COMPARATIVE ANATOMY OF DIGESTIVE SYSTEM IN VERTEBRATES B

COMPARATIVE ANATOMY OF DIGESTIVE SYSTEM IN VERTEBRATES B. Sc. (H), SEM II: ZOOL-H-DC 4 -T Dr. Dip Mukherjee Head & Assistant Professor of Zoology S. B. S. Government College, Hili Delivered on: 04. 01. 2020

Introduction Ø The stomach is an expanded structure that functions in mechanical and chemical digestion and as temporary storage in irregularly feeding animals. Ø It is an extremely acidic (p. H of 2) environment due to the production of HCl. Ø Processes of the stomach include mechanical digestion through churning, chemical digestion of proteins, production of mucus for protection, absorption of vitamins, water, salts & alcohol. Ø The stomach produces HCl, enzymes and mucus from glands found in gastric pits. Ø After a period of time the churning produces a slurry mixture of food, HCl, enzymes & mucus called chyme. Ø The inner lining has large folds called rugae which increases surface area and allows for expansion. •

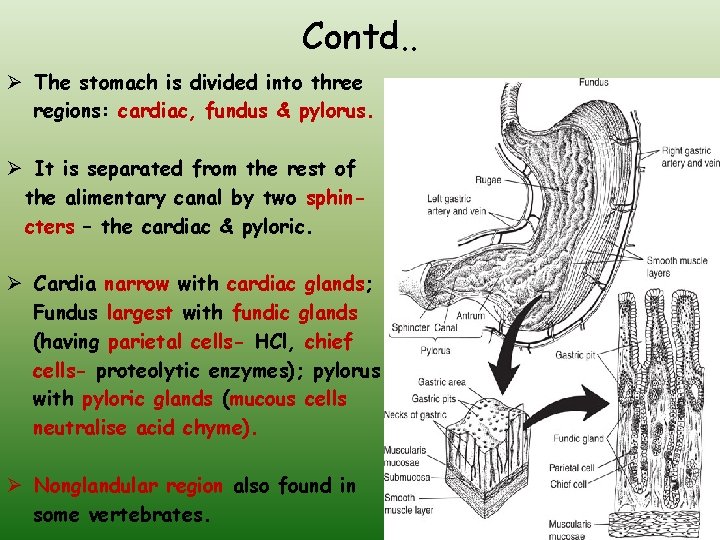

Contd. . Ø The stomach is divided into three regions: cardiac, fundus & pylorus. Ø It is separated from the rest of the alimentary canal by two sphincters – the cardiac & pyloric. Ø Cardia narrow with cardiac glands; Fundus largest with fundic glands (having parietal cells- HCl, chief cells- proteolytic enzymes); pylorus with pyloric glands (mucous cells neutralise acid chyme). Ø Nonglandular region also found in some vertebrates.

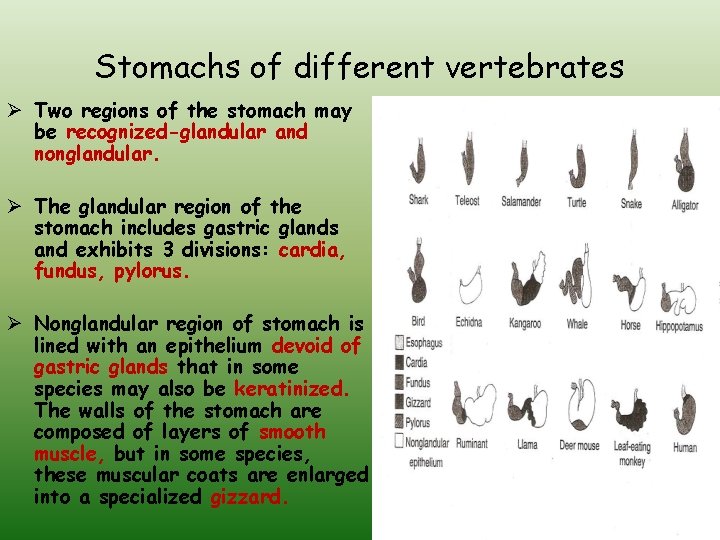

Stomachs of different vertebrates Ø Two regions of the stomach may be recognized-glandular and nonglandular. Ø The glandular region of the stomach includes gastric glands and exhibits 3 divisions: cardia, fundus, pylorus. Ø Nonglandular region of stomach is lined with an epithelium devoid of gastric glands that in some species may also be keratinized. The walls of the stomach are composed of layers of smooth muscle, but in some species, these muscular coats are enlarged into a specialized gizzard.

