Chapter three Theta theory or theory of thematic

![• 40) • the thief tried [PRO to escape] but the landlord captured • 40) • the thief tried [PRO to escape] but the landlord captured](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/a16f80963d524c3c793a23ed46a4dafe/image-52.jpg)

![• (41) • he: wala zaydun [pro sira: ? a ha: tihi l-kutub-I] • (41) • he: wala zaydun [pro sira: ? a ha: tihi l-kutub-I]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/a16f80963d524c3c793a23ed46a4dafe/image-53.jpg)

- Slides: 53

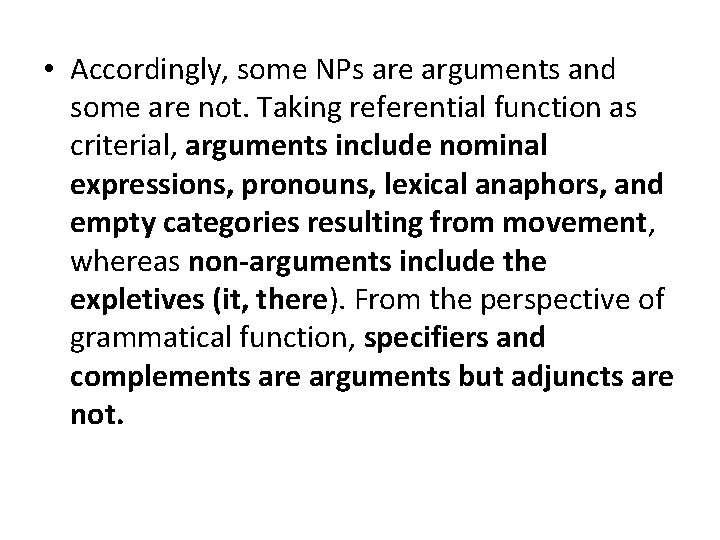

Chapter three Theta theory (or theory of thematic relations) has been around in the literature of generative grammar since the 1960 s (indeed it has antecedents in the work of ancient grammarians). It is concerned with the assignment of thematic roles (theta – roles) to arguments. An argument is an NP which appears as a specifiers or a complement and discharges some sort of referential function in a domain

• Accordingly, some NPs are arguments and some are not. Taking referential function as criterial, arguments include nominal expressions, pronouns, lexical anaphors, and empty categories resulting from movement, whereas non-arguments include the expletives (it, there). From the perspective of grammatical function, specifiers and complements are arguments but adjuncts are not.

• it is also necessary to distinguish between true arguments and quasi-arguments, the latter being illustrated for English by the expletive it occurring in ‘weather constructions. ’ Justifying this distinction is the observation that such tokens of it can control an empty PRO in a subordinate clause and this syntactic relation appears to require some notion of referential dependency, no matter how vague.

• We thus have a situation where the pronoun can be one of three types as shown in (6): • 6) a It is there (true argument) • b It is raining (quasi argument) • c It seems that the bus is approaching ( nonargument)

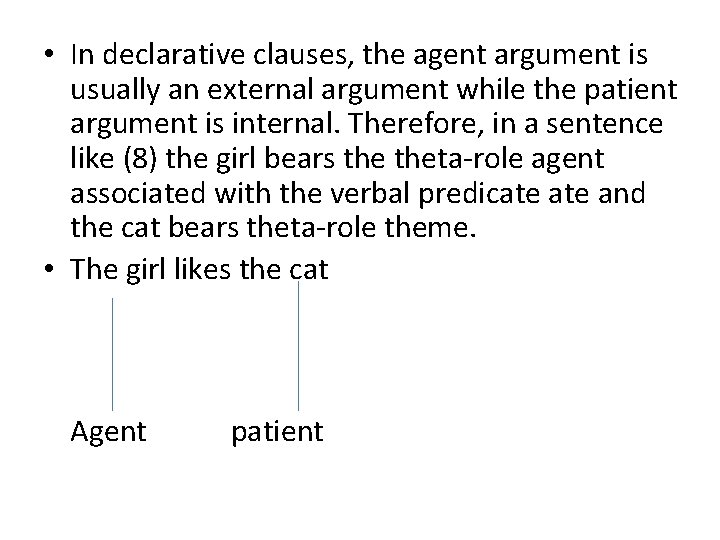

Theta-roles refer to the semantic relations which arguments bear to predicates. A typical list of theta-roles: • • • Agent (or actor): John bought a book patient: John wrote a letter. Experiencer: John was shocked Possessor: John gave Mary a book. Theme : John gave Mary a book Instrument: he shot the lion with a rifle Locative: John parked the car in the garage. Goal: John gave a book to Mary. Source: John bought the gift from the shop.

