Chapter 9 Part A Muscles and Muscle Tissue

- Slides: 37

Chapter 9 Part A Muscles and Muscle Tissue © Annie Leibovitz/Contact Press Images © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. Power. Point® Lecture Slides prepared by Karen Dunbar Kareiva Ivy Tech Community College

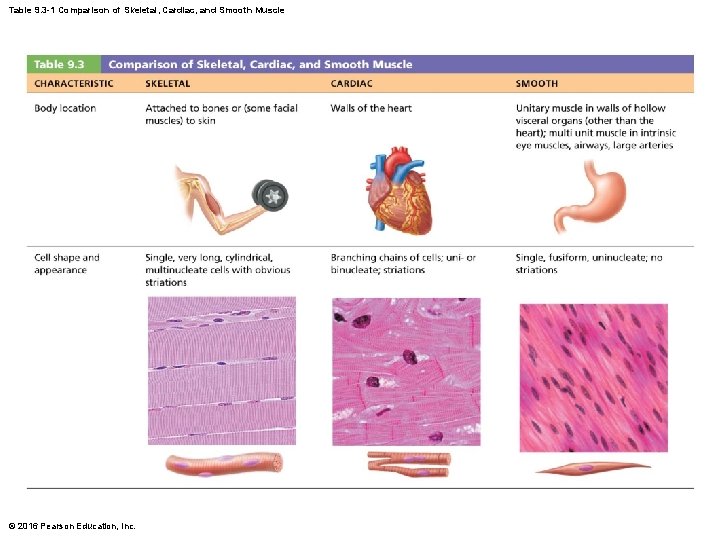

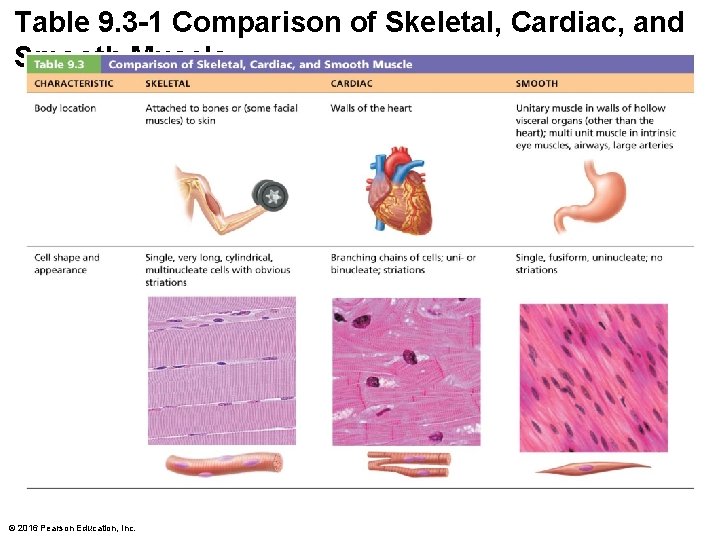

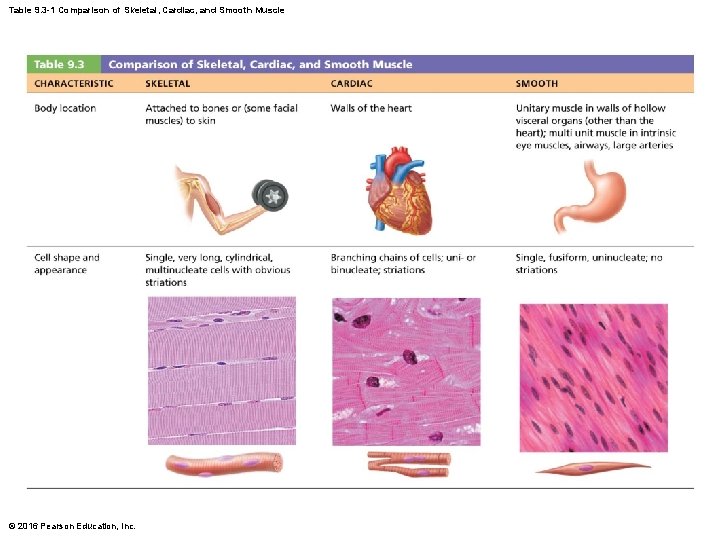

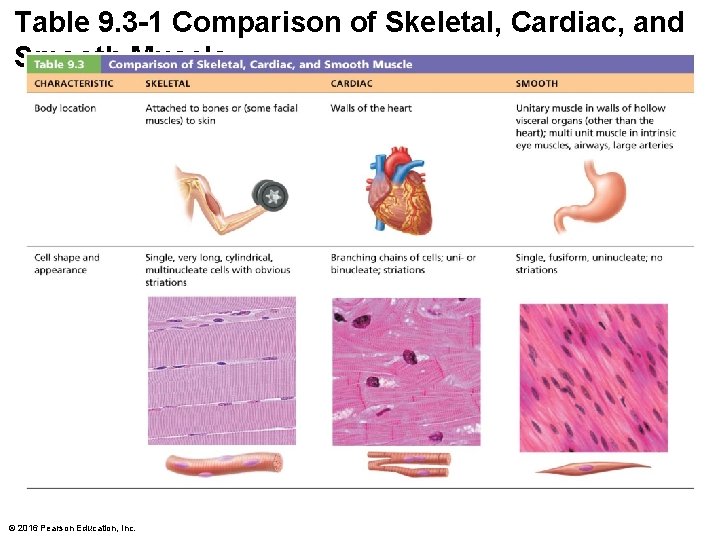

Table 9. 3 -1 Comparison of Skeletal, Cardiac, and Smooth Muscle © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

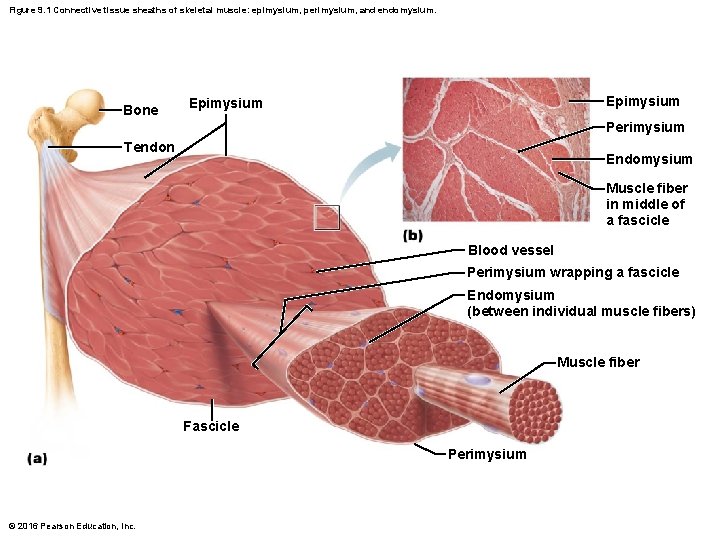

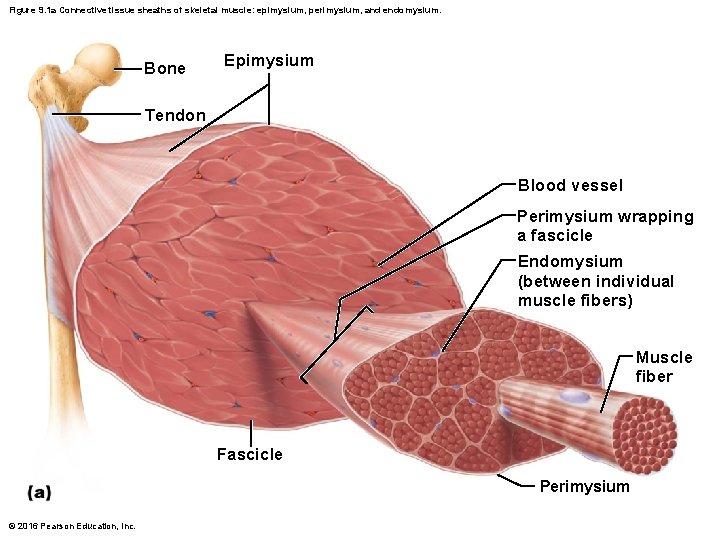

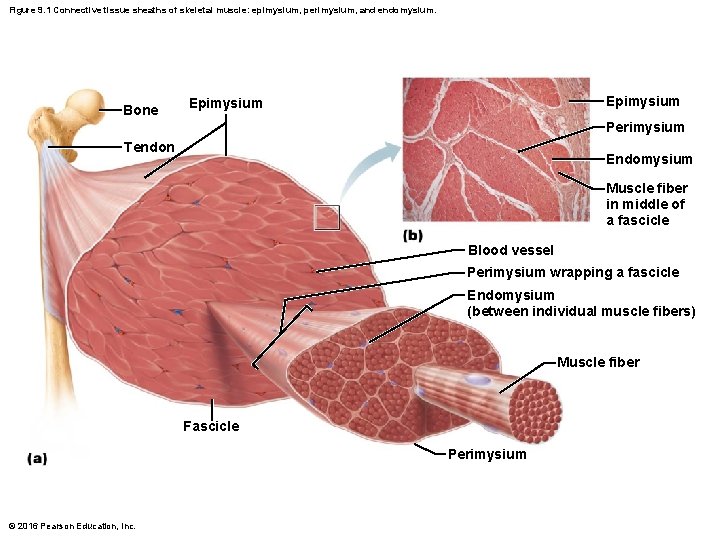

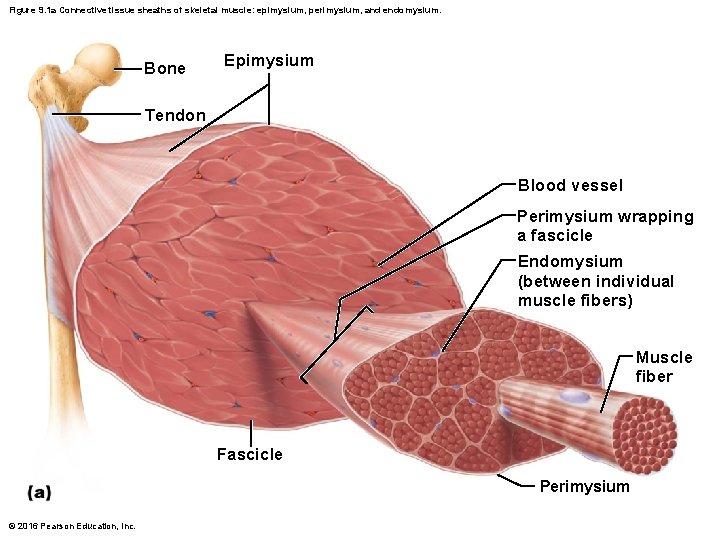

Figure 9. 1 Connective tissue sheaths of skeletal muscle: epimysium, perimysium, and endomysium. Bone Epimysium Perimysium Tendon Endomysium Muscle fiber in middle of a fascicle Blood vessel Perimysium wrapping a fascicle Endomysium (between individual muscle fibers) Muscle fiber Fascicle Perimysium © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Figure 9. 1 a Connective tissue sheaths of skeletal muscle: epimysium, perimysium, and endomysium. Bone Epimysium Tendon Blood vessel Perimysium wrapping a fascicle Endomysium (between individual muscle fibers) Muscle fiber Fascicle Perimysium © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

