Computer Architecture Lecture Notes Spring 2005 Dr Michael

- Slides: 48

Computer Architecture Lecture Notes Spring 2005 Dr. Michael P. Frank (New) Competency Area 6: Introduction to Pipelining

Basic Pipelining Concepts P&H 3 rd ed. , Chapter 6 H&P 3 rd ed. §A. 1

Pipelining - The Basic Concept • In early CPUs, deep combinational logic networks were used in between state updates. – Signal delays may vary widely across different paths. – New input cannot be provided to the network until the slowest paths have finished. – Slow clock speed, slow overall processing rates. • In pipelined design, deep logic networks are subdivided into relatively shallow slices (pipeline stages). – Delays through the network are made uniform. – A new input can be provided to each slice as soon as its quick, shallow network has finished. – Multiple inputs are processed simultaneously across stages. – Clock cycle is only as long as the slowest pipeline stage.

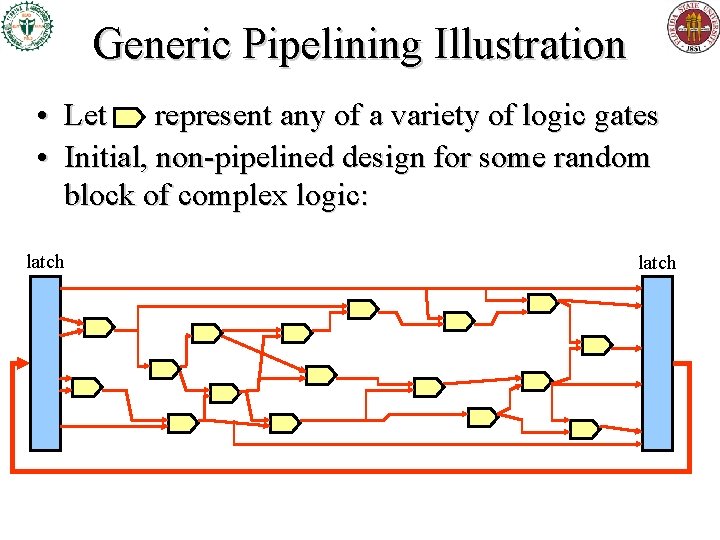

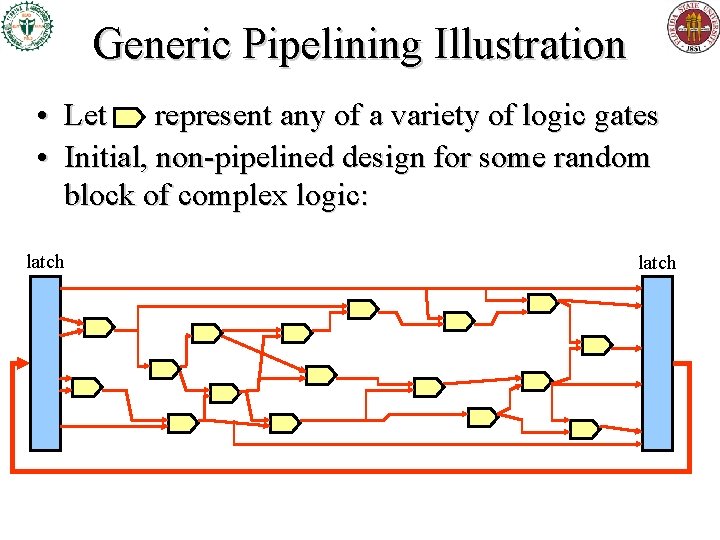

Generic Pipelining Illustration • Let represent any of a variety of logic gates • Initial, non-pipelined design for some random block of complex logic: latch

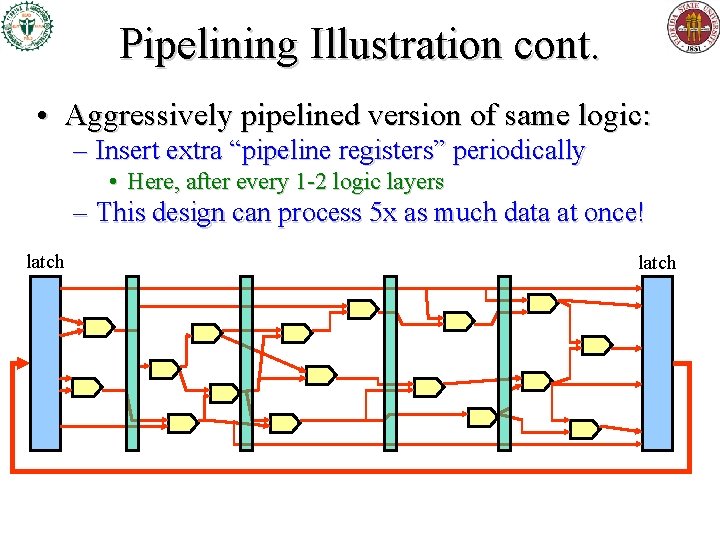

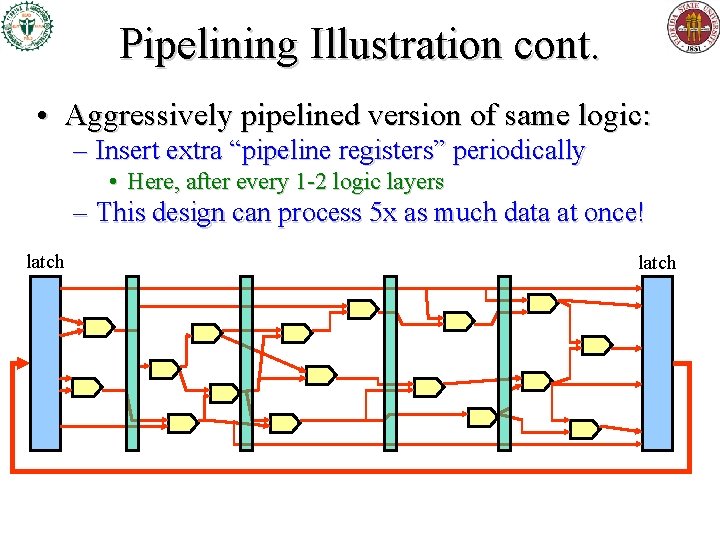

Pipelining Illustration cont. • Aggressively pipelined version of same logic: – Insert extra “pipeline registers” periodically • Here, after every 1 -2 logic layers – This design can process 5 x as much data at once! latch

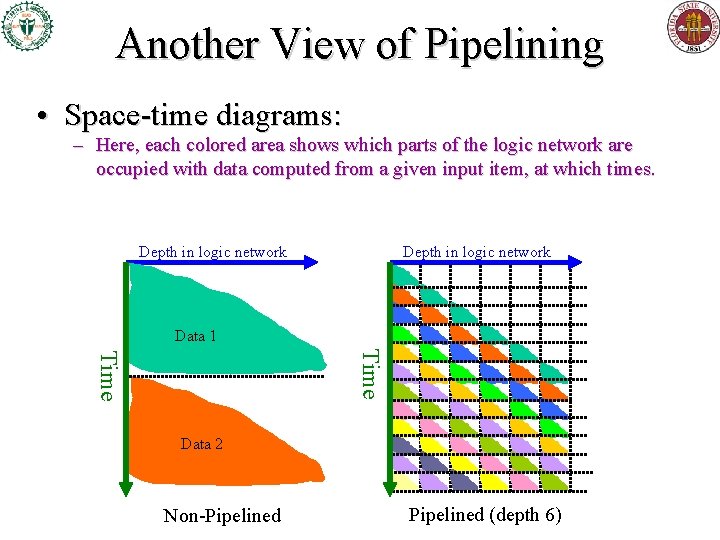

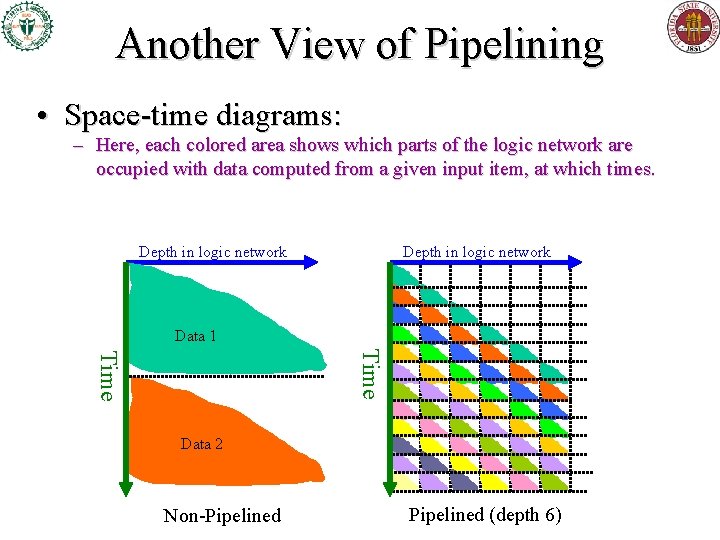

Another View of Pipelining • Space-time diagrams: – Here, each colored area shows which parts of the logic network are occupied with data computed from a given input item, at which times. Depth in logic network Data 1 Time Data 2 Non-Pipelined (depth 6)

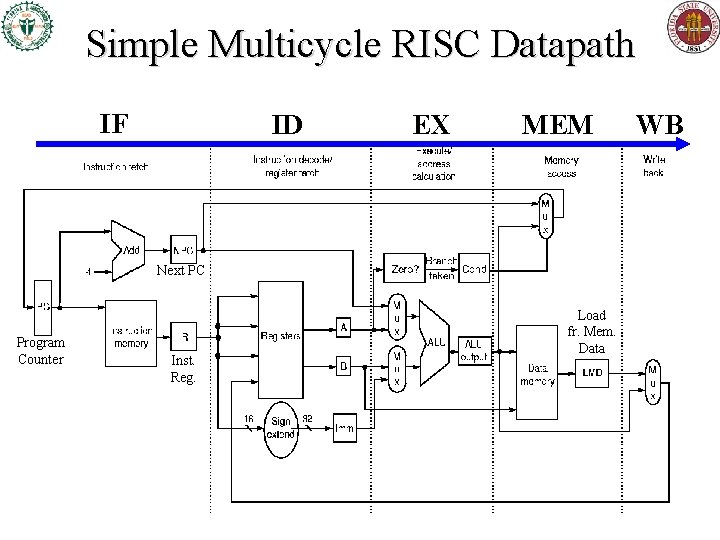

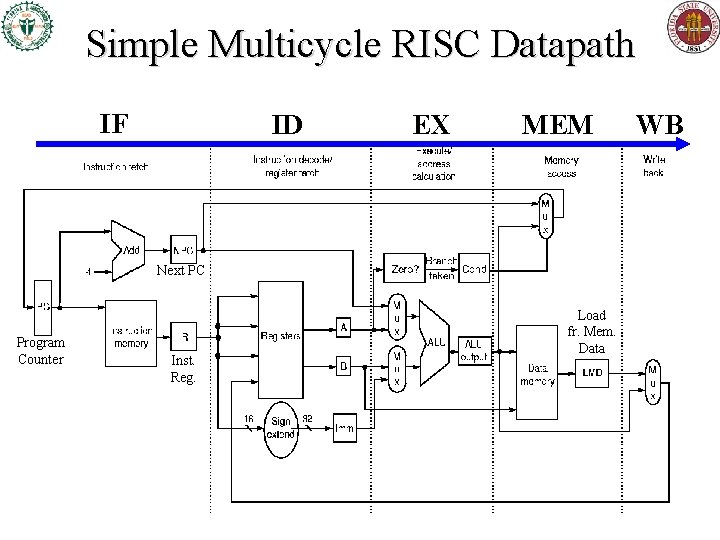

Simple Multicycle RISC Datapath IF ID EX MEM Next PC Program Counter Inst. Reg. Load fr. Mem. Data WB

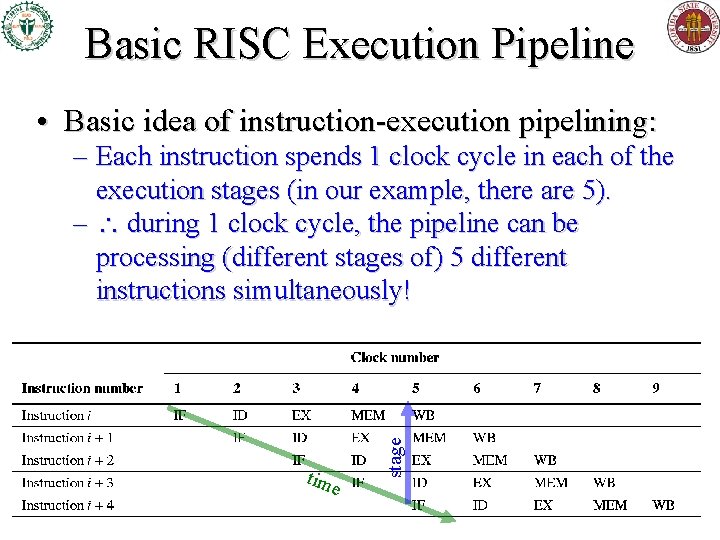

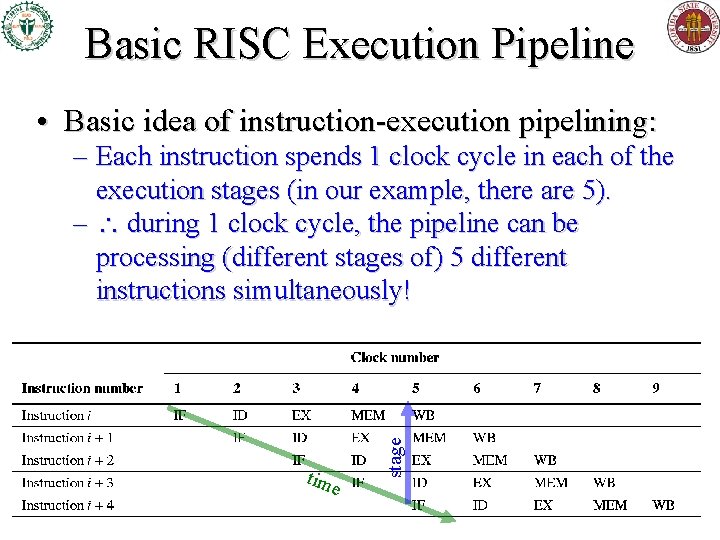

Basic RISC Execution Pipeline • Basic idea of instruction-execution pipelining: tim e stage – Each instruction spends 1 clock cycle in each of the execution stages (in our example, there are 5). – during 1 clock cycle, the pipeline can be processing (different stages of) 5 different instructions simultaneously!

