COMPLEXITY ISSUES IN READING IMPLICATIONS FOR EARLY READING

- Slides: 33

COMPLEXITY ISSUES IN READING: IMPLICATIONS FOR EARLY READING IN AFRICAN LANGUAGES Re. Sep, Stellenbosch Lilli Pretorius 21 February 2020

OUTLINE SONA 2019 and implications Complexity issues What can we expect in complex systems? Are there some main operating strategies or mechanisms? Complexity trade-offs in orthographic systems Relationships between components Features of agglutinating African languages Early reading performance in African languages Implications for theory, policy and pedagogy

PRESIDENT RAMAPHOSA’s STATE of the NATION ADDRESS 20 JUNE 2019 2012 National Development Plan - aim is to defeat poverty, unemployment and inequality by 2030 • Not enough progress in meeting these NDP goals • 7 -priority focus • Schools will have better outcomes and every 10 -year-old will be able to read for meaning Early reading is the basic foundation that determines a child’s educational progress, through school, through higher education and into the workplace. All other interventions – from the work being done to improve the quality of basic education to the provision of free higher education for the poor, from our investment in Technical and Vocational Education Training colleges to the expansion of workplace learning – will not produce the results we need unless we first ensure that children can read.

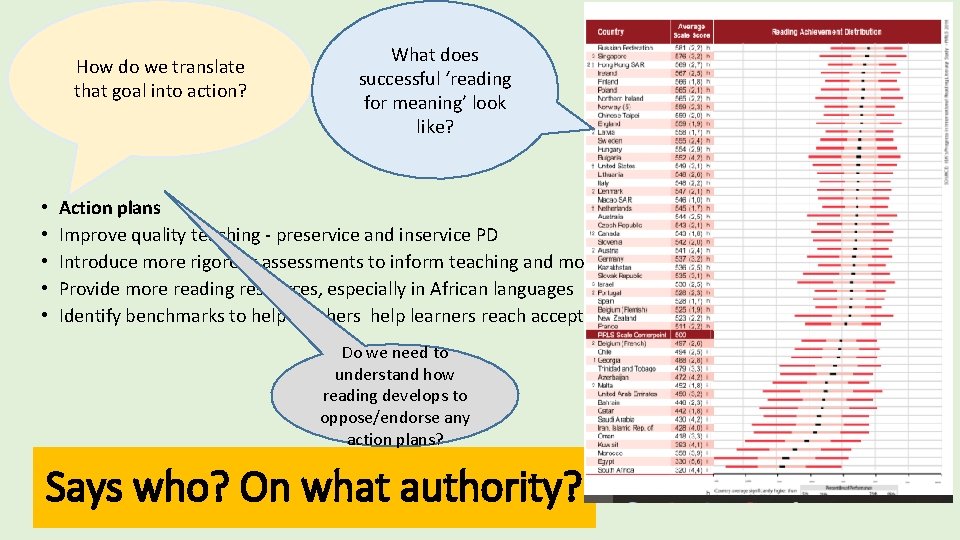

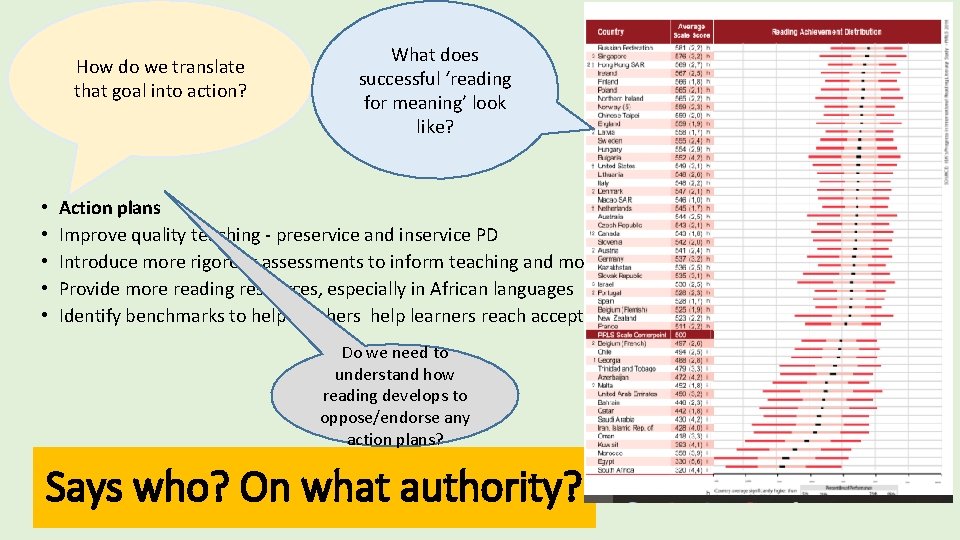

How do we translate that goal into action? • • • What does successful ‘reading for meaning’ look like? Action plans Improve quality teaching - preservice and inservice PD Introduce more rigorous assessments to inform teaching and monitor reading progress Provide more reading resources, especially in African languages Identify benchmarks to help teachers help learners reach acceptable levels of reading Do we need to understand how reading develops to oppose/endorse any action plans? Says who? On what authority?

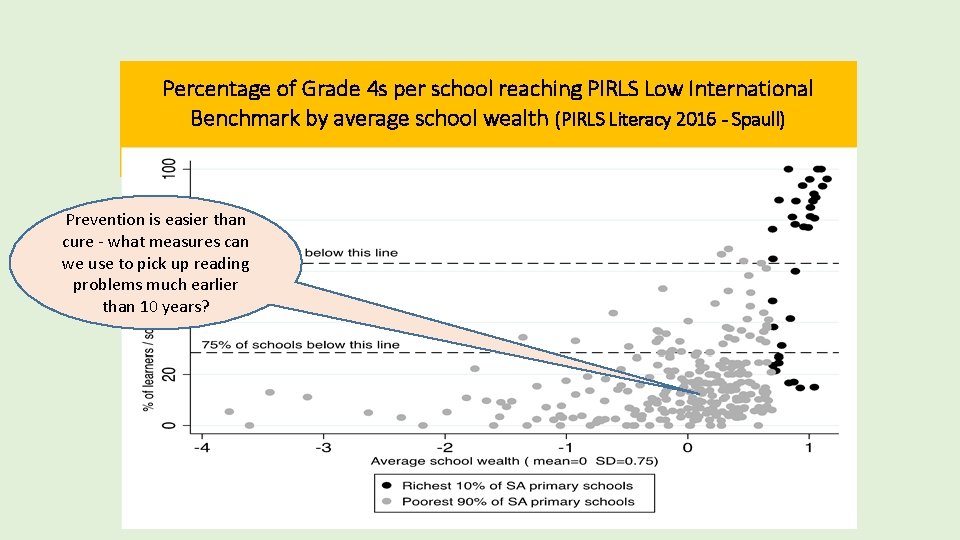

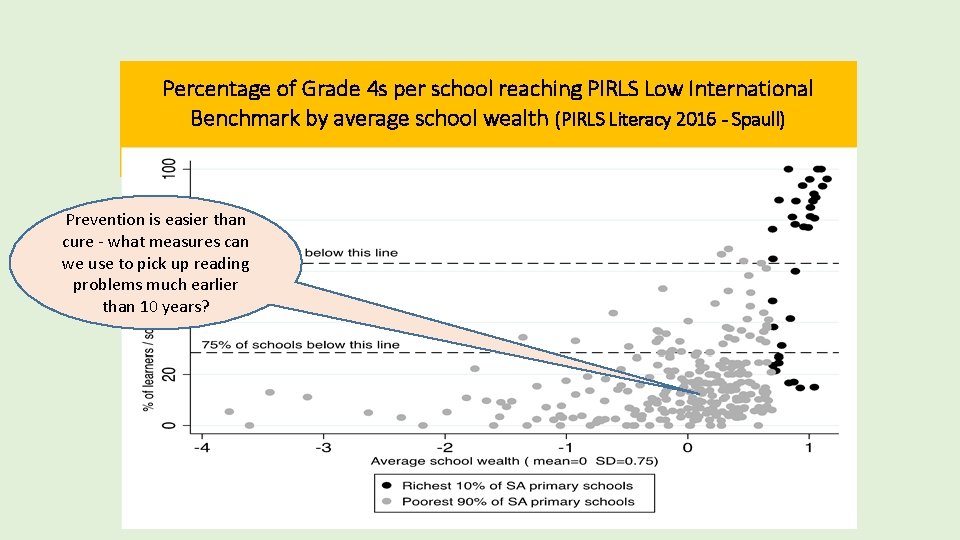

Percentage of Grade 4 s per school reaching PIRLS Low International Benchmark by average school wealth (PIRLS Literacy 2016 - Spaull) Prevention is easier than cure - what measures can we use to pick up reading problems much earlier than 10 years?

TRYING TO UNDERSTAND THE BIGGER PICTURE: LITERACY DEVELOPMENT, ASSESSMENT AND BENCHMARKS Resistance to scientific approaches to solving reading problems (especially if economists are involved…) “Scientists tell us that the fastest animal on earth, with a top speed of 120 feet per second, is a cow dropped out of a helicopter” (Dave Barry) Reactions to assessments and benchmarking • “What is happening in schools today is Readicide; the intentional killing of the love of reading. ” • “It emphasises children’s deficits, not their strengths” • “Teachers are drilling kids to pass assessments which have no correlation with reading comprehension. ” • “Enough testing. Leave us alone and let us teach. We know more about children and how to teach reading than those who have never taught a child to read. ”

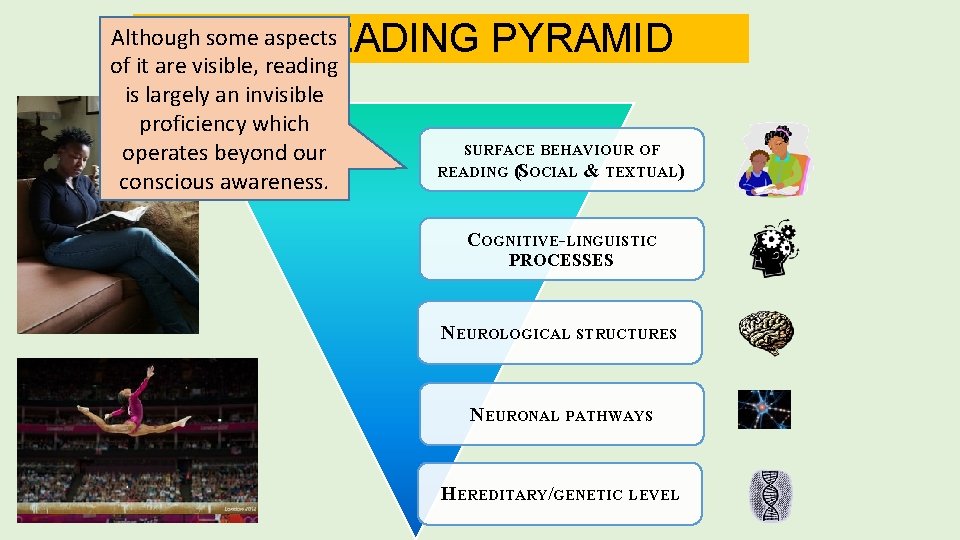

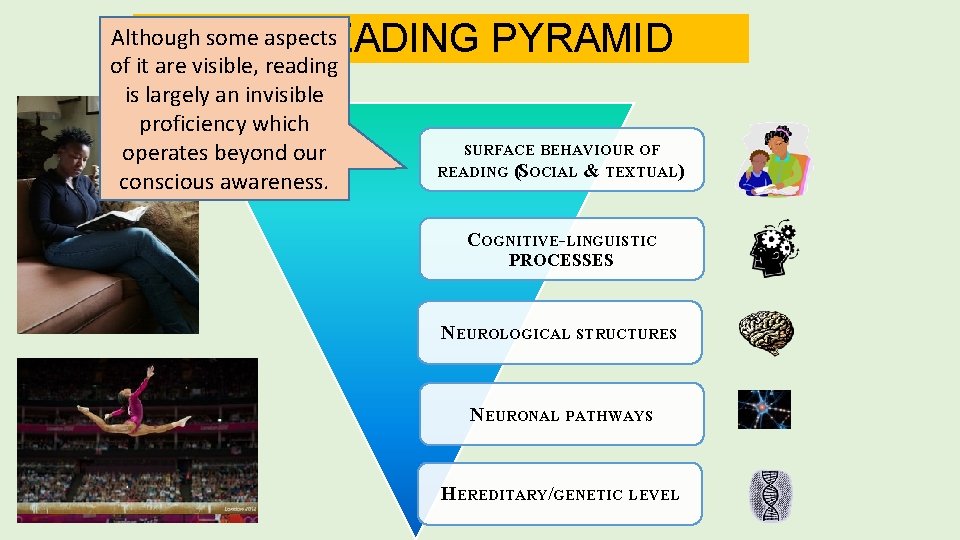

THE READING PYRAMID Although some aspects of it are visible, reading is largely an invisible proficiency which operates beyond our conscious awareness. SURFACE BEHAVIOUR OF READING (SOCIAL & TEXTUAL) COGNITIVE-LINGUISTIC PROCESSES NEUROLOGICAL STRUCTURES NEURONAL PATHWAYS HEREDITARY/GENETIC LEVEL

