Cognitive Level of Analysis Session 2 Practical Lab

Cognitive Level of Analysis Session 2: Practical Lab Report Loftus & Palmer

What learning outcome will we be addressing? � The lab experiment we will be conducting is a simplified replication of a study that we will be exploring to address the following learning outcomes: With reference to relevant research studies, to what extent is one cognitive process reliable? Evaluate schema theory with reference to research studies. � We will primarily focus on conducting our study then link it back to the learning outcome in more detail later in the course

Which cognitive process? � � The cognitive process we will be focusing on is memory We will look at this in much greater detail later on but for now we are going to focus on Loftus and Palmer’s (1974) study on the accuracy of eye witness testimony � This will be one of the key studies you need to revise for your exam

Reliable or not? ? � � Research has demonstrated that memory might not be as reliable as we think. Memories may be influenced by other factors than what was recorded in the first place, due to the suggested reconstructive nature of memory. � Reconstructive memory: memory refers to theory that remembering the past reflects our attempts to reconstruct the events experienced previously. These efforts are based partly on traces of past events, but also on our general knowledge, our expectations, and our assumptions about what must have happened.

Eye witness testimony legal system uses eyewitness testimony (EWT) which relies on the accuracy of human memory to decide whether a person is guilty or not. � The � Normally, juries in courts of law take EWT very seriously, but recently, the use of DNA technology has demonstrated what some psychologists have claimed for years, eyewitnesses can be wrong.

Watch the video… http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=u-SBTRLo. Puo https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=I 4 V 6 ao. Yu. Dcg

Why is this area of study important? � Devlin Committee (1976) ◦ Those prosecuted after being picked in ID parade � 82% convicted ◦ Out of 374 cases where eyewitness was the only evidence � 74% conviction � Scheck et al. (2000) analyzed 62 cases where DNA evidence exonerated persons convicted of felonies, they found that: ◦ Mistaken identifications were involved in 52 of the 62 cases (84%). ◦ Seventy-seven witnesses in these 52 cases had erroneously identified the defendants as the perpetrators of the crimes. ◦ At trial, these witnesses undoubtedly appeared very confident in their identifications.

Loftus (1974) reliance on eyewitness testimony � Loftus (1974) ◦ Asked students to judge guilt or innocence of a man �Man had robbed a grocery store �Murdered the shop keepers daughter ◦ 9 out of 50 judged him guilty on the evidence alone ◦ 36 out of 50 judged him guilty with an eyewitness ◦ What do you think happened when students were told the eyewitness was not wearing his glasses and therefore could not see?

Loftus (1974) reliance on eyewitness testimony � Loftus (1974) ◦ Asked students to judge guilt or innocence of a man �Man had robbed a grocery store �Murdered the shop keepers daughter ◦ 9 out of 50 judged him guilty on the evidence alone ◦ 36 out of 50 judged him guilty with an eyewitness ◦ What do you think happened when students were told the eyewitness was not wearing his glasses and therefore could not see? 34 out of 50 still find him guilty This suggests people rely heavily on EWT

Watch the video https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=Rg 5 b. BJQOL 74

Loftus and Palmer research on the reliability of eyewitness testimony � � � One of the leading researchers into eyewitness testimony (EWT) is Elizabeth Loftus supports the idea that memory as reconstructive. Loftus claims that the nature of questions can influence witnesses memory. She calls this the “MISINFORMATION EFFECT” She suggests that Leading Questions – ‘a question phrased in a manner that tends to suggest the desired answer’ can influence recall This is misleading post (after) event information may lead to our schemas influencing the accuracy of recall

What is a schema? ? � Memory is influenced by the schemas we use to interpret the world � Schema – expectations based on previous experiences, moods, existing knowledge, contexts, attitudes and stereotypes � They reduce the amount of information to process � Schemas can distort reality and memories

Types of schemas § § Role Schemas: expectations about people in particular roles and social categories (e. g. , the role of a social psychologist, student, doctor) Self-Schemas: Self-Schemas expectations about the self that organize and guide the processing of self-relevant information Person Schemas: Schemas expectations based on personality traits. What we associate with a certain type of person (e. g. , introvert, warm person) Event Schemas: Schemas expectations about sequences of events in social situations. What we associate with certain situations (e. g. , restaurant schemas)

