Chronic gastritis Chronic gastritis is a histopathologic entity

- Slides: 62

Chronic gastritis

Chronic gastritis is a histopathologic entity characterized by chronic inflammation of the stomach mucosa. Gastritides can be classified on basis of the underlying cause (e. g, Helichobacter pylori, bile reflux, non steroidal anti- inflammatory drugs, autoimmunity or allergic responses) and the histopathologic pattern which may suggest the cause (e. g. , H. pylori-associated multifocal atrophic gastritis). H. pylori gastritis is a primary infection of the stomach and is the most frequent cause of chronic gastritis.

Until 1980 researches into gastritis were not attractive as there were many classifications that differ from one contry to another, sometimes from one department to another and even within the same institution. Depending on the investigator concerned. all this made the comparison of the results of the various scientific stydies virtually impossible and no uniform therapy for the diagnosed gastritis can be made. Until the discovery of helichobacter pylori(formly campylobacter pylori) by warren and marshal in 1983, gastritis was considered as a more or less useful histologic finding but not a disease.

In 1990. on the basis of the new etiological facts on gastritis that has been collected, a new system of classification finally was presented at the world congress of gastroenterology held in Sydney, Australia. This Sydney system was based largely on previous proporsals made in UK and Germany. The distinctive features of this new system was that it take in considerations etiology, topography and morphology of gastritis.

the Sydney was however not immediately accepted everywhere and the critism was voiced particularly in the united states that older entities of gastritis as diffuse antral gastritis and multifocal atrophic gastritis(MAG) apparently no longer appeared in the classification. As a consequence of such critism, Sydney system was updated 1994 at h. pylori congress held in Houston USA.

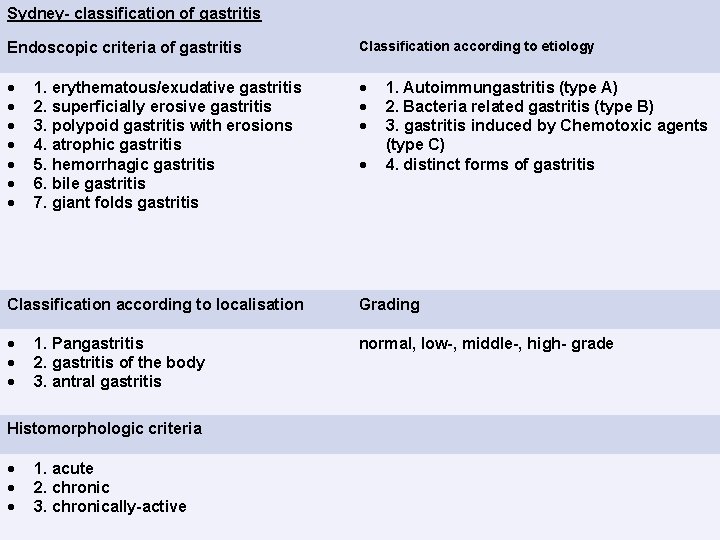

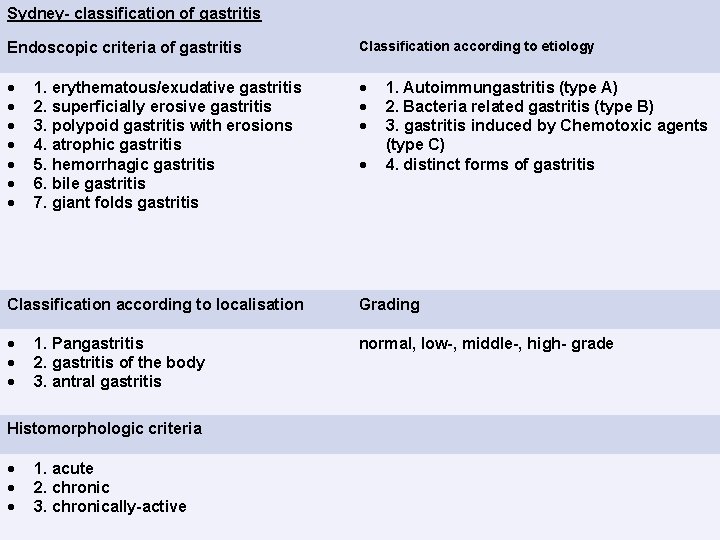

Sydney- classification of gastritis Endoscopic criteria of gastritis Classification according to etiology 1. erythematous/exudative gastritis 2. superficially erosive gastritis 3. polypoid gastritis with erosions 4. atrophic gastritis 5. hemorrhagic gastritis 6. bile gastritis 7. giant folds gastritis 1. Autoimmungastritis (type A) 2. Bacteria related gastritis (type B) 3. gastritis induced by Chemotoxic agents (type C) 4. distinct forms of gastritis Classification according to localisation Grading normal, low-, middle-, high- grade 1. Pangastritis 2. gastritis of the body 3. antral gastritis Histomorphologic criteria 1. acute 2. chronic 3. chronically-active