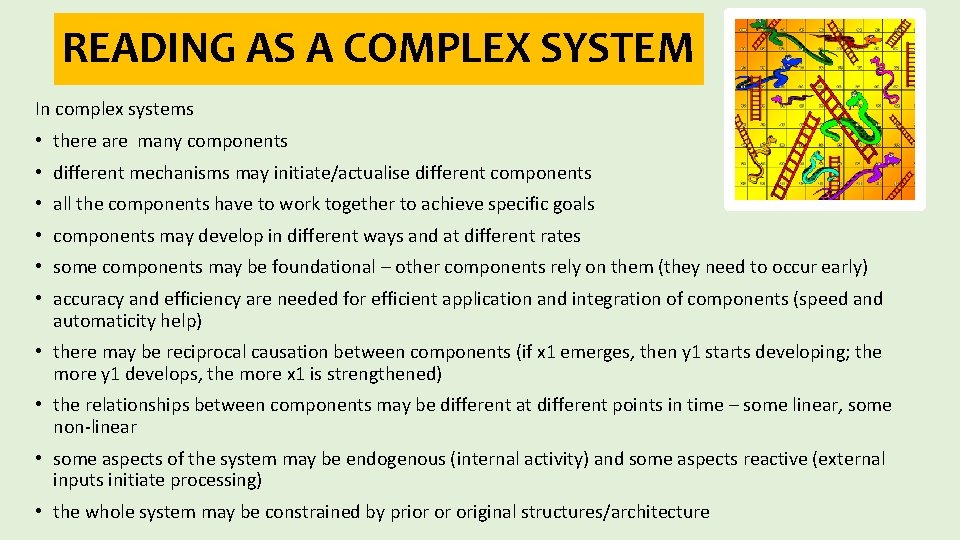

READING AS A COMPLEX SYSTEM In complex systems • there are many components • different mechanisms may initiate/actualise different components • all the components have to work together to achieve specific goals • components may develop in different ways and at different rates • some components may be foundational – other components rely on them (they need to occur early) • accuracy and efficiency are needed for efficient application and integration of components (speed and automaticity help) • there may be reciprocal causation between components (if x 1 emerges, then y 1 starts developing; the more y 1 develops, the more x 1 is strengthened) • the relationships between components may be different at different points in time – some linear, some non-linear • some aspects of the system may be endogenous (internal activity) and some aspects reactive (external inputs initiate processing) • the whole system may be constrained by prior or original structures/architecture

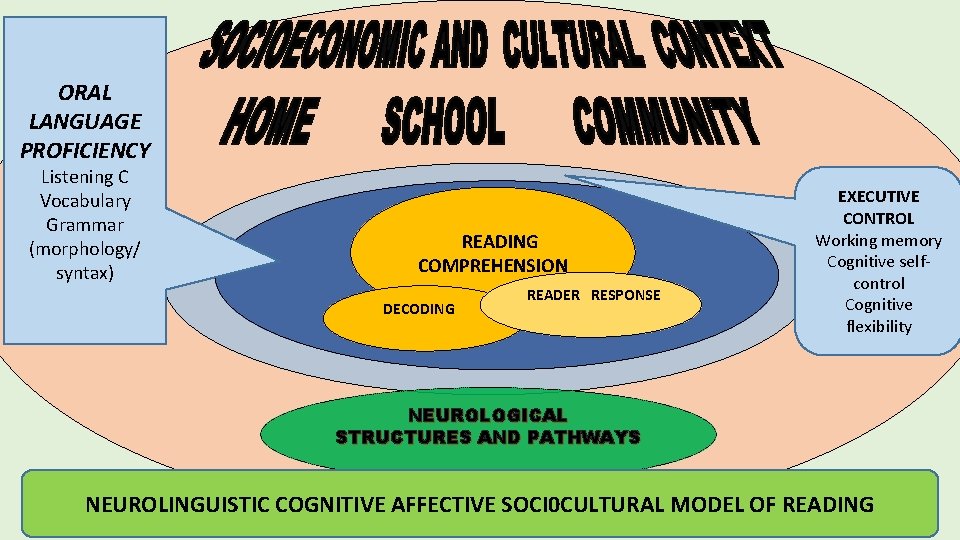

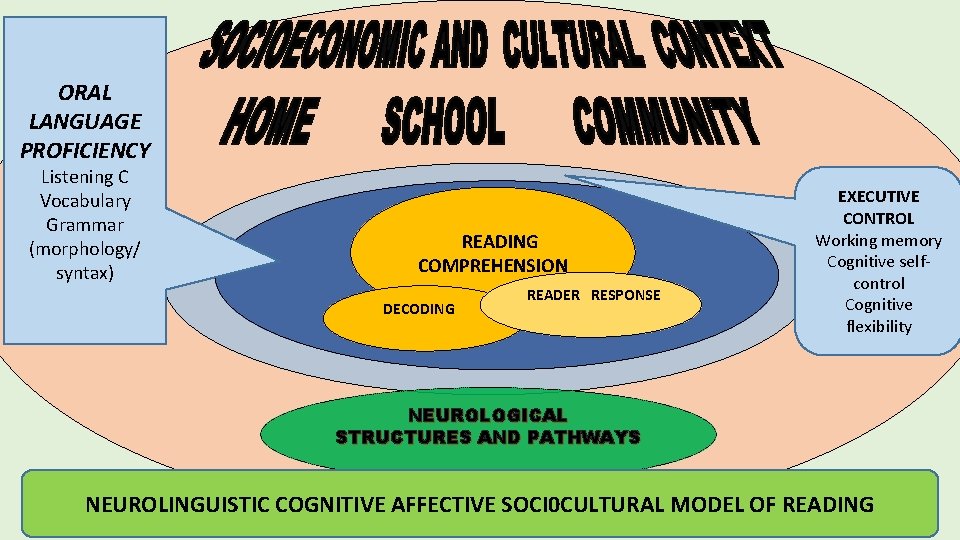

ORAL LANGUAGE PROFICIENCY Listening C Vocabulary Grammar (morphology/ syntax) Cognitive-linguistic READING COMPREHENSION DECODING READER RESPONSE EXECUTIVE CONTROL Working memory Cognitive selfcontrol Cognitive flexibility NEUROLOGICAL STRUCTURES AND PATHWAYS NEUROLINGUISTIC COGNITIVE AFFECTIVE SOCI 0 CULTURAL MODEL OF READING

SUBCOMPONENTS OF DECODING LETTER-SOUND KNOWLEDGE/ WORD RECOGNITION/ WORD WORK PHONICS PHONOLOGICAL & PHONEMIC AWARENESS DECODING ORAL READING FLUENCY (ORF)

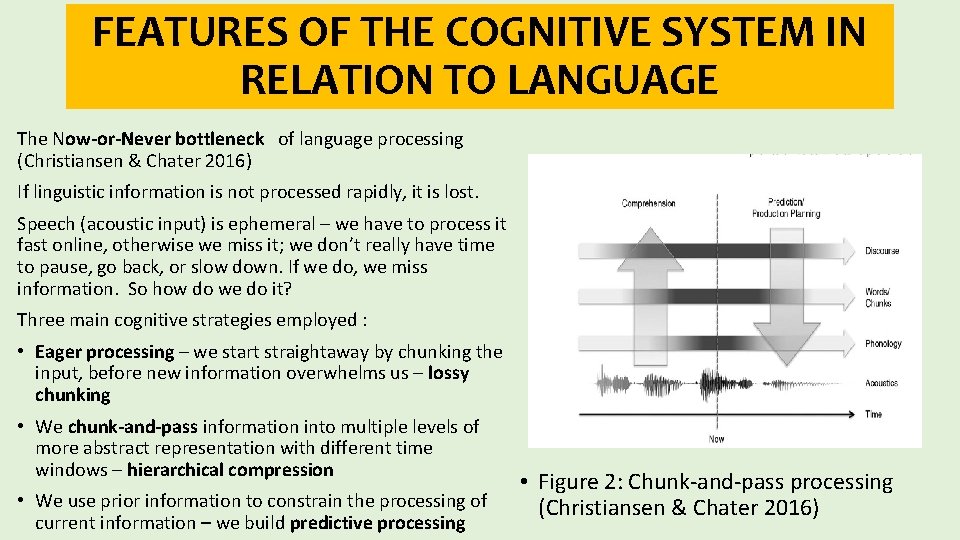

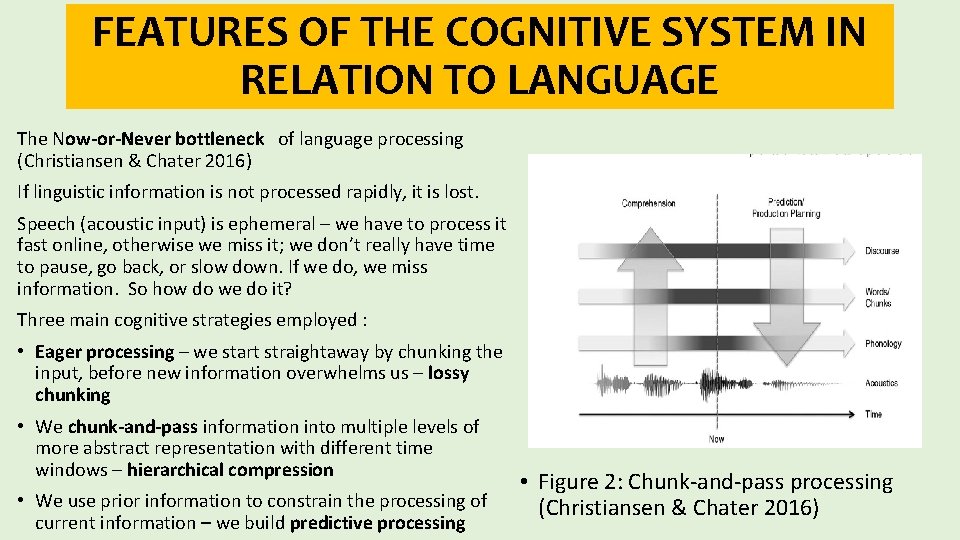

FEATURES OF THE COGNITIVE SYSTEM IN RELATION TO LANGUAGE The Now-or-Never bottleneck of language processing (Christiansen & Chater 2016) If linguistic information is not processed rapidly, it is lost. Speech (acoustic input) is ephemeral – we have to process it fast online, otherwise we miss it; we don’t really have time to pause, go back, or slow down. If we do, we miss information. So how do we do it? Three main cognitive strategies employed : • Eager processing – we start straightaway by chunking the input, before new information overwhelms us – lossy chunking • We chunk-and-pass information into multiple levels of more abstract representation with different time windows – hierarchical compression • We use prior information to constrain the processing of current information – we build predictive processing • Figure 2: Chunk-and-pass processing (Christiansen & Chater 2016)

