Chapter 8Field2005 Comparing several means ANOVA General Linear

- Slides: 87

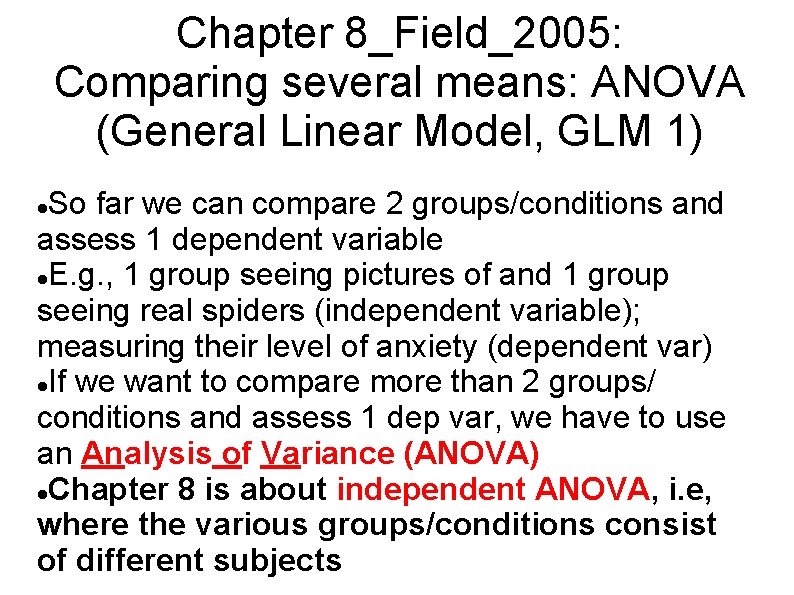

Chapter 8_Field_2005: Comparing several means: ANOVA (General Linear Model, GLM 1) So far we can compare 2 groups/conditions and assess 1 dependent variable E. g. , 1 group seeing pictures of and 1 group seeing real spiders (independent variable); measuring their level of anxiety (dependent var) If we want to compare more than 2 groups/ conditions and assess 1 dep var, we have to use an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) Chapter 8 is about independent ANOVA, i. e, where the various groups/conditions consist of different subjects

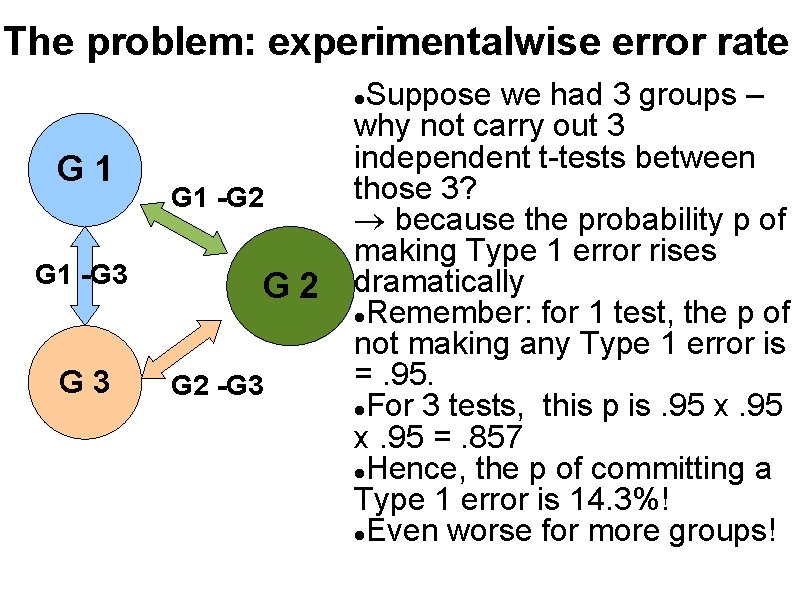

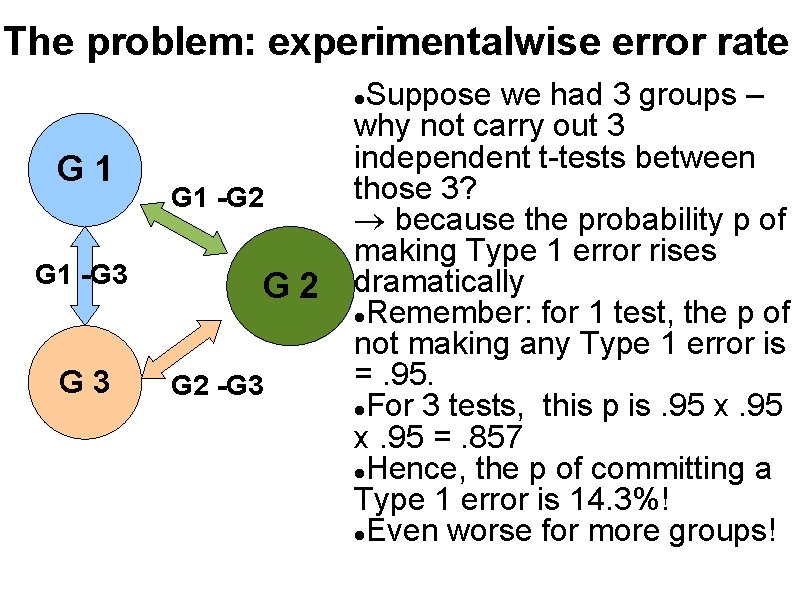

The problem: experimentalwise error rate Suppose we had 3 groups – why not carry out 3 independent t-tests between those 3? because the probability p of making Type 1 error rises dramatically Remember: for 1 test, the p of not making any Type 1 error is =. 95. For 3 tests, this p is. 95 x. 95 =. 857 Hence, the p of committing a Type 1 error is 14. 3%! Even worse for more groups! G 1 -G 3 G 1 -G 2 G 2 -G 3

The solution: ANOVA gives us an overall F-value that tells us whether n means are the same, in an overall test (omnibus test). It looks for an overall experimental effect. It does NOT tell us which of the group differences cause this overall effect, only that X 1 = X 2 = X 3 is NOT true. Separate contrasts may be carried out later

ANOVA as regresssion Correlational research Looked at real-world relationships Had adopted multiple regression Experimental research Conducted controlled experiments Had adopted ANOVA Although having arisen in different research contexts, regression and ANOVA are conceptually the same thing! The General Linear Model (GLM) accommodates this fact.

ANOVA as regression ANOVA compares the amount of systematic variance to the unsystematic variance. This ratio is called F-ratio: ANOVA: F-ratio: systematic (experimental) variance unsystematic (other and error) variance Regression: F-ratio: variance of the regression model variance of the simple model

ANOVA as regression The F-ratios in ANOVA and regression are the same. ANOVA can be represented by the multiple regression equation with as many predictors as the experiment has groups minus 1 (because of the df's)

An example (using viagra. sav) We compare 3 independent groups Indep Var (IV): treating subjects with 'Viagra' 1. placebo 2. low dose of V 3. high dose of V Dep Var (DP): measure of 'libido' General equation for predicting libido from treatment Outcomei= (Modeli) + errori In a regression approach, the 'experimental model' and the 'simple model' were coded as dummy variabes (1 and 0). The outcome of the good model was compared to that of the simple model.

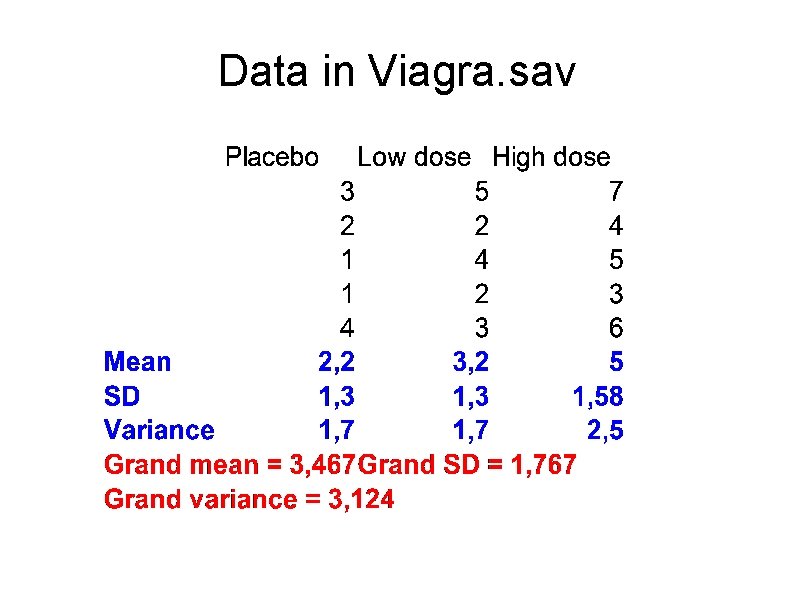

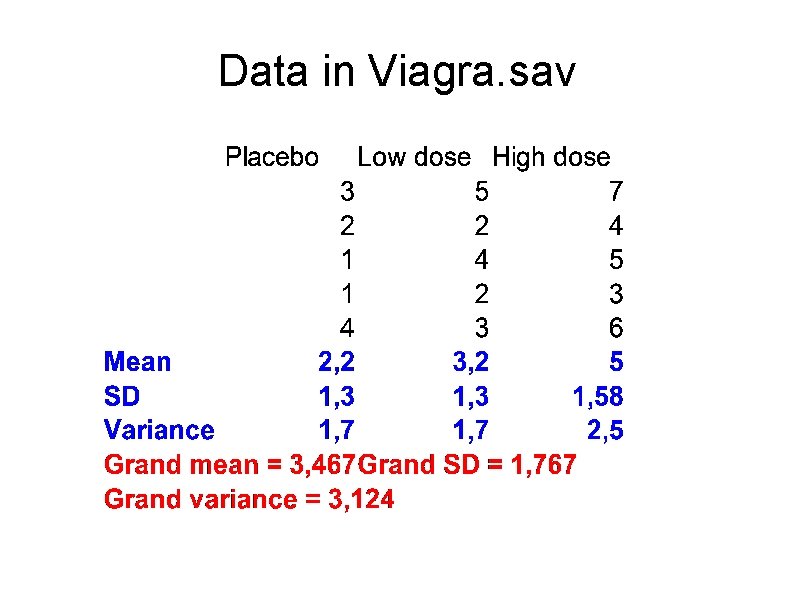

Data in Viagra. sav

Dummy variables for coding groups With more than two groups, we have to extend the number of dummy variables in regression. If there are only 2 groups, we have a base category 0 and a real model 1. If there are more than 2 groups, we need as many coding variables as there are groups – 1. One group acts as a 'baseline' or 'control group' (0) In the viagra example, there are 3 groups, hence we need 2 coding variables (for the groups 'lw dose' and 'high dose') + a control group ('placebo')

