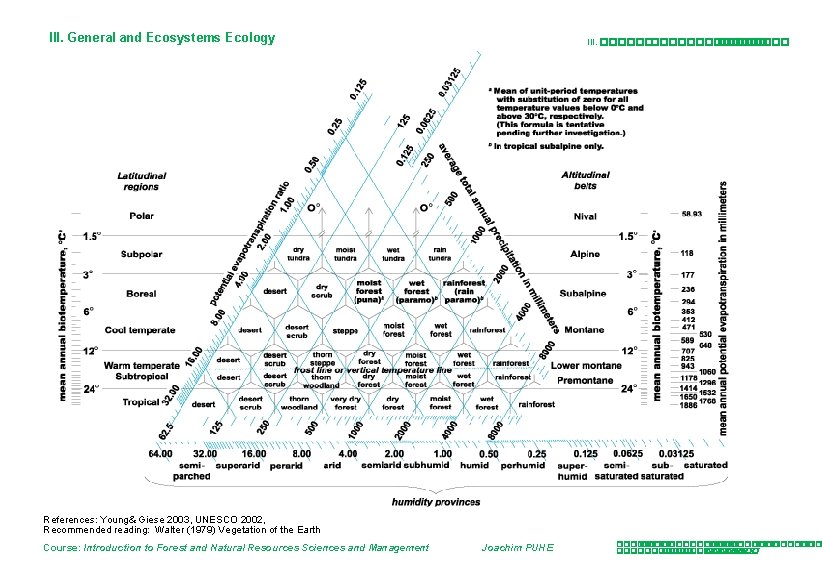

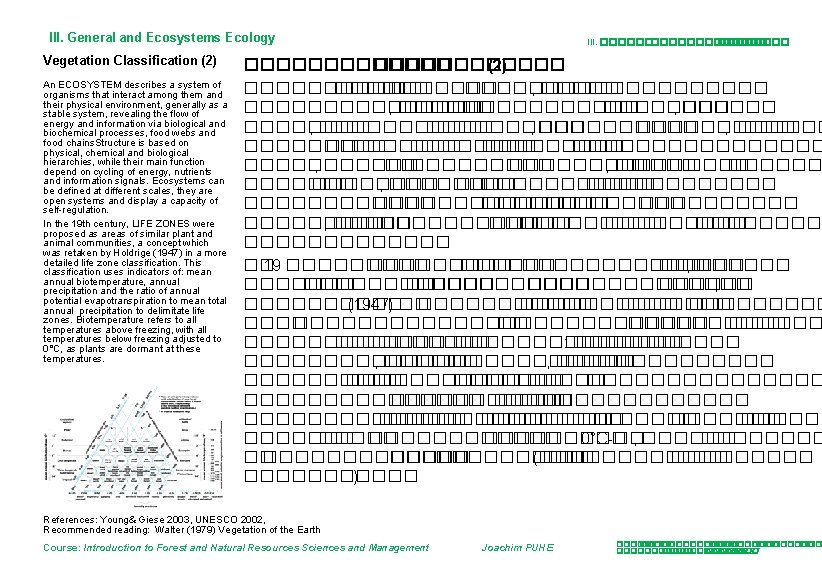

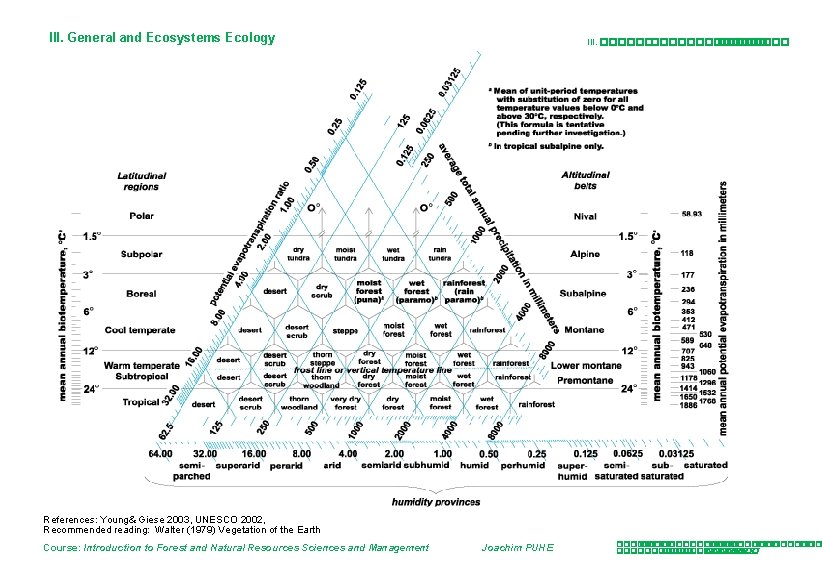

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology Vegetation Classification (2) An ECOSYSTEM describes a system of organisms that interact among them and their physical environment, generally as a stable system, revealing the flow of energy and information via biological and biochemical processes, food webs and food chains. Structure is based on physical, chemical and biological hierarchies, while their main function depend on cycling of energy, nutrients and information signals. Ecosystems can be defined at different scales, they are open systems and display a capacity of self-regulation. In the 19 th century, LIFE ZONES were proposed as areas of similar plant and animal communities, a concept which was retaken by Holdrige (1947) in a more detailed life zone classification. This classification uses indicators of: mean annual biotemperature, annual precipitation and the ratio of annual potential evapotranspiration to mean total annual precipitation to delimitate life zones. Biotemperature refers to all temperatures above freezing, with all temperatures below freezing adjusted to 0°C, as plants are dormant at these temperatures. III. ������������� ������ (2) ������� ���� , ����������� �������� , �������� , ���������� , ��������� ���������� , ����������� , �� ������� ���� , ������������� �������� ����� , ������������ �������. �� 19 ���������� ��� , �������������� ������ , ����� (1947) �� ���������� ���������� ���������� ������ : ������� , ����������� , ����������� �������� ��������� ������ ������� ��������� 0°C-�� , �������� ���������� (��� ��������� ) References: Young& Giese 2003, UNESCO 2002, Recommended reading: Walter (1979) Vegetation of the Earth Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology III. ����������� References: Young& Giese 2003, UNESCO 2002, Recommended reading: Walter (1979) Vegetation of the Earth Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology III. ����������� References: Young& Giese 2003, UNESCO 2002, Recommended reading: Walter (1979) Vegetation of the Earth Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology III. ����������� References: Young& Giese 2003, UNESCO 2002, Recommended reading: Walter (1979) Vegetation of the Earth Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

