Clocks 1 Distributed Synchronization n Communication between processes

Clocks 1

Distributed Synchronization n Communication between processes in a distributed system can have unpredictable delays, processes can fail, messages may be lost. n Synchronization in distributed systems is harder than in centralized systems because the need for distributed algorithms. Properties of distributed algorithms: 1 The relevant information is scattered among multiple machines. 2 Processes make decisions based only on locally available information. 3 A single point of failure in the system should be avoided. 4 No common clock or other precise global time source exists. 2

Challenge: How to design schemes so that multiple systems can coordinate/synchronize to solve problems efficiently? 3

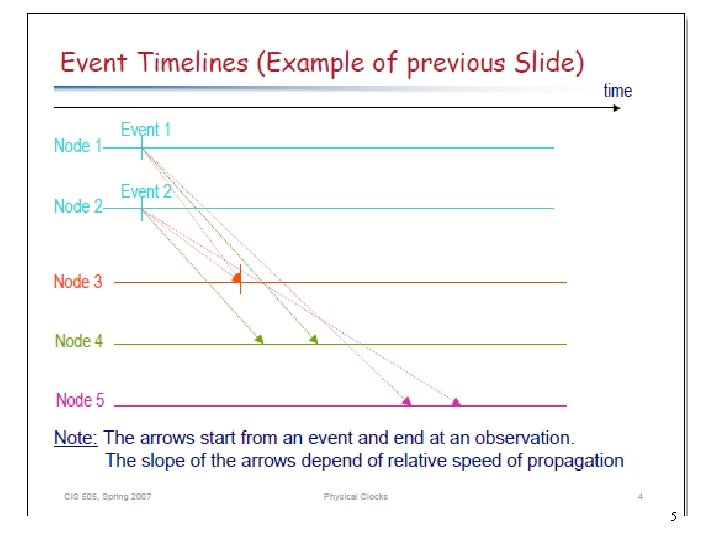

4

5

Absence of global clock n n No system-wide common clock (global clock). Reasons: q q Suppose a global clock exists. Two different processes can observe the clock at different times due to unpredictable message delays. Hence two different instances in physical time may be perceived as a single instance in physical time. If each process has a local clock and we try to synchronize them, they may drift due to technological limitations. Hence two different instances in physical time may be perceived as a single instance in physical time. Dept. of IT, Jadavpur University 6 6

Impact of the absence of global time n Concept of temporal ordering of events is ubiquitous. Suddenly it disappeared. n Scheduling of processes by an OS depends on the temporal order of process arrival. n Difficult to design and debug distributed programs since it is difficult to reason about temporal order of events in distributed systems. n Without a global clock, difficult to collect up-to-date information on the state of the entire system. Dept. of IT, Jadavpur University 7 7

