Common Mistakes in Graphics Excess information Multiple scales

- Slides: 63

Common Mistakes in Graphics • • • Excess information Multiple scales Using symbols in place of text Poor scales Using lines incorrectly © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

Excess Information • Sneaky trick to meet length limits • Rules of thumb: – 6 curves on line chart – 10 bars on bar chart – 8 slices on pie chart • Extract essence, don’t cram things in © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

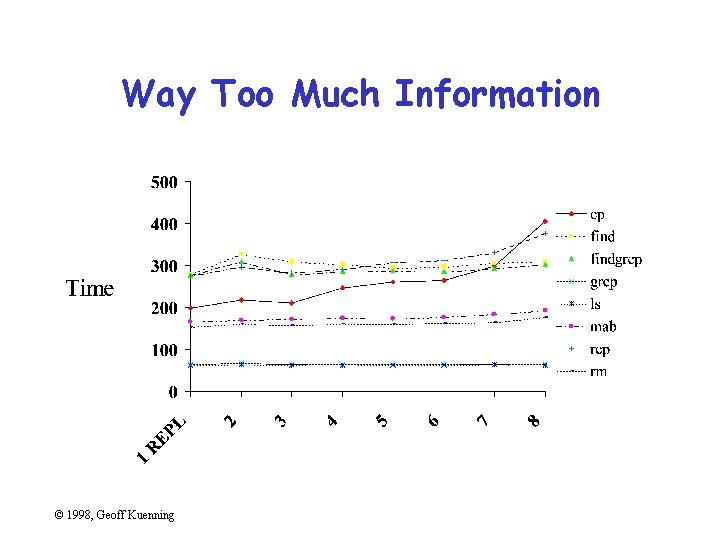

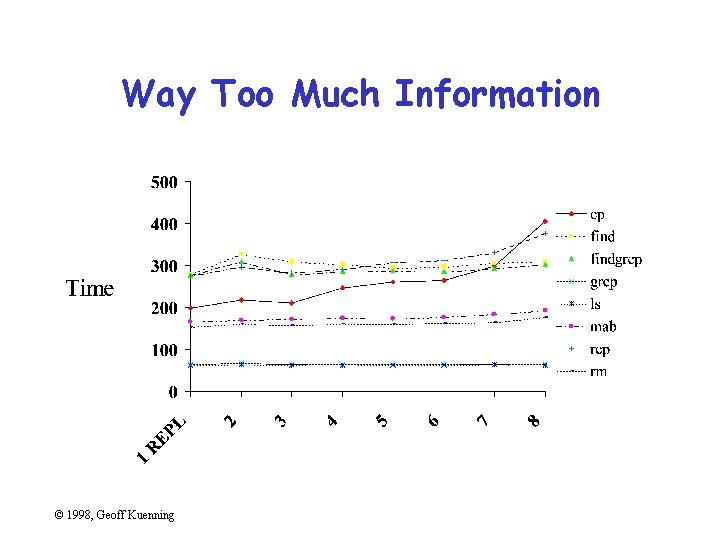

Way Too Much Information © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

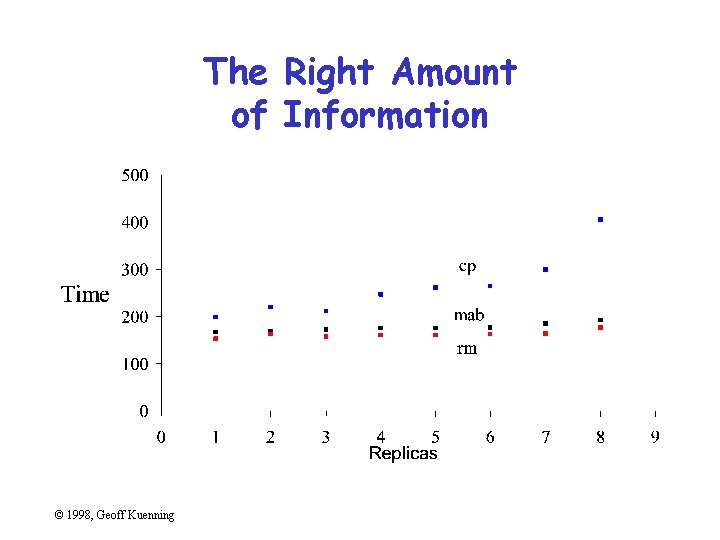

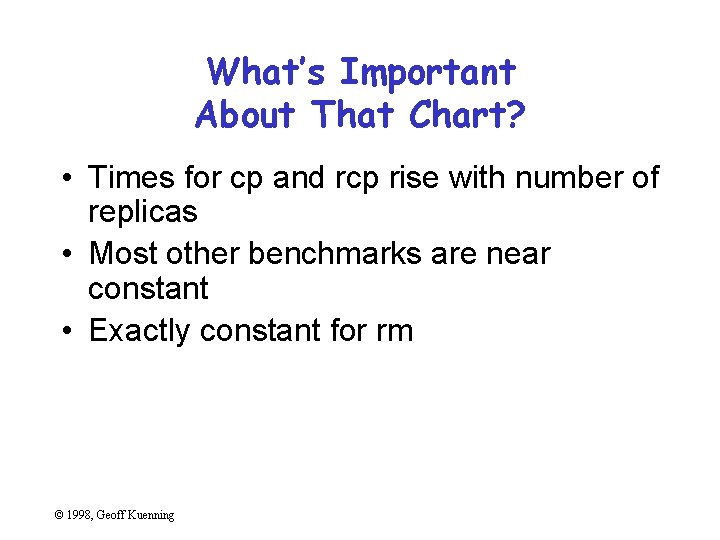

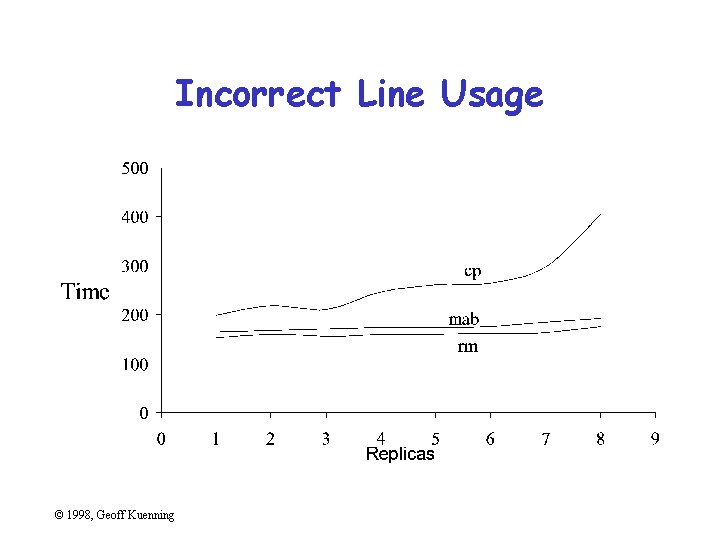

What’s Important About That Chart? • Times for cp and rcp rise with number of replicas • Most other benchmarks are near constant • Exactly constant for rm © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

The Right Amount of Information © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

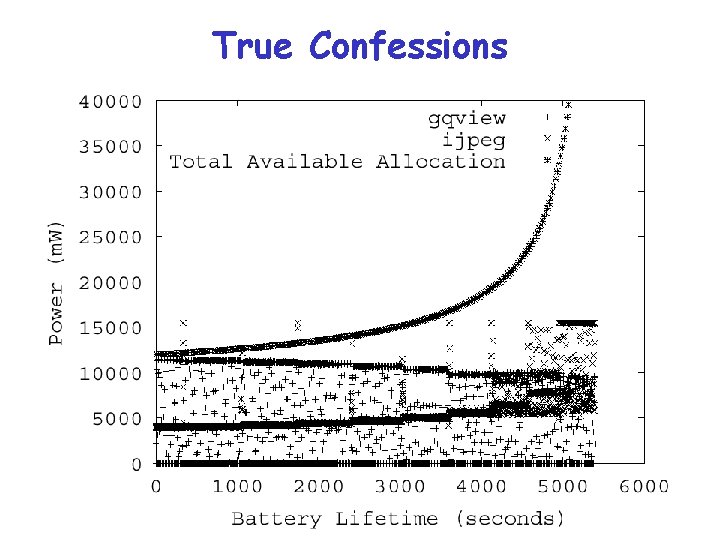

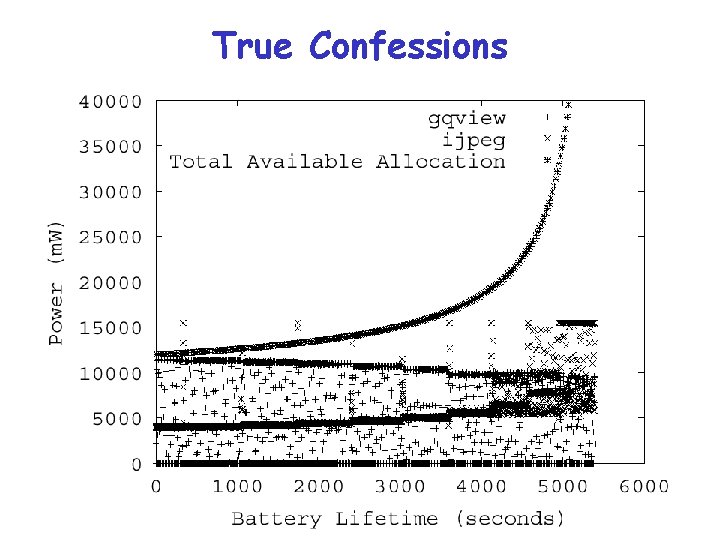

True Confessions

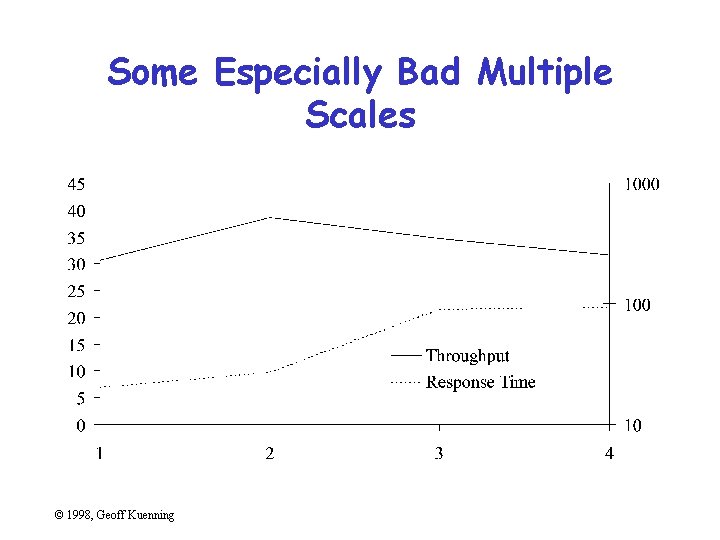

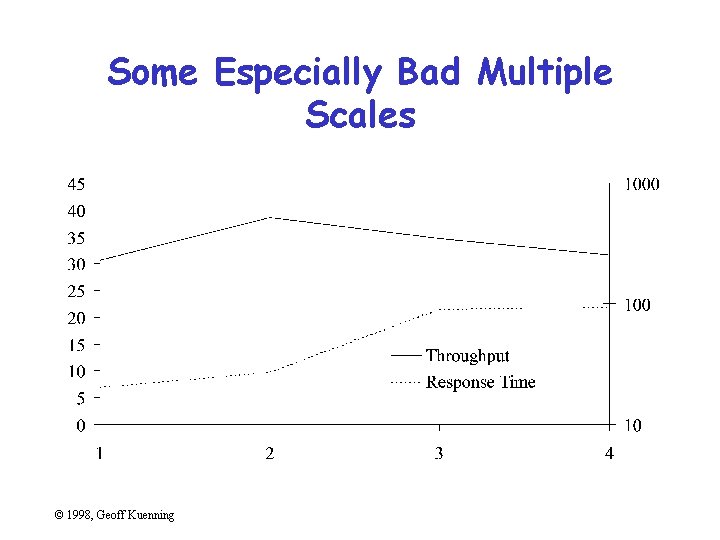

Multiple Scales • Another way to meet length limits • Basically, two graphs overlaid on each other • Confuses reader (which line goes with which scale? ) • Misstates relationships – Implies equality of magnitude that doesn’t exist © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

Some Especially Bad Multiple Scales © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