Leading Questions What is a leading question? � � � � Have you seen the book? (leading Q) Have you seen a book? (not leading Q) Memory is NOT like a camera - we reconstruct our memories Questions that make it more likely that a participant’s schema will influence them to give a desired answer E. g. ‘Did you see the knife’ (suggests there was a knife) Can lead to false memories Non-existent items can be added/events can be replaced with false events Loftus and Palmer (1974) conducted two experiments to investigate the effects of leading questions on memory

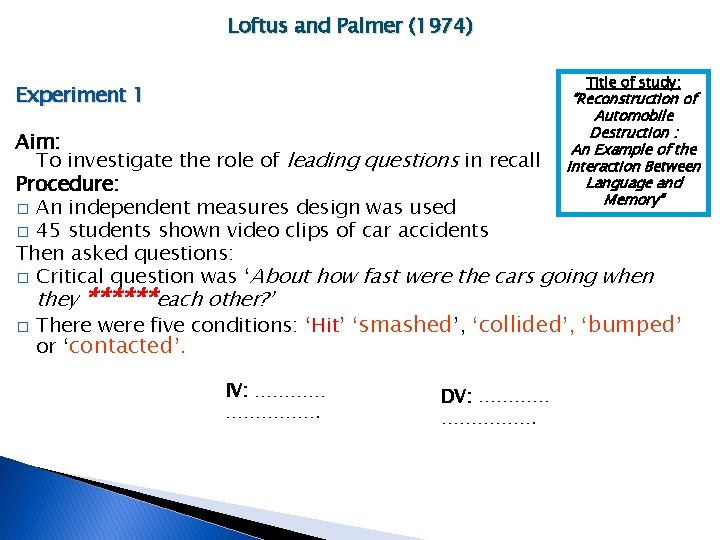

Loftus and Palmer (1974) Title of study: Experiment 1 “Reconstruction of Automobile Destruction : An Example of the Interaction Between Language and Memory” Aim: To investigate the role of leading questions in recall Procedure: � An independent measures design was used � 45 students shown video clips of car accidents Then asked questions: � Critical question was ‘About how fast were the cars going when they ******each other? ’ � There were five conditions: ‘Hit’ ‘smashed’, ‘collided’, ‘bumped’ or ‘contacted’. IV: ……………. DV: …………….

Loftus and Palmer (1974) Findings: of Experiment 1 Verb Mean estimate (mph) Smashed 40. 8 Collided 39. 3 Bumped 38. 1 Hit 34. 0 Contacted 31. 8 Conclusions: The use of different verbs activates different schemas in memory, so that the participant hearing the word ‘smashed’; may actually imagine the accident as more severe than the participant hearing the word ‘contacted’. What are the implications of these findings?

Loftus and Palmer (1974) A second experiment was carried out there were two possible explanations for results in first study ◦ Memory has been changed ◦ Word acts as a cue to the speed that is expected (demand characteristics)

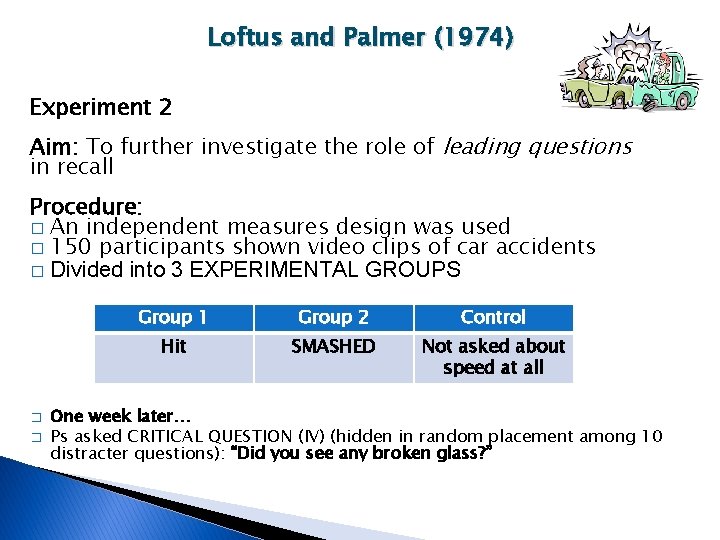

Loftus and Palmer (1974) Experiment 2 Aim: To further investigate the role of leading questions in recall Procedure: � An independent measures design was used � 150 participants shown video clips of car accidents � Divided into 3 EXPERIMENTAL GROUPS � � Group 1 Group 2 Control Hit SMASHED Not asked about speed at all One week later… Ps asked CRITICAL QUESTION (IV) (hidden in random placement among 10 distracter questions): “Did you see any broken glass? ”

