Chapter Two Counting Techniques 2 1 Basic Counting

Chapter Two. Counting Techniques 2. 1. Basic Counting Rules (or Principles): The Sum Rule: Suppose there are two approaches to completing a task. The first approach produces m results, and the second approach produces n results, where all these results are distinct from one another. Thus, there a total of m + n results for completing the task (based on the two approaches). A set-theoretic interpretation of the sum rule using Venn diagrams: If we let A = the set of m results from approach one, and let B = the set of n results from approach two, then |A| = m, and |B| = n. Thus, |A B| = |A| + |B| = m + n, since A B = . m results Notes: Total: m + n results (1) More generally, |A B| = |A| + |B| – |A B|, when all sets are finite. (2) The sum rule is often used in a complementary fashion, i. e. , |A| = |A B| – |B|, if A B = . Example: How many positive integers less than 1000 are not divisible by 12? The positive integers less than 1000 (i. e. , from 1 through 999) that are a multiple of 12 include 12, 24, …; the total count equals 999/12 = 83 (the integer quotient using the floor notation). Thus, the count of positive integers less than 1000 not divisible by 12 is 999 – 83 = 916. 2 -1, © Dr. S. Lang

Example: How many positive integers less than 1000 are a multiple of 3 or 5 (or both)? Let A = {n | 1 n 999, and 3 | n}, and let B = {n | 1 n 999, and 5 | n}; that is, A is the set of multiples of 3 less than 1000, and B is the set of multiples of 5 less than 1000. Thus, |A| = 999/3 = 333, and |B| = 999/5 = 199. Note that A B = {n | 1 n 999, and 15 | n} because a multiple of 3 and 5 is exactly a multiple of 15. Thus, |A B| = 999/15 = 66. Therefore, by applying the sum rule, |A B| = |A| + |B| – |A B| = 333 + 199 – 66 = 466. The Product Rule: Suppose it takes two steps to complete a task. There are m paths (methods, or ways) to complete the first step and, for each of these paths, there are n paths to complete the second step. Thus, there a total of mn paths to complete the two steps (in that order). Notes: (1) The product rule can be generalized to situations involving more than 2 steps. (2) The product rule applies to situations in which the ordering of the steps is crucial, i. e, a result must follow the order of step 1, then step 2, etc. Step 1 Step 2 A graphical representation of the product rule (see figure): Path 1 Path m Path 1 Path n Total: mn paths 2 -2, © Dr. S. Lang

Example: How many 3 -digit decimal integers are there? (That is, count the integers from 100, the smallest 3 -digit integer, through 999, the largest 3 -digit integer. ) We can include (or count) all such integers by performing 3 steps: select the first (leftmost) digit, select the middle digit, then select the last (rightmost) digit. There are 9 choices (1 through 9) for the first digit, and for each of these, there are 10 choices (0 through 9) for the middle digit, and finally, for each of the combinations so far, there are 10 choices for the last digit. Thus, the total count is 9 * (10) = 900, applying the product rule. Alternatively, we can solve the problem by considering the complementary problem. There a total of 999 integers counting from 1 thorough 999 (the last 3 -digit number). Out of these there are 99 integers that are 2 digits or less (from 1 through 99). Thus, the total of 3 -digit integers is 999 – 99 = 900. Note: Often times a problem is solved by using a combination of the sum (including its complementary version) and product rules. The sum rule is used to divide the solutions into disjoint groups (subsets), so that each is counted separately. Example: Count the user passwords that must contain between 4 and 8 printable characters (upper or lower-case letter, digit, other punctuation and special characters on the keyboard except for the blank character). First, divide the possible passwords into 5 disjoint groups based on their lengths ( 4 through 8). Since there are 73 possible characters for each character of a password, the are 73*73*73*73 = 734 possible 4 -character passwords using the product rule. Similarly, there are 735 possible 5 -character passwords, etc. , so the total count of passwords of length between 4 and 8 is the sum of 734 + 735 + 736 + 737 + 738, using the sum rule. 2 -3, © Dr. S. Lang

