Cognitive Psychology Part I Where does Cognitive Psychology

- Slides: 25

Cognitive Psychology Part I: Where does Cognitive Psychology fit within Cognitive Science? 19 September, 2000 HKU 1

Just about everywhere. Almost all research in Cognitive Science is relevant to some Cognitive Psychologist. 19 September, 2000 HKU 2

Important Concepts • Three levels of organization of intelligent systems (Pylyshyn, 1999) – Physical/Biological – Syntactic/Symbolic – Semantic/Knowledge 19 September, 2000 HKU 3

• Three levels of understanding information processing (Marr, 1982) – Hardware Implementation – Representational Algorithm – Computational Theory 19 September, 2000 HKU 4

Computational Theory (knowledge/semantics) • What is the goal of the computation? See a brown dog Pet the brown dog 19 September, 2000 HKU 5

Representation & Algorithm (Syntactic/Symbolic) • How to implement these goals? • How are the inputs and outputs represented? – What must be done to “see” a brown dog? – To “pet” the brown dog? • What is the algorithm for transforming one to the other? 19 September, 2000 HKU 6

Hardware Implementation (biological/physical) • What physical equipment is needed to implement these representations and algorithms? 19 September, 2000 • • Retina(s) Interneurons Motoneurons Muscles Arm/hand Proprioceptors Tactile sensory neurons • Etc. HKU 7

• The three levels (theory, representation & algorithm, and implementation) are useful organizing principles in all of Cognitive Science • Psychology is mostly concerned with the second level: Representation and Processing 19 September, 2000 HKU 8

What’s not Cognitive Psychology? • Purely “engineering” solutions (e. g. Deep Blue II) – Building jet airplanes doesn’t help us better understand birds 19 September, 2000 HKU 9

Reading Assignment Week 2 • Pylyshyn, Z. (1999). What’s in your mind? In Lepore, E. & Pylyshyn, Z. (Eds. ) What is Cognitive Science (pp. 1 -25). Oxford, Blackwell. 19 September, 2000 HKU 10

Warning Pylyshyn is very biased (but not necessarily wrong). • Opposed to behaviorism (1. 1– 1. 2, 4. 1). • Opposed to connectionism (In favor of symbolic representations) (4. 2). 19 September, 2000 HKU 11

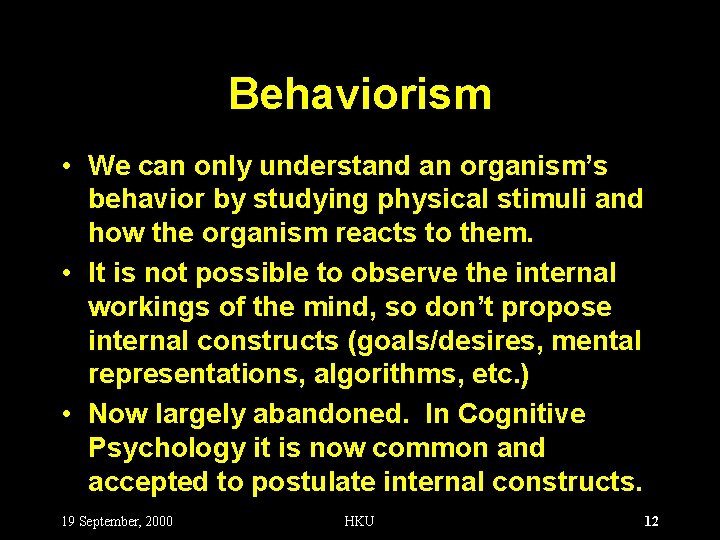

Behaviorism • We can only understand an organism’s behavior by studying physical stimuli and how the organism reacts to them. • It is not possible to observe the internal workings of the mind, so don’t propose internal constructs (goals/desires, mental representations, algorithms, etc. ) • Now largely abandoned. In Cognitive Psychology it is now common and accepted to postulate internal constructs. 19 September, 2000 HKU 12

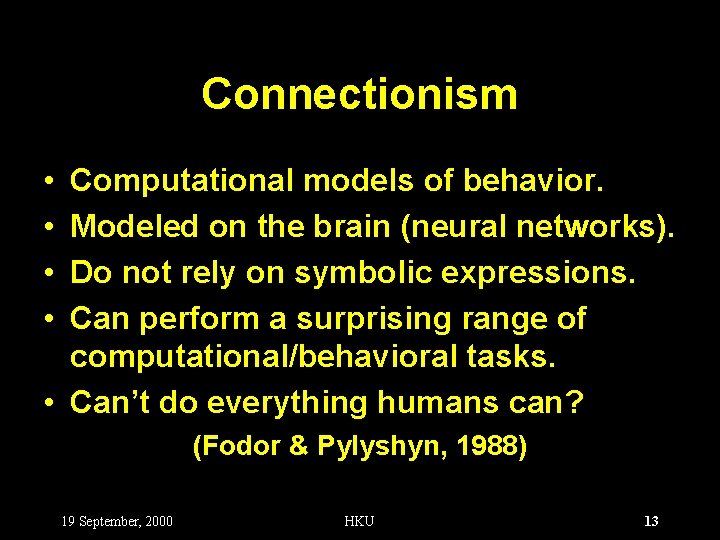

Connectionism • • Computational models of behavior. Modeled on the brain (neural networks). Do not rely on symbolic expressions. Can perform a surprising range of computational/behavioral tasks. • Can’t do everything humans can? (Fodor & Pylyshyn, 1988) 19 September, 2000 HKU 13