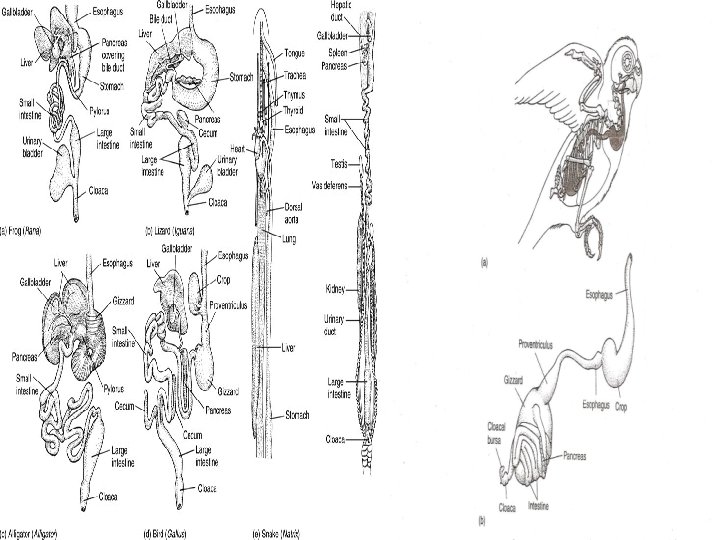

Stomach in amphibians Ø The stomach mucosa contains characteristic gastric glands, including fundic glands throughout most of the stomach and pyloric glands at its narrowed approach to the intestine. Ø The intestines are differentiated into a coiled small intestine, the first part of which is the duodenum and a short, straight large intestine that empties into a cloaca.

Stomach in reptiles • In many lizards, the stomach is heavy-walled and muscular. Crocodiles and alligators possess a gizzard, a region of the stomach endowed with an especially thick musculature that grinds food against ingested hard objects, usually small stones deliberately swallowed into the stomach. The thin-walled glandular region of the crocodilian stomach lies in front of the gizzard where gastric juices are added. • A distinct large intestine is usually present in reptiles. In some herbivorous lizards, a cecum is present between the small and large intestines. The cloaca is partially differentiated into the coprodaeum, a chamber into which the large intestine empties, and the urodaeum, a chamber into which the urinogenital system empties.

Digestive system in birds • In birds, the esophagus produces an inflated crop, in which food is held temporarily before proceeding along the digestive tract or regurgitated as a meal for nestlings. • In pigeons, the crop secretes a nutritional fluid called “milk” which is fed to the young for several days after hatching. The esophagus joins the thin-walled glandular section of the stomach, the proventriculus, which is connected to the posterior gizzard. The proventriculus secretes gastric juice to help digest the bolus, and the gizzard together with selected pieces of hard grit and pebbles, grinds large food into smaller pieces. • The long, coiled small intestine consists of a duodenum and ileum. A short, straight large intestine empties into the cloaca. In many species, one or several ceca can sprout from the intestine, usually near the junction of large and small intestines.

Digestive system in mammals Ø In mammals, the esophagus usually lacks a crop, and the stomach shows no tendency to form a gizzard. Ø In some cetaceans, the stomach or esophagus may expand into a pouch that apparently serves, like an avian crop to store food temporarily although some gastric digestion may begin as well in this pouch. Ø The mammalian small intestine is long and coiled and usually can be differentiated histologically into duodenum, jejunum and ileum. The large intestine is often long, although not as long as the small intestine and ends in the rectum. Ø In herbivores, a cecum is usually present at the junction between large and small intestines. In humans, this much reduced cecum is called the appendix, or more specifically the vermiform appendix. Ø In monotremes and a few marsupials, the large intestine terminates in the cloaca. Ø In placental mammals, it opens directly to the outside through the anal sphincter.

