COMP 412 FALL 2010 Global Register Allocation via

COMP 412 FALL 2010 Global Register Allocation via Graph Coloring Comp 412 This lecture focuses on the Chaitin. Briggs approach, which Ea. C calls the bottom-up global algorithm. Copyright 2010, Keith D. Cooper & Linda Torczon, all rights reserved. Students enrolled in Comp 412 at Rice University have explicit permission to make copies of these materials for their personal use. Faculty from other educational institutions may use these materials for nonprofit educational purposes, provided this copyright notice is preserved.

Notes on the Final Exam • Closed-notes, closed-book exam • Exam available Wednesday. • Three hour time limit — I aimed for a two-hour exam, but I don’t want you to feel time pressure. You may take one break of up to fifteen minutes apiece. • You are responsible for the entire course — Exam focuses primarily on material since the midterm — Chapters 5, 6, 7, 8, 9. 1, 9. 2, 11, 12, & 13 — All the lecture notes • Return the exam to DH 3080 (Penny Anderson’s office) by • 5 PM on the last day of exams – December 15, 2010 If you must leave, you can email me a Word file or a PDF document. Comp 412, Fall 2010 1

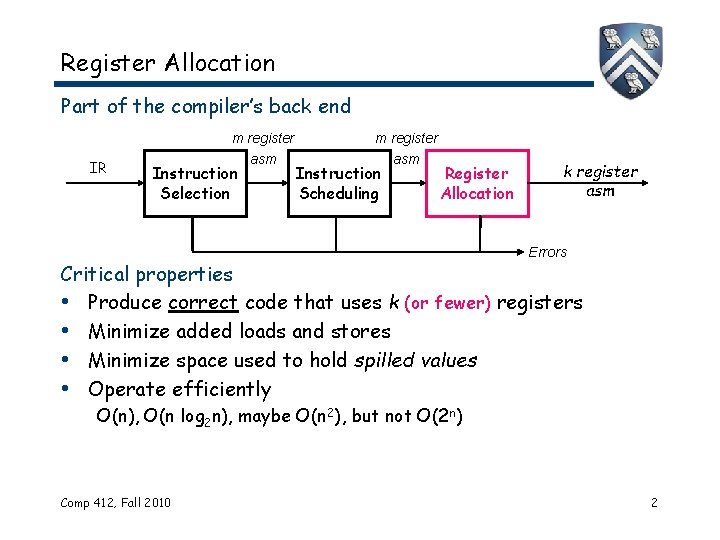

Register Allocation Part of the compiler’s back end m register IR Instruction Selection asm m register Instruction Scheduling asm Register Allocation k register asm Errors Critical properties • Produce correct code that uses k (or fewer) registers • Minimize added loads and stores • Minimize space used to hold spilled values • Operate efficiently O(n), O(n log 2 n), maybe O(n 2), but not O(2 n) Comp 412, Fall 2010 2

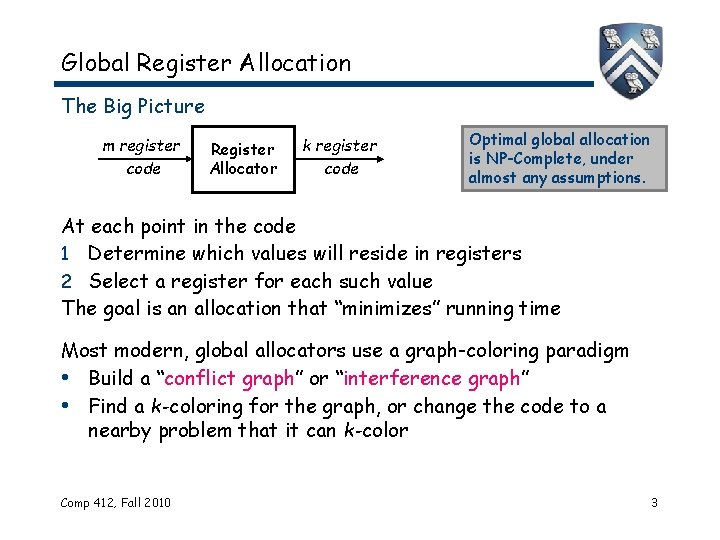

Global Register Allocation The Big Picture m register code Register Allocator k register code Optimal global allocation is NP-Complete, under almost any assumptions. At each point in the code 1 Determine which values will reside in registers 2 Select a register for each such value The goal is an allocation that “minimizes” running time Most modern, global allocators use a graph-coloring paradigm • Build a “conflict graph” or “interference graph” • Find a k-coloring for the graph, or change the code to a nearby problem that it can k-color Comp 412, Fall 2010 3

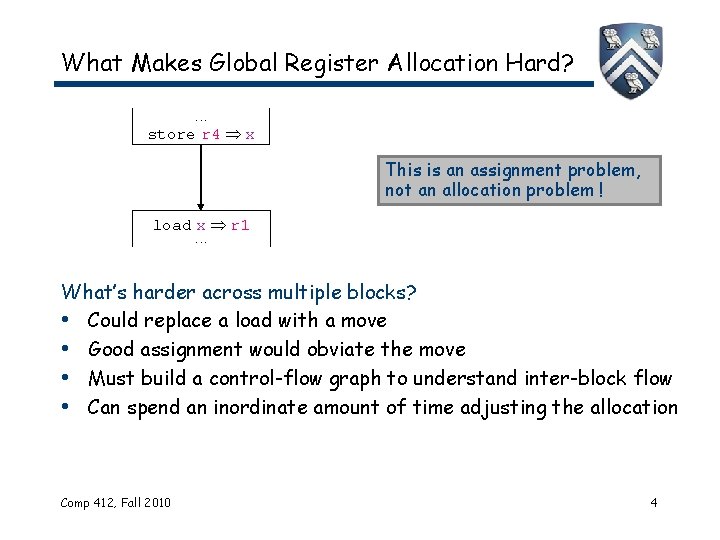

What Makes Global Register Allocation Hard? . . . store r 4 x This is an assignment problem, not an allocation problem ! load x r 1. . . What’s harder across multiple blocks? • Could replace a load with a move • Good assignment would obviate the move • Must build a control-flow graph to understand inter-block flow • Can spend an inordinate amount of time adjusting the allocation Comp 412, Fall 2010 4

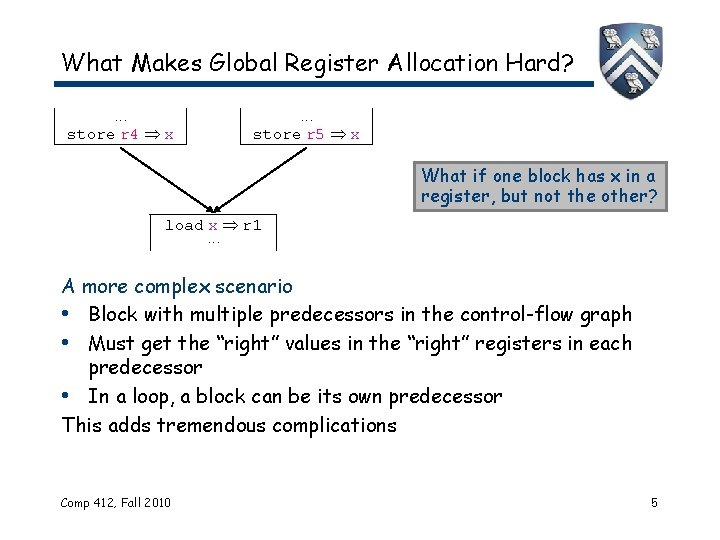

What Makes Global Register Allocation Hard? . . . store r 4 x . . . store r 5 x What if one block has x in a register, but not the other? load x r 1. . . A more complex scenario • Block with multiple predecessors in the control-flow graph • Must get the “right” values in the “right” registers in each predecessor • In a loop, a block can be its own predecessor This adds tremendous complications Comp 412, Fall 2010 5

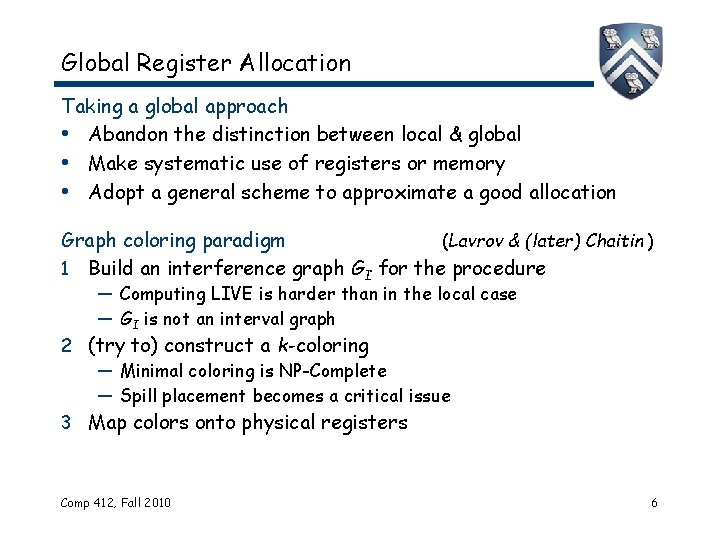

Global Register Allocation Taking a global approach • Abandon the distinction between local & global • Make systematic use of registers or memory • Adopt a general scheme to approximate a good allocation Graph coloring paradigm (Lavrov & (later) Chaitin ) 1 Build an interference graph GI for the procedure — Computing LIVE is harder than in the local case — GI is not an interval graph 2 (try to) construct a k-coloring — Minimal coloring is NP-Complete — Spill placement becomes a critical issue 3 Map colors onto physical registers Comp 412, Fall 2010 6

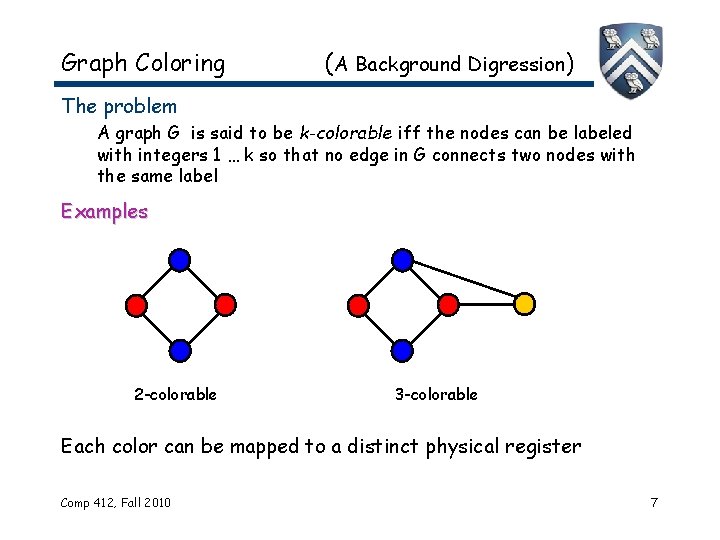

Graph Coloring (A Background Digression) The problem A graph G is said to be k-colorable iff the nodes can be labeled with integers 1 … k so that no edge in G connects two nodes with the same label Examples 2 -colorable 3 -colorable Each color can be mapped to a distinct physical register Comp 412, Fall 2010 7