• In declarative clauses, the agent argument is usually an external argument while the patient argument is internal. Therefore, in a sentence like (8) the girl bears theta-role agent associated with the verbal predicate and the cat bears theta-role theme. • The girl likes the cat Agent patient

• in passives, which will play an important part in later discussion, theme appears as external argument and the Agent, if expressed at all, is demoted to the complement of a preposition.

A contrast between theta and nontheta (theta-bar) positions. • A theta position is a syntactic position in which an argument receives a theta role. It refers, at the level of D-structure, to an NP position that is assigned a theta-role; for instance, a complement position is always a thetaposition, whereas a subject position may be a theta position or a non theta position.

• where in (9 a), John is assigned the agent theta -role, whereas in (9 b) there is not assigned a theta-role at all. • 9) • John bought a car • There is a man outside. • Note, however, that since subjects can contain arguments, the subject position is an argument position. Thus, in (9 b), there occupies an argument position and a theta-bar position.

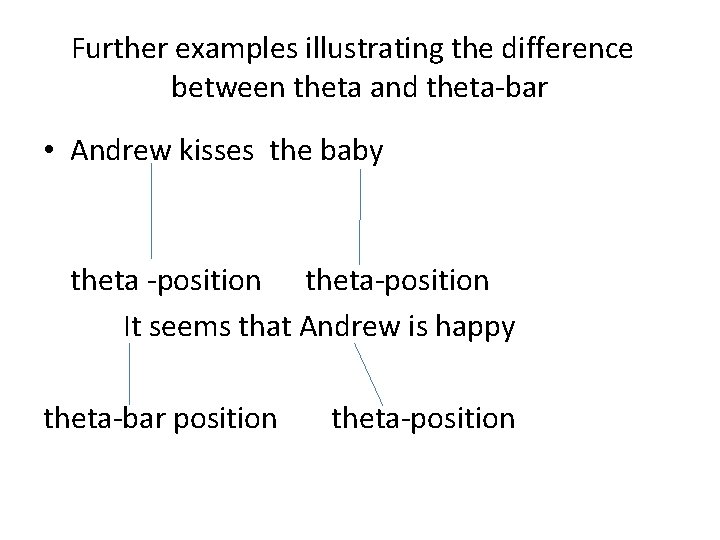

Further examples illustrating the difference between theta and theta-bar • Andrew kisses the baby theta -position theta-position It seems that Andrew is happy theta-bar position theta-position

• In (10 a), both the subject and object of kiss are theta-position, in (10 b), the subject of seems is in a theta-bar position, but the subject of the predicate is happy is in a thetaposition.

• The theta-criterion is the basic principle of theta-theory. • It ensures that an argument is assigned a theta-role by virtue of theta-position it occupies at D-structure. • This means that when Move- α applies, the moved NP leaves a trace from which it inherits theta-role. • Technically, the NP and its trace constitute a chain which has a unique theta-role.

• The theta-criterion requires that every chain receive one and only one theta-role and a consequence of this is that movement of this type can only be to a theta-bar position. • Otherwise, the movement chain would receive two distinct theta-roles and theta -criterion would be violated.

Case theory • Case theory is responsible for determining the distribution of NPs. • It requires that all lexical NPs (NPs that are phonetically realized) must be marked for ‘abstract’ Case or they will fall victim of the Case Filter • * NP if it has a phonetic matrix but no Case.

• case theory is operating at S-structure and (11) requires that every lexical NP must be assigned Case at this level of representation. • On one construal, the Case requirement follows from theta-criterion “since lexical NP must bear Case in order to be assigned a theta-role” • Thus, Case assignment makes an NP visible for theta-role assignment. • languages differ in the number of overt cases they involve. For instance , Latin has six overt cases, appearing on nouns and adjectives, German has four cases appearing on determiners and Arabic has three cases.

• English has three morphologically marked cases: nominative, accusative and genitive. These cases are overt in the personal pronoun paradigms.