Physical Clocks 8

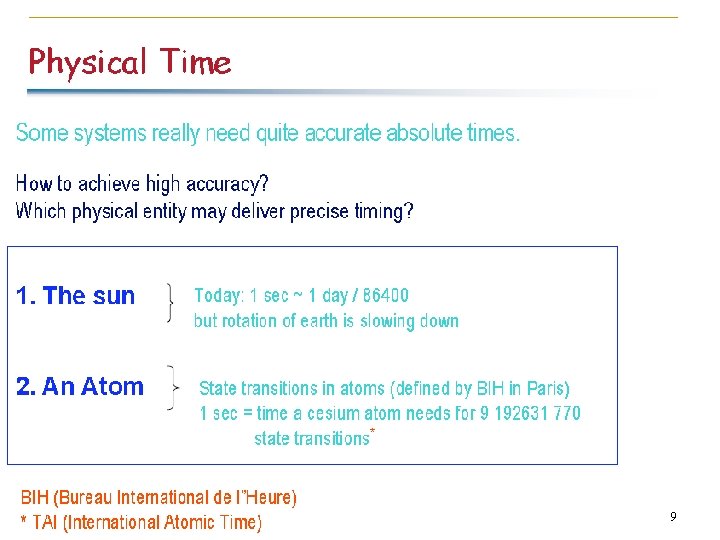

9

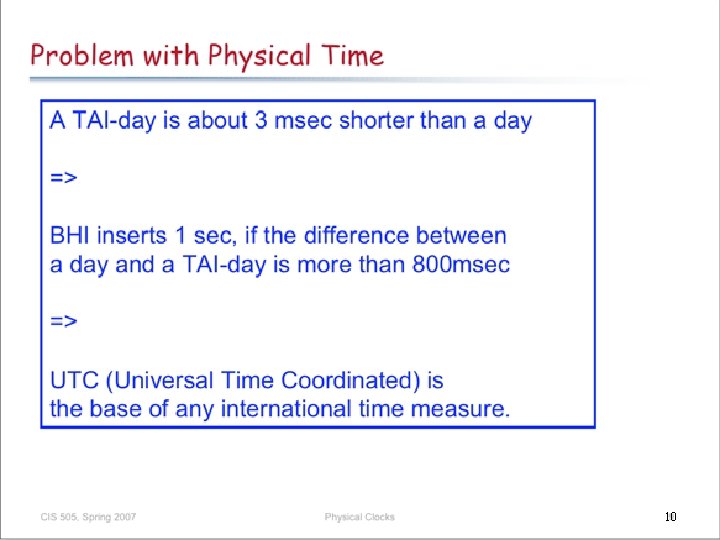

10

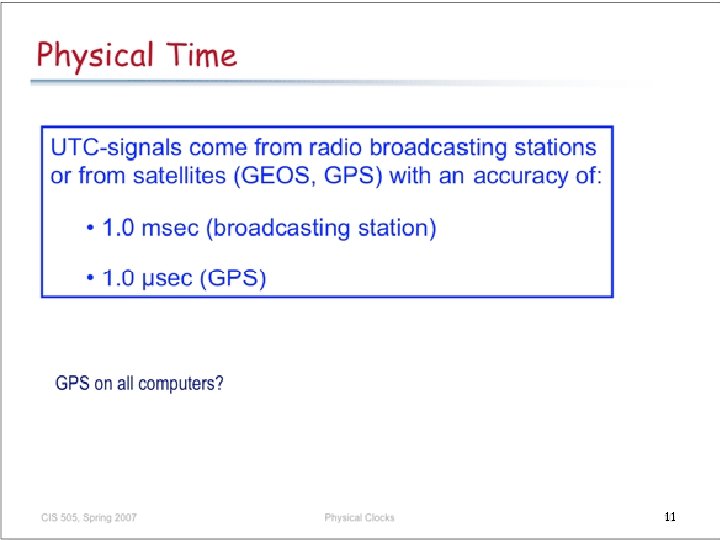

11

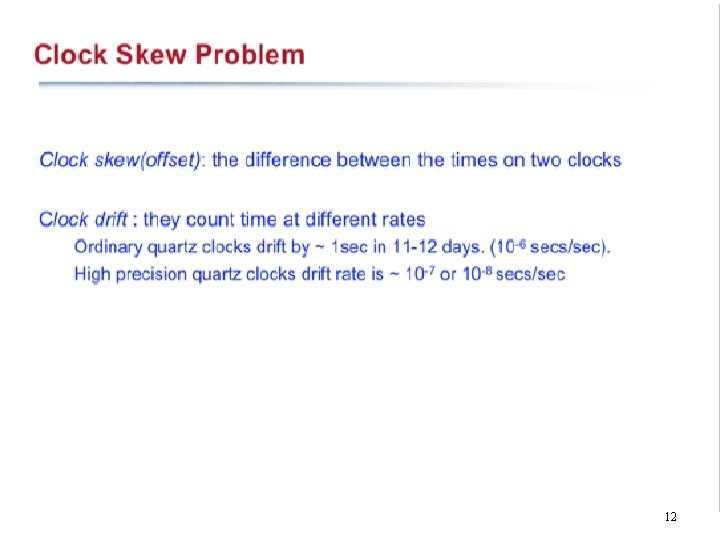

12

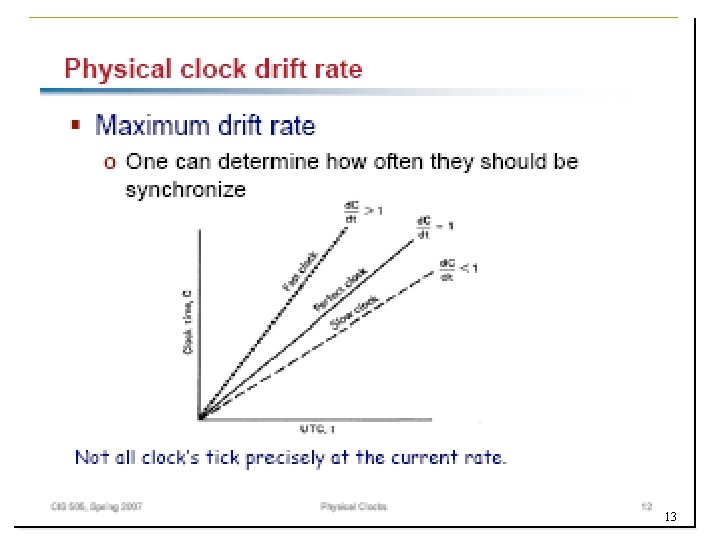

13

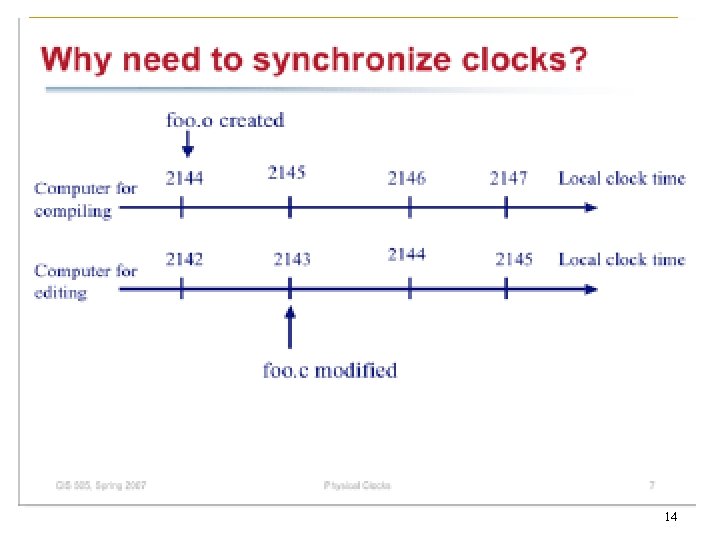

14

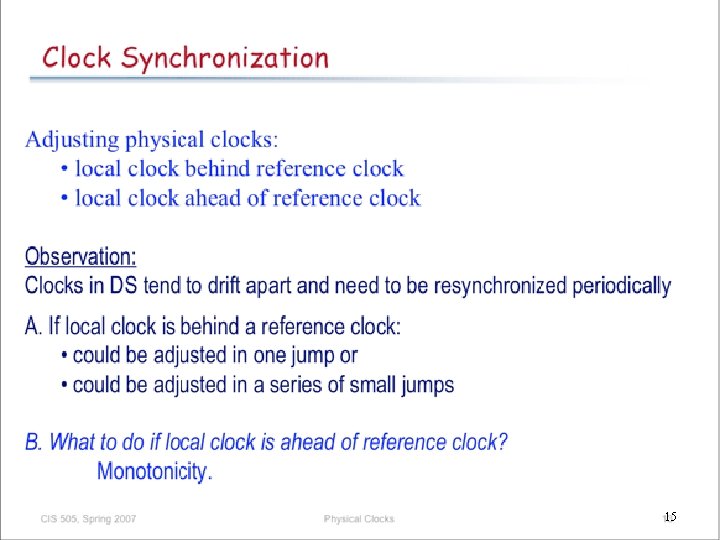

15

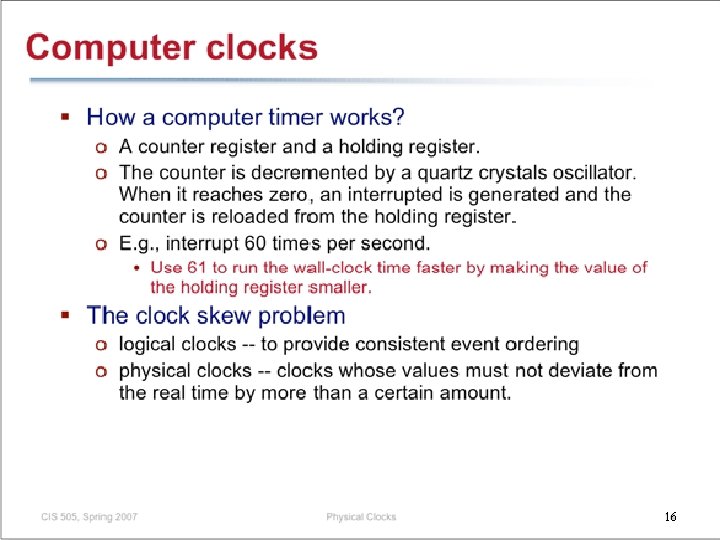

16

Logical Clocks 17

18

19

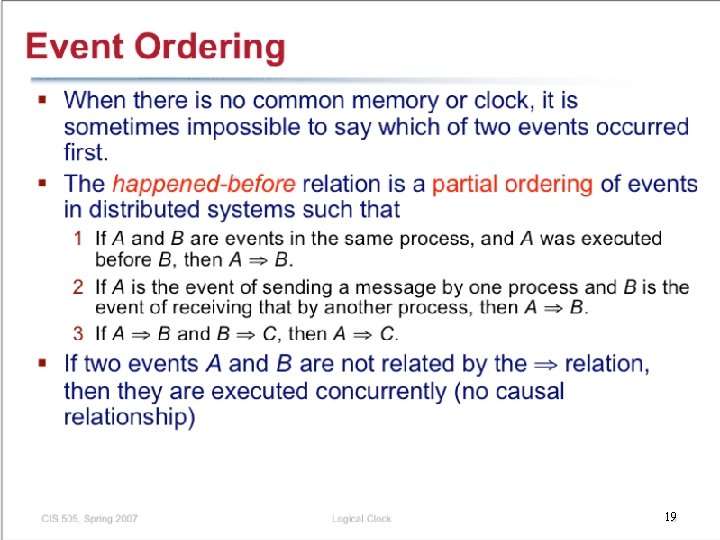

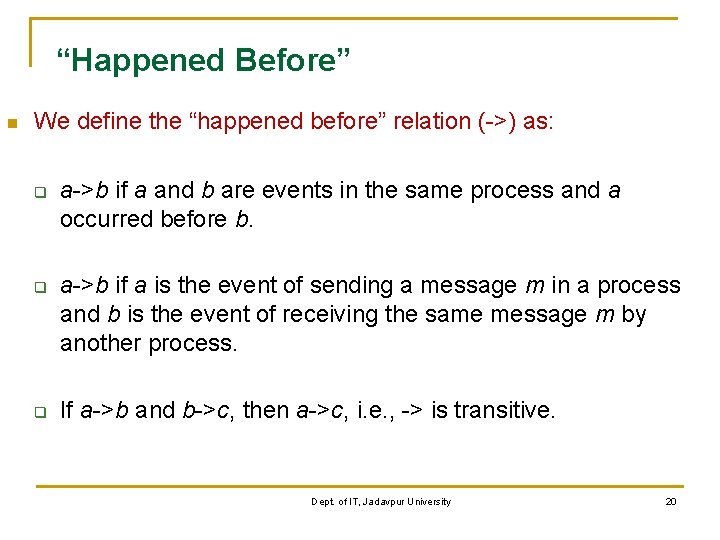

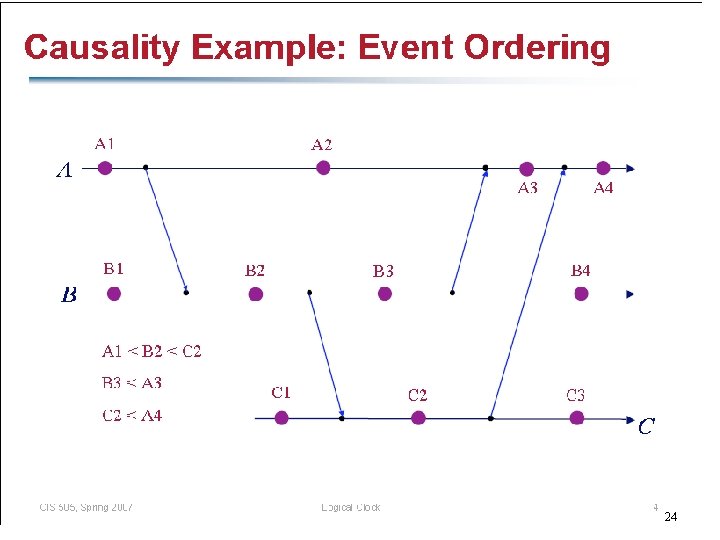

“Happened Before” n We define the “happened before” relation (->) as: q q q a->b if a and b are events in the same process and a occurred