Concurrency Control Concurrency Control Techniques Protocols that guarantee

- Slides: 75

Concurrency Control

Concurrency Control Techniques • Protocols that guarantee serializability 1. Locking 2. Timestamps 3. Multiversion 4. Optimistic - validation or certification

Locking

Serlializable? • R 1(X) R 4(X) R 2(Y) W 4(X) R 2(X) W 2(Y) C 1 C 4 C 2 • R 1(Y) R 2(X) W 2(Y) C 2 R 1(X) W 1(X) C 1

Locking • Locking - main technique to control concurrent execution • execution based on concept of locking data items • locks granted to a specific transaction for a particular data item • a lock forces mutual exclusion on data items • lock manager subsystem to keep track of and control access to locks

Binary locks • binary lock - 2 states or values – locked, unlocked • distinct lock for each data item • Suppose: – transaction T must issue a lock request before R, W – issue unlock after R, W – Too restrictive, what if want transactions to read at same time?

Multiple-mode lock • multiple-mode lock - 3 types, indivisible – Read lock - share lock – Write lock - exclusive lock – Unlock - unlock a lock needs 3 fields: <data, lock(R, W), # of reads>

Locking Rules for multiple-mode (theoretical) Rules: 1. T must issue request for R or W lock before any R(X) 2. T must issue request for W lock before any W(X) 3. T must issue Unlock(X) after R or W completed OR once commit assume all remaining locks unlocked 4. If T issues request for W lock(X) and holds R lock on X, must upgrade R lock(X) to W lock(X) 5. If issue R lock(X) and hold W lock on X, must downgrade W lock(X) to R lock(X) 6. T will not issue Unlock(X) unless hold R lock(X) or W lock(X)

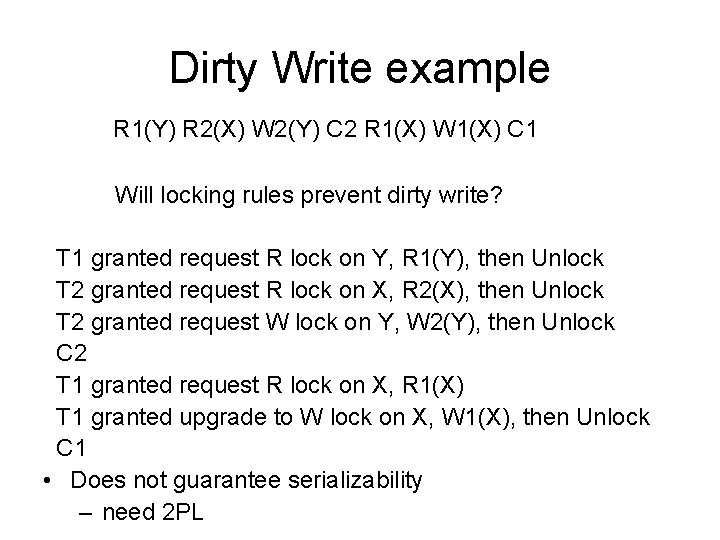

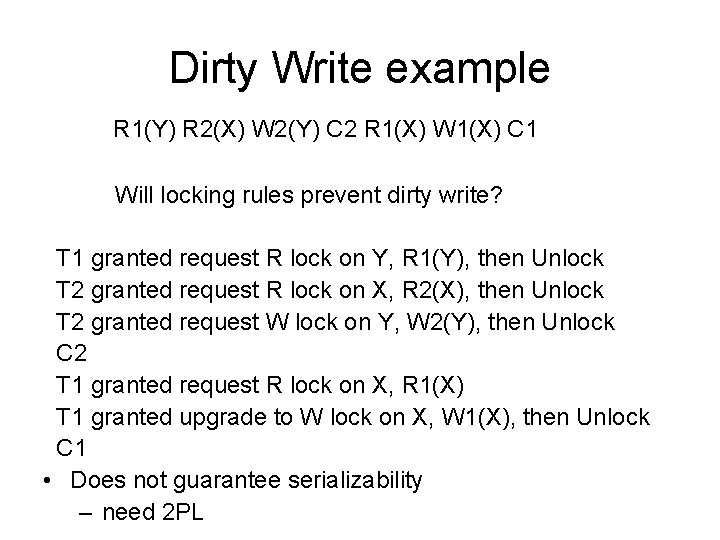

Dirty Write example R 1(Y) R 2(X) W 2(Y) C 2 R 1(X) W 1(X) C 1 Will locking rules prevent dirty write? T 1 granted request R lock on Y, R 1(Y), then Unlock T 2 granted request R lock on X, R 2(X), then Unlock T 2 granted request W lock on Y, W 2(Y), then Unlock C 2 T 1 granted request R lock on X, R 1(X) T 1 granted upgrade to W lock on X, W 1(X), then Unlock C 1 • Does not guarantee serializability – need 2 PL

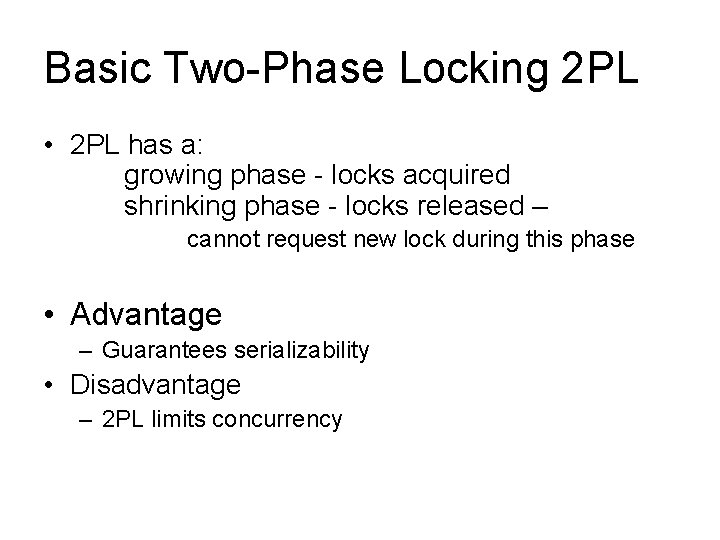

Basic Two-Phase Locking 2 PL • 2 PL has a: growing phase - locks acquired shrinking phase - locks released – cannot request new lock during this phase • Advantage – Guarantees serializability • Disadvantage – 2 PL limits concurrency

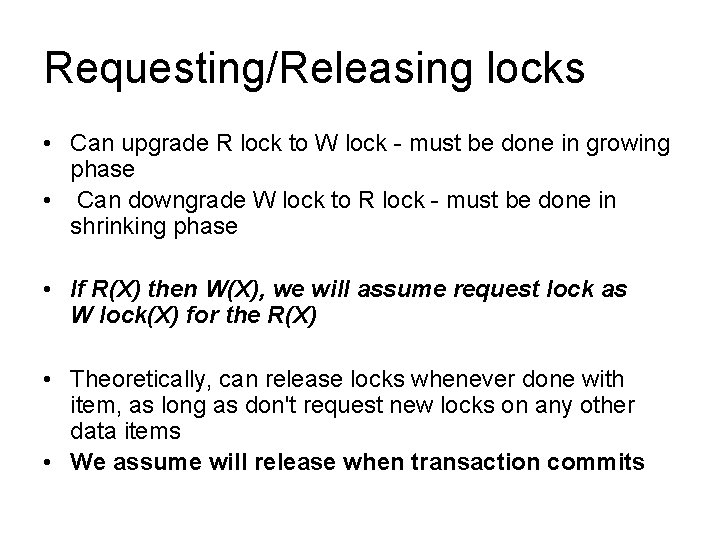

Requesting/Releasing locks • Can upgrade R lock to W lock - must be done in growing phase • Can downgrade W lock to R lock - must be done in shrinking phase • If R(X) then W(X), we will assume request lock as W lock(X) for the R(X) • Theoretically, can release locks whenever done with item, as long as don't request new locks on any other data items • We assume will release when transaction commits

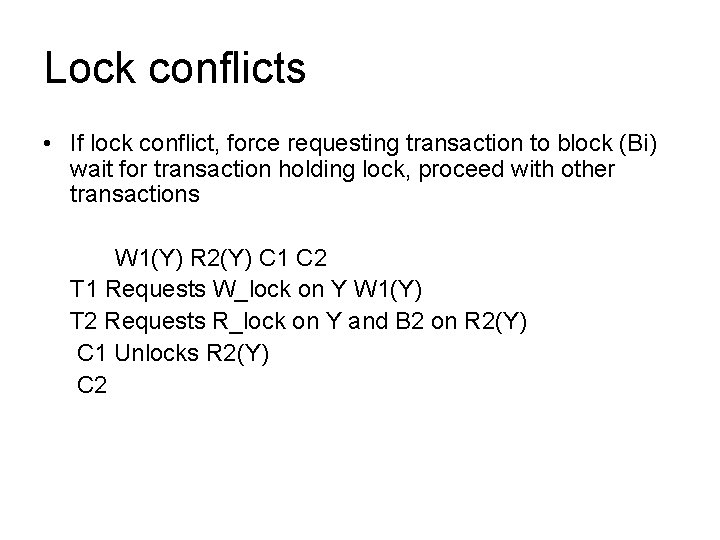

Lock conflicts • If lock conflict, force requesting transaction to block (Bi) wait for transaction holding lock, proceed with other transactions W 1(Y) R 2(Y) C 1 C 2 T 1 Requests W_lock on Y W 1(Y) T 2 Requests R_lock on Y and B 2 on R 2(Y) C 1 Unlocks R 2(Y) C 2

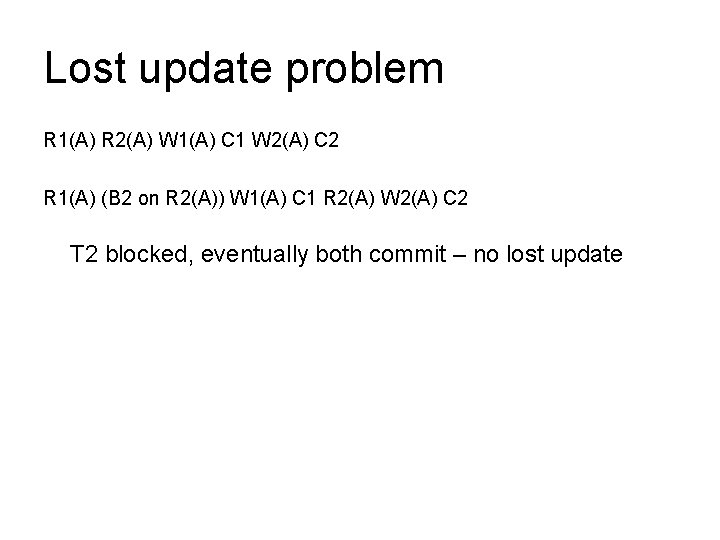

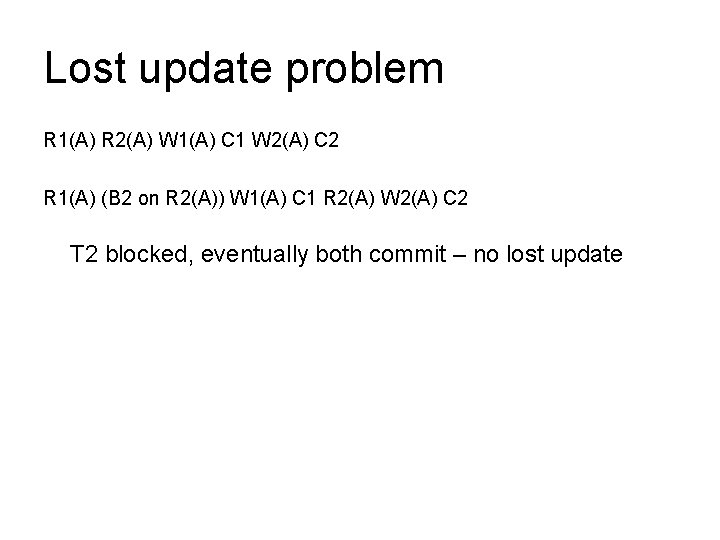

Lost update problem R 1(A) R 2(A) W 1(A) C 1 W 2(A) C 2 R 1(A) (B 2 on R 2(A)) W 1(A) C 1 R 2(A) W 2(A) C 2 T 2 blocked, eventually both commit – no lost update

