CMSC 100 From the Bottom Up Its All

CMSC 100 From the Bottom Up: It's All Just Bits Adapted from slides provided by Dr. des. Jardins Robert Holder holder 1@umbc. edu Tuesday, September 13, 2009

Just Bits ¨ Inside the computer, all information is stored as bits · A “bit” is a single unit of information · Each “bit” is set to either zero or one ¨ How do we get complex systems like Google, Matlab, and our cell phone apps? Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 2

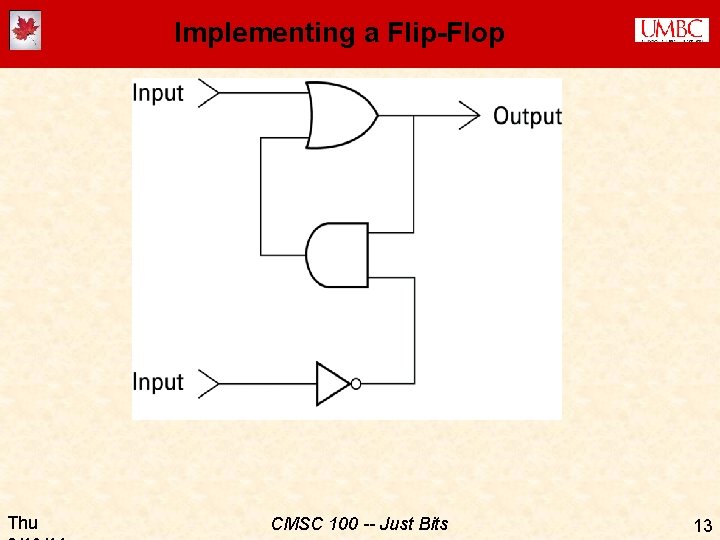

Storing Bits ¨ How are these “bits” stored in the computer? ¨ A bit is just an electrical signal or voltage (by convention: “low voltage” = 0; “high voltage” = 1) ¨ A circuit called a “flip-flop” can store a single bit · A flip-flop can be “set” (using an electrical signal) to either 0 or 1 · The flip-flop will hold that value until it receives a new signal telling it to change ¨ Bits can be operated on using gates (which “compute” a function of two or more bits) ¨ Later we’ll talk about how a flip-flop can be built of out gates Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 3

Manipulating Bits ¨ What does a bit value “mean”? · 0 = FALSE [off, no] · 1 = TRUE [on, yes] ¨ Just as in regular algebra, we can think of “variables” that represent a single bit · If X is a Boolean variable, then the value of X is either: � 0 [FALSE, off, no] or � 1 [TRUE, on, yes] ¨ In algebra, we have operations that we can perform on numbers: · Unary operations: Negate, square-root, … · Binary operations: Add, subtract, multiply, divide, … ¨ What are the operations you can imagine performing on bits? · Unary: ? ? · Binary: ? ? ¨ Thought problem: How many unary operations are there? How many binary operations? Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 4

