CONDUIT 4 A computer code for the simulation

- Slides: 49

CONDUIT 4 A computer code for the simulation of magma ascent through volcanic conduits and fissures Paolo Papale and Margherita Polacci Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia - Pisa

Dobran (JVGR 1992): DUCT • Steady, isothermal, two-phase non-equilibrium flow • Volcanic conduit or fissure • Homogeneous flow, bubbly flow, and gas-particle/droplet flow regimes • Fragmentation at critical volume fraction (0. 75) • Constant liquid density • Simple relationships for liquid viscosity and water solubility • Ideal gas properties

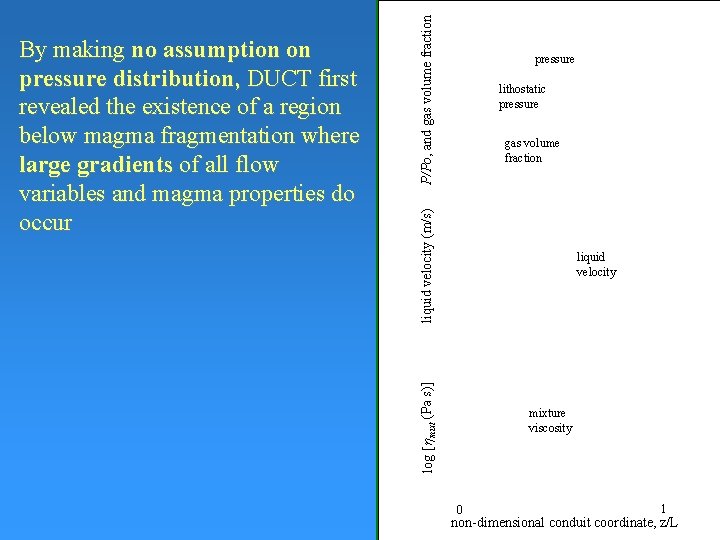

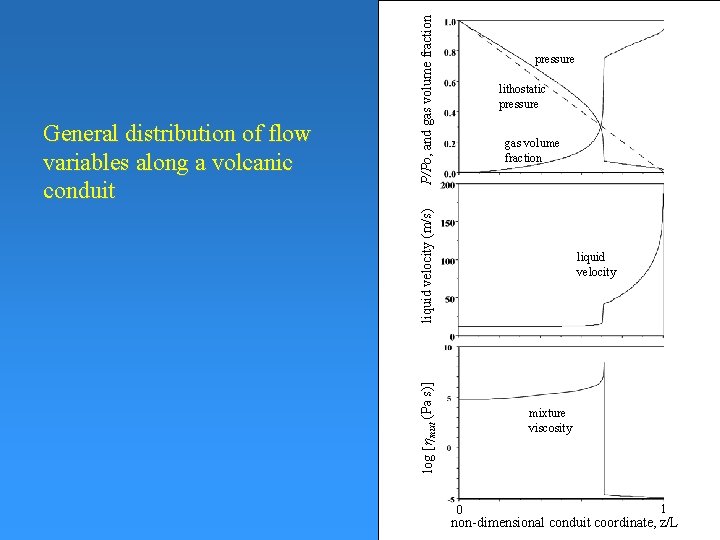

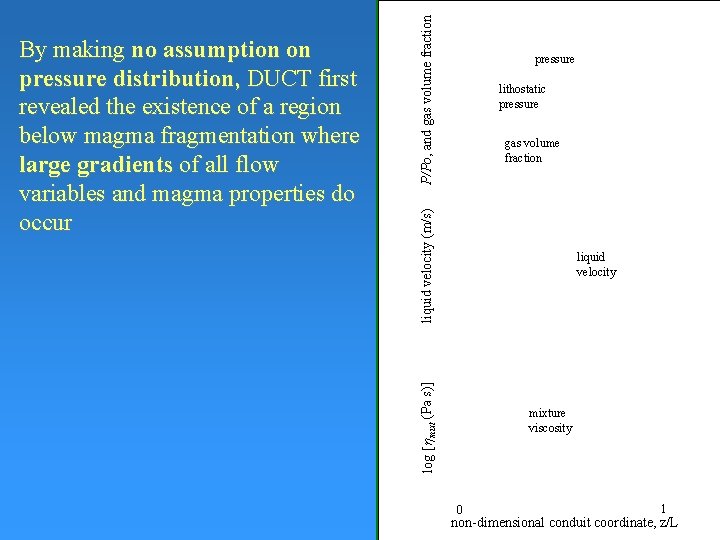

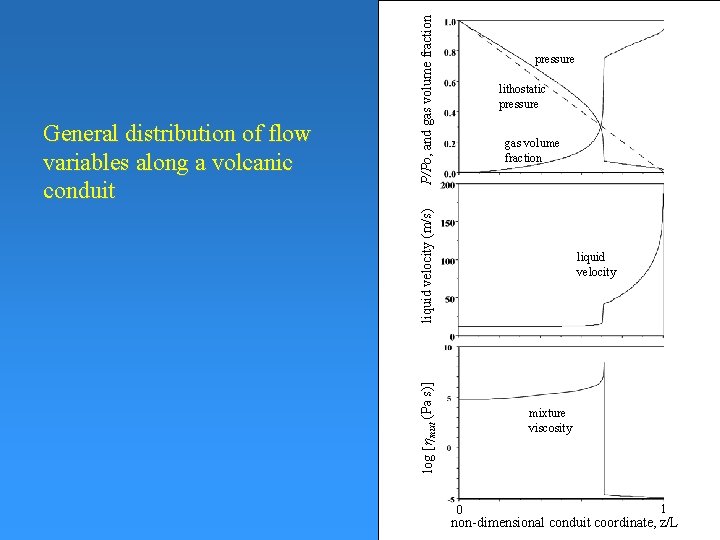

P/Po, and gas volume fraction pressure lithostatic pressure liquid velocity (m/s) gas volume fraction liquid velocity log [hmixt (Pa s)] By making no assumption on pressure distribution, DUCT first revealed the existence of a region below magma fragmentation where large gradients of all flow variables and magma properties do occur mixture viscosity 0 1 non-dimensional conduit coordinate, z/L

Papale and Dobran (JVGR 1993, JGR 1994): CONDUIT 2 • Magma properties on the basis of magma composition (10 major oxides + water) • Multiphase (gas phase, and homogeneous liquid+crystal phase) • Real gas properties • Applications to the AD 79 Vesuvius and May 18, 1980 Mount St. Helens eruptions • Applications to hazard forecasting at Vesuvius, with coupled simulations of conduit flow and atmospheric dispersion dynamics (Dobran et al. , Nature 1993)

Papale (FMTT 1998), Papale et al. (JVGR 1998), Papale and Polacci (BV 1999): CONDUIT 3 • Inclusion of carbon dioxide as an additional volatile component • Inclusion of separately developed (Papale, CMP 1997, AM 1999) modeling for water, carbon dioxide, and water+carbon dioxide saturation as a function of liquid magma composition • Applications to parametric studies on the role of magma composition, water content, carbon dioxide content, and crystal content on the magma ascent dynamics (also Polacci et al. , submitted) • Coupling with atmospheric dispersion and pyroclastic flow modeling, for parametric studies and hazard forecasting (Neri et al. , JVGR 1998, JVGR in press; Todesco et al. , BV 2002)

Water solubility in silicate liquids with natural magmatic composition After Papale, 1997

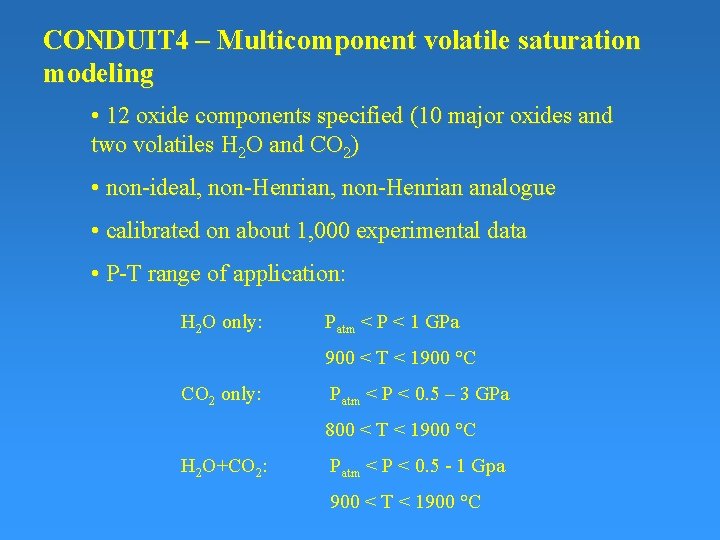

CONDUIT 4 – Multicomponent volatile saturation modeling • 12 oxide components specified (10 major oxides and two volatiles H 2 O and CO 2) • non-ideal, non-Henrian analogue • calibrated on about 1, 000 experimental data • P-T range of application: H 2 O only: Patm < P < 1 GPa 900 < T < 1900 °C CO 2 only: Patm < P < 0. 5 – 3 GPa 800 < T < 1900 °C H 2 O+CO 2: Patm < P < 0. 5 - 1 Gpa 900 < T < 1900 °C

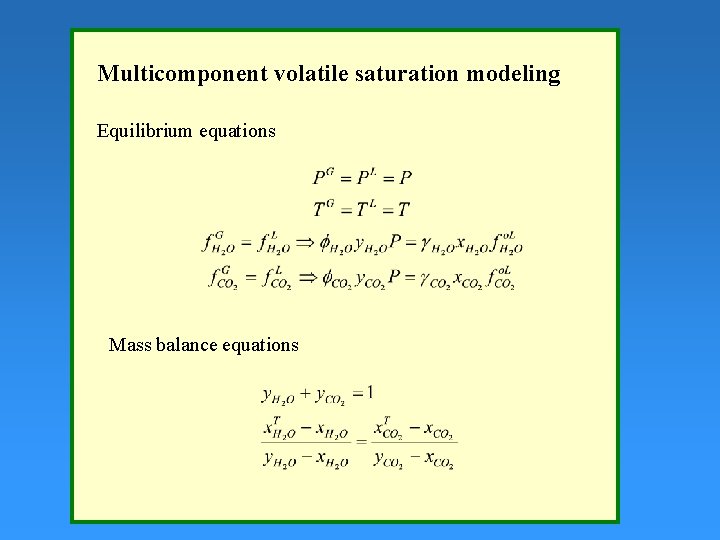

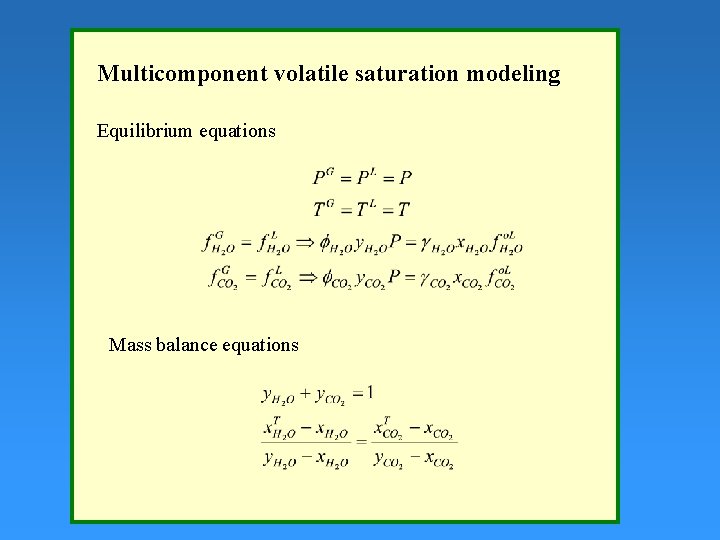

Multicomponent volatile saturation modeling Equilibrium equations Mass balance equations

