CHEM 580 Computational Chemistry Fall 2020 From Schrodinger

- Slides: 41

CHEM 580 Computational Chemistry Fall 2020 From Schrodinger to Hartree. Fock

COURSE OVERVIEW • Objective: Learn to use quantum chemistry for your research • There will be some math – No derivations – No programming • Text: Jensen: Intro to Computational Chemistry 3 rd Ed • Course grade – Mid-term exam (take-home): 40% – Research project (paper): 40% – Class seminar on research project: 20% • Choose project in consultation with major prof & me – The sooner the better: always glitches

COURSE OVERVIEW • Timing – Semester is 1 week shorter than normal – Class time is 5 minutes shorter than normal = 1 week less – Knowledge of point groups will be assumed • Important for GAMESS (and other) input files • Questions in class – Stay muted during lecture – Use chat function in zoom – I will ask for questions regularly

COURSE OVERVIEW • About your research projects – Last two weeks of class will be devoted to your talks – Final paper on project will be due early in week of finals • Paper should be organized as a journal publication • Abstract, intro, methods, results, conclusions • Relevant references – Outline of project due no later than September 17 • Include your thoughts about the project in consultation with your major professor if you have one • Discuss with me if you have not chosen a major prof yet (or even if you have) • We can set up skype/zoom calls to discuss

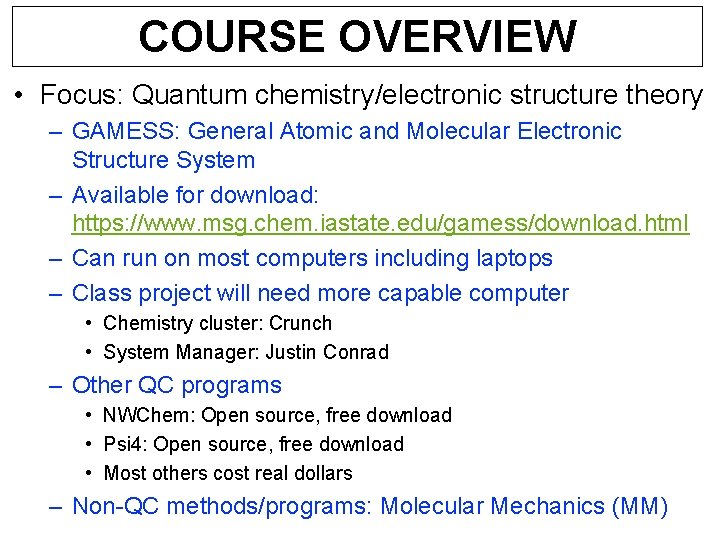

COURSE OVERVIEW • Focus: Quantum chemistry/electronic structure theory – GAMESS: General Atomic and Molecular Electronic Structure System – Available for download: https: //www. msg. chem. iastate. edu/gamess/download. html – Can run on most computers including laptops – Class project will need more capable computer • Chemistry cluster: Crunch • System Manager: Justin Conrad – Other QC programs • NWChem: Open source, free download • Psi 4: Open source, free download • Most others cost real dollars – Non-QC methods/programs: Molecular Mechanics (MM)

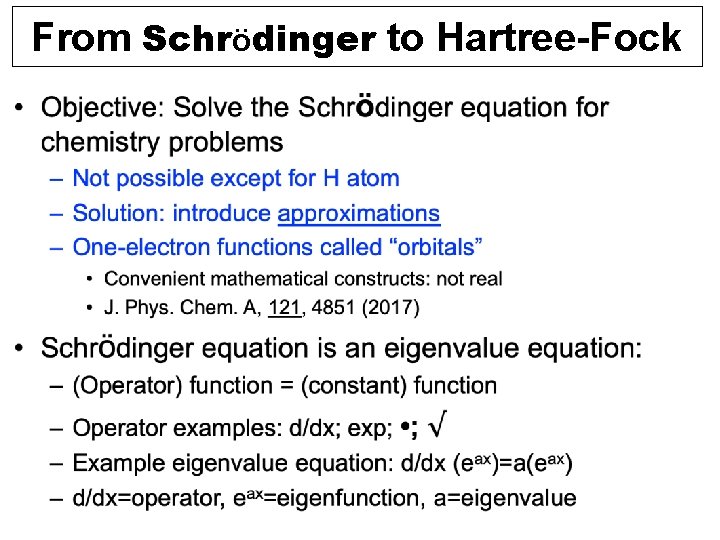

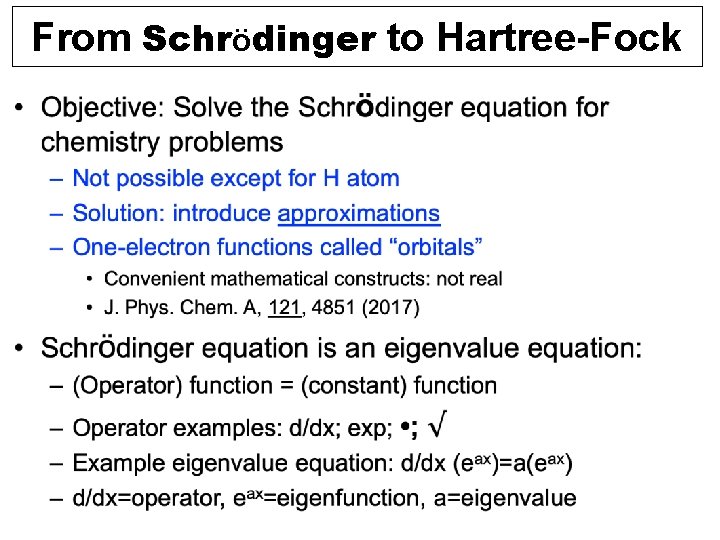

From Schrödinger to Hartree-Fock

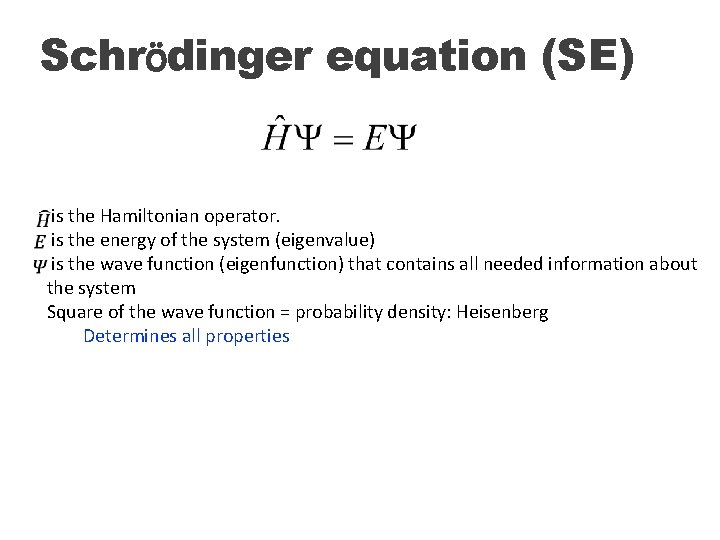

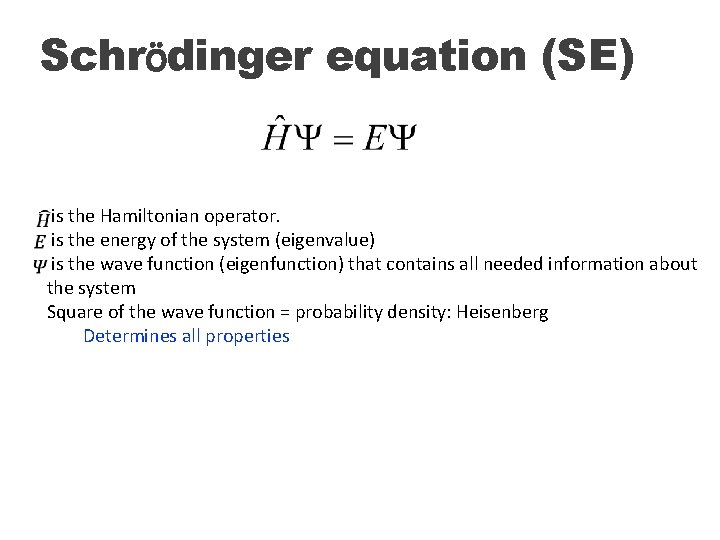

Schrödinger equation (SE) is the Hamiltonian operator. is the energy of the system (eigenvalue) is the wave function (eigenfunction) that contains all needed information about the system Square of the wave function = probability density: Heisenberg Determines all properties

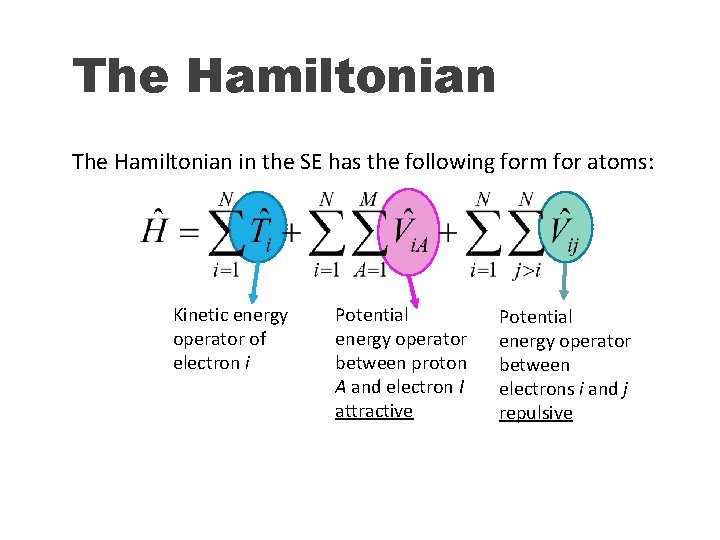

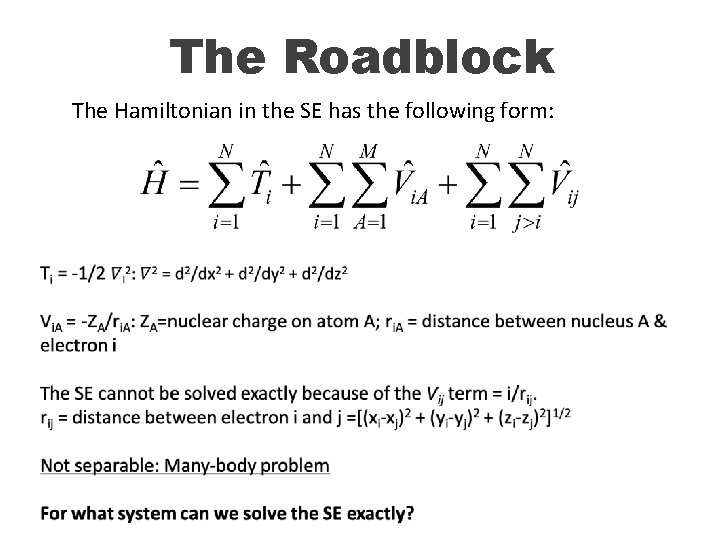

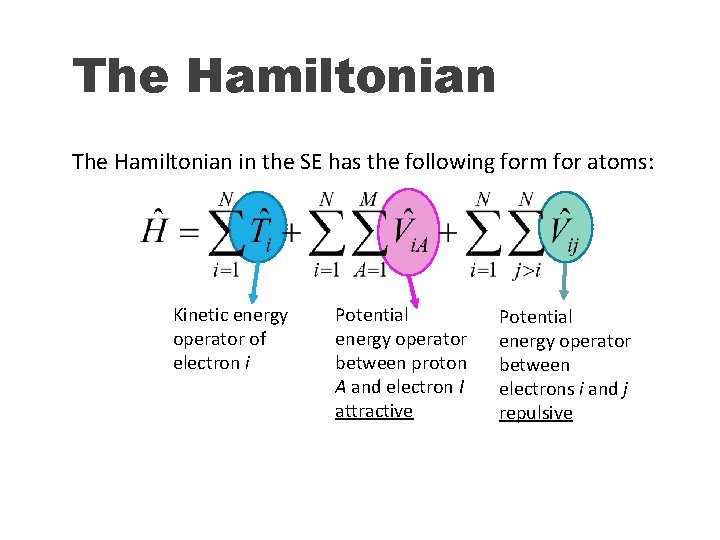

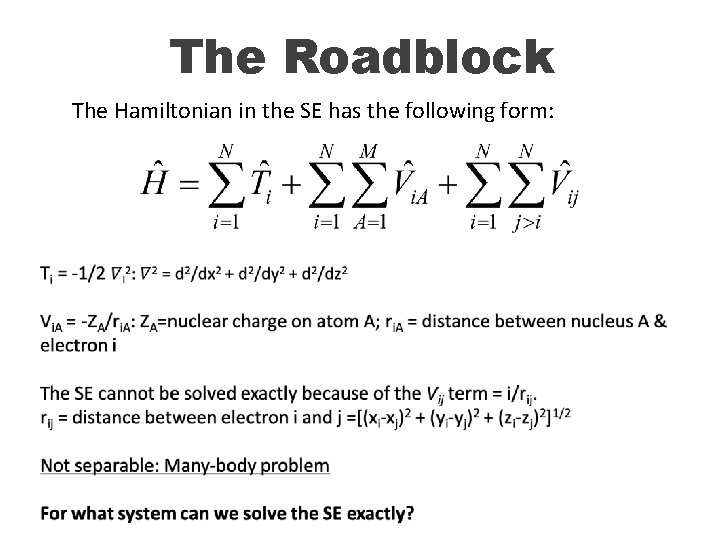

The Hamiltonian in the SE has the following form for atoms: Kinetic energy operator of electron i Potential energy operator between proton A and electron I attractive Potential energy operator between electrons i and j repulsive