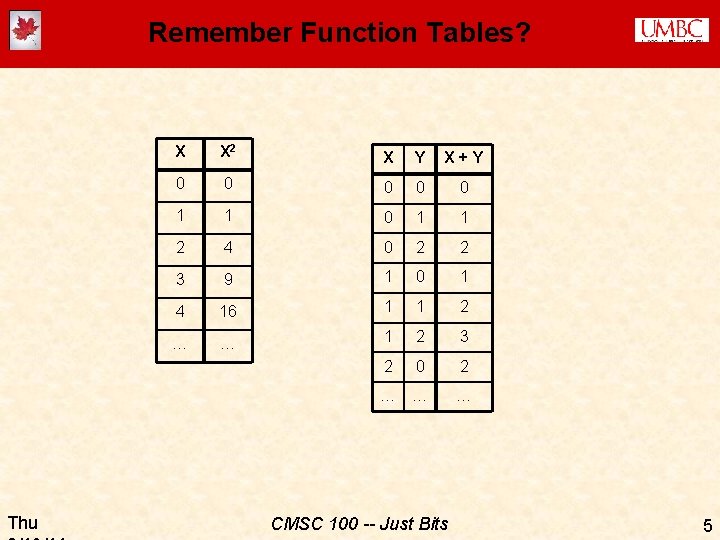

Remember Function Tables? Thu X X 2 X Y X+Y 0 0 0 1 1 2 4 0 2 2 3 9 1 0 1 4 16 1 1 2 … … 1 2 3 2 0 2 … … … CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 5

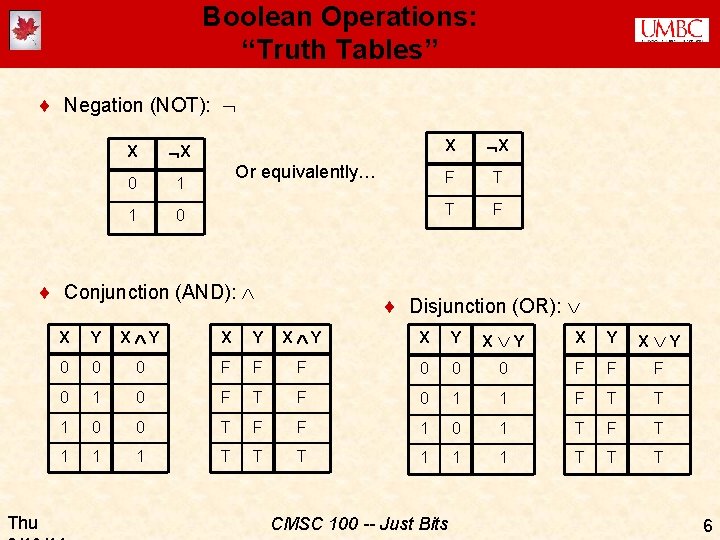

Boolean Operations: “Truth Tables” ¨ Negation (NOT): X X 0 1 1 0 Or equivalently… ¨ Conjunction (AND): Thu X X F T T F ¨ Disjunction (OR): X Y X Y 0 0 0 F F F 0 1 0 F T F 0 1 1 F T T 1 0 0 T F F 1 0 1 T F T 1 1 1 T T T CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 6

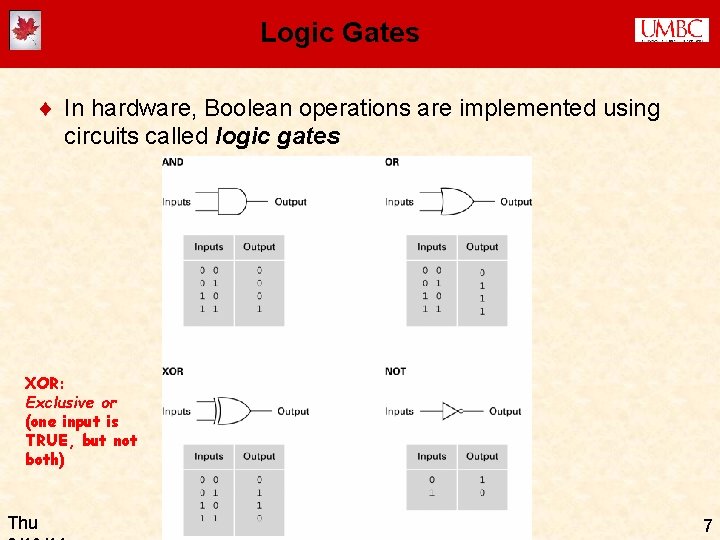

Logic Gates ¨ In hardware, Boolean operations are implemented using circuits called logic gates XOR: Exclusive or (one input is TRUE, but not both) Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 7