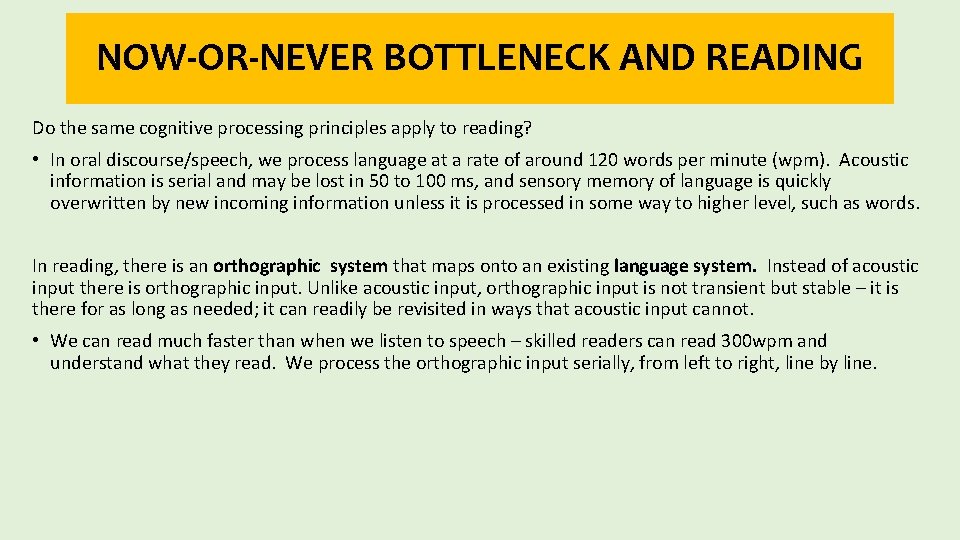

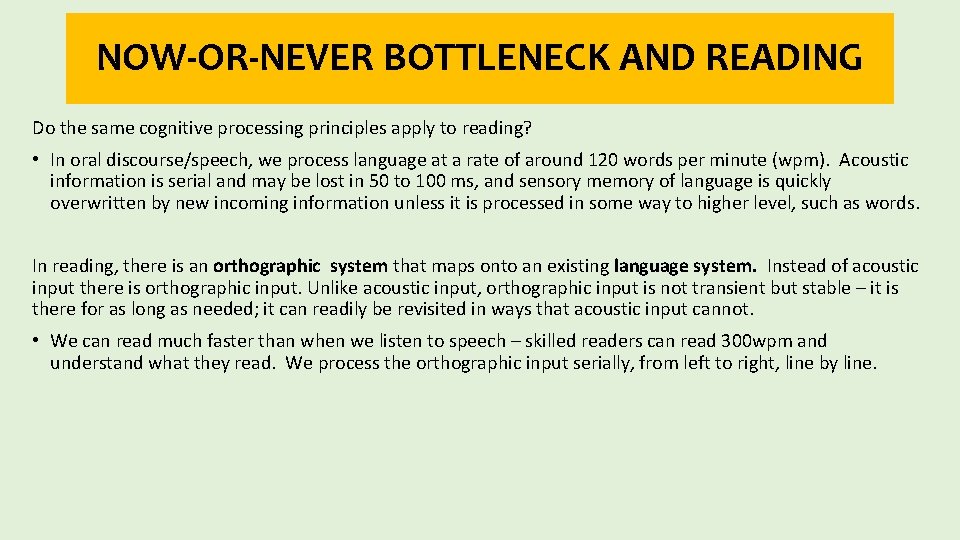

NOW-OR-NEVER BOTTLENECK AND READING Do the same cognitive processing principles apply to reading? • In oral discourse/speech, we process language at a rate of around 120 words per minute (wpm). Acoustic information is serial and may be lost in 50 to 100 ms, and sensory memory of language is quickly overwritten by new incoming information unless it is processed in some way to higher level, such as words. In reading, there is an orthographic system that maps onto an existing language system. Instead of acoustic input there is orthographic input. Unlike acoustic input, orthographic input is not transient but stable – it is there for as long as needed; it can readily be revisited in ways that acoustic input cannot. • We can read much faster than when we listen to speech – skilled readers can read 300 wpm and understand what they read. We process the orthographic input serially, from left to right, line by line.

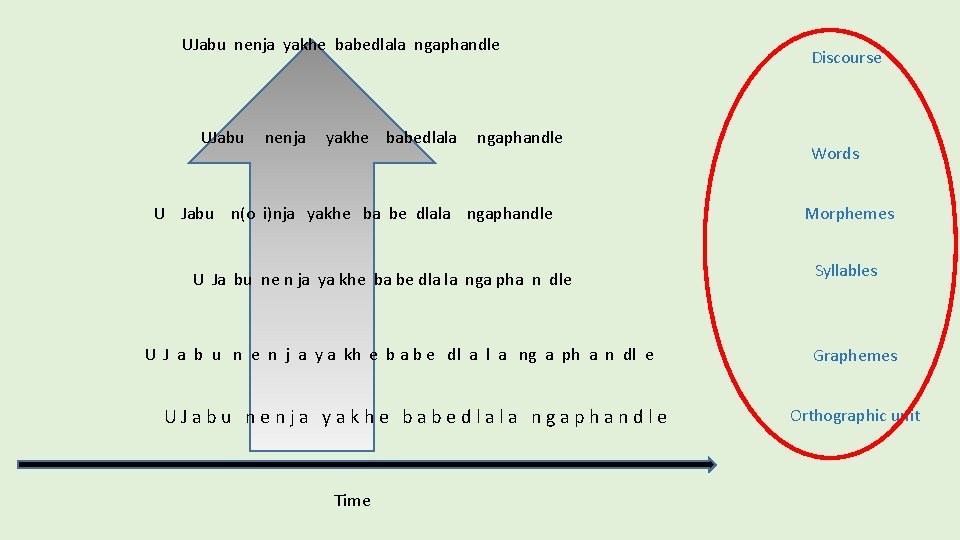

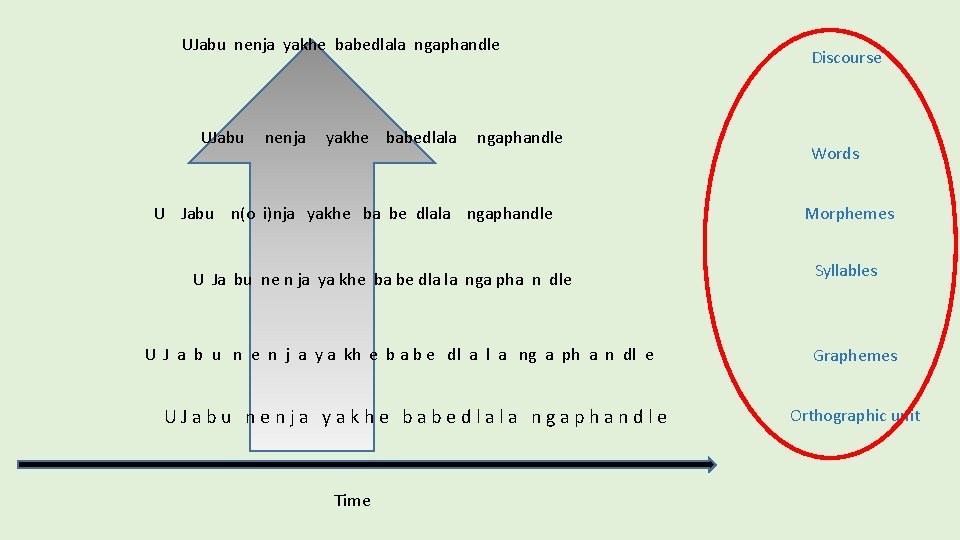

UJabu nenja yakhe babedlala ngaphandle UJabu nenja yakhe babedlala ngaphandle U Jabu n(o i)nja yakhe ba be dlala ngaphandle U Ja bu ne n ja ya khe ba be dla la nga pha n dle U J a b u n e n j a y a kh e b a b e dl a ng a ph a n dl e U J a b u n e n j a y a k h e b a b e d l a n g a p h a n d l e Time Discourse Words Morphemes Syllables Graphemes Orthographic unit

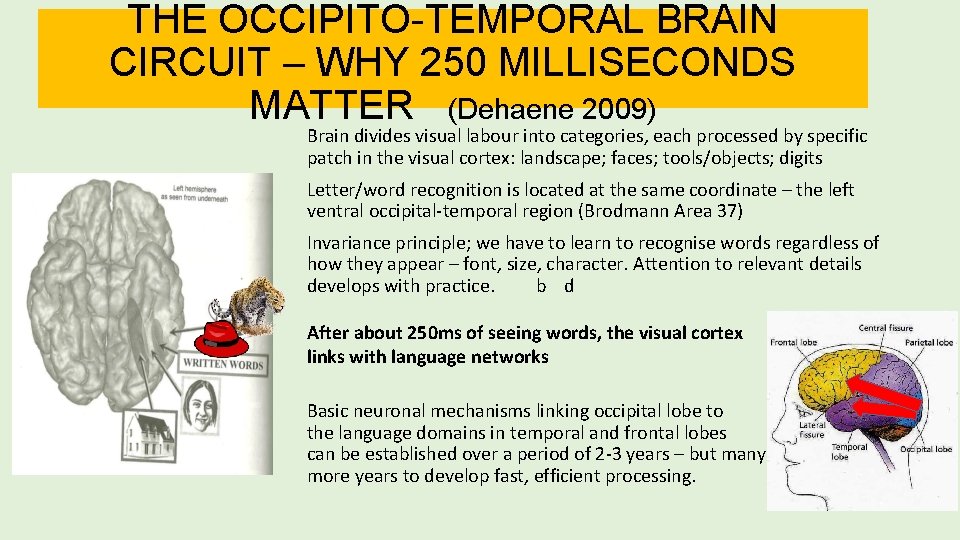

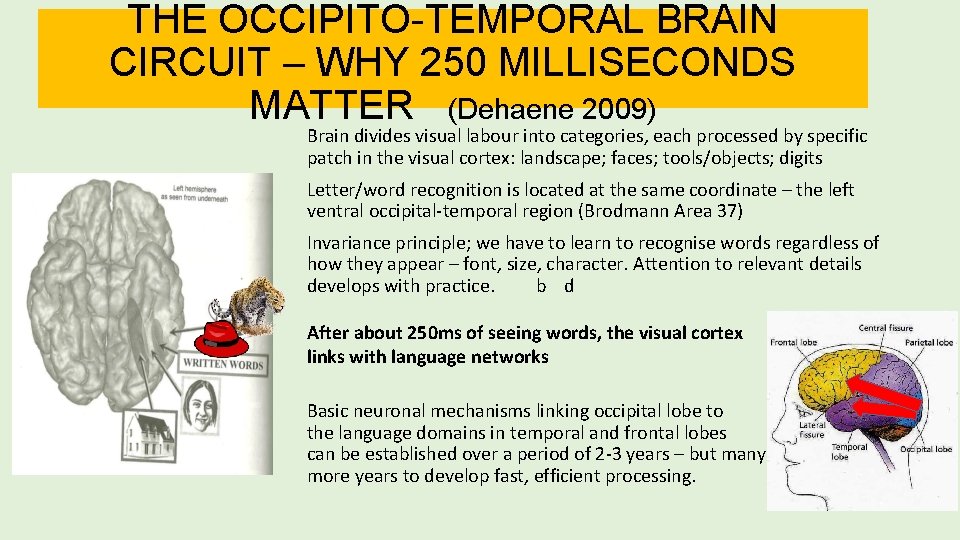

THE OCCIPITO-TEMPORAL BRAIN CIRCUIT – WHY 250 MILLISECONDS MATTER (Dehaene 2009) Brain divides visual labour into categories, each processed by specific patch in the visual cortex: landscape; faces; tools/objects; digits Letter/word recognition is located at the same coordinate – the left ventral occipital-temporal region (Brodmann Area 37) Invariance principle; we have to learn to recognise words regardless of how they appear – font, size, character. Attention to relevant details develops with practice. b d After about 250 ms of seeing words, the visual cortex links with language networks Basic neuronal mechanisms linking occipital lobe to the language domains in temporal and frontal lobes can be established over a period of 2 -3 years – but many more years to develop fast, efficient processing.

