Connectionist Approaches to Language Acquisition Kim Plunkett avec

- Slides: 39

Connectionist Approaches to Language Acquisition Kim Plunkett avec Julien Mayor, Jon-Fan Hu and Les Cohen Oxford Baby. Lab and UT, Austin

How to figure out the meaning of words…? • Huge number of possible meanings • Hierarchical level? • Relation between objects? ÞLearning constraints? e. g. whole object, taxonomic, …

The weak ‘taxonomic constraint’ Given a choice between a thematically and a taxonomic related object, language users will favour the taxonomic choice over thematic choice (Markman & Hutchinson 1984)

The strong ‘taxonomic constraint’ « When infants embark upon the process of lexical acquisition, they are initially biased to interpret a word applied to an object as referring to that object and to other members of its kind » (Waxman & Markow 1995)

Important implication of the TC From a single labelling event, infer that every object that belong to the same category is called with the same name – Powerful communication tool – Refer to objects one has never seen

Controversy • Specifically linguistic? • How about the shape bias? • Innate? Learnt? Experimental status is unclear, e. g. Markman & Hutchison ’ 84 do not demonstrate the strong taxonomic constraint

Objectives • We investigate how lexical organisation can use pre-lexical categorisation… • We want to understand the conditions necessary for having good generalisation of labels to object of like kinds (taxonomic constraint)… …within a modelling framework