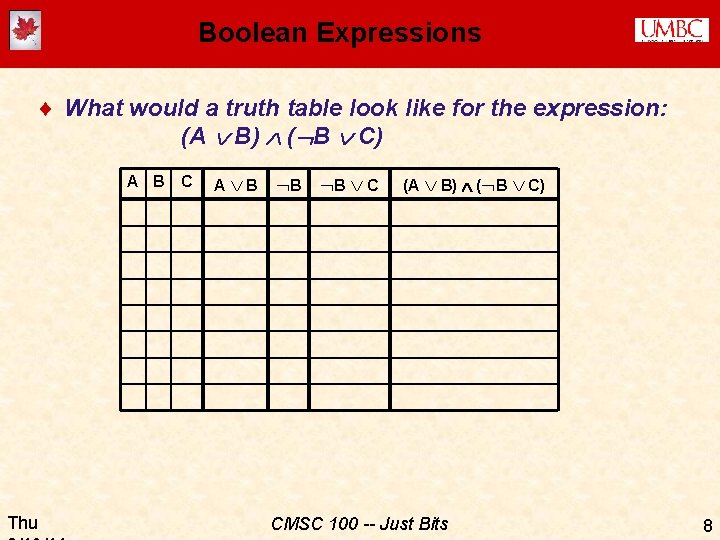

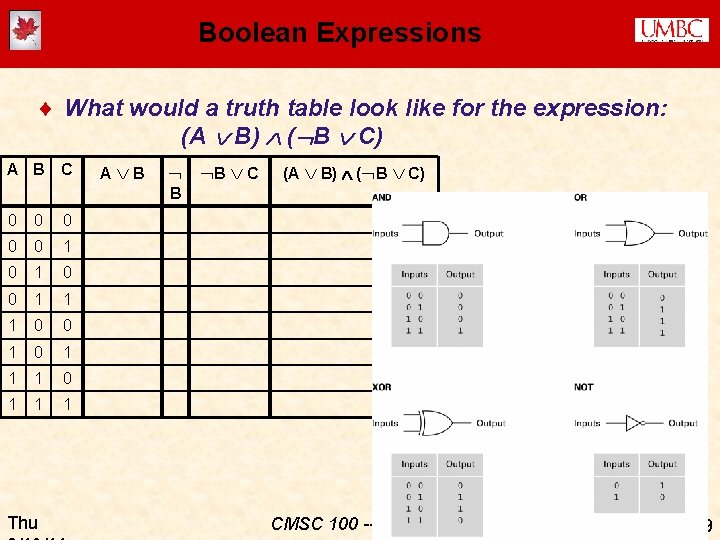

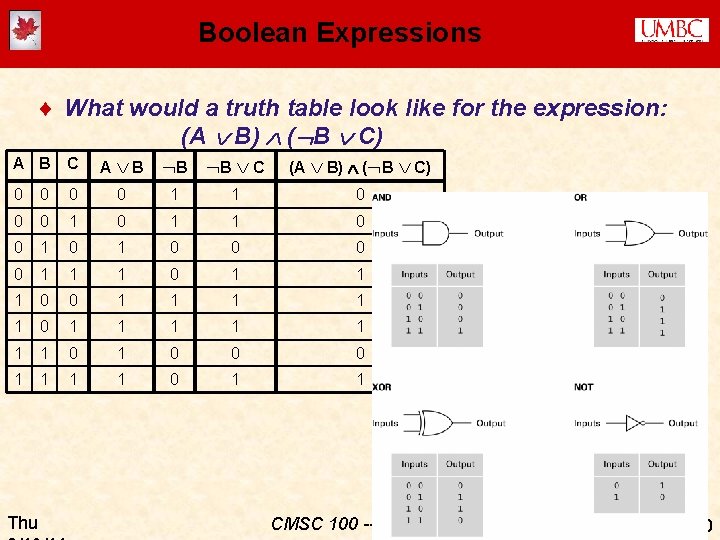

Boolean Expressions ¨ What would a truth table look like for the expression: (A B) ( B C) A B Thu C A B B B C (A B) ( B C) CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 8

