Chronic Otitis Media Mesotympanitis Epitympanitis Otogenous intracranial complications

- Slides: 53

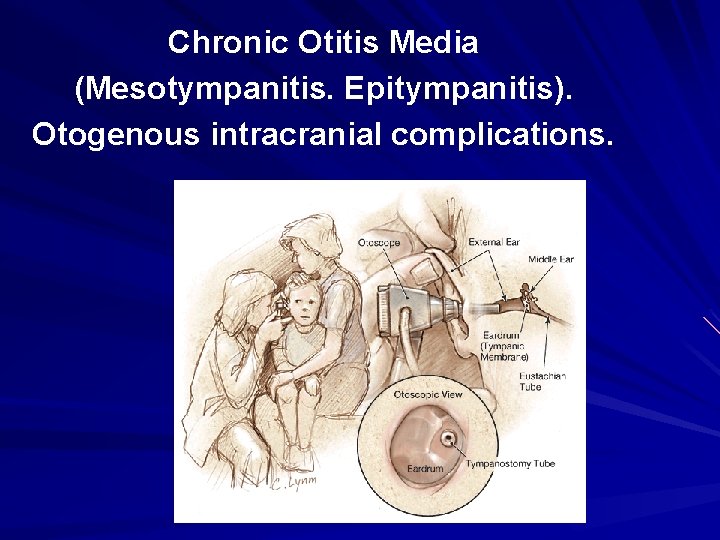

Chronic Otitis Media (Mesotympanitis. Epitympanitis). Otogenous intracranial complications.

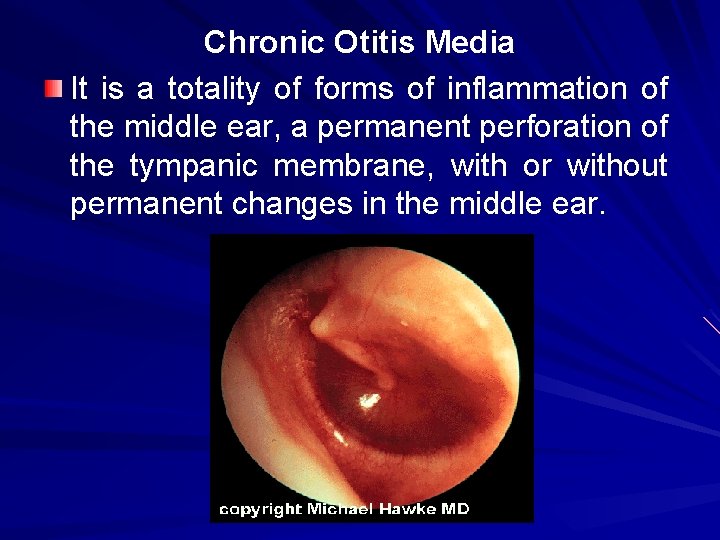

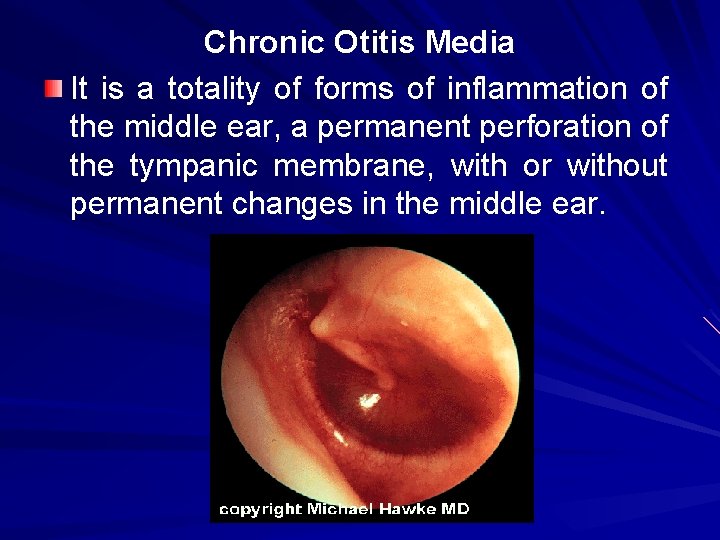

Chronic Otitis Media It is a totality of forms of inflammation of the middle ear, a permanent perforation of the tympanic membrane, with or without permanent changes in the middle ear.

Predisposing factors for COM: Anatomical peculiarities of the middle ear (sclerotic type of the mastoid) Necrotic forms of APOM under infectious diseases (measles, scarlet fever, diphtheria) Improper and insufficient treatment of APОM and mastoiditis. Decrease of the organism reactivity. Allergic lesion of mucous membrane of nasal cavity and Eustachian tube. Ventilation and drainage function disorder.

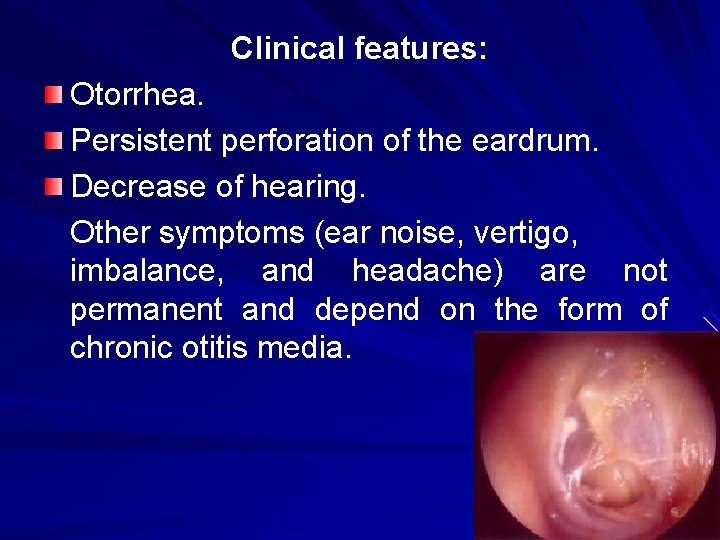

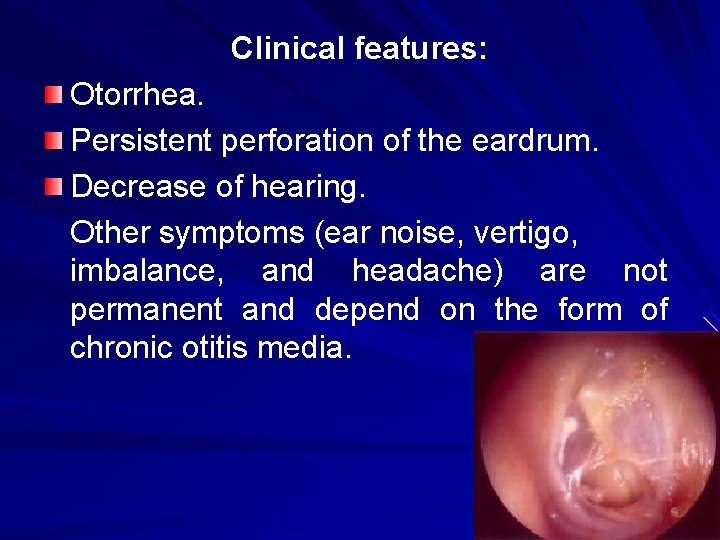

Clinical features: Otorrhea. Persistent perforation of the eardrum. Decrease of hearing. Other symptoms (ear noise, vertigo, imbalance, and headache) are not permanent and depend on the form of chronic otitis media.

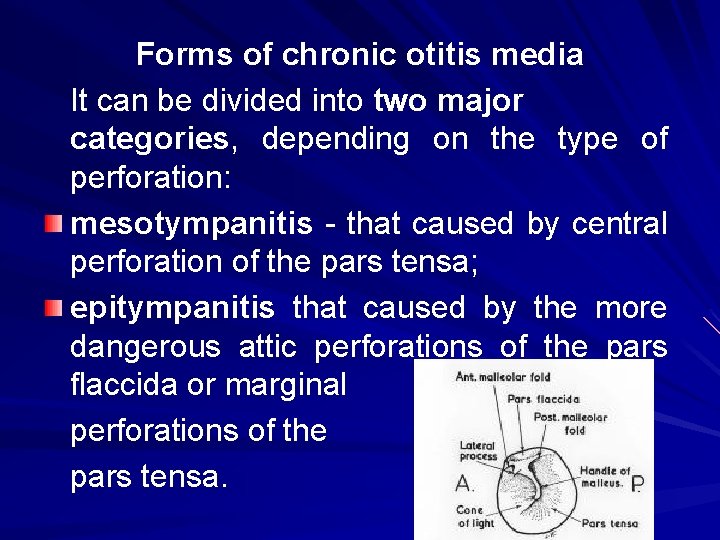

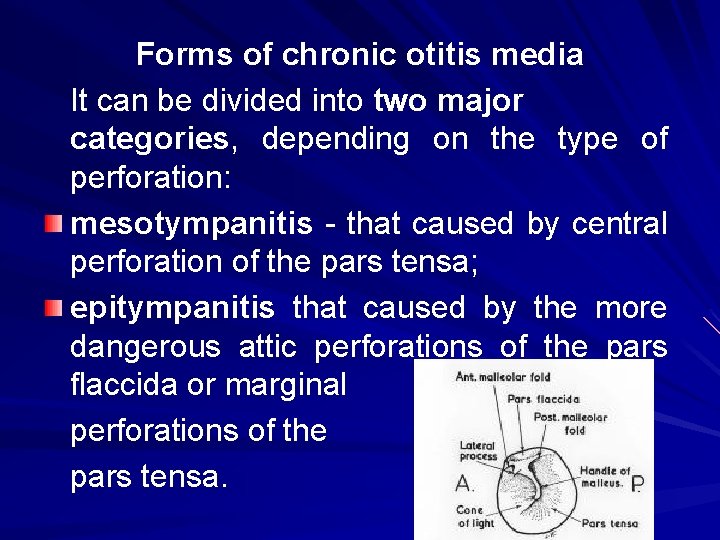

Forms of chronic otitis media It can be divided into two major categories, depending on the type of perforation: mesotympanitis - that caused by central perforation of the pars tensa; epitympanitis that caused by the more dangerous attic perforations of the pars flaccida or marginal perforations of the pars tensa.