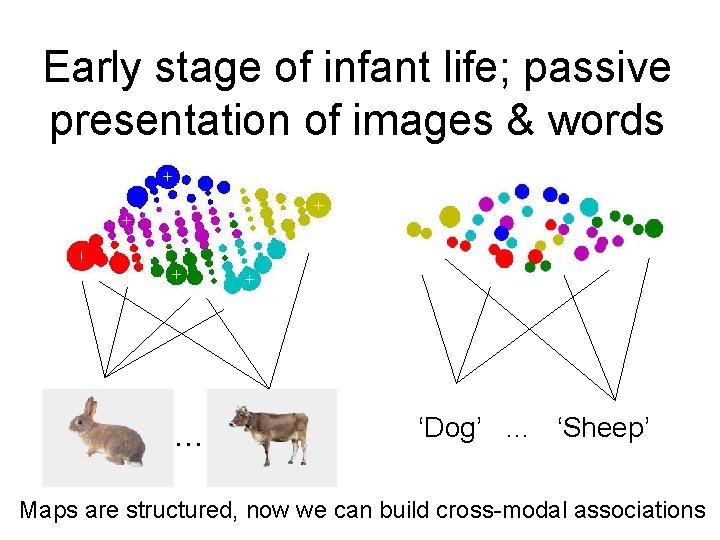

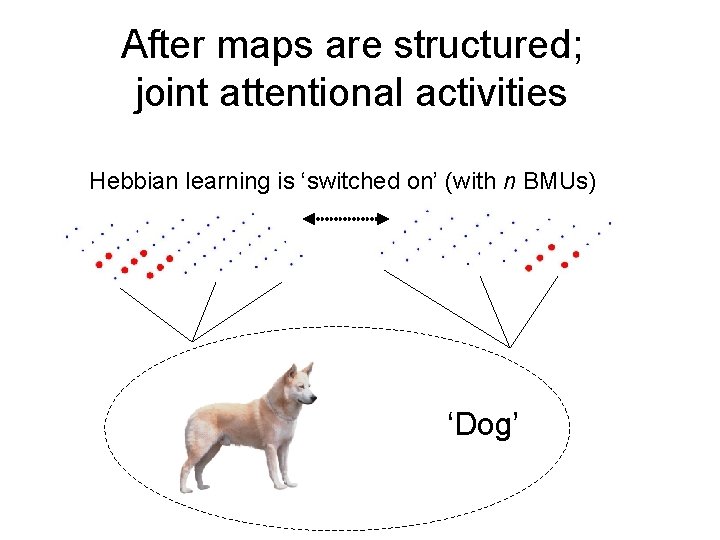

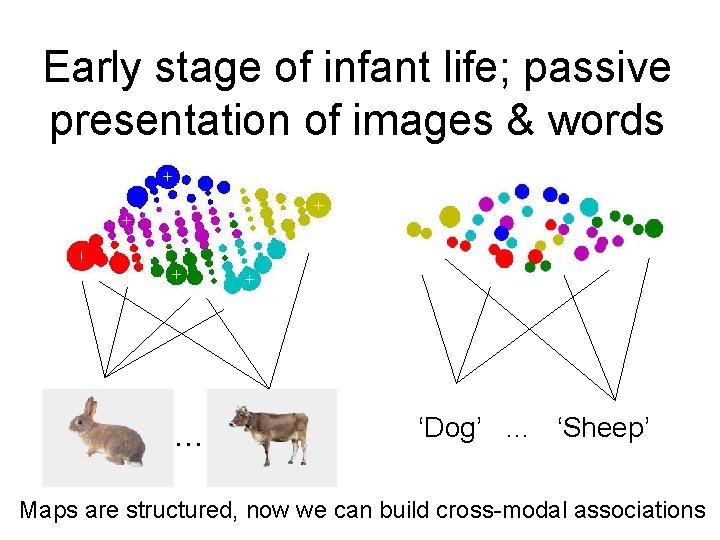

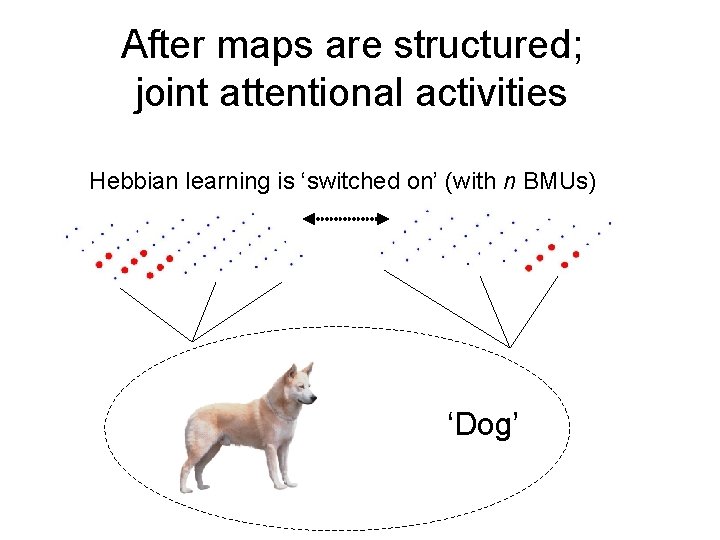

The model Baby • Early infancy; Baby gets experience with visual and acoustic environment • Later infancy, joint attentional activities with care-giver become important: => she gets simultaneous presentations of objects and labels

The model of the model Baby! • Early infancy: unimodal maps (SOMs) receive input from visual and acoustic world (objects and labels) • Later infancy: object and their labels are presented at the same time. Synapses linking active neurones on both maps are reinforced

Speech perception development • Initial sensitivity to speech… – prenatal exposure experiments (Mehler, Fifer & Moon 2003), fetal voice recognition (Kisilevsky 2003) • …to learning of language-specific sound patterns… – forward vs backward speech (Dehaene-Lambertz et al. 2002) • … and word segmentation – at 7 -8 m (Jusczyk & Aslin ‘ 95)

Visual stream development • Basic structure of cortical maps innate but experience essential (Crair & al. 1998) • Contribution of sensory experience to development of orientation selectivity: – Stripped environment, alteration of dist. orientation preference (Blakemore & Cooper 2001) – Environment deprivation (White & al. 2001 )

Modelling the unimodal perceptual development We use Self-Organising Maps (SOMs, Kohonen 1984) – they achieve dimensionality reduction – they self-organise around topological maps – they work in an unsupervised way (ie environment structures the maps) Similar objects are mapped to neighbouring neurons

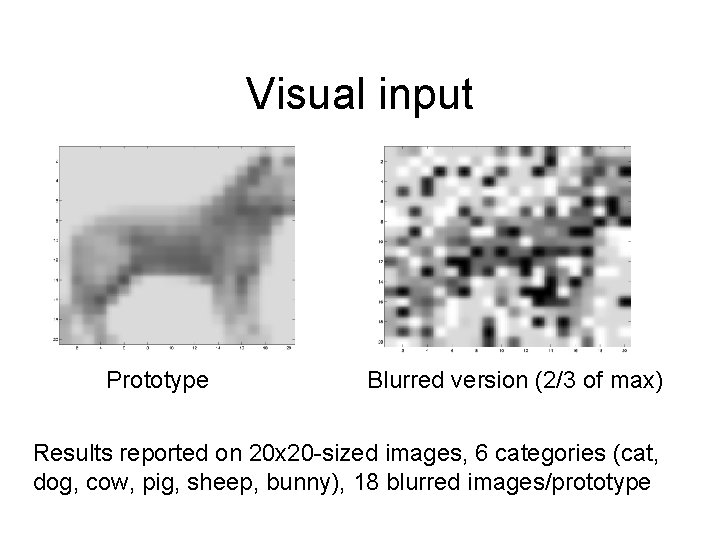

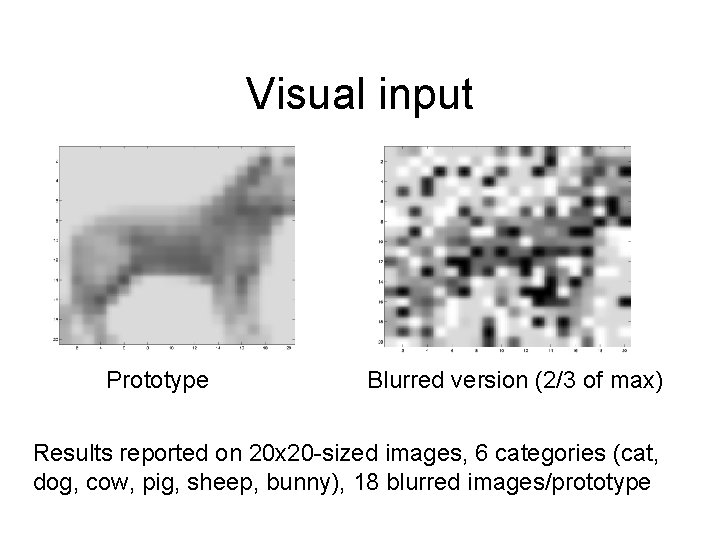

Visual input Prototype Blurred version (2/3 of max) Results reported on 20 x 20 -sized images, 6 categories (cat, dog, cow, pig, sheep, bunny), 18 blurred images/prototype

Early stage of infant life; passive presentation of images & words … ‘Dog’ … ‘Sheep’ Maps are structured, now we can build cross-modal associations

After maps are structured; joint attentional activities Hebbian learning is ‘switched on’ (with n BMUs) ‘Dog’

