Colonial Latin American Life and the Movement Towards

- Slides: 27

Colonial Latin American Life and the Movement Towards Independence 1550 to 1830

Latin America Under Spanish Rule � Native American Populations were devastated by European contact. Some estimate that the population in the Central Aztec Empire was around 19 million before the arrival of the Spanish: it had dropped to 2 million by 1550. Native populations on Cuba and Hispaniola were all but wiped out, and every native population in the New World suffered some loss. Although the bloody conquest took its toll, the main culprits were diseases like smallpox. The natives had no natural defenses against these new diseases, which killed them far more efficiently than the conquistadors ever could. Overall the Genocide of native peoples would reach 100 million. � Under Spanish rule, native religion and culture were severely repressed. Whole libraries of native Codices were burned by Roman Catholic Priests who thought that they were the work of the Devil. Only a handful of these artifacts remain. The ancient cultures of the Maya and Aztecs were almost lost to history due to the systematic destruction of their art, architecture and writings. � Before the arrival of the Spanish, Latin American cultures had existing power structures, mostly based on castes and nobility. These were shattered, as the Europeans killed off the most powerful leaders and stripped the lesser nobility and priests of rank and wealth. The loss of the upper classes contributed directly to the weakening of native populations as a whole. � The Spanish and Portuguese colonists who arrived after the conquistadors wanted to follow in their footsteps. They did not come to build, farm or ranch, in fact farming was considered a very lowly profession among the colonists. These men therefore harshly exploited native labor, often without thinking about the long-term. This attitude severely stunted the economic and cultural growth of the region.