The Group Rule: Suppose a set containing n elements is divided into disjoint and equal-sized subsets (or groups), each containing m elements. Thus, the number of groups equals n / m. This is true because by the sum rule, the sum of the sizes of these subsets, m + …+ m, should be equal to the total size of n. Thus, there must be exactly n / m groups. The following figure depicts the situation. Example: Suppose a manufacturer makes bracelets using 6 colored beads (red, orange, blue, purple, pink, and green) arranged in different orders (see figure below), where each colored bead is used exactly once. How many different kinds of bracelets the manufacturer needs to produce in order to cover all possible patterns? m m m Total: n = m * (n / m) Since there are 6 possible colors for the first bead, then for each of the selected first beads, there are 5 colors for the second bead (of a different color from the first), etc. , the total count of possible bracelet patterns is 6*5*4*3*2*1 = 720, but not all these have to be manufactured differently. The reason is that for each of these bracelet patterns, turning it clockwise can produce 5 additional distinct patterns. Also, each pattern manufactured can also be used for its mirror-imaged pattern. Thus, the 720 patterns can be grouped into subsets of 6*2 = 12 “equivalent” patterns. Thus, the total number of groups the manufacture needs = 720 / 12 = 60. 2 -4, © Dr. S. Lang

The Rules of Counting Arguments: (1) If there are two finite sets A and B, and there is a one-to-one correspondence between the elements of the two sets (i. e. , it is possible to relate each element of set A to exactly one element of set B through a correspondence without missing any part of B), then |A| = |B|. (2) If the same set is counted in two different ways resulting in the counts n and m, then n = m. (3)Example: Suppose every student currently enrolled at a university is given a unique student ID. Thus, counting the number of valid IDs gives the number of enrolled students (using the counting argument (1) given above). (4)Example: Explain why the sum of the first n odd positive integers equals n 2; that is, 1 + 3 + … + (2 n – 1) = n 2. (For example, 1 = 12; 1 + 3 = 4 = 22; 1 + 3 + 5 = 9 = 32, etc. ) (5)Draw a square of width n and lay an n by n grid on top (see the figure for n = 4). The total number of small squares is n 2. We can also count them along the diagonal from the lower-left corner extended toward the upper-right corner as follows: we first count one square at the corner (green in the figure); moving along the diagonal we then count the next on the diagonal plus the two to its left and below (blue ones); then the next group of 5 squares (purple ones), etc. In this way, there will be n groups where each count of the squares equals the next odd integer. Thus, the formula is proved using the counting argument (2) given above. 2 -5, © Dr. S. Lang

2. 2. Permutations: Theorem: Suppose there are n distinct objects and out of which r objects are selected in order, where 1 r n and the ordering is significant. The total count of distinct selections, known as the number of permutations of n objects selecting r at a time, is equal to P(n, r) = n(n – 1)(n – 2) … (n – r + 1). In particular, when r = n, the count equals P(n, n) = n(n – 1)… (1) = n!, the n factorial. This theorem follows easily from the product rule. There are n choices for the first selection and, for each of these selections, there are (n – 1) second choices, etc. , finally there are (n – r + 1) choices for the rth selection. The total count is the product of all the individual counts of choices. Example: Count the positive integers less than 1000 that have no duplicated digits. Answer: Since there are 10 possible digits to use (0 through 9), for each of the three possible digit positions, the count is P(10, 3) = 10*9*8 = 720. (Note that 0 will not be counted even though digit 0 may be used. ) Example: How many distinct “words” can be formed by rearranging the three letters O, W, and L, each used exactly once? (Answer: 3! = 6. ) Example: Suppose an array of size n in a computer program contains distinct integer values between 1 and 1000, where 1 n 1000. The total number of ways to populate the array is P(1000, n). Example: If a student found out that he received 4 distinct grades for the 4 classes he took, where a grade can be any of the 12 possibilities (A, A–, B+, B, …, F). The total number of possible grade results for the person is P(12, 4) = 12*11*10*9 = 11880. Note that the above P(n, r) formula applies when the n objects are distinct, and the ordering of the selections matters. Also note P(n, r) = n! / (n – r)! but this formula isn’t computationally efficient. 2 -6, © Dr. S. Lang

