Code Quality Maintainability Reusability Debugging Testing SIF 8080

Code Quality, Maintainability, Reusability, Debugging, Testing SIF 8080, Sep. 27 th 2001 Customer-driven project Carl-Fredrik Sørensen mailto: carlfrs@idi. ntnu. no 1

Spider-web 2

Outline l Code Quality & Standards. l Debugging, logging etc. l Testing. 3

Key Principles; Coding l Understandability l High cohesion l Loose coupling l Code Formatting l Consistent Naming l Information hiding l Valuable Comments 4

Code Standards (1) l Why? – – l Gives less defects. Easier/cheaper maintenance. Several people may work on and understand the same code. Code to be read, not only written. Java coding standards: – The Elements of Java Style; Vermeulen et. al. SIGS Books. – http: //java. sun. com/docs/codeconv/html/Code. Conv. TOC. doc. html. 5

Code Standards (2) l General rules: – Simplicity – Build simple classes and methods. Keep it as simple as possible, but not simpler (Einstein). – Clarity – Ensure item has a clear purpose. Explain where, when, why, and how to use each. – Completeness – Create complete documentation; document all features and functionality. 6

Code Standards (3) l General rules (continued): – Consistency – Similar entities should look and behave the same; dissimilar entities should look and behave differently. Create and apply standards whenever possible. – Robustness – Provide predictable documented behaviour in response to errors and exceptions. Do not hide errors and do not force clients to detect errors. 7

Code Standards (4) l Do it right the first time ! l Your professionalism is expressed by applying code standards ! l Document any deviations! 8

Formatting l Is important for readability, not for the compiler. l Use a common standard for code formatting. l Do not alter the style of old code to fit new standards. 9

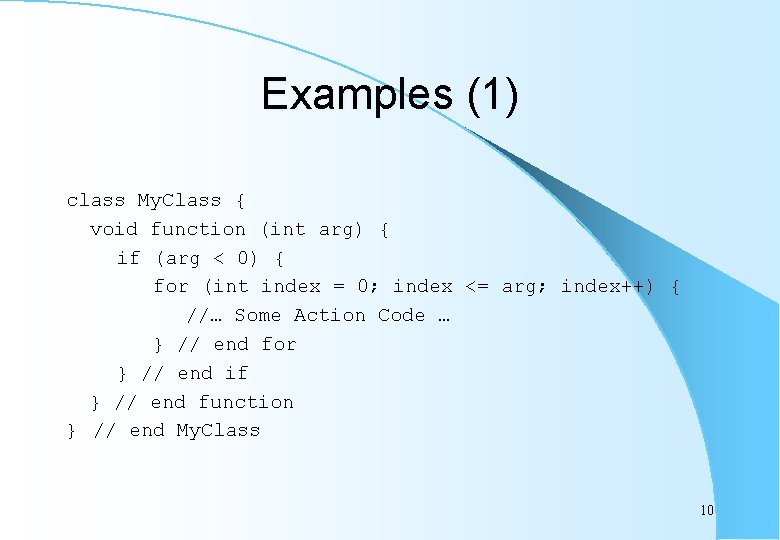

Examples (1) class My. Class { void function (int arg) { if (arg < 0) { for (int index = 0; index <= arg; index++) { //… Some Action Code … } // end for } // end if } // end function } // end My. Class 10

Examples (2) l Include white space: – Bad: double length=Math. sqrt(x*x+y*y); – Better: double length = Math. sqrt(x * x + y * y); – Use blank lines to separate. – Do not use hard tabs. 11

Naming l Clear, unambiguous, readable, meaningful. Describe the purpose of the item: – Bad: X 1, X 2, mth, get, tmp, temp, result. – Give a descriptive name to temporary variables. l But: scientific formulas may be better formulated with single characters/words representing symbols instead of descriptive names. 12

Naming Establish and use a common naming convention. l Problems creating a good name purpose of the operation is not clear. l – Bad: void get(…). , better: retrieve. Data. Samples. – Bad: Time day(Time p_day), better: get. Date or get. Trunc. Date. – Bad: void result(…), better: create. Results. – Bad: void gas/oil/water, better: calculate…Volume. Rate. 13

Java Naming Convention l Package: scope. mypackage l Classes: My. Class l Methods: my. Method l Constants: MY_CONSTANT l Attribute: my. Attribute l Variable: my. Variable 14

Parameters l l l Actual parameters should match the formal Input-modify-output order If several operations use similar parameters, put the similar parameters in a consistent order Use all parameters Document interface assumptions about parameters – access type, unit, ranges, non-valid values l Limit the number of parameters to about seven 15

Comments; Why, when, where, what Why: To be able to find out what a operation does after a half, one or two years. Automatic API documentation. l When; Document your code before or when you write it; Design before you implement. Put the design in the operation. l Where; Before the operation, at specific formulas, decision points etc. l What; Document the algorithm, avoid unnecessary comments. Refer to a specification if existing. l 16

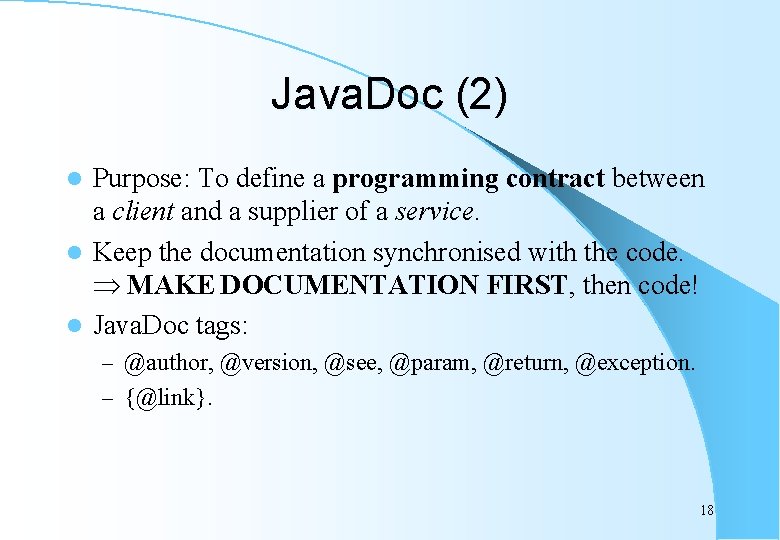

Java. Doc (1) Generates HTML-formatted class reference or API documentation. l Does only recognise documentation comments that appear immediately before l – class – Interface – constructor, – method – field declaration. 17

