Concurrency Control Conflict serializability Two phase locking Optimistic

Concurrency Control Conflict serializability Two phase locking Optimistic concurrency control Source: slides by Hector Garcia-Molina 1

Concurrently Executing Transactions T 1 T 2 … Tn DB (consistency constraints) 2

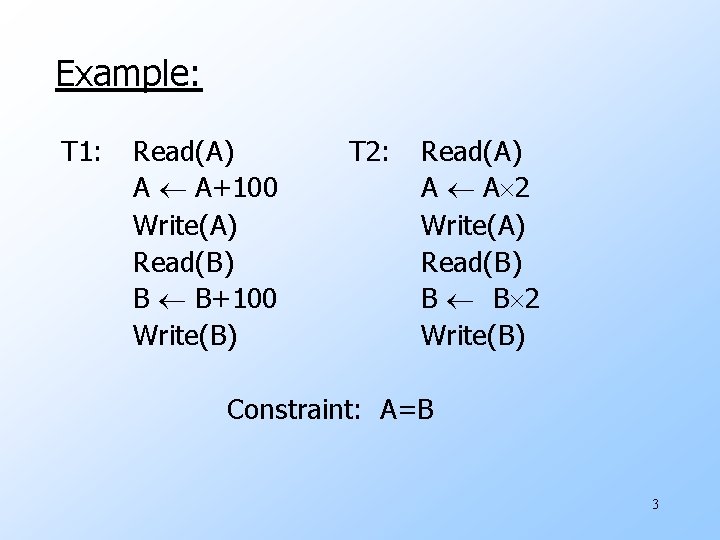

Example: T 1: Read(A) A A+100 Write(A) Read(B) B B+100 Write(B) T 2: Read(A) A A 2 Write(A) Read(B) B B 2 Write(B) Constraint: A=B 3

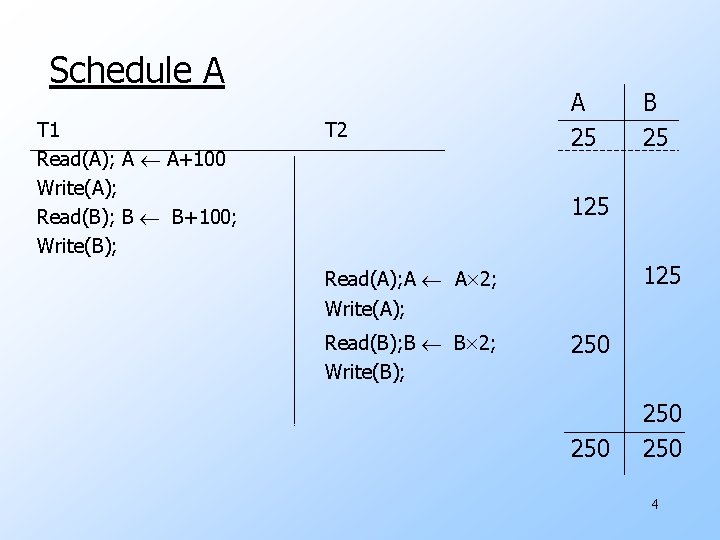

Schedule A T 1 Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); Read(B); B B+100; Write(B); T 2 A 25 B 25 125 Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); 250 250 4

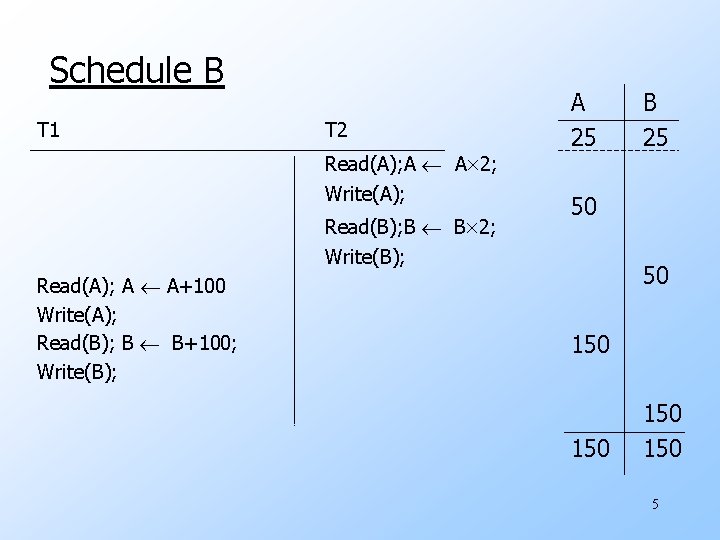

Schedule B T 1 T 2 Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); Read(B); B B+100; Write(B); A 25 B 25 50 50 150 150 5

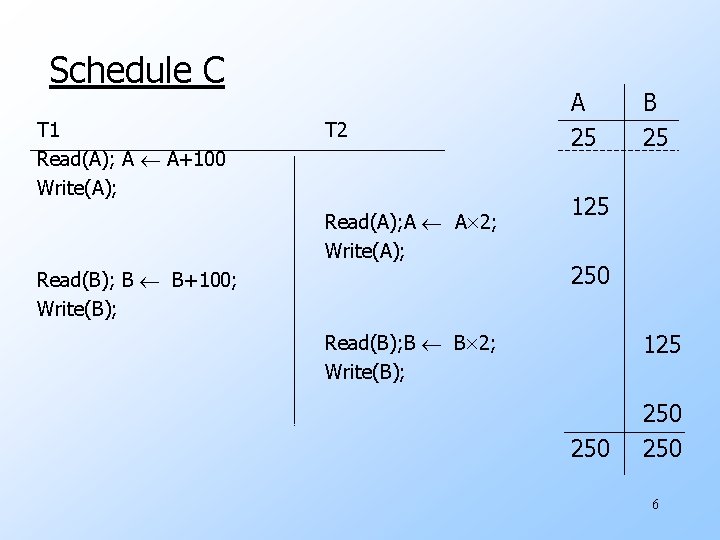

Schedule C T 1 Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); T 2 Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); Read(B); B B+100; Write(B); A 25 B 25 125 250 Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); 125 250 250 6

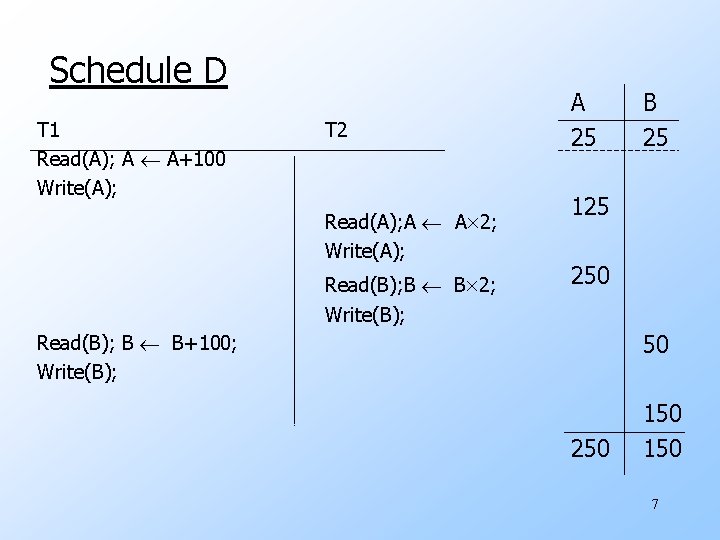

Schedule D T 1 Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); T 2 Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); A 25 B 25 125 250 50 Read(B); B B+100; Write(B); 250 150 7

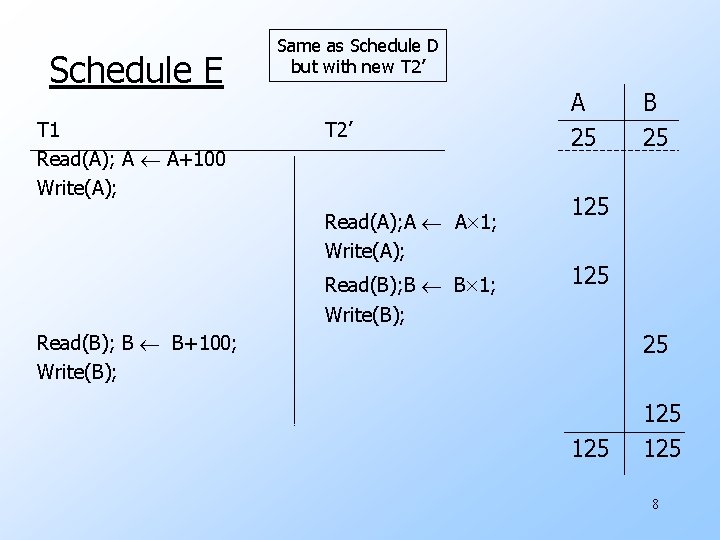

Schedule E T 1 Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); Same as Schedule D but with new T 2’ Read(A); A A 1; Write(A); Read(B); B B 1; Write(B); A 25 B 25 125 25 Read(B); B B+100; Write(B); 125 125 8

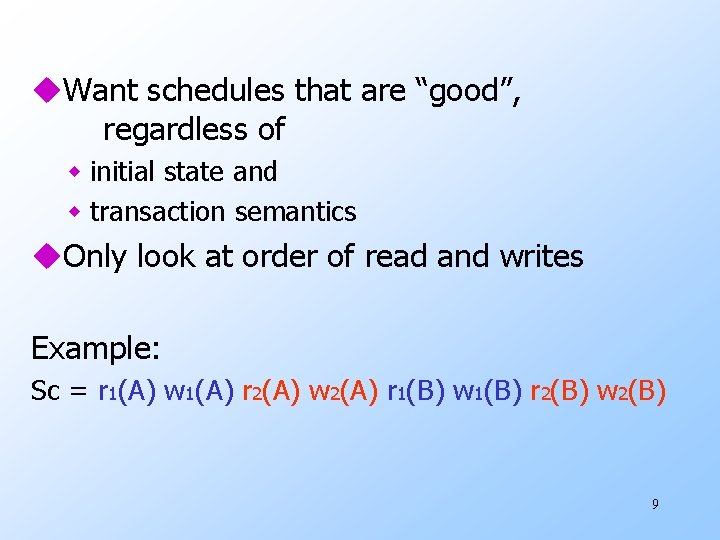

u. Want schedules that are “good”, regardless of w initial state and w transaction semantics u. Only look at order of read and writes Example: Sc = r 1(A) w 1(A) r 2(A) w 2(A) r 1(B) w 1(B) r 2(B) w 2(B) 9

