Chlorination of Benzene Benzene reacts with halogens salt

�Chlorination of Benzene �Benzene reacts with halogens (salt former) like chlorine and bromine and these reactions are called electrophilic substitution reaction in the presence of catalyst of Lewis acid like aluminum chloride, sulfur dichloride, ferric chloride or iron. Aluminum bromide is used when benzene reacting bromide. Iron is not a catalyst because it reacts with small amount of chlorine or bromine and form iron (III) chloride Fe. Cl 3 or iron (III) bromide Fe. Br 3.

2 Fe +3 Cl 2 → 2 Fe. Cl 3 2 Fe + 3 Br 2→ 2 Fe. Br 3 Benzene reacts with chlorine in the. presence of aluminum chloride or iron to prepare chlorobenzene. C 6 H 6 + Cl 2 → C 6 H 5 Cl + HCl

� Oxidation reaction � Petroleum feedstocks serve as the primary source (>90 %) of the world's industrial organic chemicals, ranging from pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals to large‐scale commodity products. Petroleum primarily consists of reduced hydrocarbons, and their selective oxidation chemistry remains one of the foremost challenges in the chemical industry. This challenge has increased in recent decades with the recognition that many of the best selective oxidants, for example, chlorine and transition‐metal oxides, produce environmentally hazardous by‐products. The economic and environmental advantages of molecular oxygen as a chemical oxidant are readily apparent; however, uncatalyzed reactions between dioxygen and organic substrates generally result in combustion. �

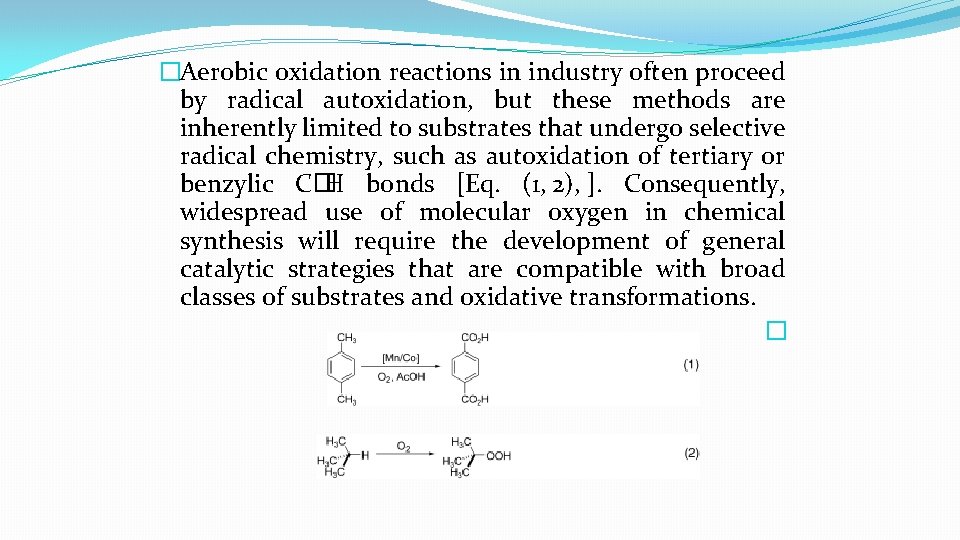

�Aerobic oxidation reactions in industry often proceed by radical autoxidation, but these methods are inherently limited to substrates that undergo selective radical chemistry, such as autoxidation of tertiary or benzylic C� H bonds [Eq. (1, 2), ]. Consequently, widespread use of molecular oxygen in chemical synthesis will require the development of general catalytic strategies that are compatible with broad classes of substrates and oxidative transformations. �

�Metalloenzymes that catalyze selective aerobic oxidation reactions provide an important framework for the design of new catalysts, and the contributions of numerous groups within the biological and chemical communities have provided much insight into the activation and use of molecular oxygen in selective oxidation. Two distinct classes of such enzymes have been characterized, oxygenases and oxidases, which differ with respect to the fate of the oxygen atoms from dioxygen (Scheme 1). Oxygenases effect oxygen‐atom transfer from dioxygen to the substrate (Scheme 1 a), whereas oxidases simply use molecular oxygen as an electron/proton acceptor in substrate oxidation. In the latter case, the oxygen atoms are released as water or hydrogen peroxide (Scheme 1 b). This mechanistic distinction has important implications for the development of new aerobic oxidation methods.

![�Several palladium‐catalyzed transformations fit this reactivity pattern, most notably the Wacker process [Eq. (3)], �Several palladium‐catalyzed transformations fit this reactivity pattern, most notably the Wacker process [Eq. (3)],](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/2b8ee45e0eb4a43c2db9d661af336fa8/image-6.jpg)

�Several palladium‐catalyzed transformations fit this reactivity pattern, most notably the Wacker process [Eq. (3)], which has been used in industry for more than 40 years. 4 Although the stoichiometry of this reaction appears to reflect oxygen‐atom transfer, water supplies the oxygen atom in the acetaldehyde product and dioxygen simply regenerates the palladium(II) catalyst through the intermediacy of a copper cocatalyst (Scheme 2). Despite this well‐established precedent, the diversity of palladium‐catalyzed oxidation reactions that undergo efficient dioxygen‐coupled turnover has been relatively limited.

- Slides: 6