Theorem: Suppose there are n objects divided into r types: n 1 of them belong to type 1, n 2 of them belong to type 2, …, nr of them belong to type r. The total number of permutations of arranging these n objects (where the ordering is significant) but treating objects of the same type indistinguishable, is equal to (This is the formula for permutations with “duplicates”. ) We can explain (prove) the formula using the following argument. There a total of n! permutations when we treat all n objects as distinct ignoring those of the same types. Pick any of these n! results, call it P. P belongs to a group of (n 1! n 2! … nr!) equivalent (or identical) permutations because the n 1 type-one objects in Q can be rearranged in n 1! many ways, and the n 2 type-two objects in P can be rearranged in n 2! many ways, etc. , the nr type-r objects in P can be rearranged in nr! many ways, resulting in a total of (n 1! n 2! … nr!) identical permutations (identical to P). By using the group rule, the number of distinct groups is n! / (n 1! n 2! … nr!). Example: We use an example to explain this grouping concept. How many distinct words can be formed by using the letters in the word TELEPHONE? There are 9 letters but not all distinct (3 letter “E”s). If we treat the E’s as distinct (call them E 1, E 2, and E 3), the total count of permutations is 9!. However, rearranging the letter Es in each of these permutations results in the same word but gets counted 3! = 6 times. For example, TE 1 LE 2 PHONE 3, TE 1 LE 3 PHONE 2, TE 2 LE 1 PHONE 3, TE 2 LE 3 PHONE 1, TE 3 LE 1 PHONE 2, and TE 3 LE 2 PHONE 1. Thus, the number of words = the count of groups = 9! / 3!, using the group rule. If we use the formula stated in theorem, the total number of distinct permutations (words) formed by the letters of the word TELEPHONE is 9! / (3! 1! 1! … 1!) = 9! / 3!, since we can treat the 3 letter Es as one type; all other letters form distinct types by themselves. 2 -7, © Dr. S. Lang

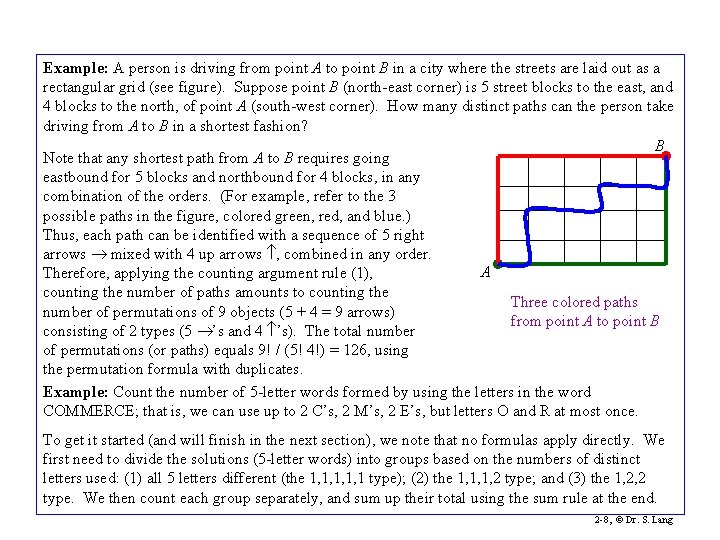

Example: A person is driving from point A to point B in a city where the streets are laid out as a rectangular grid (see figure). Suppose point B (north-east corner) is 5 street blocks to the east, and 4 blocks to the north, of point A (south-west corner). How many distinct paths can the person take driving from A to B in a shortest fashion? B Note that any shortest path from A to B requires going eastbound for 5 blocks and northbound for 4 blocks, in any combination of the orders. (For example, refer to the 3 possible paths in the figure, colored green, red, and blue. ) Thus, each path can be identified with a sequence of 5 right arrows mixed with 4 up arrows , combined in any order. A Therefore, applying the counting argument rule (1), counting the number of paths amounts to counting the Three colored paths number of permutations of 9 objects (5 + 4 = 9 arrows) from point A to point B consisting of 2 types (5 ’s and 4 ’s). The total number of permutations (or paths) equals 9! / (5! 4!) = 126, using the permutation formula with duplicates. Example: Count the number of 5 -letter words formed by using the letters in the word COMMERCE; that is, we can use up to 2 C’s, 2 M’s, 2 E’s, but letters O and R at most once. To get it started (and will finish in the next section), we note that no formulas apply directly. We first need to divide the solutions (5 -letter words) into groups based on the numbers of distinct letters used: (1) all 5 letters different (the 1, 1, 1 type); (2) the 1, 1, 1, 2 type; and (3) the 1, 2, 2 type. We then count each group separately, and sum up their total using the sum rule at the end. 2 -8, © Dr. S. Lang

