Chemical Equilibrium The Equilibrium Condition For all of

Chemical Equilibrium

The Equilibrium Condition • For all of your chemistry career, especially when performing stoichiometry calculations, we assumed that all reactions proceed to completion. • In other words, until one of the reactants ran out.

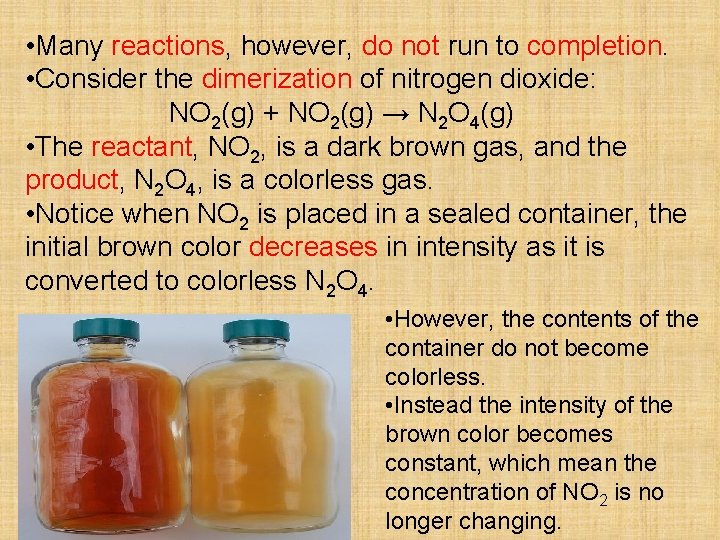

• Many reactions, however, do not run to completion. • Consider the dimerization of nitrogen dioxide: NO 2(g) + NO 2(g) → N 2 O 4(g) • The reactant, NO 2, is a dark brown gas, and the product, N 2 O 4, is a colorless gas. • Notice when NO 2 is placed in a sealed container, the initial brown color decreases in intensity as it is converted to colorless N 2 O 4. • However, the contents of the container do not become colorless. • Instead the intensity of the brown color becomes constant, which mean the concentration of NO 2 is no longer changing.

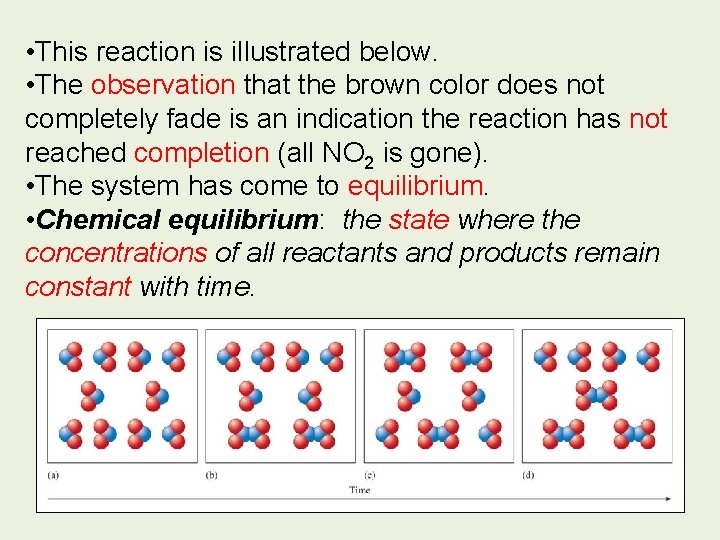

• This reaction is illustrated below. • The observation that the brown color does not completely fade is an indication the reaction has not reached completion (all NO 2 is gone). • The system has come to equilibrium. • Chemical equilibrium: the state where the concentrations of all reactants and products remain constant with time.

Equilibrium is not static but a highly dynamic condition. • Consider the flow of cars across a bridge connecting tw cities with the traffic flow in both directions even. • There is motion since the cars are moving, but the number of cars in each city is not changing because equal numbers of cars are entering and leaving. • The result is no net change in the car population.