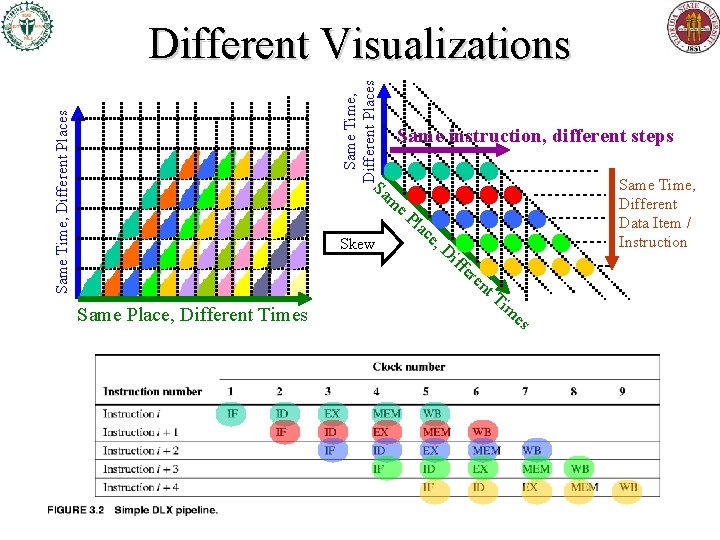

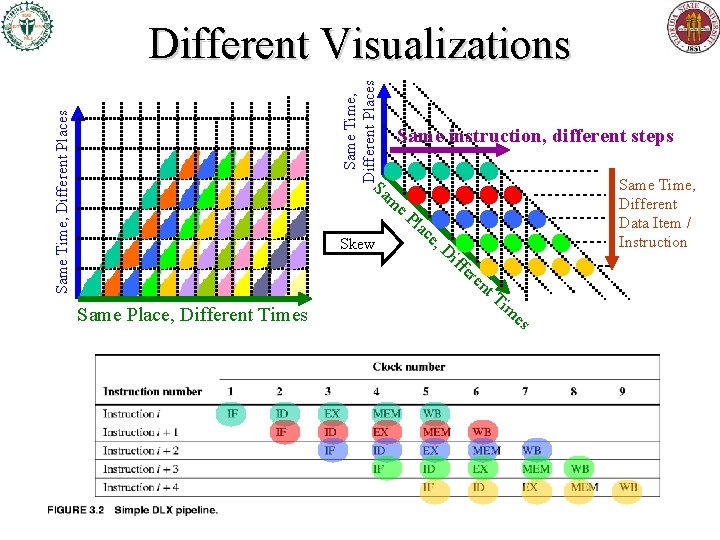

Same Time, Different Places Different Visualizations Same instruction, different steps Sa Same Time, Different Data Item / Instruction m e. P Skew Same Place, Different Times lac e, Di ffe re nt Ti m es

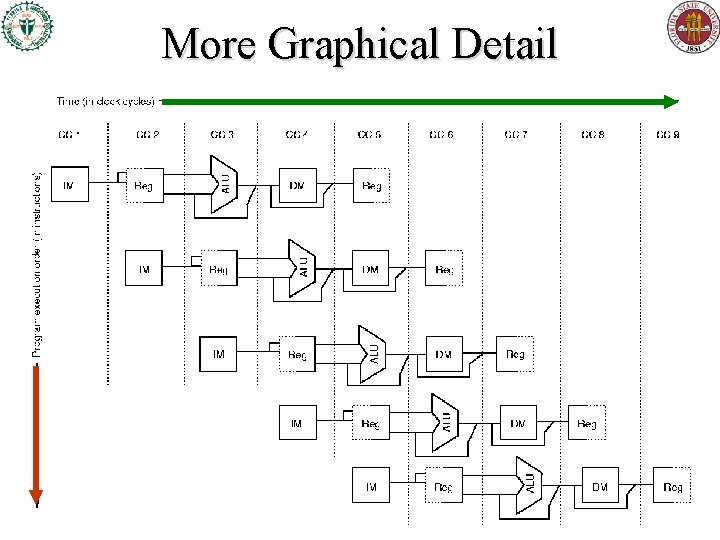

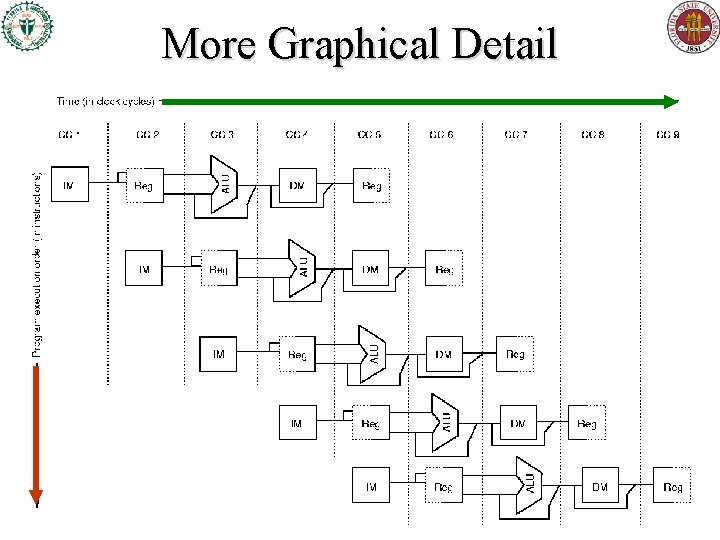

More Graphical Detail

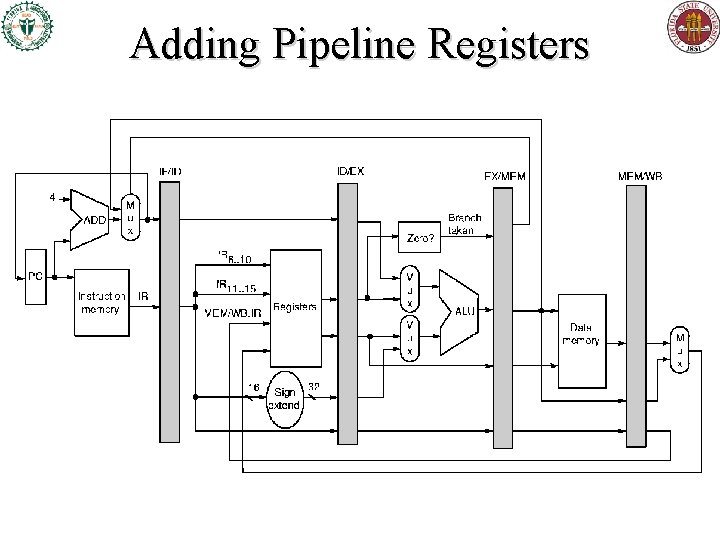

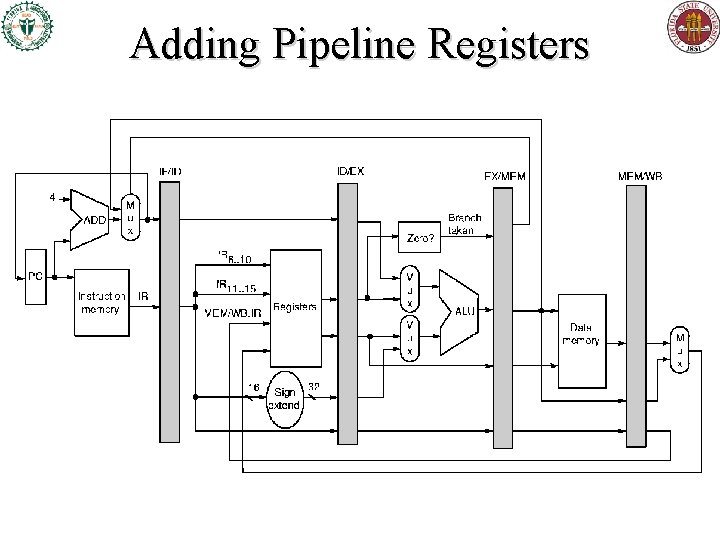

Adding Pipeline Registers

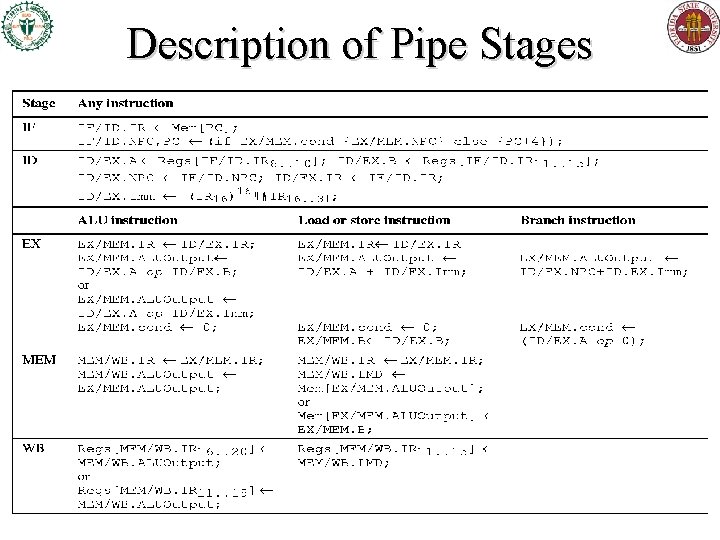

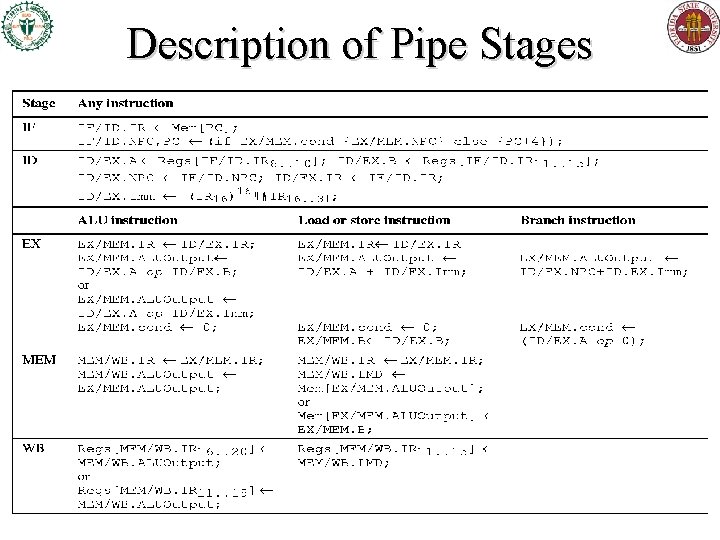

Description of Pipe Stages

Dependences (from H&P 3 rd ed. § 3. 1)

Dependences • A dependence is a way in which one instruction can depend on (be impacted by) another for scheduling purposes. • Three major dependence types: – Data dependence – Name dependence – Control dependence • I’ll sometimes use the word dependency for a particular instance of one instruction depending on another. – The instructions can’t be effectively (as opposed to just syntactically) fully parallelized, or reordered.

