Comparative Religion Policy Understanding Patterns of Religious Participation

- Slides: 10

Comparative Religion Policy: Understanding Patterns of Religious Participation in Policy Networks and the Political Manipulation of Religious Organizations Michael D. Mc. Ginnis Department of Political Science and Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis, Indiana University, Bloomington mcginnis@indiana. edu International Studies Association, San Francisco, March 27, 2008

Comparative Analysis of Religion Policy Extensive research programs on religion’s effects on politics or policy: – Justification for political violence, terror – Inspiration for pacifism, non-violent resistance, peace, reconciliation, humanitarian assistance, calls for justice – Contribution to foundation for capitalism, democracy, development – Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations thesis – Controversy regarding Charitable Choice and Faith-based Initiative Extensive research on religious participation and mobilization – Secularization thesis – Rise of fundamentalism and religious nationalism – Competition in religious markets Little research comparing governments’ policies toward religion(s) – All governments regulate religious markets to some extent. – Wide variation in specific policies, yet some common patterns

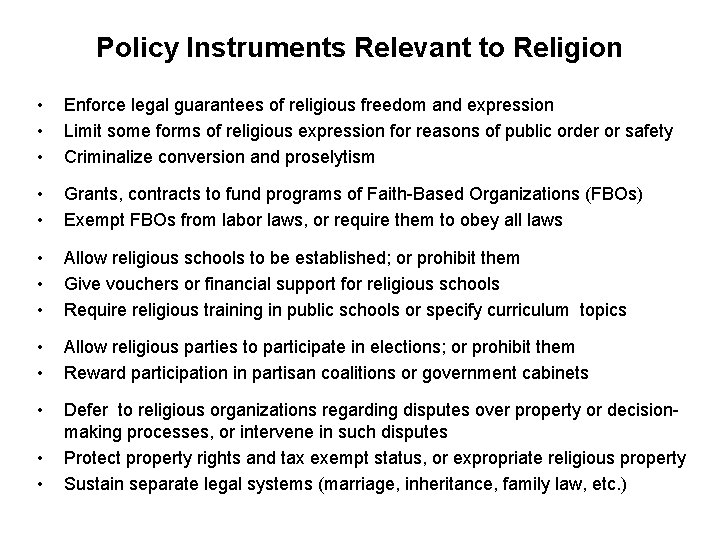

Policy Instruments Relevant to Religion • • • Enforce legal guarantees of religious freedom and expression Limit some forms of religious expression for reasons of public order or safety Criminalize conversion and proselytism • • Grants, contracts to fund programs of Faith-Based Organizations (FBOs) Exempt FBOs from labor laws, or require them to obey all laws • • • Allow religious schools to be established; or prohibit them Give vouchers or financial support for religious schools Require religious training in public schools or specify curriculum topics • • Allow religious parties to participate in elections; or prohibit them Reward participation in partisan coalitions or government cabinets • Defer to religious organizations regarding disputes over property or decisionmaking processes, or intervene in such disputes Protect property rights and tax exempt status, or expropriate religious property Sustain separate legal systems (marriage, inheritance, family law, etc. ) • •