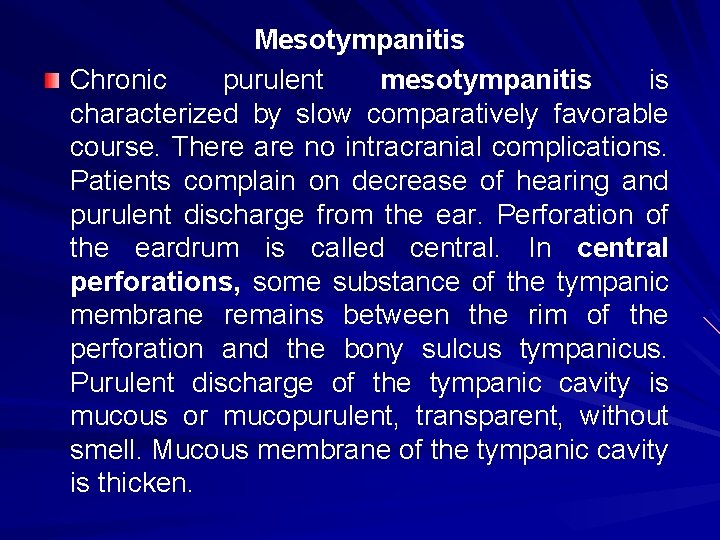

Mesotympanitis Chronic purulent mesotympanitis is characterized by slow comparatively favorable course. There are no intracranial complications. Patients complain on decrease of hearing and purulent discharge from the ear. Perforation of the eardrum is called central. In central perforations, some substance of the tympanic membrane remains between the rim of the perforation and the bony sulcus tympanicus. Purulent discharge of the tympanic cavity is mucous or mucopurulent, transparent, without smell. Mucous membrane of the tympanic cavity is thicken.

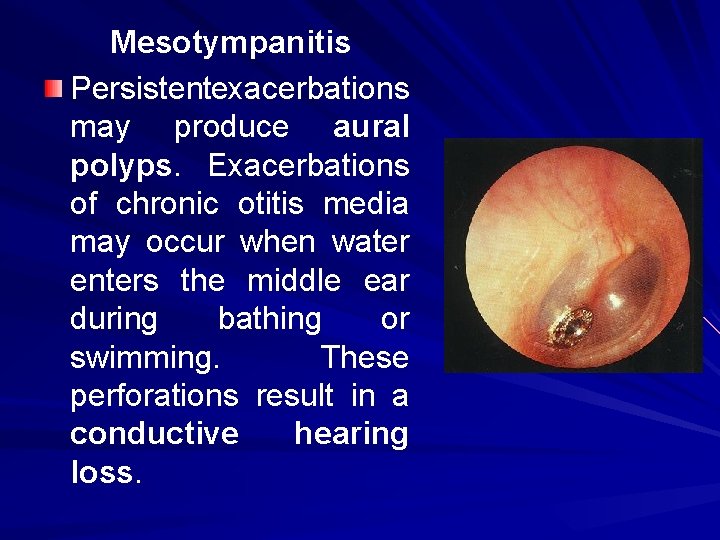

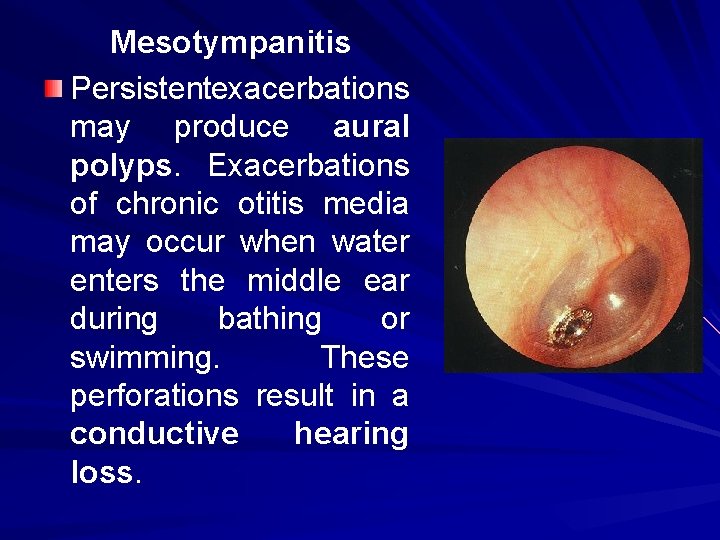

Mesotympanitis Persistentexacerbations may produce aural polyps. Exacerbations of chronic otitis media may occur when water enters the middle ear during bathing or swimming. These perforations result in a conductive hearing loss.

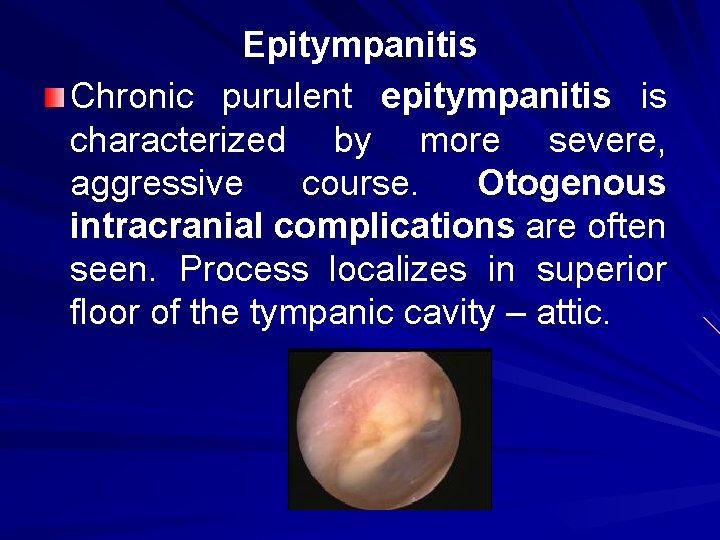

Epitympanitis Chronic purulent epitympanitis is characterized by more severe, aggressive course. Otogenous intracranial complications are often seen. Process localizes in superior floor of the tympanic cavity – attic.

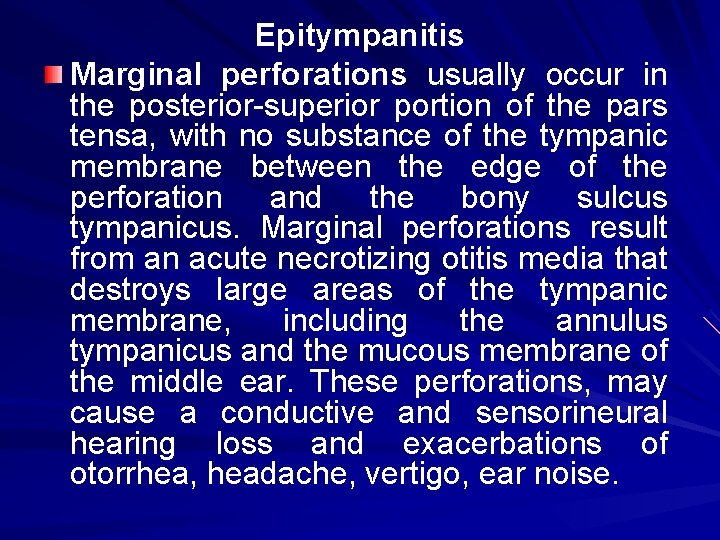

Epitympanitis Marginal perforations usually occur in the posterior-superior portion of the pars tensa, with no substance of the tympanic membrane between the edge of the perforation and the bony sulcus tympanicus. Marginal perforations result from an acute necrotizing otitis media that destroys large areas of the tympanic membrane, including the annulus tympanicus and the mucous membrane of the middle ear. These perforations, may cause a conductive and sensorineural hearing loss and exacerbations of otorrhea, headache, vertigo, ear noise.

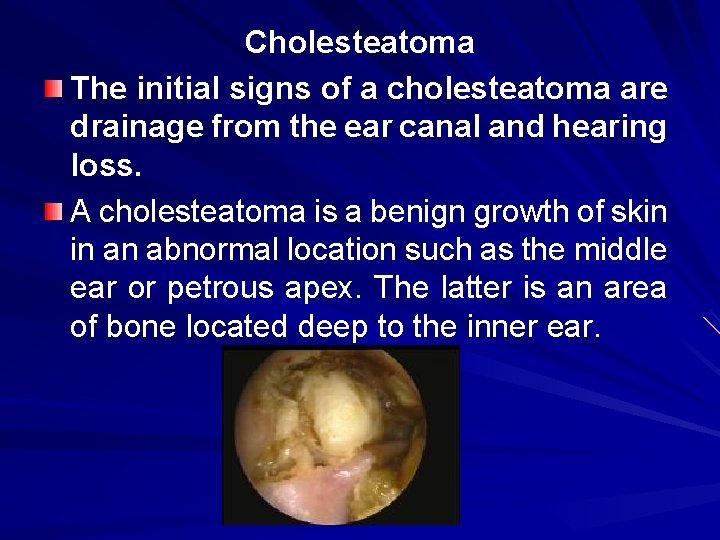

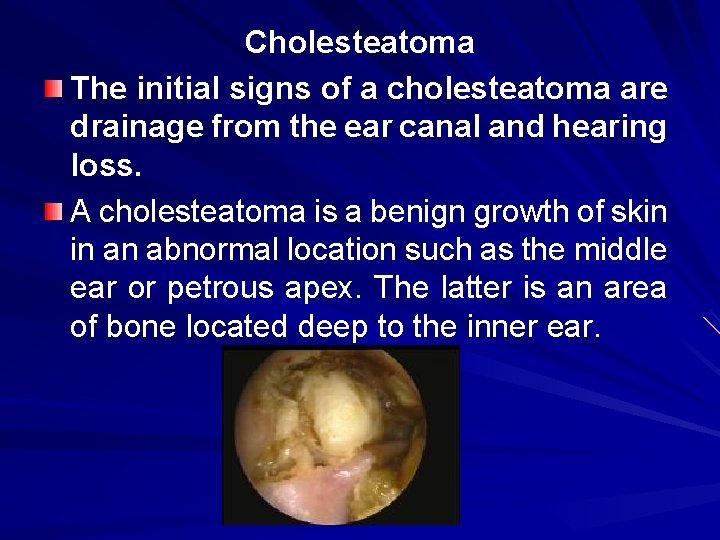

Cholesteatoma The initial signs of a cholesteatoma are drainage from the ear canal and hearing loss. A cholesteatoma is a benign growth of skin in an abnormal location such as the middle ear or petrous apex. The latter is an area of bone located deep to the inner ear.