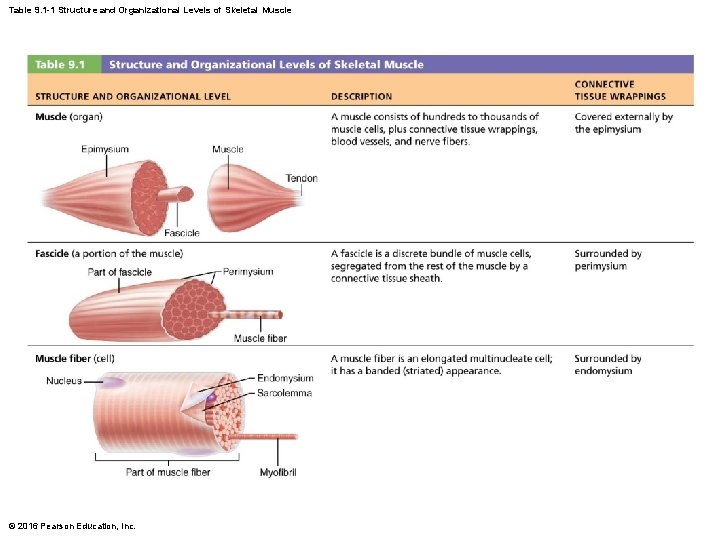

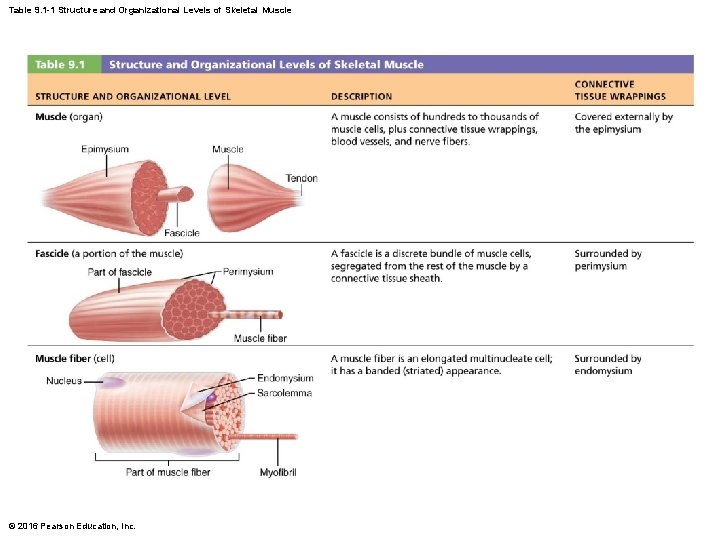

Table 9. 1 -1 Structure and Organizational Levels of Skeletal Muscle © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

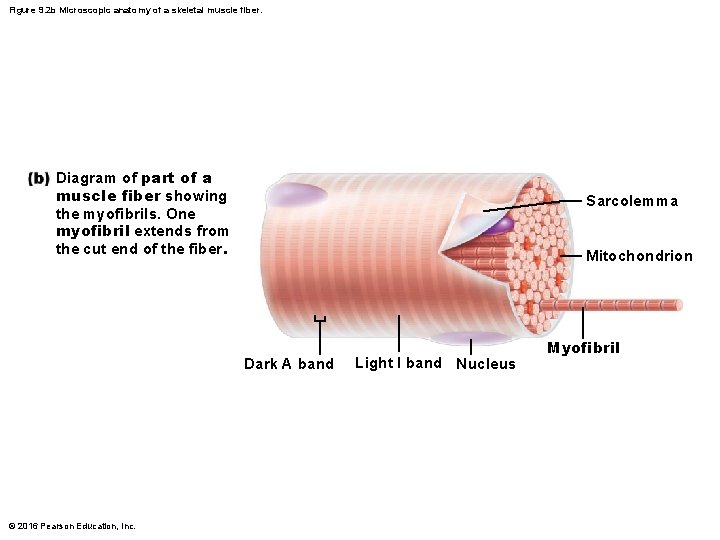

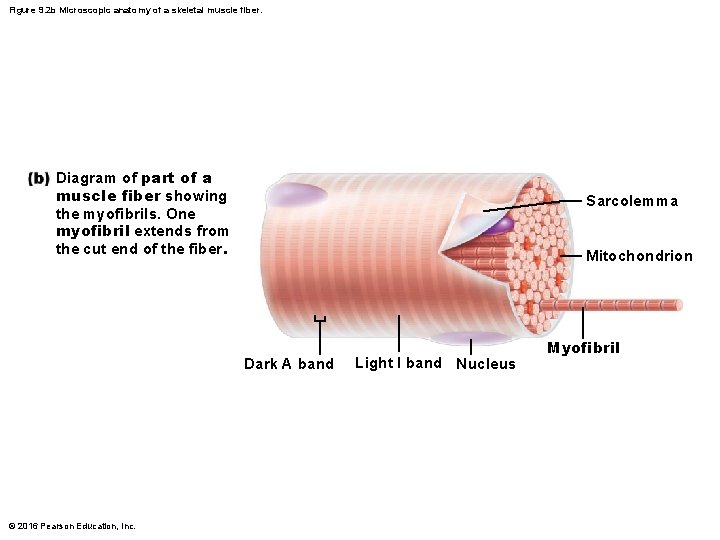

Figure 9. 2 b Microscopic anatomy of a skeletal muscle fiber. Diagram of part of a muscle fiber showing the myofibrils. One myofibril extends from the cut end of the fiber. Sarcolemma Mitochondrion Dark A band © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. Light I band Nucleus Myofibril

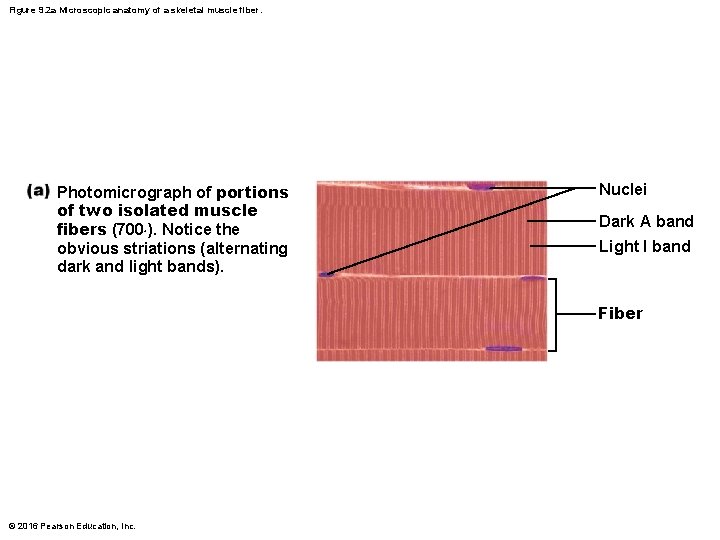

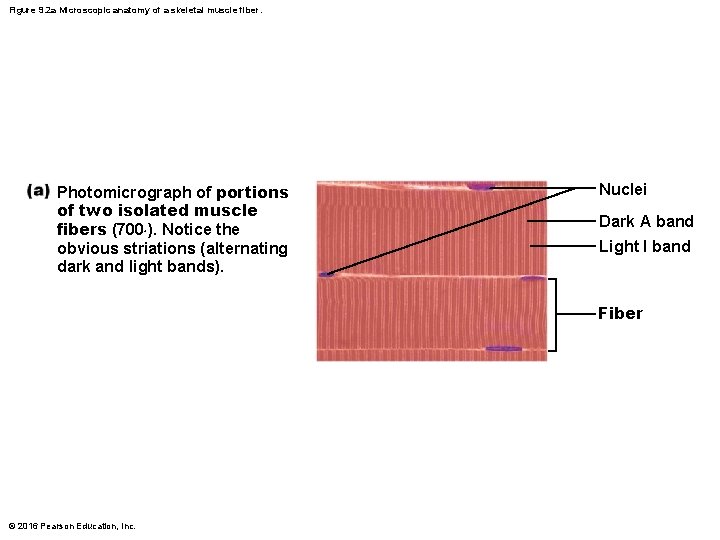

Figure 9. 2 a Microscopic anatomy of a skeletal muscle fiber. Photomicrograph of portions of two isolated muscle fibers (700×). Notice the obvious striations (alternating dark and light bands). Nuclei Dark A band Light I band Fiber © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