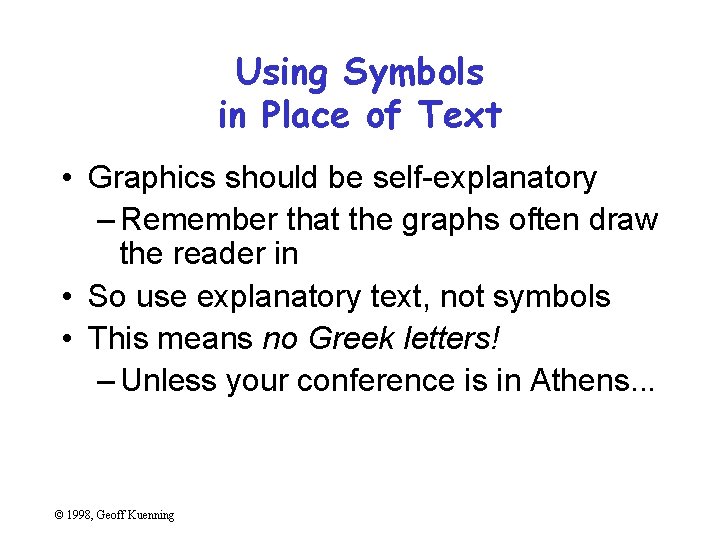

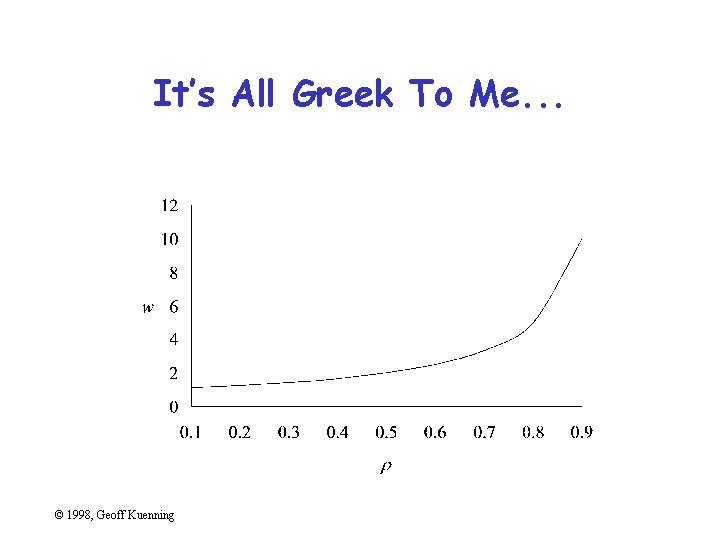

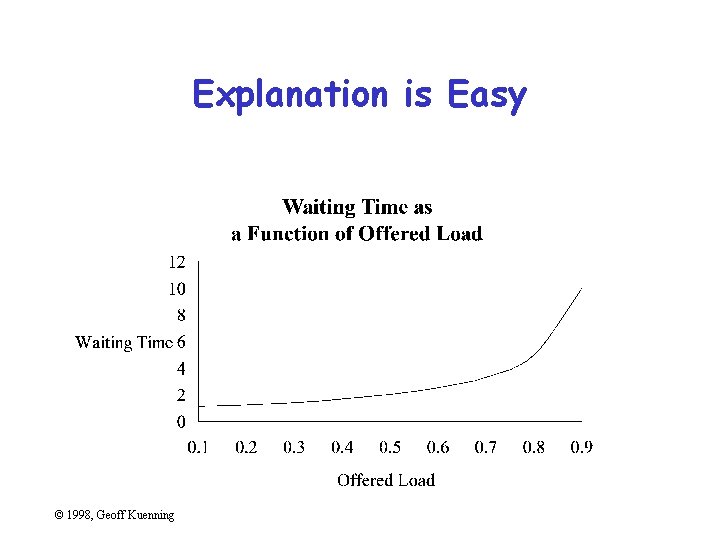

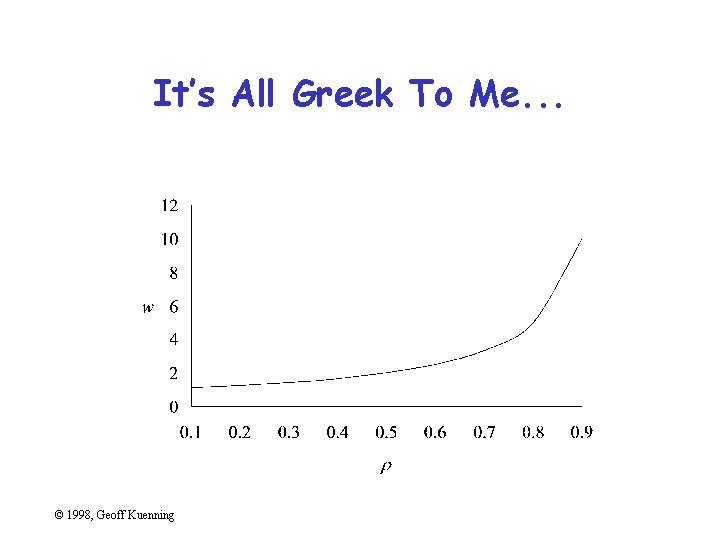

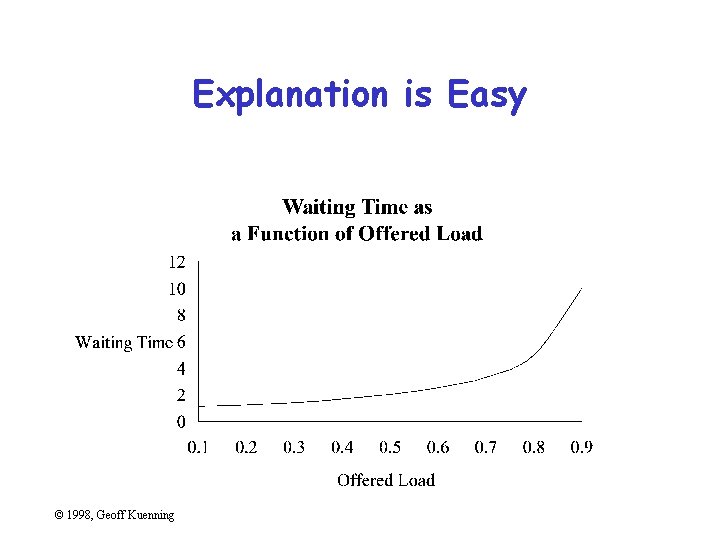

Using Symbols in Place of Text • Graphics should be self-explanatory – Remember that the graphs often draw the reader in • So use explanatory text, not symbols • This means no Greek letters! – Unless your conference is in Athens. . . © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

It’s All Greek To Me. . . © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

Explanation is Easy © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

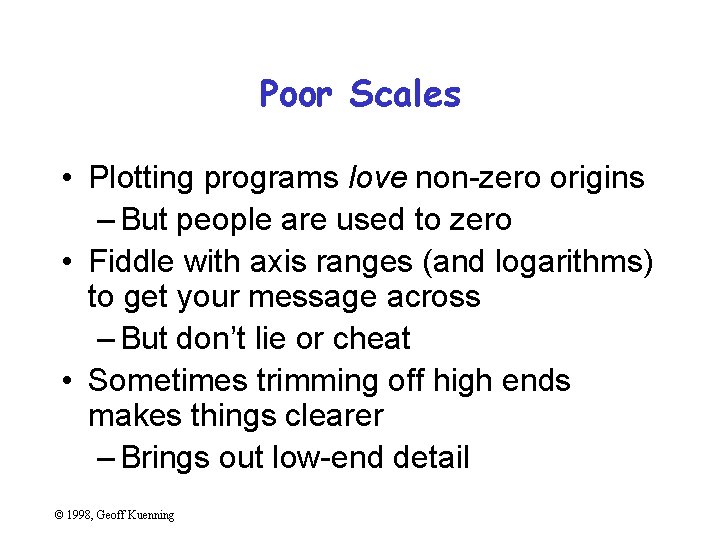

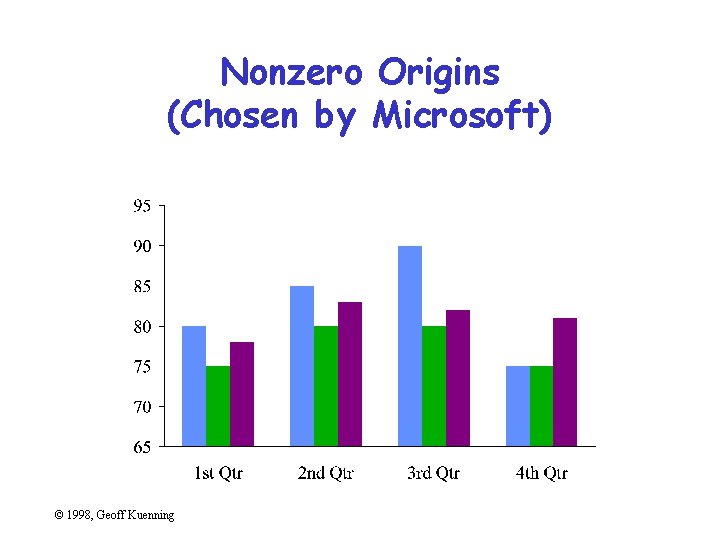

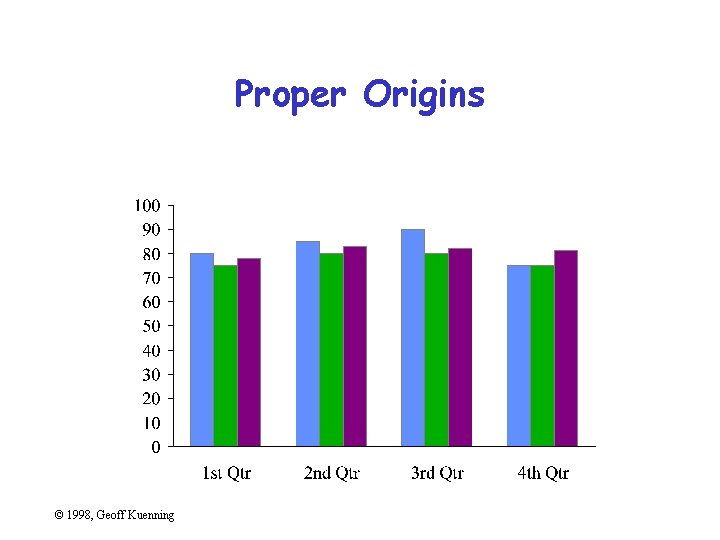

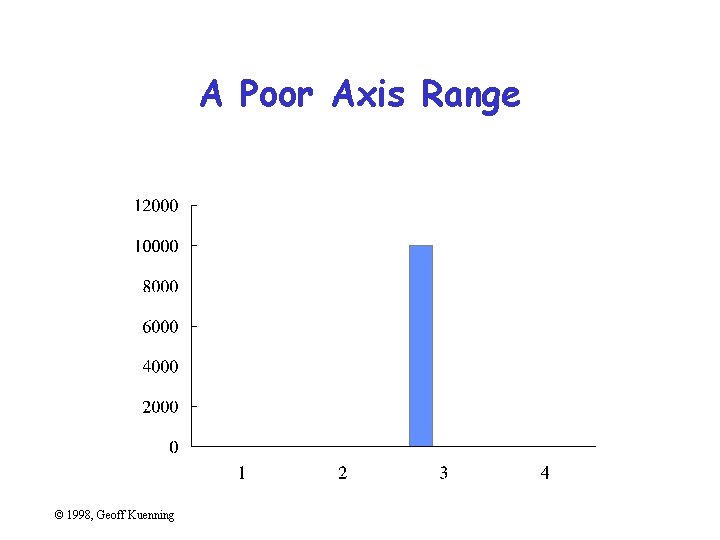

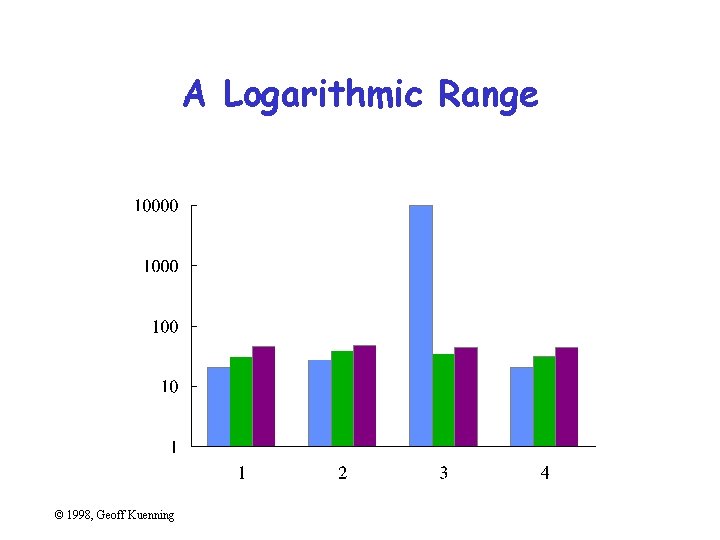

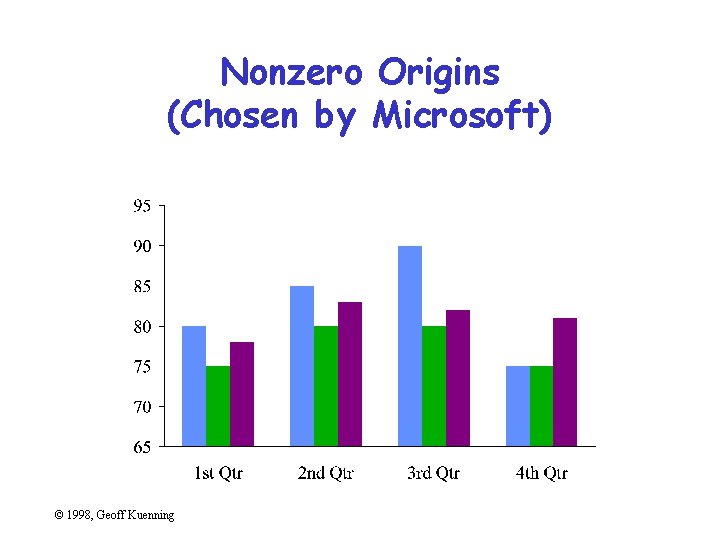

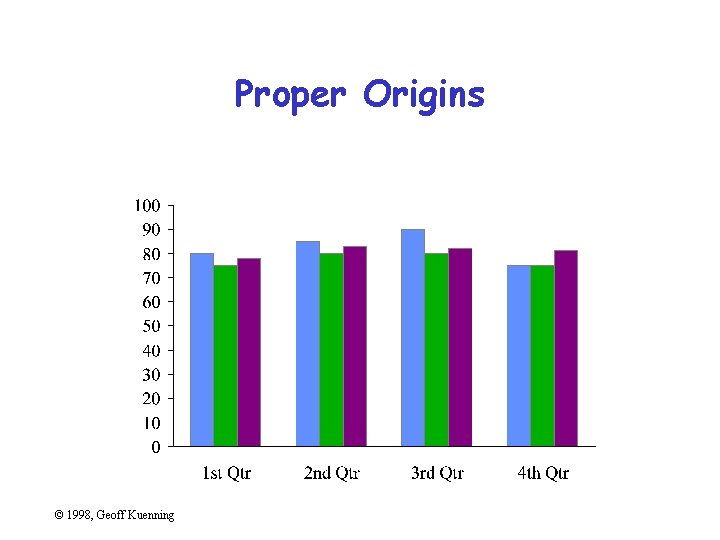

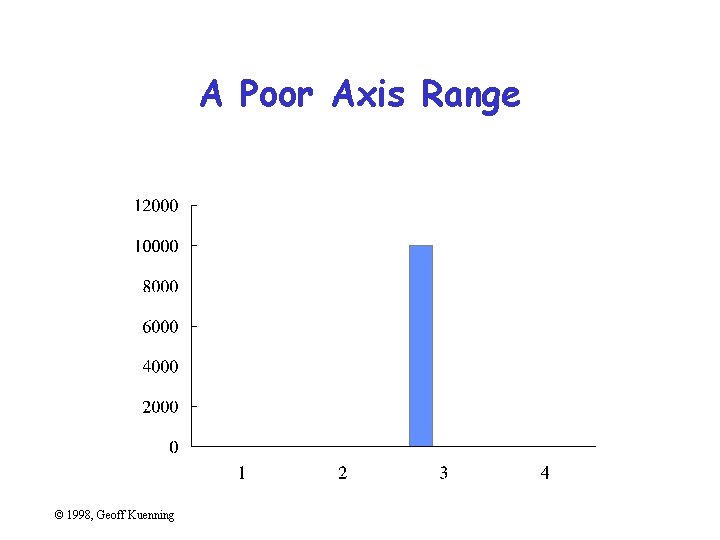

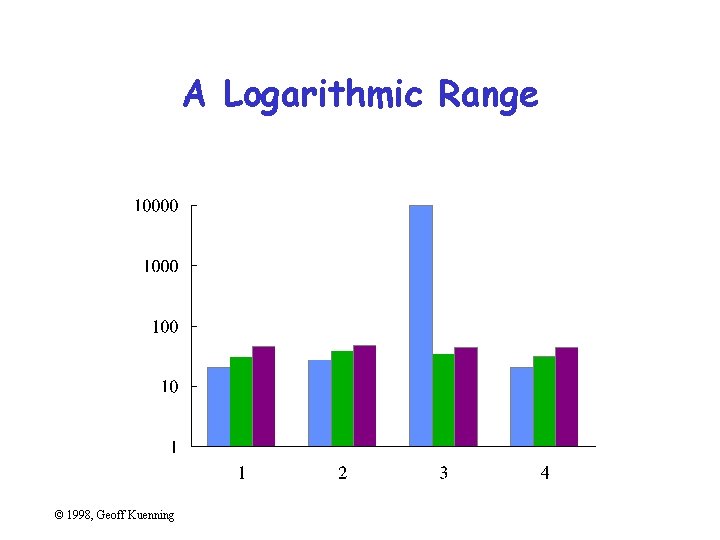

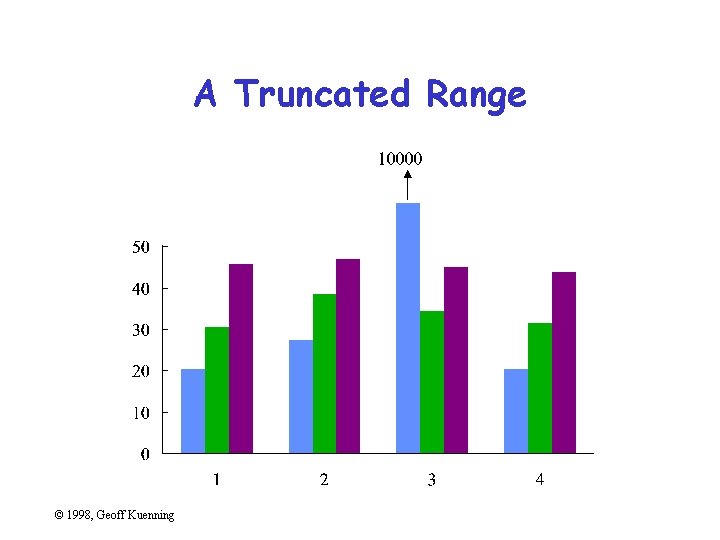

Poor Scales • Plotting programs love non-zero origins – But people are used to zero • Fiddle with axis ranges (and logarithms) to get your message across – But don’t lie or cheat • Sometimes trimming off high ends makes things clearer – Brings out low-end detail © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

Nonzero Origins (Chosen by Microsoft) © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

