Contingency Reserves for the Changing Bulk Power System

Contingency Reserves for the Changing Bulk Power System Timothy Li August 2019

1. Road Map The generation mix is changing. 2. Contingency reserves requirements are calculated based on the most severe single contingency (MSSC) per BAL-002 -2. 3. Higher levels of renewable energy can/will change the way we operate under the MSSC protocol and make alternatives to the MSSC rule more feasible.

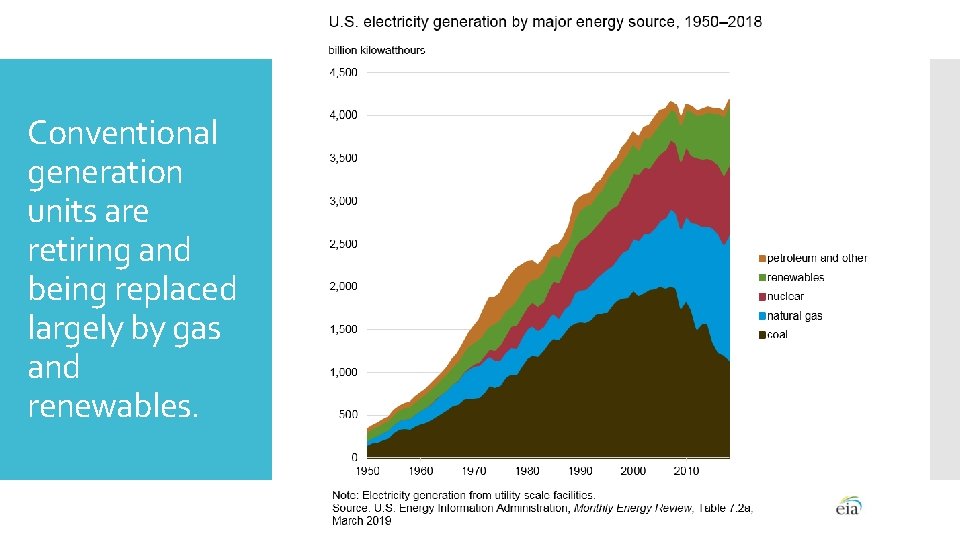

Conventional generation units are retiring and being replaced largely by gas and renewables.

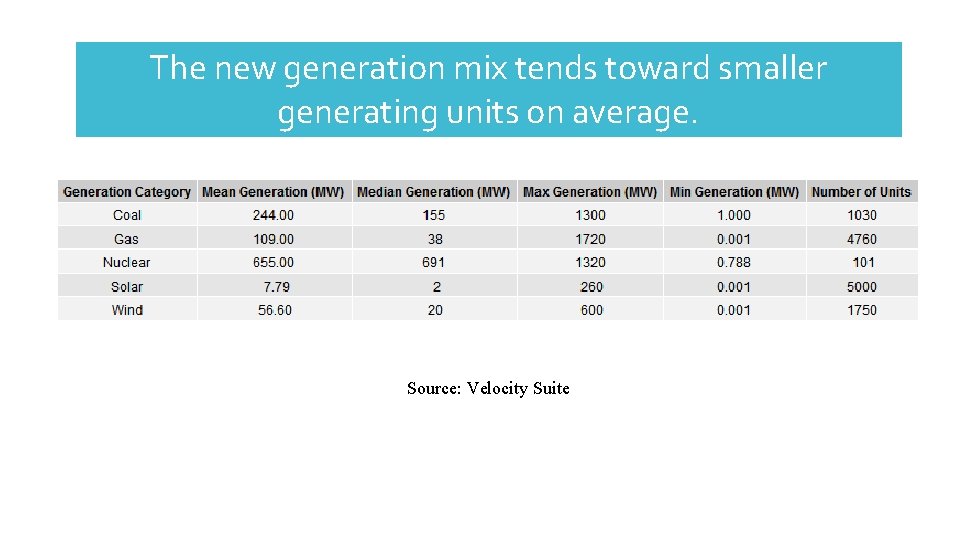

The new generation mix tends toward smaller generating units on average. Source: Velocity Suite

BAL-002 -2 – Contingency reserves must be at least the greater of either: Contingency reserves are currently calculated using MSSC. Loss of the most severe single contingency Sum of 3% of both hourly integrated load and hourly integrated generation Reserve Sharing Groups or Balancing Authorities (in absence of RSG) responsible for holding contingency reserves. Ex: Southwest Reserve Sharing Group (24, 779 MW generation capacity) or Tennessee Valley Authority (35, 000 MW) Minimum amount required except within first sixty minutes following an event using those reserves The MSSC (or N-1, for the largest contingency the bulk power system can withstand without load shedding) protocol is a deterministic rule.