A summary of how Case assignment functions : • If inflection contains TNS, Nominative Case is assigned to the [NPS] position • A verb assigns accusative Case to [NP, VP] • A preposition assigns Accusative or Oblique case to [NP, PP] • Nouns and adjectives do not assign case • Case is assigned under government with the exception of genitive • Genitive case is assigned in the structure of [NPX]

• It is of importance that the subject of a finite clause is assigned nominative case under government by INFL in VSO language such as Modern Standard Arabic, and in a configuration of spec-head agreement in SVO language like English. • Consider a finite clause in English such as (12): • he will play strongly • such a sentence has the following structure: • link

• The NP subject he, is assigned Nominative Case because it is in spec-head configuration with a finite INFL. • An example illustrating Nominative Case assigned under government is drawn from the MSA VSO word order in (14 a). • 14) a katab-a zayd-un d-dars-a • wrote Zayd-nom the lesson –acc • ‘Zayed wrote the lesson’ • (14 a) can be represented as in (14 b) • Link

• The subject Zayd in (14 b) is assigned structural Nominative Case by the inflected verb under government (cf. Chapter 2 for detailed discussion). • Regarding Accusative Case, we note that an NP is assigned this Case if governed by a transitive verb; thus, the standard configuration under which Accusative Case assignment takes place is as follows(15) • link

• Putting the two models of Case assignment in (13) and (15) together, Cases in (16 a) are assigned as in (16 b). • Link

• Turning now to prepositions, a prepositional complement NP is marked Oblique Case (or Accusative). For example, consider the NP in (17 a) • Link

• In English, as in many other natural languages, Case can only be assigned under strict adjacency this could explain the ill-formedness of the following example: • * John read carefully the book. • It is of some interest that even if adjacency is important in English, this claim does not appear to generalize to Arabic. For example, consider (19): • Zayd-un qara? -a l-yawm-a kitaab-an • Zayd-nom read the – day-acc book-acc • ‘Zayd read a book today’

• Regarding the direction of Case assignment, the examples clearly show that: • in English Accusative and Oblique Cases are assigned to the right, while Nominative Case is assigned to the left. • not all grammatical categories are Case assigners. • In English, nouns, adjectives, the infinitive marker to and the passive participle appear not to have Case to assign, as is illustrated in (20): • 20. • a* the demolition the house • b* John is proud Mary • c* John to be happy] please Mary sd • d* It was demolished the house

• the ill-formedness of the examples in (20) is due to violations of the Case Filter; • the house in (20 a) is not assigned Case since it is preceded by the N demolition, which is not a Case assignor. • Similarly, Mary in (20 b), which is preceded by the adjective proud, John in (20 c), which is followed by the infinitive maker to • and the house in (20 d)_ which is preceded by the passive participle, all fail to satisfy the Case Filter.

• In contrast to the fairly traditional Case Theory I have just described, Chomsky adds N and A to the list of Case assignors, and distinguishes two types of Case: structural case, and inherent case. The former is assigned by virtue of a structural relation at S-structure, while the latter is assigned by virtue of a thematic relation at D-structure. We shall have more to say about this contrast in connection with the treatment of DOCs.

Government • Setting aside the spec-head relation between a nominative subject and a finite INFL in a SVO language, the previous section has assumed that Case assignment can take place only when the Case assignor and the NP to which it assigns Case bear a structural relation, one to another, known as government. This relation has many definitions but one which will serve to introduce the topic is: • 21) α governs B if • a α c-commands B – and • b every maximal projection dominating α dominates B. • this definition employs the structural relation c-command this itself can be defined in a number of ways. For our purposes here, the original definition from Reinhart (1979) in (22) will suffice:

• α c-commands B – if the first branching node dominating α - also nominates B, and (a) α does not dominate B, (b) B does not dominate α • A more liberal notion of command, also extensively employed in linguistic theory, is mcommand. This can be defined as in (23): • • α m-commands B – iff a. α does not dominate B B does not dominate α the minimal maximal projection dominating α also dominates B

• (21) above requires that a governor ccommands the category that it governs and that intervening maximal projections such as CP and NP are barriers to government. Consider then the structure in (24): • LINK

• In this structure, α governs B, but B doesn’t govern α, nor does Y govern into B. The reason, quite simply, is that introducing maximal projections (α max. B max respectively) serves to block these candidates for government. • Starting from the definition in (21), there are several particular types of government, which at one time or another have been seen as having an important theoretical role to play.

Head government • • This notion is defined by Rizzi(199 theta: 6) as follows: 25. X head governs Y iff X= (A, N, P, V, AGR, T, etc. ) X m-commands Y No barrier intervenes Relativized minimality is respected. As ((25 a) makes clear, only a zero level category can be a head governor, and the remaining clauses of the definition are concerned with establishing appropriate locality constraints on this type of government.

Antecedent government • • • X antecedent governs Y iff X and Y are coindexed X c-commands Y No barrier intervenes Relativized minimality is respected.