before b. a->b if a is the event of sending a message m in a process and b is the event of receiving the same message m by another process. If a->b and b->c, then a->c, i. e. , -> is transitive. Dept. of IT, Jadavpur University 20

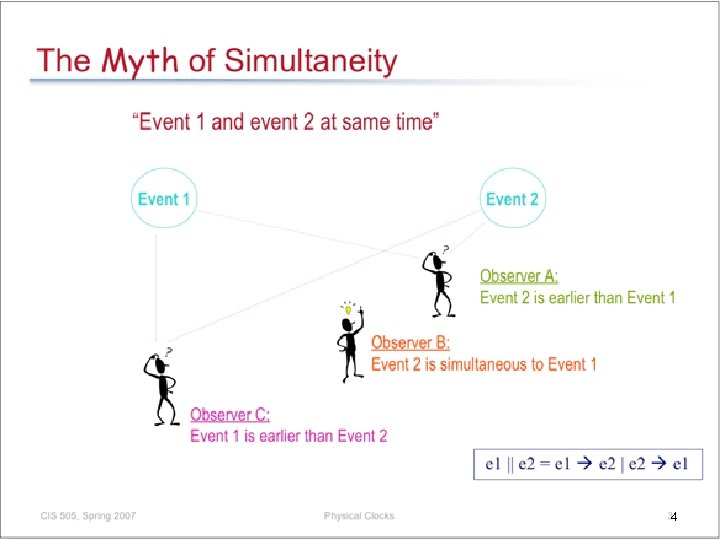

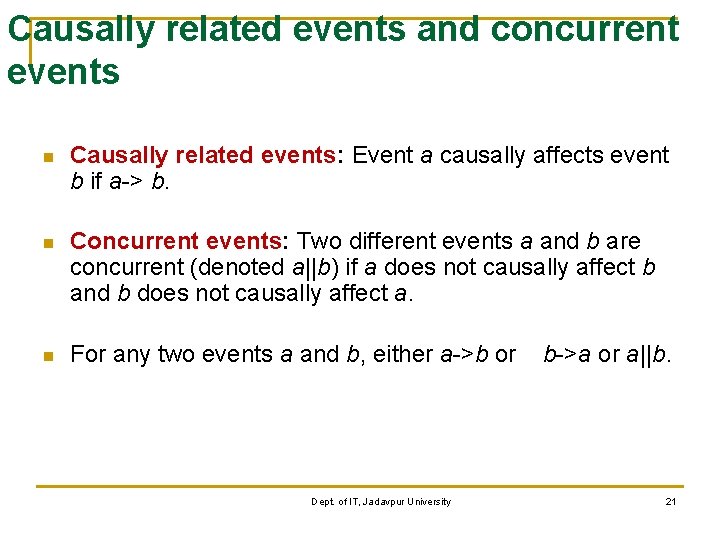

Causally related events and concurrent events n Causally related events: Event a causally affects event b if a-> b. n Concurrent events: Two different events a and b are concurrent (denoted a||b) if a does not causally affect b and b does not causally affect a. n For any two events a and b, either a->b or Dept. of IT, Jadavpur University b->a or a||b. 21

