Computer Fraud and Abuse Act CFAA An Overview

Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) An Overview of the Federal Computer Fraud and Abuse Statute By: Julius Noble Ssekazinga

Abstract The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986 ("CFAA") criminalizes unauthorized access to information stored on computers and allows for those who are damaged by such unauthorized access to bring a civil suit against the abuser (Milanowski, 2015). The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA), 18 U. S. C. 1030, outlaws the actions of computer networks being abused. This is a regulation relating to information security. This supports internet-connected devices, bank devices and federal computers. It shields them from infiltration, intimidation, injury, spying and from being used corruptly as instruments of fraud.

Introduction The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) was enacted in 1986, to address hacking, as an enhancement to the first Federal Computer Fraud Act. It has been amended several times over the years, most recently in 2008, to cover a wide range of behavior, far beyond its original intent. The CFAA Prohibits deliberate access to a device without or beyond authorisation, but fails to specify what "without authorisation" entails. It has become a device ripe for violence and use against almost any type of computer operation, with strict penalty schemes and malleable provisions.

As technology advances, also advances the use of criminal law to regulate behavior using such technology. Perceptions about the role of technology in both conventional and high-tech criminal activity motivated Congress to pass the first federal law on computer crime 30 years ago. Nevertheless, changes in computer quality and widespread use have driven computer behavior to overdrive through government regulation. The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) was enacted in 1986, to counter hacking as an enhancement to the first federal legislation on computer fraud. It has been updated many times over the years, most recently in 2008, to encompass a wide variety of behaviors, well beyond its original purpose.

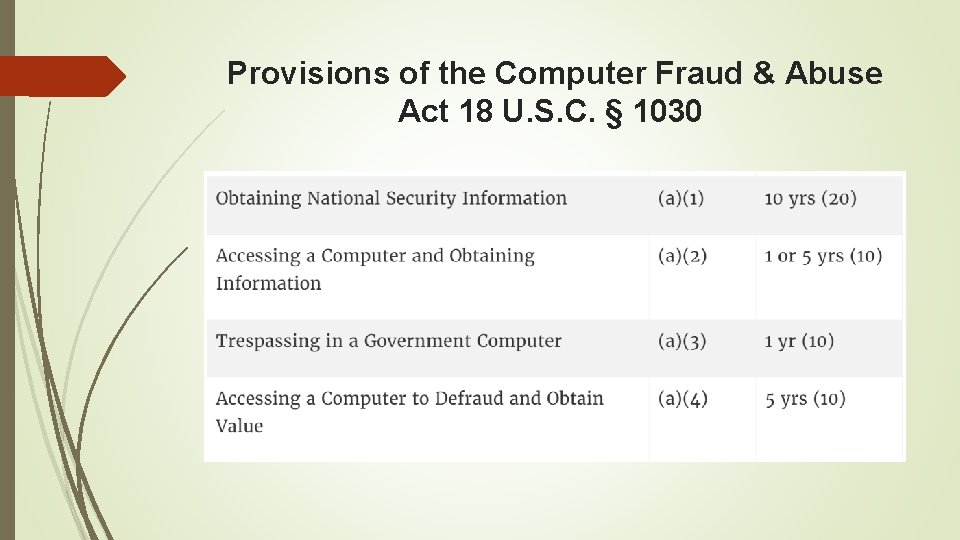

The seven paragraphs of subsection 1030(a) outlaw computer trespassing in a government computer, 18 U. S. C. 1030(a)(3); computer trespassing resulting in exposure to certain governmental, credit, financial, or computer-housed information, 18 U. S. C. 1030(a)(2); damaging a government computer, a bank computer, or a computer used in, or affecting, interstate or foreign commerce, 18 U. S. C. 1030(a)(5); committing fraud an integral part of which involves unauthorized access to a government computer, a bank computer, or a computer used in, or affecting, interstate or foreign commerce, 18 U. S. C. 1030(a)(4);

