Climate Emergency Research Presentation to Climate Emergency Commission

- Slides: 5

Climate Emergency Research Presentation to Climate Emergency Commission, 26 th February 2020

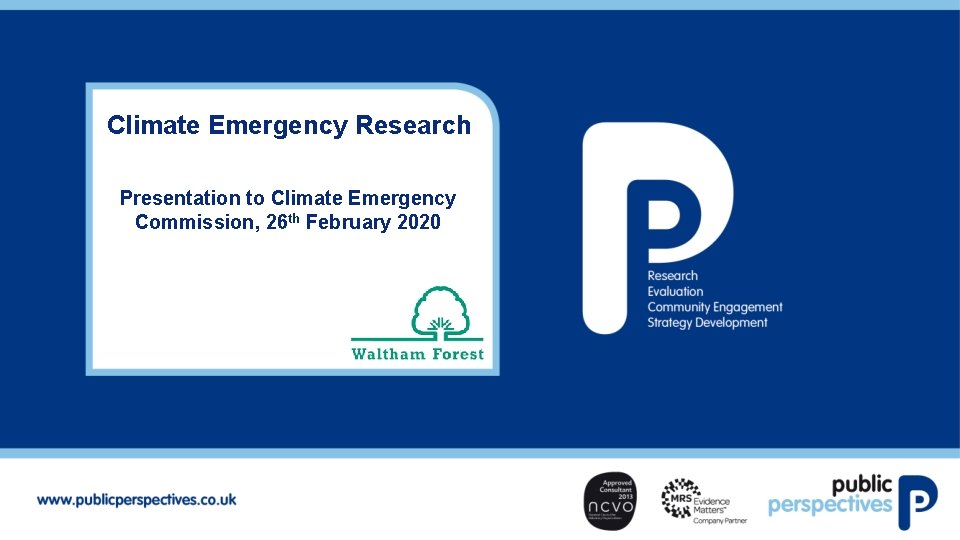

Key details Research with residents and interested parties to inform Waltham Forest’s Climate Emergency Commission and the council’s subsequent climate emergency strategy and action plan Research took place over October to December 2019 Mix of respondents achieved, albeit with a bias towards women, White British residents, those from higher socioeconomic groups and people living in the central area of Waltham Forest On-line survey, using established question sets, with 3090 respondents Sub-group analysis helps identify differences between different groups and make the results more representative 4 focus groups, one in each neighbourhood area, involving a demographic mix of 45 residents, including those concerned and not concerned about the climate emergency

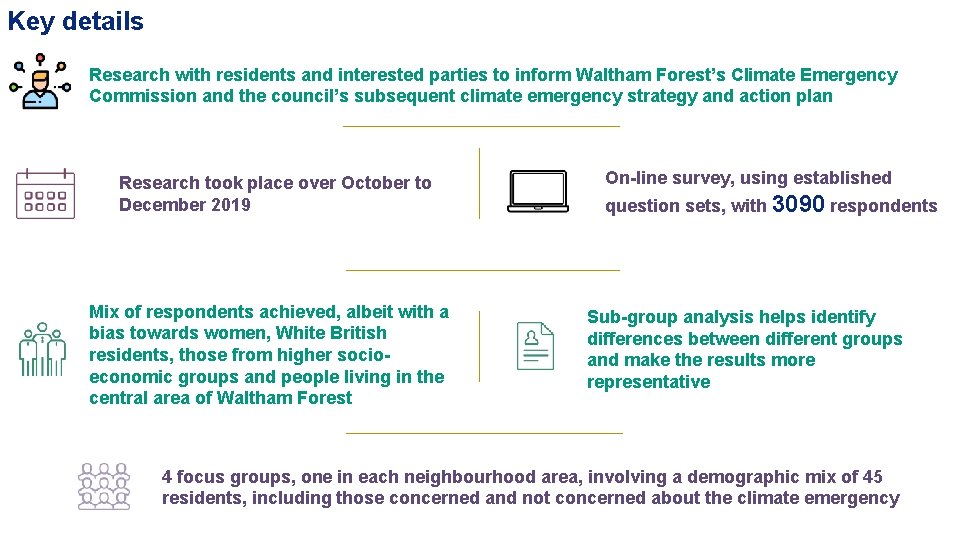

Key findings: Perceptions about the climate emergency and local action 9 in 10 concerned about the climate emergency, including 71% that are very concerned. 85% believe that climate change is already having an impact in the UK, and 7 in 10 think climate change is currently affecting their local area to at least some extent. The Climate Emergency Commission is generally seen as a positive initiative (67% agree), albeit with some scepticism. Residents want to see transparency, and positive and urgent action by the council and its partners in response to the Commission’s recommendations, while avoiding any tokenism or lip service (75% agree the council developing a new strategy is positive and 88% agree the council should set an example by adopting challenging targets and innovative approaches). Residents in the North of the borough, people aged over 55, disabled people, residents from lower-socio economic groups and men tend to be less concerned, less supportive of local and individual action, and more likely to indicate they could be affected by action to tackle the climate emergency, such as measures to reduce car use. Residents want the council to take significant and quick action, lead by example through its own buildings, services and resources, with progress monitored, impact measured and the council held to account, working collaboratively with local people through on-going community engagement, which would also help shape local policies and actions over time. Strong appetite for leadership by the council and for action at a local level, based around neighbourhood and community. Residents said this could help inspire and galvanise local people and potentially other local areas and councils. Planting more trees (90%), supporting recycling (84%), helping nature to thrive (84%), increasing the energy efficiency of homes (83%) and reducing single use plastics (81%) are the top five priorities residents want the council to take action on, alongside other actions to support individual behaviour change such as developing stronger planning policies (80%), reducing car journeys and improving public transport (74%), providing information and support to change behaviour (70%), providing charging points for vehicles (64%) and supporting less use of energy through information and smart metering (61%). Similarly, some residents said that tackling the climate emergency should be a priority for the council, but not delivered in isolation and instead a core part of everything it does to improve quality of life.