Proper Origins © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

A Poor Axis Range © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

A Logarithmic Range © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

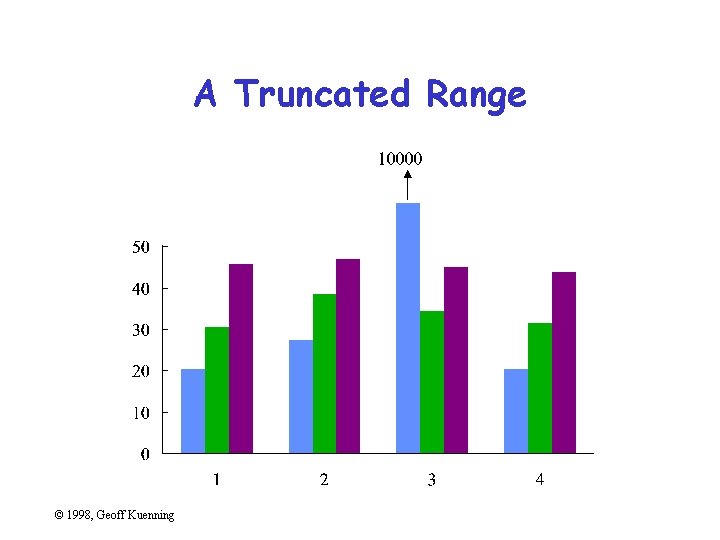

A Truncated Range © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

Using Lines Incorrectly • Don’t connect points unless interpolation is meaningful • Don’t smooth lines that are based on samples – Exception: fitted non-linear curves © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

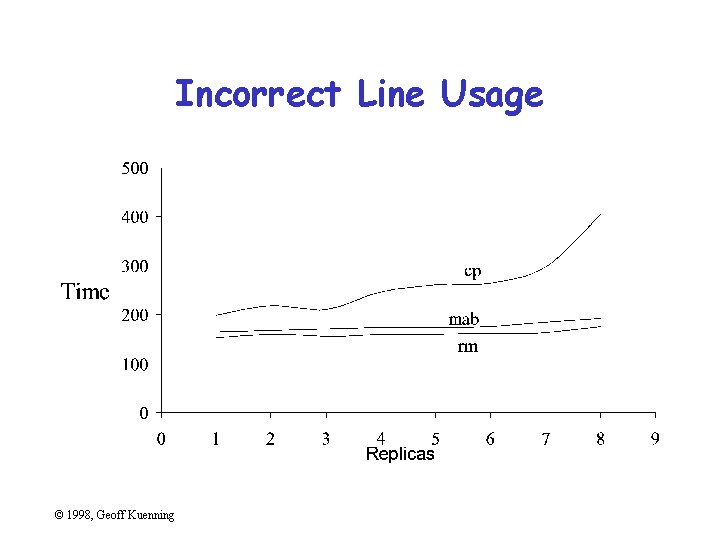

Incorrect Line Usage © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

Pictorial Games • • • Non-zero origins and broken scales Double-whammy graphs Omitting confidence intervals Scaling by height, not area Poor histogram cell size © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

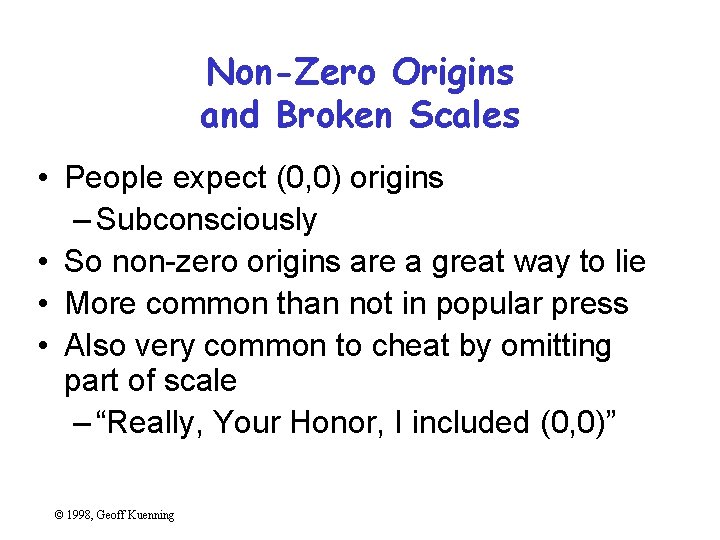

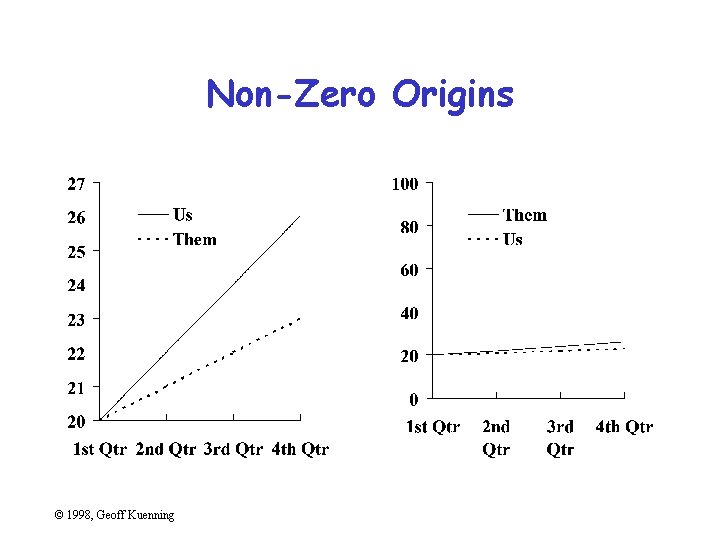

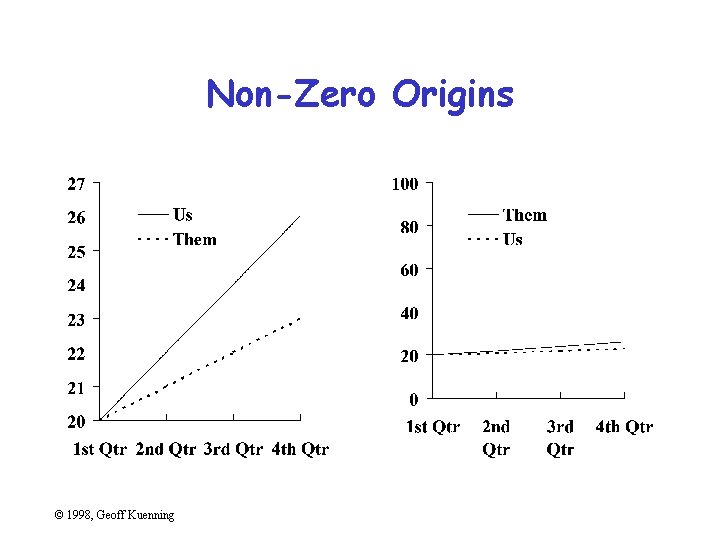

Non-Zero Origins and Broken Scales • People expect (0, 0) origins – Subconsciously • So non-zero origins are a great way to lie • More common than not in popular press • Also very common to cheat by omitting part of scale – “Really, Your Honor, I included (0, 0)” © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

Non-Zero Origins © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

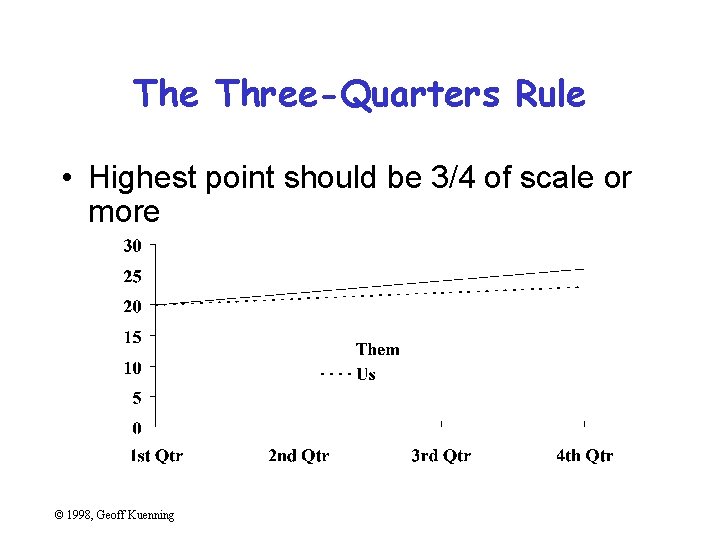

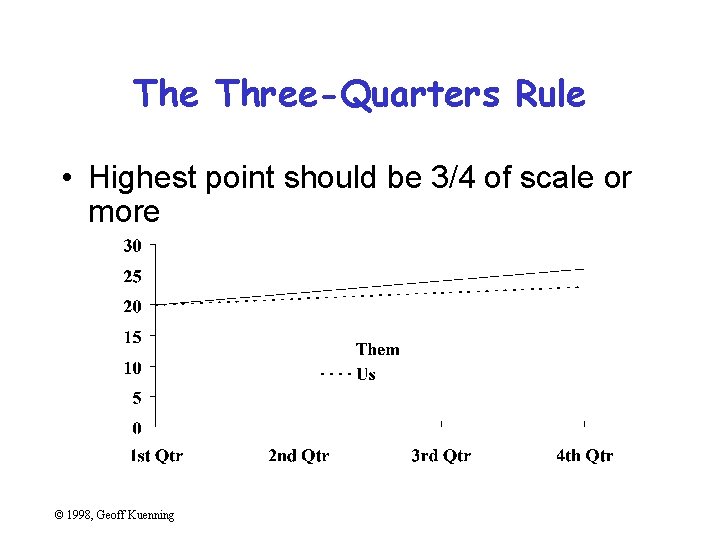

The Three-Quarters Rule • Highest point should be 3/4 of scale or more © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

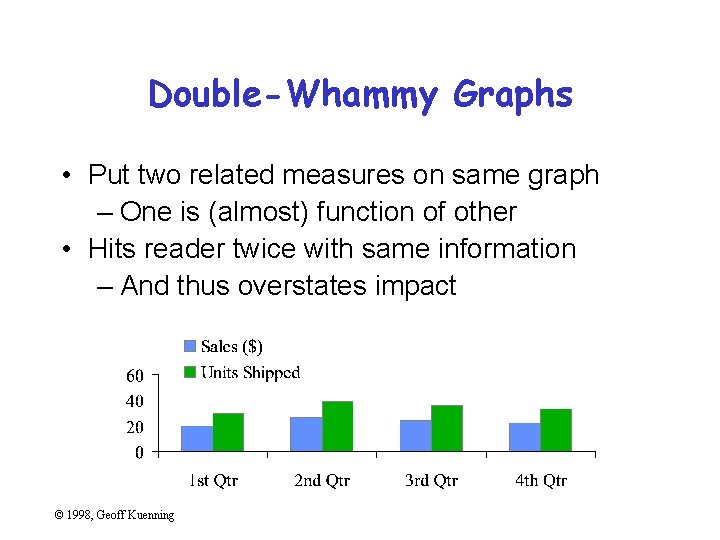

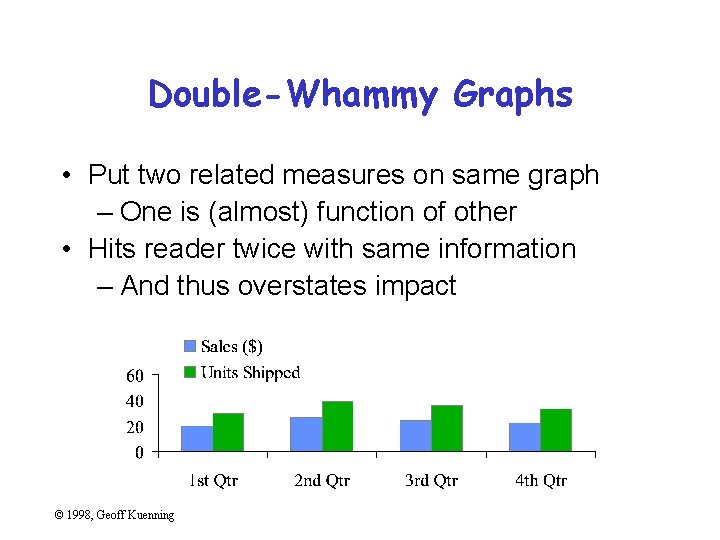

Double-Whammy Graphs • Put two related measures on same graph – One is (almost) function of other • Hits reader twice with same information – And thus overstates impact © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

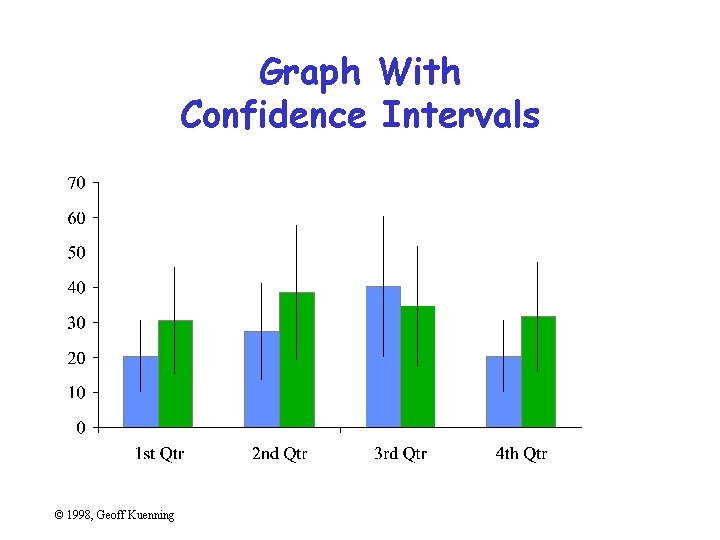

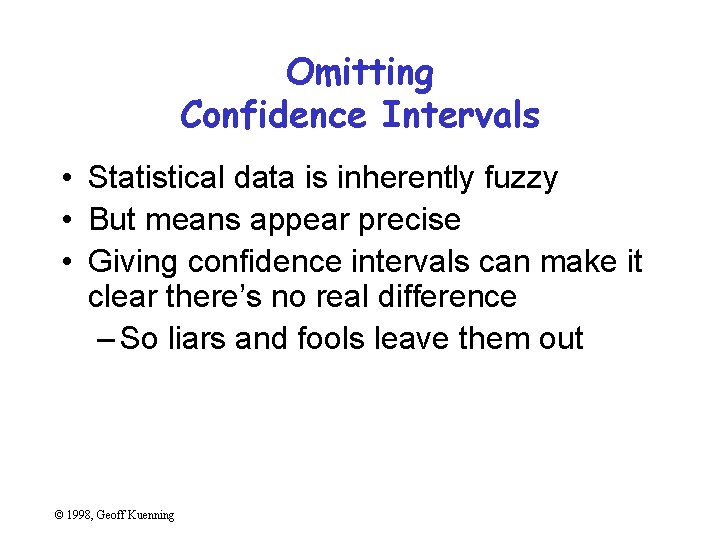

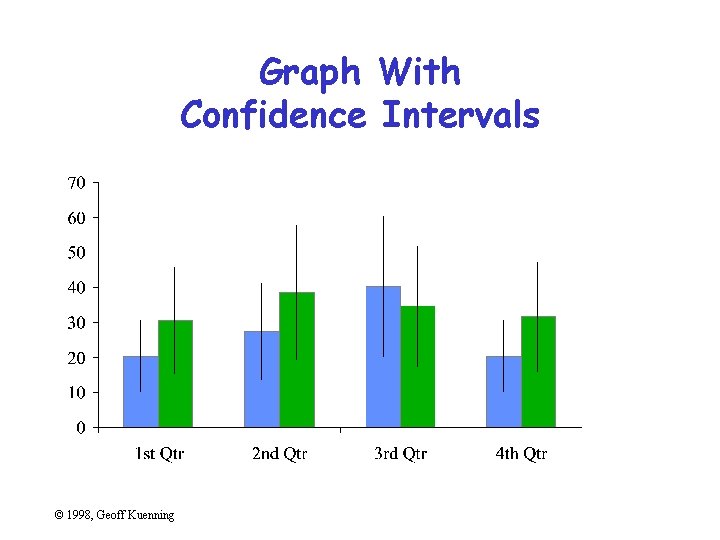

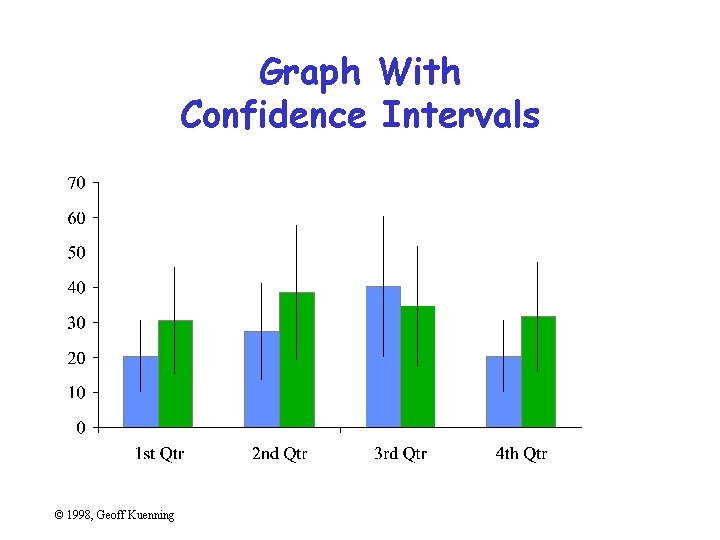

Omitting Confidence Intervals • Statistical data is inherently fuzzy • But means appear precise • Giving confidence intervals can make it clear there’s no real difference – So liars and fools leave them out © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