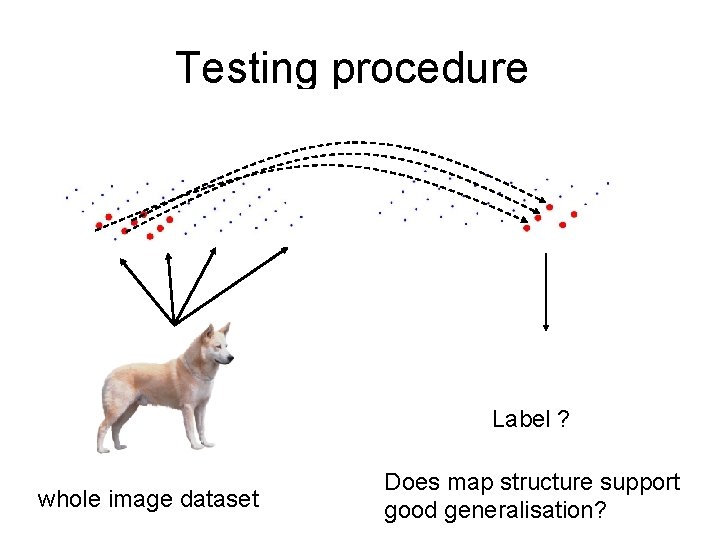

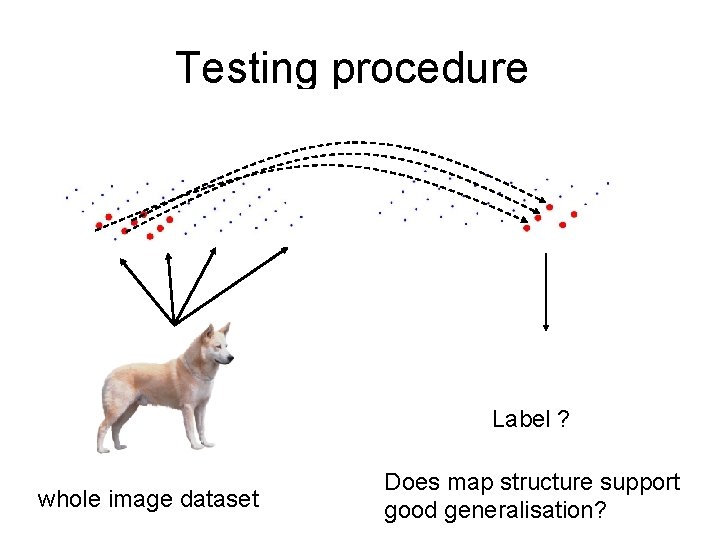

Testing procedure Label ? whole image dataset Does map structure support good generalisation?