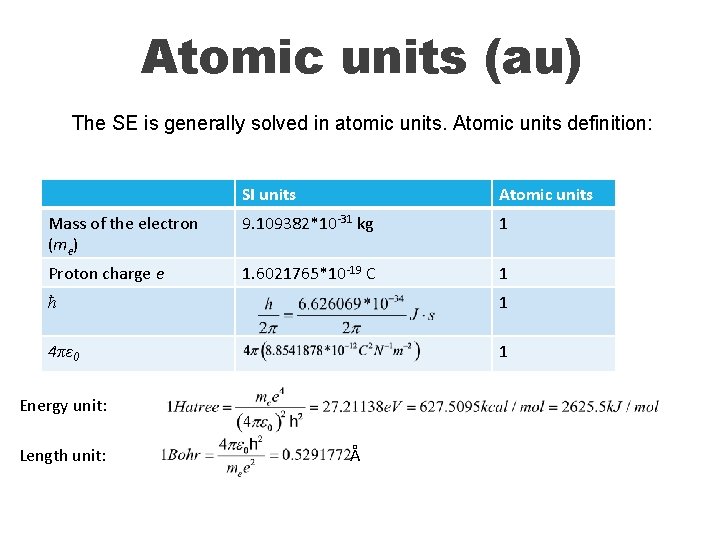

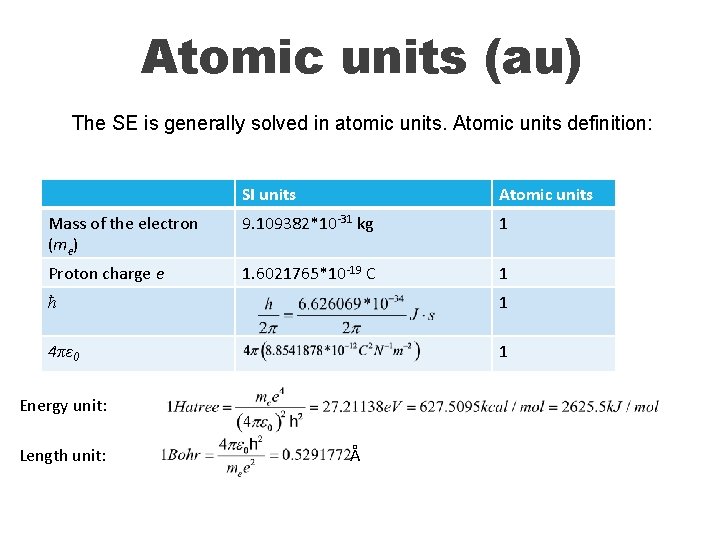

Atomic units (au) The SE is generally solved in atomic units. Atomic units definition: SI units Atomic units Mass of the electron (me) 9. 109382*10 -31 kg 1 Proton charge e 1. 6021765*10 -19 C 1 ћ 1 4πε 0 1 Energy unit: Length unit: Å

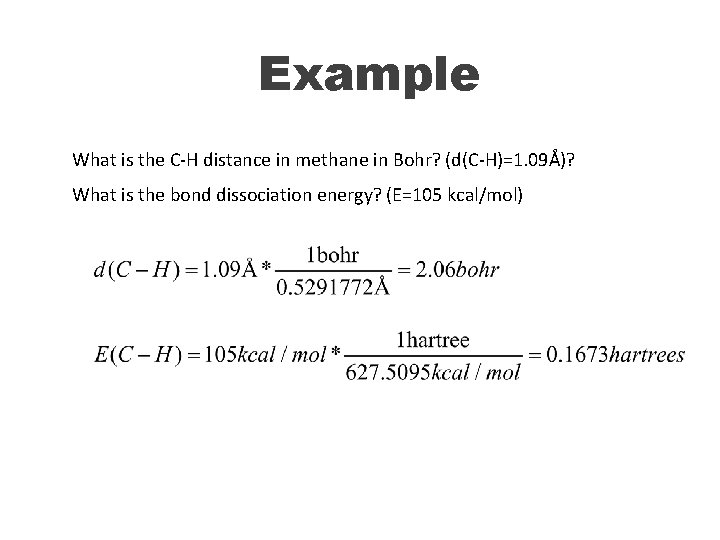

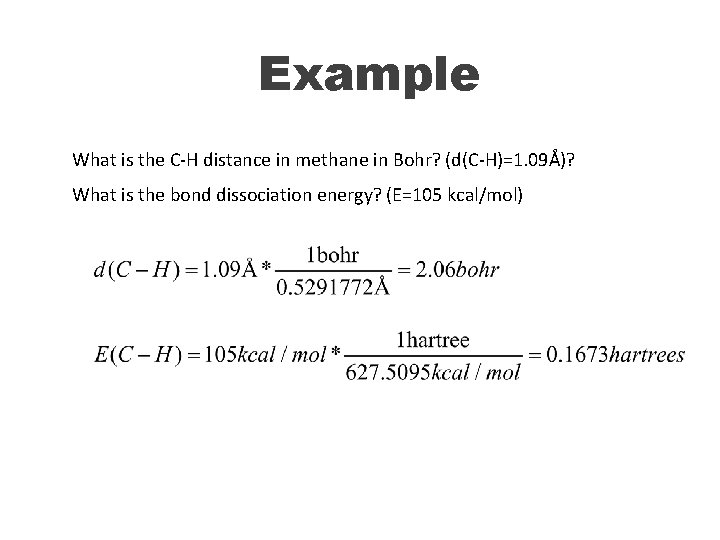

Example What is the C-H distance in methane in Bohr? (d(C-H)=1. 09Å)? What is the bond dissociation energy? (E=105 kcal/mol)

The Roadblock The Hamiltonian in the SE has the following form:

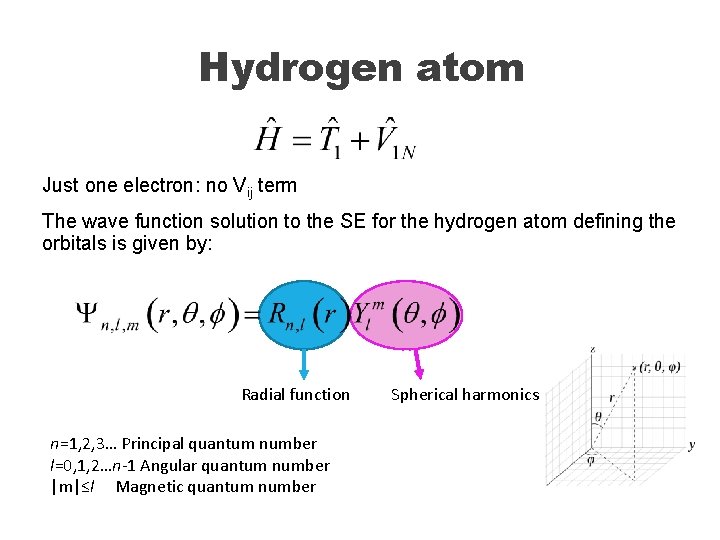

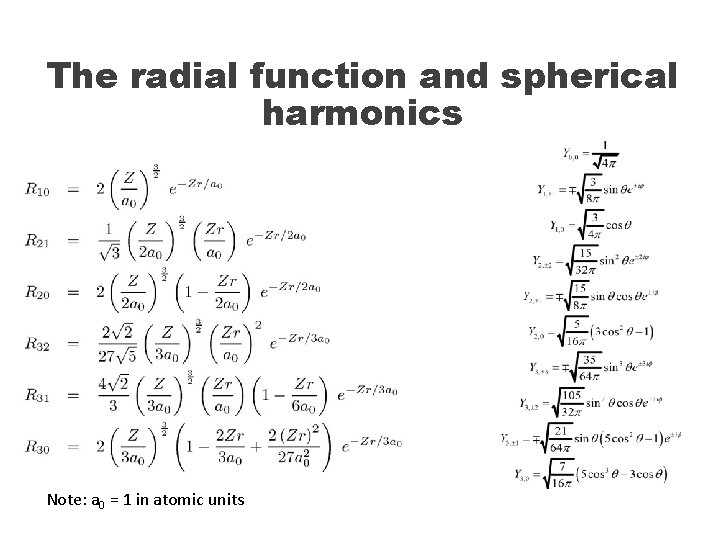

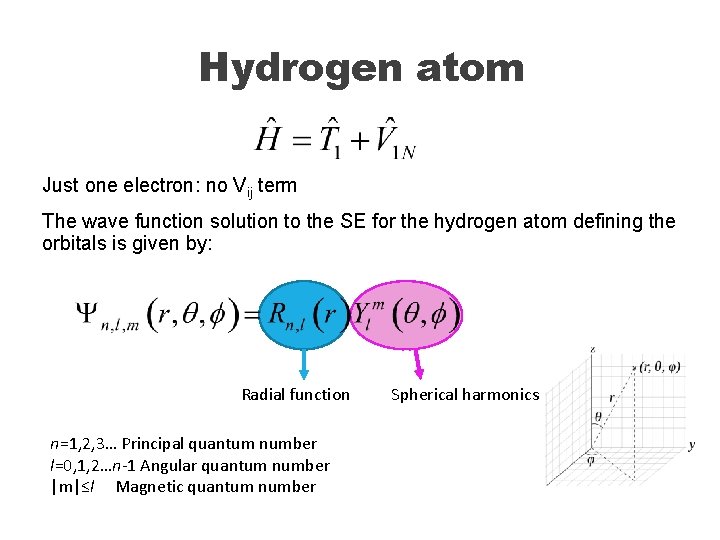

Hydrogen atom Just one electron: no Vij term The wave function solution to the SE for the hydrogen atom defining the orbitals is given by: Radial function n=1, 2, 3… Principal quantum number l=0, 1, 2…n-1 Angular quantum number |m|≤l Magnetic quantum number Spherical harmonics