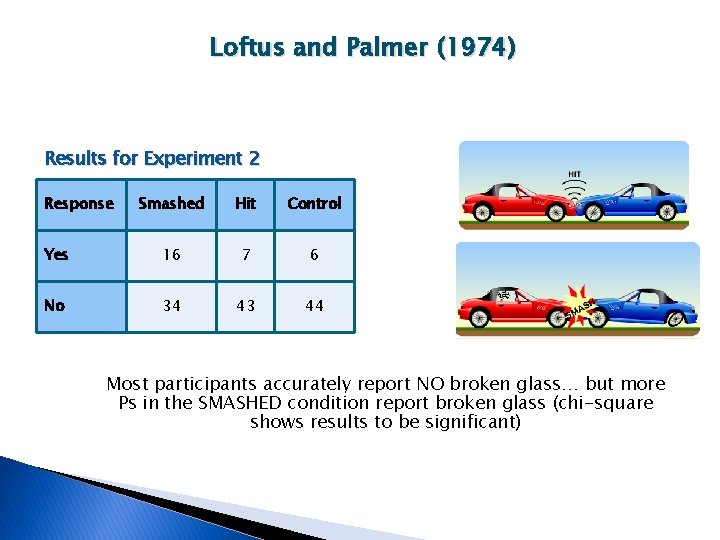

Loftus and Palmer (1974) Results for Experiment 2 Response Smashed Hit Control Yes 16 7 6 No 34 43 44 Most participants accurately report NO broken glass… but more Ps in the SMASHED condition report broken glass (chi-square shows results to be significant)

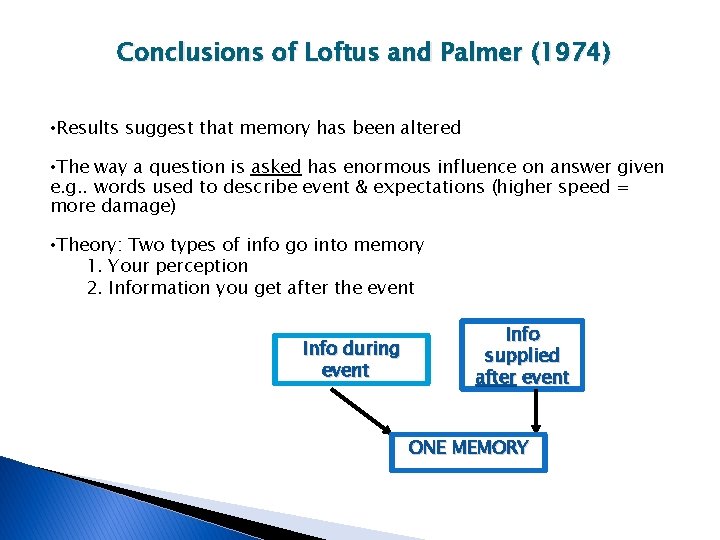

Conclusions of Loftus and Palmer (1974) • Results suggest that memory has been altered • The way a question is asked has enormous influence on answer given e. g. . words used to describe event & expectations (higher speed = more damage) • Theory: Two types of info go into memory 1. Your perception 2. Information you get after the event Info during event t Info supplied after event ONE MEMORY

Loftus and Palmer: findings & conclusions � � � Different words had an effect on the estimation of speed as well as the perception of the consequences of the accident. Loftus and Palmer (1974) explained that ‘smashed’ provides participants with verbal information that activates schemas for a severe accident. The higher rates of participants seeing broken glass is connected to this, the participant is more likely to think that there was broken glass involved when they were asked the leading question containing the word ‘smashed’ Loftus’s research also indicates that it is possible to create a false memory using misleading post-event information (i. e. – the questions asked after the event, causes memory to be easily distorted leading to inaccurate recall) This is also known as confabulation –confusion of true memories with false memories.

