Communicating under stress Reflecting on our nonverbal behavior

Communicating under stress: Reflecting on our non-verbal behavior Kris Gould, LCSW and Sarah Neudeck, LCSW Professional Practice Exchange September 25, 2018 1

Today’s focus We’re always communicating! Today: Non-verbal communication, specifically body language and tone of voice. Words are important, but are not our focus today. The non-verbal communication we use with patients, families, colleagues, and care providers can help build relationships or harm them. When under stress, our non-verbal communication speaks volumes about our inner thoughts, positive and negative, as well as biases we may not realize we have. With Hospice Compare, it is essential to reflect on how we are coming across to our “customers. ” We will practice conversations and reflect on our own non-verbal styles. 2

Goals To gain greater understanding of how important our non-verbal communication is in building or harming relationships that are essential to our work. To develop a greater awareness of our own non-verbal communication style, especially under stress, and how that style impacts patients, families, colleagues, and care providers. 3

Agenda Self-reflection exercise Basics of communication Verbal vs. non-verbal – there’s what we say (our thoughts), and what we convey (our emotions, attitudes) Types of non-verbal communication Body language - Sarah Tone of voice - Kris Non-verbal communication under stress Practice scenarios Sample role play Small groups practice 4

5

Practicing self-reflection What your body is telling you right now Don’t change a thing! Apply mood dot (yes a mood dot!) Close your eyes if you’d like. What do you notice in your body right now? Are you sleepy? ! How is your breathing – shallow or deep? How are your muscles – tight or loose? How about your jaw, your tongue? What is your internal dialogue saying right now? Open your eyes – what color is your mood dot? What kinds of patient/family/facility conversations in your work cause you stress? Think of a time at work when you were really stressed. Where did you feel it in your body? Where do you hold stress? Face, muscles? posture? breathing? voice? Is there body tightness? shallow breathing or no breathing!? are shoulders up or tight? How’s your belly? What do others see and hear in us when we feel this way? 6

Practicing self-reflection Helping our bodies and our minds “Headspace” app –guided relaxation Did your mood dot color change? ! (even if it didn’t, what do you sense in your body now? ) Why is it difficult to maintain a sense of peace when we’re in a stressful situation? This exercise in tension and release is a tool to become more aware of the connection between stress and what our bodies reveal. 7

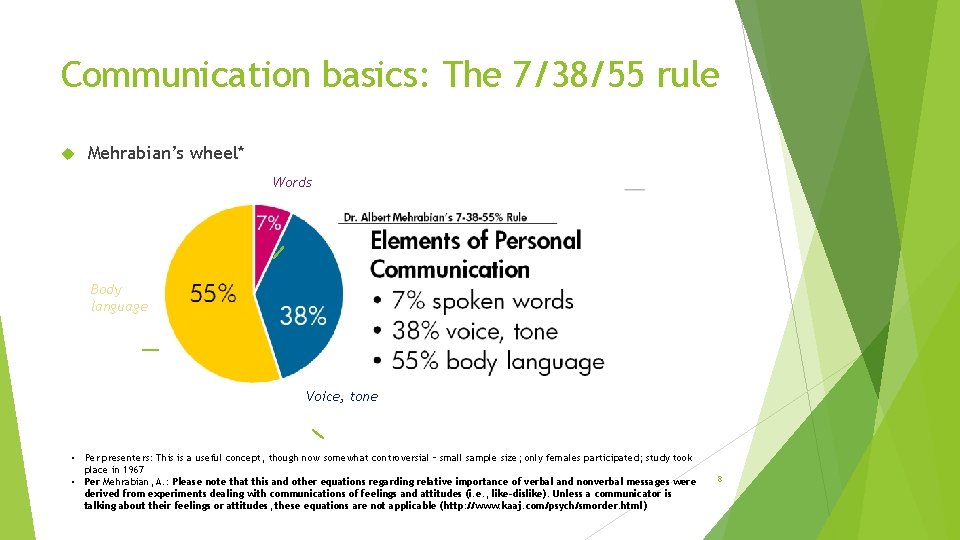

Communication basics: The 7/38/55 rule Mehrabian’s wheel* Words Body language Voice, tone • Per presenters: This is a useful concept, though now somewhat controversial – small sample size; only females participated; study took place in 1967 • Per Mehrabian, A. : Please note that this and other equations regarding relative importance of verbal and nonverbal messages were derived from experiments dealing with communications of feelings and attitudes (i. e. , like-dislike). Unless a communicator is talking about their feelings or attitudes, these equations are not applicable (http: //www. kaaj. com/psych/smorder. html) 8

Body language 9

What is Body Language? Body language is the gestures, movements, and mannerisms by which a person or animal communicates with others - Miriam Webster Body language is not always something we know we are doing or interpreting as we communicate with others Body language may vary culturally, so be mindful – e. g. proximity, eye contact Having skillful non-verbal communication via body language can improve the clinical connection with patients and families 10

