Children and Young Peoples Programme in Suicide Postvention

- Slides: 37

Children and Young People’s Programme in Suicide Postvention Contexts Professor Anne Graham Southern Cross University

“Never see a need without trying to do something about it. ” St Mary of the Cross Mac. Killop

Why are we here? To explore the potential contribution of the Seasons for Growth programme within the specific context of suicide ‘postvention’ work.

Workshop objectives To review evidence about suicide postvention and the importance of addressing young people’s experience of loss and grief over the longer term To explore key issues to keep in mind when providing the Seasons for Growth programme in suicide postvention contexts.

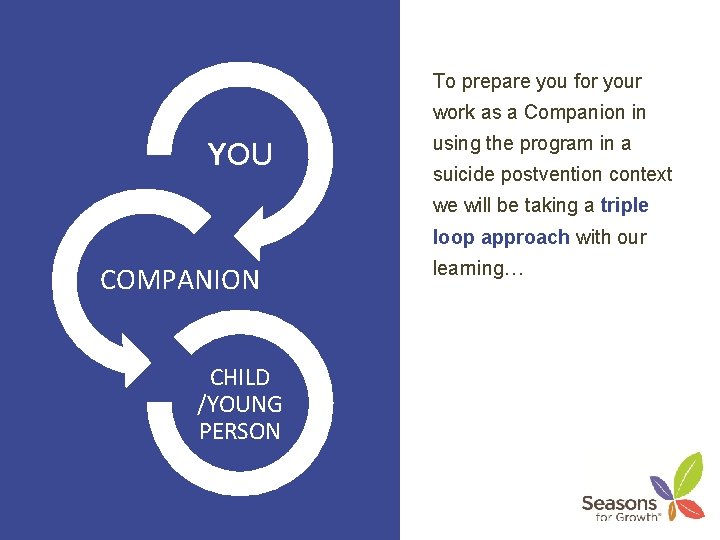

To prepare you for your work as a Companion in YOU using the program in a suicide postvention context we will be taking a triple loop approach with our COMPANION CHILD /YOUNG PERSON learning…

Suicide and young people Australia accounts for more than 24% of all male deaths and 15% of all female deaths in the 15 - to 24 -year age group compared to 1. 6% of deaths among all age groups. “This means there is a disproportionate representation of suicide in an age group that should reflect the best and most productive years of health and quality of life” (Bartik et al. , 2013).

Suicide and young people New Zealand In 2017, New Zealand had the highest reported youth suicide rate of OECD countries (UNICEF, 2017) While some countries may under-report, the rate remains almost 5 x higher than the UK for example Rates are particularly high for males, particularly males of Maori descent (Stats NZ, 2017)

Suicide amongst young people Scotland In comparison to Australia and NZ, Scotland does not have such a high youth suicide rate Youth suicide rates are also lower than that of older age groups - highest rates of suicide in Scotland are amongst men aged 40 – 44 years However, suicide remains the leading cause of death for young people aged 15 -34 years Suicide rates are also higher in Scotland than in England Links identified between suicide and poverty, deprivation, poor mental health and difficult relationships (Information Services Division Scotland, 2014; National Records of Scotland, 2016; Samaritans, 2017)

Peers bereaved by suicide Considerable literature exploring risk factors and mental health of young people who suicide Much less research about the experience of peers bereaved by suicide

What is suicide postvention? Schneidman (1981) coined the term ‘postvention’ which is aimed at: Reducing contagion Supporting students and the wider school community in grieving the loss Postvention encompasses notions of both initial crisis response as well as longer-term support

Suicide clusters are rare But highest incidences amongst those under 24 years Young people may overestimate the suicide attempts of friends – this misperception influences own suicide attempts Subsequent suicides in young people with preexisting psychosocial problems, but their suicides are considered preventable (Abbott & Zakriski, 2014; Andriessen et al. , 2016; Bell et al. , 2015; Hacker et al. , 2008; Ho et al. , 2000; Zimmerman et al. , 2016)

Postvention frameworks Major emphasis in the 1990 s on postvention frameworks and guidance for schools - drawing attention to the importance of issues such as: 1) Informing all staff 2) Liaising with the deceased student’s family 3) Informing the student community (in accordance with the wishes of the family) 4) Setting up designated support spaces 5) Informing all parents and providing information 6) Monitoring students who may need additional support (see Grossman et al. , 1995; Hazell, 1991; King, 1999; Mauk & Weber, 1991; Roberts, Lepkowski, & Davidson, 1998; Wenckstern & Leenaars, 1991)