22

23

24

Lamport’s logical clock n There is a clock Ci at each process Pi. n The clock is a function that assigns a number Ci(a) to any event a called the timestamp of event a in process Pi. n It has no connection with physical time. n It assumes monotonically increasing values. Dept. of IT, Jadavpur University 25

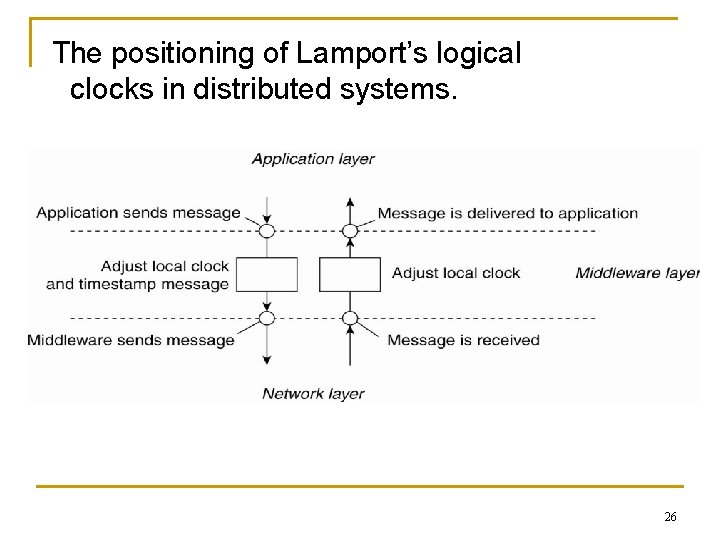

The positioning of Lamport’s logical clocks in distributed systems. 26

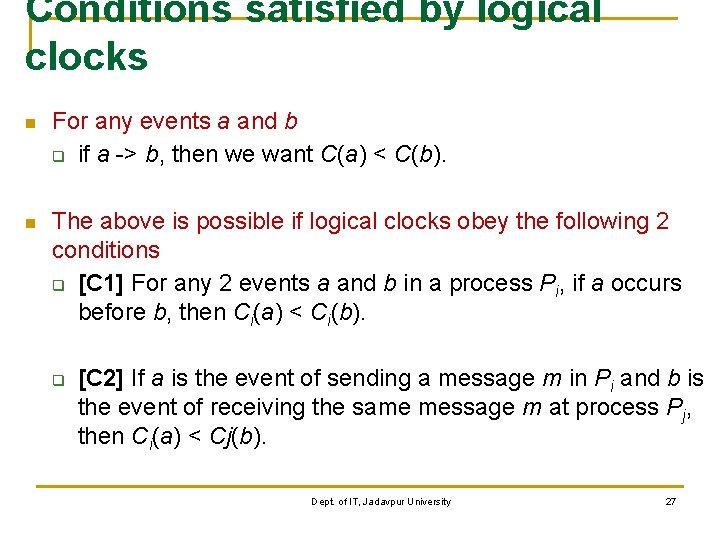

Conditions satisfied by logical clocks n For any events a and b q if a -> b, then we want C(a) < C(b). n The above is possible if logical clocks obey the following 2 conditions q [C 1] For any 2 events a and b in a process Pi, if a occurs before b, then Ci(a) < Ci(b). q [C 2] If a is the event of sending a message m in Pi and b is the event of receiving the same message m at process Pj, then Ci(a) < Cj(b). Dept. of IT, Jadavpur University 27

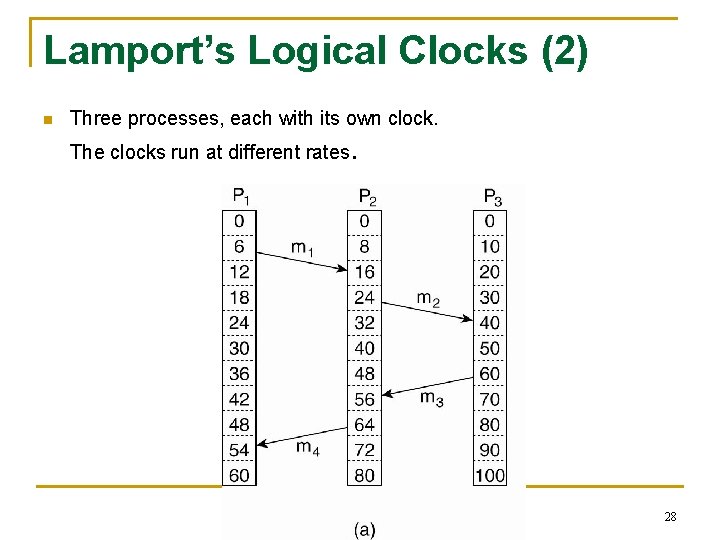

Lamport’s Logical Clocks (2) n Three processes, each with its own clock. The clocks run at different rates. 28