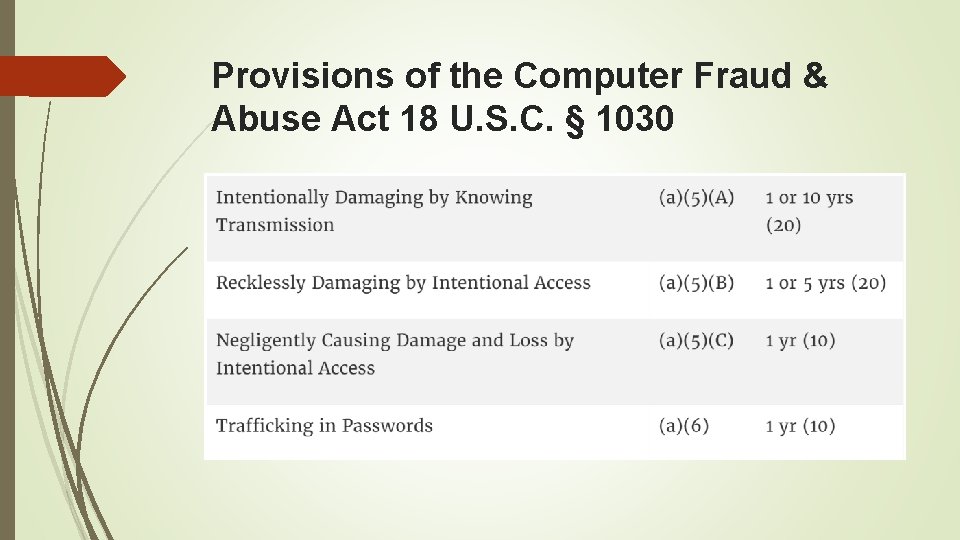

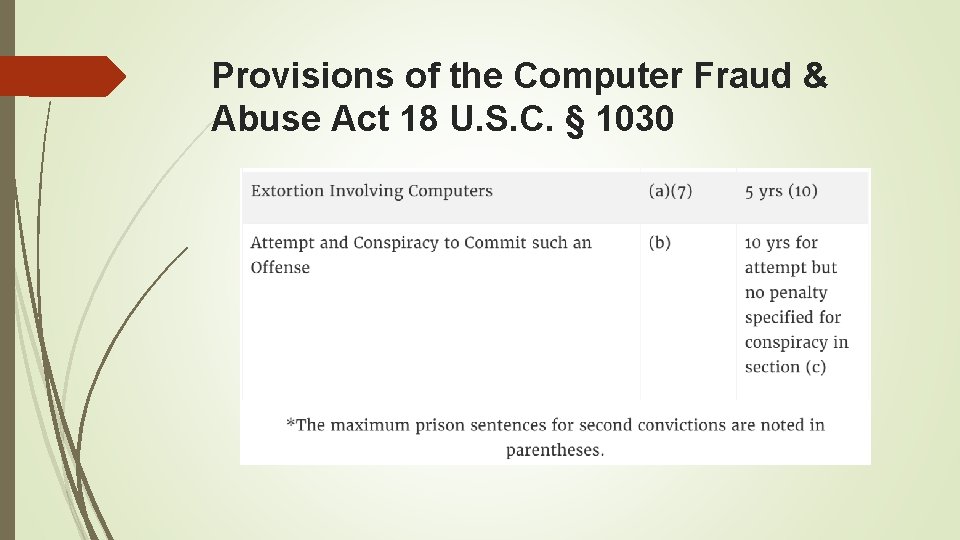

The seven paragraphs of subsection 1030(a) outlaw (. . . continued) threatening to damage a government computer, a bank computer, or a computerused in, or affecting, interstate or foreign commerce, 18 U. S. C. 1030(a)(7); trafficking in passwords for a government computer, or when the traffickingaffects interstate or foreign commerce, 18 U. S. C. 1030(a)(6); accessing a computer to commit espionage, 18 U. S. C. 1030(a)(1).