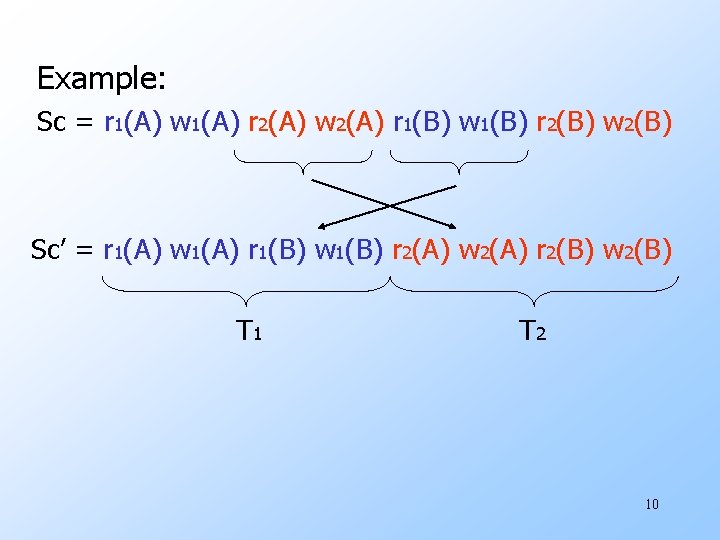

Example: Sc = r 1(A) w 1(A) r 2(A) w 2(A) r 1(B) w 1(B) r 2(B) w 2(B) Sc’ = r 1(A) w 1(A) r 1(B) w 1(B) r 2(A) w 2(A) r 2(B) w 2(B) T 1 T 2 10

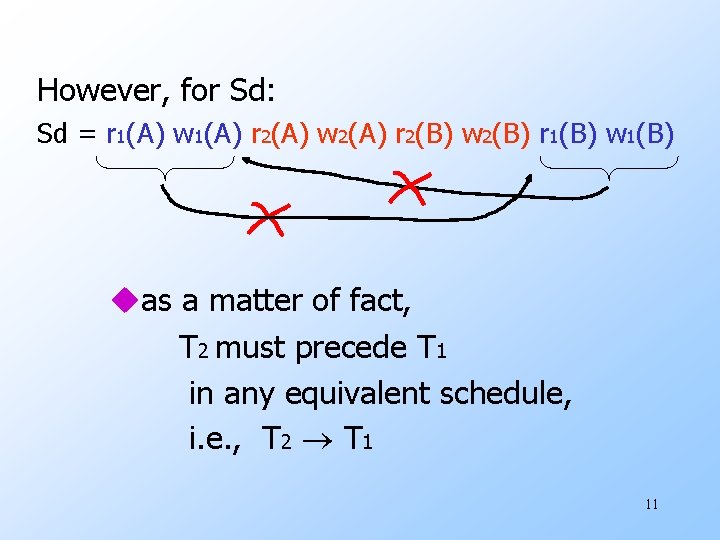

However, for Sd: Sd = r 1(A) w 1(A) r 2(A) w 2(A) r 2(B) w 2(B) r 1(B) w 1(B) uas a matter of fact, T 2 must precede T 1 in any equivalent schedule, i. e. , T 2 T 1 11

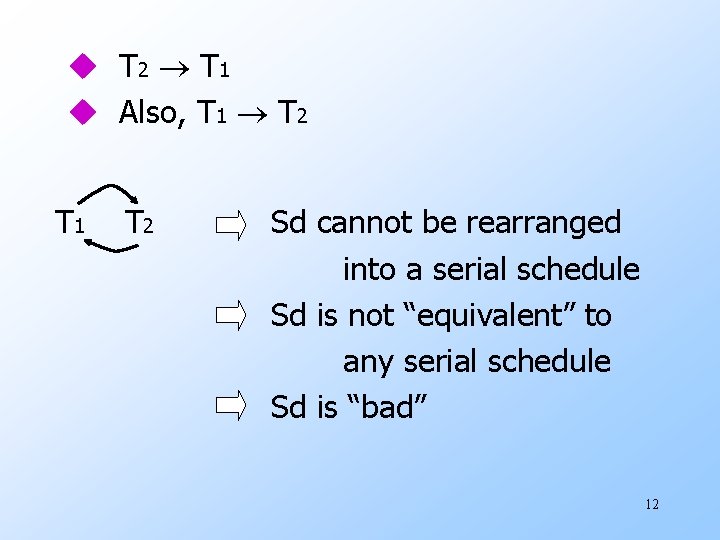

u T 2 T 1 u Also, T 1 T 2 T 1 T 2 Sd cannot be rearranged into a serial schedule Sd is not “equivalent” to any serial schedule Sd is “bad” 12

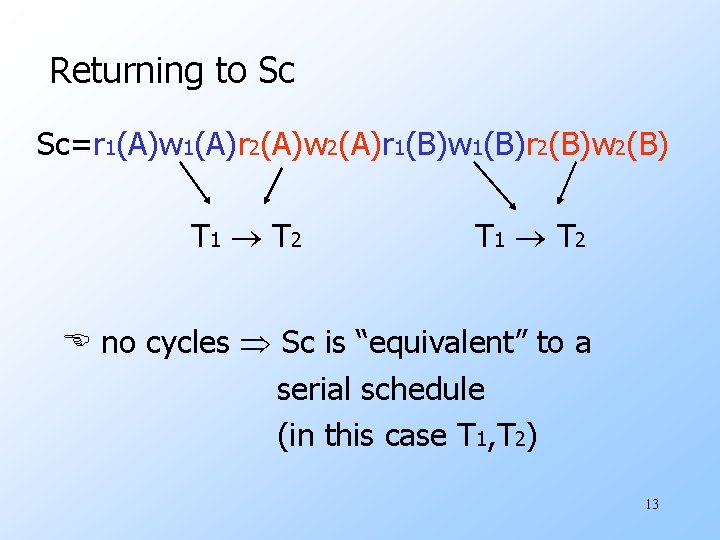

Returning to Sc Sc=r 1(A)w 1(A)r 2(A)w 2(A)r 1(B)w 1(B)r 2(B)w 2(B) T 1 T 2 no cycles Sc is “equivalent” to a serial schedule (in this case T 1, T 2) 13

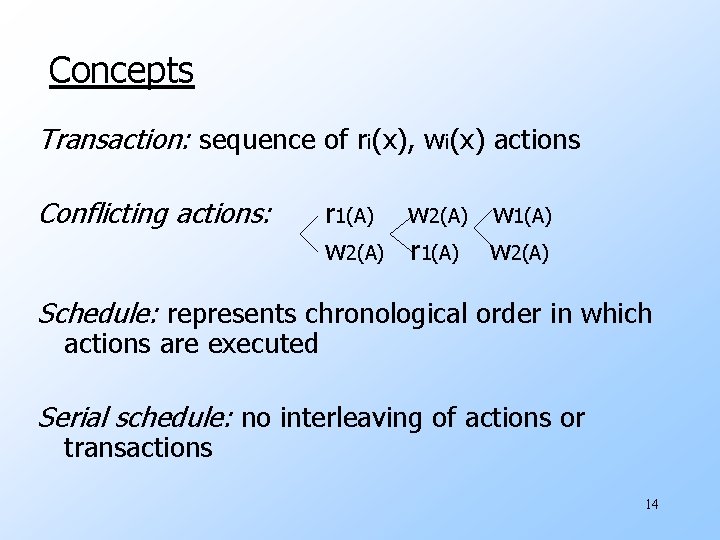

Concepts Transaction: sequence of ri(x), wi(x) actions Conflicting actions: r 1(A) w 2(A) w 1(A) w 2(A) r 1(A) w 2(A) Schedule: represents chronological order in which actions are executed Serial schedule: no interleaving of actions or transactions 14

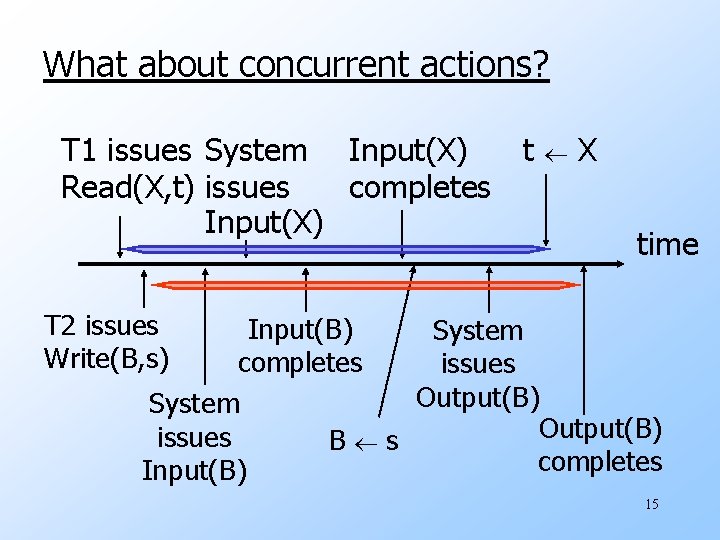

What about concurrent actions? T 1 issues System Input(X) t Read(X, t) issues completes Input(X) X time T 2 issues Write(B, s) Input(B) System completes issues Output(B) System Output(B) issues B s completes Input(B) 15