Original Sydney system considered two biopsies each from the antrum and the corpus. In the updated Sydney system, an additional biopsy taken from incisura angularis is recommended. This additional biopsy was believed to be necessary as the maximal degree of atrophy and intestinal metaplasia are found in the region of incisura angularis. Prospective studies aimed at establishing wheather the incisura angularis biopsy actually were unable to find any advantage provided by the additional angulus biopsy compared with that provided by the standard two antral and two corpus biopsies. Actually the accurate diagnosis of gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia are inaccurate as the radiologist may take a normal gastric biopsy leaving the affected neighbouring focus giving false negative result and vice versa. Making the taking of multiple biopsies from different parts of the stomach in different countainers and labeling each containers is essentially important.

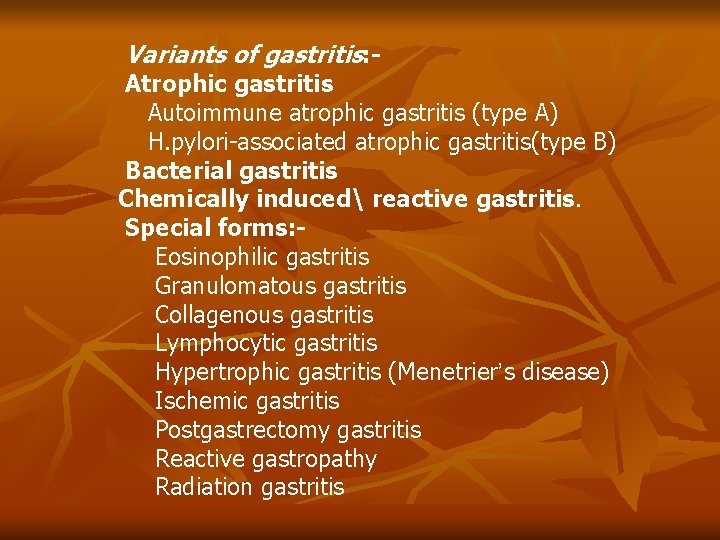

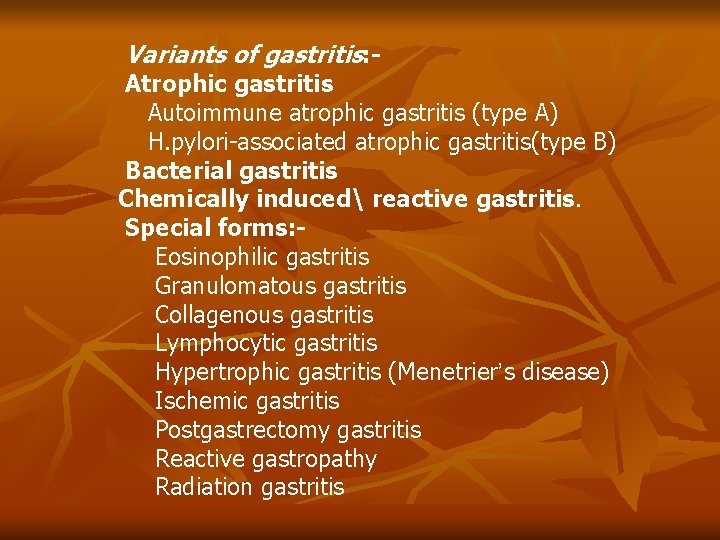

Variants of gastritis: - Atrophic gastritis Autoimmune atrophic gastritis (type A) H. pylori-associated atrophic gastritis(type B) Bacterial gastritis Chemically induced reactive gastritis. Special forms: Eosinophilic gastritis Granulomatous gastritis Collagenous gastritis Lymphocytic gastritis Hypertrophic gastritis (Menetrier’s disease) Ischemic gastritis Postgastrectomy gastritis Reactive gastropathy Radiation gastritis

Atrophic gastritis n Atrophic gastritis is a condition of chronic inflammation and atrophy (tissue destruction) affecting the stomach's mucosal lining. Over time, atrophic gastritis leads to a loss of the gastric glandular and chief cells, a subsequent breakdown of the mucosal lining, and an eventual replacement of the mucosa by intestinal and fibrous tissue.