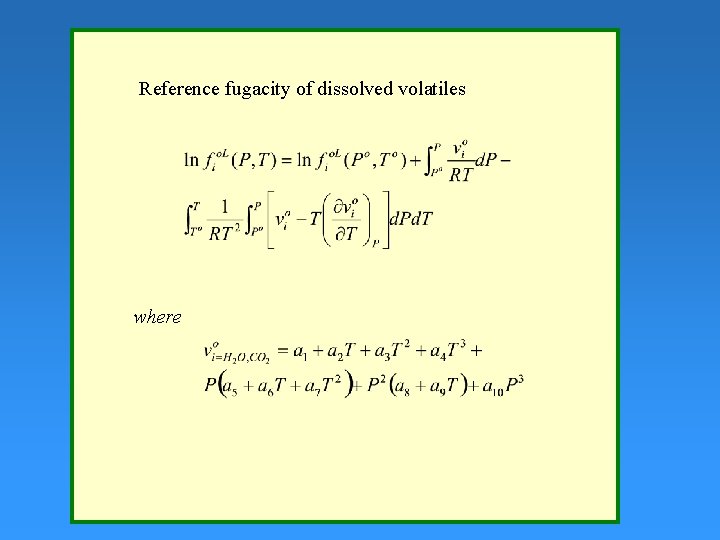

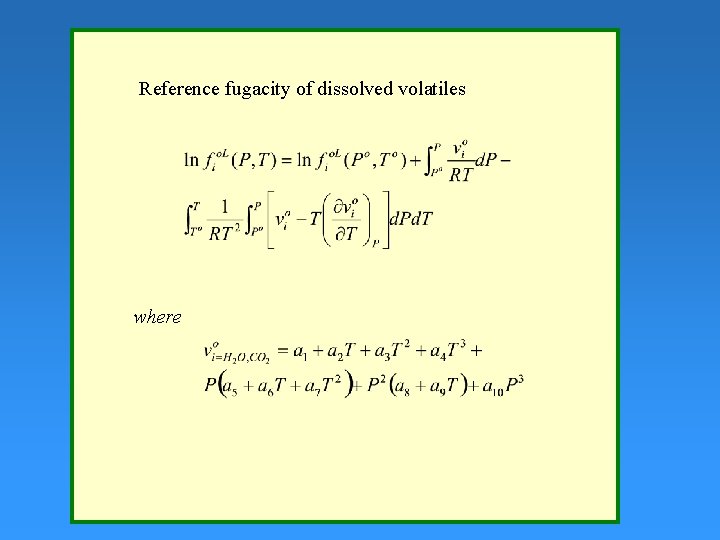

Reference fugacity of dissolved volatiles where

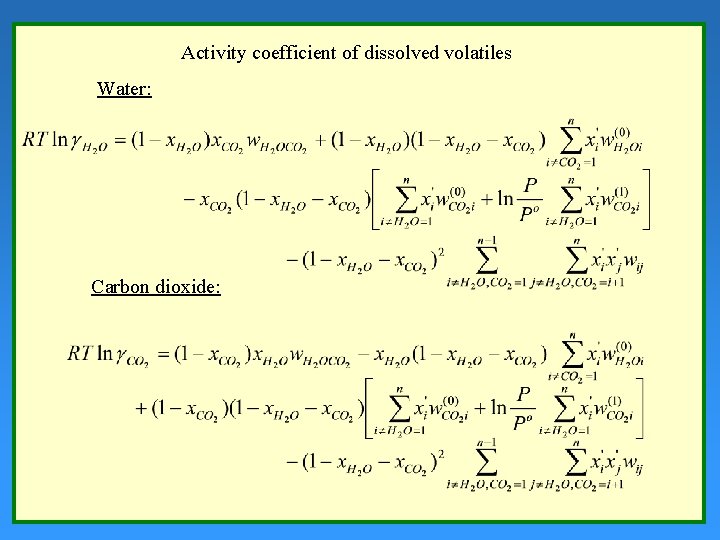

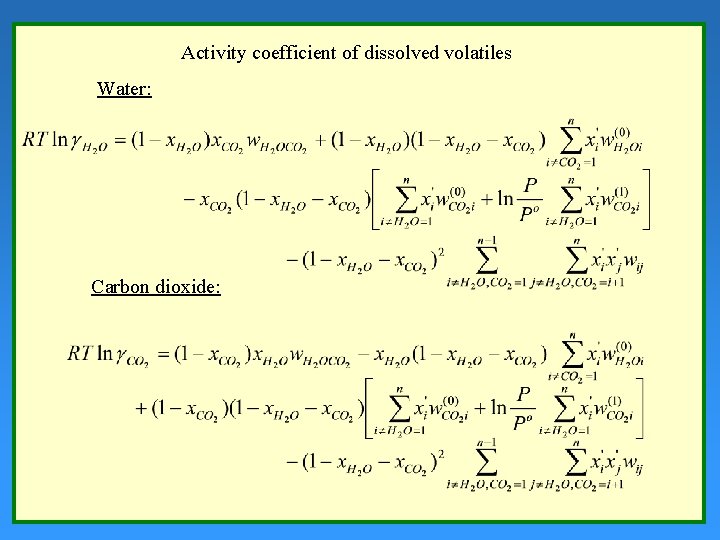

Activity coefficient of dissolved volatiles Water: Carbon dioxide:

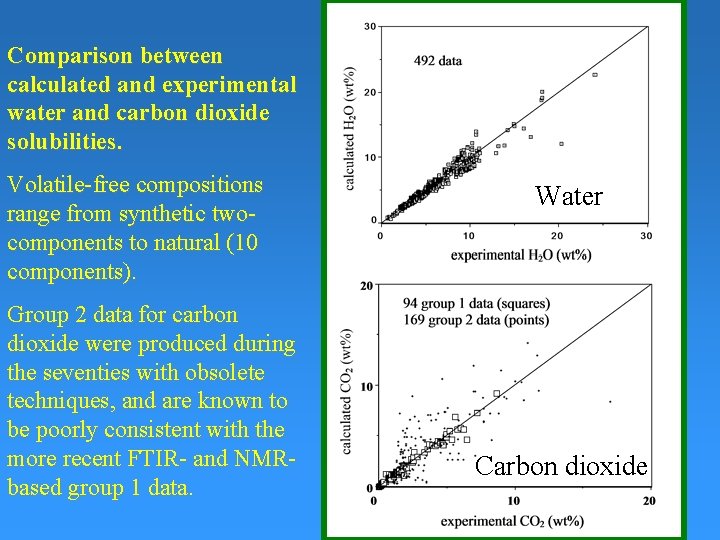

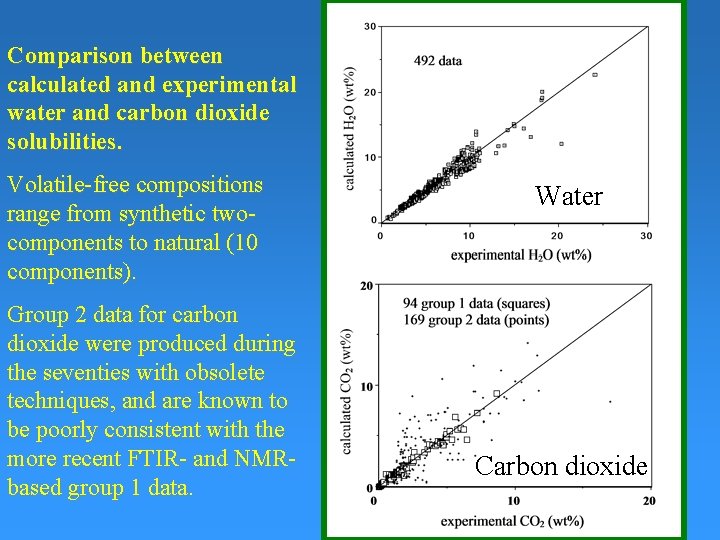

Comparison between calculated and experimental water and carbon dioxide solubilities. Volatile-free compositions range from synthetic twocomponents to natural (10 components). Group 2 data for carbon dioxide were produced during the seventies with obsolete techniques, and are known to be poorly consistent with the more recent FTIR- and NMRbased group 1 data. Water Carbon dioxide

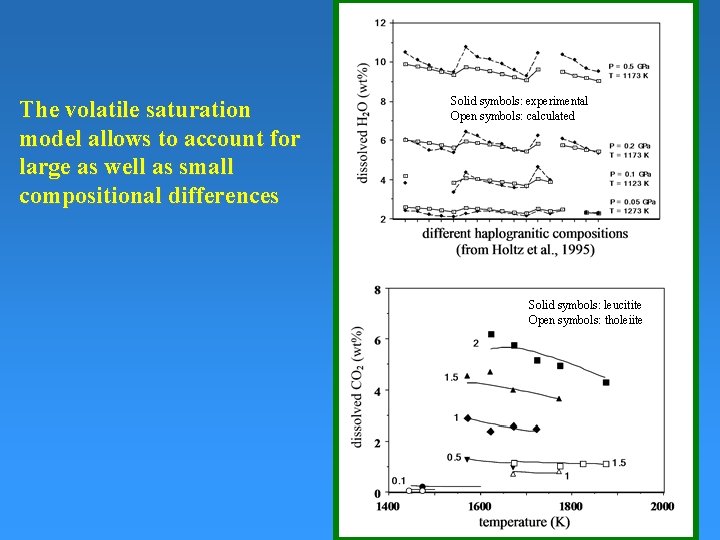

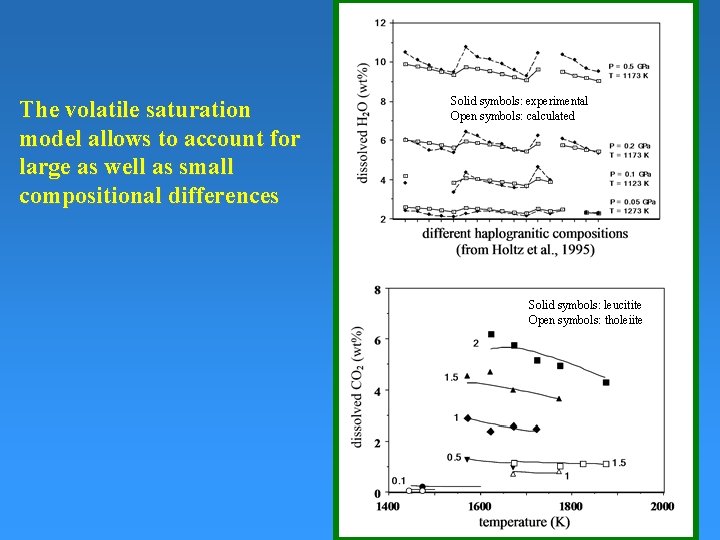

The volatile saturation model allows to account for large as well as small compositional differences Solid symbols: experimental Open symbols: calculated Solid symbols: leucitite Open symbols: tholeiite

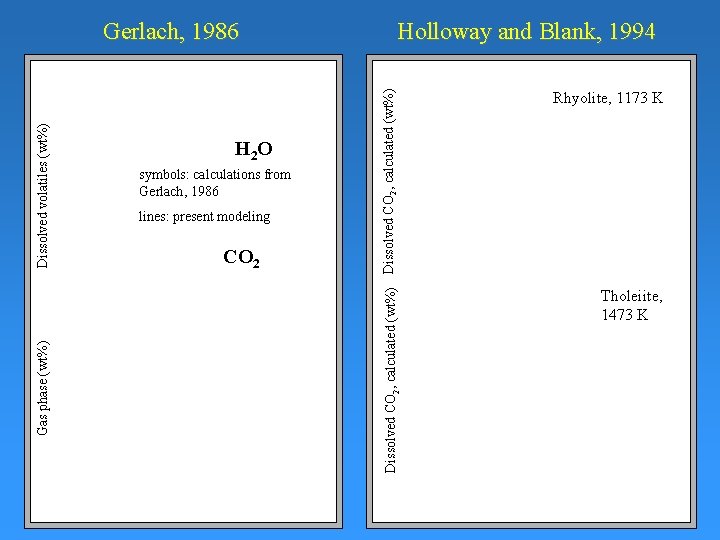

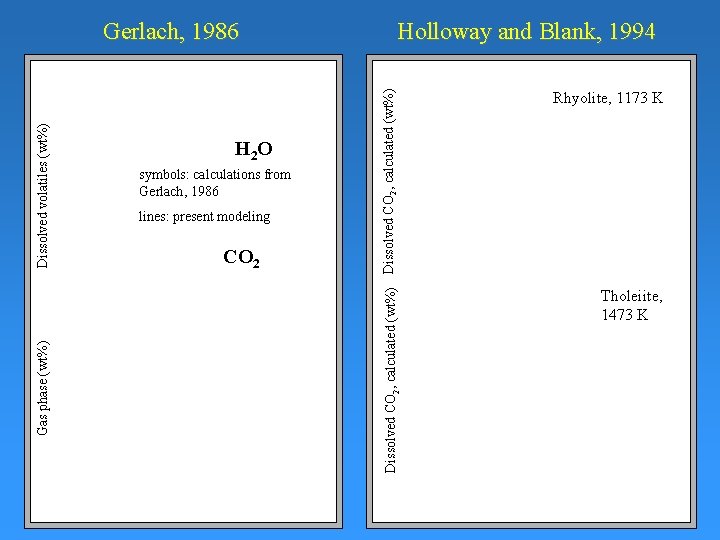

H 2 O symbols: calculations from Gerlach, 1986 lines: present modeling CO 2 Holloway and Blank, 1994 Dissolved CO 2, calculated (wt%) Gas phase (wt%) Dissolved volatiles (wt%) Gerlach, 1986 Rhyolite, 1173 K Tholeiite, 1473 K