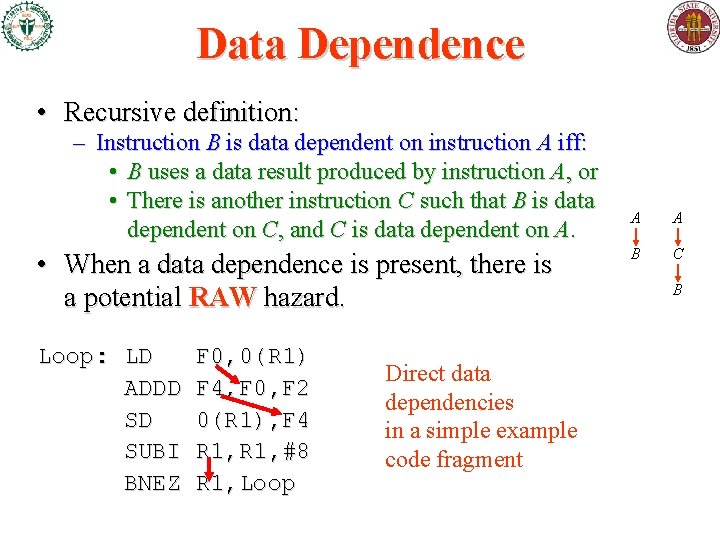

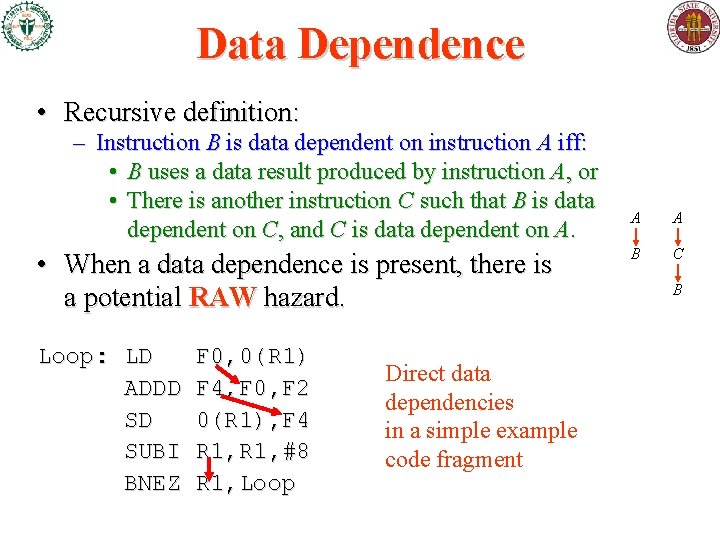

Data Dependence • Recursive definition: – Instruction B is data dependent on instruction A iff: • B uses a data result produced by instruction A, or • There is another instruction C such that B is data dependent on C, and C is data dependent on A. • When a data dependence is present, there is a potential RAW hazard. Loop: LD ADDD SD SUBI BNEZ F 0, 0(R 1) F 4, F 0, F 2 0(R 1), F 4 R 1, #8 R 1, Loop Direct data dependencies in a simple example code fragment A A B C B

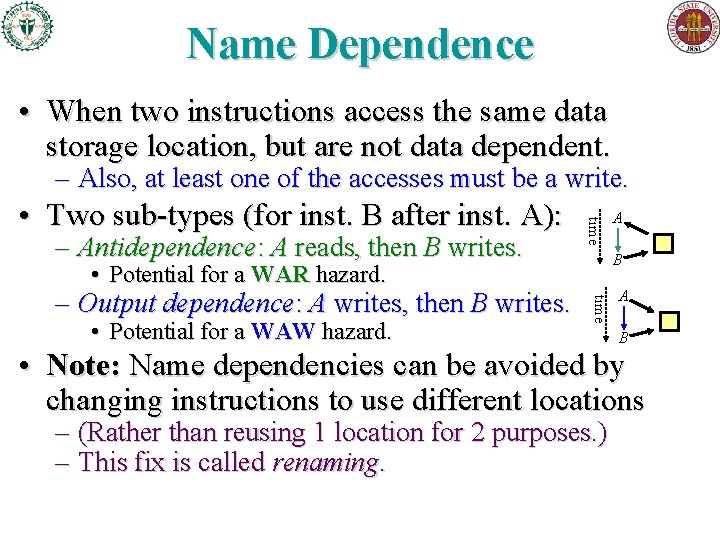

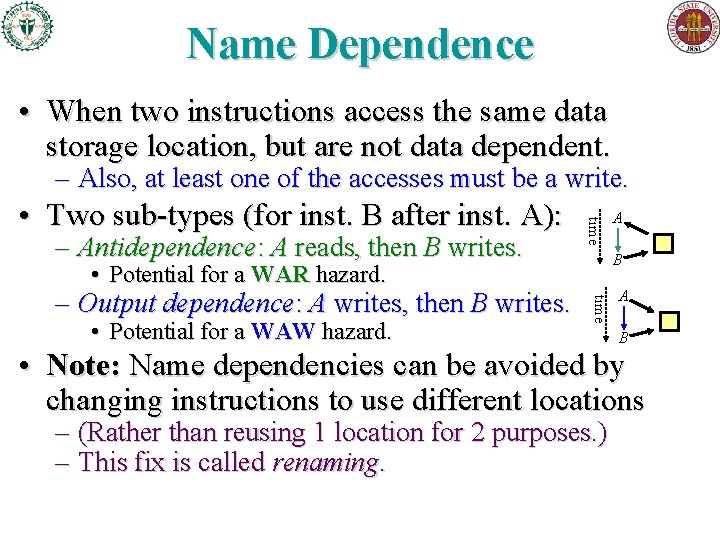

Name Dependence • When two instructions access the same data storage location, but are not data dependent. – Also, at least one of the accesses must be a write. – Antidependence: A reads, then B writes. time • Two sub-types (for inst. B after inst. A): B • Potential for a WAR hazard. • Potential for a WAW hazard. time – Output dependence: A writes, then B writes. A A B • Note: Name dependencies can be avoided by changing instructions to use different locations – (Rather than reusing 1 location for 2 purposes. ) – This fix is called renaming.

Control Dependence • Occurs when the execution of an instruction (as in, will it be executed, or not? ) depends on the outcome of some earlier, conditional branch instruction. • We generally can’t easily change which branches an instruction depends on w/o ruining the program’s functional behavior. • However, there are exceptions.

Hazards, Stalls, & Forwarding H&P 3 rd ed. §A. 2 -3

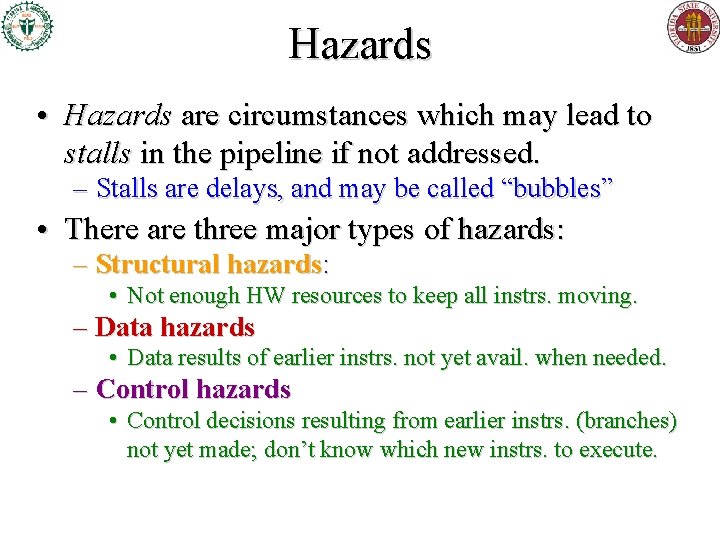

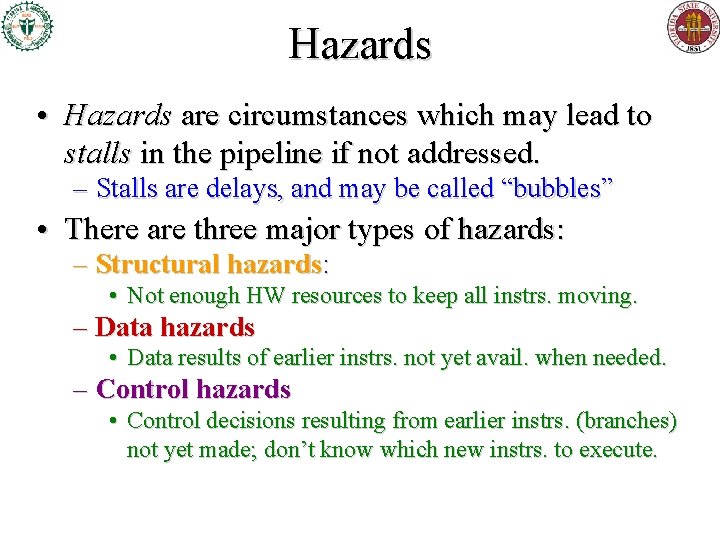

Hazards • Hazards are circumstances which may lead to stalls in the pipeline if not addressed. – Stalls are delays, and may be called “bubbles” • There are three major types of hazards: – Structural hazards: • Not enough HW resources to keep all instrs. moving. – Data hazards • Data results of earlier instrs. not yet avail. when needed. – Control hazards • Control decisions resulting from earlier instrs. (branches) not yet made; don’t know which new instrs. to execute.

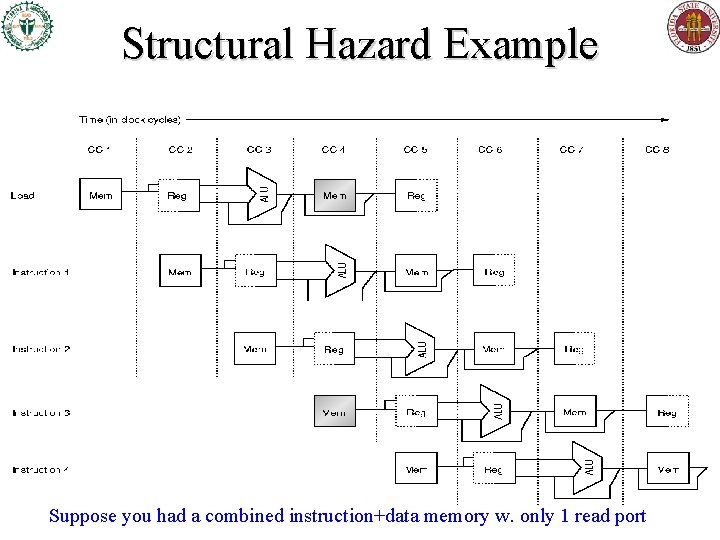

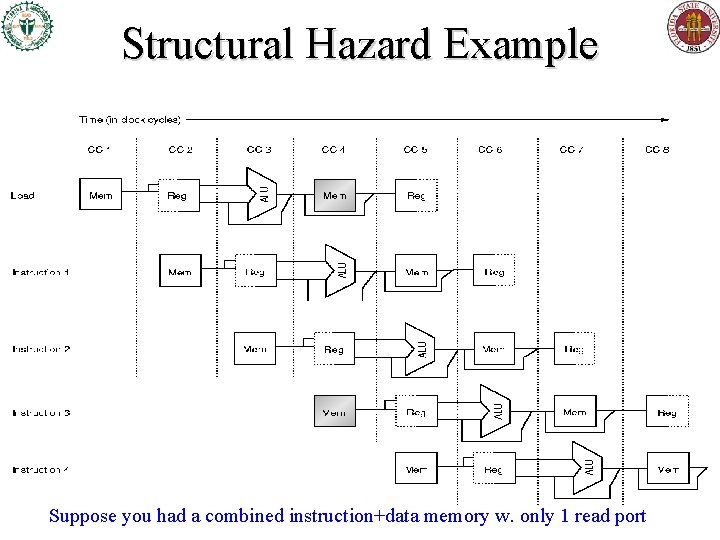

Structural Hazard Example Suppose you had a combined instruction+data memory w. only 1 read port

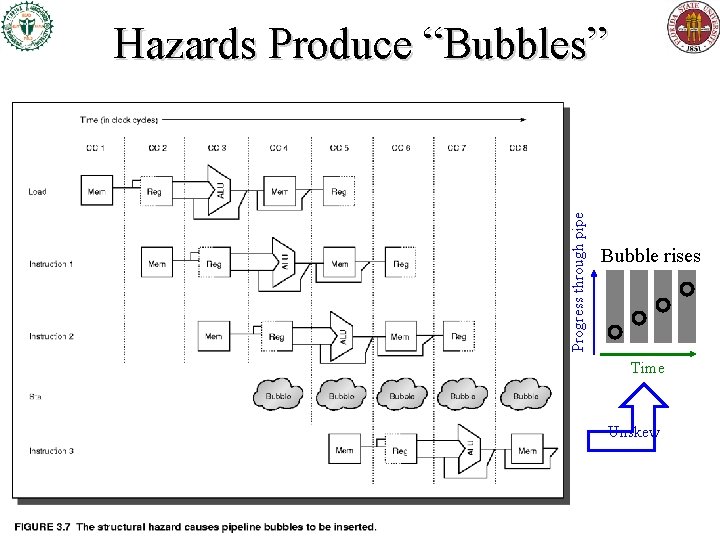

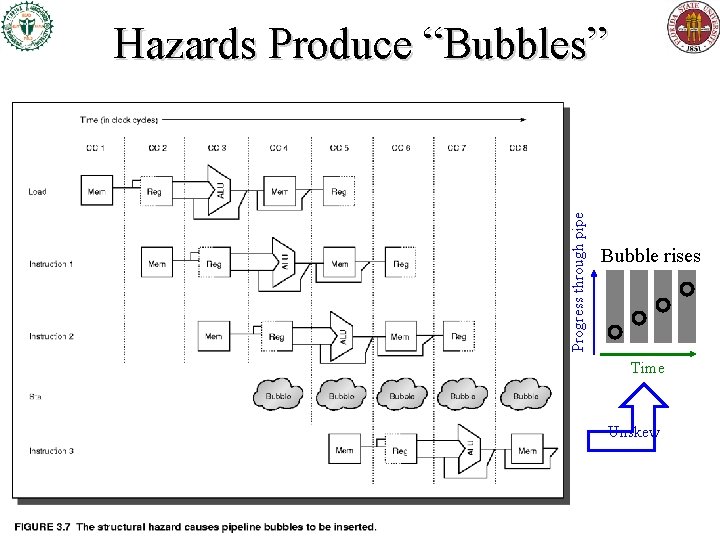

Progress through pipe Hazards Produce “Bubbles” Bubble rises Time Unskew

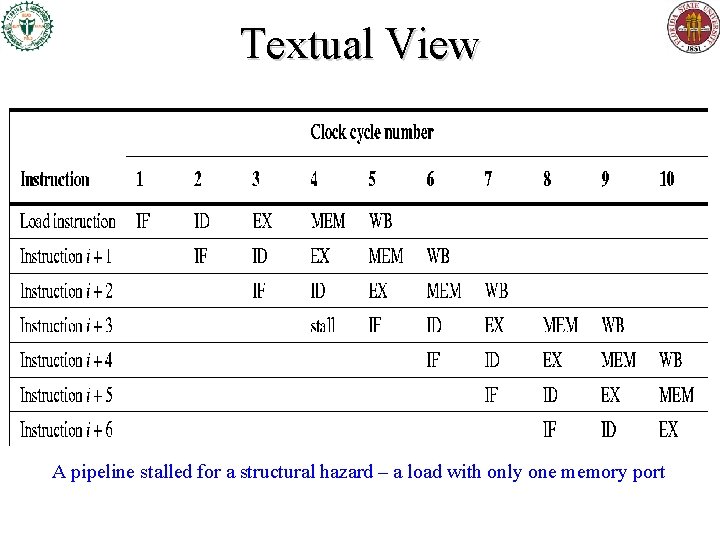

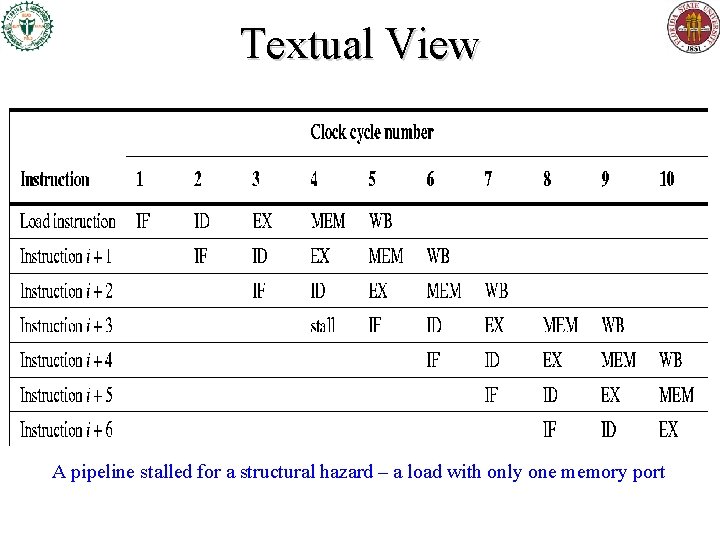

Textual View A pipeline stalled for a structural hazard – a load with only one memory port

