Classical Statistical Mechanics Paramagnetism in the Canonical Ensemble

Classical Statistical Mechanics: Paramagnetism in the Canonical Ensemble

Paramagnetism • Paramagnetism occurs in substances where the individual atoms, ions or molecules possess a permanent magnetic dipole moment. • The permanent magnetic moment is due to the contributions from: 1. The Spin (intrinsic moments) of the electrons.

Paramagnetism • Paramagnetism occurs in substances where the individual atoms, ions or molecules possess a permanent magnetic dipole moment. • The permanent magnetic moment is due to the contributions from: 1. The Spin (intrinsic moments) of the electrons. 2. The Orbital motion of the electrons.

Paramagnetism • Paramagnetism occurs in substances where the individual atoms, ions or molecules possess a permanent magnetic dipole moment. • The permanent magnetic moment is due to the contributions from: 1. The Spin (intrinsic moments) of the electrons. 2. The Orbital motion of the electrons. 3. The Spin magnetic moment of the nucleus.

Some Paramagnetic Materials • Some Metals. • Atoms, & molecules with an odd number of electrons, such as free Na atoms, gaseous Nitric oxide (NO) etc. • Atoms or ions with a partly filled inner shell: Transition elements, rare earth & actinide elements. Mn 2+, Gd 3+, U 4+ etc. • A few compounds with an even number of electrons including molecular oxygen.

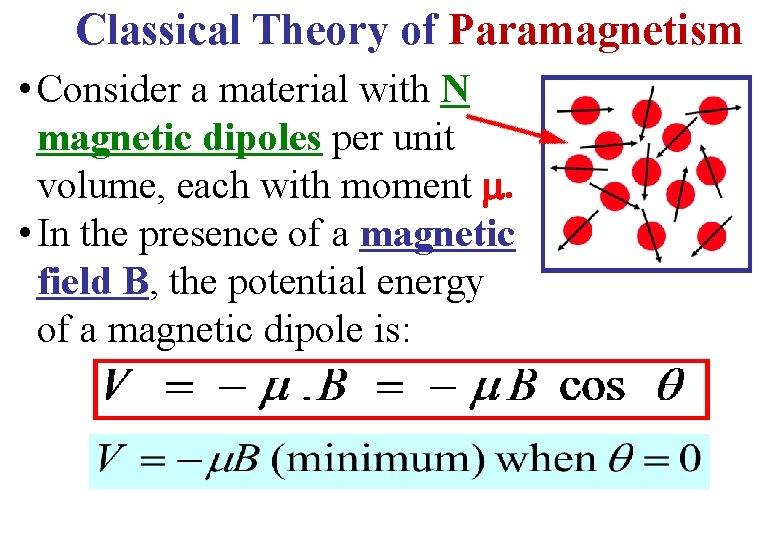

Classical Theory of Paramagnetism • Consider a material with N magnetic dipoles per unit volume, each with moment . • In the presence of a magnetic field B, the potential energy of a magnetic dipole is:

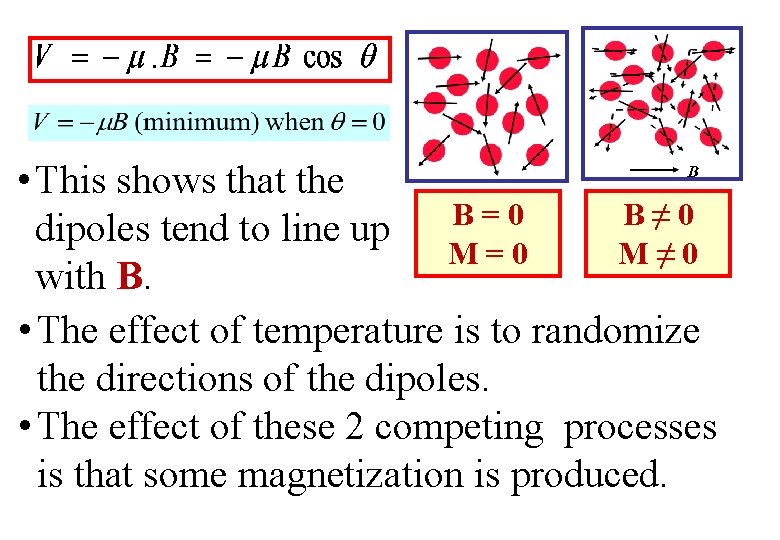

• This shows that the B = 0 B ≠ 0 dipoles tend to line up M=0 M≠ 0 with B. • The effect of temperature is to randomize the directions of the dipoles. • The effect of these 2 competing processes is that some magnetization is produced.