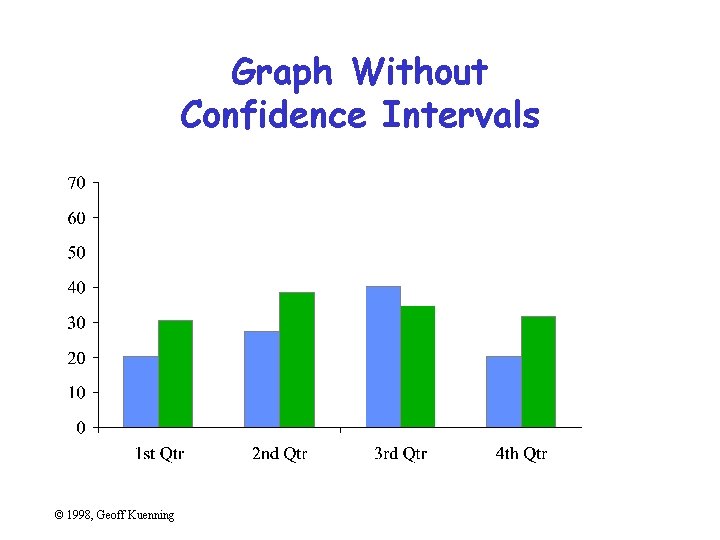

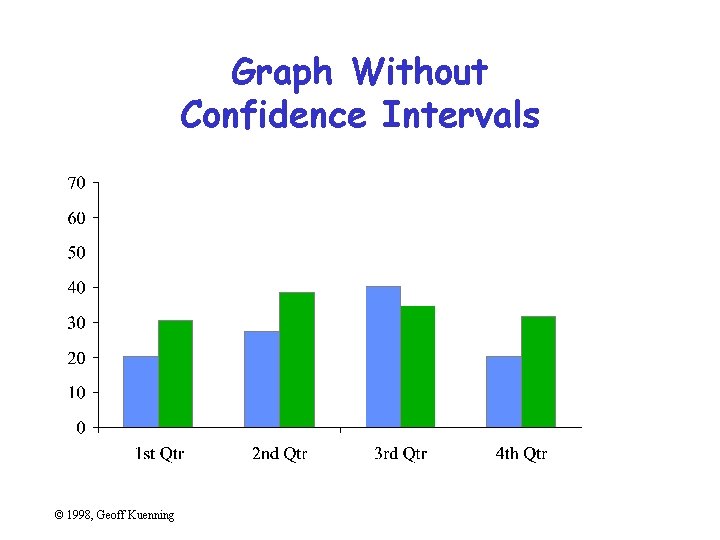

Graph Without Confidence Intervals © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

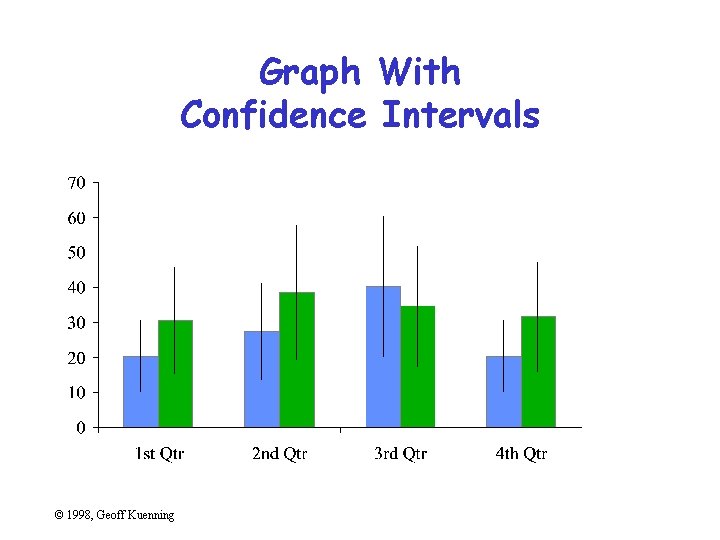

Graph With Confidence Intervals © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

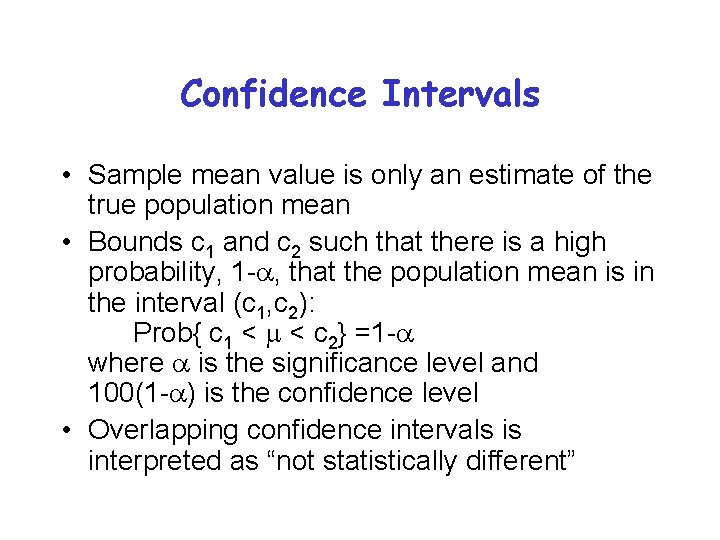

Confidence Intervals • Sample mean value is only an estimate of the true population mean • Bounds c 1 and c 2 such that there is a high probability, 1 -a, that the population mean is in the interval (c 1, c 2): Prob{ c 1 < m < c 2} =1 -a where a is the significance level and 100(1 -a) is the confidence level • Overlapping confidence intervals is interpreted as “not statistically different”

Graph With Confidence Intervals © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

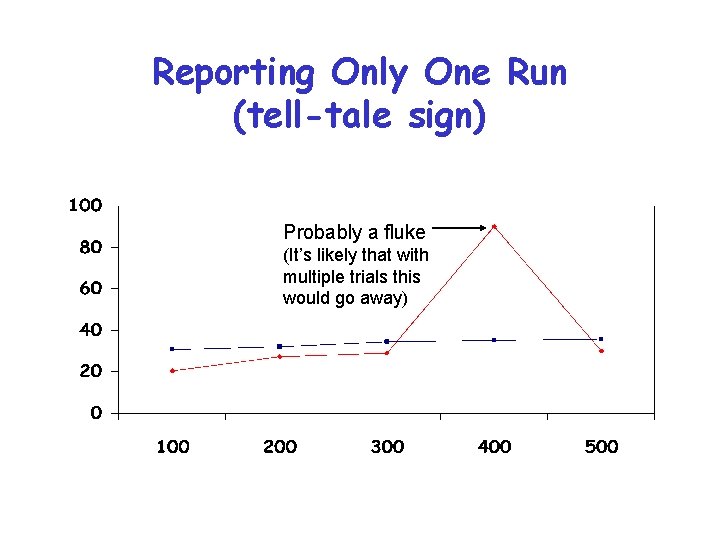

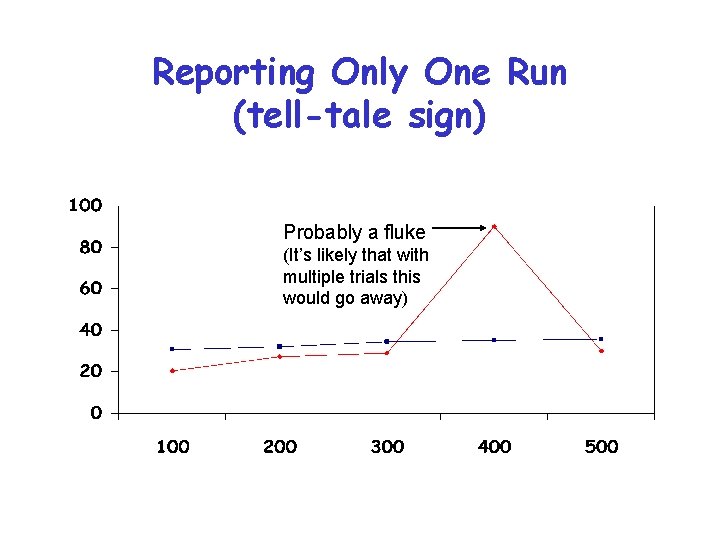

Reporting Only One Run (tell-tale sign) Probably a fluke (It’s likely that with multiple trials this would go away)

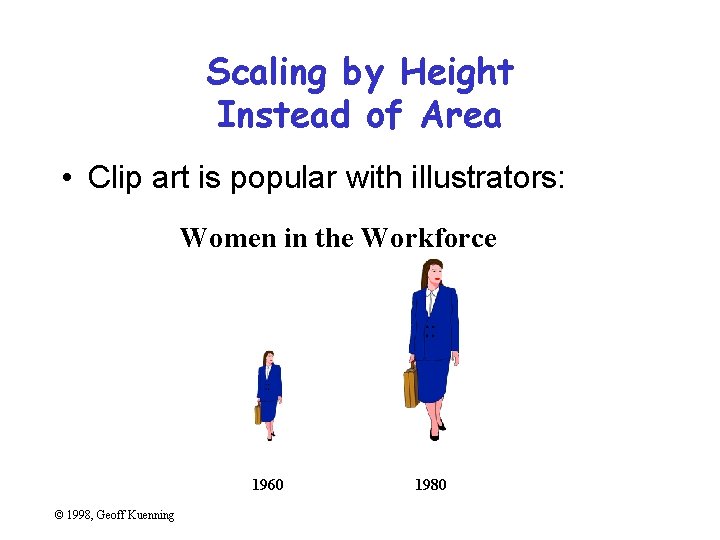

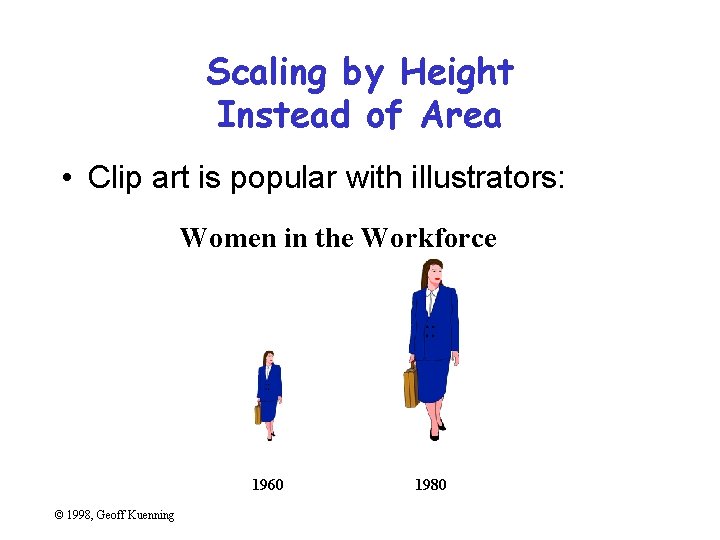

Scaling by Height Instead of Area • Clip art is popular with illustrators: Women in the Workforce 1960 © 1998, Geoff Kuenning 1980

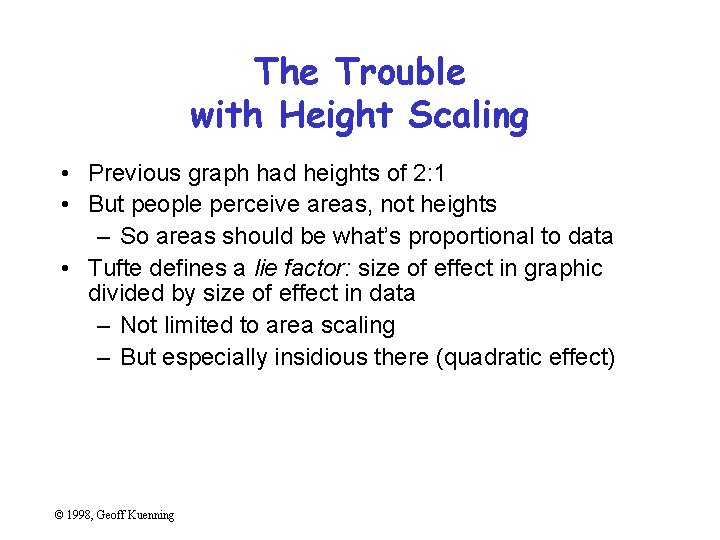

The Trouble with Height Scaling • Previous graph had heights of 2: 1 • But people perceive areas, not heights – So areas should be what’s proportional to data • Tufte defines a lie factor: size of effect in graphic divided by size of effect in data – Not limited to area scaling – But especially insidious there (quadratic effect) © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

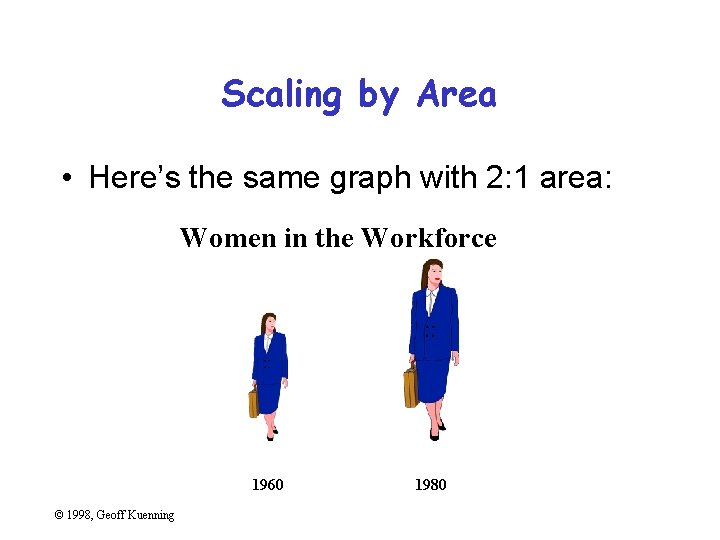

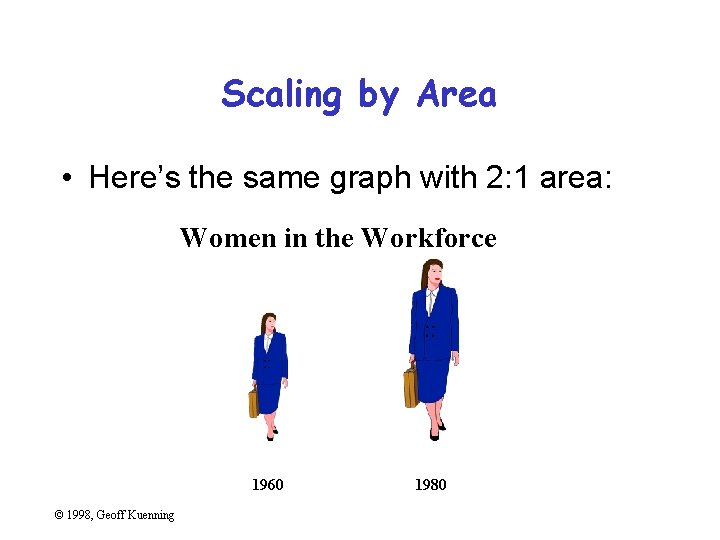

Scaling by Area • Here’s the same graph with 2: 1 area: Women in the Workforce 1960 © 1998, Geoff Kuenning 1980