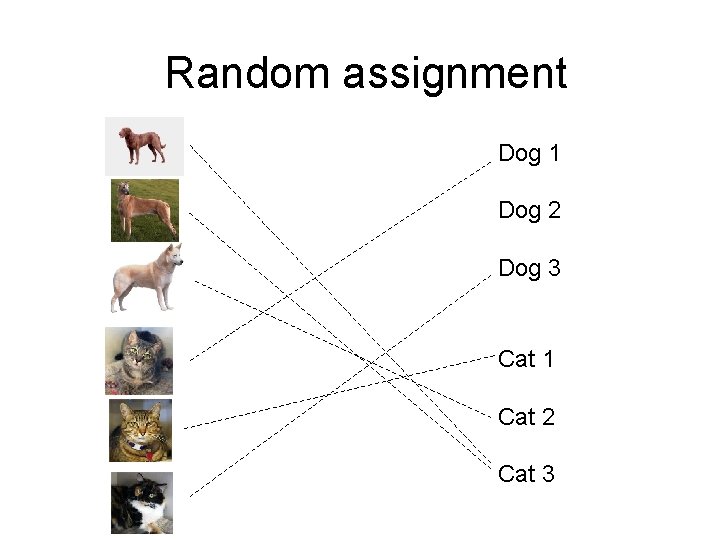

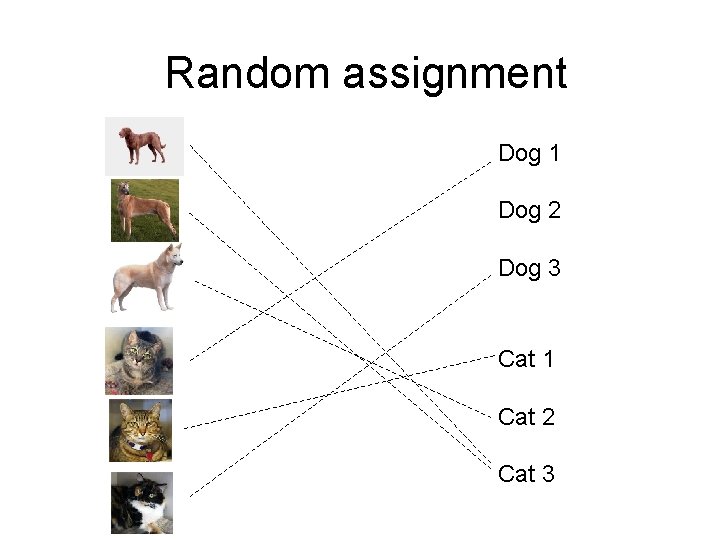

Random assignment Dog 1 Dog 2 Dog 3 Cat 1 Cat 2 Cat 3

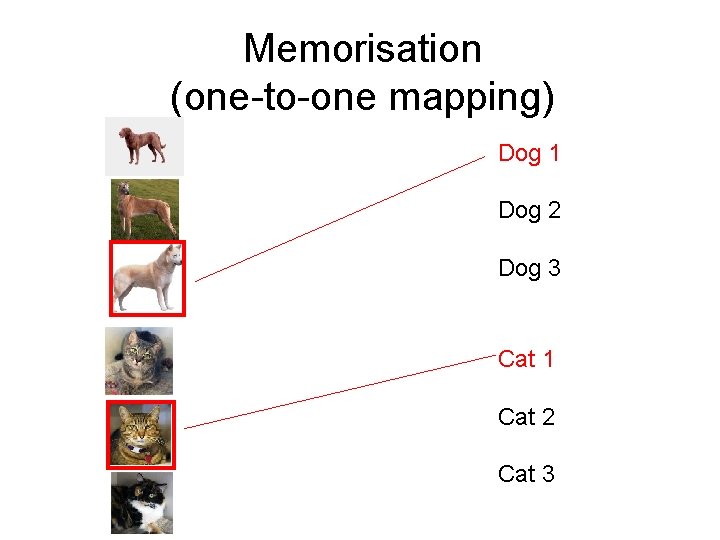

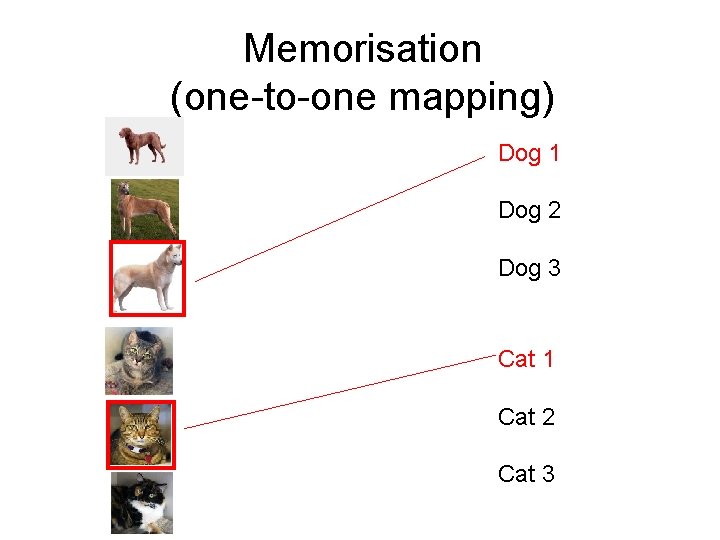

Memorisation (one-to-one mapping) Dog 1 Dog 2 Dog 3 Cat 1 Cat 2 Cat 3

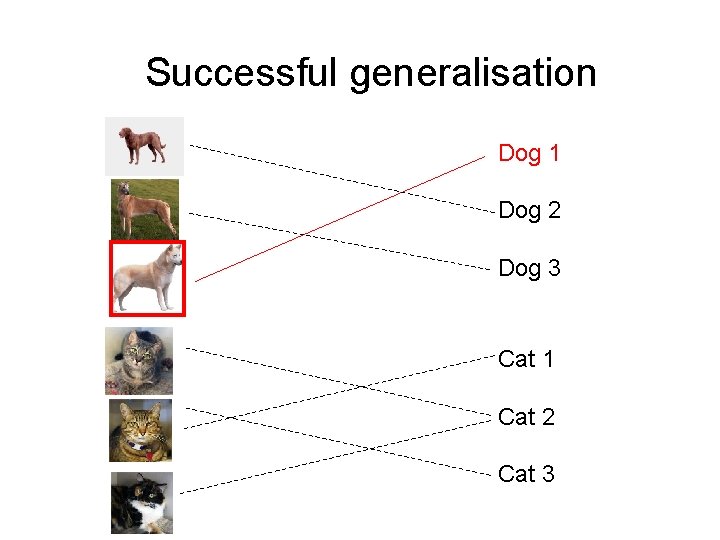

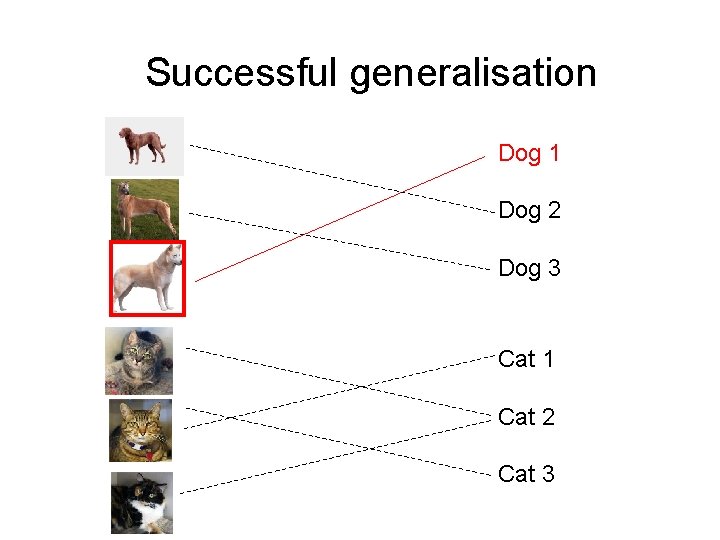

Successful generalisation Dog 1 Dog 2 Dog 3 Cat 1 Cat 2 Cat 3

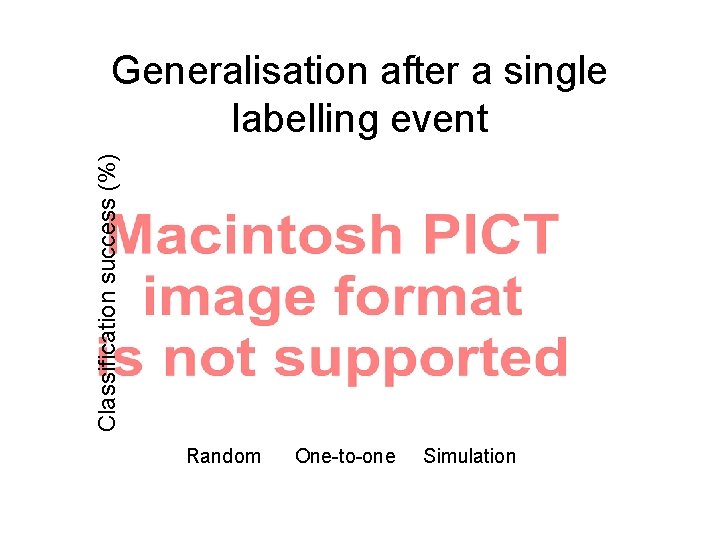

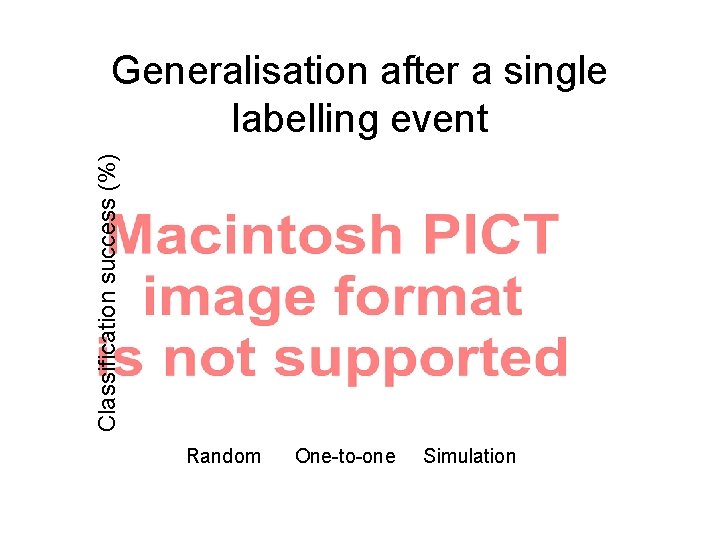

Classification success (%) Generalisation after a single labelling event Random One-to-one Simulation

Role of # of pairings

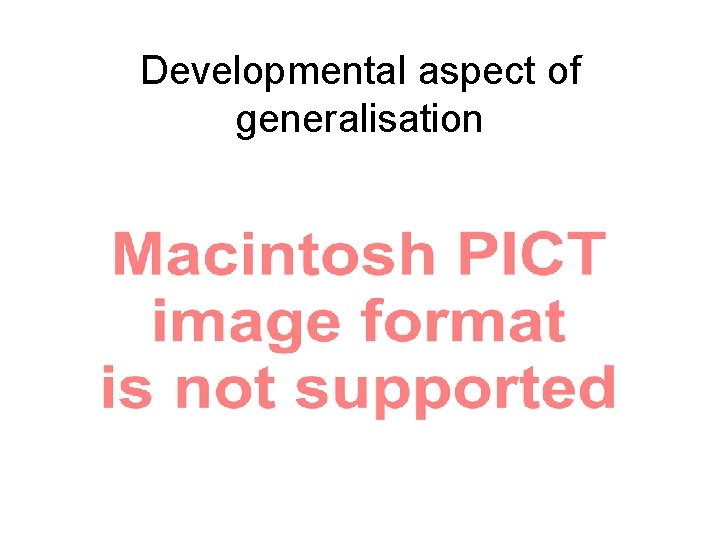

Developmental aspect of generalisation

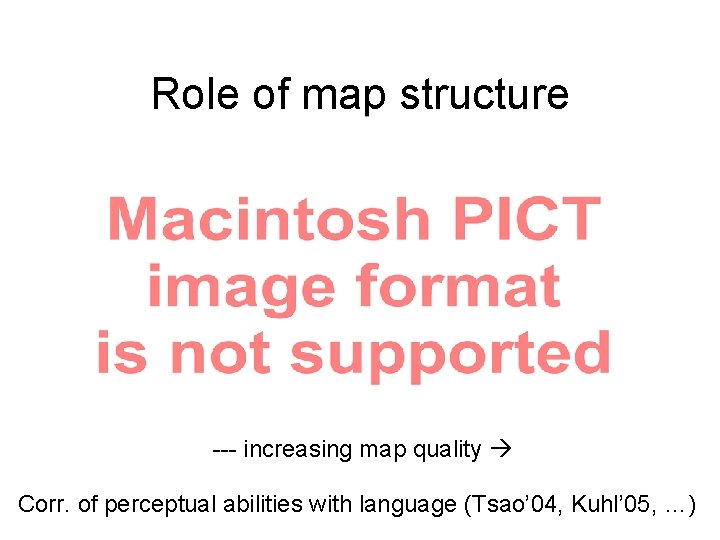