Digestive system in ruminants • In ruminants and camels, stomach has 4 chambers- rumen, reticulum and omasum (arise from esophagus) and abomasum (actual derivative of the stomach). • Large rumen receives the food after it is clipped by teeth and swallowed. Reticulum is a small accessory chamber with a honeycombed texture. Like the first two chambers, the omasum is lined with esophageal epithelium, although it is folded into overlapping leaves. The three types of mucosa distinctive of the mammalian stomach (cardia, fundus, pylorus) are found only in the abomasum, the presumably “true” stomach. • In many herbivores, digestion of plant cellulose is enhanced by a cecum situated between small and large intestines. The cecum contains additional microorganisms effective in cellulose digestion and provides an expanded region prolonging the time available for digestion.

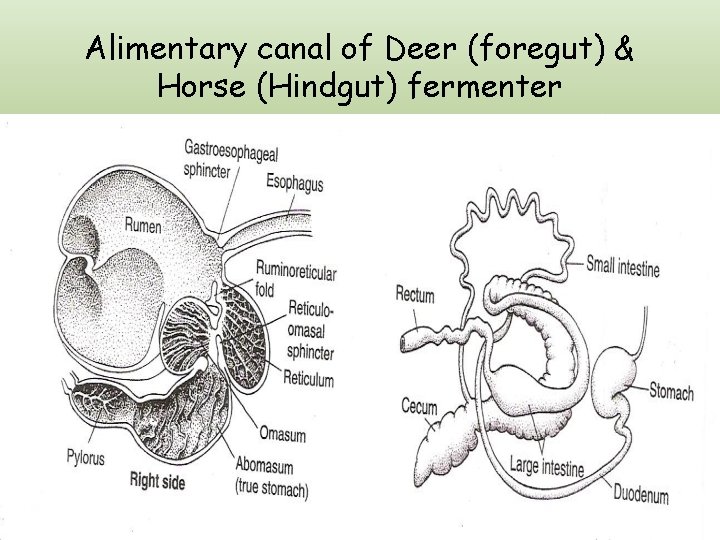

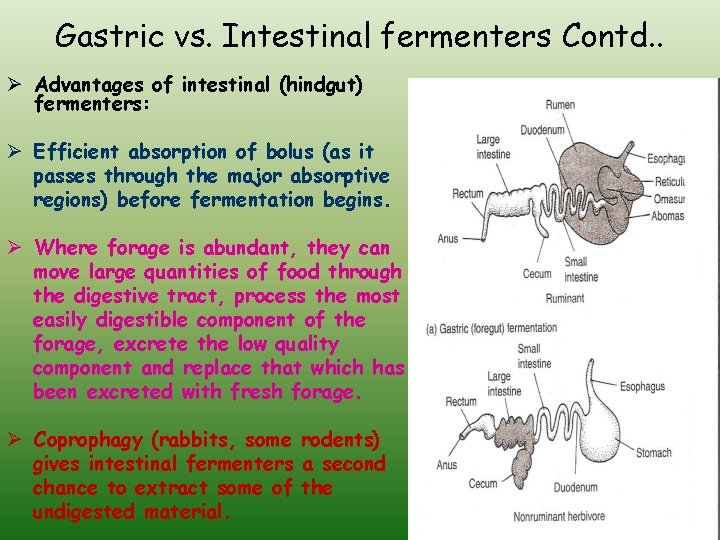

Alimentary canal of Deer (foregut) & Horse (Hindgut) fermenter

Function: Absorption • Absorption of food begins in the stomach. Water, salts and simple sugars often cross the mucosa and are absorbed in blood capillaries. However, in most vertebrates, the end products of digestion are usually formed and absorbed in the intestine. • Presence of spiral valve, long intestines in herbivores prolong the time food takes to traverse the intestines and allow microbial fermentation to digest cellulose more completely. • Appearance of a long, distinct large intestine in terrestrial vertebrates correlates with greater requirements to conserve water. • The mucosa of the large intestine contains mainly mucous glands so that digestion is brought about by enzymes the digesta carry down from the small intestine and by action of resident microorganisms. • The large intestine retains digesta so that the electrolytes and water secreted in the upper digestive tract can be resorbed by the body.