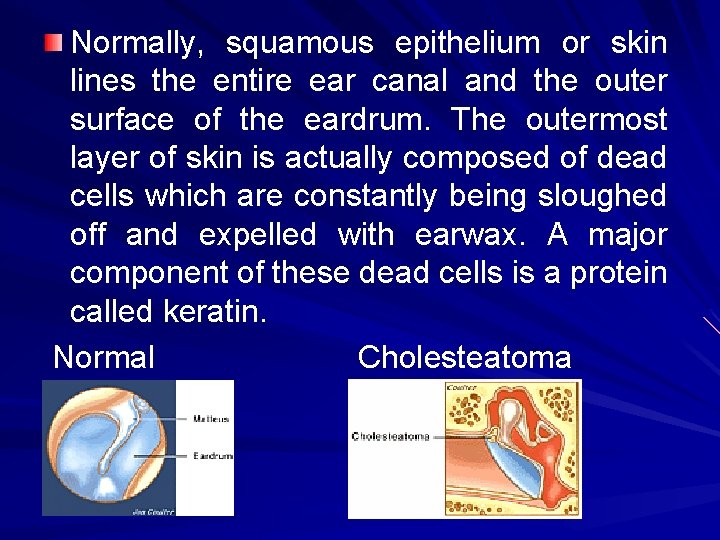

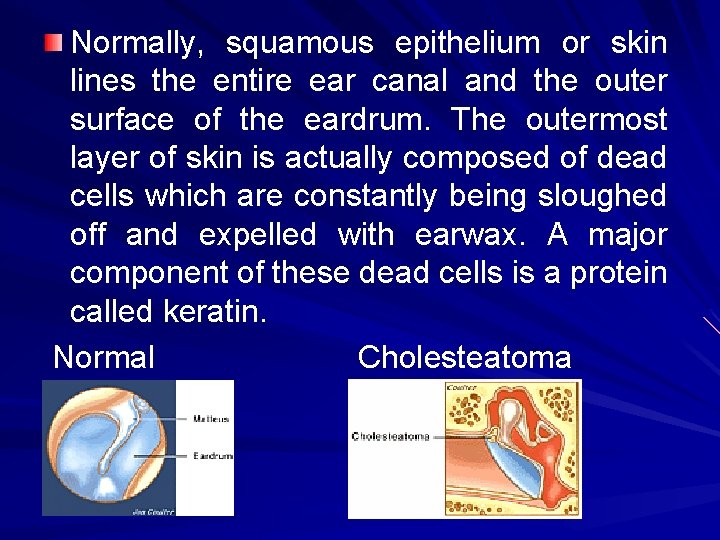

Normally, squamous epithelium or skin lines the entire ear canal and the outer surface of the eardrum. The outermost layer of skin is actually composed of dead cells which are constantly being sloughed off and expelled with earwax. A major component of these dead cells is a protein called keratin. Normal Cholesteatoma

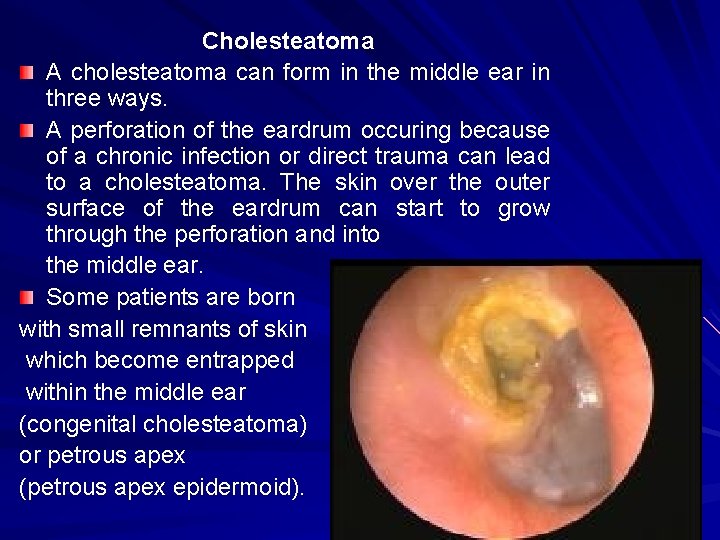

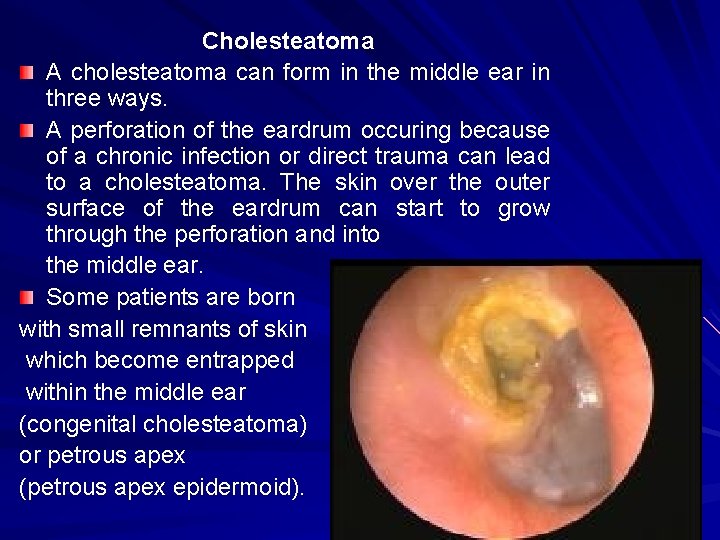

Cholesteatoma A cholesteatoma can form in the middle ear in three ways. A perforation of the eardrum occuring because of a chronic infection or direct trauma can lead to a cholesteatoma. The skin over the outer surface of the eardrum can start to grow through the perforation and into the middle ear. Some patients are born with small remnants of skin which become entrapped within the middle ear (congenital cholesteatoma) or petrous apex (petrous apex epidermoid).

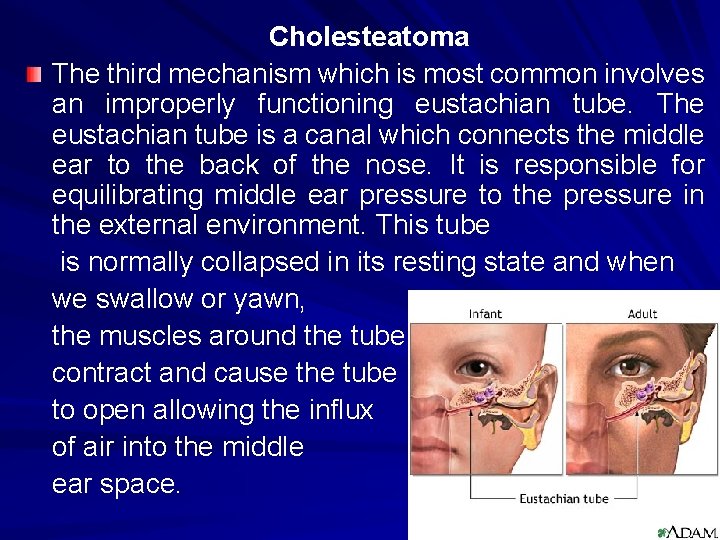

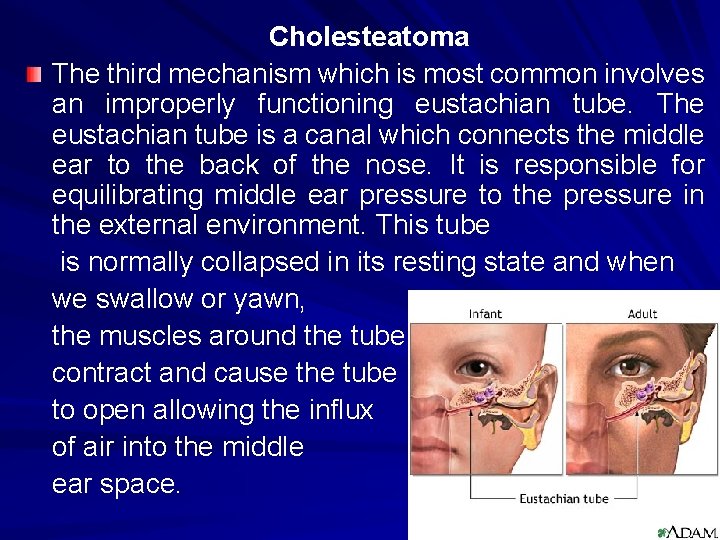

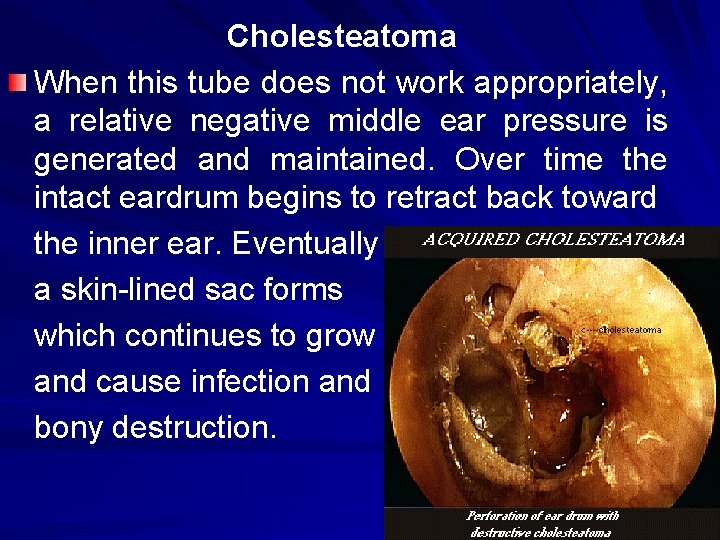

Cholesteatoma The third mechanism which is most common involves an improperly functioning eustachian tube. The eustachian tube is a canal which connects the middle ear to the back of the nose. It is responsible for equilibrating middle ear pressure to the pressure in the external environment. This tube is normally collapsed in its resting state and when we swallow or yawn, the muscles around the tube contract and cause the tube to open allowing the influx of air into the middle ear space.

