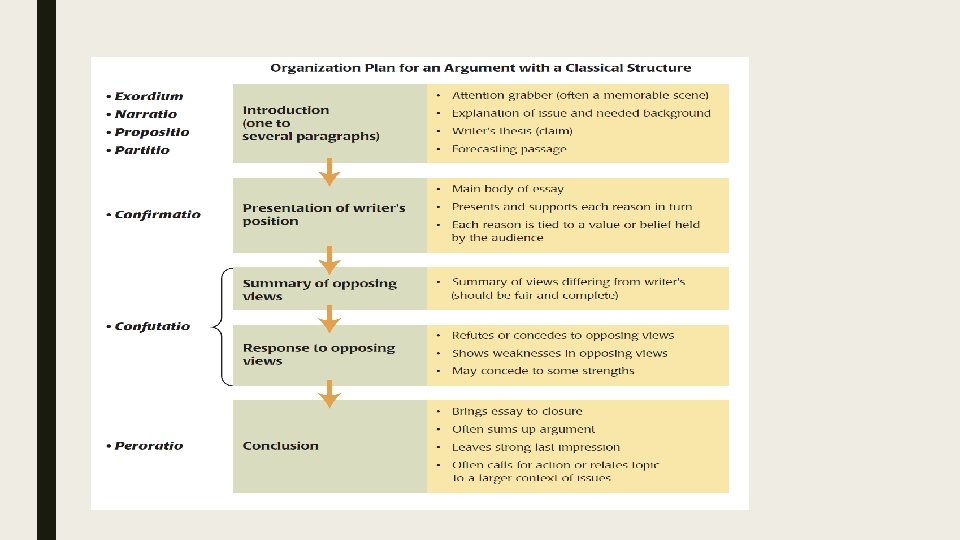

CORE OF AN ARGUMENT Classical Structure of Argument

- Slides: 30

CORE OF AN ARGUMENT

Classical Structure of Argument

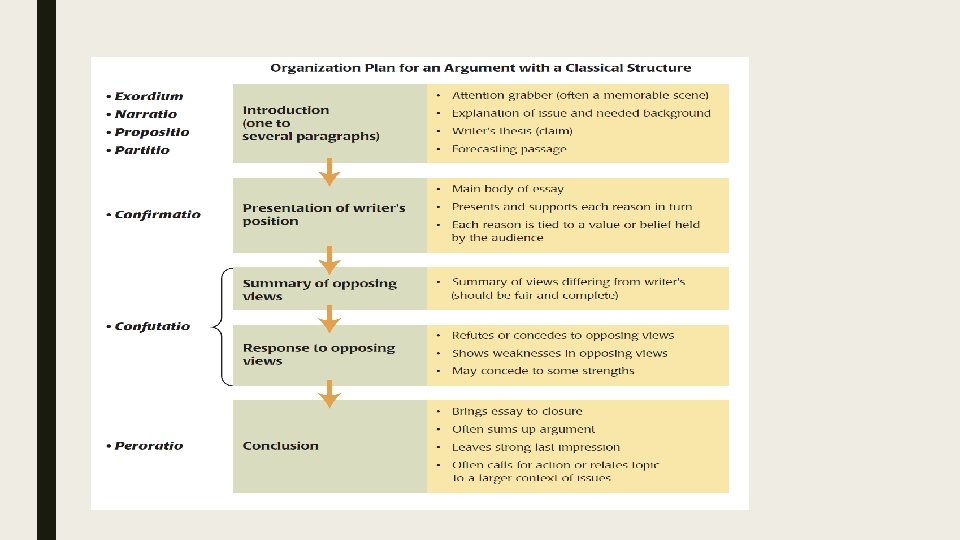

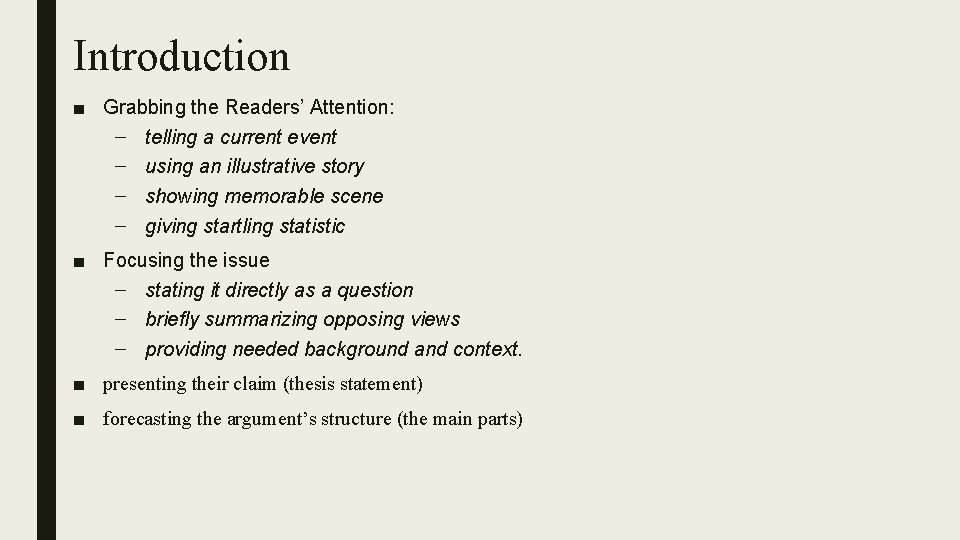

Introduction ■ Grabbing the Readers’ Attention: – telling a current event – using an illustrative story – showing memorable scene – giving startling statistic ■ Focusing the issue – stating it directly as a question – briefly summarizing opposing views – providing needed background and context. ■ presenting their claim (thesis statement) ■ forecasting the argument’s structure (the main parts)

Presentation of the Writer’s Position ■ The longest part of a classical argument. ■ Reasons and evidence that support their claims are presented ■ The reason and evidence: – related to the audience’s values, beliefs, and assumptions – each developed in its own paragraph or sequence of paragraphs – When a paragraph introduces a new reason, it is stated directly and then supported with evidence or a chain of ideas ■ Appropriate transitions are used throughout

Summary and Critique of Alternative Views ■ There are several options to write opposing views: ■ If there are several opposing arguments, – All of them may be summarized together and composed into a single response – or – Each argument may be summarized and responded in turn. ■ Opposing views may be refuted or their strengths may be accepted by shifting to a different field of values.

Conclusion ■ Argument is summed up – Claims are restated – Some kind of action can be called for ■ A sense of closure is created and a strong final impression is left.

The main sections of a classical argument ■ Two major sections – presenting the writer’s own position – summarizing and responding to alternative views ■ In general writer’s own position comes first, but it is possible to reverse that order.

Persuasiveness of classical argument ■ An argument with a classical structure may not always be the most persuasive strategy. ■ you may be more effective by – delaying your thesis, – ignoring alternative views altogether, or – showing great sympathy for opposing views ■ However, the classical structure is a useful planning tool. – Intro presents the whole of your argument in miniature. – Summary and opposing views alerts you to the limits of your position and to the need for further reasons and evidence.