Since then increase in social media has changed the landscape around postvention: u Conduit for the rapid spread of information prior to school’s initial postvention response u Rapid spread of false or misleading information u Memorial pages that can glorify the deceased and are difficult for schools to regulate u Grief occurs in an adolescent dominated environment (Abraham, Zebib & Sher, 2017; Heffel et al. , 2015; Robertson et al. , 2012)

Postvention Guidelines Excellent crisis response guidelines now widely adopted: Suicide Postvention Guidelines’ (2010) from the Department of Education and Children’s Services in South Australia Headspace’s Suicide Postvention Toolkit (Australia) (2012) Samaritans ‘Step by Step’ program (Scotland)

Postvention Guidelines - NZ : Ministry of Education: Preventing and responding to suicide: Resource kit for schools (2013) Youthline: Best practice strategies for Postvention (2014)

Longer term support “The team of staff with direct responsibility to support students at risk will by now have an identified group of young people who will be receiving ongoing support and monitoring in partnership with mental health professionals and parents. The management of this group of students should be conducted as part of the school’s ongoing and multi-layered systems of student support” (Headspace, 2012, p. 24).

Grief and loss Although postvention has dual aims, the majority of the guidance and support focuses on the immediate and shorterterm issues Passing reference only to longer term loss and grief Little guidance beyond the first month of crisis intervention Little detailed insight into what students, parents and teachers might need to understand (knowledge) and do (skills) to attend to longer-term grief as result of suicide

Adolescent grief may be more intense and chronic than anticipated (Balk et al 2011) Loss of a friend may be particularly accentuated because of developmental shifts away from family towards greater reliance on peers The loss of a friend is a ‘non-normative life crisis’ (Balk et al, 2011) May be first experience of death

Adolescent grief Grieving adolescents describe: Sleep problems and exhaustion Difficulties eating Headaches Crying uncontrollably and without warning Persistent yearning Numbness Preoccupation with the deceased Engagement in risky behaviours Withdrawal from social networks (Balk et al. , 2011; Melhem et al. , 2004 a; Parrish & Tunkle, 2005; The Dougy Center: The National Center for Grieving Children & Families, n. d. ).

Bereaved adolescents may show: u Decline in academic performance u Difficulties concentrating and mastering new material u Difficulties in making decisions (Balk et al. , 2011) u In addition to pastoral support, the US National Center for School Crisis and Bereavement (2008) recommends that schools offer students additional academic support and mentorship to prevent academic failure, which could act as an additional stressor.

“Most children and teens are ‘in and out’ of their grief. They experience sadness, anger and fear, but also are able to have fun and engage in activities. This is a normal grief response. Prolonged or chronic depression, anger, withdrawal or fear over a period of several months may indicate that the student needs professional help in dealing with loss” (The Dougy Center, n. d. , p. 9).

Grief following suicide Clinicians and researchers debate whether grief following suicide is different from other forms of sudden death. Those bereaved by suicide tend to: Struggle more with questions of meaning making - making sense of the motives and frame of mind of the deceased. (“Why did they do it? ”) Feel much higher levels of guilt, blame and responsibility for the death (“Why didn’t I prevent it? ”) Experience heightened feelings of rejection or abandonment, along with anger towards the deceased (“How could they do this to me/others? ”) Experience stigma or assume ‘self-stigmatisation’ – potentially leading to increased shame and withdrawal from social networks. (Andriessen et al. , 2016; Jordan, 2001; Cerel et al, 1999)

Those students at particular risk of traumatic or complicated grief tend to be: u u u Those who spoke to the victim in the 24 hours prior to the suicide Who have a history of depression among their first-degree relatives Who have other interpersonal conflict in their lives (Melhem et al, 2004 b)

Related research suggests that the close friends of those who commit suicide may need support as they may be more likely to engage in risky behaviours and also be experiencing mental health problems (Ho et al, 2000; Melhem et al, 2004 a)

Grief in the peer group Social support generally helps foster more hopeful attitudes But, peer social support can sometimes prolong grief amongst those closest to the deceased (Abbott & Zakriski, 2014) Young people can avoid adult contact due to perceptions of stigma and problems can remain in the peer group (Bartik et al. , 2015) Literature advocates peer groups may benefit from group therapy or education on how to avoid ‘co-rumination’ while supporting one another to process grief (Abbott & Zakriski, 2014)

