Chapter 9 Nuclear Radiation 9 1 Natural Radioactivity

- Slides: 34

Chapter 9 Nuclear Radiation 9. 1 Natural Radioactivity Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. 1

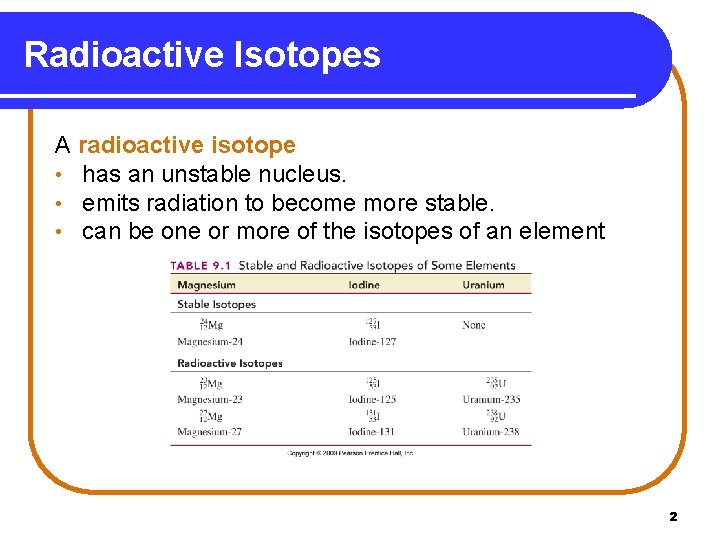

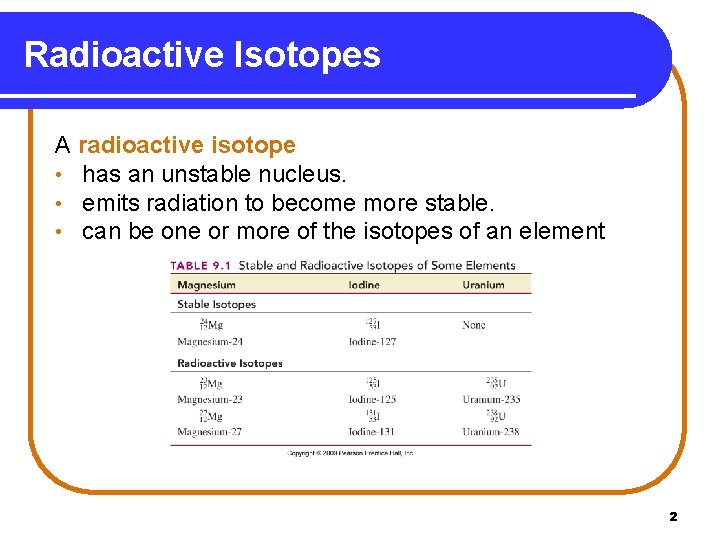

Radioactive Isotopes A radioactive isotope • has an unstable nucleus. • emits radiation to become more stable. • can be one or more of the isotopes of an element Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. 2

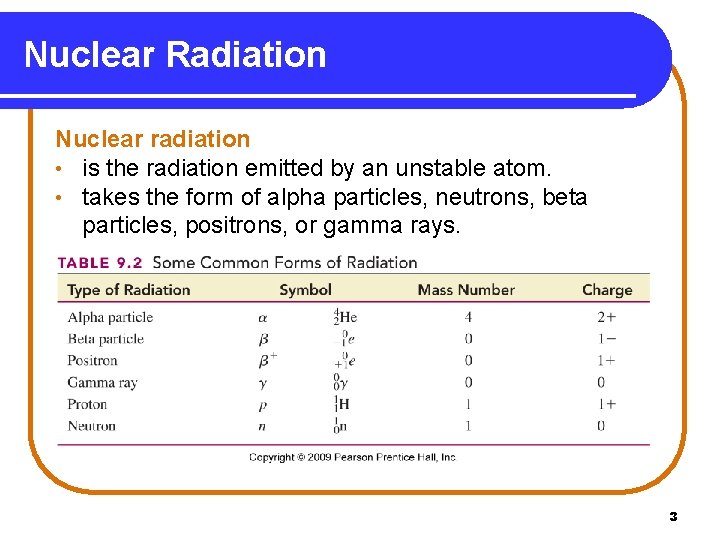

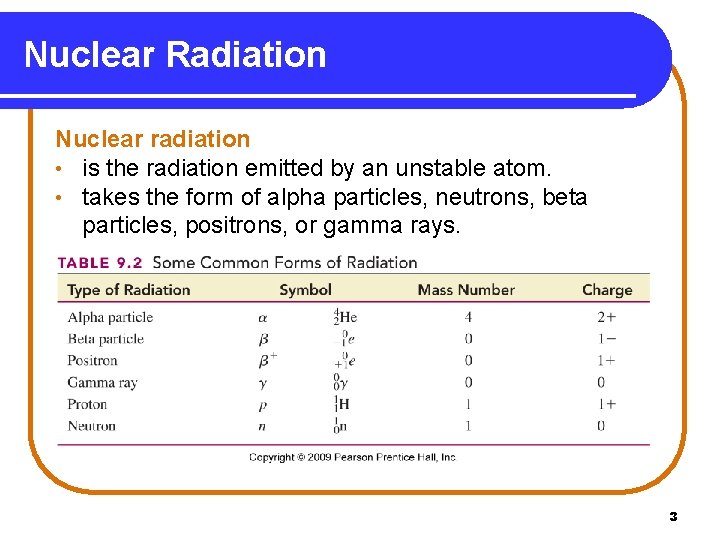

Nuclear Radiation Nuclear radiation • is the radiation emitted by an unstable atom. • takes the form of alpha particles, neutrons, beta particles, positrons, or gamma rays. Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. 3