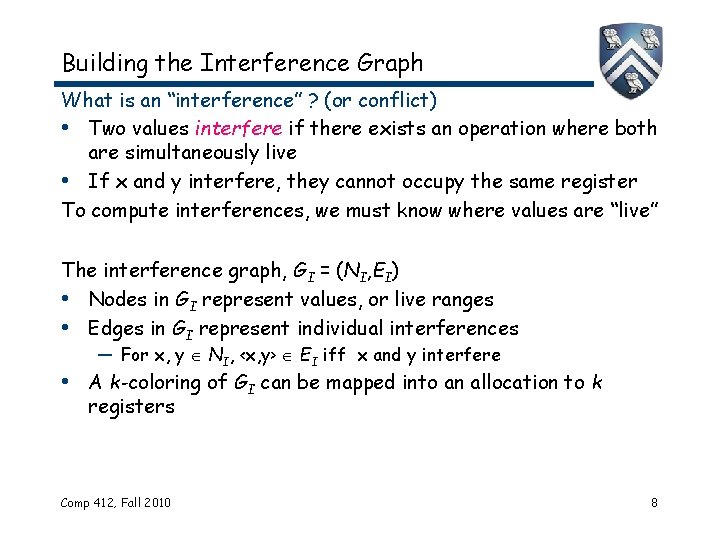

Building the Interference Graph What is an “interference” ? (or conflict) • Two values interfere if there exists an operation where both are simultaneously live • If x and y interfere, they cannot occupy the same register To compute interferences, we must know where values are “live” The interference graph, GI = (NI, EI) • Nodes in GI represent values, or live ranges • Edges in GI represent individual interferences — For x, y NI, <x, y> EI iff x and y interfere • A k-coloring of GI can be mapped into an allocation to k registers Comp 412, Fall 2010 8

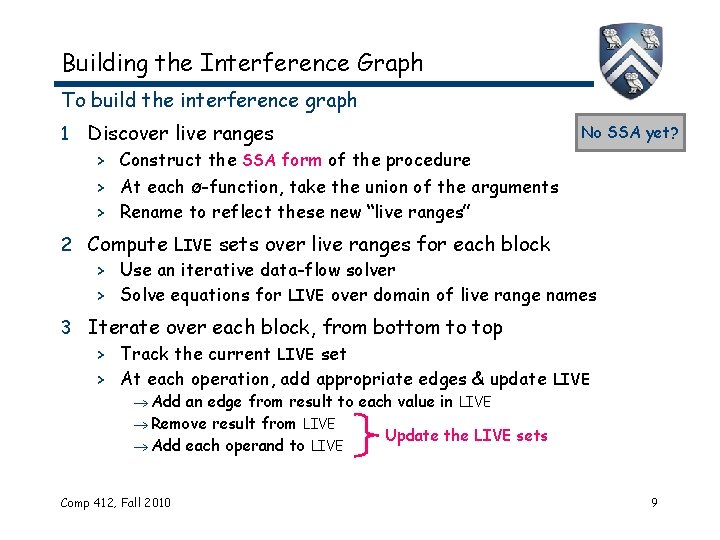

Building the Interference Graph To build the interference graph 1 Discover live ranges No SSA yet? > Construct the SSA form of the procedure > At each ø-function, take the union of the arguments > Rename to reflect these new “live ranges” 2 Compute LIVE sets over live ranges for each block > Use an iterative data-flow solver > Solve equations for LIVE over domain of live range names 3 Iterate over each block, from bottom to top > Track the current LIVE set > At each operation, add appropriate edges & update LIVE Add an edge from result to each value in LIVE Remove result from LIVE Update the LIVE sets Add each operand to LIVE Comp 412, Fall 2010 9

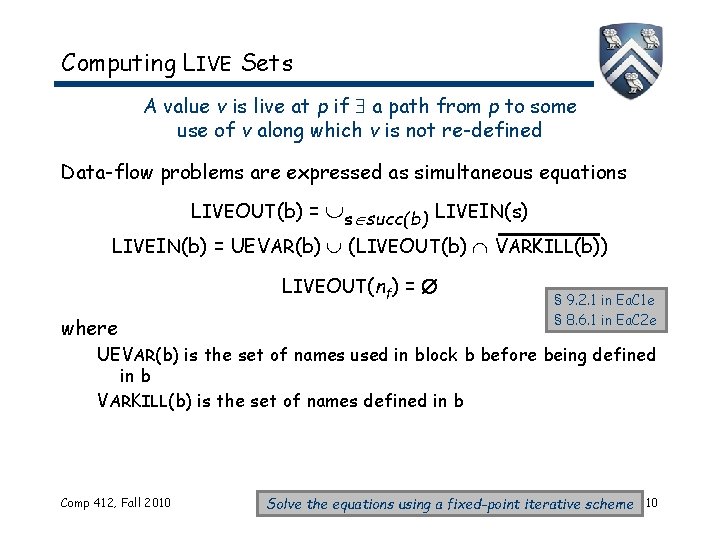

Computing LIVE Sets A value v is live at p if a path from p to some use of v along which v is not re-defined Data-flow problems are expressed as simultaneous equations LIVEOUT(b) = s succ(b) LIVEIN(s) LIVEIN(b) = UEVAR(b) (LIVEOUT(b) VARKILL(b)) LIVEOUT(nf) = where § 9. 2. 1 in Ea. C 1 e § 8. 6. 1 in Ea. C 2 e UEVAR(b) is the set of names used in block b before being defined in b VARKILL(b) is the set of names defined in b Comp 412, Fall 2010 Solve the equations using a fixed-point iterative scheme 10

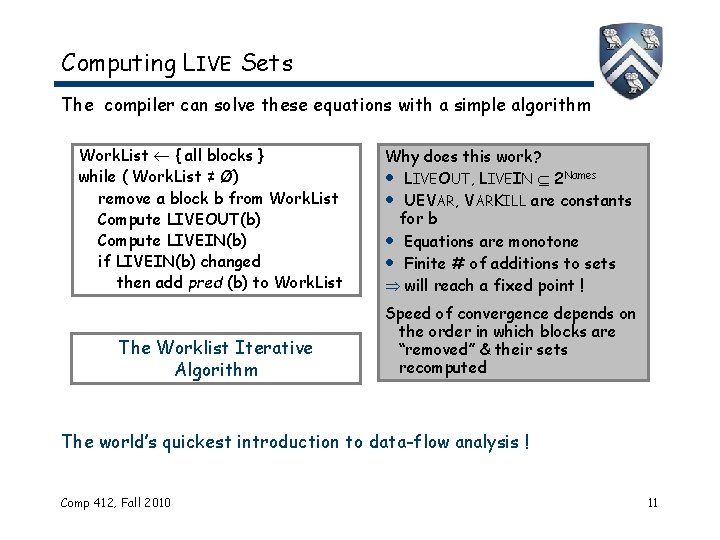

Computing LIVE Sets The compiler can solve these equations with a simple algorithm Work. List { all blocks } while ( Work. List ≠ Ø) remove a block b from Work. List Compute LIVEOUT(b) Compute LIVEIN(b) if LIVEIN(b) changed then add pred (b) to Work. List Why does this work? LIVEOUT, LIVEIN 2 Names UEVAR, VARKILL are constants for b Equations are monotone Finite # of additions to sets will reach a fixed point ! The Worklist Iterative Algorithm Speed of convergence depends on the order in which blocks are “removed” & their sets recomputed The world’s quickest introduction to data-flow analysis ! Comp 412, Fall 2010 11

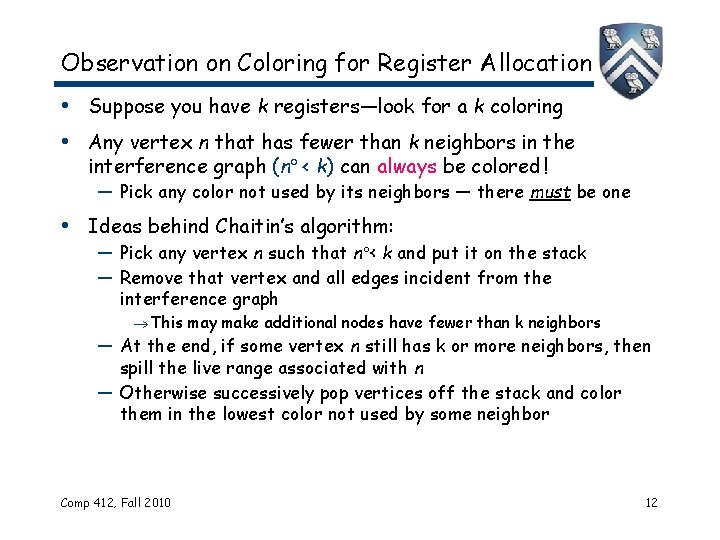

Observation on Coloring for Register Allocation • Suppose you have k registers—look for a k coloring • Any vertex n that has fewer than k neighbors in the interference graph (n < k) can always be colored ! — Pick any color not used by its neighbors — there must be one • Ideas behind Chaitin’s algorithm: — Pick any vertex n such that n < k and put it on the stack — Remove that vertex and all edges incident from the interference graph This may make additional nodes have fewer than k neighbors — At the end, if some vertex n still has k or more neighbors, then spill the live range associated with n — Otherwise successively pop vertices off the stack and color them in the lowest color not used by some neighbor Comp 412, Fall 2010 12