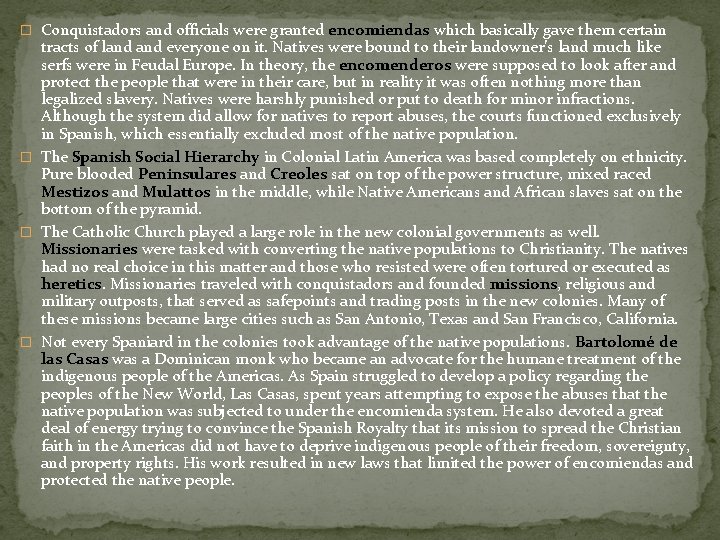

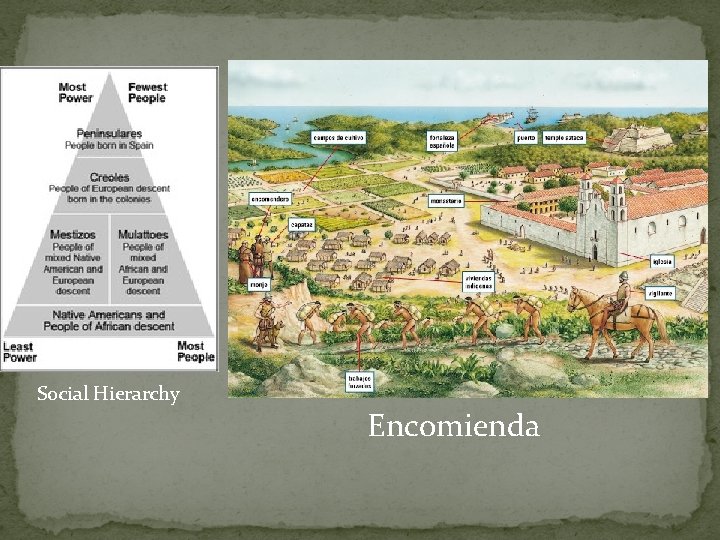

� Conquistadors and officials were granted encomiendas which basically gave them certain tracts of land everyone on it. Natives were bound to their landowner’s land much like serfs were in Feudal Europe. In theory, the encomenderos were supposed to look after and protect the people that were in their care, but in reality it was often nothing more than legalized slavery. Natives were harshly punished or put to death for minor infractions. Although the system did allow for natives to report abuses, the courts functioned exclusively in Spanish, which essentially excluded most of the native population. � The Spanish Social Hierarchy in Colonial Latin America was based completely on ethnicity. Pure blooded Peninsulares and Creoles sat on top of the power structure, mixed raced Mestizos and Mulattos in the middle, while Native Americans and African slaves sat on the bottom of the pyramid. � The Catholic Church played a large role in the new colonial governments as well. Missionaries were tasked with converting the native populations to Christianity. The natives had no real choice in this matter and those who resisted were often tortured or executed as heretics. Missionaries traveled with conquistadors and founded missions, religious and military outposts, that served as safepoints and trading posts in the new colonies. Many of these missions became large cities such as San Antonio, Texas and San Francisco, California. � Not every Spaniard in the colonies took advantage of the native populations. Bartolomé de las Casas was a Dominican monk who became an advocate for the humane treatment of the indigenous people of the Americas. As Spain struggled to develop a policy regarding the peoples of the New World, Las Casas, spent years attempting to expose the abuses that the native population was subjected to under the encomienda system. He also devoted a great deal of energy trying to convince the Spanish Royalty that its mission to spread the Christian faith in the Americas did not have to deprive indigenous people of their freedom, sovereignty, and property rights. His work resulted in new laws that limited the power of encomiendas and protected the native people.

Social Hierarchy Encomienda

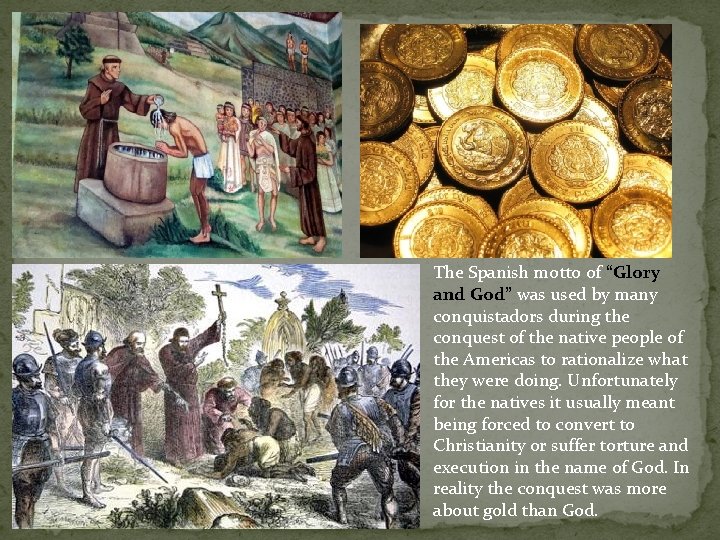

The Spanish motto of “Glory and God” was used by many conquistadors during the conquest of the native people of the Americas to rationalize what they were doing. Unfortunately for the natives it usually meant being forced to convert to Christianity or suffer torture and execution in the name of God. In reality the conquest was more about gold than God.

Bartolomé de las Casas

Bartolomé de las Casas tried to prevent the torture and mistreatment of Native peoples. In doing so, he became one of the first modern era civil rights activists.

� Plantations, large commercial farms, became a major financial factor in the Spanish colonies � � in the late 1500’s. Cash crops such as sugar, tobacco, cotton and coffee, generated enormous wealth for Spanish landowners. The landlords were faced with a labor problem however. Many natives had died of disease and this limited the workforce. The answer to this problem would come in the form of African Slavery. The sale of African slaves to the American Colonies became a part of daily life. The Triangular trade from Africa to Latin America then to Europe, created a dependence on slave labor. The cash crops of the plantations required intense labor and the demand for the resources in Europe only grew with time. The introduction of African Slaves only made life for the Natives worse as they no longer held any value to their Spanish masters. The harsh treatment of the native population led to numerous uprisings against Spanish authority. After the conquest of northern New Mexico by Juan de Oñate, Spanish authorities systematically subjugated the inhabitants of the Pueblos. (small Native settlements) Indians who had lived and worshiped independently for centuries were forced to abandon their religions, adopt Christianity, and pay tribute to Spanish rulers. Resistance to Spanish rule was met with imprisonment, torture, and amputations. After three generations of oppression the Pueblo Indians rose up to overthrow the Spanish. A religious leader named Popay secretly organized a widespread rebellion. On the night of August 10, 1680, Indians in more than two dozen pueblos simultaneously attacked the Spanish authorities. A force of 2, 500 Indian warriors sacked and burned the colonial headquarters in Santa Fe. Indian fighters had killed more than 400 Spanish soldiers and civilians and had driven the surviving Europeans back to El Paso. The Indian leaders then restored their own religious institutions and set up a government that lasted until 1692. The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 was the single most successful act of resistance by Native Americans against a European invader. It established Indian independence in the pueblos for more than a decade, and even after Spanish domination was re-imposed it forced the imperial authorities to observe religious tolerance.