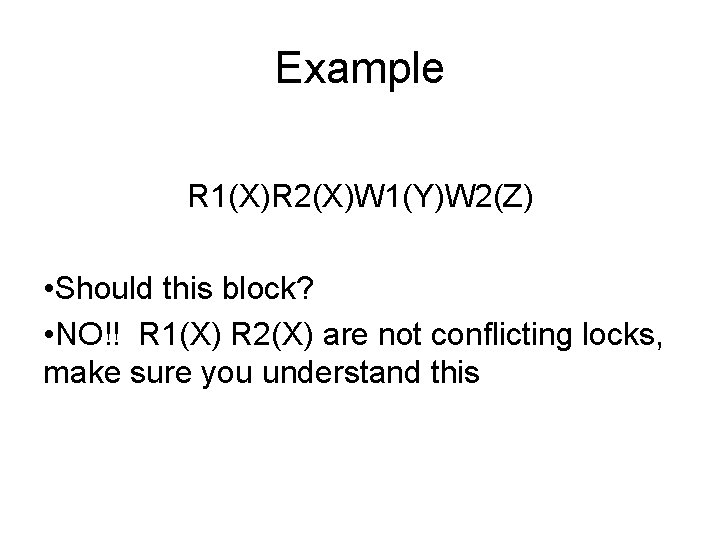

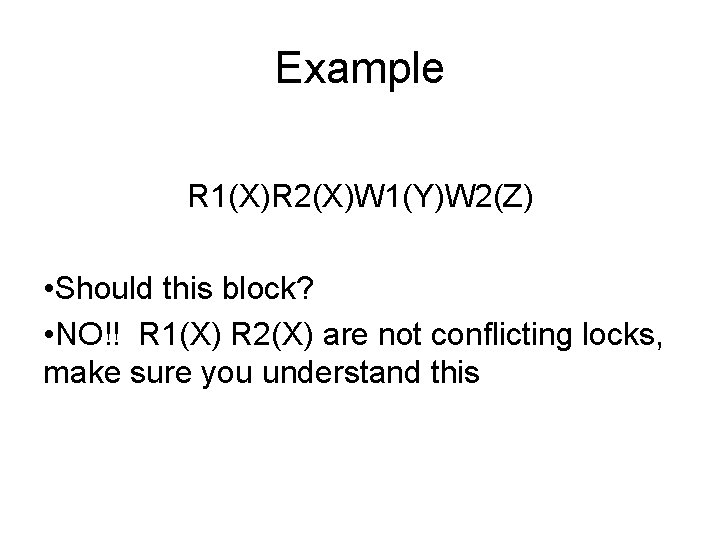

Example R 1(X)R 2(X)W 1(Y)W 2(Z) • Should this block? • NO!! R 1(X) R 2(X) are not conflicting locks, make sure you understand this

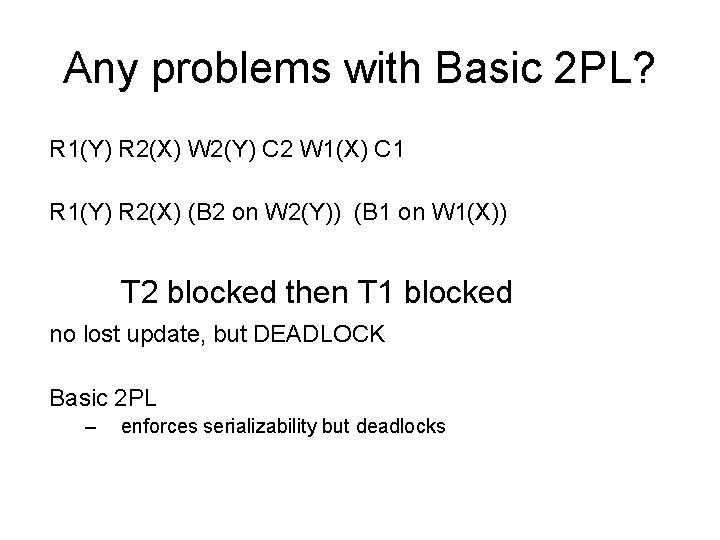

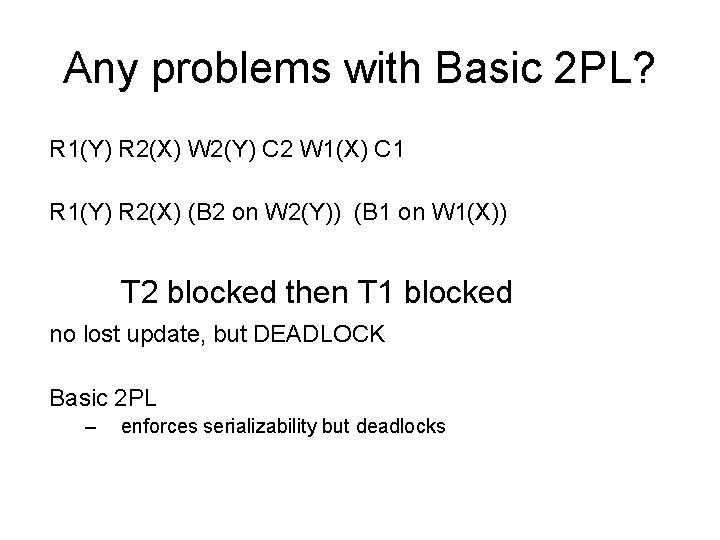

Any problems with Basic 2 PL? R 1(Y) R 2(X) W 2(Y) C 2 W 1(X) C 1 R 1(Y) R 2(X) (B 2 on W 2(Y)) (B 1 on W 1(X)) T 2 blocked then T 1 blocked no lost update, but DEADLOCK Basic 2 PL – enforces serializability but deadlocks

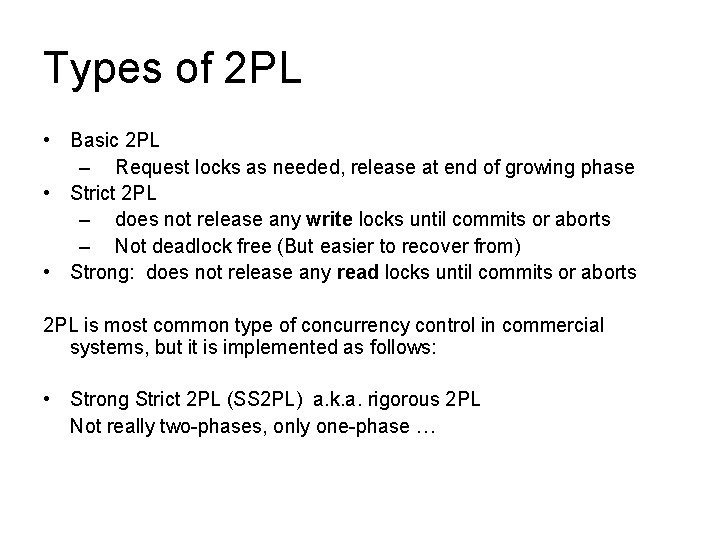

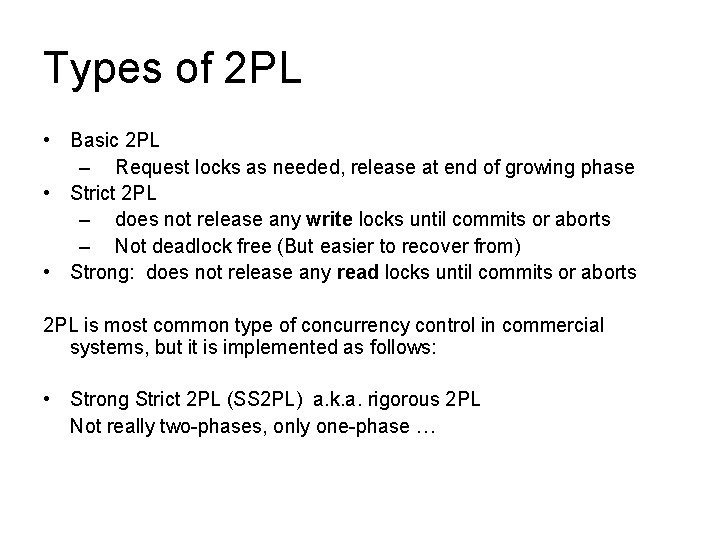

Types of 2 PL • Basic 2 PL – Request locks as needed, release at end of growing phase • Strict 2 PL – does not release any write locks until commits or aborts – Not deadlock free (But easier to recover from) • Strong: does not release any read locks until commits or aborts 2 PL is most common type of concurrency control in commercial systems, but it is implemented as follows: • Strong Strict 2 PL (SS 2 PL) a. k. a. rigorous 2 PL Not really two-phases, only one-phase …

Strategies for deadlock in 2 PL 1. Conservative 2 PL – not popular – requires transactions to lock all data items before begin executing • prevents deadlock • Declare readset, writeset • or request data items in order

Strategies for deadlock in 2 PL 2. No waiting - if Ti unable to obtain a lock, abort/restart after a time delay. T's can abort and restart needlessly. 3. Cautious waiting - if Ti tried to lock X and X is already locked by Tj and if Tj is not blocked: Ti waits else Tj aborts Deadlock free - total ordering of blocking times 4. Timeouts - if Ti waits > threshold, Ti is aborted

Strategies cont’d 5. Deadlock detection - useful if T's rarely access the same items and each T only locks a few items – – – construct a waits for graph (maintained by lock scheduler) deadlock when cycle in graph Problems: • victim selection - which to abort • Livelock - if repeatedly choose same victim to abort/restart • if wait indefinite period of time, need a fair waiting scheme – FCFS

Strategies cont’d 6. Timestamps to prevent deadlocks – – – Transactions can be assigned timestamps, TS(Ti) if T 1 starts before T 2, TS(T 1) < TS(T 2) if T 1 starts after T 2, TS(T 1) > TS(T 2) older Ti has a smaller TS Timestamp can be: a counter, or the current value of the system clock wait-die or wound-wait strategies use TSs Can you think of a strategy using TSs?

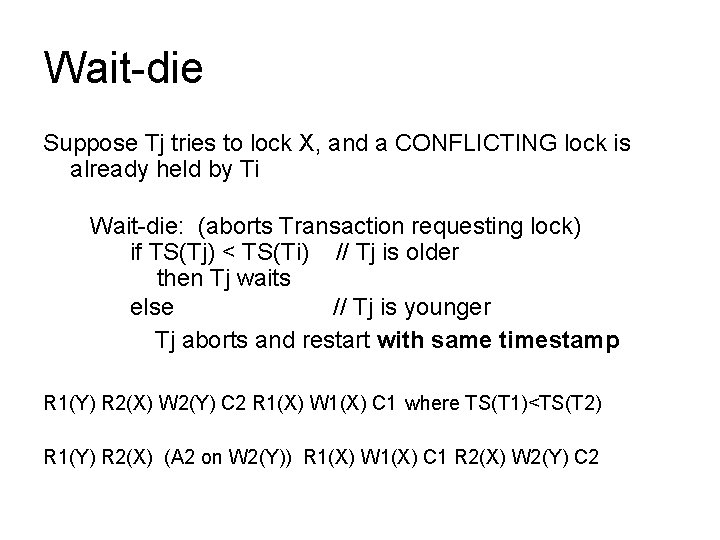

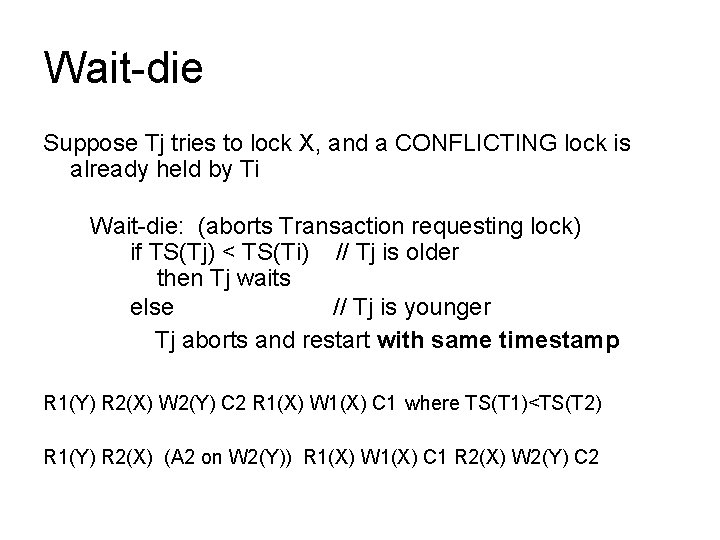

Wait-die Suppose Tj tries to lock X, and a CONFLICTING lock is already held by Ti Wait-die: (aborts Transaction requesting lock) if TS(Tj) < TS(Ti) // Tj is older then Tj waits else // Tj is younger Tj aborts and restart with same timestamp R 1(Y) R 2(X) W 2(Y) C 2 R 1(X) W 1(X) C 1 where TS(T 1)<TS(T 2) R 1(Y) R 2(X) (A 2 on W 2(Y)) R 1(X) W 1(X) C 1 R 2(X) W 2(Y) C 2