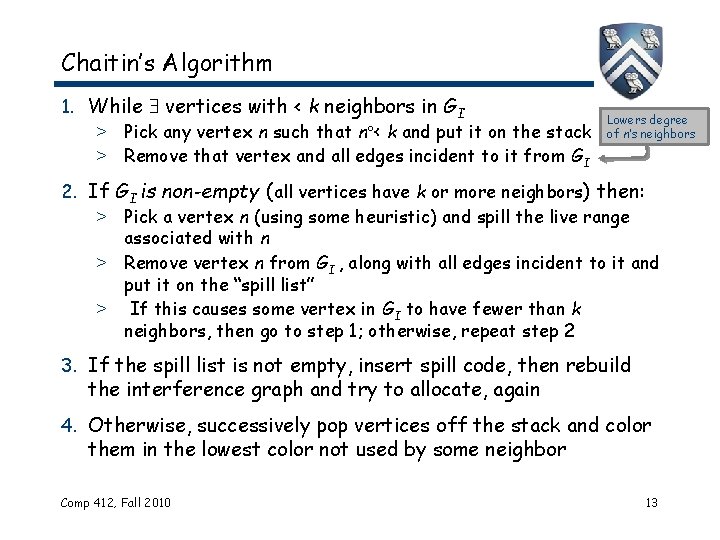

Chaitin’s Algorithm 1. While vertices with < k neighbors in GI > Pick any vertex n such that n < k and put it on the stack > Remove that vertex and all edges incident to it from GI Lowers degree of n’s neighbors 2. If GI is non-empty (all vertices have k or more neighbors) then: > Pick a vertex n (using some heuristic) and spill the live range associated with n > Remove vertex n from GI , along with all edges incident to it and put it on the “spill list” > If this causes some vertex in GI to have fewer than k neighbors, then go to step 1; otherwise, repeat step 2 3. If the spill list is not empty, insert spill code, then rebuild the interference graph and try to allocate, again 4. Otherwise, successively pop vertices off the stack and color them in the lowest color not used by some neighbor Comp 412, Fall 2010 13

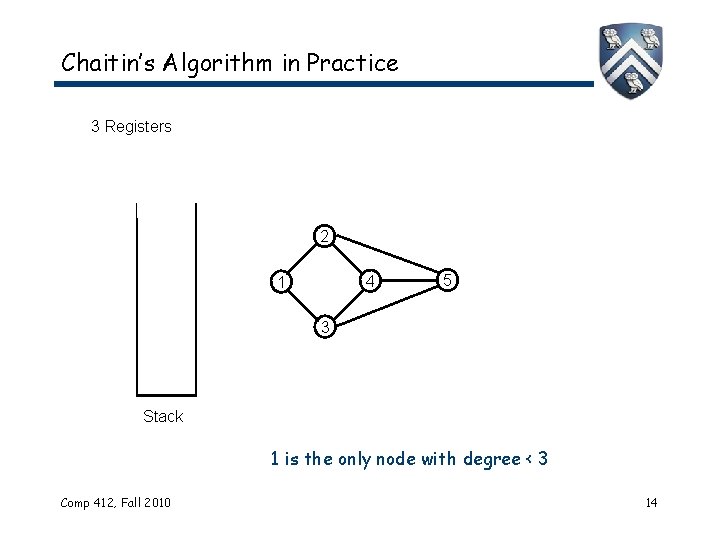

Chaitin’s Algorithm in Practice 3 Registers 2 4 1 5 3 Stack 1 is the only node with degree < 3 Comp 412, Fall 2010 14

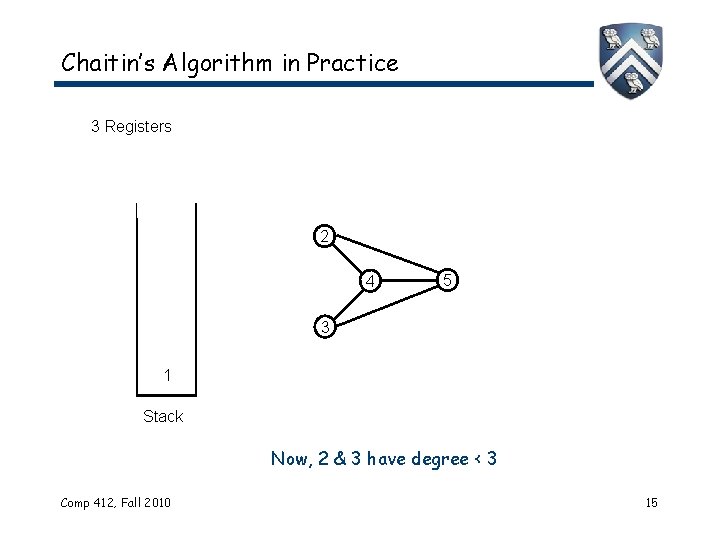

Chaitin’s Algorithm in Practice 3 Registers 2 4 5 3 1 Stack Now, 2 & 3 have degree < 3 Comp 412, Fall 2010 15

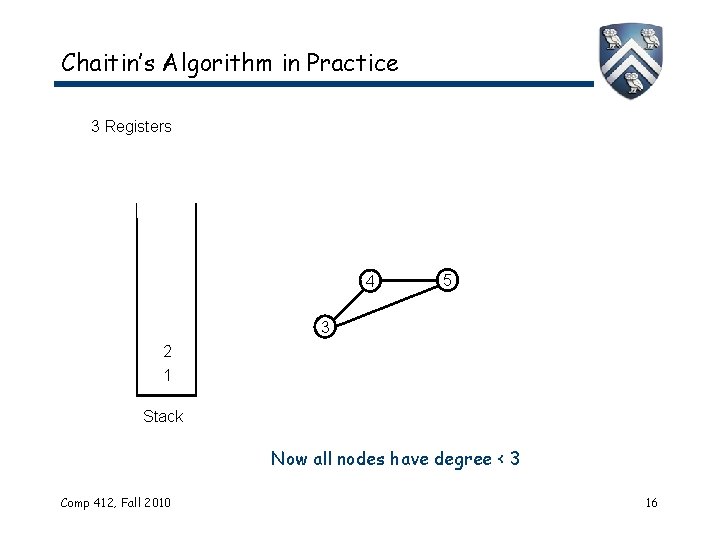

Chaitin’s Algorithm in Practice 3 Registers 4 5 3 2 1 Stack Now all nodes have degree < 3 Comp 412, Fall 2010 16

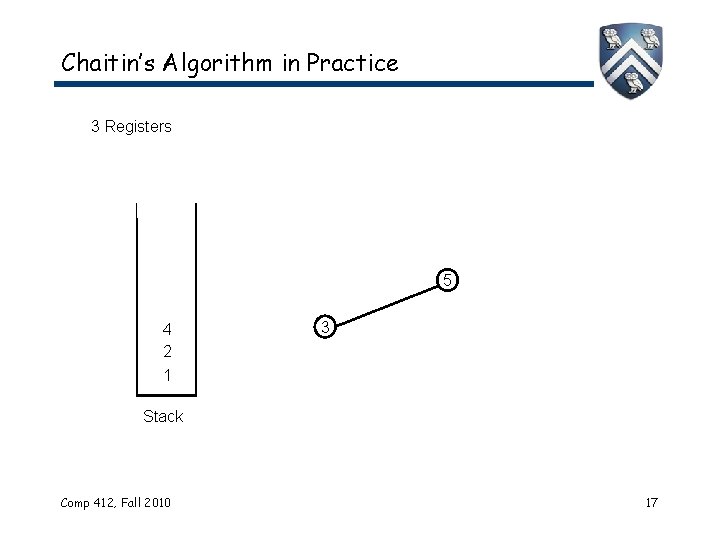

Chaitin’s Algorithm in Practice 3 Registers 5 4 2 1 3 Stack Comp 412, Fall 2010 17

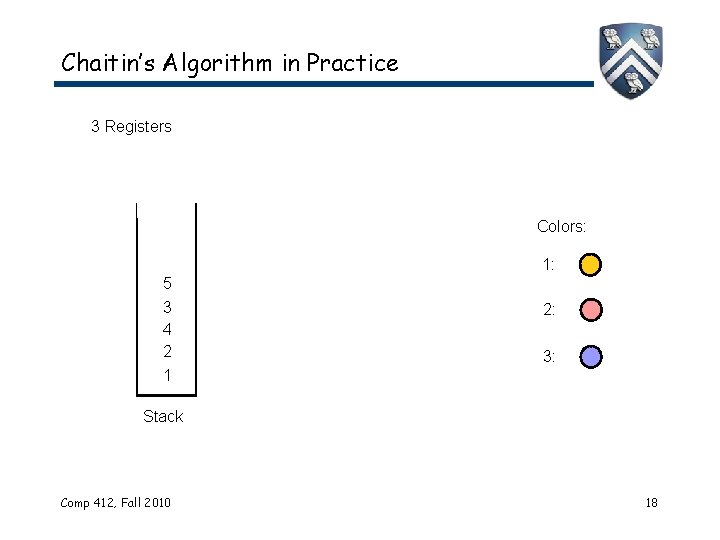

Chaitin’s Algorithm in Practice 3 Registers Colors: 1: 5 3 4 2 1 2: 3: Stack Comp 412, Fall 2010 18

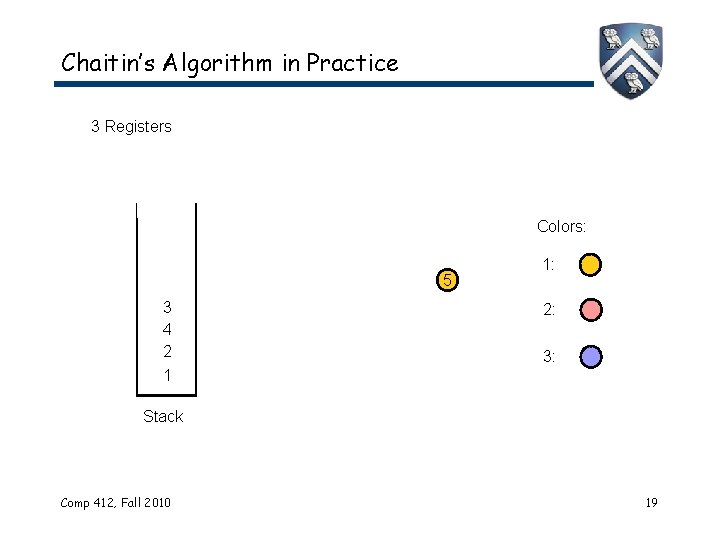

Chaitin’s Algorithm in Practice 3 Registers Colors: 5 3 4 2 1 1: 2: 3: Stack Comp 412, Fall 2010 19

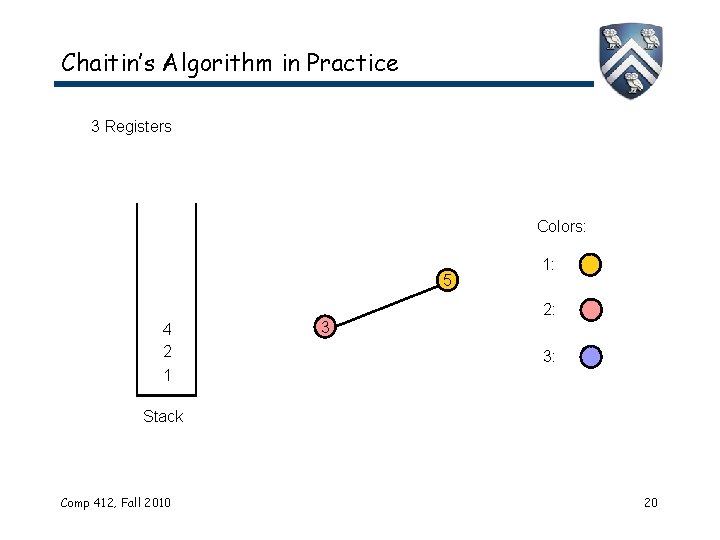

Chaitin’s Algorithm in Practice 3 Registers Colors: 5 4 2 1 3 1: 2: 3: Stack Comp 412, Fall 2010 20