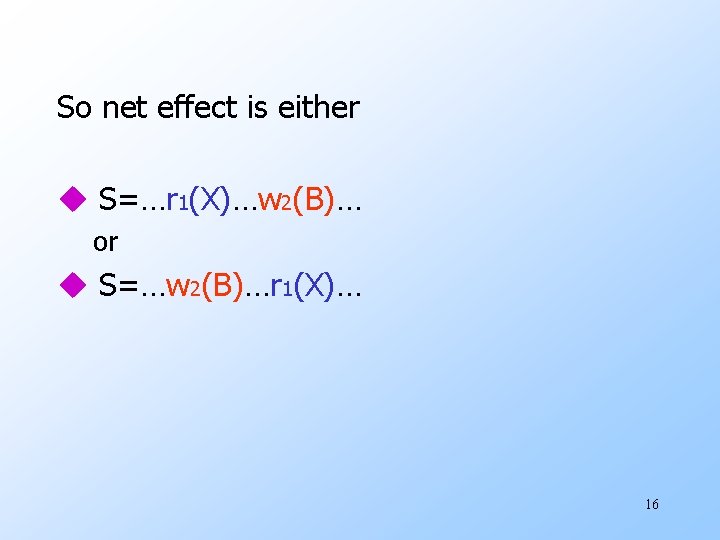

So net effect is either u S=…r 1(X)…w 2(B)… or u S=…w 2(B)…r 1(X)… 16

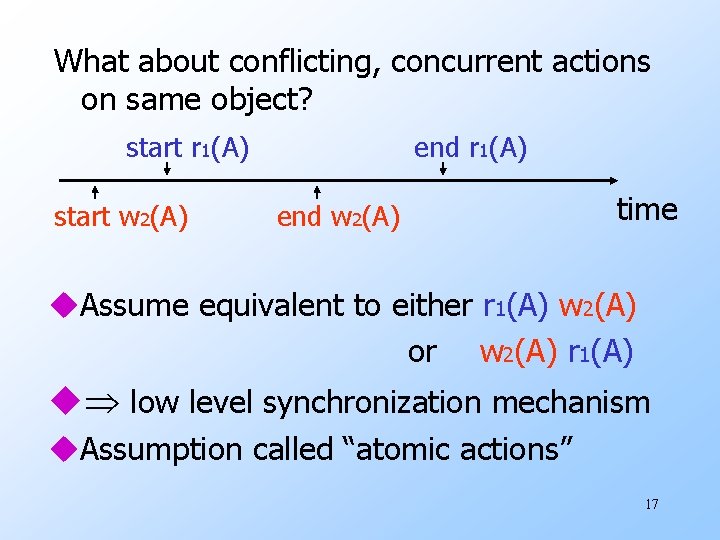

What about conflicting, concurrent actions on same object? start r 1(A) start w 2(A) end r 1(A) end w 2(A) time u. Assume equivalent to either r 1(A) w 2(A) or w 2(A) r 1(A) u low level synchronization mechanism u. Assumption called “atomic actions” 17

Definition S 1, S 2 are conflict equivalent schedules if S 1 can be transformed into S 2 by a series of swaps on non-conflicting actions. 18

Definition A schedule is conflict serializable if it is conflict equivalent to some serial schedule. 19

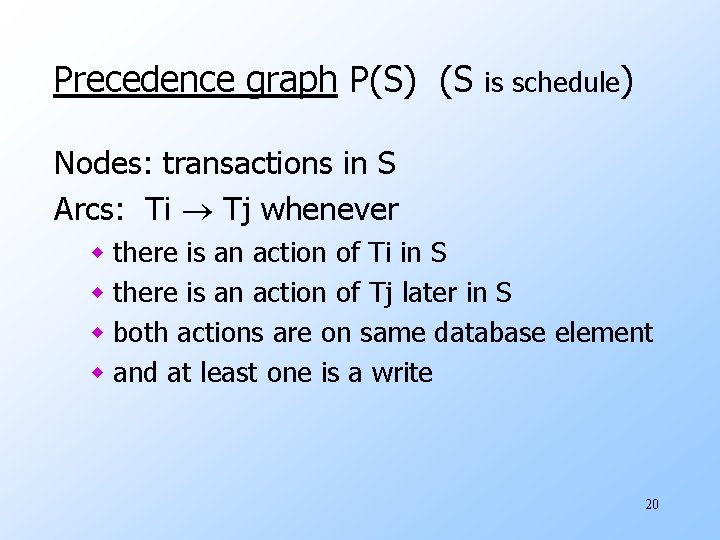

Precedence graph P(S) (S is schedule) Nodes: transactions in S Arcs: Ti Tj whenever w there is an action of Ti in S w there is an action of Tj later in S w both actions are on same database element w and at least one is a write 20

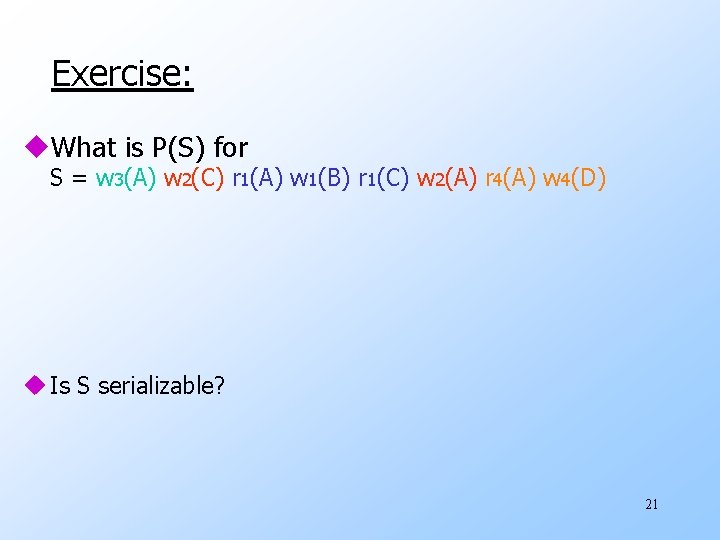

Exercise: u. What is P(S) for S = w 3(A) w 2(C) r 1(A) w 1(B) r 1(C) w 2(A) r 4(A) w 4(D) u Is S serializable? 21

Another Exercise: u. What is P(S) for S = w 1(A) r 2(A) r 3(A) w 4(A) ? 22

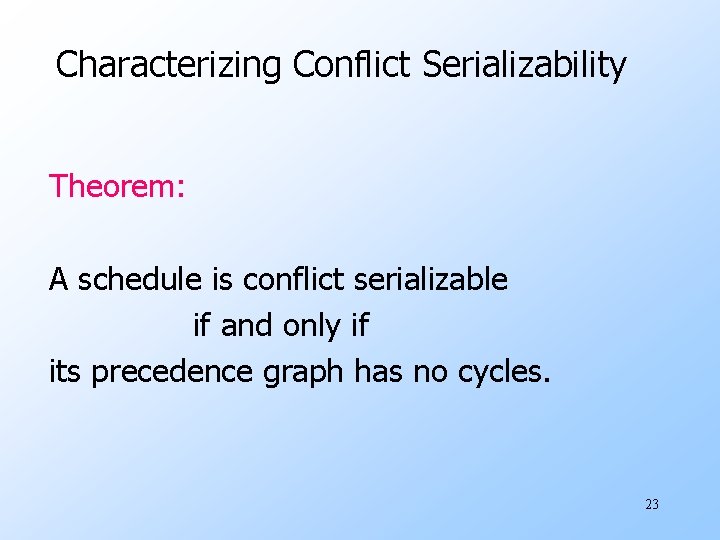

Characterizing Conflict Serializability Theorem: A schedule is conflict serializable if and only if its precedence graph has no cycles. 23

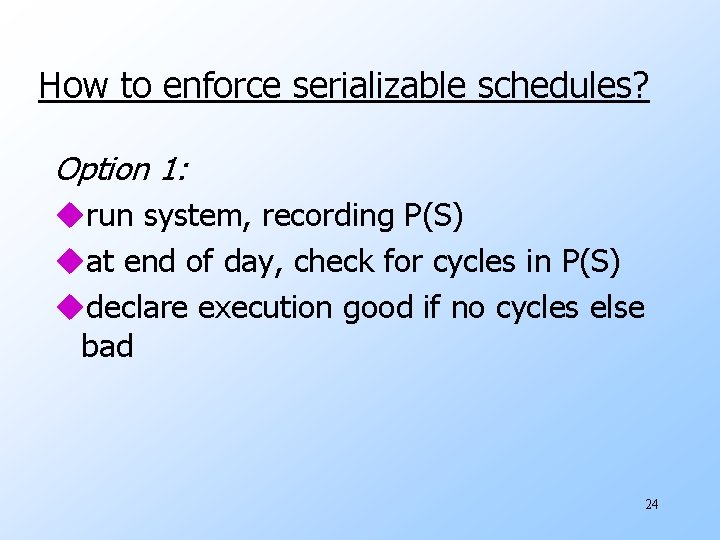

How to enforce serializable schedules? Option 1: urun system, recording P(S) uat end of day, check for cycles in P(S) udeclare execution good if no cycles else bad 24

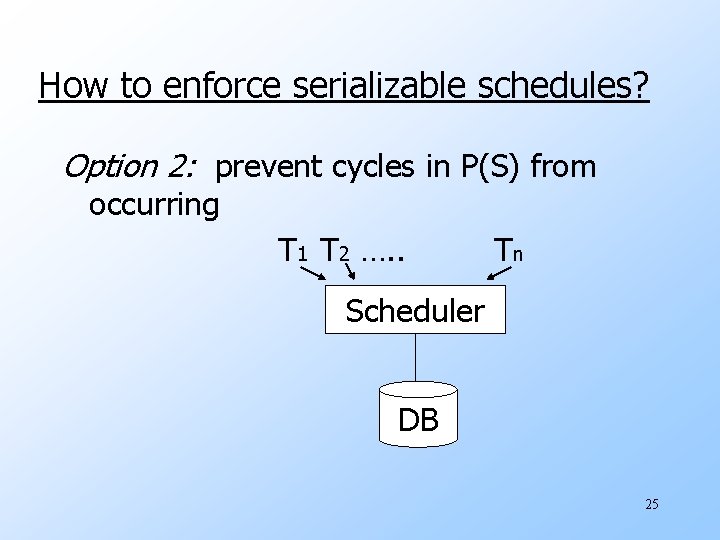

How to enforce serializable schedules? Option 2: prevent cycles in P(S) from occurring T 1 T 2 …. . Tn Scheduler DB 25