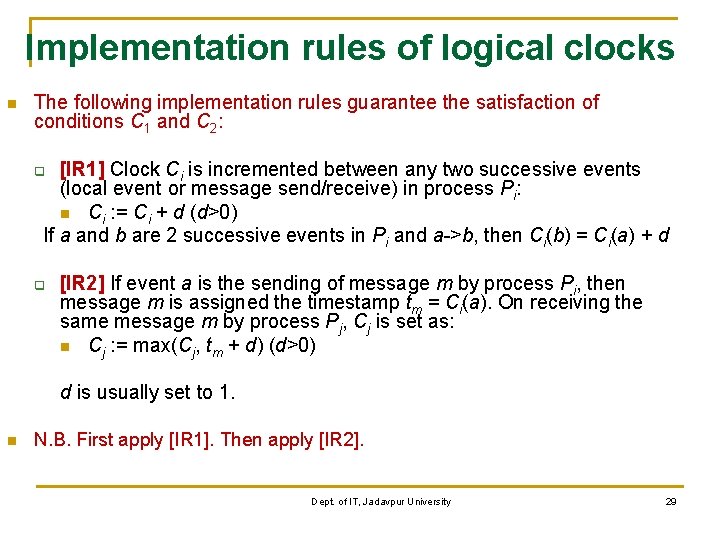

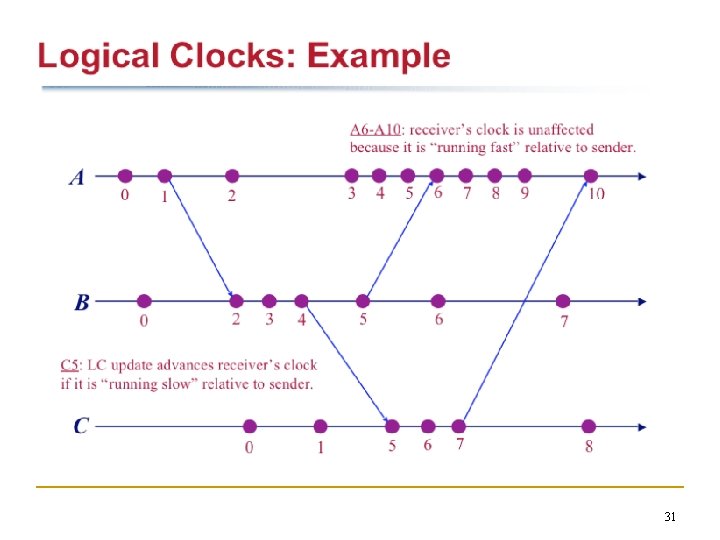

Implementation rules of logical clocks n The following implementation rules guarantee the satisfaction of conditions C 1 and C 2: [IR 1] Clock Ci is incremented between any two successive events (local event or message send/receive) in process Pi: n Ci : = Ci + d (d>0) If a and b are 2 successive events in Pi and a->b, then Ci(b) = Ci(a) + d q q [IR 2] If event a is the sending of message m by process Pi, then message m is assigned the timestamp tm = Ci(a). On receiving the same message m by process Pj, Cj is set as: n Cj : = max(Cj, tm + d) (d>0) d is usually set to 1. n N. B. First apply [IR 1]. Then apply [IR 2]. Dept. of IT, Jadavpur University 29

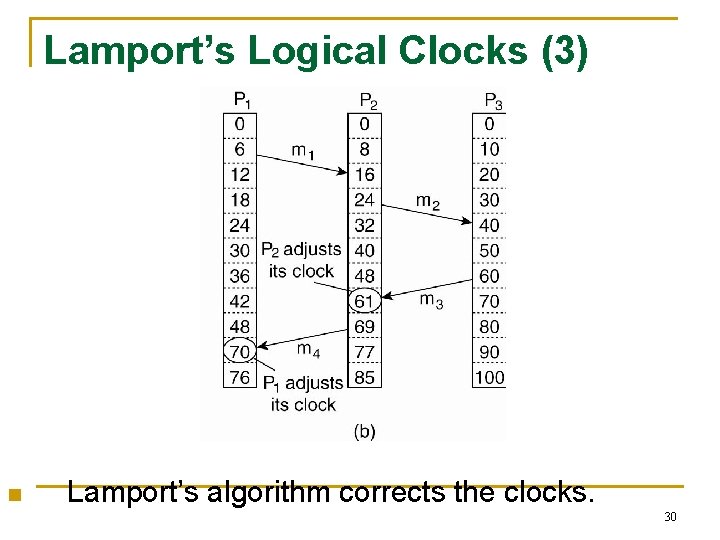

Lamport’s Logical Clocks (3) n Lamport’s algorithm corrects the clocks. 30

31

Partial order on events n Lamport’s “happened before” relation -> defines an irreflexible partial order (i. e. , antisymmetric, transitive) among the events. Dept. of IT, Jadavpur University 32

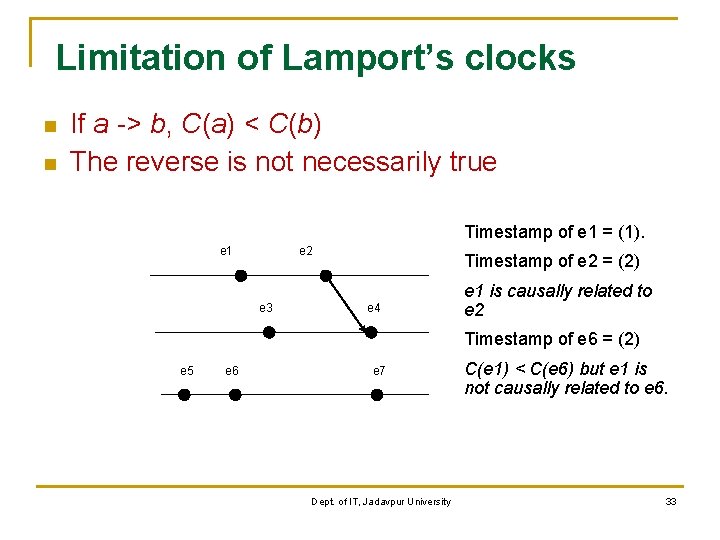

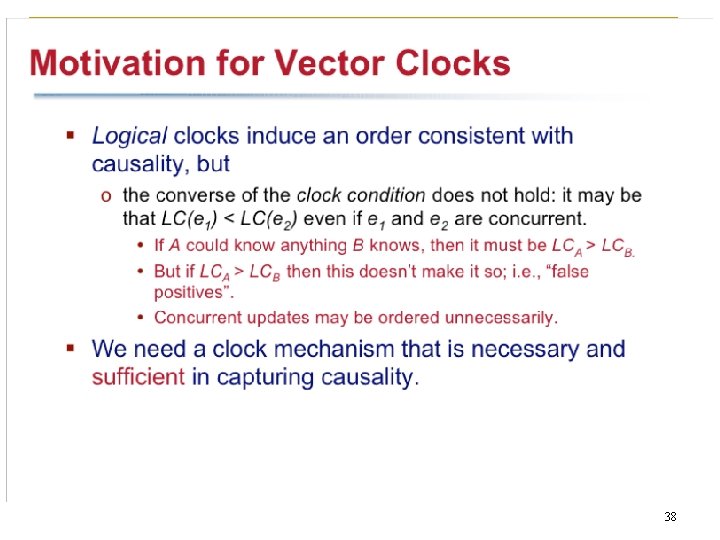

Limitation of Lamport’s clocks n n If a -> b, C(a) < C(b) The reverse is not necessarily true Timestamp of e 1 = (1). e 1 e 2 e 3 Timestamp of e 2 = (2) e 4 e 1 is causally related to e 2 Timestamp of e 6 = (2) e 5 e 6 e 7 Dept. of IT, Jadavpur University C(e 1) < C(e 6) but e 1 is not causally related to e 6. 33