� Jacinto Canek, a convent-educated Maya, led an indigenous rebellion against the government in 1761. The fighting resulted in the deaths of thousands of natives and the execution of Canek in the city of Mérida. Although his revolt failed, it inspired other indigenous revolts during the colonial period and gave the Yucatán’s natives the reputation of being fierce and difficult-to-conquer warriors. � The outbreak of violence among the Native people forced the Viceroyalties of the colonies to pass strict laws on its citizens. Spain began to tighten its control on the colonies as well fearing they were on the verge of open rebellion. During the reign of Charles III (1759 -88), Spain introduced important reforms at home and in the colonies. To modernize Mexico, higher taxes and more direct military control seemed to be necessary; to effect these changes, the government reorganized the political structure of New Spain into twelve districts or intendencias , each headed by an governor and a general in Mexico City, who was independent of the viceroy and reported directly to the king. � The reforms not only angered the natives but negatively effected the creoles as well. The new laws benefited the peninsulare class and gave them the best jobs in the viceroyalties. Creoles became second-class citizens with limited rights. The marginalization of the creoles would create a liberation movement against Spanish oppression led by well educated creoles and made up of natives, mestizos, mulattos and Africans.

Pueblo Revolt of 1680

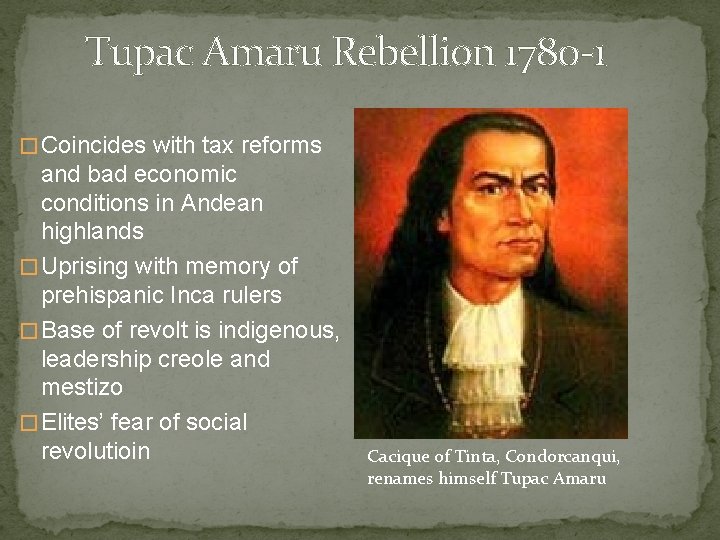

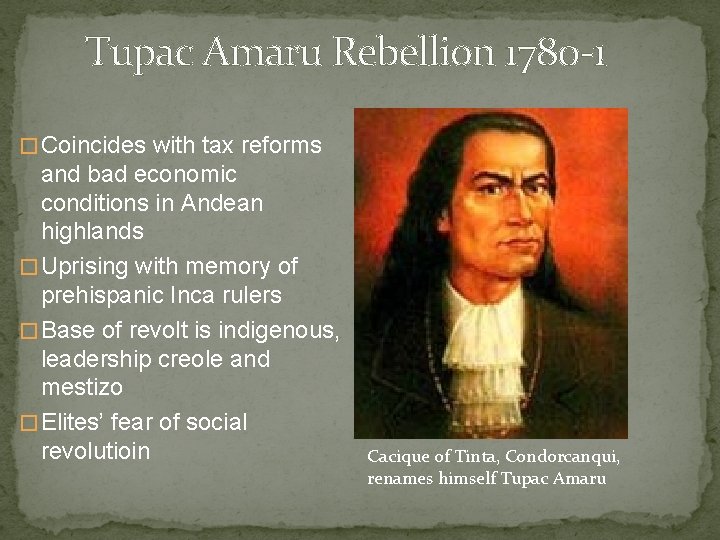

Tupac Amaru Rebellion 1780 -1 � Coincides with tax reforms and bad economic conditions in Andean highlands � Uprising with memory of prehispanic Inca rulers � Base of revolt is indigenous, leadership creole and mestizo � Elites’ fear of social revolutioin Cacique of Tinta, Condorcanqui, renames himself Tupac Amaru

Comunero Revolt, New Granada 1781 � Revolt by Creoles against increased taxes and new economic monopolies excluding them, still loyal to Spanish crown but protest against specific wrongs � Government conceded to demands if rebels disbanded � Use of military force and only a few executions � No general revulsion against dissent, pardoned Creoles return to civilian life