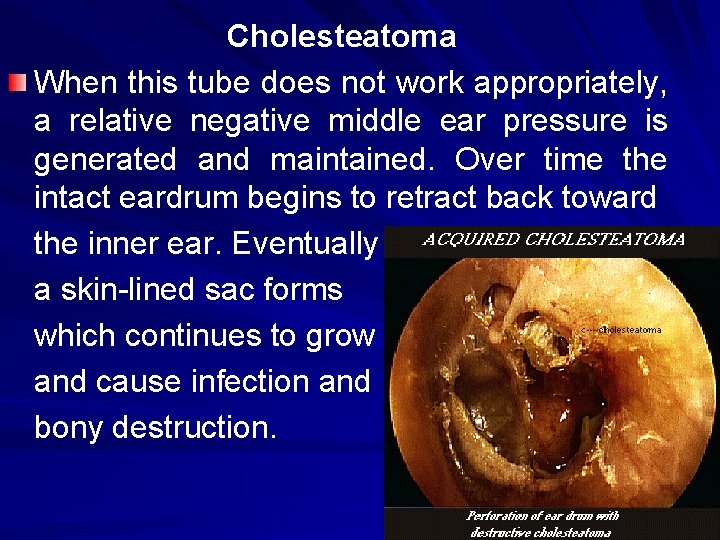

Cholesteatoma When this tube does not work appropriately, a relative negative middle ear pressure is generated and maintained. Over time the intact eardrum begins to retract back toward the inner ear. Eventually a skin-lined sac forms which continues to grow and cause infection and bony destruction.

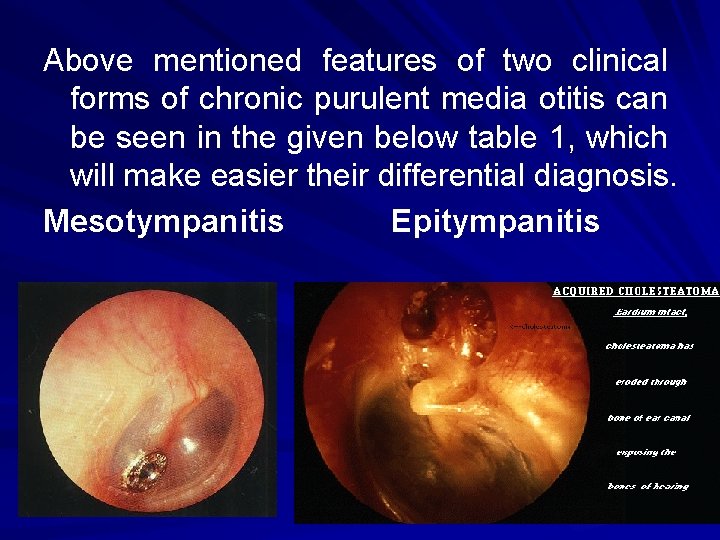

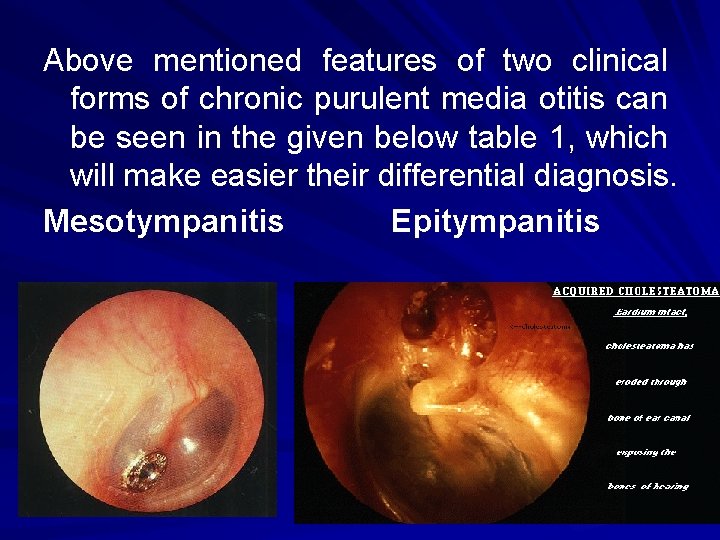

Above mentioned features of two clinical forms of chronic purulent media otitis can be seen in the given below table 1, which will make easier their differential diagnosis. Mesotympanitis Epitympanitis

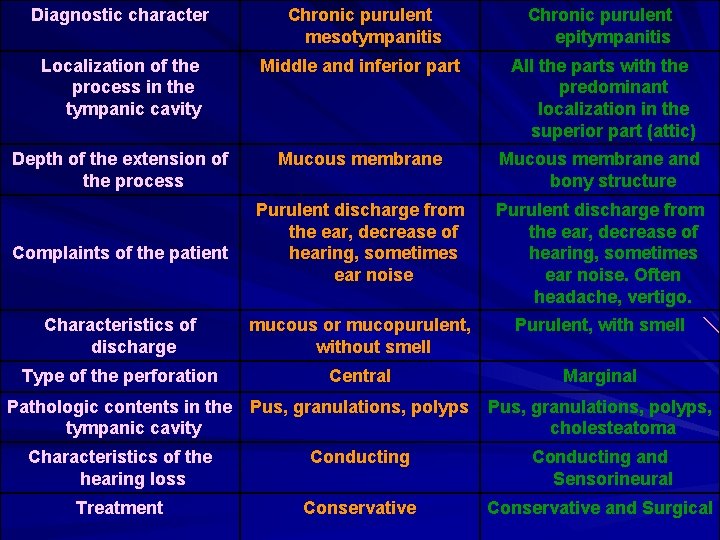

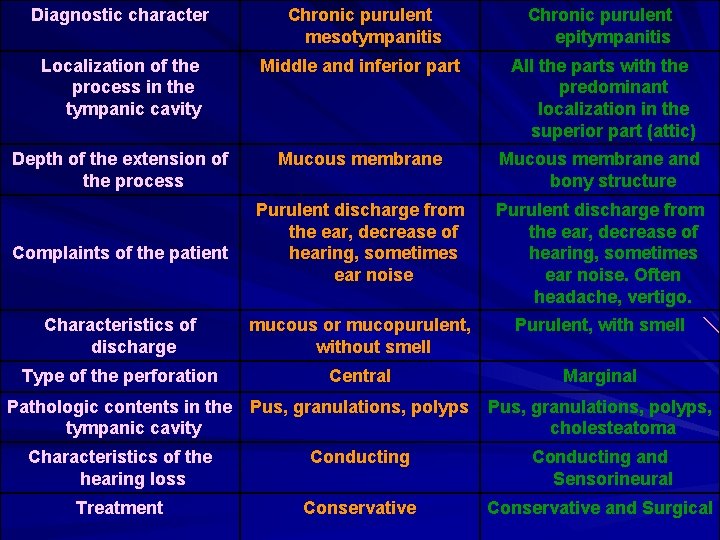

Diagnostic character Chronic purulent mesotympanitis Chronic purulent epitympanitis Localization of the process in the tympanic cavity Middle and inferior part All the parts with the predominant localization in the superior part (attic) Depth of the extension of the process Mucous membrane and bony structure Purulent discharge from the ear, decrease of hearing, sometimes ear noise. Often headache, vertigo. Characteristics of discharge mucous or mucopurulent, without smell Purulent, with smell Type of the perforation Central Marginal Pathologic contents in the tympanic cavity Pus, granulations, polyps, cholesteatoma Characteristics of the hearing loss Conducting and Sensorineural Treatment Conservative and Surgical Complaints of the patient

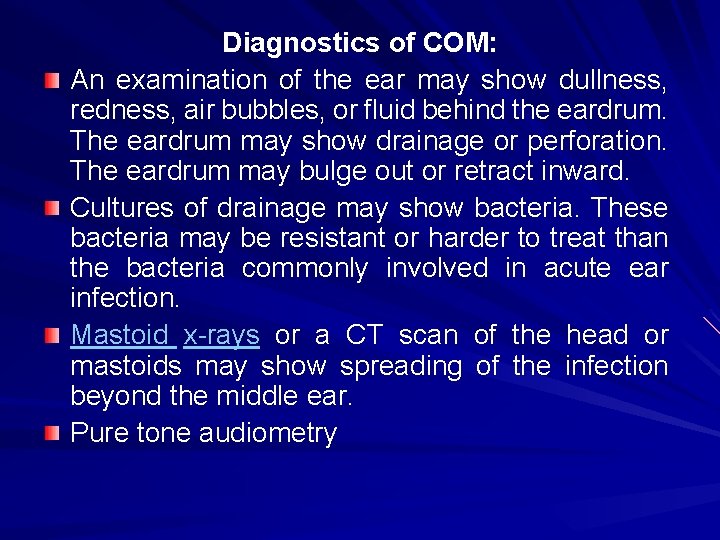

Diagnostics of COM: An examination of the ear may show dullness, redness, air bubbles, or fluid behind the eardrum. The eardrum may show drainage or perforation. The eardrum may bulge out or retract inward. Cultures of drainage may show bacteria. These bacteria may be resistant or harder to treat than the bacteria commonly involved in acute ear infection. Mastoid x-rays or a CT scan of the head or mastoids may show spreading of the infection beyond the middle ear. Pure tone audiometry

Treatment: We apply complex treatment. Conservative: (general and local) Surgical

General: Severe exacerbations require systemic therapy with a broad-spectrum antibiotic. Subsequent treatment should be guided by cultures and sensitivities of the isolated microorganisms and by the patient's clinical response. Under epitympanitis lavage of the spirit antiseptics and antibiotics is made. Ototoxic antibiotics (aminoglycoside) must not be prescribed. Vasoconstrictive nasal drops, hyposensitization drugs, antiinflammatory drugs. Physiotherapeutic procedures are used only under mesotympanitis. Note: Surgical removal of the adenoids may be necessary to allow the eustachian tube to open. Keep the ears clean and dry to prevent reinfection.

Local: 1 st stage. For exacerbations of both types of chronic otitis media, the ear canal and middle ear are thoroughly cleaned with suction and dry cotton wipes; 2 nd stage. Local action on the mucous membrane of the middle ear is made. A solution of 2% acetic acid with hydrocortisone 1% is instilled into the ear, 5 to 10 drops three times a day for 7 to 10 days. 3 rd stage. Its goal to close perforation of the eardrum (mesotympanitis).

