Coping With Intimate Partner Violence Dependent Victims Downplay

- Slides: 1

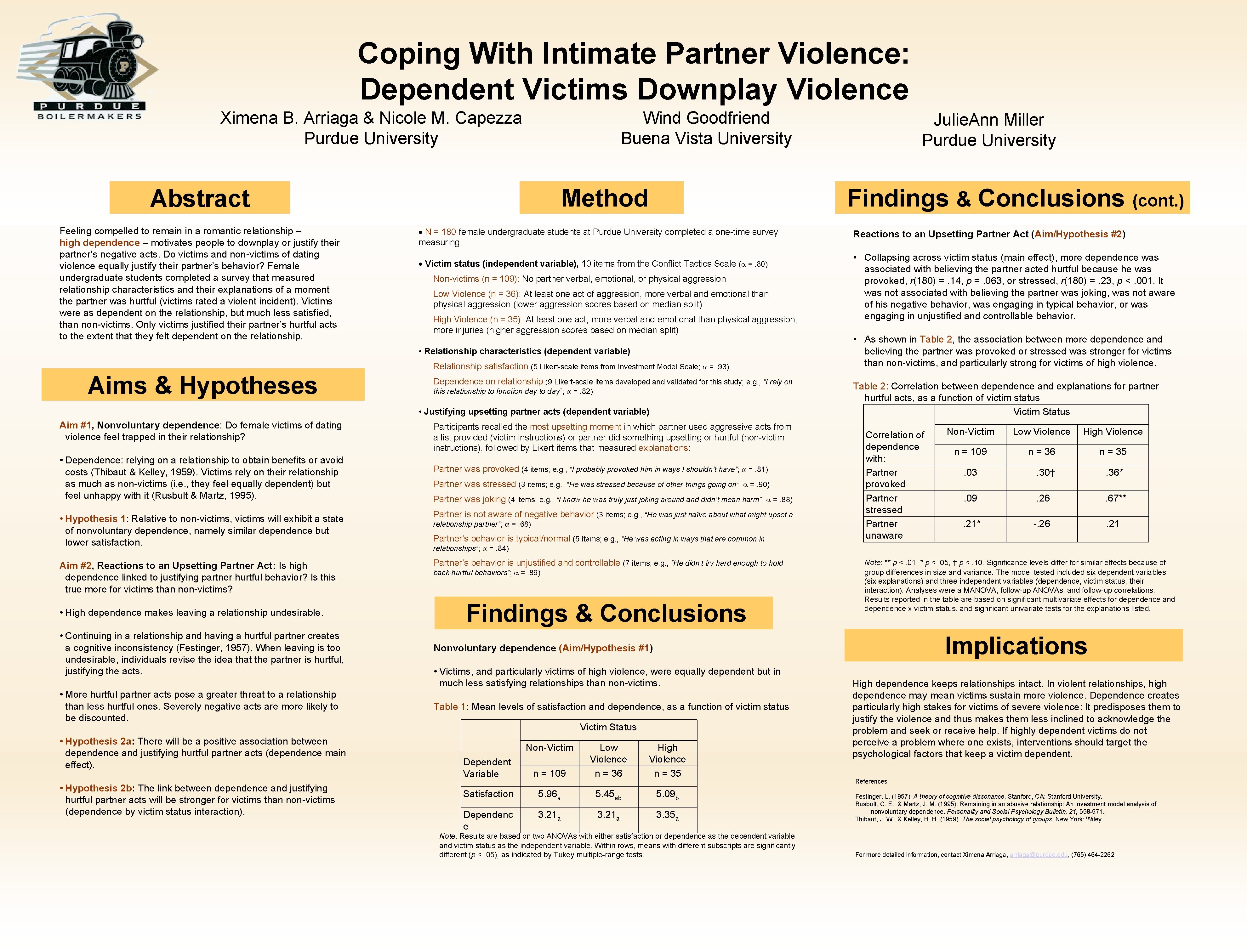

Coping With Intimate Partner Violence: Dependent Victims Downplay Violence Ximena B. Arriaga & Nicole M. Capezza Purdue University Wind Goodfriend Buena Vista University Method Abstract Feeling compelled to remain in a romantic relationship – high dependence – motivates people to downplay or justify their partner’s negative acts. Do victims and non-victims of dating violence equally justify their partner’s behavior? Female undergraduate students completed a survey that measured relationship characteristics and their explanations of a moment the partner was hurtful (victims rated a violent incident). Victims were as dependent on the relationship, but much less satisfied, than non-victims. Only victims justified their partner’s hurtful acts to the extent that they felt dependent on the relationship. Findings & Conclusions (cont. ) N = 180 female undergraduate students at Purdue University completed a one-time survey measuring: Victim status (independent variable), 10 items from the Conflict Tactics Scale ( =. 80) Non-victims (n = 109): No partner verbal, emotional, or physical aggression Low Violence (n = 36): At least one act of aggression, more verbal and emotional than physical aggression (lower aggression scores based on median split) High Violence (n = 35): At least one act, more verbal and emotional than physical aggression, more injuries (higher aggression scores based on median split) • Relationship characteristics (dependent variable) Relationship satisfaction (5 Likert-scale items from Investment Model Scale; =. 93) Aims & Hypotheses Dependence on relationship (9 Likert-scale items developed and validated for this study; e. g. , “I rely on this relationship to function day to day”; =. 82) • Justifying upsetting partner acts (dependent variable) Aim #1, Nonvoluntary dependence: Do female victims of dating violence feel trapped in their relationship? • Dependence: relying on a relationship to obtain benefits or avoid costs (Thibaut & Kelley, 1959). Victims rely on their relationship as much as non-victims (i. e. , they feel equally dependent) but feel unhappy with it (Rusbult & Martz, 1995). Participants recalled the most upsetting moment in which partner used aggressive acts from a list provided (victim instructions) or partner did something upsetting or hurtful (non-victim instructions), followed by Likert items that measured explanations: Partner was provoked (4 items; e. g. , “I probably provoked him in ways I shouldn’t have”; =. 81) Partner was stressed (3 items; e. g. , “He was stressed because of other things going on”; =. 90) Partner was joking (4 items; e. g. , “I know he was truly just joking around and didn’t mean harm”; =. 88) • Hypothesis 1: Relative to non-victims, victims will exhibit a state of nonvoluntary dependence, namely similar dependence but lower satisfaction. Partner is not aware of negative behavior (3 items; e. g. , “He was just naïve about what might upset a Aim #2, Reactions to an Upsetting Partner Act: Is high dependence linked to justifying partner hurtful behavior? Is this true more for victims than non-victims? Partner’s behavior is unjustified and controllable (7 items; e. g. , “He didn’t try hard enough to hold • High dependence makes leaving a relationship undesirable. • Continuing in a relationship and having a hurtful partner creates a cognitive inconsistency (Festinger, 1957). When leaving is too undesirable, individuals revise the idea that the partner is hurtful, justifying the acts. • More hurtful partner acts pose a greater threat to a relationship than less hurtful ones. Severely negative acts are more likely to be discounted. • Hypothesis 2 a: There will be a positive association between dependence and justifying hurtful partner acts (dependence main effect). • Hypothesis 2 b: The link between dependence and justifying hurtful partner acts will be stronger for victims than non-victims (dependence by victim status interaction). Julie. Ann Miller Purdue University relationship partner”; =. 