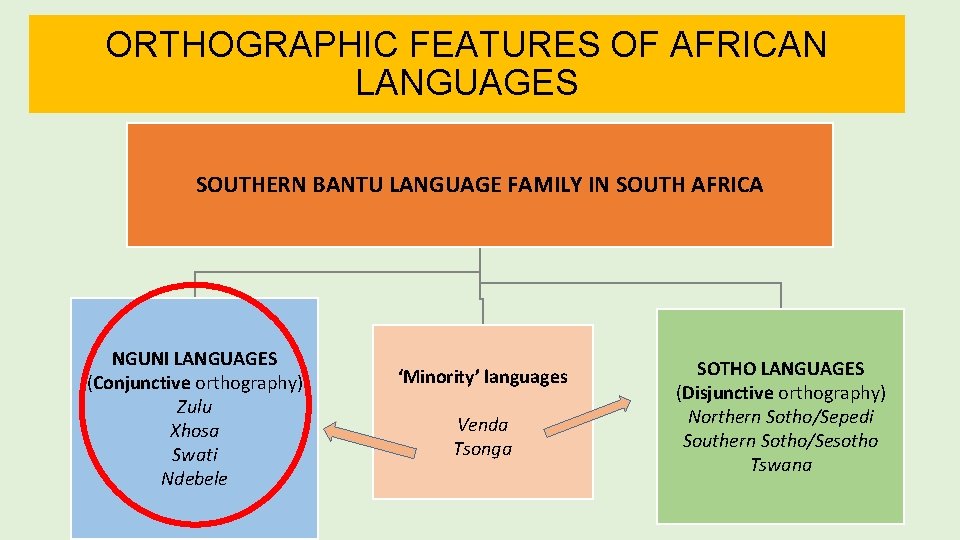

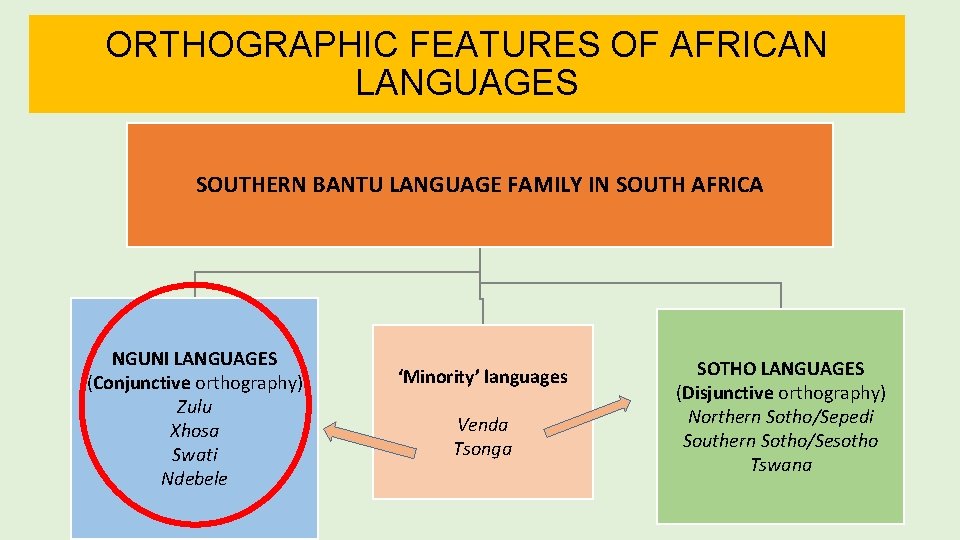

ORTHOGRAPHIC FEATURES OF AFRICAN LANGUAGES SOUTHERN BANTU LANGUAGE FAMILY IN SOUTH AFRICA NGUNI LANGUAGES (Conjunctive orthography) Zulu Xhosa Swati Ndebele ‘Minority’ languages Venda Tsonga SOTHO LANGUAGES (Disjunctive orthography) Northern Sotho/Sepedi Southern Sotho/Sesotho Tswana

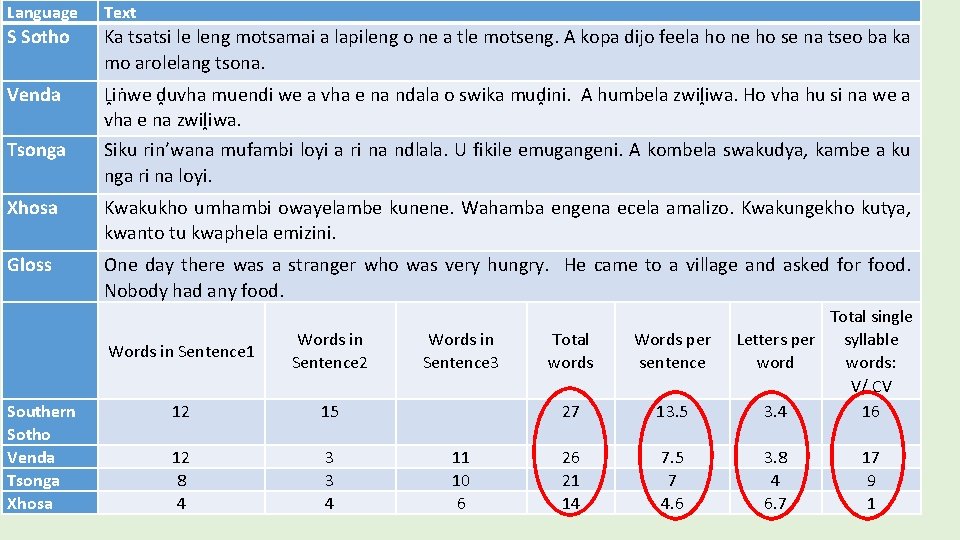

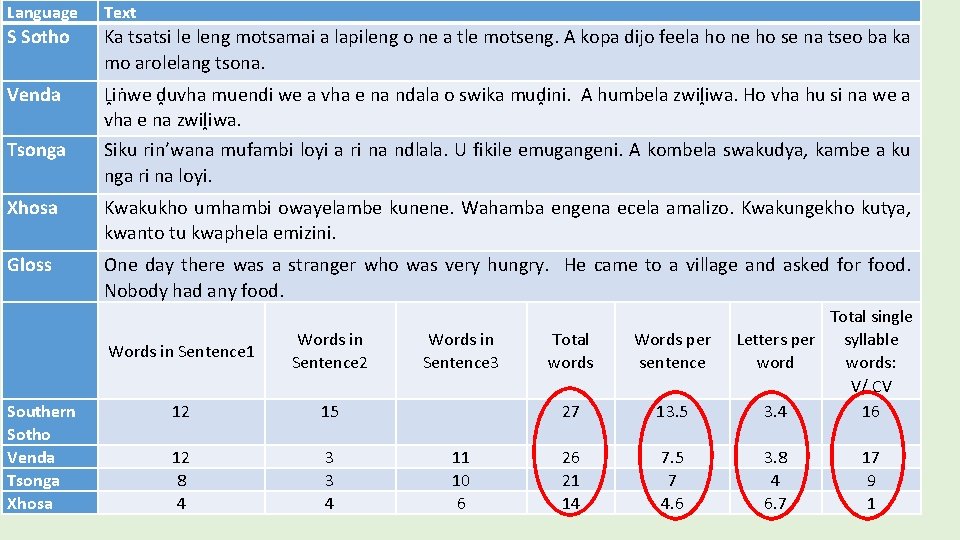

Language Text S Sotho Ka tsatsi le leng motsamai a lapileng o ne a tle motseng. A kopa dijo feela ho ne ho se na tseo ba ka mo arolelang tsona. Venda Ḽiṅwe ḓuvha muendi we a vha e na ndala o swika muḓini. A humbela zwiḽiwa. Ho vha hu si na we a vha e na zwiḽiwa. Siku rin’wana mufambi loyi a ri na ndlala. U fikile emugangeni. A kombela swakudya, kambe a ku nga ri na loyi. Tsonga Xhosa Kwakukho umhambi owayelambe kunene. Wahamba engena ecela amalizo. Kwakungekho kutya, kwanto tu kwaphela emizini. Gloss One day there was a stranger who was very hungry. He came to a village and asked for food. Nobody had any food. Southern Sotho Venda Tsonga Xhosa Words in Sentence 1 Words in Sentence 2 Words in Sentence 3 Total words Words per sentence 12 15 27 13. 5 12 8 4 3 3 4 11 10 6 26 21 14 7. 5 7 4. 6 Total single Letters per syllable words: V/ CV 3. 4 16 3. 8 4 6. 7 17 9 1