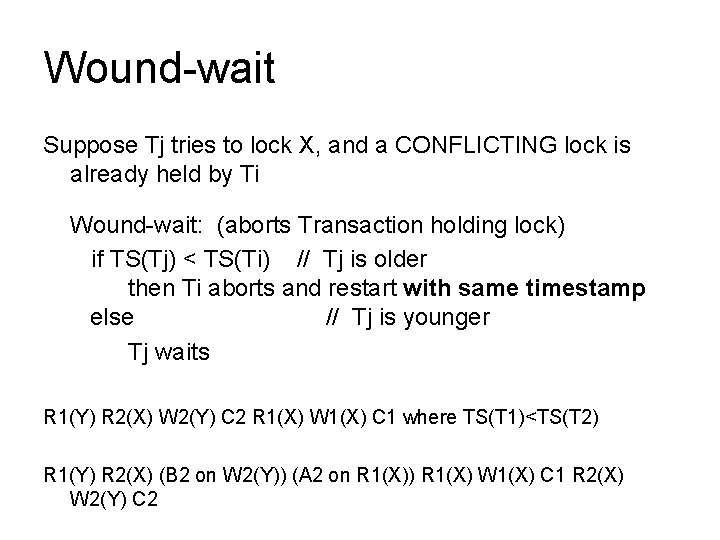

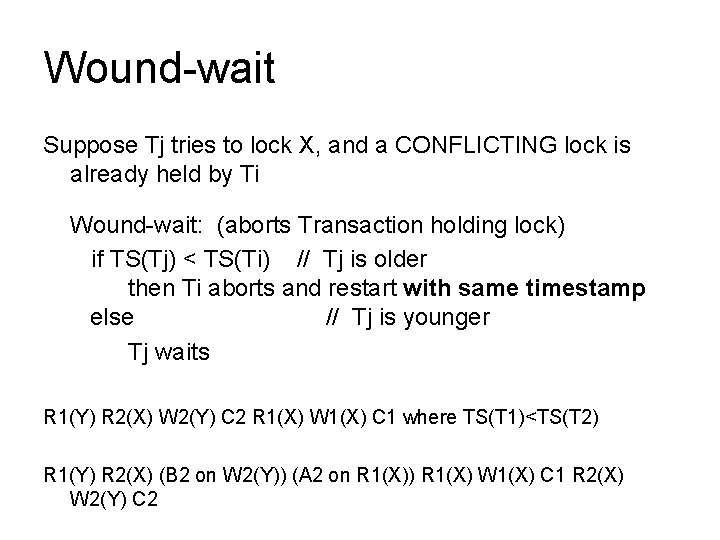

Wound-wait Suppose Tj tries to lock X, and a CONFLICTING lock is already held by Ti Wound-wait: (aborts Transaction holding lock) if TS(Tj) < TS(Ti) // Tj is older then Ti aborts and restart with same timestamp else // Tj is younger Tj waits R 1(Y) R 2(X) W 2(Y) C 2 R 1(X) W 1(X) C 1 where TS(T 1)<TS(T 2) R 1(Y) R 2(X) (B 2 on W 2(Y)) (A 2 on R 1(X)) R 1(X) W 1(X) C 1 R 2(X) W 2(Y) C 2

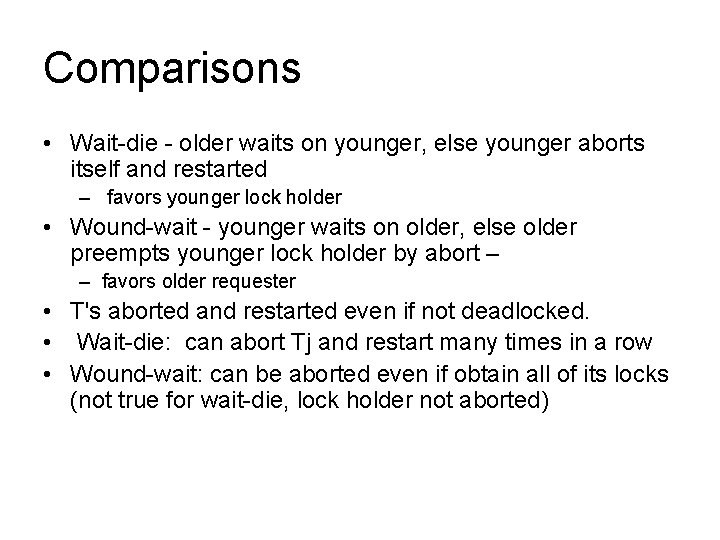

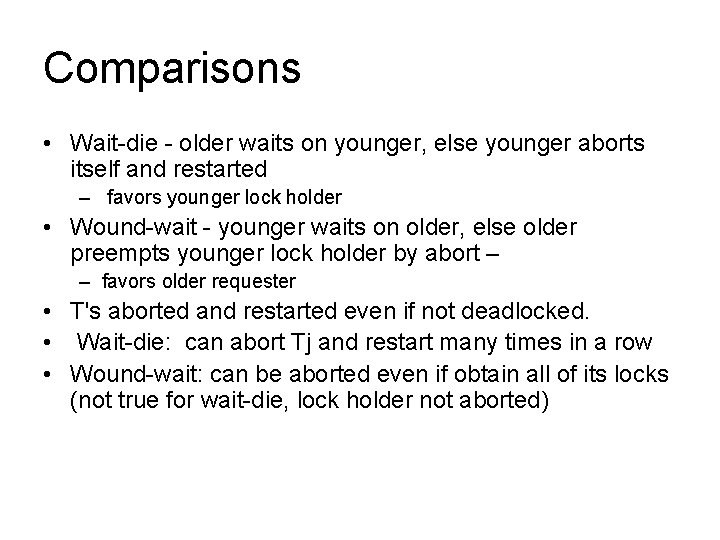

Comparisons • Wait-die - older waits on younger, else younger aborts itself and restarted – favors younger lock holder • Wound-wait - younger waits on older, else older preempts younger lock holder by abort – – favors older requester • T's aborted and restarted even if not deadlocked. • Wait-die: can abort Tj and restart many times in a row • Wound-wait: can be aborted even if obtain all of its locks (not true for wait-die, lock holder not aborted)

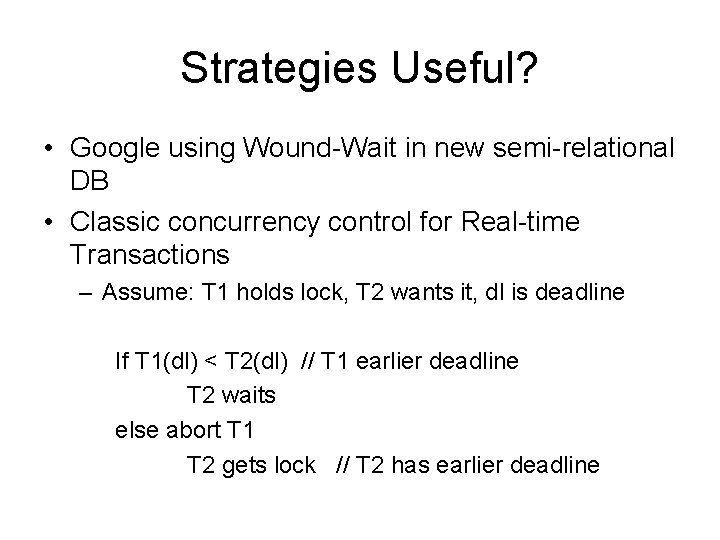

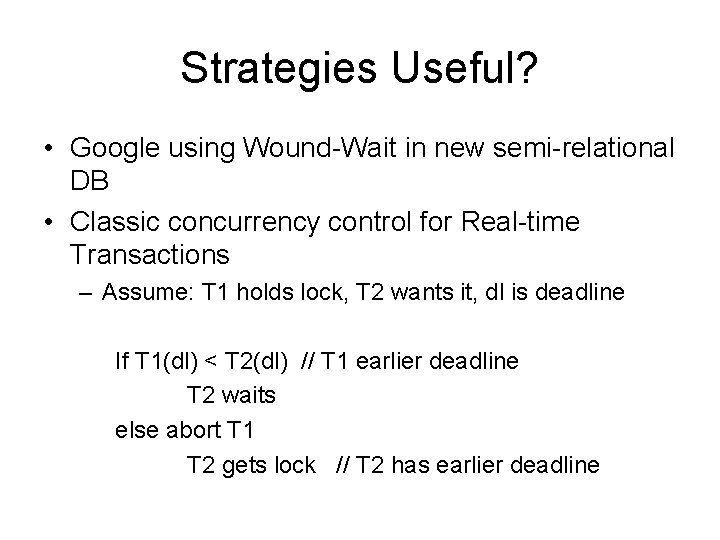

Strategies Useful? • Google using Wound-Wait in new semi-relational DB • Classic concurrency control for Real-time Transactions – Assume: T 1 holds lock, T 2 wants it, dl is deadline If T 1(dl) < T 2(dl) // T 1 earlier deadline T 2 waits else abort T 1 T 2 gets lock // T 2 has earlier deadline

Problems with serializability • Scheduling that guarantees perfect serializability can be intrusive on performance • Too many transaction in wait state • If increase number of threads, can reduce the number of transactions active • CPU never fully utilized

Alternatives to serializability • Weakened forms of 2 PL locking in SQL levels of isolation • Used instead of degrees of isolation • Can set the isolation level with set transaction statement (can specify R only, W only) 1) read uncommitted 2) read committed – Default Oracle 3) repeatable read 4) serializable

Isolation levels • Lock types used to implement – Short-term lock • guarantees R, W, is atomic – long-term lock • held until Transaction commits or aborts

Read uncommitted • Read uncommitted (for read only Ts) – – no long-term locks used – allow for Read only operations • no dirty writes (since only read) • but dirty reads can occur

Read committed • Read committed – (no dirty reads) – W lock long term, R lock short term – Can only read data that has been written by committed transactions – Unrepeatable reads can occur – Lost update can still occur R 1(A) R 2(A) W 1(A) C 2 C 1 // will not allow R 1(A) R 2(A) W 2(A) C 2 W 1(A) C 1 // may allow

Repeatable read • Repeatable read – – W lock, R lock long term – Repeatable reads, no lost update – But, predicate locking is not guaranteed • Predicate locking – lock only rows that satisfy specified condition (e. g. major =‘CS’) • therefore can have phantom updates due to inserting new rows – e. g. if branch totals in branch table, and insert while computing total

Serializability • Serializable requires R, W lock long term on all data satisfying predicate • How? – lock entire table