Boolean Expressions ¨ What would a truth table look like for the expression: (A B) ( B C) A B C A B B C (A B) ( B C) B 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 9

Boolean Expressions ¨ What would a truth table look like for the expression: (A B) ( B C) A B C A B 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 Thu B B C (A B) ( B C) CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 10

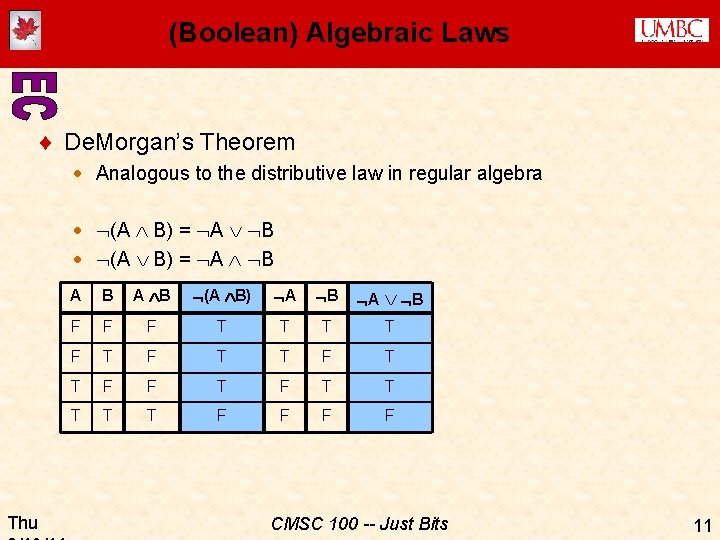

(Boolean) Algebraic Laws ¨ De. Morgan’s Theorem · Analogous to the distributive law in regular algebra · (A B) = A B Thu A B (A B) A B F F F T T F T T F F T T T F F CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 11

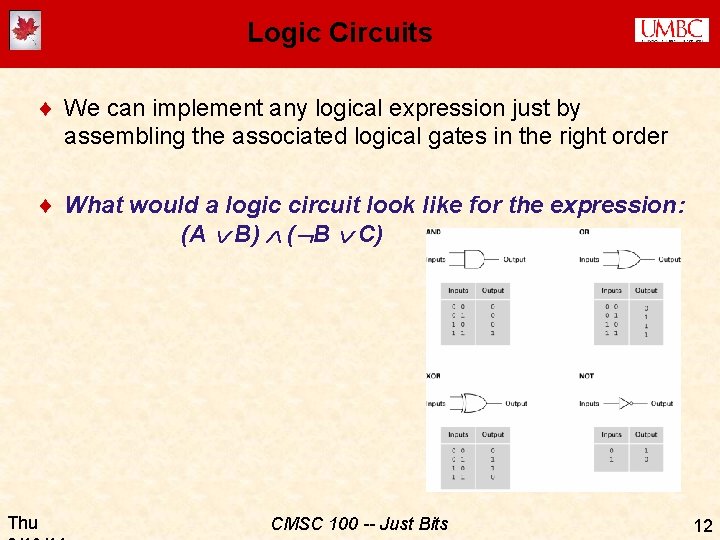

Logic Circuits ¨ We can implement any logical expression just by assembling the associated logical gates in the right order ¨ What would a logic circuit look like for the expression: (A B) ( B C) Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 12