In the short term, reserve requirements can begin incorporating probabilistic methods. A probabilistic (or stochastic) model would take into account the relative probabilities of generator outages, forecasting errors, etc. on a day-ahead basis to determine what quantity of contingency reserves to hold. Ruiz (2009) study of Public Service of Colorado system Used Monte Carlo simulations to evaluate how different deterministic frameworks supplemented with stochastic models could increase economic and operating efficiency by managing the uncertainty of wind plants. Though small, operating costs were reduced due to lower reserve requirements in all 10 stochastic simulations, and standard error was low. More significantly, stochastic policies combined with deterministic requirements reduced wind curtailments relative to purely deterministic rules by taking wind and load forecasting and potential upward ramping in wind power into account. These results suggest that it would be advantageous, especially at higher penetrations of wind energy, to incorporate generating uncertainty into calculations of reserve requirements rather than strictly applying MSSC.

Longer term changes to the BPS could include other factors that may affect reserve requirements. Guerrero-Mestre (2018) explores how advancements in energy storage systems (ESS) can enable the transition to probabilistic reserve requirements. Jorgenson (2017) studies how expanded transmission will affect reserve deliverability at the local level. Motalleb (2016) proposes expanding demand response programs to include a reserve product.

Advancements in storage can reduce the variance of probabilistic unitcommitment models and help smooth the transition away from N-1. Guerrero-Mestre (2018) evaluates a probabilistic securityconstrained unit commitment model (PSCUC) in comparison to the current N – 1 (deterministic unit commitment, or DUC) policy and assesses the ability of energy storage systems to provide contingency reserves. Monte Carlo simulations were run on a modified version of the IEEE One-Area Reliability Test System. In all test scenarios, the PSCUC model outperformed the DUC model by reducing cost at the expense of significantly higher variance. Use of ESS helped to reduce variance relative to the non-ESS case. This indicates both that a stochastic contingency reserve requirement would be advantageous to the current MSSC protocol and that usage of energy storage can help ease the transition, increasing flexibility by replacing ramp-constrained conventional generation units.

Expanded transmission may change the way reserves are supplied. According to NREL, transmission expansion is necessary to minimize renewable curtailment and reduce variability by increasing geographic coverage. Simulations from the same study indicate that the power system can draw on over 35% wind and 12% solar to serve load with no reliability issues with expanded transmission. Expanded transmission can reduce the local reserve requirements by decentralizing and widening the reserve sharing pool (Ela, 2010). In an RSG, each party would be responsible for lower quantities of reserves.

Demand response can allow BA’s and RSG’s to draw on load to provide contingency reserves. As a result of greater renewables penetration, demand response may become necessary to manage frequency variation at the consumer level by either increasing or decreasing consumer loads as needed. This demand response also has the potential to provide contingency reserves. Motalleb (2016) used the IEEE 24 -hour bus model to show using demand response to supply contingency reserves can minimize operating costs and maximize social welfare. Demand response is advantageous for providing ancillary services in systems with higher renewables penetrations due to lower system inertia (Motalleb, 2016). Example: ERCOT has its Load Acting as a Resource (LAAR) program to incentivize consumers to use interruptible load as a means to provide frequency response per BAL-001 -TRE.

1. Potential Next Steps Further assess whether probabilistic policies can supplement deterministic rules and, as a result, consider a change to the BAL-002 -2 standard. 2. Continue to track advancements in energy storage systems technology. 3. Evaluate how proposed transmission expansion will affect reserve sharing pools. 4. Compare different levels of renewables penetration to determine the relative advantages of using demand response to supply reserves.

David Ortiz Thanks Nicole Segal Thanh Luong Rest of OER!

- Slides: 12