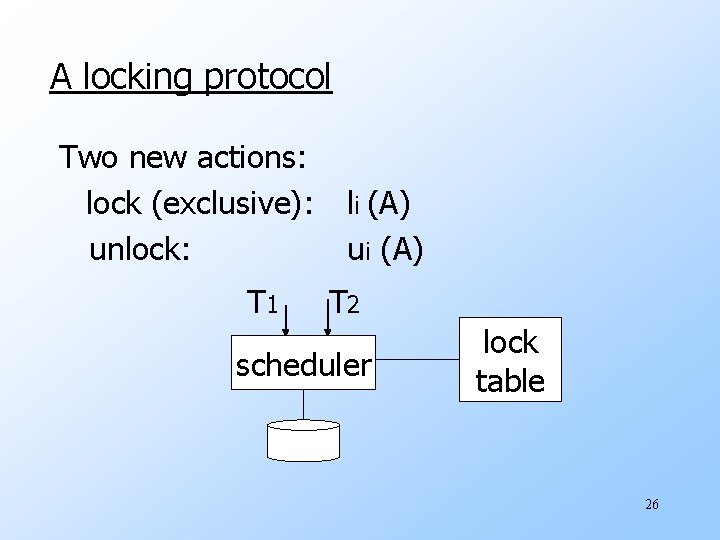

A locking protocol Two new actions: lock (exclusive): unlock: T 1 li (A) ui (A) T 2 scheduler lock table 26

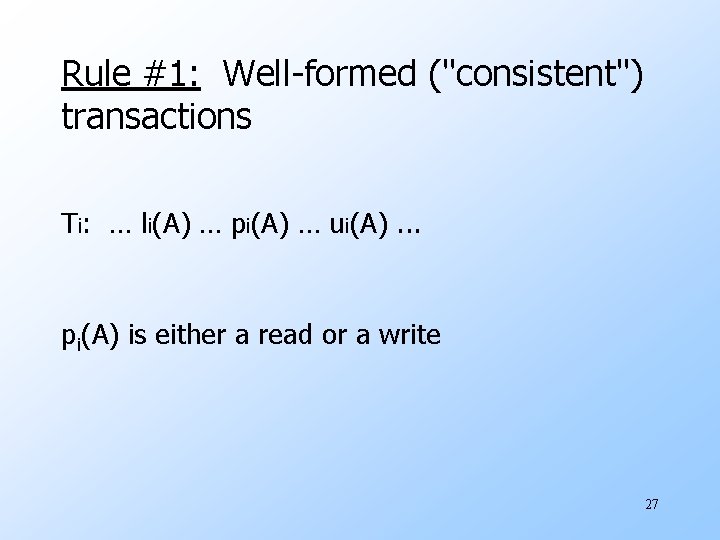

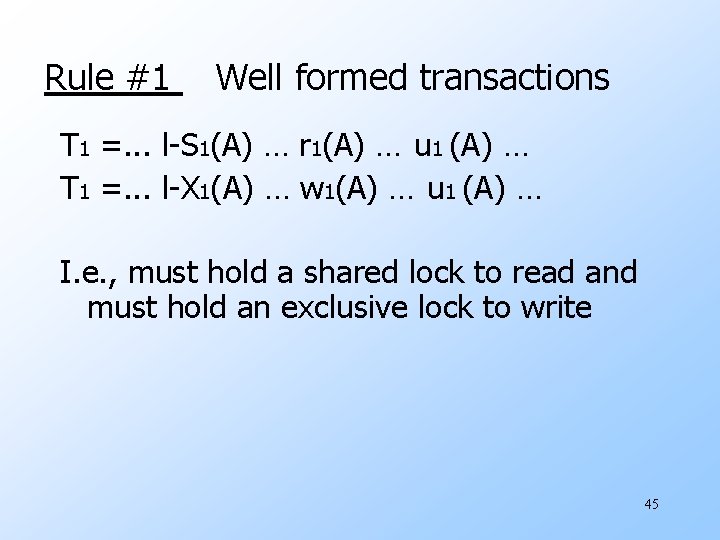

Rule #1: Well-formed ("consistent") transactions Ti: … li(A) … pi(A) … ui(A). . . pi(A) is either a read or a write 27

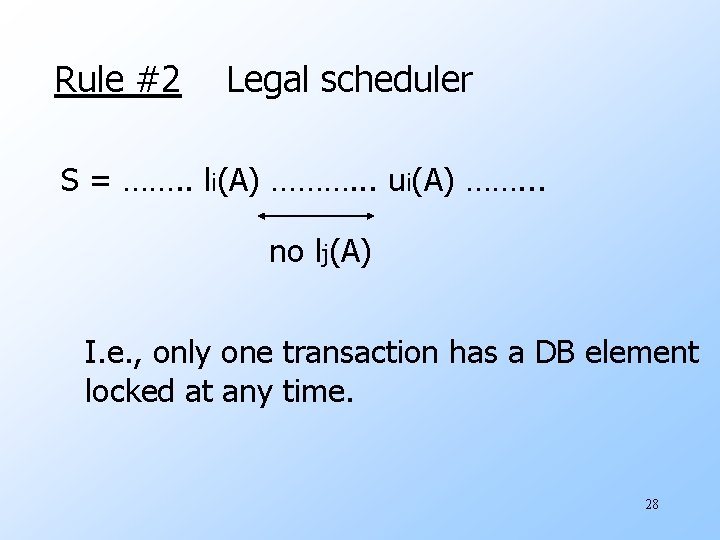

Rule #2 Legal scheduler S = ……. . li(A) ………. . . ui(A) ……. . . no lj(A) I. e. , only one transaction has a DB element locked at any time. 28

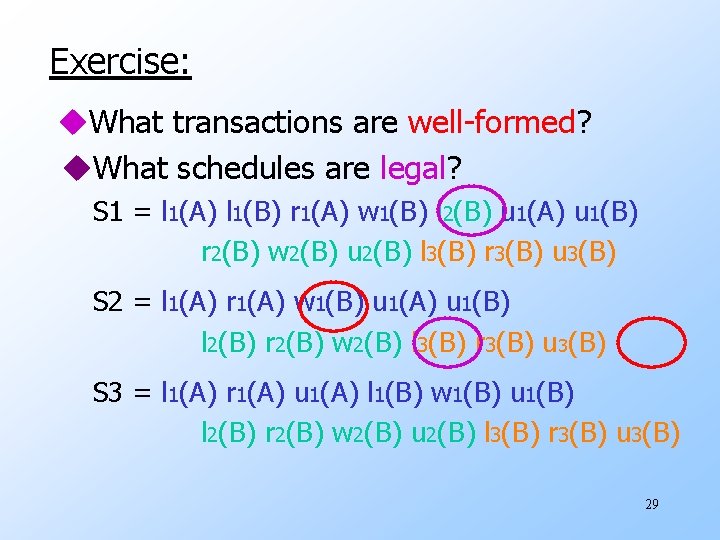

Exercise: u. What transactions are well-formed? u. What schedules are legal? S 1 = l 1(A) l 1(B) r 1(A) w 1(B) l 2(B) u 1(A) u 1(B) r 2(B) w 2(B) u 2(B) l 3(B) r 3(B) u 3(B) S 2 = l 1(A) r 1(A) w 1(B) u 1(A) u 1(B) l 2(B) r 2(B) w 2(B) l 3(B) r 3(B) u 3(B) S 3 = l 1(A) r 1(A) u 1(A) l 1(B) w 1(B) u 1(B) l 2(B) r 2(B) w 2(B) u 2(B) l 3(B) r 3(B) u 3(B) 29

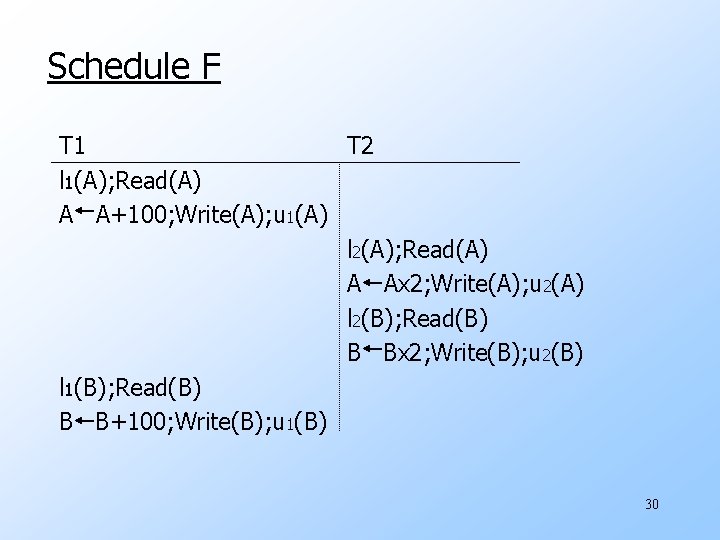

Schedule F T 1 T 2 l 1(A); Read(A) A A+100; Write(A); u 1(A) l 2(A); Read(A) A Ax 2; Write(A); u 2(A) l 2(B); Read(B) B Bx 2; Write(B); u 2(B) l 1(B); Read(B) B B+100; Write(B); u 1(B) 30

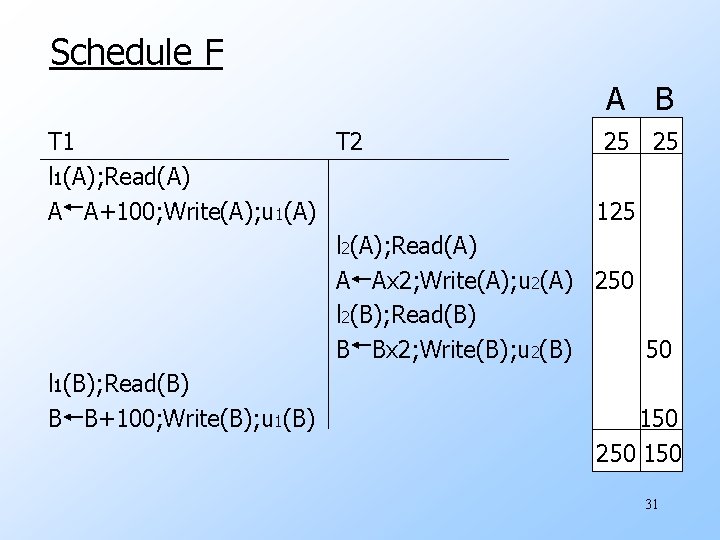

Schedule F A B T 1 T 2 25 25 l 1(A); Read(A) A A+100; Write(A); u 1(A) 125 l 2(A); Read(A) A Ax 2; Write(A); u 2(A) 250 l 2(B); Read(B) B Bx 2; Write(B); u 2(B) 50 l 1(B); Read(B) B B+100; Write(B); u 1(B) 150 250 150 31