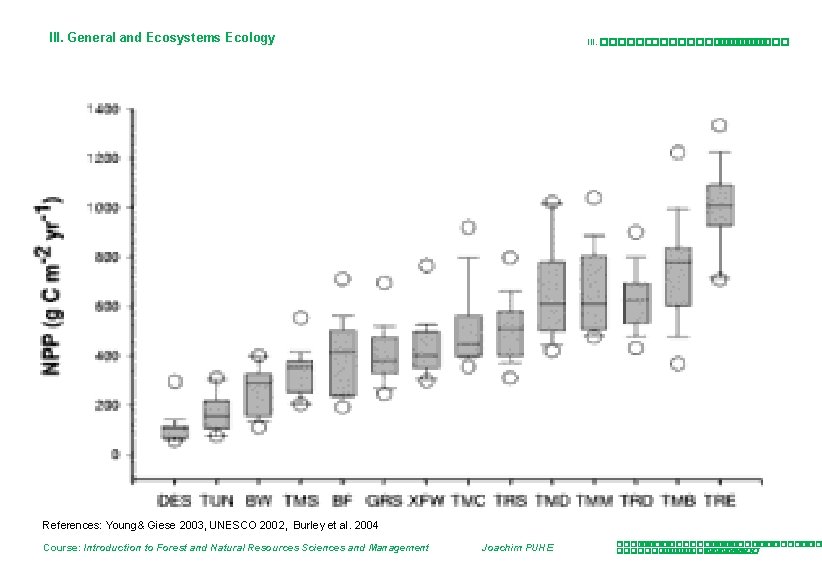

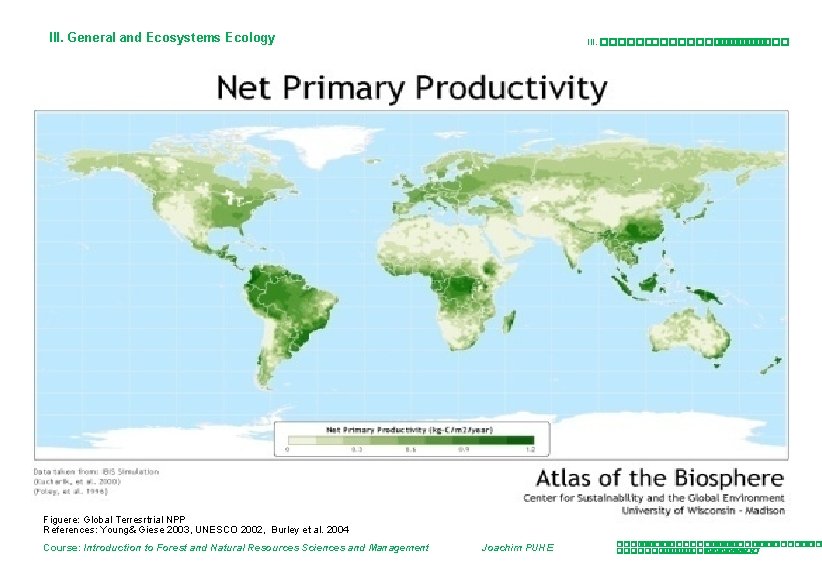

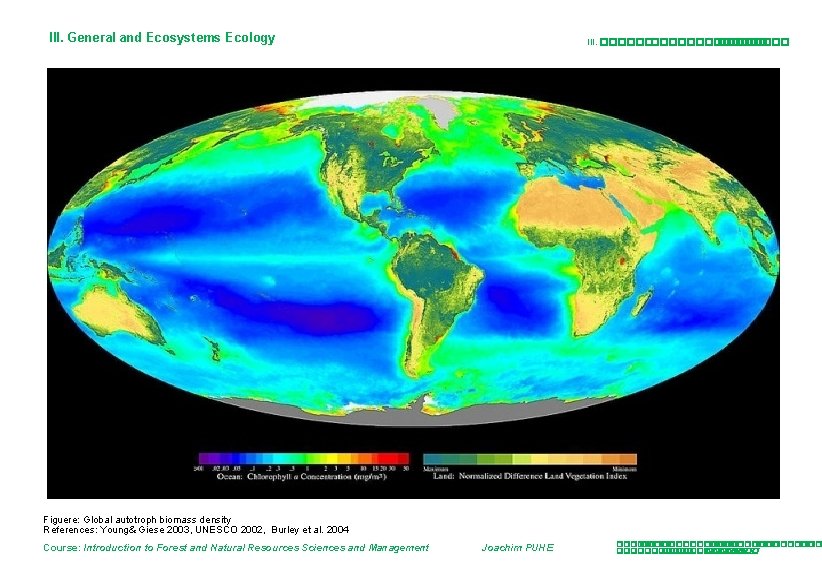

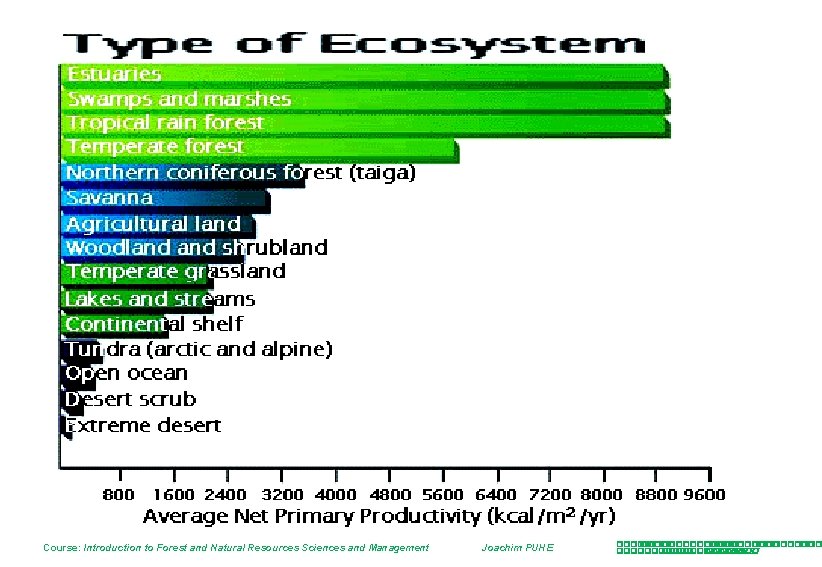

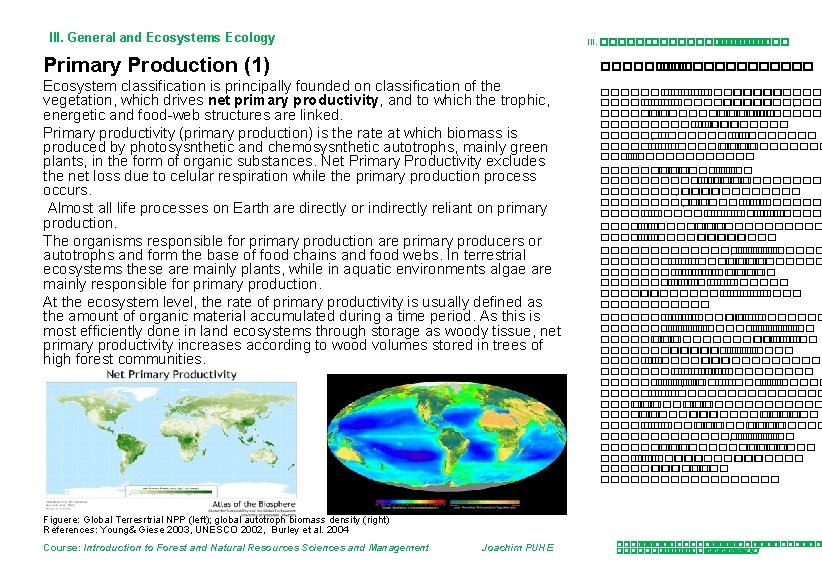

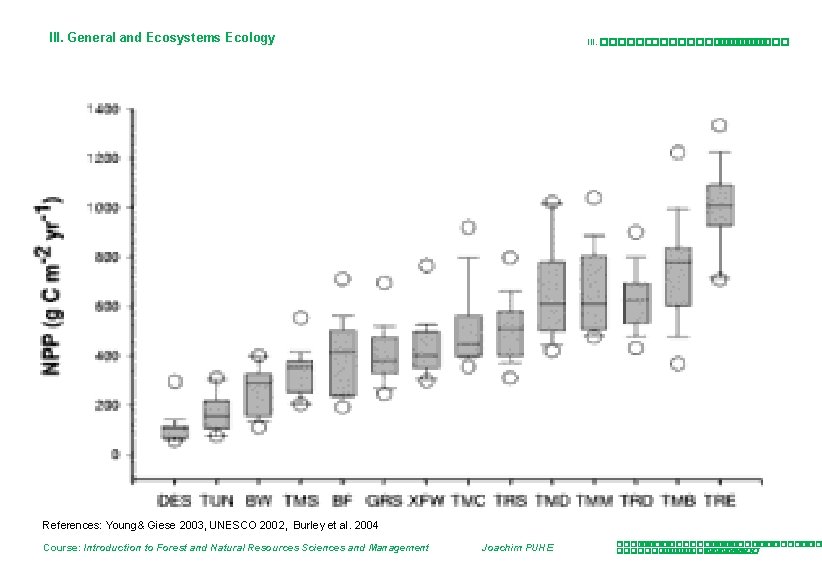

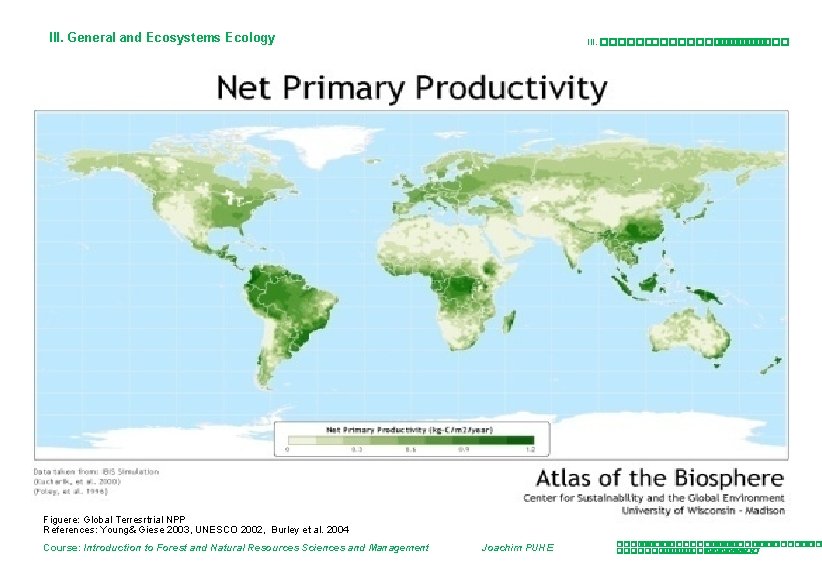

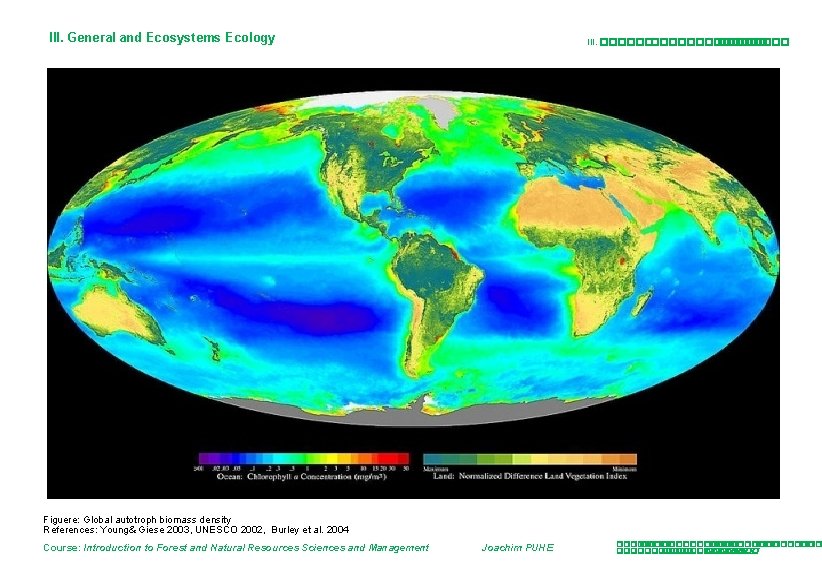

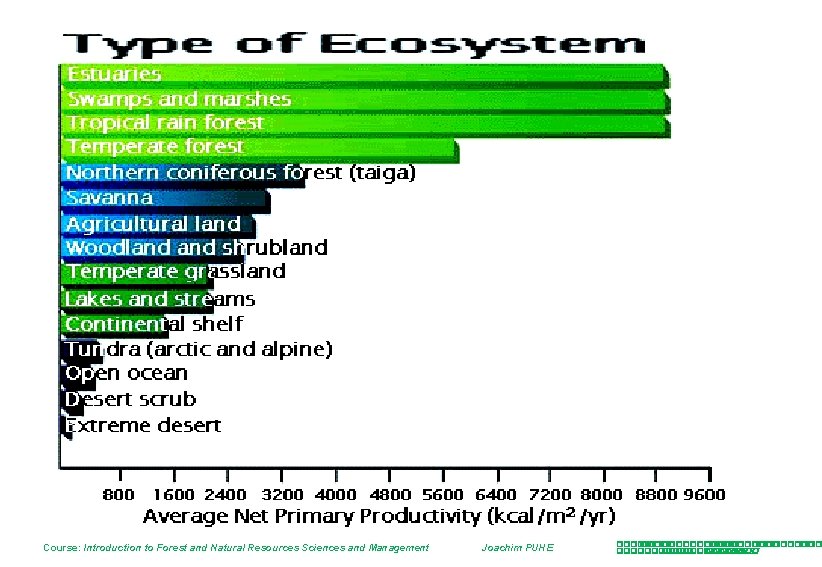

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology III. ����������� Primary Production (1) �������������� Ecosystem classification is principally founded on classification of the vegetation, which drives net primary productivity, and to which the trophic, energetic and food-web structures are linked. Primary productivity (primary production) is the rate at which biomass is produced by photosysnthetic and chemosysnthetic autotrophs, mainly green plants, in the form of organic substances. Net Primary Productivity excludes the net loss due to celular respiration while the primary production process occurs. Almost all life processes on Earth are directly or indirectly reliant on primary production. The organisms responsible for primary production are primary producers or autotrophs and form the base of food chains and food webs. In terrestrial ecosystems these are mainly plants, while in aquatic environments algae are mainly responsible for primary production. At the ecosystem level, the rate of primary productivity is usually defined as the amount of organic material accumulated during a time period. As this is most efficiently done in land ecosystems through storage as woody tissue, net primary productivity increases according to wood volumes stored in trees of high forest communities. ������������ ������������� , ������������ ������� , ������ ����������� �������� ��������������� , ����������� , ���������� ��������� ����������� ������ , ���������� �������� �� ����������� �� ����������� �������� ������������ ������������� ����� , �������� ������������ ������������� �������� ������ , ��������� ��������� �������� ���������. Figuere: Global Terresrtrial NPP (left); global autotroph biomass density (right) References: Young& Giese 2003, UNESCO 2002, Burley et al. 2004 Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology III. ����������� Primary Production (2) The standing biomass or standing crop of an ecosystem is the amount of biomass (approx. 