Connecting to Seasons for Growth Headspace approached Good Grief about adapting the Seasons for Growth program for the context of suicide postvention in schools Seasons for Growth focuses on helping young people understand that change, loss and grief are part of life The theory underpinning the program assumes young people are capable as well as vulnerable – shifting from being a passive victim to an active agent

Seasons for Growth provides the opportunity for young people to acquire knowledge, skills and attitudes that can help them to adapt to change, loss and grief in their lives. Is based on evidence that highlights the significance of both adult ‘scaffolding’ and like-to-like peer support in understanding and managing change, loss and grief

In other words… Can the Seasons for Growth program help to fill a gap (in the postvention context) by supporting young people to understand cope with the experience of loss and grief over the longer term?

Over to you… What has been your experience of suicide postvention work in schools/elsewhere? What do you think was of most help to friends, classmates, teachers, others in the immediate period? What about longer term support?

Over to you… Based on the evidence we’ve outlined today: What key issues might we need to keep in mind when offering the Seasons for Growth programme in suicide postvention contexts?

Considering the context of suicide postvention All participants may be seeking support related to the same issue, and in the same timeframe This potentially changes the dynamic of the group and opportunity to learn from others’ experiences Risk of becoming fixated on issues related to the event rather than the educational process – Companions may have to be additionally conscious to keep the focus on the learning process Consideration needs to given to who the Companion is – are they grieving too as part of the school community? Participation should continue to be voluntary and small group (not whole class)

References Abbott, C. H. , & Zakriski, A. L. (2014). Grief and attitudes toward suicide in peers affected by a cluster of suicides as adolescents. Suicide and Life. Threatening Behavior, 44(6), 668 -681. url: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1111/sltb. 12100 Abraham Zebib, K. , & Sher, L. (2017). Adolescent suicide as a global public health issue. Retrieved from https: //www. degruyter. com/view/j/ijamh. aheadof-print/ijamh-2017 -0036. xml Andriessen, K. , Draper, B. , Dudley, M. , & Mitchell, P. B. (2016). Pre- and postloss features of adolescent suicide bereavement: A systematic review. Death Studies, 40(4), 229 -246. url: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1080/07481187. 2015. 1128497 Balk, D. E. , Zaengle, D. , & Corr, C. A. (2011). Strengthening grief support for adolescents coping with a peer’s death. School Psychology International, 32(2), 144 -162. Bartik, W. , Maple, M. , Edwards, H. , & Kiernan, M. (2013). The psychological impact of losing a friend to suicide. Australasian Psychiatry, 21(6), 545 -549.

References Bartik, W. , Maple, M. , & Mc. Kay, K. (2015). Suicide bereavement and stigma for young people in rural Australia: A mixed methods study. Advances in Mental Health, 13(1), 84 -95. url: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1080/18374905. 2015. 1026301 Bell, J. , Stanley, N. , Mallon, S. , & Manthorpe, J. (2012). Life will never be the same again: Examining grief in survivors bereaved by young suicide. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 20(1), 49 -68. url: http: //icl. sagepub. com/content/20/1/49. abstract Cerel, J. , Fristad, M. A. , Weller, E. B. , & Weller, R. A. (1999). Suicide‐bereaved children and adolescents: A controlled longitudinal examination. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(6), 672 -679. Department of Education and Children's Services, Catholic Education SA, & Association of Independent Schools of SA. (2010). Suicide postvention guidelines: A framework to assist staff in supporting their school communities in responding to suspected, attempted or completed suicide. Adelaide: Government of South Australia.

References Grossman, J. , Hirsch, J. , Goldenberg, D. , Libby, S. , Fendrich, M. , Mackesy-Amiti, M. E. , . . . Chance, G. -H. (1995). Strategies for school-based response to loss: Proactive training and postvention consultation. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 16(1), 18 -26. Hacker, K. , Collins, J. , Gross-Young, L. , Almeida, S. , & Burke, N. (2008). Coping with youth suicide and overdose. Crisis, 29(2), 86 -95. url: http: //econtent. hogrefe. com/doi/abs/10. 1027/0227 -5910. 29. 2. 86 Hazell, P. (1991). Postvention after teenage suicide: An Australian experience. Journal of Adolescence, 14(4), 335 -342. Headspace. (2012). Suicide postvention toolkit: A guide for secondary schools. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Aging. Hendren, R. , Birrell Weisen, R. & Orley, J. (1994). Health Programs in Schools. Geneva: World Health Organisation Ho, T. -p. , Leung, P. W. -l. , Hung, S. -f. , Lee, C. -c. , & Tang, C. -p. (2000). The mental health of the peers of suicide completers and attempters. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 41(03), 301 -308. Information Services Division Scotland. (2015). Suicide Statistics for Scotland. https: //www. isdscotland. org/Health-Topics/Public-Health/Publications/2015 -08 -20/2015 -0820 -Suicide-Summary. pdf? 6515139342 Jordan, J. R. (2001). Is suicide bereavement different? A reassessment of the literature. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 31(1), 91 -102.