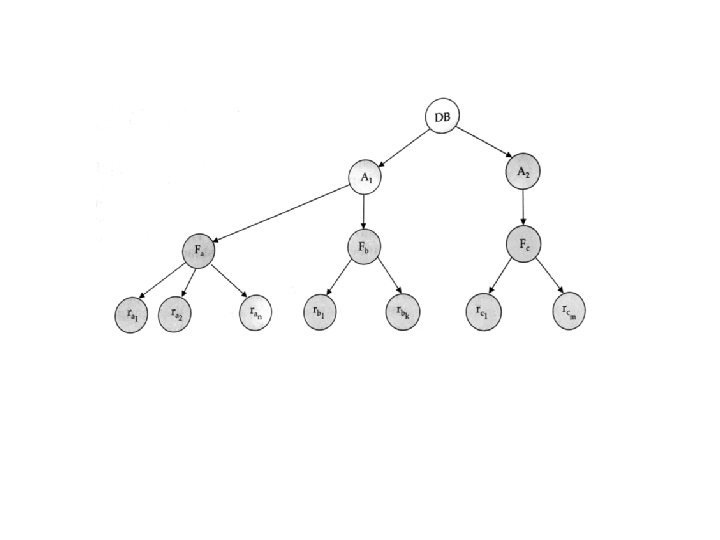

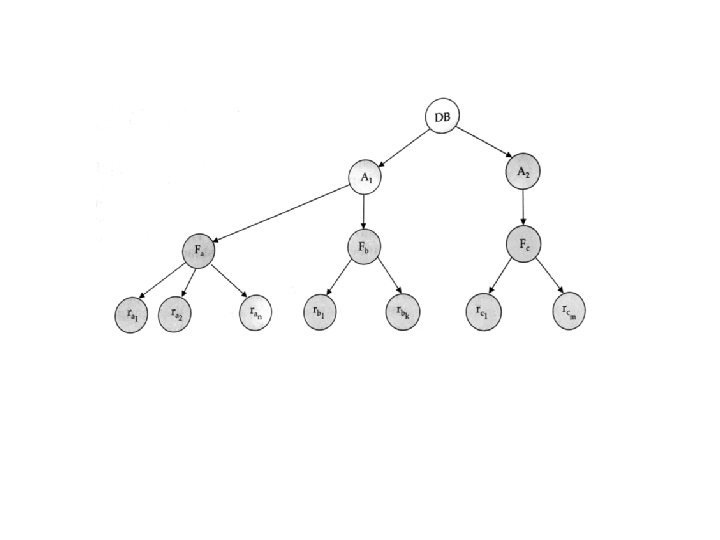

Granularity Hierarchy • How to accommodate different granularities of locks by the lock manager • If only a few data items from a table are needed, how to indicate they are locked • Use a tree – Allow data items to be of various sizes • Used with 2 PL to guarantee serializability

Tree • Multiple levels of nodes – Highest node is entire DB – Non-leaf node as data associated with descendants – Each node can be locked individually – If lock a node, all ancestors are also locked in appropriate mode – Locks are: • Shared or exclusive • Intention or explicit mode

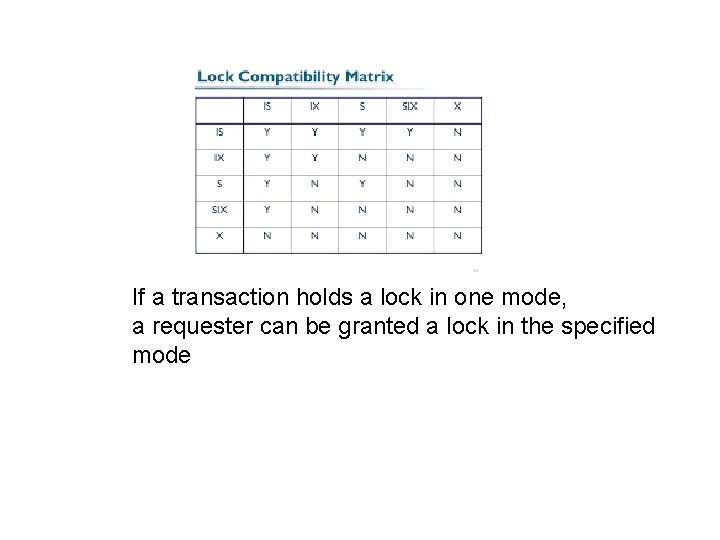

• How to determine if a node at a lower level is locked without searching entire tree? • If a node at a lower level must be explicitly locked, then all ancestor nodes are intention locked as traverse tree • S shared, IS intention-shared • X exclusive, IX intention exclusive • SIX shared with intention exclusive • Strategy most useful for short transactions with few data items and long transactions produce reports form file

SIX • What is SIX? – Subtree rooted in that node is S and then X at lower level – The lock owner can read and change data in the table, partition, or table space. Concurrent processes can read data in the table, partition, or table space, but not change it. Only when the lock owner changes data does it acquire page or row locks. – Does this mean I can share everything except what I want to write to?

Locking protocol • Top down lock: – Use compatibility matrix on next page – T must lock root first (in any mode) – T can lock Q in S or IS only if T has parent of Q in IX or IS mode – T can lock Q in X, SIX, or IX only if T has parent of Q locked in IX or SIX mode • Bottom up unlock: – T can lock node only if not previously unlocked any node – T can unlock Q only if T has no children of Q locked

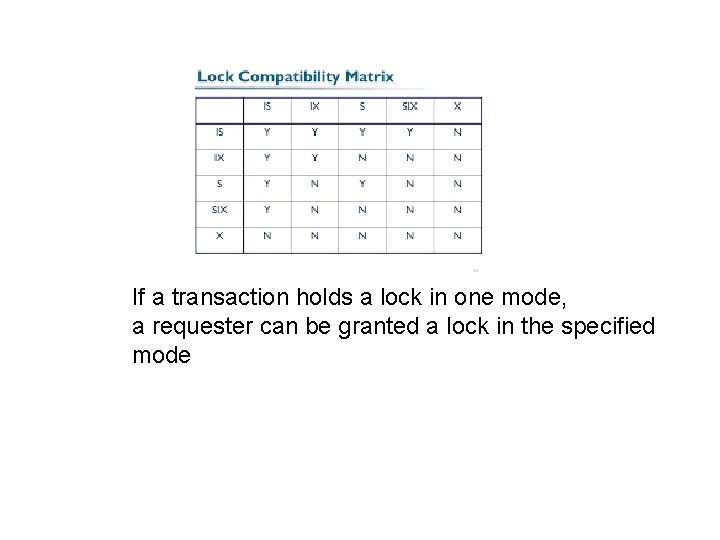

If a transaction holds a lock in one mode, a requester can be granted a lock in the specified mode

Serializability • Do we always have to use locking to ensure serializability?

Timestamp Ordering • No - Timestamp Ordering – concurrency control techniques based on timestampe (TS) - do not use locks – Can deadlock occur?

Timestamp Ordering

Timestamps • Use timestamp ordering (TO) • in 2 PL schedule, serializable by being equivalent to some serial schedule allowed by locking protocols • In TO schedule, serializable by being equivalent to particular order that corresponds to order of transaction TS's – This means conflicting operations must execute in order of their timestamps, e. g. R/Ws to same data item must occur in the same order as their TS

Timestamps (TO) • Basic TO algorithm: – – associated with each X, 2 TS values R_TS(X) - largest TS that has successfully read X W_TS(X) - largest TS that has successfully written X If T is aborted, it is restarted with LATER timestamp

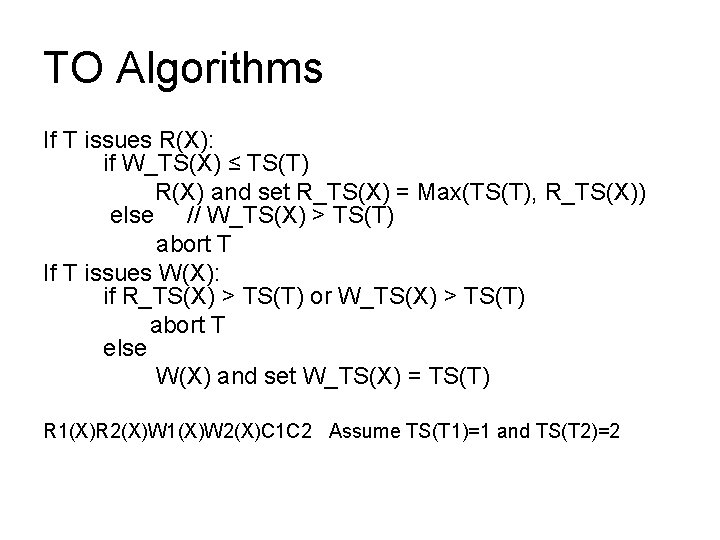

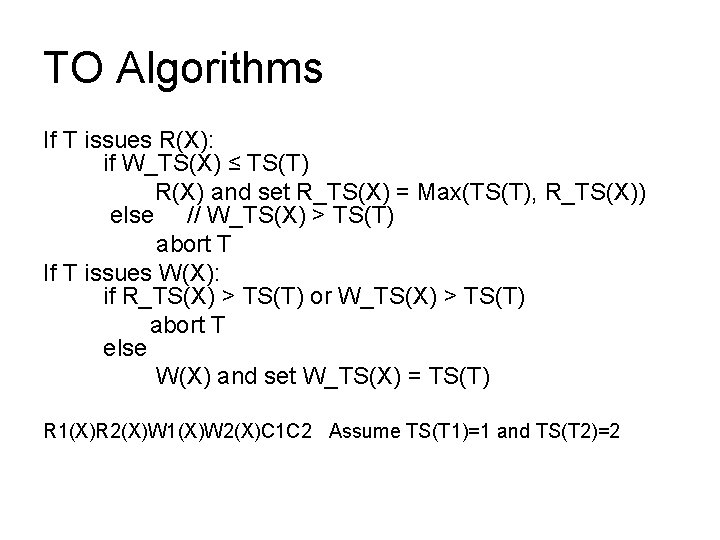

TO Algorithms If T issues R(X): if W_TS(X) ≤ TS(T) R(X) and set R_TS(X) = Max(TS(T), R_TS(X)) else // W_TS(X) > TS(T) abort T If T issues W(X): if R_TS(X) > TS(T) or W_TS(X) > TS(T) abort T else W(X) and set W_TS(X) = TS(T) R 1(X)R 2(X)W 1(X)W 2(X)C 1 C 2 Assume TS(T 1)=1 and TS(T 2)=2

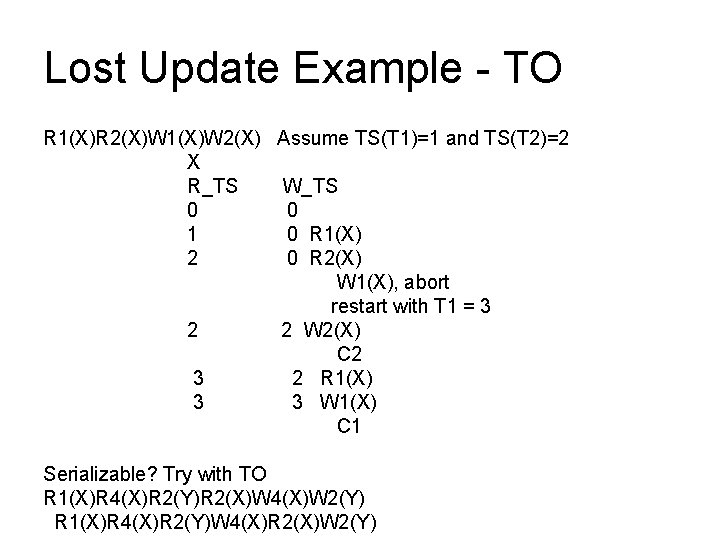

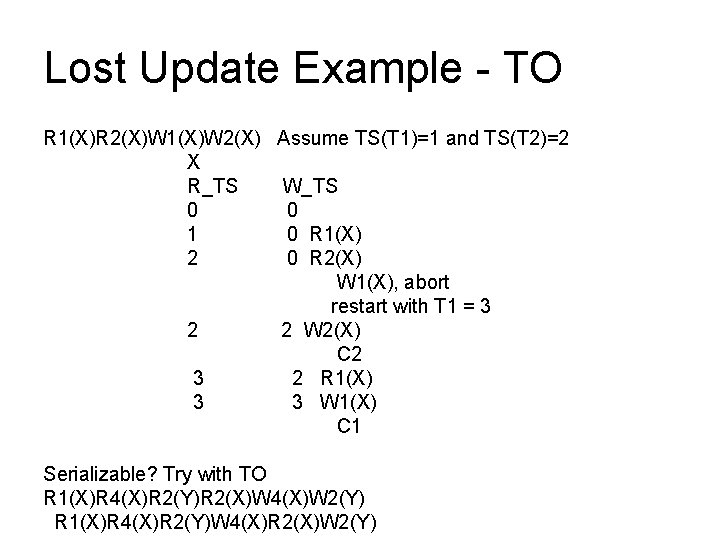

Lost Update Example - TO R 1(X)R 2(X)W 1(X)W 2(X) Assume TS(T 1)=1 and TS(T 2)=2 X R_TS W_TS 0 0 1 0 R 1(X) 2 0 R 2(X) W 1(X), abort restart with T 1 = 3 2 2 W 2(X) C 2 3 2 R 1(X) 3 3 W 1(X) C 1 Serializable? Try with TO R 1(X)R 4(X)R 2(Y)R 2(X)W 4(X)W 2(Y) R 1(X)R 4(X)R 2(Y)W 4(X)R 2(X)W 2(Y)