Part II What is Cognitive Psychology? 19 September, 2000 HKU 14

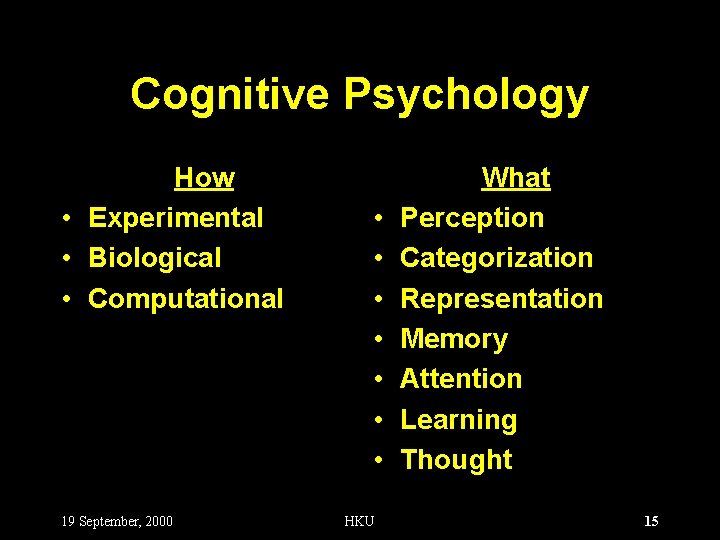

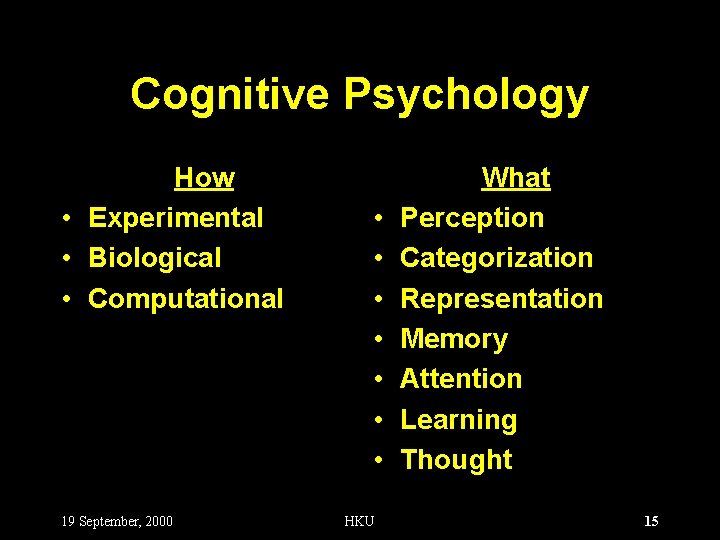

Cognitive Psychology How • Experimental • Biological • Computational 19 September, 2000 • • HKU What Perception Categorization Representation Memory Attention Learning Thought 15

Why do experiments? “Human beings were not created for the convenience of experimental psychologists. ” George Miller (in Barsalou, 1992) 19 September, 2000 HKU 16

Control the situation • Most phenomena could have many causes, how do we know which one is the (main) cause? • Test each possibility, one by one. • Need to eliminate chance of other causes taking effect (control) 19 September, 2000 HKU 17

Some ways to control variables • Select your subjects carefully – Only right-handed, male, native English speakers • Create your stimuli carefully – Record specific syllables spoken by a trained talker • Choose a simple environment – Empty room, sound booth, etc. 19 September, 2000 HKU 18

Manipulate your subjects • Experiments crucially involve a comparison of (at least) two groups (who may still be the same people). • The difference between the groups is caused by manipulation of experimental variables. 19 September, 2000 HKU 19

Some Experimental Manipulations • Between group comparisons: – 2 year-old children vs. 6 yr olds – English speakers vs. Cantonese speakers – University students vs. early school leavers • Within group comparisons: – Untrained listeners vs. trained listeners – Listening to Cantonese vs. listening to English – Dosed with a drug vs. with a placebo 19 September, 2000 HKU 20

For example • Question: Does knowing how to speak one tone language make it easier to hear the tones of a different tone language? (easier than it is without knowing a tone language) • Possible answers: – Yes, perception of tone is universal – if you’ve got it, you’ve got it. – No, perception of tone is language-specific. You must learn the sound system of each language separately. • How do we test this? 19 September, 2000 HKU 21