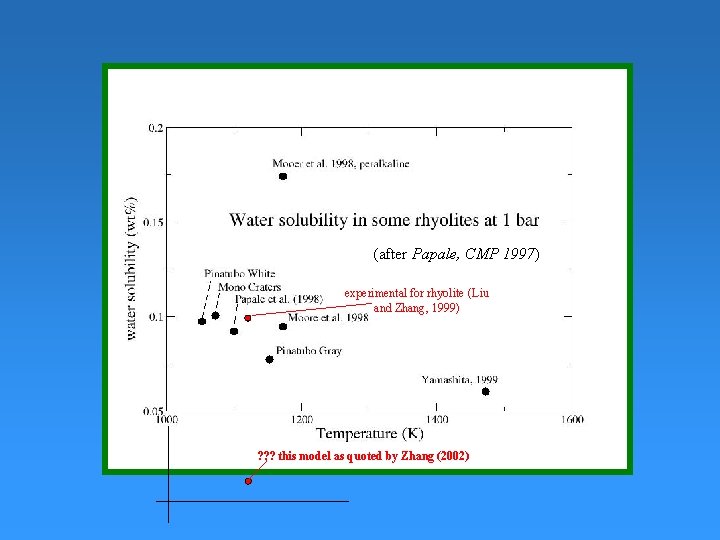

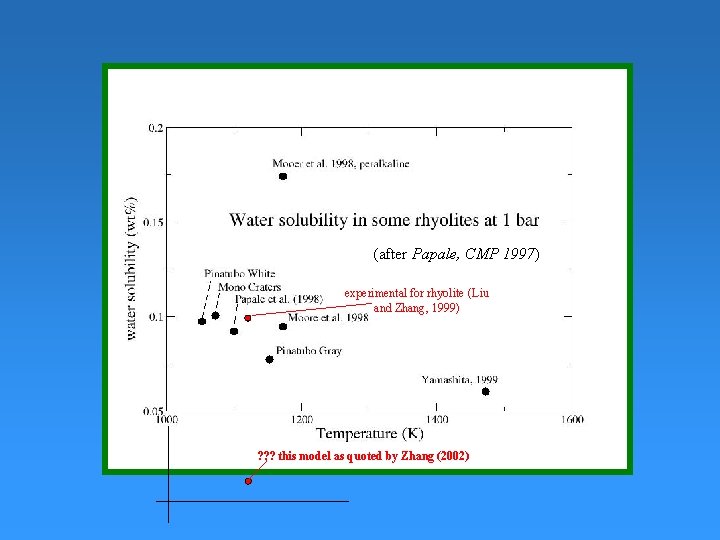

(after Papale, CMP 1997) experimental for rhyolite (Liu and Zhang, 1999) ? ? ? this model as quoted by Zhang (2002)

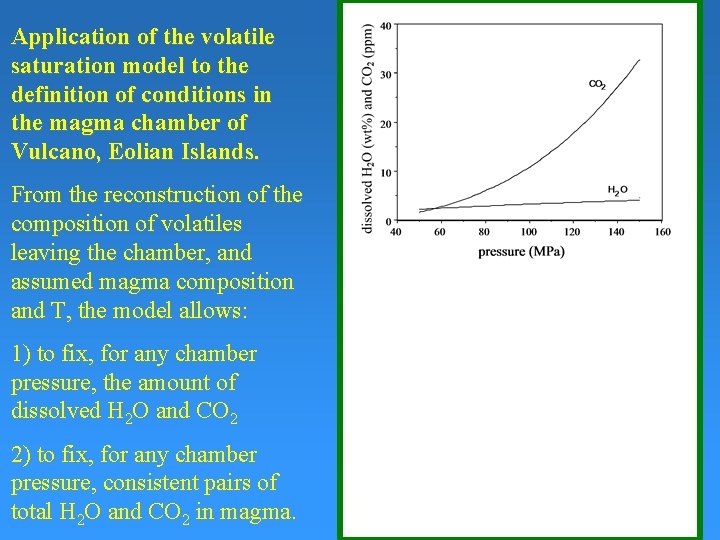

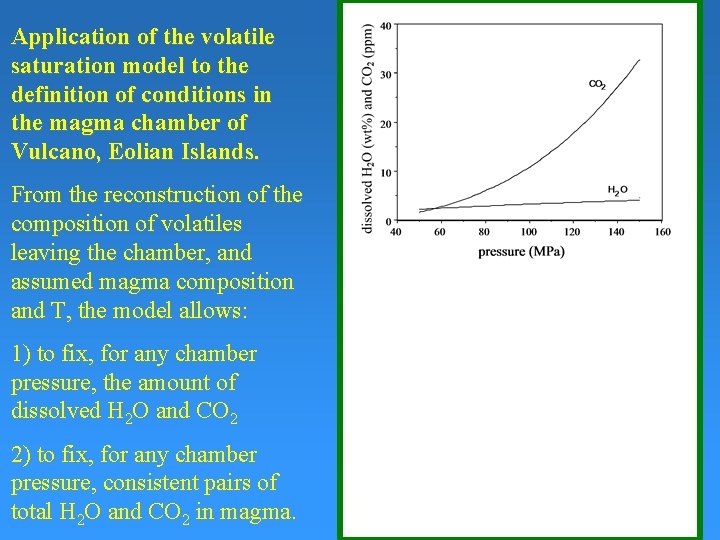

Application of the volatile saturation model to the definition of conditions in the magma chamber of Vulcano, Eolian Islands. From the reconstruction of the composition of volatiles leaving the chamber, and assumed magma composition and T, the model allows: 1) to fix, for any chamber pressure, the amount of dissolved H 2 O and CO 2 2) to fix, for any chamber pressure, consistent pairs of total H 2 O and CO 2 in magma.

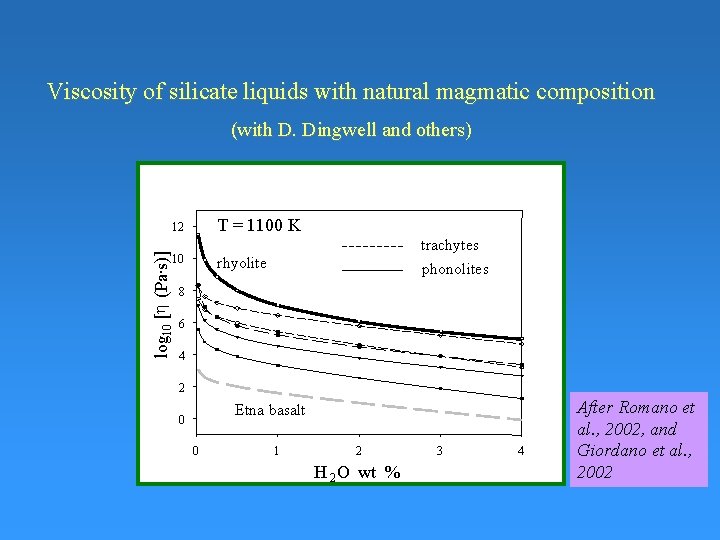

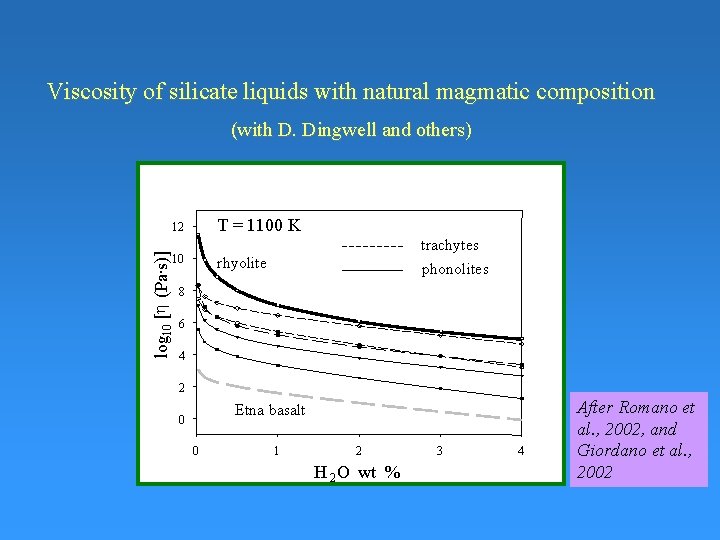

Viscosity of silicate liquids with natural magmatic composition (with D. Dingwell and others) T = 1100 K log 10 [h (Pa·s)] 12 IGC MNV trachytes 10 rhyolite phonolites 8 6 4 2 Etna basalt 0 0 1 2 H 2 O wt % 3 4 After Romano et al. , 2002, and Giordano et al. , 2002

CONDUIT 4 - Multiphase non-Newtonian magma viscosity • Effect of solid particles (crystals, xenoliths, etc. ) by the Einstein-Roscoe equation with Marsh (1981) calibration up to about 40 vol. % (not known above) • Role of gas bubbles by the Ishii and Zuber (1979) equation (assumes undeformable bubbles) • Liquid pseudo-plasticity (or viscous thinning) by the Bottinga (1994) model calibrated on data from Webb and Dingwell (1990) • Magma viscoelasticity forming the base of the fragmentation criterion.

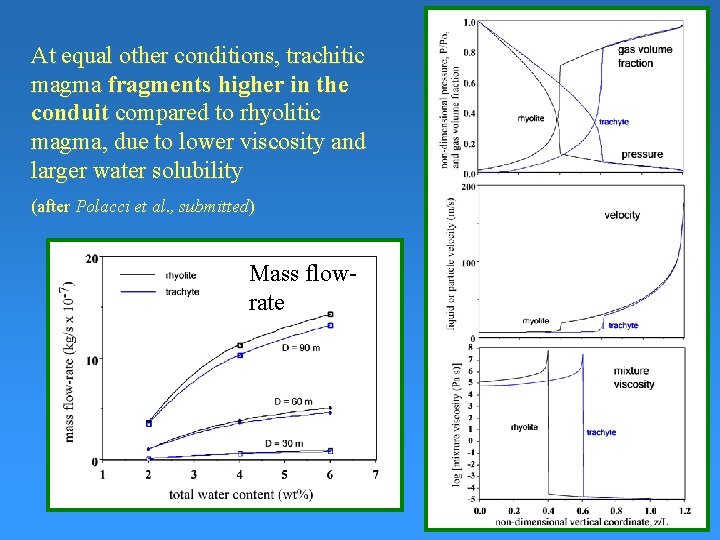

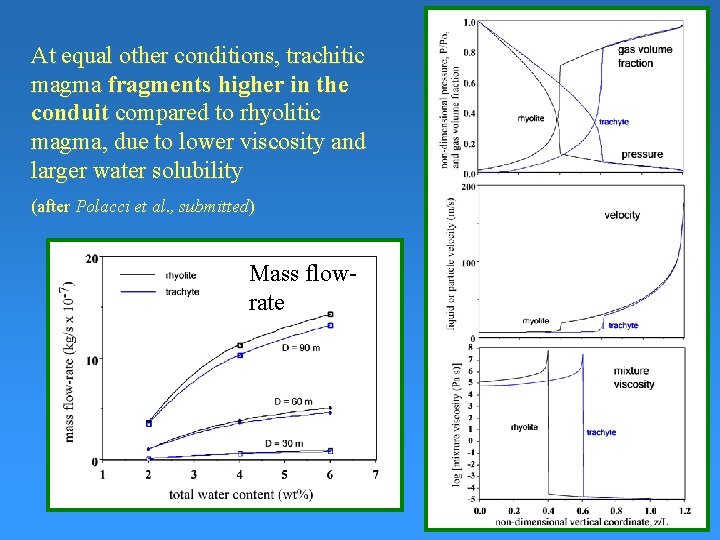

At equal other conditions, trachitic magma fragments higher in the conduit compared to rhyolitic magma, due to lower viscosity and larger water solubility (after Polacci et al. , submitted) Mass flowrate