68) Partner’s behavior is typical/normal (5 items; e. g. , “He was acting in ways that are common in Reactions to an Upsetting Partner Act (Aim/Hypothesis #2) • Collapsing across victim status (main effect), more dependence was associated with believing the partner acted hurtful because he was provoked, r(180) =. 14, p =. 063, or stressed, r(180) =. 23, p <. 001. It was not associated with believing the partner was joking, was not aware of his negative behavior, was engaging in typical behavior, or was engaging in unjustified and controllable behavior. • As shown in Table 2, the association between more dependence and believing the partner was provoked or stressed was stronger for victims than non-victims, and particularly strong for victims of high violence. Table 2: Correlation between dependence and explanations for partner hurtful acts, as a function of victim status Victim Status Correlation of dependence with: Partner provoked Partner stressed Partner unaware Non-Victim Low Violence High Violence n = 109 n = 36 n = 35 . 03 . 30† . 36* . 09 . 26 . 67** . 21* -. 26 . 21 relationships”; =. 84) back hurtful behaviors”; =. 89) Findings & Conclusions Note: ** p <. 01, * p <. 05, † p <. 10. Significance levels differ for similar effects because of group differences in size and variance. The model tested included six dependent variables (six explanations) and three independent variables (dependence, victim status, their interaction). Analyses were a MANOVA, follow-up ANOVAs, and follow-up correlations. Results reported in the table are based on significant multivariate effects for dependence and dependence x victim status, and significant univariate tests for the explanations listed. Implications Nonvoluntary dependence (Aim/Hypothesis #1) • Victims, and particularly victims of high violence, were equally dependent but in much less satisfying relationships than non-victims. Table 1: Mean levels of satisfaction and dependence, as a function of victim status Victim Status Non-Victim Dependent Variable n = 109 Low Violence n = 36 High Violence n = 35 Satisfaction 5. 96 a 5. 45 ab 5. 09 b Dependenc e 3. 21 a 3. 35 a Note. Results are based on two ANOVAs with either satisfaction or dependence as the dependent variable and victim status as the independent variable. Within rows, means with different subscripts are significantly different (p <. 05), as indicated by Tukey multiple-range tests. High dependence keeps relationships intact. In violent relationships, high dependence may mean victims sustain more violence. Dependence creates particularly high stakes for victims of severe violence: It predisposes them to justify the violence and thus makes them less inclined to acknowledge the problem and seek or receive help. If highly dependent victims do not perceive a problem where one exists, interventions should target the psychological factors that keep a victim dependent. References Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University. Rusbult, C. E. , & Martz, J. M. (1995). Remaining in an abusive relationship: An investment model analysis of nonvoluntary dependence. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 558 -571. Thibaut, J. W. , & Kelley, H. H. (1959). The social psychology of groups. New York: Wiley. Discussion For more detailed information, contact Ximena Arriaga, arriaga@purdue. edu, (765) 464 -2262