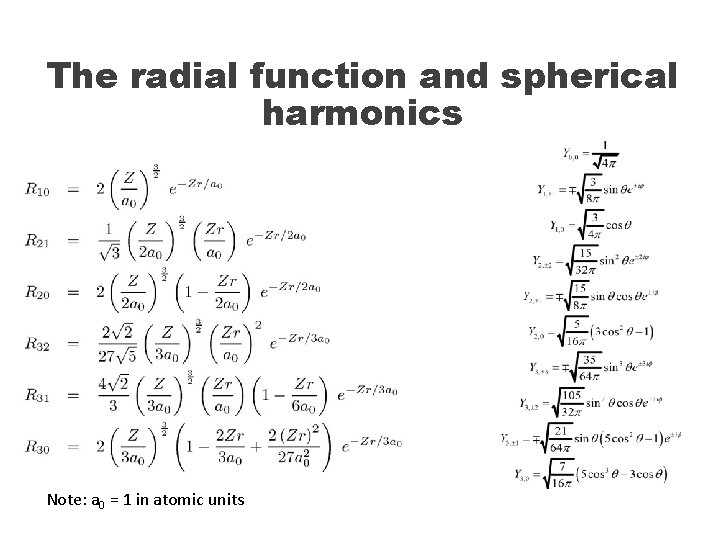

The radial function and spherical harmonics Note: a 0 = 1 in atomic units

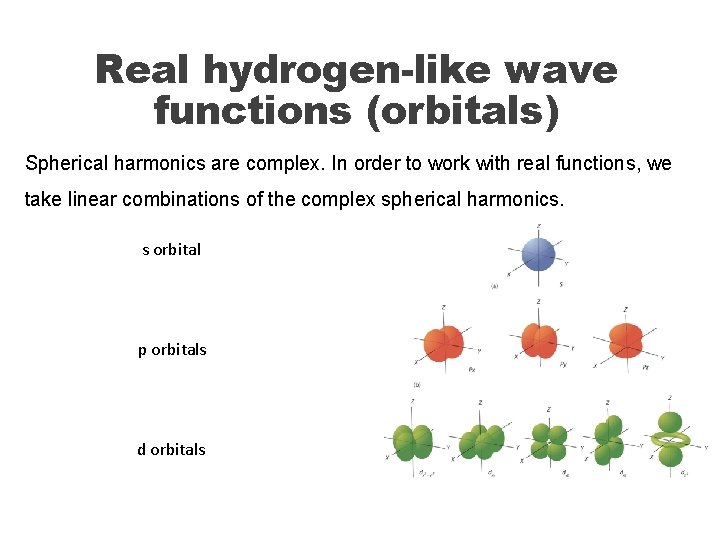

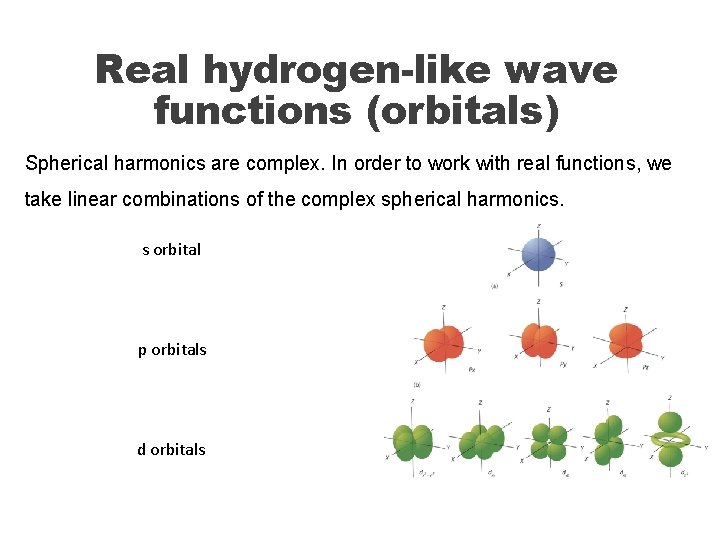

Real hydrogen-like wave functions (orbitals) Spherical harmonics are complex. In order to work with real functions, we take linear combinations of the complex spherical harmonics. s orbital p orbitals d orbitals

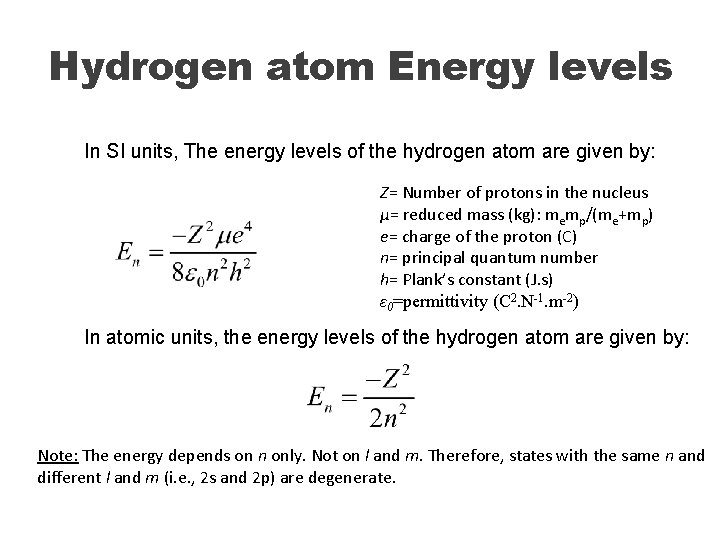

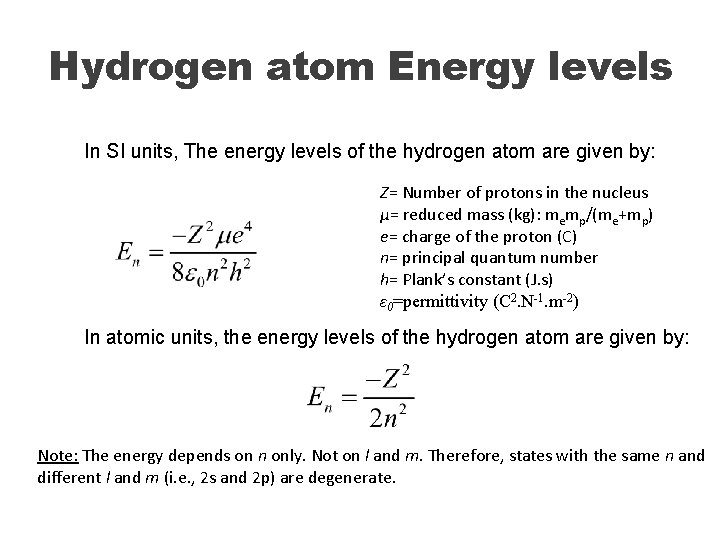

Hydrogen atom Energy levels In SI units, The energy levels of the hydrogen atom are given by: Z= Number of protons in the nucleus µ= reduced mass (kg): memp/(me+mp) e= charge of the proton (C) n= principal quantum number h= Plank’s constant (J. s) ε 0=permittivity (C 2. N-1. m-2) In atomic units, the energy levels of the hydrogen atom are given by: Note: The energy depends on n only. Not on l and m. Therefore, states with the same n and different l and m (i. e. , 2 s and 2 p) are degenerate.

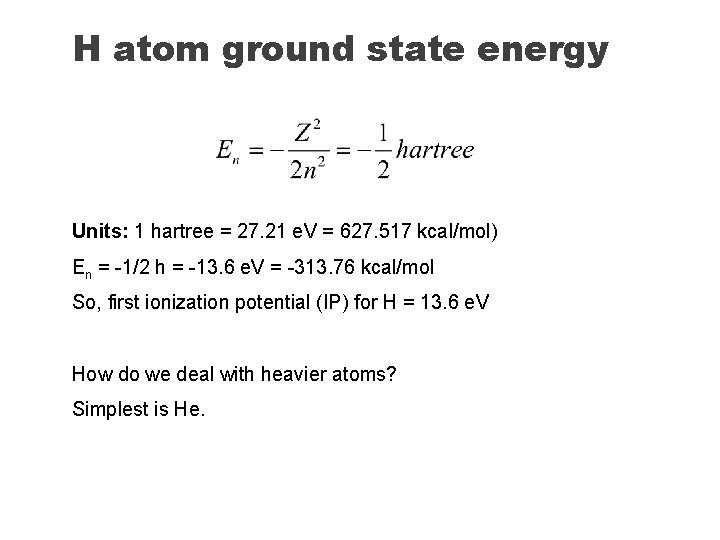

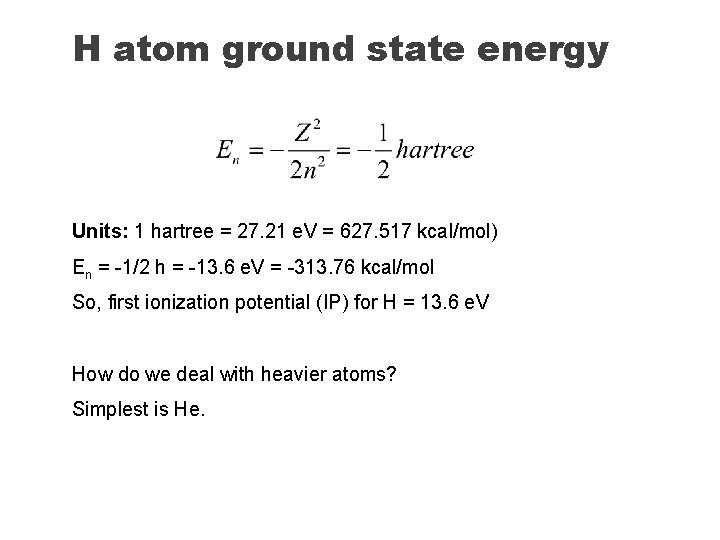

H atom ground state energy Units: 1 hartree = 27. 21 e. V = 627. 517 kcal/mol) En = -1/2 h = -13. 6 e. V = -313. 76 kcal/mol So, first ionization potential (IP) for H = 13. 6 e. V How do we deal with heavier atoms? Simplest is He.

Helium atom N = 2 (electrons) The SE equation cannot be solved exactly due to the electron repulsion [Vij = 1/rij] in the Hamiltonian. Many-body problem. What can we do? 1) Ignore the electron repulsion (independent particle model) The Hamiltonian is the sum of two Hydrogen-like Hamiltonians that we can solve exactly and separately:

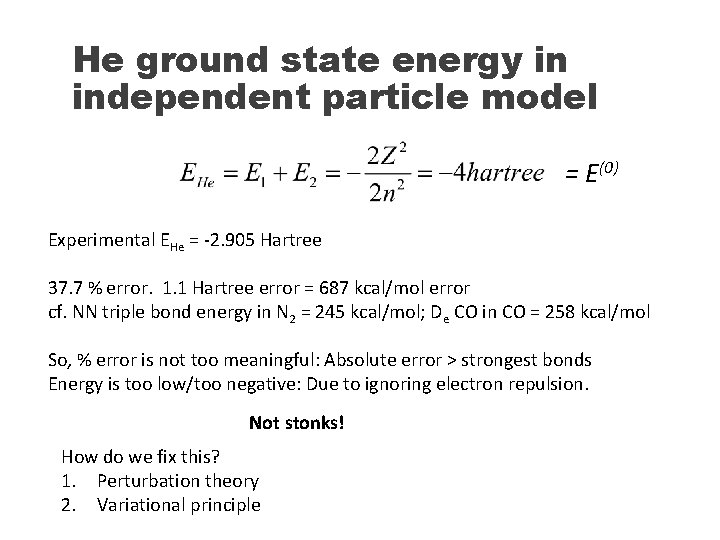

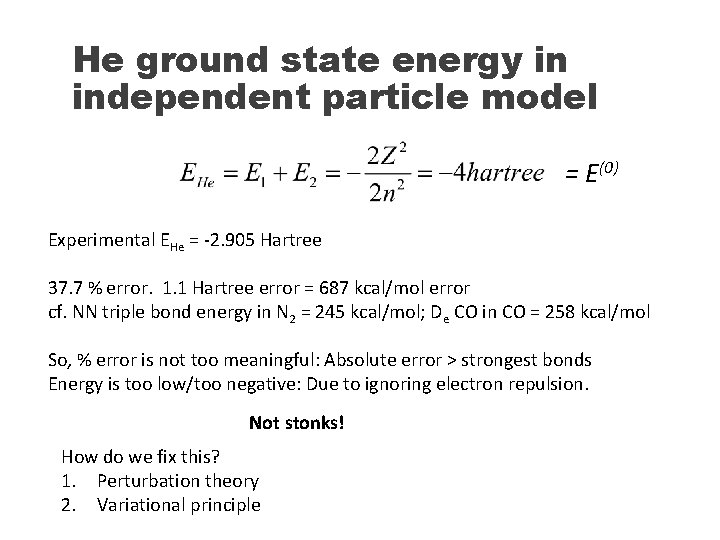

He ground state energy in independent particle model = E(0) Experimental EHe = -2. 905 Hartree 37. 7 % error. 1. 1 Hartree error = 687 kcal/mol error cf. NN triple bond energy in N 2 = 245 kcal/mol; De CO in CO = 258 kcal/mol So, % error is not too meaningful: Absolute error > strongest bonds Energy is too low/too negative: Due to ignoring electron repulsion. Not stonks! How do we fix this? 1. Perturbation theory 2. Variational principle