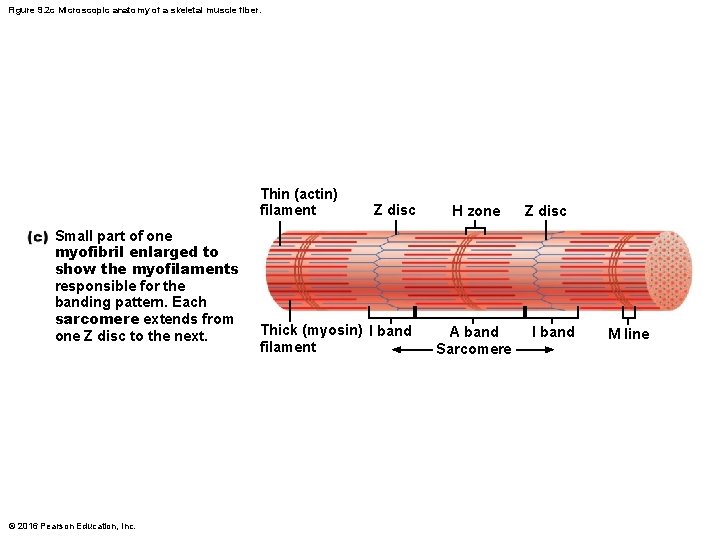

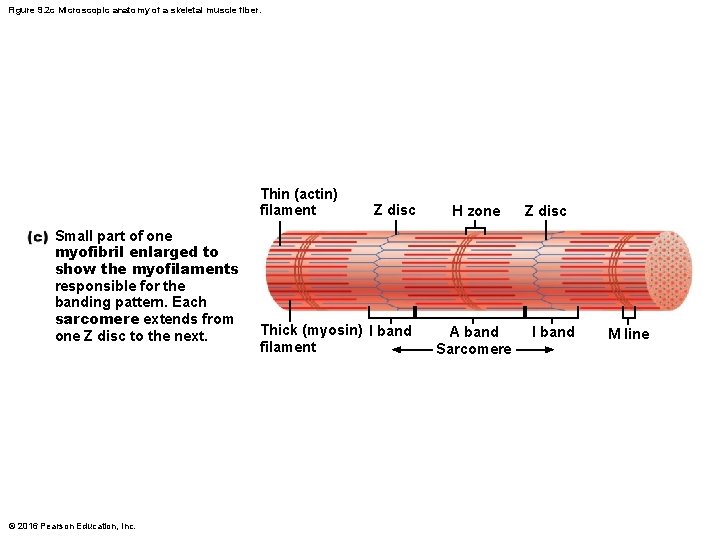

Figure 9. 2 c Microscopic anatomy of a skeletal muscle fiber. Thin (actin) filament Small part of one myofibril enlarged to show the myofilaments responsible for the banding pattern. Each sarcomere extends from one Z disc to the next. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. Z disc Thick (myosin) I band filament H zone A band Sarcomere Z disc I band M line

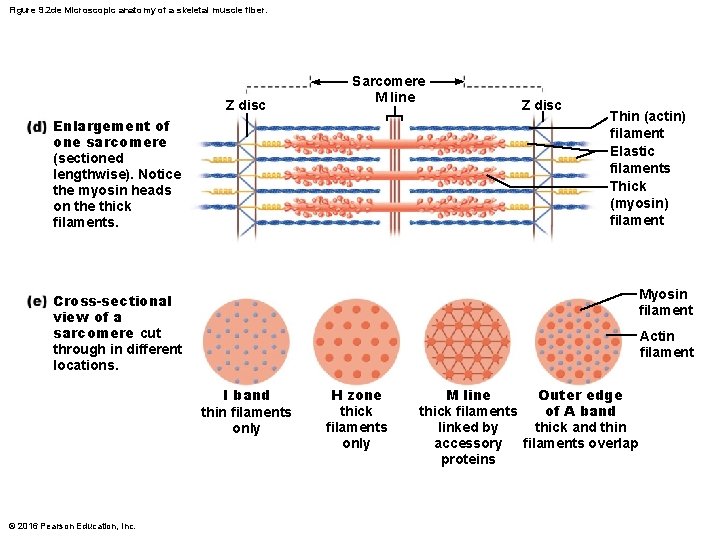

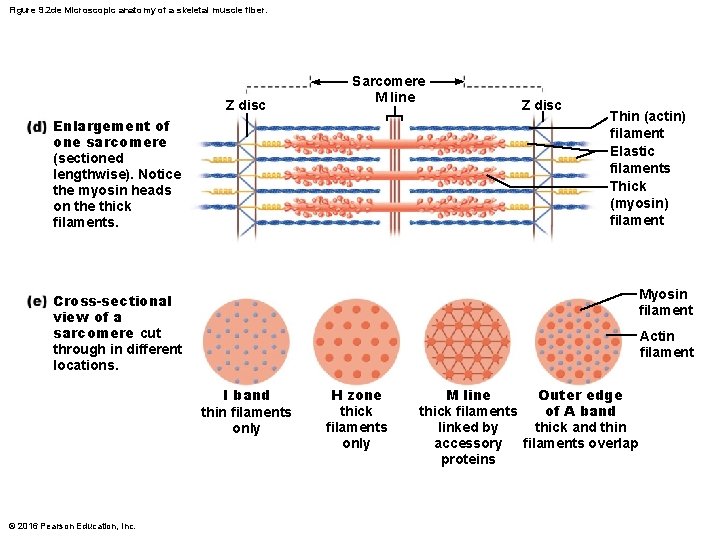

Figure 9. 2 de Microscopic anatomy of a skeletal muscle fiber. Z disc Sarcomere M line Enlargement of one sarcomere (sectioned lengthwise). Notice the myosin heads on the thick filaments. Z disc Thin (actin) filament Elastic filaments Thick (myosin) filament Myosin filament Cross-sectional view of a sarcomere cut through in different locations. Actin filament I band thin filaments only © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. H zone thick filaments only M line Outer edge of A band thick filaments linked by thick and thin accessory filaments overlap proteins

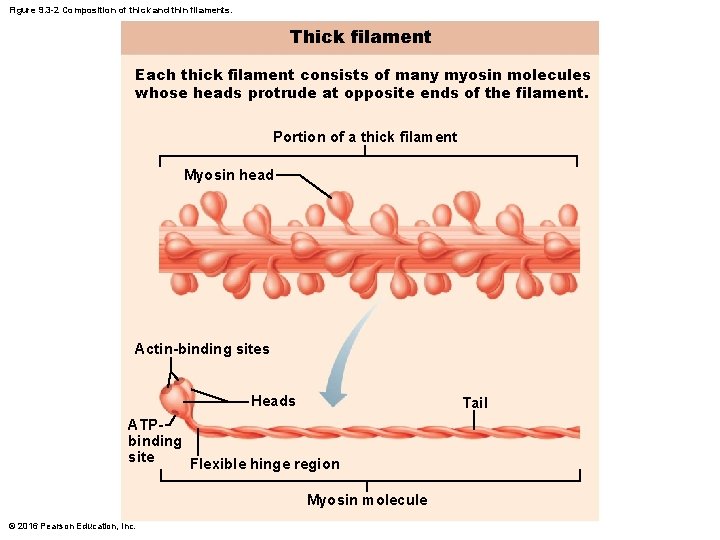

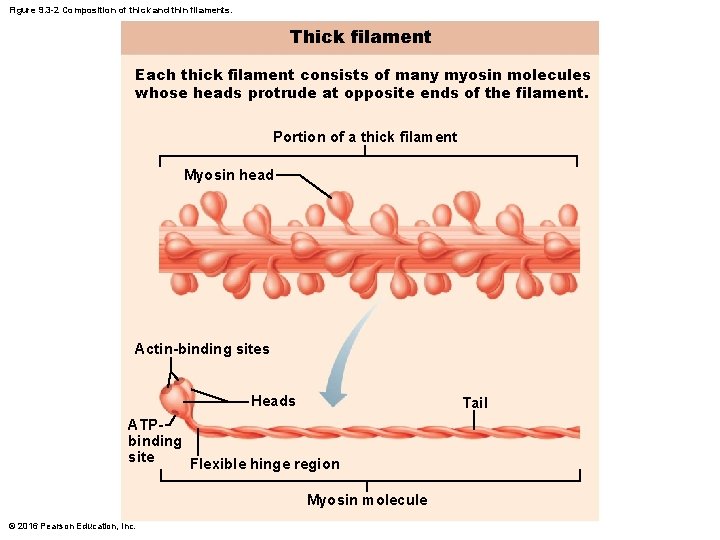

Figure 9. 3 -2 Composition of thick and thin filaments. Thick filament Each thick filament consists of many myosin molecules whose heads protrude at opposite ends of the filament. Portion of a thick filament Myosin head Actin-binding sites Heads Tail ATPbinding site Flexible hinge region Myosin molecule © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

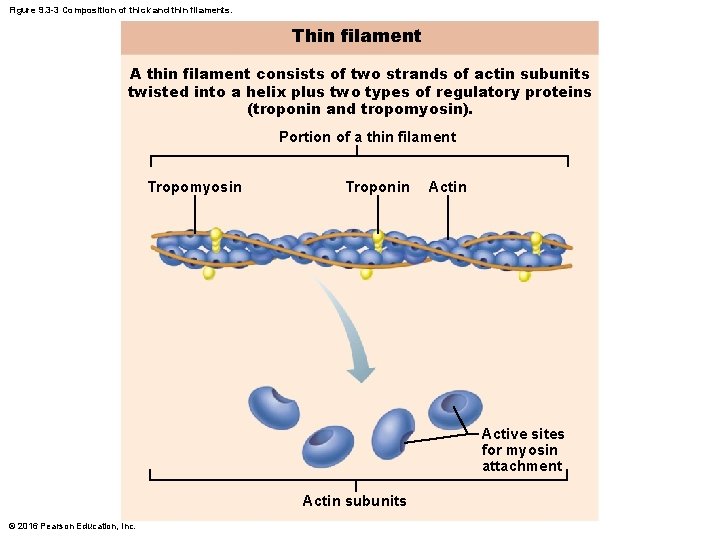

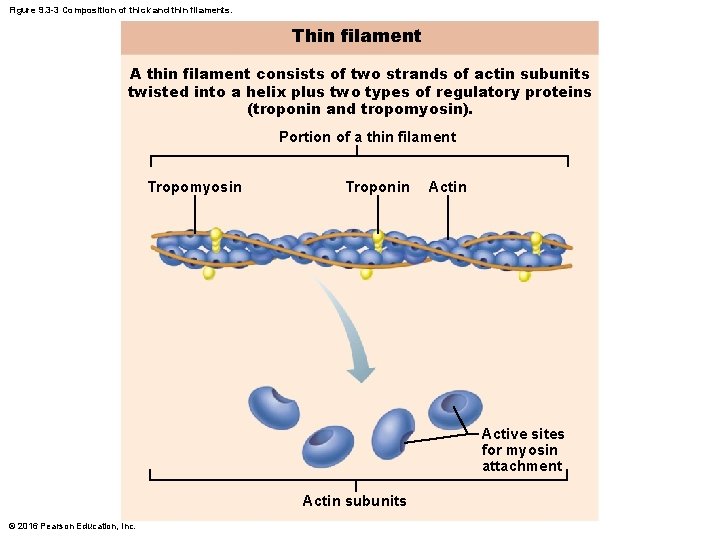

Figure 9. 3 -3 Composition of thick and thin filaments. Thin filament A thin filament consists of two strands of actin subunits twisted into a helix plus two types of regulatory proteins (troponin and tropomyosin). Portion of a thin filament Tropomyosin Troponin Active sites for myosin attachment Actin subunits © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Figure 9. 5 Relationship of the sarcoplasmic reticulum and T tubules to myofibrils of skeletal muscle. Part of a skeletal muscle fiber (cell) I band A band I band Z disc H zone Z disc M line Myofibril Sarcolemma Triad: • T tubule • Terminal cisterns of the SR (2) Tubules of the SR Myofibrils Mitochondria © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