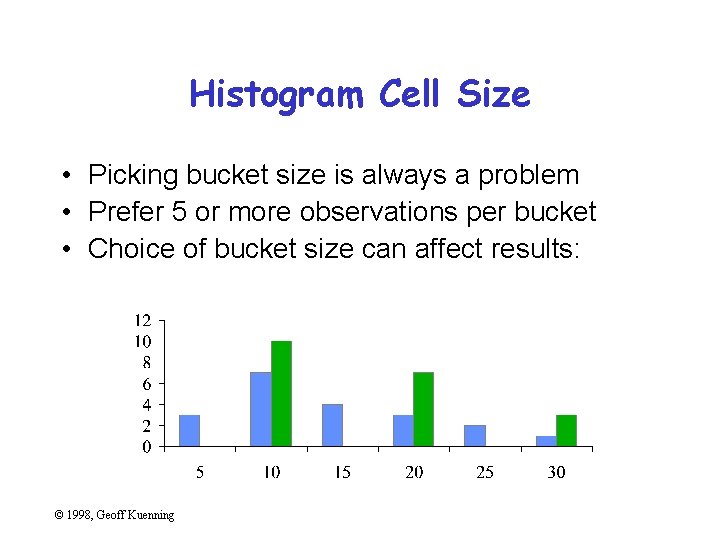

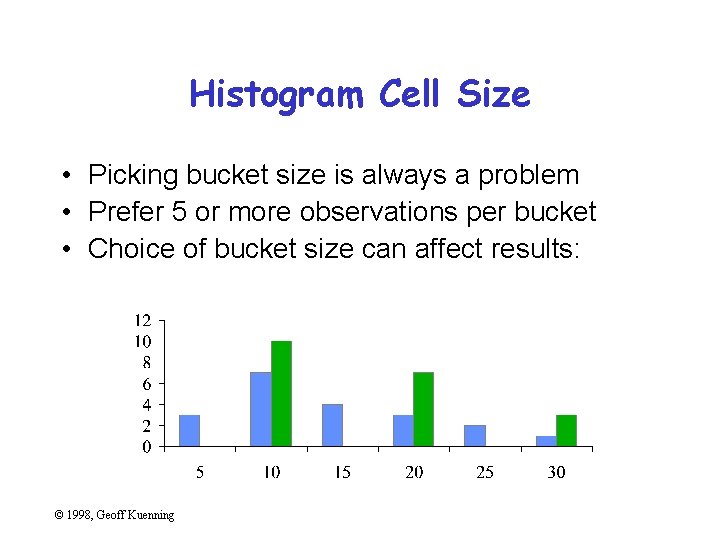

Histogram Cell Size • Picking bucket size is always a problem • Prefer 5 or more observations per bucket • Choice of bucket size can affect results: © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

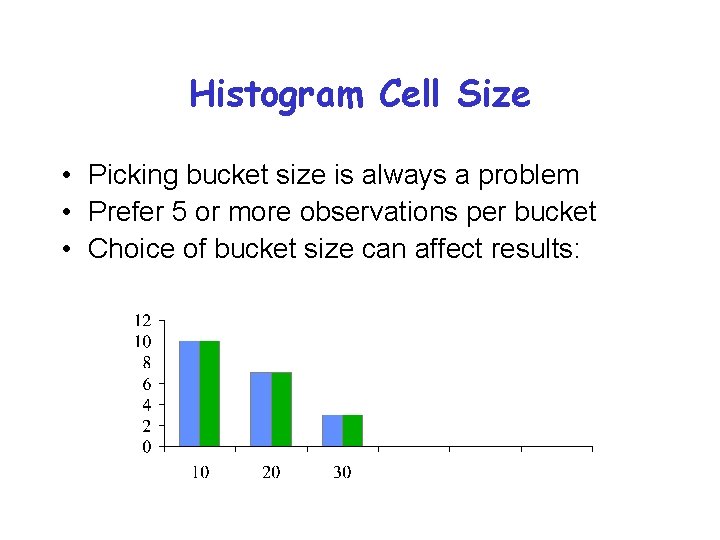

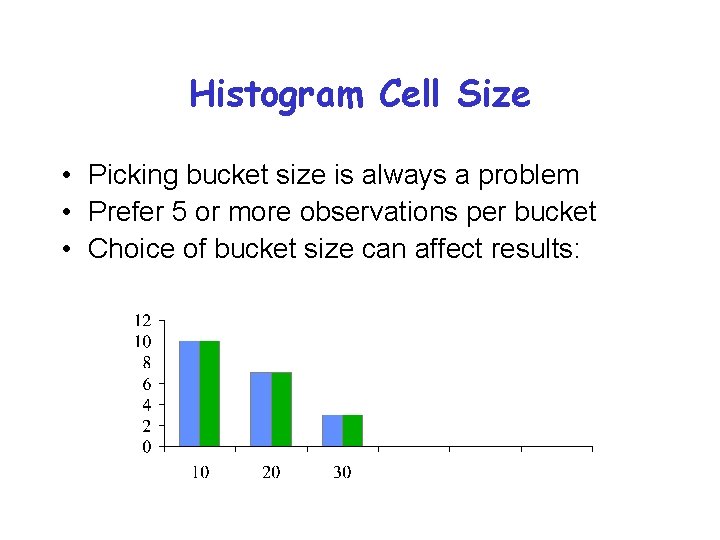

Histogram Cell Size • Picking bucket size is always a problem • Prefer 5 or more observations per bucket • Choice of bucket size can affect results:

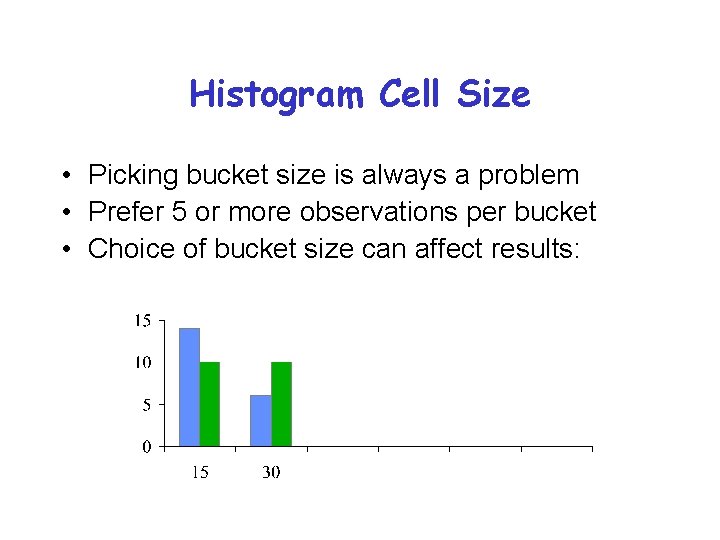

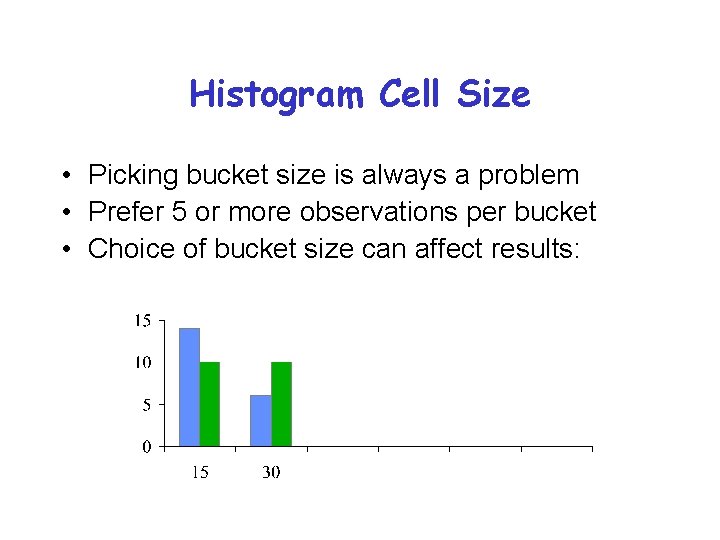

Histogram Cell Size • Picking bucket size is always a problem • Prefer 5 or more observations per bucket • Choice of bucket size can affect results:

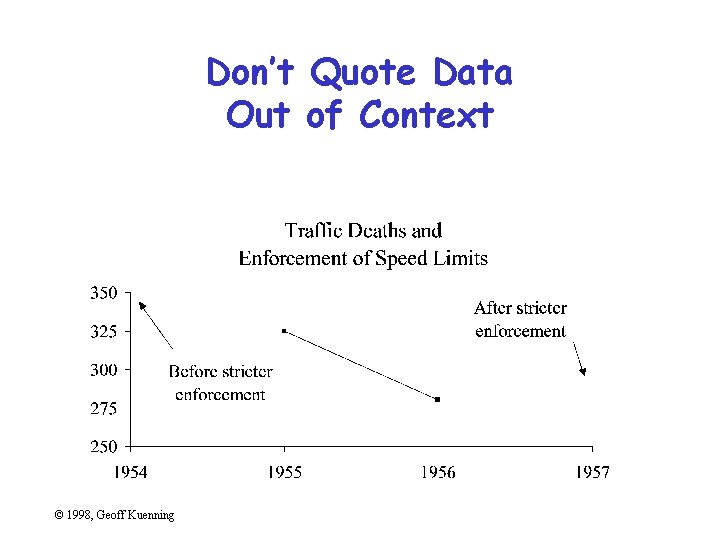

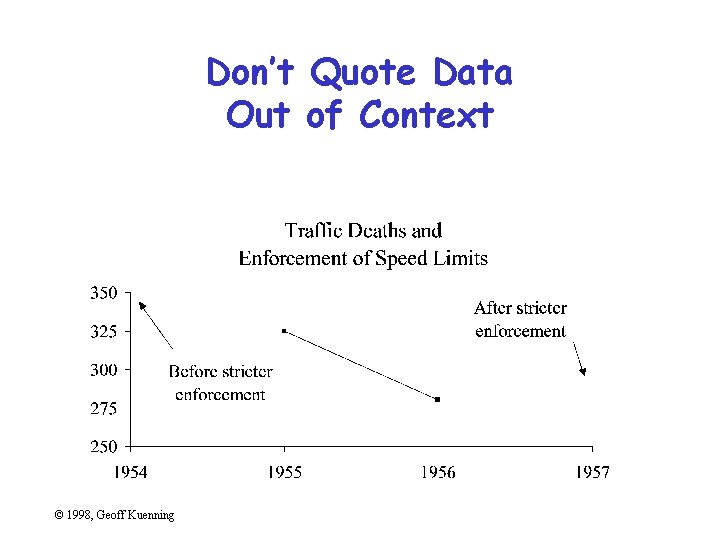

Don’t Quote Data Out of Context © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