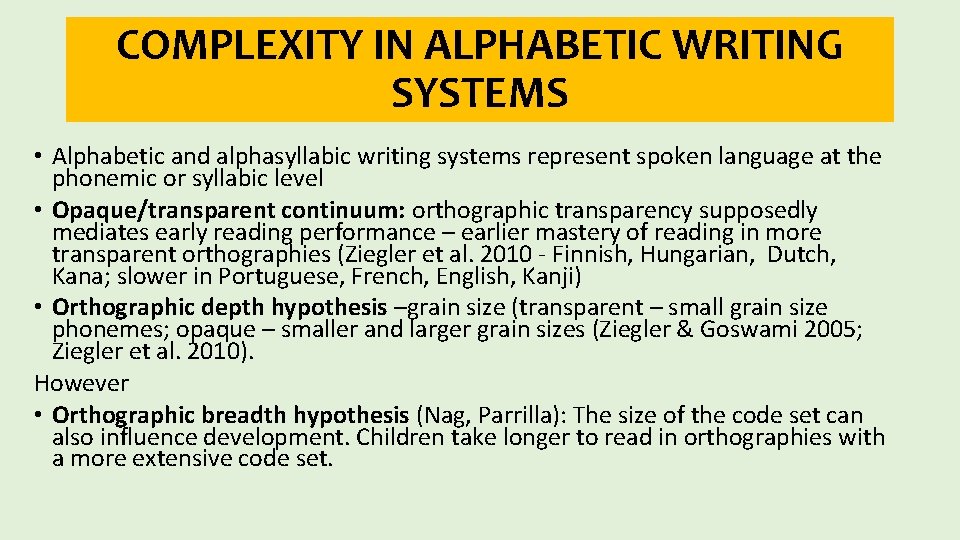

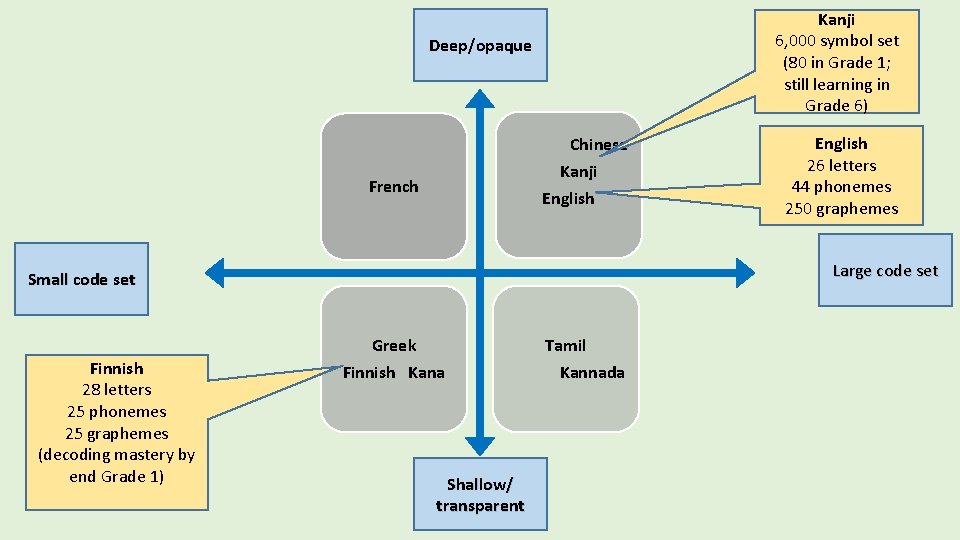

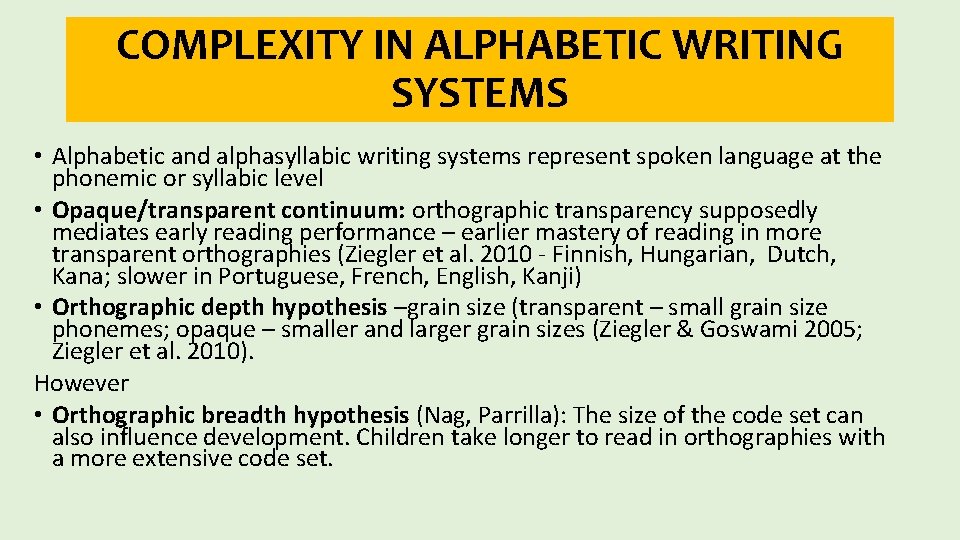

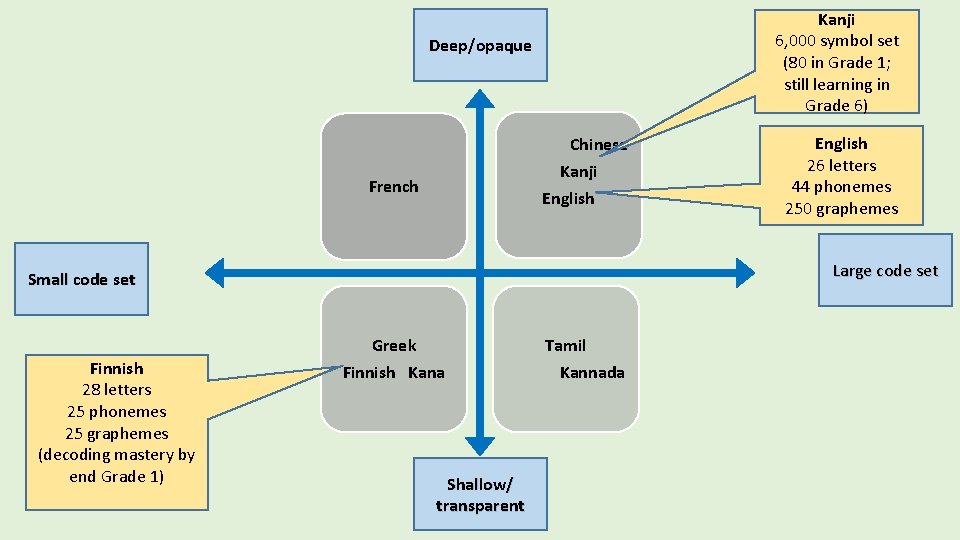

COMPLEXITY IN ALPHABETIC WRITING SYSTEMS • Alphabetic and alphasyllabic writing systems represent spoken language at the phonemic or syllabic level • Opaque/transparent continuum: orthographic transparency supposedly mediates early reading performance – earlier mastery of reading in more transparent orthographies (Ziegler et al. 2010 - Finnish, Hungarian, Dutch, Kana; slower in Portuguese, French, English, Kanji) • Orthographic depth hypothesis –grain size (transparent – small grain size phonemes; opaque – smaller and larger grain sizes (Ziegler & Goswami 2005; Ziegler et al. 2010). However • Orthographic breadth hypothesis (Nag, Parrilla): The size of the code set can also influence development. Children take longer to read in orthographies with a more extensive code set.

Kanji 6, 000 symbol set (80 in Grade 1; still learning in Grade 6) Deep/opaque Chinese Kanji French English Large code set Small code set Finnish 28 letters 25 phonemes 25 graphemes (decoding mastery by end Grade 1) English 26 letters 44 phonemes 250 graphemes Greek Finnish Kana Tamil Kannada Shallow/ transparent

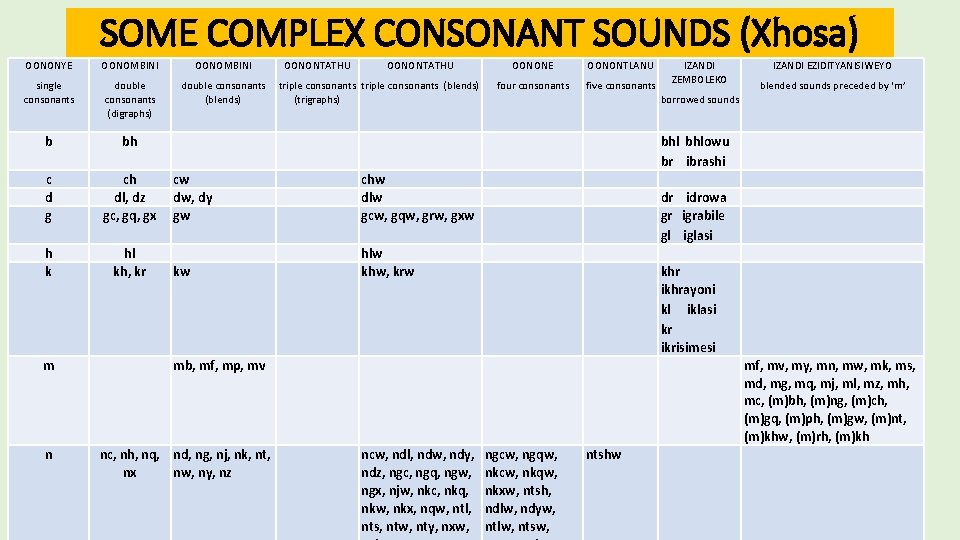

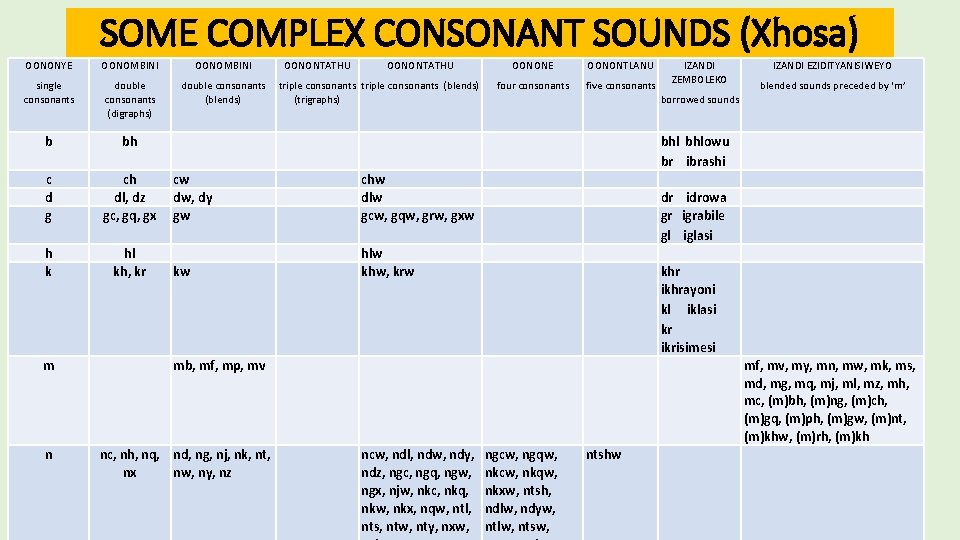

SOME COMPLEX CONSONANT SOUNDS (Xhosa) OONONYE OONOMBINI single consonants double consonants (digraphs) double consonants (blends) b bh c d g ch dl, dz gc, gq, gx h k hl kh, kr m n OONONTATHU triple consonants (blends) (trigraphs) OONONE OONONTLANU four consonants five consonants IZANDI ZEMBOLEKO cw dw, dy gw chw dlw gcw, gqw, grw, gxw kw hlw khw, krw bhlowu br ibrashi dr idrowa gr igrabile gl iglasi khr ikhrayoni kl iklasi kr ikrisimesi ncw, ndl, ndw, ndy, ndz, ngc, ngq, ngw, ngx, njw, nkc, nkq, nkw, nkx, nqw, ntl, nts, ntw, nty, nxw, ngcw, ngqw, nkcw, nkqw, nkxw, ntsh, ndlw, ndyw, ntlw, ntsw, ntshw nc, nh, nq, nd, ng, nj, nk, nt, nx nw, ny, nz blended sounds preceded by ‘m’ borrowed sounds mb, mf, mp, mv IZANDI EZIDITYANISIWEYO mf, mv, my, mn, mw, mk, ms, md, mg, mq, mj, ml, mz, mh, mc, (m)bh, (m)ng, (m)ch, (m)gq, (m)ph, (m)gw, (m)nt, (m)khw, (m)rh, (m)kh

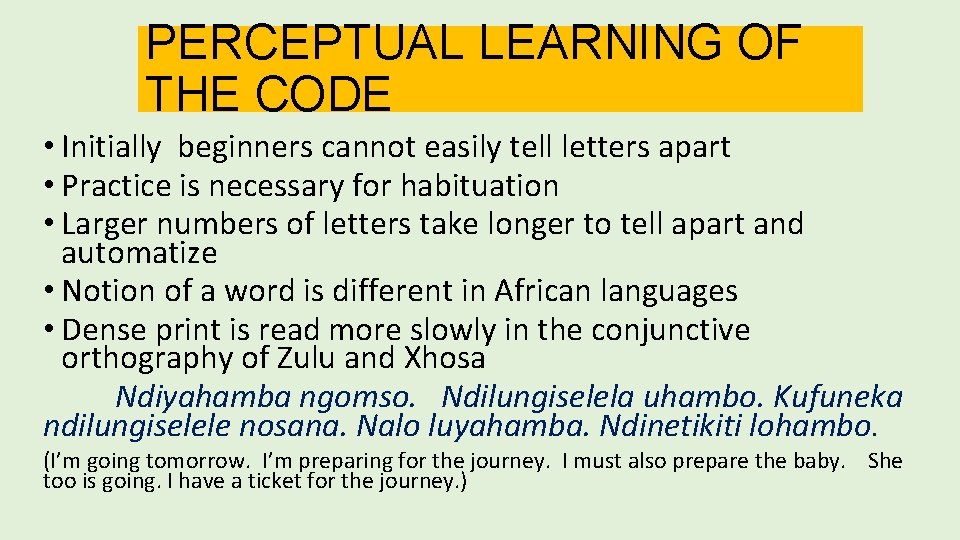

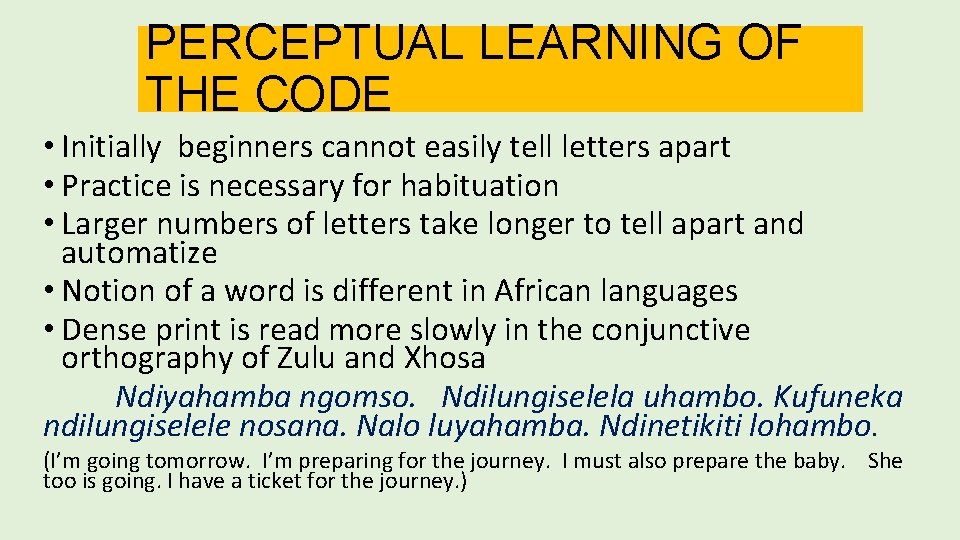

PERCEPTUAL LEARNING OF THE CODE • Initially beginners cannot easily tell letters apart • Practice is necessary for habituation • Larger numbers of letters take longer to tell apart and automatize • Notion of a word is different in African languages • Dense print is read more slowly in the conjunctive orthography of Zulu and Xhosa Ndiyahamba ngomso. Ndilungiselela uhambo. Kufuneka ndilungiselele nosana. Nalo luyahamba. Ndinetikiti lohambo. (I’m going tomorrow. I’m preparing for the journey. I must also prepare the baby. She too is going. I have a ticket for the journey. )