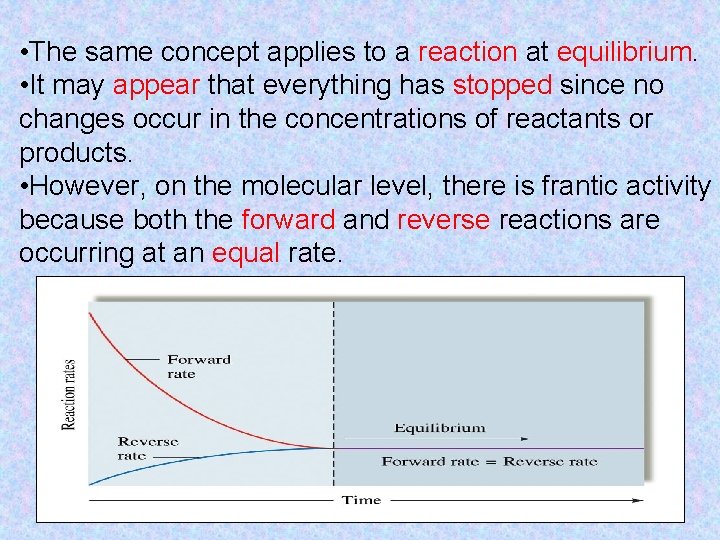

• The same concept applies to a reaction at equilibrium. • It may appear that everything has stopped since no changes occur in the concentrations of reactants or products. • However, on the molecular level, there is frantic activity because both the forward and reverse reactions are occurring at an equal rate.

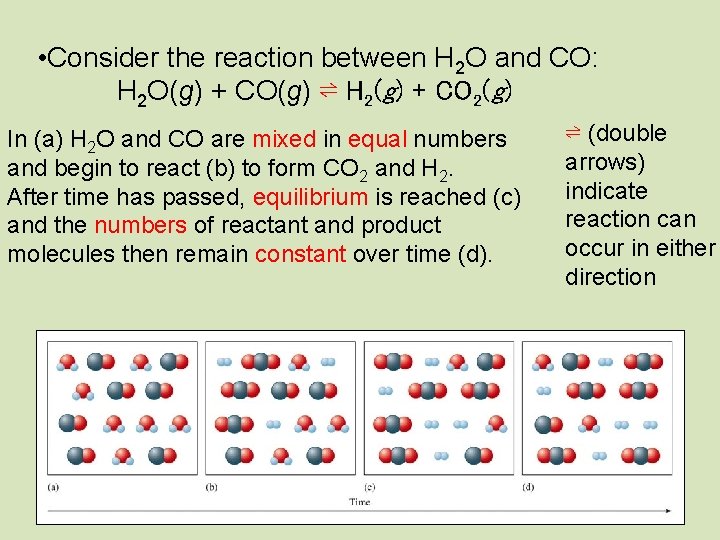

• Consider the reaction between H 2 O and CO: H 2 O(g) + CO(g) ⇌ H 2(g) + CO 2(g) In (a) H 2 O and CO are mixed in equal numbers and begin to react (b) to form CO 2 and H 2. After time has passed, equilibrium is reached (c) and the numbers of reactant and product molecules then remain constant over time (d). ⇌ (double arrows) indicate reaction can occur in either direction