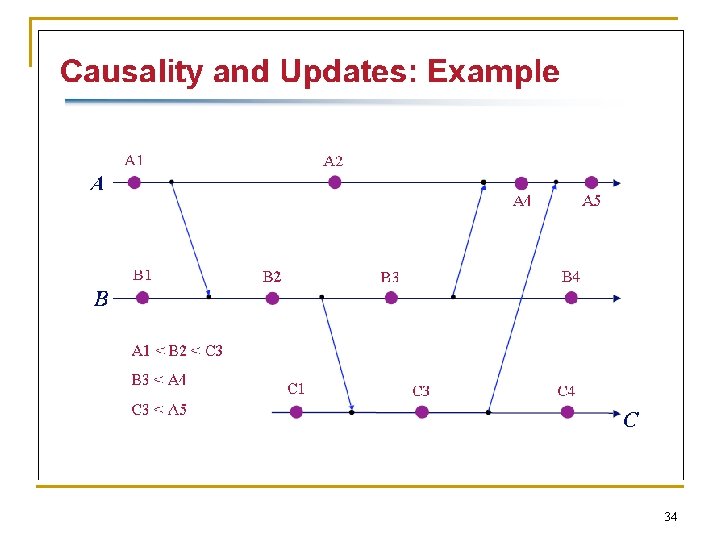

34

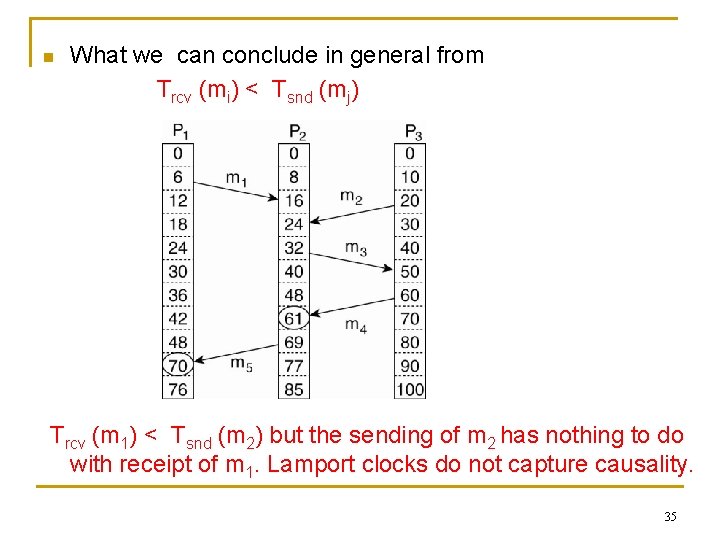

n What we can conclude in general from Trcv (mi) < Tsnd (mj) Trcv (m 1) < Tsnd (m 2) but the sending of m 2 has nothing to do with receipt of m 1. Lamport clocks do not capture causality. 35

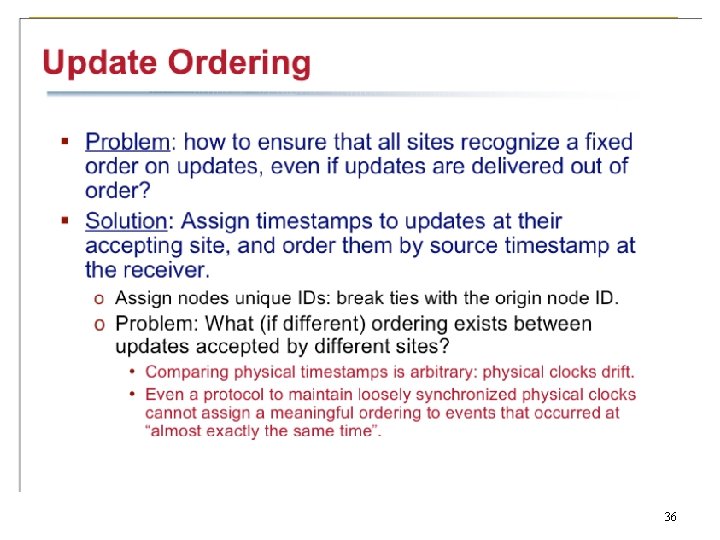

36

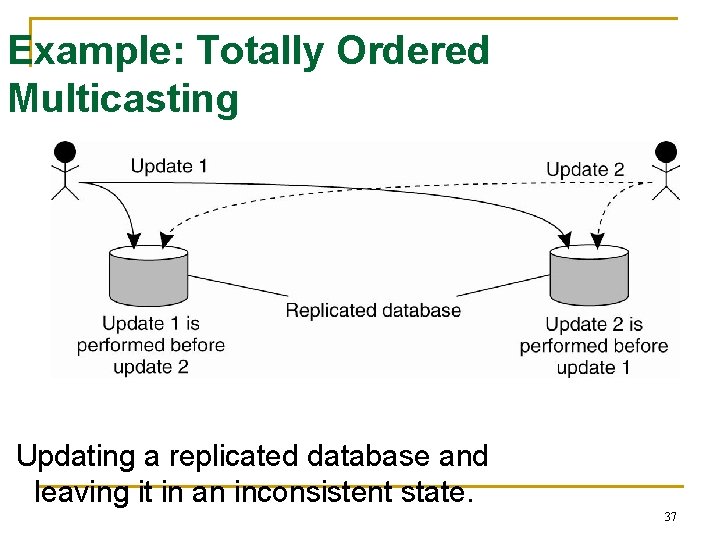

Example: Totally Ordered Multicasting Updating a replicated database and leaving it in an inconsistent state. 37

38

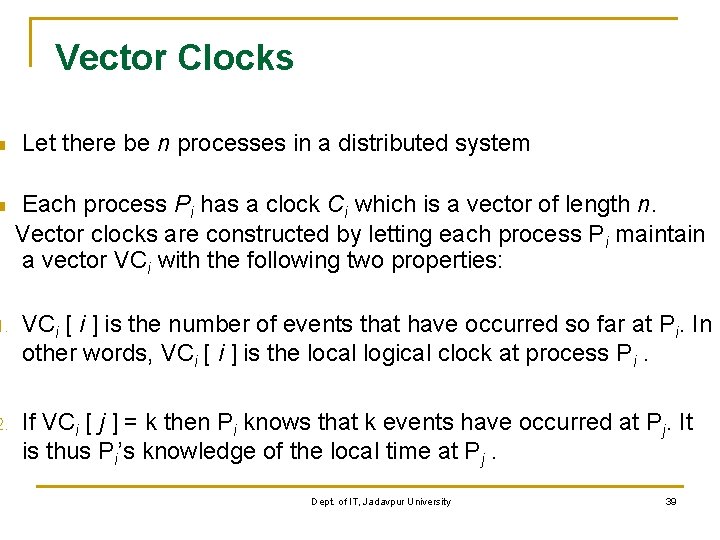

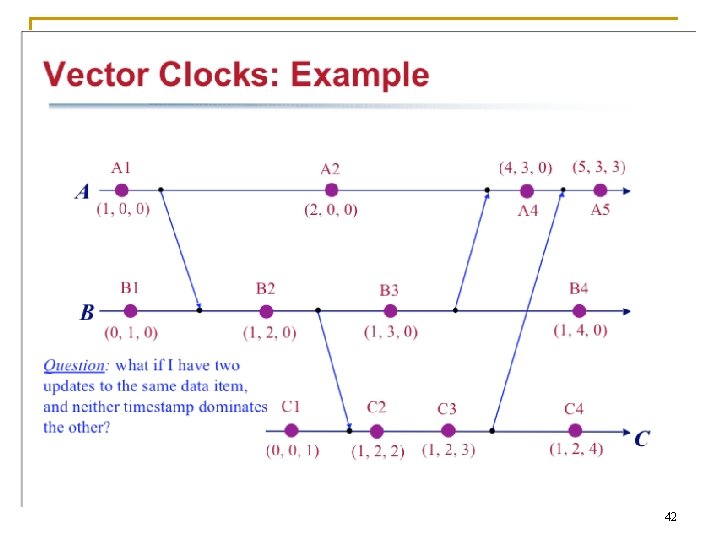

n n Vector Clocks Let there be n processes in a distributed system Each process Pi has a clock Ci which is a vector of length n. Vector clocks are constructed by letting each process Pi maintain a vector VCi with the following two properties: 1. VCi [ i ] is the number of events that have occurred so far at Pi. In other words, VCi [ i ] is the local logical clock at process Pi. 2. If VCi [ j ] = k then Pi knows that k events have occurred at Pj. It is thus Pi’s knowledge of the local time at Pj. Dept. of IT, Jadavpur University 39