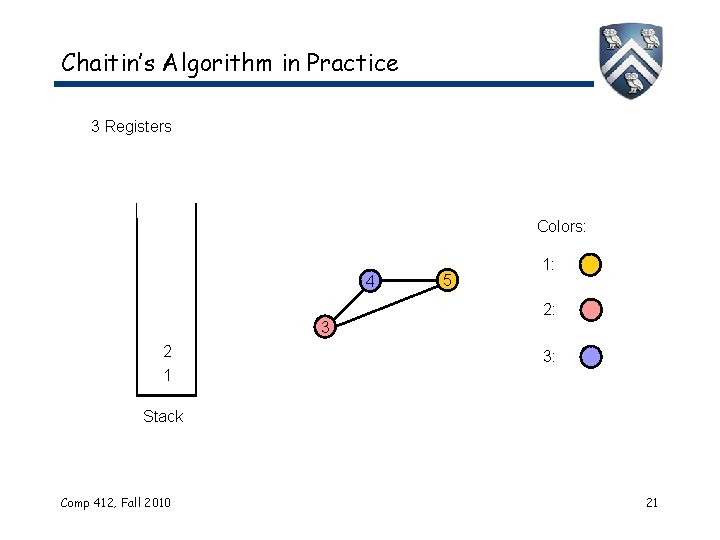

Chaitin’s Algorithm in Practice 3 Registers Colors: 4 3 2 1 5 1: 2: 3: Stack Comp 412, Fall 2010 21

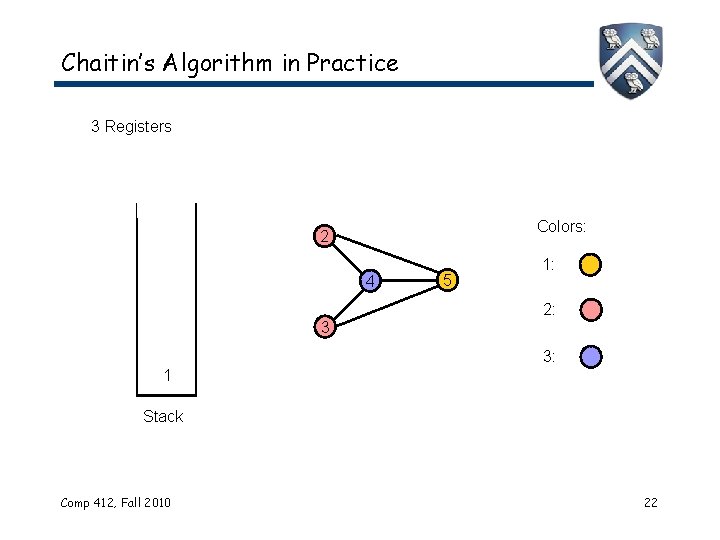

Chaitin’s Algorithm in Practice 3 Registers Colors: 2 4 3 5 1: 2: 3: 1 Stack Comp 412, Fall 2010 22

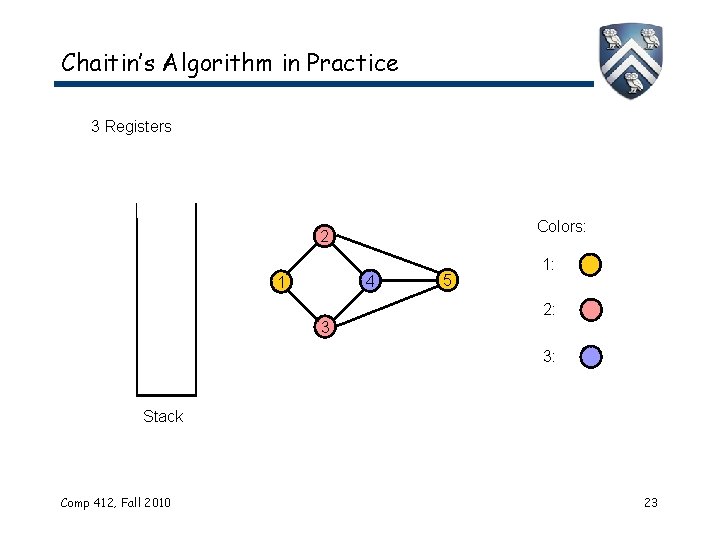

Chaitin’s Algorithm in Practice 3 Registers Colors: 2 4 1 3 5 1: 2: 3: Stack Comp 412, Fall 2010 23

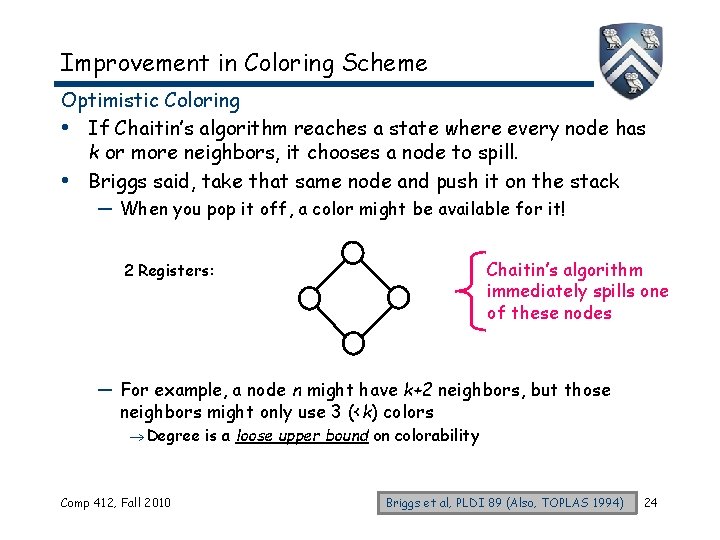

Improvement in Coloring Scheme Optimistic Coloring • If Chaitin’s algorithm reaches a state where every node has k or more neighbors, it chooses a node to spill. • Briggs said, take that same node and push it on the stack — When you pop it off, a color might be available for it! Chaitin’s algorithm immediately spills one of these nodes 2 Registers: — For example, a node n might have k+2 neighbors, but those neighbors might only use 3 (<k) colors Degree is a loose upper bound on colorability Comp 412, Fall 2010 Briggs et al, PLDI 89 (Also, TOPLAS 1994) 24

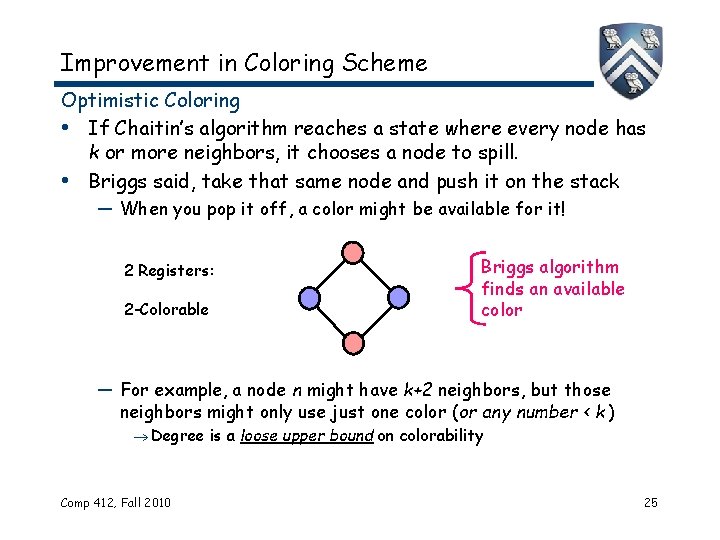

Improvement in Coloring Scheme Optimistic Coloring • If Chaitin’s algorithm reaches a state where every node has k or more neighbors, it chooses a node to spill. • Briggs said, take that same node and push it on the stack — When you pop it off, a color might be available for it! 2 Registers: 2 -Colorable Briggs algorithm finds an available color — For example, a node n might have k+2 neighbors, but those neighbors might only use just one color (or any number < k ) Degree is a loose upper bound on colorability Comp 412, Fall 2010 25

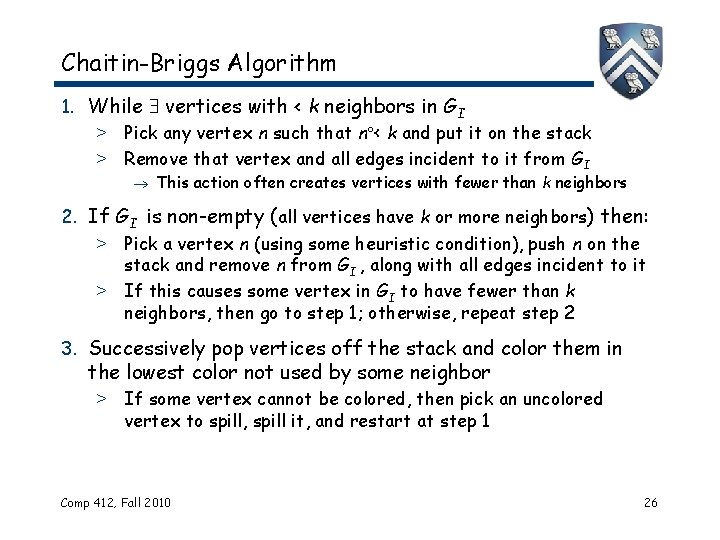

Chaitin-Briggs Algorithm 1. While vertices with < k neighbors in GI > Pick any vertex n such that n < k and put it on the stack > Remove that vertex and all edges incident to it from GI This action often creates vertices with fewer than k neighbors 2. If GI is non-empty (all vertices have k or more neighbors) then: > Pick a vertex n (using some heuristic condition), push n on the stack and remove n from GI , along with all edges incident to it > If this causes some vertex in GI to have fewer than k neighbors, then go to step 1; otherwise, repeat step 2 3. Successively pop vertices off the stack and color them in the lowest color not used by some neighbor > If some vertex cannot be colored, then pick an uncolored vertex to spill, spill it, and restart at step 1 Comp 412, Fall 2010 26