Body language - what you’re already doing! We already watch a patient’s body language to monitor for pain Facial grimacing or a frown Writhing or constant shifting in bed Moaning, groaning, or whimpering Restlessness and agitation Appearing uneasy and tense, perhaps drawing their legs up or kicking Guarding the area of pain or withdrawing from touch to that area 11

Most common cues in body language? Eyes - direct eye contact, no eye contact, blinking rate, being at eye level Face - interested, disengaged Proximity - close, backing away, constant moving around the room Mirroring - can mean a person is trying to establish rapport (not always conscious) Head movement - nodding (with interest or too quickly to end discussion), tilting head Position of the hands and feet - crossed, open, moving, restless Arm position - crossed, open, tense Posture - engaged, confident, withdrawn, uninterested Mouth - smiling, pursed lips, relaxed mouth 12

Body language – questions for discussion Importance of reading cues: How do you know if a patient or family member doesn’t want you there? What does their body language look like? How do patients or family members know if the clinician doesn’t feel like being there? (e. g. the clinician is having a difficult and stressful day) Will our body language show that? Does our body language change if we like a patient or not? or if we don’t like what they’re saying? What if they don’t follow our advice or follow MD orders? How can we cue ourselves to be more mindful about our body language before each visit? And during a visit? 13

Tone of voice Video: https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=b 44 ZL 3 L 1 nfo (Seinfeld, 0: 0001: 04) Tone conveys our emotions, attitudes, authenticity…“I like your hair…” “You’re opposed to morphine” Tone conveys our attitude - e. g. if we think the person we’re speaking with is ____ (wonderful, stupid, crazy, elitist, less intelligent than we feel we are), our patients, families, colleagues and community partners will know. Video: https: //www. ted. com/talks/julian_treasure_how_to_speak_so_that_people_ want_to_listen/up-next#t-536022 (4: 18 -7: 18) 14

Tone of voice Aspects: Register (high, medium, low) Timbre (e. g. rich voices vs. shrill) Prosody (pitch variation - monotone? ending sentences with a question mark? ) Pace (rapid for emphasis, slow for emphasis; utilizing a pause or silence) Pitch/emphasis/cadence (Why did you do that? – which one conveys what? ) Volume (louder for emphasis or very quiet for emphasis) Are we making choices about the above, or doing “what comes naturally? ” Owning our emotion: “I know my tone may not match what I’m trying to convey – I can sound frustrated when I’m actually trying to help” – can be a de-escalator Technology becoming more able to detect emotions! Harder to hide what we really think and feel! 15

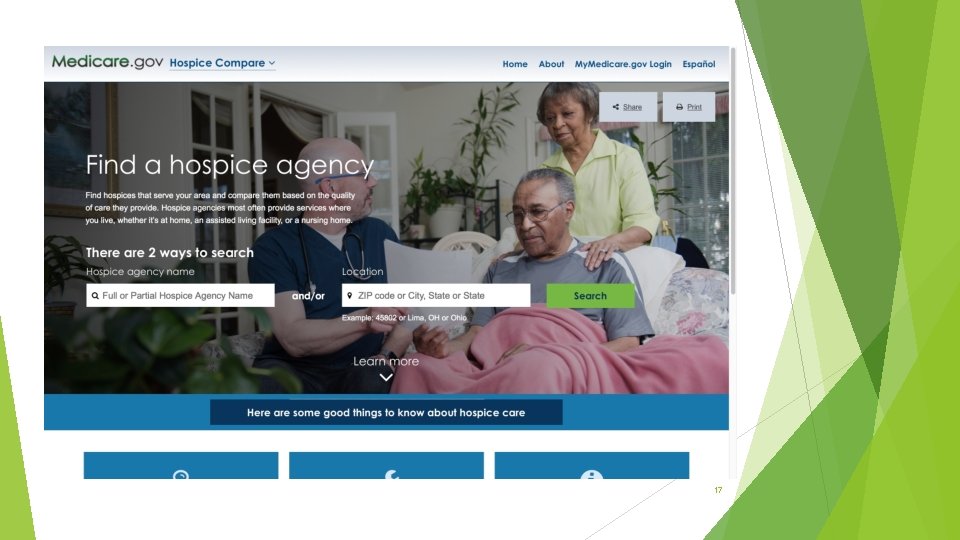

Tone of voice – why else does it matter? Many websites about “tone of voice” focus on marketing, customer service, a company’s “brand” How do these words land with you? Do you think these terms apply to hospice? Can we influence “customer satisfaction” with our tone of voice? The day of Hospice Compare is here; we’re always being evaluated https: //www. medicare. gov/hospicecompare 16

17

Non-verbal communication under stress 18

Non-verbal communication under stress How can we make choices about our non-verbal communication (body and tone)? We have an emotion, a reaction – what do we do with it? It starts with being aware that we all have reactions based on present and past circumstances, and that while we might want to just “wing it” based on what comes naturally, it might be better to make choices about our body language and tone of voice Ask yourself, when you are stressed, what is coming up for me about this that is getting my goat? “You’re full code! You can’t be full code and be on hospice!” Body tips – take that long deep breath – you have time. Let your jaw release, let your belly be soft; let your face soften. Be the ball, not the sponge! 19