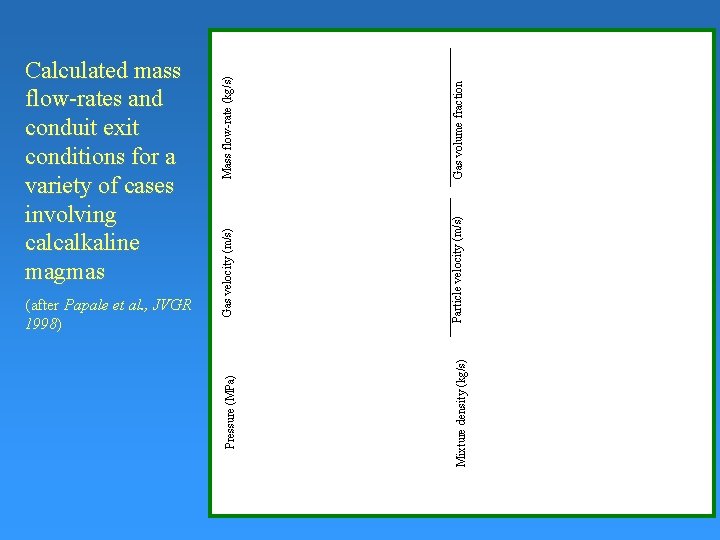

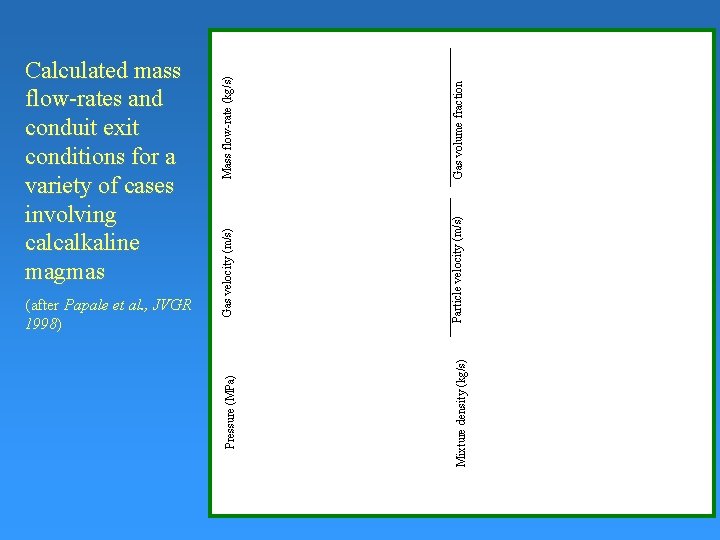

Gas volume fraction Particle velocity (m/s) Mixture density (kg/s) Mass flow-rate (kg/s) Gas velocity (m/s) (after Papale et al. , JVGR 1998) Pressure (MPa) Calculated mass flow-rates and conduit exit conditions for a variety of cases involving calcalkaline magmas

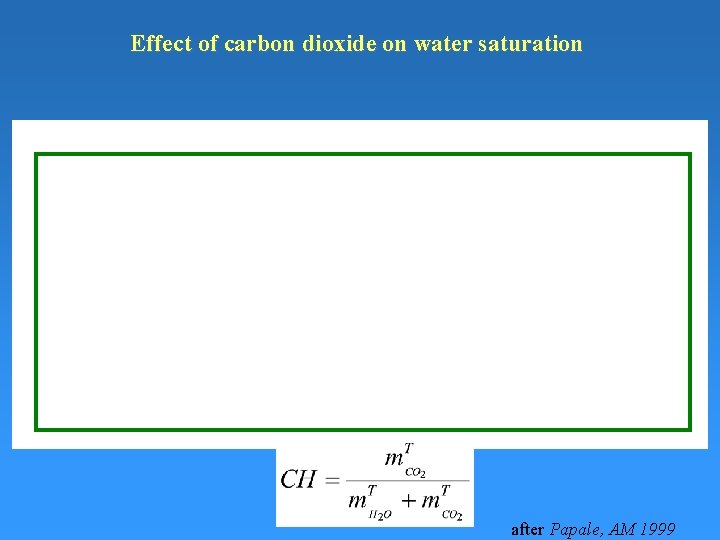

Effect of carbon dioxide on water saturation Composition: rhyolite, Temperature: 1100 K after Papale, AM 1999

non-dimensional pressure Effect of carbon dioxide on water saturation After Papale and Polacci, 1999

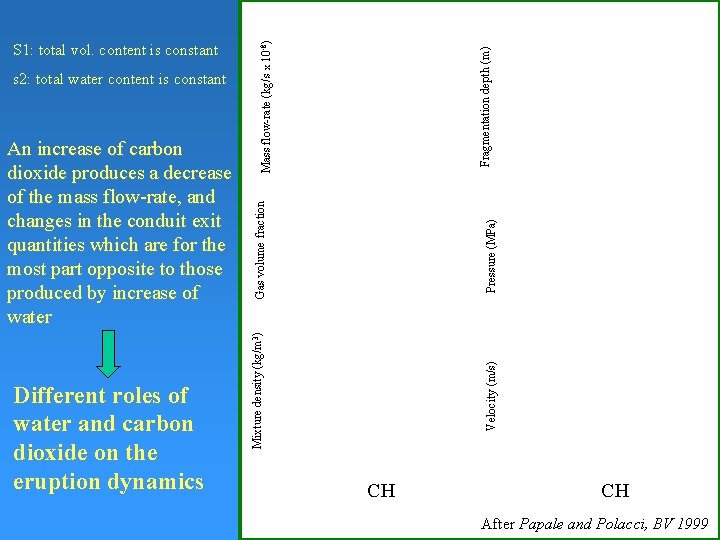

Fragmentation depth (m) Pressure (MPa) Velocity (m/s) Different roles of water and carbon dioxide on the eruption dynamics Mass flow-rate (kg/s x 10 -8) An increase of carbon dioxide produces a decrease of the mass flow-rate, and changes in the conduit exit quantities which are for the most part opposite to those produced by increase of water Gas volume fraction s 2: total water content is constant Mixture density (kg/m 3) S 1: total vol. content is constant CH CH After Papale and Polacci, BV 1999

Papale (Nature 1999): CONDUIT 3 • Inclusion of a dynamic fragmentation criterion based on rateinduced viscous to elastic transition of magma (based on Maxwell equation and experimental work by Dingwell and Webb 1990)

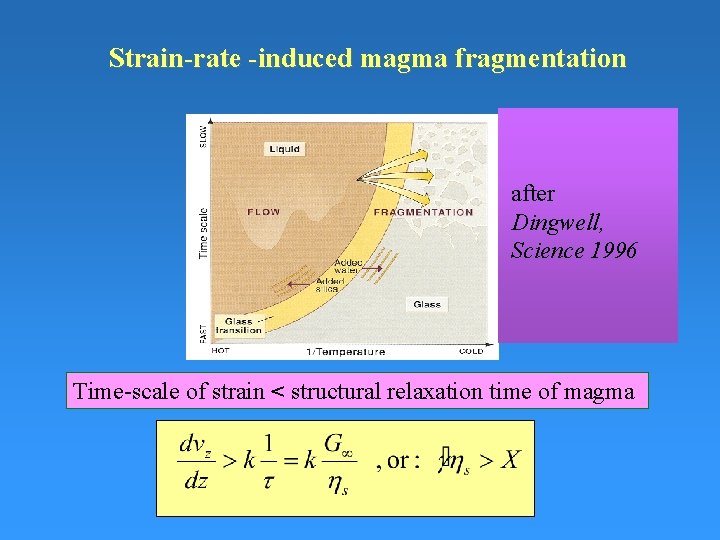

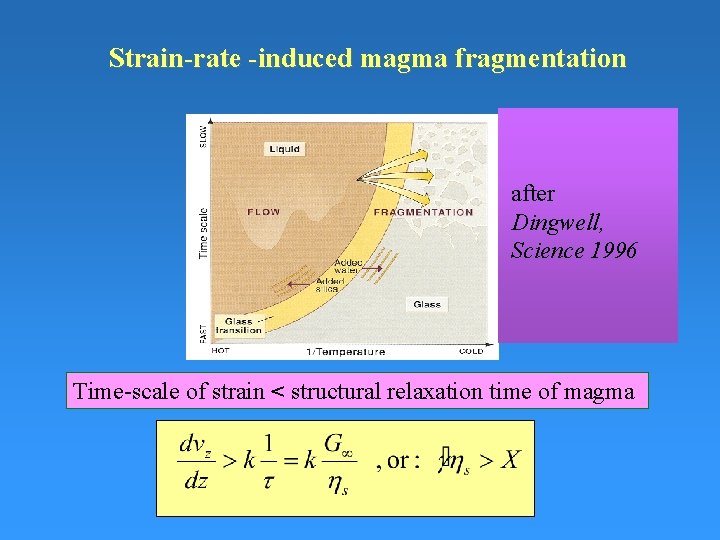

Strain-rate -induced magma fragmentation The glass transition in time-reciprocal temperature space. Deformations slower than the structural relaxation time generated a relaxed, viscous liquid response of the melt. When the time scale of deformation approaches that of the glass transition t, the result is elastic storage of strain energy for low strains and shear thinning and brittle failure for high strains. The glass transition may be crossed many times during the formation of volcanic glasses. The first crossing may be the prymary fragmentation event in explosive volcanism. Variations in water and silica contents can drastically shift the temperature at which the transition in mechanical behavior is experienced. Thus, magmatic differentiation and degassing are important processes influencing the melt’s mechanical behavior during volcanic eruptions. (From Dingwell – Science) after Dingwell, Science 1996 Time-scale of strain < structural relaxation time of magma

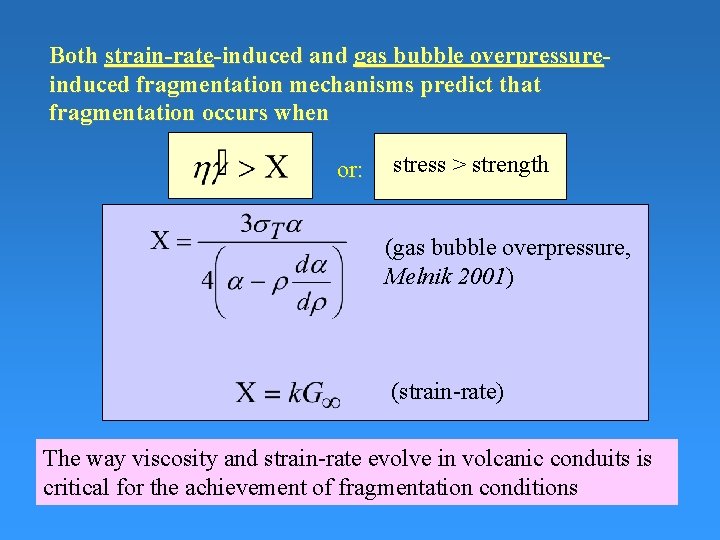

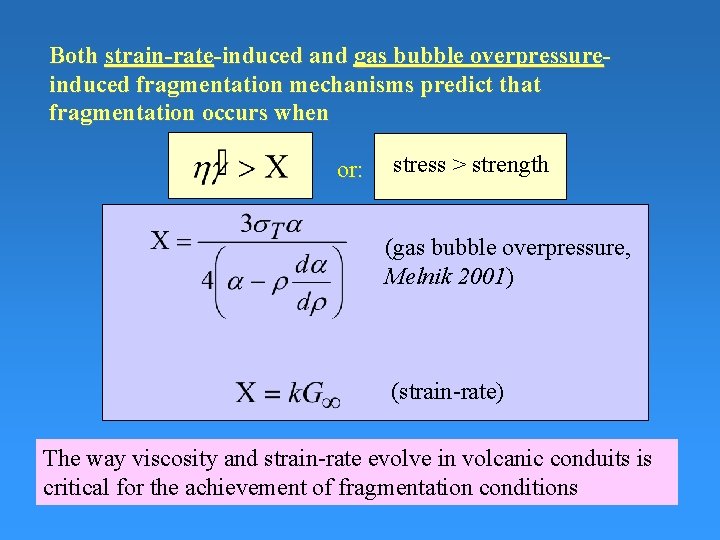

Both strain-rate-induced and gas bubble overpressureinduced fragmentation mechanisms predict that fragmentation occurs when or: stress > strength (gas bubble overpressure, Melnik 2001) (strain-rate) The way viscosity and strain-rate evolve in volcanic conduits is critical for the achievement of fragmentation conditions