• As co-indexation is induced by movement, this structural relation plays a fundamental role in structures involving movement. • X and Y in (26 a) are free to range over all categories, antecedent government is an issue for all species of movement, including the major types of A-movement, as in passive and raising structures, and A’-movement as in Whmovement, and head movement. • Again (26 b-d) constitute Rizzi’s attempt to identify the appropriate locality constraints on this type of government.

Proper government • Proper government has to do with the licensing of empty categories resulting from movement, and it is often employed in a statement of the empty category principle (ECP). A simple statement of ECP is: • A non-pronominal empty category must be properly governed. • • In this context, proper government can be defined disjunctively in the following terms: • α properly governs B, iff • α head governs B, or • α antecedent governs B. • • The theoretical role of the ECP has been in explaining the differences in extraction possibilities for objects on the one hand, and subjects and adjuncts on the other.

• Consider the English examples in (29): • 29) a who does John this that Bill saw • b* who does John this that it saw Bill • • In (29 a), the trace is head governed by the verb and immediately satisfies the ECP via condition (28 a). in general, long distance movement is legitimate from object position, as in (29 a). in (29 b), on the other hand, the trace is not head governed and the structure requires antecedent government are not satisfied and the structure is ill-formed. In general, long distance movement from subject position is not legitimate. • Arabic is identical to English in this specific respect

Similar Examples • 30) a man ? 9 taqad-a zayd-un ? anna hid-an ra? a-t • who thought zayd-nom that hind-acc saw • who did zayd think that hind saw’ • • • b* man ? 9 taqad-a zayd-un ? anna ra? a-t belaal-an • who thought zayd-nom that saw belaal-acc. • • Many complications follow from these initial observations and for a comprehensive discussion within theoretical framework assumed here, the reader is referred to Rizzi (199 theta). • Of course, there are other important notions appearing in the definitions of this section, most obviously those of barrier (Chomsky, 1986 b) and relativized minimality (Rizzi, 199 theta). Both of these contribute to the idea that there are constraints on grammatical relations such that they cannot obtain across an element of a particular type.

Binding theory • Binding theory is principally concerned with the way pronominal elements and other types of nominal expressions relate to each other. It deals with the distribution of over anaphors like the reflexive himself or the reciprocal each other, overt pronouns like me, her, him, and over referring expressions (R-expressions) like Mary, the boy, etc.

• Binding theory contains three principles, each one dealing with one of these types of expression: • An anaphor must be bound in a local domain • A pronominal must be free in a local domain. • An R-expression must be free everywhere. • As a structural notion, binding is defined in terms of c-command co-indexation as follows • α binds B iff α c-commands B and is coindexed with B • if a nominal expression is not bound it is said to be free.

• A major topic in Binding Theory has been that of how to define ‘local domain’ and I will follow the standard assumption of classical GB that the local domain for anaphors is the same as that for pronominals. (for an alternative view, see Huang, 1982). A popular definition of this domain is as an items governing category which is defined as follows: • B is the governing category for α iff B is the minimal category containing α , a governor of α , and a subject accessible to α. • Conditions A, B and C with ‘local domain’ understood in this way are responsible for the grammatical patterns in (32):

• • • 32) Mary entertained herself by reading an exciting story. Mary praised me She praised John Sally said that Mary is proud of herself. Mary said that Sally knows her He claimed that he knows John. In (32 a) herself is an anaphor. According to Principle A, it must be bound by an antecedent in its governing category; the NP Mary is such an antecedent. • In (32 b), the pronominal me must be free in it governing category, i. e. it must not be bound by Mary; thus the sentence is only grammatical on a contraindexing of Mary and me

• In (32 c) coindexing of she and the Rexpression John is excluded by principle C, which requires that the R-expression must be free everywhere. • In (32 d) Mary must bind the anaphor herself, since it is the only potential binder within the appropriate governing category. Thus Sally cannot bind the anaphor herself because it is outside this governing category

• In (32 e), on the other hand, the pronominal her must be free in its governing category and this requires that it is contraindexed with Sally. It can, however, be bound by Mary or it may acquire its reference from some discourse antecedent. Finally, in (32 f), the R-expression John must not be bound by either of the potential pronominal antecedents, since it must be free everywhere according to principle C.