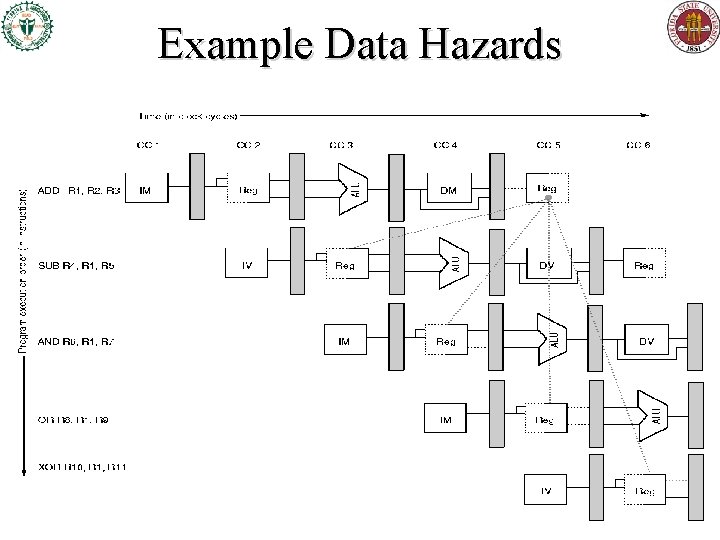

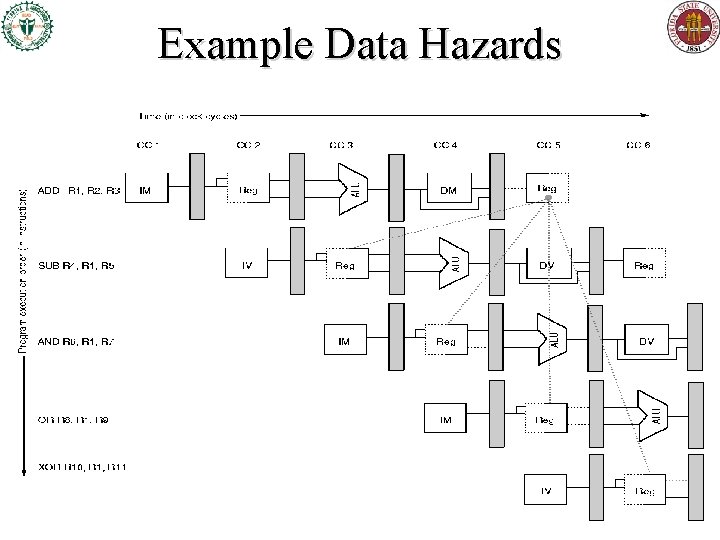

Example Data Hazards

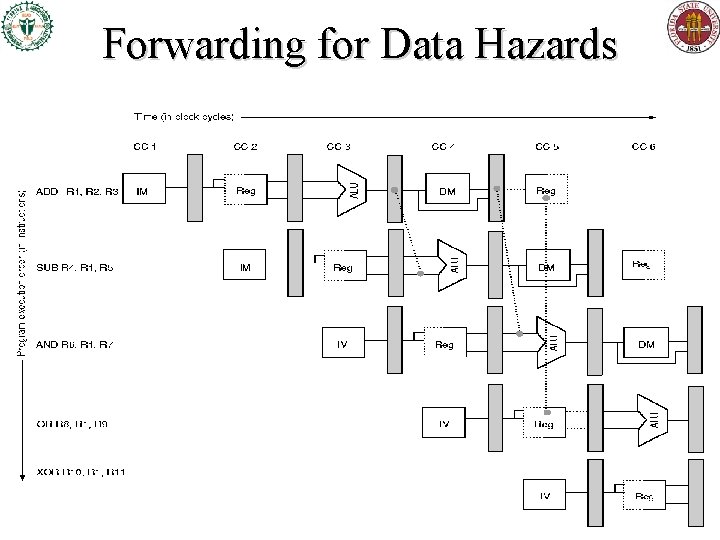

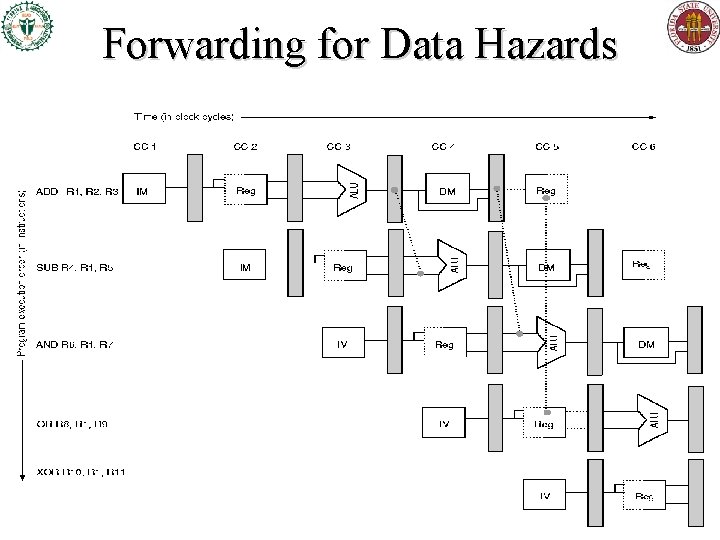

Forwarding for Data Hazards

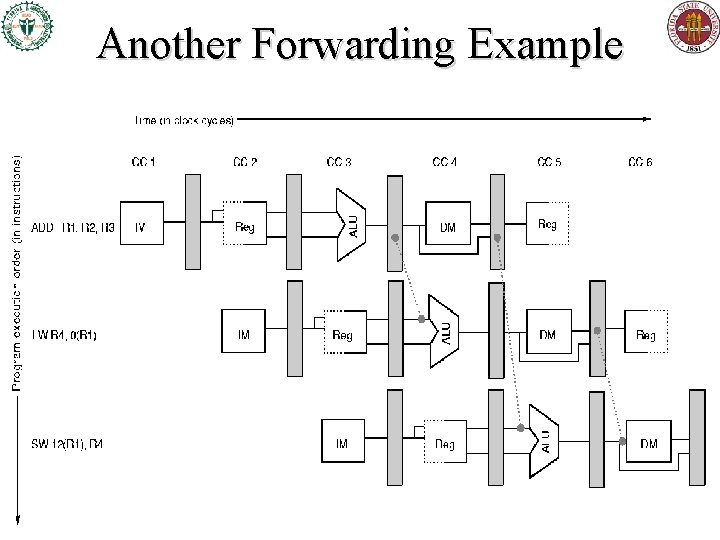

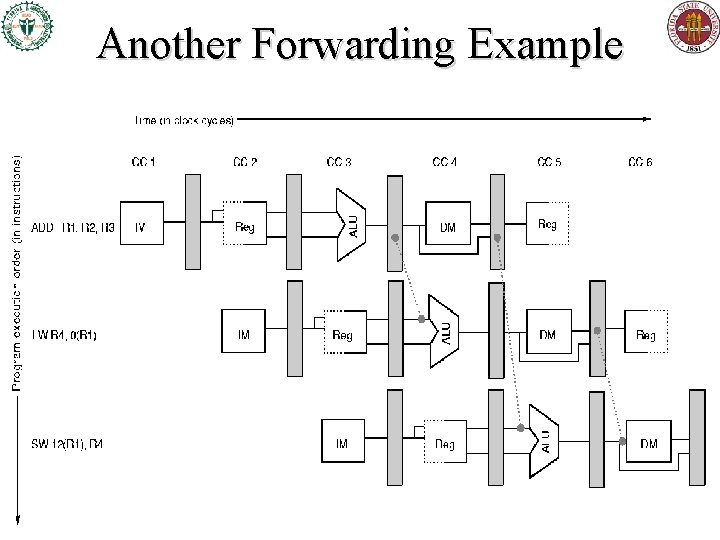

Another Forwarding Example

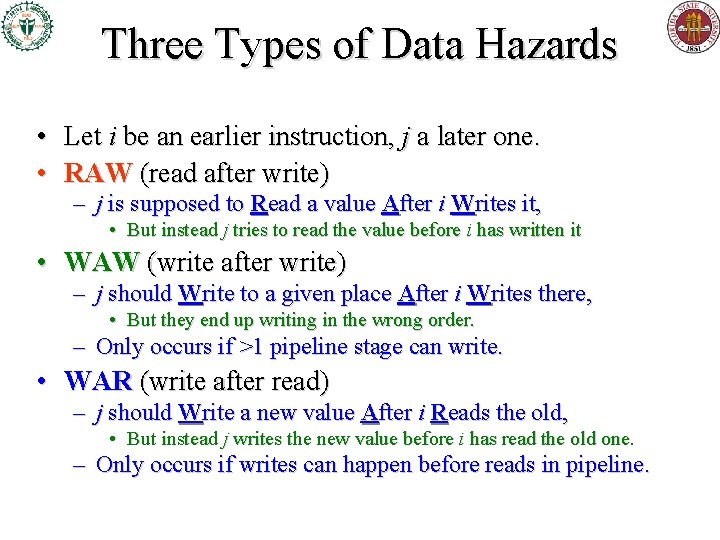

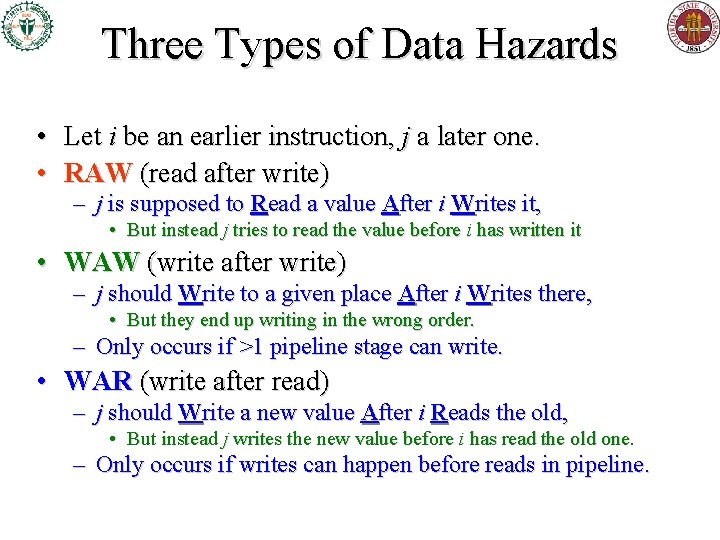

Three Types of Data Hazards • Let i be an earlier instruction, j a later one. • RAW (read after write) – j is supposed to Read a value After i Writes it, • But instead j tries to read the value before i has written it • WAW (write after write) – j should Write to a given place After i Writes there, • But they end up writing in the wrong order. – Only occurs if >1 pipeline stage can write. • WAR (write after read) – j should Write a new value After i Reads the old, • But instead j writes the new value before i has read the old one. – Only occurs if writes can happen before reads in pipeline.