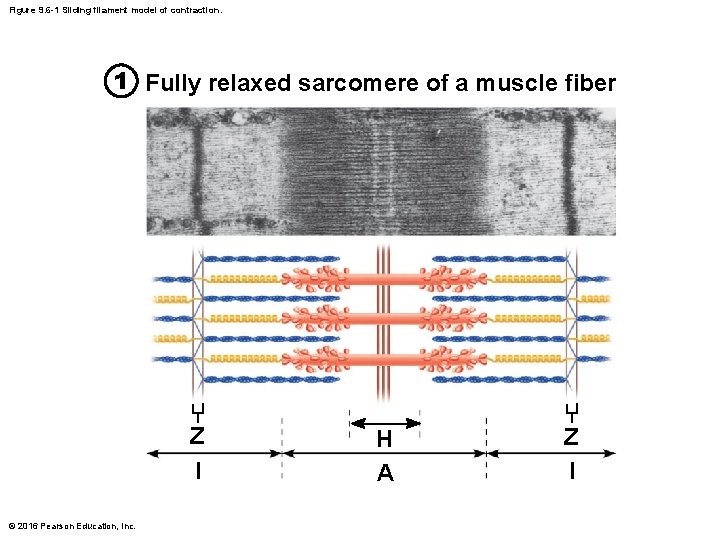

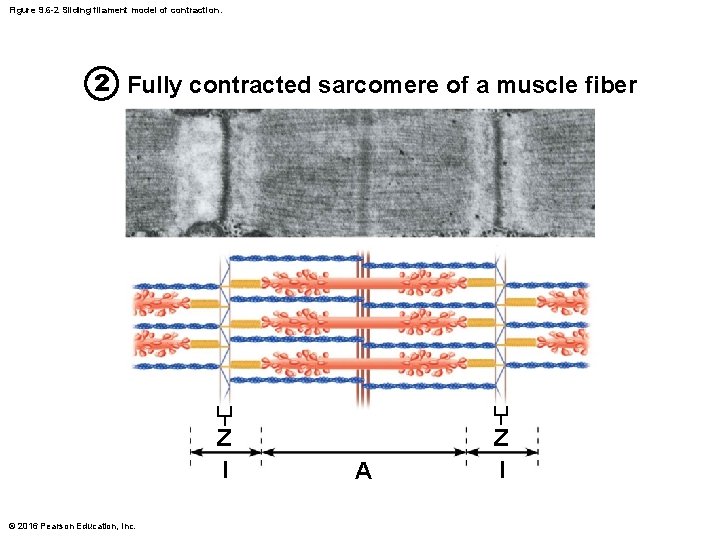

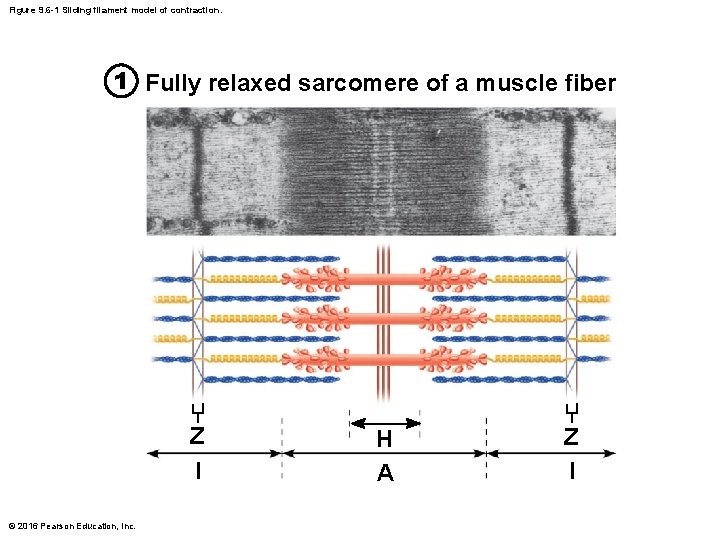

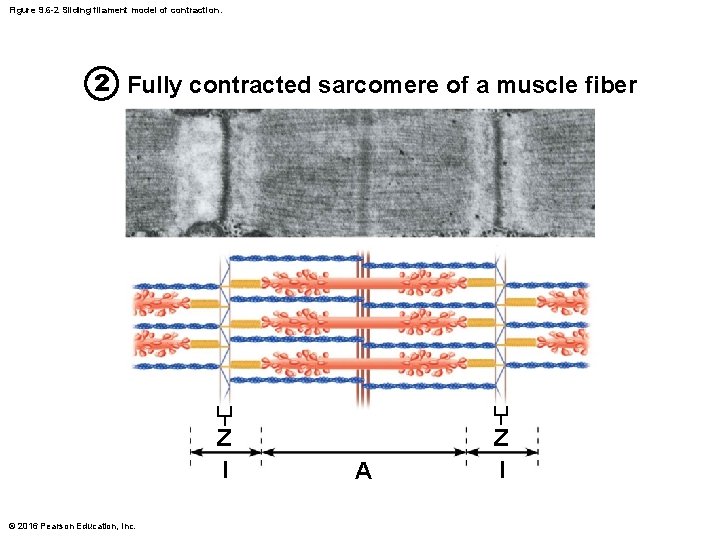

Figure 9. 6 -1 Sliding filament model of contraction. 1 Fully relaxed sarcomere of a muscle fiber Z l © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. H A Z l

Figure 9. 6 -2 Sliding filament model of contraction. 2 Fully contracted sarcomere of a muscle fiber Z l © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. A Z l

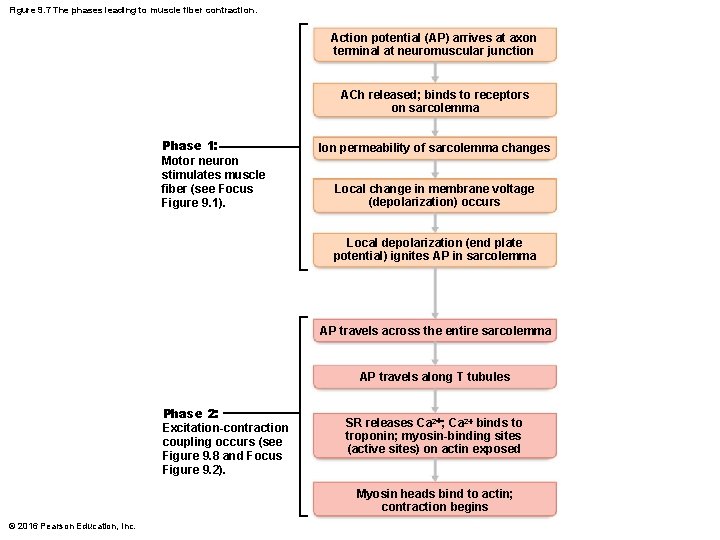

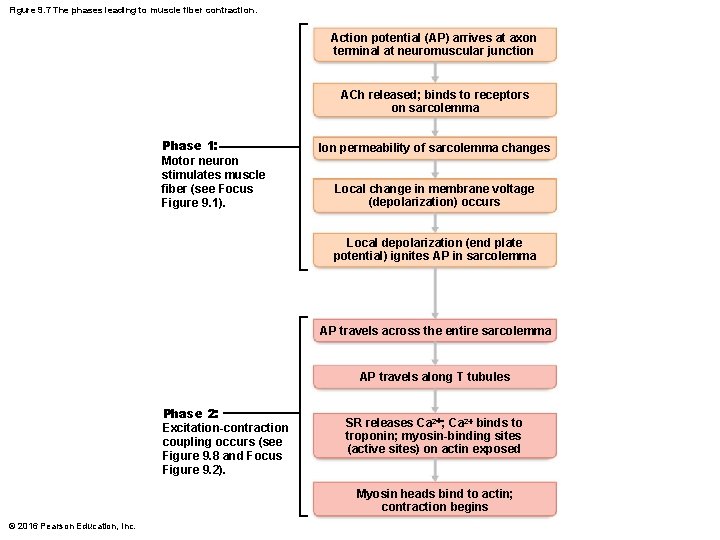

Figure 9. 7 The phases leading to muscle fiber contraction. Action potential (AP) arrives at axon terminal at neuromuscular junction ACh released; binds to receptors on sarcolemma Phase 1: Motor neuron stimulates muscle fiber (see Focus Figure 9. 1). Ion permeability of sarcolemma changes Local change in membrane voltage (depolarization) occurs Local depolarization (end plate potential) ignites AP in sarcolemma AP travels across the entire sarcolemma AP travels along T tubules Phase 2: Excitation-contraction coupling occurs (see Figure 9. 8 and Focus Figure 9. 2). SR releases Ca 2+; Ca 2+ binds to troponin; myosin-binding sites (active sites) on actin exposed Myosin heads bind to actin; contraction begins © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