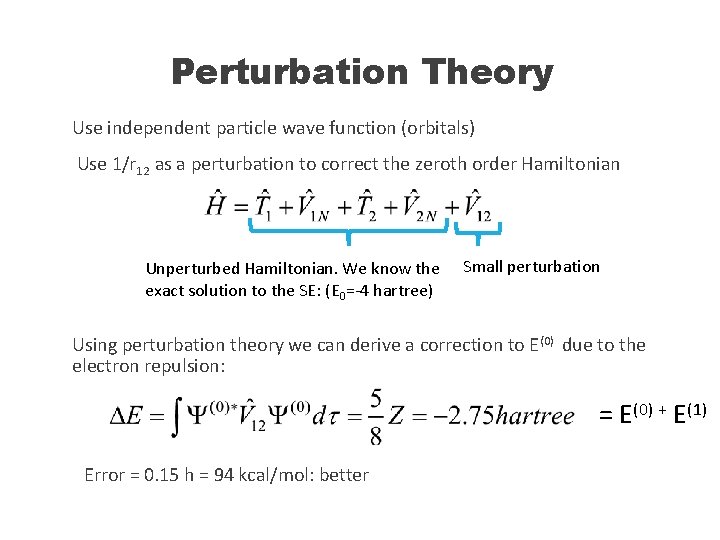

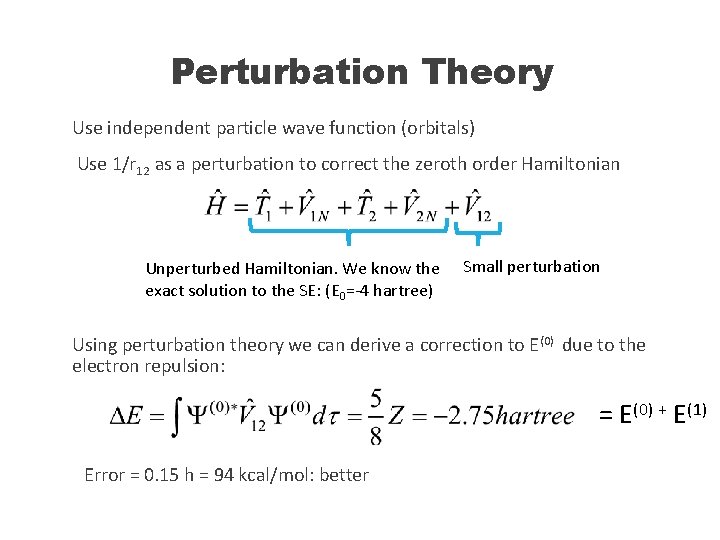

Perturbation Theory Use independent particle wave function (orbitals) Use 1/r 12 as a perturbation to correct the zeroth order Hamiltonian Unperturbed Hamiltonian. We know the exact solution to the SE: (E 0=-4 hartree) Small perturbation Using perturbation theory we can derive a correction to E(0) due to the electron repulsion: = E(0) + E(1) Error = 0. 15 h = 94 kcal/mol: better

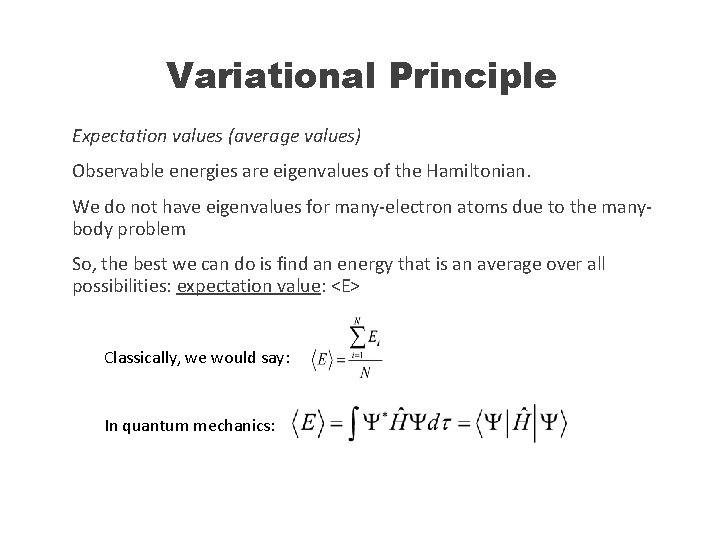

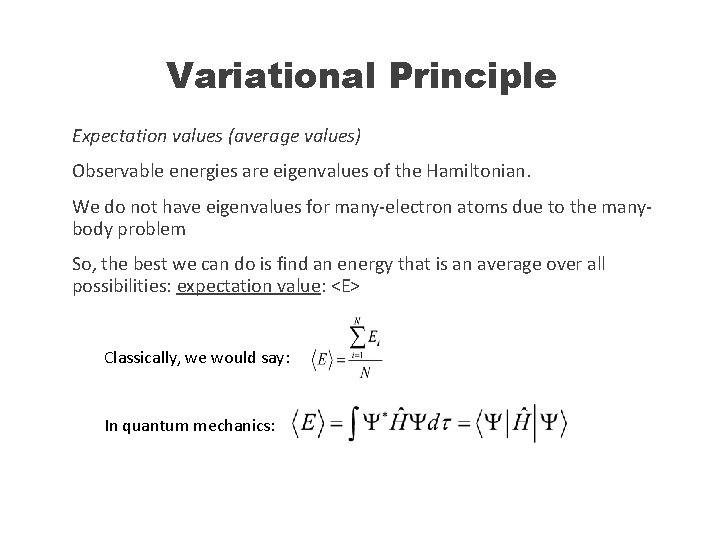

Variational Principle Expectation values (average values) Observable energies are eigenvalues of the Hamiltonian. We do not have eigenvalues for many-electron atoms due to the manybody problem So, the best we can do is find an energy that is an average over all possibilities: expectation value: <E> Classically, we would say: In quantum mechanics:

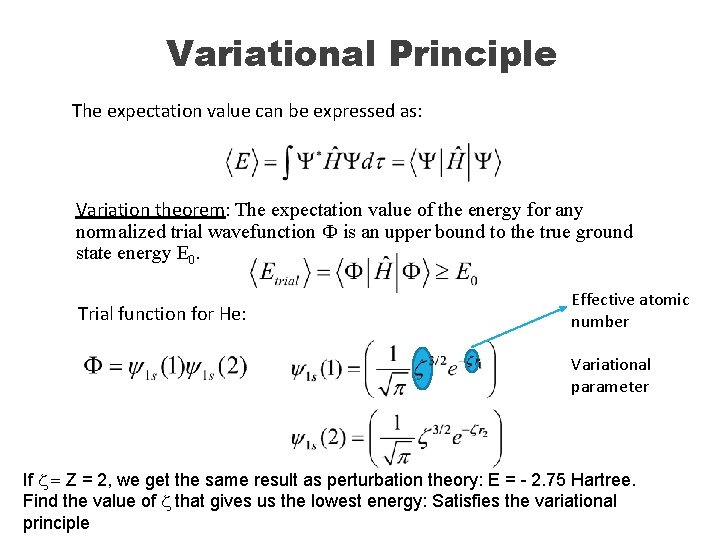

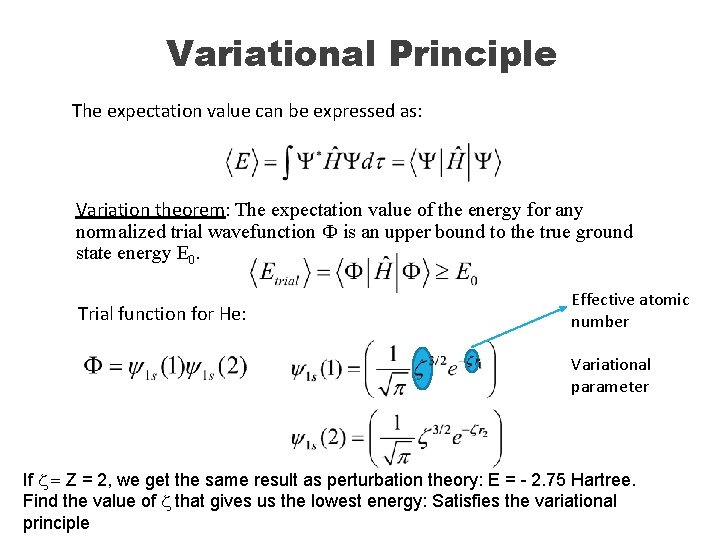

Variational Principle The expectation value can be expressed as: Variation theorem: The expectation value of the energy for any normalized trial wavefunction Ф is an upper bound to the true ground state energy E 0. Trial function for He: Effective atomic number Variational parameter If z = Z = 2, we get the same result as perturbation theory: E = - 2. 75 Hartree. Find the value of z that gives us the lowest energy: Satisfies the variational principle

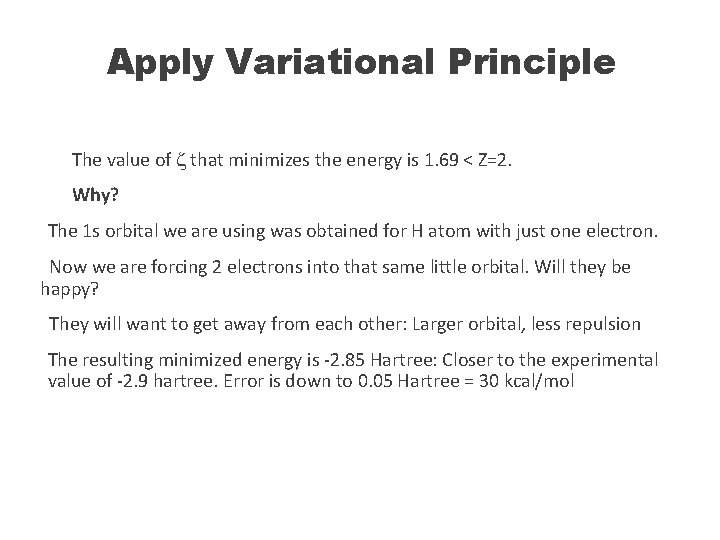

Apply Variational Principle The value of z that minimizes the energy is 1. 69 < Z=2. Why? The 1 s orbital we are using was obtained for H atom with just one electron. Now we are forcing 2 electrons into that same little orbital. Will they be happy? They will want to get away from each other: Larger orbital, less repulsion The resulting minimized energy is -2. 85 Hartree: Closer to the experimental value of -2. 9 hartree. Error is down to 0. 05 Hartree = 30 kcal/mol

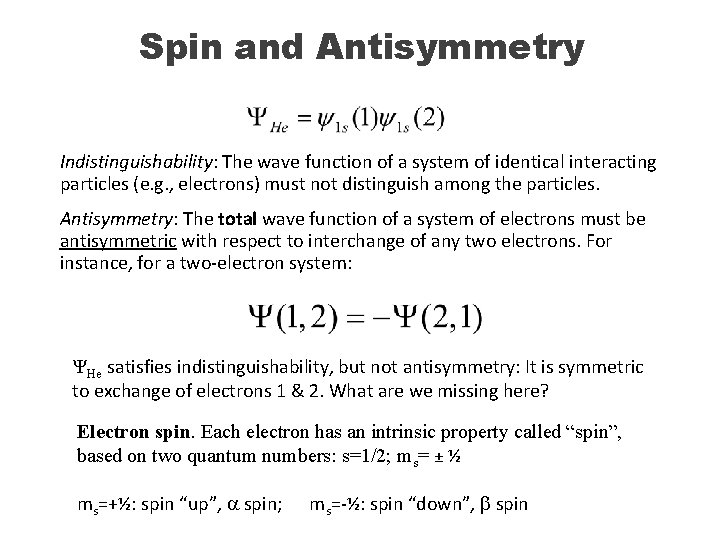

Spin and Antisymmetry Indistinguishability: The wave function of a system of identical interacting particles (e. g. , electrons) must not distinguish among the particles. Antisymmetry: The total wave function of a system of electrons must be antisymmetric with respect to interchange of any two electrons. For instance, for a two-electron system: ΨHe satisfies indistinguishability, but not antisymmetry: It is symmetric to exchange of electrons 1 & 2. What are we missing here? Electron spin. Each electron has an intrinsic property called “spin”, based on two quantum numbers: s=1/2; ms= ± ½ ms=+½: spin “up”, a spin; ms=-½: spin “down”, b spin

