Code Breakers Artifact 23 Museum Entrance Room Five

Code Breakers Artifact 23 Museum Entrance Room Five Code Makers Back Wall Artifact Enigma Code rtifact 22 Welcome to the Museum of WW 2 Secret Codes Curator’s Offices

Matt L’Etoile Curator’s Office Our beloved curator, Matt L’Etoile, was born in San Diego, California. Matt has been a museum curator for about 3 days now. He enjoys long walks on the beach, playing video games, and working hard to achieve his museum goals. Contact me at [Your linked email address] Return to Entry Note: Virtual museums were first introduced by educators at Keith Valley Middle School in Horsham, Pennsylvania. This template was designed by Dr. Christy Keeler. View the Educational Virtual Museums website for more information on this instructional technique.

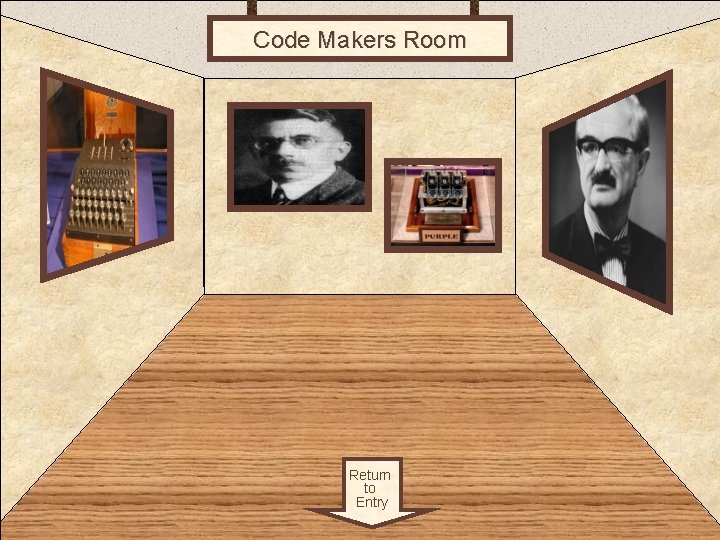

Code Makers Room 1 Return to Entry

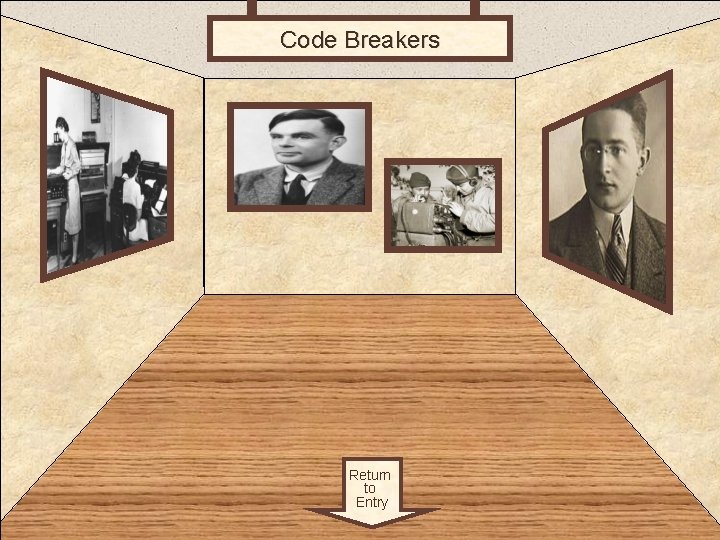

Code Breakers Room 2 Return to Entry

The Enigma Code Room 3 Artifact 10 Artifact 11 Return to Entry Artifact 12

Bletchley Park Room 4 Artifact 15 Return to Entry Artifact 16

![[Room 5] Room 5 Artifact 18 Artifact 17 Artifact 19 Artifact 21 Return to [Room 5] Room 5 Artifact 18 Artifact 17 Artifact 19 Artifact 21 Return to](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/04b728d48230f64512f4a63d49ba8594/image-7.jpg)

[Room 5] Room 5 Artifact 18 Artifact 17 Artifact 19 Artifact 21 Return to Entry Artifact 20

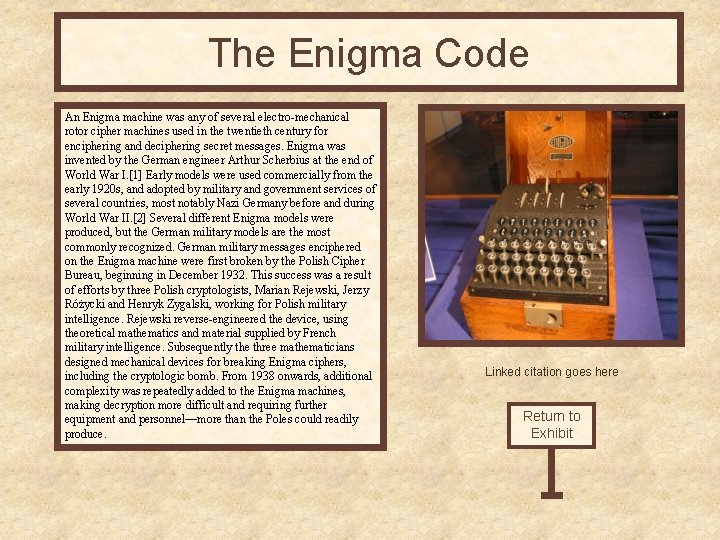

The Enigma Code An Enigma machine was any of several electro-mechanical rotor cipher machines used in the twentieth century for enciphering and deciphering secret messages. Enigma was invented by the German engineer Arthur Scherbius at the end of World War I. [1] Early models were used commercially from the early 1920 s, and adopted by military and government services of several countries, most notably Nazi Germany before and during World War II. [2] Several different Enigma models were produced, but the German military models are the most commonly recognized. German military messages enciphered on the Enigma machine were first broken by the Polish Cipher Bureau, beginning in December 1932. This success was a result of efforts by three Polish cryptologists, Marian Rejewski, Jerzy Różycki and Henryk Zygalski, working for Polish military intelligence. Rejewski reverse-engineered the device, using theoretical mathematics and material supplied by French military intelligence. Subsequently the three mathematicians designed mechanical devices for breaking Enigma ciphers, including the cryptologic bomb. From 1938 onwards, additional complexity was repeatedly added to the Enigma machines, making decryption more difficult and requiring further equipment and personnel—more than the Poles could readily produce. Linked citation goes here Return to Exhibit

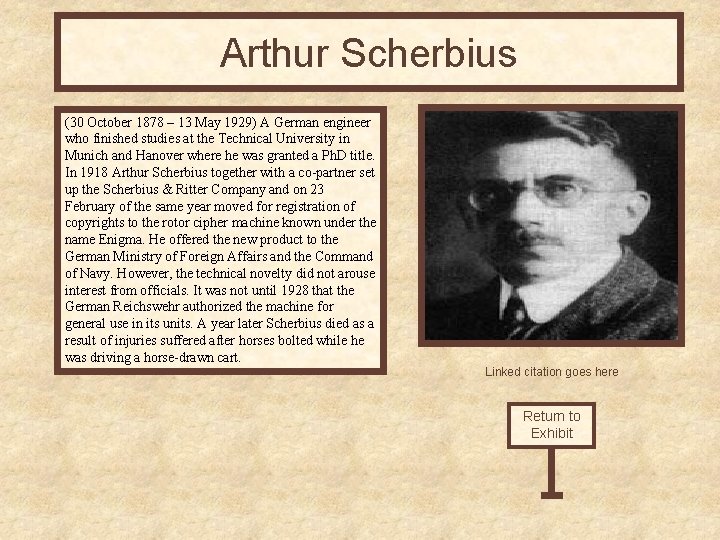

Arthur Scherbius (30 October 1878 – 13 May 1929) A German engineer who finished studies at the Technical University in Munich and Hanover where he was granted a Ph. D title. In 1918 Arthur Scherbius together with a co-partner set up the Scherbius & Ritter Company and on 23 February of the same year moved for registration of copyrights to the rotor cipher machine known under the name Enigma. He offered the new product to the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Command of Navy. However, the technical novelty did not arouse interest from officials. It was not until 1928 that the German Reichswehr authorized the machine for general use in its units. A year later Scherbius died as a result of injuries suffered after horses bolted while he was driving a horse-drawn cart. Linked citation goes here Return to Exhibit

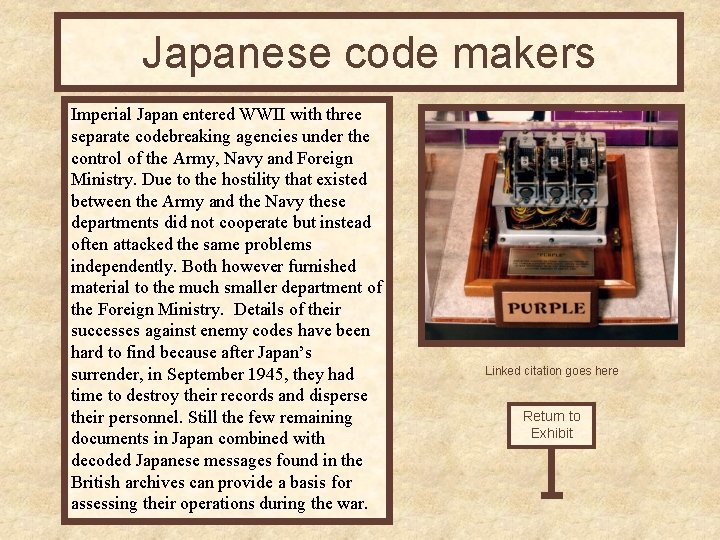

Japanese code makers Imperial Japan entered WWII with three separate codebreaking agencies under the control of the Army, Navy and Foreign Ministry. Due to the hostility that existed between the Army and the Navy these departments did not cooperate but instead often attacked the same problems independently. Both however furnished material to the much smaller department of the Foreign Ministry. Details of their successes against enemy codes have been hard to find because after Japan’s surrender, in September 1945, they had time to destroy their records and disperse their personnel. Still the few remaining documents in Japan combined with decoded Japanese messages found in the British archives can provide a basis for assessing their operations during the war. Linked citation goes here Return to Exhibit

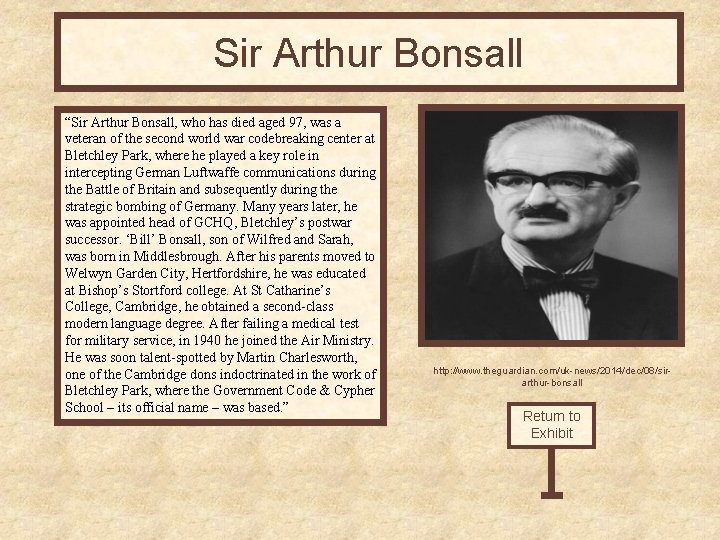

Sir Arthur Bonsall “Sir Arthur Bonsall, who has died aged 97, was a veteran of the second world war codebreaking center at Bletchley Park, where he played a key role in intercepting German Luftwaffe communications during the Battle of Britain and subsequently during the strategic bombing of Germany. Many years later, he was appointed head of GCHQ, Bletchley’s postwar successor. ‘Bill’ Bonsall, son of Wilfred and Sarah, was born in Middlesbrough. After his parents moved to Welwyn Garden City, Hertfordshire, he was educated at Bishop’s Stortford college. At St Catharine’s College, Cambridge, he obtained a second-class modern language degree. After failing a medical test for military service, in 1940 he joined the Air Ministry. He was soon talent-spotted by Martin Charlesworth, one of the Cambridge dons indoctrinated in the work of Bletchley Park, where the Government Code & Cypher School – its official name – was based. ” http: //www. theguardian. com/uk-news/2014/dec/08/sirarthur-bonsall Return to Exhibit

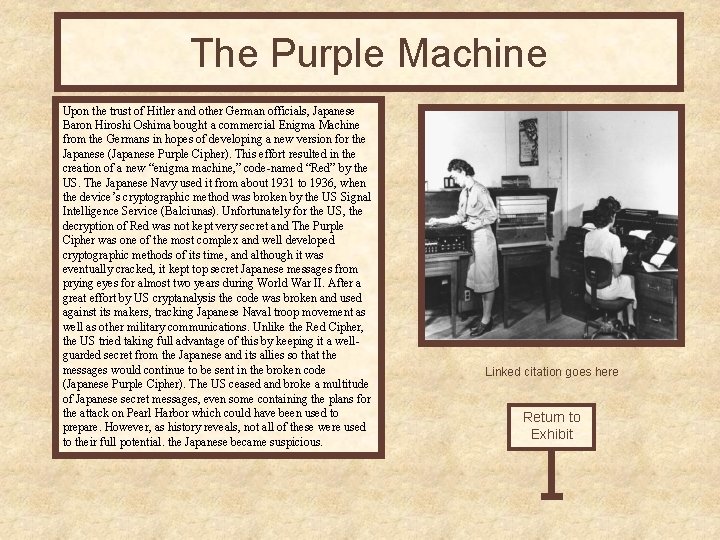

The Purple Machine Upon the trust of Hitler and other German officials, Japanese Baron Hiroshi Oshima bought a commercial Enigma Machine from the Germans in hopes of developing a new version for the Japanese (Japanese Purple Cipher). This effort resulted in the creation of a new “enigma machine, ” code-named “Red” by the US. The Japanese Navy used it from about 1931 to 1936, when the device’s cryptographic method was broken by the US Signal Intelligence Service (Balciunas). Unfortunately for the US, the decryption of Red was not kept very secret and The Purple Cipher was one of the most complex and well developed cryptographic methods of its time, and although it was eventually cracked, it kept top secret Japanese messages from prying eyes for almost two years during World War II. After a great effort by US cryptanalysis the code was broken and used against its makers, tracking Japanese Naval troop movement as well as other military communications. Unlike the Red Cipher, the US tried taking full advantage of this by keeping it a wellguarded secret from the Japanese and its allies so that the messages would continue to be sent in the broken code (Japanese Purple Cipher). The US ceased and broke a multitude of Japanese secret messages, even some containing the plans for the attack on Pearl Harbor which could have been used to prepare. However, as history reveals, not all of these were used to their full potential. the Japanese became suspicious. Linked citation goes here Return to Exhibit

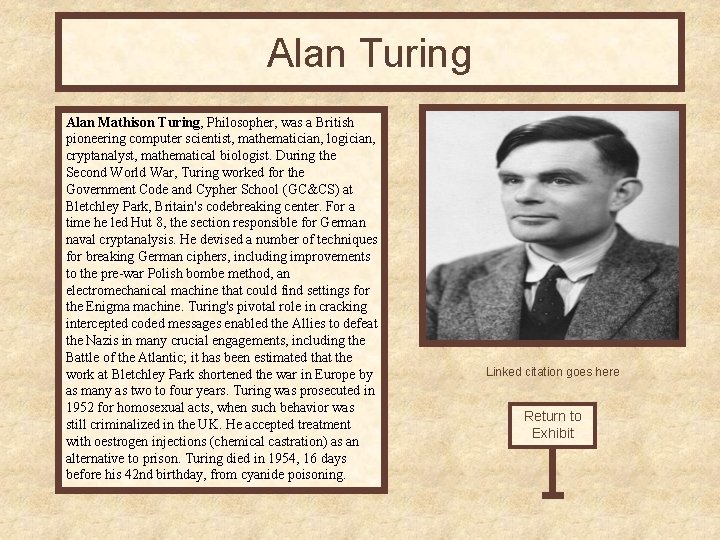

Alan Turing Alan Mathison Turing, Philosopher, was a British pioneering computer scientist, mathematician, logician, cryptanalyst, mathematical biologist. During the Second World War, Turing worked for the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park, Britain's codebreaking center. For a time he led Hut 8, the section responsible for German naval cryptanalysis. He devised a number of techniques for breaking German ciphers, including improvements to the pre-war Polish bombe method, an electromechanical machine that could find settings for the Enigma machine. Turing's pivotal role in cracking intercepted coded messages enabled the Allies to defeat the Nazis in many crucial engagements, including the Battle of the Atlantic; it has been estimated that the work at Bletchley Park shortened the war in Europe by as many as two to four years. Turing was prosecuted in 1952 for homosexual acts, when such behavior was still criminalized in the UK. He accepted treatment with oestrogen injections (chemical castration) as an alternative to prison. Turing died in 1954, 16 days before his 42 nd birthday, from cyanide poisoning. Linked citation goes here Return to Exhibit

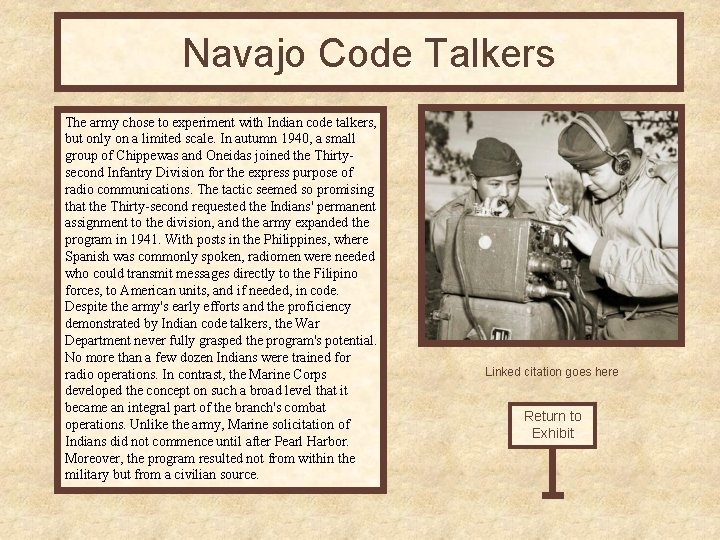

Navajo Code Talkers The army chose to experiment with Indian code talkers, but only on a limited scale. In autumn 1940, a small group of Chippewas and Oneidas joined the Thirtysecond Infantry Division for the express purpose of radio communications. The tactic seemed so promising that the Thirty-second requested the Indians' permanent assignment to the division, and the army expanded the program in 1941. With posts in the Philippines, where Spanish was commonly spoken, radiomen were needed who could transmit messages directly to the Filipino forces, to American units, and if needed, in code. Despite the army's early efforts and the proficiency demonstrated by Indian code talkers, the War Department never fully grasped the program's potential. No more than a few dozen Indians were trained for radio operations. In contrast, the Marine Corps developed the concept on such a broad level that it became an integral part of the branch's combat operations. Unlike the army, Marine solicitation of Indians did not commence until after Pearl Harbor. Moreover, the program resulted not from within the military but from a civilian source. Linked citation goes here Return to Exhibit

Marian Rejewski Now before going to Göttingen, Rejewski had attended a cryptology course which was put on by the Cipher Bureau for the best German speaking mathematics students. After he accepted the teaching position at Poznan University he began to work part-time for the Poznan Branch of the Cipher Bureau. They were interested in decoding intercepted German radio transmissions which were broadcast using a new cipher system. These messages were coded by an Enigma machine, but at this time even this fact was not known to the Poles. However, the Poznan Branch of the Cipher Bureau was disbanded in the summer of 1932 and, on 1 September 1932, Rejewski began to work fulltime at the Cipher Bureau in Warsaw. There he was joined by another two young Polish mathematicians, Jerzy Rozycki and Henryk Zygalski. Linked citation goes here Return to Exhibit

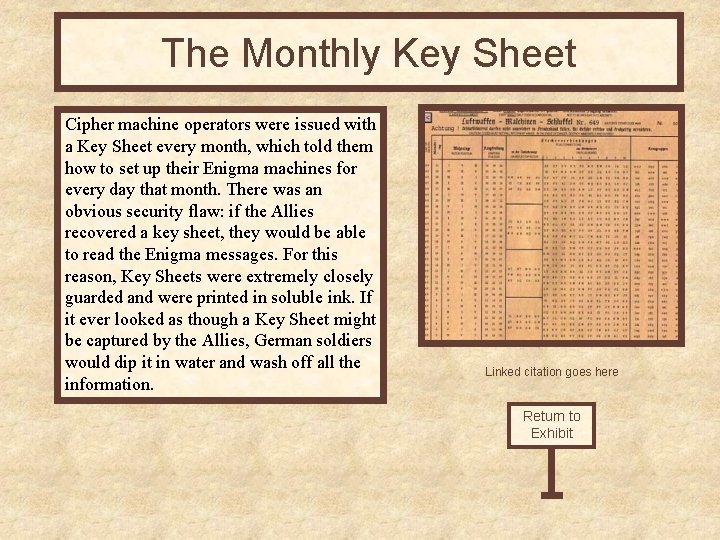

The Monthly Key Sheet Cipher machine operators were issued with a Key Sheet every month, which told them how to set up their Enigma machines for every day that month. There was an obvious security flaw: if the Allies recovered a key sheet, they would be able to read the Enigma messages. For this reason, Key Sheets were extremely closely guarded and were printed in soluble ink. If it ever looked as though a Key Sheet might be captured by the Allies, German soldiers would dip it in water and wash off all the information. Linked citation goes here Return to Exhibit

Artifact 10 Text goes here. Linked citation goes here Return to Exhibit

Artifact 11 Text goes here. Linked citation goes here Return to Exhibit

Artifact 12 Text goes here. Linked citation goes here Return to Exhibit

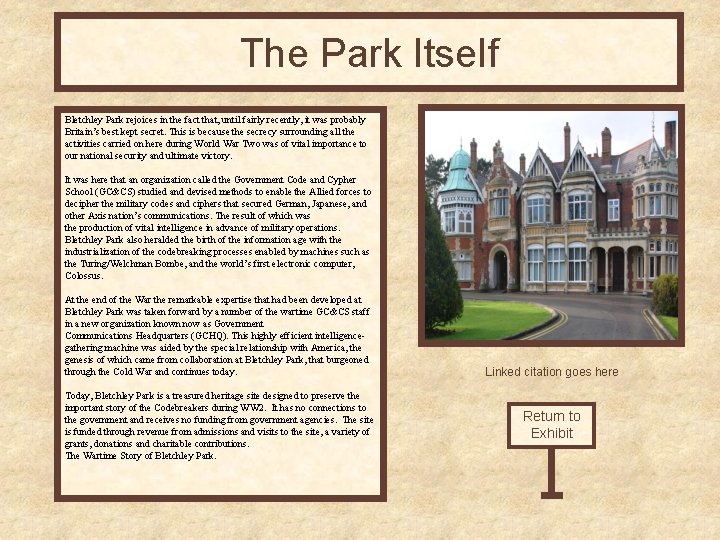

The Park Itself Bletchley Park rejoices in the fact that, until fairly recently, it was probably Britain’s best kept secret. This is because the secrecy surrounding all the activities carried on here during World War Two was of vital importance to our national security and ultimate victory. It was here that an organization called the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) studied and devised methods to enable the Allied forces to decipher the military codes and ciphers that secured German, Japanese, and other Axis nation’s communications. The result of which was the production of vital intelligence in advance of military operations. Bletchley Park also heralded the birth of the information age with the industrialization of the codebreaking processes enabled by machines such as the Turing/Welchman Bombe, and the world’s first electronic computer, Colossus. At the end of the War the remarkable expertise that had been developed at Bletchley Park was taken forward by a number of the wartime GC&CS staff in a new organization known now as Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ). This highly efficient intelligencegathering machine was aided by the special relationship with America, the genesis of which came from collaboration at Bletchley Park, that burgeoned through the Cold War and continues today. Today, Bletchley Park is a treasured heritage site designed to preserve the important story of the Codebreakers during WW 2. It has no connections to the government and receives no funding from government agencies. The site is funded through revenue from admissions and visits to the site, a variety of grants, donations and charitable contributions. The Wartime Story of Bletchley Park. Linked citation goes here Return to Exhibit

Artifact 14 Text goes here. Linked citation goes here Return to Exhibit

Artifact 15 Text goes here. Linked citation goes here Return to Exhibit

Artifact 16 Text goes here. Linked citation goes here Return to Exhibit

Artifact 17 Text goes here. Linked citation goes here Return to Exhibit

Artifact 18 Text goes here. Linked citation goes here Return to Exhibit

Artifact 19 Text goes here. Linked citation goes here Return to Exhibit

Artifact 20 Text goes here. Linked citation goes here Return to Exhibit

Artifact 21 Text goes here. Linked citation goes here Return to Exhibit

Artifact 22 Text goes here. Linked citation goes here Return to Entrance

Artifact 23 Text goes here. Linked citation goes here Return to Entrance

Back Wall Artifact Text goes here. Linked citation goes here Return to Exhibit

- Slides: 31