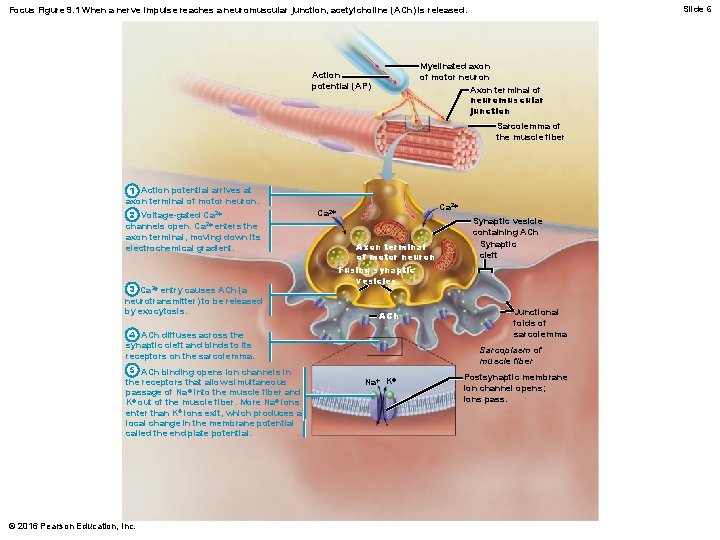

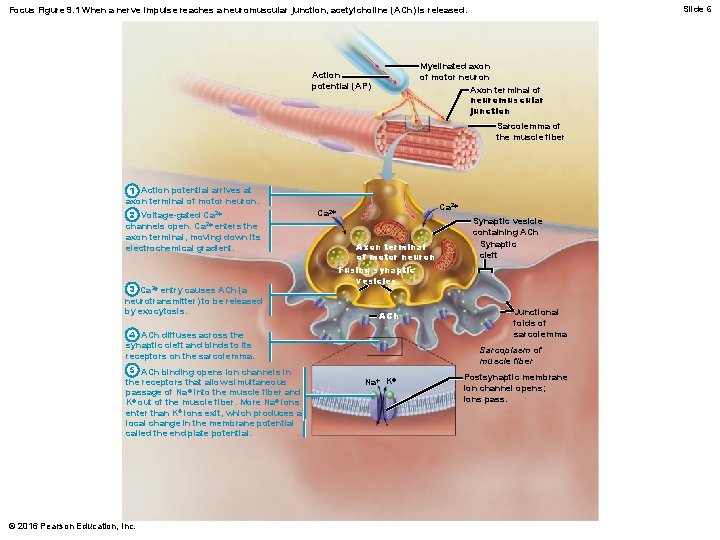

Slide 6 Focus Figure 9. 1 When a nerve impulse reaches a neuromuscular junction, acetylcholine (ACh) is released. Myelinated axon of motor neuron Axon terminal of neuromuscular junction Action potential (AP) Sarcolemma of the muscle fiber 1 Action potential arrives at axon terminal of motor neuron. 2 Voltage-gated Ca 2+ channels open. Ca 2+ enters the axon terminal, moving down its electrochemical gradient. 3 Ca 2+ entry causes ACh (a neurotransmitter) to be released by exocytosis. Ca 2+ Axon terminal of motor neuron Fusing synaptic vesicles ACh 4 ACh diffuses across the synaptic cleft and binds to its receptors on the sarcolemma. 5 ACh binding opens ion channels in the receptors that allow simultaneous passage of Na + into the muscle fiber and K+ out of the muscle fiber. More Na+ ions enter than K+ ions exit, which produces a local change in the membrane potential called the end plate potential. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. Synaptic vesicle containing ACh Synaptic cleft Junctional folds of sarcolemma Sarcoplasm of muscle fiber Na+ K+ Postsynaptic membrane ion channel opens; ions pass.

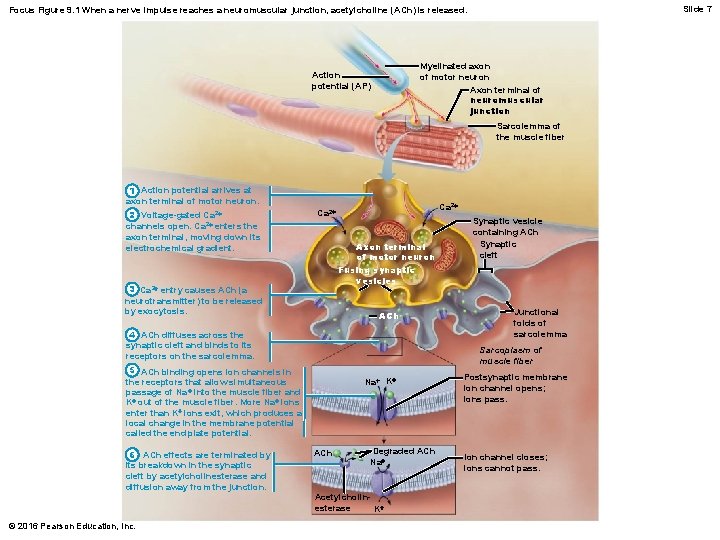

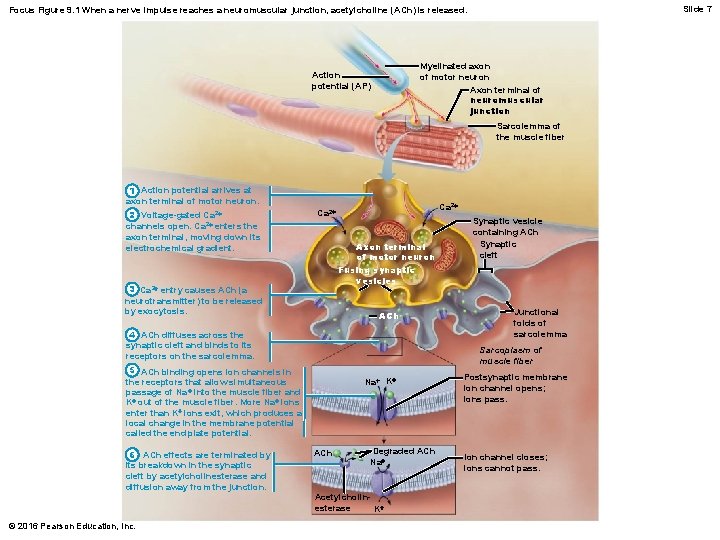

Slide 7 Focus Figure 9. 1 When a nerve impulse reaches a neuromuscular junction, acetylcholine (ACh) is released. Myelinated axon of motor neuron Axon terminal of neuromuscular junction Action potential (AP) Sarcolemma of the muscle fiber 1 Action potential arrives at axon terminal of motor neuron. 2 Voltage-gated Ca 2+ channels open. Ca 2+ enters the axon terminal, moving down its electrochemical gradient. Ca 2+ Axon terminal of motor neuron Fusing synaptic vesicles 3 Ca 2+ entry causes ACh (a neurotransmitter) to be released by exocytosis. ACh 4 ACh diffuses across the synaptic cleft and binds to its receptors on the sarcolemma. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. Junctional folds of sarcolemma Sarcoplasm of muscle fiber 5 ACh binding opens ion channels in the receptors that allow simultaneous passage of Na + into the muscle fiber and K+ out of the muscle fiber. More Na+ ions enter than K+ ions exit, which produces a local change in the membrane potential called the end plate potential. 6 ACh effects are terminated by its breakdown in the synaptic cleft by acetylcholinesterase and diffusion away from the junction. Synaptic vesicle containing ACh Synaptic cleft Na+ K+ ACh Degraded ACh Na+ Acetylcholinesterase K+ Postsynaptic membrane ion channel opens; ions pass. Ion channel closes; ions cannot pass.

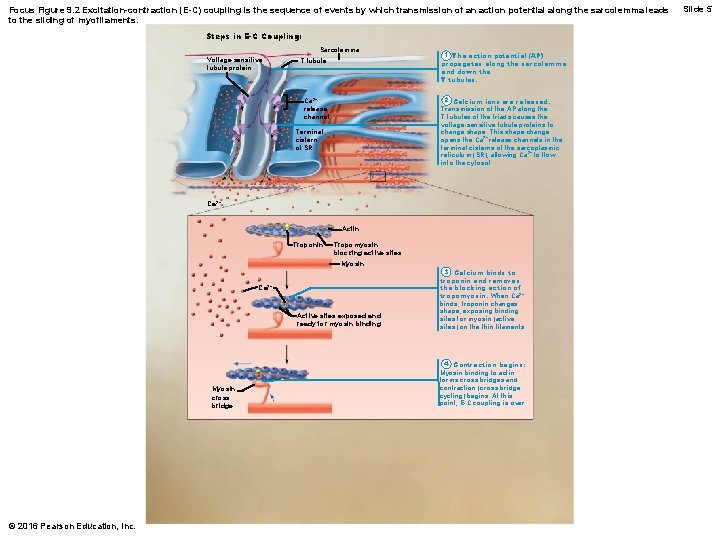

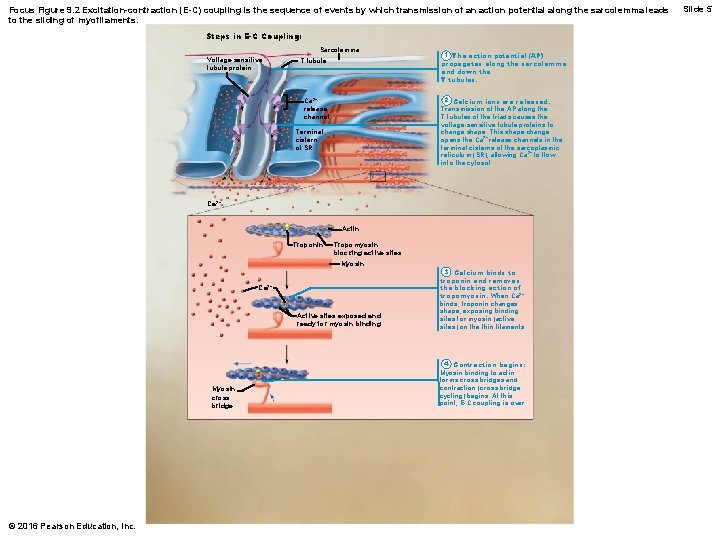

Focus Figure 9. 2 Excitation-contraction (E-C) coupling is the sequence of events by which transmission of an action potential along the sarcolemma leads to the sliding of myofilaments. Steps in E-C Coupling: Sarcolemma Voltage-sensitive tubule protein T tubule 1 The action potential (AP) propagates along the sarcolemma and down the T tubules. 2 Calcium ions are released. Transmission of the AP along the T tubules of the triads causes the voltage-sensitive tubule proteins to change shape. This shape change opens the Ca 2+ release channels in the terminal cisterns of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), allowing Ca 2+ to flow into the cytosol. Ca 2+ release channel Terminal cistern of SR Ca 2+ Actin Troponin Tropomyosin blocking active sites Myosin Ca 2+ Active sites exposed and ready for myosin binding Myosin cross bridge © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. 3 Calcium binds to troponin and removes the blocking action of tropomyosin. When Ca 2+ binds, troponin changes shape, exposing binding sites for myosin (active sites) on the thin filaments. 4 Contraction begins: Myosin binding to actin forms cross bridges and contraction (cross bridge cycling) begins. At this point, E-C coupling is over. Slide 5