2. 3. Combinations: Permutations are applied when the order in which the selections are made matters in the counting process. Otherwise, if the selection orders don’t matter, we have the following basic result. Theorem: Suppose there are n distinct objects and we are selecting r objects at a time, where 1 r n and the order of the selections is insignificant. The total number of such combinations (unordered selections) of n objects choosing r objects at a time, is given by the formula C(n, r) =. Note C(n, r) = C(n, n – r) by the formula’s symmetry. Example: Let A be a set of size n, and let 1 r n. The number of subsets of A that contain r elements is equal to C(n, r), by the definition of this notation. (This is because the ordering of the elements in a subset doesn’t matter. ) For example, let A = {a, b, c, d, e} and we want to count the subsets of size 3. Some of them are {a, b, c}, {a, b, d}, {a, b, e}, etc. , but we wouldn’t count {a, c, b} once {a, b, c}has been included. The number of such subsets is C(5, 3) = C(5, 2) = 5*4 / 2! = 10. We can use this example to explain the general formula of theorem. Basically, when selecting r objects from a set of n objects, there are P(n, r) permutations when the order of the selections matters. For each of these permutations (each contain r objects), it can produce a total of r! permutations by rearranging the order, which should be counted only once in the case of combinations. Therefore, we can group those permutations that contain the same selections of r objects (in different order); the number of combinations equals the number of groups which equals P(n, r) / r! using the group rule. 2 -9, © Dr. S. Lang

Example: Suppose a person has two part-time jobs which require him going to the first job for 3 days of the week (any 3 days) and the second job 2 days. The person does the jobs during the weekdays only. How many work schedules can he have for the two jobs? Answer: C(5, 2) = 10. Example: Continued from the above, assume the same two jobs for the person but now he could work on weekends also. He needs to choose 3 days out of 7 days for the first job, then choose 2 days out of the (7 – 3 = 4) remaining days of the week for the second job. Thus, the total number of possible work schedules for him is C(7, 3) * C(4, 2) = 7! / (3! 4!) * 4! / (2! 2!) = 7! / (2! 2! 3!) = 210. Note that in this solution, we applied the product rule by considering the problem as a procedure (or task) involving two steps: (1) pick the days for the first job; then (2) pick the days for the second job. For each step, we used the combination formula because there is no significance in the work schedule about the order of the days for the same job. Example: A student is taking 4 classes in a semester. Suppose she wants to receive A or B grades for all 4 classes, and with at least one A. How many combinations of the final grades will satisfy her? (Assume there are no +/– grades. Also, assume same grades from different classes are counted separately, e. g. , one B grade in English is not the same as one B in Mathematics. ) The outcomes of the grades can be put into groups: (1) 4 A’s; (2) 3 A’s and 1 B; (3) 2 A’s and 2 B’s; and (4) 1 A and 3 B’s. The counts for each group are: (1) 1; (2) C(4, 3) = 4; (3) C(4, 2) = 6; (4) C(4, 1) = 4. The total = 15. Here is a shorter solution. There are 4 classes so we assume each will receive an A or B grade (2 possibilities). Thus, the total number of outcomes is 2*2*2*2 = 16. We need to subtract one from these because they also included one with 4 B’s, which is no good. 2 -10, © Dr. S. Lang