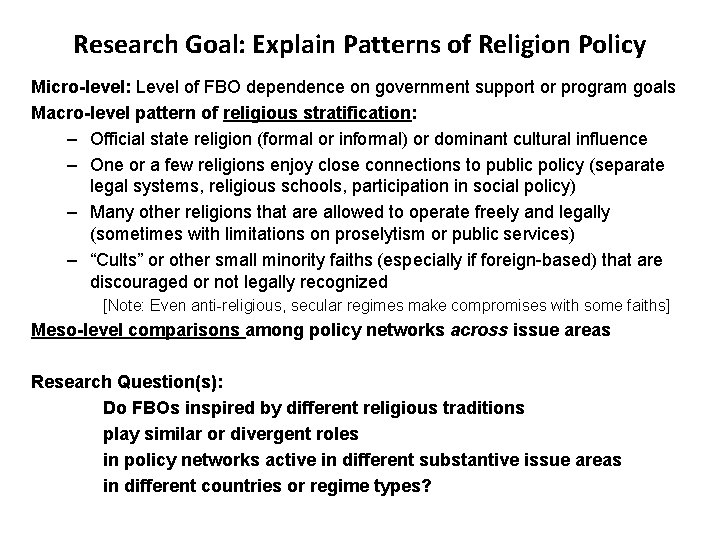

Research Goal: Explain Patterns of Religion Policy Micro-level: Level of FBO dependence on government support or program goals Macro-level pattern of religious stratification: – Official state religion (formal or informal) or dominant cultural influence – One or a few religions enjoy close connections to public policy (separate legal systems, religious schools, participation in social policy) – Many other religions that are allowed to operate freely and legally (sometimes with limitations on proselytism or public services) – “Cults” or other small minority faiths (especially if foreign-based) that are discouraged or not legally recognized [Note: Even anti-religious, secular regimes make compromises with some faiths] Meso-level comparisons among policy networks across issue areas Research Question(s): Do FBOs inspired by different religious traditions play similar or divergent roles in policy networks active in different substantive issue areas in different countries or regime types?

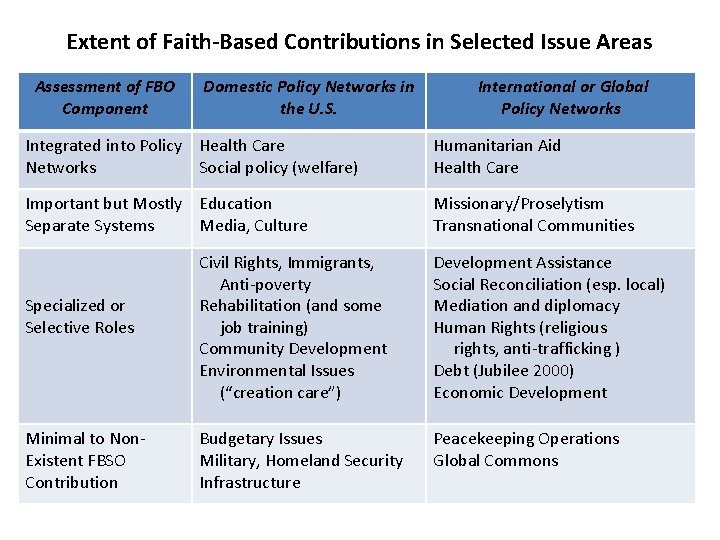

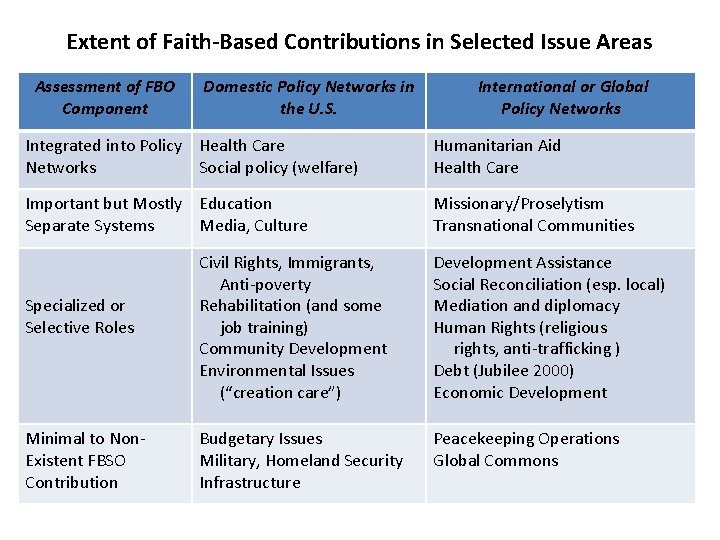

Extent of Faith-Based Contributions in Selected Issue Areas Assessment of FBO Component Domestic Policy Networks in the U. S. International or Global Policy Networks Integrated into Policy Health Care Networks Social policy (welfare) Humanitarian Aid Health Care Important but Mostly Education Separate Systems Media, Culture Missionary/Proselytism Transnational Communities Specialized or Selective Roles Minimal to Non. Existent FBSO Contribution Civil Rights, Immigrants, Anti-poverty Rehabilitation (and some job training) Community Development Environmental Issues (“creation care”) Development Assistance Social Reconciliation (esp. local) Mediation and diplomacy Human Rights (religious rights, anti-trafficking ) Debt (Jubilee 2000) Economic Development Budgetary Issues Military, Homeland Security Infrastructure Peacekeeping Operations Global Commons