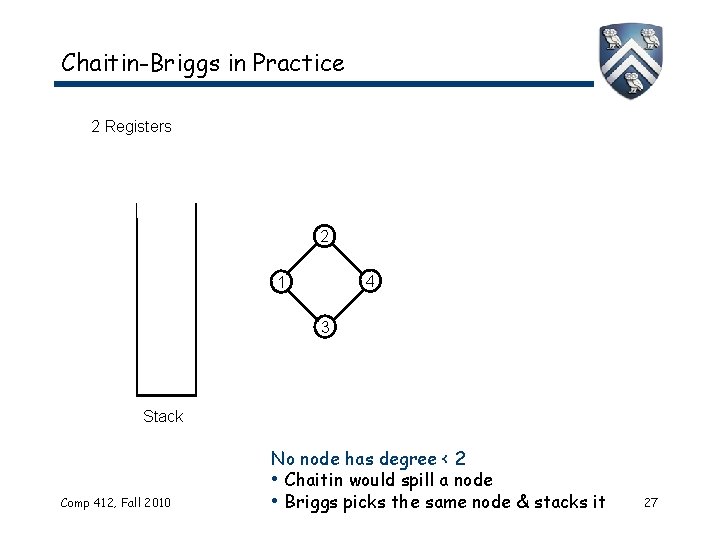

Chaitin-Briggs in Practice 2 Registers 2 4 1 3 Stack Comp 412, Fall 2010 No node has degree < 2 • Chaitin would spill a node • Briggs picks the same node & stacks it 27

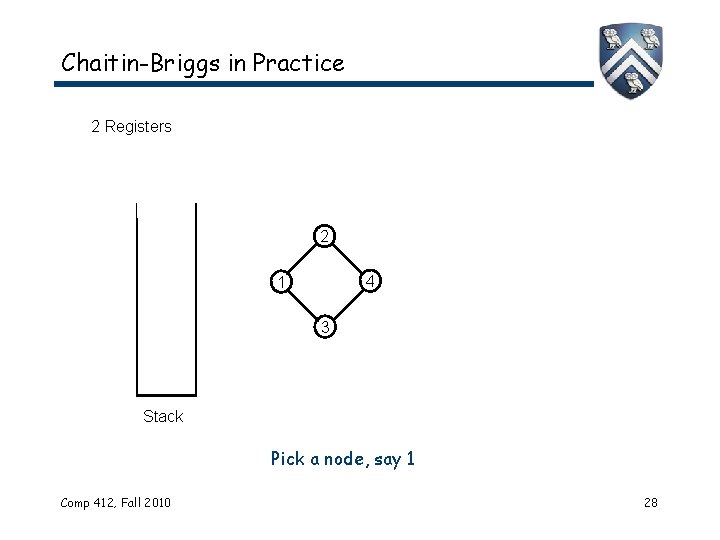

Chaitin-Briggs in Practice 2 Registers 2 4 1 3 Stack Pick a node, say 1 Comp 412, Fall 2010 28

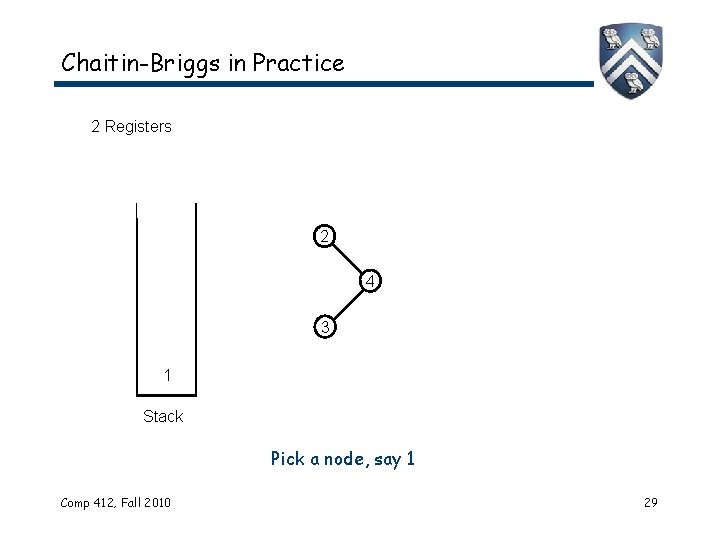

Chaitin-Briggs in Practice 2 Registers 2 4 3 1 Stack Pick a node, say 1 Comp 412, Fall 2010 29

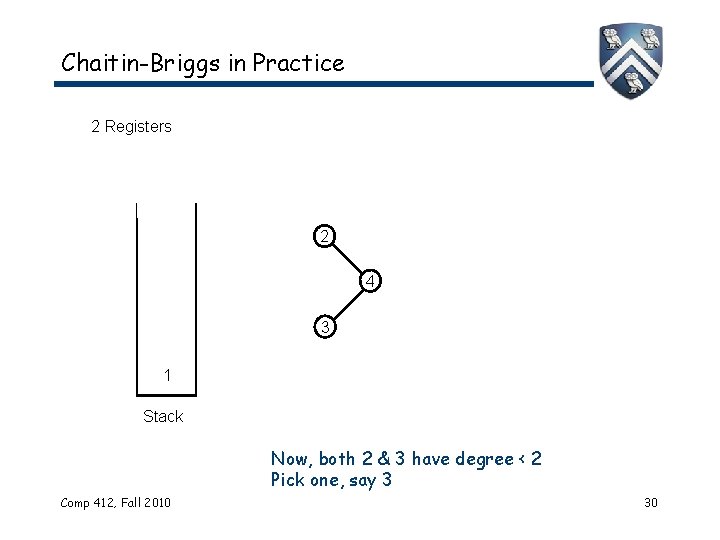

Chaitin-Briggs in Practice 2 Registers 2 4 3 1 Stack Now, both 2 & 3 have degree < 2 Pick one, say 3 Comp 412, Fall 2010 30

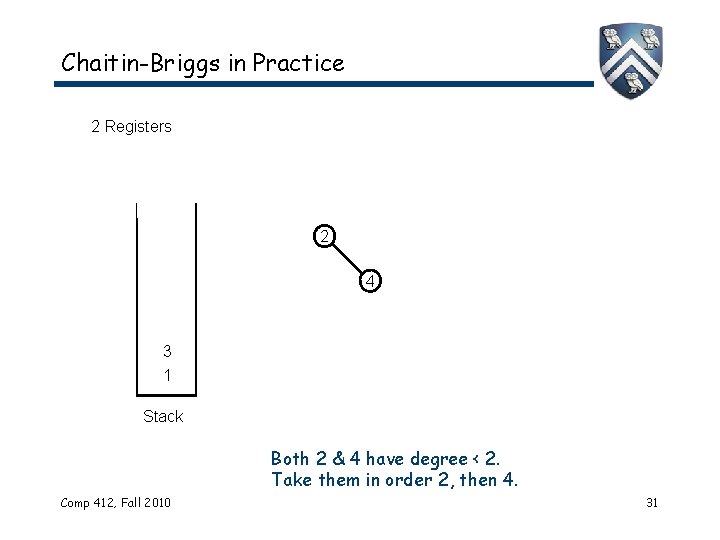

Chaitin-Briggs in Practice 2 Registers 2 4 3 1 Stack Both 2 & 4 have degree < 2. Take them in order 2, then 4. Comp 412, Fall 2010 31

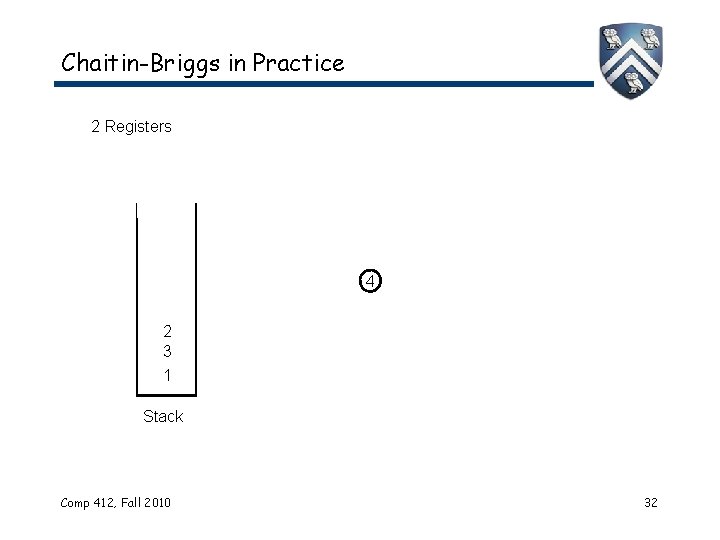

Chaitin-Briggs in Practice 2 Registers 4 2 3 1 Stack Comp 412, Fall 2010 32

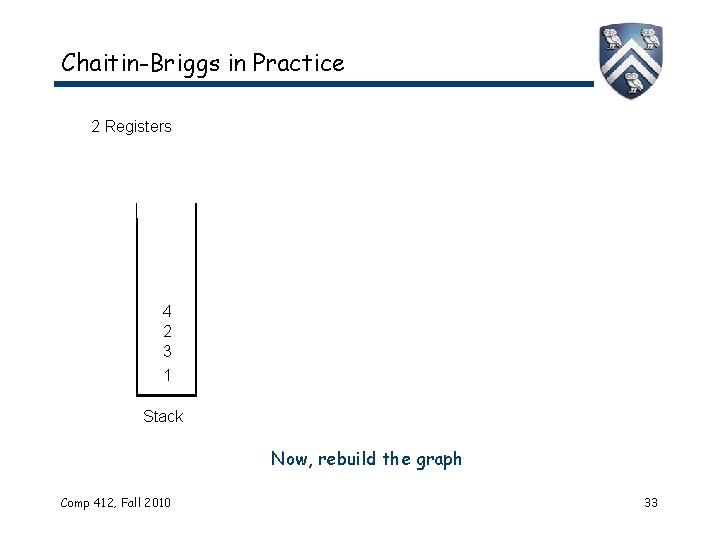

Chaitin-Briggs in Practice 2 Registers 4 2 3 1 Stack Now, rebuild the graph Comp 412, Fall 2010 33

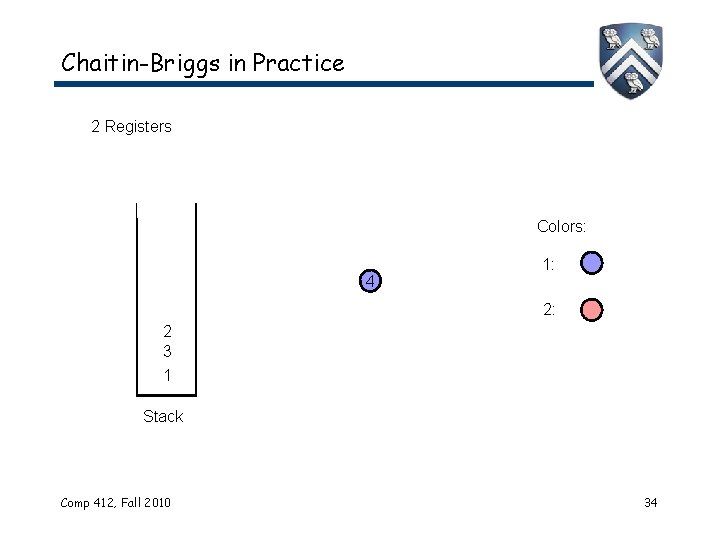

Chaitin-Briggs in Practice 2 Registers Colors: 4 1: 2: 2 3 1 Stack Comp 412, Fall 2010 34