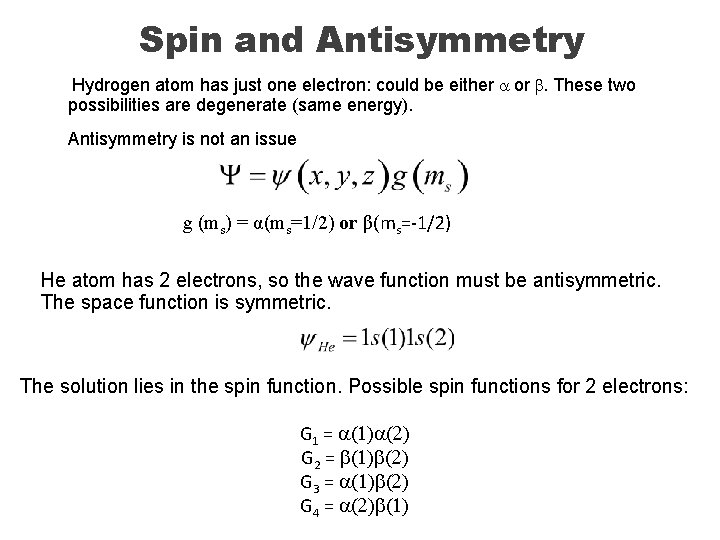

Spin and Antisymmetry Hydrogen atom has just one electron: could be either a or b. These two possibilities are degenerate (same energy). Antisymmetry is not an issue g (ms) = α(ms=1/2) or β(ms=-1/2) He atom has 2 electrons, so the wave function must be antisymmetric. The space function is symmetric. The solution lies in the spin function. Possible spin functions for 2 electrons: G 1 = a(1)a(2) G 2 = b(1)b(2) G 3 = a(1)b(2) G 4 = a(2)b(1)

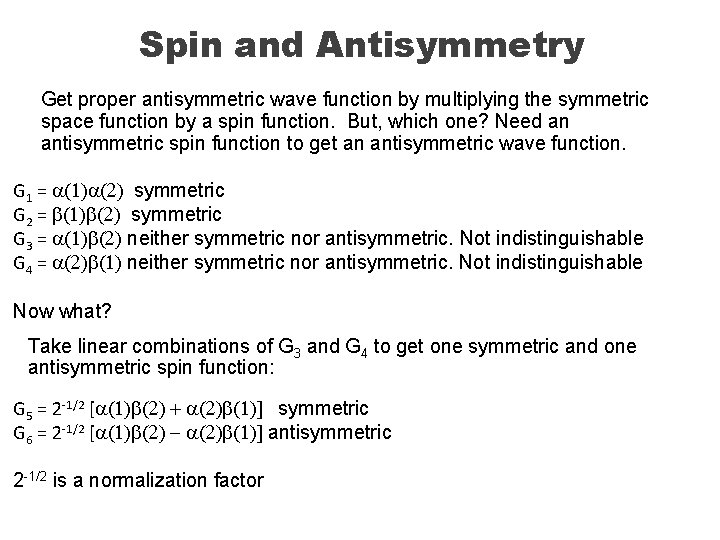

Spin and Antisymmetry Get proper antisymmetric wave function by multiplying the symmetric space function by a spin function. But, which one? Need an antisymmetric spin function to get an antisymmetric wave function. G 1 = a(1)a(2) symmetric G 2 = b(1)b(2) symmetric G 3 = a(1)b(2) neither symmetric nor antisymmetric. Not indistinguishable G 4 = a(2)b(1) neither symmetric nor antisymmetric. Not indistinguishable Now what? Take linear combinations of G 3 and G 4 to get one symmetric and one antisymmetric spin function: G 5 = 2 -1/2 [a(1)b(2) + a(2)b(1)] symmetric G 6 = 2 -1/2 [a(1)b(2) - a(2)b(1)] antisymmetric 2 -1/2 is a normalization factor

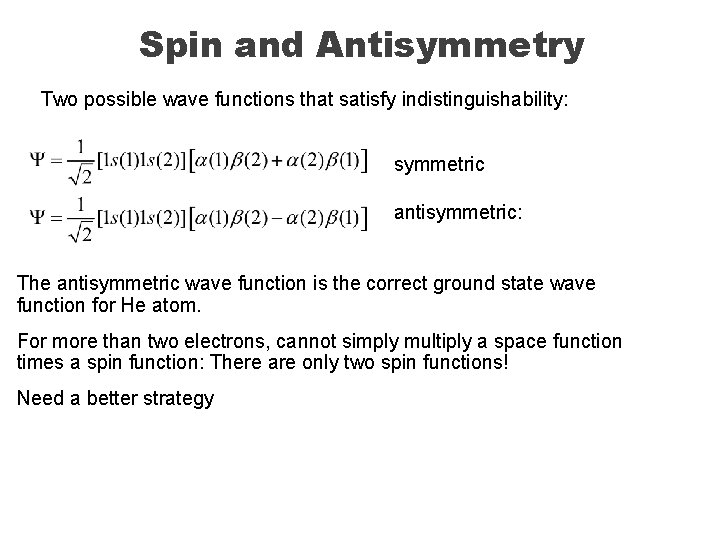

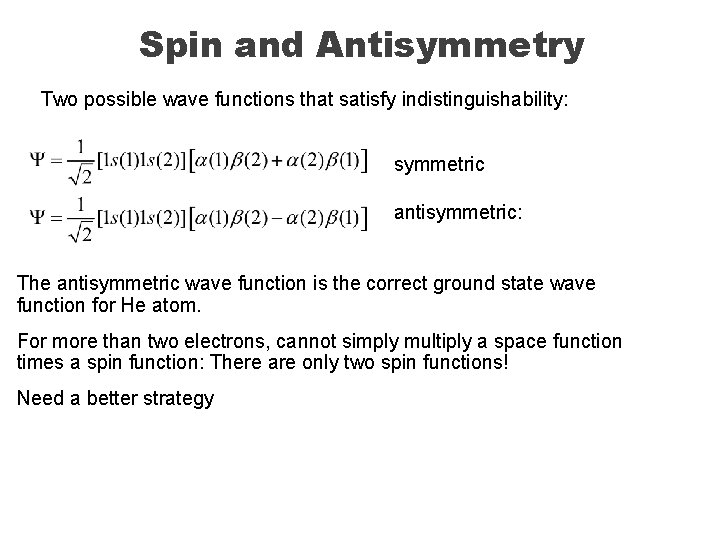

Spin and Antisymmetry Two possible wave functions that satisfy indistinguishability: symmetric antisymmetric: The antisymmetric wave function is the correct ground state wave function for He atom. For more than two electrons, cannot simply multiply a space function times a spin function: There are only two spin functions! Need a better strategy

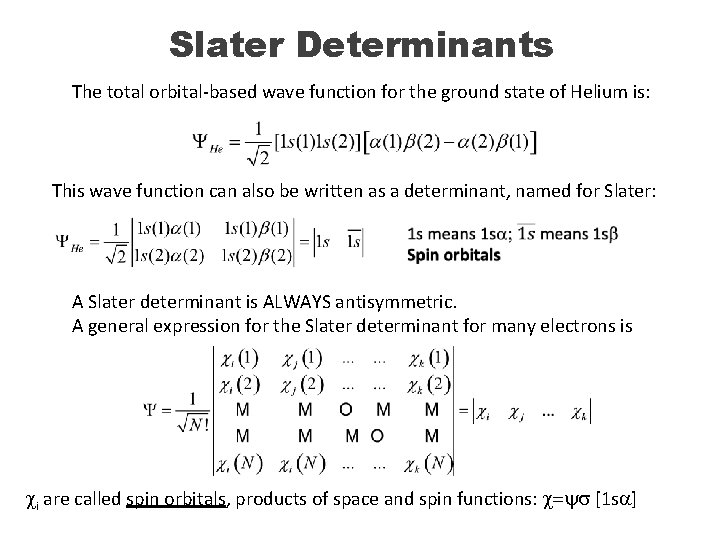

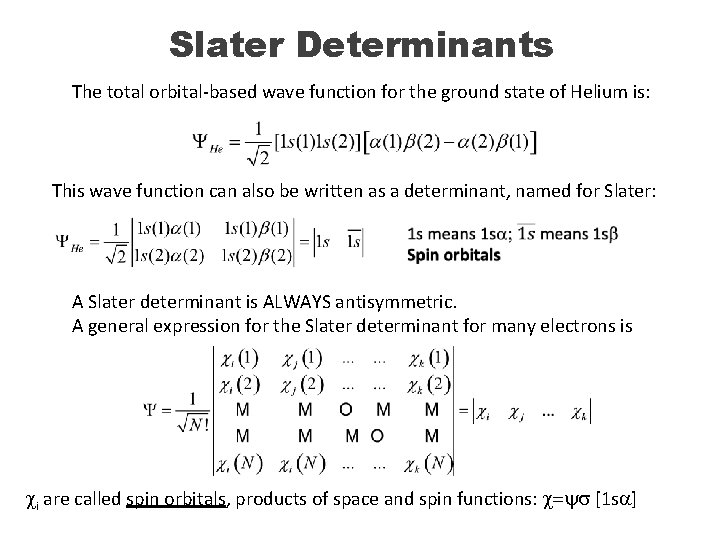

Slater Determinants The total orbital-based wave function for the ground state of Helium is: This wave function can also be written as a determinant, named for Slater: A Slater determinant is ALWAYS antisymmetric. A general expression for the Slater determinant for many electrons is ci are called spin orbitals, products of space and spin functions: c=ys [1 sa]

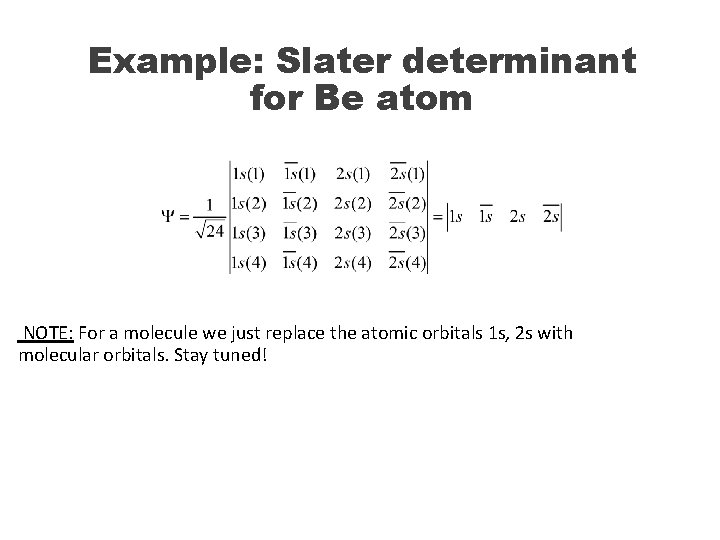

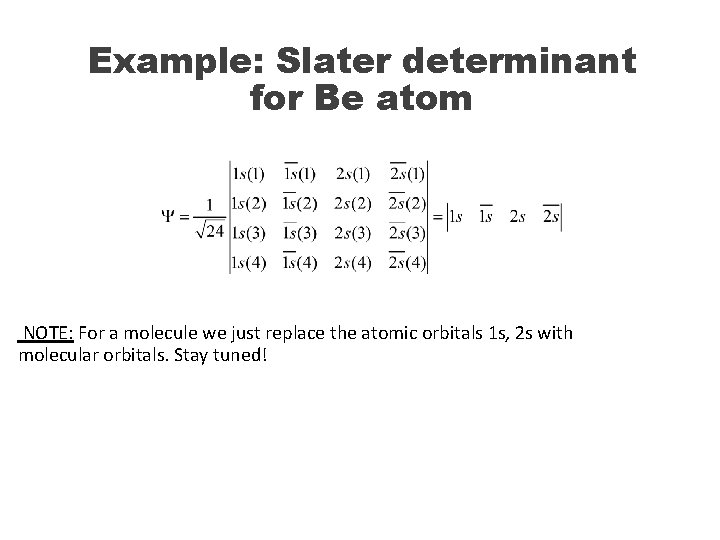

Example: Slater determinant for Be atom NOTE: For a molecule we just replace the atomic orbitals 1 s, 2 s with molecular orbitals. Stay tuned!