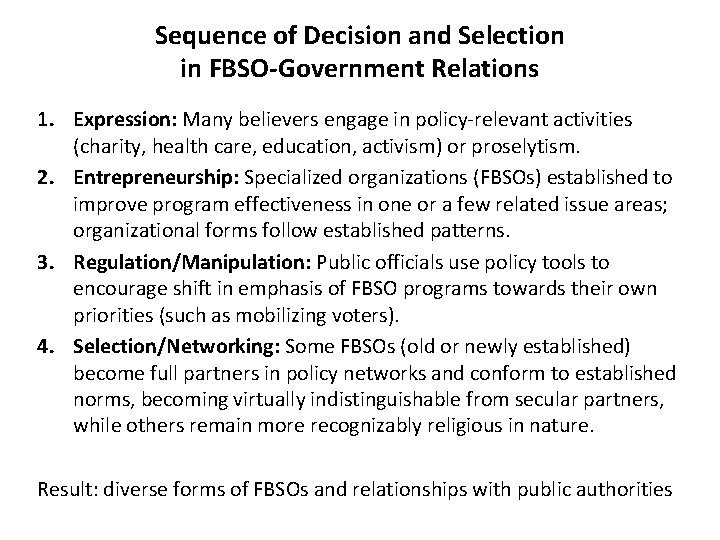

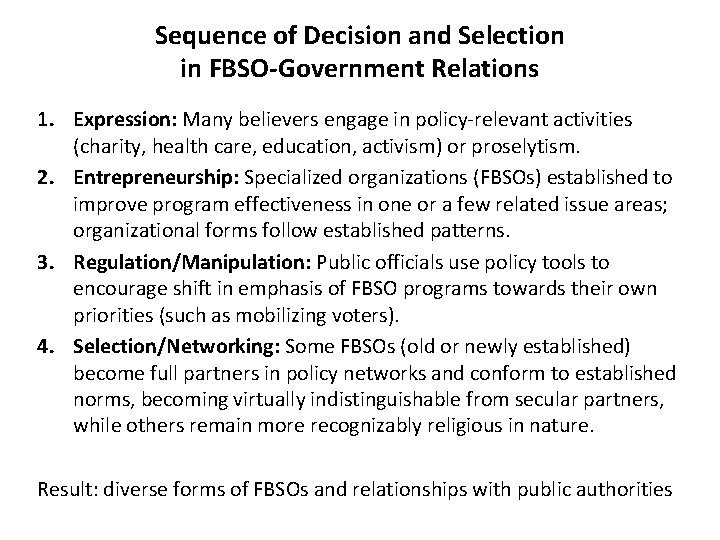

Sequence of Decision and Selection in FBSO-Government Relations 1. Expression: Many believers engage in policy-relevant activities (charity, health care, education, activism) or proselytism. 2. Entrepreneurship: Specialized organizations (FBSOs) established to improve program effectiveness in one or a few related issue areas; organizational forms follow established patterns. 3. Regulation/Manipulation: Public officials use policy tools to encourage shift in emphasis of FBSO programs towards their own priorities (such as mobilizing voters). 4. Selection/Networking: Some FBSOs (old or newly established) become full partners in policy networks and conform to established norms, becoming virtually indistinguishable from secular partners, while others remain more recognizably religious in nature. Result: diverse forms of FBSOs and relationships with public authorities