Role of map structure --- increasing map quality Corr. of perceptual abilities with language (Tsao’ 04, Kuhl’ 05, …)

Summary • In a first phase, we feed SOMs with realistic input, visual and acoustic • After maps are structured, we present a single word-object pair from a given class (e. g. dogs) • Generalisation of the label to other images in the same class (other dogs) is successful • We propose the taxonomic ‘constraint’ to be an emergent property of the network

Role of # of Hebbian links

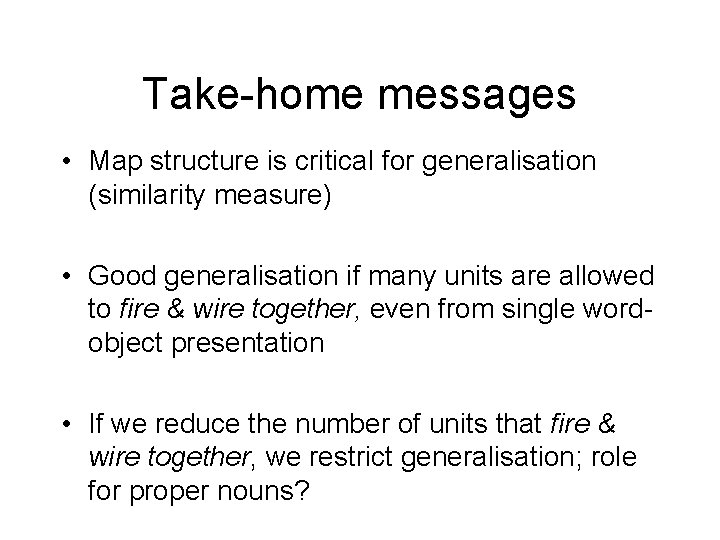

Take-home messages • Map structure is critical for generalisation (similarity measure) • Good generalisation if many units are allowed to fire & wire together, even from single wordobject presentation • If we reduce the number of units that fire & wire together, we restrict generalisation; role for proper nouns?