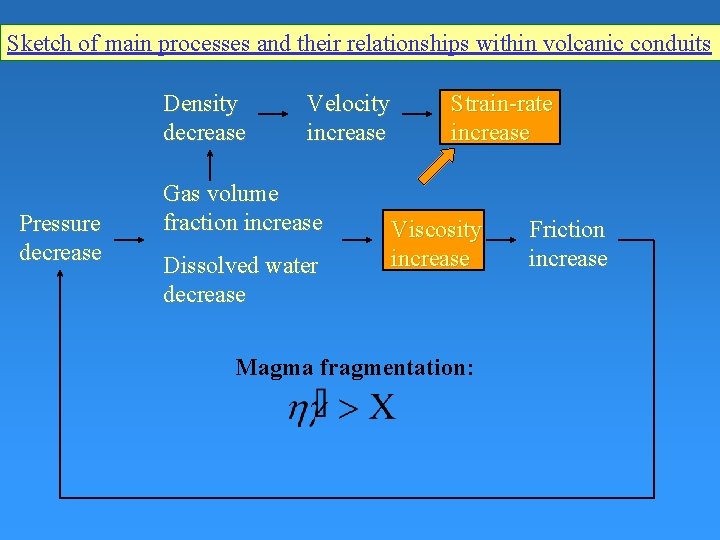

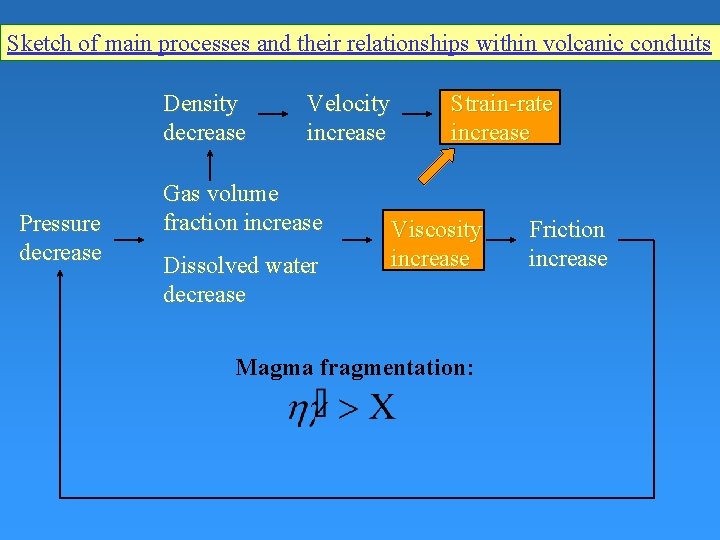

Sketch of main processes and their relationships within volcanic conduits Density decrease Pressure decrease Velocity increase Gas volume fraction increase Dissolved water decrease Strain-rate increase Viscosity increase Magma fragmentation: Friction increase

P/Po, and gas volume fraction lithostatic pressure liquid velocity (m/s) gas volume fraction liquid velocity log [hmixt (Pa s)] General distribution of flow variables along a volcanic conduit pressure mixture viscosity 0 1 non-dimensional conduit coordinate, z/L

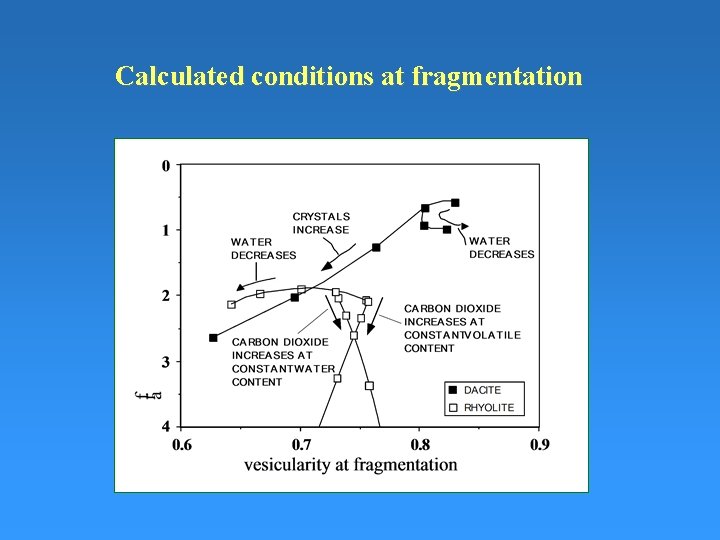

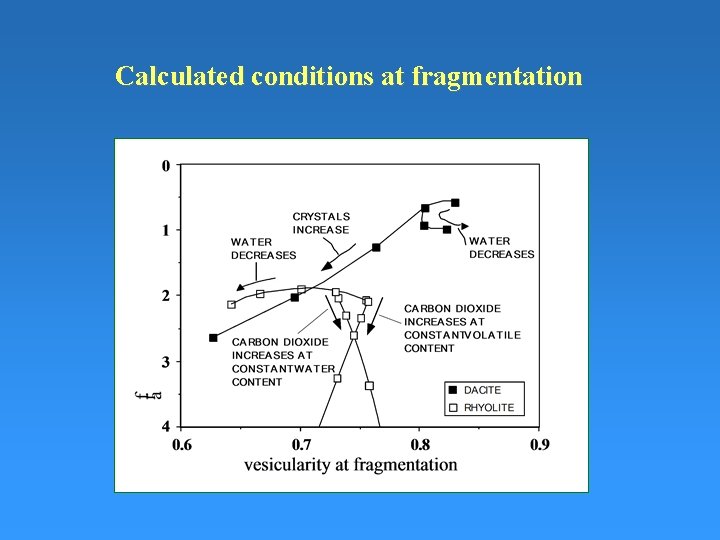

Calculated conditions at fragmentation

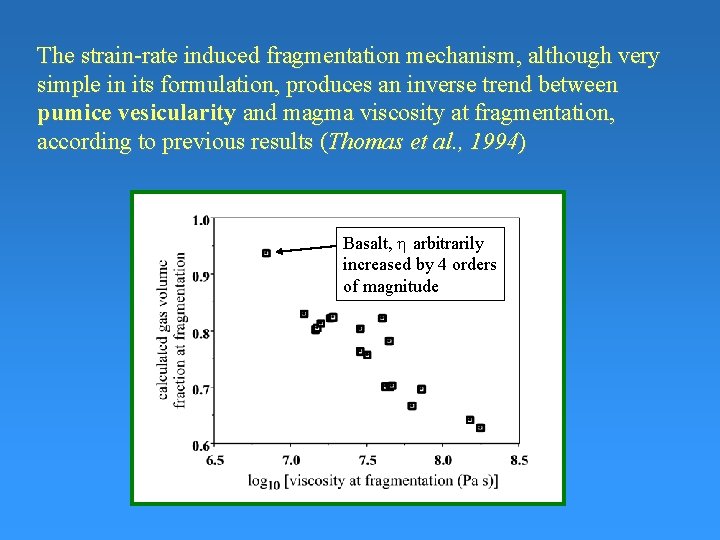

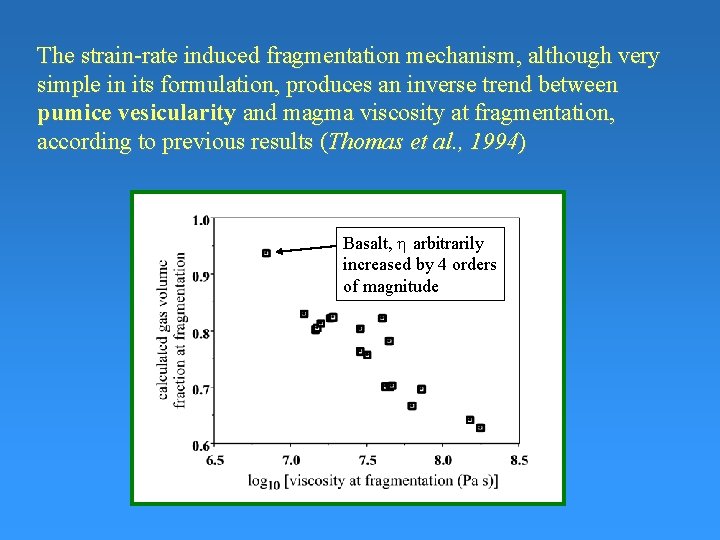

The strain-rate induced fragmentation mechanism, although very simple in its formulation, produces an inverse trend between pumice vesicularity and magma viscosity at fragmentation, according to previous results (Thomas et al. , 1994) Basalt, h arbitrarily increased by 4 orders of magnitude

Papale (JGR 2001): CONDUIT 4 • Inclusion of different kinds of particles formed at fragmentation: pumice (three-phase liquid/glass+crystal+gas bubble particles), ash (one-phase liquid/glass particles), and free crystals • New constitutive equations for mechanical gas-particle and particle-particle interactions covering conditions from dilute to dense gas-particle mixtures • Inclusion of a pumice non-equilibrium degassing parameter