Modern Standard Arabic • the general principles of binding illustrated in (33), which parallels (32): • 33 a zayd-un salla nafsa-hu • zayd-nom entertained himself • zayd entertained himself • • • b hin-un salla-t-haa hind-nom entertained her ‘hind entertained her’ • • • c hiya salla-t zayd-an she entertained zayd-acc ‘she entertained zayd’ • • • d hind-un qaala-t ? nna fatima-ta faxuura-tun bi-nafs-I-haa hind-nom said that Fatima-acc know her ‘hind said that fatima knows her’

• f • • huwa qaal-a ? anna-hu ya 9 rif-u zayd-an he-nom said that-he know zayd –acc ‘he said that he knows zayd’ Binding theory is extended to deal with aspects of the distribution of various empty categories. • Thus, the trace of A-movement is regarded as a nonovert anaphor which must be bound locally; this provides one route to constrain A-movement to a local operation. • More importantly for our subsequent purposes, the trace of A’-movement is viewed as a non-overt Rexpression, a variable, and as such principle C requires it to be free of binding from an A-position.

• A well –known consequence of this is the Strong Crossover phenomenon, as in the following examples: • a* who does he trust ti • b* who does he think Mary trusts ti • in these examples, ti is bound by he locally in (34 a) and non-locally in (34 b) and the examples are ill-formed, i. e. (34 a) cannot be interpreted as (35 a) and (34 b) cannot be interpreted as (35 b). • who is the X such that X trusts X • who is the X such that X thinks Mary trusts X • if tj is an R-expression in these structures, the correct facts follow.

Movement theory • The transformational component of earlier versions of transformational grammar is connected with the principle of Move alpha in the version of theory we are adopting here. However, it remains necessary to distinguish various types of Move alpha.

XP-movement • Movement of a maximal projection can only be from its base-position to another XP position. • For instance a Wh-NP can move from its base generated position to [spec, CP] leaving a trace (an example of A’-movement), and any NP can move from its base generated position to another NP position under certain circumstances (Amovement). • The latter type of XP-movement is typically motivated by Case Theory and is subject to such constraints as may be imposed by the ECP and the Theta Criterion.

X-movement • Another major type of movement is often referred to as head movement. • It is invoked in the form of verb movement with the verb moving from its base position to the INFL position in VSO languages like MSA. • The moved category adjoins to the host category so that the combination of both elements forms a new complex zero-level category. • Traditionally, which blocks movement of a head over an intervening head position formulates the HMC as (36): • An X may only move to Y which properly governs it.

Bounding theory • Bounding theory provides a further alternative for specifying the locality conditions on movement. Its central condition is Subjacency, which relies on the notion of bounding node. In Chomsky (1973) Subjacency is formulated as (37): • Subjacency Condition: • No constituent can be moved out of more than one bounding node. • Bounding nodes have typically been described as NP and IP in English and the working of (37) can be exhibited in (38) • 38. [who [did [Mary have [the assumption [t that [John saw t]]]]]] • CP IP NP CP IP • *

• It is assumed that the wh-phrase first moves to the intermediate [spec, CP] position as shown in (38). However, its subsequent move to the matrix [spec, CP] crossing NP and IP violates Subjacency. Of course, there are cases of long distance movement in which a wh-item may make a series of moves, each of which obeys the Subjacency Condition as in • (39) • [who [do [you [assume [t that [John saw t]]]]] • CP IP •

Control Theory • Control Theory concerned with the empty category designated PRO. From the point of view of Binding Theory, this can be seen as both pronominal and anaphoric and it occurs in the subject position of infinitivals and gerunds as in (40):

![40 the thief tried PRO to escape but the landlord captured • 40) • the thief tried [PRO to escape] but the landlord captured](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/a16f80963d524c3c793a23ed46a4dafe/image-52.jpg)

• 40) • the thief tried [PRO to escape] but the landlord captured him • [PRO studying Italian] is difficult for me. • It is important to distinguish PRO from the pure pronominal pro which appears as subject of finite clauses in pro-drop languages such as Arabic, Italian, Spanish, Rumanian, Hebrew, and other (Borer, 1981). It has been argued that the subject of what would be a non-finite clause in English is always pro in Arabic and Souali (1992: 200) gives (41) as an example of the sort of representation he favours.

![41 he wala zaydun pro sira a ha tihi lkutubI • (41) • he: wala zaydun [pro sira: ? a ha: tihi l-kutub-I]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/a16f80963d524c3c793a23ed46a4dafe/image-53.jpg)

• (41) • he: wala zaydun [pro sira: ? a ha: tihi l-kutub-I] • tried-3. s. m Zayd-nom buying-acc these the books-gen • ‘Zayd tried to buy these books’