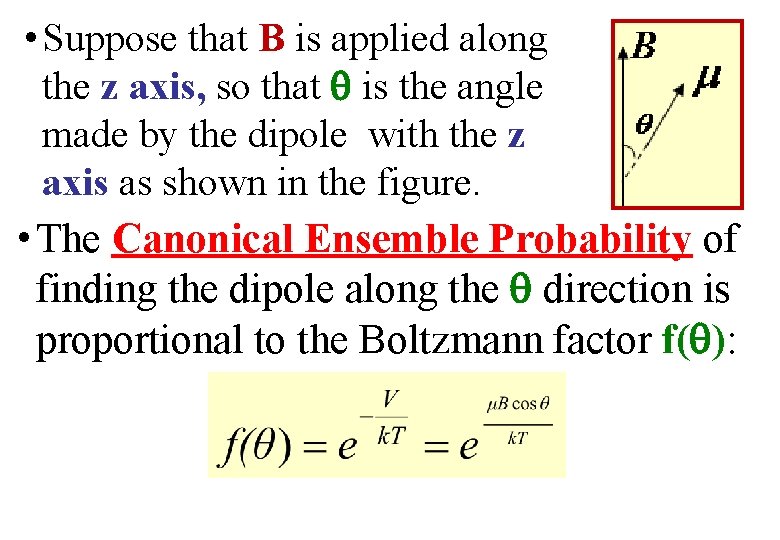

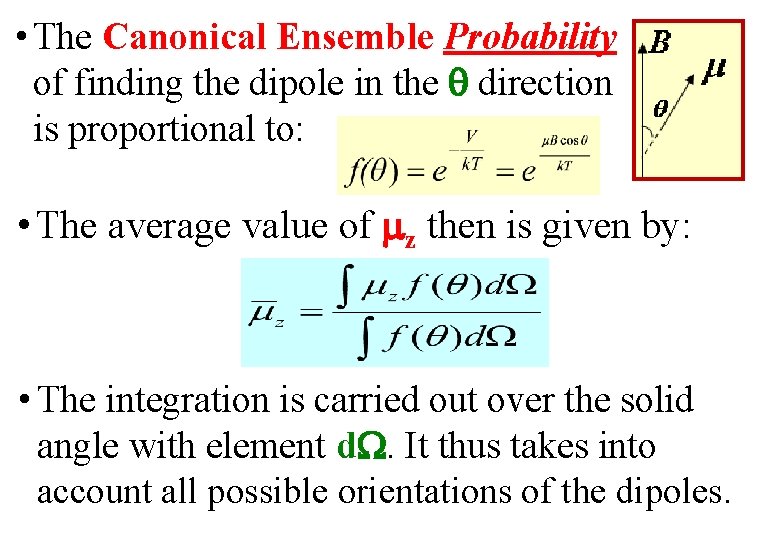

• Suppose that B is applied along the z axis, so that is the angle made by the dipole with the z axis as shown in the figure. • The Canonical Ensemble Probability of finding the dipole along the direction is proportional to the Boltzmann factor f( ):

• The Canonical Ensemble Probability of finding the dipole in the direction is proportional to: • The average value of z then is given by: • The integration is carried out over the solid angle with element d. It thus takes into account all possible orientations of the dipoles.

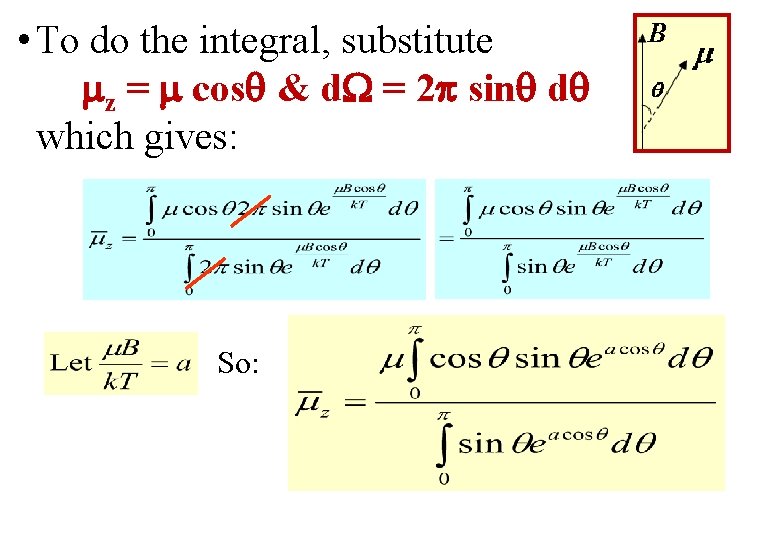

• To do the integral, substitute z = cos & d = 2 sin d which gives: So:

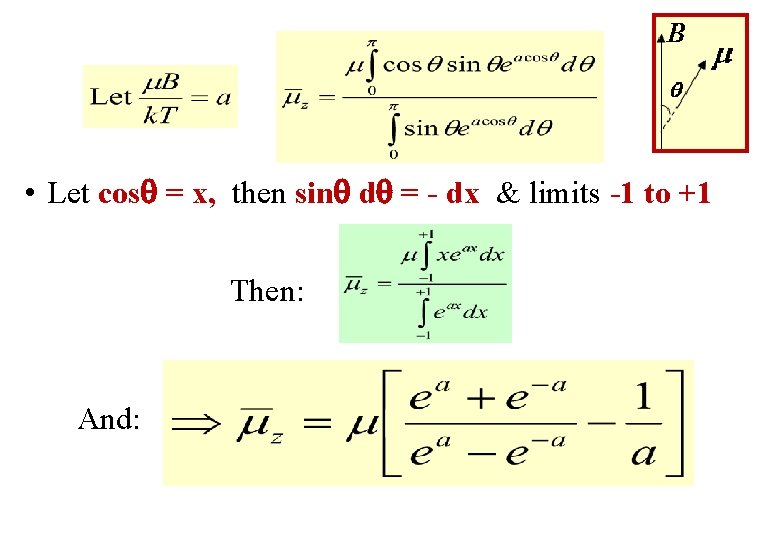

• Let cos = x, then sin d = - dx & limits -1 to +1 Then: And:

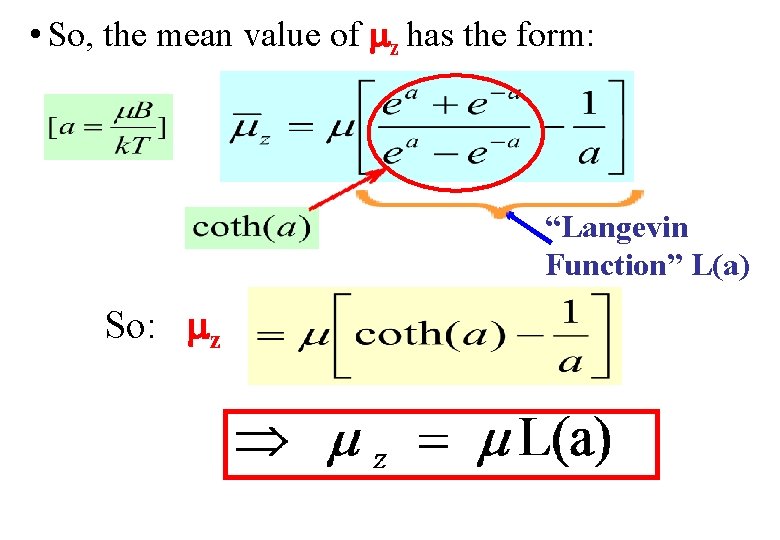

• So, the mean value of z has the form: “Langevin Function” L(a) So: z

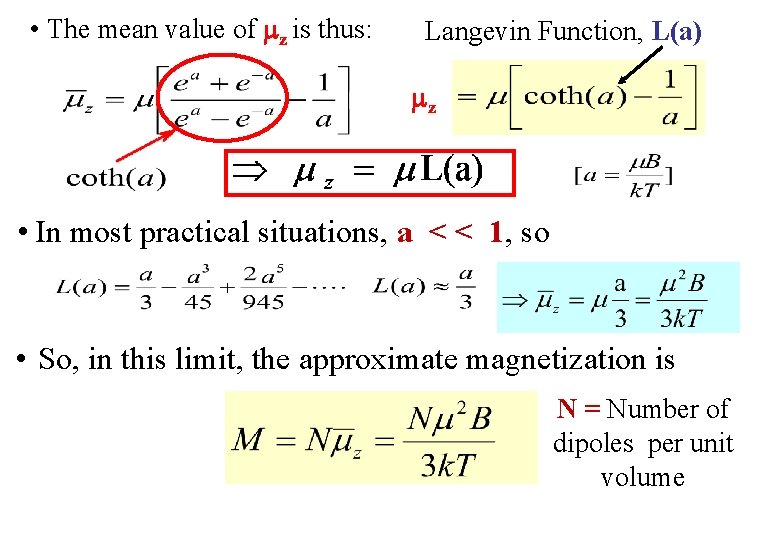

• The mean value of z is thus: Langevin Function, L(a) z • In most practical situations, a < < 1, so • So, in this limit, the approximate magnetization is N = Number of dipoles per unit volume

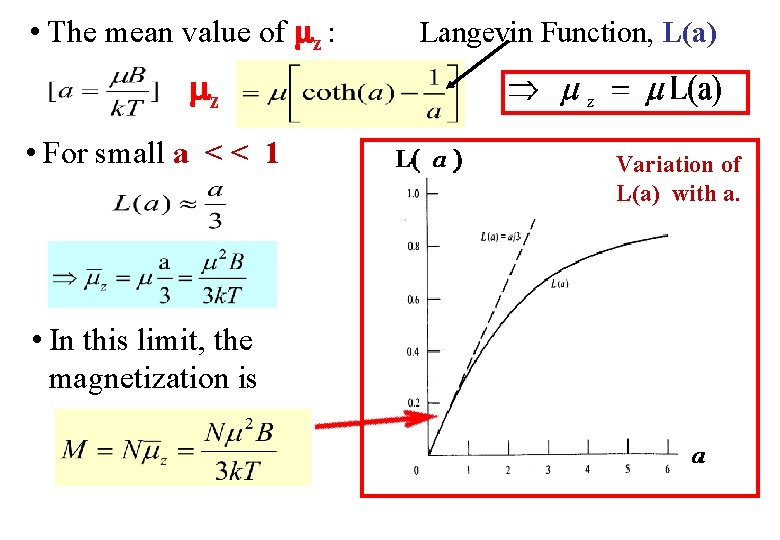

• The mean value of z : Langevin Function, L(a) z • For small a < < 1 • In this limit, the magnetization is Variation of L(a) with a.

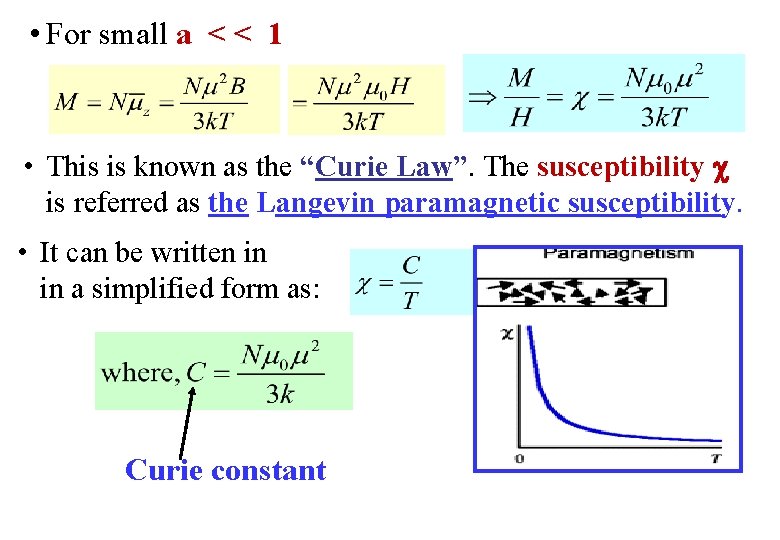

• For small a < < 1 • This is known as the “Curie Law”. The susceptibility is referred as the Langevin paramagnetic susceptibility. • It can be written in in a simplified form as: Curie constant