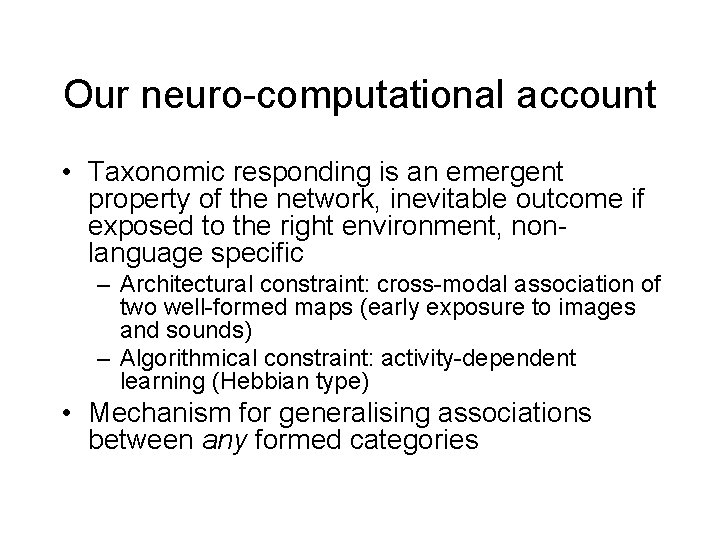

Our neuro-computational account • Taxonomic responding is an emergent property of the network, inevitable outcome if exposed to the right environment, nonlanguage specific – Architectural constraint: cross-modal association of two well-formed maps (early exposure to images and sounds) – Algorithmical constraint: activity-dependent learning (Hebbian type) • Mechanism for generalising associations between any formed categories

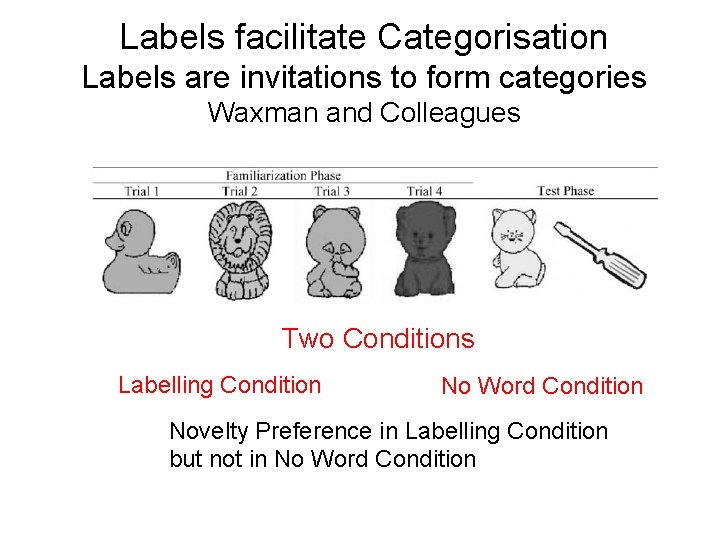

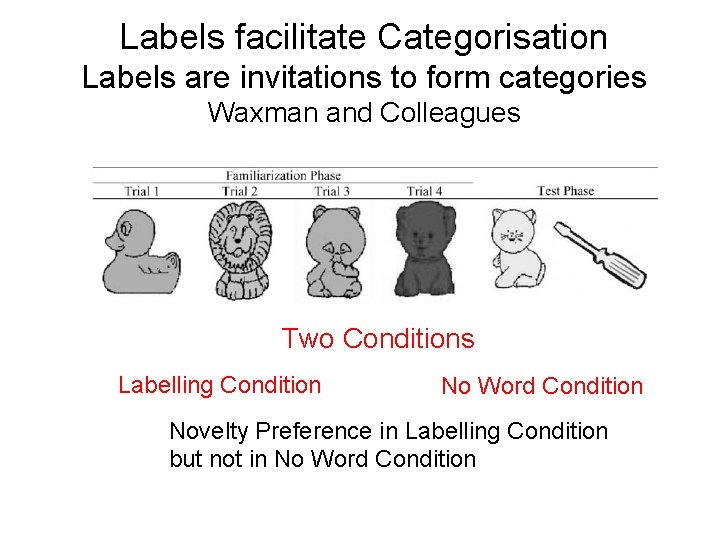

Labels facilitate Categorisation Labels are invitations to form categories Waxman and Colleagues Two Conditions Labelling Condition No Word Condition Novelty Preference in Labelling Condition but not in No Word Condition

Some Difficulties • Familiarisation stimuli probably from categories familiar to the infant – not necessarily category formation but category activation • Only one category is presented during familiarisation – category is not independently motivated by label • “No Word” condition is not a silent condition • Infants show “Out of Category” novelty preferences in the absence of labels • “No Word” condition is anomalous – perhaps overshadowing is occuring: Sloutsky et al.