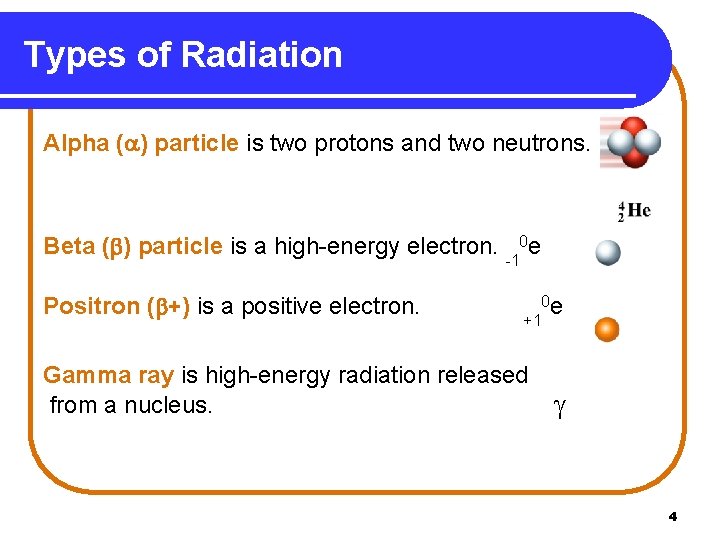

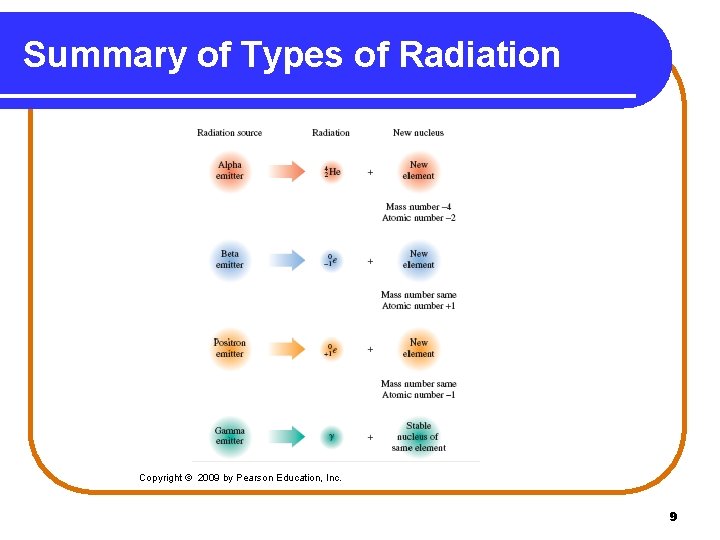

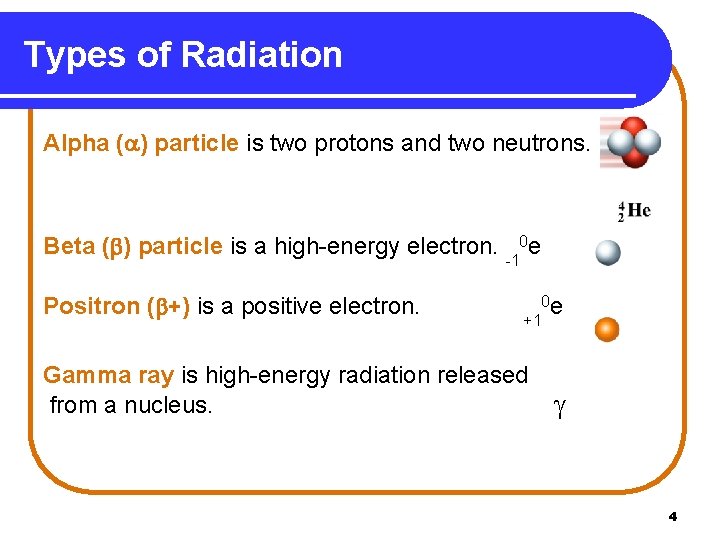

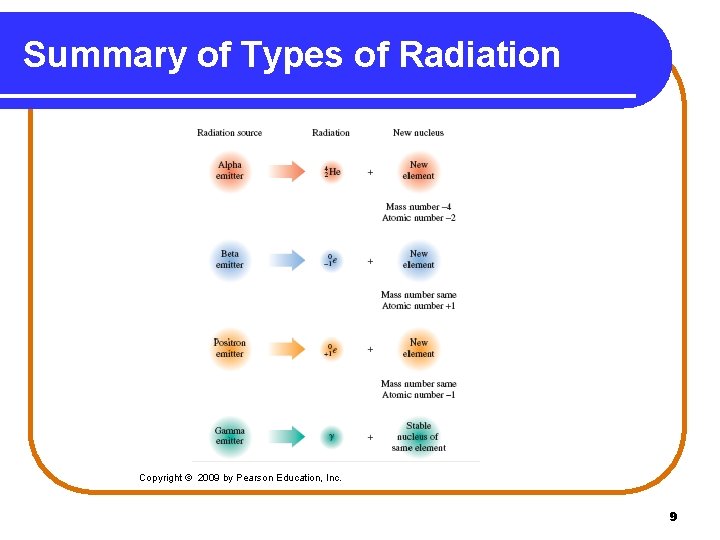

Types of Radiation Alpha ( ) particle is two protons and two neutrons. Beta ( ) particle is a high-energy electron. -10 e Positron ( +) is a positive electron. 0 e +1 Gamma ray is high-energy radiation released from a nucleus. 4

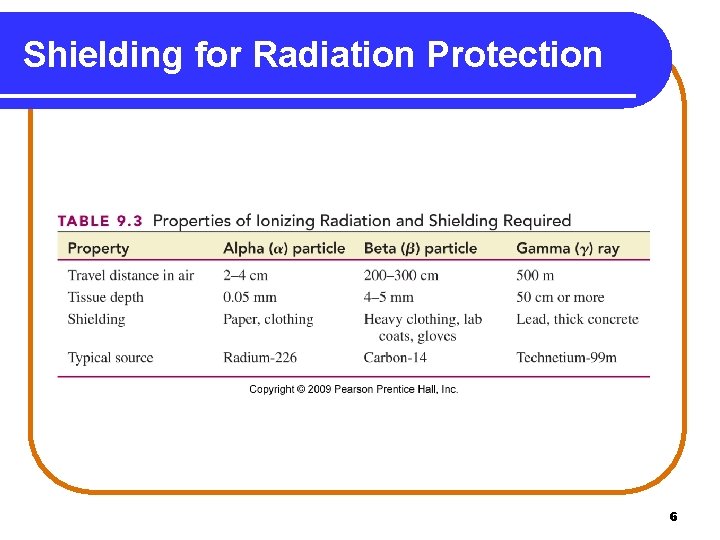

Radiation Protection Radiation protection requires • paper and clothing for alpha particles. • a lab coat or gloves for beta particles. • a lead shield or a thick concrete wall for gamma rays. • limiting the amount of time spent near a radioactive source. • increasing the distance from the source. Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. 5

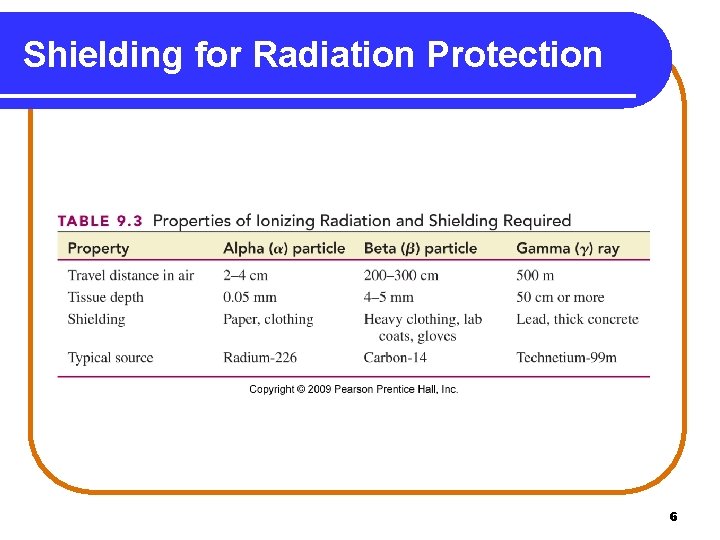

Shielding for Radiation Protection 6

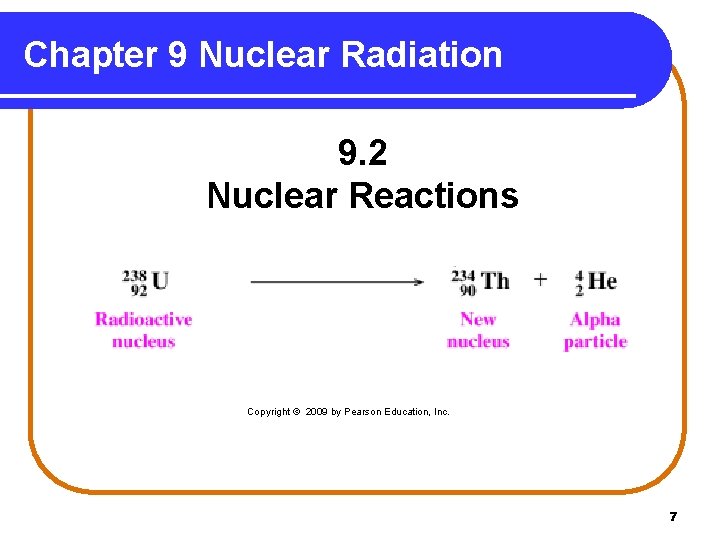

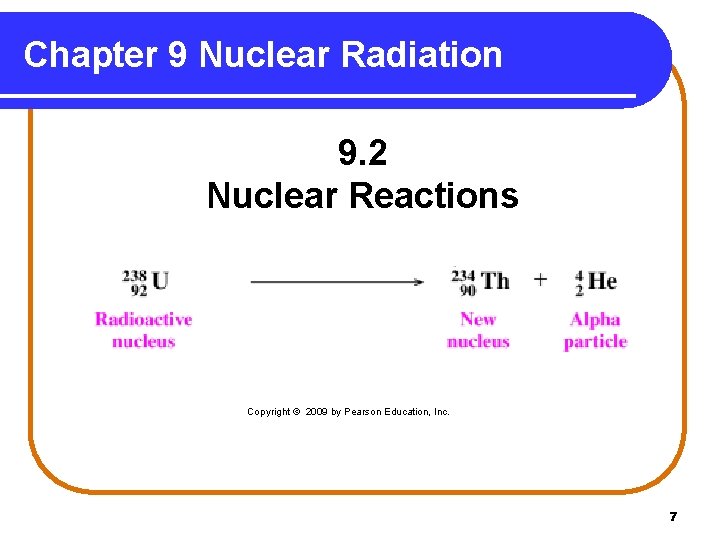

Chapter 9 Nuclear Radiation 9. 2 Nuclear Reactions Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. 7