Think, pair, share! Evaluation of Loftus and Palmer (1974) Strengths Limitations

Evaluation of Loftus and Palmer (1974) Strengths � � Loftus and her colleagues have made an important contribution to our understanding of the fallibility of EWT. It seems clear from the research that memory for event can be fundamentally altered in light of misleading post event information. This had important implications for the way in which the police question witnesses, and also in the courtroom. Loftus used experimental methodology, so that cause & effect can be observed, making the study easily replicable. Loftus & Palmer (1974) also used a control condition in their second study: the 3 rd group were not asked about the speed but asked about whether they saw broken glass or not, for reliability of results. The use of experiment 2 enabled Loftus to make sure that the results of the experiment 1 were not merely due to demand characteristics.

Evaluation of Loftus and Palmer (1974) Limitations � � There are problems with the use of closed questions, which means people have to answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’ – research suggests people recall information better when asked questions in a logical order – such as the ‘Cognitive Interview’ developed by Geiselman et al (1985) to be used by the police to get detailed accounts from eyewitnesses. – when this technique is used EWT can be much more accurate. All the research participants were from the US, so the sample is culturally biased The research also raises the question of how well people are able to estimate speed, and this may have influenced the results Her research has also been criticized for its low E. V. & artificiality, in real life, events that might have to be recalled later in a court of law, often take place unexpectedly and in an atmosphere of tension. It is difficult to recreate such conditions in the laboratory for practical and ethical reasons, and it is quite possible that eyewitnesses remember real events differently from staged events

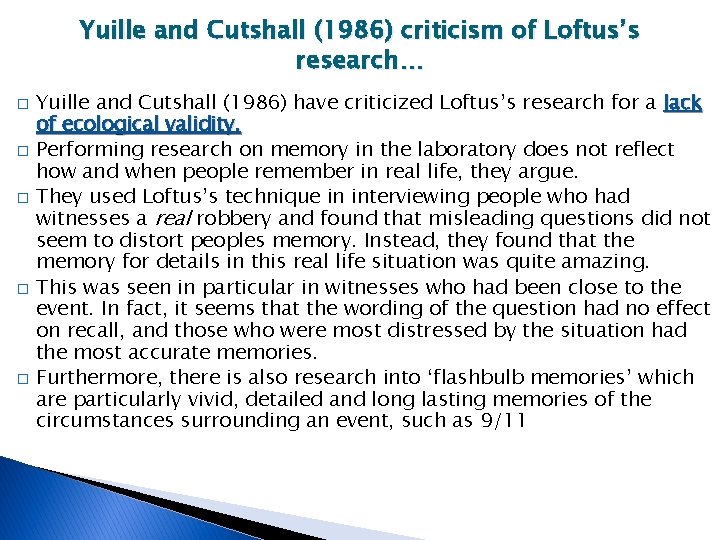

Yuille and Cutshall (1986) criticism of Loftus’s research… � � � Yuille and Cutshall (1986) have criticized Loftus’s research for a lack of ecological validity. Performing research on memory in the laboratory does not reflect how and when people remember in real life, they argue. They used Loftus’s technique in interviewing people who had witnesses a real robbery and found that misleading questions did not seem to distort peoples memory. Instead, they found that the memory for details in this real life situation was quite amazing. This was seen in particular in witnesses who had been close to the event. In fact, it seems that the wording of the question had no effect on recall, and those who were most distressed by the situation had the most accurate memories. Furthermore, there is also research into ‘flashbulb memories’ which are particularly vivid, detailed and long lasting memories of the circumstances surrounding an event, such as 9/11