![Vector clocks: Implementation n The implementation rules follow: q q [IR 1] Clock Ci Vector clocks: Implementation n The implementation rules follow: q q [IR 1] Clock Ci](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/63a96c8f18e51349282482797bdd50ab/image-40.jpg)

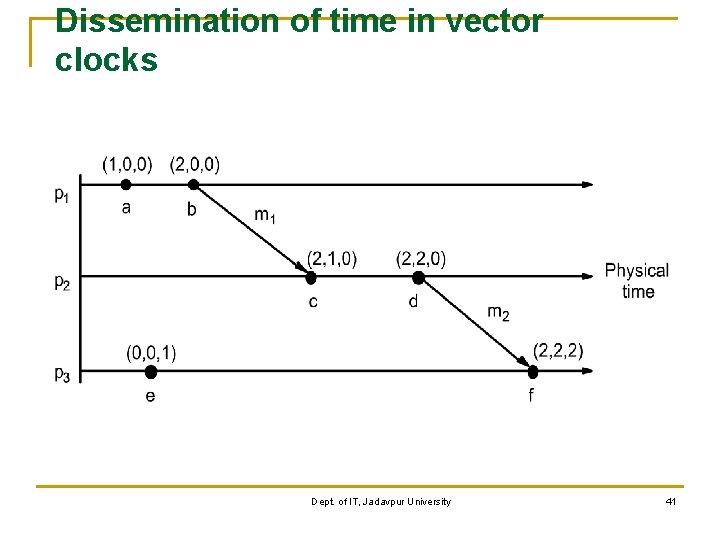

Vector clocks: Implementation n The implementation rules follow: q q [IR 1] Clock Ci is incremented between any 2 successive events (local event or message send/receive) in process Pi n Ci[i] : = Ci[i] + d (d>0) [IR 2] n If event a is the sending of message m by process Pi, then message m is assigned the timestamp tm : = Ci(a) n When message m is received by process Pj, then Cj is updated as for all k, Cj[k] : = max(Cj[k], tm[k]) n Comments: For each local event and each message send/receive, the logical clock advances. Each message carries as its timestamp the current vector clock value of the sender. The receiver updates its vector clock using the timestamp of the received message. n N. B. First apply [IR 1]. Then apply [IR 2]. Dept. of IT, Jadavpur University 40

Dissemination of time in vector clocks Dept. of IT, Jadavpur University 41

42

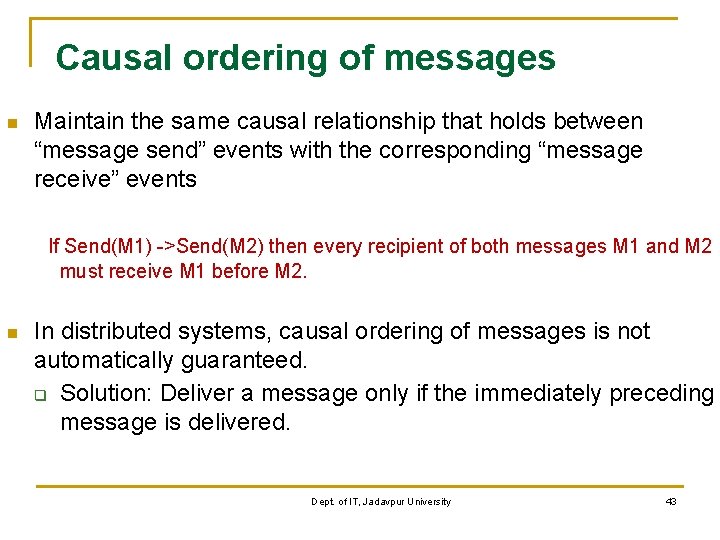

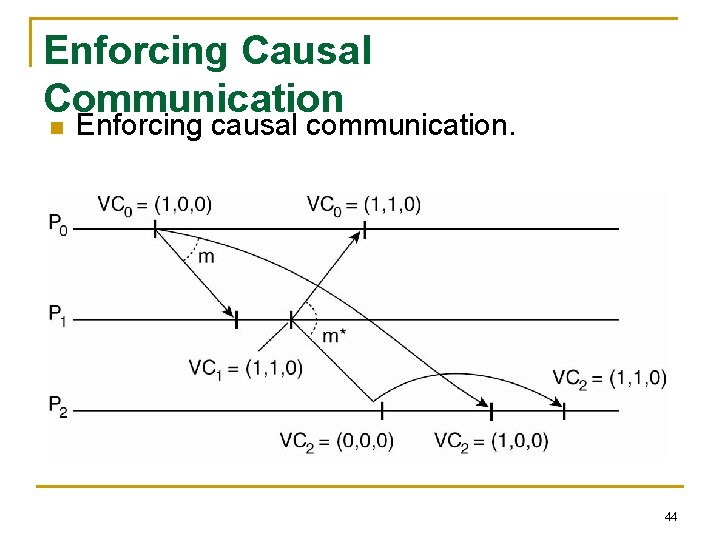

Causal ordering of messages n Maintain the same causal relationship that holds between “message send” events with the corresponding “message receive” events If Send(M 1) ->Send(M 2) then every recipient of both messages M 1 and M 2 must receive M 1 before M 2. n In distributed systems, causal ordering of messages is not automatically guaranteed. q Solution: Deliver a message only if the immediately preceding message is delivered. Dept. of IT, Jadavpur University 43