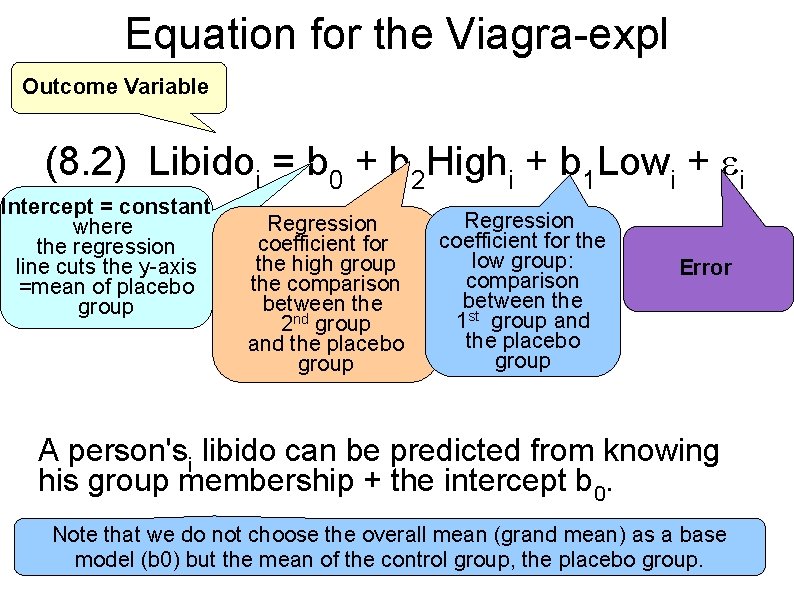

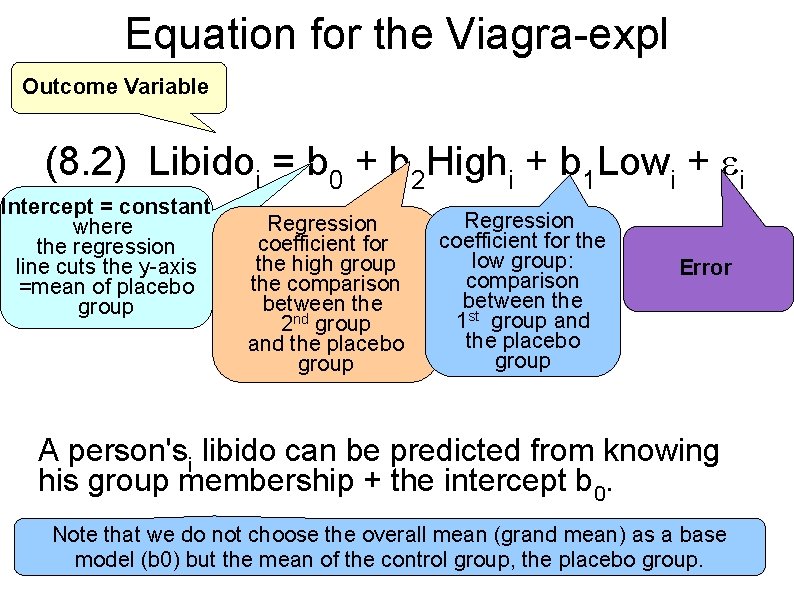

Equation for the Viagra-expl Outcome Variable (8. 2) Libidoi = b 0 + b 2 Highi + b 1 Lowi + i Intercept = constant where the regression line cuts the y-axis =mean of placebo group Regression coefficient for the high group the comparison between the 2 nd group and the placebo group Regression coefficient for the low group: comparison between the 1 st group and the placebo group Error A person'si libido can be predicted from knowing his group membership + the intercept b 0. Note that we do not choose the overall mean (grand mean) as a base model (b 0) but the mean of the control group, the placebo group.

Choice of b 0 – the constant So far, in linear regression we had chosen the grand mean as the base model. In binary logistic regression we had chosen the most frequent case as the base model. Here, we choose the placebo group as our base model (b 0). Why, do you think? This is because as good experimenters we have to control for any unspecific effects due to giving subjects any treatment. This we test with the placebo group. The comparison between the placebo and the experimental groups will tell us whether, above this unspecific effect, the drug (in various doses) has a causal effect on the dep var. Note that in regression you are free to choose your base model! That makes regression a highly flexible method.

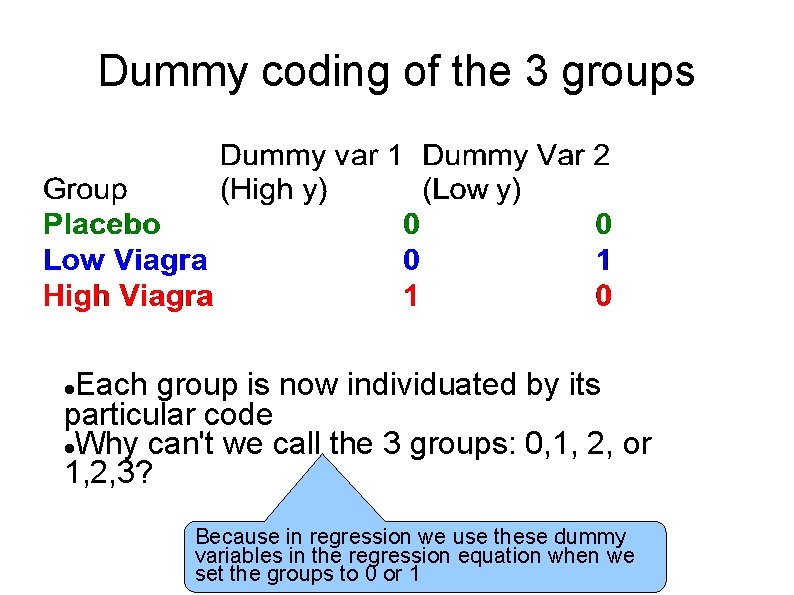

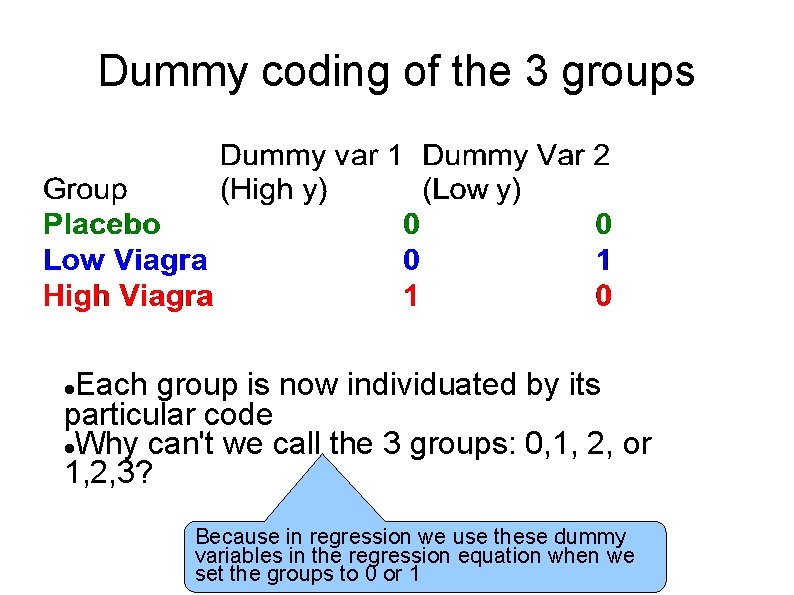

Dummy coding of the 3 groups Each group is now individuated by its particular code Why can't we call the 3 groups: 0, 1, 2, or 1, 2, 3? Because in regression we use these dummy variables in the regression equation when we set the groups to 0 or 1

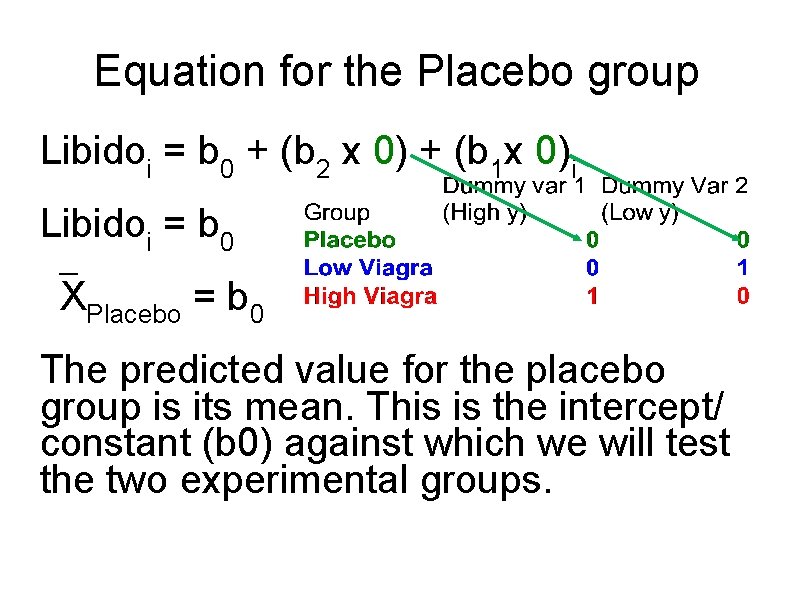

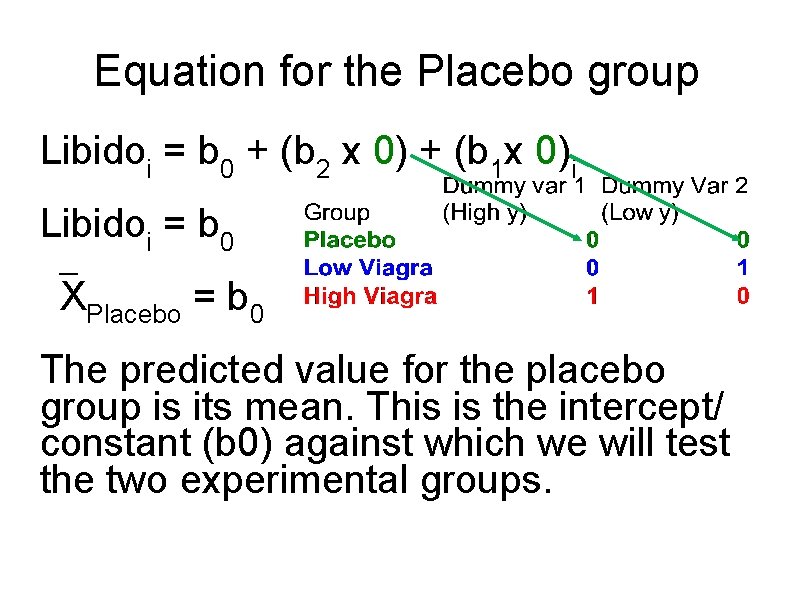

Equation for the Placebo group Libidoi = b 0 + (b 2 x 0) + (b 1 x 0)i Libidoi = b 0 XPlacebo = b 0 The predicted value for the placebo group is its mean. This is the intercept/ constant (b 0) against which we will test the two experimental groups.

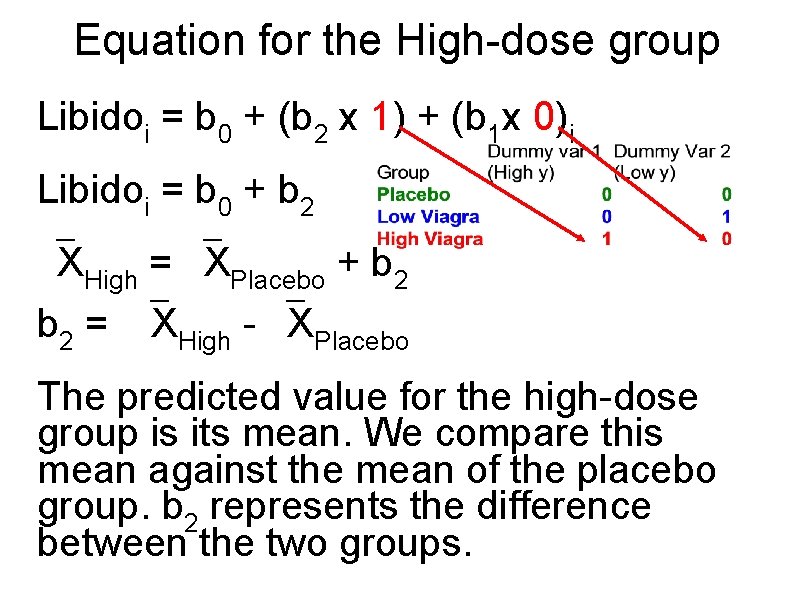

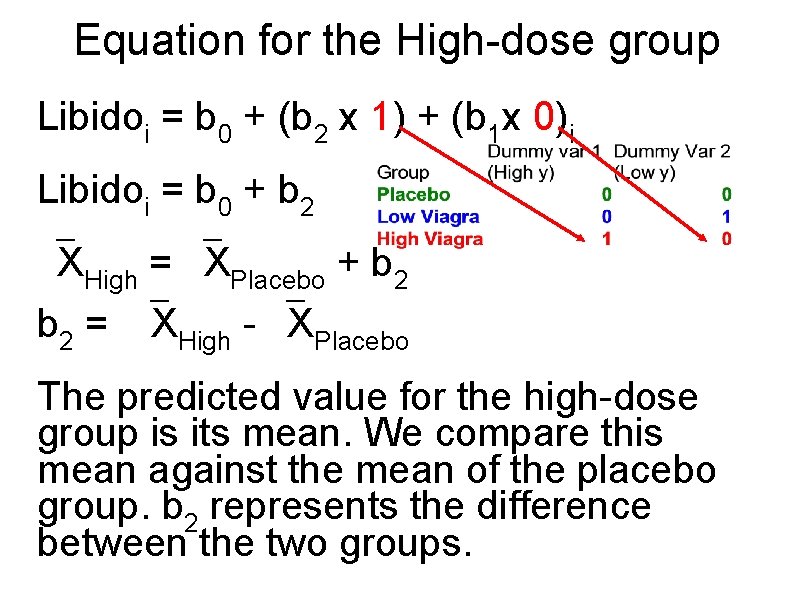

Equation for the High-dose group Libidoi = b 0 + (b 2 x 1) + (b 1 x 0)i Libidoi = b 0 + b 2 XHigh = XPlacebo + b 2 = XHigh - XPlacebo The predicted value for the high-dose group is its mean. We compare this mean against the mean of the placebo group. b 2 represents the difference between the two groups.