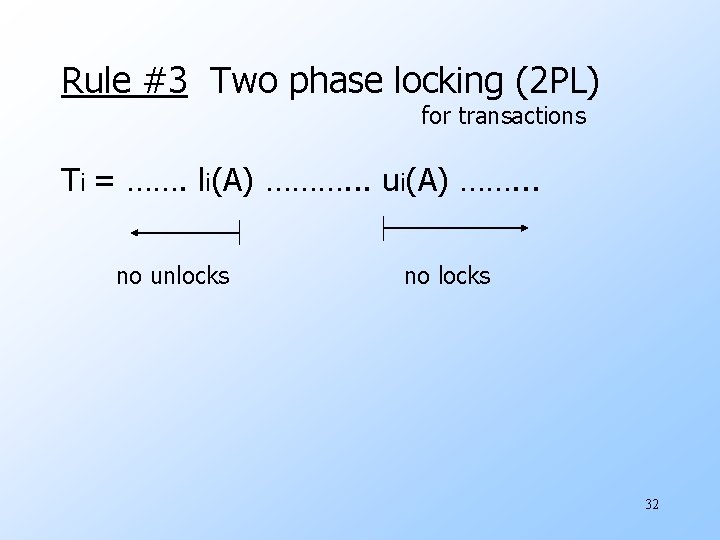

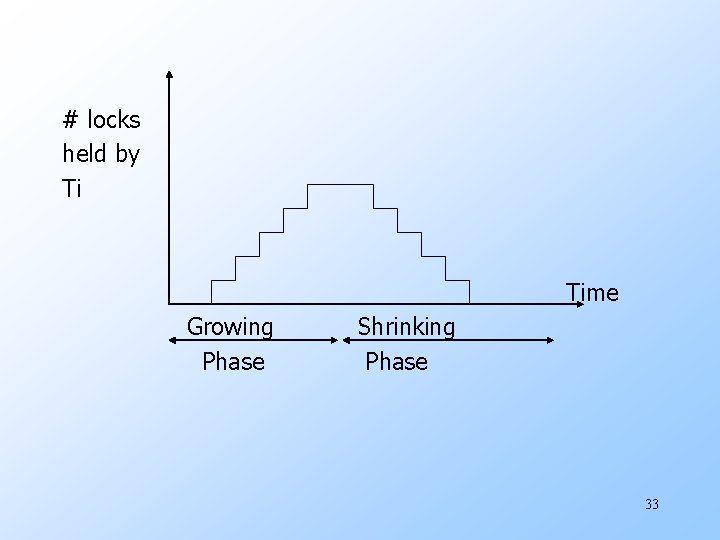

Rule #3 Two phase locking (2 PL) for transactions Ti = ……. li(A) ………. . . ui(A) ……. . . no unlocks no locks 32

# locks held by Ti Time Growing Phase Shrinking Phase 33

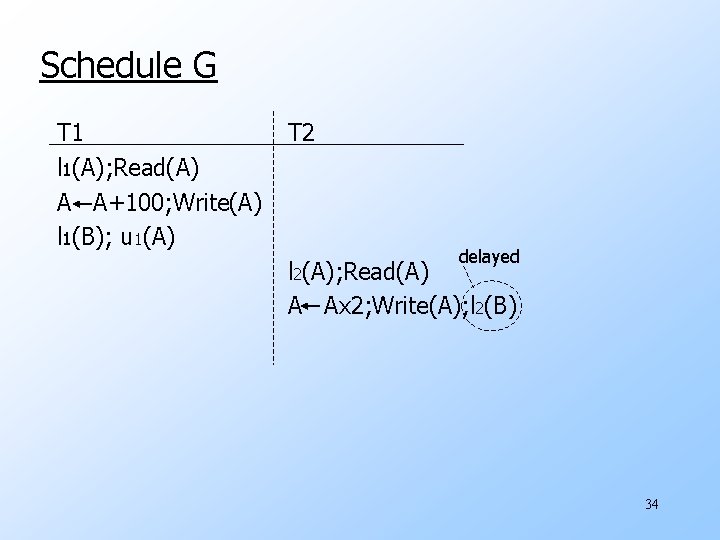

Schedule G T 1 l 1(A); Read(A) A A+100; Write(A) l 1(B); u 1(A) T 2 delayed l 2(A); Read(A) A Ax 2; Write(A); l 2(B) 34

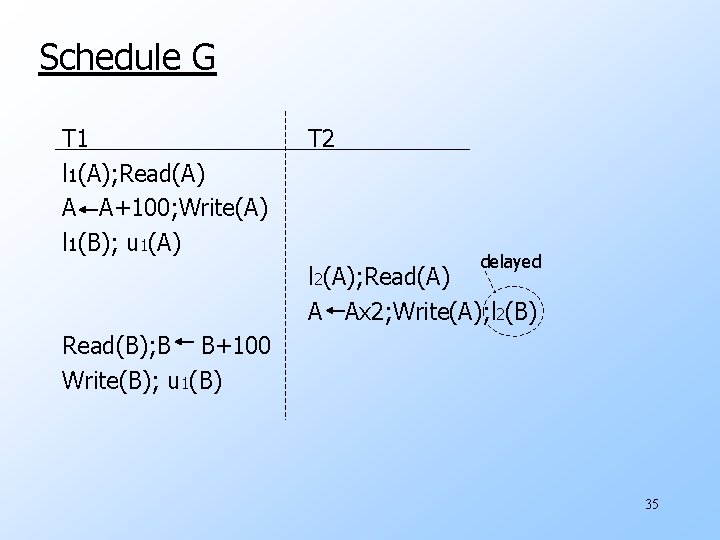

Schedule G T 1 l 1(A); Read(A) A A+100; Write(A) l 1(B); u 1(A) T 2 delayed l 2(A); Read(A) A Ax 2; Write(A); l 2(B) Read(B); B B+100 Write(B); u 1(B) 35

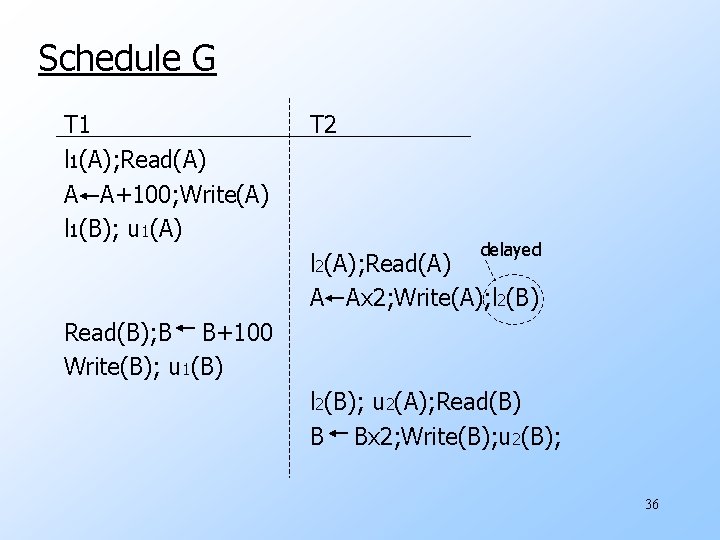

Schedule G T 1 l 1(A); Read(A) A A+100; Write(A) l 1(B); u 1(A) T 2 delayed l 2(A); Read(A) A Ax 2; Write(A); l 2(B) Read(B); B B+100 Write(B); u 1(B) l 2(B); u 2(A); Read(B) B Bx 2; Write(B); u 2(B); 36

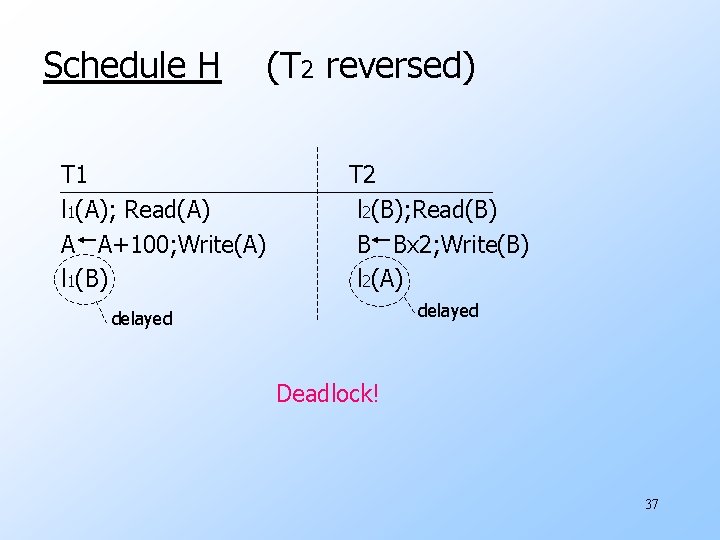

Schedule H (T 2 reversed) T 1 l 1(A); Read(A) A A+100; Write(A) l 1(B) T 2 l 2(B); Read(B) B Bx 2; Write(B) l 2(A) delayed Deadlock! 37

u. Assume deadlocked transactions are rolled back w They have no effect w They do not appear in schedule E. g. , Schedule H = This space intentionally left blank! 38