Implementing a Flip-Flop Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 13

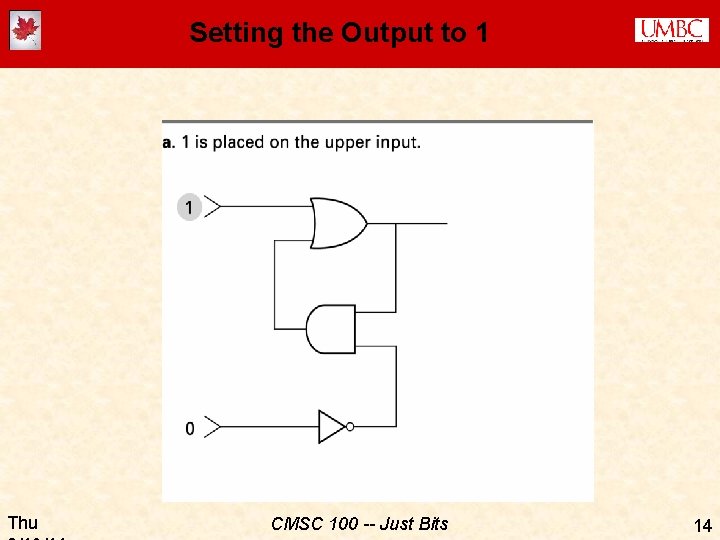

Setting the Output to 1 Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 14

Setting the Output to 1 (cont. ) Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 15

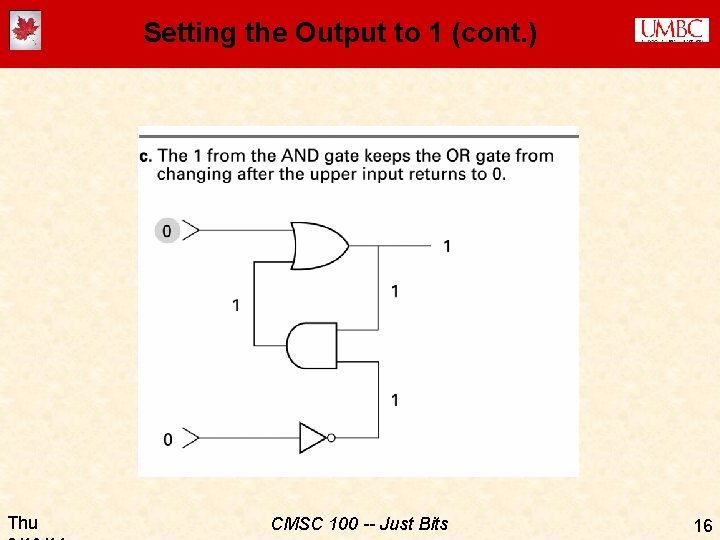

Setting the Output to 1 (cont. ) Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 16

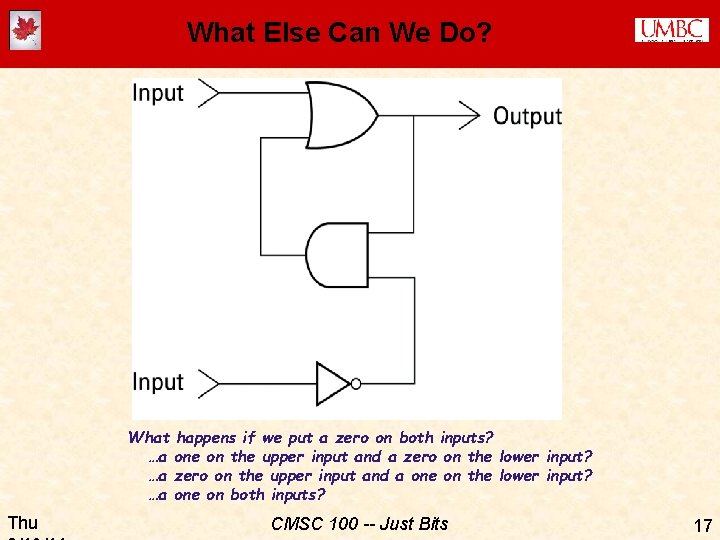

What Else Can We Do? What …a …a …a Thu happens if we put a zero on both inputs? one on the upper input and a zero on the lower input? zero on the upper input and a one on the lower input? one on both inputs? CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 17