Java. Doc (2) Purpose: To define a programming contract between a client and a supplier of a service. l Keep the documentation synchronised with the code. MAKE DOCUMENTATION FIRST, then code! l Java. Doc tags: l – @author, @version, @see, @param, @return, @exception. – {@link}. 18

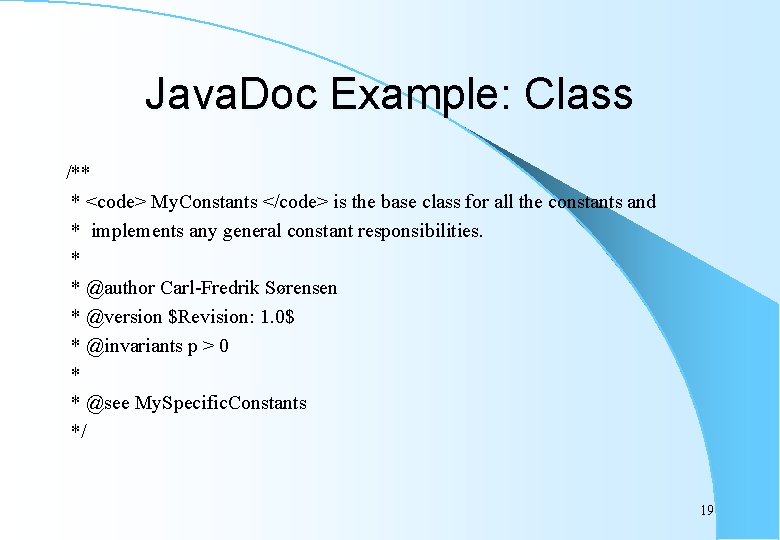

Java. Doc Example: Class /** * <code> My. Constants </code> is the base class for all the constants and * implements any general constant responsibilities. * * @author Carl-Fredrik Sørensen * @version $Revision: 1. 0$ * @invariants p > 0 * * @see My. Specific. Constants */ 19

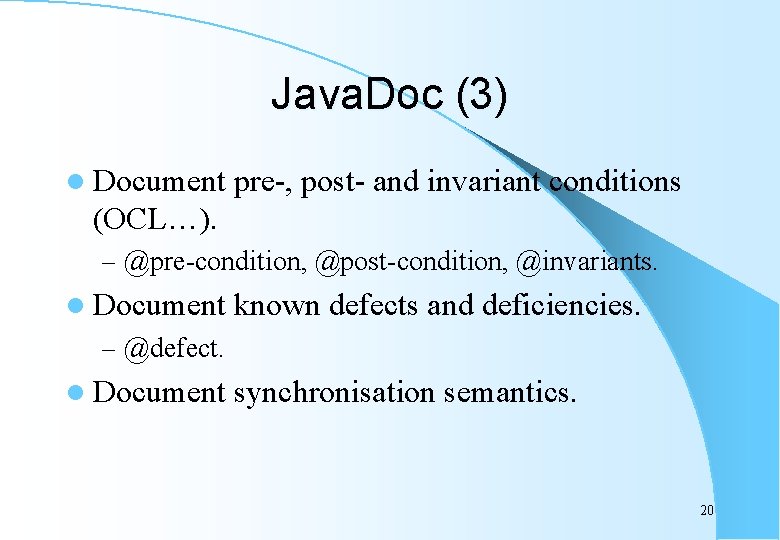

Java. Doc (3) l Document pre-, post- and invariant conditions (OCL…). – @pre-condition, @post-condition, @invariants. l Document known defects and deficiencies. – @defect. l Document synchronisation semantics. 20

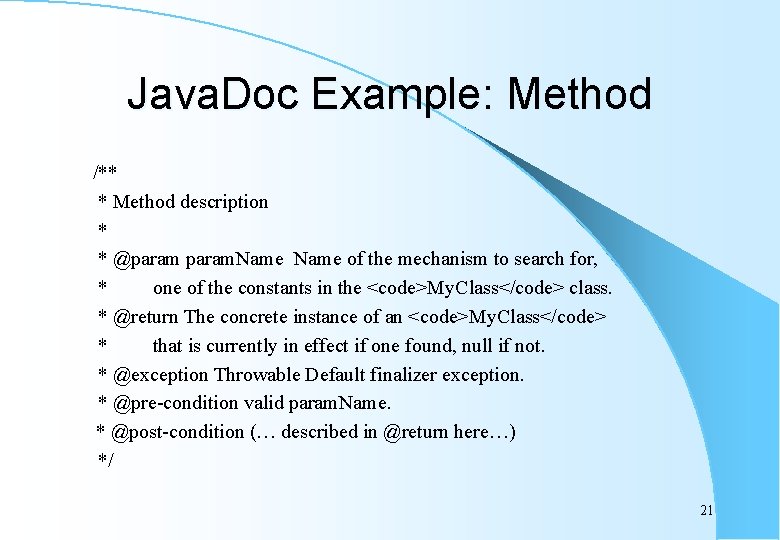

Java. Doc Example: Method /** * Method description * * @param. Name of the mechanism to search for, * one of the constants in the <code>My. Class</code> class. * @return The concrete instance of an <code>My. Class</code> * that is currently in effect if one found, null if not. * @exception Throwable Default finalizer exception. * @pre-condition valid param. Name. * @post-condition (… described in @return here…) */ 21

Architecture; How to Avoid Spider-web l Class/package organisation (loose coupling, high cohesion): – Split classes in (package/service) layers (user, data and business). Use package scoping (no. ntnu. idi…. . ). – Uni-directional dependencies. 22

Refactor to a New Architecture 23

Information Hiding Do not expose operations that should be local to a package. l Hide data access from the business services. l – Create separate packages for performing data services. – Define interfaces for data access, like e. g. EJB. l Scoping: – public: classes exposed by interfaces, operations in interfaces. – package: classes and operation not exposed through interface, but used by other classes in package. – private: local attributes and methods. 24

Information Hiding Hide the action part in control structures (functional cohesion) if complex, else delegate to a method. l What to hide: l – Areas that are likely to change; hardware dependencies, input/output, non-standard language features, difficult design and implementation areas, data-size constraints, business rules, potential changes. – Complex data. – Complex logic. 25

Binding l Bind constants as late as possible – Do not use magic Numbers, avoid hard-coded values total. Foo. Day = total. Foo. Hour * 24; if (me. equals(”thirsty”)) return ”water”; – Avoid global variables (constants OK) – Use separate classes/methods to hide hard-coded values l l l Achieves faster maintenance, and avoids copy-paste errors Makes code better suited for reuse Static methods and/or constants My. Constants. C 1_SPECIFIC_GRAVITY 26

Java Exceptions (1) l Unchecked run-time exception: serious unexpected errors that may indicate an error in the program’s logic Termination. l Checked exception: errors that may occur, however rarely, under normal program operation The caller must catch this exception. 27

Java Exceptions (2) l Only convert exceptions to add information. If the method does not know how to handle an exception it should not be handled. l Do not silently absorb a run-time or error exception makes code very hard to debug. l Use finally blocks to release resources. 28

Code Defensively (1) l Check input data for validity (Pre-conditions). – Range, comment assumptions about acceptable input ranges in the code. – Use a general approach for error handling when erroneous data. Use exception handling only to draw attention to unexpected cases (Do NOT perform any processing in exception code) (invariants). l Anticipate changes; Hide to minimise impact of change. l 29

Code Defensively (2) l Introduce debugging aids early (logging). l Check function return values (post-conditions). l Return friendly error messages; Write to a log file any system specific error messages (IO/SQL Exceptions, error codes etc. ). 30

Summary l Remember your code should be understandable. l Maintenance is often up to 70% of a total project cost. l Use quality control. 31

Outline l Code quality and Code Standards. l Debugging, logging etc. l Testing. 32

Debugging l Single thread/process. – IDE’s with debugger most often sufficient. l Multiple clients, threads, distributed applications. – Synchronisation issues to protect the state of objects. – IDE’s (most often) lack good support. – Pre-instrumentation of code is often necessary. l Non-visual services (e. g. Real-time data conversions). – May debug single runs in IDE’s. – Hard to debug in real settings: system runs continuously or discretely at fixed times 33

Application Logging: What and Why? An application log is a text history of notable events logged by your application. l The logs helps you to figure out what went wrong (and right) during the execution of your application. l With the advent of N-tier architectures, Servlets, JSPs, and EJBs, application logging is particularly important to report errors that cannot or should not be surfaced to the user interface. l 34

JLog – Java Logging Framework l Developed by Todd Lauinger. l A significant event happens in your Java code. That event could be any of several different types and conditions. Before you start using a logging framework: – categorize and document your events so that all users of the framework will log events consistently. 35

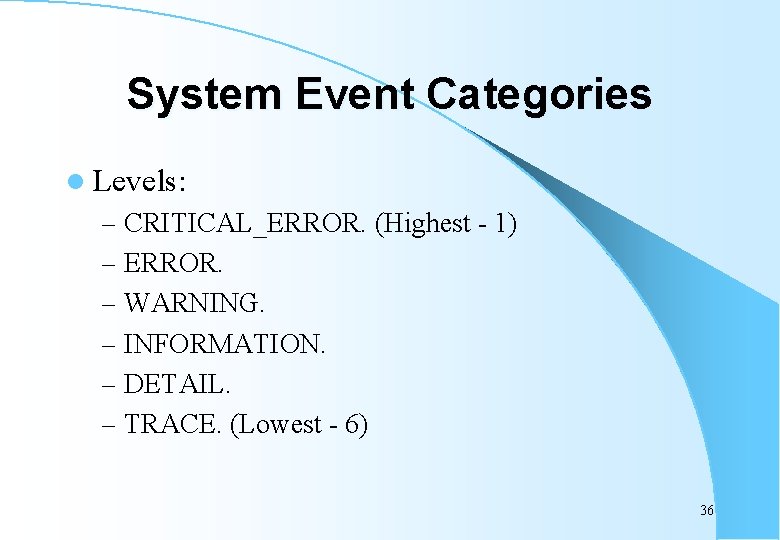

System Event Categories l Levels: – CRITICAL_ERROR. (Highest - 1) – ERROR. – WARNING. – INFORMATION. – DETAIL. – TRACE. (Lowest - 6) 36

Logging Granularity l Agreed and documented set of event categories determine the granularity to log those events. l Separate logs for e. g. – thread pool. – SQL processor. 37

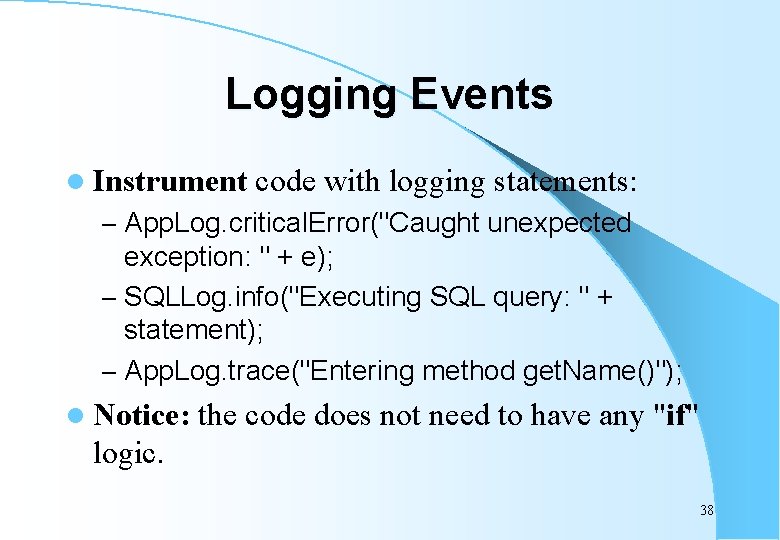

Logging Events l Instrument code with logging statements: – App. Log. critical. Error("Caught unexpected exception: " + e); – SQLLog. info("Executing SQL query: " + statement); – App. Log. trace("Entering method get. Name()"); l Notice: the code does not need to have any "if" logic. 38

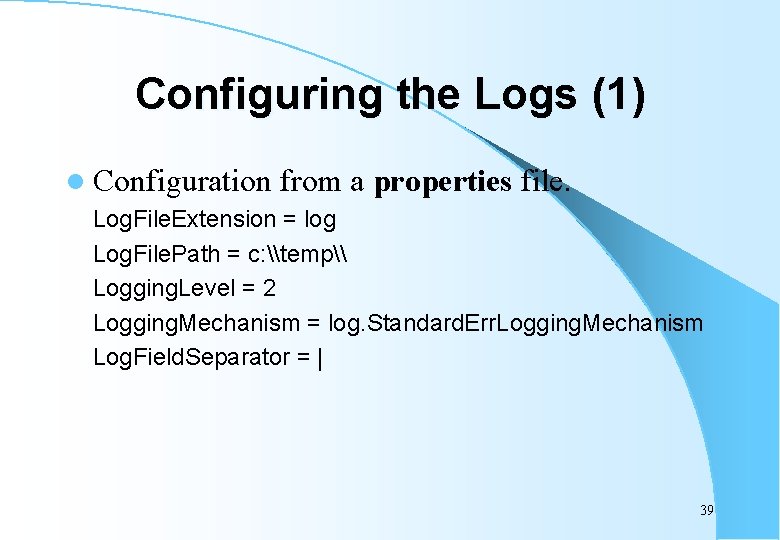

Configuring the Logs (1) l Configuration from a properties file. Log. File. Extension = log Log. File. Path = c: \temp\ Logging. Level = 2 Logging. Mechanism = log. Standard. Err. Logging. Mechanism Log. Field. Separator = | 39

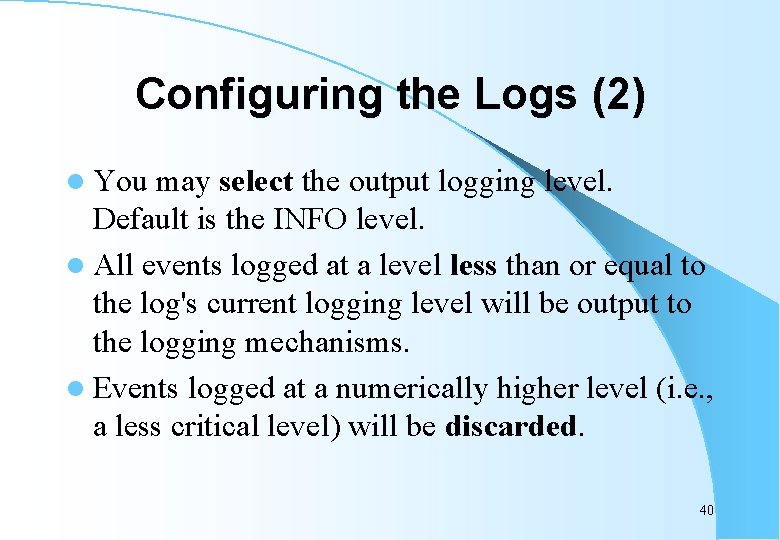

Configuring the Logs (2) l You may select the output logging level. Default is the INFO level. l All events logged at a level less than or equal to the log's current logging level will be output to the logging mechanisms. l Events logged at a numerically higher level (i. e. , a less critical level) will be discarded. 40

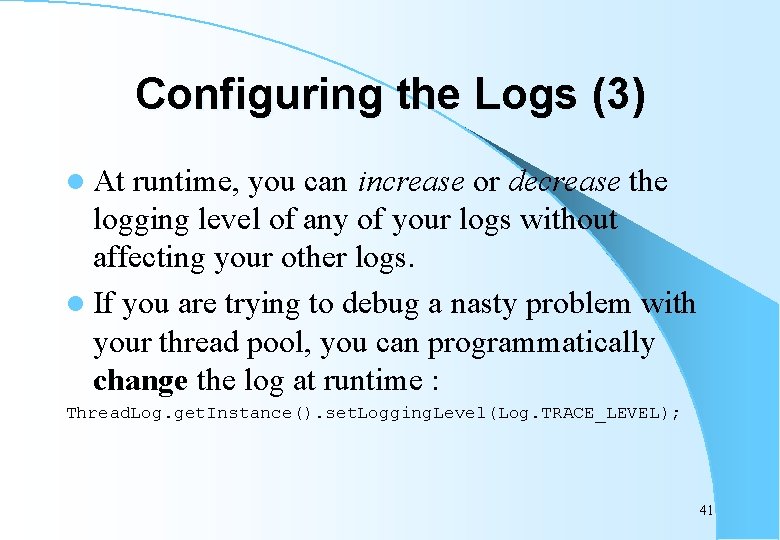

Configuring the Logs (3) l At runtime, you can increase or decrease the logging level of any of your logs without affecting your other logs. l If you are trying to debug a nasty problem with your thread pool, you can programmatically change the log at runtime : Thread. Log. get. Instance(). set. Logging. Level(Log. TRACE_LEVEL); 41

Configuring the Logs (4) l Other ways to dynamically reset the logging level at runtime: – In a debugger, you can change the value of the log's current. Logging. Level variable. – In an application server, you can examine and manipulate log properties with some JSPs. – Use RMI to manipulate the log properties of a remote JVM. – There are more options you can configure both programmatically and via a properties file. 42

Reading the Logs (1) l Sample entries from a shared log, a vertical bar ( | ), is used to delimit the various fields of log entries: Request. Log|L 4|09: 32: 23: 769|Execute. Thread-5|Executing request number 4 SQLLog|L 4|09: 32: 23: 835|Execute. Thread-5|select * from Customer where id = 35. Request. Log|L 4|09: 32: 23: 969|Execute. Thread-5|Request 4 took 200 milliseconds. 43

Reading the Logs (2) l Import the log into a spreadsheet: – ASCII text import with a vertical bar as a field delimiter. – Sort or filter the log using various spreadsheet capabilities. 44

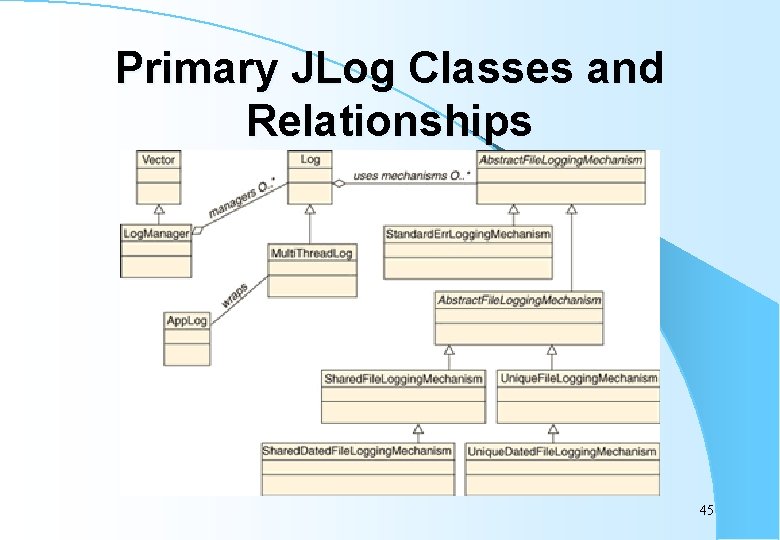

Primary JLog Classes and Relationships 45

Outline l Code quality and Code Standards. l Debugging, logging etc. l Testing. 46

Testing Not closely integrated with development prevents measurement of the progress of development - can't tell when something starts working or when something stops working. l JUnit to cheaply and incrementally build a test suite that helps to: l – measure your progress, – spot unintended side effects. – focus your development efforts. 47

JUnit l Automatic testing framework. – Acceptance tests. – Integration test. – Unit test. l Reports the number of defects graphically. l May create many tests for each method. 48

JUnit Example l Pay attention to the interplay of the code and the tests. – The style: to write a few lines of code, then a test that should run, – or even better: to write a test that won't run, then write the code that will make it run. l The program presented solves the problem of representing arithmetic with multiple currencies. 49

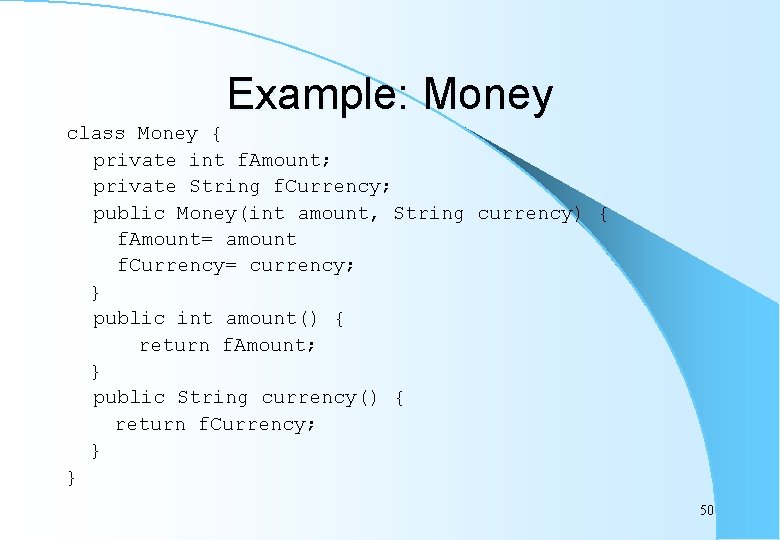

Example: Money class Money { private int f. Amount; private String f. Currency; public Money(int amount, String currency) { f. Amount= amount f. Currency= currency; } public int amount() { return f. Amount; } public String currency() { return f. Currency; } } 50

JUnit l JUnit defines how to structure your test cases and provides the tools to run them. l You implement a test in a subclass of Test. Case. 51

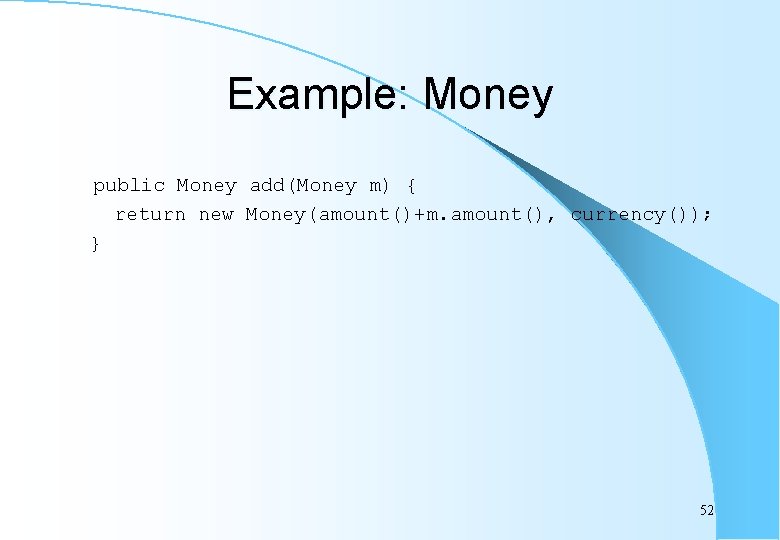

Example: Money public Money add(Money m) { return new Money(amount()+m. amount(), currency()); } 52

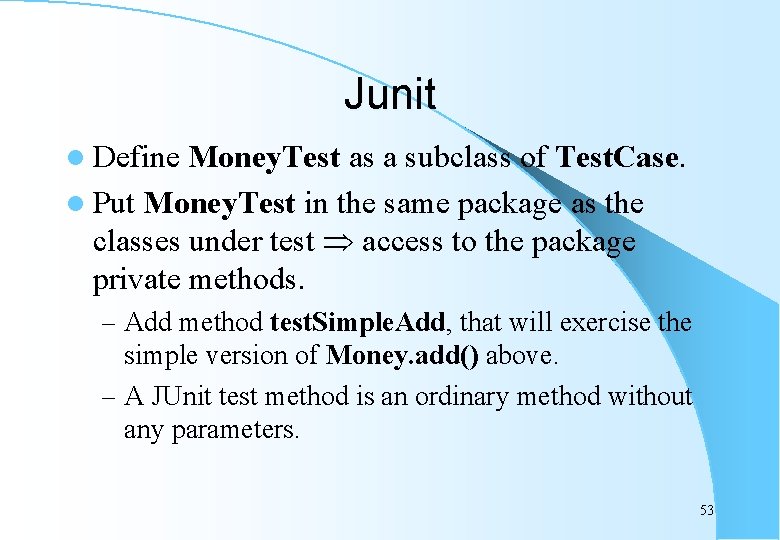

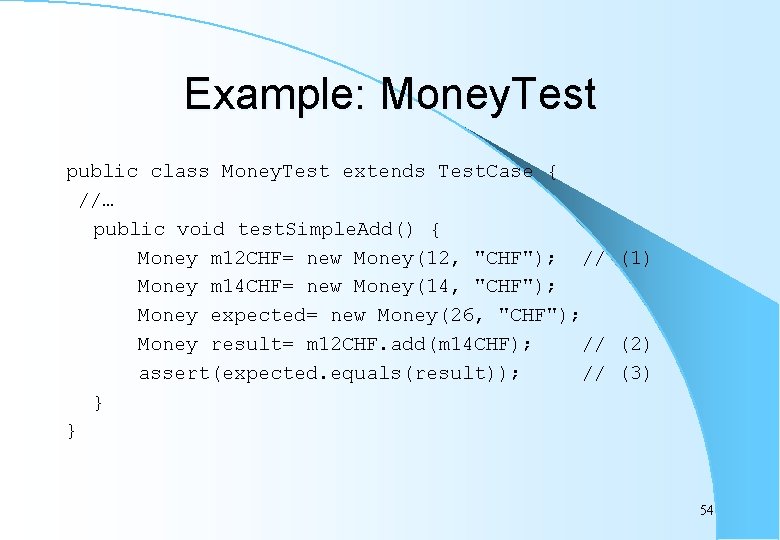

Junit l Define Money. Test as a subclass of Test. Case. l Put Money. Test in the same package as the classes under test access to the package private methods. – Add method test. Simple. Add, that will exercise the simple version of Money. add() above. – A JUnit test method is an ordinary method without any parameters. 53

Example: Money. Test public class Money. Test extends Test. Case { //… public void test. Simple. Add() { Money m 12 CHF= new Money(12, "CHF"); // (1) Money m 14 CHF= new Money(14, "CHF"); Money expected= new Money(26, "CHF"); Money result= m 12 CHF. add(m 14 CHF); // (2) assert(expected. equals(result)); // (3) } } 54

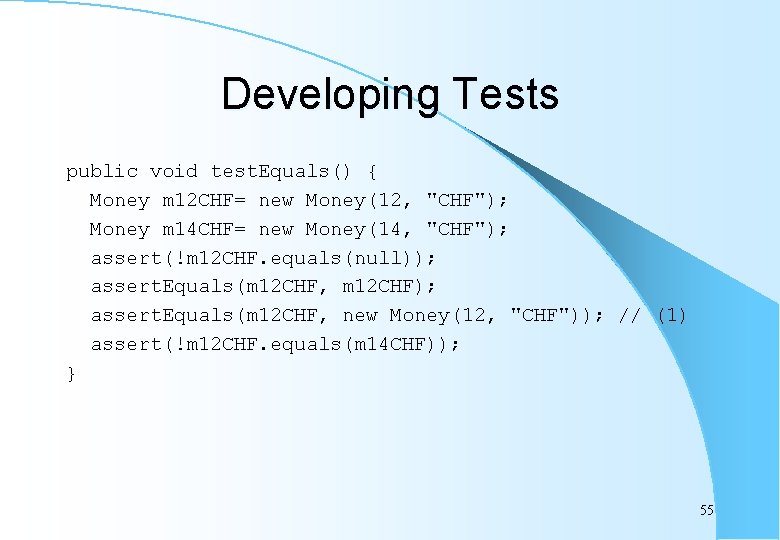

Developing Tests public void test. Equals() { Money m 12 CHF= new Money(12, "CHF"); Money m 14 CHF= new Money(14, "CHF"); assert(!m 12 CHF. equals(null)); assert. Equals(m 12 CHF, m 12 CHF); assert. Equals(m 12 CHF, new Money(12, "CHF")); // (1) assert(!m 12 CHF. equals(m 14 CHF)); } 55

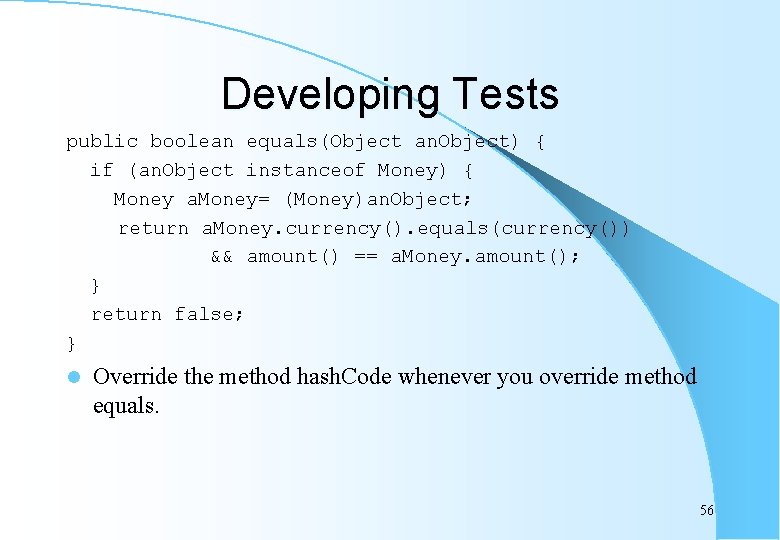

Developing Tests public boolean equals(Object an. Object) { if (an. Object instanceof Money) { Money a. Money= (Money)an. Object; return a. Money. currency(). equals(currency()) && amount() == a. Money. amount(); } return false; } l Override the method hash. Code whenever you override method equals. 56

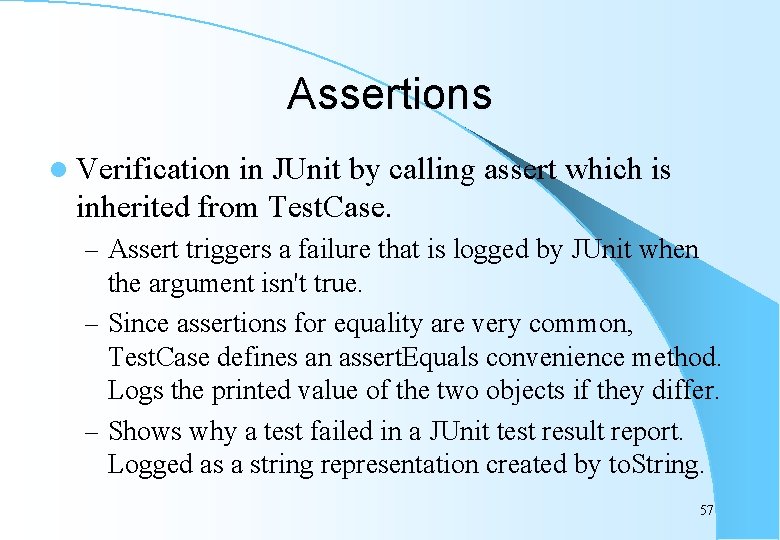

Assertions l Verification in JUnit by calling assert which is inherited from Test. Case. – Assert triggers a failure that is logged by JUnit when the argument isn't true. – Since assertions for equality are very common, Test. Case defines an assert. Equals convenience method. Logs the printed value of the two objects if they differ. – Shows why a test failed in a JUnit test result report. Logged as a string representation created by to. String. 57