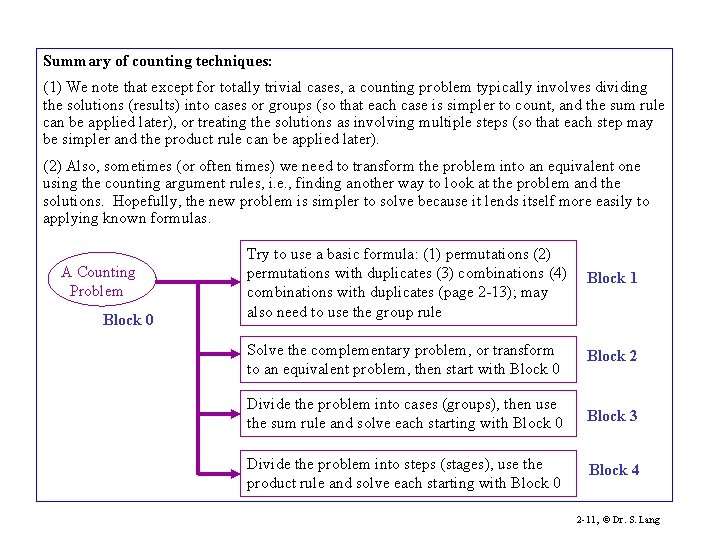

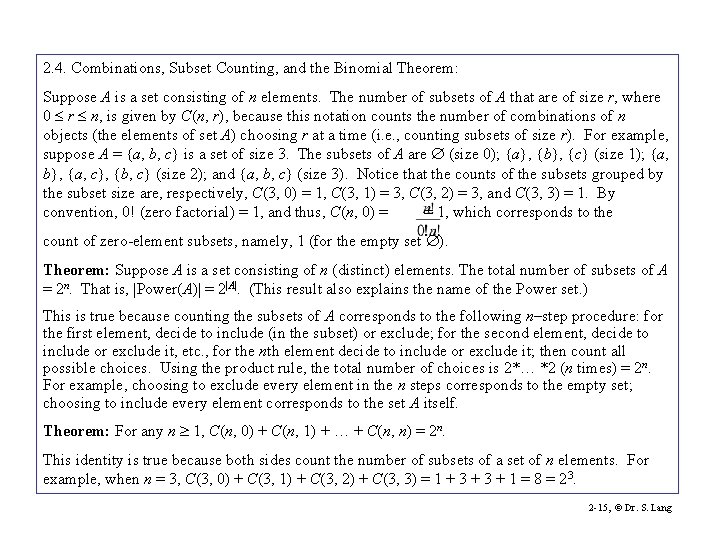

Summary of counting techniques: (1) We note that except for totally trivial cases, a counting problem typically involves dividing the solutions (results) into cases or groups (so that each case is simpler to count, and the sum rule can be applied later), or treating the solutions as involving multiple steps (so that each step may be simpler and the product rule can be applied later). (2) Also, sometimes (or often times) we need to transform the problem into an equivalent one using the counting argument rules, i. e. , finding another way to look at the problem and the solutions. Hopefully, the new problem is simpler to solve because it lends itself more easily to applying known formulas. A Counting Problem Block 0 Try to use a basic formula: (1) permutations (2) permutations with duplicates (3) combinations (4) combinations with duplicates (page 2 -13); may also need to use the group rule Block 1 Solve the complementary problem, or transform to an equivalent problem, then start with Block 0 Block 2 Divide the problem into cases (groups), then use the sum rule and solve each starting with Block 0 Block 3 Divide the problem into steps (stages), use the product rule and solve each starting with Block 0 Block 4 2 -11, © Dr. S. Lang

Example: Let us consider the path counting problem solved earlier (page 2 -8). Since a “solution” (or path) is same as a sequence of 5 right-arrows and 4 up-arrows mixed in some order, a solution is the same as filling in 9 blank spaces with 4 up-arrows and 5 right-arrows (see figure below). Thus, finding a solution is the same as choosing 4 places (out of 9) to hold the up-arrows (and automatically the remaining 5 places will hold the right-arrows). Thus, the count = C(9, 4) = 9! / (4! 5!) = 126. Fill in 9 spaces with 4 ’s and 5 ’s Example: We now continue with counting the 5 -letter words using the letters of COMMERCE (there are 2 C’s, 2 M’s, 2 E’s, and O and R) from page 2 -8. There are 3 groups of solutions: (1) The 1, 1, 1 type, i. e. , 5 distinct letters. A word in this group must use 1 of each letters C, M, E, O, and R. There are 5! = 120 such words. (2) The 1, 1, 1, 2 type. Thus, 1 out of the 5 distinct letters are used exactly twice, and 3 other letters each used once. There are 3 possible letters (C, M, E) to use twice, and there are C(4, 3) = 4 ways to choose 3 other letters to use once each. Thus, the count is 3*4*5!/2! = 720, in which the factor 5!/2! gives the number of permutations of the 5 letters selected of type 1, 1, 1, 2, and the product rule is applied to multiply the counts together. (3) The 1, 2, 2 type. There are C(3, 2) = 3 ways to choose 2 letters to use twice each, and there are C(3, 1) = 3 ways to choose another letter to use once; the count is 3*3*5!/(2!2!) = 270, in which the factor 5!/(2!2!) counts the permutations. The grand total = 120+720+270=1110. 2 -12, © Dr. S. Lang