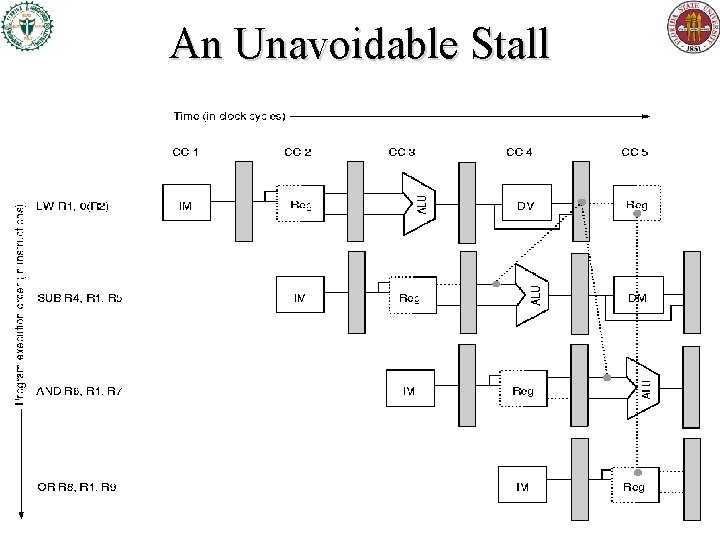

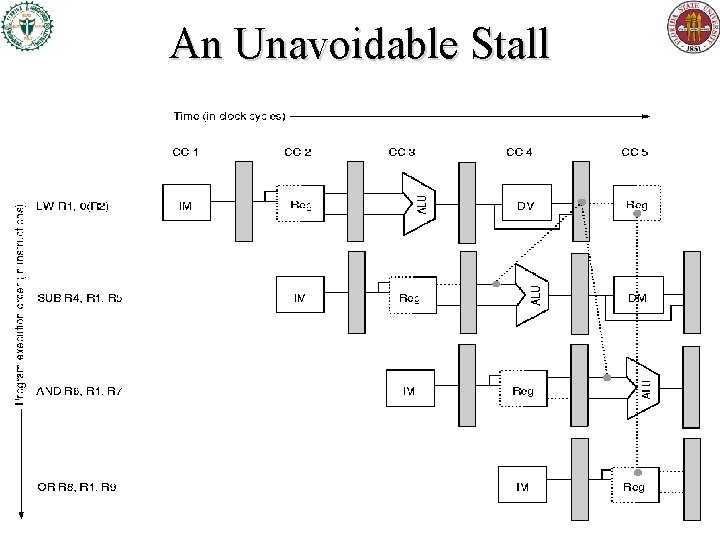

An Unavoidable Stall

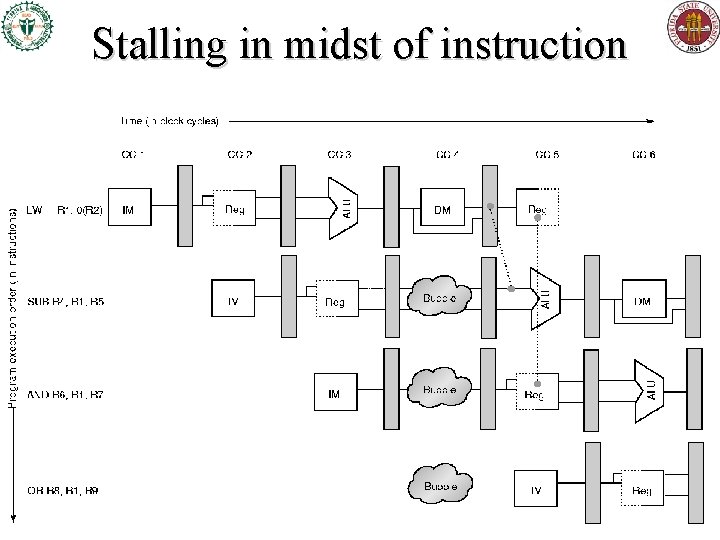

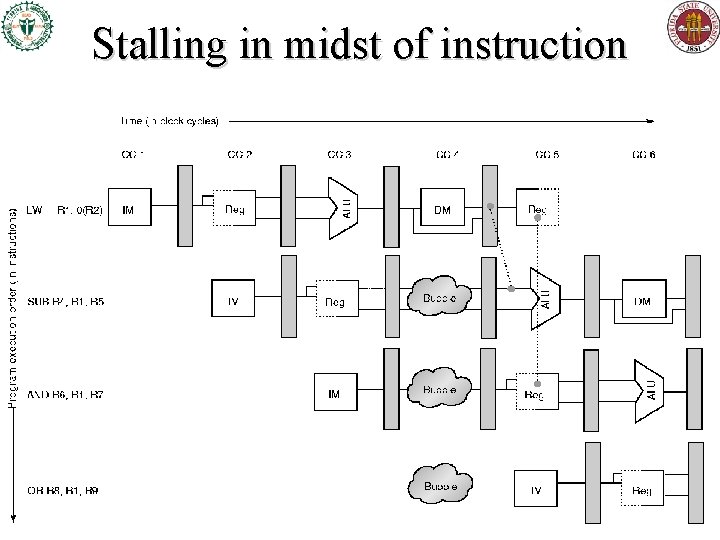

Stalling in midst of instruction

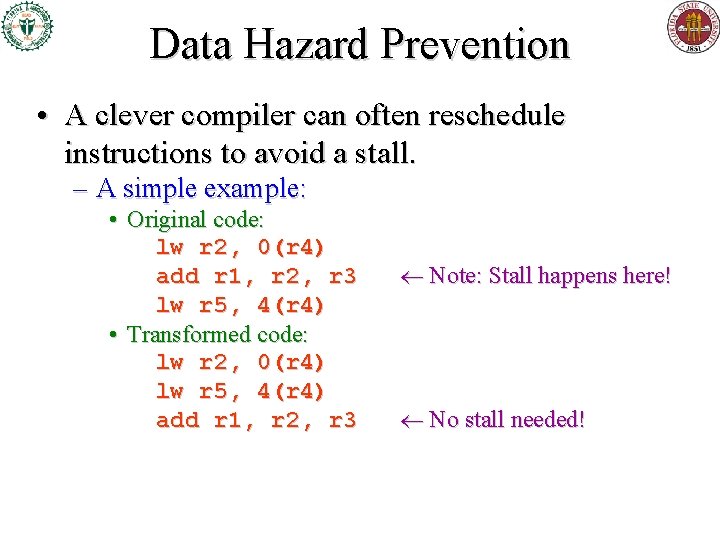

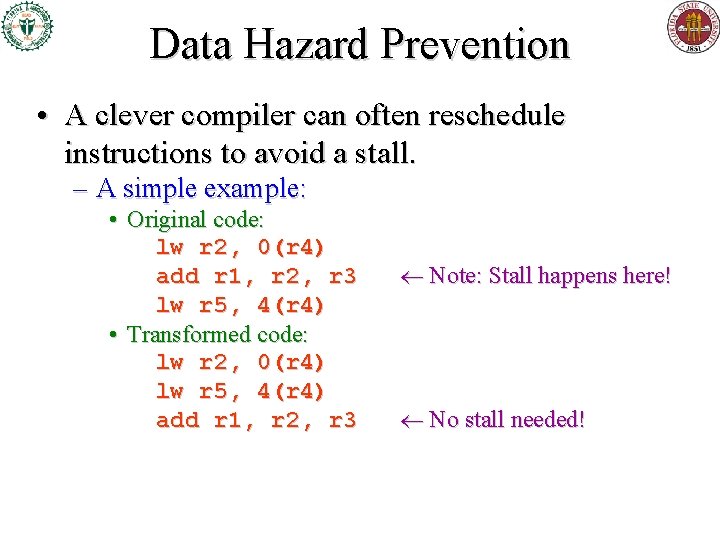

Data Hazard Prevention • A clever compiler can often reschedule instructions to avoid a stall. – A simple example: • Original code: lw r 2, 0(r 4) add r 1, r 2, r 3 lw r 5, 4(r 4) • Transformed code: lw r 2, 0(r 4) lw r 5, 4(r 4) add r 1, r 2, r 3 Note: Stall happens here! No stall needed!

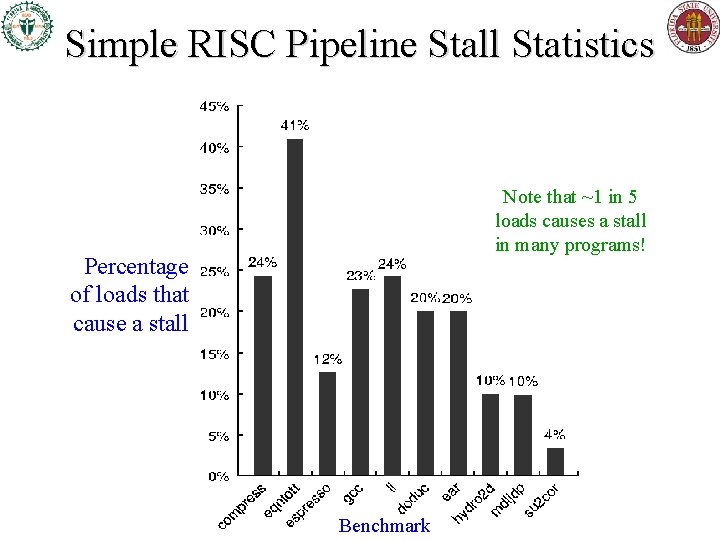

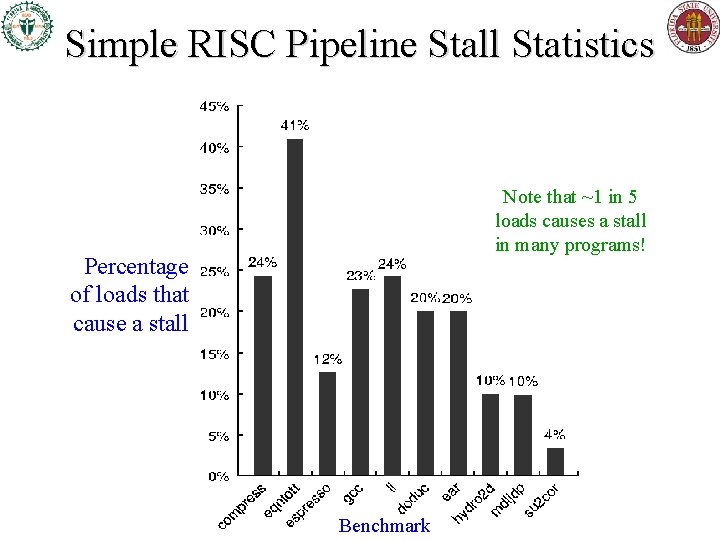

Simple RISC Pipeline Stall Statistics Note that ~1 in 5 loads causes a stall in many programs! Percentage of loads that cause a stall Benchmark

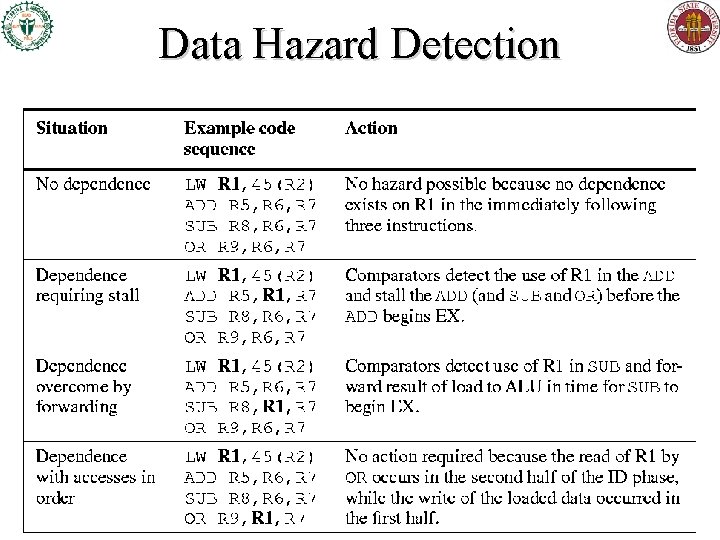

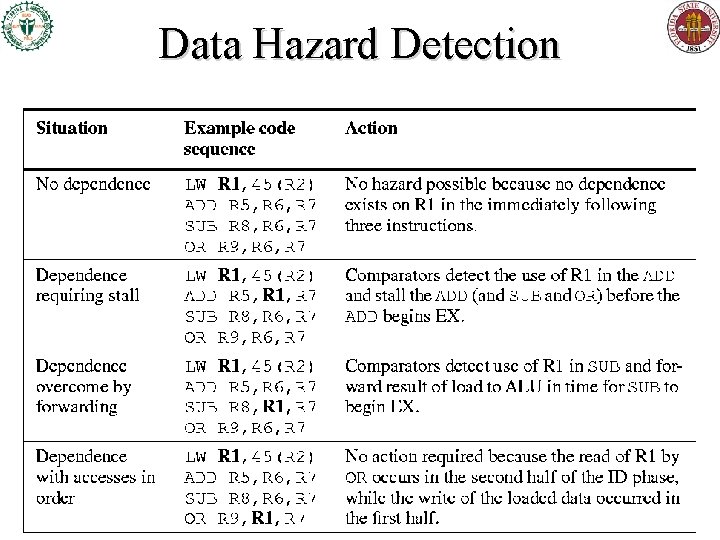

Data Hazard Detection

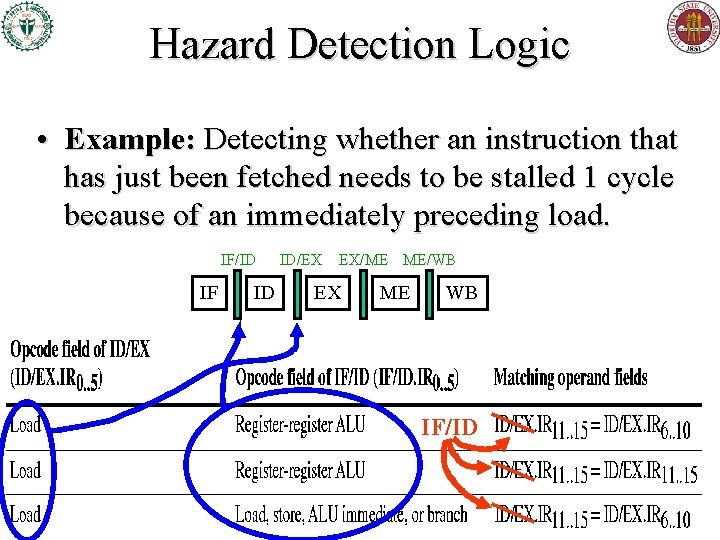

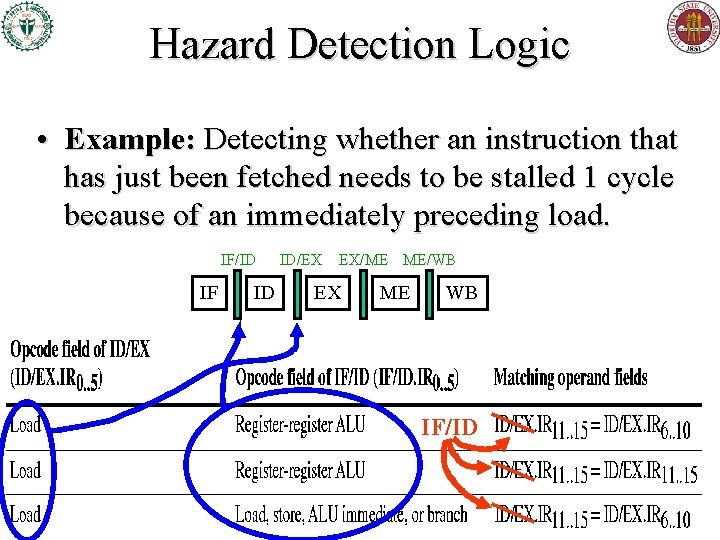

Hazard Detection Logic • Example: Detecting whether an instruction that has just been fetched needs to be stalled 1 cycle because of an immediately preceding load. IF/ID IF ID ID/EX EX/ME ME/WB EX ME WB IF/ID