Atrophic gastritis has two causes: 1) an autoimmune process targeting parietal cells or intrinsic factor and 2) environmental causes such as persistent infection with Helicobacter pylori bacteria or dietary factors. Recent evidence suggests that Helicobacter pylori can trigger the development of autoimmune atrophic gastritis through a process of molecular mimicry in which the bacterial organisms take on the appearance of parietal cells.

However, these two types of gastritis are distinct, with each disorder causing different tissue changes when biopsy samples are examined. In autoimmune gastritis tissue destruction is restricted to the gastric corpus and fundus, whereas infectious gastritis is a multifocal process with more extensive involvement of the structures related to the gastric corpus and fundus. Atrophic gastritis associated with Helicobacter pylori is also less likely to cause symptoms and more likely to lead to the development of stomach cancer.

Autoimmune gastritis n Autoimmune gastritis: - it is characterized by atrophy of the glands caused by cells of the body own immune defense system. Two different forms of autoimmune gastritis casn be differentiated, the active form which is characreized by periglandular lymphocytic infiltration with local destruction of the corpus glands and hypertrophy of the parietal cells and the burned out form which involve complete atrophy of the parital cells with only low grade of chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate.

n Previously it was believed that both forms were associated serologically with antibodies against parital cells andor intrinsic factors but recently it was approved that some of the antibodies developed against h. pylori may react with proton pump of the parital cells as antigens. H. pylori thus stimulate the formation of autoantibodies and the active autoimmune gastritis that is simultaneously associated with infection with h. pylori seem to be healed by eradication of the organism. however numerous questions still unable to be answered for example, it is not sufficiently well known which bacterial and host factors can trigger this autoimmunity.

n In autoimmune atrophic gastritis, autoantbodies cause destruction of the parietal cell mass that makes up the gastric mucosa. The autoimmune response causes an infiltration of white blood cells and the release of chemical cytokines that accelerate the disease process. Ultimately, the autoimmune response impairs the mucosal cells' ability to produce hydrochloric acid, digestive enzymes such as pepsin, and intrinsic factor, a substance needed for the absorption of vitamin B 12.

n n Deficiencies of intrinsic factor lead to vitamin B 12 deficiency and a condition of pernicious anemia. Deficiencies of hydrochloric acid (hypochlorhydria) induce the production of G (Gastrin producing) cells. Increased proliferation of G cells causes excess gastrin production, which in turn increases the risk for development of gastric polyps and gastric adenocarcinoma (stomach cancer). Early in the course of the disease, symptoms rarely occur although mild symptoms of indigestion may be present.

n Autoimmune atrophic gastritis is the most frequent cause of pernicious anemia in temperate climates. The risk of gastric adenocarcinoma is reported to be at least 2. 9 times higher in patients with pernicious anemia than in the general population. Patients with pernicious anemia are also at increased risk for esophageal squamous-cell carcinomas.

n Autoimmune atrophic gastritis typically causes symptoms related to vitamin B 12 (cobalmin) deficiency, including anemia, gastrointestinal symptoms, and neurologic symptoms including dementia. Megaloblastic anemia may develop, and rarely platelet deficiency (thrombocytopenia) may occur. Symptoms of anemia include weakness, lightheadedness, vertigo, tinnitus, palpitations, angina and symptoms of congestive heart failure. Other symptoms include sore tongue, weight loss, irritability, mild jaundice, and heart enlargement.

Incidence n n The frequency of atrophic gastritis is not known because chronic gastritis does not usually cause symptoms. Females are at higher risk for autoimmune atrophic gastritis with three times as many women affected as men. Patients with other autoimmune disorders, especially autoimmune thyroid disorders, are more likely to develop atrophic gastritis. Atrophic gastritis is the most common autoimmune disease to develop in patients with Graves' disease who have been treated with radioiodine. Autoimmune atrophic gastritis is more frequent in individuals of northern European descent and in African Americans. It is much less common in people of southern European descent and in Asians. Atrophic gastritis is not usually detected until the 6 th decade of life when symptoms of pernicious anemia develop. However, pernicious anemia has been detected in people of all ages.