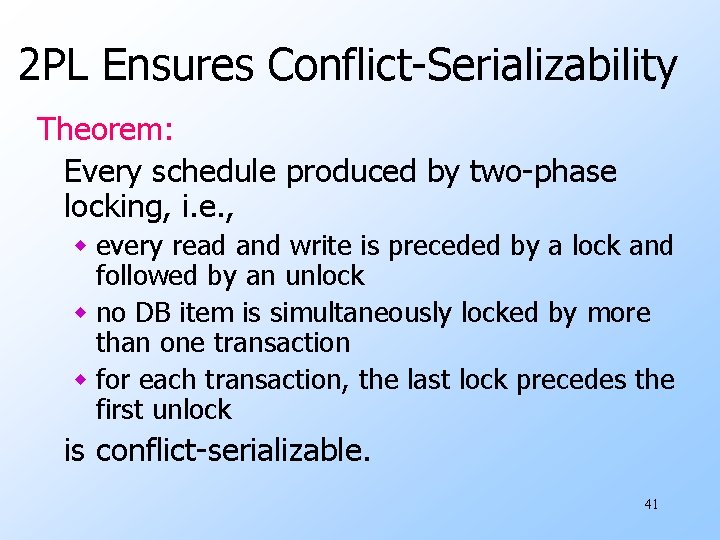

Next step: Show that rules #1, 2, 3 conflictserializable schedules 39

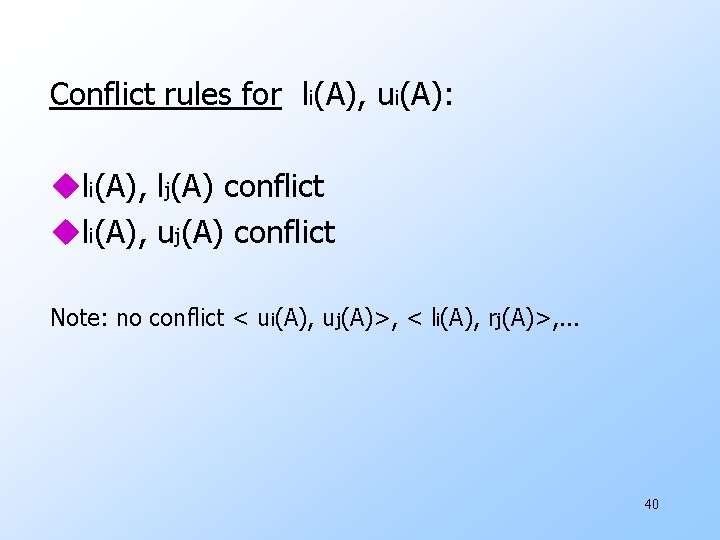

Conflict rules for li(A), ui(A): uli(A), lj(A) conflict uli(A), uj(A) conflict Note: no conflict < ui(A), uj(A)>, < li(A), rj(A)>, . . . 40

2 PL Ensures Conflict-Serializability Theorem: Every schedule produced by two-phase locking, i. e. , w every read and write is preceded by a lock and followed by an unlock w no DB item is simultaneously locked by more than one transaction w for each transaction, the last lock precedes the first unlock is conflict-serializable. 41

u. Beyond this simple 2 PL protocol, it is all a matter of improving performance and allowing more concurrency…. w Shared locks w Increment locks w Multiple granularity w Other types of concurrency control mechanisms 42

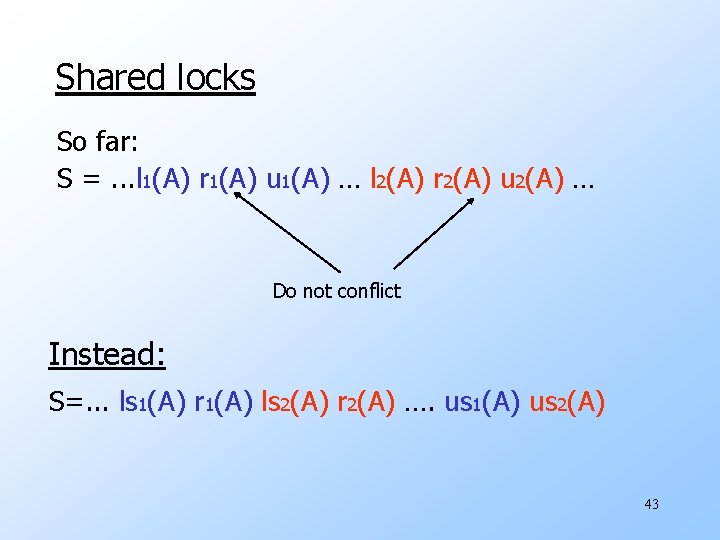

Shared locks So far: S =. . . l 1(A) r 1(A) u 1(A) … l 2(A) r 2(A) u 2(A) … Do not conflict Instead: S=. . . ls 1(A) r 1(A) ls 2(A) r 2(A) …. us 1(A) us 2(A) 43

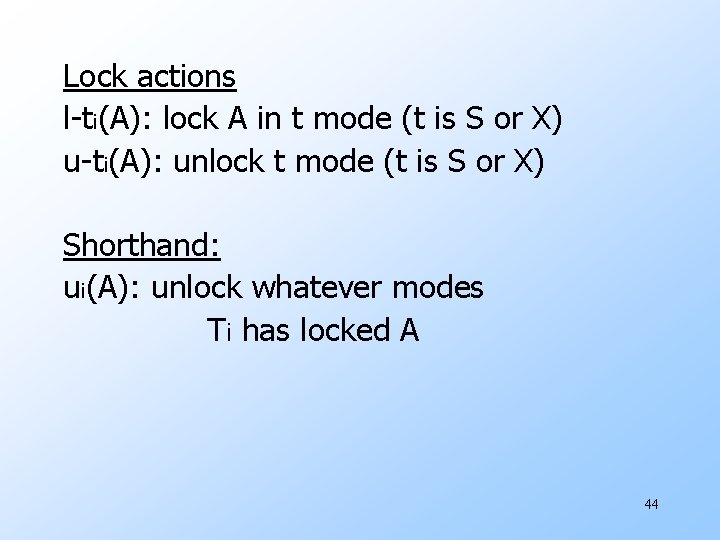

Lock actions l-ti(A): lock A in t mode (t is S or X) u-ti(A): unlock t mode (t is S or X) Shorthand: ui(A): unlock whatever modes Ti has locked A 44

Rule #1 Well formed transactions T 1 =. . . l-S 1(A) … r 1(A) … u 1 (A) … T 1 =. . . l-X 1(A) … w 1(A) … u 1 (A) … I. e. , must hold a shared lock to read and must hold an exclusive lock to write 45

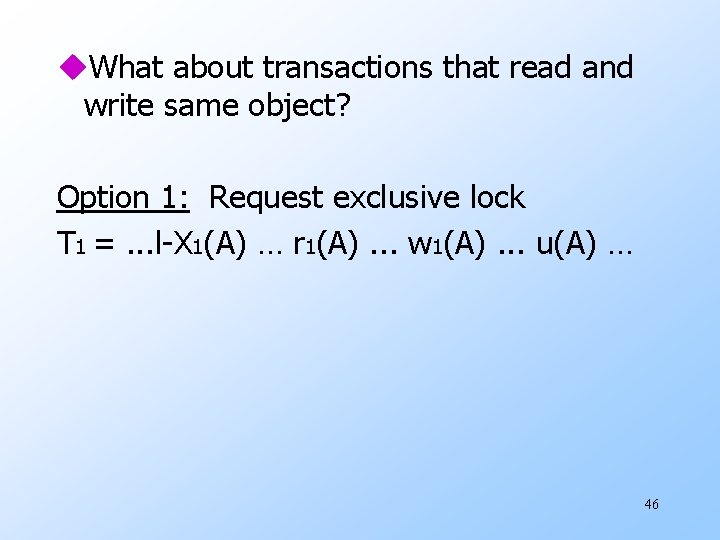

u. What about transactions that read and write same object? Option 1: Request exclusive lock T 1 =. . . l-X 1(A) … r 1(A). . . w 1(A). . . u(A) … 46

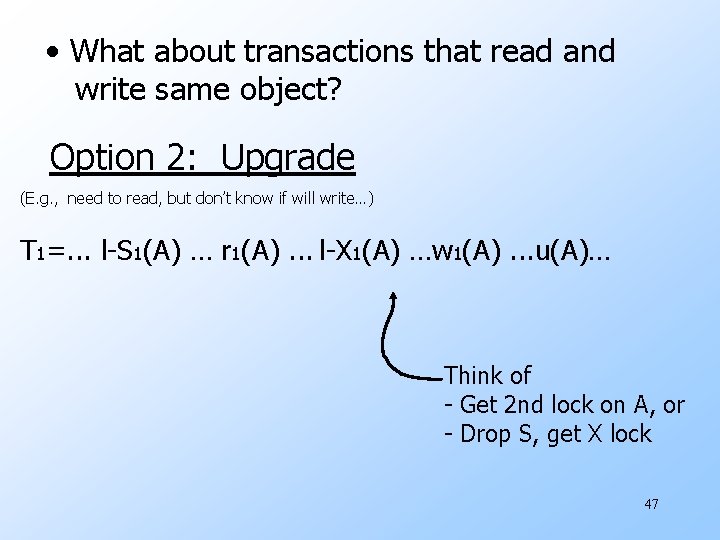

• What about transactions that read and write same object? Option 2: Upgrade (E. g. , need to read, but don’t know if will write…) T 1=. . . l-S 1(A) … r 1(A). . . l-X 1(A) …w 1(A). . . u(A)… Think of - Get 2 nd lock on A, or - Drop S, get X lock 47