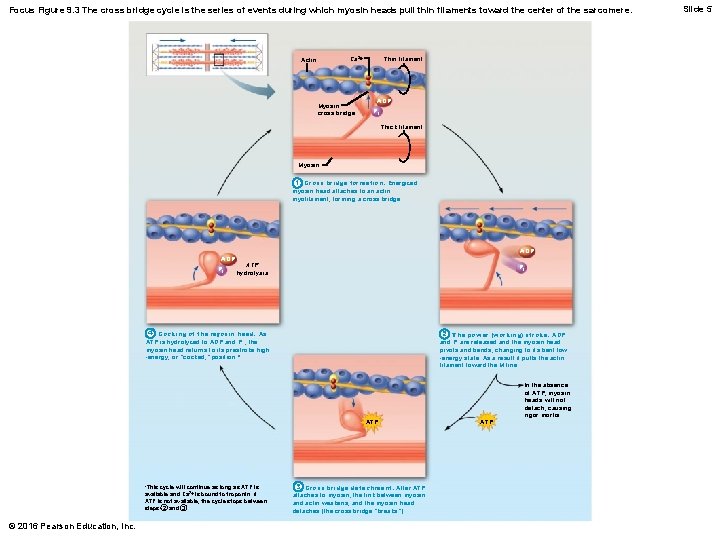

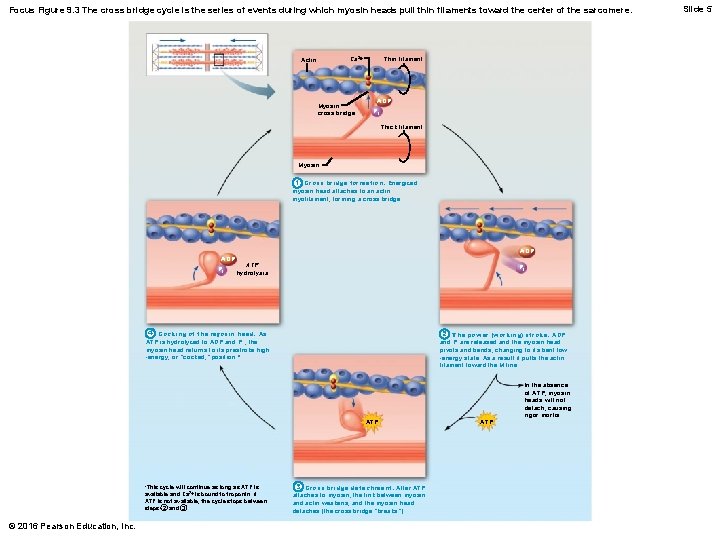

Focus Figure 9. 3 The cross bridge cycle is the series of events during which myosin heads pull thin filaments toward the center of the sarcomere. Thin filament Ca 2+ Actin Myosin cross bridge ADP Pi Thick filament Myosin 1 Cross bridge formation. Energized myosin head attaches to an actin myofilament, forming a cross bridge. ADP Pi ADP ATP hydrolysis Pi 4 Cocking of the myosin head. As ATP is hydrolyzed to ADP and P i , the myosin head returns to its prestroke high -energy, or “cocked, ” position. * 2 The power (working) stroke. ADP and Pi are released and the myosin head pivots and bends, changing to its bent low -energy state. As a result it pulls the actin filament toward the M line. ATP *This cycle will continue as long as ATP is available and Ca 2+ is bound to troponin. If ATP is not available, the cycle stops between steps 2 and 3. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. 3 Cross bridge detachment. After ATP attaches to myosin, the link between myosin and actin weakens, and the myosin head detaches (the cross bridge “breaks”). ATP In the absence of ATP, myosin heads will not detach, causing rigor mortis. Slide 5

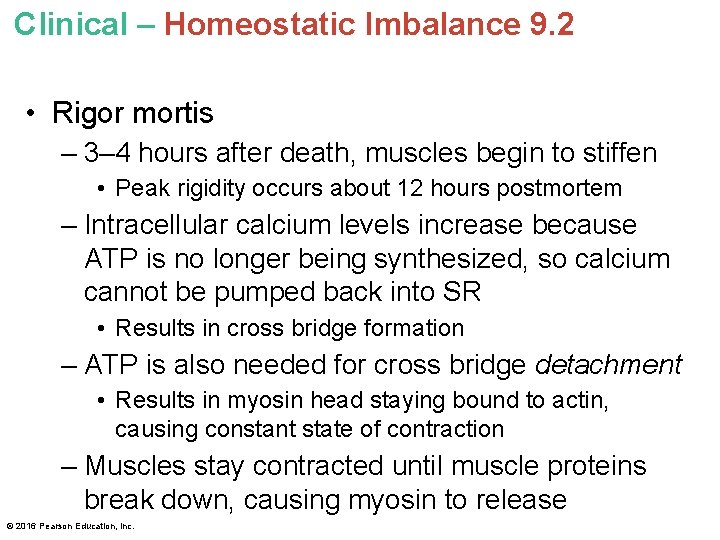

Clinical – Homeostatic Imbalance 9. 2 • Rigor mortis – 3– 4 hours after death, muscles begin to stiffen • Peak rigidity occurs about 12 hours postmortem – Intracellular calcium levels increase because ATP is no longer being synthesized, so calcium cannot be pumped back into SR • Results in cross bridge formation – ATP is also needed for cross bridge detachment • Results in myosin head staying bound to actin, causing constant state of contraction – Muscles stay contracted until muscle proteins break down, causing myosin to release © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

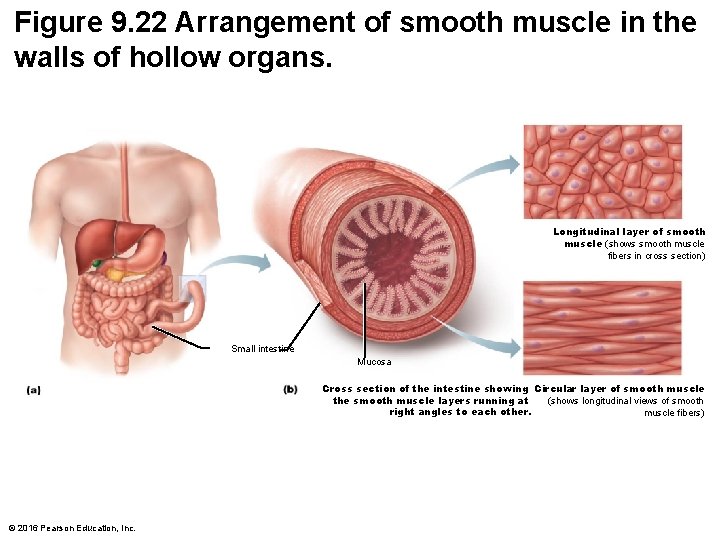

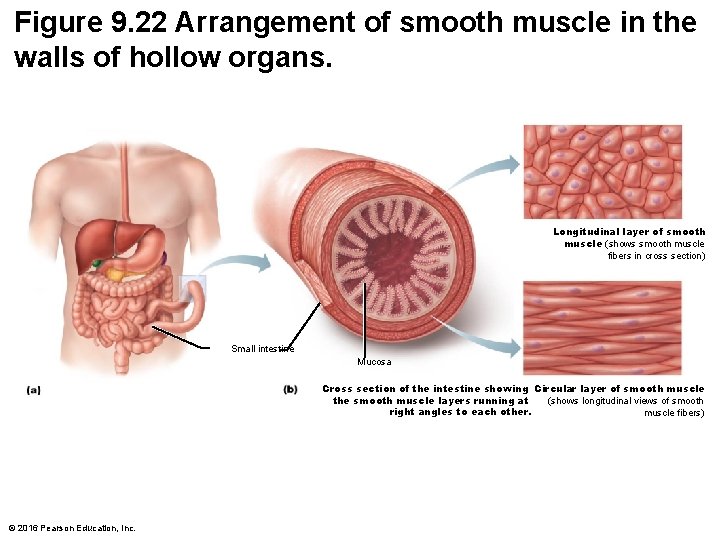

Figure 9. 22 Arrangement of smooth muscle in the walls of hollow organs. Longitudinal layer of smooth muscle (shows smooth muscle fibers in cross section) Small intestine Mucosa Cross section of the intestine showing Circular layer of smooth muscle the smooth muscle layers running at (shows longitudinal views of smooth right angles to each other. muscle fibers) © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

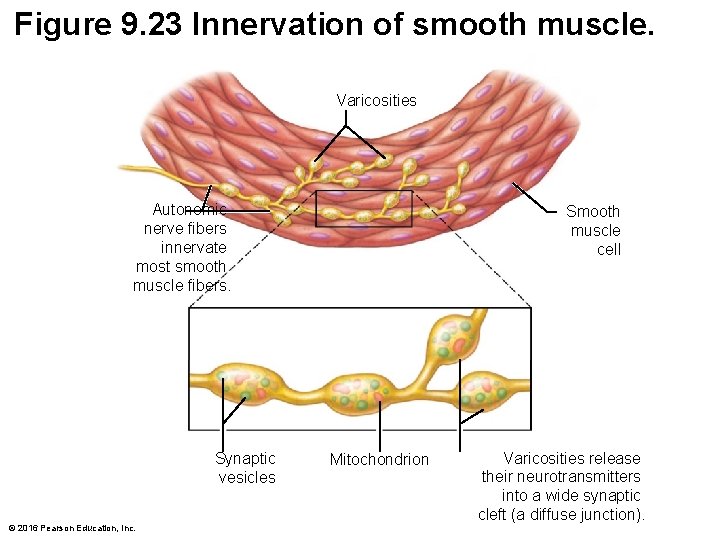

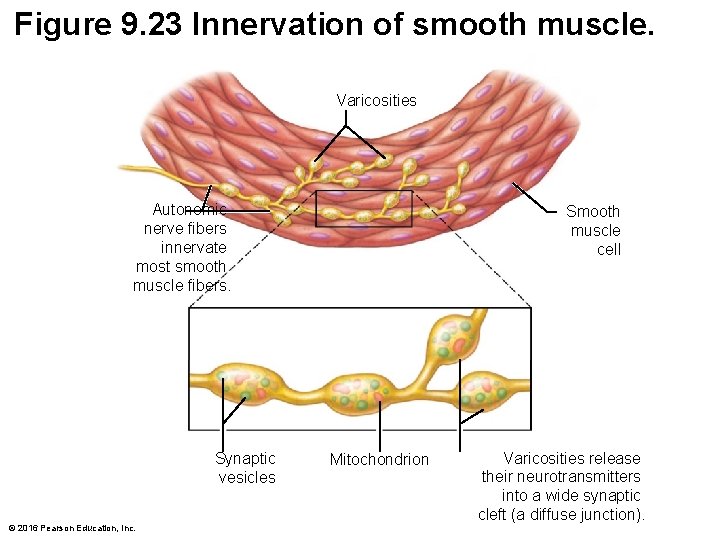

Figure 9. 23 Innervation of smooth muscle. Varicosities Autonomic nerve fibers innervate most smooth muscle fibers. Synaptic vesicles © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. Smooth muscle cell Mitochondrion Varicosities release their neurotransmitters into a wide synaptic cleft (a diffuse junction).