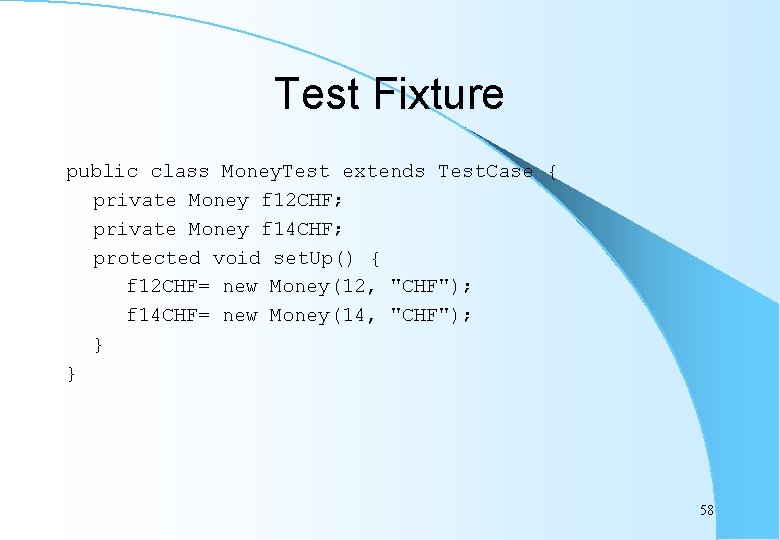

Test Fixture public class Money. Test extends Test. Case { private Money f 12 CHF; private Money f 14 CHF; protected void set. Up() { f 12 CHF= new Money(12, "CHF"); f 14 CHF= new Money(14, "CHF"); } } 58

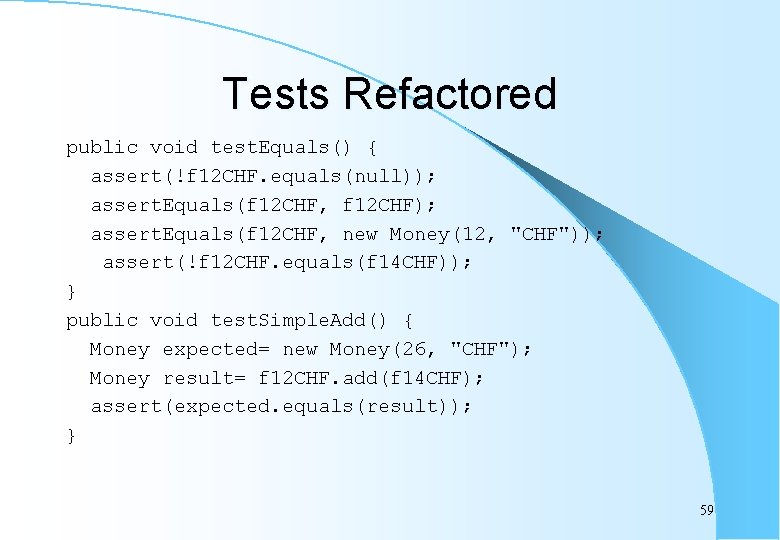

Tests Refactored public void test. Equals() { assert(!f 12 CHF. equals(null)); assert. Equals(f 12 CHF, f 12 CHF); assert. Equals(f 12 CHF, new Money(12, "CHF")); assert(!f 12 CHF. equals(f 14 CHF)); } public void test. Simple. Add() { Money expected= new Money(26, "CHF"); Money result= f 12 CHF. add(f 14 CHF); assert(expected. equals(result)); } 59

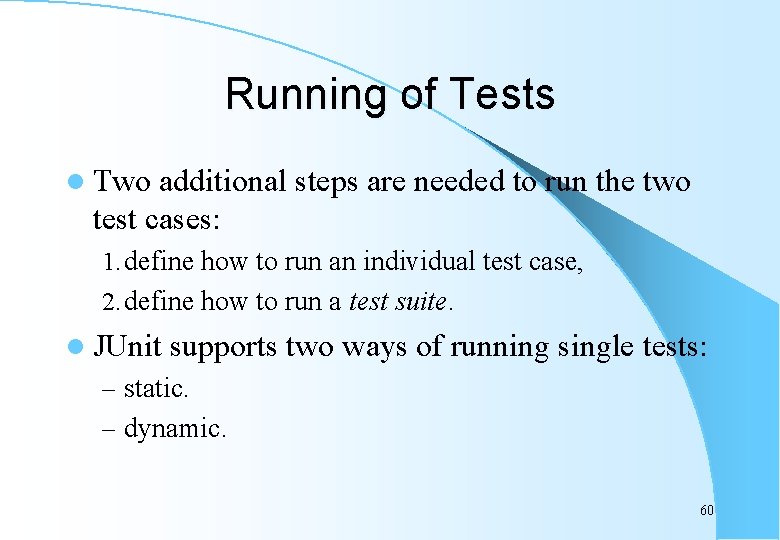

Running of Tests l Two additional steps are needed to run the two test cases: 1. define how to run an individual test case, 2. define how to run a test suite. l JUnit supports two ways of running single tests: – static. – dynamic. 60

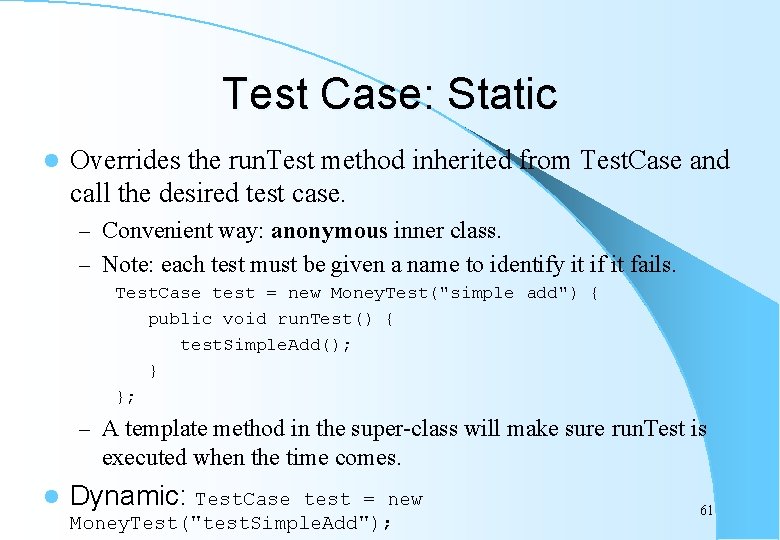

Test Case: Static l Overrides the run. Test method inherited from Test. Case and call the desired test case. – Convenient way: anonymous inner class. – Note: each test must be given a name to identify it if it fails. Test. Case test = new Money. Test("simple add") { public void run. Test() { test. Simple. Add(); } }; – A template method in the super-class will make sure run. Test is executed when the time comes. l Dynamic: Test. Case test = new Money. Test("test. Simple. Add"); 61