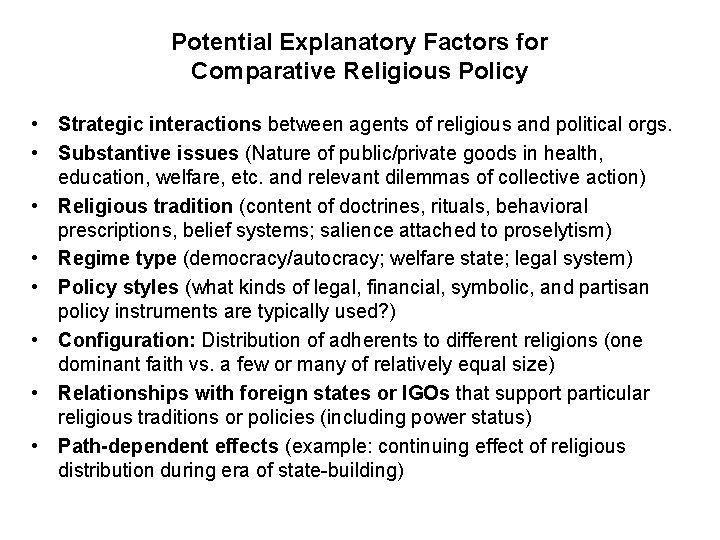

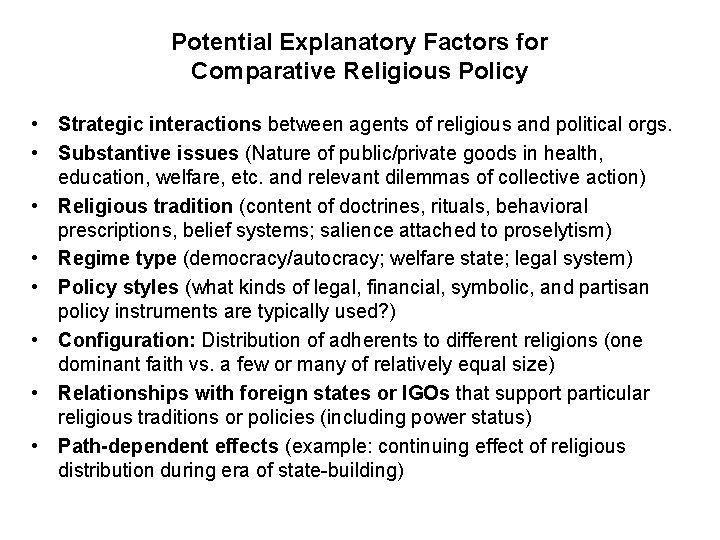

Potential Explanatory Factors for Comparative Religious Policy • Strategic interactions between agents of religious and political orgs. • Substantive issues (Nature of public/private goods in health, education, welfare, etc. and relevant dilemmas of collective action) • Religious tradition (content of doctrines, rituals, behavioral prescriptions, belief systems; salience attached to proselytism) • Regime type (democracy/autocracy; welfare state; legal system) • Policy styles (what kinds of legal, financial, symbolic, and partisan policy instruments are typically used? ) • Configuration: Distribution of adherents to different religions (one dominant faith vs. a few or many of relatively equal size) • Relationships with foreign states or IGOs that support particular religious traditions or policies (including power status) • Path-dependent effects (example: continuing effect of religious distribution during era of state-building)