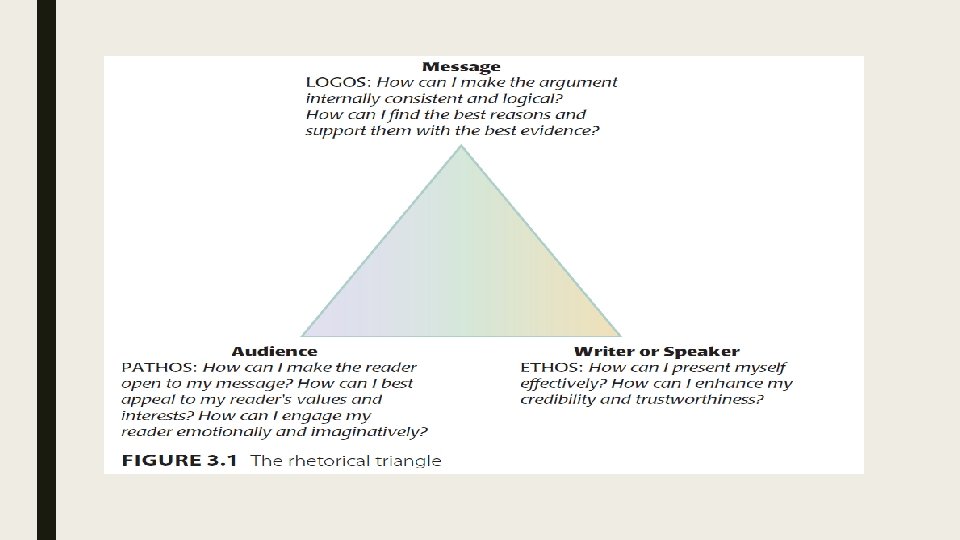

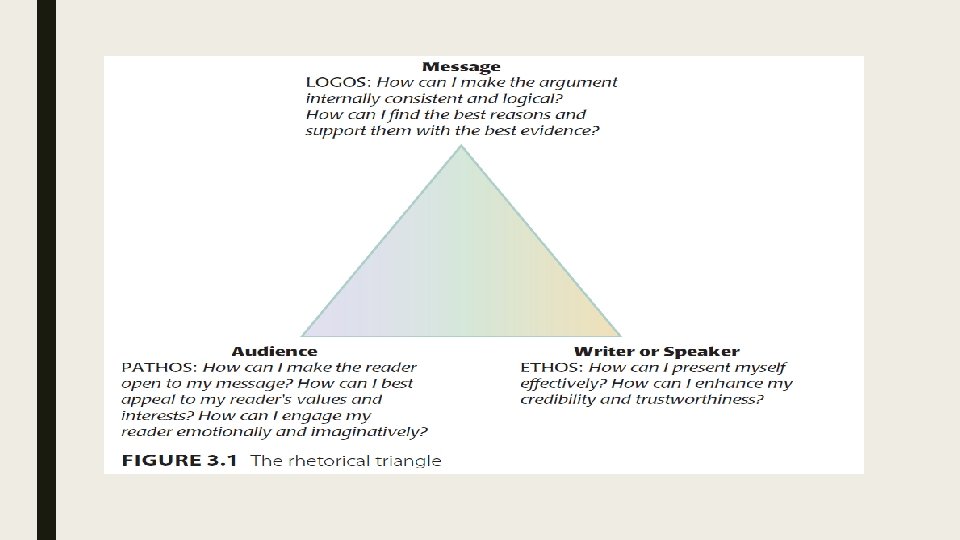

The Rhetorical Triangle ■ Persuasive speeches are analyzed considering three appeals: – logos (MESSAGE) – ethos (WRITER/SPEAKER) – pathos (AUDIENCE)

LOGOS (Greek for “word”) ■ attention is on the quality of the message— – internal consistency, – the clarity of the argument, and – the logic of its reasons ■ Its impact on the audience is called as LOGICAL APPEAL

ETHOS (Greek for “character”) ■ Attention is on the writer’s / speaker’s character: Credibility of the writer – – Fairness while considering alternative views Tone and style Professional appearance (including grammar, citations, etc) Honesty ■ Its impact on the audience is ETHICAL APPEAL (APPEAL FROM CREDIBILITY)

PATHOS (Greek for “suffering” or “experience”) ■ Attention is on the values and beliefs of attended audience ■ Associated with emotional appeal ■ More specifically attracts an audience’s imaginative sympathies (their capacities to feel and see what the writer feels and sees) ■ In sum, ‘whereas appeals to logos and ethos can further an audience’s intellectual assent to our claim, appeals to pathos engage the imagination and feelings, moving the audience to a deeper appreciation of the argument’s signigicance’

■ What are we doing then? – Making a pathetic appeal by abstracting logical discourse into a tangible and immediate story ■ Appeals to logos and ethos can help an audience’s intellectual agreement with our claim ■ Appeals to pathos can move the audience to a deeper appreciation of the argument’s significance

A related Word: KAIROS (Greek word for “right time, ” “season, ” or “opportunity”) ■ How to make persuasive argument: – its timing must be effectively chosen – its tone and structure must be in right proportion or measure. ■ You may ask such questions before sending an argumentative e-mail: – Is this the right moment to send this message? – Is my audience ready to hear what I’m saying? – Would my argument be more effective if I waited for a couple of days? – If I send this message now, should I change its tone and content? ■ This attentiveness to the unfolding of time is what is meant by kairos.

Issue vs Information Questions ■ Issue questions: can be answered reasonably in two or more differing ways ■ Information questions: can be answered in one way ■ E. g. How does adult literacy rate in Turkey compare with the rate in Germany? If the rates are different, why?