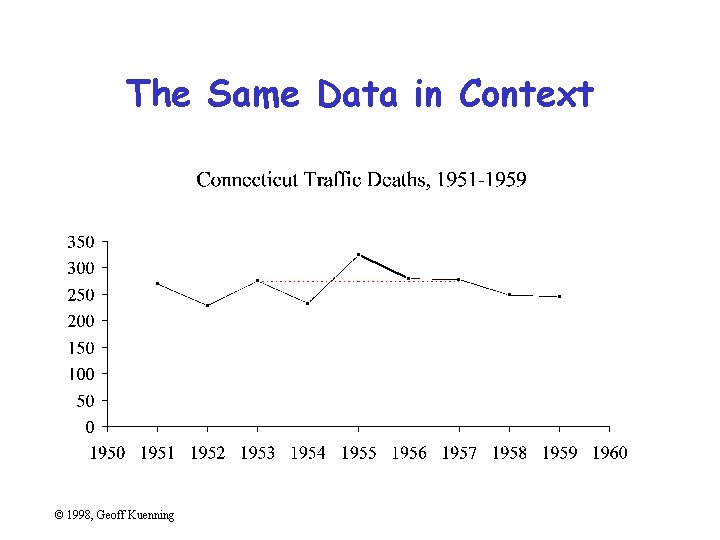

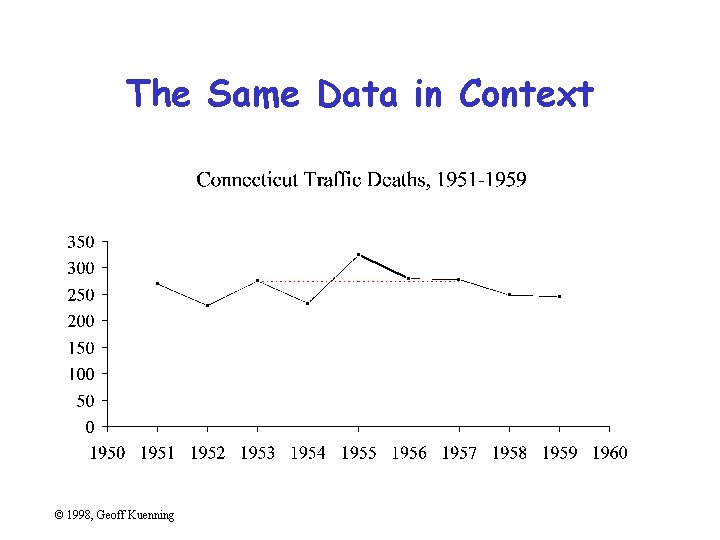

The Same Data in Context © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

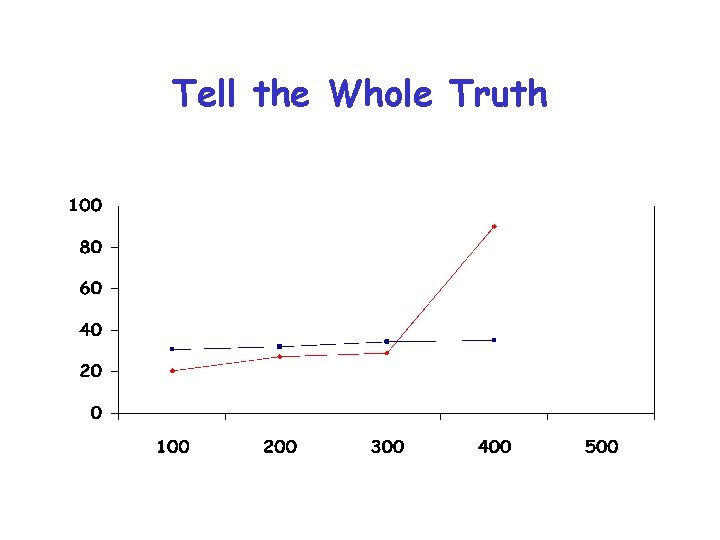

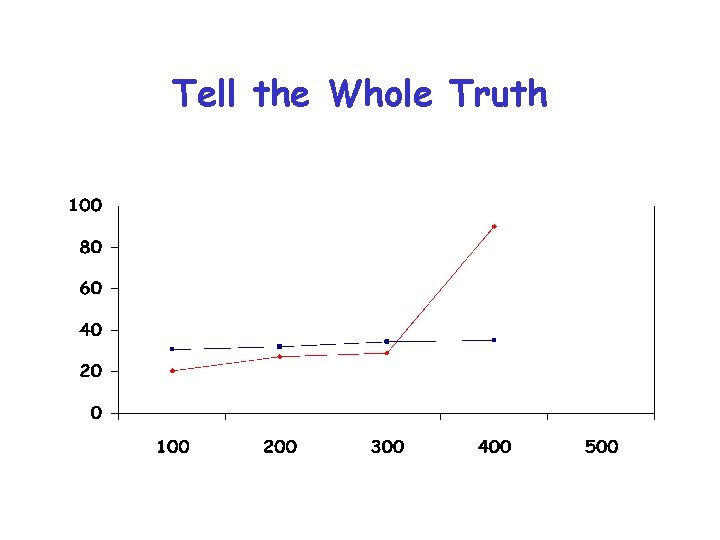

Tell the Whole Truth

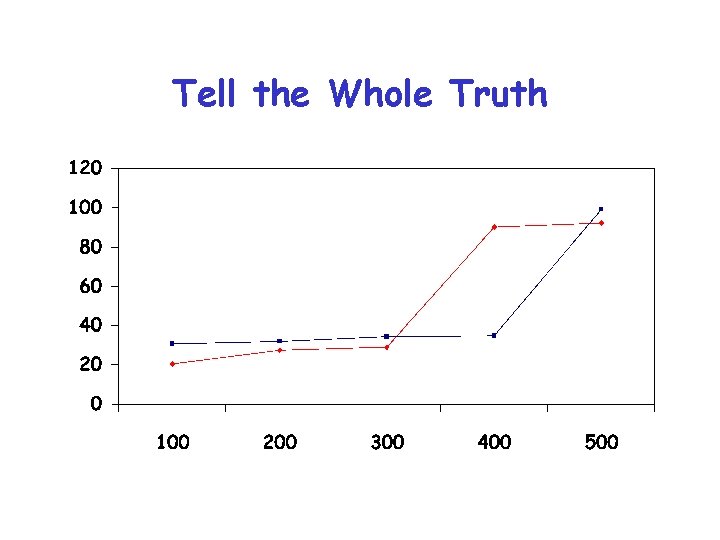

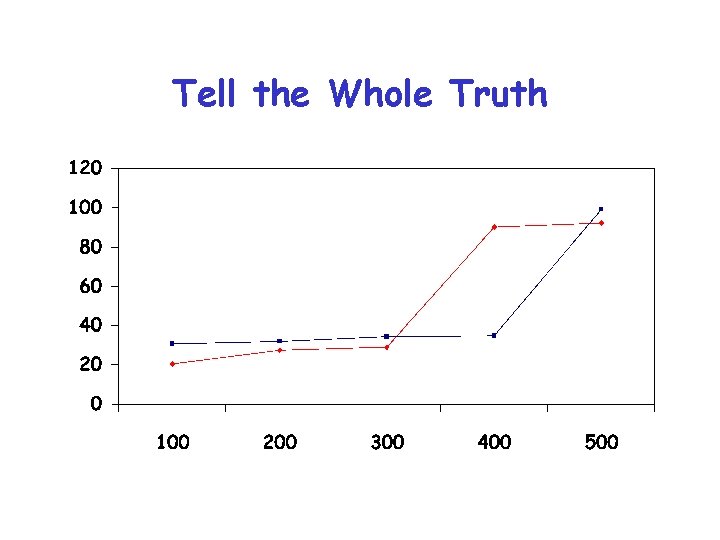

Tell the Whole Truth

Special-Purpose Charts • • Histograms Scatter plots Gantt charts Kiviat graphs © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

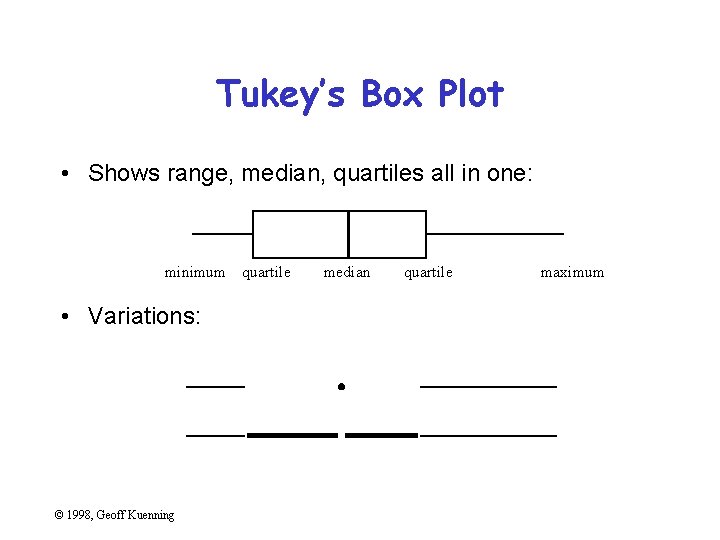

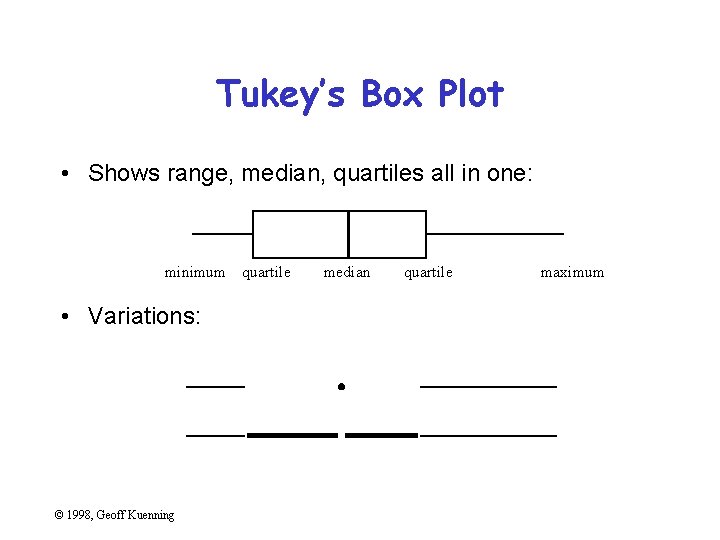

Tukey’s Box Plot • Shows range, median, quartiles all in one: minimum quartile • Variations: © 1998, Geoff Kuenning median quartile maximum

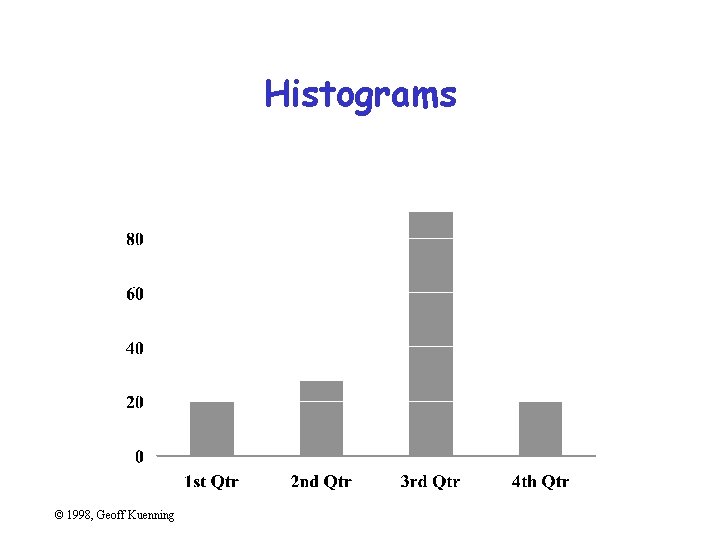

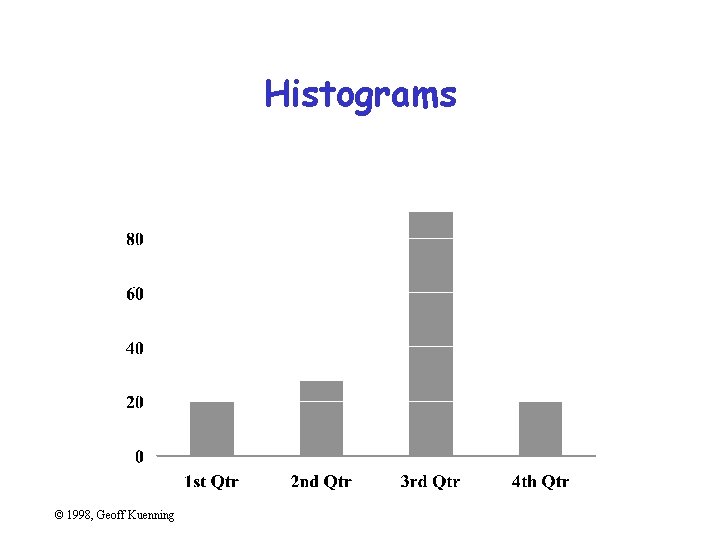

Histograms © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

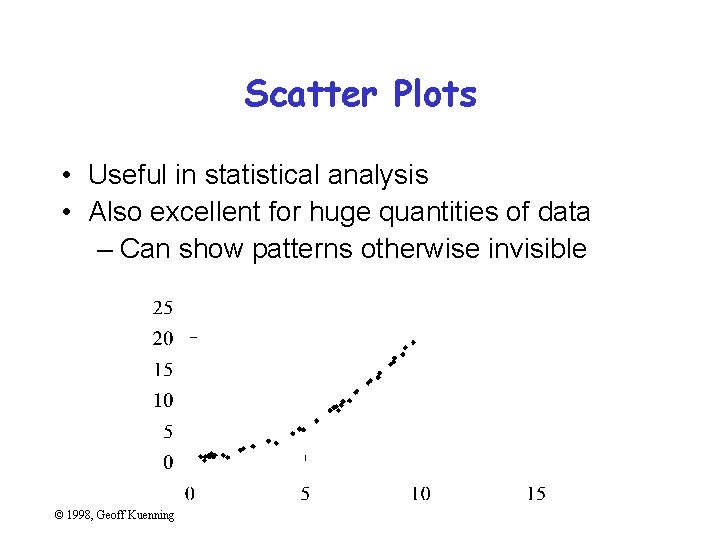

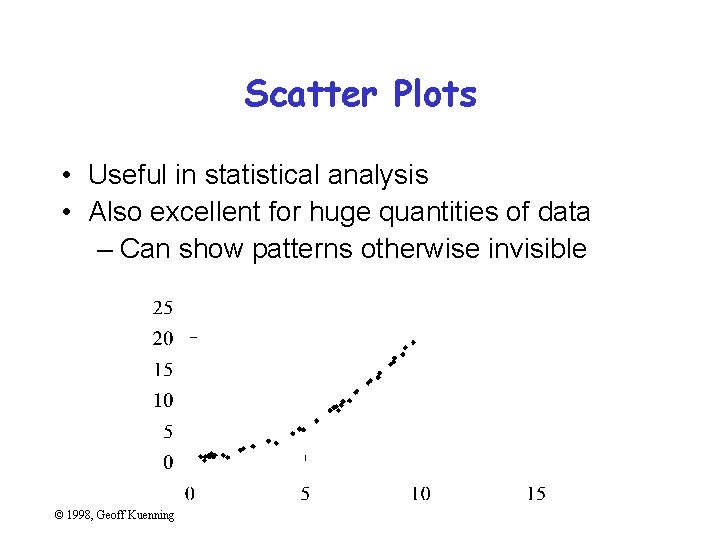

Scatter Plots • Useful in statistical analysis • Also excellent for huge quantities of data – Can show patterns otherwise invisible © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

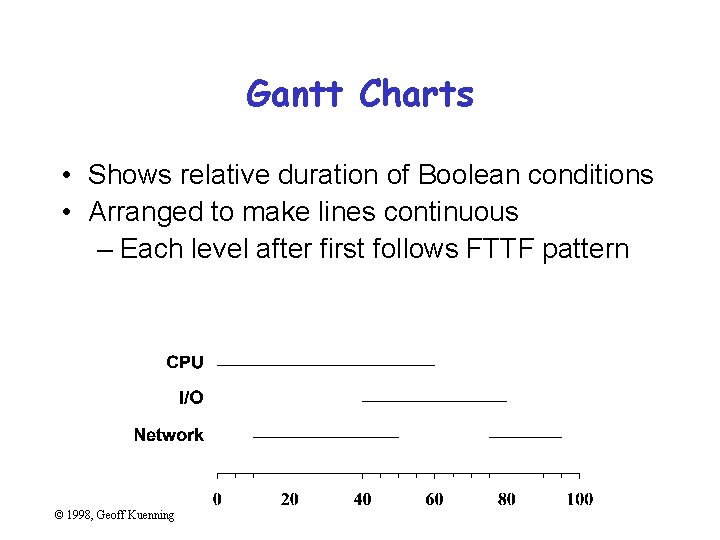

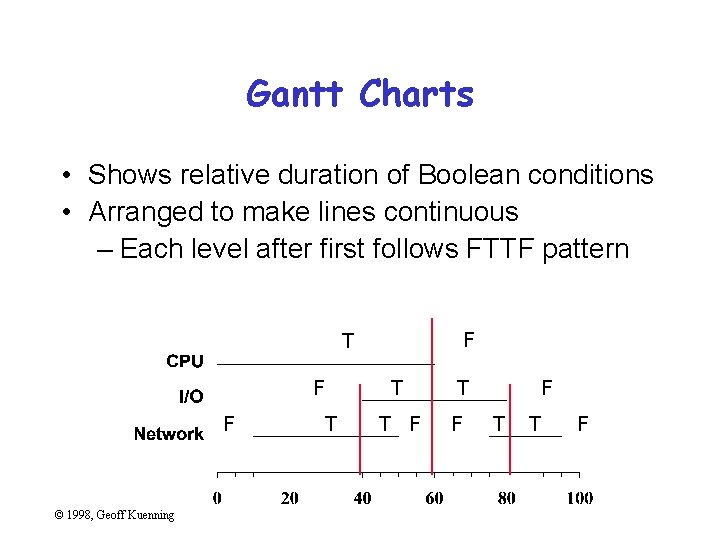

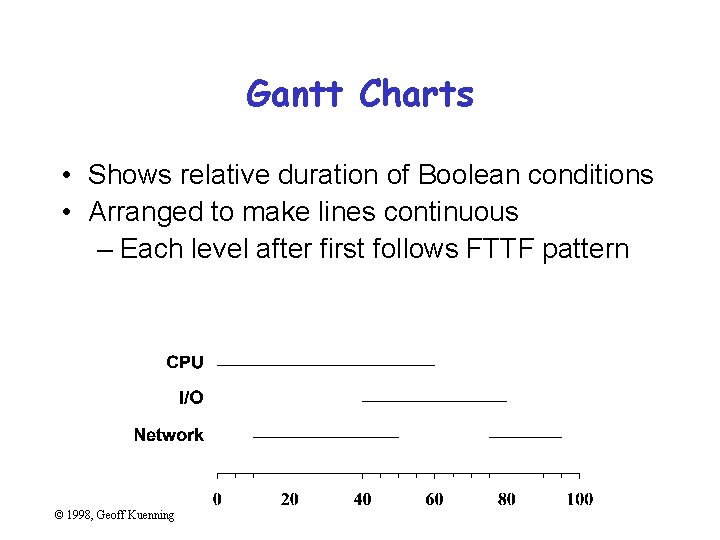

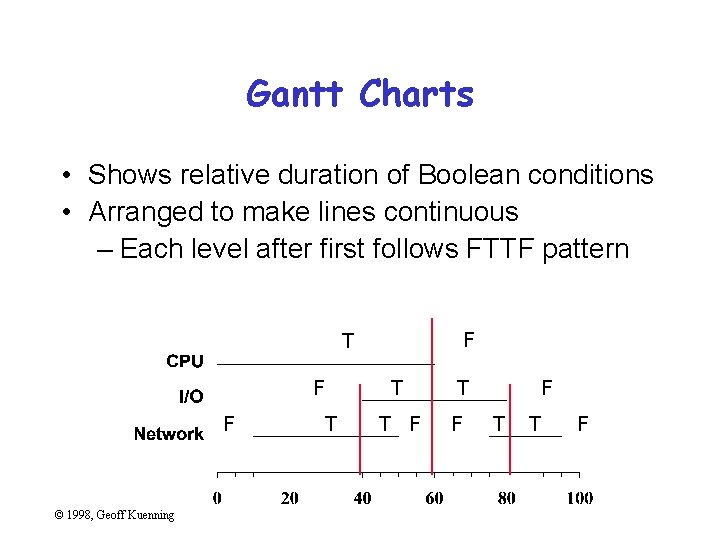

Gantt Charts • Shows relative duration of Boolean conditions • Arranged to make lines continuous – Each level after first follows FTTF pattern © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