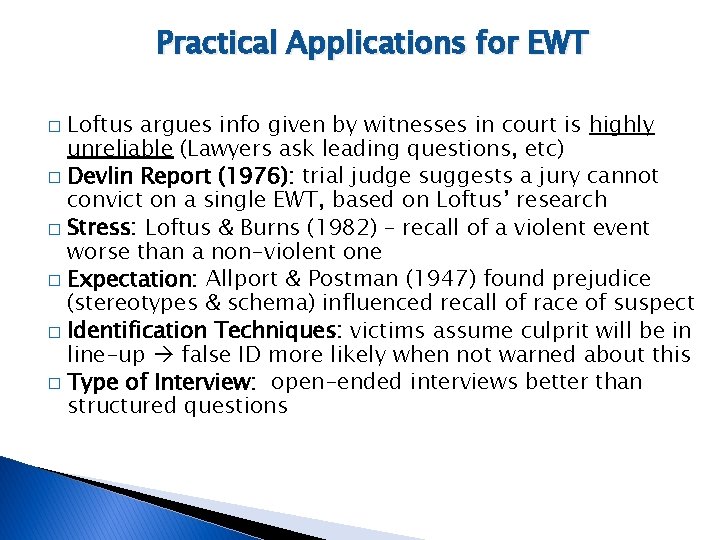

Practical Applications for EWT Loftus argues info given by witnesses in court is highly unreliable (Lawyers ask leading questions, etc) � Devlin Report (1976): trial judge suggests a jury cannot convict on a single EWT, based on Loftus’ research � Stress: Loftus & Burns (1982) – recall of a violent event worse than a non-violent one � Expectation: Allport & Postman (1947) found prejudice (stereotypes & schema) influenced recall of race of suspect � Identification Techniques: victims assume culprit will be in line-up false ID more likely when not warned about this � Type of Interview: open-ended interviews better than structured questions �

Our study � We will recreate a simplified version of the first experiment � We will be looking at the words ‘smashed’ and ‘contacted’ as these were the two that Loftus and Palmer found to have to biggest difference � We will also be including a control to further improve on the design � Although we won’t be using the broken glass question you could use this as a weakness or suggestions for further research � You could also develop on this for your IA next year

The bad news? You will need to produce a lab report on this experiment � This is worth a substantial amount of your semester grade � Draft feedback that was followed carefully last time led to a significant increase in grades. � The final deadline for the lab report is Friday Week 8. � Both a hard and soft copy must be submitted �

Let’s get started � What do you need to do in order to carry out this lab experiment?

Checklist for carrying out a lab experiment Ethics � Consent Form � Standardised Instructions � Raw Data Collection sheet � Debrief �

Some advice. . . You will need to follow the assessment criteria carefully � Use the lab report checklist I gave you last term to help you (a copy is available on the website in case “your dog ate it” � Re-read my Power. Point presentation on writing lab reports for extra tips I have added it to the end of this presentation � Look back at the feedback from your first lab report to avoid repeating unnecessary mistakes � Use the Loftus and Palmer articles to help you and do your own additional research � I would recommend that you begin working on the introduction to this already �

The Lab Report Title � Abstract � Introduction � Method ◦ Participants ◦ Materials ◦ Design ◦ Procedure � Results � Discussion � References � Appendices �

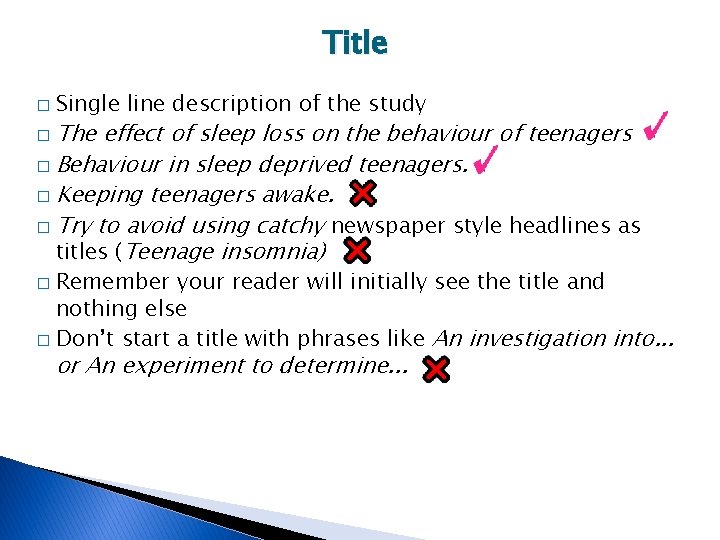

Title � Single line description of the study The effect of sleep loss on the behaviour of teenagers � Behaviour in sleep deprived teenagers. � Keeping teenagers awake. � Try to avoid using catchy newspaper style headlines as titles (Teenage insomnia) � Remember your reader will initially see the title and nothing else � Don’t start a title with phrases like An investigation into. . . � or An experiment to determine. . .