Bacterial gastritis: n n Helicobacter pylori (previously named Campylobacter pyloridis), is a Gram-negative, microaerophilic bacterium found in the stomach. It was identified in 1982 by Barry Marshall and Robin Warren, who found that it was present in patients with chronic gastritis and gastric ulcers, conditions that were not previously believed to have a microbial cause. It is also linked to the development of duodenal ulcers and stomach cancer. It is one of the most common human pathogens. It is present nearly in about 50% of the world wide population (the incidence is about 20%in developed countries and more than 60% in the developing ones). The highest incidence recorded in Asia, Africa and south America.

H. pylori colonize the human stomach and persist for several decades causing chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer diseases. It is also considered as an important risk factor for development of gastric carcinoma. For this reason, H. pylori was classified as type I carcinogen by International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). H. pylori is contagious, although the exact route of transmission is not known. Person-to-person transmission by either the oral-oral or fecal-oral route is most likely. Consistent with these transmission routes, the bacteria have been isolated from feces, saliva and dental plaque of some infected people.

Signs and symptoms n n Over 80% of people infected with H. pylori show no symptoms. Acute infection may appear as an acute gastritis with abdominal pain (stomach ache) or nausea. Where this develops into chronic gastritis, the symptoms, if present, are often those of non-ulcer dyspepsia: stomach pains, nausea, bloating, belching, and sometimes vomiting or black stool. Individuals infected with H. pylori have a 10 to 20% lifetime risk of developing peptic ulcers and a 1 to 2% risk of acquiring stomach cancer.

n Inflammation of the pyloric antrum is more likely to lead to duodenal ulcers, while inflammation of the corpus (body of the stomach) is more likely to lead to gastric ulcers and gastric carcinoma. However, it is possible that H. pylori plays a role only in the first stage that leads to common chronic inflammation, but not in further stages leading to carcinogenesis.

Microbiology n H. pylori is a helix-shaped (classified as a curved rod, not spirochaete), Gram-negative bacterium, about 3 micrometres long with a diameter of about 0. 5 micrometres. It is microaerophilic; that is, it requires oxygen, but at lower concentration than is found in the atmosphere. It contains a hydrogenase which can be used to obtain energy by oxidizing molecular hydrogen (H 2) produced by intestinal bacteria. It produces oxidase, catalase, and urease. It is capable of forming biofilms] and can convert from spiral to a possibly viable but nonculturable coccoid form. both likely to favor its survival and be factors in the epidemiology of the bacterium.

n H. pylori has four to six lophotrichous flagella; all gastric and enterohepatic Helicobacter species are highly motile due to flagella. The characteristic sheathed flagellar filaments of Helicobacter are composed of two copolymerized flagellins, Fla. A and Fla. B.

n H. pylori consists of a large diversity of strains Study of the H. pylori genome is centered on attempts to understand pathogenesis, the ability of this organism to cause disease. , 40 kb-long Cag pathogenicity island (a common gene sequence believed responsible for pathogenesis) that contains over 40 genes. This pathogenicity island is usually absent from H. pylori strains isolated from humans who are carriers of H. pylori, but remain asymptomatic.

Pathophysiology n n To colonize the stomach, H. pylori must survive the acidic p. H of the lumeng. 1) it use its flagella to burrow into the mucus to reach its niche, close to the stomach's epithelial cell layer. Many bacteria can be found deep in the mucus, which is continuously secreted by mucussecreting cells and removed on the luminal side. To avoid being carried into the lumen. 2) H. pylori senses the p. H gradient within the mucus layer by chemotaxis and swims away from the acidic contents of the lumen towards the more neutral p. H environment of the epithelial cell surface. 3)H. pylori is also found on the inner surface of the stomach epithelial cells and occasionally inside epithelial cells.

n n 4)It produces adhesins which bind to membrane-associated lipids and carbohydrates and help it adhere to epithelial cells. 5)H. pylori produces large amounts of the enzyme urease, molecules of which are localized inside and outside of the bacterium. Urease breaks down urea (which is normally secreted into the stomach) to carbon dioxide and ammonia. The ammonia is converted to ammonium by accepting a proton (H+), which neutralizes gastric acid. The survival of H. pylori in the acidic stomach is dependent on urease. The ammonia produced is toxic to the epithelial cells, and, along with the other products of H. pylori—including proteases, vacuolating cytotoxin A (Vac. A), and certain phospholipases—, damages those cells.