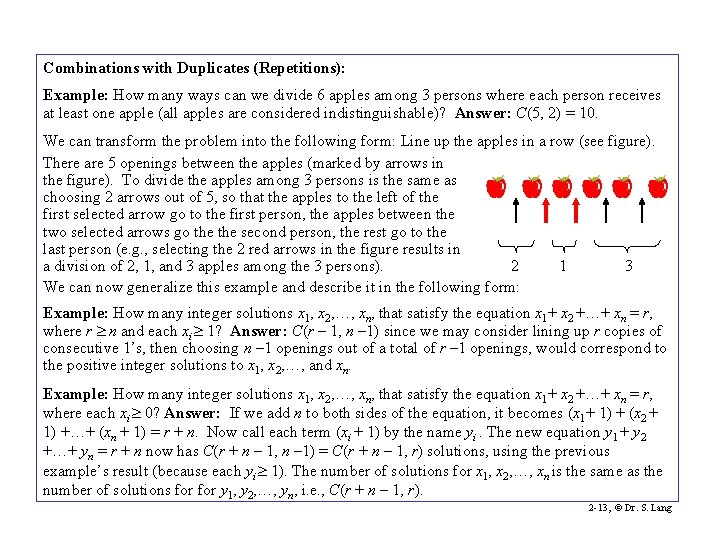

Combinations with Duplicates (Repetitions): Example: How many ways can we divide 6 apples among 3 persons where each person receives at least one apple (all apples are considered indistinguishable)? Answer: C(5, 2) = 10. We can transform the problem into the following form: Line up the apples in a row (see figure). There are 5 openings between the apples (marked by arrows in the figure). To divide the apples among 3 persons is the same as choosing 2 arrows out of 5, so that the apples to the left of the first selected arrow go to the first person, the apples between the two selected arrows go the second person, the rest go to the last person (e. g. , selecting the 2 red arrows in the figure results in 2 1 3 a division of 2, 1, and 3 apples among the 3 persons). We can now generalize this example and describe it in the following form: Example: How many integer solutions x 1, x 2, …, xn, that satisfy the equation x 1+ x 2 +…+ xn = r, where r n and each xi 1? Answer: C(r – 1, n – 1) since we may consider lining up r copies of consecutive 1’s, then choosing n – 1 openings out of a total of r – 1 openings, would correspond to the positive integer solutions to x 1, x 2, …, and xn. Example: How many integer solutions x 1, x 2, …, xn, that satisfy the equation x 1+ x 2 +…+ xn = r, where each xi 0? Answer: If we add n to both sides of the equation, it becomes (x 1+ 1) + (x 2 + 1) +…+ (xn + 1) = r + n. Now call each term (xi + 1) by the name yi. The new equation y 1 + y 2 +…+ yn = r + n now has C(r + n – 1, n – 1) = C(r + n – 1, r) solutions, using the previous example’s result (because each yi 1). The number of solutions for x 1, x 2, …, xn is the same as the number of solutions for y 1, y 2, …, yn, i. e. , C(r + n – 1, r). 2 -13, © Dr. S. Lang