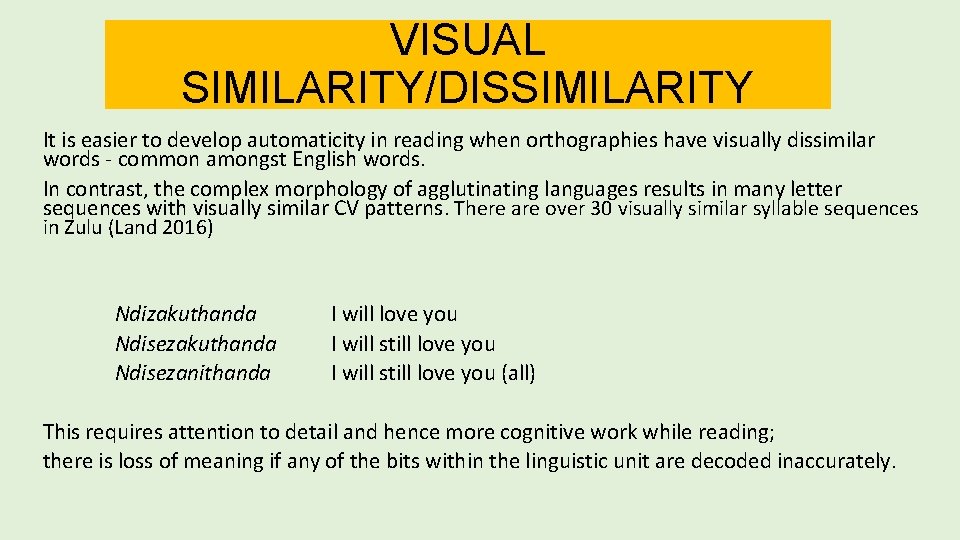

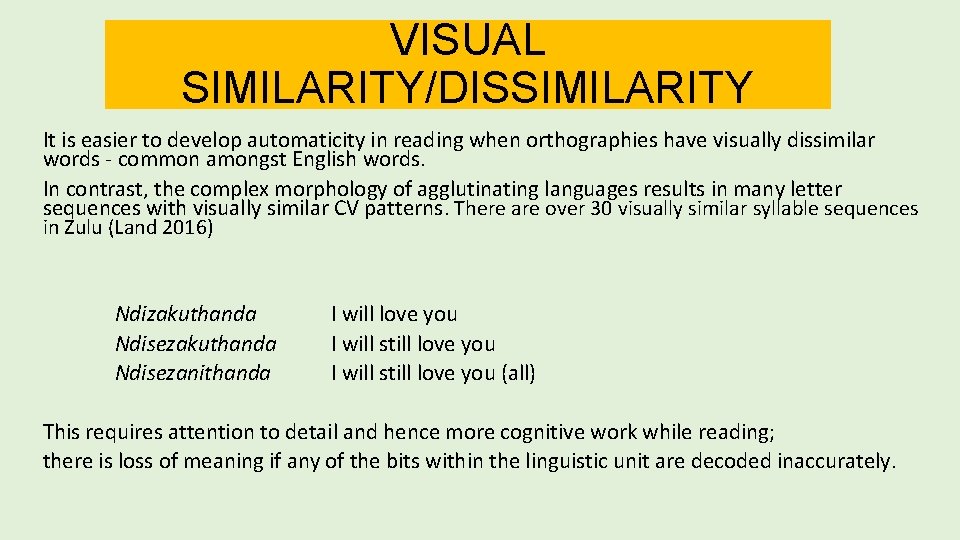

VISUAL SIMILARITY/DISSIMILARITY It is easier to develop automaticity in reading when orthographies have visually dissimilar words - common amongst English words. In contrast, the complex morphology of agglutinating languages results in many letter sequences with visually similar CV patterns. There are over 30 visually similar syllable sequences in Zulu (Land 2016) Ndizakuthanda Ndisezanithanda I will love you I will still love you (all) This requires attention to detail and hence more cognitive work while reading; there is loss of meaning if any of the bits within the linguistic unit are decoded inaccurately.

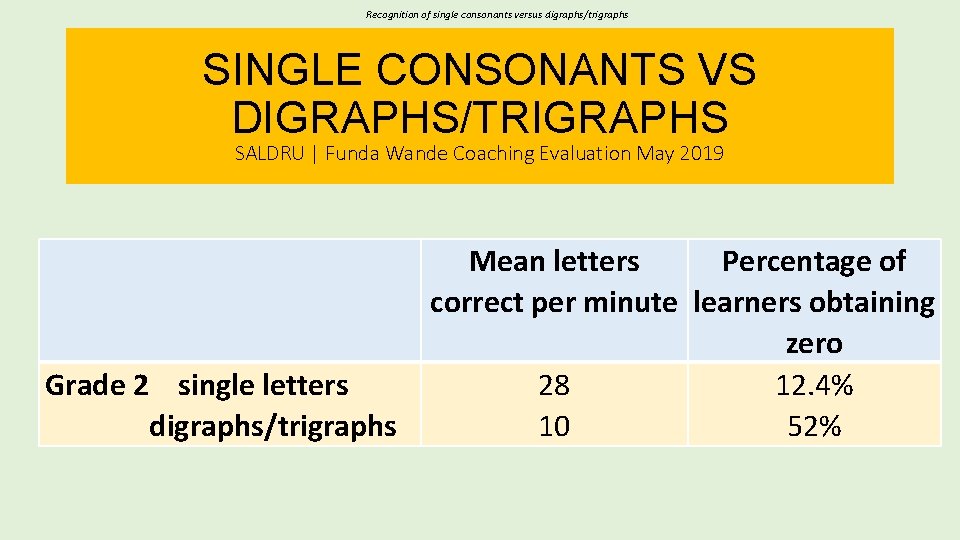

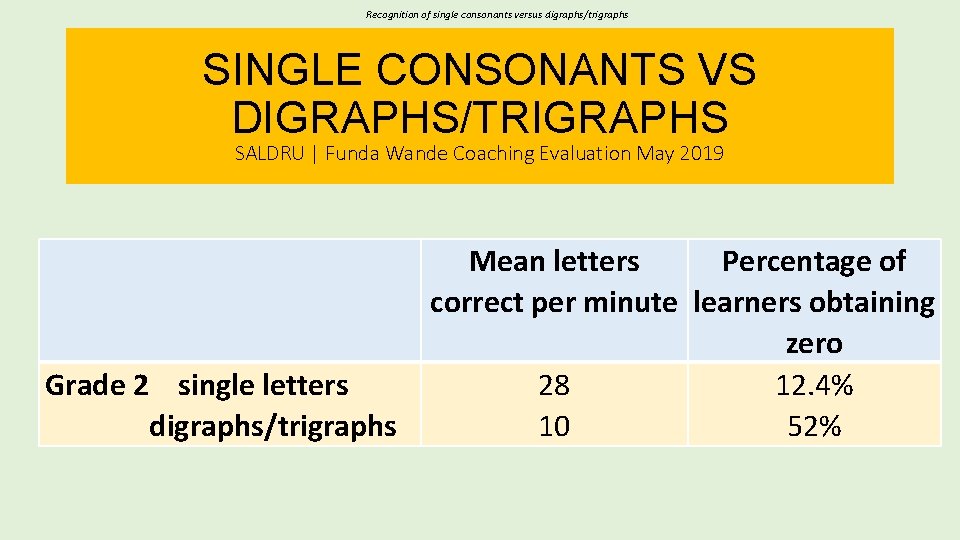

Recognition of single consonants versus digraphs/trigraphs SINGLE CONSONANTS VS DIGRAPHS/TRIGRAPHS SALDRU | Funda Wande Coaching Evaluation May 2019 Grade 2 single letters digraphs/trigraphs Mean letters Percentage of correct per minute learners obtaining zero 28 12. 4% 10 52%

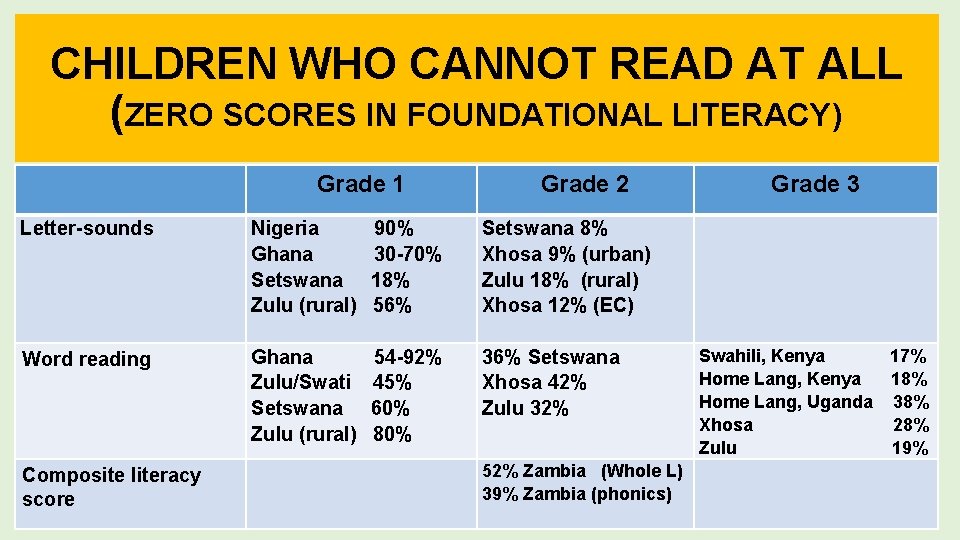

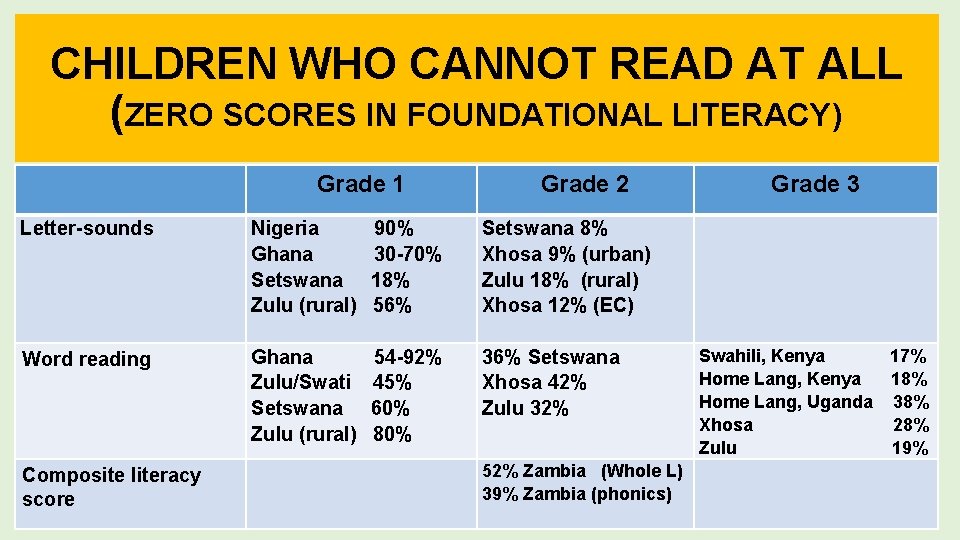

CHILDREN WHO CANNOT READ AT ALL (ZERO SCORES IN FOUNDATIONAL LITERACY) Grade 1 Grade 2 Letter-sounds Nigeria 90% Ghana 30 -70% Setswana 18% Zulu (rural) 56% Setswana 8% Xhosa 9% (urban) Zulu 18% (rural) Xhosa 12% (EC) Word reading Ghana 54 -92% Zulu/Swati 45% Setswana 60% Zulu (rural) 80% 36% Setswana Xhosa 42% Zulu 32% Composite literacy score Grade 3 Swahili, Kenya 17% Home Lang, Kenya 18% Home Lang, Uganda 38% Xhosa 28% Zulu 19% 52% Zambia (Whole L) 39% Zambia (phonics)