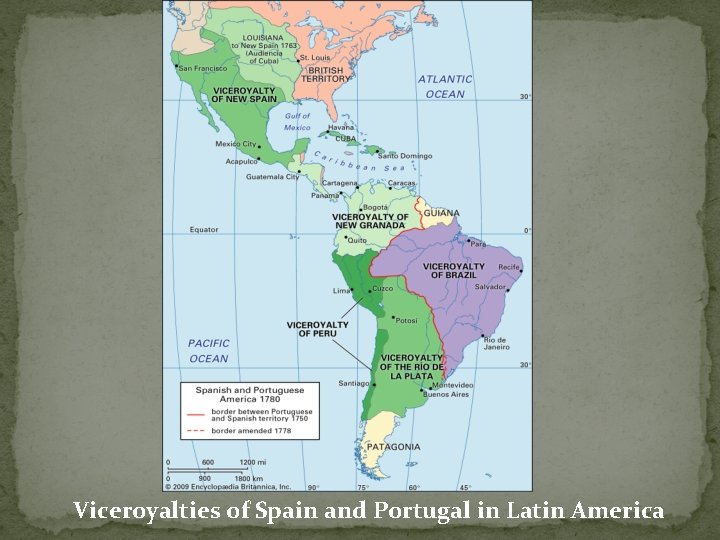

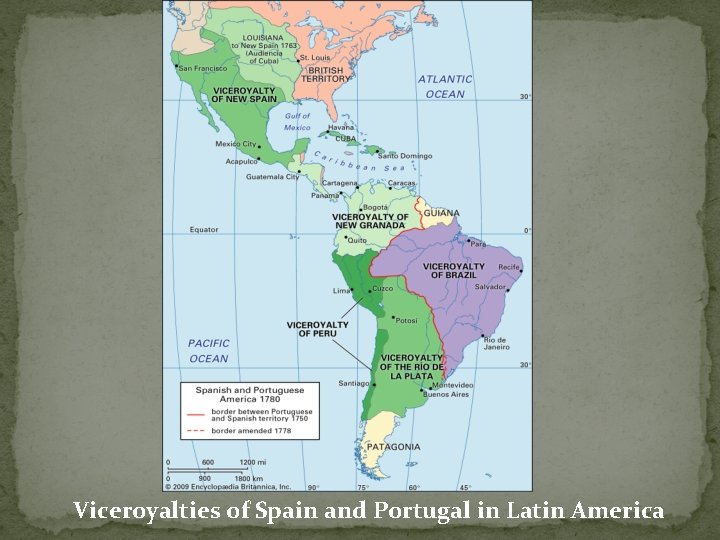

Viceroyalties of Spain and Portugal in Latin America

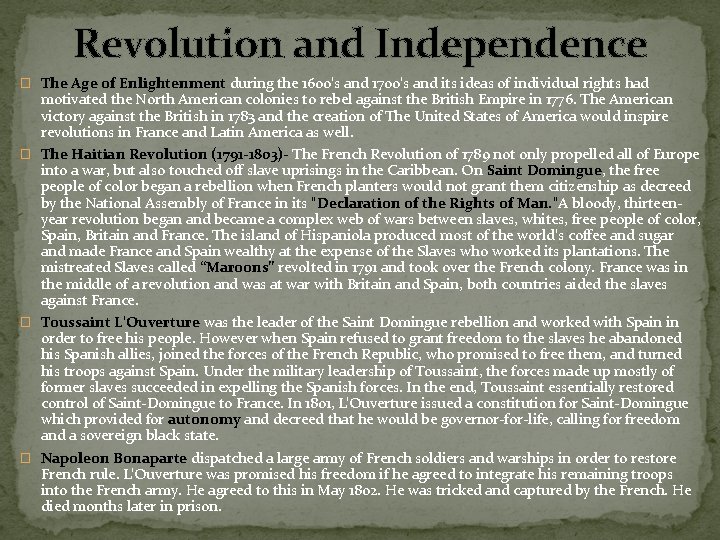

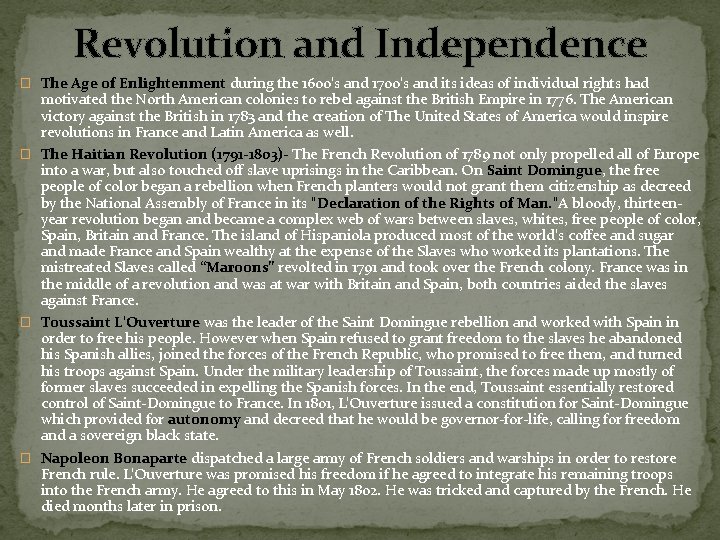

Revolution and Independence � The Age of Enlightenment during the 1600’s and 1700’s and its ideas of individual rights had motivated the North American colonies to rebel against the British Empire in 1776. The American victory against the British in 1783 and the creation of The United States of America would inspire revolutions in France and Latin America as well. � The Haitian Revolution (1791 -1803)- The French Revolution of 1789 not only propelled all of Europe into a war, but also touched off slave uprisings in the Caribbean. On Saint Domingue, the free people of color began a rebellion when French planters would not grant them citizenship as decreed by the National Assembly of France in its "Declaration of the Rights of Man. "A bloody, thirteenyear revolution began and became a complex web of wars between slaves, whites, free people of color, Spain, Britain and France. The island of Hispaniola produced most of the world’s coffee and sugar and made France and Spain wealthy at the expense of the Slaves who worked its plantations. The mistreated Slaves called “Maroons” revolted in 1791 and took over the French colony. France was in the middle of a revolution and was at war with Britain and Spain, both countries aided the slaves against France. � Toussaint L'Ouverture was the leader of the Saint Domingue rebellion and worked with Spain in order to free his people. However when Spain refused to grant freedom to the slaves he abandoned his Spanish allies, joined the forces of the French Republic, who promised to free them, and turned his troops against Spain. Under the military leadership of Toussaint, the forces made up mostly of former slaves succeeded in expelling the Spanish forces. In the end, Toussaint essentially restored control of Saint-Domingue to France. In 1801, L'Ouverture issued a constitution for Saint-Domingue which provided for autonomy and decreed that he would be governor-for-life, calling for freedom and a sovereign black state. � Napoleon Bonaparte dispatched a large army of French soldiers and warships in order to restore French rule. L'Ouverture was promised his freedom if he agreed to integrate his remaining troops into the French army. He agreed to this in May 1802. He was tricked and captured by the French. He died months later in prison.