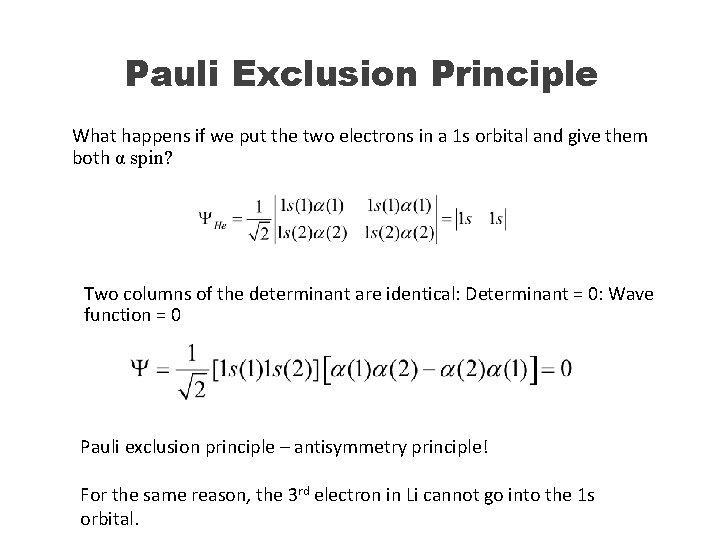

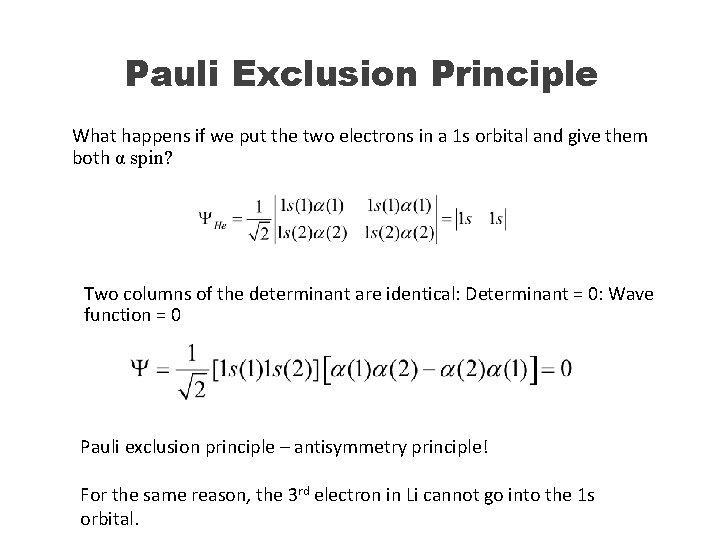

Pauli Exclusion Principle What happens if we put the two electrons in a 1 s orbital and give them both α spin? Two columns of the determinant are identical: Determinant = 0: Wave function = 0 Pauli exclusion principle – antisymmetry principle! For the same reason, the 3 rd electron in Li cannot go into the 1 s orbital.

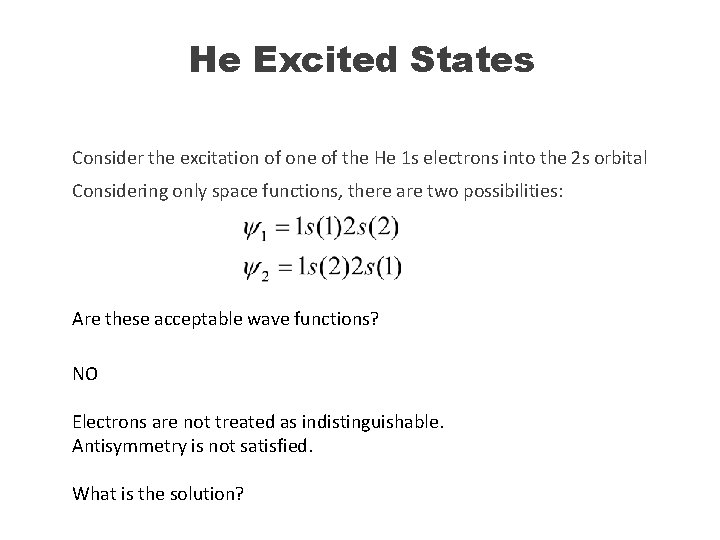

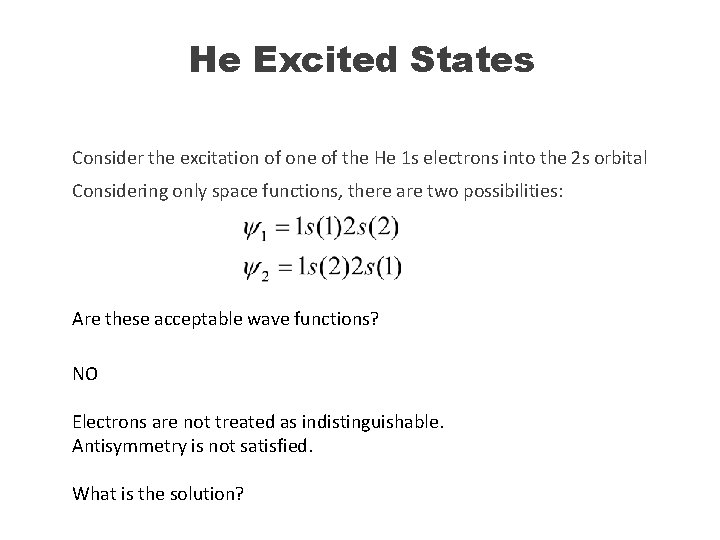

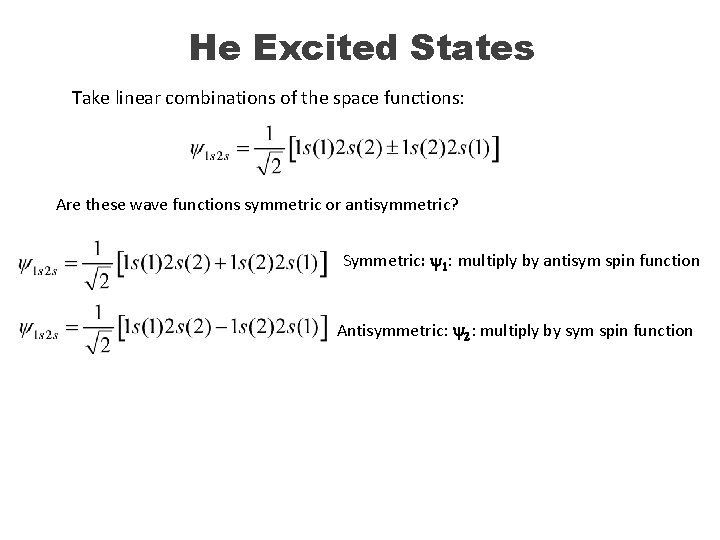

He Excited States Consider the excitation of one of the He 1 s electrons into the 2 s orbital Considering only space functions, there are two possibilities: Are these acceptable wave functions? NO Electrons are not treated as indistinguishable. Antisymmetry is not satisfied. What is the solution?

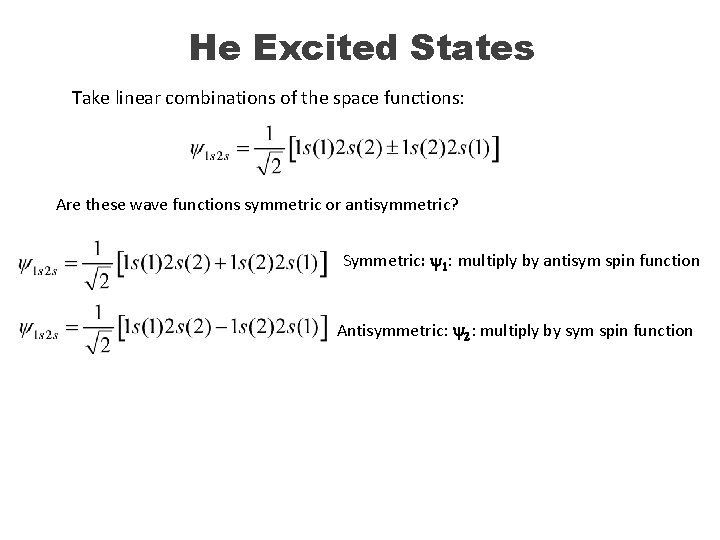

He Excited States Take linear combinations of the space functions: Are these wave functions symmetric or antisymmetric? Symmetric: y 1: multiply by antisym spin function Antisymmetric: y 2: multiply by sym spin function

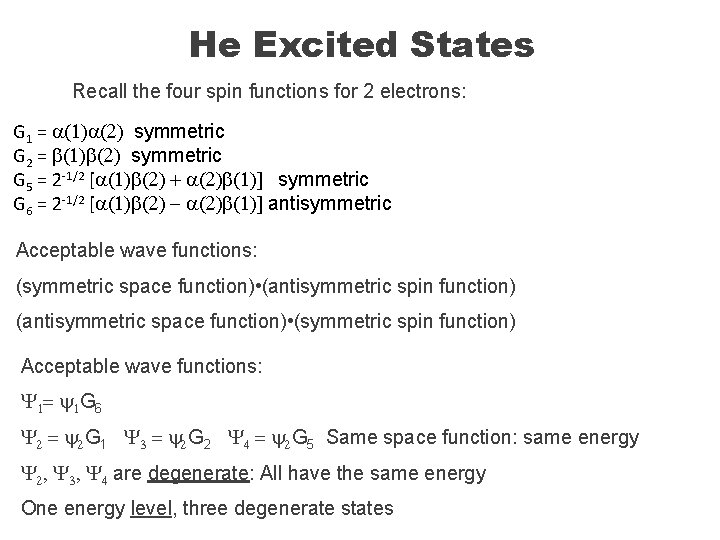

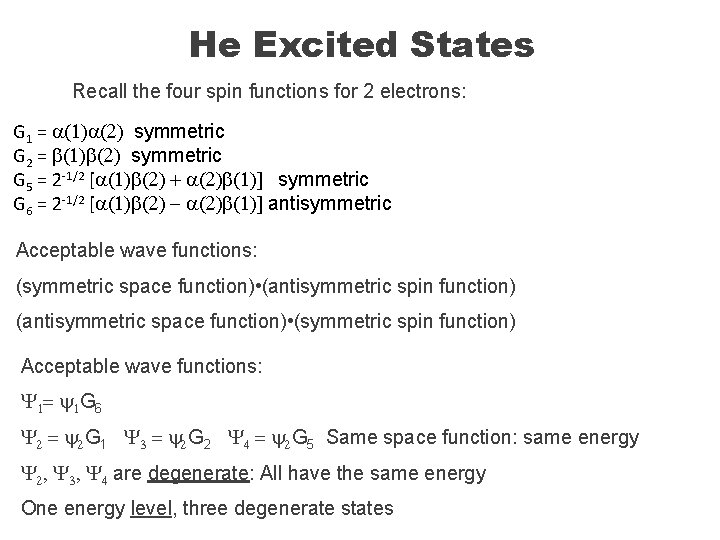

He Excited States Recall the four spin functions for 2 electrons: G 1 = a(1)a(2) symmetric G 2 = b(1)b(2) symmetric G 5 = 2 -1/2 [a(1)b(2) + a(2)b(1)] symmetric G 6 = 2 -1/2 [a(1)b(2) - a(2)b(1)] antisymmetric Acceptable wave functions: (symmetric space function) • (antisymmetric spin function) (antisymmetric space function) • (symmetric spin function) Acceptable wave functions: Y 1 = y 1 G 6 Y 2 = y 2 G 1 Y 3 = y 2 G 2 Y 4 = y 2 G 5 Same space function: same energy Y 2, Y 3, Y 4 are degenerate: All have the same energy One energy level, three degenerate states