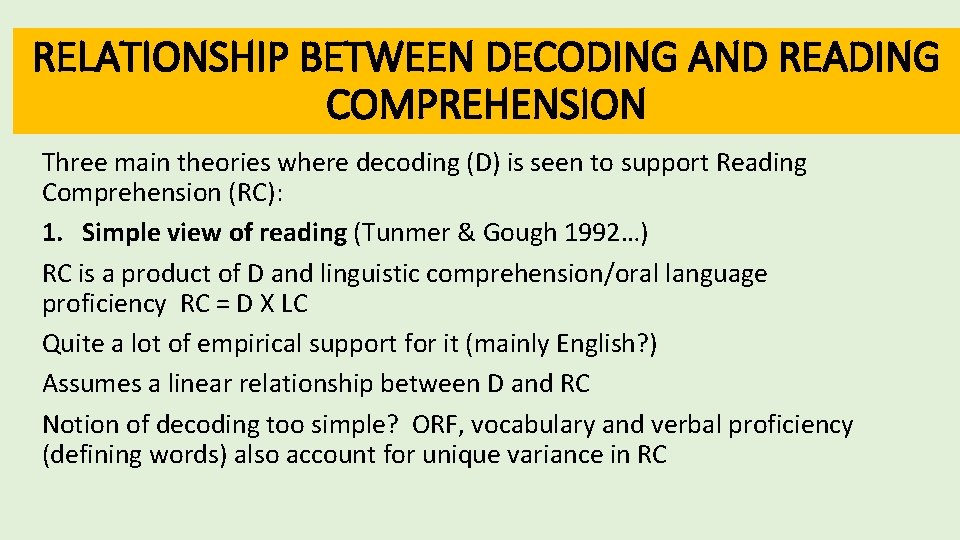

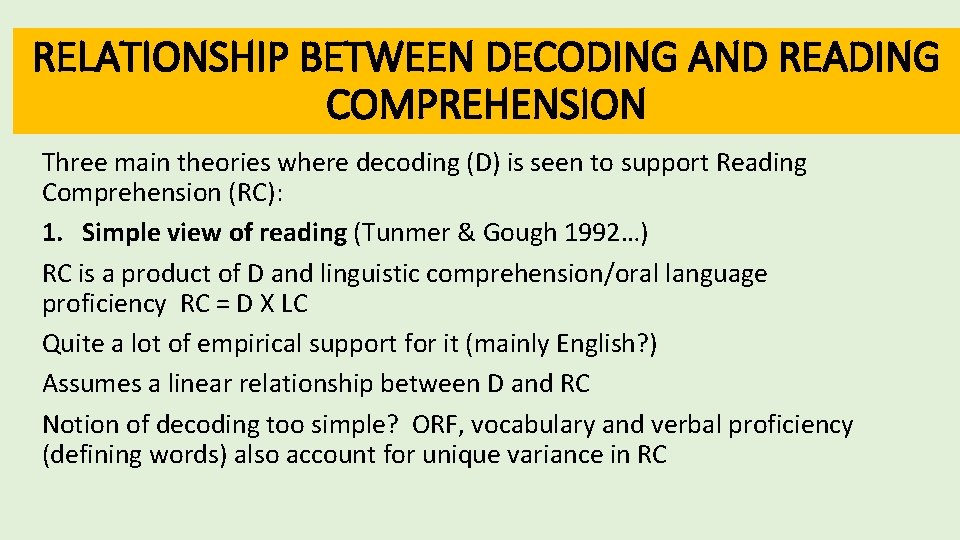

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN DECODING AND READING COMPREHENSION Three main theories where decoding (D) is seen to support Reading Comprehension (RC): 1. Simple view of reading (Tunmer & Gough 1992…) RC is a product of D and linguistic comprehension/oral language proficiency RC = D X LC Quite a lot of empirical support for it (mainly English? ) Assumes a linear relationship between D and RC Notion of decoding too simple? ORF, vocabulary and verbal proficiency (defining words) also account for unique variance in RC

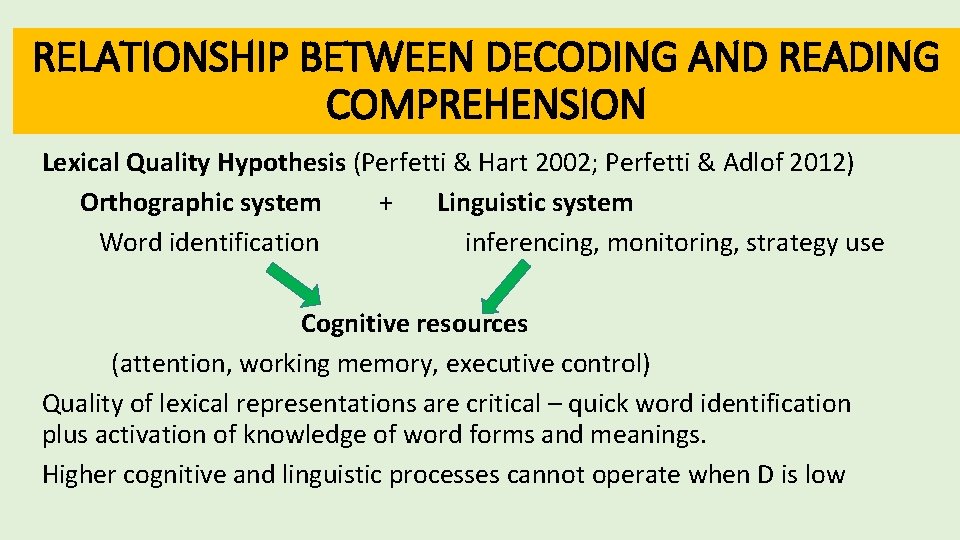

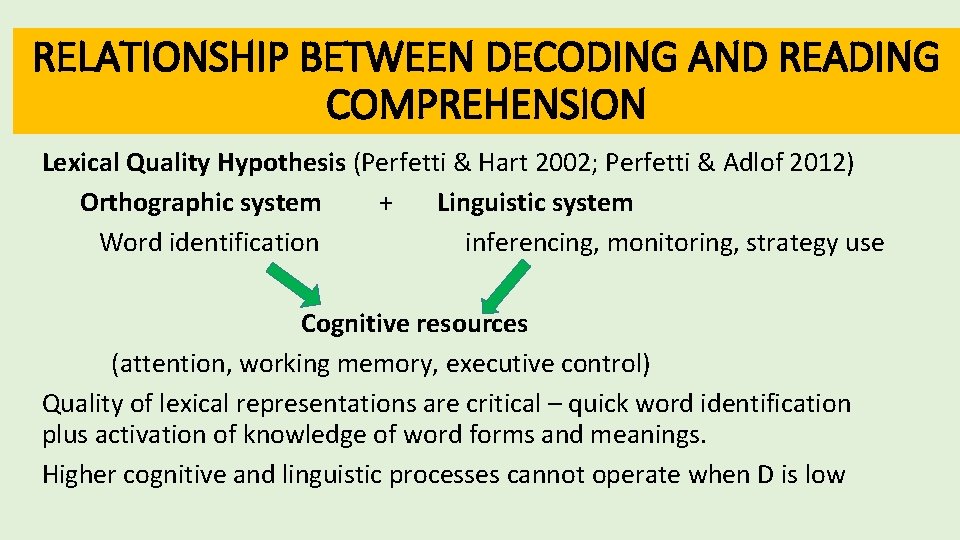

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN DECODING AND READING COMPREHENSION Lexical Quality Hypothesis (Perfetti & Hart 2002; Perfetti & Adlof 2012) Orthographic system + Linguistic system Word identification inferencing, monitoring, strategy use Cognitive resources (attention, working memory, executive control) Quality of lexical representations are critical – quick word identification plus activation of knowledge of word forms and meanings. Higher cognitive and linguistic processes cannot operate when D is low

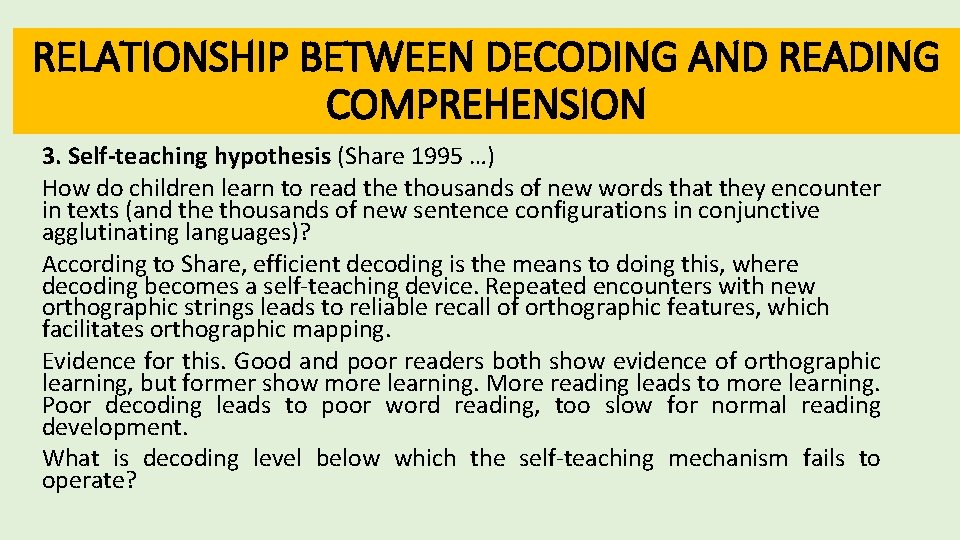

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN DECODING AND READING COMPREHENSION 3. Self-teaching hypothesis (Share 1995 …) How do children learn to read the thousands of new words that they encounter in texts (and the thousands of new sentence configurations in conjunctive agglutinating languages)? According to Share, efficient decoding is the means to doing this, where decoding becomes a self-teaching device. Repeated encounters with new orthographic strings leads to reliable recall of orthographic features, which facilitates orthographic mapping. Evidence for this. Good and poor readers both show evidence of orthographic learning, but former show more learning. More reading leads to more learning. Poor decoding leads to poor word reading, too slow for normal reading development. What is decoding level below which the self-teaching mechanism fails to operate?