Issue vs Information Questions ■ Issue questions: can be answered reasonable in two or more differing ways ■ Information questions: can be answered in one way ■ E. g. How does adult literacy rate in Turkey compare with the rate in Germany? If the rates are different, why? Information question

Issue vs Information Questions ■ Issue questions: can be answered reasonable in two or more differing ways ■ Information questions: can be answered in one way ■ E. g. How does adult literacy rate in Turkey compare with the rate in Germany? If the rates are different, why? Issue question

■ Sometimes the same question can be an information question in one context and an issue question in another ■ E. gs ■ How does a diesel engine work? – info question—anyone who knows about diesel engines would agree on how it Works (maybe asked by new learners) ■ Why is a diesel engine more fuel efficient than a gasoline engine? – info question—anyone who knows about diesel engines would agree on how it Works (maybe asked by new learners)

■ What is the most cost-effective way to produce diesel fuel from crude oil? – Info if experts agree and new learners are addressed – Issue if experts are addressed and they have differing ideas ■ Should the present highway tax on diesel fuel be increased? – Issue question—everyone may have different ideas

■ Go to p. 4 Class Discussion-1 ■ Discuss if the following are info or issue or either type of question. If you say could be either, create hypothetical contexts to show your reasoning. ■ 1. What percentage of public schools in the USA are failing? ■ 2. Which causes more traffic accidents, drunk driving or texting while driving? ■ 3. What is the effect on children of playing first-person-shooter games? ■ 4. Is genetically modified corn safe for human consumption? ■ 5. Should people get rid of their land lines and have only cell phones?

Genuine vs. Pseudo Argument ■ Every argument has an issue question with alternative answers ■ However, not every argument is rational / genuine. ■ Rational (Genuine) arguments require two additional factors: – reasonable participants who operate within the conventions of reasonable behavior – potentially sharable assumptions that can serve as a starting place or foundation for the argument. ■ Lacking one or both of these conditions, disagreements remain stalled at the level of pseudo-arguments.

Pseudo-Arguments ■ In a reasonable argument – there is the possibility of growth and change – disputants may modify their views (accepting strengths in an alternative view or weaknesses in their own) ■ In a pseudo-argument – such growth becomes impossible – argument degenerates to pseudo-argument (this happens when disputants are fanatically committed to their positions)

Committed (Fanatical) Believers and Fanatical Skeptics ■ Committed Believers – are admirable persons, – are guided by solid values and beliefs. – are unwilling to compromise their principles ■ But at the same time they – are rigidly fixed, incapable of growth or change ■ In case of a dialogue between committed believers, – they talk past each other – dialogue is replaced by monologue – each disputant endlessly uses the same prepackaged arguments. ■ Disagreeing with a committed believer is like ordering the surf to quiet down.

■ Fanatical Skeptics – dismiss the possibility of ever believing anything – often demand proof where no proof is possible ■ So what if the sun has risen every day of recorded history? That’s no proof that it will rise tomorrow. – accept nothing that does not have absolute proof, which may never exist – demand a logical demonstration of our claim’s rightness.

A Closer Look at Pseudo-Arguments: The Lack of Shared Assumptions ■ Rational argument degenerates to pseudo-argument when there is no possibility for – listening, – learning, – growth, – change. ■ What is the main cause of pseudo-arguments? – Lack of shared assumptions.

Shared Assumptions and the Problem of Ideology: ■ Reasonable argument is difficult when the disputants have differing “ideologies, ” (an academic word for belief systems or worldviews) ■ We all have our own ideologies shaped by our life’s experiences: – family background, our friends, our culture, – our particular time in history, – our race or ethnicity, our gender, – our social class, our religion, – our education, etc. ■ To participate in rational argument, we and our audience must seek shared assumptions

■ The failure to find shared assumptions often leads to pseudo-arguments, particularly if one disputant makes assumptions that the other disputant cannot accept. – Such pseudo-arguments often occur in disputes arising from politics or religion. ■ Mostly because… – certain religious or political beliefs or texts cannot be evoked for evidence or authority

Shared Assumptions and the Problem of Personal Opinions: ■ Lack of shared assumptions are also caused by purely personal opinions ■ E. g. – Claiming that pizza is better than nachos ■ Genuine argument (shared assumption) might be possible only if the disputants assume a shared criterion about nutrition ■ Pseudo argument if one of the disputants responds, “Nah, nachos are better than pizza because nachos taste better, ” ■ This is a wholly personal standard, an assumption that others are unable to share.