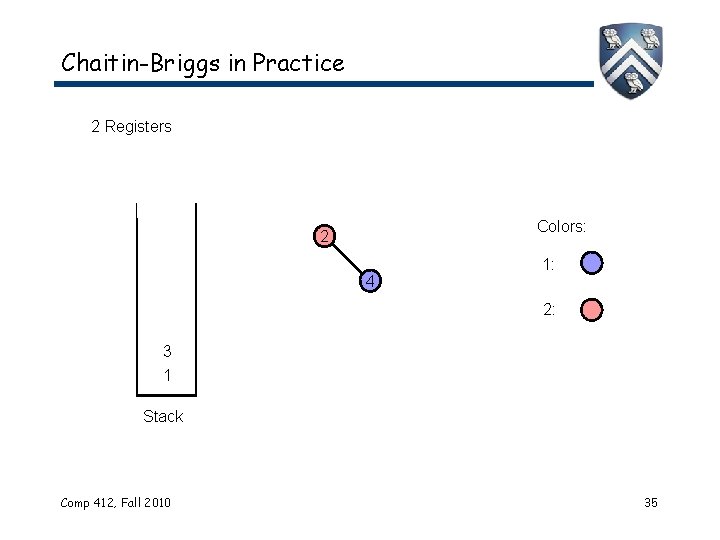

Chaitin-Briggs in Practice 2 Registers Colors: 2 4 1: 2: 3 1 Stack Comp 412, Fall 2010 35

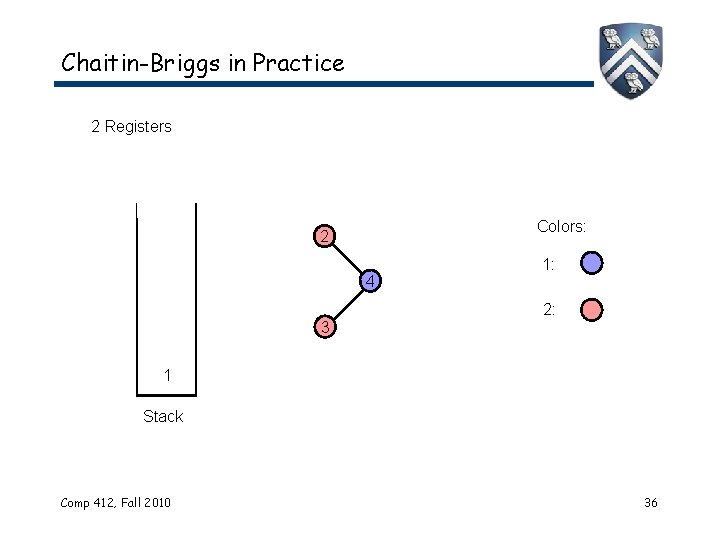

Chaitin-Briggs in Practice 2 Registers Colors: 2 4 3 1: 2: 1 Stack Comp 412, Fall 2010 36

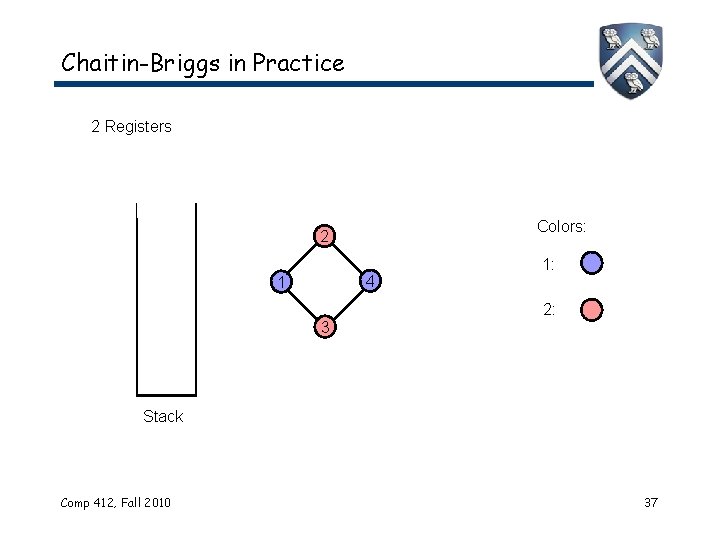

Chaitin-Briggs in Practice 2 Registers Colors: 2 4 1 3 1: 2: Stack Comp 412, Fall 2010 37

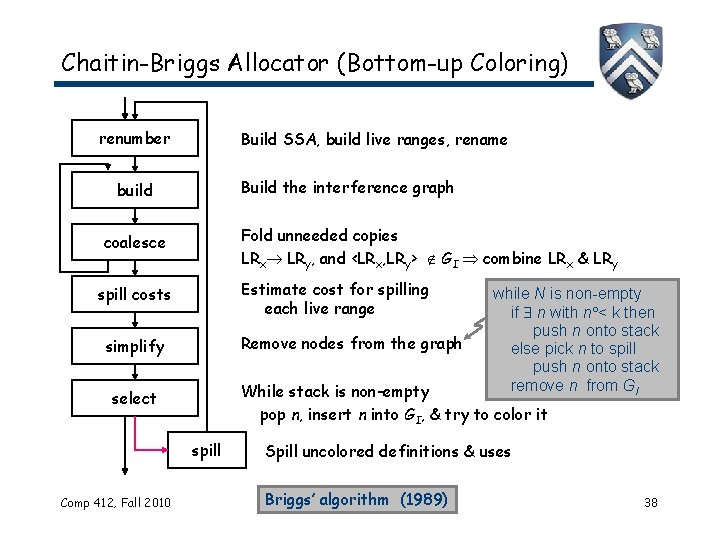

Chaitin-Briggs Allocator (Bottom-up Coloring) renumber Build SSA, build live ranges, rename Build the interference graph build Fold unneeded copies LRx LRy, and <LRx, LRy> GI combine LRx & LRy coalesce Estimate cost for spilling each live range spill costs Remove nodes from the graph simplify While stack is non-empty pop n, insert n into GI, & try to color it select spill Comp 412, Fall 2010 while N is non-empty if n with n < k then push n onto stack else pick n to spill push n onto stack remove n from GI Spill uncolored definitions & uses Briggs’ algorithm (1989) 38

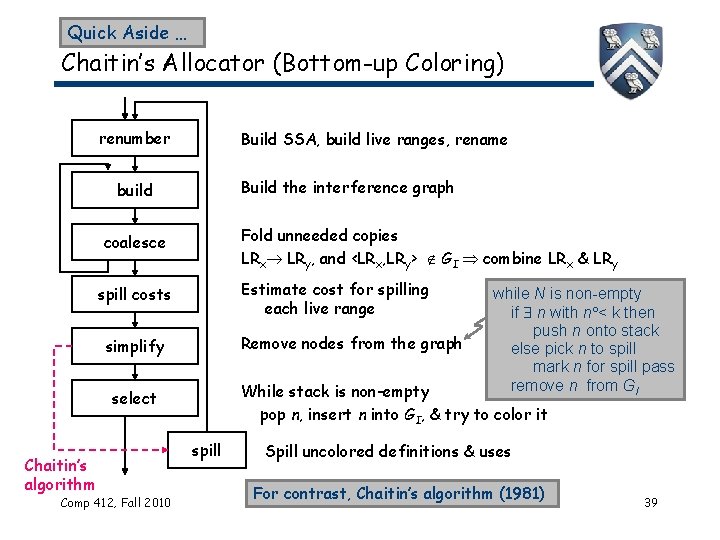

Quick Aside … Chaitin’s Allocator (Bottom-up Coloring) renumber Build SSA, build live ranges, rename Build the interference graph build Fold unneeded copies LRx LRy, and <LRx, LRy> GI combine LRx & LRy coalesce Estimate cost for spilling each live range spill costs Remove nodes from the graph simplify While stack is non-empty pop n, insert n into GI, & try to color it select Chaitin’s algorithm Comp 412, Fall 2010 while N is non-empty if n with n < k then push n onto stack else pick n to spill mark n for spill pass remove n from GI spill Spill uncolored definitions & uses For contrast, Chaitin’s algorithm (1981) 39

![Other Improvements to Chaitin-Briggs Spilling partial live ranges [Bergner PLDI 97] • Bergner introduced Other Improvements to Chaitin-Briggs Spilling partial live ranges [Bergner PLDI 97] • Bergner introduced](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/31fde8d0b97c6befb5571c41c66ac802/image-41.jpg)

Other Improvements to Chaitin-Briggs Spilling partial live ranges [Bergner PLDI 97] • Bergner introduced interference region spilling • Limits spilling to regions of high demand for registers Splitting live ranges [Simpson CC 98, Eckhardt ICPLC 05] • Simple idea — break up one or more live ranges • Allocator can use different registers for distinct subranges • Allocator can spill subranges independently (use 1 spill location) Iterative coalescing [George & Appel] • Use conservative coalescing because it is “safe” • Simplify the graph until only non-trivial nodes remain • Coalesce & try again • If coalescing does not reveal trivial nodes, then spill Comp 412, Fall 2010 40

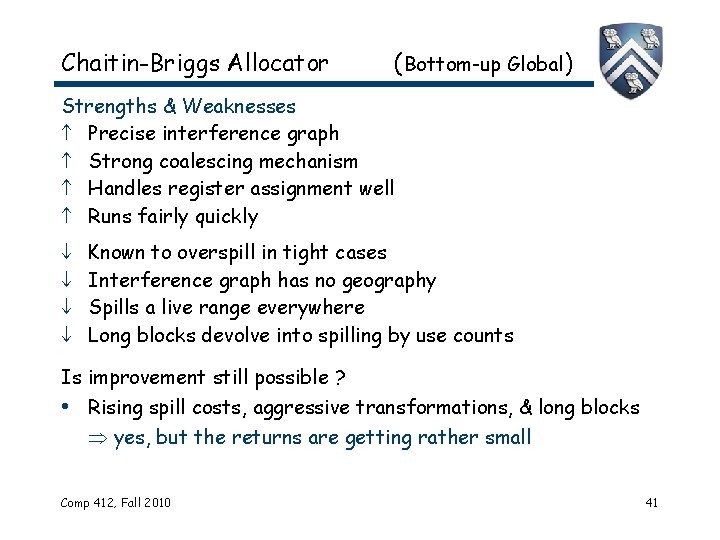

Chaitin-Briggs Allocator (Bottom-up Global) Strengths & Weaknesses Precise interference graph Strong coalescing mechanism Handles register assignment well Runs fairly quickly ¯ ¯ Known to overspill in tight cases Interference graph has no geography Spills a live range everywhere Long blocks devolve into spilling by use counts Is improvement still possible ? • Rising spill costs, aggressive transformations, & long blocks yes, but the returns are getting rather small Comp 412, Fall 2010 41