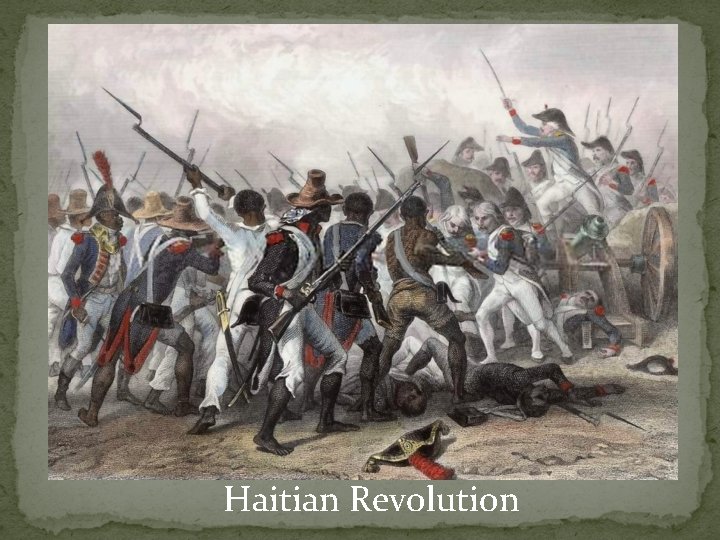

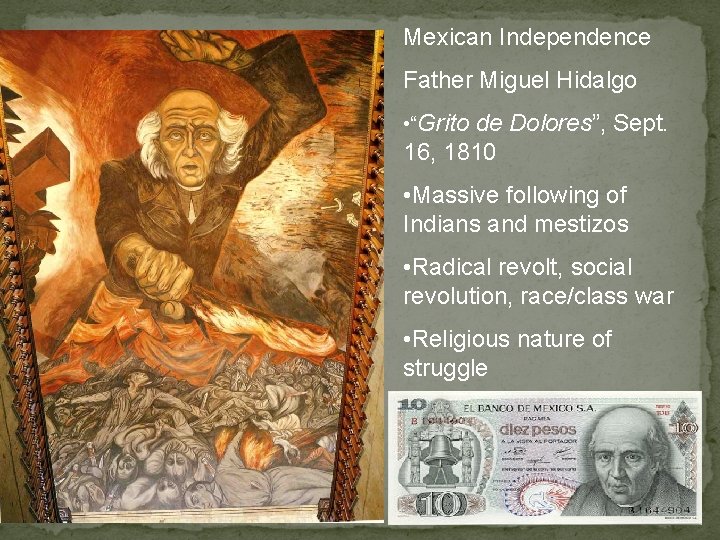

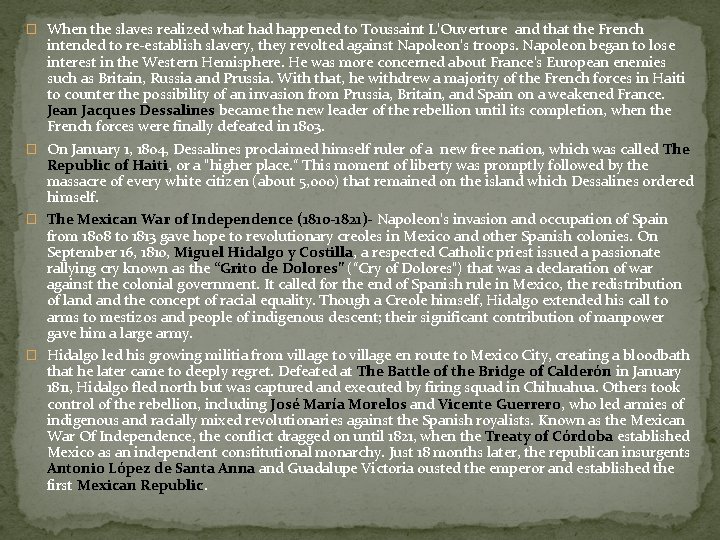

� When the slaves realized what had happened to Toussaint L'Ouverture and that the French intended to re-establish slavery, they revolted against Napoleon’s troops. Napoleon began to lose interest in the Western Hemisphere. He was more concerned about France's European enemies such as Britain, Russia and Prussia. With that, he withdrew a majority of the French forces in Haiti to counter the possibility of an invasion from Prussia, Britain, and Spain on a weakened France. Jean Jacques Dessalines became the new leader of the rebellion until its completion, when the French forces were finally defeated in 1803. � On January 1, 1804, Dessalines proclaimed himself ruler of a new free nation, which was called The Republic of Haiti, or a "higher place. “ This moment of liberty was promptly followed by the massacre of every white citizen (about 5, 000) that remained on the island which Dessalines ordered himself. � The Mexican War of Independence (1810 -1821)- Napoleon’s invasion and occupation of Spain from 1808 to 1813 gave hope to revolutionary creoles in Mexico and other Spanish colonies. On September 16, 1810, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, a respected Catholic priest issued a passionate rallying cry known as the “Grito de Dolores” (“Cry of Dolores”) that was a declaration of war against the colonial government. It called for the end of Spanish rule in Mexico, the redistribution of land the concept of racial equality. Though a Creole himself, Hidalgo extended his call to arms to mestizos and people of indigenous descent; their significant contribution of manpower gave him a large army. � Hidalgo led his growing militia from village to village en route to Mexico City, creating a bloodbath that he later came to deeply regret. Defeated at The Battle of the Bridge of Calderón in January 1811, Hidalgo fled north but was captured and executed by firing squad in Chihuahua. Others took control of the rebellion, including José María Morelos and Vicente Guerrero, who led armies of indigenous and racially mixed revolutionaries against the Spanish royalists. Known as the Mexican War Of Independence, the conflict dragged on until 1821, when the Treaty of Córdoba established Mexico as an independent constitutional monarchy. Just 18 months later, the republican insurgents Antonio López de Santa Anna and Guadalupe Victoria ousted the emperor and established the first Mexican Republic.