n The type of ulcer that develops depends on the location of chronic gastritis, which occurs at the site of H. pylori colonization. The acidity within the stomach lumen affects the colonization pattern of H. pylori, and therefore ultimately determines whether a duodenal or gastric ulcer will form. In people producing large amounts of acid, H. pylori colonizes the antrum of the stomach to avoid the acid-secreting parietal cells located in the corpus (main body) of the stomach. The inflammatory response to the bacteria induces G cells in the antrum to secrete the hormone gastrin, which travels through the bloodstream to the corpus. . Gastrin stimulates the parietal cells in the corpus to secrete even more acid into the stomach lumen. Chronically increased gastrin levels eventually cause the number of parietal cells to also increase, further escalating the amount of acid secreted. ] The increased acid load damages the duodenum, and ulceration may eventually result. In contrast, gastric ulcers are often associated with normal or reduced gastric acid production, suggesting the mechanisms that protect the gastric mucosa are defective. In these patients, H. pylori can also colonize the corpus of the stomach, where the acidsecreting parietal cells are located

Epidemiology n At least half the world's population are infected by the bacterium, making it the most widespread infection in the world. Actual infection rates vary from nation to nation; the developing world has much higher infection rates than the West (Western Europe, North America, Australasia), where rates are estimated to be around 25%. The age at which this bacterium is acquired seems to influence the possible pathologic outcome of the infection : people infected with it at an early age are likely to develop more intense inflammation that may be followed by atrophic gastritis with a higher subsequent risk of gastric ulcer, gastric cancer or both. Acquisition at an older age brings different gastric changes more likely to lead to duodenal ulcer Infections are usually acquired in early childhood in all countries. However, the infection rate of children in developing nations is higher than in industrialized nations, probably due to poor sanitary conditions

Pathogenic strains of Helicobacter pylori produce a potent exotoxin, Vac. A, which causes progressive vacuolation as well as gastric injury. Most H. pylori strains secrete Vac. A into the extracellular space. After exposure of Vac. A to acidic or basic p. H, re-oligomerized Vac. A (mainly 6 monomeric units) at neutral p. H is more toxic. Although the mechanisms have not been defined, Vac. A induces multiple effects on epithelial and lymphatic cells, i. e. , vacuolation with alterations of endo-lysosomal function, anion -selective channel formation, mitochondrial damage, and the inhibition of primary human CD 4+ cell proliferation. is known to stimulate apoptosis via a mitochondria-dependent pathway.

n most of Vac. A was localized to vacuoles rather than mitochondria. Vac. A reduced the membrane potential of isolated mitochondria without inducing cytochrome c release, suggesting that it did not act directly to induce cytochrome c release from mitochondria and that in intact cells

n There are many strains of H. pylori, but generally H. pylori can be classified to only two categories either cag. A+ve or –ve groups according to a specific gene in the bacteria was discovered in 1989 called cag (cytotoxin associated gene) that encodes for a specific antigen called cag. A. n n n More than 90% of the isolated cag. A+ve strains from east Asia including Korea, Japan and China (where the highest incidence of gastric cancer). Intracellular bacterial and viral pathogens that established persistent infections have evolved multiple strategies to interfere with host signaling pathways and immune responses. they do so to create an intracellular safe heaven while avoiding killing the host cell.

n n n Several viral oncogenes inactivate the tumor suppressor activity of the host cell by targeting and degrading p 53 when infection is established. Although H. pylori is not an intracellular pathogen, its interactions with host cells may provide certain survival benefits for the bacterium and contribute to establishment of chronic infection. Hp uses host plasma cell membrane as a site for replication and formation of microcolonies. Colonization of the stomach by Hp is greatly enhanced when the apoptotic response of the gastric epithelial cells is impaired which is done by cag. A that induce upregulation of the antiapoptotic protein MCL-1 , so the affected cells become more resistant to the normal cell turn over in the stomach. Hp cause down-regulation of p 53 indirectly through interaction with ASPP 2 proapoptotic gene.