50% of dry biomass is Carbon) present in the total of living organisms of an ecosystem, producers, consumers and decomposers, or of a particular set (e. g. species) plants of an ecosystem, usually measured as mass per surface area (g/m 2; t/ha, etc. ). Part of primary production can be transformed and passed to other spheres of the ecosystem, e. g. as carbon or nutrients to the soil and soil organic matter; or it is consumed and returned to the atmosphere or hydrosphere by decomposition and turnover. In the oceans, photosynthesis by algae in the upper 100 m of surface waters accounts for most primary production. Waters of tropical areas are less productive than those of the temperate zone, as in the tropics the water column undergoes much less seasonal vertical mixing and so becomes oligotroph. Areas of upwelling of nutrient-rich deep water have high productivity. Figuere: Global Terresrtrial NPP (left); global autotroph biomass density (right) References: Young& Giese 2003, UNESCO 2002, Burley et al. 2004 Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE �������������� (ii) ������ �� ���������� �������� (����� 50% ��������� ) ������� ����������� , ������������� ������ , ��������� ���� (g/m 2; t/ha, �� �. �. ) �������������� ���������� ��������� , ���������� �� ���������� ������� , �� ���������� �� ��������� �������������� 100 �. ����������������� �������� ������� , ���������� ������ ������������� ��������� ����� : ����������� �� ����������

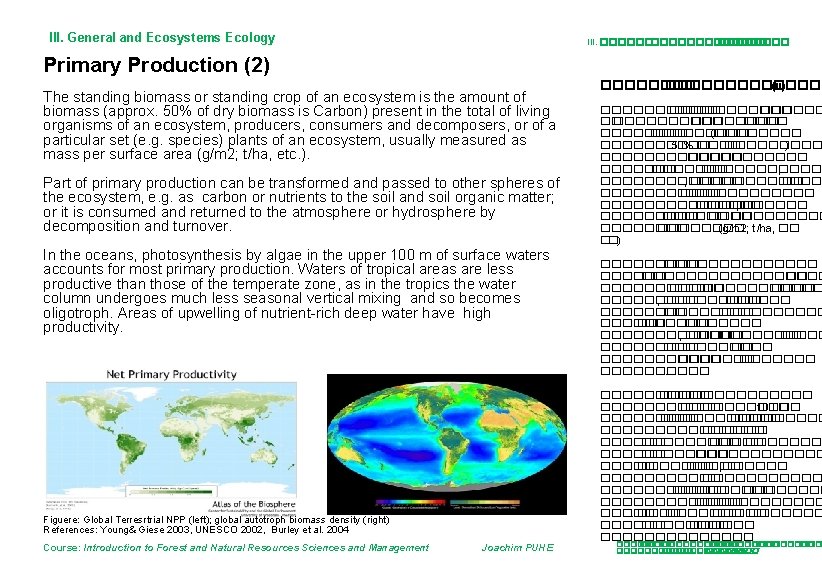

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology III. ����������� References: Young& Giese 2003, UNESCO 2002, Burley et al. 2004 Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology III. ����������� Figuere: Global Terresrtrial NPP References: Young& Giese 2003, UNESCO 2002, Burley et al. 2004 Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology III. ����������� Figuere: Global autotroph biomass density References: Young& Giese 2003, UNESCO 2002, Burley et al. 2004 Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

5. General and Ecosystems Ecology Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management 5. General and Ecosystems Ecology Cycles Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

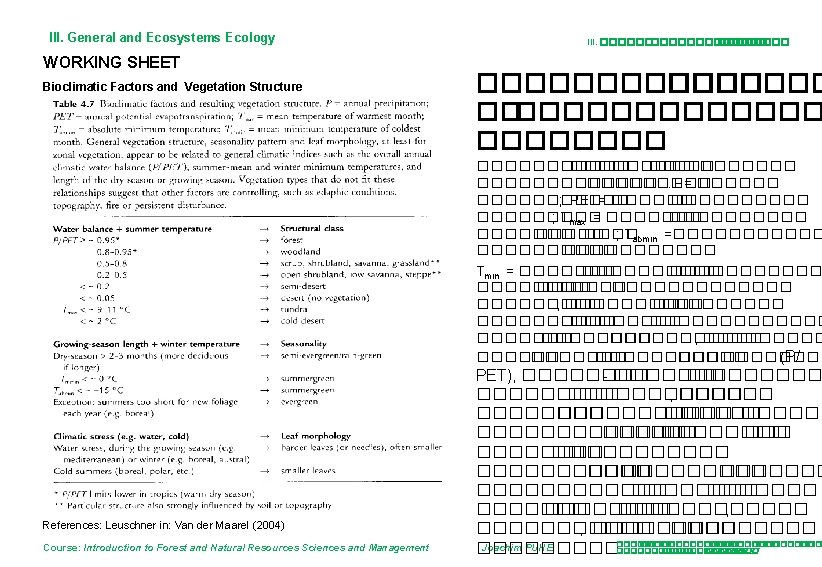

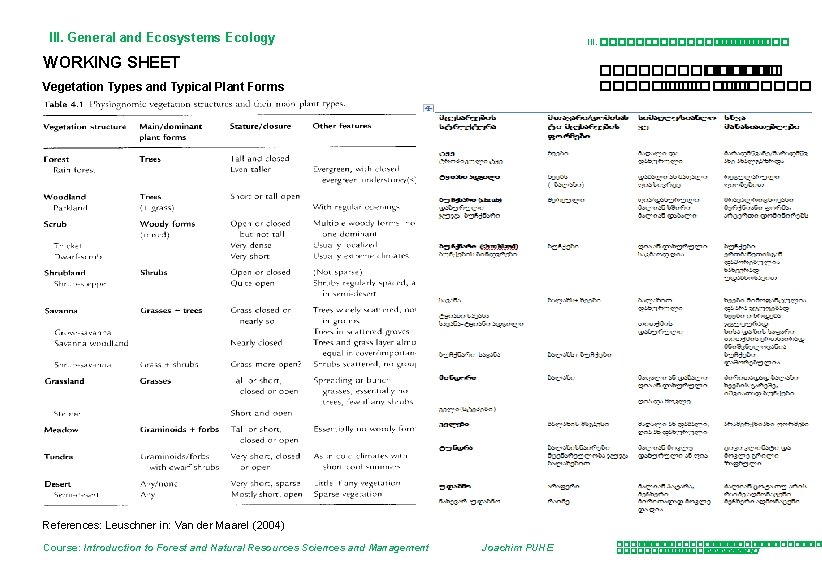

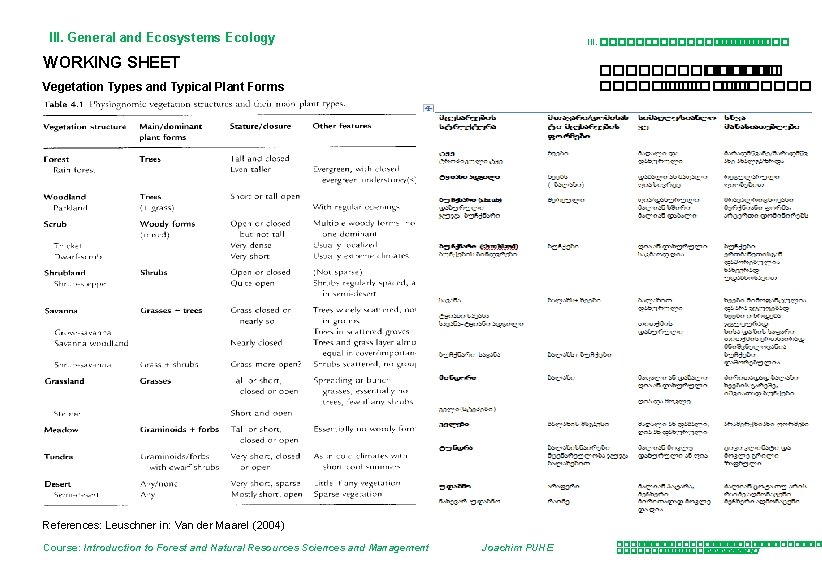

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology III. ����������� WORKING SHEET ������� �� ������� Vegetation Types and Typical Plant Forms References: Leuschner in: Van der Maarel (2004) Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