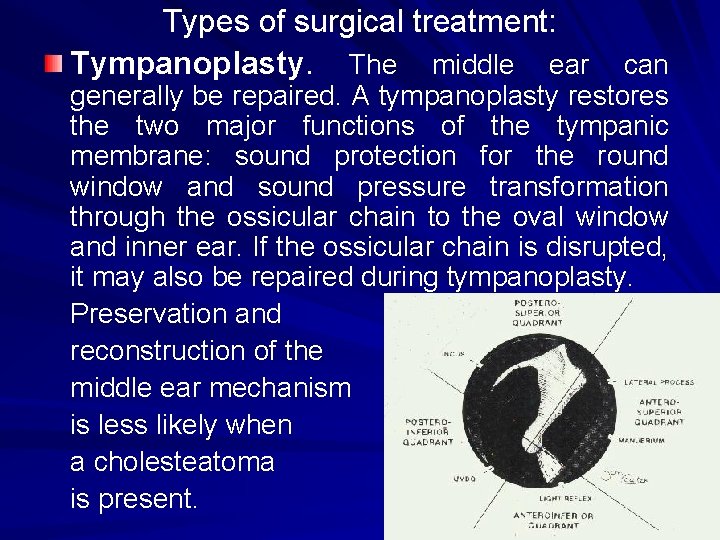

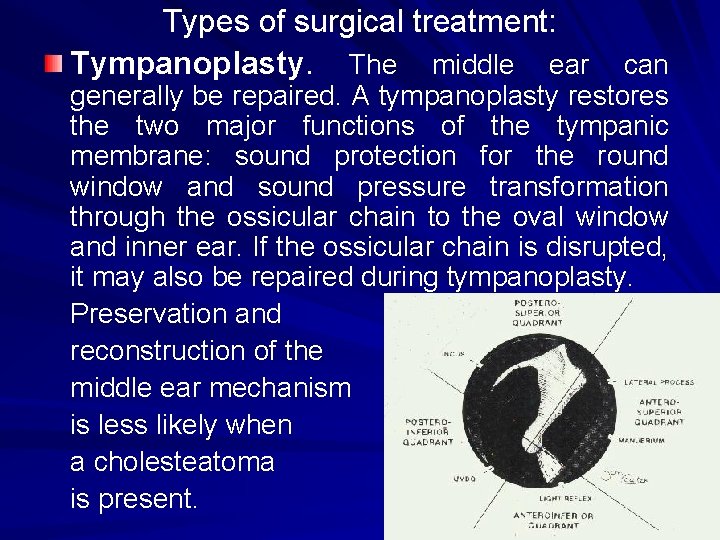

Types of surgical treatment: Tympanoplasty. The middle ear can generally be repaired. A tympanoplasty restores the two major functions of the tympanic membrane: sound protection for the round window and sound pressure transformation through the ossicular chain to the oval window and inner ear. If the ossicular chain is disrupted, it may also be repaired during tympanoplasty. Preservation and reconstruction of the middle ear mechanism is less likely when a cholesteatoma is present.

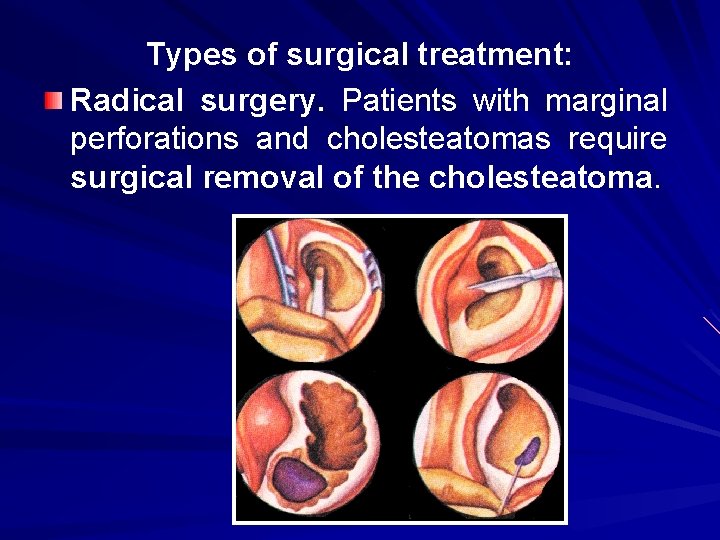

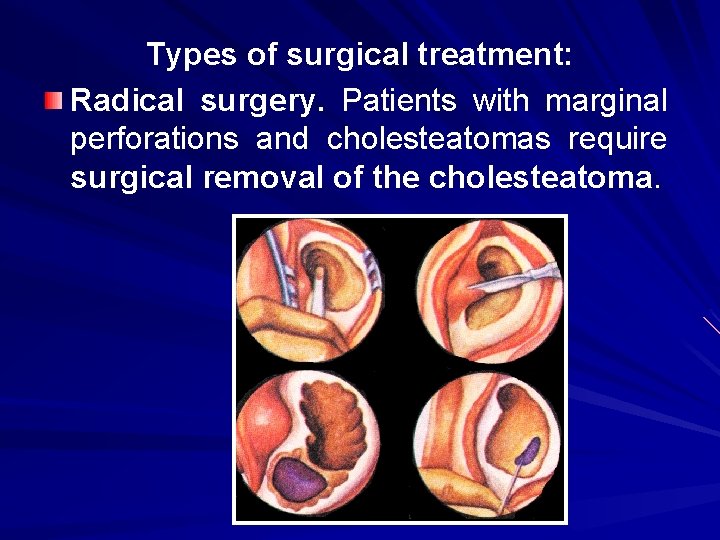

Types of surgical treatment: Radical surgery. Patients with marginal perforations and cholesteatomas require surgical removal of the cholesteatoma.

Complications of CPOM (epitympanitis): deafness in one ear vertigo persistent ear drainage erosion into the facial nerve (causing facial paralysis) spread of the cyst into the brain labyrinthitis meningitis brain abscess

Otogenous intracranial complications. Antibiotics have produced an overall decline in the frequency of complications of otitis media relative to the preantibiotic era. However, severe complications still occur and may be associated with high mortality. The complications of otitis media include the following: Meningitis Intracranial abscess Sigmoid sinus thrombosis

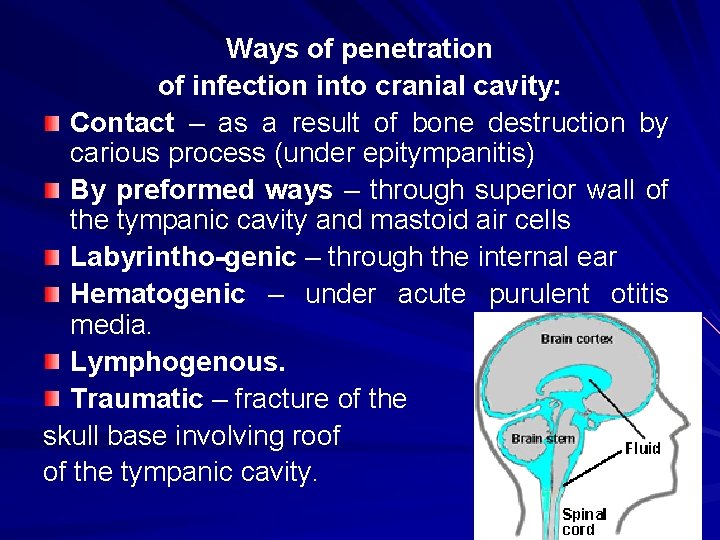

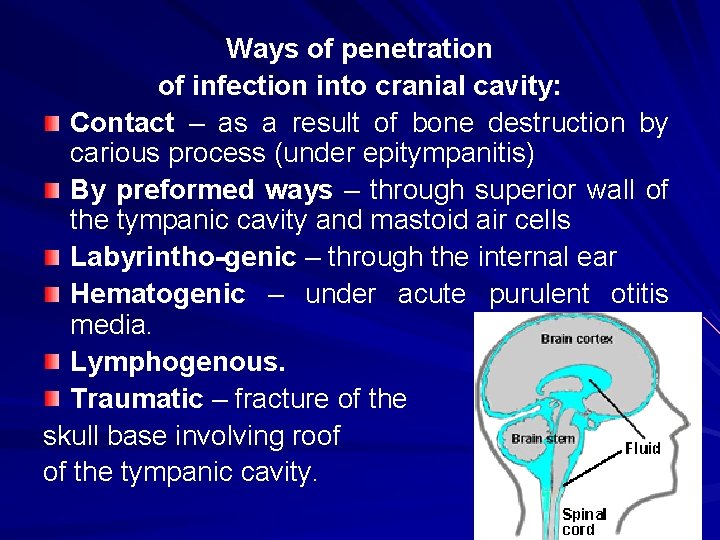

Ways of penetration of infection into cranial cavity: Contact – as a result of bone destruction by carious process (under epitympanitis) By preformed ways – through superior wall of the tympanic cavity and mastoid air cells Labyrintho-genic – through the internal ear Hematogenic – under acute purulent otitis media. Lymphogenous. Traumatic – fracture of the skull base involving roof of the tympanic cavity.

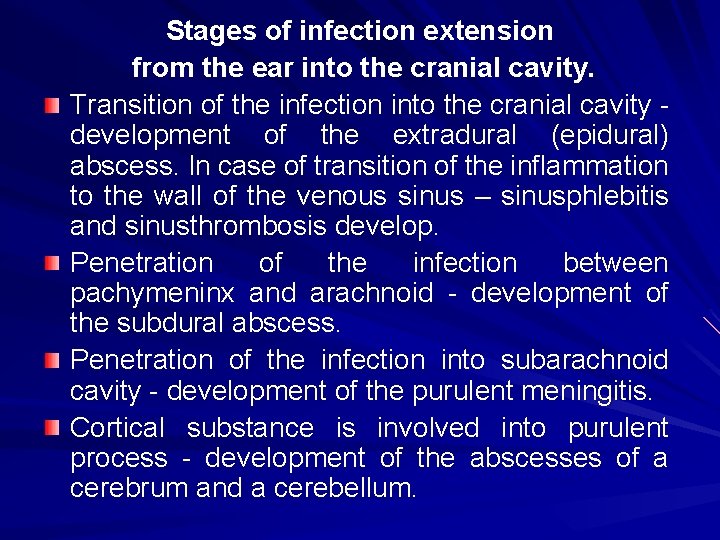

Stages of infection extension from the ear into the cranial cavity. Transition of the infection into the cranial cavity development of the extradural (epidural) abscess. In case of transition of the inflammation to the wall of the venous sinus – sinusphlebitis and sinusthrombosis develop. Penetration of the infection between pachymeninx and arachnoid - development of the subdural abscess. Penetration of the infection into subarachnoid cavity - development of the purulent meningitis. Cortical substance is involved into purulent process - development of the abscesses of a cerebrum and a cerebellum.