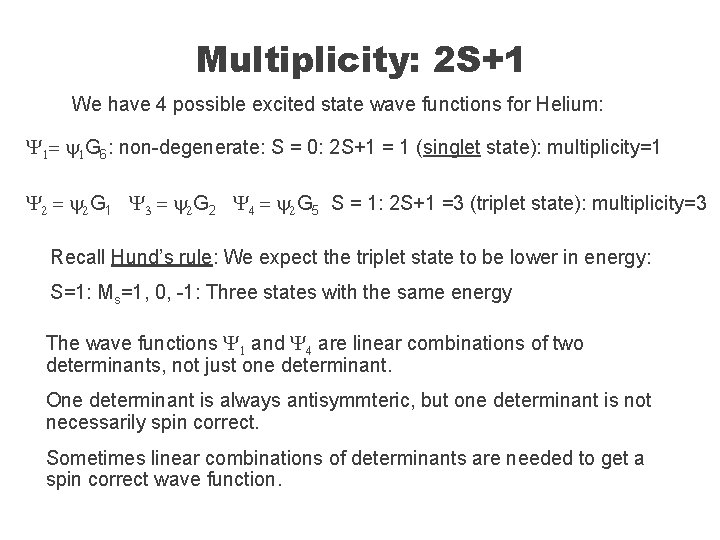

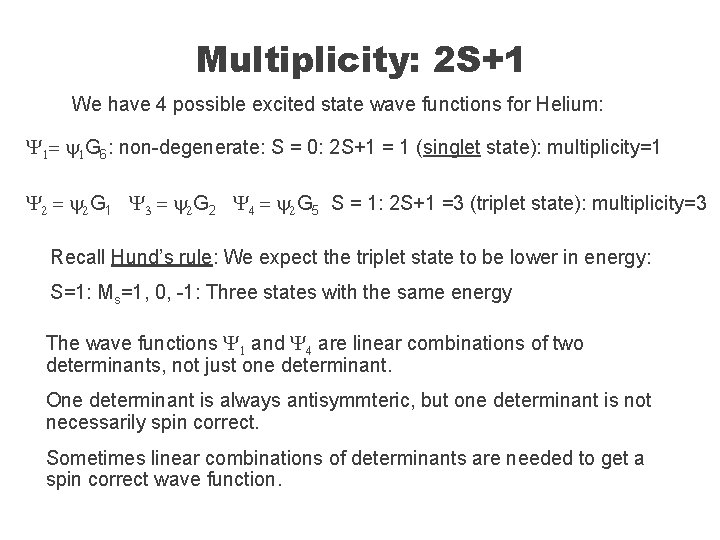

Multiplicity: 2 S+1 We have 4 possible excited state wave functions for Helium: Y 1= y 1 G 6: non-degenerate: S = 0: 2 S+1 = 1 (singlet state): multiplicity=1 Y 2 = y 2 G 1 Y 3 = y 2 G 2 Y 4 = y 2 G 5 S = 1: 2 S+1 =3 (triplet state): multiplicity=3 Recall Hund’s rule: We expect the triplet state to be lower in energy: S=1: Ms=1, 0, -1: Three states with the same energy The wave functions Y 1 and Y 4 are linear combinations of two determinants, not just one determinant. One determinant is always antisymmteric, but one determinant is not necessarily spin correct. Sometimes linear combinations of determinants are needed to get a spin correct wave function.

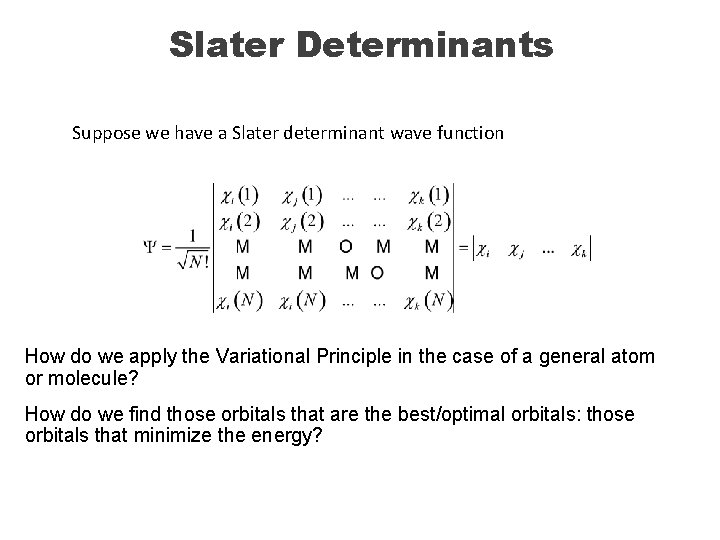

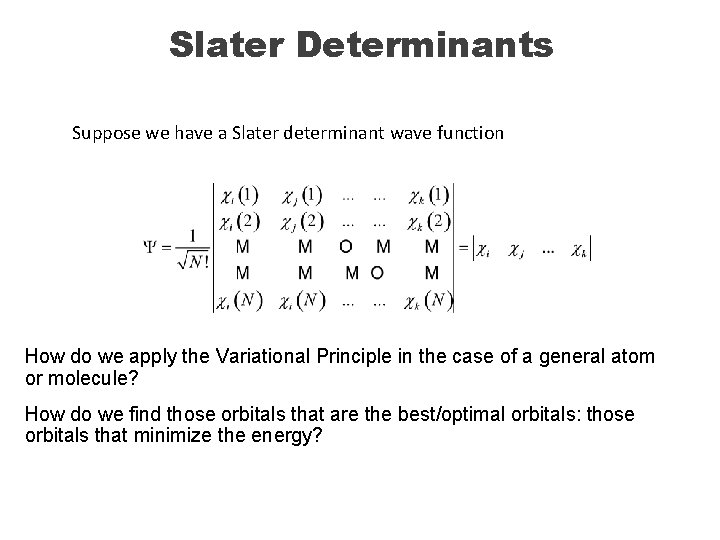

Slater Determinants Suppose we have a Slater determinant wave function How do we apply the Variational Principle in the case of a general atom or molecule? How do we find those orbitals that are the best/optimal orbitals: those orbitals that minimize the energy?

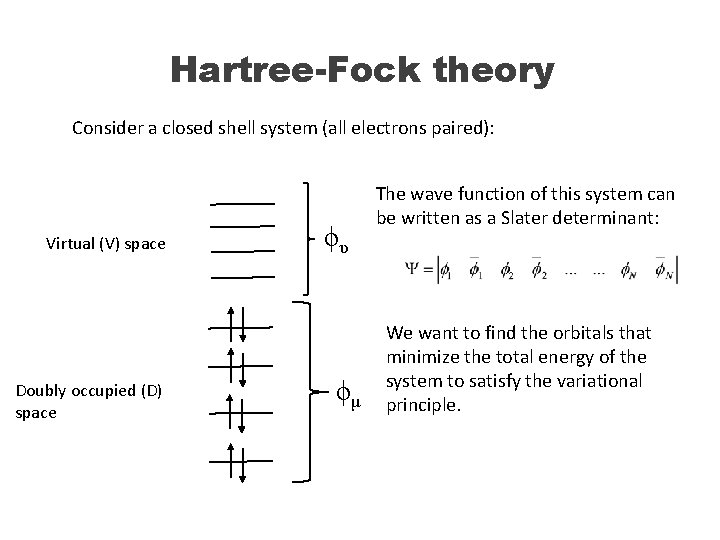

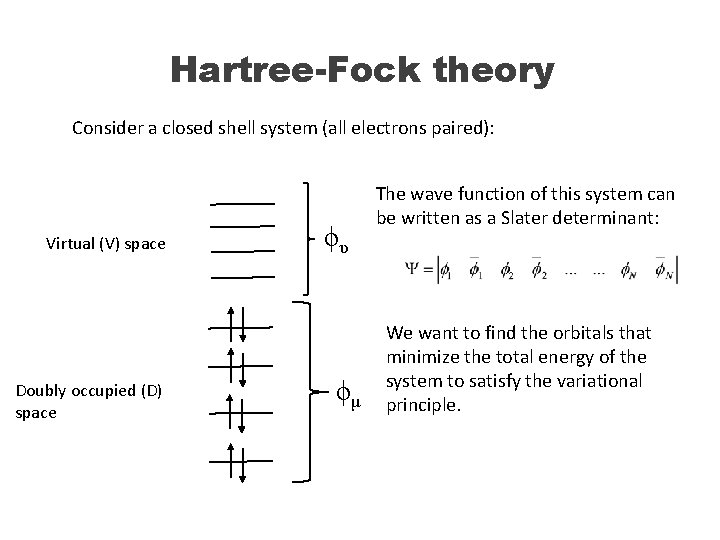

Hartree-Fock theory Consider a closed shell system (all electrons paired): Virtual (V) space Doubly occupied (D) space ϕυ ϕμ The wave function of this system can be written as a Slater determinant: We want to find the orbitals that minimize the total energy of the system to satisfy the variational principle.

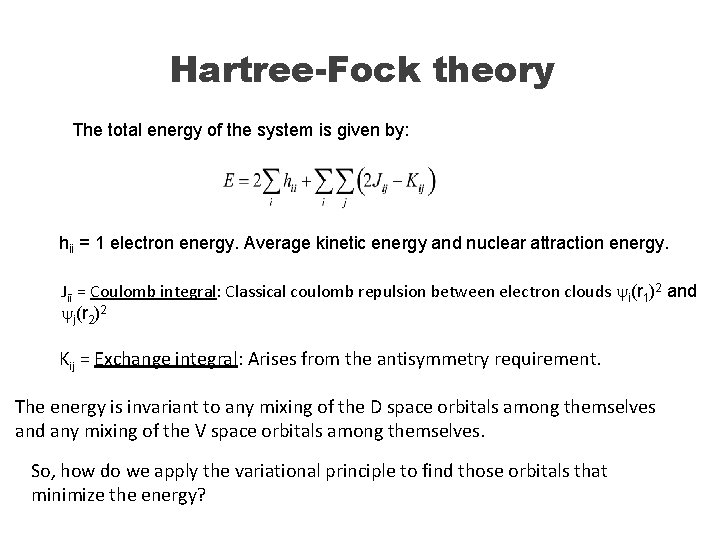

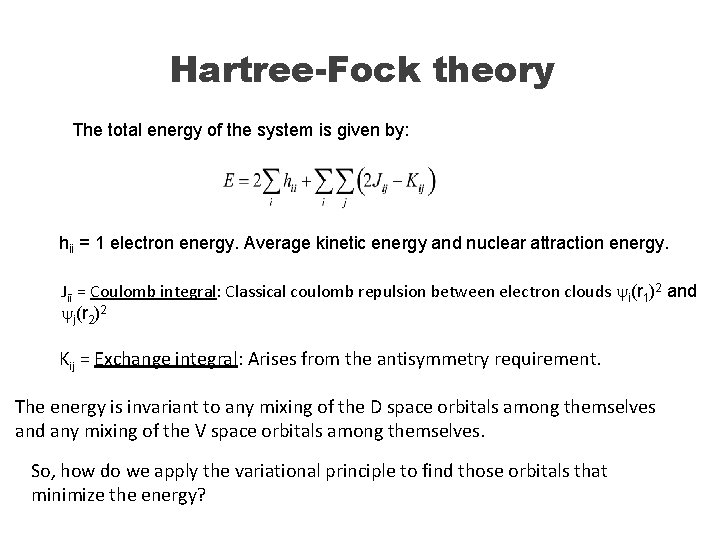

Hartree-Fock theory The total energy of the system is given by: hii = 1 electron energy. Average kinetic energy and nuclear attraction energy. Jii = Coulomb integral: Classical coulomb repulsion between electron clouds yi(r 1)2 and yj(r 2)2 Kij = Exchange integral: Arises from the antisymmetry requirement. The energy is invariant to any mixing of the D space orbitals among themselves and any mixing of the V space orbitals among themselves. So, how do we apply the variational principle to find those orbitals that minimize the energy?