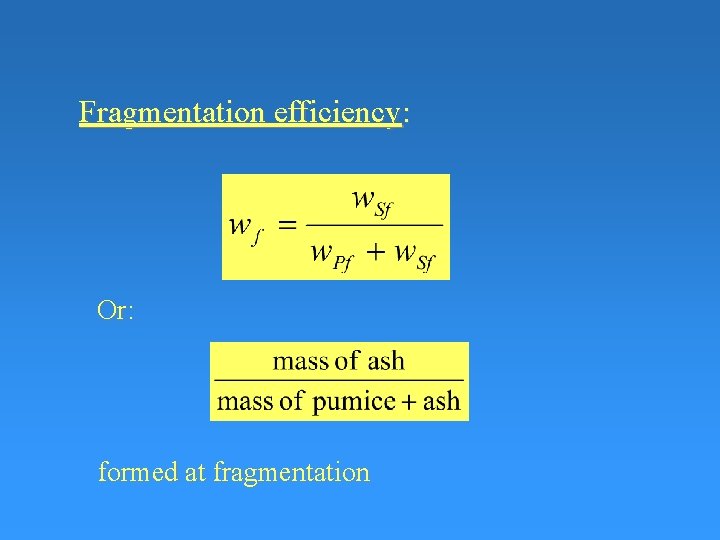

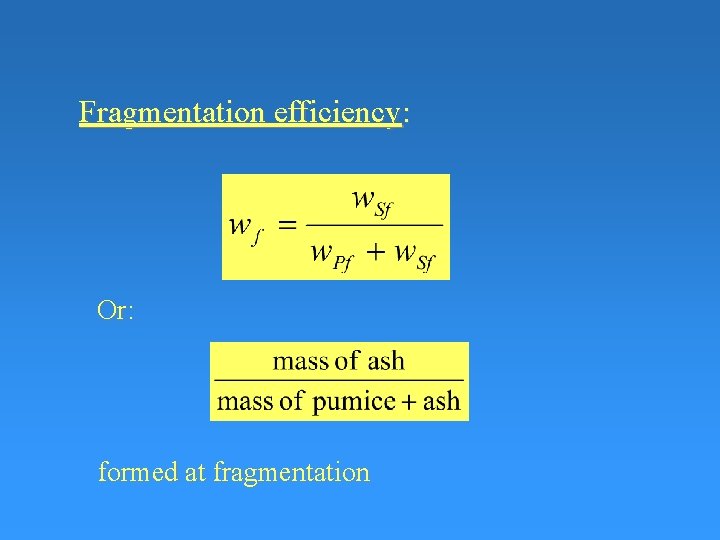

Fragmentation efficiency: Or: formed at fragmentation

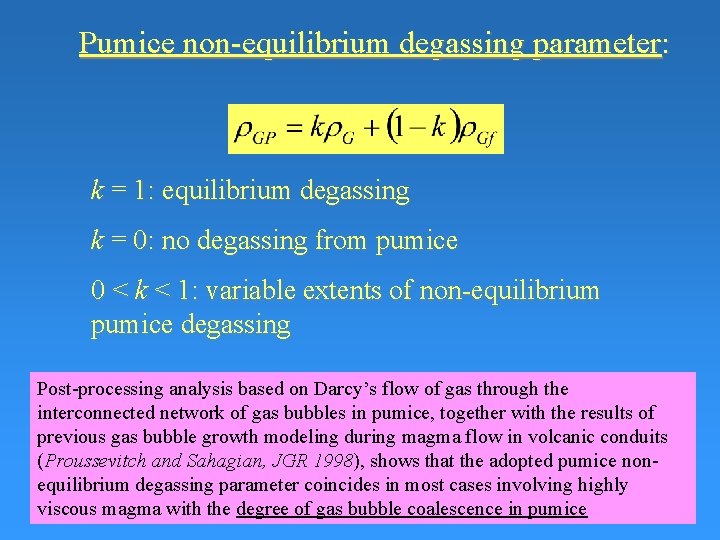

Pumice non-equilibrium degassing parameter: k = 1: equilibrium degassing k = 0: no degassing from pumice 0 < k < 1: variable extents of non-equilibrium pumice degassing Post-processing analysis based on Darcy’s flow of gas through the interconnected network of gas bubbles in pumice, together with the results of previous gas bubble growth modeling during magma flow in volcanic conduits (Proussevitch and Sahagian, JGR 1998), shows that the adopted pumice nonequilibrium degassing parameter coincides in most cases involving highly viscous magma with the degree of gas bubble coalescence in pumice

Natural pumice shows a large variability of vesicle textures, and largely different degrees of vesicle coalescence

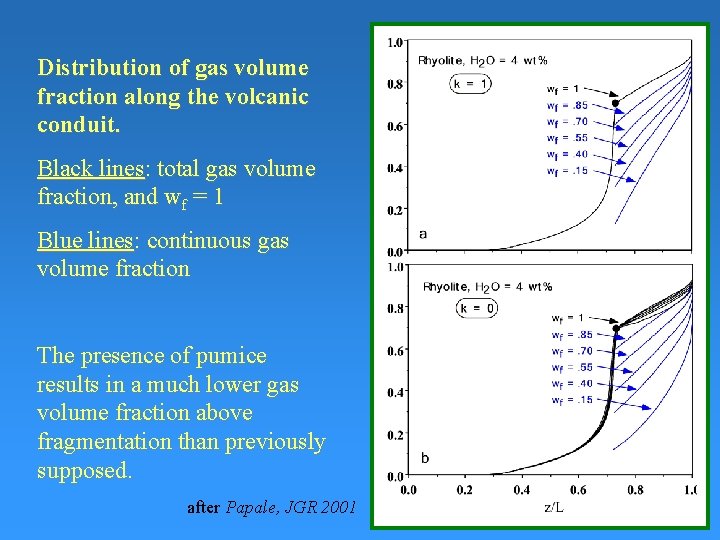

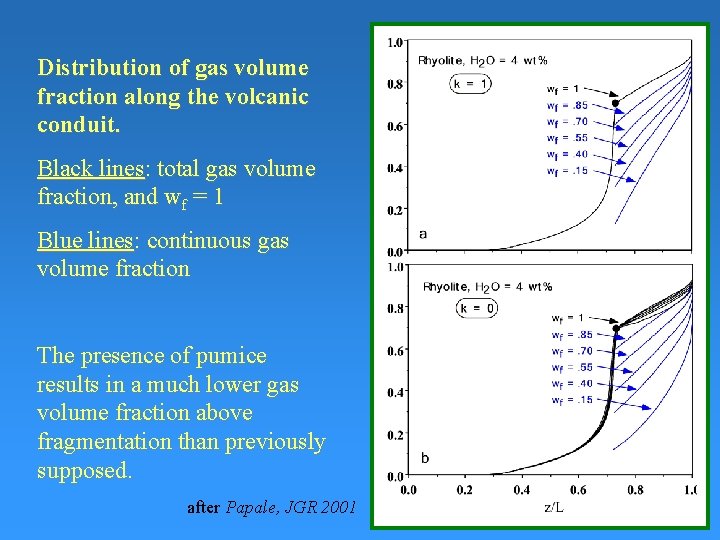

Distribution of gas volume fraction along the volcanic conduit. Black lines: total gas volume fraction, and wf = 1 Blue lines: continuous gas volume fraction The presence of pumice results in a much lower gas volume fraction above fragmentation than previously supposed. after Papale, JGR 2001

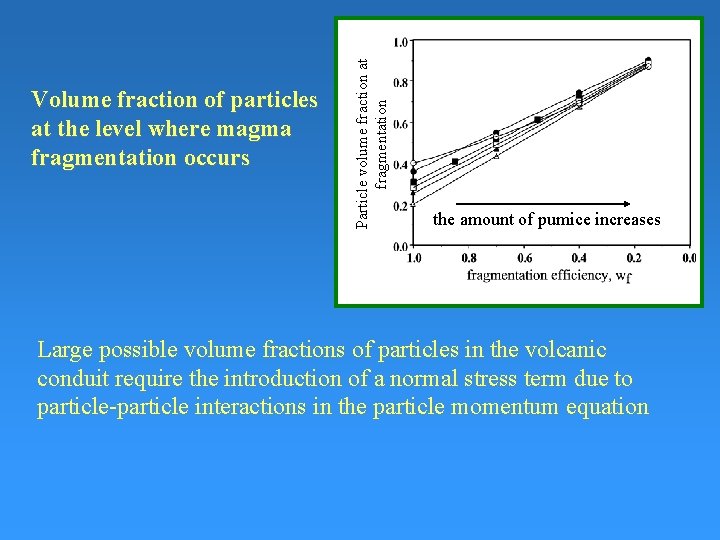

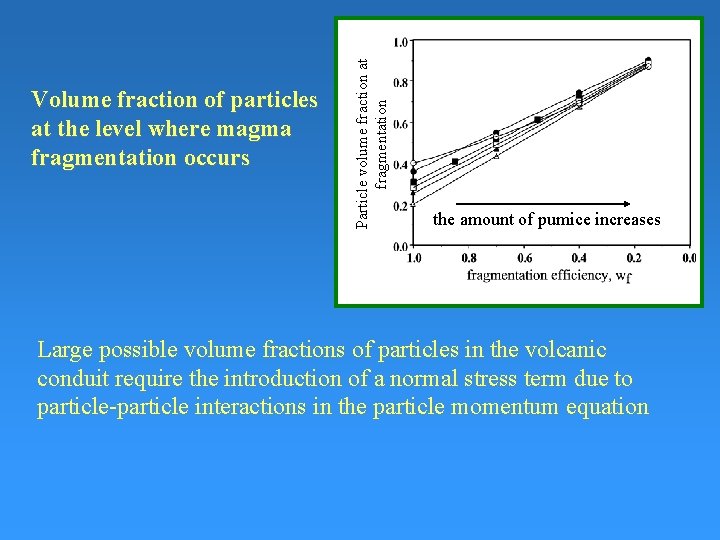

Particle volume fraction at fragmentation Volume fraction of particles at the level where magma fragmentation occurs the amount of pumice increases Large possible volume fractions of particles in the volcanic conduit require the introduction of a normal stress term due to particle-particle interactions in the particle momentum equation

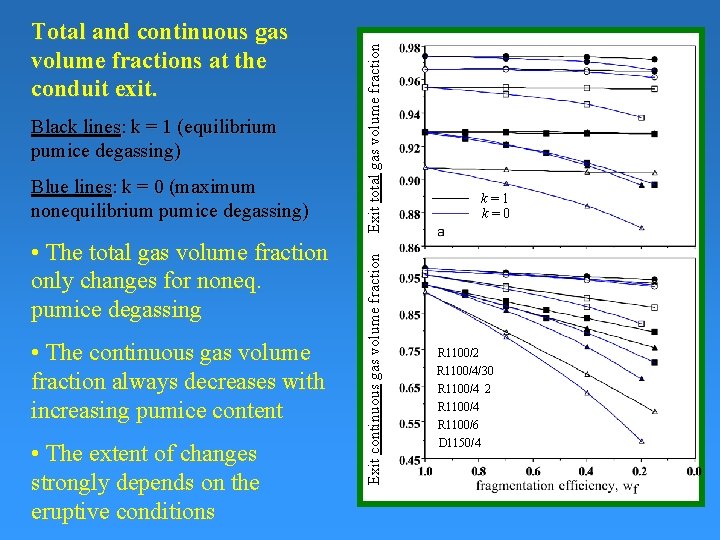

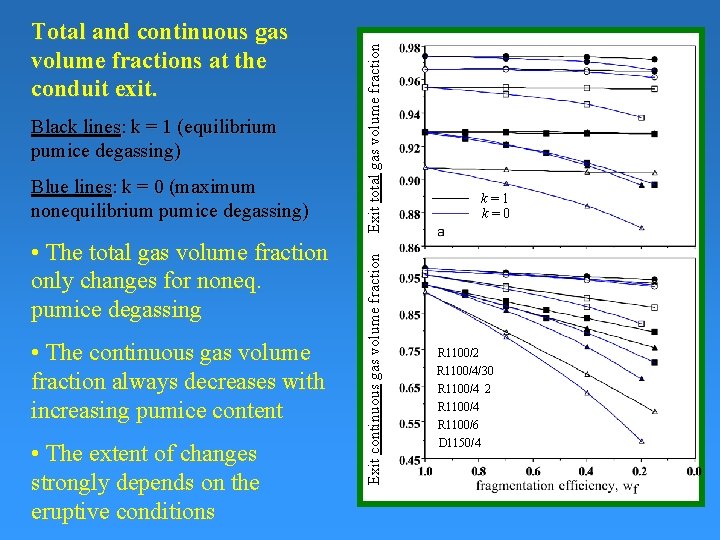

Blue lines: k = 0 (maximum nonequilibrium pumice degassing) • The total gas volume fraction only changes for noneq. pumice degassing • The continuous gas volume fraction always decreases with increasing pumice content • The extent of changes strongly depends on the eruptive conditions Exit total gas volume fraction Black lines: k = 1 (equilibrium pumice degassing) Exit continuous gas volume fraction Total and continuous gas volume fractions at the conduit exit. k=1 k=0 R 1100/2 R 1100/4/30 R 1100/4_2 R 1100/4 R 1100/6 D 1150/4