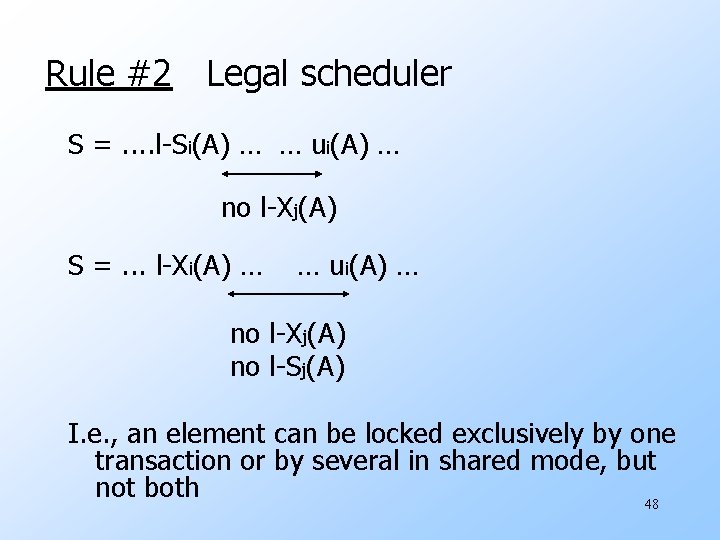

Rule #2 Legal scheduler S =. . l-Si(A) … … ui(A) … no l-Xj(A) S =. . . l-Xi(A) … … ui(A) … no l-Xj(A) no l-Sj(A) I. e. , an element can be locked exclusively by one transaction or by several in shared mode, but not both 48

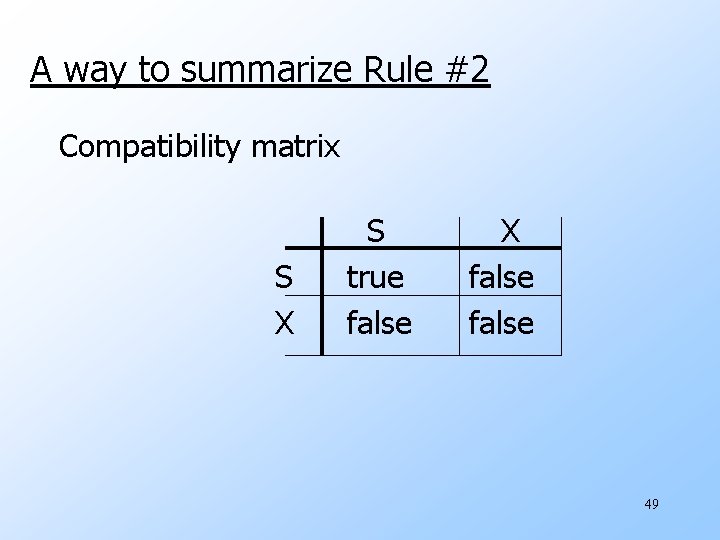

A way to summarize Rule #2 Compatibility matrix S X S true false X false 49

Rule # 3 2 PL transactions No change except for upgrades: (I) If upgrade gets more locks (e. g. , S {S, X}) then no change! (II) If upgrade releases read (shared) lock (e. g. , S X) - can be allowed in growing phase 50

2 PL Ensures Conflict. Serializability With Shared Locks Theorem: Every schedule produced by two-phase locking, modified to handle shared locks, is conflict-serializable. 51

Lock types beyond S/X Examples: (1) increment lock (2) update lock 52

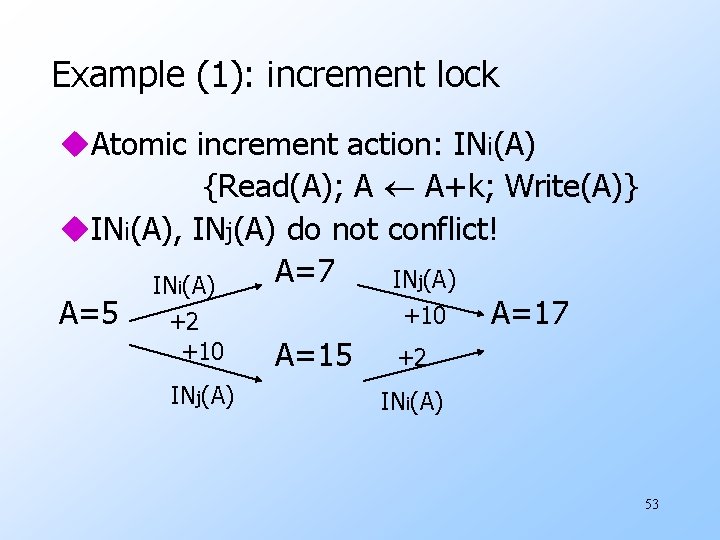

Example (1): increment lock u. Atomic increment action: INi(A) {Read(A); A A+k; Write(A)} u. INi(A), INj(A) do not conflict! A=7 INj(A) INi(A) A=5 A=17 +10 +2 +10 A=15 +2 INj(A) INi(A) 53

Compatibility Matrix S X I 54

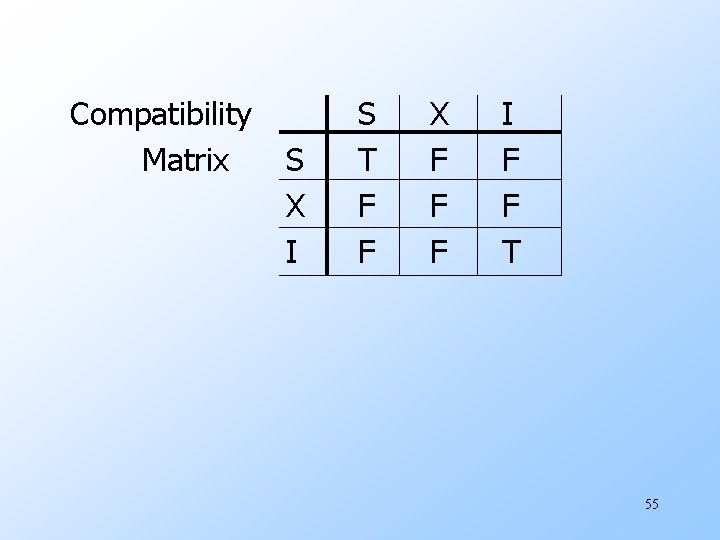

Compatibility Matrix S X I S T F F X F F F I F F T 55

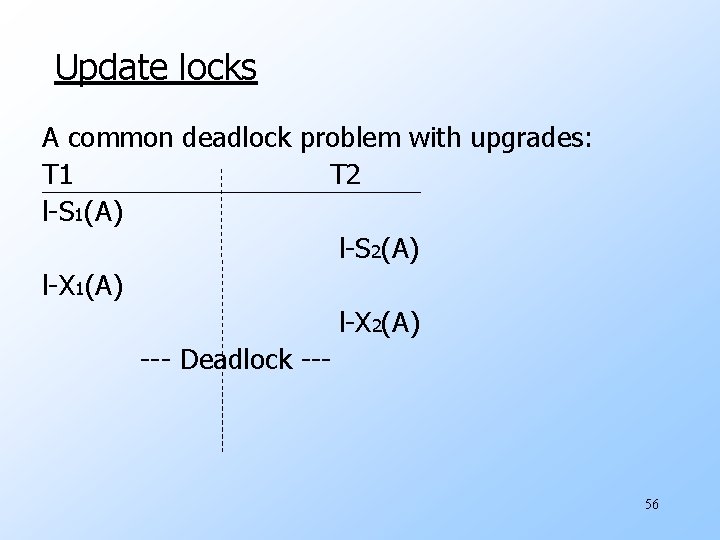

Update locks A common deadlock problem with upgrades: T 1 T 2 l-S 1(A) l-S 2(A) l-X 1(A) l-X 2(A) --- Deadlock --- 56

Solution If Ti wants to read A and knows it may later want to write A, it requests update lock (not shared) 57

New request Comp. Matrix Lock already held in S X U 58

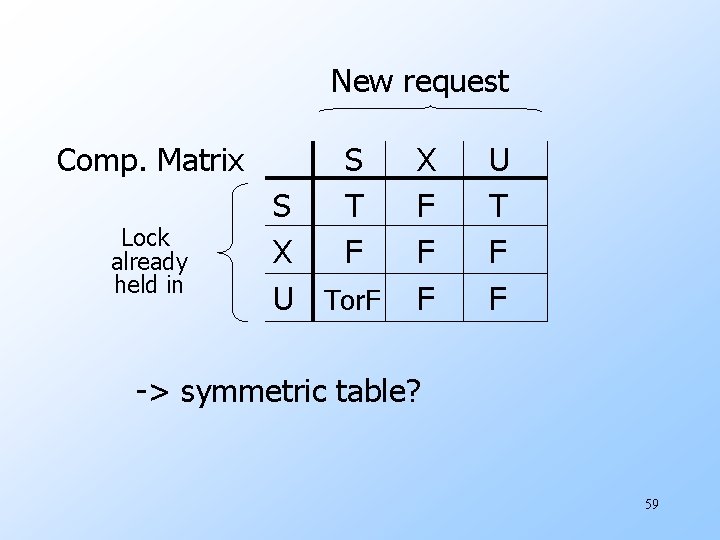

New request Comp. Matrix Lock already held in S T F S X U Tor. F X F F F U T F F -> symmetric table? 59

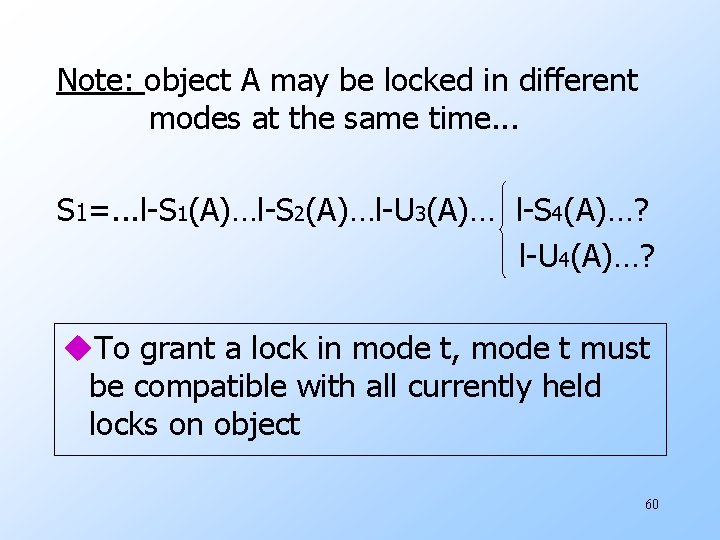

Note: object A may be locked in different modes at the same time. . . S 1=. . . l-S 1(A)…l-S 2(A)…l-U 3(A)… l-S 4(A)…? l-U 4(A)…? u. To grant a lock in mode t, mode t must be compatible with all currently held locks on object 60