Lee, Vakoch, & Wurm (1996) • Three groups: Cantonese, Mandarin, and English speakers • Two sets of sounds: Cantonese and Mandarin (presented in pairs, grouped by language) • Asked subjects “same or different” for each pair 19 September, 2000 HKU 22

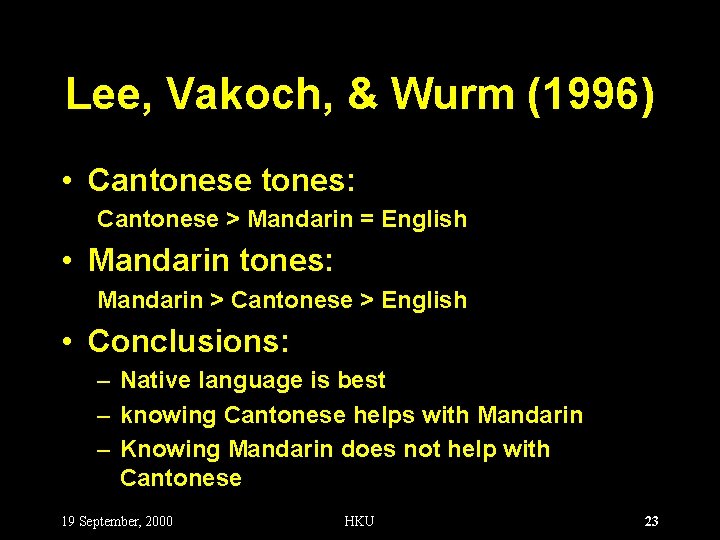

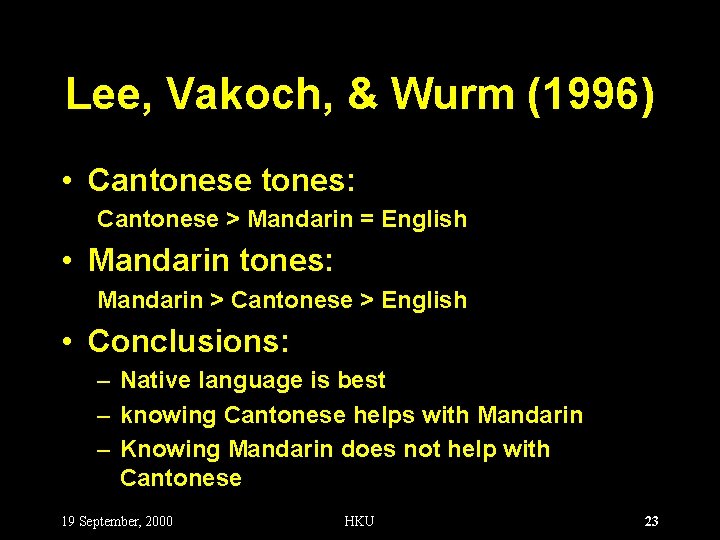

Lee, Vakoch, & Wurm (1996) • Cantonese tones: Cantonese > Mandarin = English • Mandarin tones: Mandarin > Cantonese > English • Conclusions: – Native language is best – knowing Cantonese helps with Mandarin – Knowing Mandarin does not help with Cantonese 19 September, 2000 HKU 23

Criticism of experiments • Ecologically implausible – “same-different” task is unlike real speech perception • Small answers to small problems – What do we really know that we didn’t know before? 19 September, 2000 HKU 24

Bibliography • • • Barsalou, L. W. Cognitive Psychology: An Overview for Cognitive Scientists. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates. Coren, S. & Ward, L. M. (1989). Sensation and Perception, Third Edition. Fort Worth, NJ, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Fodor, J. A. & Pylyshyn, Z. W. (1988). Connectionism and cognitive architecture: a critical analysis. Cognition, 28, 3 -71. Goldstone, R. L. , & Barsalou, L. W. (1998). Reuniting perception and conception. Cognition, 65, 231 -262. Lee, Y. -S. , Vakoch, D. A. , & Wurm, L. H. (1996). Tone perception in Cantonese and Mandarin: A crosslinguistic comparison. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 25, 527 -542. Marr, D. (1982). Vision. New York, W. H. Freeman & Company. Medin, D. L. & Aguilar, C. (1999). Categorization. In Wilson, R. A. & Keil, F. C. (Eds. ) The MIT Encyclopedia of the Cognitive Sciences (pp. 104 -106). Robert A. Wilson and Frank C. Keil. Cambridge, MA, MIT Press. Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review, 63, 81 -97. Pylyshyn, Z. W. (1999). What’s in your mind? In Lepore, E. & Pylyshyn, Z. W. (Eds. ) What is Cognitive Science (pp. 1 -25). Oxford, Blackwell. Shepard, R. N. , & Metzler, J. Mental rotation of three-dimensional objects. Science, 171, 701 -703. Stroop, J. (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 18, 624 -643. Wu, L. , (1995). Perceptual Representation in Conceptual Combination. Doctoral dissertation, University of Chicago 19 September, 2000 HKU 25