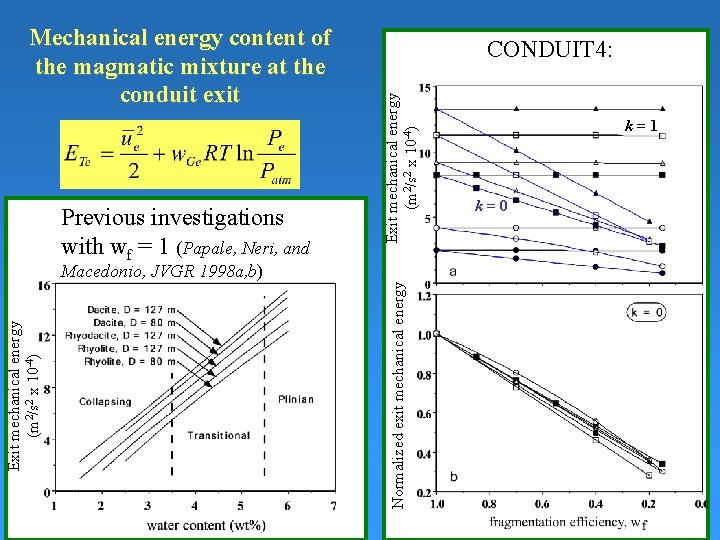

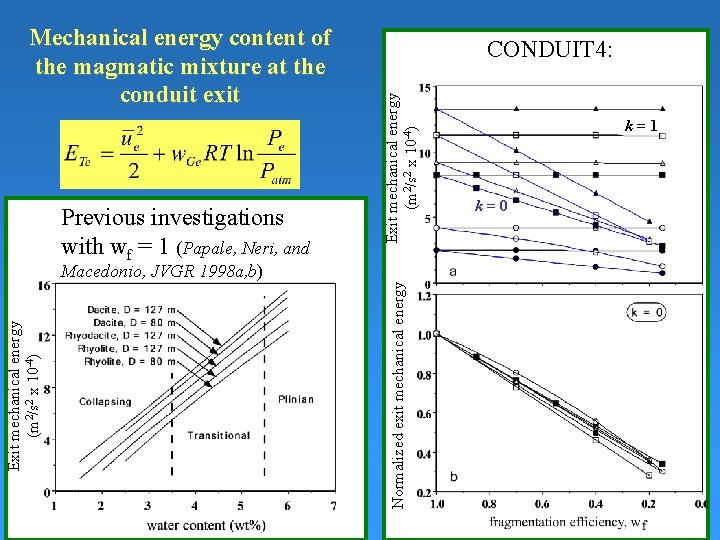

Previous investigations with wf = 1 (Papale, Neri, and CONDUIT 4: Exit mechanical energy (m 2/s 2 x 10 -4) Mechanical energy content of the magmatic mixture at the conduit exit Normalized exit mechanical energy Exit mechanical energy (m 2/s 2 x 10 -4) Macedonio, JVGR 1998 a, b) k=1 k=0

CONDUIT 4: Particularly suitable to account for compositional effects in the dynamic of sustained eruptions Detailed studies on sustained phases of explosive eruptions can be done Powerful tool to get insights into the large-scale dynamics of explosive eruptions, especially when coupled to atmospheric dispersion modeling (e. g. , PDAC-2 D, Neri et al. , in press)

• Steady magma flow: Two point boundary value problem • Up-flow (conduit base) boundary condition: Magma chamber pressure Magma composition • Down-flow (conduit exit) boundary condition: Choking (sonic condition), or Atmospheric pressure

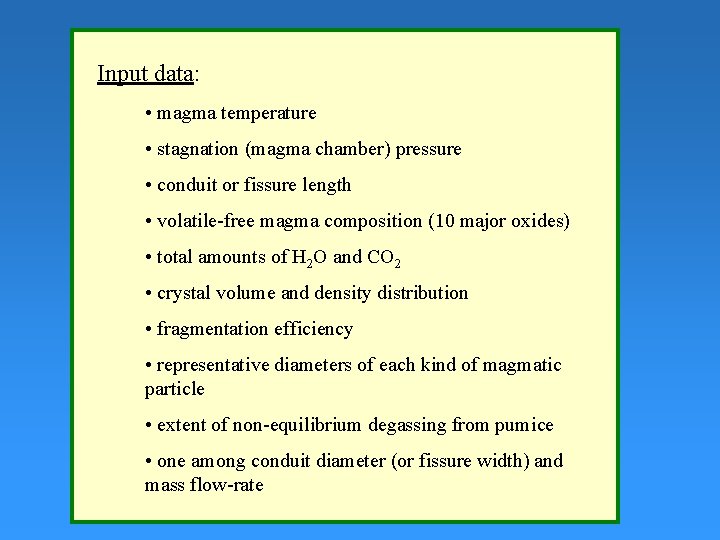

Input data: • magma temperature • stagnation (magma chamber) pressure • conduit or fissure length • volatile-free magma composition (10 major oxides) • total amounts of H 2 O and CO 2 • crystal volume and density distribution • fragmentation efficiency • representative diameters of each kind of magmatic particle • extent of non-equilibrium degassing from pumice • one among conduit diameter (or fissure width) and mass flow-rate

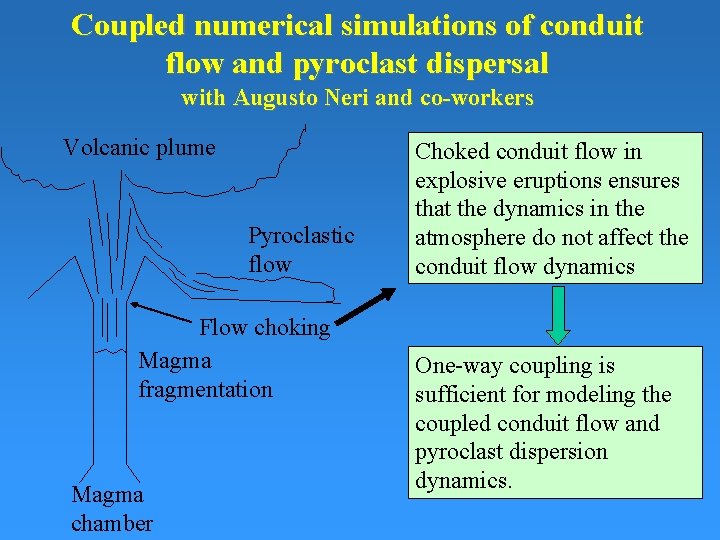

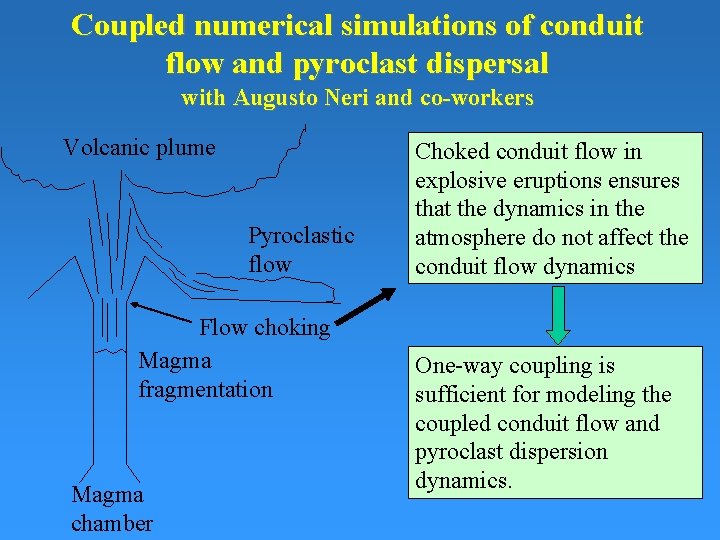

Coupled numerical simulations of conduit flow and pyroclast dispersal with Augusto Neri and co-workers Volcanic plume Pyroclastic flow Flow choking Magma fragmentation Magma chamber Choked conduit flow in explosive eruptions ensures that the dynamics in the atmosphere do not affect the conduit flow dynamics One-way coupling is sufficient for modeling the coupled conduit flow and pyroclast dispersion dynamics.

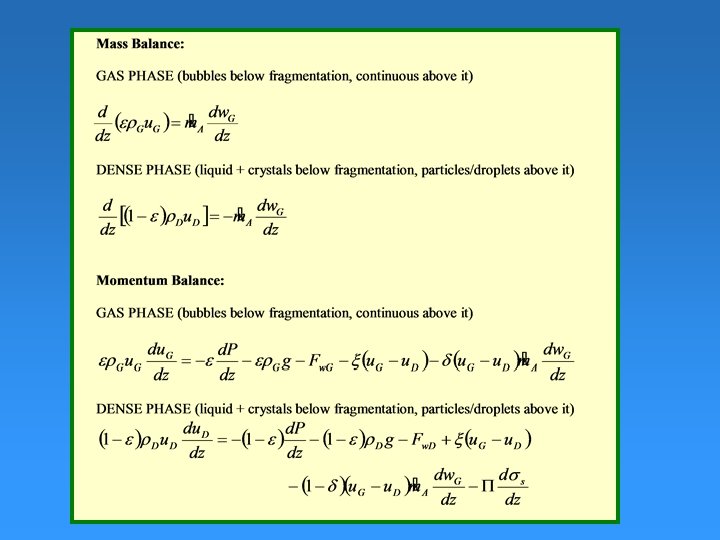

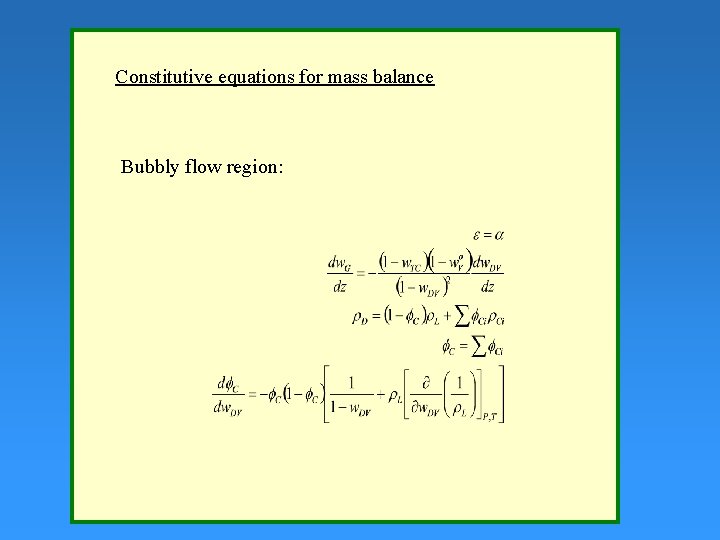

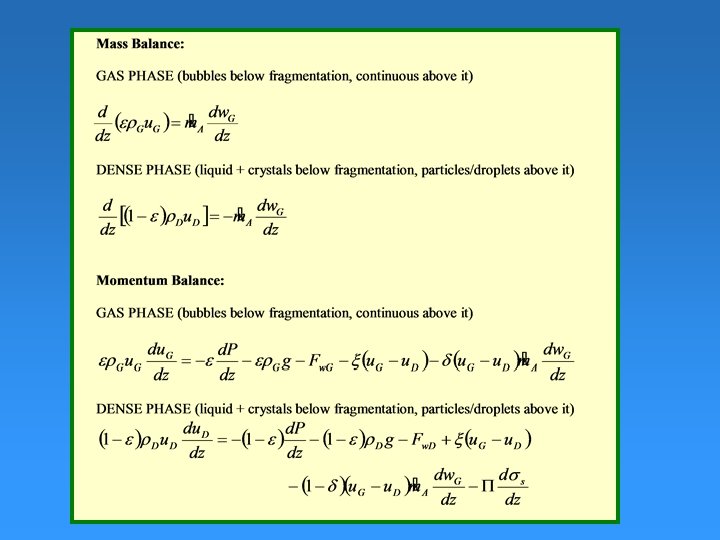

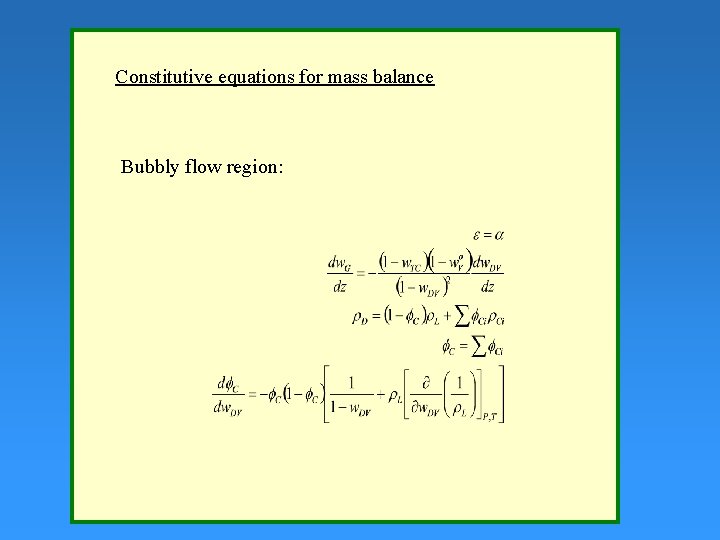

Constitutive equations for mass balance Bubbly flow region:

Constitutive equations for mass balance At fragmentation:

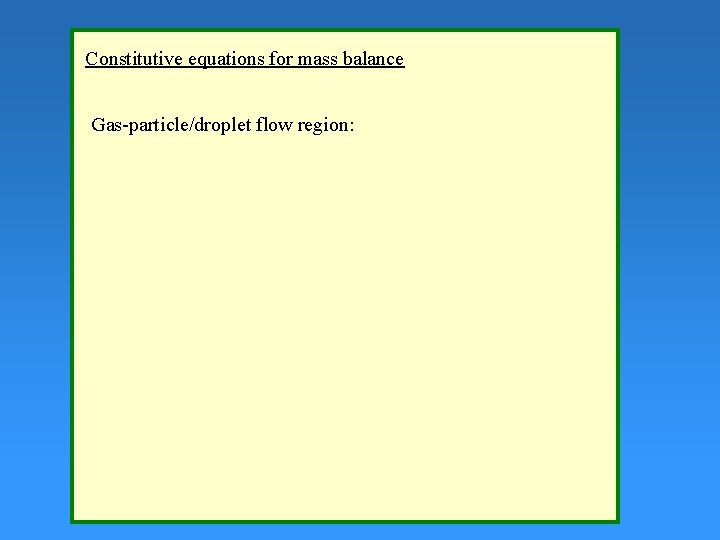

Constitutive equations for mass balance Gas-particle/droplet flow region:

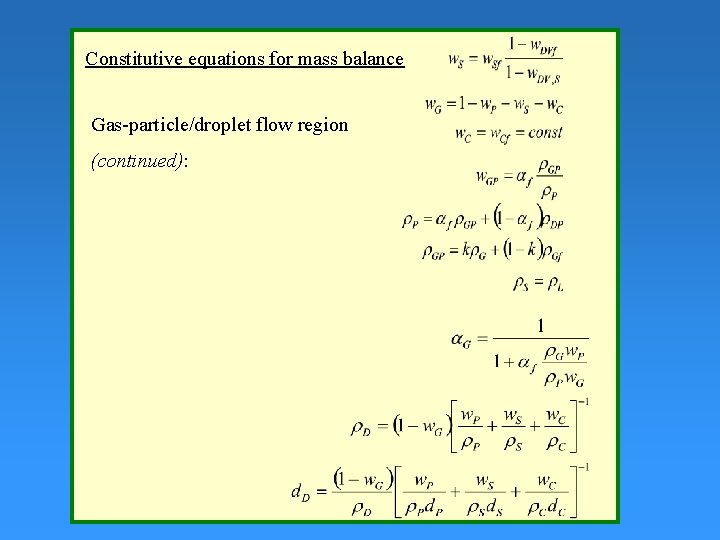

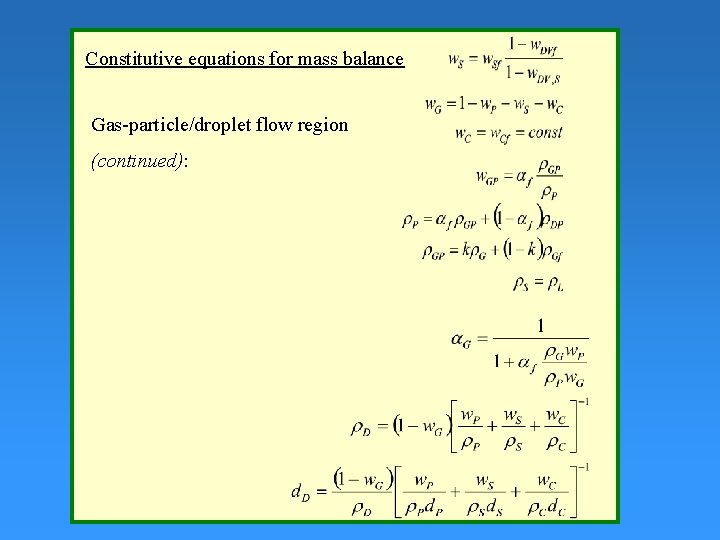

Constitutive equations for mass balance Gas-particle/droplet flow region (continued):

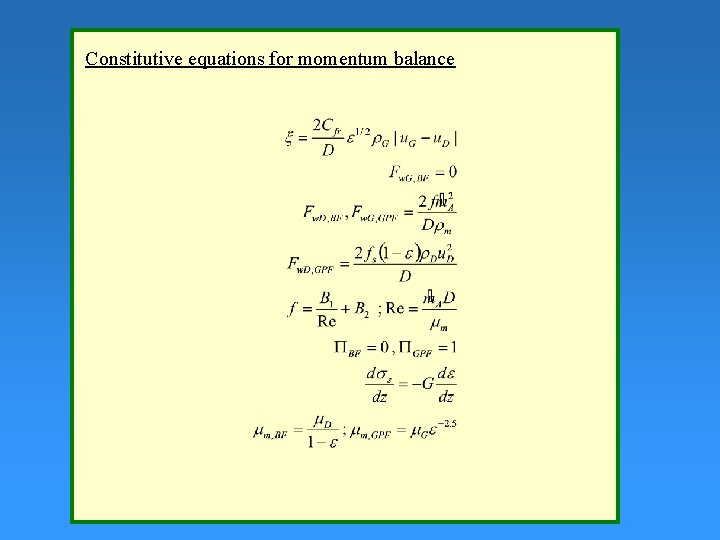

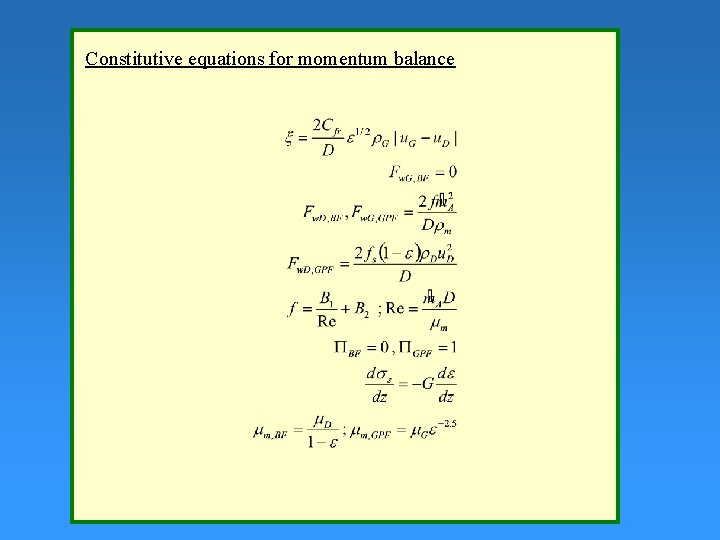

Constitutive equations for momentum balance

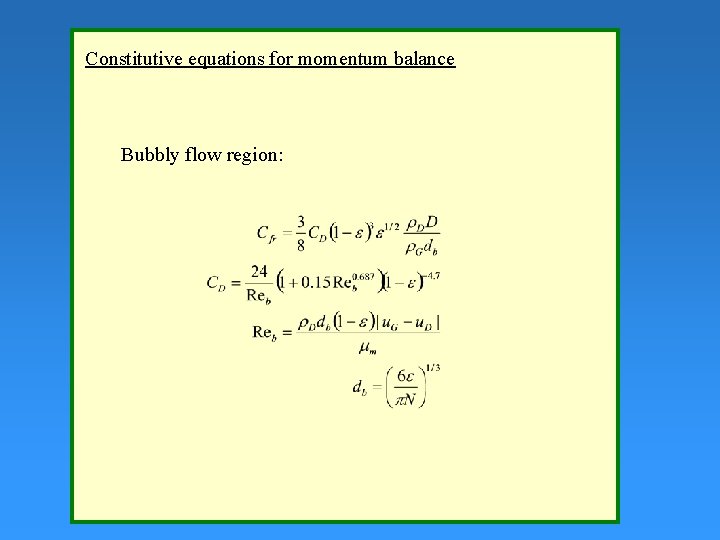

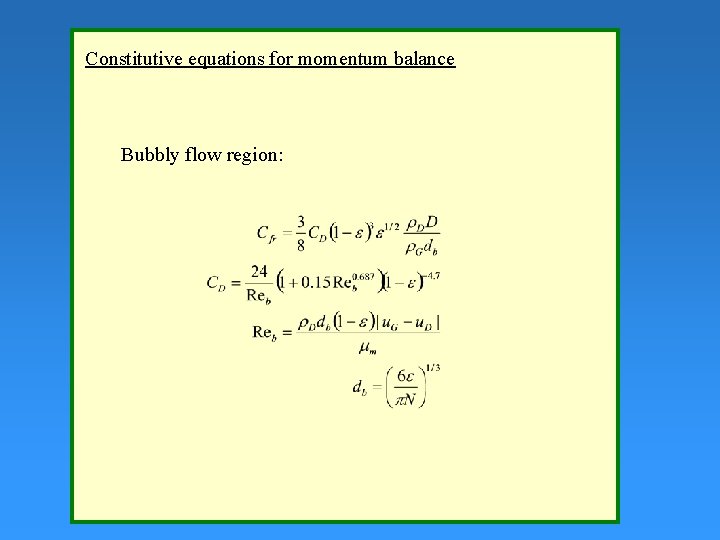

Constitutive equations for momentum balance Bubbly flow region:

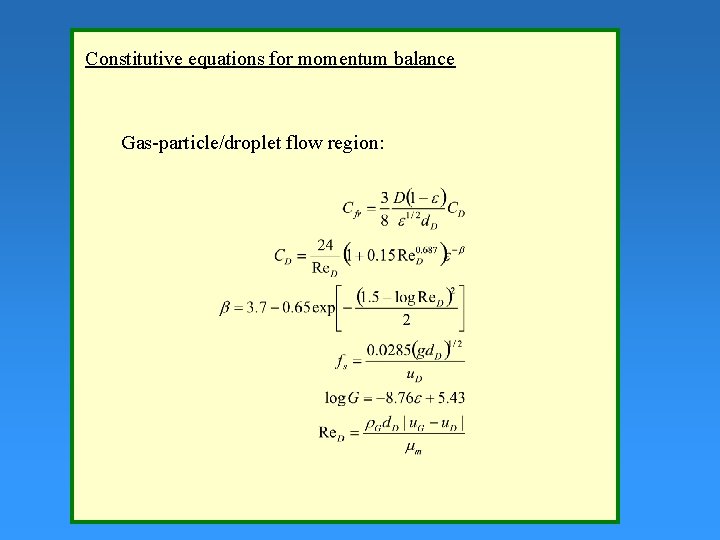

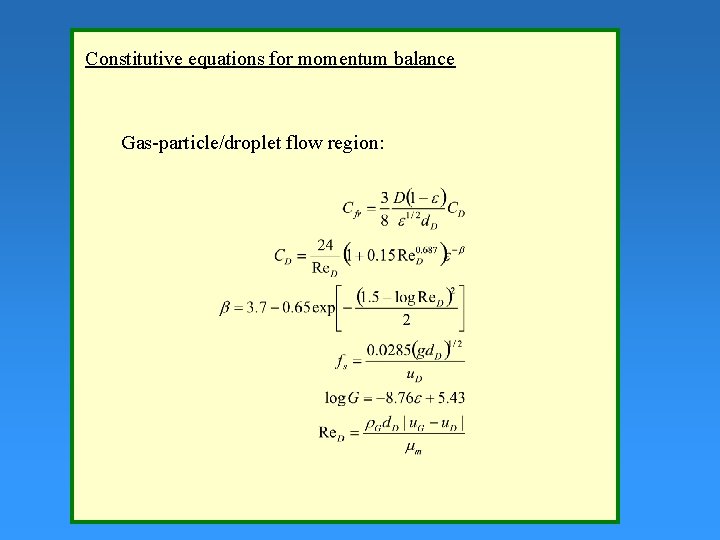

Constitutive equations for momentum balance Gas-particle/droplet flow region: