CMSC 281 Introduction to Complexity Theory Read Course

- Slides: 28

CMSC 281 Introduction to Complexity Theory • Read Course Information on the course web page http: //people. cs. uchicago. edu/~simon/TEACH/20 COMP/ (also follow links from there)

CMSC 281 Introduction to Complexity Theory Read Course Information on the course web page http: //people. cs. uchicago. edu/~simon/TEACH/20 COMP/ • We start with Computability • Sipser’s presentation assumes you are familiar with Finite Automata (and a bit of Formal Languages)

CMSC 281 Introduction to Complexity Theory Read Course Information on the course web page http: //people. cs. uchicago. edu/~simon/TEACH/20 COMP/ • We start with Computability • Sipser’s presentation assumes you are familiar with Finite Automata (and a bit of Formal Languages) This presentation does not. It covers roughly Chapter 3 of Part 2 – Computability Theory of the Sipser text.

CMSC 281 Introduction to Complexity Theory Read Course Information on the course web page http: //people. cs. uchicago. edu/~simon/TEACH/20 COMP/ • We start with Computability • Sipser’s presentation assumes you are familiar with Finite Automata (and a bit of Formal Languages) This presentation does not. It covers roughly Chapter 3 of Part 2 – Computability Theory of the Sipser text. You may still follow Sipser’s examples of Turing machine computations.

The Invention of Computers

The Invention of Computers The Turing Myth

The Invention of Computers (to be followed by) Things that are Impossible to Compute

What can we Compute? • What can computers do? Turing carefully analyzed (and settled) this question in his 1936 paper

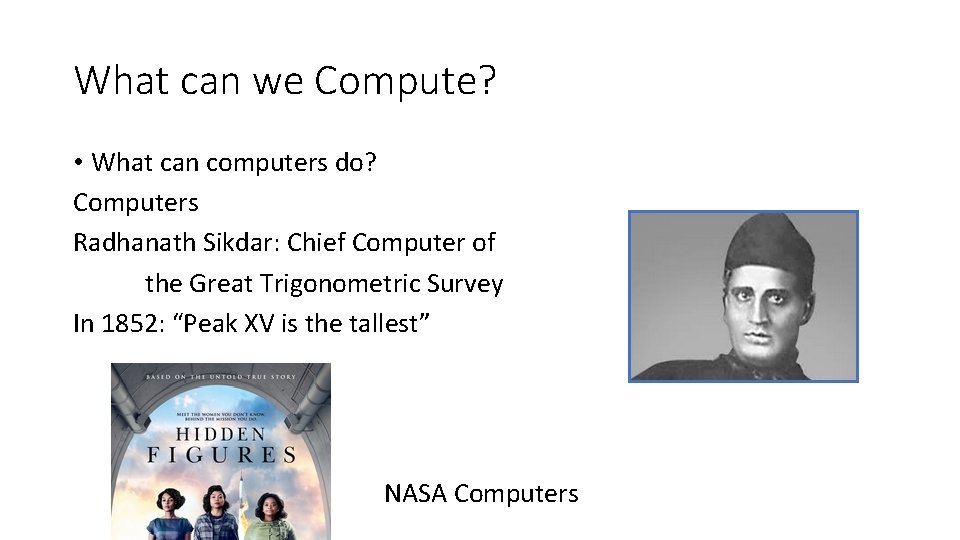

What can we Compute? • What can computers do? Computers Radhanath Sikdar: Chief Computer of the Great Trigonometric Survey

What can we Compute? • What can computers do? Computers Radhanath Sikdar: Chief Computer of the Great Trigonometric Survey In 1852: “Peak XV is the tallest”

What can we Compute? • What can computers do? Computers Radhanath Sikdar: Chief Computer of the Great Trigonometric Survey In 1852: “Peak XV is the tallest” NASA Computers

“Mechanical Computation” • Computation is done by following precise rules • Each operation is simple Example: adding 2 (long) numbers

Turing’s Model • All the computation is done on a 1 -dimensional tape The tape is “ 1 -way infinite”

Turing’s Model • All the computation is done on a 1 -dimensional tape The tape is “ 1 -way infinite” 1 st square, 2 nd square ….

Turing’s Model • All the computation is done on a (1 -dimensional) tape • Each square of the tape has one symbol – from a finite alphabet

Turing’s Model • All the computation is done on a (1 -dimensional) tape • Each square of the tape has one symbol – from a finite alphabet • At any time, the machine accesses a single square of its tape. “The machine has a head that is positioned over a square of the tape. It can read the symbol at this square”

Turing’s Model • All the computation is done on a (1 -dimensional) tape • Each square of the tape has one symbol – from a finite alphabet • At any time, the machine accesses a single square of its tape • The machine has a finite control –there is only a finite number of possible configurations (“states”) of the control.