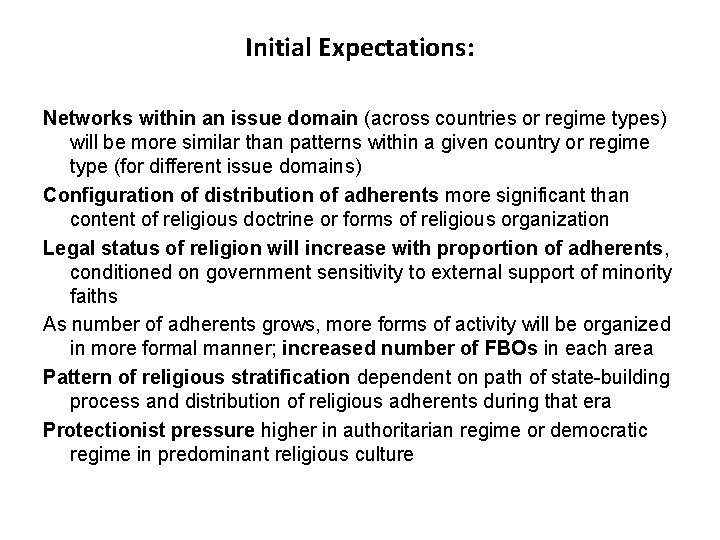

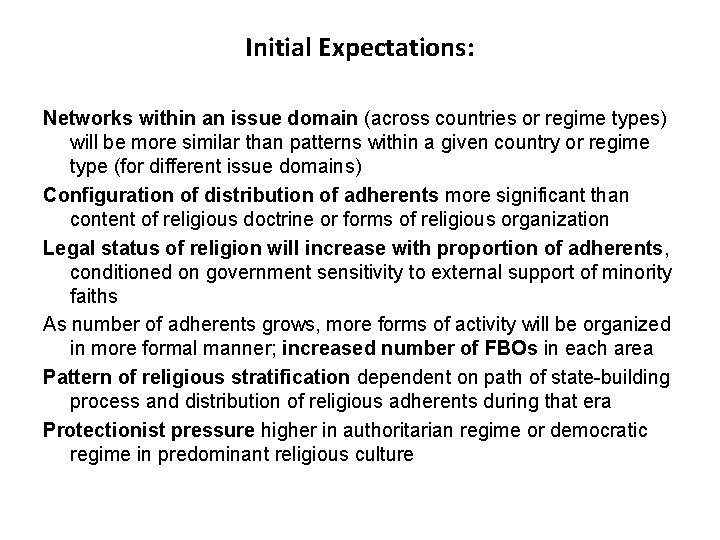

Initial Expectations: Networks within an issue domain (across countries or regime types) will be more similar than patterns within a given country or regime type (for different issue domains) Configuration of distribution of adherents more significant than content of religious doctrine or forms of religious organization Legal status of religion will increase with proportion of adherents, conditioned on government sensitivity to external support of minority faiths As number of adherents grows, more forms of activity will be organized in more formal manner; increased number of FBOs in each area Pattern of religious stratification dependent on path of state-building process and distribution of religious adherents during that era Protectionist pressure higher in authoritarian regime or democratic regime in predominant religious culture