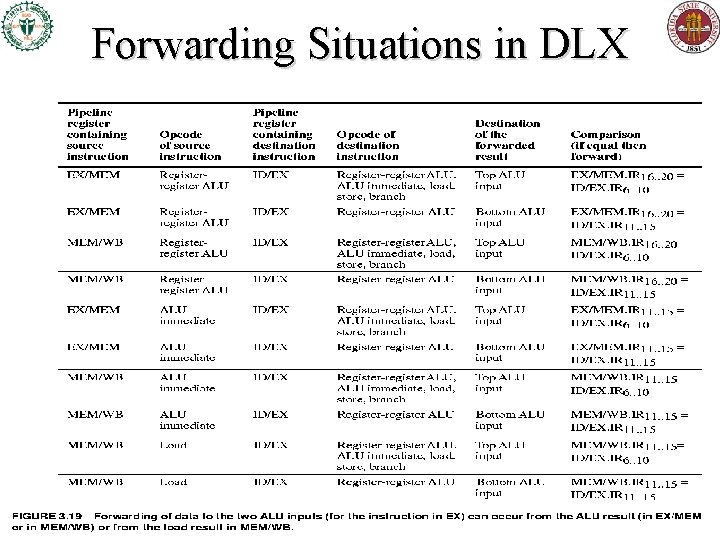

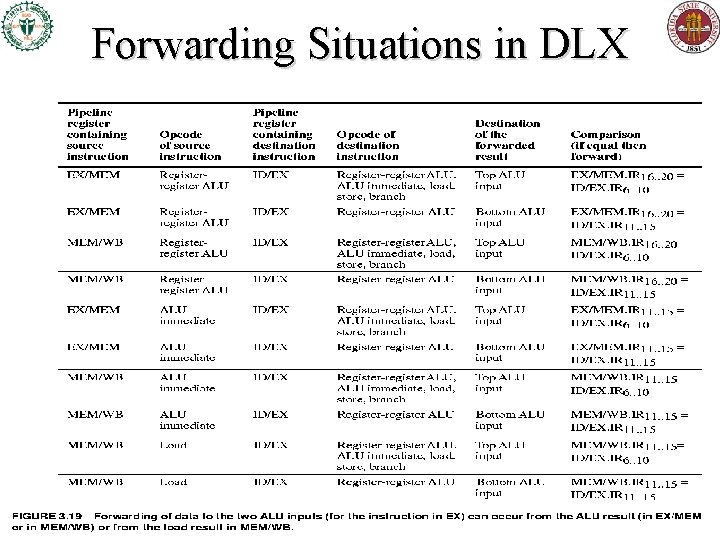

Forwarding Situations in DLX

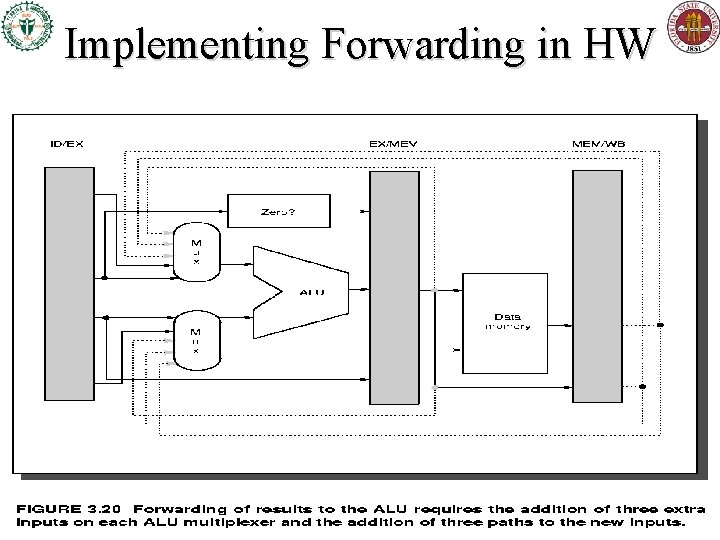

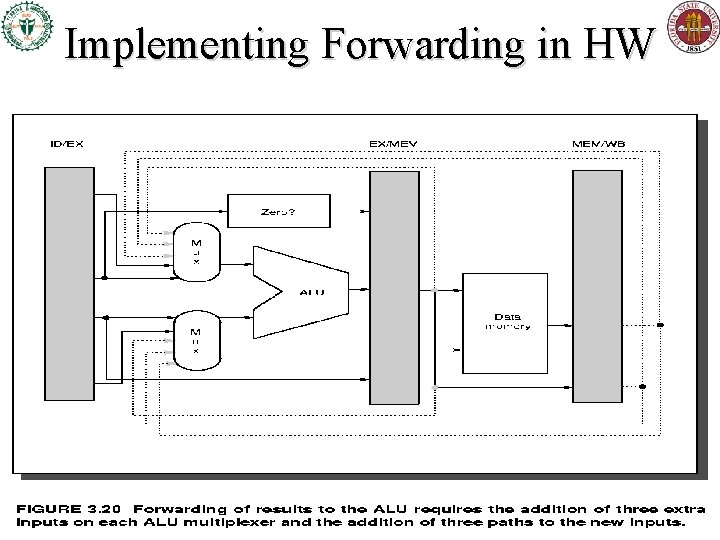

Implementing Forwarding in HW

Control Hazards, Branch Prediction, Delayed Branches H&P 3 rd ed. , §§A. 2 -3 & § 4. 2

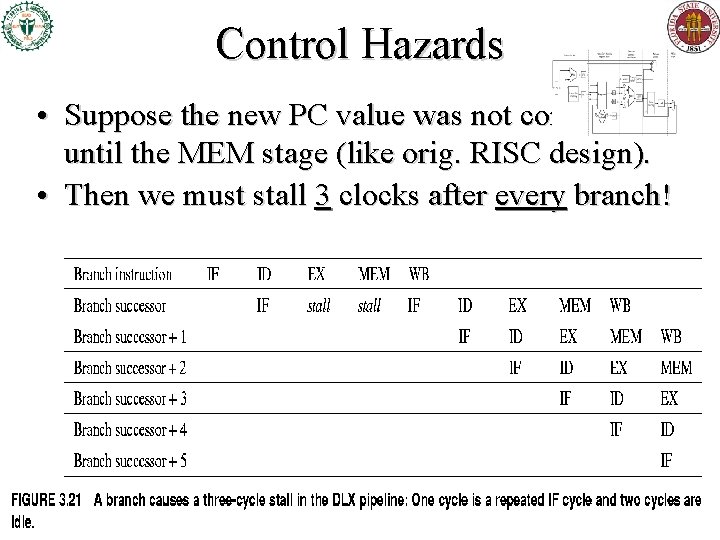

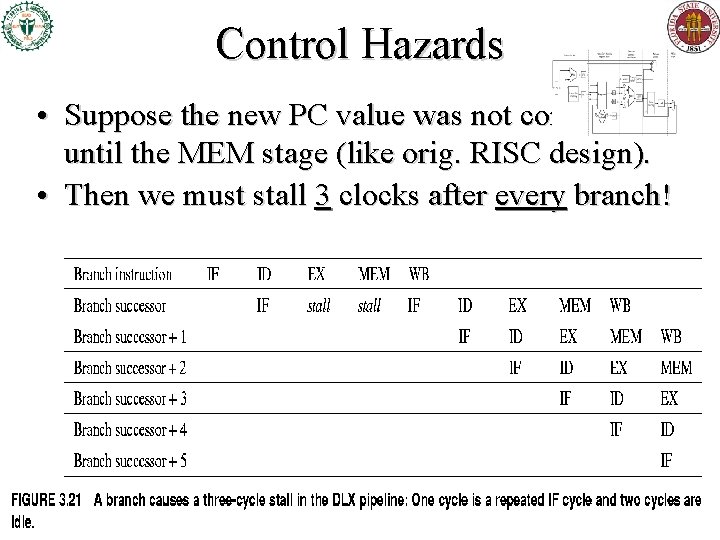

Control Hazards • Suppose the new PC value was not computed until the MEM stage (like orig. RISC design). • Then we must stall 3 clocks after every branch!