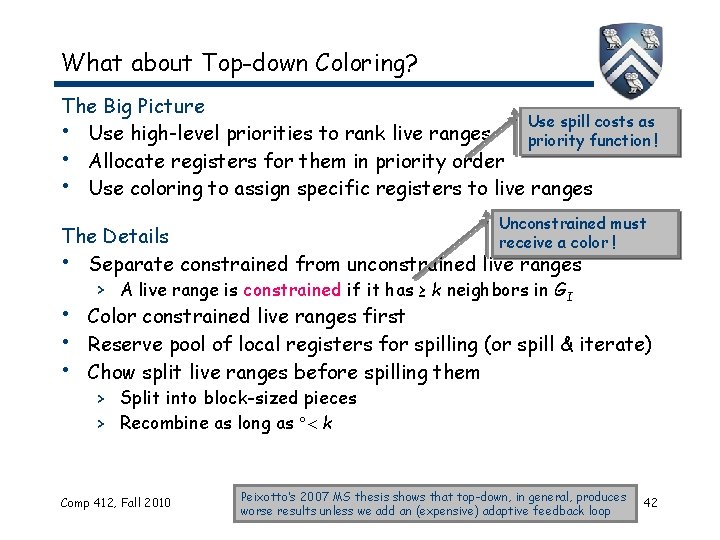

What about Top-down Coloring? The Big Picture Use spill costs as • Use high-level priorities to rank live ranges priority function ! • Allocate registers for them in priority order • Use coloring to assign specific registers to live ranges Unconstrained must The Details receive a color ! • Separate constrained from unconstrained live ranges > A live range is constrained if it has ≥ k neighbors in GI • Color constrained live ranges first • Reserve pool of local registers for spilling (or spill & iterate) • Chow split live ranges before spilling them > Split into block-sized pieces > Recombine as long as k Comp 412, Fall 2010 Peixotto’s 2007 MS thesis shows that top-down, in general, produces worse results unless we add an (expensive) adaptive feedback loop 42

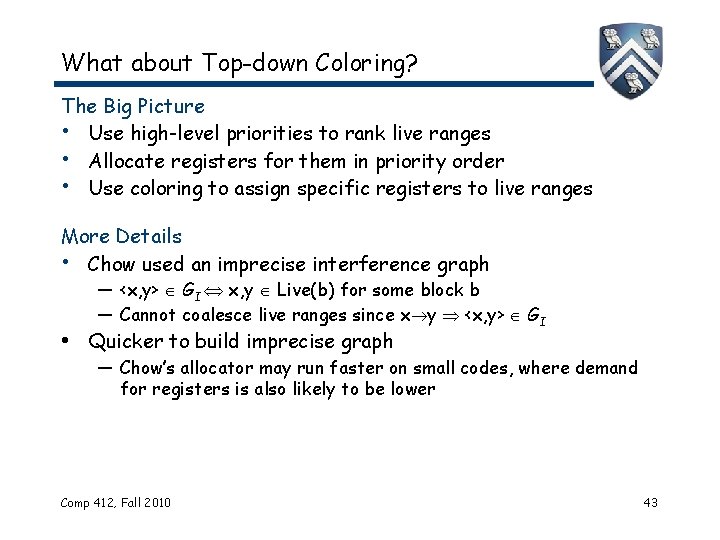

What about Top-down Coloring? The Big Picture • Use high-level priorities to rank live ranges • Allocate registers for them in priority order • Use coloring to assign specific registers to live ranges More Details • Chow used an imprecise interference graph — <x, y> GI x, y Live(b) for some block b — Cannot coalesce live ranges since x y <x, y> GI • Quicker to build imprecise graph — Chow’s allocator may run faster on small codes, where demand for registers is also likely to be lower Comp 412, Fall 2010 43

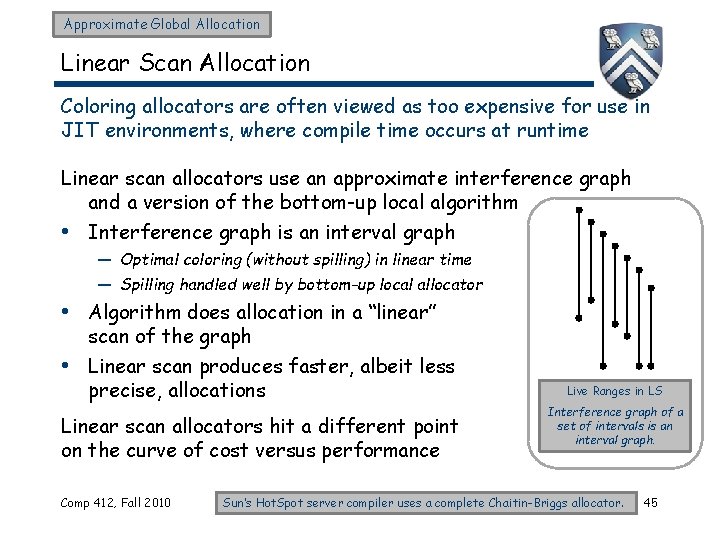

Approximate Global Allocation Linear Scan Allocation Coloring allocators are often viewed as too expensive for use in JIT environments, where compile time occurs at runtime Linear scan allocators use an approximate interference graph and a version of the bottom-up local algorithm • Interference graph is an interval graph — Optimal coloring (without spilling) in linear time — Spilling handled well by bottom-up local allocator • Algorithm does allocation in a “linear” • scan of the graph Linear scan produces faster, albeit less precise, allocations Linear scan allocators hit a different point on the curve of cost versus performance Comp 412, Fall 2010 Live Ranges in LS Interference graph of a set of intervals is an interval graph. Sun’s Hot. Spot server compiler uses a complete Chaitin-Briggs allocator. 45

Linear Scan Allocation Building the Interval Graph • Consider the procedure as a linear list of operations • A live range for some name is an interval (x, y) — x and y are the indices of two operations in the list, with x < y — Every operation where name is live falls between x & y, inclusive Precision of live computation can vary with cost — Interval graph overestimates interference The Algorithm • Use Best’s algorithm — bottom-up local • Distance to next use is well defined • Algorithm is fast & produces reasonable allocations Variations have been proposed that build on this scheme Comp 412, Fall 2010 46

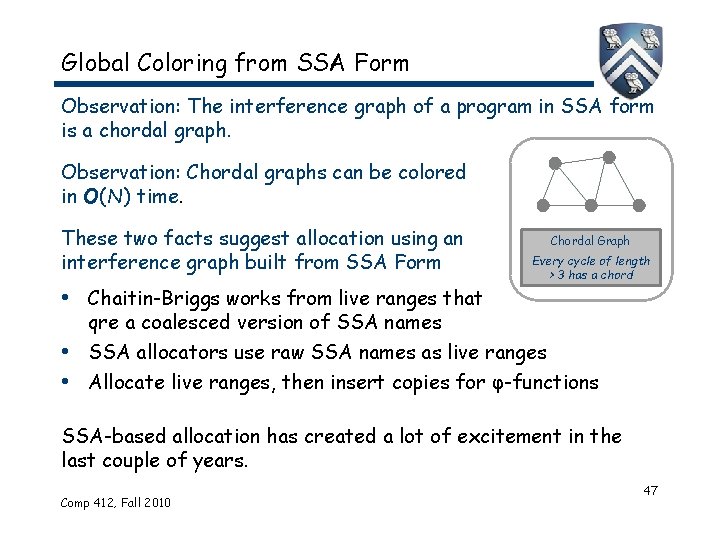

Global Coloring from SSA Form Observation: The interference graph of a program in SSA form is a chordal graph. Observation: Chordal graphs can be colored in O(N ) time. These two facts suggest allocation using an interference graph built from SSA Form • Chaitin-Briggs works from live ranges that Chordal Graph Every cycle of length > 3 has a chord qre a coalesced version of SSA names • SSA allocators use raw SSA names as live ranges • Allocate live ranges, then insert copies for φ-functions SSA-based allocation has created a lot of excitement in the last couple of years. Comp 412, Fall 2010 47

Global Coloring from SSA Form Coloring from SSA Names has its advantages • If graph is k-colorable, it finds the coloring — (Opinion ) An SSA-based allocator will find more k-colorable graphs than a live-range based allocator because SSA names are shorter and, thus, have fewer interferences. • Allocator should be faster than a live-range allocator — Cost of live analysis folded into SSA construction, where it is amortized over other passes — Biggest expense in Chaitin-Briggs is the Build-Coalesce phase, which SSA allocator avoids, as it destroys the chordal graph Comp 412, Fall 2010 48

Global Coloring from SSA Form Coloring from SSA Names has its disadvantages • Coloring is rarely the problem — Most non-trivial codes spill; on trivial codes, both SSA allocator and classic Chaitin-Briggs are overkill. (Try linear scan? ) • SSA form provides no obvious help on spilling — Shorter live ranges will produce local spilling (good & bad) — May increase spills inside loops Loop-carried value cannot • After allocation, code is still in SSA form — — Need out-of-SSA translation spill before the loop, since its name is only live inside the loop and after the loop. Introduce copies after allocation Swap problem may require and extra register Must run a post-allocation coalescing phase Algorithms exist that do not use an interference graph They are not as powerful as the Chaitin-Briggs coalescing phase Comp 412, Fall 2010 49

Hybrid Approach ? How can the compiler attain both speed and precision? Observation: lots of procedures are small & do not spill Observation: some procedures are hard to allocate Possible solution: • Try different algorithms • First, try linear scan — It is cheap and it may work • If linear scan fails, try heavyweight allocator of choice — Might be Chaitin-Briggs, SSA, or some other algorithm — Use expensive allocator only when cheap one spills This approach would not help with the speed of a complex compilation, but it might compensate on simple compilations Comp 412, Fall 2010 50