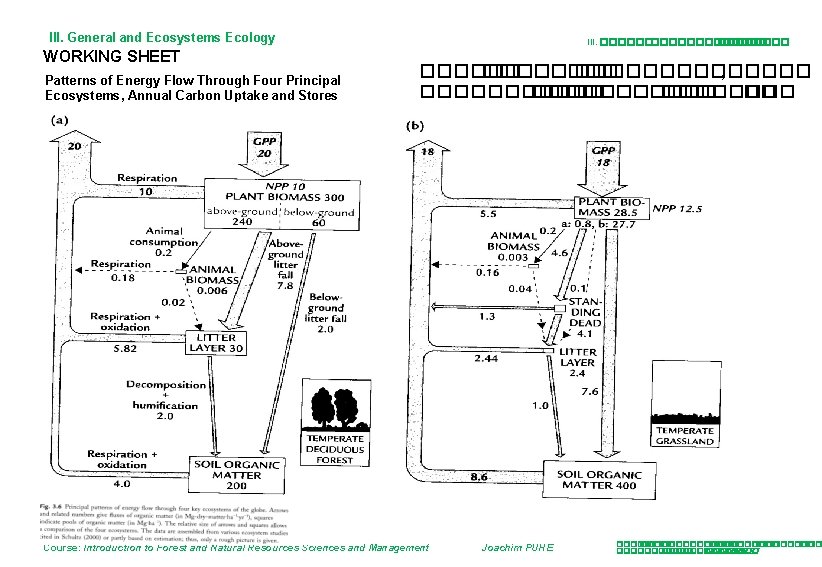

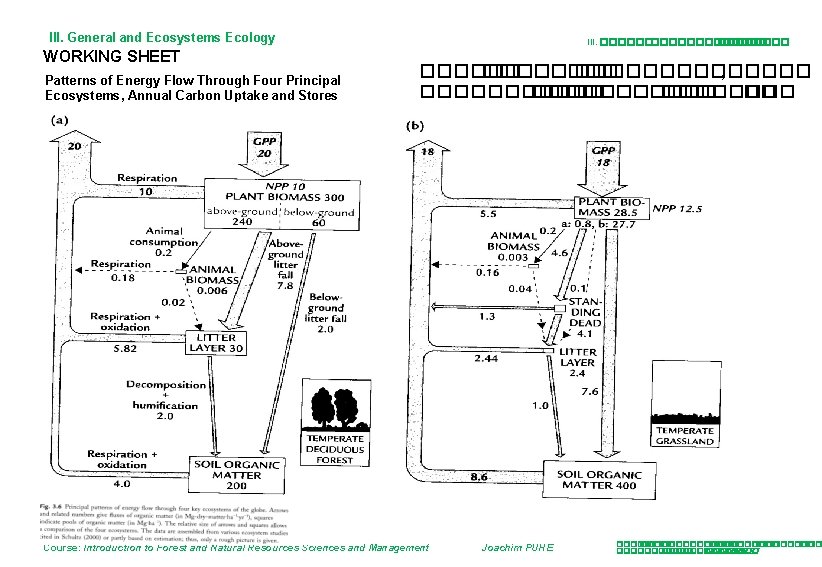

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology WORKING SHEET Patterns of Energy Flow Through Four Principal Ecosystems, Annual Carbon Uptake and Stores III. ����������� ���������� , ����������� �� ������. Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

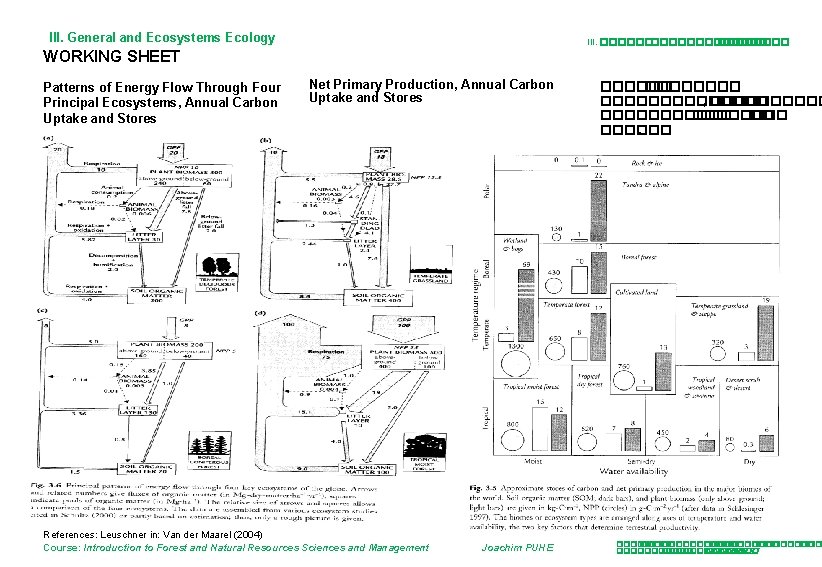

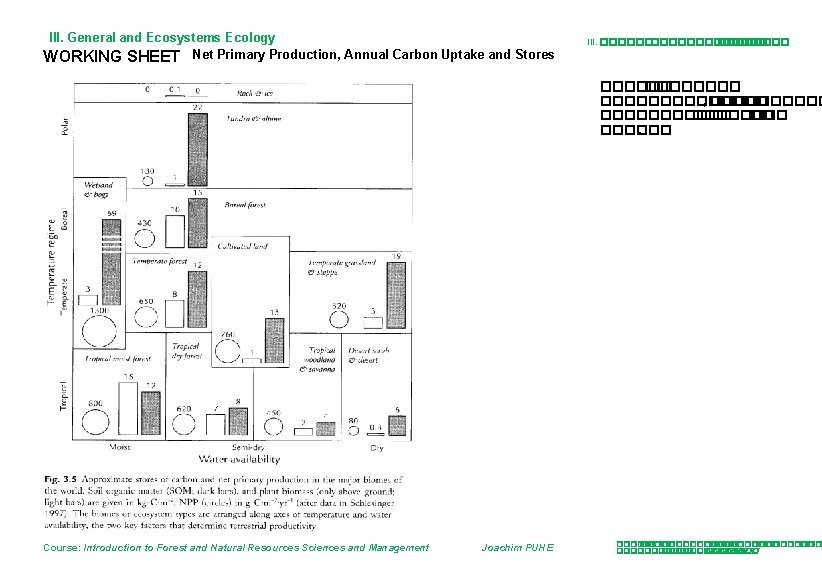

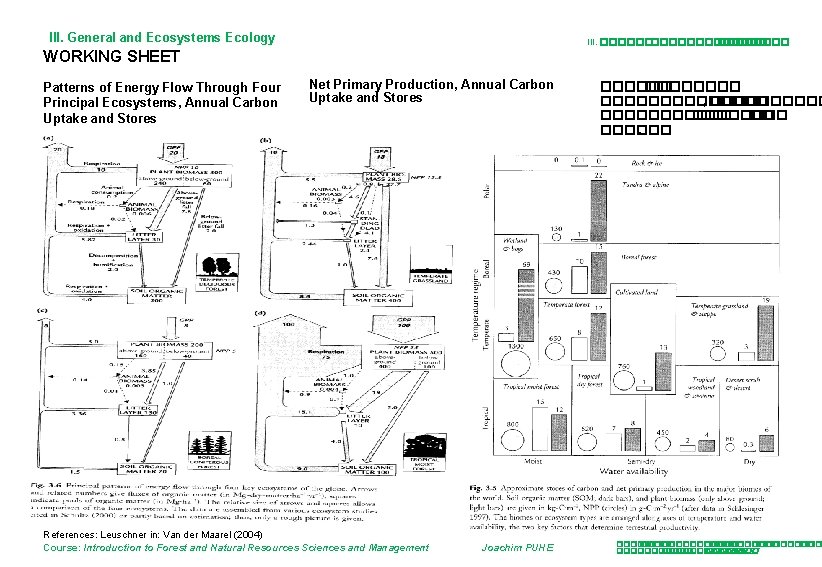

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology III. ����������� WORKING SHEET Patterns of Energy Flow Through Four Principal Ecosystems, Annual Carbon Uptake and Stores Net Primary Production, Annual Carbon Uptake and Stores References: Leuschner in: Van der Maarel (2004) Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE �������� , ����������� �� ������. ����� : ����������� �� ����������

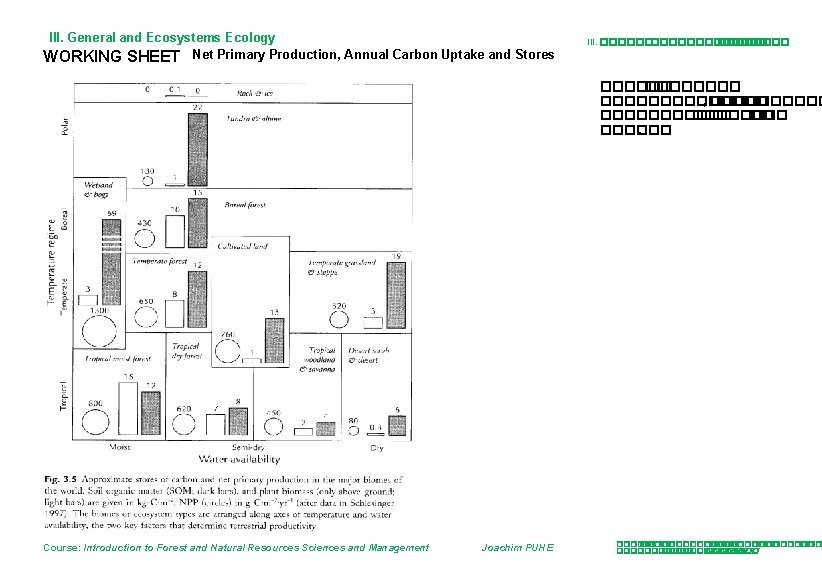

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology WORKING SHEET Net Primary Production, Annual Carbon Uptake and Stores III. ����������� ���������� , ����������� �� ������. Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