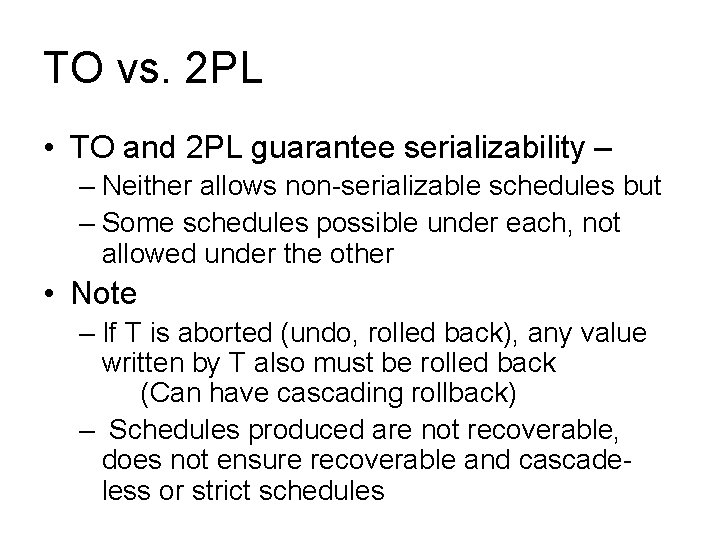

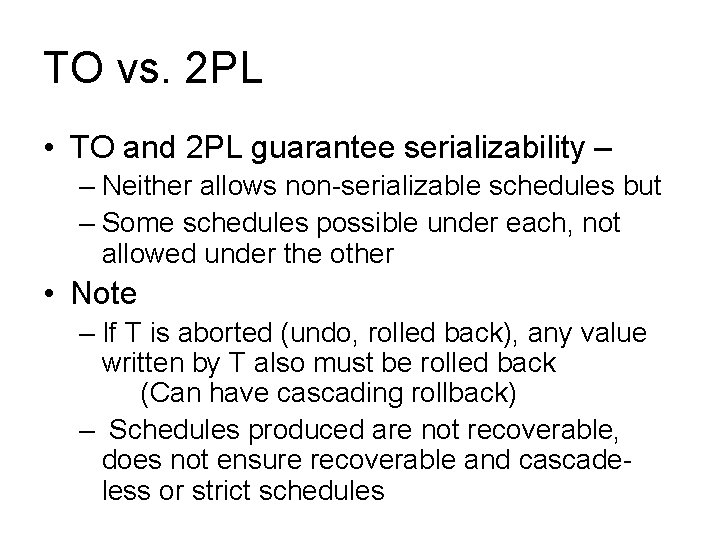

TO vs. 2 PL • TO and 2 PL guarantee serializability – – Neither allows non-serializable schedules but – Some schedules possible under each, not allowed under the other • Note – If T is aborted (undo, rolled back), any value written by T also must be rolled back (Can have cascading rollback) – Schedules produced are not recoverable, does not ensure recoverable and cascadeless or strict schedules

Multiversion Concurrency Control a. k. a Multiversion Timestamp Ordering

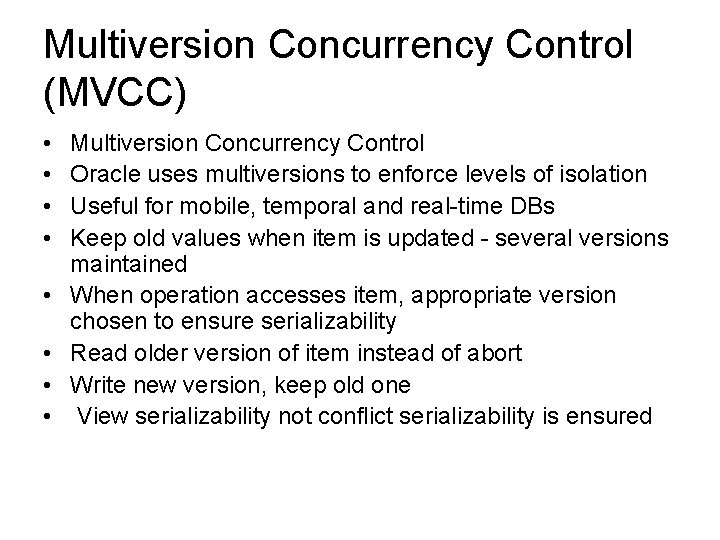

Multiversion Concurrency Control (MVCC) • • Multiversion Concurrency Control Oracle uses multiversions to enforce levels of isolation Useful for mobile, temporal and real-time DBs Keep old values when item is updated - several versions maintained When operation accesses item, appropriate version chosen to ensure serializability Read older version of item instead of abort Write new version, keep old one View serializability not conflict serializability is ensured

Multiversion • Disadvantage - more storage • however, may keep older versions for recovery anyway • Google keeps multiple versions for semirelational DB

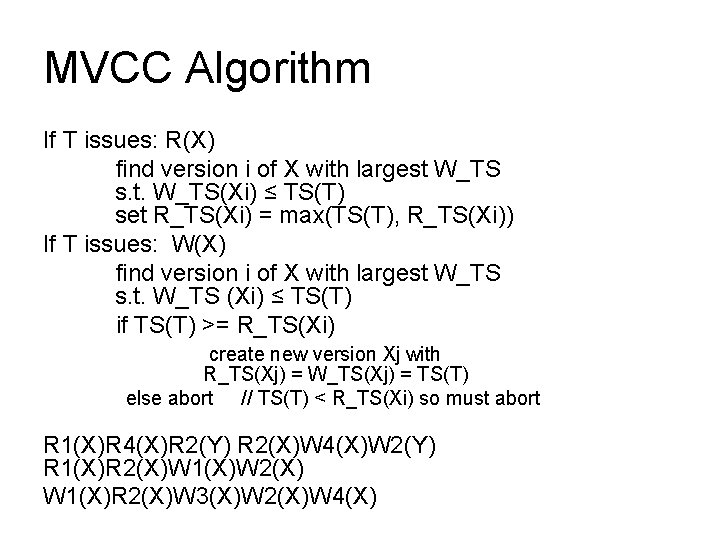

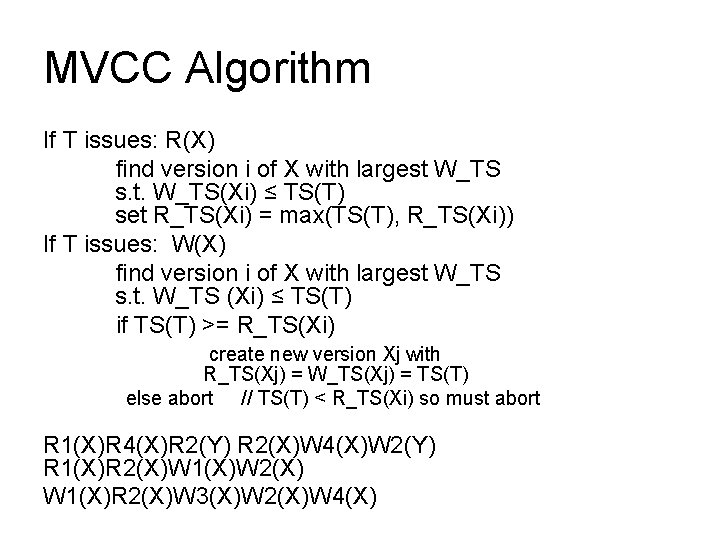

MVCC Algorithm If T issues: R(X) find version i of X with largest W_TS s. t. W_TS(Xi) ≤ TS(T) set R_TS(Xi) = max(TS(T), R_TS(Xi)) If T issues: W(X) find version i of X with largest W_TS s. t. W_TS (Xi) ≤ TS(T) if TS(T) >= R_TS(Xi) create new version Xj with R_TS(Xj) = W_TS(Xj) = TS(T) else abort // TS(T) < R_TS(Xi) so must abort R 1(X)R 4(X)R 2(Y) R 2(X)W 4(X)W 2(Y) R 1(X)R 2(X)W 1(X)W 2(X) W 1(X)R 2(X)W 3(X)W 2(X)W 4(X)

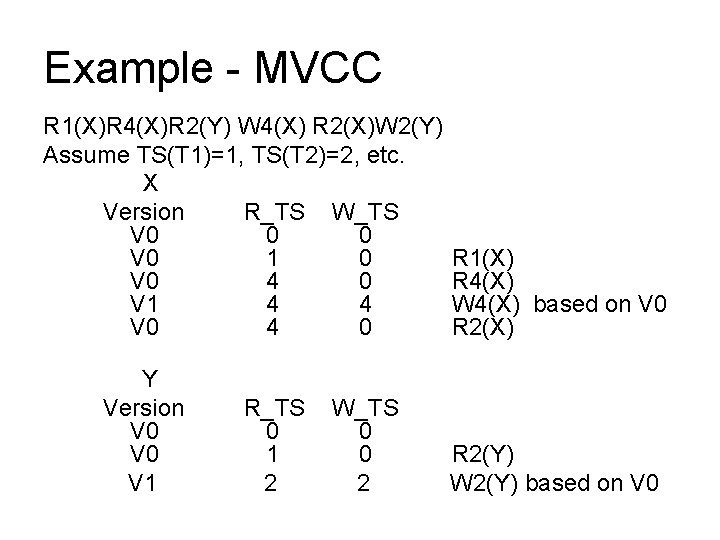

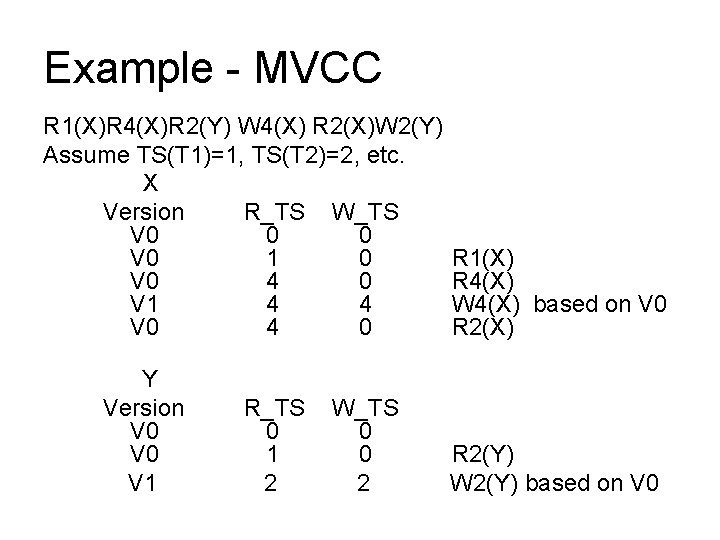

Example - MVCC R 1(X)R 4(X)R 2(Y) W 4(X) R 2(X)W 2(Y) Assume TS(T 1)=1, TS(T 2)=2, etc. X Version R_TS W_TS V 0 0 0 V 0 1 0 V 0 4 0 V 1 4 4 V 0 4 0 Y Version V 0 V 1 R_TS 0 1 2 W_TS 0 0 2 R 1(X) R 4(X) W 4(X) based on V 0 R 2(X) R 2(Y) W 2(Y) based on V 0