Memory & Abstraction ¨ There are other circuits that will also implement a flip-flop · These are sometimes called SRM (Static Random Access Memory) · …meaning that once the circuit is “set” to 1 or 0, it will stay that way until a new signal is used to re-set it ¨ DRAM (Dynamic Random Access Memory): · Use a capacitor to store the charge (has to be refreshed periodically) ¨ BUT… ¨ Abstraction tells us that (for most purposes) it really doesn’t matter how we implement memory -- we just know that we can store (and retrieve) “a bit” at a time Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 18

Storing Information ¨ One bit can’t tell you much… (just 2 possible values) ¨ Usually we group 8 bits together into one “byte” ¨ How many possible values (combinations) are there for one byte? ¨ A byte can just be thought of as an 8 -digit binary (base 2) number · Michael Littman's octupus counting video ¨ Low-order or least significant bit == ones place · Next bit would be “ 10 s place” in base 10 -- what about base 2? ¨ High-order bit or most significant bite in a byte == ? ? place Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 19

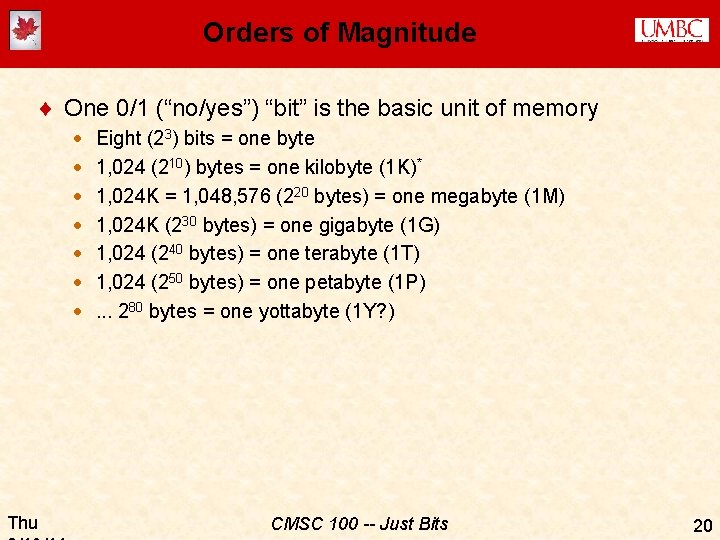

Orders of Magnitude ¨ One 0/1 (“no/yes”) “bit” is the basic unit of memory · · · · Thu Eight (23) bits = one byte 1, 024 (210) bytes = one kilobyte (1 K)* 1, 024 K = 1, 048, 576 (220 bytes) = one megabyte (1 M) 1, 024 K (230 bytes) = one gigabyte (1 G) 1, 024 (240 bytes) = one terabyte (1 T) 1, 024 (250 bytes) = one petabyte (1 P). . . 280 bytes = one yottabyte (1 Y? ) CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 20