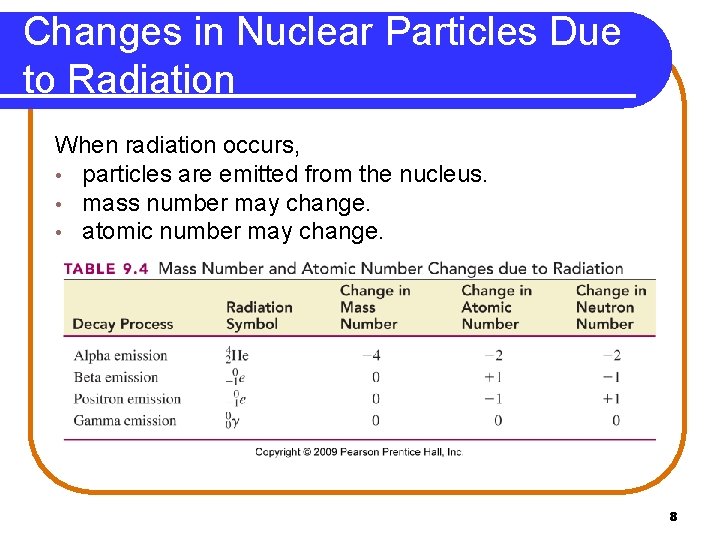

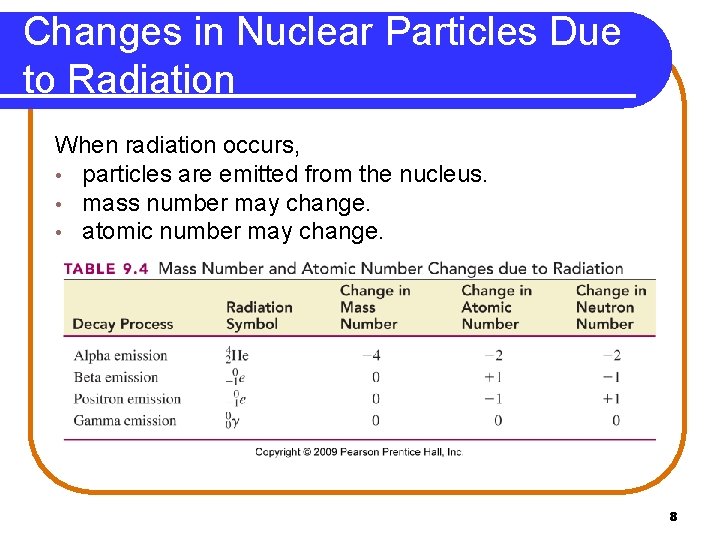

Changes in Nuclear Particles Due to Radiation When radiation occurs, • particles are emitted from the nucleus. • mass number may change. • atomic number may change. Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. 8

Summary of Types of Radiation Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. 9

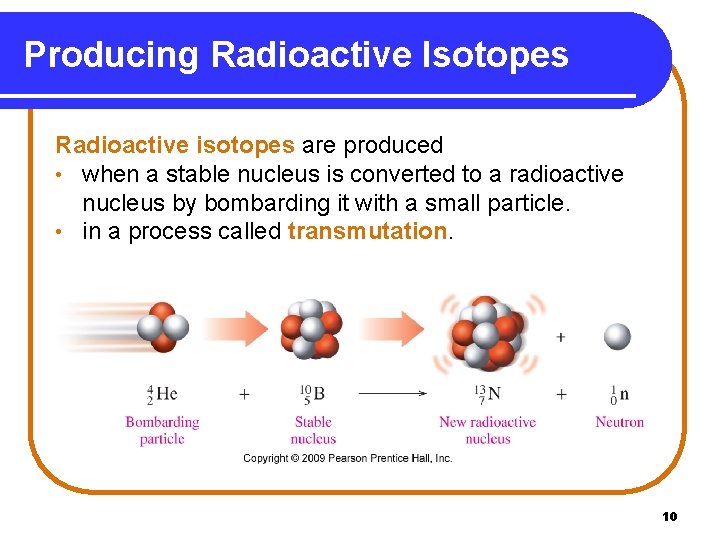

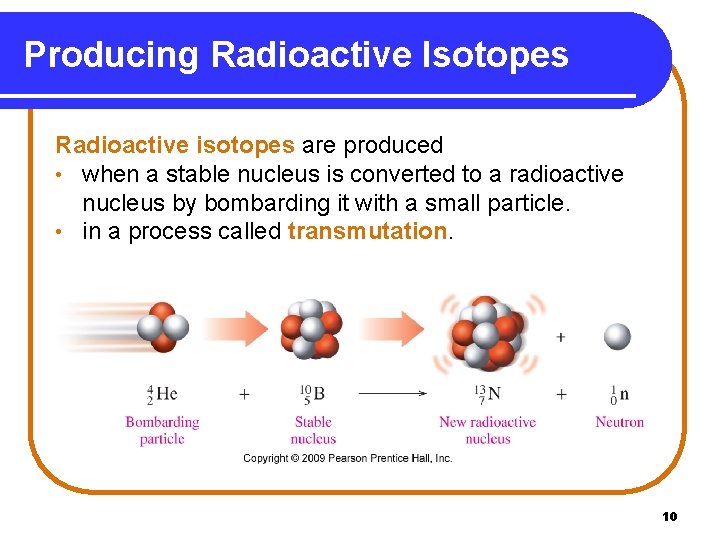

Producing Radioactive Isotopes Radioactive isotopes are produced • when a stable nucleus is converted to a radioactive nucleus by bombarding it with a small particle. • in a process called transmutation. Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. 10

Chapter 9 Nuclear Radiation 9. 3 Radiation Measurement Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. 11

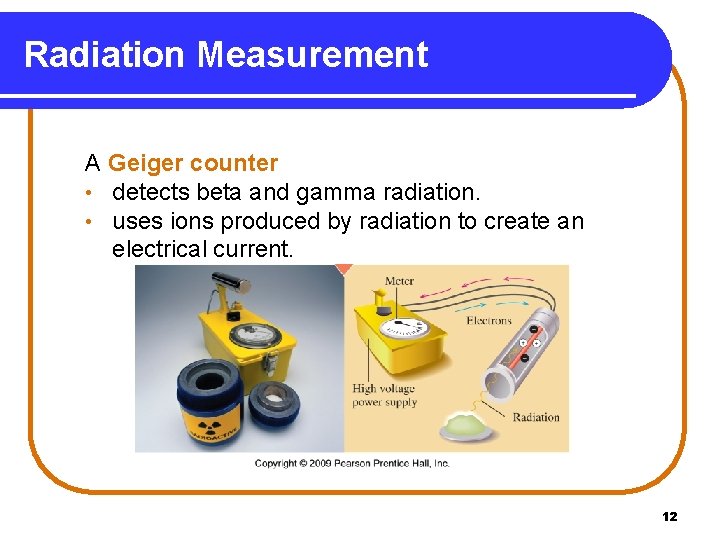

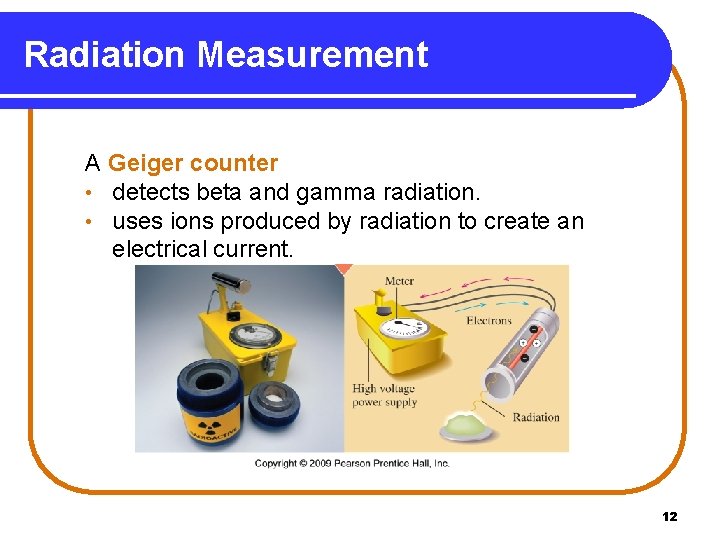

Radiation Measurement A Geiger counter • detects beta and gamma radiation. • uses ions produced by radiation to create an electrical current. Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. 12