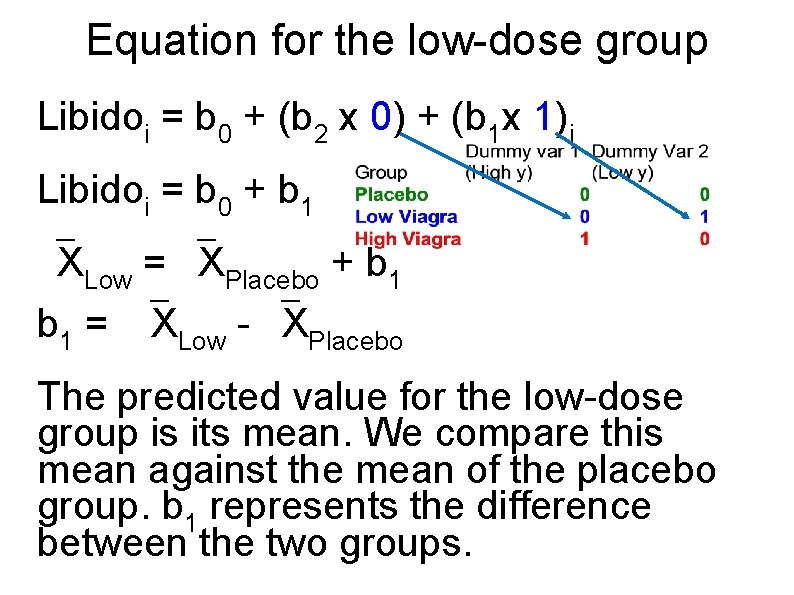

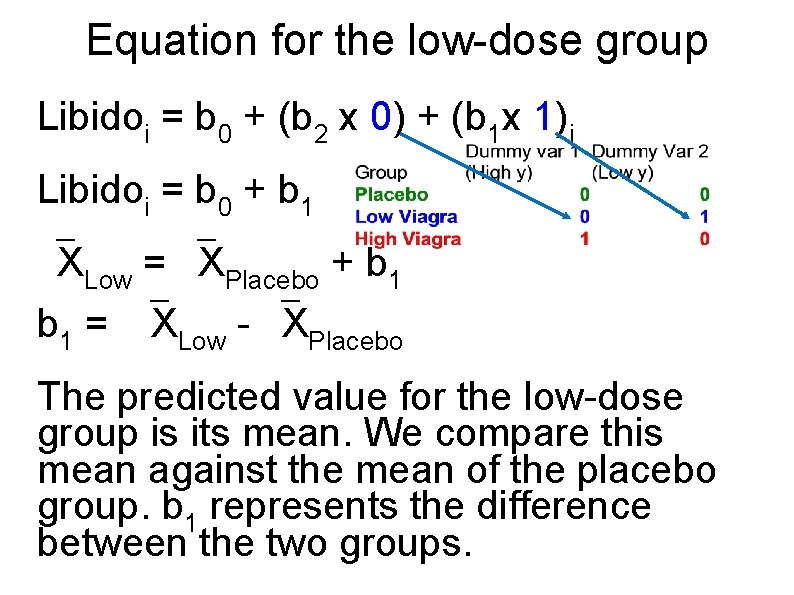

Equation for the low-dose group Libidoi = b 0 + (b 2 x 0) + (b 1 x 1)i Libidoi = b 0 + b 1 XLow = XPlacebo + b 1 = XLow - XPlacebo The predicted value for the low-dose group is its mean. We compare this mean against the mean of the placebo group. b 1 represents the difference between the two groups.

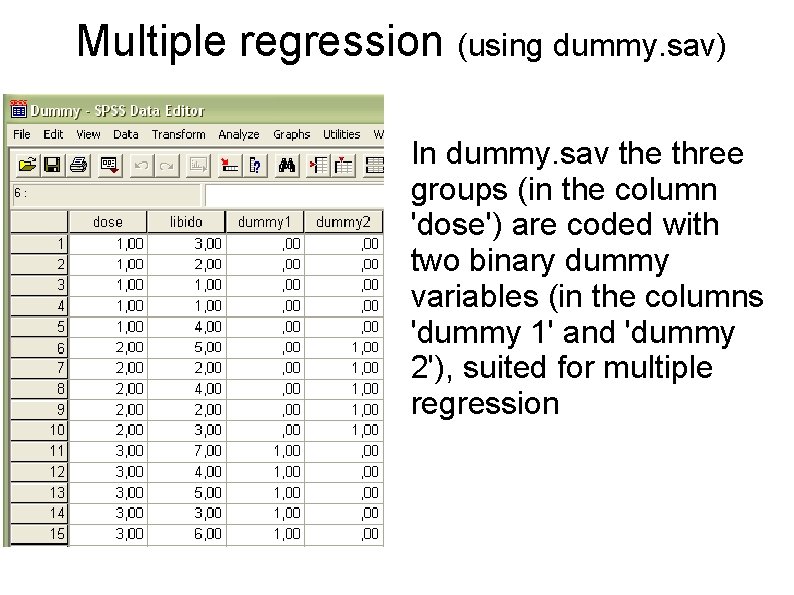

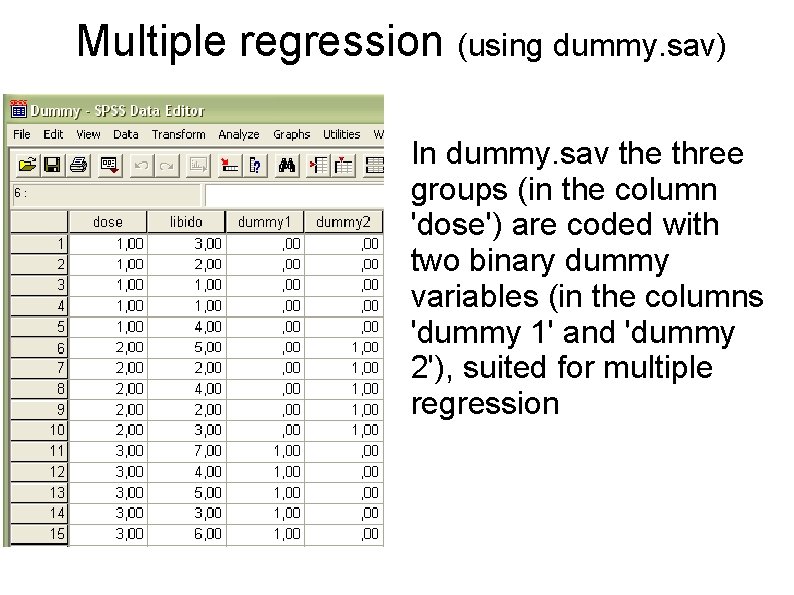

Multiple regression (using dummy. sav) In dummy. sav the three groups (in the column 'dose') are coded with two binary dummy variables (in the columns 'dummy 1' and 'dummy 2'), suited for multiple regression

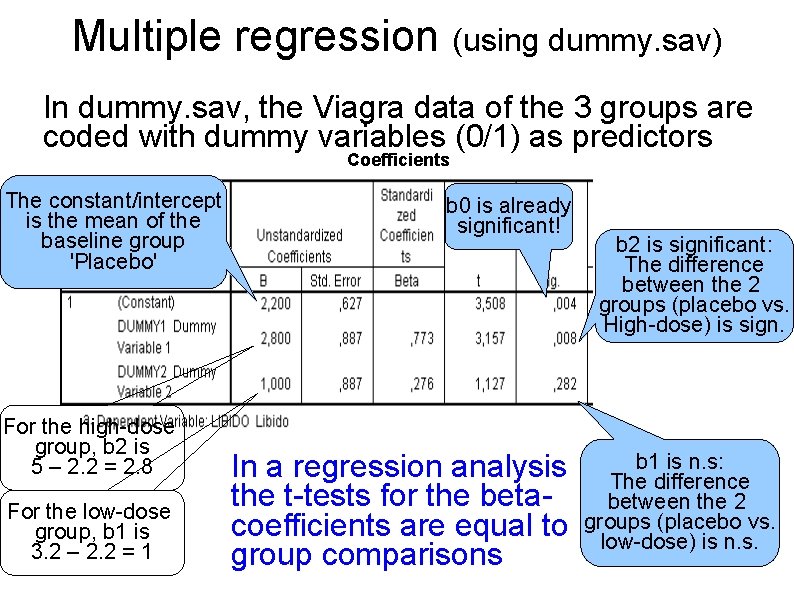

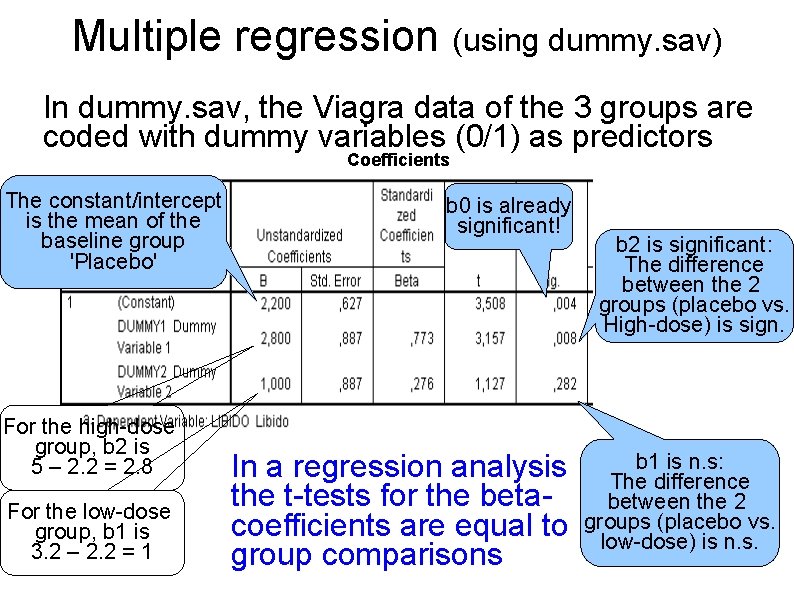

Multiple regression (using dummy. sav) In dummy. sav, the Viagra data of the 3 groups are coded with dummy variables (0/1) as predictors Coefficients The constant/intercept is the mean of the baseline group 'Placebo' For the high-dose group, b 2 is 5 – 2. 2 = 2. 8 For the low-dose group, b 1 is 3. 2 – 2. 2 = 1 b 0 is already significant! In a regression analysis the t-tests for the betacoefficients are equal to group comparisons b 2 is significant: The difference between the 2 groups (placebo vs. High-dose) is sign. b 1 is n. s: The difference between the 2 groups (placebo vs. low-dose) is n. s.