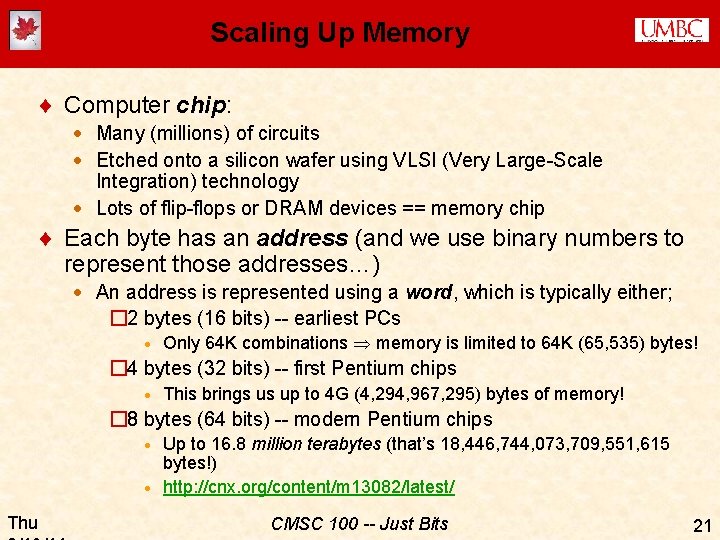

Scaling Up Memory ¨ Computer chip: · Many (millions) of circuits · Etched onto a silicon wafer using VLSI (Very Large-Scale Integration) technology · Lots of flip-flops or DRAM devices == memory chip ¨ Each byte has an address (and we use binary numbers to represent those addresses…) · An address is represented using a word, which is typically either; � 2 bytes (16 bits) -- earliest PCs · Only 64 K combinations memory is limited to 64 K (65, 535) bytes! � 4 bytes (32 bits) -- first Pentium chips · This brings us up to 4 G (4, 294, 967, 295) bytes of memory! � 8 bytes (64 bits) -- modern Pentium chips Up to 16. 8 million terabytes (that’s 18, 446, 744, 073, 709, 551, 615 bytes!) · http: //cnx. org/content/m 13082/latest/ · Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 21

Hexadecimal ¨ It would be very inconvenient to write out a 64 -bit address in binary: 0010100111010110111110001001011000011100110111100000 ¨ Instead, we group each set of 4 bits together into a hexadecimal (base 16) digit: · The digits are 0, 1, 2, …, 9, A (10), B (11), …, E (14), F (15) 0010 1001 1101 0110 1111 1000 1001 0110 0001 1100 1101 1110 0000 2 9 D 6 F 8 9 6 1 1 C D E 0 ¨ …which we write, by convention, with a “ 0 x” preceding the number to indicate it’s he. Xadecimal: · 0 x 29 D 6 F 89611 CDE 0 E 0 Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 22

Other Memory Concepts (read the book!!) ¨ Mass storage: hard disks, CDs, USB/flash drives… · · · Stores information without a constant supply of electricity Larger than RAM Slower than RAM Often removable Physically often more fragile than RAM ¨ CDs, hard drives, etc. actually spin and have tracks divided into sectors, read by a read/write head · · Seek time: Time to move head to the proper track Latency: Time to wait for the disk to rotate into place Access time: Seek + latency Transfer rate: How many bits/second can be read/written once you’ve found the right spot ¨ Flash memory: high capacity, no moving parts, but less reliable for long-term storage Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 23

Representing Information ¨ Positive integers: Just use the binary number system ¨ Negative integers, letters, images, … not so easy! · There are many different ways to represent information · Some are more efficient than others · … but once we’ve solved the representation problem, we can use that information without considering how it’s represented… via Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 24

![Representing Characters ¨ ASCII representation: one byte [actually 7 bits…] == one letter == Representing Characters ¨ ASCII representation: one byte [actually 7 bits…] == one letter ==](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/061beae3e74079007202af62700e2a91/image-25.jpg)

Representing Characters ¨ ASCII representation: one byte [actually 7 bits…] == one letter == an integer from 0 -128 ¨ No specific reason for this assignment of letters to integers! ¨ UNICODE is a popular 16 -bit representation that supports accented characters like é [Chart borrowed from ha. ckers. org] Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 25

Representing Integers ¨ Simplest idea (“ones’ complement”): · Use one bit for a “sign bit”: � 1 means negative, 0 means positive · The other bits are “complemented” (flipped) in a negative number · So, for example, +23 (in a 16 -bit word) is represented as: 00000010111 and -23 is represented as: 11111101000 · But there are two different ways to say “zero” (0000… and 1111…) · It’s tricky to do simple arithmetic operations like addition in the ones’ complement notation Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 26