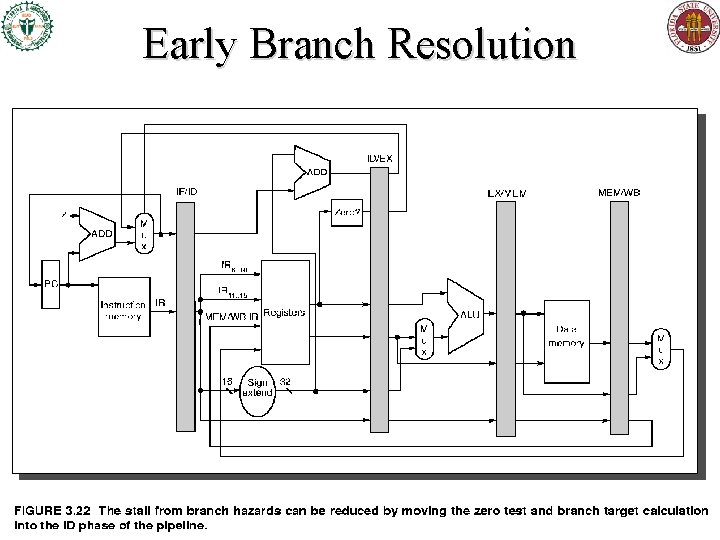

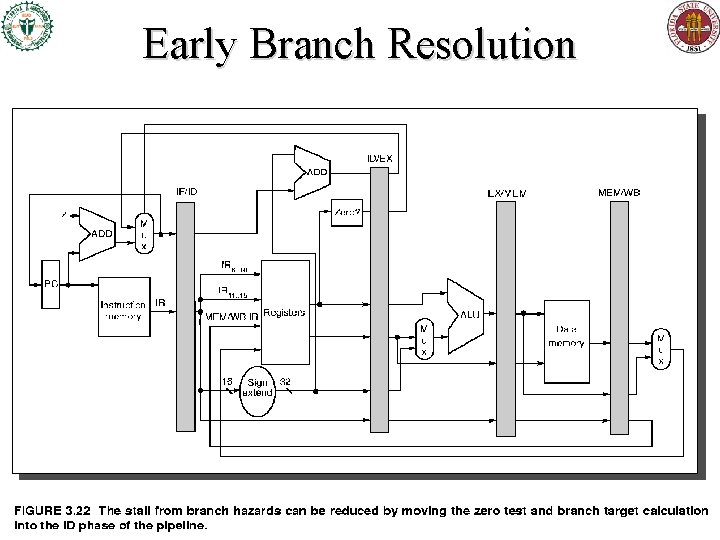

Early Branch Resolution

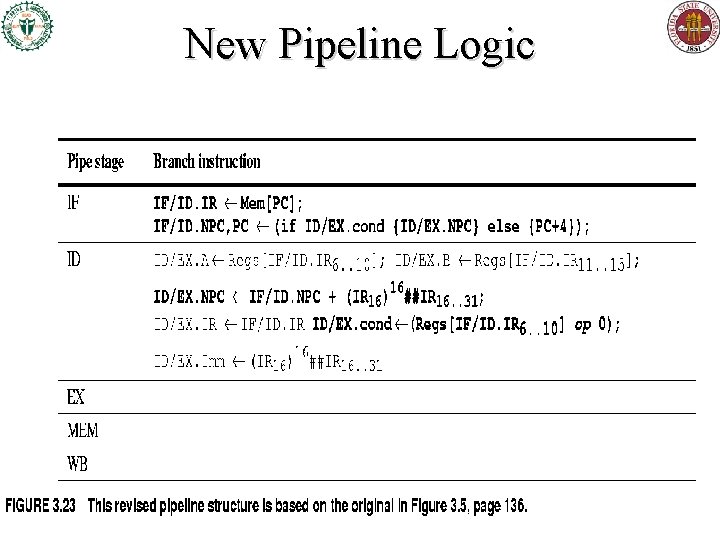

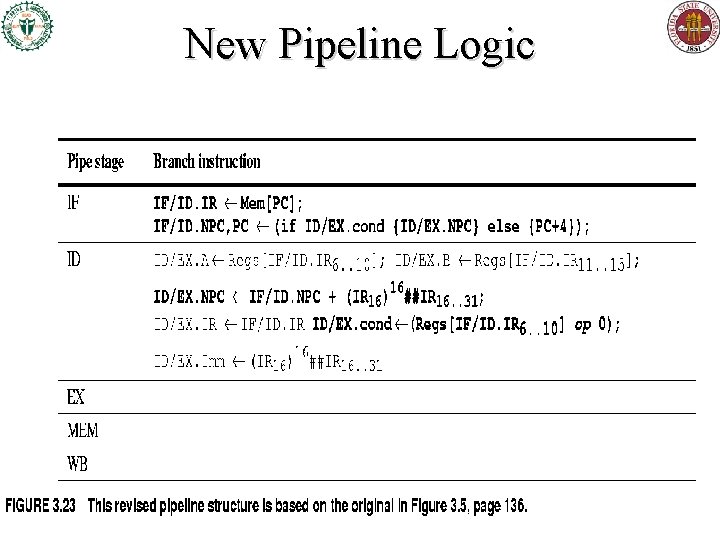

New Pipeline Logic

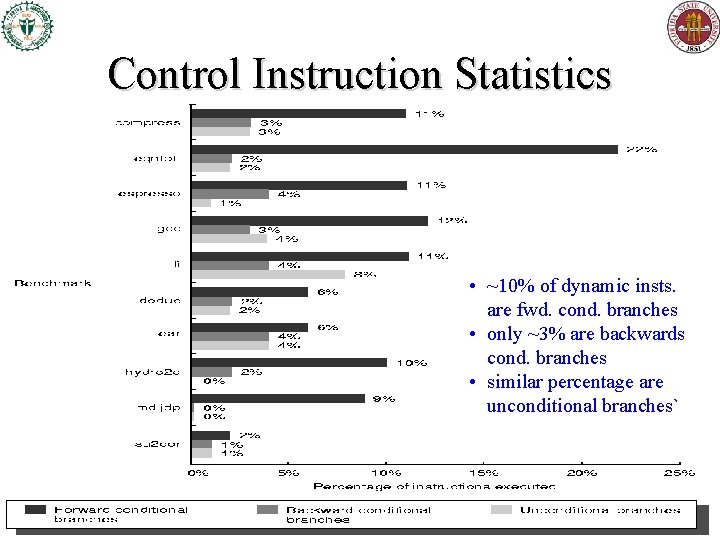

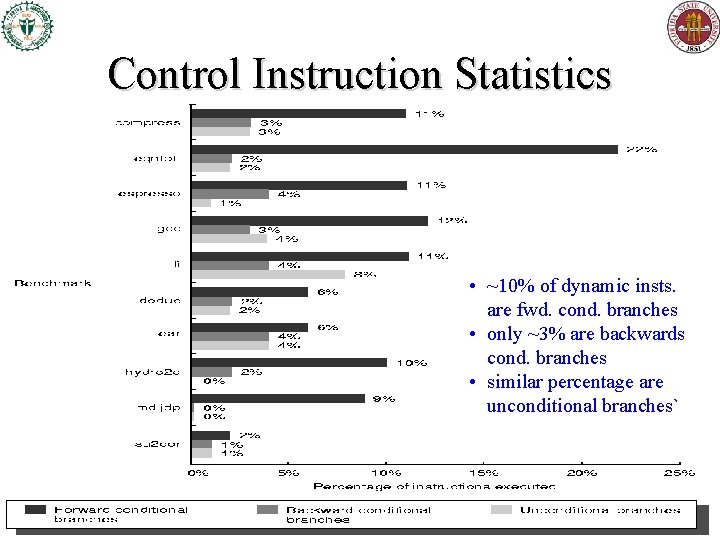

Control Instruction Statistics • ~10% of dynamic insts. are fwd. cond. branches • only ~3% are backwards cond. branches • similar percentage are unconditional branches`

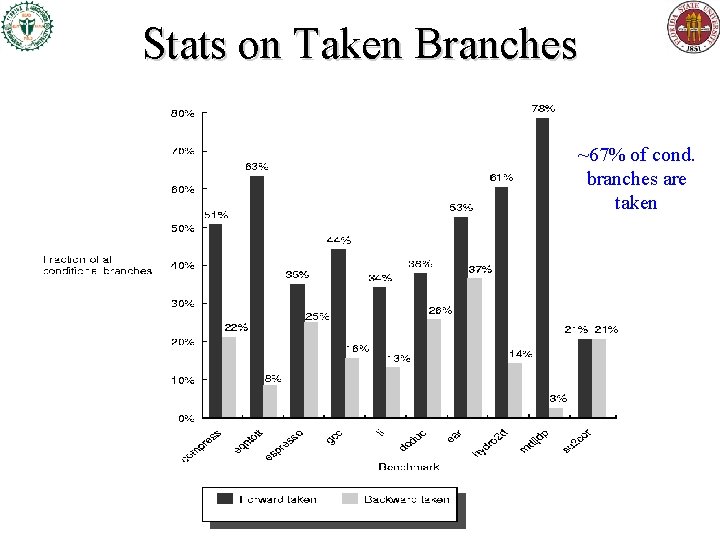

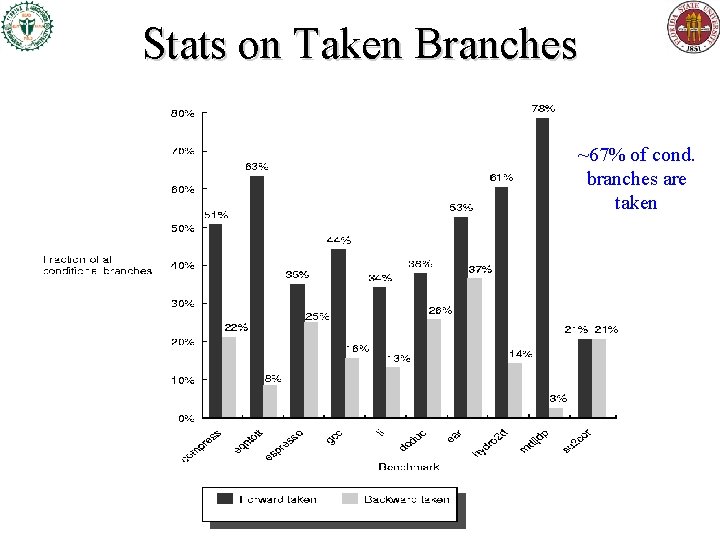

Stats on Taken Branches ~67% of cond. branches are taken

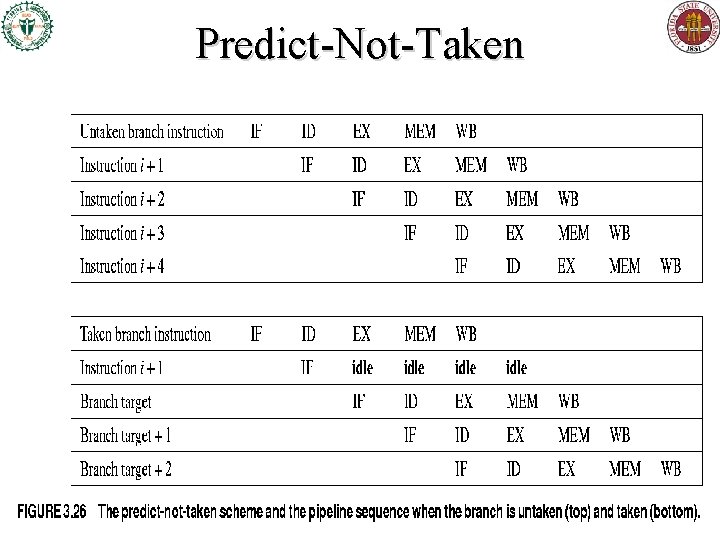

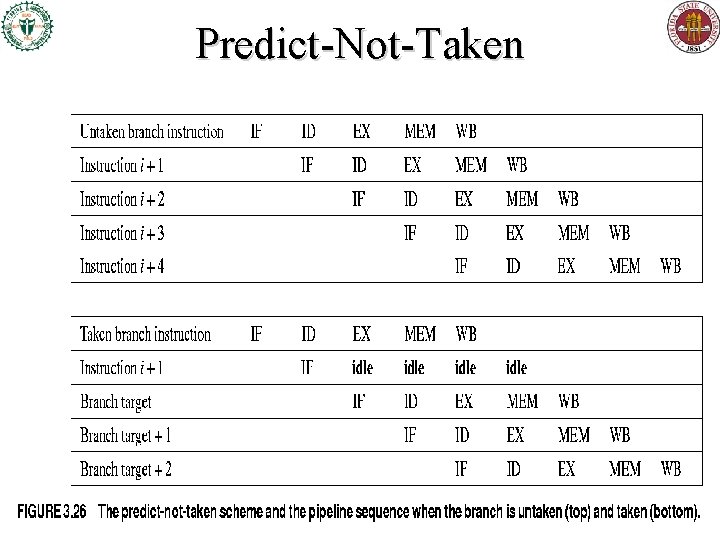

Predict-Not-Taken

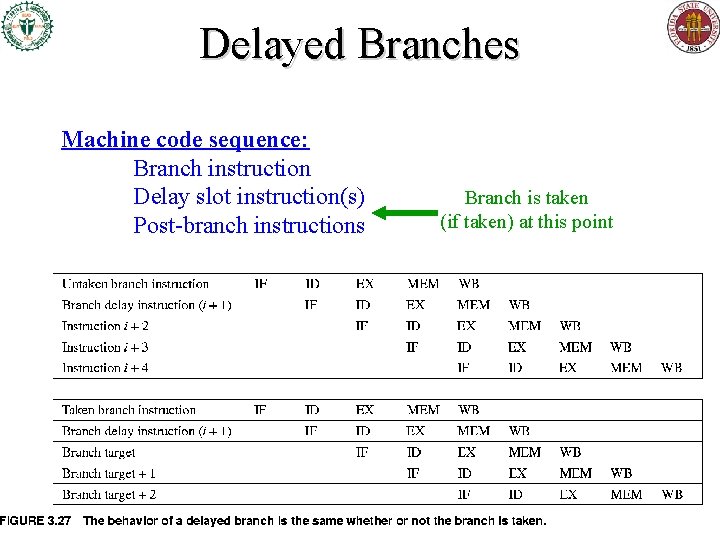

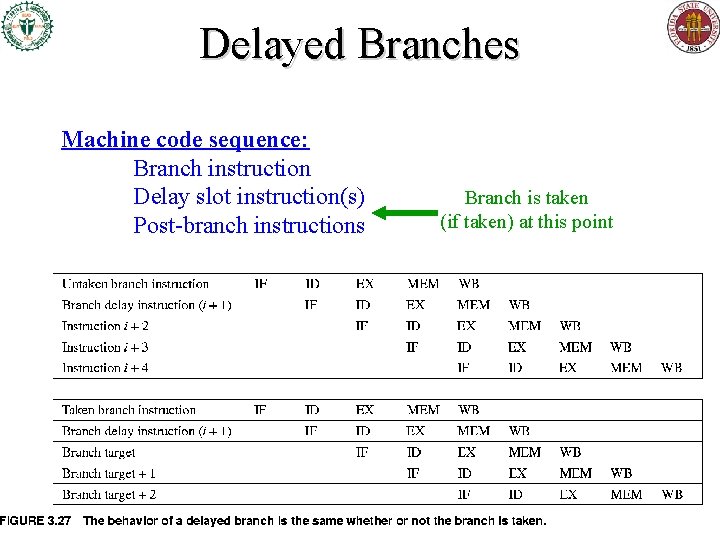

Delayed Branches Machine code sequence: Branch instruction Delay slot instruction(s) Post-branch instructions Branch is taken (if taken) at this point