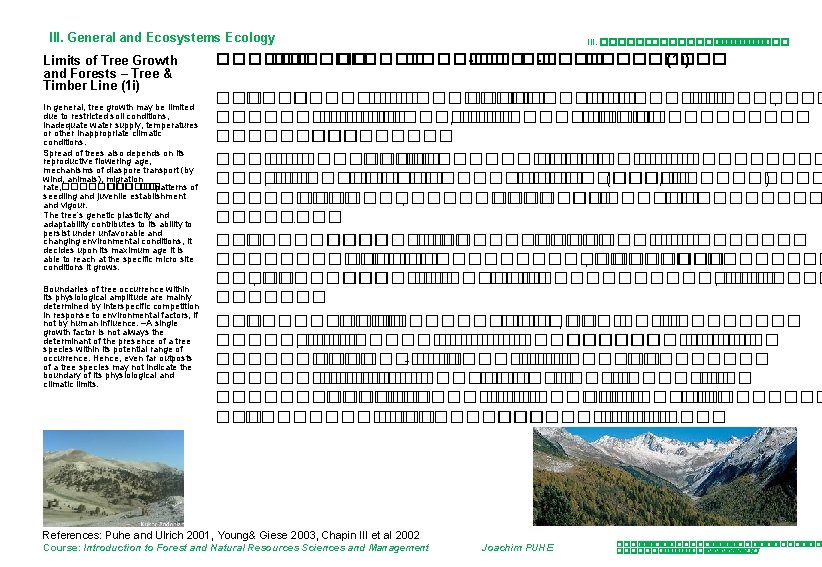

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology Limits of Tree Growth and Forests – Tree & Timber Line (1 i) In general, tree growth may be limited due to restricted soil conditions, inadequate water supply, temperatures or other inappropriate climatic conditions. Spread of trees also depends on its reproductive flowering age, mechanisms of diaspore transport (by wind, animals), migration rate, ������ ��patterns of seedling and juvenile establishment and vigour. The tree’s genetic plasticity and adaptability contributes to its ability to persist under unfavorable and changing environmental conditions, it decides upon its maximum age it is able to reach at the specific micro site conditions it grows. Boundaries of tree occurrence within its physiological amplitude are mainly determined by interspecific competition in response to environmental factors, if not by human influence. –A single growth factor is not always the determinant of the presence of a tree species within its potential range of occurrence. Hence, even far outposts of a tree species may not indicate the boundary of its physiological and climatic limits. III. ����������� ������ -�� ���� -����� (1 i) ������������ ��������� , ������ �� ����������� ������������ , ����������� (����� , ����� ) ������������ , ��������� �������� �������� ���������� , �� ������� ����� , �������� �� ����� , ���������� ������ , ��������� , �������������� ����������. - ��������� ��������� ����� �� �������� �� �������� ��� ����������� ����. References: Puhe and Ulrich 2001, Young& Giese 2003, Chapin III et al 2002 Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

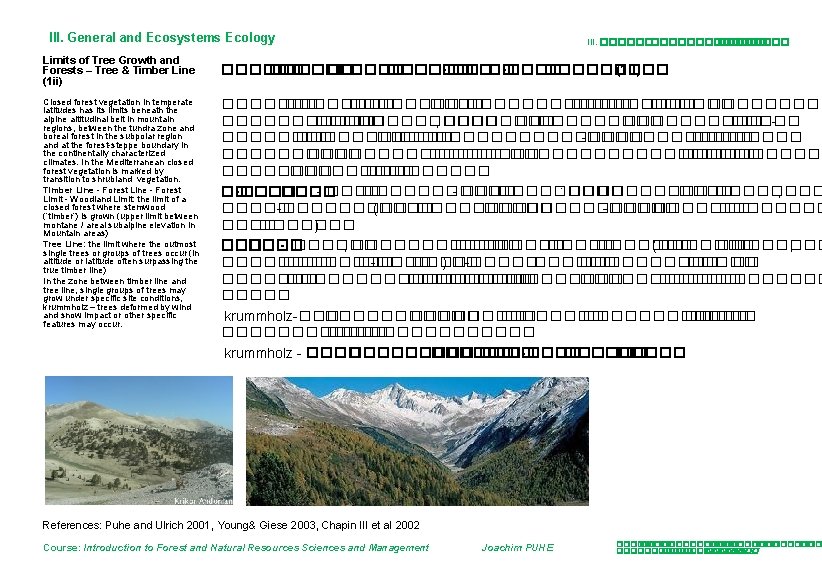

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology Limits of Tree Growth and Forests – Tree & Timber Line (1 ii) Closed forest vegetation in temperate latitudes has its limits beneath the alpine altitudinal belt in mountain regions, between the tundra zone and boreal forest in the subpolar region and at the forest-steppe boundary in the continentally characterized climates. In the Mediterranean closed forest vegetation is marked by transition to shrubland vegetation. Timber Line - Forest Limit - Woodland Limit: the limit of a closed forest where stemwood (‘timber’) is grown (upper limit between montane / areal subalpine elevation in Mountain areas) Tree Line: the limit where the outmost single trees or groups of trees occur (in altitude or latitude often surpassing the true timber line) In the zone between timber line and tree line, single groups of trees may grow under specific site conditions, krummholz – trees deformed by wind and snow impact or other specific features may occur. III. ����������� ������ -�� ���� -����� (1 ii) �������� ������������ ����������� , ����������� ������ ���������� -���������� �������������� ���������. �� -���� - ���������� - �������� : �������� , ����� �� -��� ������� (����� ����� -�������� ������� ) ���� - ������ , �������� ������� (������� �� ������� , �������� �� -���� ) �� -������� ���������� ��������� �����. krummholz-��� ������ ������������ ��������. krummholz - ��������� ��� �� -����� References: Puhe and Ulrich 2001, Young& Giese 2003, Chapin III et al 2002 Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