Haitian Revolution

Mexican Independence Father Miguel Hidalgo • “Grito de Dolores”, Sept. 16, 1810 • Massive following of Indians and mestizos • Radical revolt, social revolution, race/class war • Religious nature of struggle

Father Hidalgo Mexican War of Independence

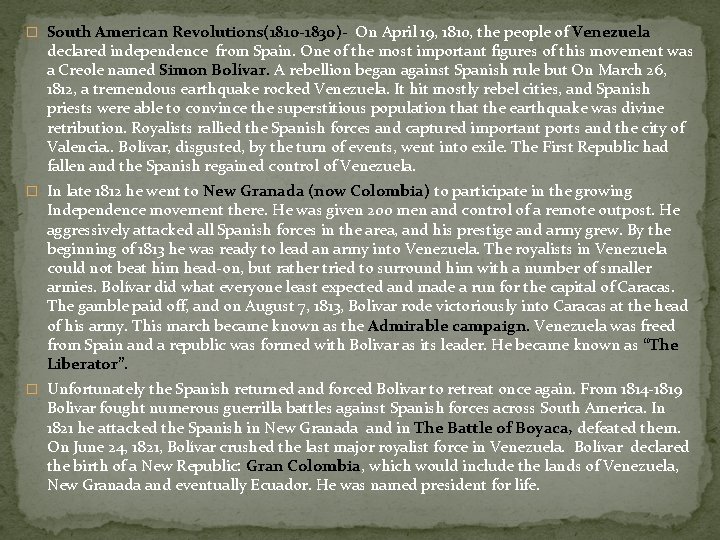

� South American Revolutions(1810 -1830)- On April 19, 1810, the people of Venezuela declared independence from Spain. One of the most important figures of this movement was a Creole named Simon Bolívar. A rebellion began against Spanish rule but On March 26, 1812, a tremendous earthquake rocked Venezuela. It hit mostly rebel cities, and Spanish priests were able to convince the superstitious population that the earthquake was divine retribution. Royalists rallied the Spanish forces and captured important ports and the city of Valencia. . Bolívar, disgusted, by the turn of events, went into exile. The First Republic had fallen and the Spanish regained control of Venezuela. � In late 1812 he went to New Granada (now Colombia) to participate in the growing Independence movement there. He was given 200 men and control of a remote outpost. He aggressively attacked all Spanish forces in the area, and his prestige and army grew. By the beginning of 1813 he was ready to lead an army into Venezuela. The royalists in Venezuela could not beat him head-on, but rather tried to surround him with a number of smaller armies. Bolívar did what everyone least expected and made a run for the capital of Caracas. The gamble paid off, and on August 7, 1813, Bolivar rode victoriously into Caracas at the head of his army. This march became known as the Admirable campaign. Venezuela was freed from Spain and a republic was formed with Bolivar as its leader. He became known as “The Liberator”. � Unfortunately the Spanish returned and forced Bolivar to retreat once again. From 1814 -1819 Bolivar fought numerous guerrilla battles against Spanish forces across South America. In 1821 he attacked the Spanish in New Granada and in The Battle of Boyaca, defeated them. On June 24, 1821, Bolívar crushed the last major royalist force in Venezuela. Bolívar declared the birth of a New Republic: Gran Colombia, which would include the lands of Venezuela, New Granada and eventually Ecuador. He was named president for life.