Enforcing Causal Communication n Enforcing causal communication. 44

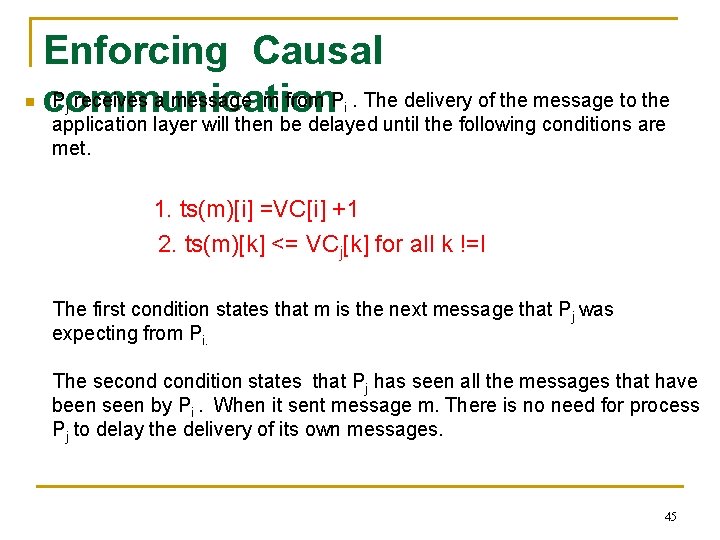

n Enforcing Causal P receives a message m from P. The delivery of the message to the communication application layer will then be delayed until the following conditions are j i met. 1. ts(m)[i] =VC[i] +1 2. ts(m)[k] <= VCj[k] for all k !=I The first condition states that m is the next message that Pj was expecting from Pi. The secondition states that Pj has seen all the messages that have been seen by Pi. When it sent message m. There is no need for process Pj to delay the delivery of its own messages. 45

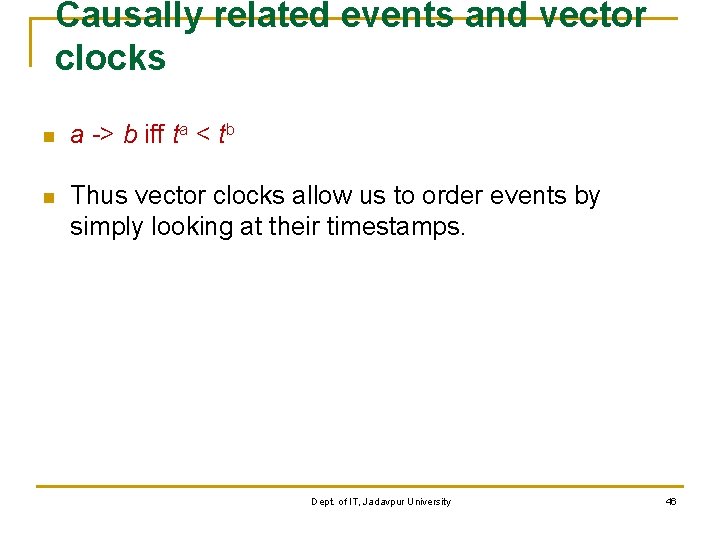

Causally related events and vector clocks n a -> b iff ta < tb n Thus vector clocks allow us to order events by simply looking at their timestamps. Dept. of IT, Jadavpur University 46

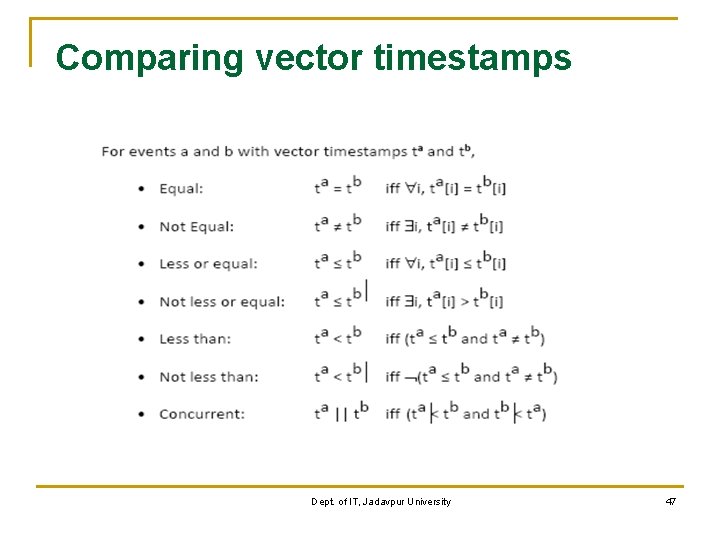

Comparing vector timestamps Dept. of IT, Jadavpur University 47

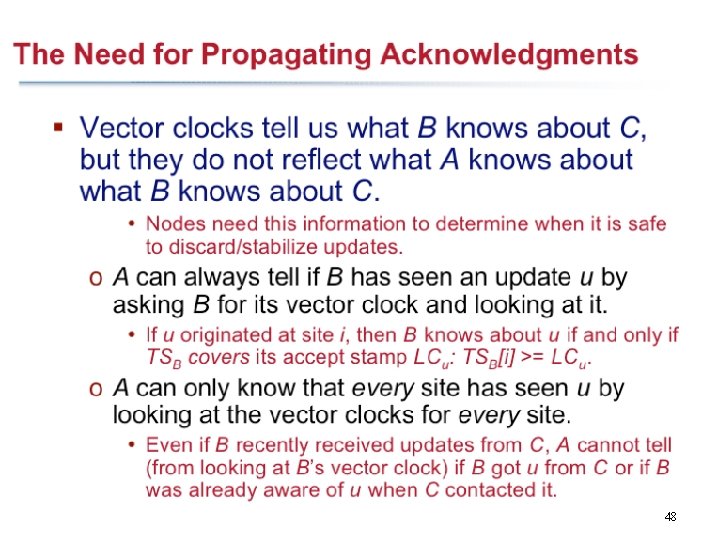

48

49

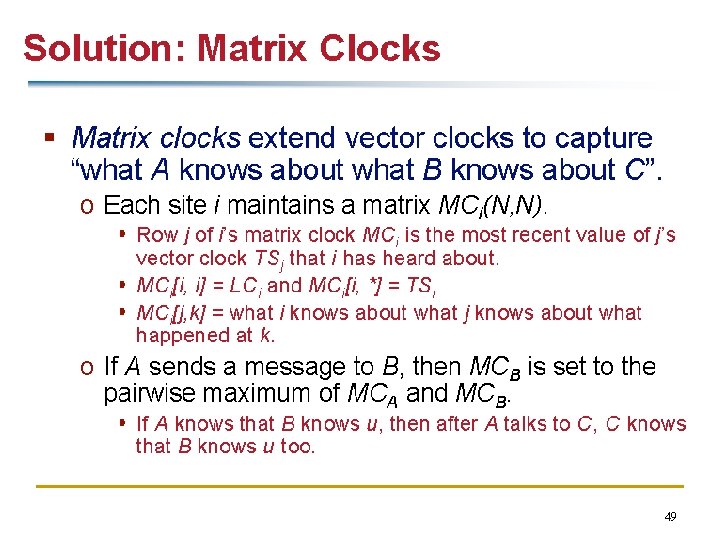

- Slides: 49