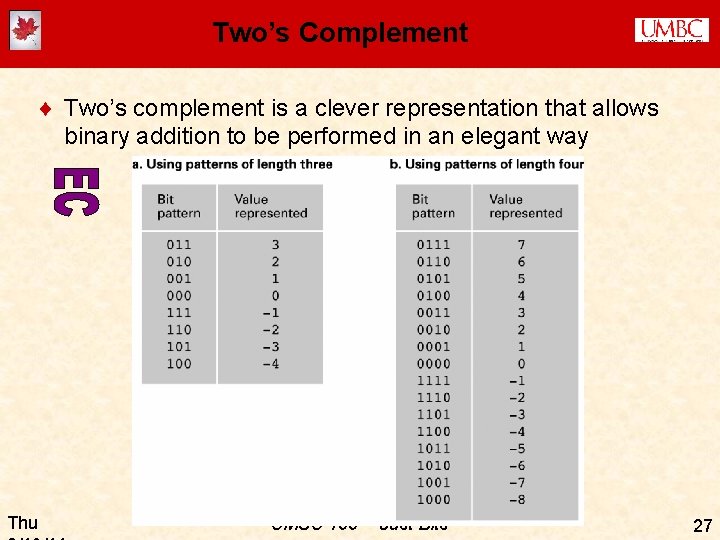

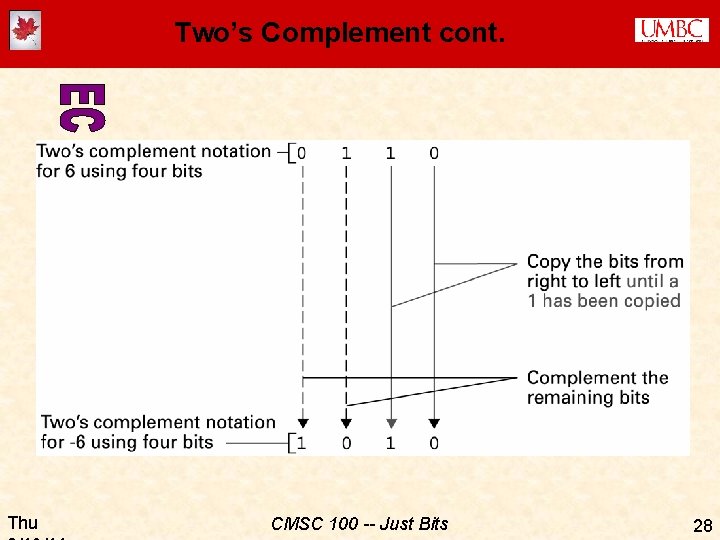

Two’s Complement ¨ Two’s complement is a clever representation that allows binary addition to be performed in an elegant way Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 27

Two’s Complement cont. Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 28

Floating Point Numbers ¨ Non-integers are a problem… ¨ Remember that any rational number can be represented as a fraction · …but we probably don’t want to do this, since �(a) we’d need to use two words for each number (i. e. , the numerator and the denominator) �(b) fractions are hard to manipulate (add, subtract, etc. ) ¨ Irrational numbers can’t be written down at all, of course ¨ Notice that any representation we choose will by definition have limited precision, since we can only represent 232 different values in a 32 -bit word · 1/3 isn’t exactly 1/3 (let’s try it on a calculator!) ¨ In general, we also lose precision (introduce errors) when we operate on floating point numbers ¨ You don’t need to know the details of how “floating point” numbers are represented Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 29

Summary: Main Ideas ¨ It’s all just bits ¨ Abstraction ¨ Boolean algebra · TRUE/FALSE · Truth tables · Logic gates ¨ Representing numbers · Hexadecimal representation · Ones’ (and two’s) complement · Floating point numbers (main issues) ¨ ASCII representation (main idea) ¨ Types and properties of RAM and mass storage Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 30

ACTIVITY (if time) ¨ Design a one-bit adder (i. e. , a logic circuit that adds two 1 -bit numbers together) �X + Y Z 2 Z 1 �Z 2 is needed since the result may be two binary digits long ¨ First let’s figure out the Boolean expression for each output… ¨ Then we’ll draw the logic circuit Thu CMSC 100 -- Just Bits 31

- Slides: 31