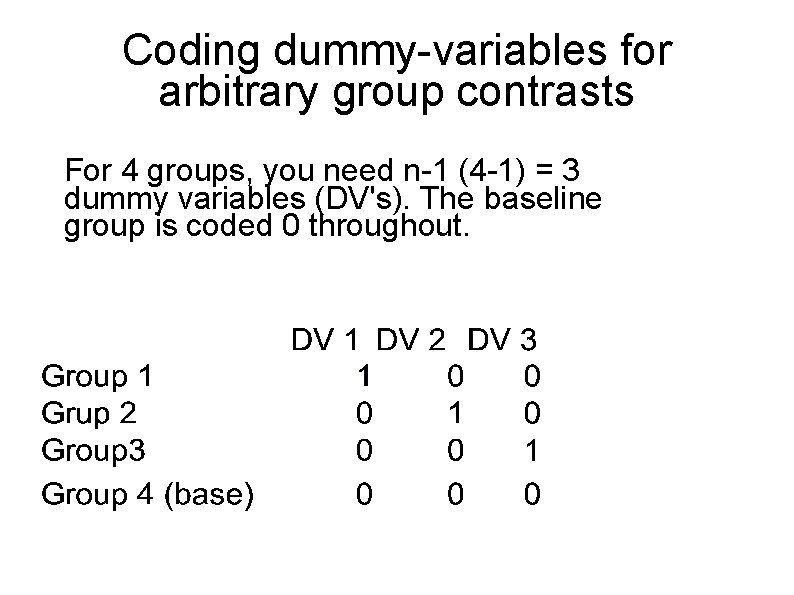

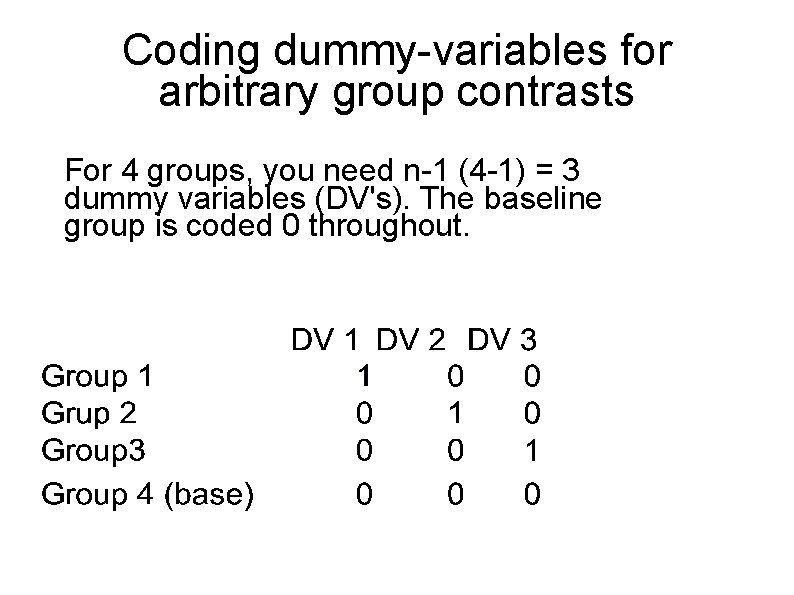

Coding dummy-variables for arbitrary group contrasts For 4 groups, you need n-1 (4 -1) = 3 dummy variables (DV's). The baseline group is coded 0 throughout.

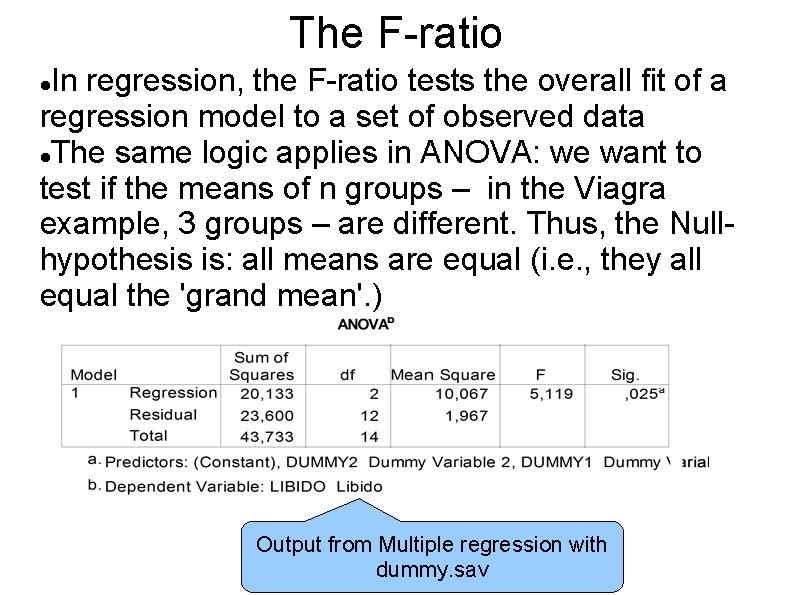

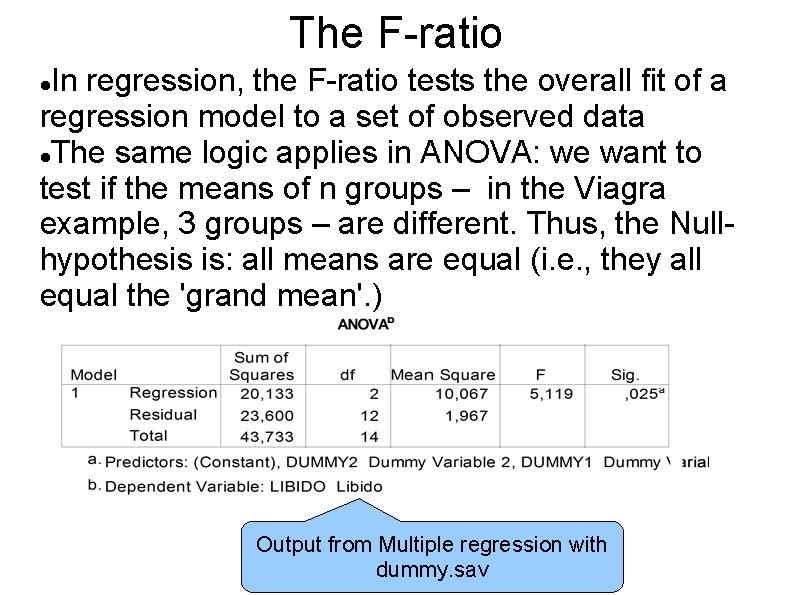

The F-ratio In regression, the F-ratio tests the overall fit of a regression model to a set of observed data The same logic applies in ANOVA: we want to test if the means of n groups – in the Viagra example, 3 groups – are different. Thus, the Nullhypothesis is: all means are equal (i. e. , they all equal the 'grand mean'. ) Output from Multiple regression with dummy. sav

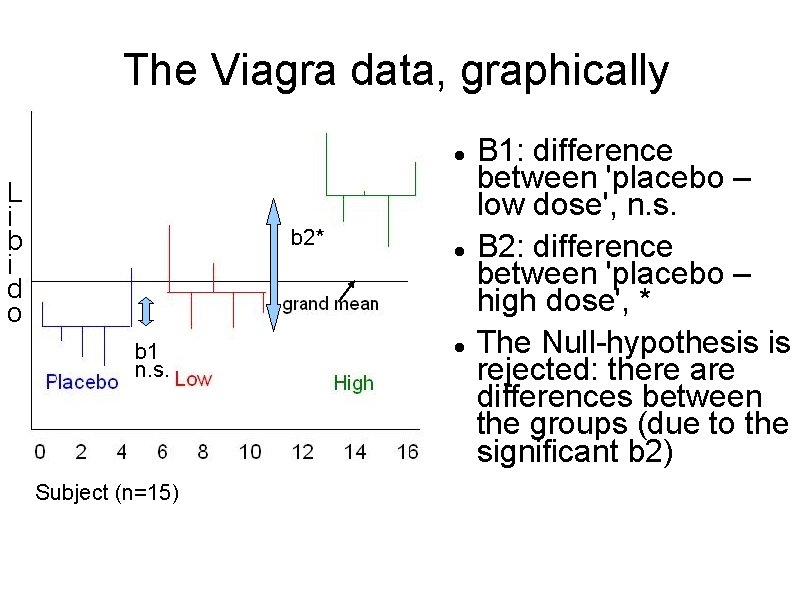

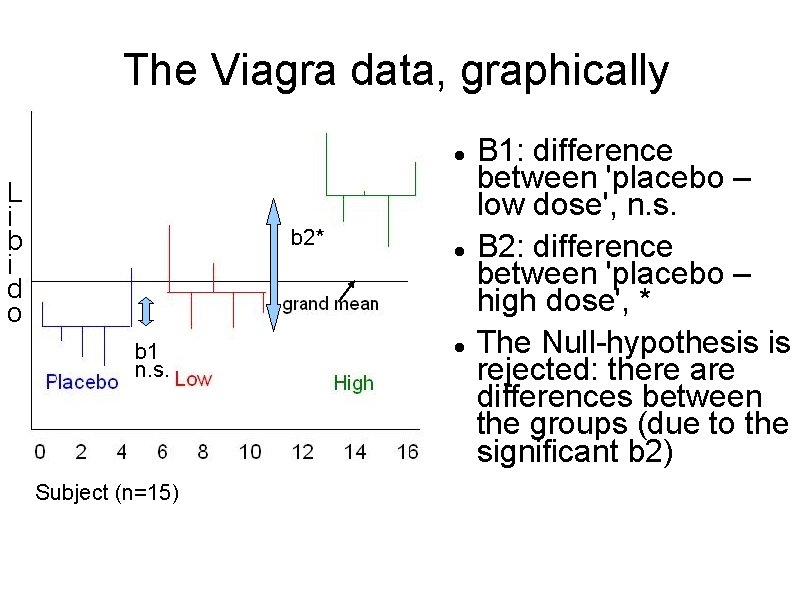

The Viagra data, graphically L i b i d o b 2* b 1 n. s. Subject (n=15) B 1: difference between 'placebo – low dose', n. s. B 2: difference between 'placebo – high dose', * The Null-hypothesis is rejected: there are differences between the groups (due to the significant b 2)

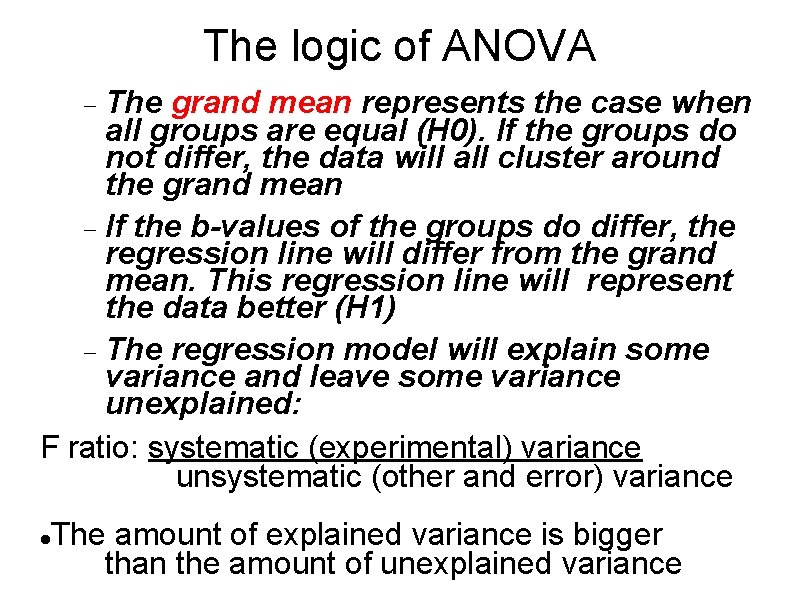

The logic of ANOVA The grand mean represents the case when all groups are equal (H 0). If the groups do not differ, the data will all cluster around the grand mean If the b-values of the groups do differ, the regression line will differ from the grand mean. This regression line will represent the data better (H 1) The regression model will explain some variance and leave some variance unexplained: F ratio: systematic (experimental) variance unsystematic (other and error) variance The amount of explained variance is bigger than the amount of unexplained variance

Basic equation (8. 3) Deviation = (observed – model)2 With equation (8. 3) we calculate the fit of the basic model (placebo group, b 0) and the fit of the best model (regression model, b 1 and b 2). If the regression model is better than the basic model, it should fit the data better, hence the deviation between the observed data and the predicted data will be smaller.