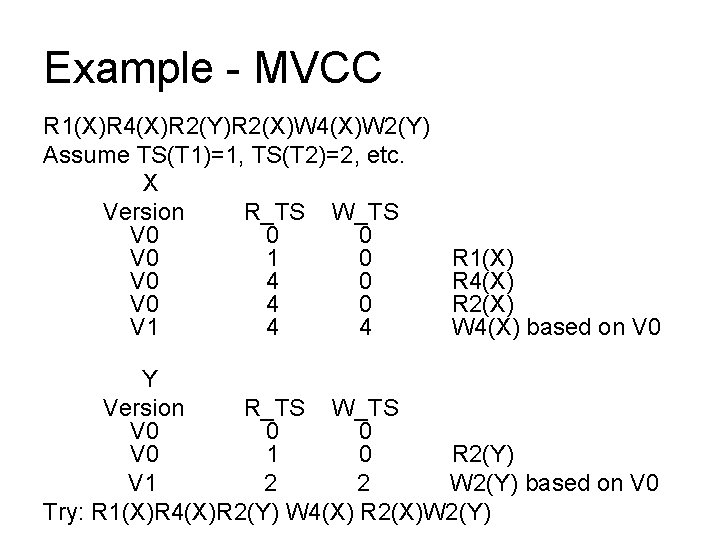

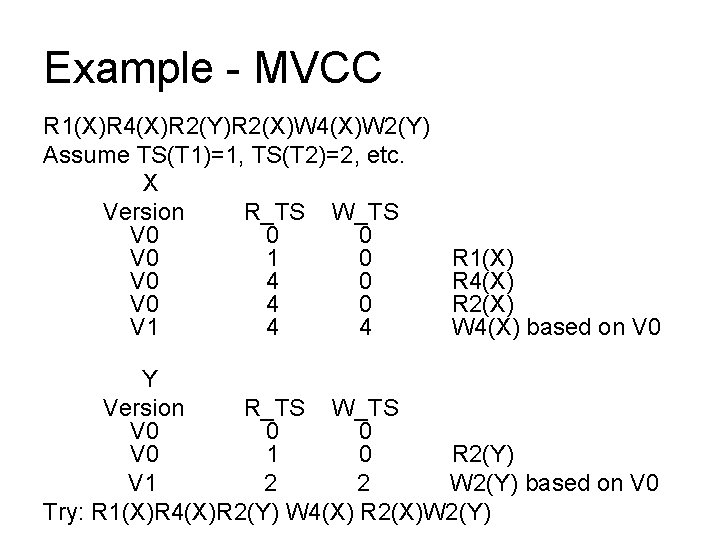

Example - MVCC R 1(X)R 4(X)R 2(Y)R 2(X)W 4(X)W 2(Y) Assume TS(T 1)=1, TS(T 2)=2, etc. X Version R_TS W_TS V 0 0 0 V 0 1 0 V 0 4 0 V 1 4 4 R 1(X) R 4(X) R 2(X) W 4(X) based on V 0 Y Version R_TS W_TS V 0 0 0 V 0 1 0 R 2(Y) V 1 2 2 W 2(Y) based on V 0 Try: R 1(X)R 4(X)R 2(Y) W 4(X) R 2(X)W 2(Y)

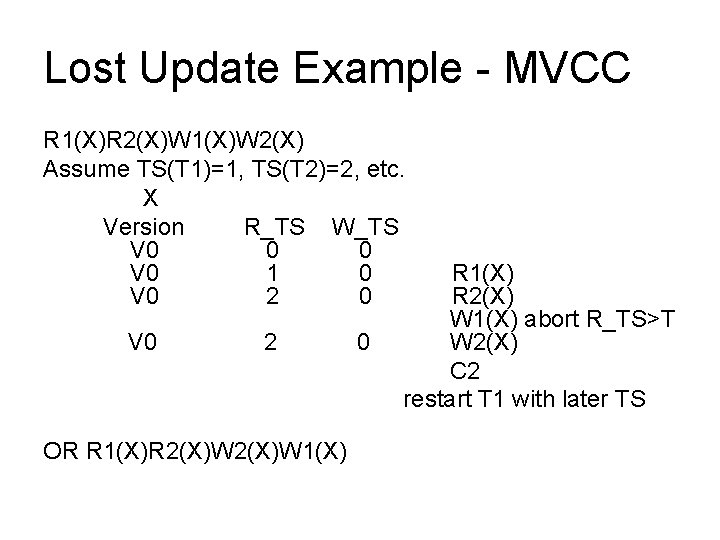

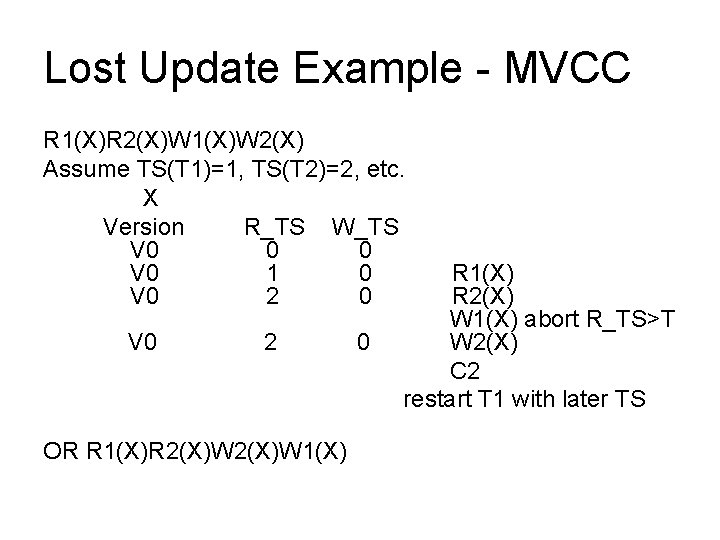

Lost Update Example - MVCC R 1(X)R 2(X)W 1(X)W 2(X) Assume TS(T 1)=1, TS(T 2)=2, etc. X Version R_TS W_TS V 0 0 0 V 0 1 0 V 0 2 OR R 1(X)R 2(X)W 1(X) 0 R 1(X) R 2(X) W 1(X) abort R_TS>T W 2(X) C 2 restart T 1 with later TS

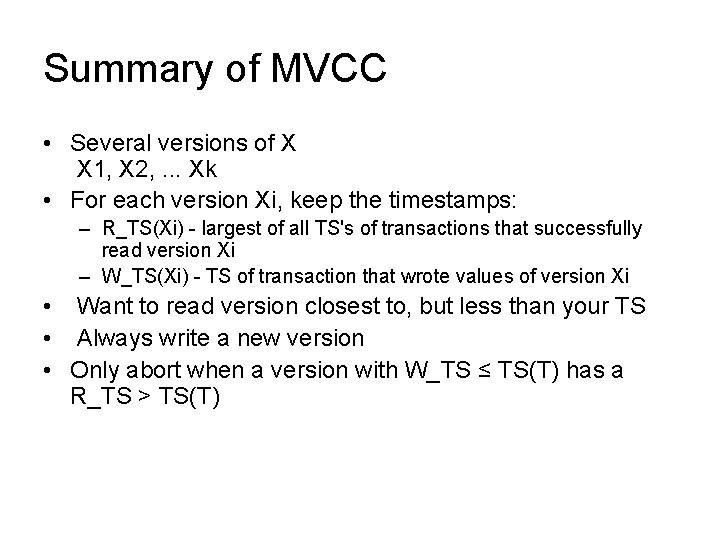

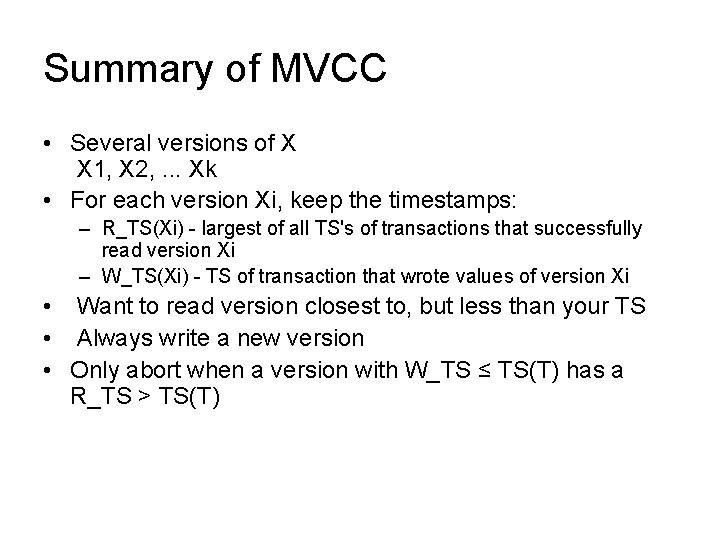

Summary of MVCC • Several versions of X X 1, X 2, . . . Xk • For each version Xi, keep the timestamps: – R_TS(Xi) - largest of all TS's of transactions that successfully read version Xi – W_TS(Xi) - TS of transaction that wrote values of version Xi • Want to read version closest to, but less than your TS • Always write a new version • Only abort when a version with W_TS ≤ TS(T) has a R_TS > TS(T)

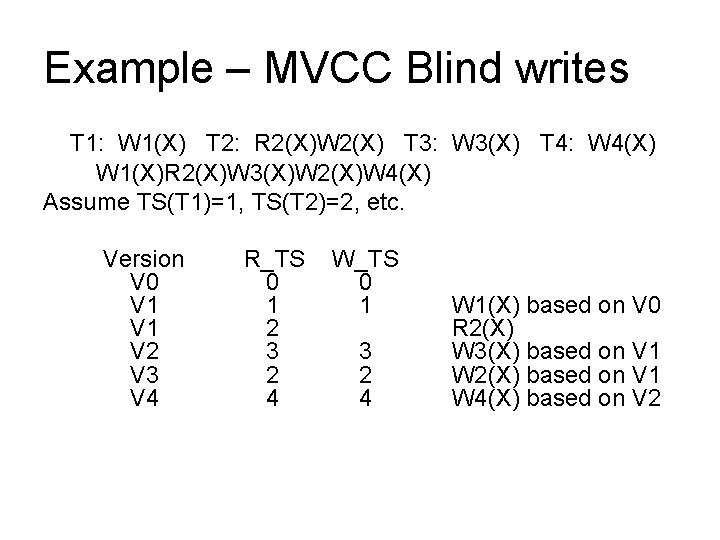

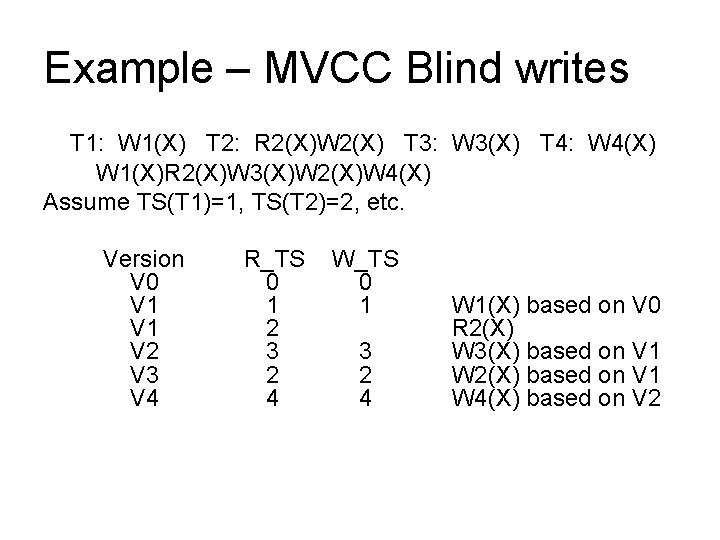

Example – MVCC Blind writes T 1: W 1(X) T 2: R 2(X)W 2(X) T 3: W 3(X) T 4: W 4(X) W 1(X)R 2(X)W 3(X)W 2(X)W 4(X) Assume TS(T 1)=1, TS(T 2)=2, etc. Version V 0 V 1 V 2 V 3 V 4 R_TS 0 1 2 3 2 4 W_TS 0 1 3 2 4 W 1(X) based on V 0 R 2(X) W 3(X) based on V 1 W 2(X) based on V 1 W 4(X) based on V 2