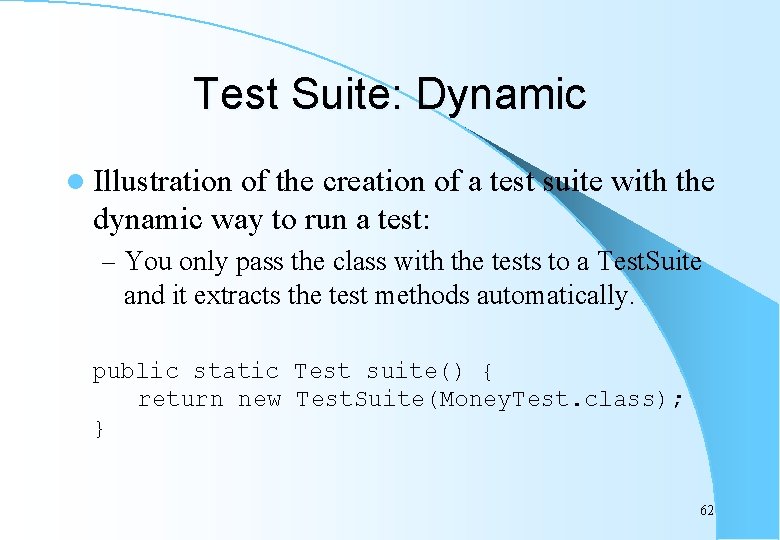

Test Suite: Dynamic l Illustration of the creation of a test suite with the dynamic way to run a test: – You only pass the class with the tests to a Test. Suite and it extracts the test methods automatically. public static Test suite() { return new Test. Suite(Money. Test. class); } 62

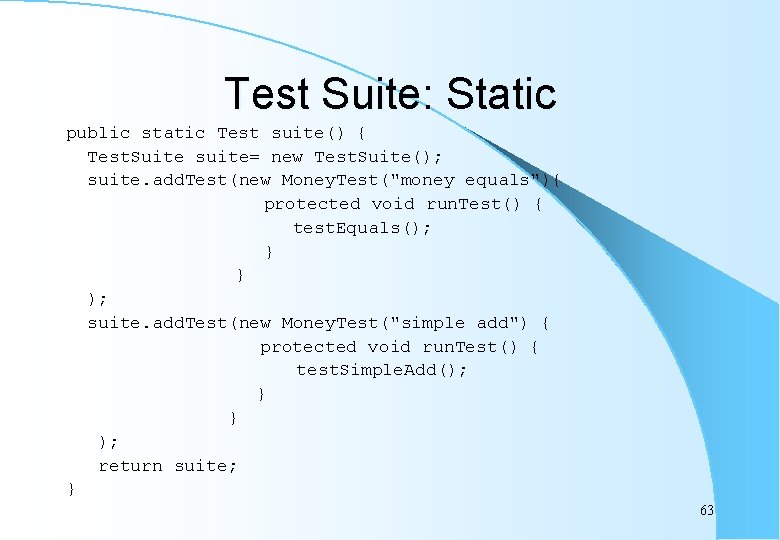

Test Suite: Static public static Test suite() { Test. Suite suite= new Test. Suite(); suite. add. Test(new Money. Test("money equals"){ protected void run. Test() { test. Equals(); } ); suite. add. Test(new Money. Test("simple add") { protected void run. Test() { test. Simple. Add(); } ); return suite; } 63

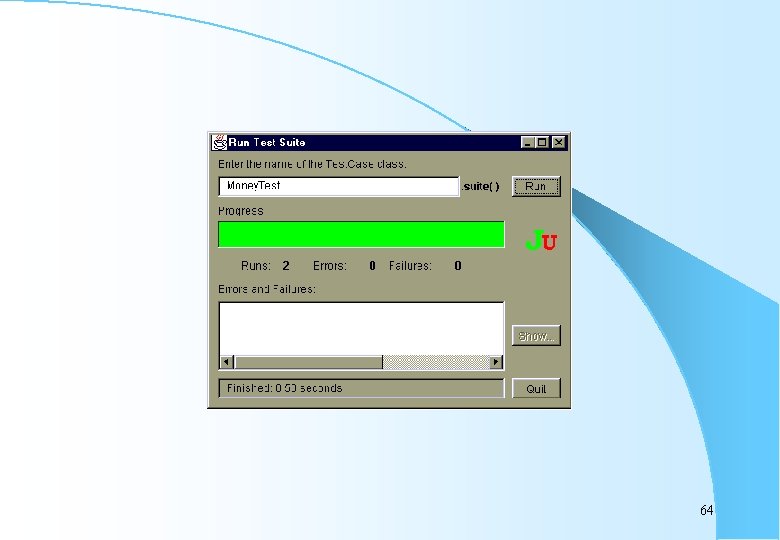

64

JUnit Review (1) l In general: development will go much smoother writing tests a little at a time when developing. l When coding the imagination of how the code will work. Capture thoughts in a test. l Test code is just like model code in working best if it is factored well. 65

JUnit Review (2) l Keeping old tests running is just as important as making new ones run. l The ideal is to always run all of your tests. l When you are struck by an idea, defer thinking about the implementation. First write the test. Then run it. Then work on the implementation. 66

Testing Practices (1) l Martin Fowler: "Whenever you are tempted to type something into a print statement or a debugger expression, write it as a test instead. ” l Only a fraction of the tests are actually useful. – Write tests that fail even though they should work, or tests that succeed even though they should fail. – Think of it is in cost/benefit terms. You want tests that pay you back with information. 67

Testing Practices (2) l Receive a reasonable return on your testing investment: – During Development. – During Debugging. l Caution: – Once you get them running, make sure they stay running. l Ideally, run every test in the suite every time you change a method. Practically, the suite will soon grow too large to run all the time. 68

Testing Practices (3) Try to optimise your set-up code so you can run all the tests. l Or, l – create special suites that contain all the tests that might possibly be affected by your current development. – run the suite every time you compile. – make sure you run every test at least once a day: overnight, during lunch, during one of those long meetings…. 69

References l Code Complete; Steve Mc. Connell, Microsoft Press. l The Elements of Java Style; Allan Vermeulen, SIGS Reference Library, Cambridge http: //www. javareport. com/ l http: //www. catapult-technologies. com/whitepapers/jlog/ l http: //www. junit. org/ l 70

Questions 71

- Slides: 71