Total sum of squares (SST) For all data points, we sum up their differences from the grand mean and square them. This is SST. (8. 4) SST = (xi – xgrand )2 The grand variance is the SST/(N-1). From the grand variance we can caculate the SST.

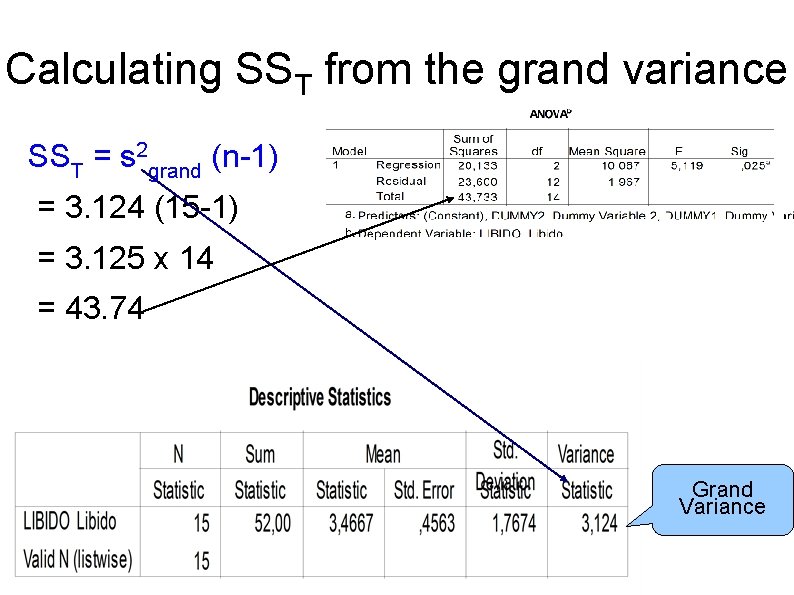

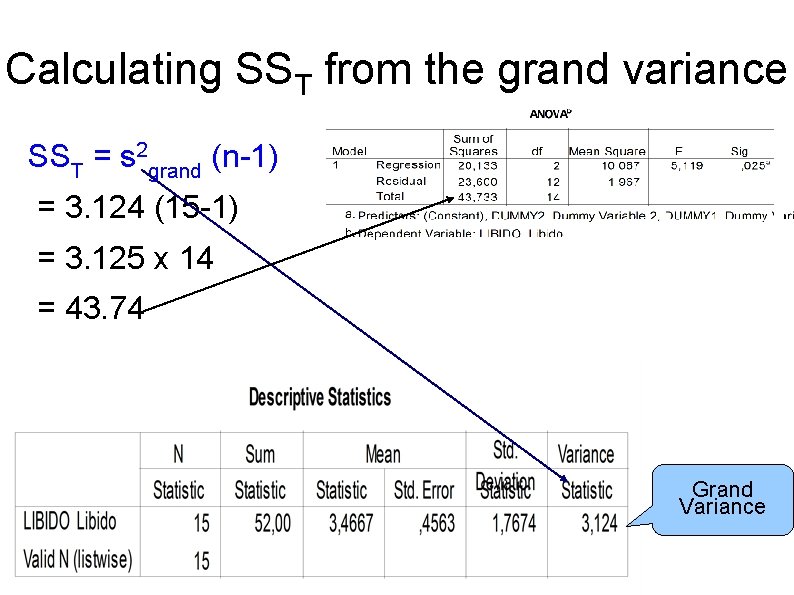

Calculating SST from the grand variance SST = s 2 grand (n-1) = 3. 124 (15 -1) = 3. 125 x 14 = 43. 74 Grand Variance

Degrees of freedom, df For any number of observations, the degrees of freedom is (n-1) since you can only choose (n-1) values freely, whereas the last obervation is determined – it is the only one that is left. If we have 4 observations, they are free to vary in any way, i. e. , they can take any value. If we use this sample of 4 observations to calculate the SD of the population (i. e. , SE), we take the mean of the sample as an estimate of the population's mean. In doing so, we hold 1 parameter (the mean) constant.

Degrees of freedom, df – continued If the sample mean is 10, we also assume that the population mean is 10. This value we keep constant. With the mean fixed, our observations are not free to vary anymore, completely. Only 3 can vary. The fourth must have the value that is left over in order to keep the mean constant Expl: If 3 observations are 7, 15, and 8, then the 4 th must be 10, in order to arrive at a mean of 10. Thus, holding one parameter constant, the df are one less than the N of the sample, df = n-1 Therefore, if we estimate the SD of the population (SE) from the SD of the sample, we divide the SS by n-1 and not by n.

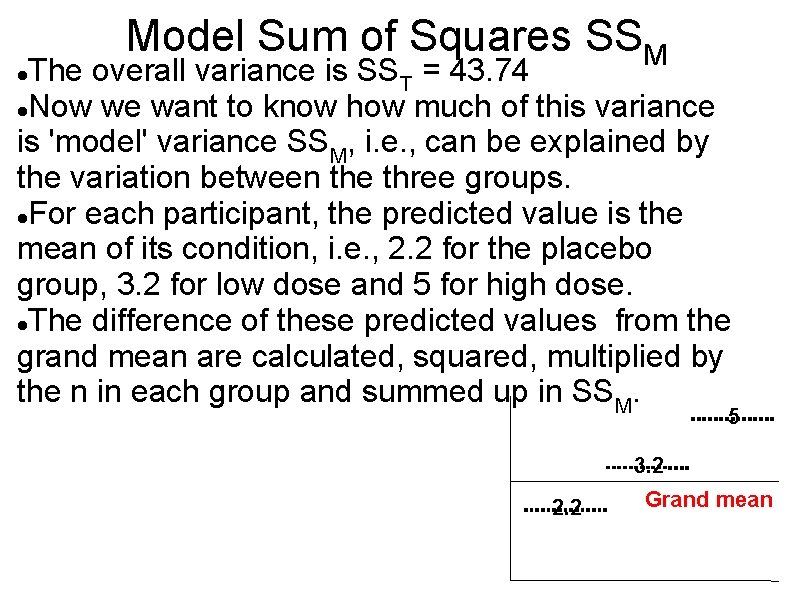

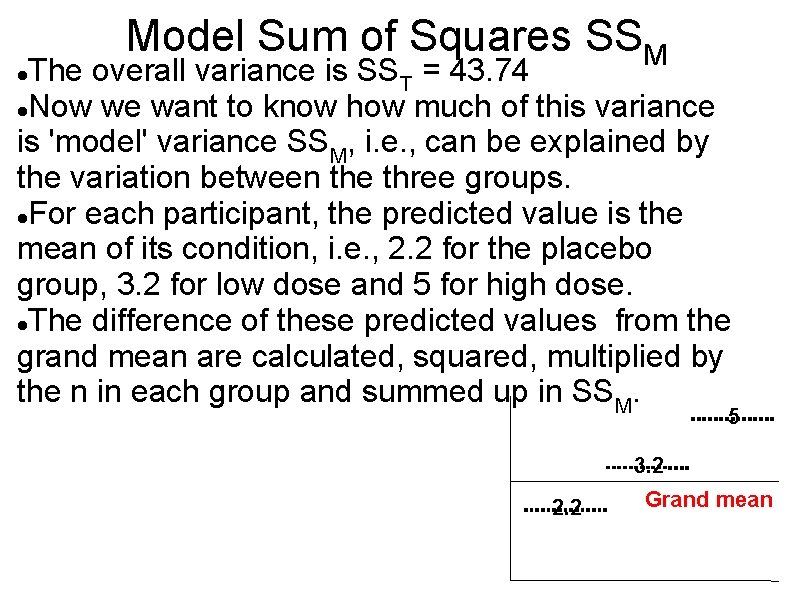

Model Sum of Squares SSM The overall variance is SST = 43. 74 Now we want to know how much of this variance is 'model' variance SSM, i. e. , can be explained by the variation between the three groups. For each participant, the predicted value is the mean of its condition, i. e. , 2. 2 for the placebo group, 3. 2 for low dose and 5 for high dose. The difference of these predicted values from the grand mean are calculated, squared, multiplied by the n in each group and summed up in SSM. 5 3. 2 2. 2 Grand mean

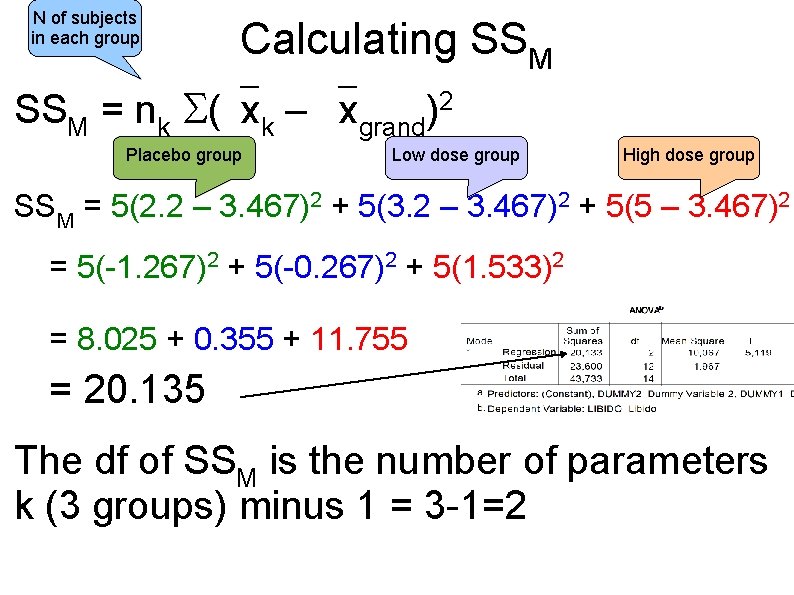

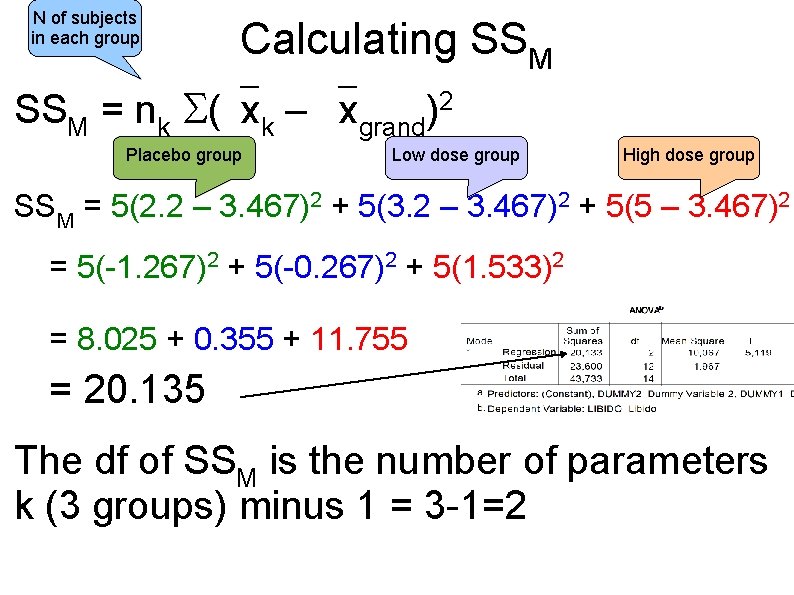

N of subjects in each group Calculating SSM = nk ( xk – xgrand)2 Placebo group Low dose group High dose group SSM = 5(2. 2 – 3. 467)2 + 5(3. 2 – 3. 467)2 + 5(5 – 3. 467)2 = 5(-1. 267)2 + 5(-0. 267)2 + 5(1. 533)2 = 8. 025 + 0. 355 + 11. 755 = 20. 135 The df of SSM is the number of parameters k (3 groups) minus 1 = 3 -1=2