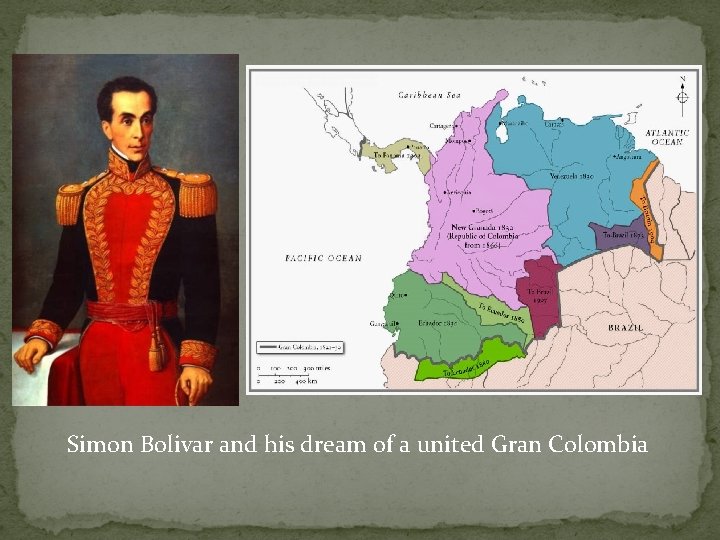

� Simon Bolivar sent his new army of Gran Colombia into Ecuador and in 1822 freed the land from the Spanish. Bolivar continued his revolutionary activities by teaming up with Jose de San Martin, the liberator of Argentina. It was decided that Bolívar would lead the charge into Peru, the last royalist stronghold on the continent. In 1824 Bolivar’s forces dealt the royalists another harsh blow at the Battle of Ayacucho, basically destroying the last royalist army in Peru. The next year, the Congress of Upper Peru created the nation of Bolivia, naming it after Bolivar and confirming him as President. � Bolívar had driven the Spanish out of northern and western South America and now ruled over the present-day nations of Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela and Panama. It was his dream to unite them all, creating one unified nation. It was not to be. Constant in -fighting between regional leaders led to civil war in Gran Colombia. This forced to Bolivar to declare himself Dictator to keep order. � Bolivar could not control the new Republic and his opponents even tried to assassinate him in 1828. As the Republic of Gran Colombia fell around him, his health deteriorated and he contracted tuberculosis. In April of 1830, ill and bitter, he resigned the Presidency and went into exile in Europe. Even as he left, his successors fought over the pieces of his Empire and his allies fought to get him reinstated. As Bolivar made his way to the coast, he still dreamed of unifying South America into one great nation. Simon Bolivar finally succumbed to tuberculosis on December 17, 1830. � Brazil became independent from Portugal with much less bloodshed than the Spanish- speaking nations of the New World; The Portuguese prince regent Dom João decided to hide in Brazil during the Napoleonic Wars. On April 22, 1821, he appointed his son Dom Pedro I regent and returned to Portugal. Against the Portuguese parliament’s wishes Dom Pedro proclaimed the independence of Brazil; he was crowned emperor in 1822.

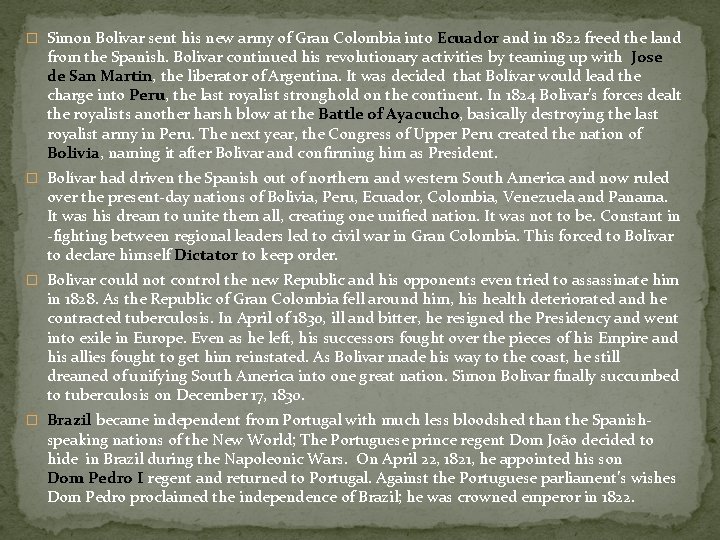

Simón Bolívar, the Liberator • Political philosopher, military leader, statesman • Leads northern South American independence – Bolivia, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Venezuela • Vision of a unified South America