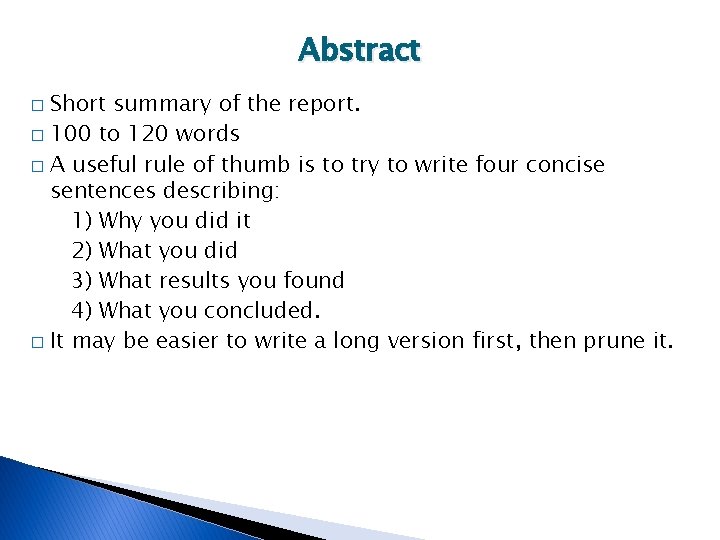

Abstract Short summary of the report. � 100 to 120 words � A useful rule of thumb is to try to write four concise sentences describing: 1) Why you did it 2) What you did 3) What results you found 4) What you concluded. � It may be easier to write a long version first, then prune it. �

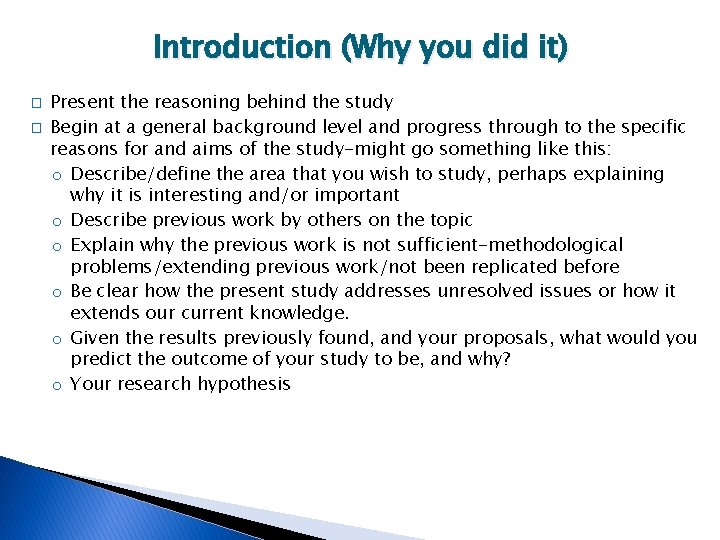

Introduction (Why you did it) � � Present the reasoning behind the study Begin at a general background level and progress through to the specific reasons for and aims of the study-might go something like this: o Describe/define the area that you wish to study, perhaps explaining why it is interesting and/or important o Describe previous work by others on the topic o Explain why the previous work is not sufficient-methodological problems/extending previous work/not been replicated before o Be clear how the present study addresses unresolved issues or how it extends our current knowledge. o Given the results previously found, and your proposals, what would you predict the outcome of your study to be, and why? o Your research hypothesis

Method (how you did it) 4 subsections � This section must contain enough information for the reader to be able to repeat the study, but should exclude any irrelevant details. � All text should be under one of the sub-headings �

Method: Design � A aspects of design should be described. � State what your independent variable(s) (or classification variable) and � dependent variable are. In research where there are two or more conditions in the study, define condition names, use same names throughout report. For example: This experiment used a between-subjects design. The independent variable was drug dosage (high or low dosage). The dependent variable was the number of problems successfully completed. � � For all experiments, you should also explain how you decided which experimental condition was performed by which participant– usually by random allocation. Order the conditions were presented (e. g. in repeated measures designs where a set of tasks are being given) again this can be done by randomising the order of trials or by counterbalancing blocks of trials.

Method: participants State how many participants were tested, who they were (i. e. , from what population they were drawn), how they were selected and/or recruited any other important characteristics (e. g. the age range, males/females, educational level). � Which characteristics are important will depend upon the task you are asking people to perform and the kinds of conclusions you wish to draw. � Depending on the research, these details may be trivial or extremely important (depending who you want to generalise results to). �

Method: materials Words, problems, questionnaires etc. are materials, � Should describe what these are and how you devised them (or who did devise them if you did not). � If there is an extensive list, it should be � provided in an appendix. �

Method: Procedures Describe exactly what took place during the testing session � Write impersonally, slanting the description towards the events that happened to the participant during the study. � Should include description of instructions given to participants including any particular emphasis (e. g. , instructing participants to be as fast and as accurate as possible, or to look closely at each item and try to remember it) � There should be enough information for them to repeat your study in every important respect. � Include info on how you were ethical � If YOU cannot work out from your description what happened to the participant, an independent reader has NO chance of understanding your research. �

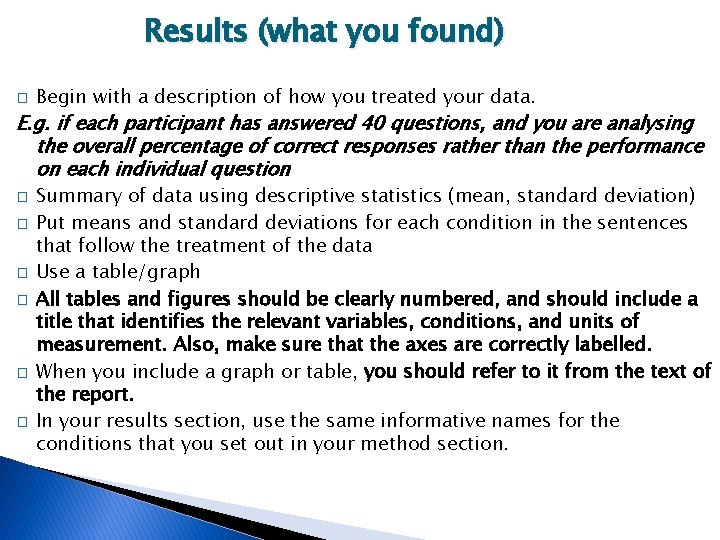

Results (what you found) � Begin with a description of how you treated your data. E. g. if each participant has answered 40 questions, and you are analysing the overall percentage of correct responses rather than the performance on each individual question � � � Summary of data using descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation) Put means and standard deviations for each condition in the sentences that follow the treatment of the data Use a table/graph All tables and figures should be clearly numbered, and should include a title that identifies the relevant variables, conditions, and units of measurement. Also, make sure that the axes are correctly labelled. When you include a graph or table, you should refer to it from the text of the report. In your results section, use the same informative names for the conditions that you set out in your method section.

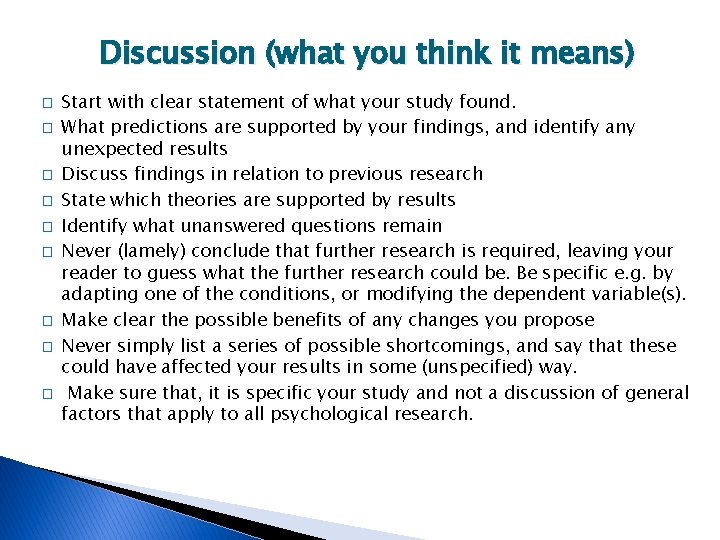

Discussion (what you think it means) � � � � � Start with clear statement of what your study found. What predictions are supported by your findings, and identify any unexpected results Discuss findings in relation to previous research State which theories are supported by results Identify what unanswered questions remain Never (lamely) conclude that further research is required, leaving your reader to guess what the further research could be. Be specific e. g. by adapting one of the conditions, or modifying the dependent variable(s). Make clear the possible benefits of any changes you propose Never simply list a series of possible shortcomings, and say that these could have affected your results in some (unspecified) way. Make sure that, it is specific your study and not a discussion of general factors that apply to all psychological research.

References � Follow guidelines on format in student diary � Reference all studies and theories you mention

Appendices � Raw data � Consent letter � Standardised Instructions No need to include in this assignment but this will be required for your IA

Tricks of the trade No personal pronouns. The participants were instructed to. . . � Write in past tense � Write the method first � Write the title and abstract last � Citation of Sources qe. g. Capp (2013) found. . . q(Barrett O’Connor, 2015) �

- Slides: 45