Function: Absorption Contd. . • In lower vertebrates, the large intestine resorbs electrolytes and water produced by the kidneys. The kidneys of amphibians, reptiles and birds are limited in their ability to concentrate urine. Much of the urinary sodium and water are resorbed in the cloaca into which ducts from the kidneys empty. • In addition, retrograde peristaltic waves can reflux material from the cloaca back into the large intestine and ceca, providing a further opportunity to resorb these by-products.

Function: Absorption Contd. . Ø Retrograde peristalsis essentially prolongs the time digesta spend in the digestive tract. Ø In some warblers, retrograde peristalsis forces intestinal contents back into the gizzard. This seems especially characteristic of birds feeding on fruits with waxy coatings of saturated fats. Ø When the waxy digesta reach the duodenum, high levels of bile salts and pancreatic lipases are added. This mix is refluxed back into the efficient emulsification mill, the gizzard, for further processing. Ø Saturated fatty acids in the wax can be more efficiently broken down and assimilated.

Function: Mechanical breakdown of food Ø Involves mastication or chewing; muscle and skin, are cut by the blades of specialised carnassial teeth- of carnivores, for example. Ø Grasses and other plant material, are best broken down by grinding. The molar teeth of ungulates, subungulates and rodents are corrugated on their working surfaces. As the jaws move from side to side, these tooth surfaces slide past one another to tear plant fibers. Ø Chewing mechanically shreds tough plant fibers and breaks down cell walls, thereby exposing the cytoplasm within to digestive enzymes. Ø Nuts and seeds yield best to compression. Molar teeth that roll over each other pulverize this type of food into smaller pieces. Ø Muscularized gizzard works the swallowed stones against the bolus and grinds it into smaller pieces. Eg- birds.

Function: Chemical breakdown of food Ø Enzymes from the liver, pancreas and mucosal wall of the intestine all digest food as it passes through the digestive tract. In some species, chemical digestion begins in the mouth and usually involves amylase digestion of carbohydrates. Ø The end products of digestion are amino acids, sugars and fatty acids as well as vitamins and trace minerals indispensable to fuel the organism for growth and maintenance. Ø Proteases digest proteins by splitting their peptide bonds. Ø Fat digestion begins with emulsification of large globules into many smaller ones. Bile, produced by the liver, is one of the body’s major emulsifying agents. Emulsification increases the surface area of fats exposed to the lipases.

Function: Chemical breakdown of food Contd. . Ø Digestion of carbohydrates produces simple sugars. One of the most important carbohydrates is cellulose, a structural component of all plants. Cellulose is insoluble and extremely resistant to chemical attack. Ø Many herbivores depend on it as a major energy source, yet surprisingly, no vertebrate is able to manufacture cellulases, the enzymes that can digest cellulose. Symbiotic microorganisms, bacteria and protozoans, that live in the digestive tract of the host vertebrate produce cellulases to break down cellulose from ingested plants. Ø The process of breaking down cellulose is known as fermentation, which yields organic acids that are absorbed and utilized in oxidative metabolism. CO 2 and CH 4 are unusable byproducts released by belching.