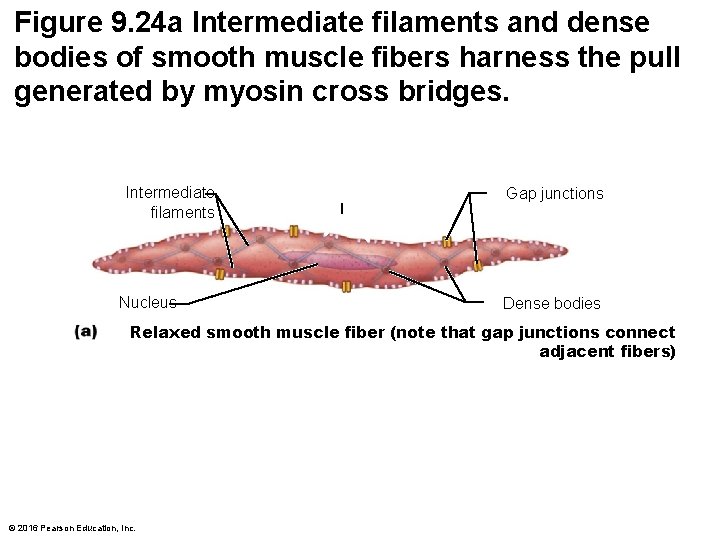

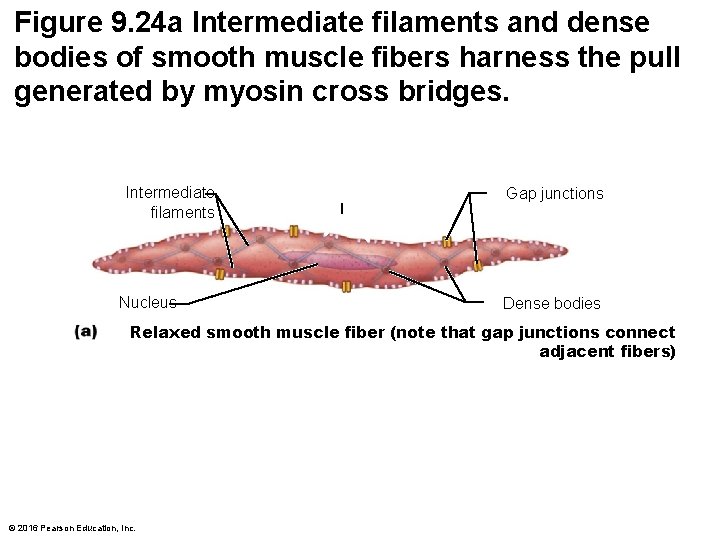

Figure 9. 24 a Intermediate filaments and dense bodies of smooth muscle fibers harness the pull generated by myosin cross bridges. Intermediate filaments Nucleus Gap junctions Dense bodies Relaxed smooth muscle fiber (note that gap junctions connect adjacent fibers) © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

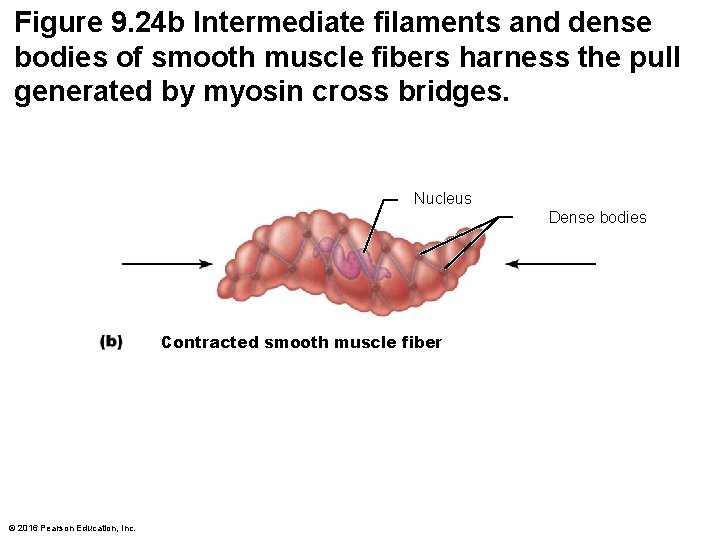

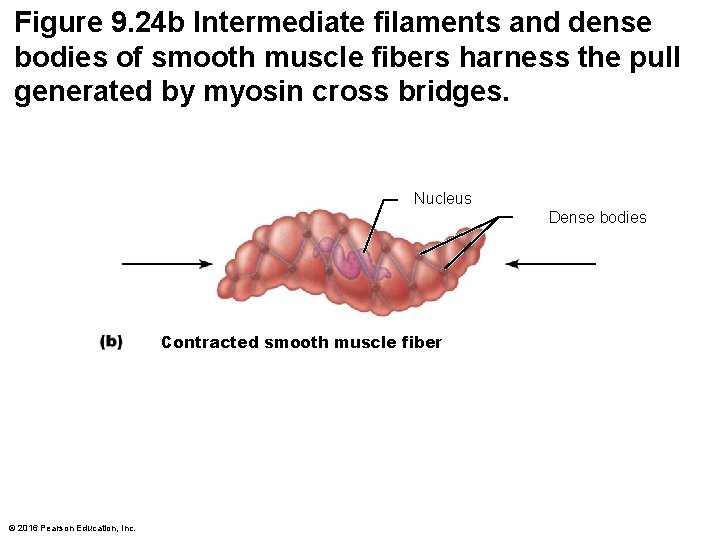

Figure 9. 24 b Intermediate filaments and dense bodies of smooth muscle fibers harness the pull generated by myosin cross bridges. Nucleus Dense bodies Contracted smooth muscle fiber © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Table 9. 3 -1 Comparison of Skeletal, Cardiac, and Smooth Muscle © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

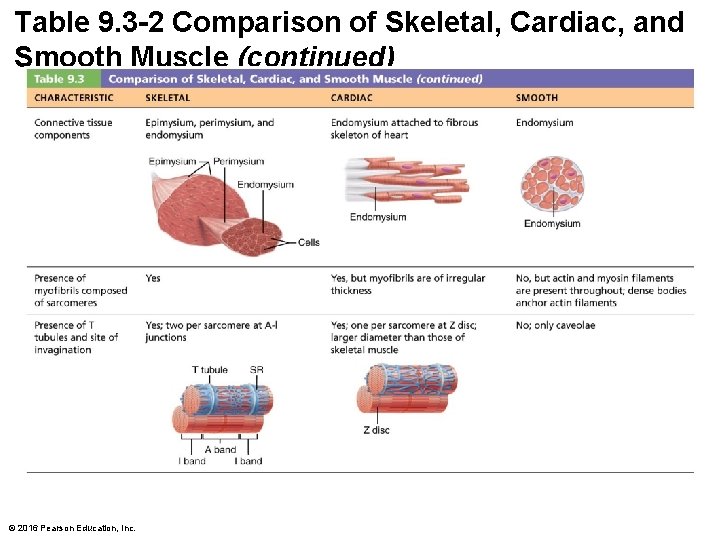

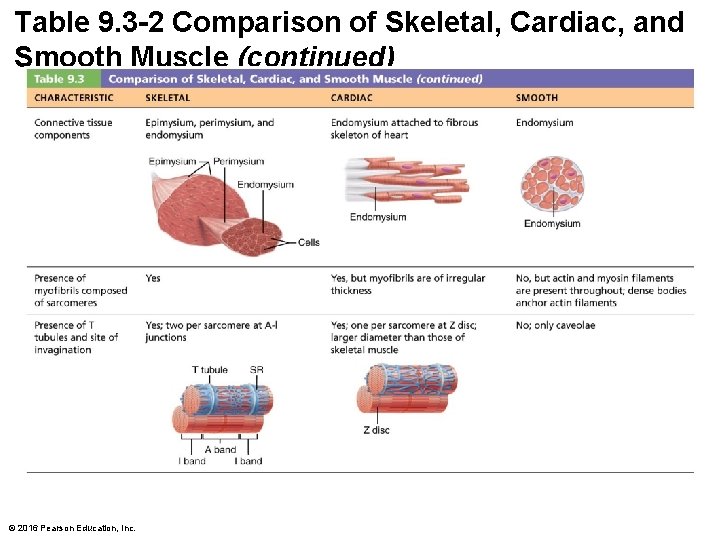

Table 9. 3 -2 Comparison of Skeletal, Cardiac, and Smooth Muscle (continued) © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