How to show that labels impact categories formation? • Show that a new visual category has been formed • Show that the structure of labelling events influences the structure of visual categories • Two possibilities – use labels to motivate category formation in the absence of visual structure – use labels to override existing visual categories to form a new category – Requires two labels and/or two categories

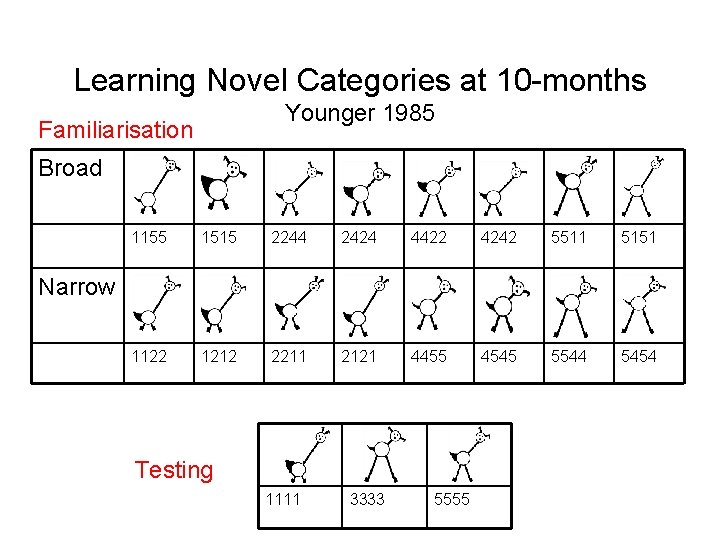

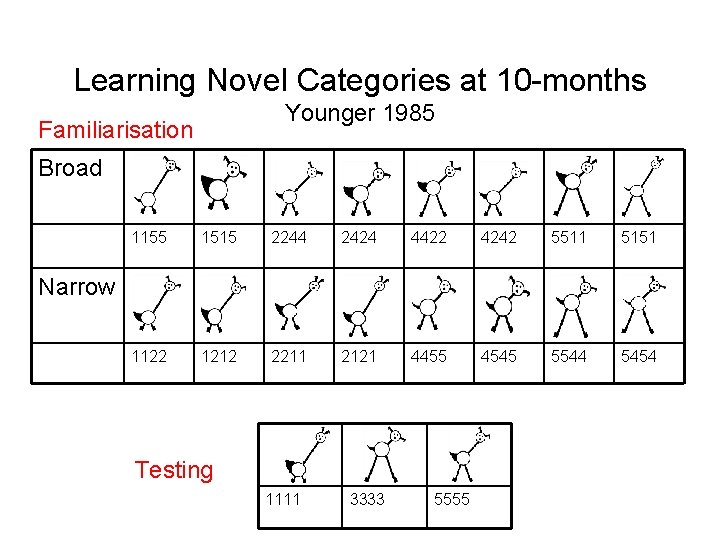

Learning Novel Categories at 10 -months Younger 1985 Familiarisation Broad 1155 1515 2244 2424 4422 4242 5511 5151 1122 1212 2211 2121 4455 4545 5544 5454 Narrow Testing 1111 3333 5555

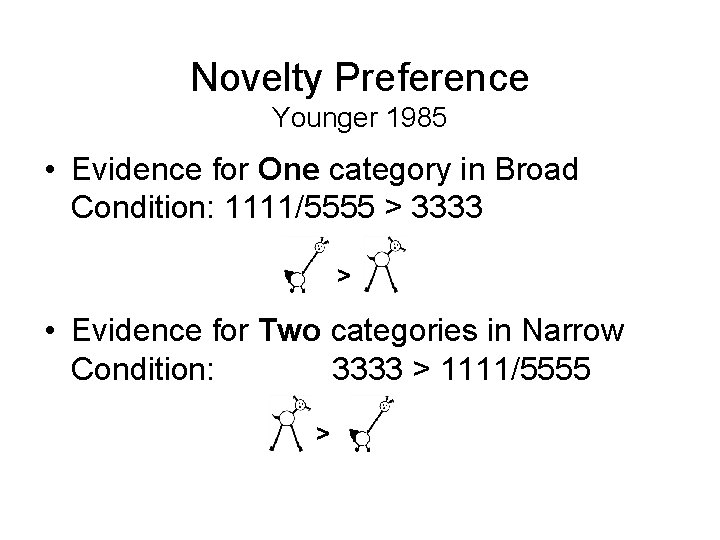

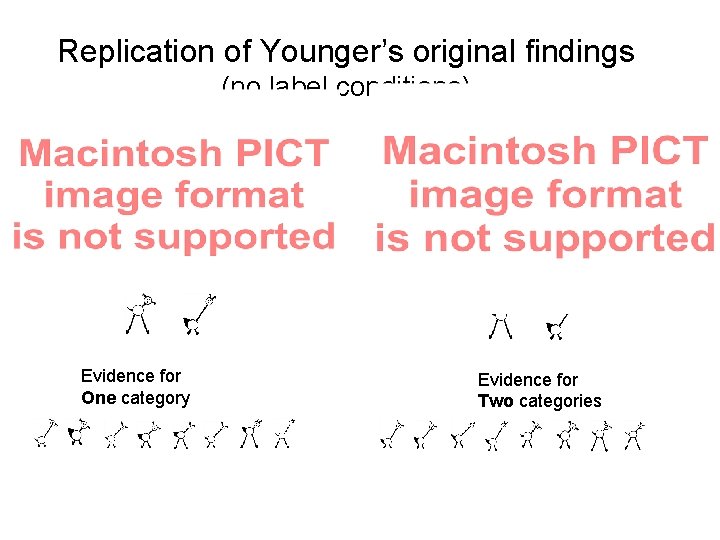

Novelty Preference Younger 1985 • Evidence for One category in Broad Condition: 1111/5555 > 3333 > • Evidence for Two categories in Narrow Condition: 3333 > 1111/5555 >