Gantt Charts • Shows relative duration of Boolean conditions • Arranged to make lines continuous – Each level after first follows FTTF pattern F T F F © 1998, Geoff Kuenning T T F F F T T F

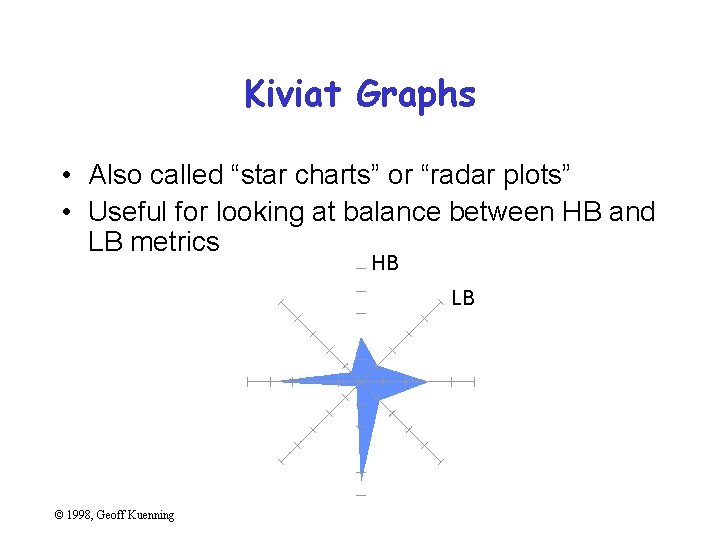

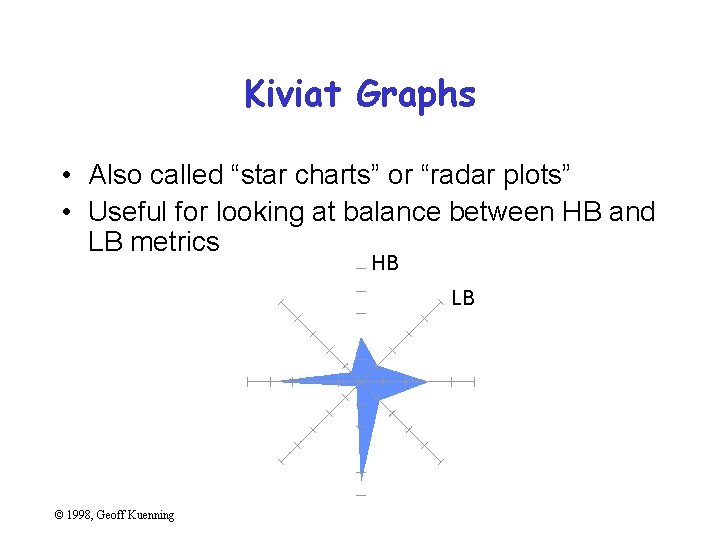

Kiviat Graphs • Also called “star charts” or “radar plots” • Useful for looking at balance between HB and LB metrics HB LB © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

Useful Reference Works • Edward R. Tufte, The Visual Display of Quantitative Information, Graphics Press, Cheshire, Connecticut, 1983. • Edward R. Tufte, Envisioning Information, Graphics Press, Cheshire, Connecticut, 1990. • Edward R. Tufte, Visual Explanations, Graphics Press, Cheshire, Connecticut, 1997. • Darrell Huff, How to Lie With Statistics, W. W. Norton & Co. , New York, 1954 © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

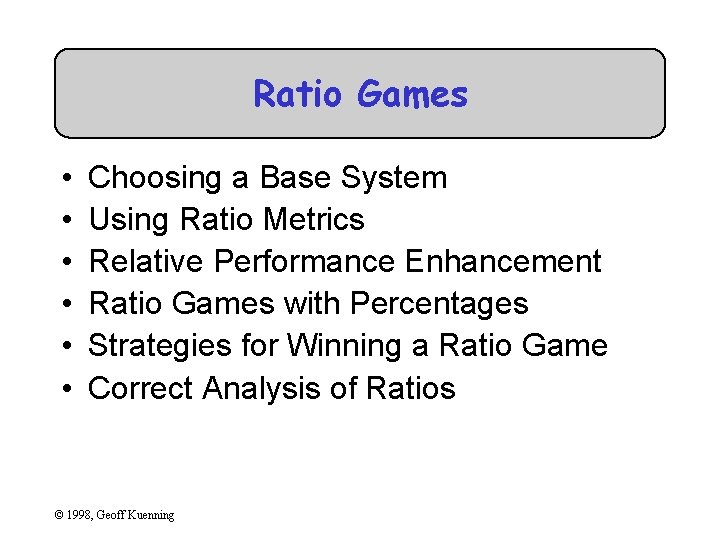

Ratio Games • • • Choosing a Base System Using Ratio Metrics Relative Performance Enhancement Ratio Games with Percentages Strategies for Winning a Ratio Game Correct Analysis of Ratios © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

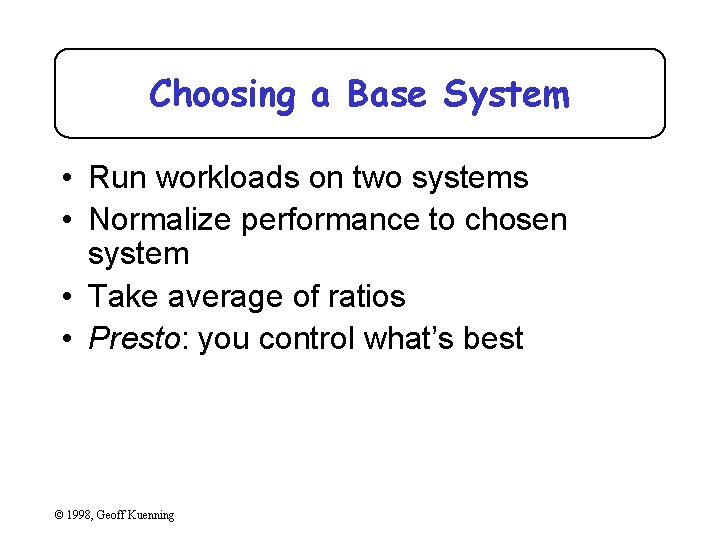

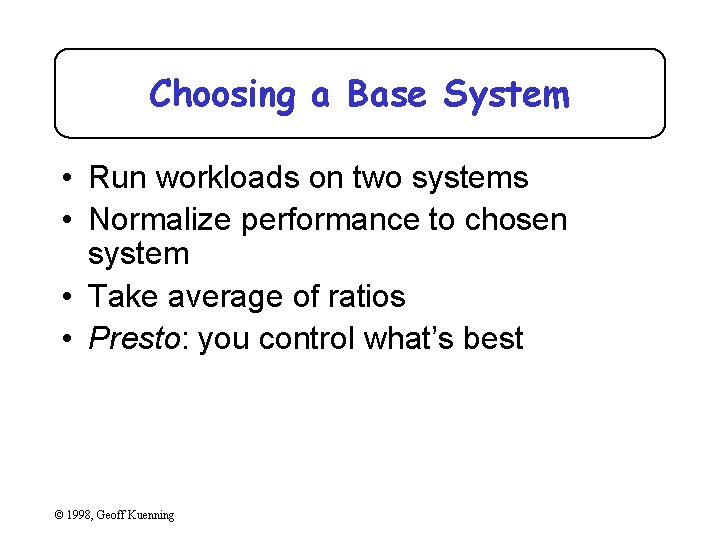

Choosing a Base System • Run workloads on two systems • Normalize performance to chosen system • Take average of ratios • Presto: you control what’s best © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

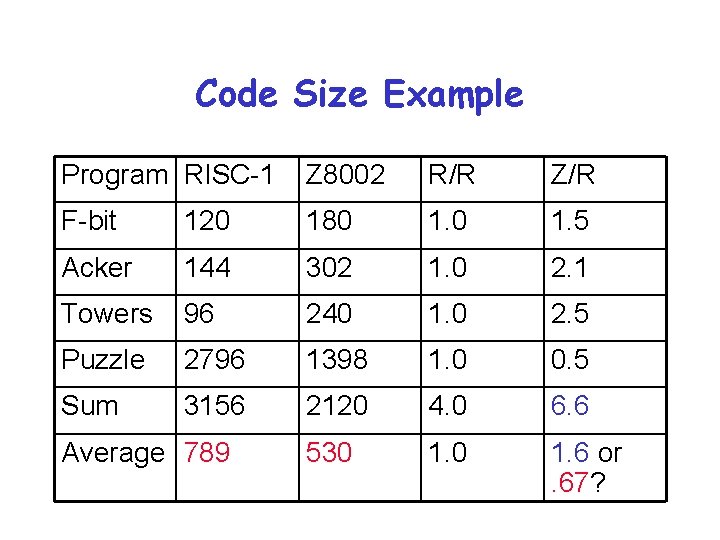

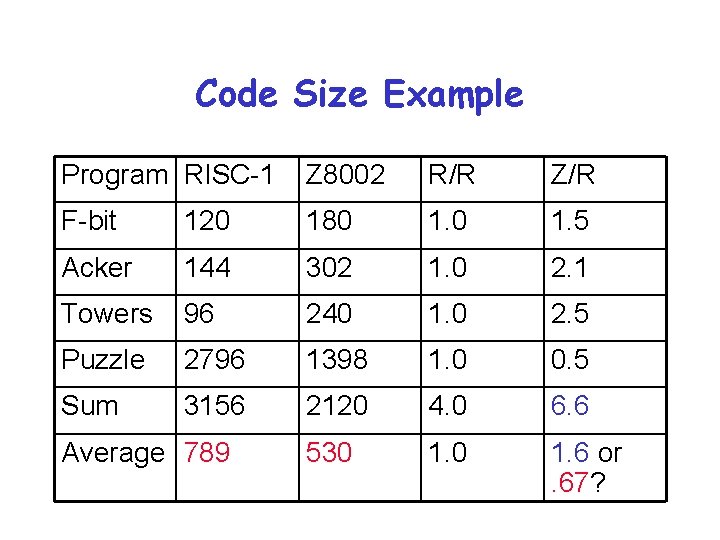

Code Size Example Program RISC-1 Z 8002 R/R Z/R F-bit 120 180 1. 5 Acker 144 302 1. 0 2. 1 Towers 96 240 1. 0 2. 5 Puzzle 2796 1398 1. 0 0. 5 Sum 3156 2120 4. 0 6. 6 530 1. 6 or. 67? Average 789

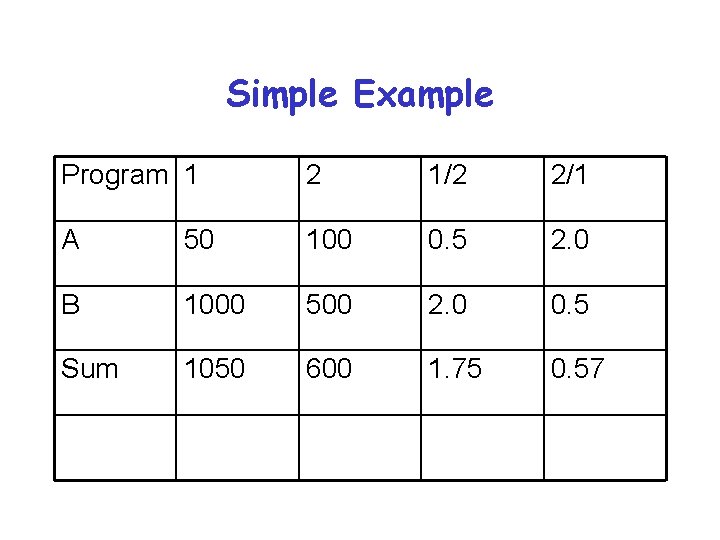

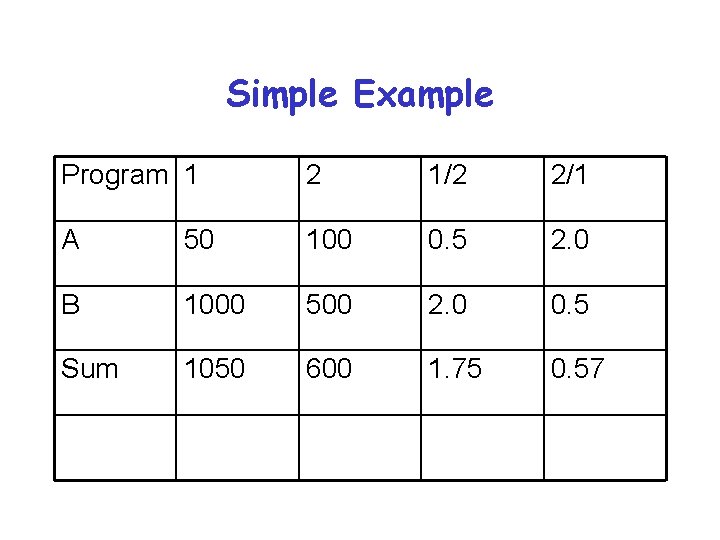

Simple Example Program 1 2 1/2 2/1 A 50 100 0. 5 2. 0 B 1000 500 2. 0 0. 5 Sum 1050 600 1. 75 0. 57

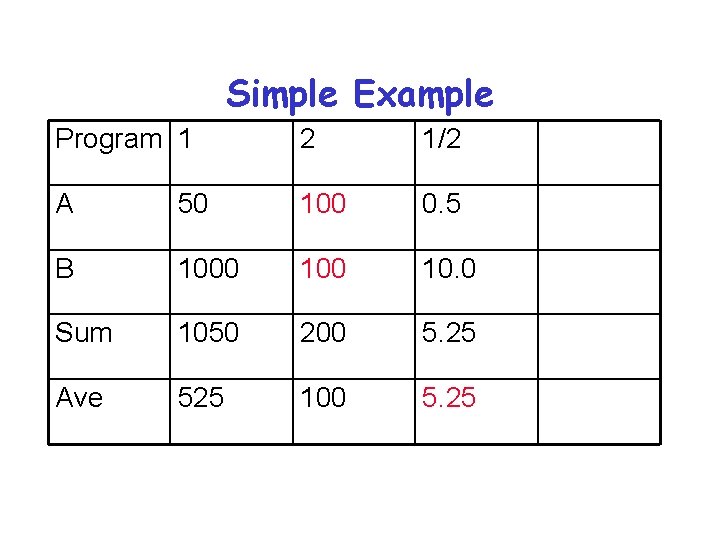

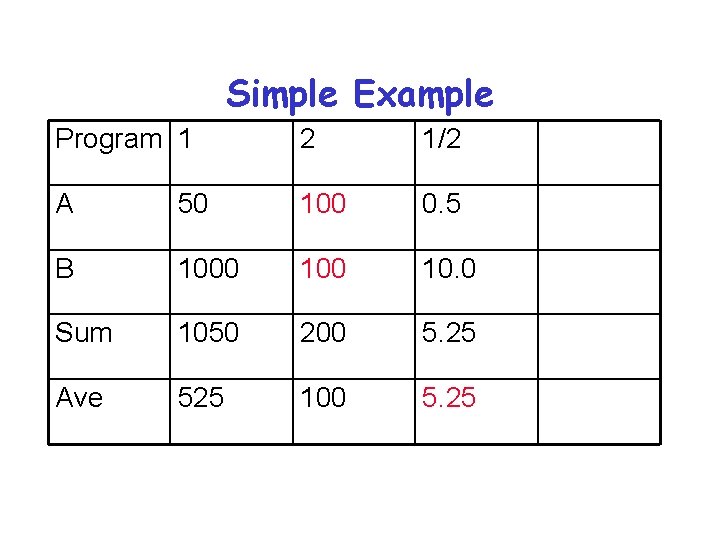

Simple Example Program 1 2 1/2 A 50 100 0. 5 B 1000 10. 0 Sum 1050 200 5. 25 Ave 525 100 5. 25