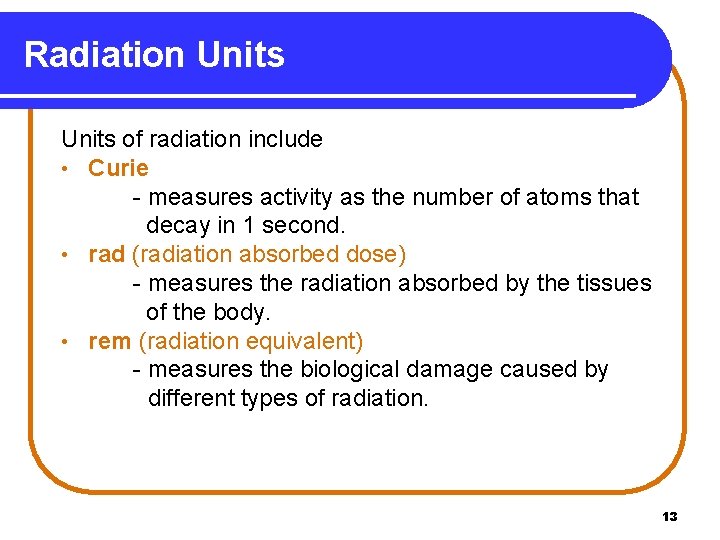

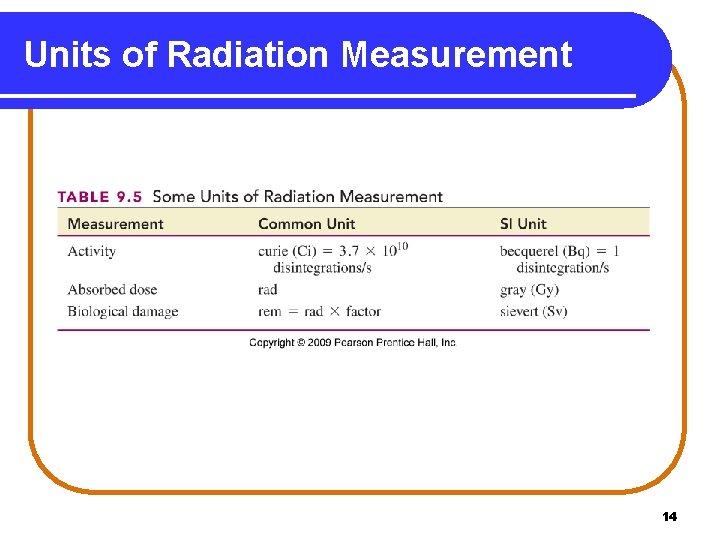

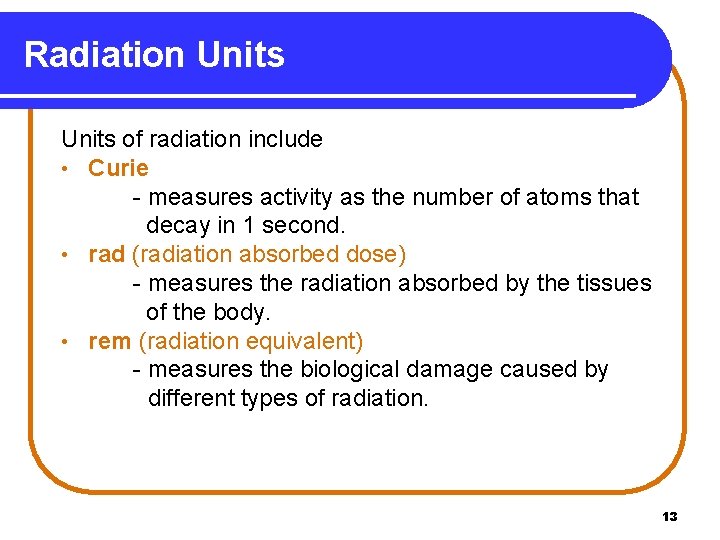

Radiation Units of radiation include • Curie - measures activity as the number of atoms that decay in 1 second. • rad (radiation absorbed dose) - measures the radiation absorbed by the tissues of the body. • rem (radiation equivalent) - measures the biological damage caused by different types of radiation. 13

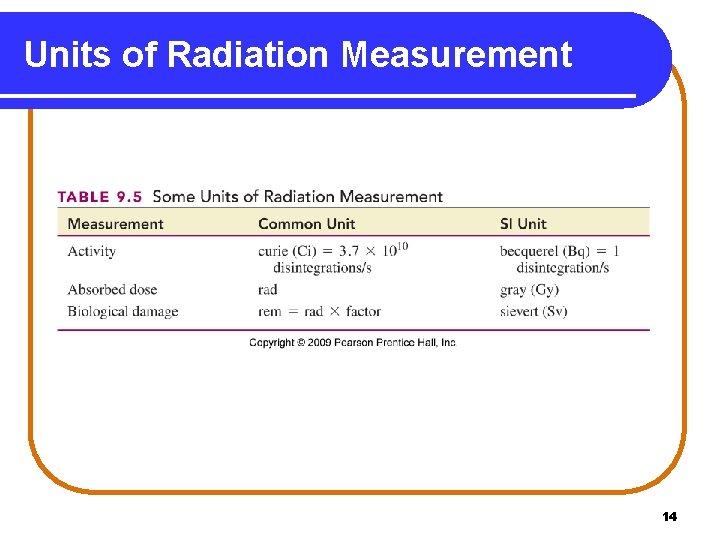

Units of Radiation Measurement 14

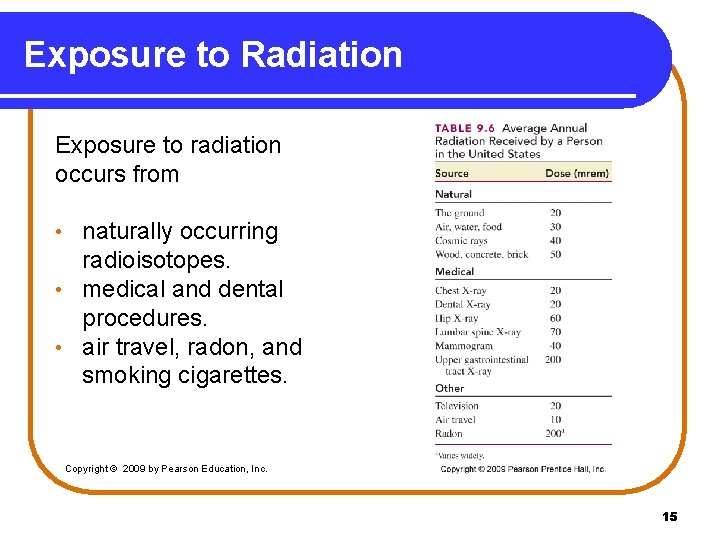

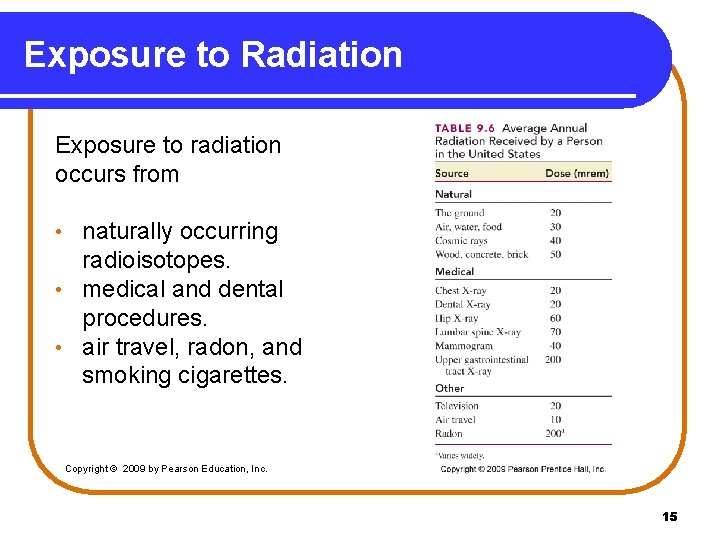

Exposure to Radiation Exposure to radiation occurs from naturally occurring radioisotopes. • medical and dental procedures. • air travel, radon, and smoking cigarettes. • Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. 15