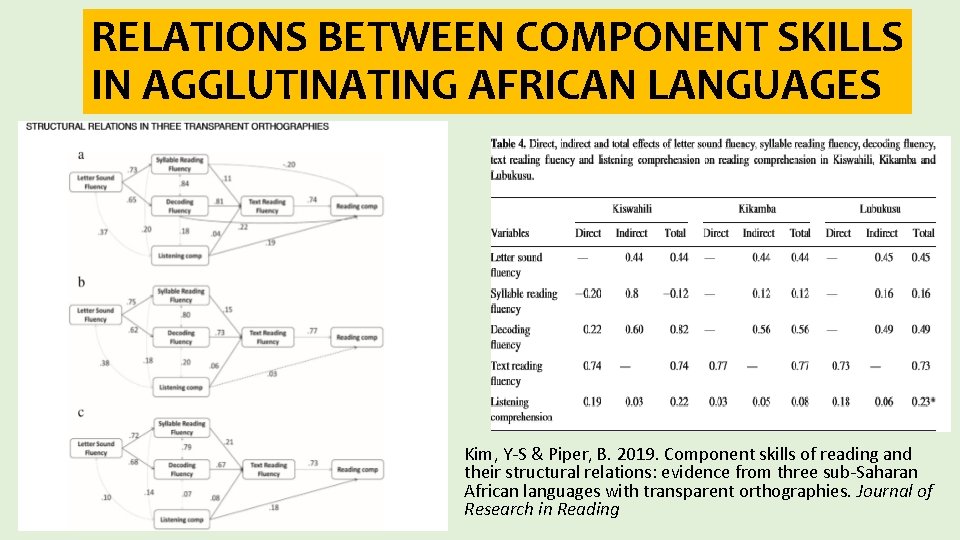

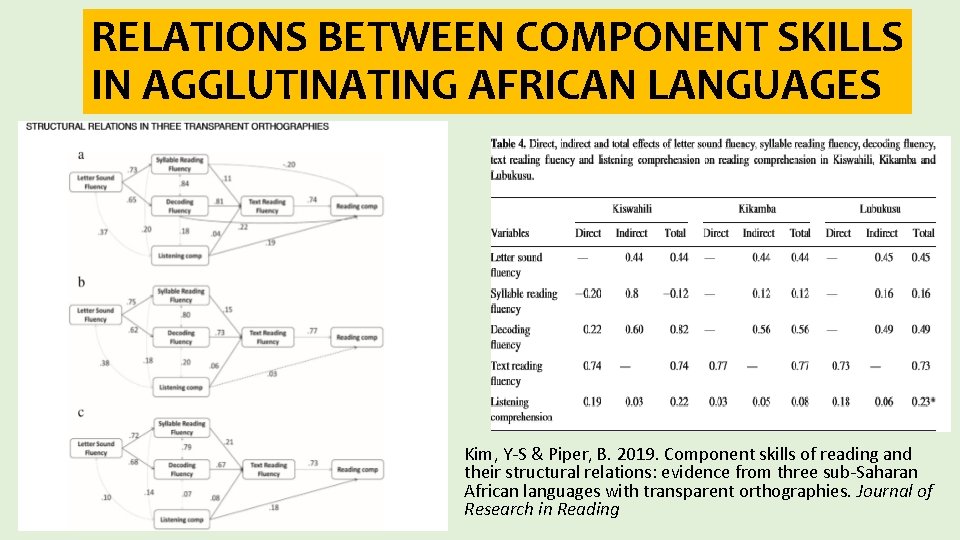

RELATIONS BETWEEN COMPONENT SKILLS IN AGGLUTINATING AFRICAN LANGUAGES Kim, Y-S & Piper, B. 2019. Component skills of reading and their structural relations: evidence from three sub-Saharan African languages with transparent orthographies. Journal of Research in Reading

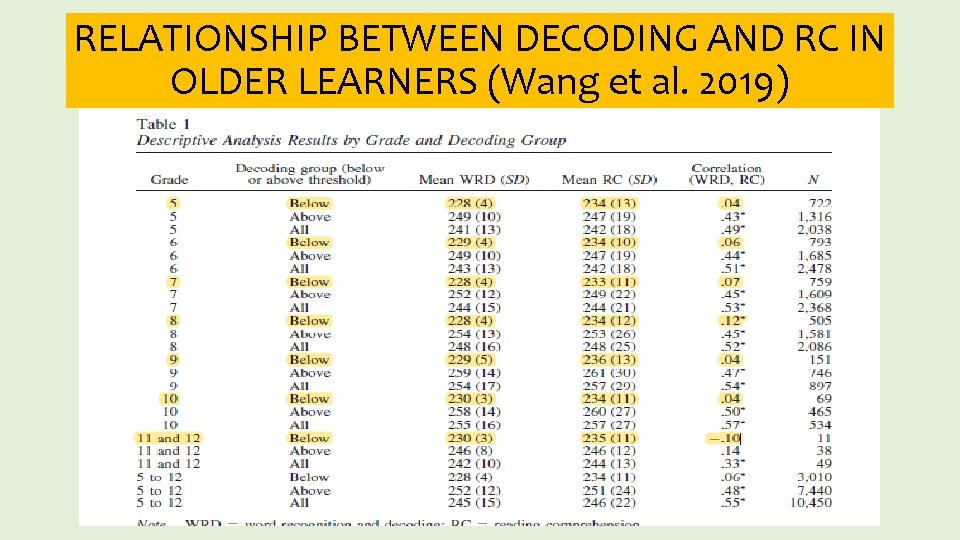

THE DECODING THRESHOLD HYPOTHESIS The relationship between D and RC is non-linear. The relationship becomes unpredictable when it falls below a threshold. Readers below the D threshold make very little progress in RC over time. There may also be an upper bound, where high D no longer predicts high level, nuanced RC (necessary but not sufficient) Evidence of lower bound for older readers – Grades 5 -12 (n=10, 000; n= 30, 000) (Wang et al. 2019) The D threshold remained stable over the grades, suggesting that [once fundational skills have developed] it is not a function of grade level but of decoding ability. What drives RC in absence of D threshold? Possible compensatory factors = background knowledge, inferencing, metacognition, contextual guessing? But little evidence of this. The development of RC flattens out – very little driving it.

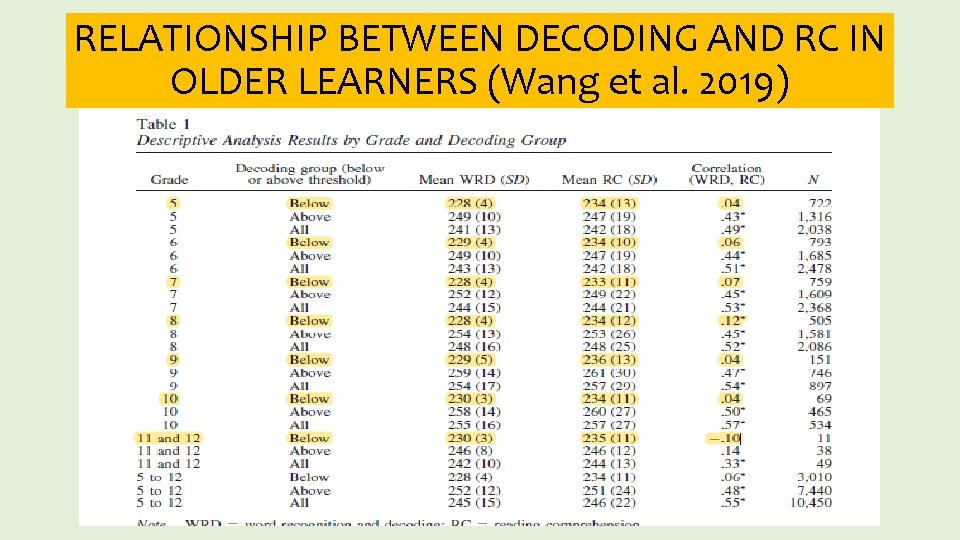

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN DECODING AND RC IN OLDER LEARNERS (Wang et al. 2019)

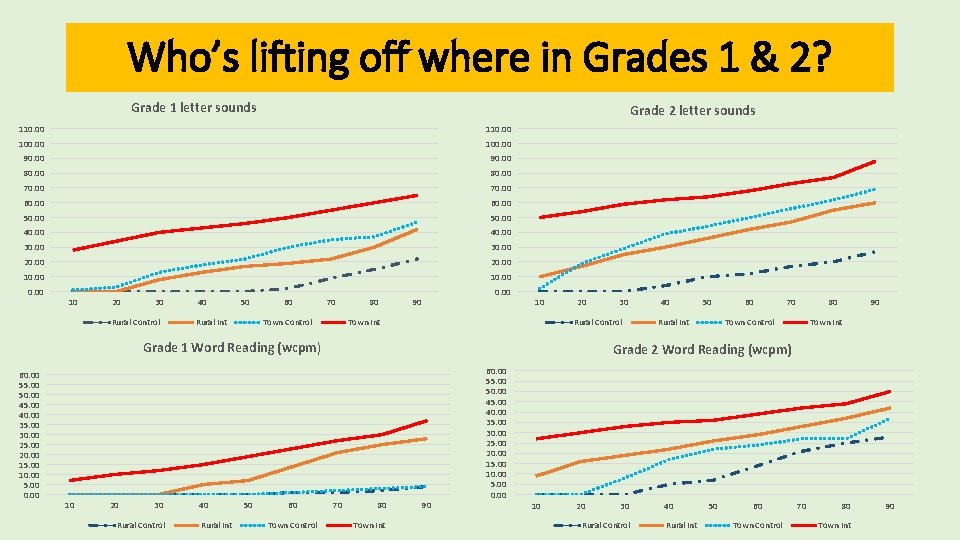

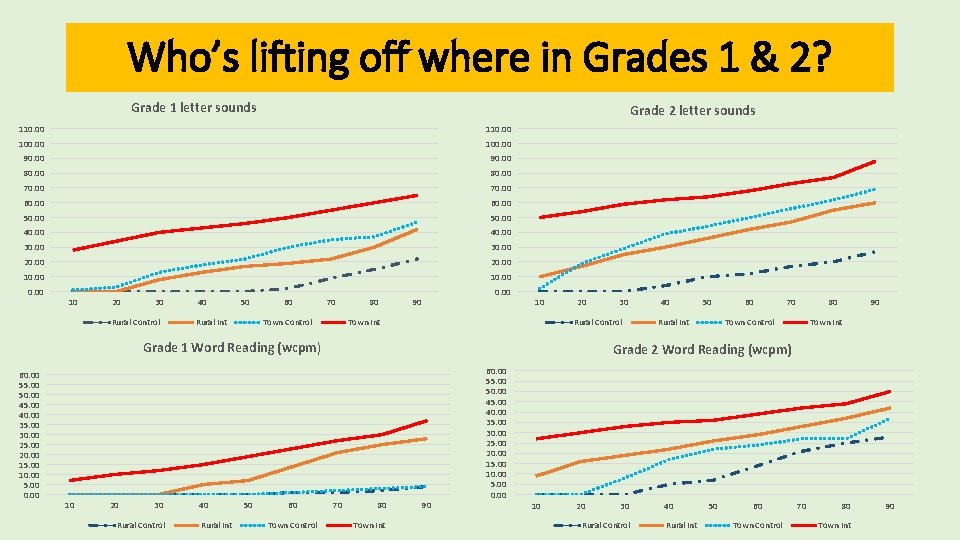

Who’s lifting off where in Grades 1 & 2? Grade 1 letter sounds Grade 2 letter sounds 110. 00 100. 00 90. 00 80. 00 70. 00 60. 00 50. 00 40. 00 30. 00 20. 00 10 20 30 Rural Control 40 50 Rural Int 60 70 Town Control 80 0. 00 90 10 Town Int 20 Rural Control Grade 1 Word Reading (wcpm) 60. 00 55. 00 50. 00 45. 00 40. 00 35. 00 30. 00 25. 00 20. 00 15. 00 10. 00 5. 00 0. 00 10 20 30 Rural Control 40 Rural Int 50 60 Town Control 30 40 50 Rural Int 60 70 80 Town Control 90 Town Int Grade 2 Word Reading (wcpm) 70 80 Town Int 90 60. 00 55. 00 50. 00 45. 00 40. 00 35. 00 30. 00 25. 00 20. 00 15. 00 10. 00 5. 00 0. 00 10 20 30 Rural Control 40 Rural Int 50 60 Town Control 70 80 Town Int 90

CHUNKING, COMPLEXITY TRADE-OFFS, THRESHOLDS AND PEDAGOGY Even though orthographic input is not ephemeral, the now-or-never strategy applies to reading –we can read with comprehension much faster than we can listen with comprehension. Children need help with chunk-and-pass in the orthographic code Trade-offs in complexity in different codes Different time windows for learning now-or-never strategies Pedagogy can moderate these complexity effects Being aware of thresholds can help teachers identify and support struggling learners

THANK YOU Human history becomes more and more a race between education and catastrophe HG Wells