Turing’s Model • All the computation is done on a (1 -dimensional) tape • Each square of the tape has one symbol – from a finite alphabet • At any time, the machine accesses a single square of its tape • The machine has a finite control –there is only a finite number of possible configurations (“states”) of the control. • Transition rules If the machine is in state p, scanning (“reading”) symbol a, it can • Change its state, • Rewrite the symbol scanned • Move its head to an adjacent square

Turing’s Model • All the computation is done on a (1 -dimensional) tape • Each square of the tape has one symbol – from a finite alphabet • At any time, the machine accesses a single square of its tape • The machine has a finite control –there is only a finite number of possible configurations (“states”) of the control. • Transition rules (“statement of a program”) If the machine is in state p, scanning (“reading”) symbol a, it can • Change its state, say to new state q • Rewrite the symbol scanned to another symbol, say b • Move its head to an adjacent square, say to the Left

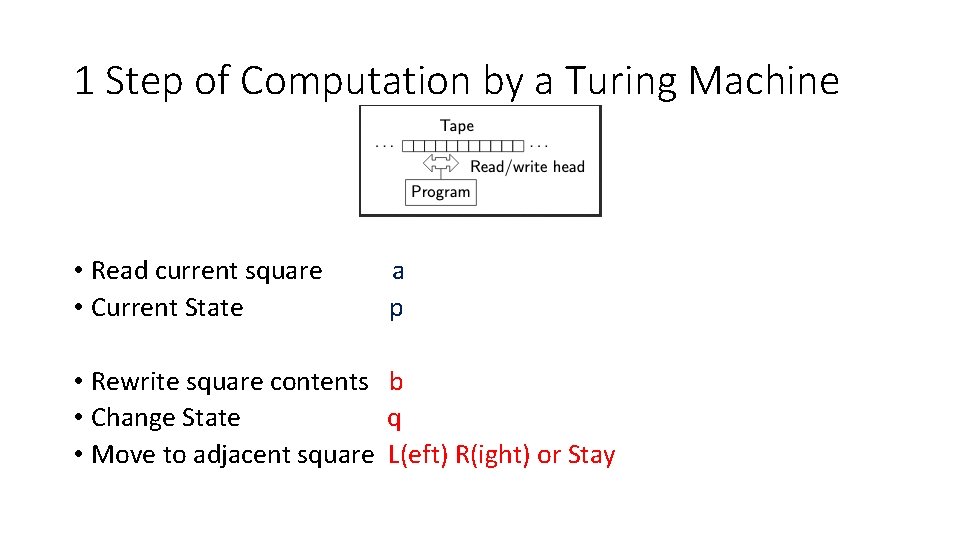

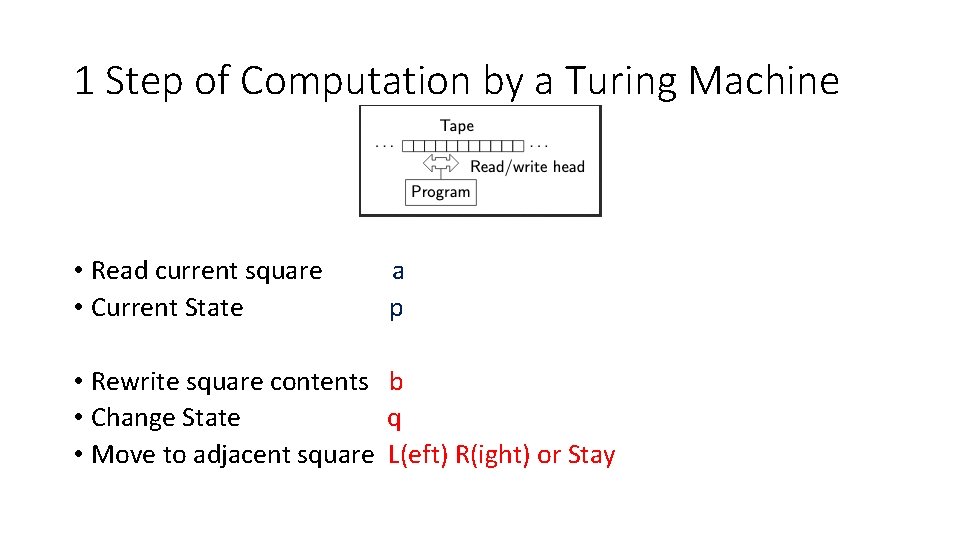

1 Step of Computation by a Turing Machine • Read current square a • Current State p • Rewrite square contents b • Change State q • Move to adjacent square L(eft) R(ight) or Stay

The Turing Machine has a Simple Description • 5 -tuples (p, a, q, b, movement ) For every machine this is a finite list. So specifying a Turing machine is a concrete, precise, mechanistic, finite description. No magic No “intuition”

Computation by Turing Machine • 5 -tuples (p, a, q, b, movement ) ”Program” For every machine this is a finite list. Computation: input written on tape, starting at the first square. All the squares to the right of the input contain a special blank symbol Machine scans the first (leftmost) square, in a special “begin computation” state q 0 Follow rules, until one of special states q. YES or q. NO reached

Computation by Turing Machine • 5 -tuples (p, a, q, b, movement ) ”Program” For every machine this is a finite list. Computation: input written on tape, machine scans first square, in special “begin computation” state q 0 Follow rules, until one of special states q. YES or q. NO reached Note that these rules do not exclude the computation going on indefinitely…

Computation by Turing Machine •

Computation by Turing Machine •

Computation by Turing Machine Some distraction: If you feel the need for something concrete as opposed to abstract definitions, watch the video https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=FTSAi. F 9 AHN 4 And if you feel the urge to build it, here is the adventure

Computation by Turing Machine It should be clear that if a predicate or a function is computable by a Turing machine, it is “mechanically computable”. In his 1936 paper, Turing claimed much more

Church –Turing Thesis Computable = Computable by a Turing Machine