Chapter 9 Nuclear Radiation 9. 4 Half-Life of a Radioisotope 9. 5 Medical Applications Using Radioactivity Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. 16

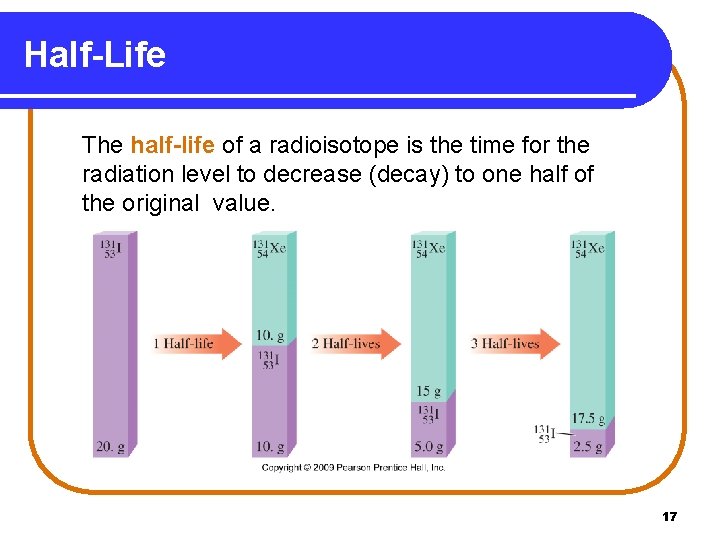

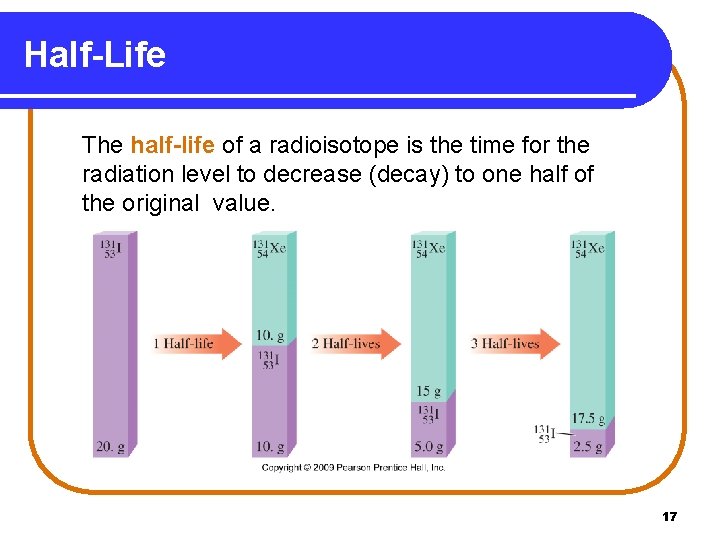

Half-Life The half-life of a radioisotope is the time for the radiation level to decrease (decay) to one half of the original value. Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. 17

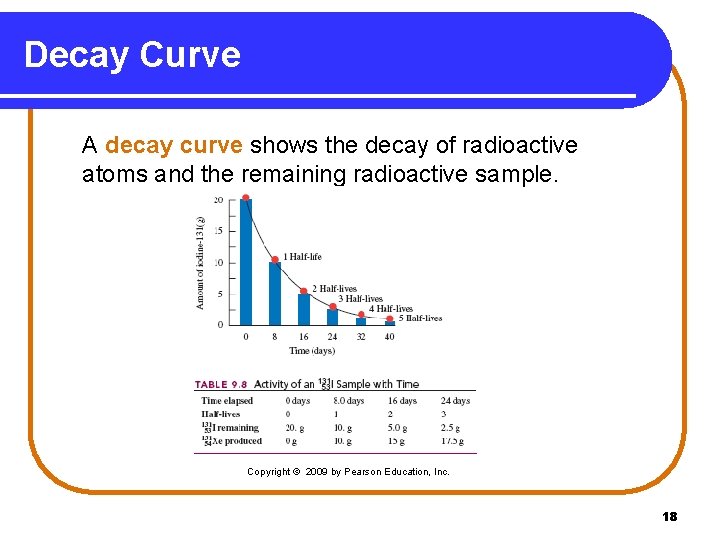

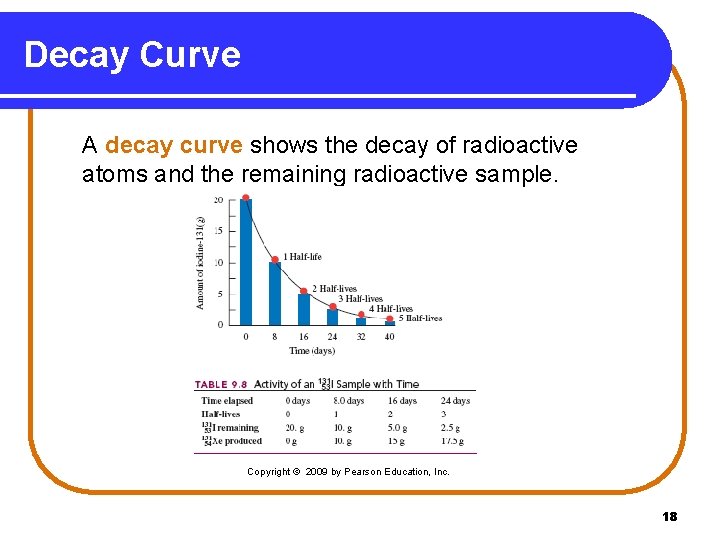

Decay Curve A decay curve shows the decay of radioactive atoms and the remaining radioactive sample. Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. 18