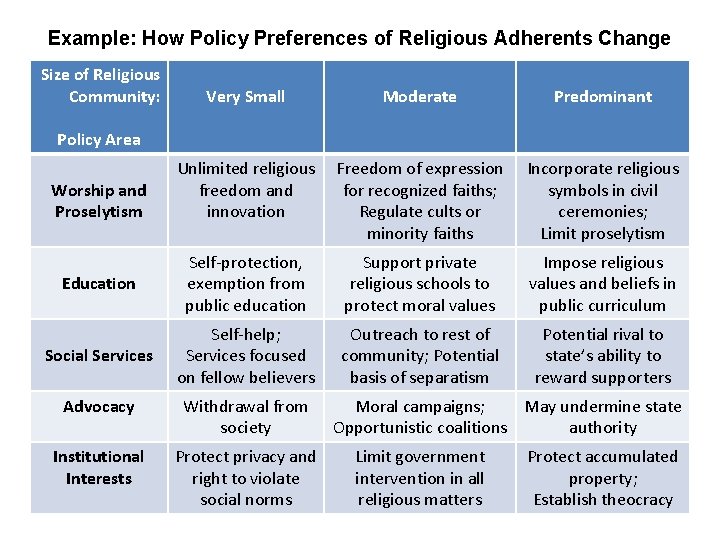

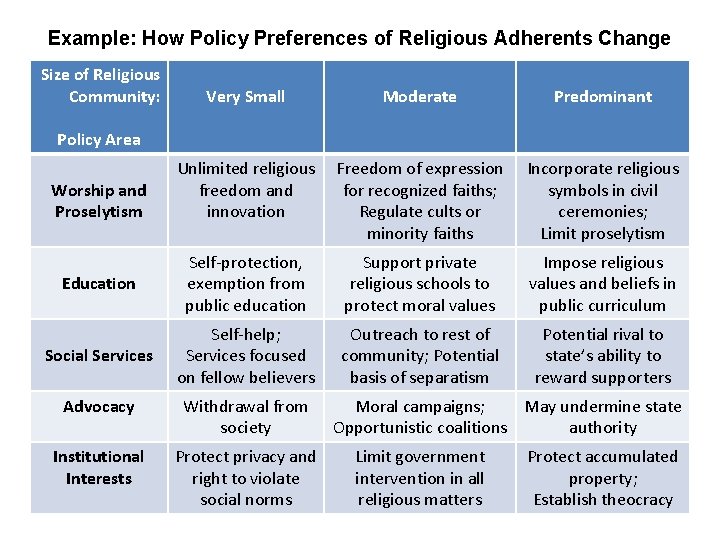

Example: How Policy Preferences of Religious Adherents Change Size of Religious Community: Very Small Moderate Predominant Unlimited religious freedom and innovation Freedom of expression for recognized faiths; Regulate cults or minority faiths Incorporate religious symbols in civil ceremonies; Limit proselytism Education Self-protection, exemption from public education Support private religious schools to protect moral values Impose religious values and beliefs in public curriculum Social Services Self-help; Services focused on fellow believers Outreach to rest of community; Potential basis of separatism Potential rival to state’s ability to reward supporters Policy Area Worship and Proselytism Advocacy Withdrawal from society Institutional Interests Protect privacy and right to violate social norms Moral campaigns; May undermine state Opportunistic coalitions authority Limit government intervention in all religious matters Protect accumulated property; Establish theocracy

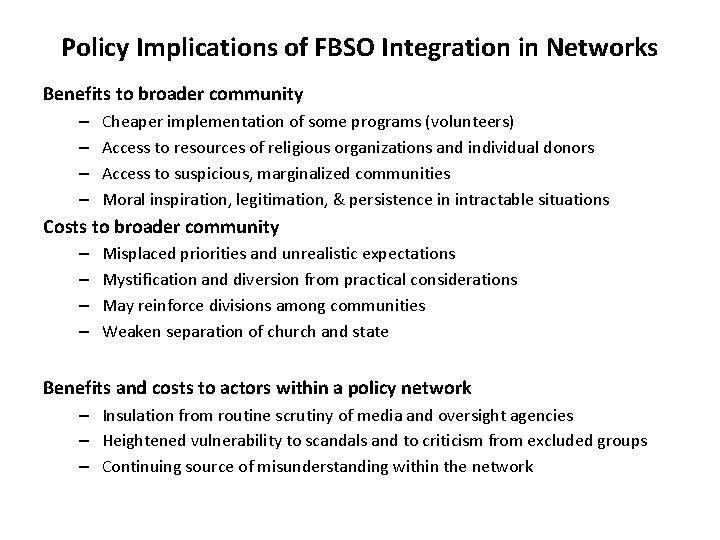

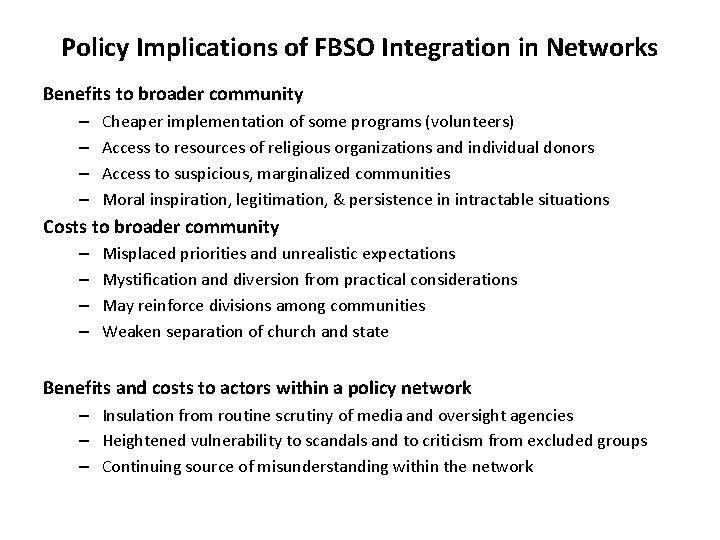

Policy Implications of FBSO Integration in Networks Benefits to broader community – – Cheaper implementation of some programs (volunteers) Access to resources of religious organizations and individual donors Access to suspicious, marginalized communities Moral inspiration, legitimation, & persistence in intractable situations Costs to broader community – – Misplaced priorities and unrealistic expectations Mystification and diversion from practical considerations May reinforce divisions among communities Weaken separation of church and state Benefits and costs to actors within a policy network – Insulation from routine scrutiny of media and oversight agencies – Heightened vulnerability to scandals and to criticism from excluded groups – Continuing source of misunderstanding within the network