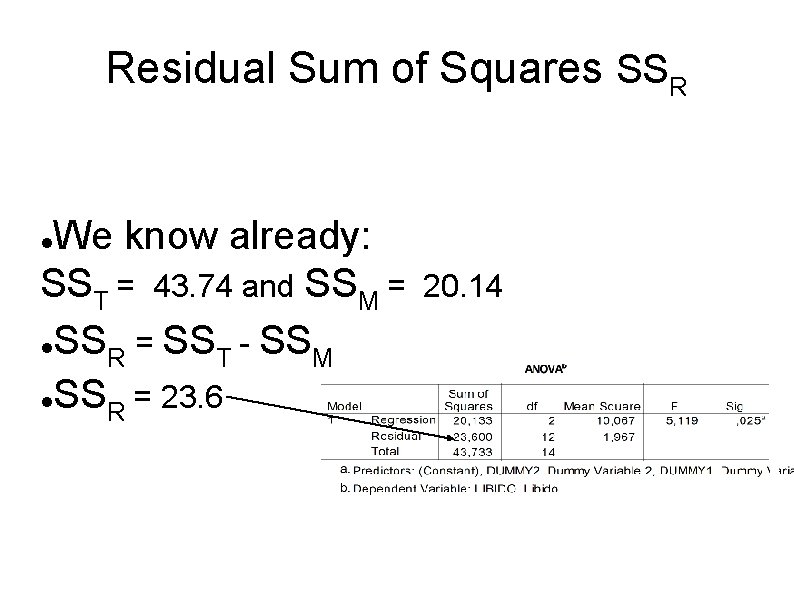

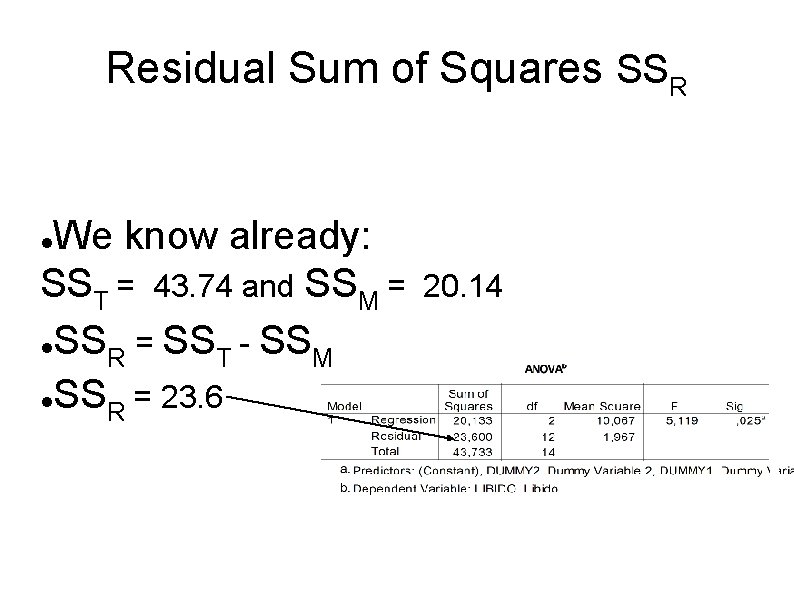

Residual Sum of Squares SSR We know already: SST = 43. 74 and SSM = SS R = SST - SSM SS = 23. 6 R 20. 14

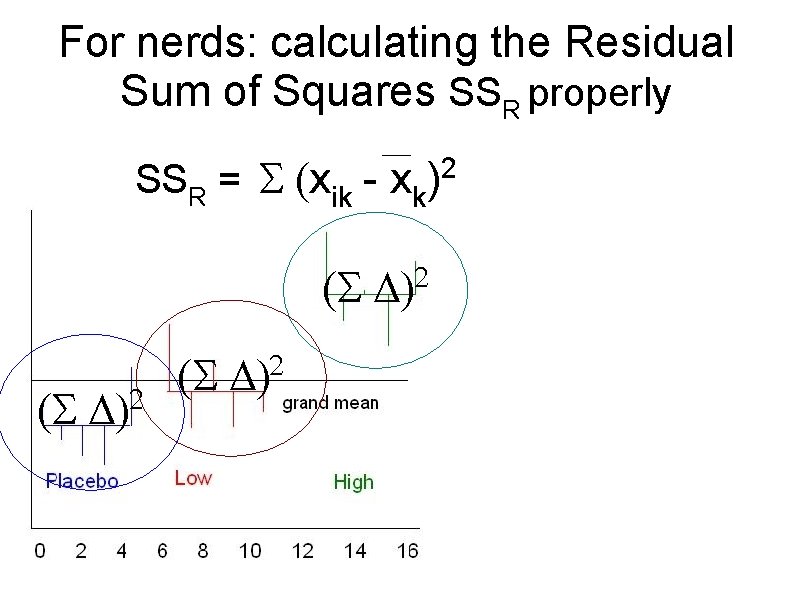

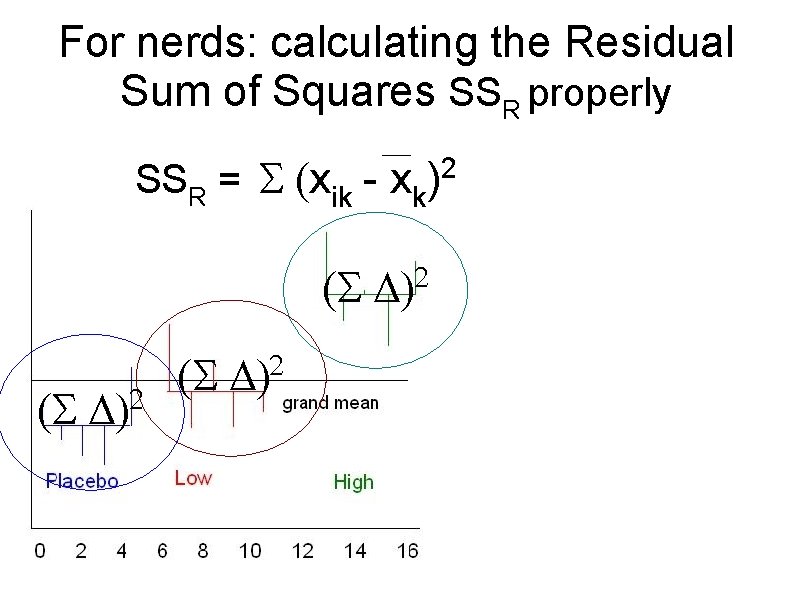

For nerds: calculating the Residual Sum of Squares SSR properly SSR = xik - 2 xk)

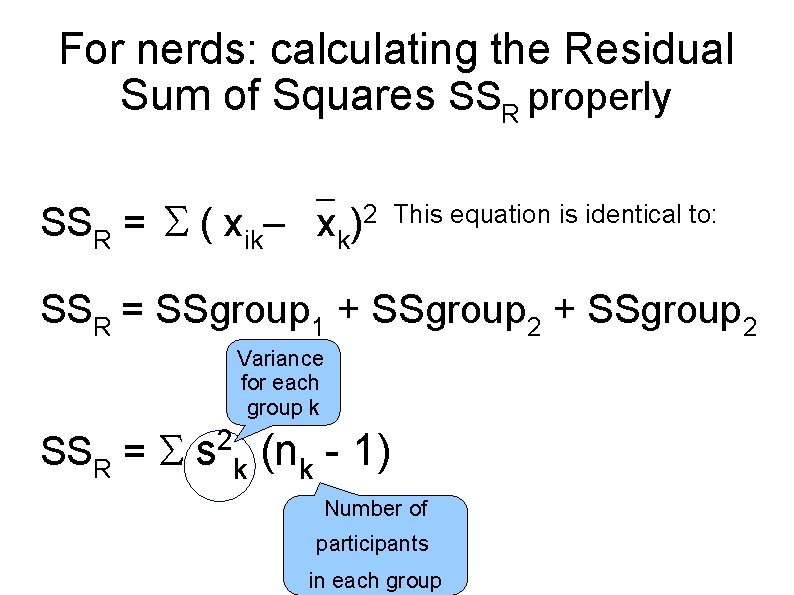

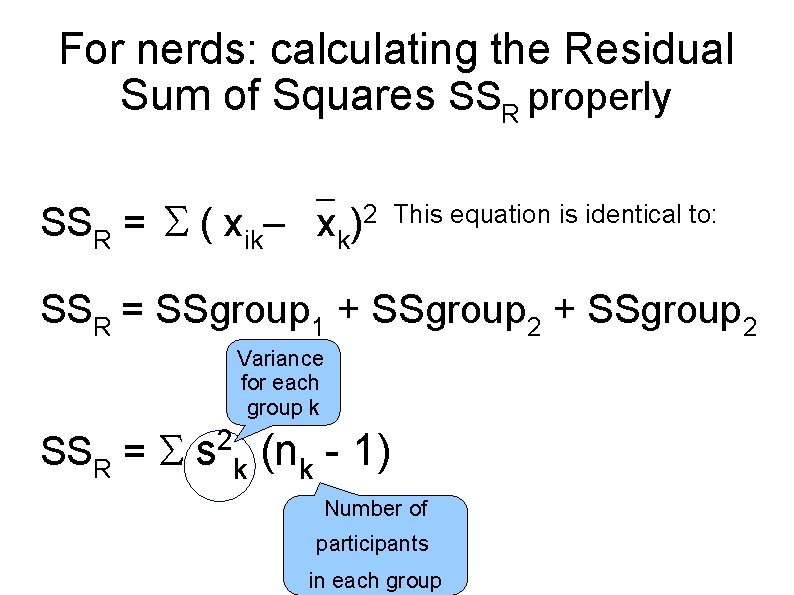

For nerds: calculating the Residual Sum of Squares SSR properly SSR = ( xik– xk 2 This equation is identical to: ) SSR = SSgroup 1 + SSgroup 2 Variance for each group k SSR = 2 s k (nk - 1) Number of participants in each group

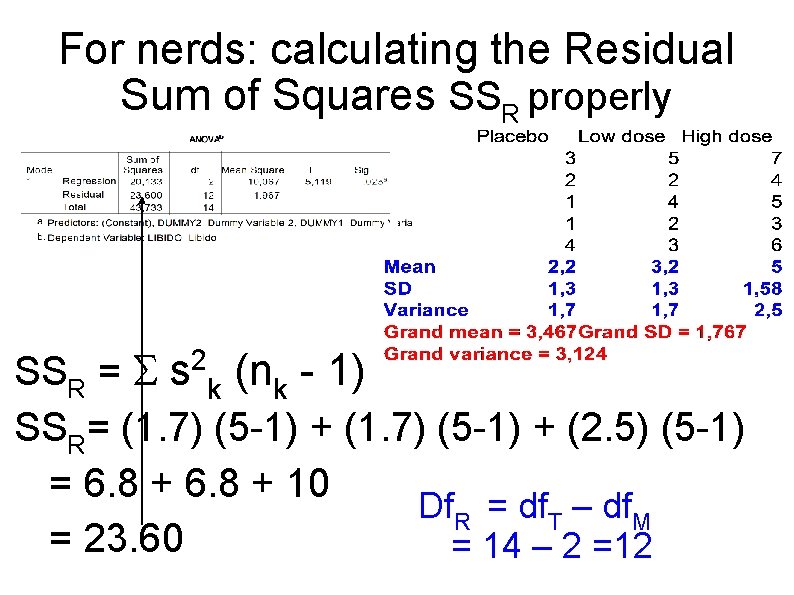

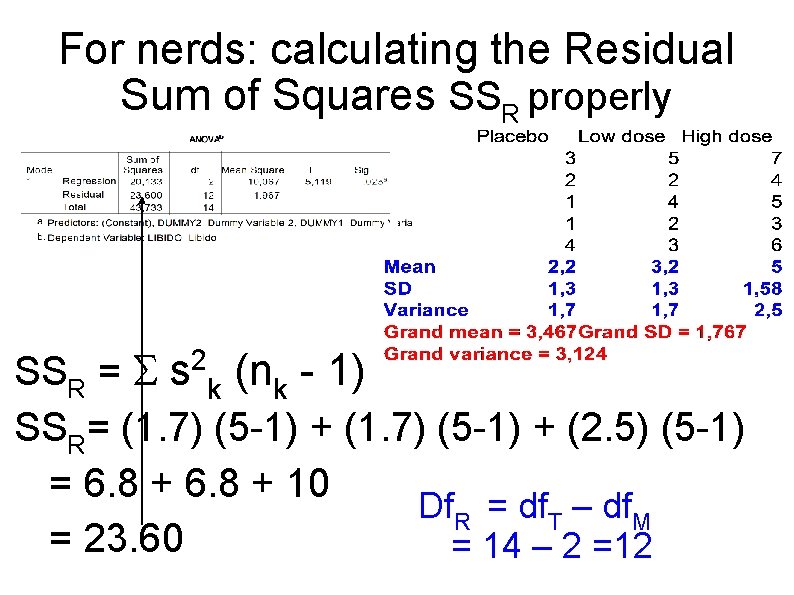

For nerds: calculating the Residual Sum of Squares SSR properly SSR = s k (nk - 1) SSR= (1. 7) (5 -1) + (2. 5) (5 -1) = 6. 8 + 10 Df. R = df. T – df. M = 23. 60 = 14 – 2 =12 2