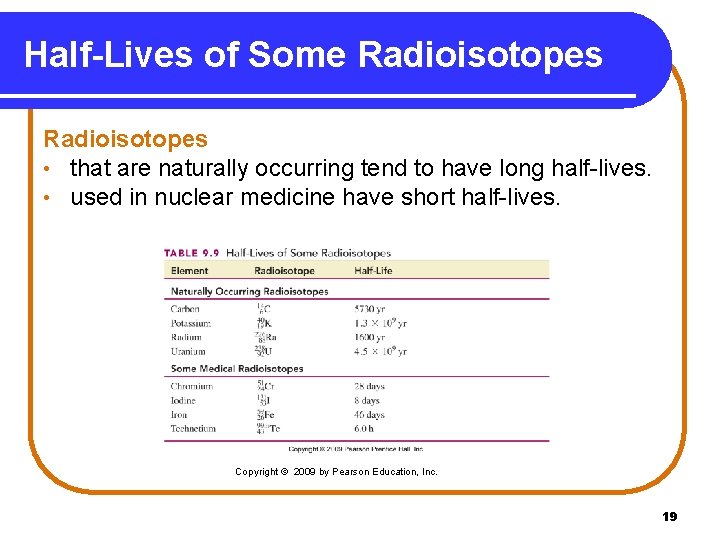

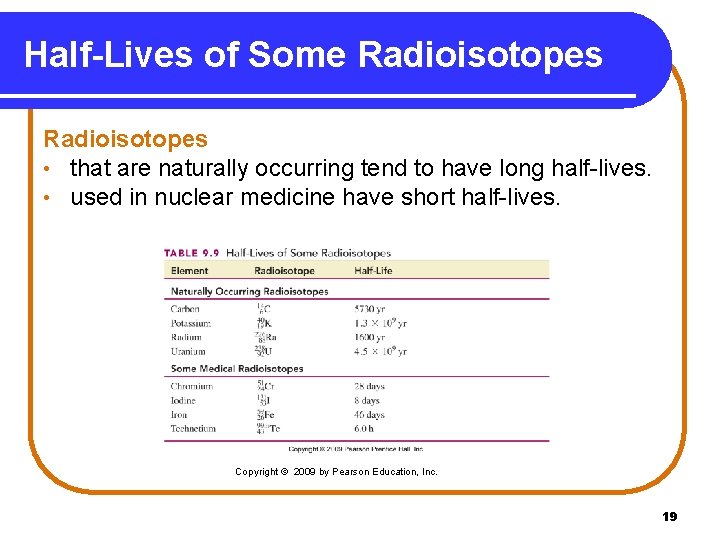

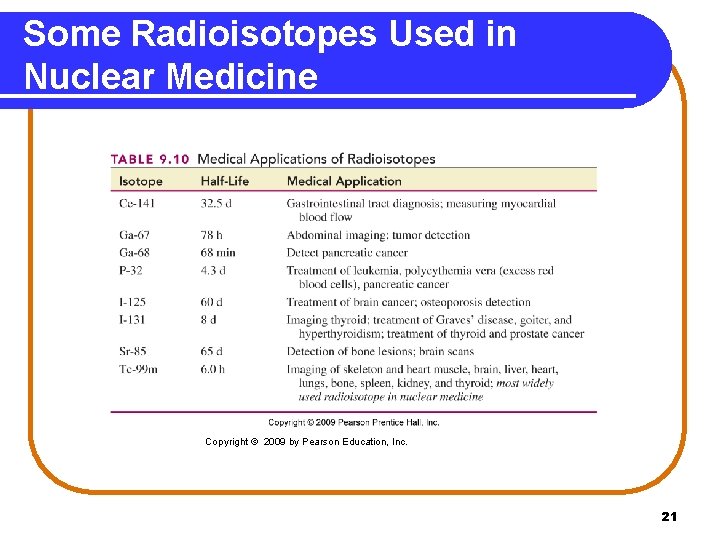

Half-Lives of Some Radioisotopes • that are naturally occurring tend to have long half-lives. • used in nuclear medicine have short half-lives. Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. 19

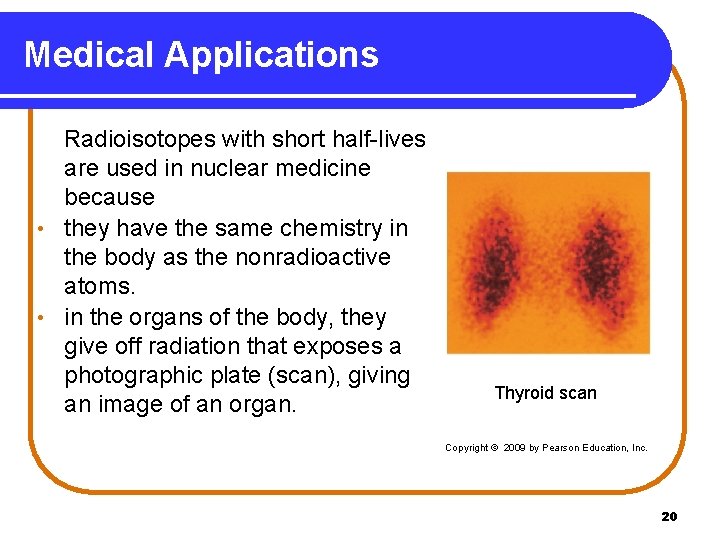

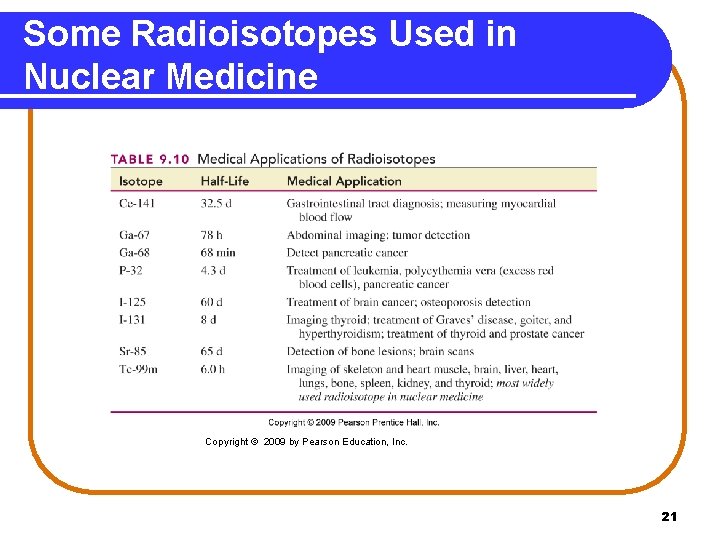

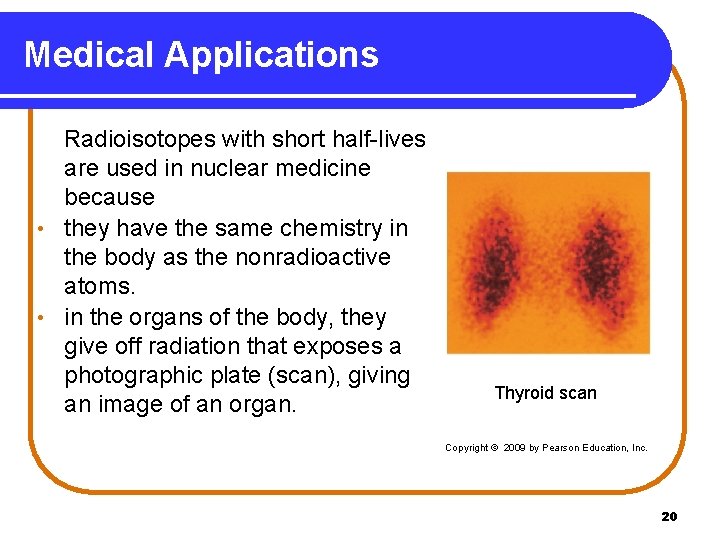

Medical Applications Radioisotopes with short half-lives are used in nuclear medicine because • they have the same chemistry in the body as the nonradioactive atoms. • in the organs of the body, they give off radiation that exposes a photographic plate (scan), giving an image of an organ. Thyroid scan Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. 20

Some Radioisotopes Used in Nuclear Medicine Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. 21

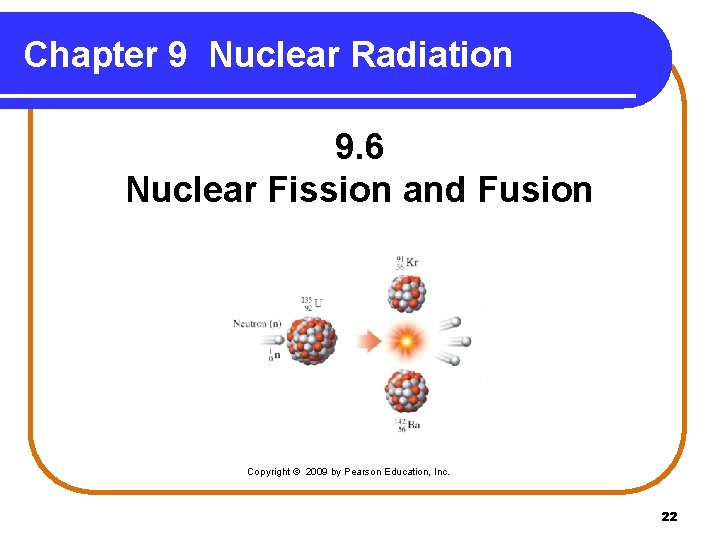

Chapter 9 Nuclear Radiation 9. 6 Nuclear Fission and Fusion Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. 22