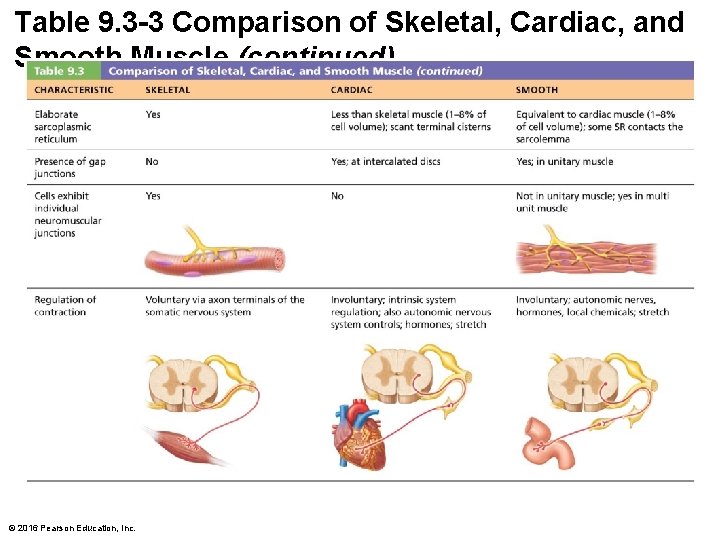

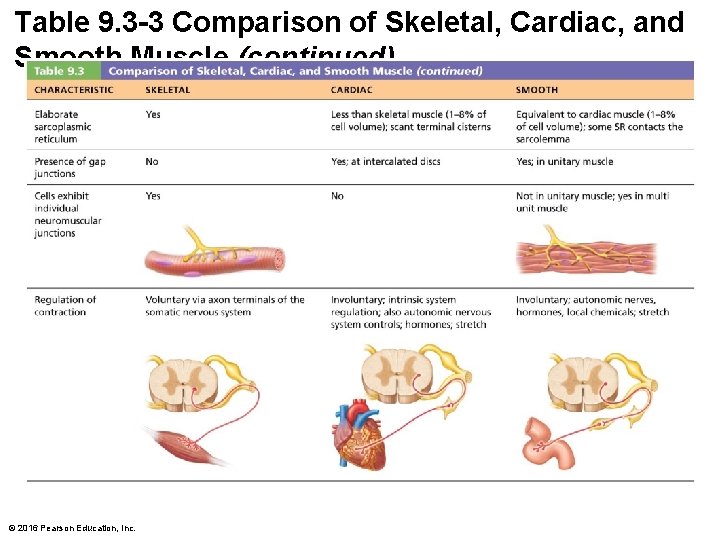

Table 9. 3 -3 Comparison of Skeletal, Cardiac, and Smooth Muscle (continued) © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

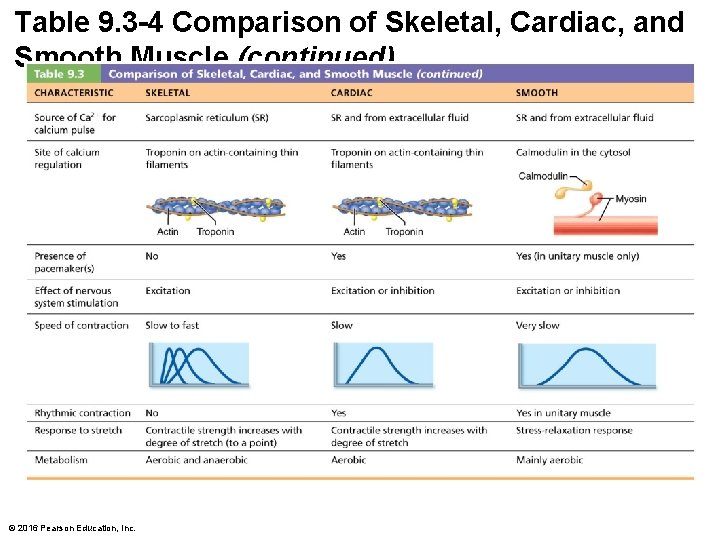

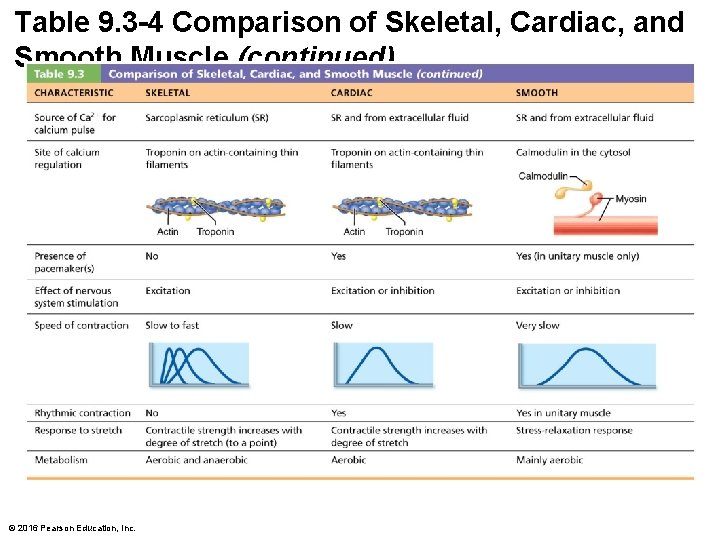

Table 9. 3 -4 Comparison of Skeletal, Cardiac, and Smooth Muscle (continued) © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Developmental Aspects of Muscle • All muscle tissues develop from embryonic myoblasts • Multinucleated skeletal muscle cells form by fusion of many myoblasts • Growth factor stimulates clustering of ACh receptors at neuromuscular junctions • Cardiac and smooth muscle myoblasts do not fuse, but develop gap junctions – Cardiac muscle cells start pumping when embryo is 3 weeks old © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

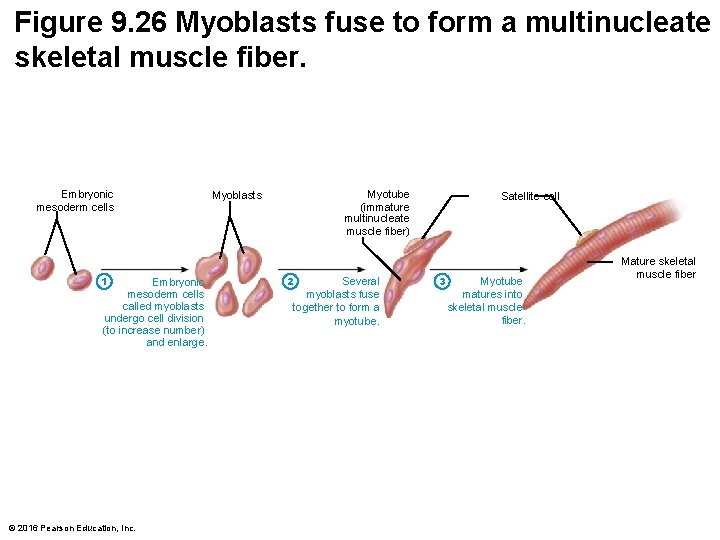

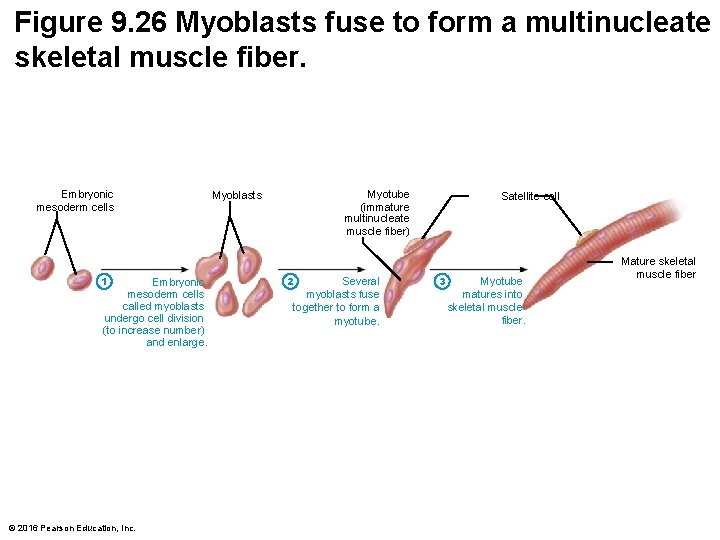

Figure 9. 26 Myoblasts fuse to form a multinucleate skeletal muscle fiber. Embryonic mesoderm cells 1 Embryonic mesoderm cells called myoblasts undergo cell division (to increase number) and enlarge. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. Myotube (immature multinucleate muscle fiber) Myoblasts 2 Several myoblasts fuse together to form a myotube. Satellite cell 3 Myotube matures into skeletal muscle fiber. Mature skeletal muscle fiber

Developmental Aspects of Muscle • Regeneration of muscle: – Myoblast-like skeletal muscle satellite cells have limited regenerative ability – Cardiomyocytes can divide at modest rate, but injured heart muscle is mostly replaced by connective tissue – Smooth muscle regenerates throughout life • Cardiac and skeletal muscle can lengthen and thicken in growing child – In adults, leads to hypertrophy © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Developmental Aspects of Muscle • Muscular development in infants reflects neuromuscular coordination – Development occurs head to toe, and proximal to distal • A baby can lift its head before it is able to walk • Peak natural neural control occurs by midadolescence – Athletics and training can continue to improve neuromuscular control © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Developmental Aspects of Muscle • Difference in muscle mass between sexes: – Female skeletal muscle makes up 36% of body mass – Male skeletal muscle makes up 42% of body mass, primarily as a result of testosterone • Males have greater ability to enlarge muscle fibers, also because of testosterone – Body strength per unit muscle mass is the same in both sexes © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Developmental Aspects of Muscle • Aging muscles: – With age, connective tissue increases, and muscle fibers decrease – By age 30, loss of muscle mass (sarcopenia) begins – Regular exercise reverses sarcopenia – Atherosclerosis may block distal arteries, leading to intermittent claudication (limping) and severe pain in leg muscles © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Clinical – Homeostatic Imbalance 9. 4 • Muscular dystrophy: group of inherited muscle -destroying diseases – Generally appear in childhood • Muscles enlarge as a result of fat and connective tissue deposits, but then atrophy and degenerate • Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is the most common and severe type – Caused by defective gene for dystrophin – Inherited, sex-linked trait, carried by females and expressed in males (1/3600) © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Clinical – Homeostatic Imbalance 9. 4 – Dystrophin is a cytoplasmic protein that links the cytoskeleton to the extracellular matrix, stabilizing the sarcolemma • Fragile sarcolemma tears during contractions, causing entry of excess Ca 2+ – Leads to damaged contractile fibers • Inflammatory cells accumulate • Muscle mass declines • Victims become clumsy and fall frequently – Usually appears between ages 2 and 7 © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Clinical – Homeostatic Imbalance 9. 4 – Currently no cure is known – Prednisone can improve muscle strength and function – Myoblast transfer therapy has been disappointing – Coaxing dystrophic muscles to produce more utrophin (protein similar to dystrophin) has been successful in mice – Viral gene therapy and infusion of stem cells with correct dystrophin genes show promise • Patients usually die of respiratory failure in their early 20 s © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.