References Mauk, G. W. , & Weber, C. (1991). Peer survivors of adolescent suicide: Perspectives on grieving and postvention. Journal of Adolescent Research, 6(1), 113 -131. Melhem, N. M. , Day, N. , Shear, M. K. , Day, R. , Reynolds, C. F. , & Brent, D. (2004 a). Predictors of complicated grief among adolescents exposed to a peer's suicide. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 9(1), 21 -34. doi: 10. 1080/1532502490255287 Melhem, N. M. , Day, N. , Shear, M. K. , Day, R. , Reynolds, C. F. , & Brent, D. (2004 b). Traumatic grief among adolescents exposed to a peer's suicide. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(8), 1411 -1416. Muller, D. , & Saulwick, I. (1999). An evaluation of the Seasons for Growth program: Consolidated report. Canberra: Department of Health and Aged Care. Robertson, L. , Skegg, K. , Poore, M. , Williams, S. , & Taylor, B. (2012). An adolescent suicide cluster and the possible role of electronic communication technology. Crisis, 33(4), 239 -245. url: http: //econtent. hogrefe. com/doi/abs/10. 1027/0227 -5910/a 000140 National Center for School Crisis & Bereavement. (2008). Guidelines for responding to the death of a student or schoo staff. Retrieved from http: //www. cincinnatichildrens. org/assets/0/78/1067/4357/4389/2 fa 07 dc 5 -0 e 85 -4495 -aa 9 c 2 b 31 fd 837 ba 1. pdf National Records of Scotland. (2016). Probable Suicides. https: //www. nrscotland. gov. uk/statistics-and-data/statistics-by-theme/vitalevents/deaths/suicides/main-points

References Parrish, M. , & Tunkle, J. (2005). Clinical challenges following an adolescent’s death by suicide: Bereavement issues faced by family, friends, schools, and clinicians. Clinical Social Work Journal, 33(1), 81 -102. Roberts, R. L. , Lepkowski, W. J. , & Davidson, K. K. (1998). Dealing with the aftermath of a student suicide: A TEAM approach. NASSP Bulletin, 82(597), 53 -59. Samaritans. (2017). Suicide Statistics Report. https: //www. samaritans. org/about-us/our-research/facts-and-figuresabout-suicide Shneidman, E. (1981). Postvention: The care of the bereaved. In E. Shneidman (Ed. ), Suicide thoughts and reflections, 1960 -1980 (pp. 157 -167). New York: Human Sciences Press. Stats NZ / Tatauranga Aoteraroa. (2017). NZSocial Indicators: Suicide. http: //archive. stats. govt. nz/browse_for_stats/snapshots-ofnz/nz-social-indicators/Home/Health/suicide. aspx

References The Dougy Center: The National Center for Grieving Children & Families. (n. d. ). Helping the grieving student: A guide for teachers: A practical guide for dealing with death in your classroom: The National Center for Grieving Children & Families. UNICEF. (2017). Building the future: Children and the sustainable development goals in rich countries. Innocenti Report Card, Florence. Wenckstern, S. , & Leenaars, A. A. (1991). Suicide postvention: A case illustration in a secondary school. In A. A. Leenaars & S. Wenckstern (Eds. ), Suicide Prevention in Schools. New York: Hemisphere. Worden, J. (2008). Grief counselling and grief therapy (4 th edition ed. ). New York: Springer. Zimmerman, G. M. , Rees, C. , Posick, C. , & Zimmerman, L. A. (2016). The power of (Mis)perception: Rethinking suicide contagion in youth friendship networks. Social Science & Medicine, 157, 31 -38. url: http: //www. sciencedirect. com/science/article/pii/S 0277953616301459