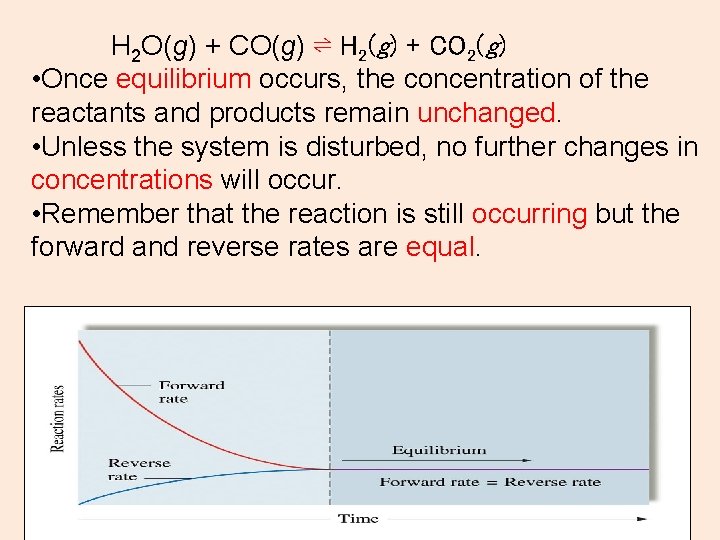

H 2 O(g) + CO(g) ⇌ H 2(g) + CO 2(g) • Once equilibrium occurs, the concentration of the reactants and products remain unchanged. • Unless the system is disturbed, no further changes in concentrations will occur. • Remember that the reaction is still occurring but the forward and reverse rates are equal.

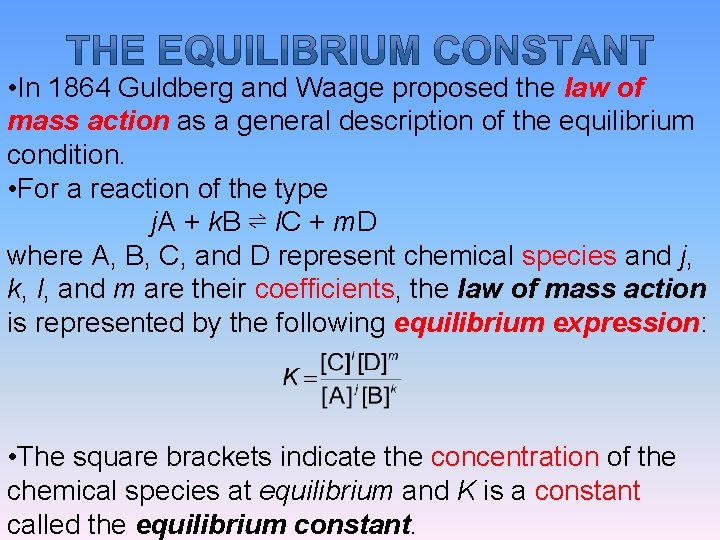

• In 1864 Guldberg and Waage proposed the law of mass action as a general description of the equilibrium condition. • For a reaction of the type j. A + k. B ⇌ l. C + m. D where A, B, C, and D represent chemical species and j, k, l, and m are their coefficients, the law of mass action is represented by the following equilibrium expression: • The square brackets indicate the concentration of the chemical species at equilibrium and K is a constant called the equilibrium constant.

Heterogeneous Equilibria • Homogeneous equilibria: where all reactants and products are in the gaseous phase. • Heterogeneous equilibria: involves more than one phase. • Consider the reaction below: Ca. CO 3(s) ⇌ Ca. O(s) + CO 2(g) • Experimental results show that the position of a heterogeneous equilibrium does not depend on the amounts of pure solids or liquids present.

• Fundamental reason: concentrations of pure solids or liquids present cannot change. • For any pure liquid or solid, the ratio of the amount of substance to volume of substance is a constant. • Therefore the equilibrium expression for Ca. CO 3(s) ⇌ Ca. O(s) + CO 2(g) is written as K = [CO 2]

The Meaning of K • The value of K tells us how far a reaction proceeds to reach equilibrium. • A value of K much larger than 1 means that at equilibrium, the reaction system will consist of mainly products – the equilibrium lies to the right. • For example, consider a general reaction of the type A(g) → B(g) where K = [B]/[A]

• If K for this reaction is 10, 000 (104), then at equilibrium, [B]/[A] = 10, 000 or = [B]/[A] = 10, 000/1 • That is, at equilibrium [B] is 10, 000 times greater than [A]. • Reaction strongly favors the product B, so essentially the reaction goes to completion. • A small value of K means that the system at equilibrium consists largely of reactants – equilibrium lies far to the left.

v. K > 1 → the equilibrium position is far to the right v. K < 1 → the equilibrium position is far to the left

- Slides: 14