We can now consider the general problem of choosing r things from a collection of n types of objects where each type contains at least r copies of the object (this is known as combination with duplicates or repetitions). Here are some examples. Example: A donut shop carries 20 different kinds of the donuts. How many ways can a person get a box of a dozen donuts? (Choosing 12 things with repetitions out of 20 objects. ) Example: How many combinations of grades can a student receive if the student is taking 4 classes, there are 5 possible grades for a class (A, B, C, D, and F), and we are not distinguishing the classes but only the grades (e. g. , 3 A’s and 1 B counts as one result regardless of which classes received which grades)? (Choosing 4 things with repetitions out of 5 objects. ) More generally, the problem can be expressed as an equation problem considered earlier: Example: How many integer solutions x 1, x 2, …, xn, satisfy the equation x 1+ x 2 +…+ xn = r, where each xi 0? (Choosing r things out of n objects with repetitions; its solution was given previously which is now expressed as the following theorem. ) Theorem: The number of combinations of choosing r things from a collection of n types of objects where each type contains at least r copies of the object (this process is known as combination with repetitions) is given by the formula C(r + n – 1, n – 1) = C(r + n – 1, r). Thus, the answer to the dozen-donut example is C(12 + 20 – 1, 12) = C(31, 12); the answer to the grade report example is C(4 + 5 – 1, 4) = C(8, 4) = 8(7)(6)(5) / 4! = 70. 2 -14, © Dr. S. Lang

2. 4. Combinations, Subset Counting, and the Binomial Theorem: Suppose A is a set consisting of n elements. The number of subsets of A that are of size r, where 0 r n, is given by C(n, r), because this notation counts the number of combinations of n objects (the elements of set A) choosing r at a time (i. e. , counting subsets of size r). For example, suppose A = {a, b, c} is a set of size 3. The subsets of A are (size 0); {a}, {b}, {c} (size 1); {a, b}, {a, c}, {b, c} (size 2); and {a, b, c} (size 3). Notice that the counts of the subsets grouped by the subset size are, respectively, C(3, 0) = 1, C(3, 1) = 3, C(3, 2) = 3, and C(3, 3) = 1. By convention, 0! (zero factorial) = 1, and thus, C(n, 0) = = 1, which corresponds to the count of zero-element subsets, namely, 1 (for the empty set ). Theorem: Suppose A is a set consisting of n (distinct) elements. The total number of subsets of A = 2 n. That is, |Power(A)| = 2|A|. (This result also explains the name of the Power set. ) This is true because counting the subsets of A corresponds to the following n–step procedure: for the first element, decide to include (in the subset) or exclude; for the second element, decide to include or exclude it, etc. , for the nth element decide to include or exclude it; then count all possible choices. Using the product rule, the total number of choices is 2*… *2 (n times) = 2 n. For example, choosing to exclude every element in the n steps corresponds to the empty set; choosing to include every element corresponds to the set A itself. Theorem: For any n 1, C(n, 0) + C(n, 1) + … + C(n, n) = 2 n. This identity is true because both sides count the number of subsets of a set of n elements. For example, when n = 3, C(3, 0) + C(3, 1) + C(3, 2) + C(3, 3) = 1 + 3 + 1 = 8 = 23. 2 -15, © Dr. S. Lang

The Binomial Coefficients: Consider the following binomials (in variables x and y) raised to different exponents: (x + y)1 = x + y (x + y)2 = x 2 + 2 xy + y 2 (x + y)3 = x 3 + 3 x 2 y + 3 xy 2 + y 3 More generally, consider (x + y)n = (x + y) … (x + y) (i. e. , the factor repeated n times). Noticed that each multiplied-out term contains some combinations of x’s and y’s for a total of n factors; that is, each term must be of the form xn – kyk for some k, 0 k n. Also, the coefficient for the term xn – kyk corresponds to the number of combinations of n objects, the n factors in the product (x + y) … (x + y), choosing k at a time (i. e. , choosing k of the factors to select y while for others select x). Thus, the coefficient for xn – kyk in the binomial expansion is C(n, k). Binomial Theorem: For any n 1, (x + y)n = C(n, 0)xn + C(n, 1)xn – 1 y + C(n, 2)xn – 2 y 2 + … + C(n, n – 1)xyn – 1 + C(n, n)yn. (Thus, C(n, k)’s are also known the binomial coefficients. ) We can substitute any values for x and y, resulting in many identities: 2 n =C(n, 0) + C(n, 1) + … + C(n, n) (Use x = y = 1) (1 + x)n = C(n, 0) + C(n, 1)x + C(n, 2)x 2 + … + C(n, n – 1)xn – 1 + C(n, n)xn (Use x = 1, y = x) 0 = C(n, 0) – C(n, 1) + … + (– 1)n. C(n, n) (Use x = 1, y = – 1) 2 -16, © Dr. S. Lang

- Slides: 16