How does locking work in practice? u. Every system is different (E. g. , may not even provide CONFLICT-SERIALIZABLE schedules) u. But here is one (simplified) way. . . 61

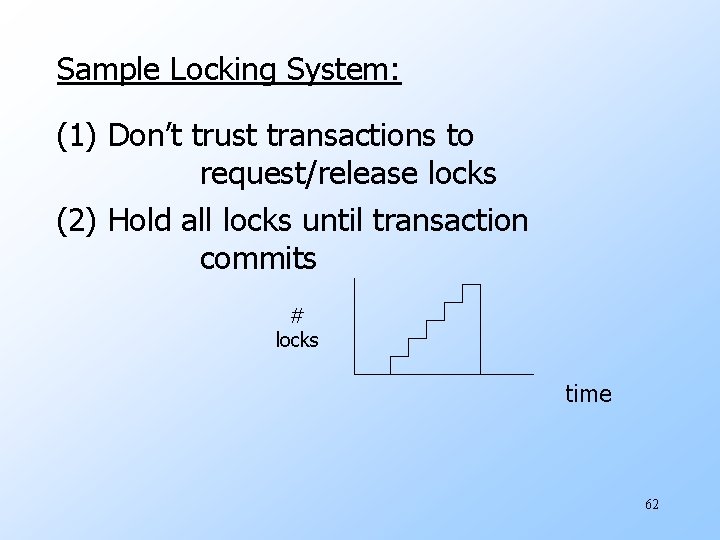

Sample Locking System: (1) Don’t trust transactions to request/release locks (2) Hold all locks until transaction commits # locks time 62

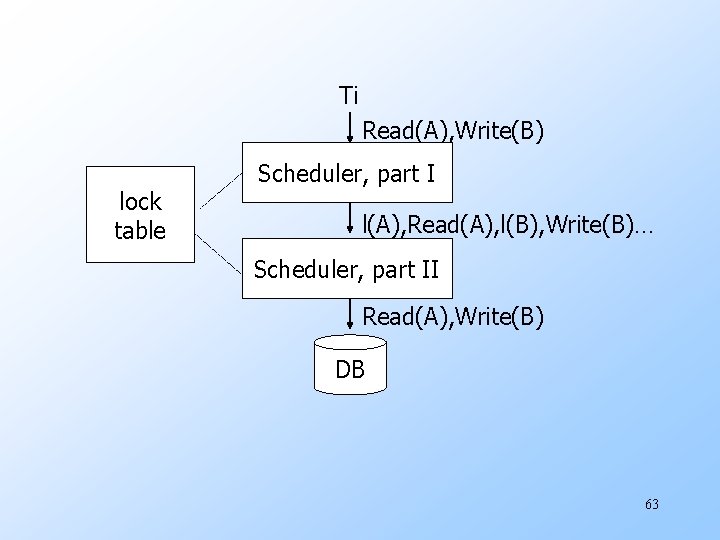

Ti Read(A), Write(B) lock table Scheduler, part I l(A), Read(A), l(B), Write(B)… Scheduler, part II Read(A), Write(B) DB 63

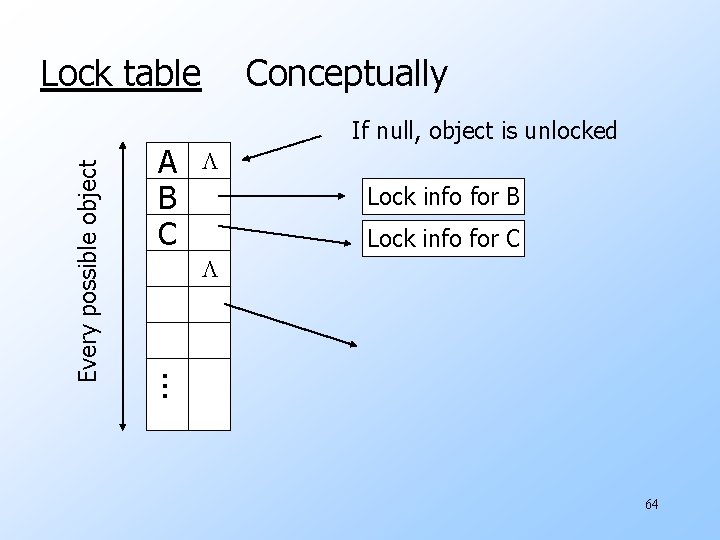

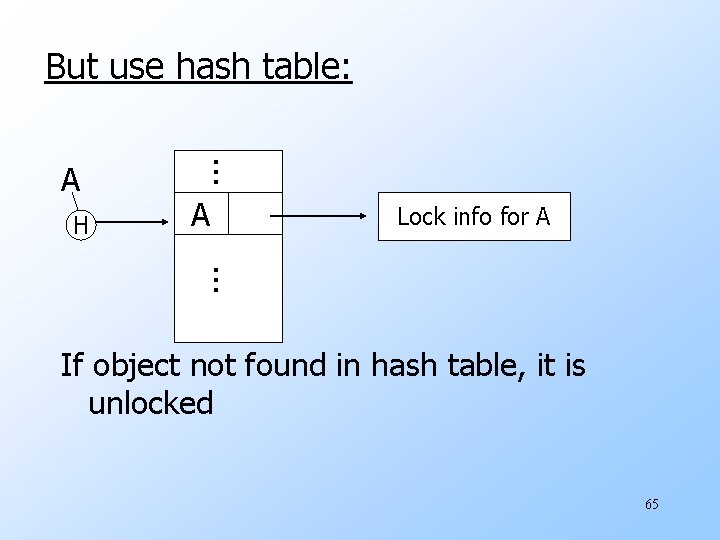

A B C Conceptually If null, object is unlocked Lock info for B Lock info for C . . . Every possible object Lock table 64

But use hash table: H . . . A A Lock info for A . . . If object not found in hash table, it is unlocked 65

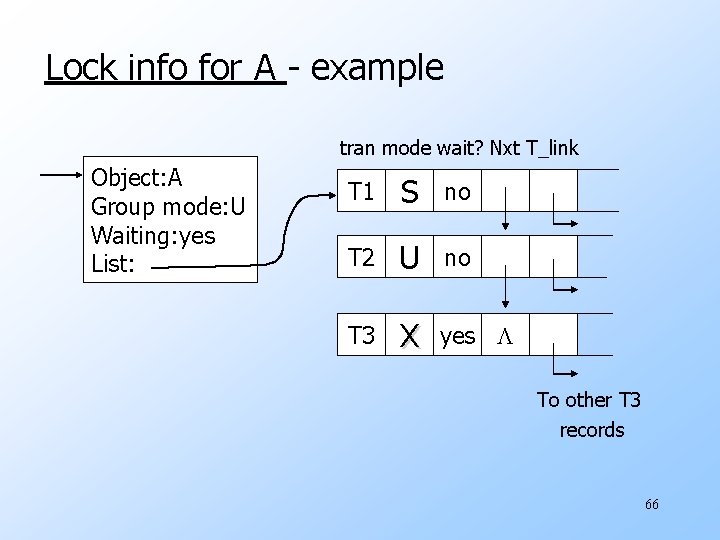

Lock info for A - example tran mode wait? Nxt T_link Object: A Group mode: U Waiting: yes List: T 1 S no T 2 U no T 3 X yes To other T 3 records 66

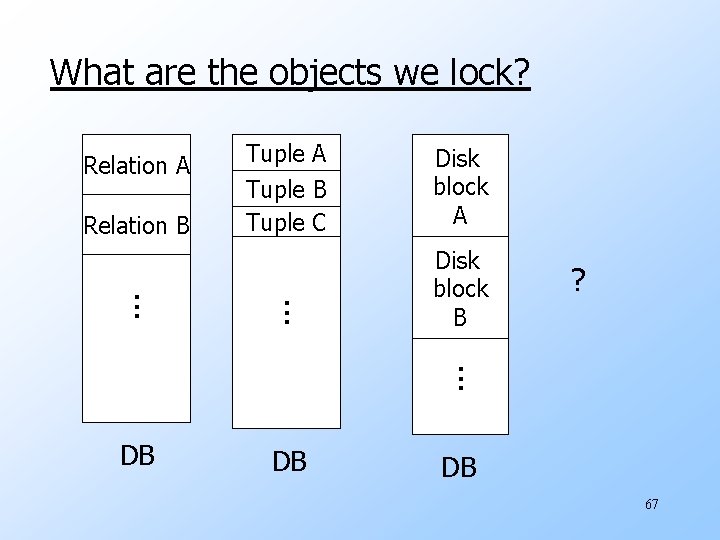

What are the objects we lock? Relation A Relation B Tuple A Tuple B Tuple C Disk block A . . . Disk block B ? . . . DB DB DB 67

u. Locking works in any case, but should we choose small or large objects? u. If we lock large objects (e. g. , Relations) w Need few locks w Low concurrency u. If we lock small objects (e. g. , tuples, fields) w Need more locks w More concurrency 68

We can have it both ways!! Called multi-granularity locking. 69

Optimistic Concurrency Control u. Locking is pessimistic -- assumes something bad will try to happen and prevents it u. Instead assume conflicts won't occur in the common case, then check at the end of a transaction w timestamping w validation 70

Timestamping u. Assign a "timestamp" to each transaction u. Keep track of the timestamp of the last transaction to read and write each DB element u. Compare these values to check for serializability u. Abort transaction if there is a violation 71

Validation Transactions have 3 phases: (1) Read w all DB values read w writes to temporary storage w no locking (2) Validate w check if schedule so far is serializable (3) Write w if validate ok, write to DB 72

Comparison u. Space usage of optimistic CC is about the same as locking: roughly proportional to number of DB elements accessed u. Optimistic CC is useful when w conflicts are rare w system resources are plentiful w there are real-time constraints 73

- Slides: 73