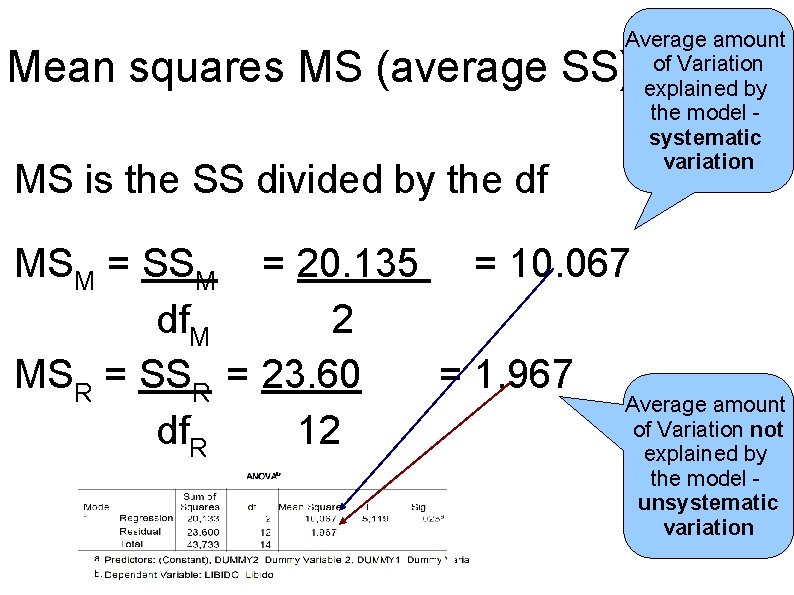

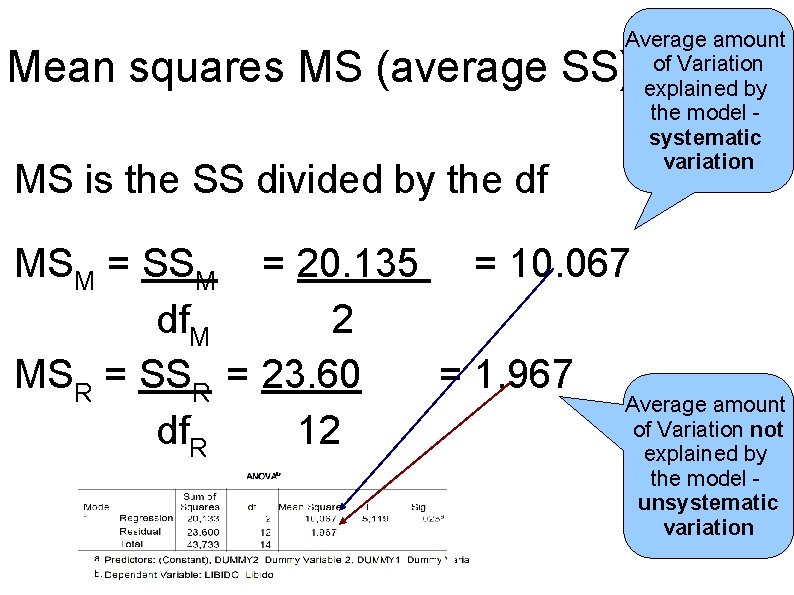

Average amount of Variation explained by the model systematic variation Mean squares MS (average SS) MS is the SS divided by the df MSM = SSM = 20. 135 = 10. 067 df. M 2 MSR = SSR = 23. 60 = 1. 967 Average amount of Variation not df. R 12 explained by the model unsystematic variation

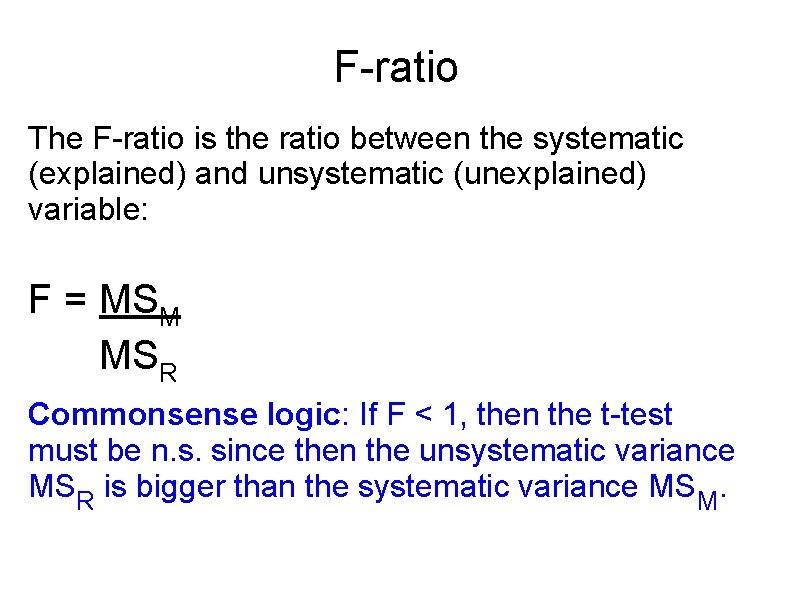

F-ratio The F-ratio is the ratio between the systematic (explained) and unsystematic (unexplained) variable: F = MSM MSR Commonsense logic: If F < 1, then the t-test must be n. s. since then the unsystematic variance MSR is bigger than the systematic variance MSM.

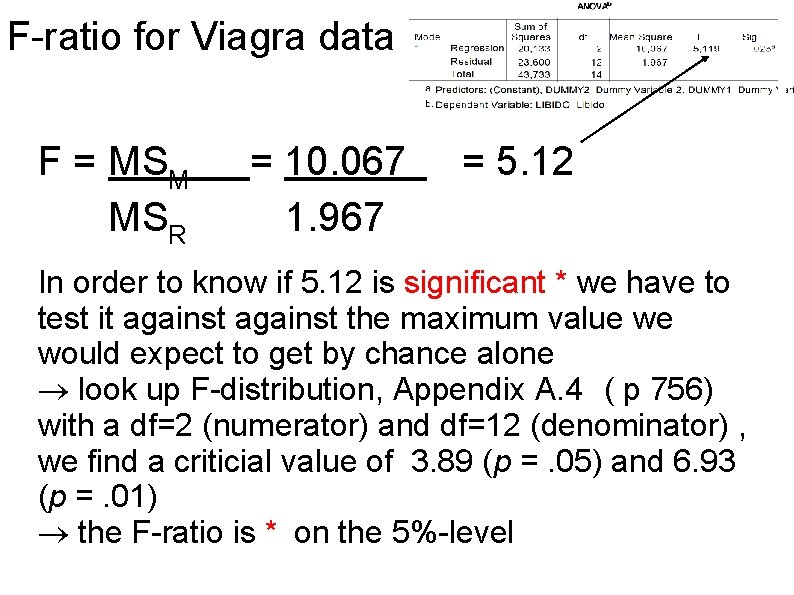

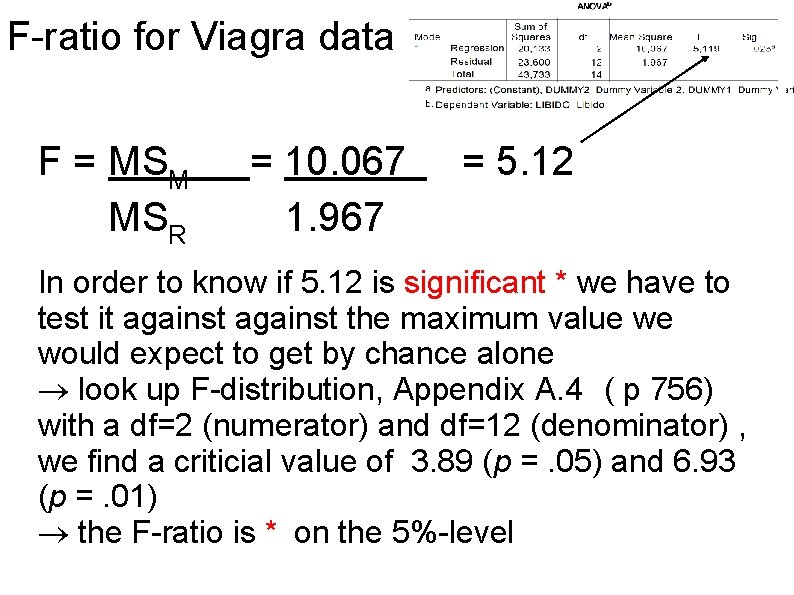

F-ratio for Viagra data F = MSM MSR = 10. 067 1. 967 = 5. 12 In order to know if 5. 12 is significant * we have to test it against the maximum value we would expect to get by chance alone look up F-distribution, Appendix A. 4 ( p 756) with a df=2 (numerator) and df=12 (denominator) , we find a criticial value of 3. 89 (p =. 05) and 6. 93 (p =. 01) the F-ratio is * on the 5%-level

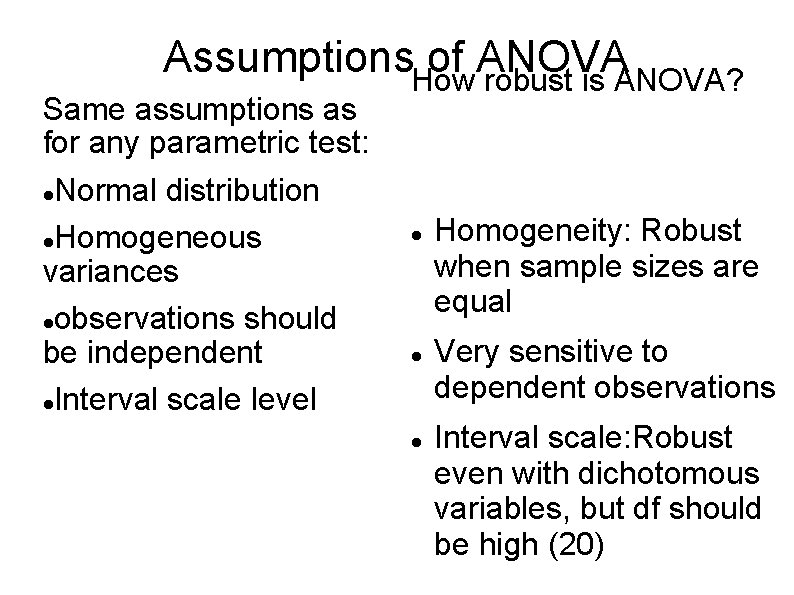

Assumptions. How of ANOVA robust is ANOVA? Same assumptions as for any parametric test: Normal distribution Homogeneous variances observations should be independent Interval scale level Homogeneity: Robust when sample sizes are equal Very sensitive to dependent observations Interval scale: Robust even with dichotomous variables, but df should be high (20)

Planned contrasts – post hoc tests The F-ratio is a global ratio and tells us whethere is a global effect of the experimental treatment, BUT, if the F-value is significant *, it does NOT tell us which differences (bcoefficients) made the effect significant. It could be that b 1 or b 2 or both are * Thus, we need to inquire further Planned comparisons or Post hoc tests

1. Planned contrasts In 'planned contrasts' we break down the overall variance into component parts. It is like conducting a 1 -tailed test, i. e. , when you have a directed hypothesis. Expl. Viagra: 1 st contrast: two drug conditions > placebo 2 nd contrast: high dose > low dose