Challenges of CFAA According (BERG, 2020) to the CFAA Protects users from inappropriately accessing a "safe device, " which may include only a limited subset of computers (think secure email servers that the state department uses). The CFAA does not criminalize mere terms-of-service Consumer Web Violations. In 1996, When the CFAA was revised to include all computers with Internet access as "safe, " a stated minimum harm of $5, 000 resulted unless the hacker had interfered with health care or posed a threat to national security. When the loss may not surpass that level, the courts will not be able to make compromises for going ahead with a lawsuit.

Challenges of CFAA (. . . continued) The CFAA criterion for whether a computer user is actually performing infringements is especially maleable. CFAA violations that occur if access is either "without authorization" or "exceeding authorization, " but the latter has a statutory circular meaning. Ultimately, blurred statutory boundaries protecting these legal interests raise questions as to whether the CFAA provides adequate clarity to potential defendants as to what conduct is prohibited. The CFAA is also posing a question of overcriminalization. The courts have (until recently) slowly extended the spectrum of possible CFAA liability to include malpractice which is not obviously violation or hacking There's also code issue here. It is not illegal to write malicious code but to use the code is. If a third party uses a code that someone else has developed, who is to blame?

Provisions of the Computer Fraud & Abuse Act 18 U. S. C. § 1030

Provisions of the Computer Fraud & Abuse Act 18 U. S. C. § 1030

Provisions of the Computer Fraud & Abuse Act 18 U. S. C. § 1030

Conclusion Today, the field of work is filled with various CFAA jurisdictional definitions. Employers must therefore be aware of the split in authority to protect their computer systems, trade secrets and confidential information appropriately. For example, For those jurisdictions where the CFAA is widely applied, employers should clearly identify all the words for their employee manuals and decide what sensitive information is misused. Such extensive records can be sufficient to show, in addition to a training program, that an employee was informed and understood the rules by which he or she was governed. Congress intended to fight hacking for the CFAA, but as society continues to evolve and use advanced technology , companies need to address new computer and sensitive information issues. For two separate implementation requirements, the courts lack clear guidelines as to where they will fall within the continuum.

References Milanowski, J. (2015). A Threat to or Protection of Agency Relationships? The Impact of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act on Businesses. Papers. ssrn. com. Retrieved 23 July 2020, from https: //papers. ssrn. com/sol 3/papers. cfm? abstract_id=2693836. BERG, M. (2020). CFAA (Computer Fraud and Abuse Act): Challenges Faced by Prosecutors - San Diego Criminal Defense Blog. Retrieved 23 July 2020, from https: //sandiego. criminallaw. com/blog/cfaa-computer-fraud-and-abuse-actchallenges-faced-by-prosecutors See United States v. Rodriguez, 628 F. 3 d 1258 (11 th Cir. 2010) (misuse of Social Security Administration computers); United States v. John, 597 F. 3 d 263 (5 th Cir. 2010) (exceeding authorization in furtherance of a fraud crime); Int’l Airport Ctrs. , LLC v. Citrin, 440 F. 3 d 418 (7 th Cir. 2006) (Posner, J. )

References (. . . continued) See Orin S. Kerr, Cybercrime’s Scope: Interpreting “Access” and “Authorization” in Computer Misuse Statutes, 78 N. Y. U. L. Rev. 1596, 1598 -99 (2003) Sean Gallagher, A hacked DDo. S-on-demand site offers a look into mind of “booter” users, Ars Technica, Retrieved 23 July 2020, http: //arstechnica. com/security/2015/01/a-hacked-ddos-on-demand-site-offers-alook-into-mind-of-booter-users Computer intrusion law is thus far from a specialized form of “cyberlaw” that Frank Easterbrook famously derided as “the Law of the Horse. ” Frank H. Easterbrook, Cyberspace and the Law of the Horse, 1996 U. Chi. Legal F. 207 (1996)

- Slides: 14