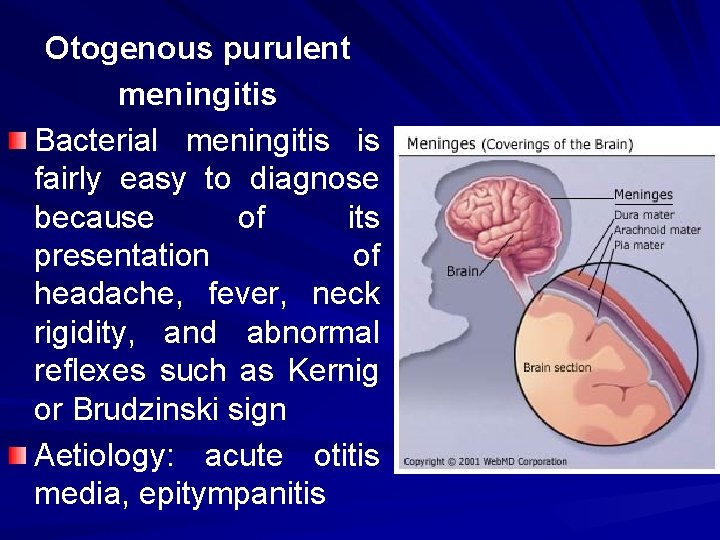

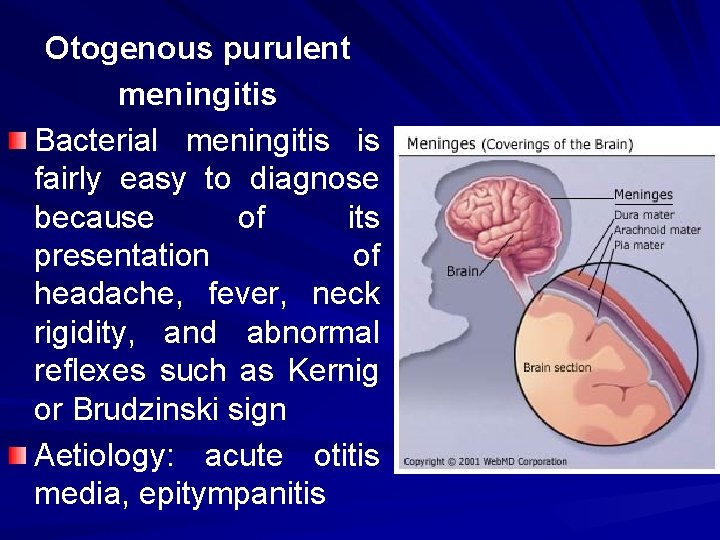

Otogenous purulent meningitis Bacterial meningitis is fairly easy to diagnose because of its presentation of headache, fever, neck rigidity, and abnormal reflexes such as Kernig or Brudzinski sign Aetiology: acute otitis media, epitympanitis

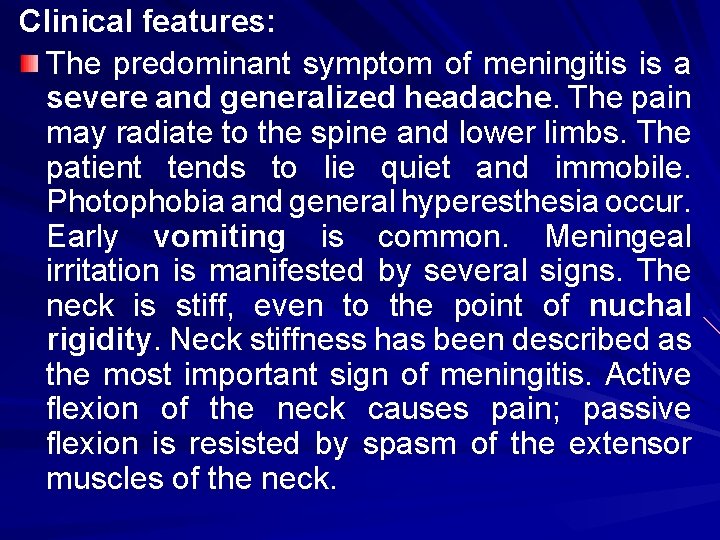

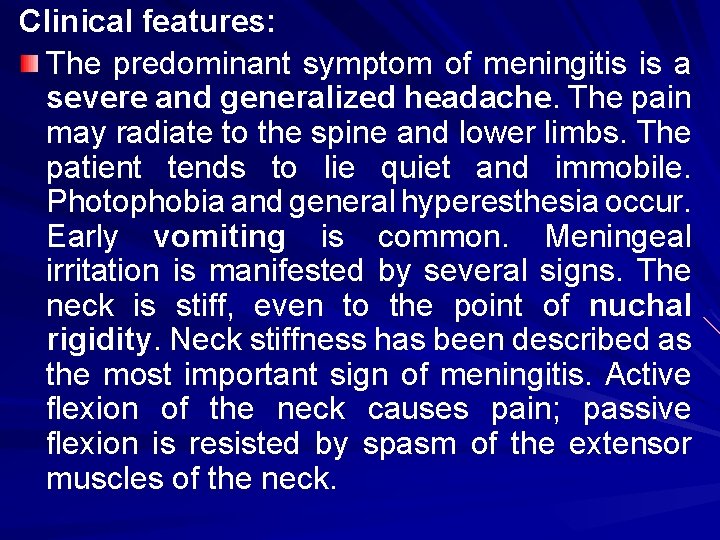

Clinical features: The predominant symptom of meningitis is a severe and generalized headache. The pain may radiate to the spine and lower limbs. The patient tends to lie quiet and immobile. Photophobia and general hyperesthesia occur. Early vomiting is common. Meningeal irritation is manifested by several signs. The neck is stiff, even to the point of nuchal rigidity. Neck stiffness has been described as the most important sign of meningitis. Active flexion of the neck causes pain; passive flexion is resisted by spasm of the extensor muscles of the neck.

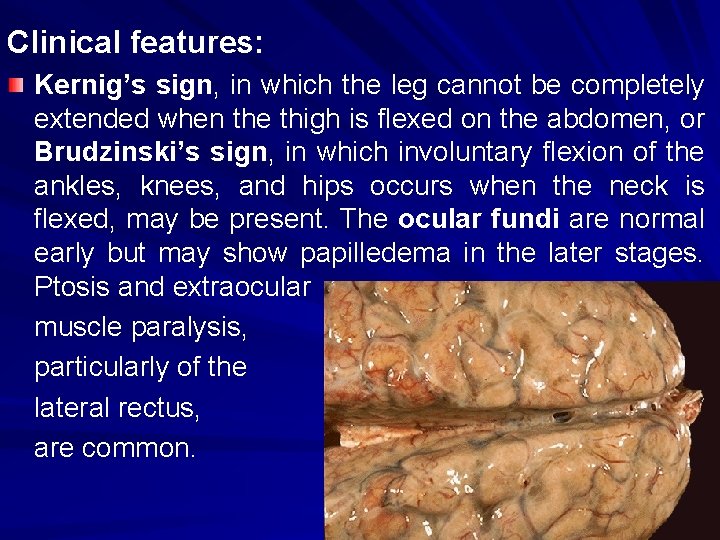

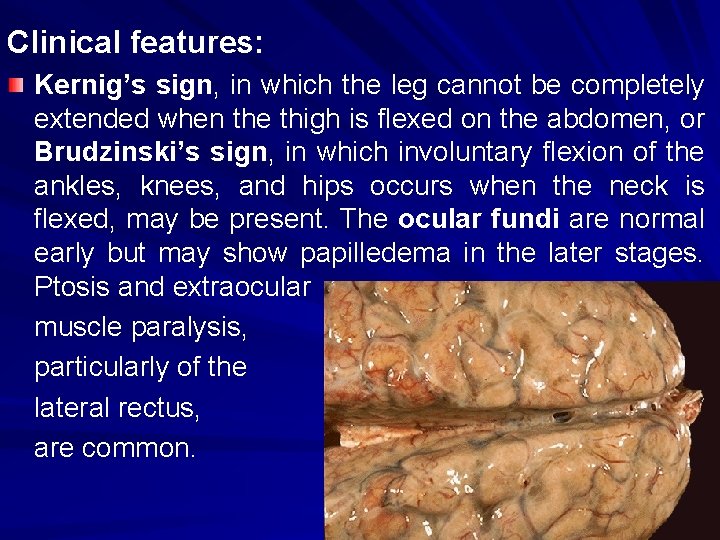

Clinical features: Kernig’s sign, in which the leg cannot be completely extended when the thigh is flexed on the abdomen, or Brudzinski’s sign, in which involuntary flexion of the ankles, knees, and hips occurs when the neck is flexed, may be present. The ocular fundi are normal early but may show papilledema in the later stages. Ptosis and extraocular muscle paralysis, particularly of the lateral rectus, are common.

Nuchal rigidity is not seen in infants younger than age 6 months, but bulging of the fontanelle is a frequent sign. Head retraction and opisthotonos may occur in children. When meningitis complicating otitis media is suspected, palpation of the fontanelle in infants and active or passive flexion of the neck in older patients should be performed during examination of patients with acute or chronic otitis media.

Diagnostics: 1. Laboratory findings Leukocytosis with a left shift in the differential and the presence of bands is the rule. The cerebrospinal fluid pressure is elevated. The density of the fluid varies from slight turbidity to frank opacity. The cerebrospinal fluid glucose may be low compared with the blood glucose. Microorganisms can be shown on Gram’s stain and culture. 2. Additional investigations X-ray mastoid for evaluation of associated ear disease.

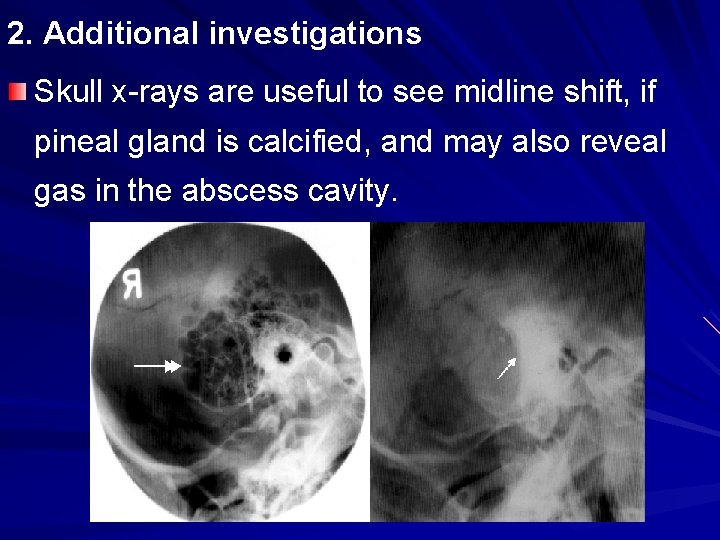

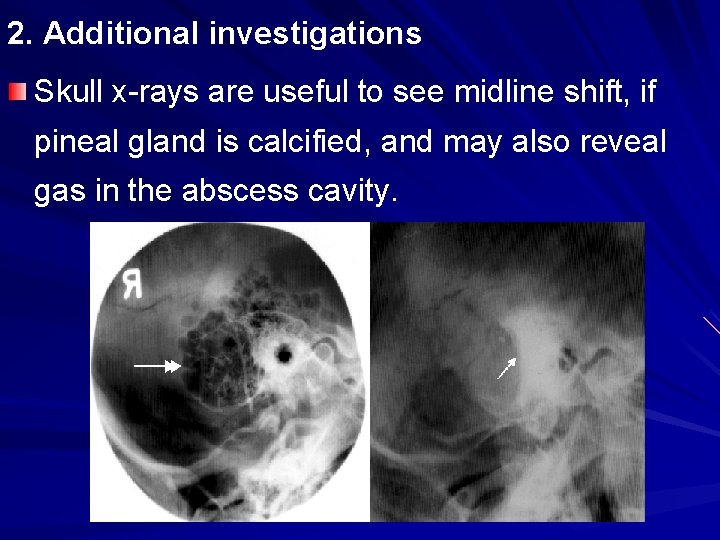

2. Additional investigations Skull x-rays are useful to see midline shift, if pineal gland is calcified, and may also reveal gas in the abscess cavity.