Non-verbal communication under stress What kind of body language & tone of voice would want from a hospice clinician for your own family member? You have good intentions, and so does the person you’re speaking with. What if you view the same issue differently? Exploring differences with compassion and respect through body language and tone of voice may be the most effective communication tool. Other ideas for self-reflection of our own styles: Body scan – what’s your body telling you right now? (breath, muscle tension, jaw and tongue? ) Become painfully aware – e. g. record the conversations you have with your family members from 6: 00 -7: 00 pm, then review the recording on your own Have a trusted friend or colleague weigh in… What is your resting face? The case of the Social Worker with the furrowed brow… 20

Practicing and observing non-verbal communication under stress Role play: Facility visit example (defensive/superior vs. exploratory) – Sarah and Kris Group exercise – Scenario script on next page Groups of three One person is the hospice clinician on the phone, one person is family member, one person is the observer Take 2 -3 minutes to each play a different role – same scenario. Practice using different body language and tones of voice during your turn. If you’re really brave, have the observer video you (on your own phone) while you’re playing the hospice clinician role – then review it later on your own time – to watch your body language, hear your tone of voice. 21

Scenario script Again, one of you is a hospice clinician, one of you is a daughter of a hospice patient, and one of you is an observer. Take about 2 minutes each to role play the following scenario: You are the hospice clinician. You receive a phone call at 1700 from daughter of 68 y/o female hospice patient with CHF. As the daughter, you say loudly and quickly that your mother “can’t breathe” and that “she needs a visit right away or I’ll call 911!” You as the clinician are aware all available field RNs are in other visits and the assigned RN is finished for the day. Being mindful of tone and body language, how would you respond to the daughter? As the daughter, how would you feel/respond based on the clinician’s response? As the observer, watch body language and listen for tone of clinician and daughter. Pay less attention to the words. Observer can video the “clinician’s” or “daughter’s” non-verbal behavior if so desired on that person’s cell phone. Switch roles and repeat above (2 minutes). Then switch again (2 minutes) so everyone has a chance to play each role. When you are the observer, please share your observations with the other 2 group members at end of each round. We’ll come back together as a group and discuss after everyone has had a chance to play each role (clinician, daughter, and observer) 22

Today’s goals – We hope we helped you… …Gain greater understanding of how important our non-verbal communication is in building or harming relationships that are essential to our work. …Develop a greater awareness of our own non-verbal communication style, especially under stress, and how that style impacts patients, families, colleagues, and care providers. Thank you for being here! 23

Resources/References P. 6: “Headspace” app - downloadable from your smart phone P. 7: Mehrabian’s rule: http: //www. kaaj. com/psych/smorder. html P. 7: Image from http: //www. rightattitudes. com/2008/10/04/7 -38 -55 -rule-personal-communication/ P. 8: https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=O 6 YCH 260 H 78&feature=youtu. be (for more information, see https: //www. steverrobbins. com/) P. 14: Maya Angelou’s quote is very close to an original quote of attributed to Carl Buehner (“They may forget what you said — but they will never forget how you made them feel. ”) https: //quoteinvestigator. com/2014/04/06/theyfeel/ P. 16 https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=b 44 ZL 3 L 1 nfo Jerry Seinfeld P. 16: https: //www. ted. com/talks/julian_treasure_how_to_speak_so_that_people_want_to_listen/up-next#t-536022 Julian Treasure, TEDGlobal 2013 P. 18 -19: Hospice compare: https: //www. medicare. gov/hospicecompare 24

Appendix – Helpful verbal phrases, when combined with appropriate body language and tone 25

Helpful verbal phrases Sometimes we need to politely interrupt a patient or family member to re-focus the discussion. I’m sorry to interrupt you. You are sharing so many important things, and I want to make sure we cover your most immediate concern today. Or… I’m sorry to interrupt you. I am very interested in what you’re saying, but I also want to make sure we have time to work on xyz, if that’s what you are most concerned about. Sometimes gentle direction is needed when someone is in a tangential thinking pattern. With tangential thinkers, it is important to limit the amount of information you are giving and focus on 1 -2 items. I really want you to hear THIS piece of what we’re discussing (e. g. “the methadone needs to be taken on a schedule. How can we create reminders for you? ”) I’m concerned for your safety if you are not really hearing me say xyz.

Helpful verbal phrases (take a deep breath and say) “I really want to understand what you’re saying; could you. . ” or “I really want to help; it would be easier for me if you…” Speak more slowly Speak a little more softly Speak a little louder Focus on the main concern you’re having right now (take a deep breath and say) “It’s harder for me to help when someone’s voice is raised. Could you lower your voice so I can really hear what you’re saying? ” (speaking slowly and softly): I can hear things are really difficult right now. I want to ask you a few questions so I can help. Is that alright? Remember there is already a power differential between hospice staff and patients… we should consider softening this as much as possible vs. emphasizing it – i. e. we can move from the helper/helpee mindset to the partners- during-adifficult-time approach. 27

- Slides: 27