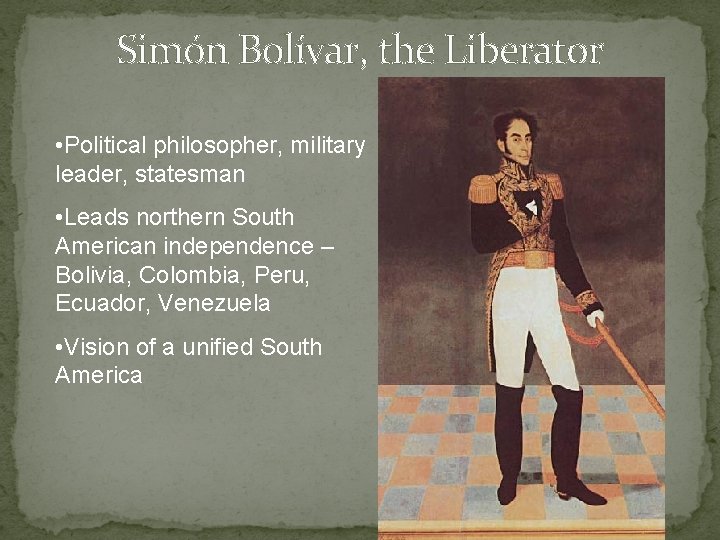

Simon Bolivar and his dream of a united Gran Colombia

The Liberator

Brazilian Independence 1822 Pedro I refuses to return to Portugal, declaration of Brazilian independence 1822 with the Grito do Ipiranga

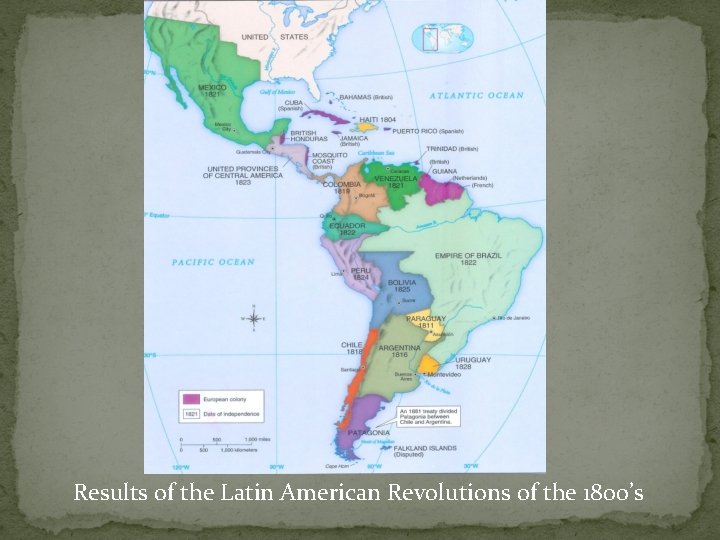

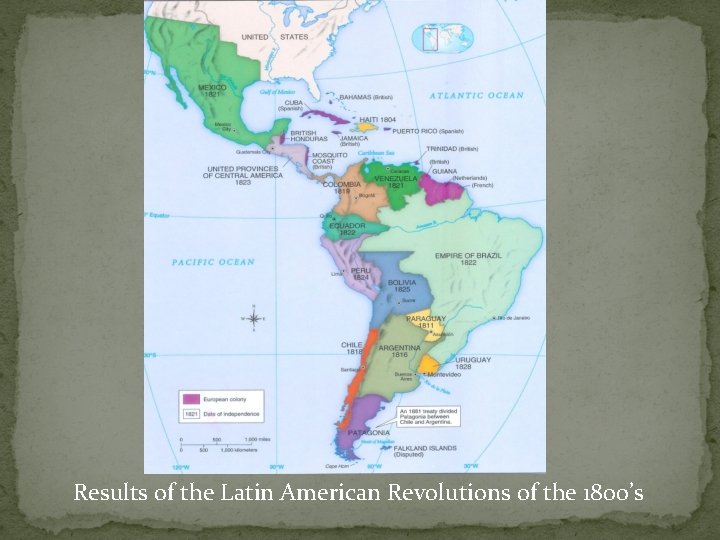

Results of the Latin American Revolutions of the 1800’s

Do Now � What were some of the results of the Spanish conquest of the Americas? What happened to many of the native tribes and their cultures? � How did the Spanish Encomienda system work? Why did it lead to native uprisings? � What was the role of the Catholic church and its missionaries in the Spanish colonies? Who was Bartolome de la Casas? What role did he play in the lives of native Americans? � Who was Juan de Onate? How did Spain’s conquest of New Mexico affect the Pueblo tribe? � Why did King Charles III create intendencias in the viceroyalties of the Spanish colonies in 1780? Were they effective? � What was Father Hidalgo’s role in the independence of Mexico from Spain? � Why were Toussaint L’ Ouverture and Simon Bolivar so important to the Latin American Independence movement? How did their revolts against France and Spain change Latin America? � How was the colonial and revolutionary era of Latin America different in Brazil? Why was it unique?