n n Here we will discuss the role of cag. A on p 53 through its interaction with ASPP 2 but firstly we should know how cag. A is delivered from H. pylori to inside the host cell. There are many secretion systems by which the organism inject its proteins inside the host cell. Gram negative bacteria use six different secretion systems. H. pylori use type IV secretion system

Type IV secretion system (T 4 SS or TFSS) n n n It is homologous to conjugation machinery of bacteria. It is capable of transporting both DNA and proteins. It was discovered in Agrobacterium tumefaciens, which uses this system to introduce the T-DNA portion of the Ti plasmid into the plant host, which in turn causes the affected area to develop into a crown gall (tumor). Helicobacter pylori uses a type IV secretion system to deliver cag. A into gastric epithelial cells, which is associated with gastric carcinogenesis. Bortedella pertussis, the causative agent of whooping cough, secretes the pertussis toxin partly through the type IV system. Protein members of this family are components of the type IV secretion system. They mediate intracellular transfer of macromolecules via a mechanism ancestrally related to that of bacterial conjugation machineries.

Function n n In short, Type IV secretion system (T 4 SS), is the general mechanism by which bacterial cells secrete or take up macromolecules. Their precise mechanism remains unknown. T 4 SS are cell envelope-spanning complexes or in other words 11 -13 core proteins that form a channel through which DNA and proteins can travel from the cytoplasm of the donor cell to the cytoplasm of the recipient cell. Now cag. A is inside the gastric cell.

n n cag. A is directly translocated from H. pylori into the gastric epithelial cells via TFSS or type IV secretion system and localize to the host plasma membrane where the full length protein interacts with components of the apical junctional complex of the cell including E-cadherine, Jam that promote loss of cell polarity and enhance invasiveness of the cell. C-terminal and N- terminal domains of cag. A both are required for full activity of the protein. Expression of C-terminal domain alone of cag. A initiate receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and cause scattering of the cell. However, the junctional complexes of the cell remain intact and the cell does not become migratory or invasive.

n n n In absence of N- terminal domain, the C- domain of cag. A is primarily localize to the cytoplasm. While coexpression of both C and N-domains induce a strong accumulation of both domains near the plasma membrane, suggesting the role of N-domain to target cag. A toward plasma membrane of the affected cell. Cag. A modulate the activity of ASPP 2 by simply binding its N domain to the ASPP 2 protein. After this interaction; ASPP 2 recruits and binds cytoplasmic p 53 which is then degraded by proteisomes. Cag. A mediated degradation of p 53 results in resistance in the apoptotic response in an ASPP 2 -dependent manner.

n n ASPP are family of proteins that include ASPP 1, ASPP 2 and i. ASPP. Both ASPP 1&2 are proapoptotic proteins that activate p 53 while i. ASPP inhibite the apoptotic function of p 53. ASPP 2 is expressed in many human tissues such as heart, brain, placenta, lung, liver, skeletal muscle, kidney, pancreas, but at varying levels. The highest expression level of ASPP 2 was detected in skeletal tissue On DNA damage, cellular stress or oncogenic stimuli; the Cterminal domain of ASPP 2 transiently interact with the DNA binding domain of p 53 which in turn induce expression of genes involved in apoptosis like BAX& PUMA and PIG 3, all of which are positive regulators of programmed cell death. ASPP 2 also bind to other factors that play a role in apoptosis as Bcl 2 and Yes-associated protein And factors that control cell growth as p 65 and APC tumor suppressor.

n The C terminus of ASPP 2 interacts with the DNA-binding domain of p 53, but it is unclear how this interaction leads to activation of p 53. The N terminus of ASPP 2 is required to enhance the transcriptional activity of p 53, suggesting that this domain may have a regulatory role and determine the outcome of the ASPP 2 -p 53 interaction. Posttranslational modification of the N terminus of ASPP 2, as well as an alteration in the set of proteins that interact with this domain, may determine the fate of p 53 and thereby, affect the apoptotic response. For example, cytosolic DDA 3 binds ASPP 2 and prevents activation of p 53 without affecting the ASPP 2 -p 53 interaction. The function of ASPP 2 is not restricted to activation of p 53 but includes regulation of cell–cell adhesion and polarity.

n We did not detect the formation of a ternary complex between cag. A, ASPP 2 and p 53 perhaps owing to a transient nature of any interactions and also unclear whether the associations between cag. A-ASPP 2 and ASPP 2 -p 53 occur simultaneously or sequentially and in which cytosolic region the ASPP 3 -p 53 complex is formed.