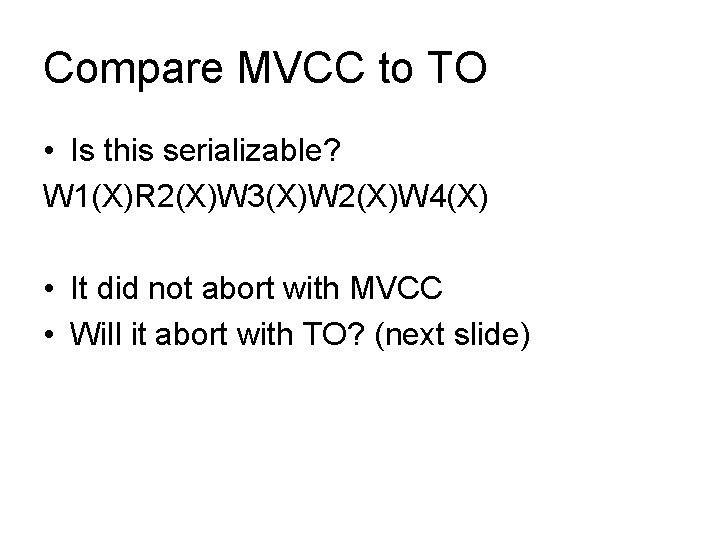

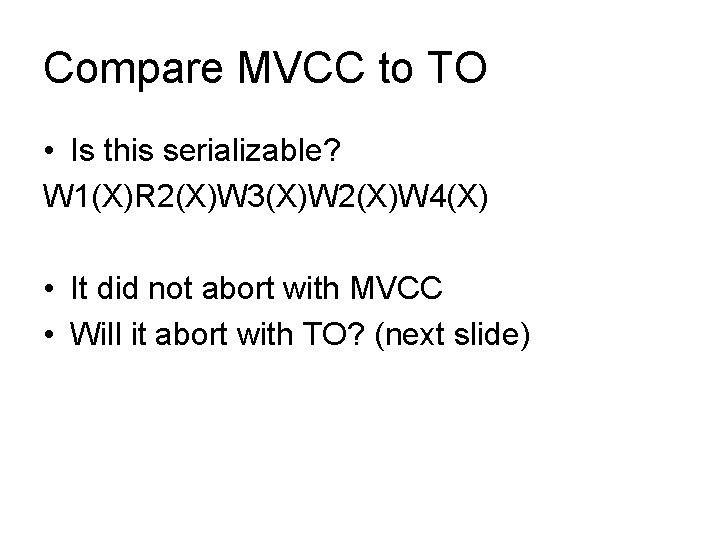

Compare MVCC to TO • Is this serializable? W 1(X)R 2(X)W 3(X)W 2(X)W 4(X) • It did not abort with MVCC • Will it abort with TO? (next slide)

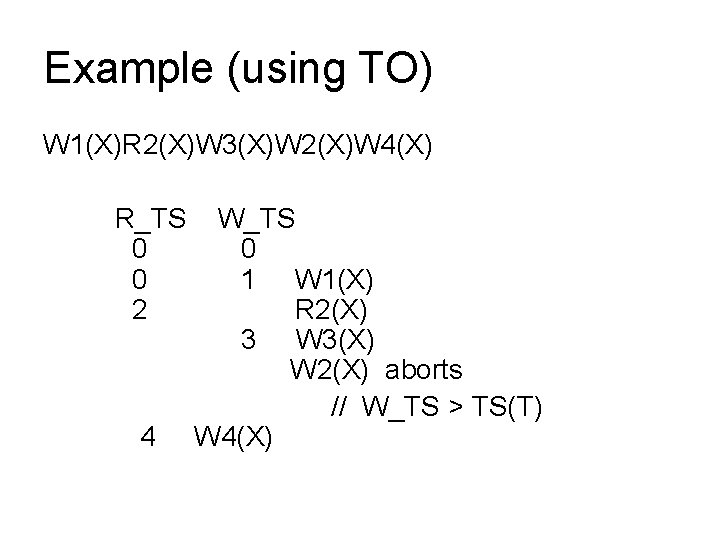

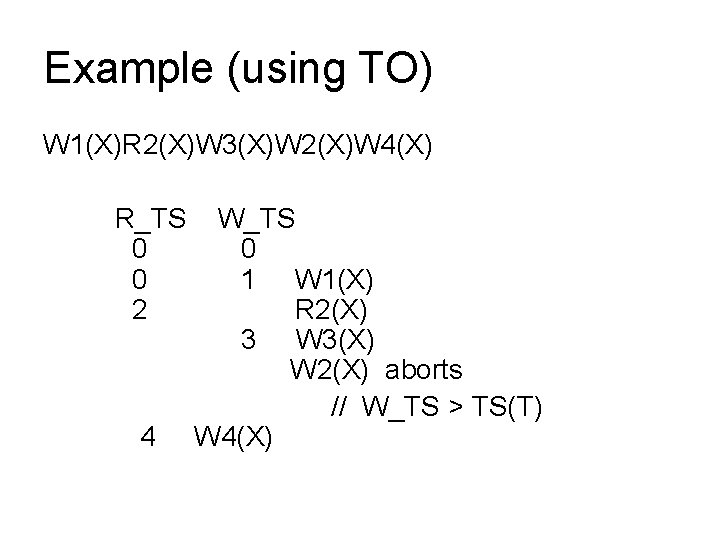

Example (using TO) W 1(X)R 2(X)W 3(X)W 2(X)W 4(X) R_TS 0 0 2 4 W_TS 0 1 W 1(X) R 2(X) 3 W 3(X) W 2(X) aborts // W_TS > TS(T) W 4(X)

View Equivalence and View Serializability Why didn’t MVCC abort with previous schedule? • Less restrictive than conflict equivalence • Premise – As long as each reads a result of the same write 1. the W operations produce the same results 2. the read operations see the same view – If the final write operations are the same, the database state is the same

View equivalence • View equivalent if given 2 schedules, S and S‘ 1. same set of transactions in S and S' (same operations) 2. for any operation on X in S, if value X read has been written by Wj(X), same condition must hold in S' 3. If the operation Wk(Y) is the last operation to write to Y in S, then Wk(Y) must also be the last in S'

Multiversion • How is view equivalence less restrictive? • constrained vs. unconstrained write – constrained - any W 1(X) preceded by R 1(X) – unconstrained - no read before the W 1(X) - independent of any previous value, also called blind write • If the write is constrained, view and conflict equivalence are the same • The difference occurs with blind writes • There is an algorithm to test for view serializability - test is NP-complete • Conflict seralizability is a subset of view seralizability

Multiversion Is the example schedule serializable? W 1(X)R 2(X)W 3(X)W 2(X)W 4(X) T 1 ->T 2 ->T 3 ->(T 3 ->T 2)-> T 4 View equivalent but not conflict equivalent

Multiversion MVCC does abort (seen earlier) W 0(X)R 1(X)W 1(X)R 2(X)R 3(X)W 2(X) Under what circumstances does it abort?

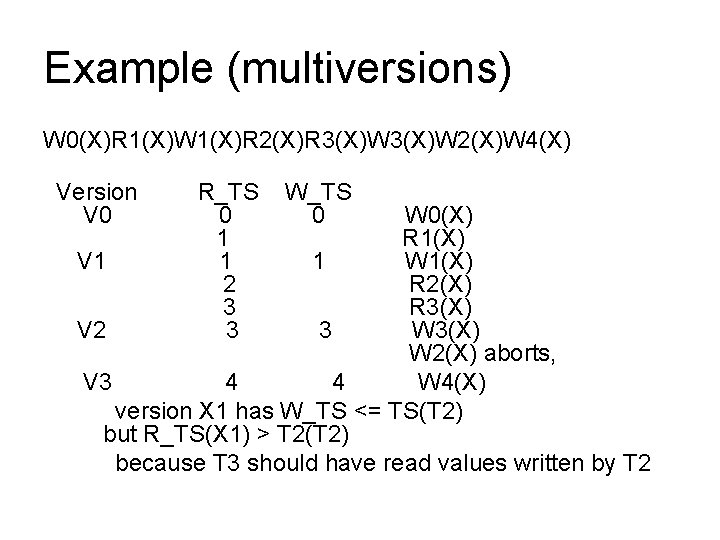

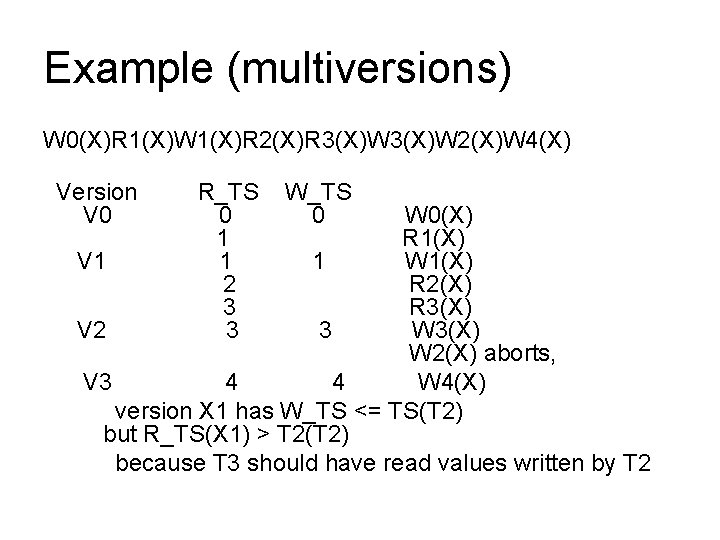

Example (multiversions) W 0(X)R 1(X)W 1(X)R 2(X)R 3(X)W 2(X)W 4(X) Version V 0 R_TS 0 1 1 2 3 3 W_TS 0 W 0(X) R 1(X) V 1 1 W 1(X) R 2(X) R 3(X) V 2 3 W 3(X) W 2(X) aborts, V 3 4 4 W 4(X) version X 1 has W_TS <= TS(T 2) but R_TS(X 1) > T 2(T 2) because T 3 should have read values written by T 2

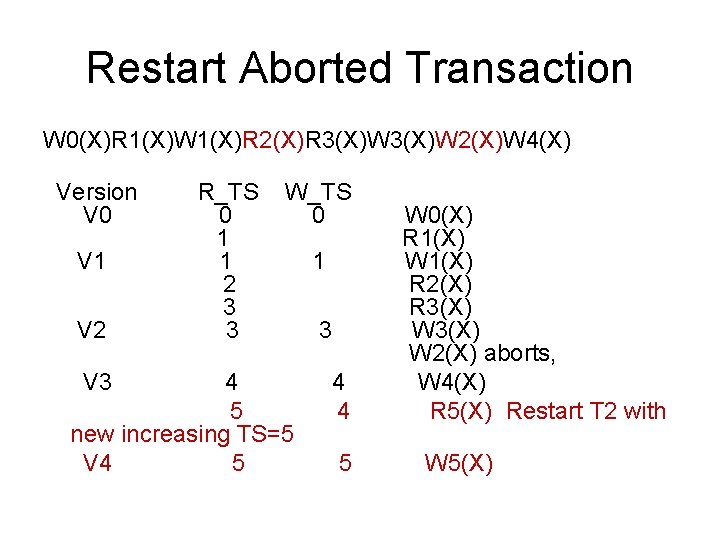

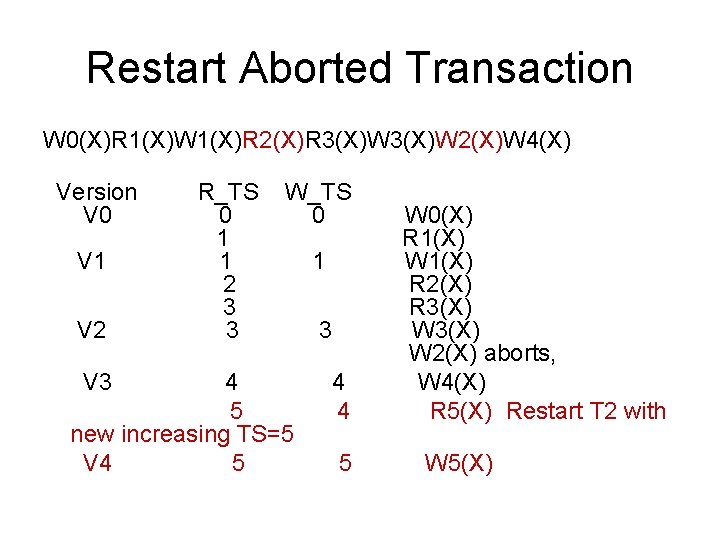

Restart Aborted Transaction W 0(X)R 1(X)W 1(X)R 2(X)R 3(X)W 2(X)W 4(X) Version V 0 V 1 V 2 V 3 R_TS 0 1 1 2 3 3 W_TS 0 4 5 new increasing TS=5 V 4 5 1 3 4 4 5 W 0(X) R 1(X) W 1(X) R 2(X) R 3(X) W 2(X) aborts, W 4(X) R 5(X) Restart T 2 with W 5(X)