Hartree-Fock theory So, how do we apply the variational principle to find those orbitals that minimize the energy? Mix occupied with unoccupied orbitals! Find the optimal mixing The minimization of the energy leads to the Hartree. Fock equations: ϕυ ϕμ Average field seen by the electron. F = Fock operator; J = Coulomb operator; K = exchange operator

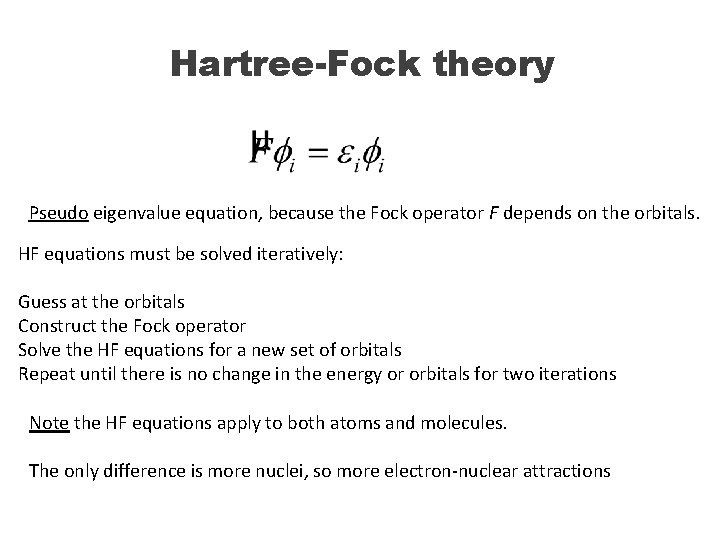

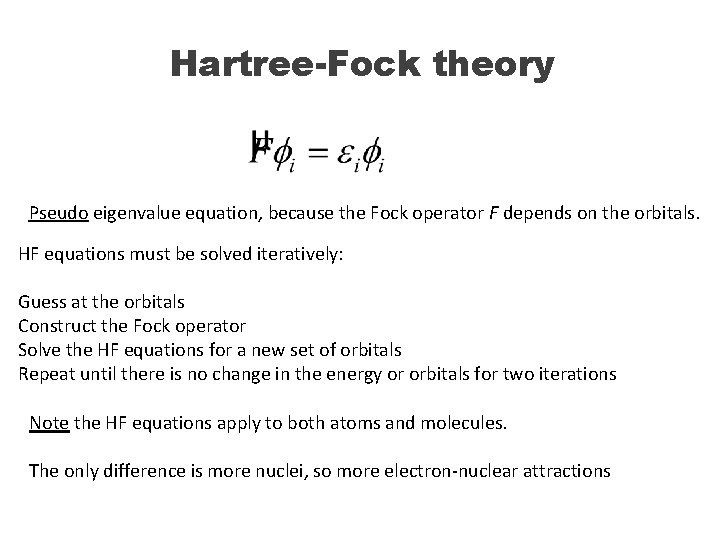

Hartree-Fock theory Pseudo eigenvalue equation, because the Fock operator F depends on the orbitals. HF equations must be solved iteratively: Guess at the orbitals Construct the Fock operator Solve the HF equations for a new set of orbitals Repeat until there is no change in the energy or orbitals for two iterations Note the HF equations apply to both atoms and molecules. The only difference is more nuclei, so more electron-nuclear attractions

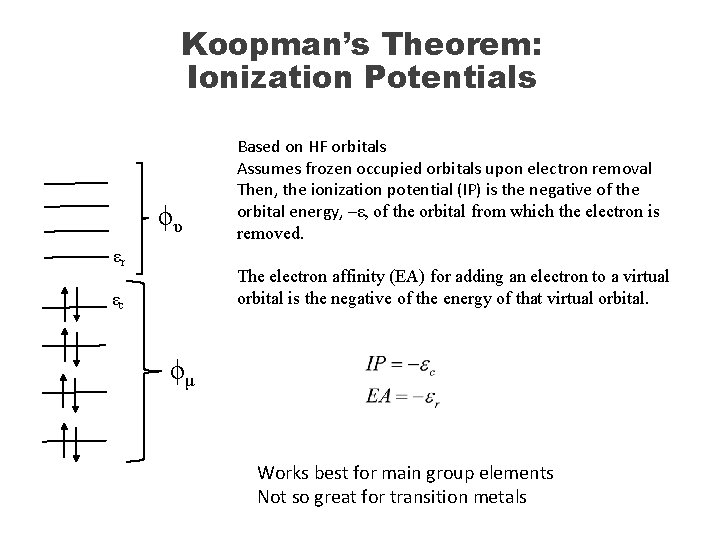

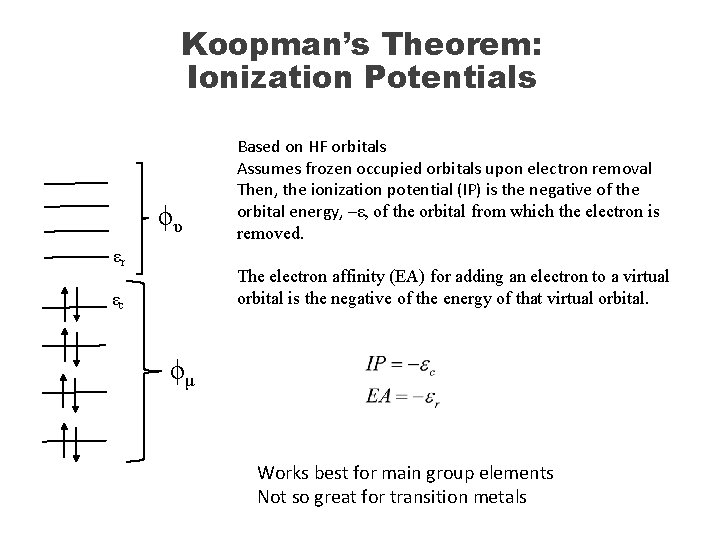

Koopman’s Theorem: Ionization Potentials ϕυ εr Based on HF orbitals Assumes frozen occupied orbitals upon electron removal Then, the ionization potential (IP) is the negative of the orbital energy, –ε, of the orbital from which the electron is removed. The electron affinity (EA) for adding an electron to a virtual orbital is the negative of the energy of that virtual orbital. εc ϕμ Works best for main group elements Not so great for transition metals

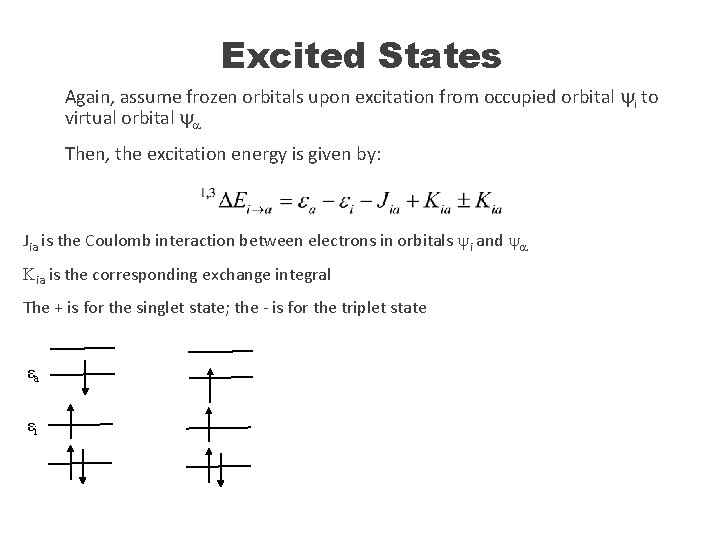

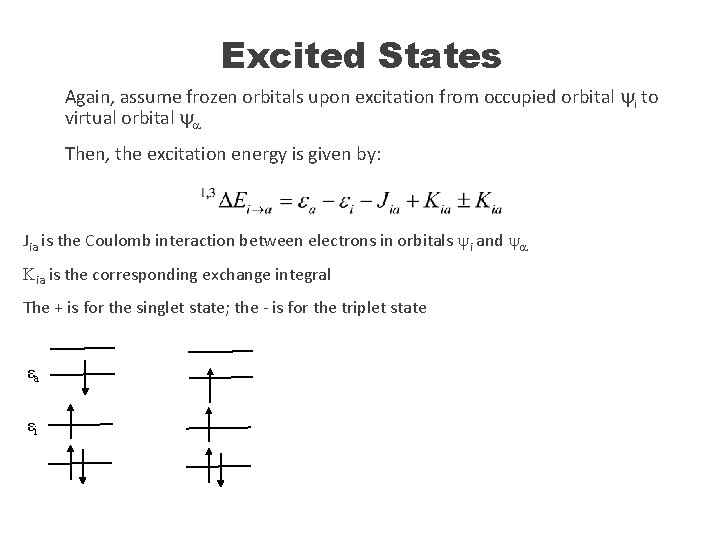

Excited States Again, assume frozen orbitals upon excitation from occupied orbital yi to virtual orbital ya Then, the excitation energy is given by: Jia is the Coulomb interaction between electrons in orbitals yi and ya Kia is the corresponding exchange integral The + is for the singlet state; the - is for the triplet state εa εi

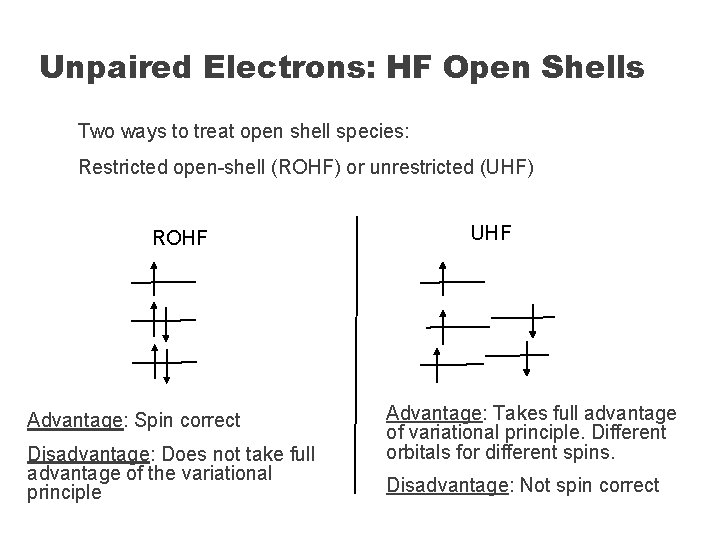

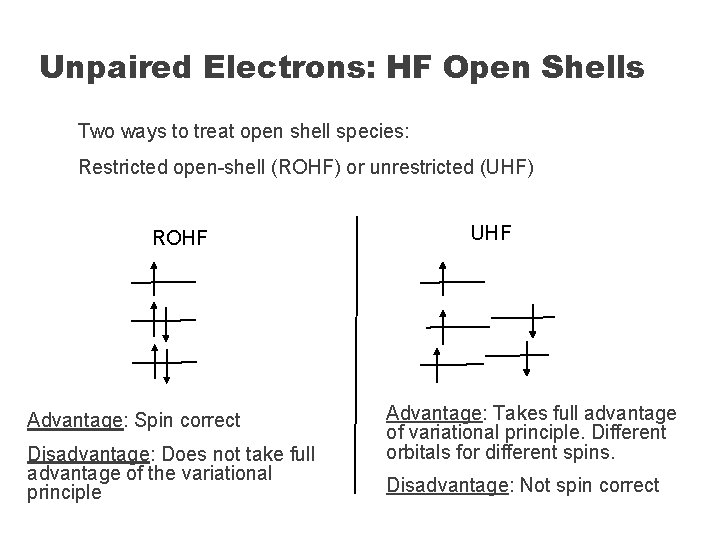

Unpaired Electrons: HF Open Shells Two ways to treat open shell species: Restricted open-shell (ROHF) or unrestricted (UHF) ROHF Advantage: Spin correct Disadvantage: Does not take full advantage of the variational principle UHF Advantage: Takes full advantage of variational principle. Different orbitals for different spins. Disadvantage: Not spin correct