n n Type V secretion system (T 5 SS) Also called the autotransporter system, type V secretion involves use of the Sec system for crossing the inner membrane. Proteins which use this pathway have the capability to form a beta-barrel with their C-terminus which inserts into the outer membrane, allowing the rest of the peptide (the passenger domain) to reach the outside of the cell. Often, autotransporters are cleaved, leaving the beta-barrel domain in the outer membrane and freeing the passenger domain. Some people believe remnants of the autotransporters gave rise to the porins which form similar beta-barrel structures. [citation needed] A common example of an autotransporter that uses this secretion system is the Trimeric Autotransporter Adhesins.

Helichobacter heilmannii gastritis: n It is a relatively rare form of gastritis its incidance is about 11000 this bacterium is corkscrew like in appearance 2 -3 times as long as h. pylori so it can be detected easily it cause less degree of gastritis than h. pylori and the intestinal mataplasia or atrophy is somewhat rare compared with h. pylori, it is mostly acquired from domestic animals.

Esinophilic gastritis: n Primary eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders are defined as disorders that selectively affect the gastrointestinal tract with eosinophil-rich inflammation in the absence of known causes for eosinophilia (eg, drug reactions, parasitic infections, and malignancy). These disorders include eosinophilic esophagitis, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, eosinophilic enteritis, and eosinophilic colitis and are occurring with increasing frequency.

n Significant progress has been made in elucidating that eosinophils are integral members of the gastrointestinal mucosal immune system and that eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders are primarily polygenic allergic disorders that involve mechanisms that fall between pure Ig. E-mediated and delayed T(H)2 -type responses. Preclinical studies have identified a contributory role for the cytokine IL-5 and the eotaxin chemokines, providing a rationale for specific disease therapy. An essential question is to determine the cellular and molecular basis for each of these clinical problems and the best treatment regimen, which is the main subject of this review.

n n n Eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EGE) is an uncommon gastrointestinal disease affecting both children and adults. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis is characterized by the following: The presence of abnormal GI symptoms, most often abdominal pain Eosinophilic infiltration in one or more areas of the GI tract, defined as 20 or more eosinophils per highpower field The absence of an identified cause of eosinophilia The exclusion of eosinophilic involvement in organs other than the GI tract A history of atopy or food allergies is often present.

Clinical symptoms are determined by the anatomical locations of eosinophilic infiltrates and the depth of GI involvement. Kaijser was probably the first to report a patient with eosinophilic gastroenteritis in 1937; since then, the number of case reports has increased. Treatments are often unsatisfactory, and long-term outcomes are uncertain.

n n Pathophysiology The underlying molecular mechanism predisposing to the clinical manifestation of eosinophilic gastroenteritis is unknown. Eosinophilic gastritis, enteritis, and gastroenteritis are diseases characterized by the selective infiltration of eosinophils in the stomach, small intestine, or both. The disorders are classified into primary and secondary subtypes. The primary subtypes, which have also been called idiopathic or allergic GE, include the atopic, nonatopic, and familial subtypes.

n n In patients, manifestations of their diseases are based on histologic involvement: mucosal, muscularis, or serosal forms. Any layer of the GI tract can be involved. The secondary subtypes may be divided into 2 groups: systemic eosinophilic disorders (ie, hypereosinophilic disorders) and noneosinophilic disorders (eg, celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, vasculitis). Although these diseases are idiopathic, recent investigations support the role of eosinophils, T helper 2 (Th 2) cytokines (interleukin [IL]-3, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13), and eotaxin as the critical factors in the pathogenesis of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Eosinophils function as antigen presenting cells as they express major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules.

n n In addition, eosinophils can mediate proinflammatory effects, including the up-regulation of adhesion systems, modulation of cell trafficking, and cellular activation states by releasing cytokines (IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, IL-16, IL-18, and transforming growth factor [TGF]-alpha/beta), chemokines (RANTES and eotaxin), and lipid mediators (platelet activating factor [PAF] and leukotriene C 4). Eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EGE) in the adult is a distinctive pathologically-based disorder characterized by an eosinophilpredominant mucosal inflammatory process. Most often, the disorder is detected during endoscopic investigation for abdominal pain or diarrhea. Other causes of gastric and intestinal mucosal eosinophilia require exclusion, including parasitic infections and drug-induced causes. Occasionally, the muscle wall or serosal surface may be involved. EGE appears to be more readily recognized, in large part, due to an evolution in the imaging methods used to evaluate abdominal pain and diarrhea, in particular, endoscopic imaging and mucosal biopsies.