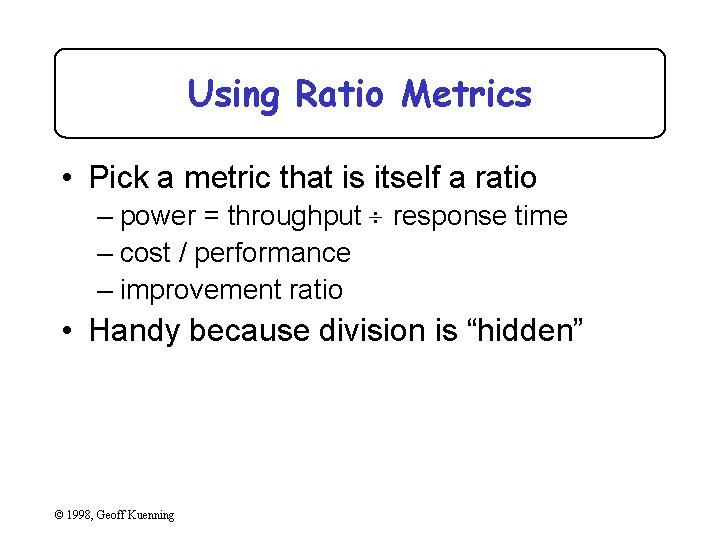

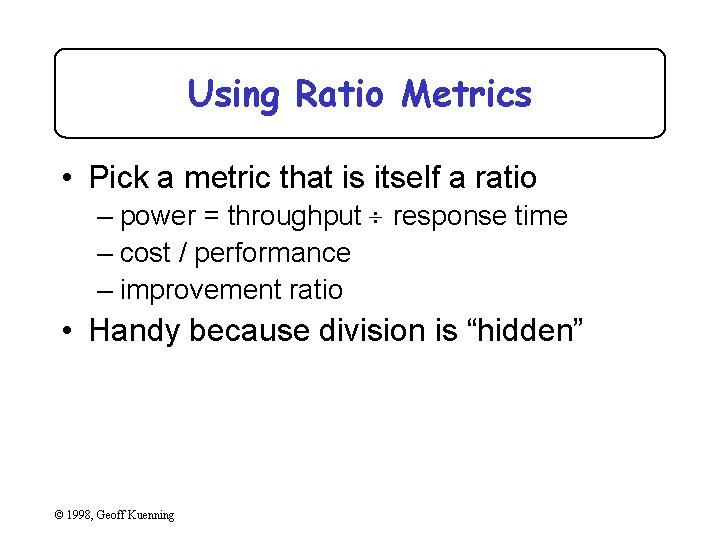

Using Ratio Metrics • Pick a metric that is itself a ratio – power = throughput response time – cost / performance – improvement ratio • Handy because division is “hidden” © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

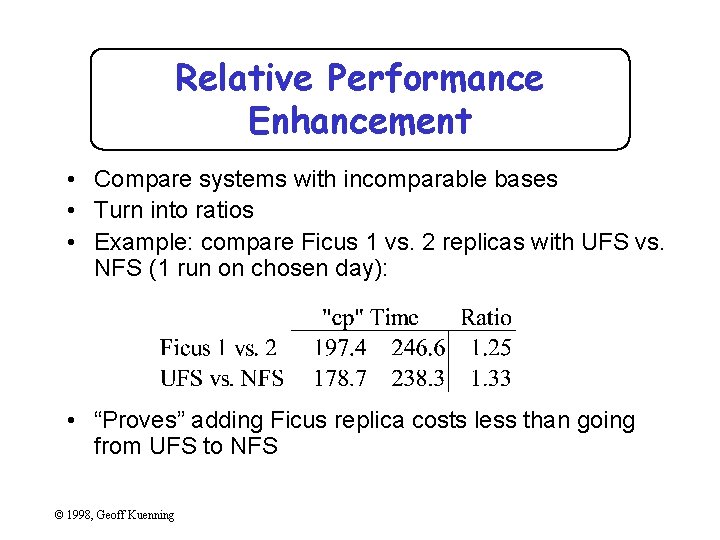

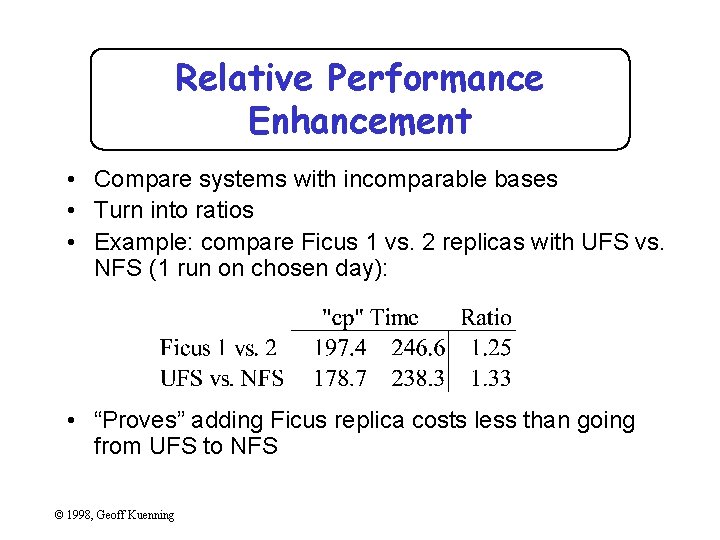

Relative Performance Enhancement • Compare systems with incomparable bases • Turn into ratios • Example: compare Ficus 1 vs. 2 replicas with UFS vs. NFS (1 run on chosen day): • “Proves” adding Ficus replica costs less than going from UFS to NFS © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

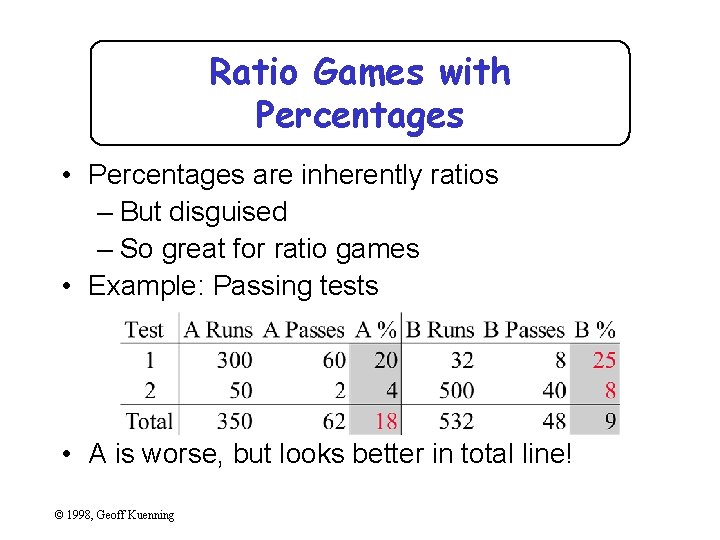

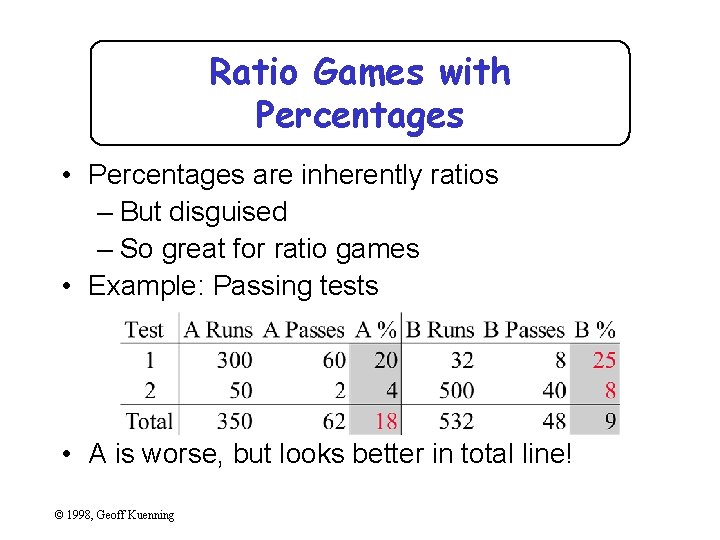

Ratio Games with Percentages • Percentages are inherently ratios – But disguised – So great for ratio games • Example: Passing tests • A is worse, but looks better in total line! © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

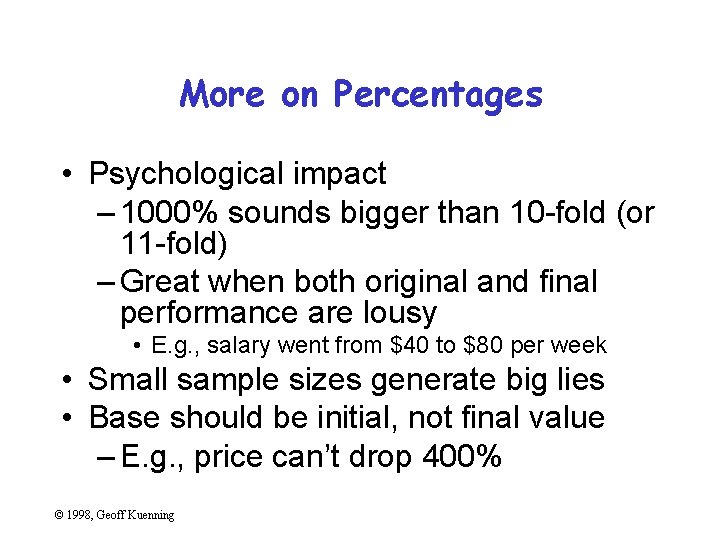

More on Percentages • Psychological impact – 1000% sounds bigger than 10 -fold (or 11 -fold) – Great when both original and final performance are lousy • E. g. , salary went from $40 to $80 per week • Small sample sizes generate big lies • Base should be initial, not final value – E. g. , price can’t drop 400% © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

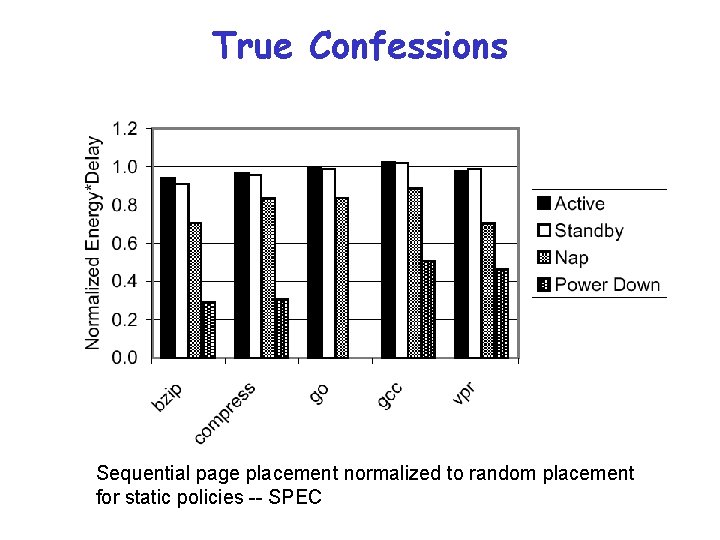

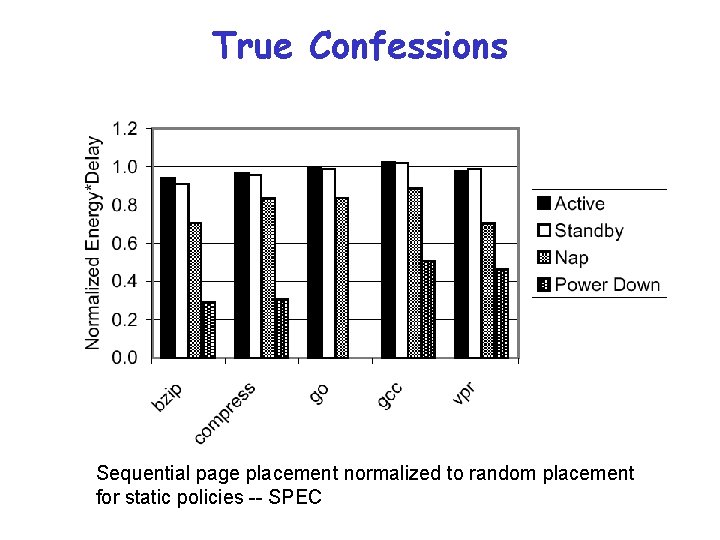

True Confessions Sequential page placement normalized to random placement for static policies -- SPEC

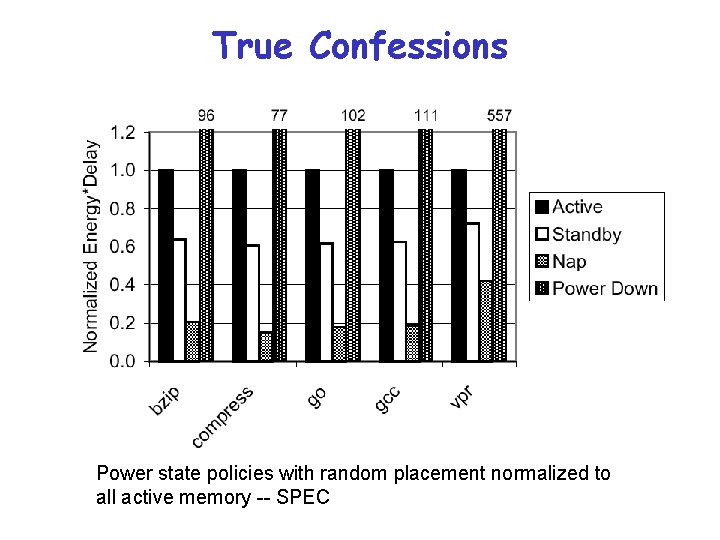

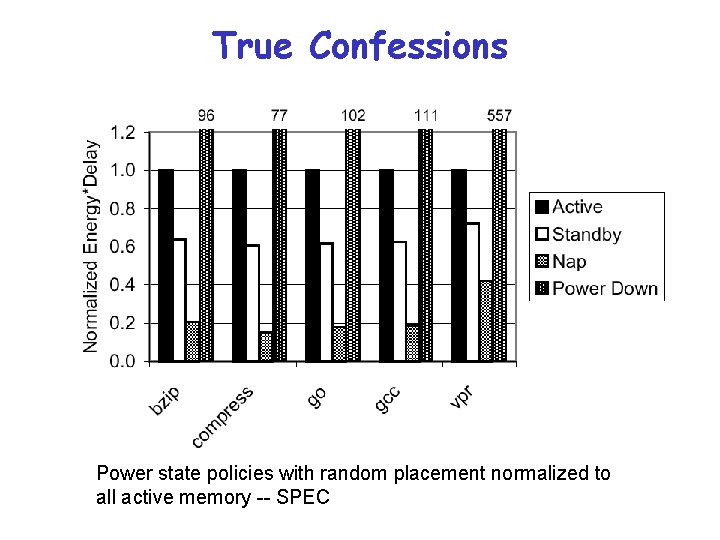

True Confessions Power state policies with random placement normalized to all active memory -- SPEC

Strategies for Winning a Ratio Game • Can you win? • How to win © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

Can You Win the Ratio Game? • If one system is better by all measures, a ratio game won’t work – But recall percent-passes example – And selecting the base lets you change the magnitude of the difference • If each system wins on some measures, ratio games might be possible (but no promises) – May have to try all bases © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

How to Win Your Ratio Game • For LB metrics, use your system as the base • For HB metrics, use the other as a base • If possible, adjust lengths of benchmarks – Elongate when your system performs best – Short when your system is worst – This gives greater weight to your strengths © 1998, Geoff Kuenning

For Discussion Next Tuesday • Bring in one either notoriously bad or exceptionally good example of data presentation from your proceedings. The bad ones are more fun. Or if you find something just really different, please show it.