Nuclear Fission In nuclear fission, • a large nucleus is bombarded with a small particle. • the nucleus splits into smaller nuclei and several neutrons. • large amounts of energy are released. 23

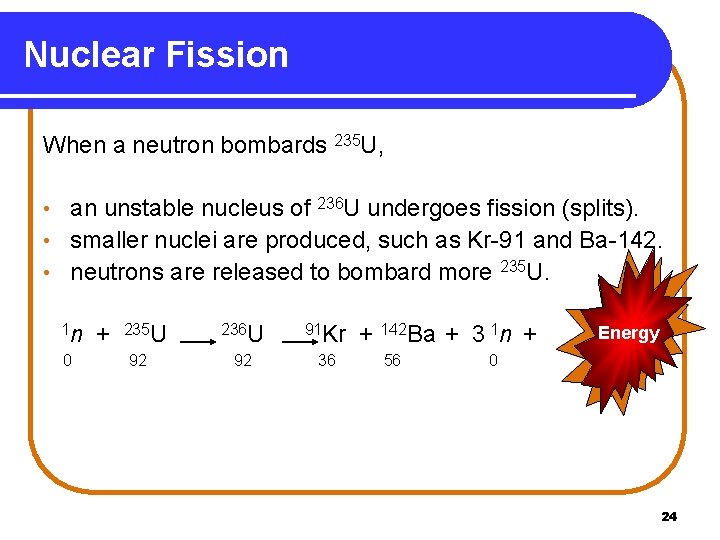

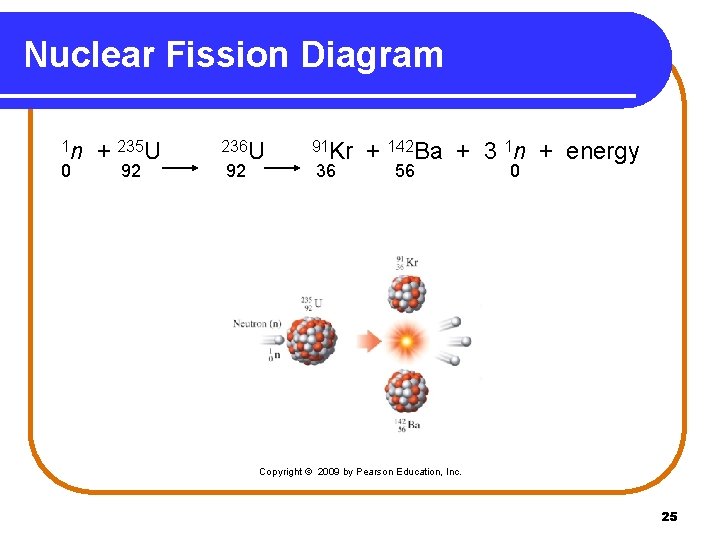

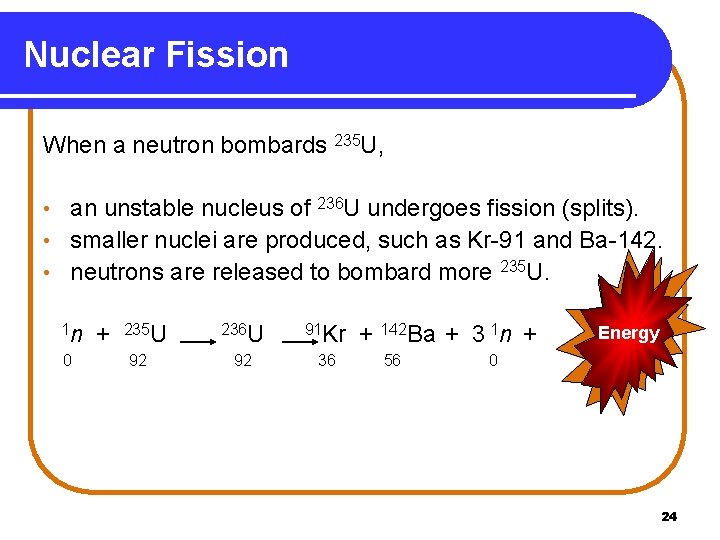

Nuclear Fission When a neutron bombards 235 U, an unstable nucleus of 236 U undergoes fission (splits). • smaller nuclei are produced, such as Kr-91 and Ba-142. • neutrons are released to bombard more 235 U. • 1 n 0 + 235 U 92 236 U 91 Kr 92 36 + 142 Ba + 3 1 n + 56 Energy 0 24

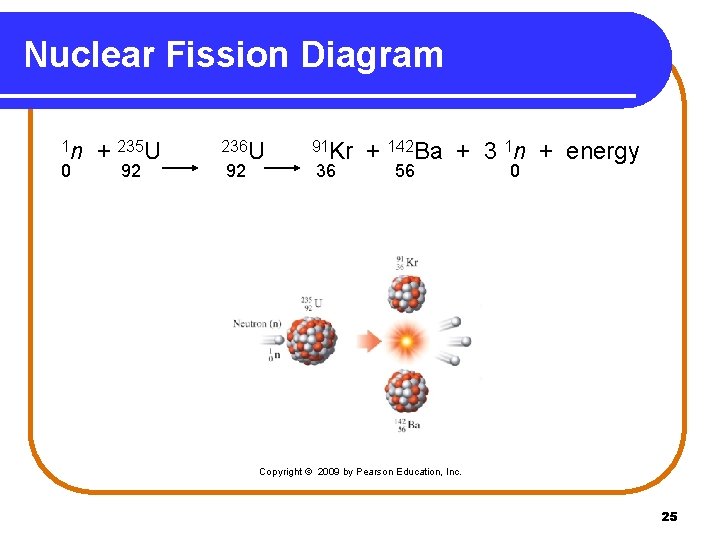

Nuclear Fission Diagram 1 n 0 + 235 U 92 236 U 92 91 Kr 36 + 142 Ba + 3 1 n + energy 56 0 Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. 25

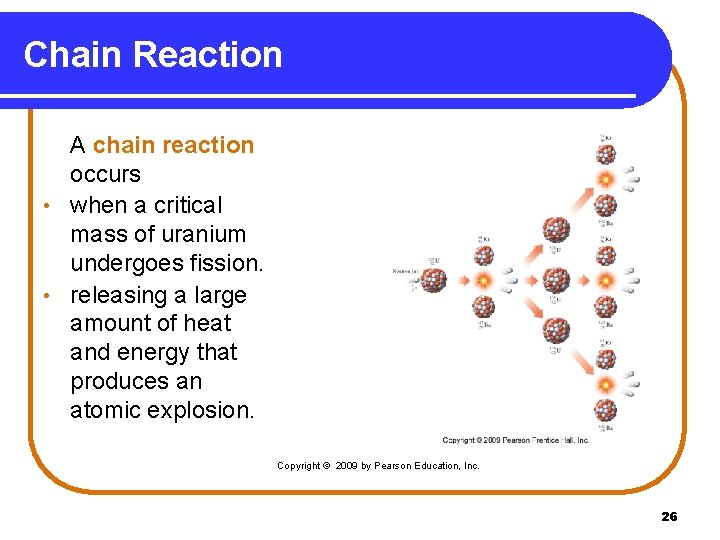

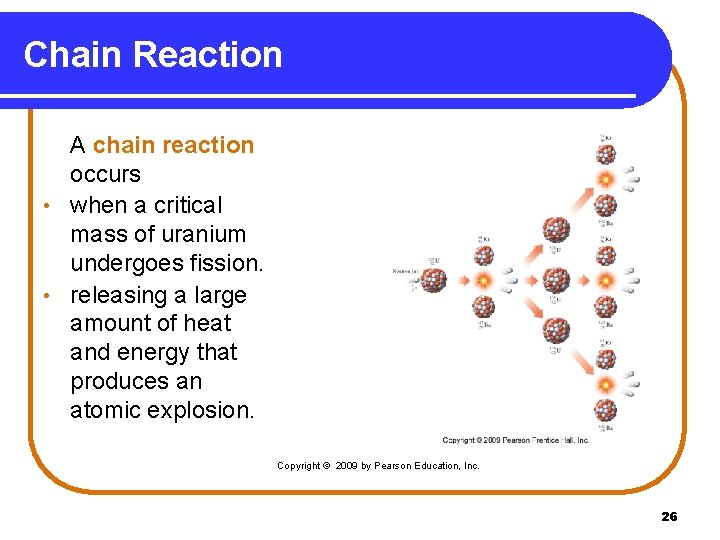

Chain Reaction A chain reaction occurs • when a critical mass of uranium undergoes fission. • releasing a large amount of heat and energy that produces an atomic explosion. Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. 26