MRI has proven to be superior to CT in evaluating patients with meningitis. An MRI of the brain should be performed to evaluate for subdural empyema, perisinus or epidural abscess, lateral sinus thrombosis, or brain abscess because the incidence of intracranial complication existing with otogenic meningitis is high. 3. Consultation of the ophthalmologist and neurologist.

Treatment: Management is outlined as follows: initial stabilization lumbar puncture to obtain cerebrospinal fluid for analysis and culture initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotics surgical treatment.

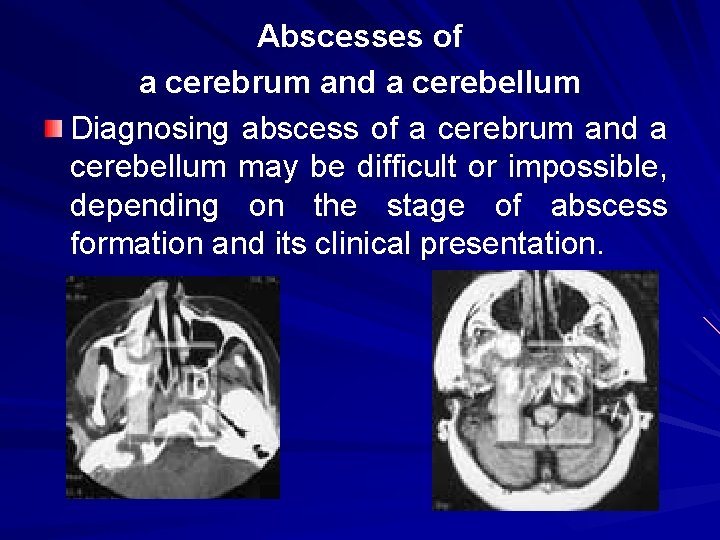

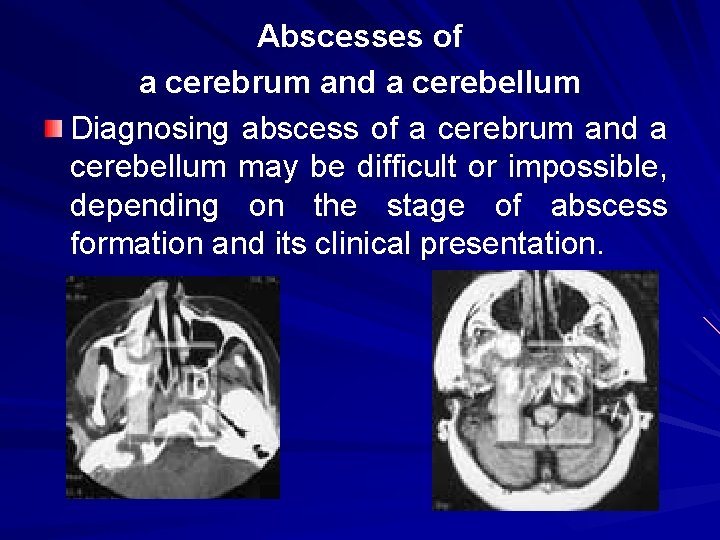

Abscesses of a cerebrum and a cerebellum Diagnosing abscess of a cerebrum and a cerebellum may be difficult or impossible, depending on the stage of abscess formation and its clinical presentation.

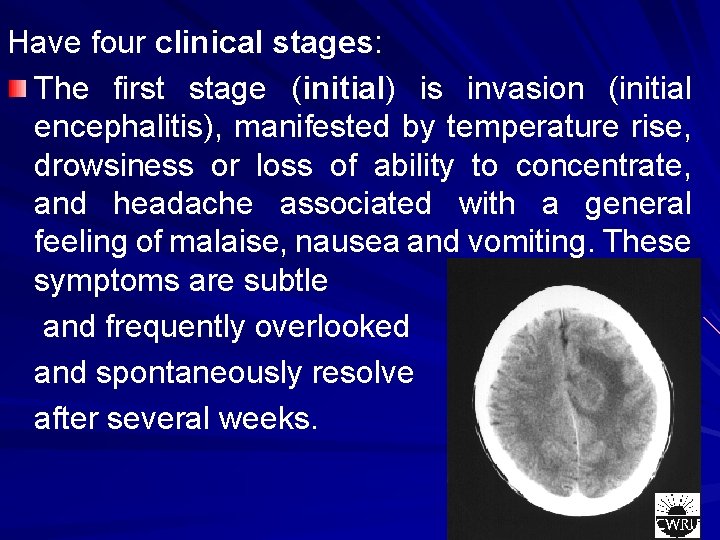

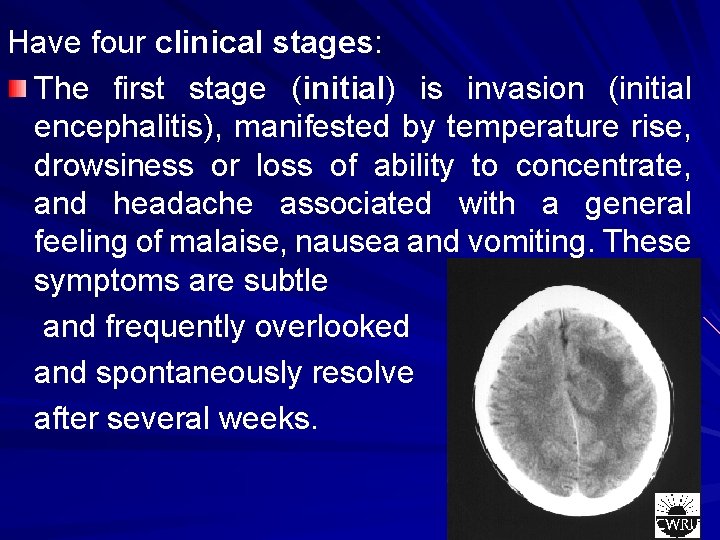

Have four clinical stages: The first stage (initial) is invasion (initial encephalitis), manifested by temperature rise, drowsiness or loss of ability to concentrate, and headache associated with a general feeling of malaise, nausea and vomiting. These symptoms are subtle and frequently overlooked and spontaneously resolve after several weeks.

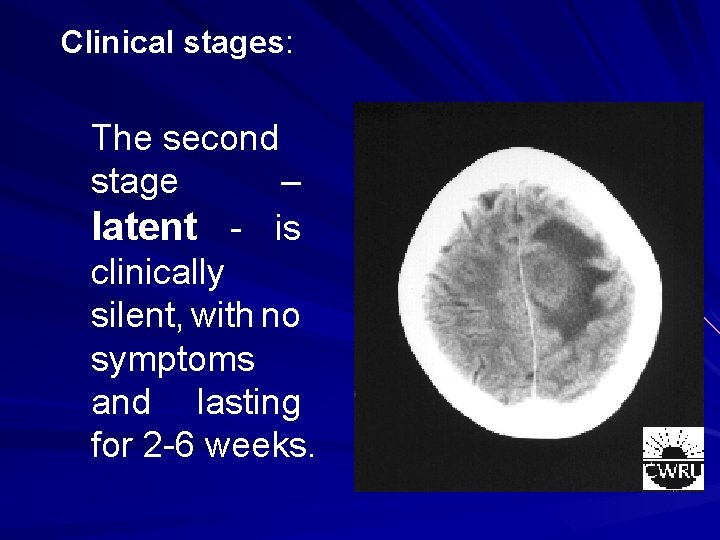

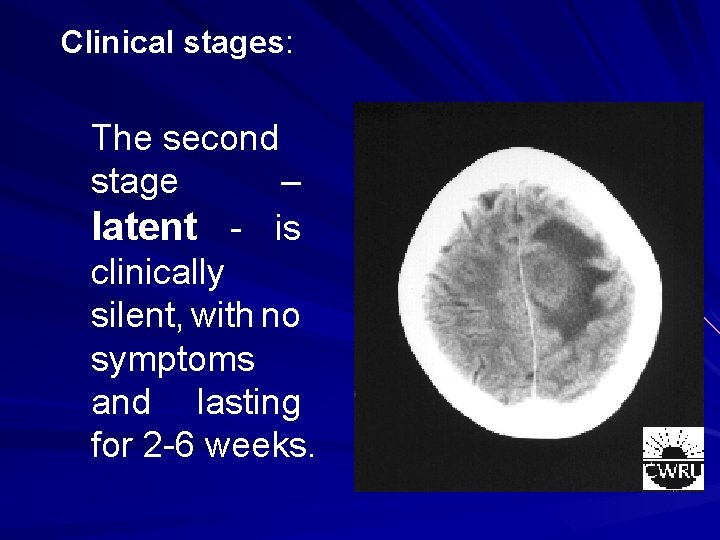

Clinical stages: The second stage – latent - is clinically silent, with no symptoms and lasting for 2 -6 weeks.

During the third stage - frank, enlargement (manifest abscess), an actual abscess forms in the region of the previous cerebritis and produces focal symptoms of a mass lesion, seizures, or loss of consciousness. They are divided into 4 groups: Symptoms peculiar to purulent processes: asthenia, anorexia (absence of appetite), halitosis, exhaustion, furred tongue, stool retention, changes in hemogram, typical for inflammation.

– General cerebral symptoms, which develop as a result of the increase of intracranial pressure: headache, bradycardia, changes in the fundus of eye, rigid neck and Kernig’s sign. – Symptoms of disorder of conduction systems activity and subcortical nuclei: hemiparesis, hemiparalysis, which are observed on the contrary to abscess temporal lobe side, facial paralysis by central type, spasmodic attacks, pyramid Babinski’s sign, Oppenheim’s symptom and other.