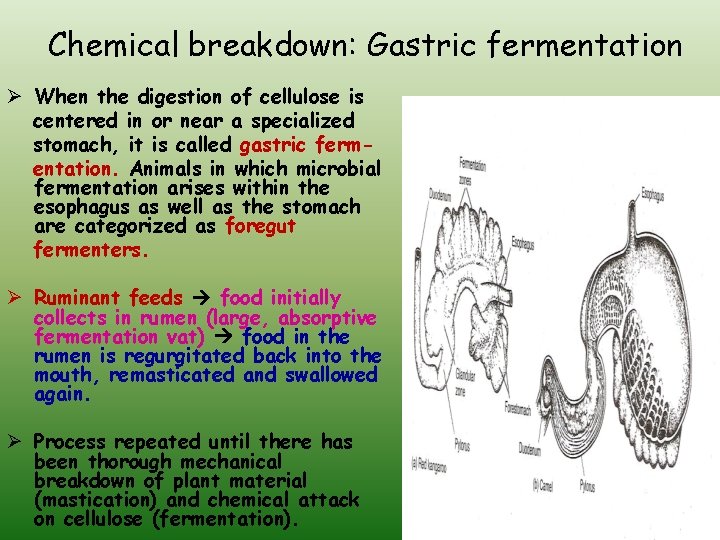

Chemical breakdown: Gastric fermentation Ø When the digestion of cellulose is centered in or near a specialized stomach, it is called gastric fermentation. Animals in which microbial fermentation arises within the esophagus as well as the stomach are categorized as foregut fermenters. Ø Ruminant feeds food initially collects in rumen (large, absorptive fermentation vat) food in the rumen is regurgitated back into the mouth, remasticated and swallowed again. Ø Process repeated until there has been thorough mechanical breakdown of plant material (mastication) and chemical attack on cellulose (fermentation).

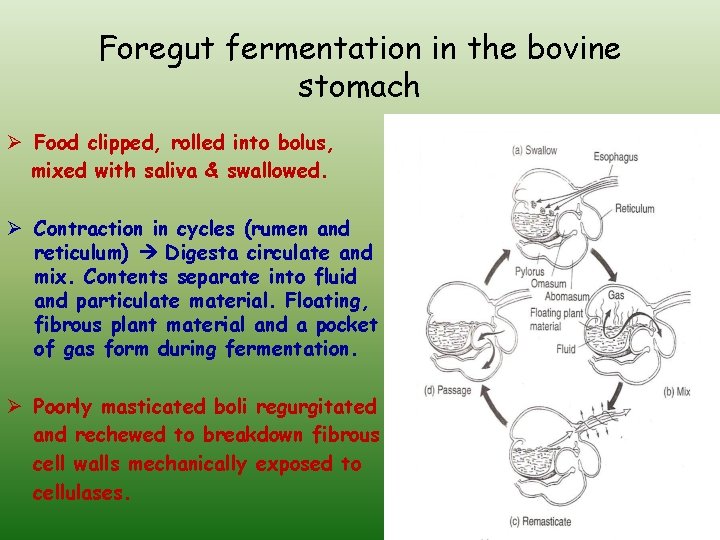

Foregut fermentation in the bovine stomach Ø Food clipped, rolled into bolus, mixed with saliva & swallowed. Ø Contraction in cycles (rumen and reticulum) Digesta circulate and mix. Contents separate into fluid and particulate material. Floating, fibrous plant material and a pocket of gas form during fermentation. Ø Poorly masticated boli regurgitated and rechewed to breakdown fibrous cell walls mechanically exposed to cellulases.

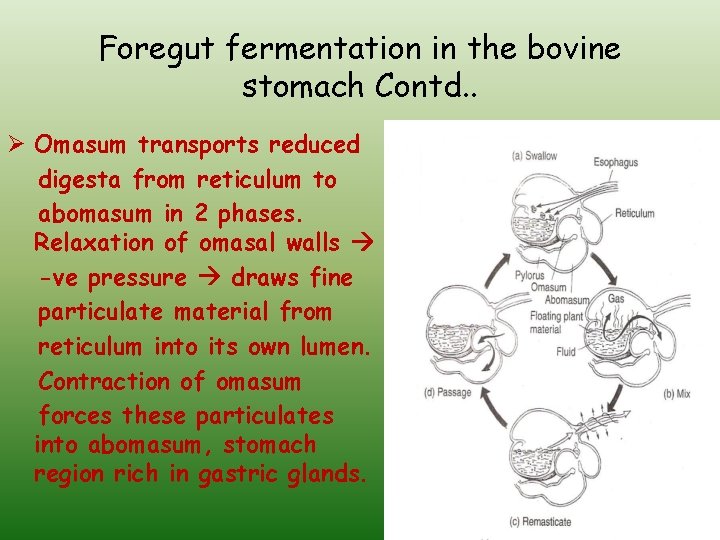

Foregut fermentation in the bovine stomach Contd. . Ø Omasum transports reduced digesta from reticulum to abomasum in 2 phases. Relaxation of omasal walls -ve pressure draws fine particulate material from reticulum into its own lumen. Contraction of omasum forces these particulates into abomasum, stomach region rich in gastric glands.