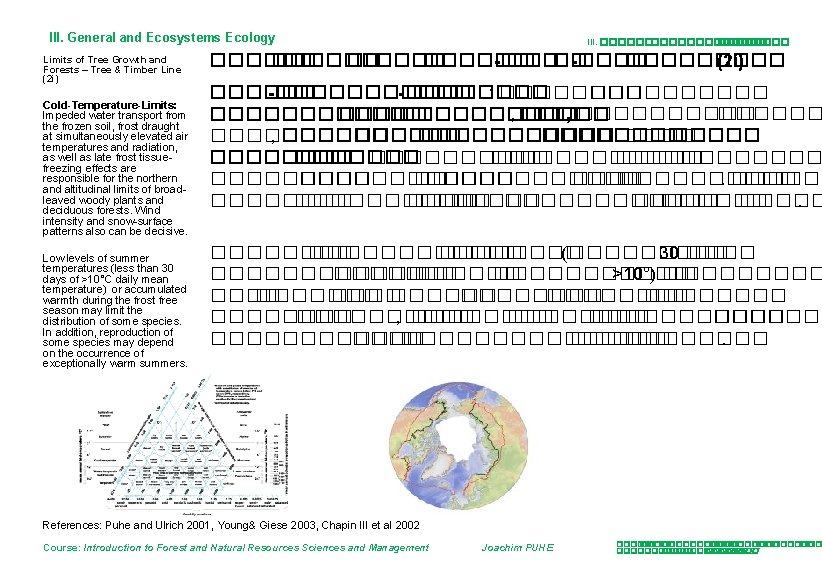

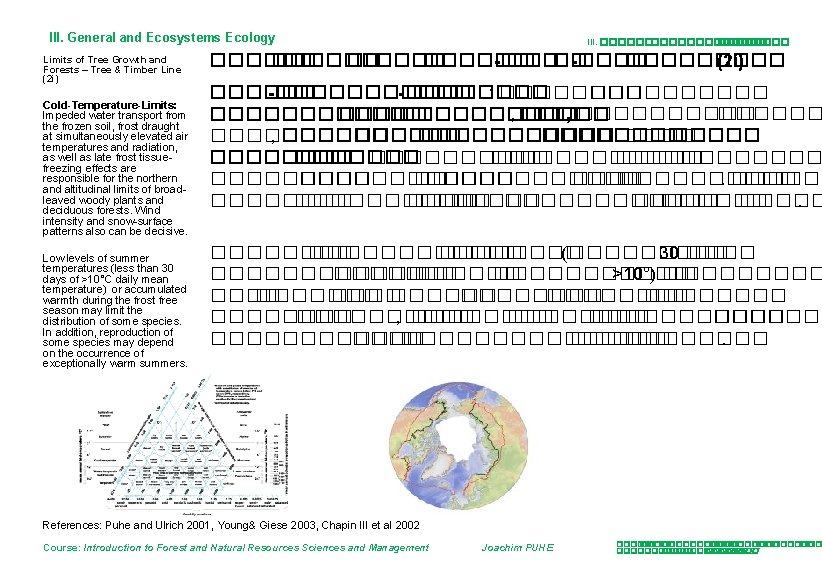

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology Limits of Tree Growth and Forests – Tree & Timber Line (2 i) Cold-Temperature-Limits: Impeded water transport from the frozen soil, frost draught at simultaneously elevated air temperatures and radiation, as well as late frost tissuefreezing effects are responsible for the northern and altitudinal limits of broadleaved woody plants and deciduous forests. Wind intensity and snow-surface patterns also can be decisive. Low levels of summer temperatures (less than 30 days of >10°C daily mean temperature) or accumulated warmth during the frost free season may limit the distribution of some species. In addition, reproduction of some species may depend on the occurrence of exceptionally warm summers. III. ����������� ������ -�� ���� -����� (2 i) ������ -�������� : ���������� ���������� , ������ ������ , ������ ����� ����������������������� ���������� ������ ������������ (����� 30 �������� ������ >10°) �� ������� �������� �������� , �������� ������������ ��������. References: Puhe and Ulrich 2001, Young& Giese 2003, Chapin III et al 2002 Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology Limits of Tree Growth and Forests – Tree & Timber Line (2 ii) Water-Limits: Towards the continental interiors water supply and the linked ratio of evapotranspiration/precipitation become decisive. With decreasing precipitation and increasing summer drought periods, forests are replaced by grassland species or nonwoody plants of the steppes. Beyond the general forest line, tree growth may only occur where ground water levels favour tree growth, e. g. in depressions or along rivers and lakes. In arid zones, however, forest growth may occur above certain altitudes, as temperatures and plant transpiration decreases with altitude, so that precipitation amounts become sufficient to reach a ‘tipping point’ forest growth. Additional precipitation, higher water ingress due to cloud-water interception and a restrained irradiation due to cloud presence may further improve the water balance and favour forest growth. Therefore in semi-arid zones, forest may appear above the steppe or semi-deserts, and they may extend upwards as far as precipitation or interception allow or until the altitudinal forest line. III. ����������� ������ -�� ���� -����� (2 ii) ���� - ����� : ������ ��������������������������� ������� ���������� �� ������������ ����� , �� ������ �� ����� , �������������� : ������������� , ������� ������������ , ����������� �������� ����� , ��� ��������� ��� �������� “������� ”. ������������ , ������� ����������� ����������������� ������� ����� �������������� �� ���������� , ����������� �������� ����� ����������. References: Puhe and Ulrich 2001, Young& Giese 2003, Chapin III et al 2002 Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology III. ����������� Limits of Tree Growth and Forests – Tree & Timber Line (2 iii) ������ -�� ���� -����� (2 iii) Towards sub-tropical latitudes and “Mediterranean type “ climates, forest growth becomes restricted because of unsuitable evapotranspiration/precipitation levels. Forest vegetation becomes restricted to the ‘cooler’ uplands, where less evapotranspiration and higher precipitation occur. In the Mediterranean lowlands, forest species are increasingly replaced by xeromorhic shrubland species of shorter heights, better adapted to draught, high solar irradiation and animal feeding. ���� , ���������������� , ������� /������ ������������ ����� , �������������� ��������� , ������� �������� ����� , ���������� , ������� , ������������. References: Puhe and Ulrich 2001, Young& Giese 2003, Chapin III et al 2002 Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

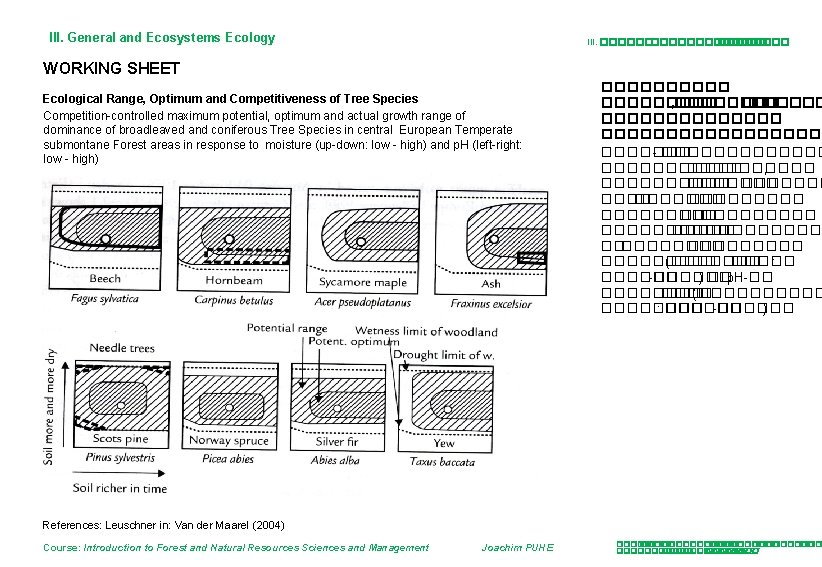

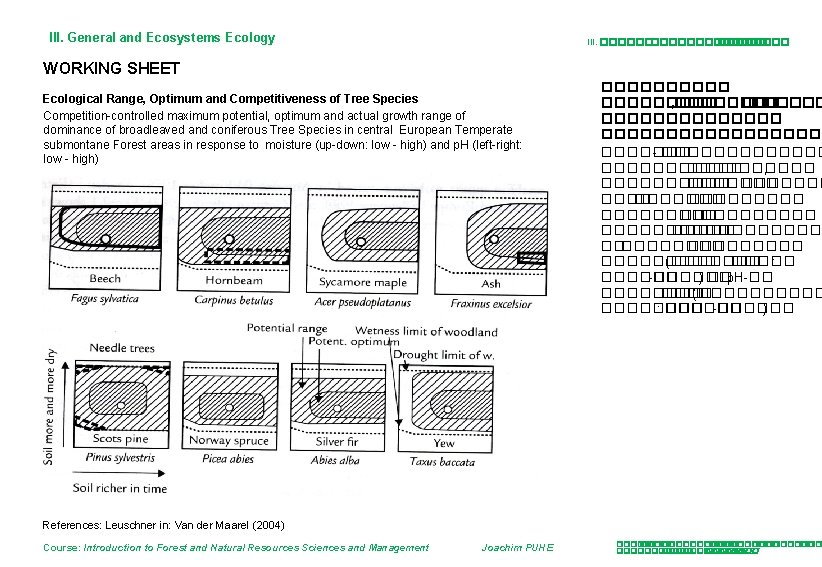

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology III. ����������� WORKING SHEET Ecological Range, Optimum and Competitiveness of Tree Species Competition-controlled maximum potential, optimum and actual growth range of dominance of broadleaved and coniferous Tree Species in central European Temperate submontane Forest areas in response to moisture (up-down: low - high) and p. H (left-right: low - high) ����� , �������������� ������� - ���������� , ������� ��������� ������ ��������� ����� (������� : ������ -������ ) ��p. H-�� ���� (����� : ������ -������ ) References: Leuschner in: Van der Maarel (2004) Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