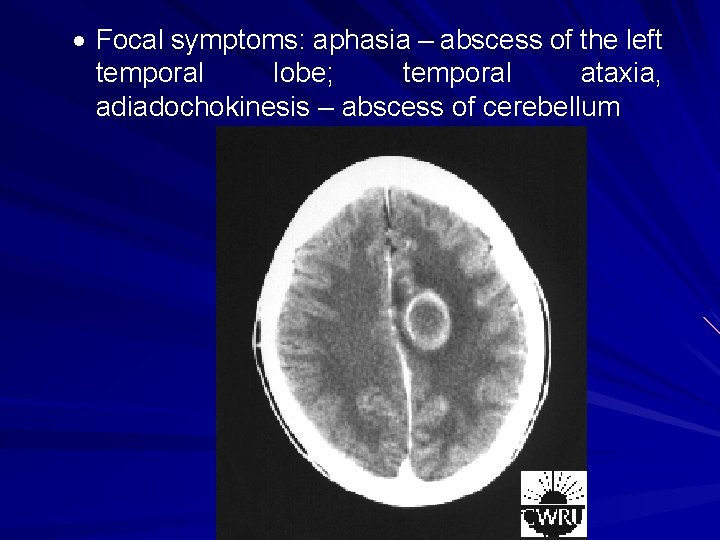

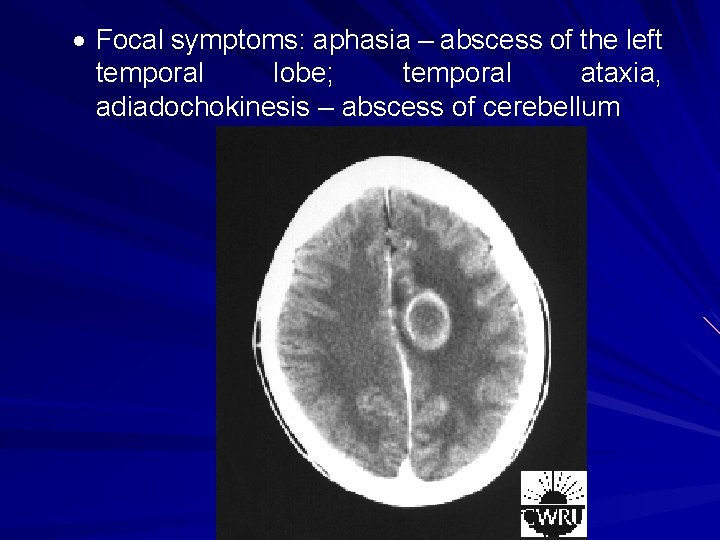

Focal symptoms: aphasia – abscess of the left temporal lobe; temporal ataxia, adiadochokinesis – abscess of cerebellum

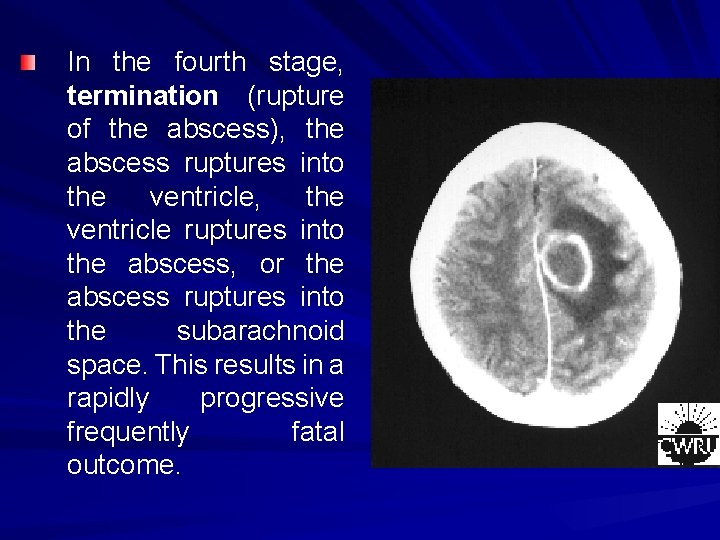

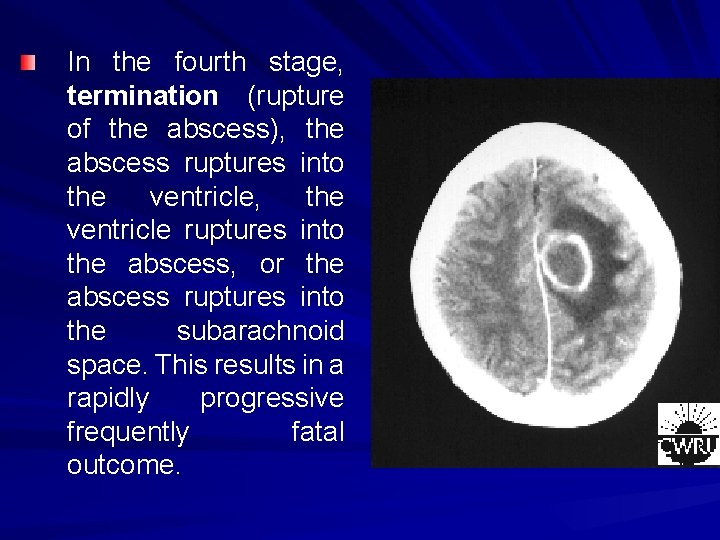

In the fourth stage, termination (rupture of the abscess), the abscess ruptures into the ventricle, the ventricle ruptures into the abscess, or the abscess ruptures into the subarachnoid space. This results in a rapidly progressive frequently fatal outcome.

Diagnostics: X-ray mastoid for evaluation of associated ear disease. Skull x-rays are useful to see midline shift, if pineal gland is calcified, and may also reveal gas in the abscess cavity. CT and MRI easily identify a hypointense center with a hyperintense capsule about a formed abscess. Consultation of the ophthalmologist and neurosurgeon.

Treatment: Management of the primary septic focus and the brain abscess requires a combined neurosurgical and otologic approach. Surgery of the abscess includes aspiration through a burr hole or formal craniotomy, open drainage, or rarely, total excision. This may occur simultaneously with the surgical approach to the ear, or it may precede management of the ear if the intracranial problem is of such severity that it should be managed first. Surgical management of associated chronic otitis media is based on the extent of the underlying disease. For patients with acute otitis media, wide myringotomy and drainage are performed, and mastoidectomy is performed in the presence of coalescent mastoiditis.

Treatment: Intravenous antibiotics are the predominant management of brain abscess and are occasionally recommended as the exclusive management. Multidrug therapy is indicated because of the high incidence of multimicrobial infection. Antibiotic therapy should be maintained for several weeks. Other drugs such as mannitol or dexamethasone may be needed to reduce intracranial pressure. If the patient did not present with seizures, prophylactic anticonvulsant drugs should be used.

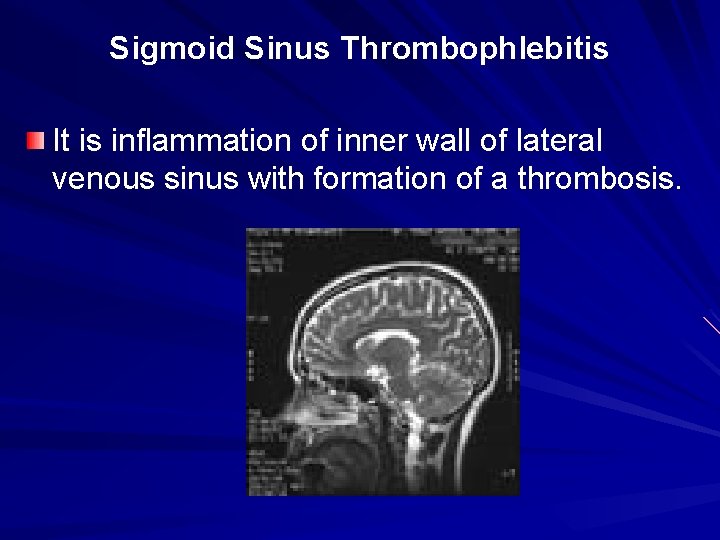

Sigmoid Sinus Thrombophlebitis It is inflammation of inner wall of lateral venous sinus with formation of a thrombosis.

Aetiology: The sigmoid sinus is formed by the confluence of the superior petrosal sinus and the transverse sinus. The lateral, or sigmoid, sinus exits the skull through the jugular foramen to become the internal jugular vein. It is called lateral because it is encountered laterally in mastoid surgery. Lateral sinus thrombosis usually starts with erosion of the bony plate over the sigmoid sinus by mastoiditis. Eventually, a perisinus abscess forms. A mural thrombus then develops within the lumen of the sinus, propagates proximally and distally, and may become infected. The lumen of the vessel is eventually occluded by the propagating thrombus, and infected material may be embolized into the systemic circulation, causing septicemia.

Clinical features: Lateral sinus thrombosis is notoriously difficult to diagnose. General symptoms: hectic fever, tachycardia, paleness of skin, icteritiousness of scleras, leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, anemia

Focal symptoms: Greisinger’s sign: when the thrombophlebitis spreads to the mastoid emissary vein, which communicates to the sigmoid sinus through the mastoid foramen, edema and tenderness may be produced over the mastoid process; Foss’s sign - under auscultation v. jugularis interna venous hum is absent;

Wighting’s sign - particularly over the sternocleidomastoid muscle, when the thrombophlebitis spreads to the jugular bulb and internal jugular vein, it may produce pain in the neck, particularly with rotation of the neck. This may mimic the nuchal rigidity seen with meningitis, or the patient may present with torticollis. The thrombus may be palpated as a tender cord in the neck.

Diagnostics: X-ray mastoid for evaluation of associated ear disease. Skull x-rays are useful to see midline shift, if pineal gland is calcified, and may also reveal gas in the abscess cavity. CT may fail to identify a dural sinus thrombosis. MRI has proven very useful and is the imaging method of choice. Consultation of the ophthalmologist and neurosurgeon.

Treatment Lateral sinus thrombosis requires prompt mastoid surgery for definitive management. A complete mastoidectomy is performed, and the sigmoid sinus is exposed. After the thrombosis has been evacuated and the patient has been maintained on antibiotics for approximately 2 weeks, follow-up MRI of the brain should be obtained to detect a late embolic brain abscess. Also anticoagulants, symptomatic therapy are used.