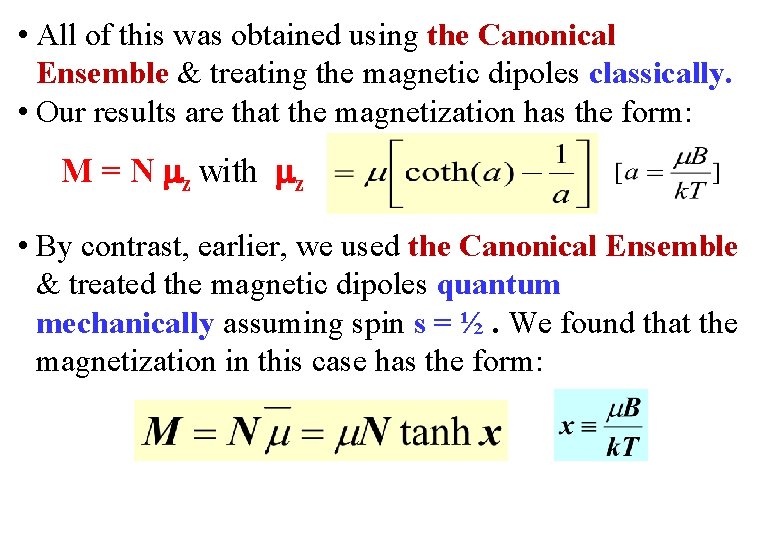

• All of this was obtained using the Canonical Ensemble & treating the magnetic dipoles classically. • Our results are that the magnetization has the form: l M = N z with z • By contrast, earlier, we used the Canonical Ensemble & treated the magnetic dipoles quantum mechanically assuming spin s = ½. We found that the magnetization in this case has the form:

• The magnetization M & its dependence on the dimensionless energy ratio a x are obviously not the same for the two cases. However, it is worth noting that the function M(x) displays similar qualitative behavior as a function of x in the two cases.

• The magnetization M & its dependence on the dimensionless energy ratio a x are obviously not the same for the two cases. However, it is worth noting that the function M(x) displays similar qualitative behavior as a function of x in the two cases. • Specifically, in the small x limit, (low B, high T), in both cases, the magnetization simplifies to M = B where is called the magnetic susceptibility.

• The magnetization M & its dependence on the dimensionless energy ratio a x are obviously not the same for the two cases. However, it is worth noting that the function M(x) displays similar qualitative behavior as a function of x in the two cases. • Specifically, in the small x limit, (low B, high T), in both cases, the magnetization simplifies to M = B where is called the magnetic susceptibility. • It can be written in the “Curie Law” form Further, C has the same form in both models!!

• So, both the Classical Statistics model & the Quantum (spin s = ½) model give the SAME magnetization M & in the small x limit, (low a x B, high T). That is, both cases give M = B. • Also, the susceptibility has the Curie “Law” form:

• So, both the Classical Statistics model & the Quantum (spin s = ½) model give the SAME magnetization M & in the small x limit, (low a x B, high T). That is, both cases give M = B. • Also, the susceptibility has the Curie “Law” form: • Further, both models give the same qualitative result for the magnetization M in the large x limit, (high B, low T). • That is, both cases give M Constant as x . In other words, for large enough x, in both models the magnetization M saturates to a constant value called the Saturation Magnetization.

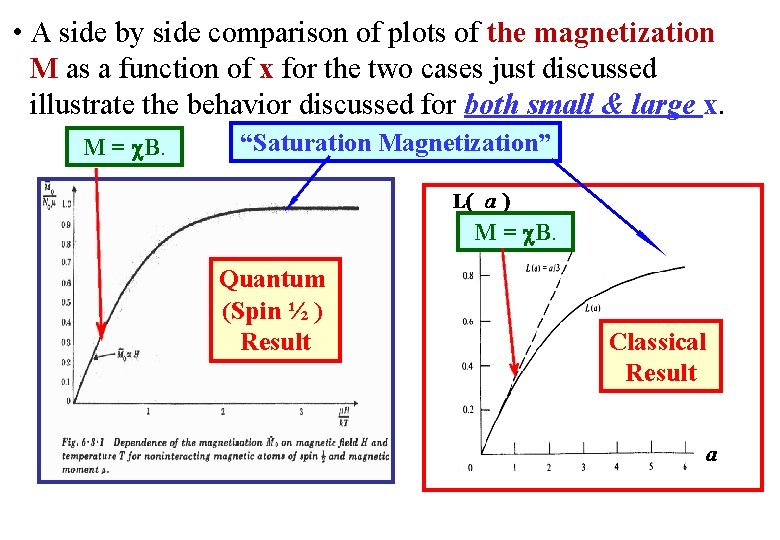

• A side by side comparison of plots of the magnetization M as a function of x for the two cases just discussed illustrate the behavior discussed for both small & large x. M = B. “Saturation Magnetization” M = B. Quantum (Spin ½ ) Result Classical Result

- Slides: 22