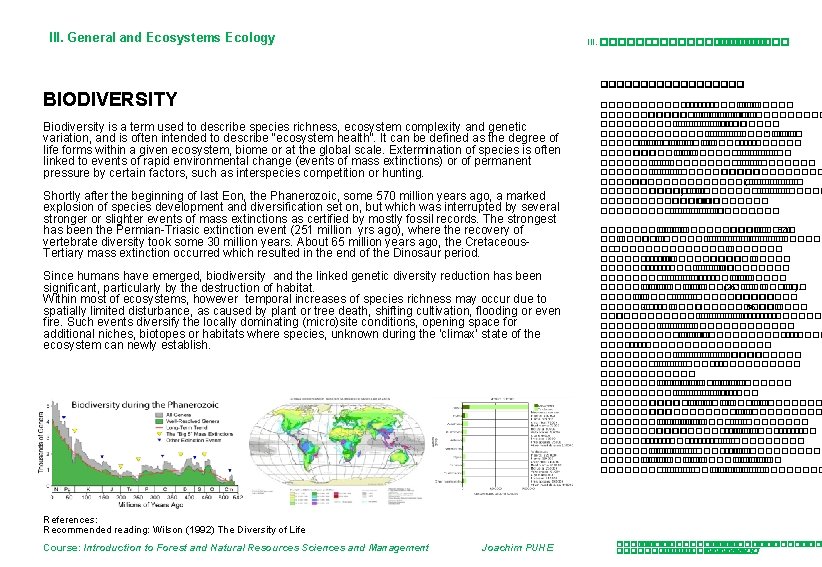

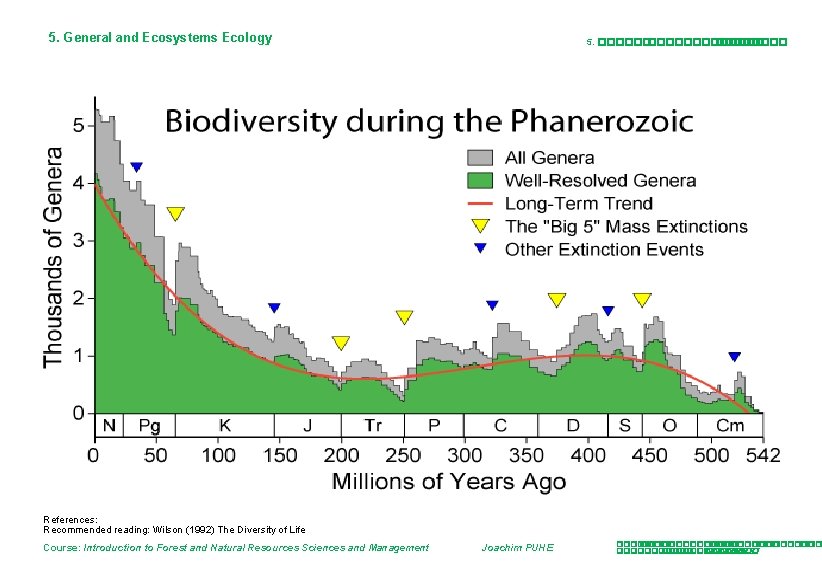

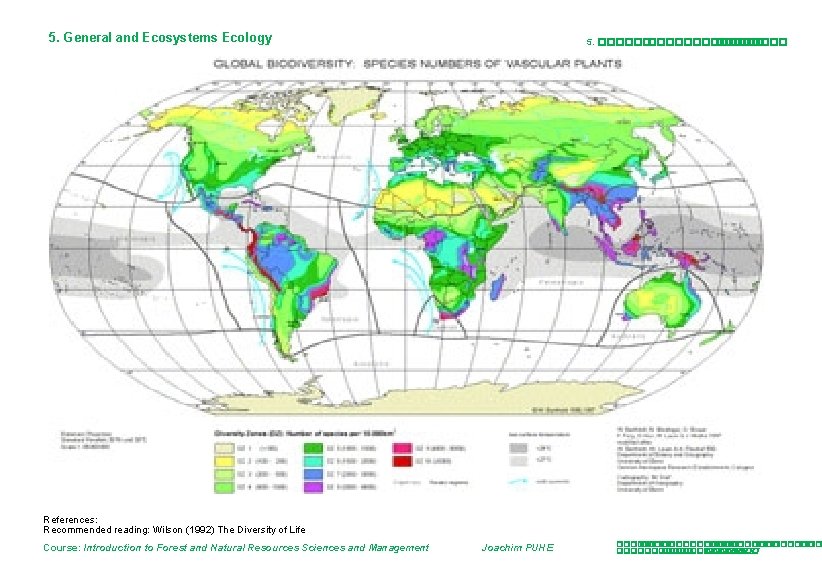

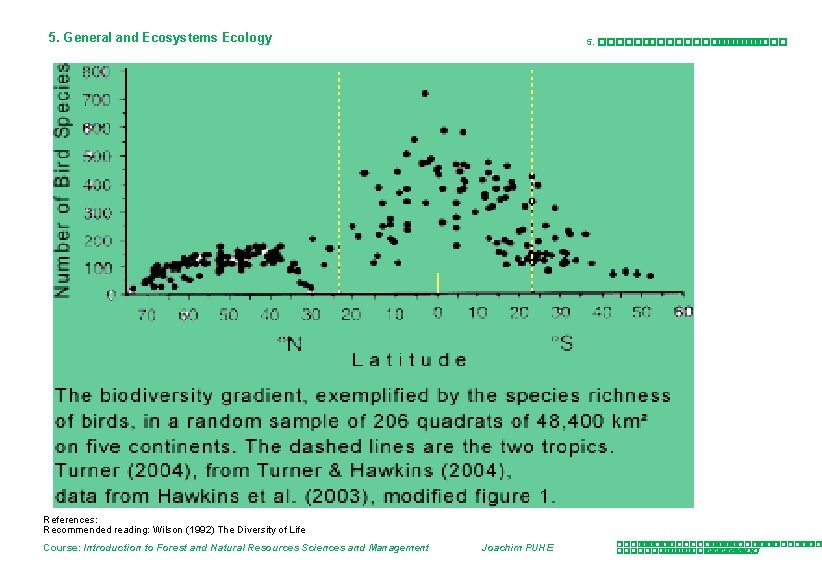

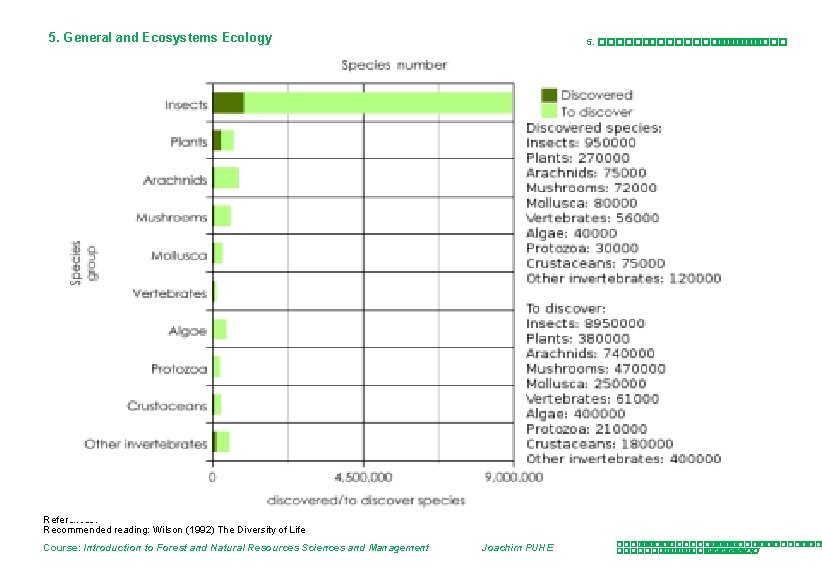

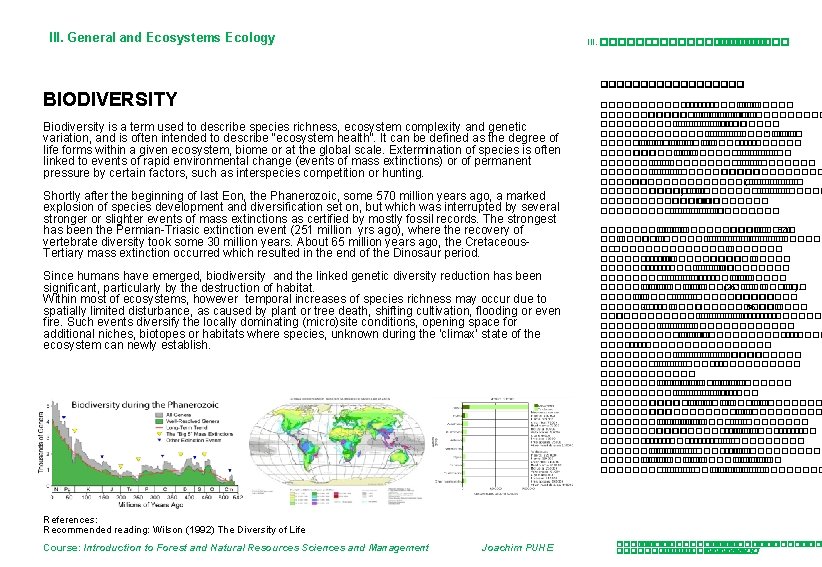

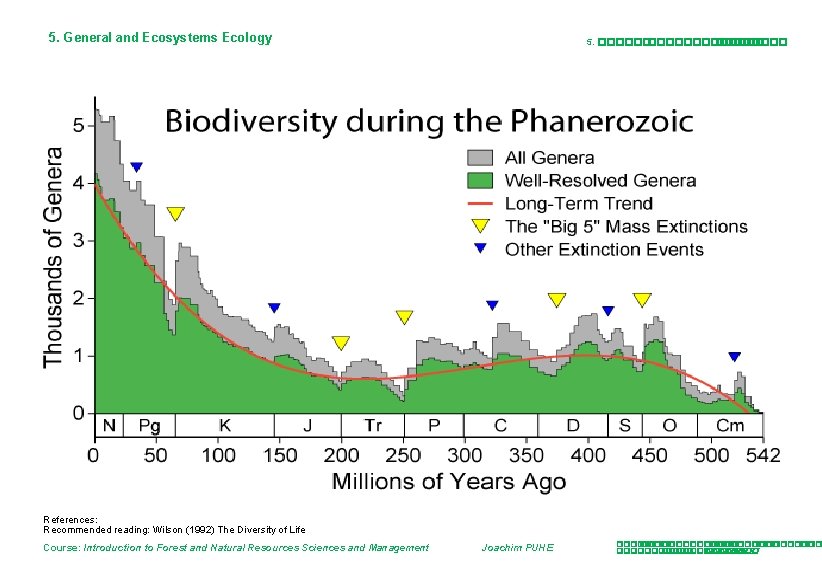

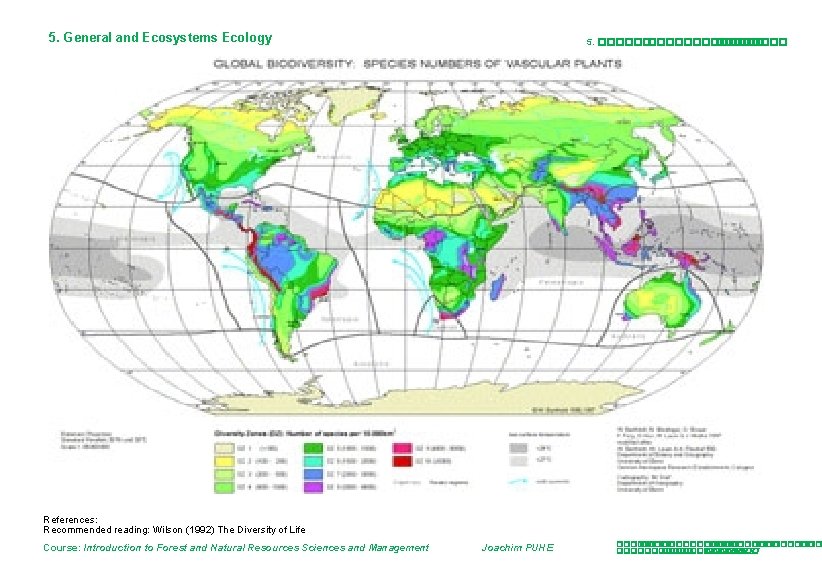

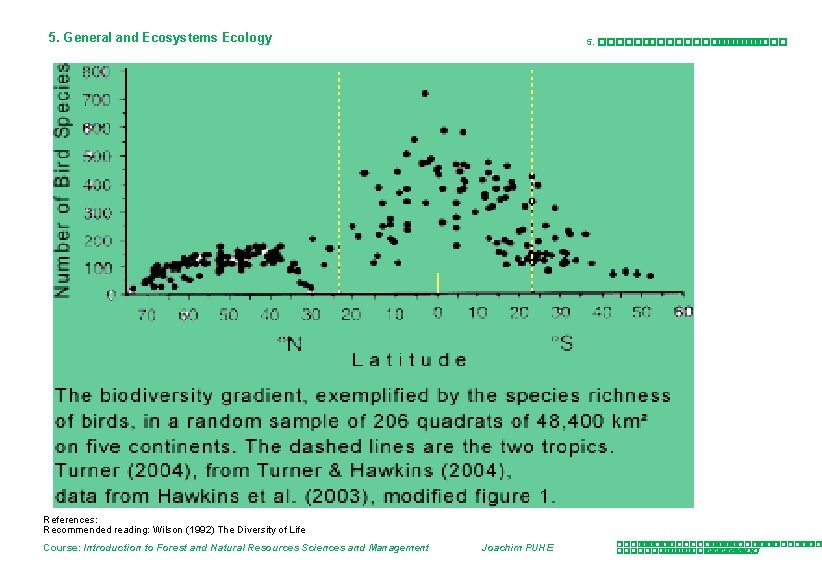

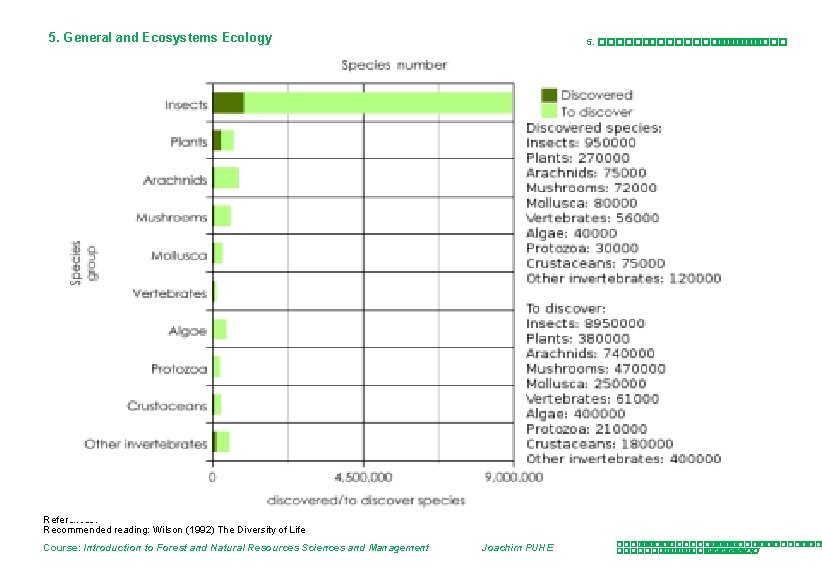

III. General and Ecosystems Ecology III. ������������� BIODIVERSITY Biodiversity is a term used to describe species richness, ecosystem complexity and genetic variation, and is often intended to describe “ecosystem health”. It can be defined as the degree of life forms within a given ecosystem, biome or at the global scale. Extermination of species is often linked to events of rapid environmental change (events of mass extinctions) or of permanent pressure by certain factors, such as interspecies competition or hunting. Shortly after the beginning of last Eon, the Phanerozoic, some 570 million years ago, a marked explosion of species development and diversification set on, but which was interrupted by several stronger or slighter events of mass extinctions as certified by mostly fossil records. The strongest has been the Permian-Triasic extinction event (251 million yrs ago), where the recovery of vertebrate diversity took some 30 million years. About 65 million years ago, the Cretaceous. Tertiary mass extinction occurred which resulted in the end of the Dinosaur period. Since humans have emerged, biodiversity and the linked genetic diversity reduction has been significant, particularly by the destruction of habitat. Within most of ecosystems, however temporal increases of species richness may occur due to spatially limited disturbance, as caused by plant or tree death, shifting cultivation, flooding or even fire. Such events diversify the locally dominating (micro)site conditions, opening space for additional niches, biotopes or habitats where species, unknown during the ‘climax’ state of the ecosystem can newly