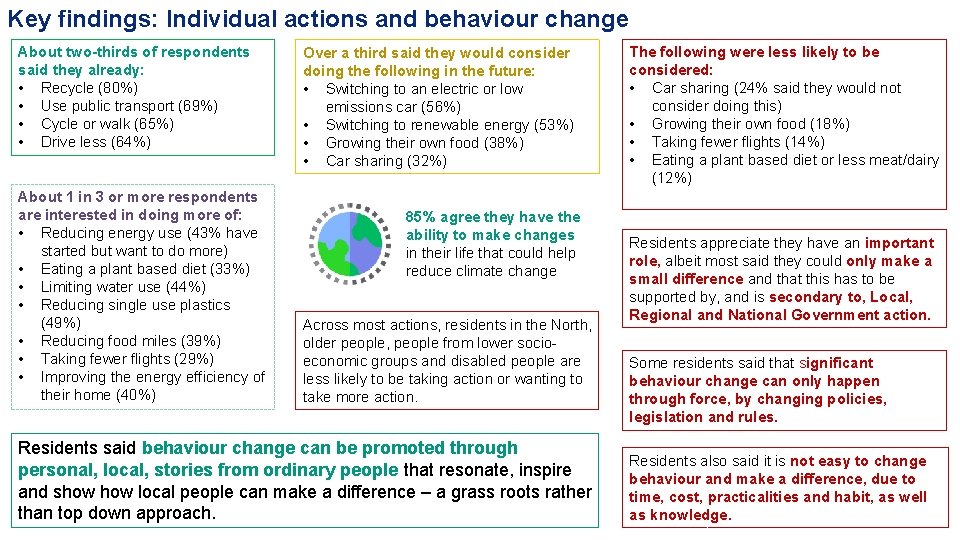

Key findings: Individual actions and behaviour change About two-thirds of respondents said they already: • Recycle (80%) • Use public transport (69%) • Cycle or walk (65%) • Drive less (64%) About 1 in 3 or more respondents are interested in doing more of: • Reducing energy use (43% have started but want to do more) • Eating a plant based diet (33%) • Limiting water use (44%) • Reducing single use plastics (49%) • Reducing food miles (39%) • Taking fewer flights (29%) • Improving the energy efficiency of their home (40%) Over a third said they would consider doing the following in the future: • Switching to an electric or low emissions car (56%) • Switching to renewable energy (53%) • Growing their own food (38%) • Car sharing (32%) 85% agree they have the ability to make changes in their life that could help reduce climate change Across most actions, residents in the North, older people, people from lower socioeconomic groups and disabled people are less likely to be taking action or wanting to take more action. Residents said behaviour change can be promoted through personal, local, stories from ordinary people that resonate, inspire and show local people can make a difference – a grass roots rather than top down approach. The following were less likely to be considered: • Car sharing (24% said they would not consider doing this) • Growing their own food (18%) • Taking fewer flights (14%) • Eating a plant based diet or less meat/dairy (12%) Residents appreciate they have an important role, albeit most said they could only make a small difference and that this has to be supported by, and is secondary to, Local, Regional and National Government action. Some residents said that significant behaviour change can only happen through force, by changing policies, legislation and rules. Residents also said it is not easy to change behaviour and make a difference, due to time, cost, practicalities and habit, as well as knowledge.

Residents said behaviour change can be encouraged by rooting it in local, neighbourhood, community action, which improves the local area and local lives, and therefore resonates and becomes relatable, meaningful and tangible and galvanises local people to take action – “It starts with love your neighbourhood” I try to make my actions ‘ultra-local’. You feel like you can’t change things globally, but you can make a difference locally. So it is not just about doing something about climate change, but also about community, your local area and your local neighbourhood. In the end it is more about that really, and I think people can sign-up to that because they can see the benefits. There’s lots of things that are good for the area and local people, that residents would do because it’s good for them not just for the environment. So I think all of this has to be promoted and communicated in the context of improving people’s lives and the local area, so it is meaningful to them and they can see the immediate benefits to their lives. In that way, people will change their behaviour and support change. It is difficult for the individual to feel like they can make a difference. I think they can make a difference, but it is small, so it helps if others around you are doing it so it becomes normal and it helps if the council are leading by example so you feel you’re part of a bigger effort and not doing things that are cancelled out by the activities of others. So in that way I think it is about community action, led and inspired by the council, to make the local area a better place to live.