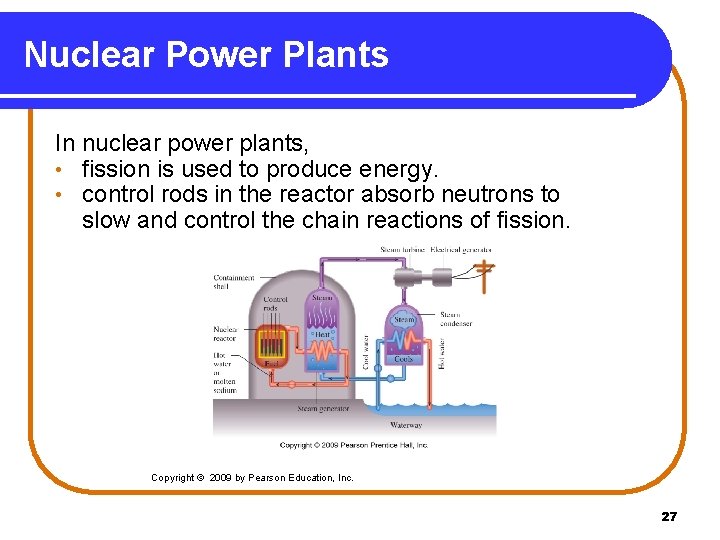

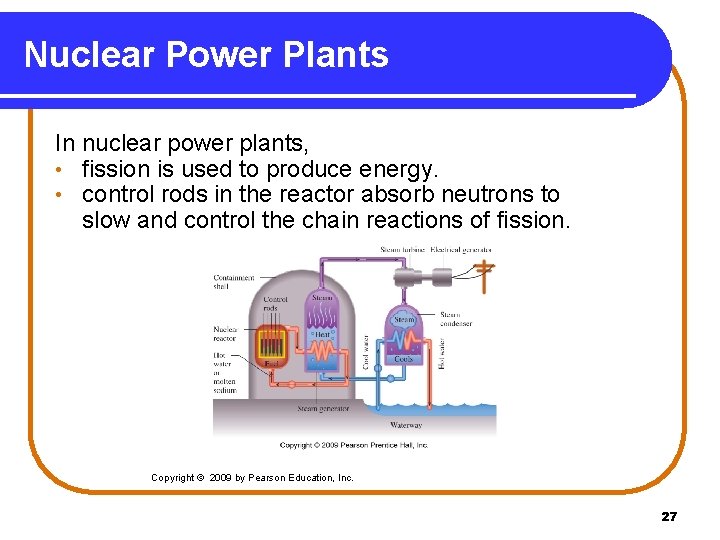

Nuclear Power Plants In nuclear power plants, • fission is used to produce energy. • control rods in the reactor absorb neutrons to slow and control the chain reactions of fission. Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. 27

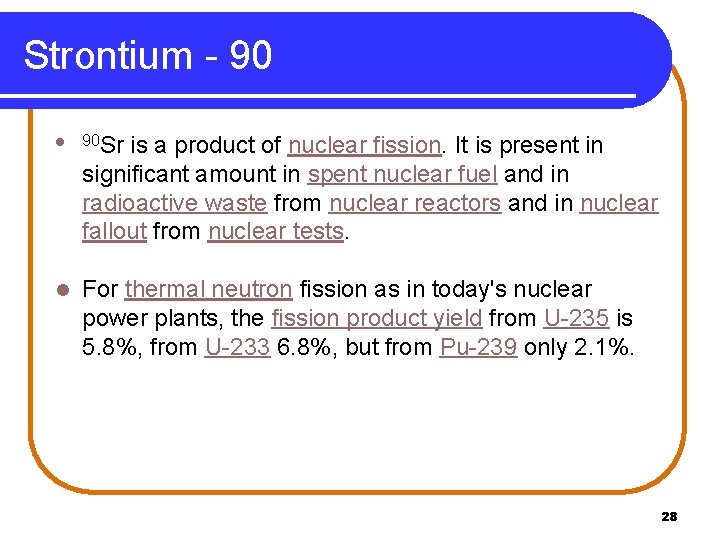

Strontium - 90 l 90 Sr is a product of nuclear fission. It is present in significant amount in spent nuclear fuel and in radioactive waste from nuclear reactors and in nuclear fallout from nuclear tests. l For thermal neutron fission as in today's nuclear power plants, the fission product yield from U-235 is 5. 8%, from U-233 6. 8%, but from Pu-239 only 2. 1%. 28

Strontium - 90 l Together with caesium isotopes 134 Cs, 137 Cs, and iodine isotope 131 I it was among the most important isotopes regarding health impacts after the Chernobyl disaster. 29

Strontium -90 l Strontium-90 is a "bone seeker" that exhibits biochemical behavior similar to calcium, the next lighter Group 2 element. After entering the organism, most often by ingestion with contaminated food or water, about 70 -80% of the dose gets excreted. l Virtually all remaining strontium-90 is deposited in bones and bone marrow, with the remaining 1% remaining in blood and soft tissues. 30

Strontium - 90 l Its presence in bones can cause bone cancer, cancer of nearby tissues, and leukemia. Exposure to 90 Sr can be tested by a bioassay, most commonly by urinalysis. 31

Iodine -131 l 131 I is a fission product with a yield of 2. 878% from uranium-235, [5] and can be released in nuclear weapons tests and nuclear accidents. l However, the short half-life means it is not present in significant quantities in cooled spent nuclear fuel, unlike iodine-129 whose half-life is nearly a billion times that of I-131. 32

Iodine - 131 l 131 I decays with a half-life of 8. 02 days with beta and gamma emissions. This nuclide of iodine atom has 78 neutrons in nucleus, the stable nuclide 127 I has 74 neutrons. On decaying, 131 I transforms into 131 Xe l The primary emissions of 131 I decay are 364 ke. V gamma rays (81% abundance) and beta particles with a maximal energy of 606 ke. V (89% abundance). 33

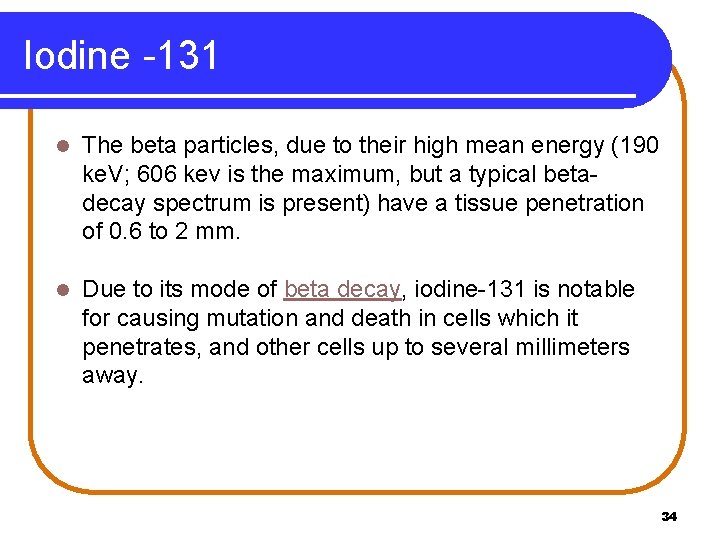

Iodine -131 l The beta particles, due to their high mean energy (190 ke. V; 606 kev is the maximum, but a typical betadecay spectrum is present) have a tissue penetration of 0. 6 to 2 mm. l Due to its mode of beta decay, iodine-131 is notable for causing mutation and death in cells which it penetrates, and other cells up to several millimeters away. 34