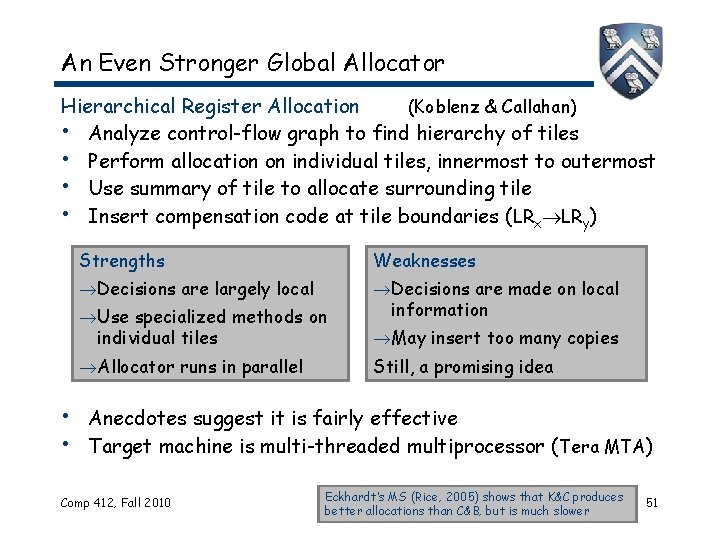

An Even Stronger Global Allocator Hierarchical Register Allocation (Koblenz & Callahan) • Analyze control-flow graph to find hierarchy of tiles • Perform allocation on individual tiles, innermost to outermost • Use summary of tile to allocate surrounding tile • Insert compensation code at tile boundaries (LRx LRy) Strengths Weaknesses Decisions are largely local Decisions are made on local Use specialized methods on individual tiles Allocator runs in parallel information May insert too many copies Still, a promising idea • Anecdotes suggest it is fairly effective • Target machine is multi-threaded multiprocessor (Tera MTA) Comp 412, Fall 2010 Eckhardt’s MS (Rice, 2005) shows that K&C produces better allocations than C&B, but is much slower 51

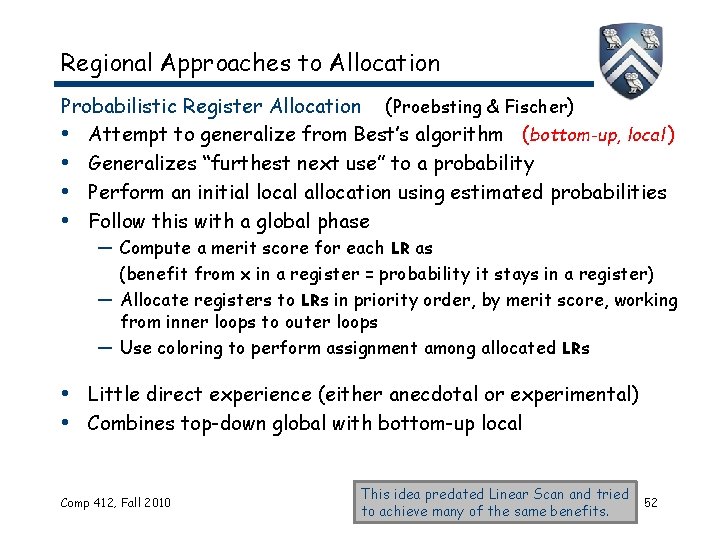

Regional Approaches to Allocation Probabilistic Register Allocation (Proebsting & Fischer) • Attempt to generalize from Best’s algorithm (bottom-up, local ) • Generalizes “furthest next use” to a probability • Perform an initial local allocation using estimated probabilities • Follow this with a global phase — Compute a merit score for each LR as (benefit from x in a register = probability it stays in a register) — Allocate registers to LRs in priority order, by merit score, working from inner loops to outer loops — Use coloring to perform assignment among allocated LRs • Little direct experience (either anecdotal or experimental) • Combines top-down global with bottom-up local Comp 412, Fall 2010 This idea predated Linear Scan and tried to achieve many of the same benefits. 52

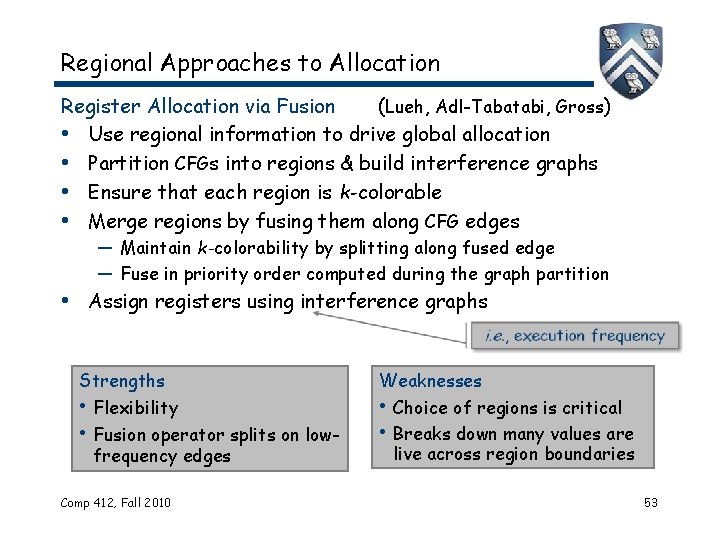

Regional Approaches to Allocation Register Allocation via Fusion (Lueh, Adl-Tabatabi, Gross) • Use regional information to drive global allocation • Partition CFGs into regions & build interference graphs • Ensure that each region is k-colorable • Merge regions by fusing them along CFG edges — Maintain k-colorability by splitting along fused edge — Fuse in priority order computed during the graph partition • Assign registers using interference graphs Strengths • Flexibility • Fusion operator splits on lowfrequency edges Comp 412, Fall 2010 Weaknesses • Choice of regions is critical • Breaks down many values are live across region boundaries 53

Extra Slides Start Here Comp 412, Fall 2010 54

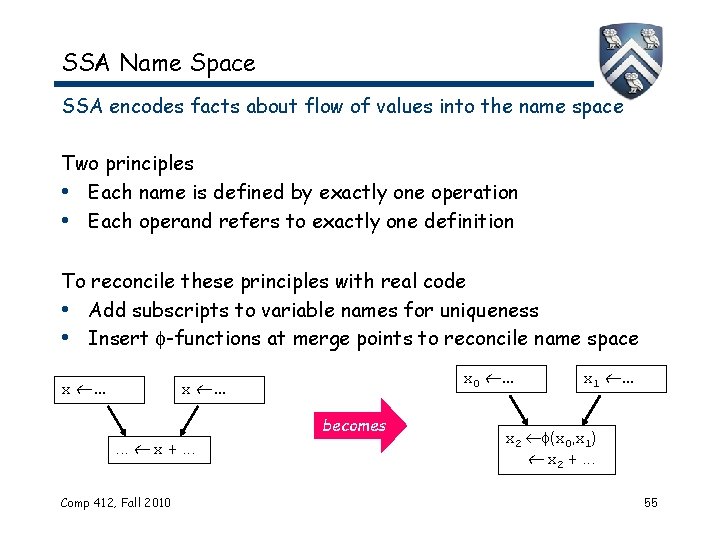

SSA Name Space SSA encodes facts about flow of values into the name space Two principles • Each name is defined by exactly one operation • Each operand refers to exactly one definition To reconcile these principles with real code • Add subscripts to variable names for uniqueness • Insert -functions at merge points to reconcile name space x . . . x 0 . . . x . . . becomes. . . x +. . . Comp 412, Fall 2010 x 1 . . . x 2 (x 0, x 1) x 2 +. . . 55

SSA Name Space These -functions are unusual constructs … • A -function only occurs at the start of a block • A -function has one argument for each CFG edge entering the block • A -function returns the argument that corresponds to the edge along which control flow entered the block — All -functions in the block execute concurrently — Since machines do not support -functions, must translate back out of SSA form before we produce executable code • All -functions in a block execute concurrently — All read their argument, all perform assignment in parallel • Using SSA form leads to simpler or better formulations of many optimizations (alternative to global data-flow analysis ) Comp 412, Fall 2010 56

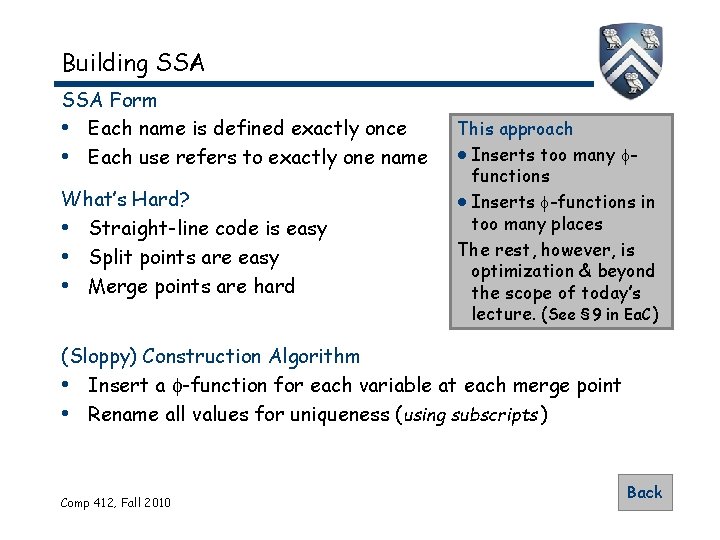

Building SSA Form • Each name is defined exactly once • Each use refers to exactly one name What’s Hard? • Straight-line code is easy • Split points are easy • Merge points are hard This approach Inserts too many functions Inserts -functions in too many places The rest, however, is optimization & beyond the scope of today’s lecture. (See § 9 in Ea. C) (Sloppy) Construction Algorithm • Insert a -function for each variable at each merge point • Rename all values for uniqueness (using subscripts ) Comp 412, Fall 2010 Back 57

Slides on Rematerialization Cannot be taught without Wegman-Zadeck Sparse Simple Constant Propagation. Comp 412, Fall 2010 58

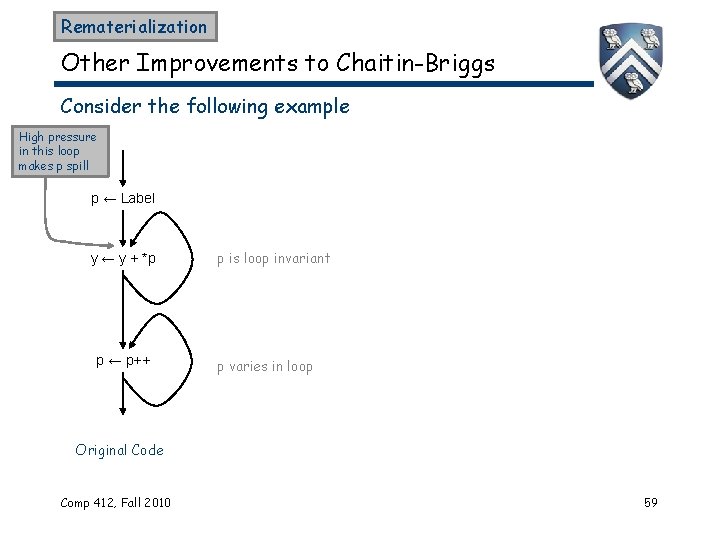

Rematerialization Other Improvements to Chaitin-Briggs Consider the following example High pressure in this loop makes p spill p ← Label y ← y + *p p ← p++ p is loop invariant p varies in loop Original Code Comp 412, Fall 2010 59

- Slides: 59