establish. ��������� ����������� , ������������� ����� , ������������ “������ ”. �������� �������� ������� , ������� �� ����������� ����������� ������������ (������� ) �� ��������������� , ��������� ����������. ����������� , 570 ���� ��� , ������������� ������� , ��������� ������ �� ��������� , ��������� ������� ��� �������� (251 ���� ��� ), �������� �������� 30 ����� 65 ��� ���������� ������������� , �������� �� ������������� ��������� ������� , ���������������� ������ ��������� , ����������� �� �������� , ������� �� ��������� ���������� , ����� �� ����� , ����������� ������ ����������. References: Recommended reading: Wilson (1992) The Diversity of Life Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

5. General and Ecosystems Ecology 5. ����������� References: Recommended reading: Wilson (1992) The Diversity of Life Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

5. General and Ecosystems Ecology 5. ����������� References: Recommended reading: Wilson (1992) The Diversity of Life Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

5. General and Ecosystems Ecology 5. ����������� References: Recommended reading: Wilson (1992) The Diversity of Life Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

5. General and Ecosystems Ecology 5. ����������� References: Recommended reading: Wilson (1992) The Diversity of Life Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

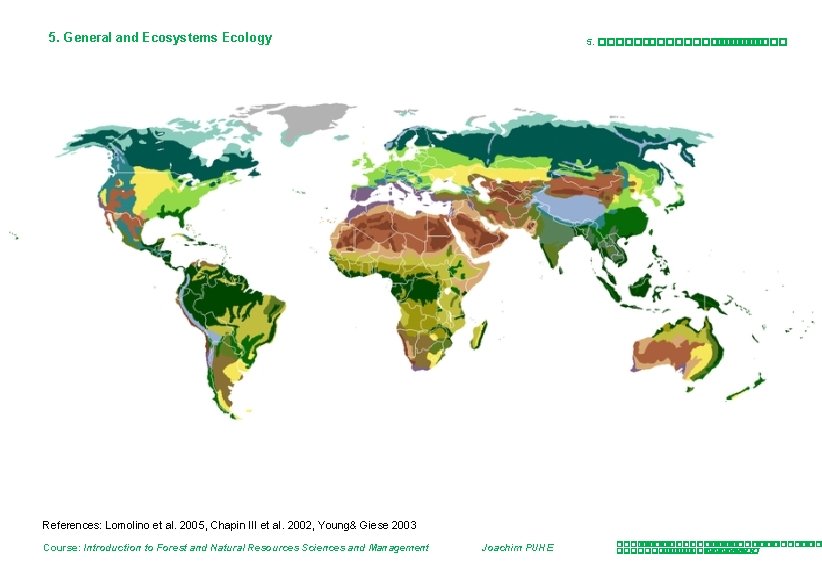

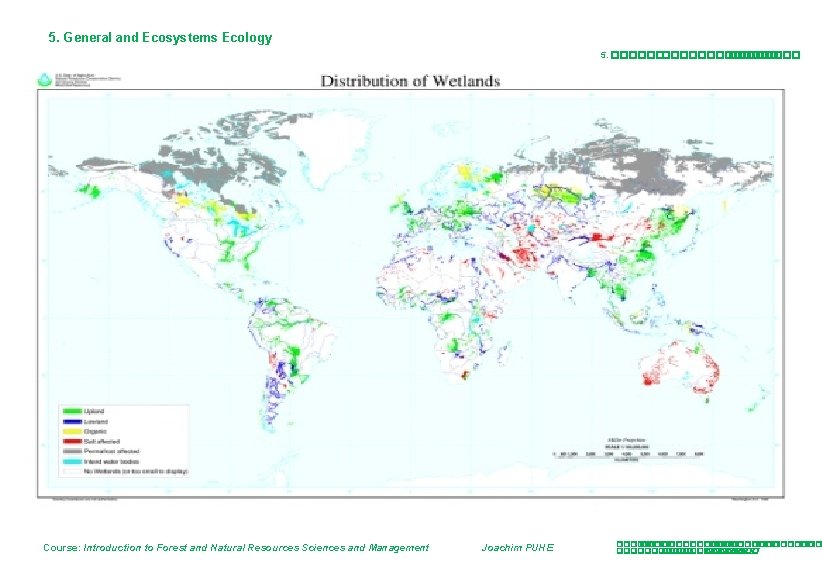

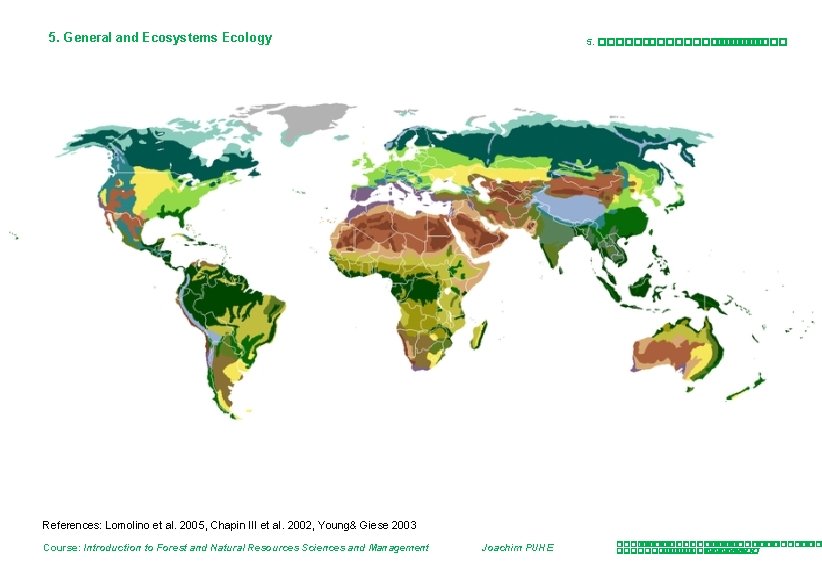

5. General and Ecosystems Ecology 5. ����������� References: Lomolino et al. 2005, Chapin III et al. 2002, Young& Giese 2003 Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

5. General and Ecosystems Ecology 5. ����������� Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

5. General and Ecosystems Ecology 5. ����������� Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������

5. General and Ecosystems Ecology Course: Introduction to Forest and Natural Resources Sciences and Management 5. ����������� Joachim PUHE ����� : ����������� �� ����������