• Read eventual consistency paper

Optimistic Concurrency Control

Optimistic • Updates are applied to local copies of the data (transaction workspace) • If serializability is not violated, transactions are committed • The DB is updated from local copies • Otherwise T is aborted and restarted

Validation Concurrency Control Techniques (or certification) • Optimistic (validation) Concurrency Control Techniques (or certification) • In other concurrency control techniques, checking is done to the DB before operations are executed – e. g. TO, 2 PL • In optimistic, checking is done after

Optimistic 3 phases: 1. Local phase – Get copy of data from DB, store locally – R/W to local copies 2. Validation phase - check for serializability 3. Write phase if validation successful, write to DB and transaction committed else restart transaction

Optimistic • If little interference, T's validated successfully and optimistic protocol works well else lots of interference, so optimistic doesn’t work well • This protocol (there are others) uses Wsets and R-sets • W set different from W phase

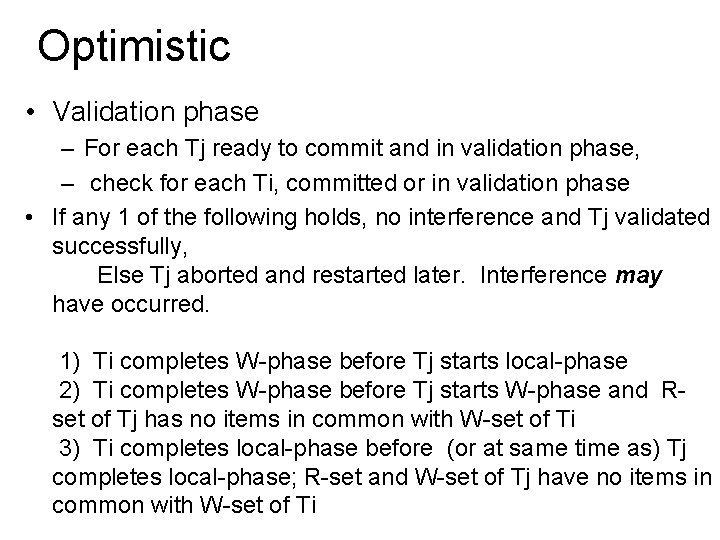

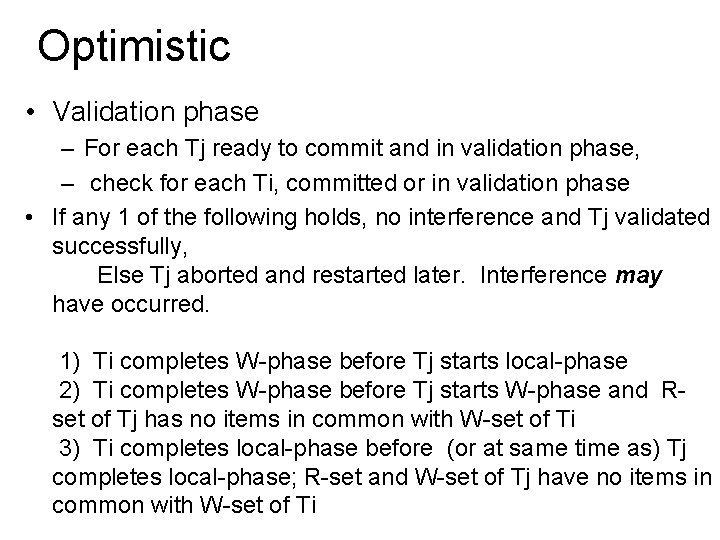

Optimistic • Validation phase – For each Tj ready to commit and in validation phase, – check for each Ti, committed or in validation phase • If any 1 of the following holds, no interference and Tj validated successfully, Else Tj aborted and restarted later. Interference may have occurred. 1) Ti completes W-phase before Tj starts local-phase 2) Ti completes W-phase before Tj starts W-phase and Rset of Tj has no items in common with W-set of Ti 3) Ti completes local-phase before (or at same time as) Tj completes local-phase; R-set and W-set of Tj have no items in common with W-set of Ti

Optimistic Analysis 1) No overlap 2) Tj does not ready anything written by Ti and if Ti reads something written by Tj, Ti will read local copy instead so Ti << Tj no cycle 3) Tj cannot read or write to anything Ti has written to because the interleaved schedule may have a lost update instead it forces an order Ti << Tj

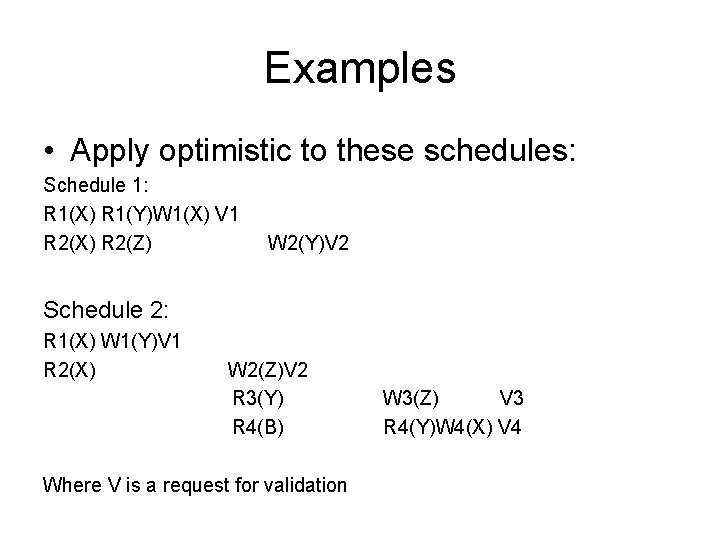

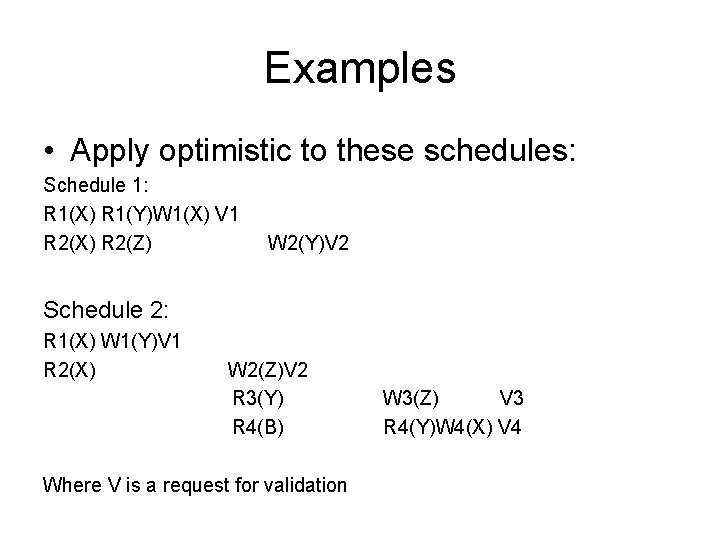

Examples • Apply optimistic to these schedules: Schedule 1: R 1(X) R 1(Y)W 1(X) V 1 R 2(X) R 2(Z) W 2(Y)V 2 Schedule 2: R 1(X) W 1(Y)V 1 R 2(X) W 2(Z)V 2 R 3(Y) R 4(B) Where V is a request for validation W 3(Z) V 3 R 4(Y)W 4(X) V 4

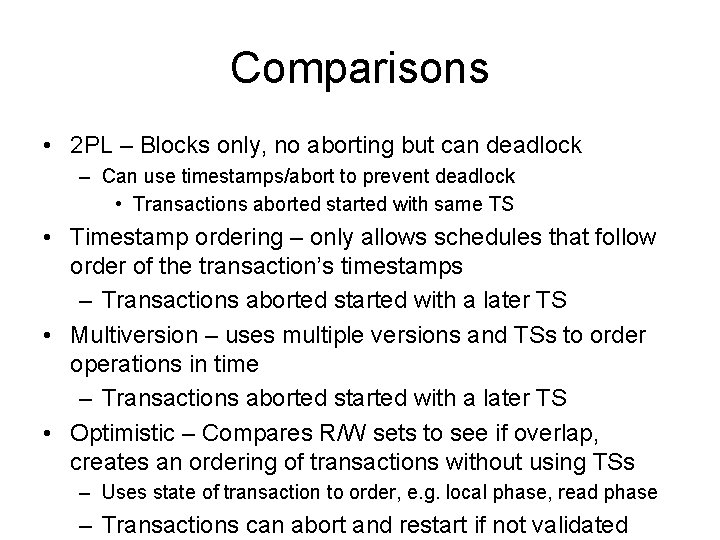

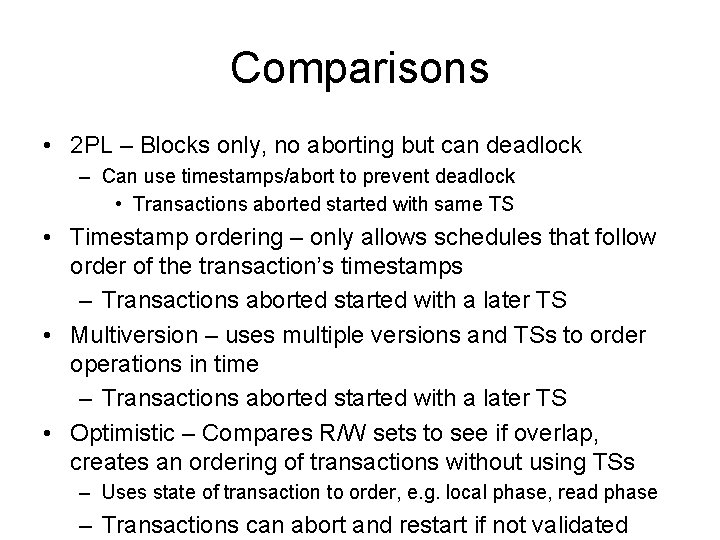

Comparisons • 2 PL – Blocks only, no aborting but can deadlock – Can use timestamps/abort to prevent deadlock • Transactions aborted started with same TS • Timestamp ordering – only allows schedules that follow order of the transaction’s timestamps – Transactions aborted started with a later TS • Multiversion – uses multiple versions and TSs to order operations in time – Transactions aborted started with a later TS • Optimistic – Compares R/W sets to see if overlap, creates an ordering of transactions without using TSs – Uses state of transaction to order, e. g. local phase, read phase – Transactions can abort and restart if not validated

Is Concurrency Control relevant? • http: //docs. oracle. com/cd/B 10500_01/server. 920/a 96524 /c 21 cnsis. htm • http: //dev. mysql. com/doc/refman/5. 0/en/tablelocking. html