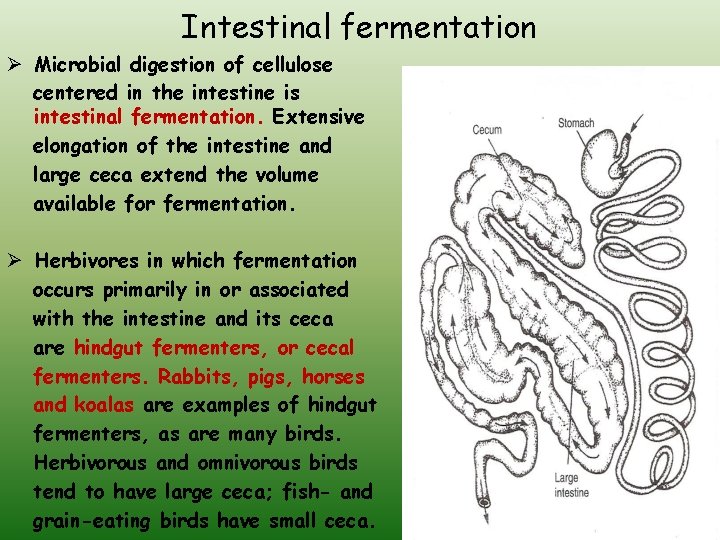

Intestinal fermentation Ø Microbial digestion of cellulose centered in the intestine is intestinal fermentation. Extensive elongation of the intestine and large ceca extend the volume available for fermentation. Ø Herbivores in which fermentation occurs primarily in or associated with the intestine and its ceca are hindgut fermenters, or cecal fermenters. Rabbits, pigs, horses and koalas are examples of hindgut fermenters, as are many birds. Herbivorous and omnivorous birds tend to have large ceca; fish- and grain-eating birds have small ceca.

Gastric vs. Intestinal fermenters Ø In both gastric and intestinal fermenters, microorganisms of the digestive tract release enzymes that digest the plant cellulose. Ø Advantages of gastric (foregut) fermenters: *Fermentation takes place in the anterior part of the alimentary canal, yielding end products of digestion early in the digestive process so they are ready for uptake next in the intestine. *Ruminant system allows rechewing and more complete mechanical breakdown of the cell walls. By shuttling food between mouth and rumen via the esophagus, the ruminant can keep grinding away at plant fibers. *Ruminants turns much of the nitrogen, which in most vertebrates is a waste product, into a resource. This is particularly useful in those that consume low-protein diets.

Gastric vs. Intestinal fermenters Contd. . • Advantages of gastric (foregut) fermenters: *Large storage capacity of the rumen means that the animal can quickly gather a large meal in an exposed site, and then retreat to a safe spot in order to digest it. *Gastric fermenters are also able to turn urea, another waste product, into a resource. For example, in camel urea reenters the rumen, where it is broken down into carbon dioxide and ammonia. Microbes take up this ammonia and combine it with other organic carbon compounds to make cell proteins. *Microbes also aid in the breakdown of cellulose, a carbohydrate in the cell walls of plants. Cellulose fermentation produces carbon dioxide, water and volatile fatty acids.

Gastric vs. Intestinal fermenters Contd. . Ø Advantages of intestinal (hindgut) fermenters: Ø Efficient absorption of bolus (as it passes through the major absorptive regions) before fermentation begins. Ø Where forage is abundant, they can move large quantities of food through the digestive tract, process the most easily digestible component of the forage, excrete the low quality component and replace that which has been excreted with fresh forage. Ø Coprophagy (rabbits, some rodents) gives intestinal fermenters a second chance to extract some of the undigested material.

- Slides: 25