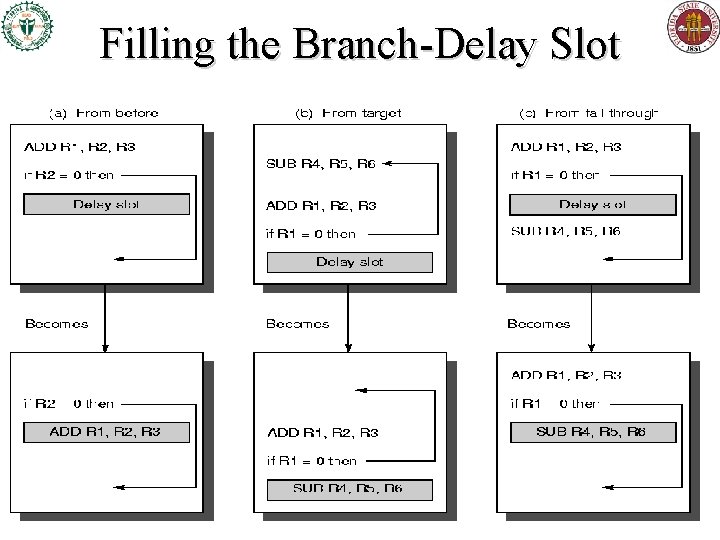

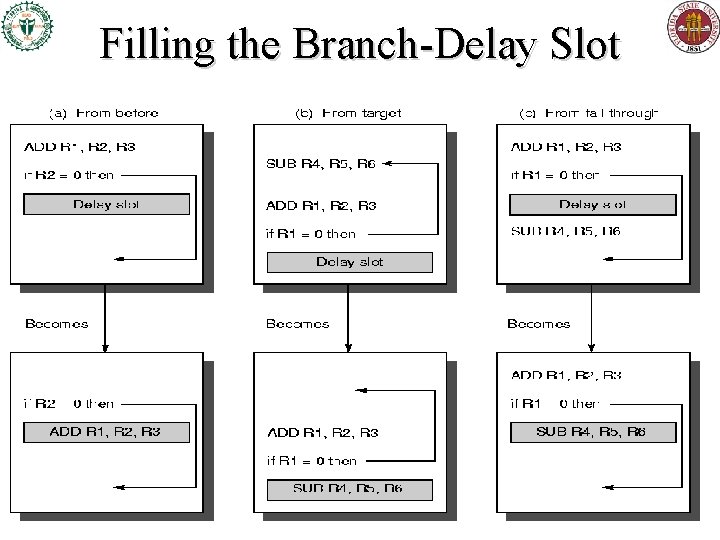

Filling the Branch-Delay Slot

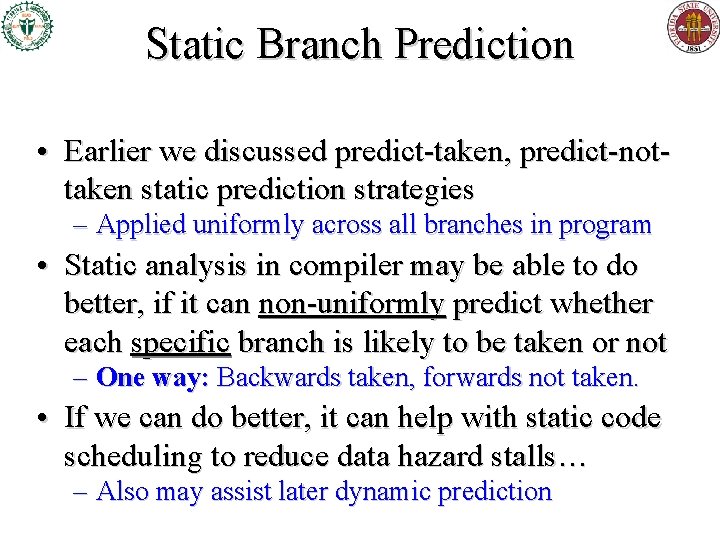

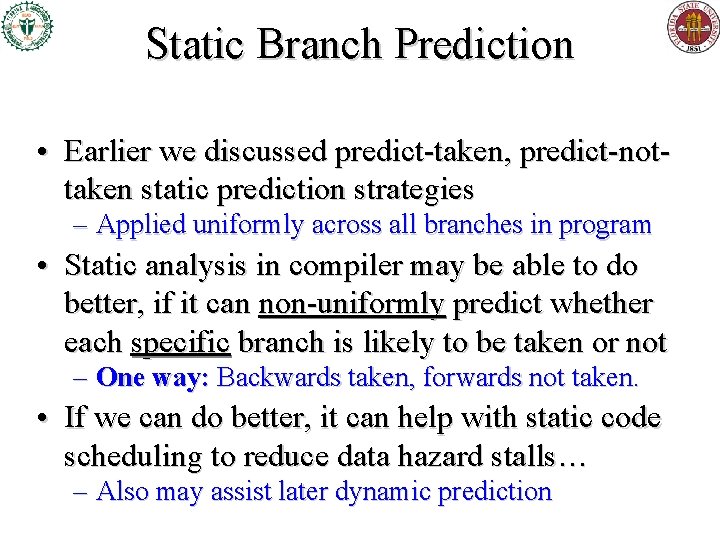

Static Branch Prediction • Earlier we discussed predict-taken, predict-nottaken static prediction strategies – Applied uniformly across all branches in program • Static analysis in compiler may be able to do better, if it can non-uniformly predict whether each specific branch is likely to be taken or not – One way: Backwards taken, forwards not taken. • If we can do better, it can help with static code scheduling to reduce data hazard stalls… – Also may assist later dynamic prediction

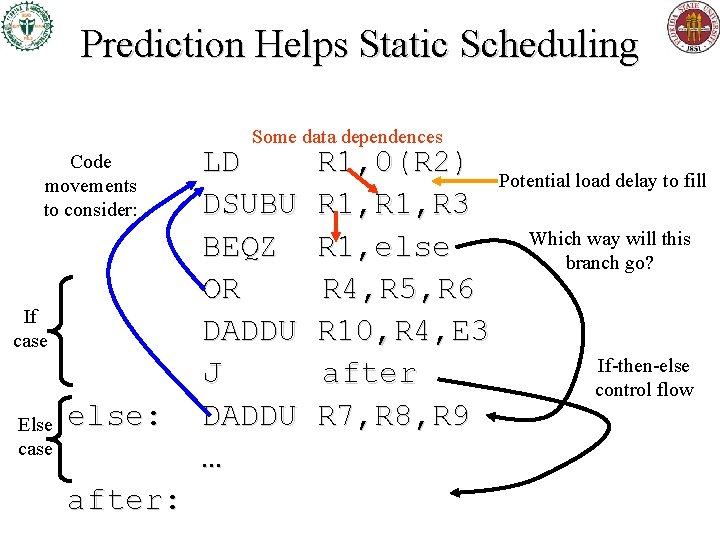

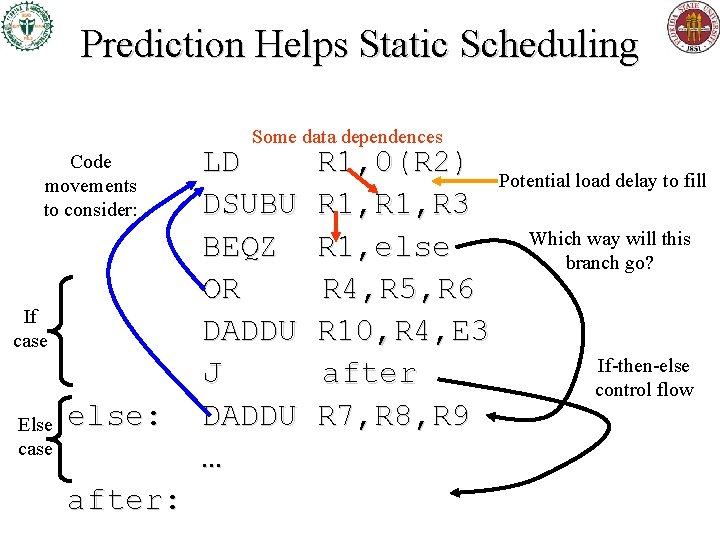

Prediction Helps Static Scheduling Some data dependences Code movements to consider: If case Else case else: after: LD DSUBU BEQZ OR DADDU J DADDU … R 1, 0(R 2) Potential load delay to fill R 1, R 3 Which way will this R 1, else branch go? R 4, R 5, R 6 R 10, R 4, E 3 If-then-else after control flow R 7, R 8, R 9

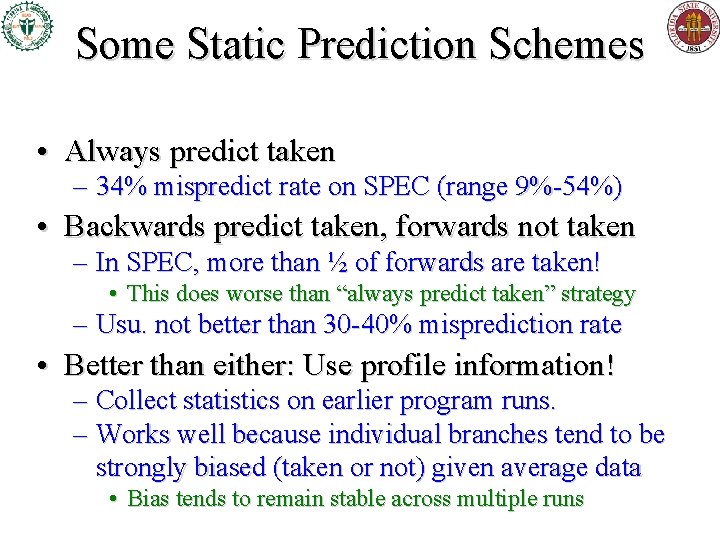

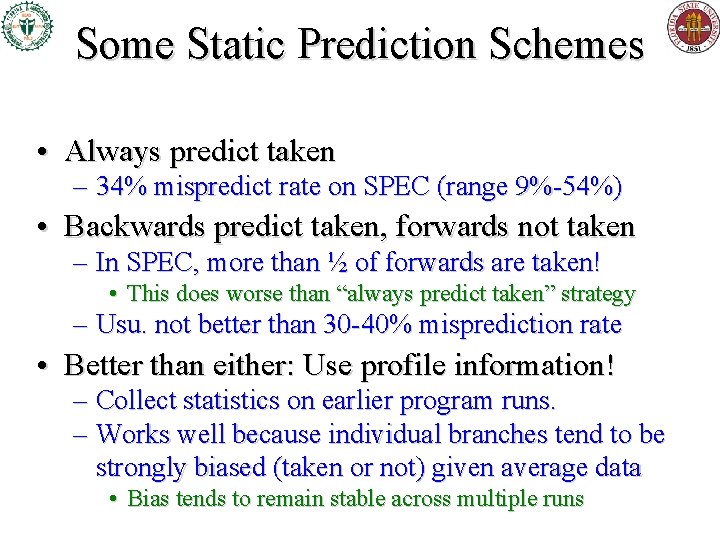

Some Static Prediction Schemes • Always predict taken – 34% mispredict rate on SPEC (range 9%-54%) • Backwards predict taken, forwards not taken – In SPEC, more than ½ of forwards are taken! • This does worse than “always predict taken” strategy – Usu. not better than 30 -40% misprediction rate • Better than either: Use profile information! – Collect statistics on earlier program runs. – Works well because individual branches tend to be strongly biased (taken or not) given average data • Bias tends to remain stable across multiple runs

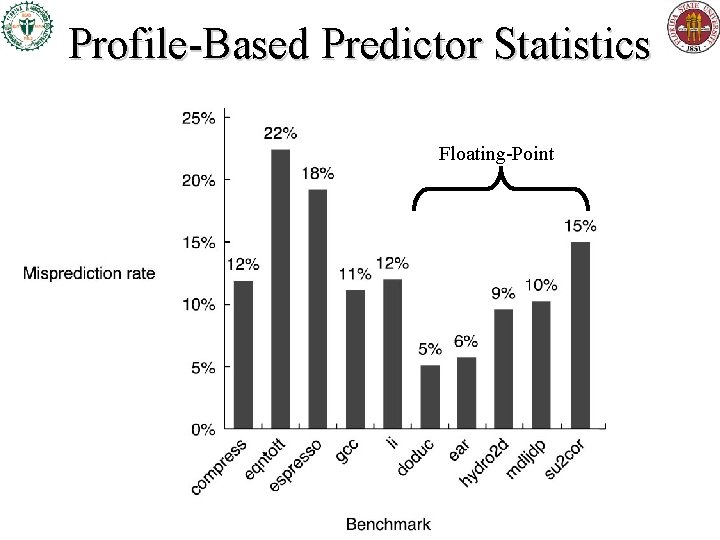

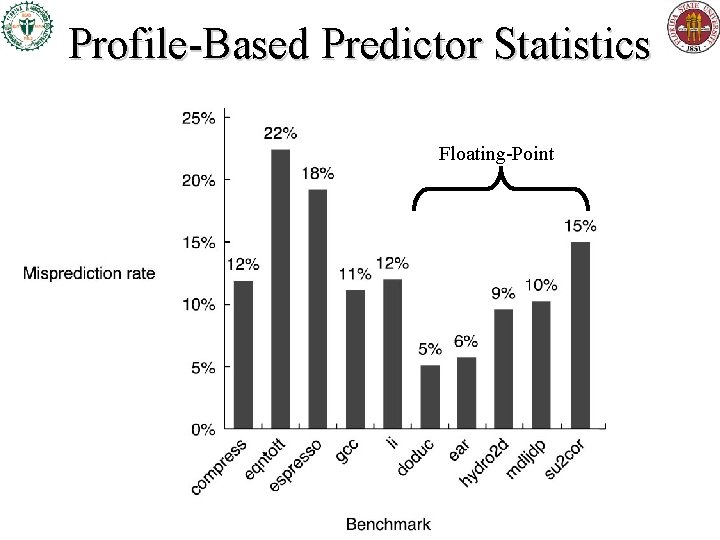

Profile-Based Predictor Statistics Floating-Point

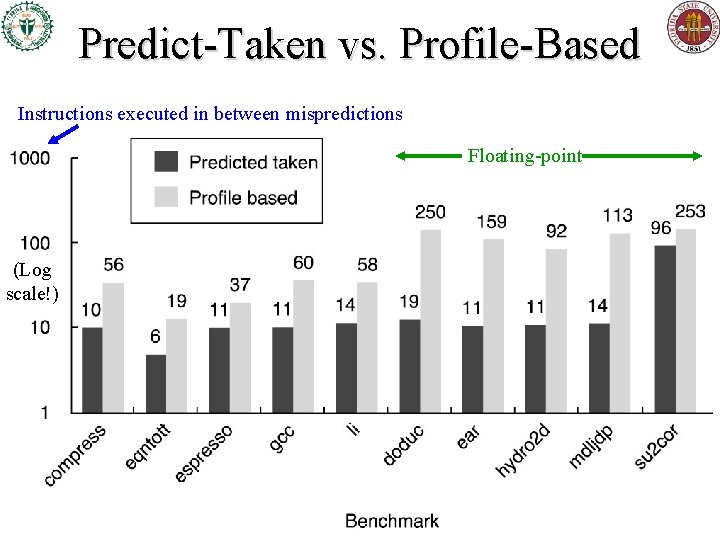

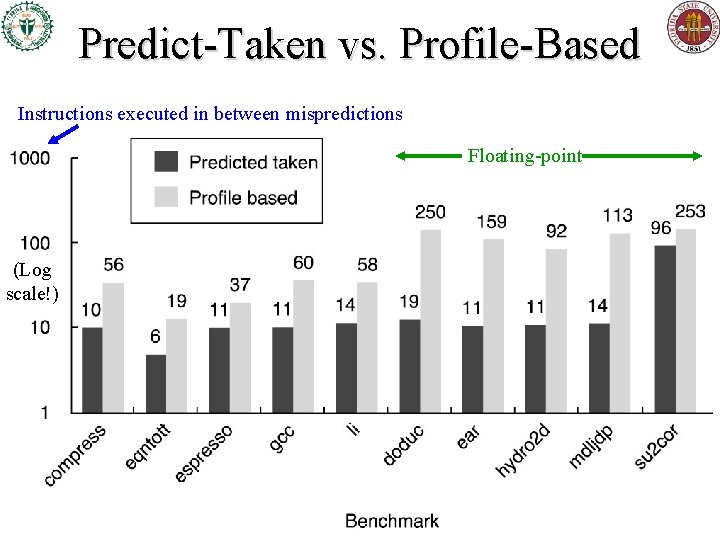

Predict-Taken vs. Profile-Based Instructions executed in between mispredictions Floating-point (Log scale!)