n Definition of EGE, however, may be difficult, as the normal ranges of eosinophil numbers in normal and abnormal gastric and intestinal mucosa are not well standardized. Also, the eosinophilic inflammatory process may be either patchy or diffuse and the detection of the eosinophilic infiltrates may vary depending on the method of biopsy fixation. Treatment has traditionally focused on resolution of symptoms, and, in some instances, eosinophil quantification in pre-treatment and post-treatment biopsies. Future evaluation and treatment of EGE may depend on precise serological biomarkers to aid in definition of the long-term natural history of the disorder and its response to pharmacological or biological forms of therapy.

Granulomatous Gastritis n Gastric inflammation containing granulomas

Diagnostic Criteria n n n n Granulomas usually superficial May be seen to be transmural on resection specimens Usually non-necrotic Variable acute and chronic inflammation May be focal or diffuse Most common in antrum. Various causes – should be ruled out and addressed in report Crohn disease is most common cause of cases Diagnosis usually already known from intestinal evaluation Sarcoidosis may present without thoracic disease Foreign body reaction May be due to drugs, including antacids Infection must always be ruled out Mycobacteria Fungi Parasites Common variable immunodeficiency

n n n n Rare granulomas in stomach Granulomas may be seen adjacent to gastric neoplasms Isolated, idiopathic – very rare, if it exists at all Has been termed Isolated Granulomatous Gastritis (IGG) Primarily reported in adults Role of Helicobacter is controversial Some report it as the most common cause after above excluded Endoscopic appearance ranges from non-specific minor changes to thickened mucosal folds with outlet obstruction

Lymphocytic gastritis n Lymphocytic gastritis is characterized by accumulation of lymphocytes in surface epithelium of stomach. The disease was associated with Helicobacter pylori infection and celiac disease. It is found in approximately 1% of gastric biopsies from patients dyspeptics. Diagnosis is usually counted over 25 intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 epithelial cells. Special type of gastritis may be associated with an apparently normal gastric mucosa. However, endoscopic appearance of rough with prominent gastric folds contains small nodular erosions surrounded by gray-white margin hyperemia, maximal at the gastric body and fundus. This is called general endoscopic gastritis "varioliforma.

n Lymphocytic gastritis is now recognized as a special type of chronic gastritis characterized by a large number of intraepithelial lymphocytes in antral mucosa or oxintica. The frequency of lymphocytic gastritis rarely exceeds 5% of histological diagnoses of gastric biopsies. Diagnosis may be made by hematoxylin eosin staining. Very little is known about etiopatologia, meaning and evolotia disease.

n Aetiology of lymphocytic gastritis is unknown. It was attributed to an atypical response to infection with Helicobacter pylori. Although many patients were found seropositive for this infection is not usually confirmed histologically. Lymphocytic gastritis is frequently found in patients with celiac disease. He suggested theory that lymphocytic gastritis is present as a diffuse lymphocytic gastroenteropatiei part of the expression and location varies.

Chemical Gastritis / Reactive Gastropathy n Gastric changes due to injury to the mucosa by abnormal luminal contents.

Alternate/Historical Names n n n n Chemical gastropathy Environmental gastritis / gastropathy Reactive gastritis Type C gastritis Some names based on specific causes Bile reflux gastritis NSAID gastritis

Diagnostic Criteria n n n n Foveolar hyperplasia and expansion Produces corkscrew or serrated appearance of elongated crypts Usually involves antrum May involve body if post-antrectomy Regenerative changes in foveolar cells Enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei Prominent nucleoli

n n n Decreased cytoplasmic mucin Parietal cells preserved in glands Minimal to absent neutrophilic and lymphocytic inflammation Acute inflammation without chronic occasionally seen May be difficult to sort out if complicated by Helicobacter Eosinophils may be present

n n n n n Edema Congestion Muscle fibers may be seen in the lamina propria Scant inflammation Similar to ischemic injury May form erosions and ulcers Inflammation restricted to the ulcer Surrounding mucosa has little or no inflammation Hemorrhage and necrosis of superficial mucosa may be seen Frequently linear and antral