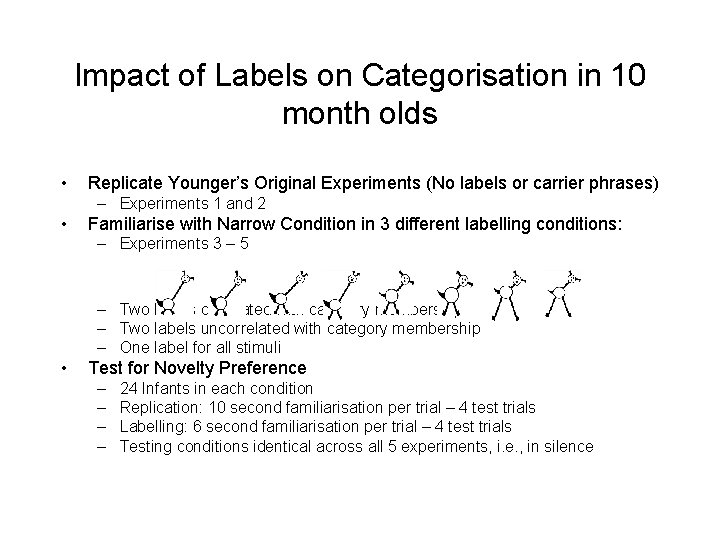

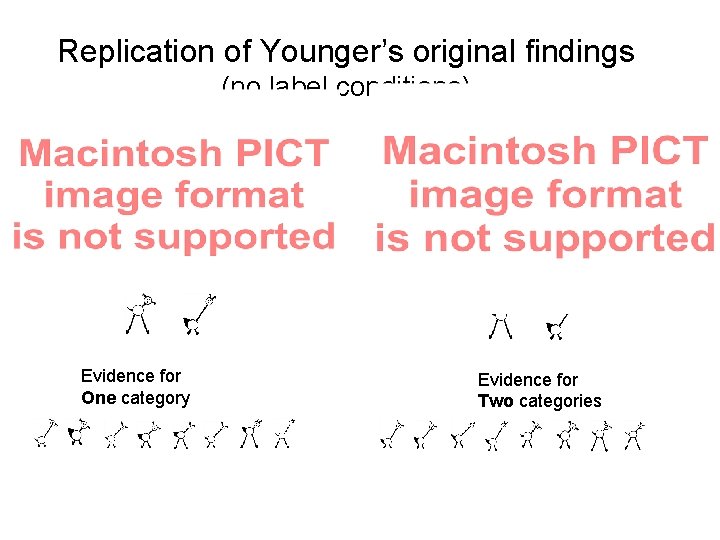

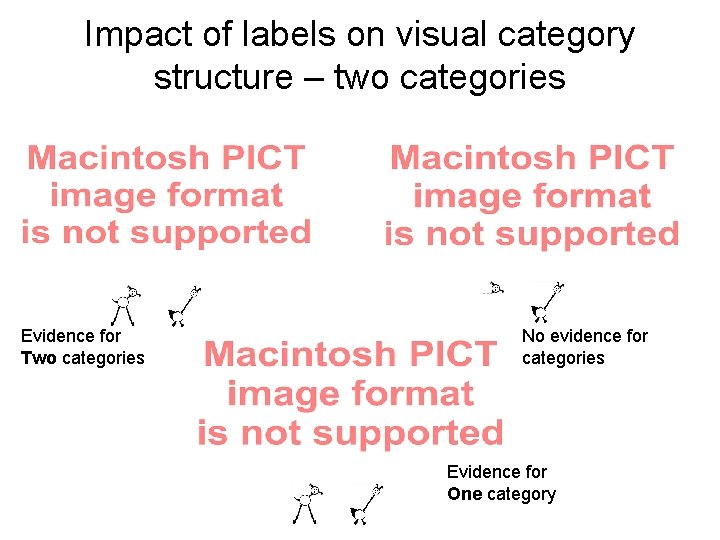

Impact of Labels on Categorisation in 10 month olds • Replicate Younger’s Original Experiments (No labels or carrier phrases) – Experiments 1 and 2 • Familiarise with Narrow Condition in 3 different labelling conditions: – Experiments 3 – 5 – Two labels correlated with category membership – Two labels uncorrelated with category membership – One label for all stimuli • Test for Novelty Preference – – 24 Infants in each condition Replication: 10 second familiarisation per trial – 4 test trials Labelling: 6 second familiarisation per trial – 4 test trials Testing conditions identical across all 5 experiments, i. e. , in silence

Familiarisation Findings • Hearing labels highlights attention to objects • Infants track perceptual similarity of objects

Replication of Younger’s original findings (no label conditions) Evidence for One category Evidence for Two categories

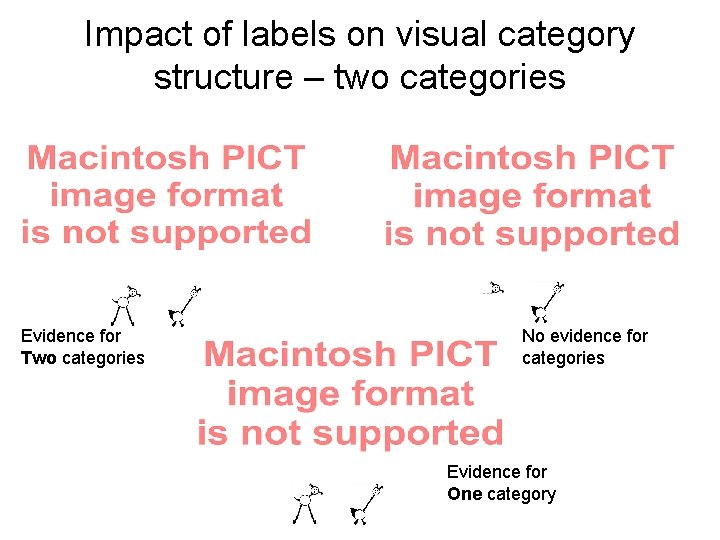

Impact of labels on visual category structure – two categories Evidence for Two categories No evidence for categories Evidence for One category

Conclusions • Infants compute the cross-modal statistical correlations between labels and visual objects during the categorisation process • Labels can override dissimilarities between objects so that they are treated as being perceptually more similar. • No evidence for label facilitation • No evidence for auditory dominance

Ongoing and Future Work • • Can labels divide as well as unite? Do words have a privileged status? The impact of perceptual similarity Integration with word learning