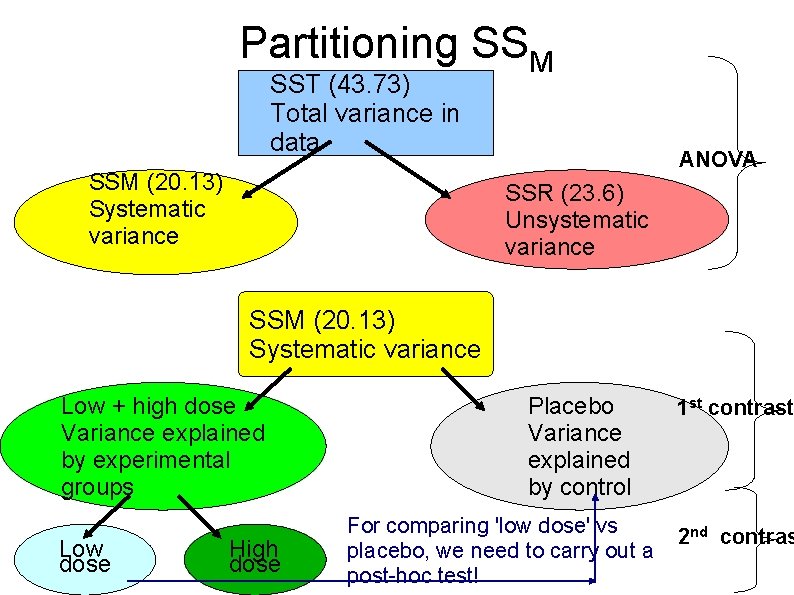

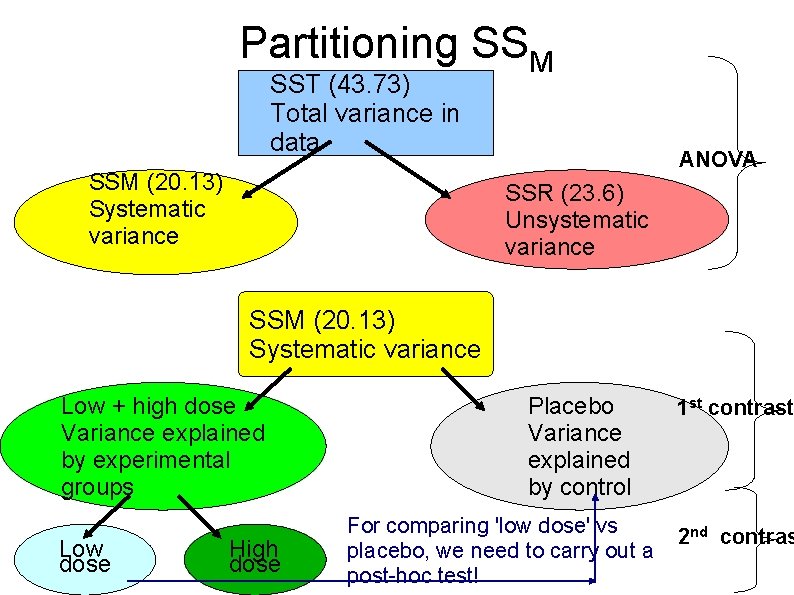

Partitioning SSM SST (43. 73) Total variance in data SSM (20. 13) Systematic variance ANOVA SSR (23. 6) Unsystematic variance SSM (20. 13) Systematic variance Low + high dose Variance explained by experimental groups Low dose High dose Placebo Variance explained by control For comparing 'low dose' vs placebo, we need to carry out a post-hoc test! 1 st contrast 2 nd contras

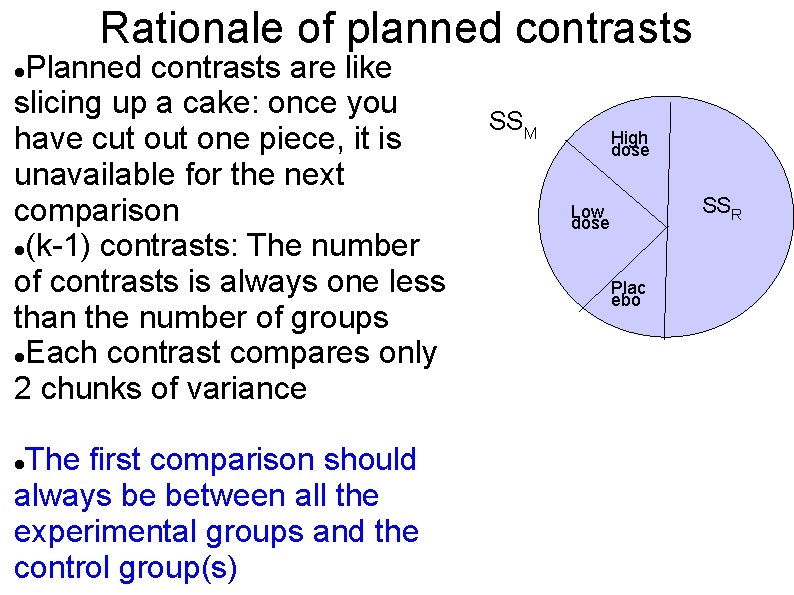

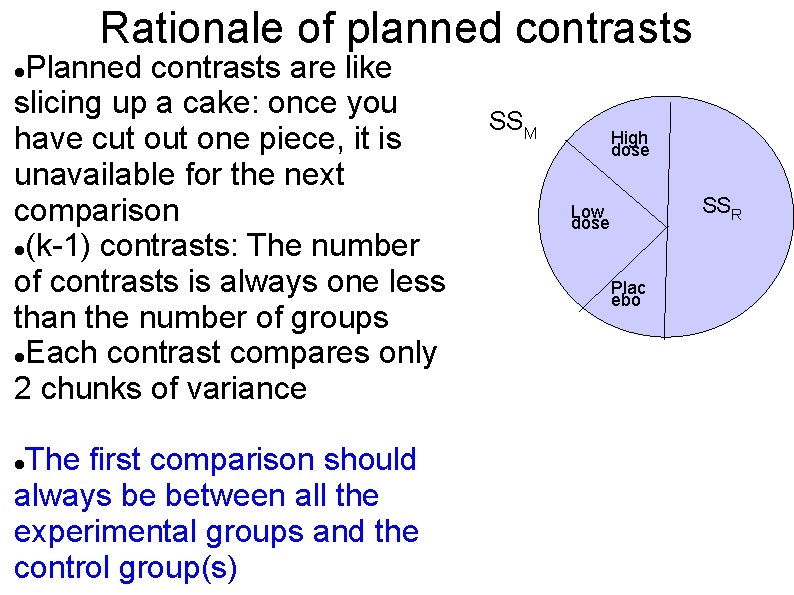

Rationale of planned contrasts Planned contrasts are like slicing up a cake: once you have cut one piece, it is unavailable for the next comparison (k-1) contrasts: The number of contrasts is always one less than the number of groups Each contrast compares only 2 chunks of variance The first comparison should always be between all the experimental groups and the control group(s) SSM High dose SSR Low dose Plac ebo

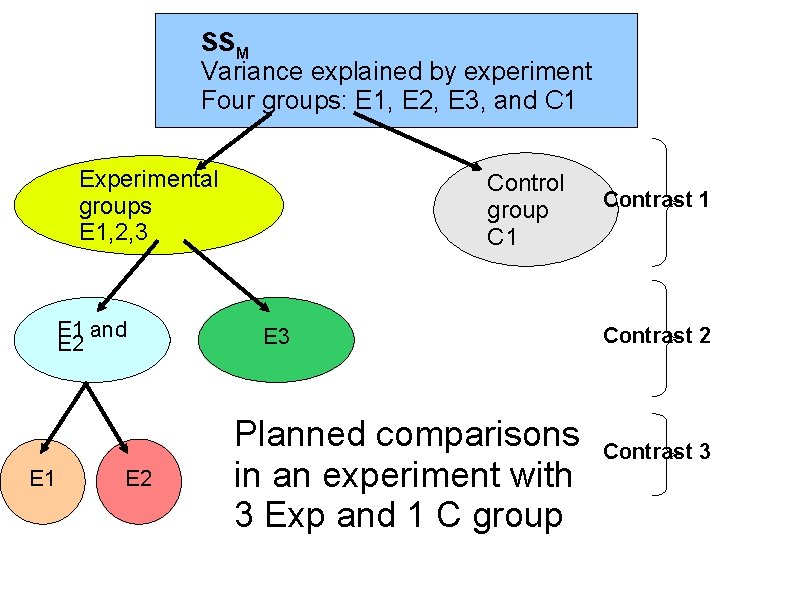

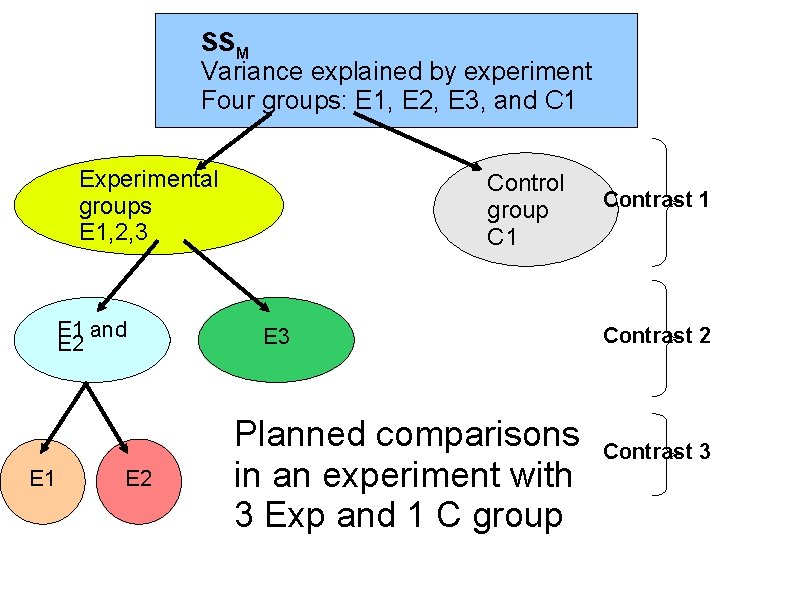

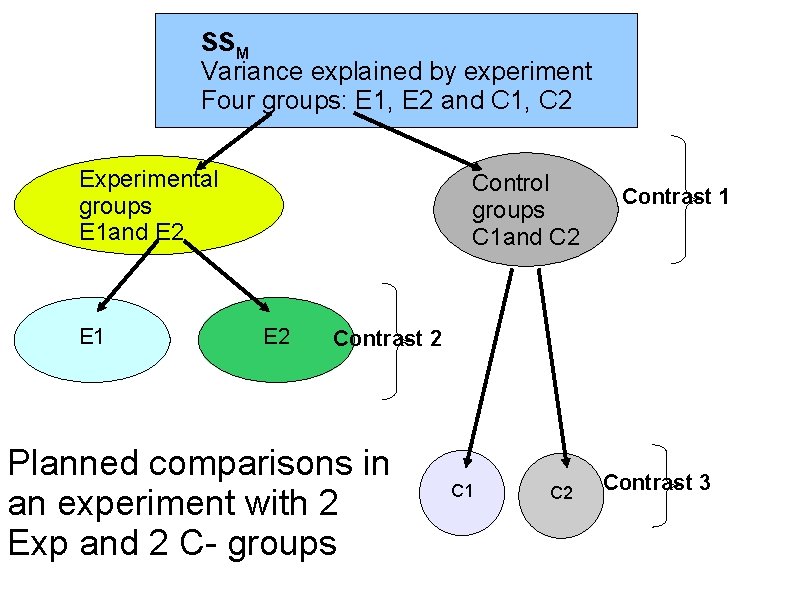

SSM Variance explained by experiment Four groups: E 1, E 2, E 3, and C 1 Experimental groups E 1, 2, 3 E 1 and E 2 E 1 E 2 Control group C 1 E 3 Planned comparisons in an experiment with 3 Exp and 1 C group Contrast 1 Contrast 2 Contrast 3

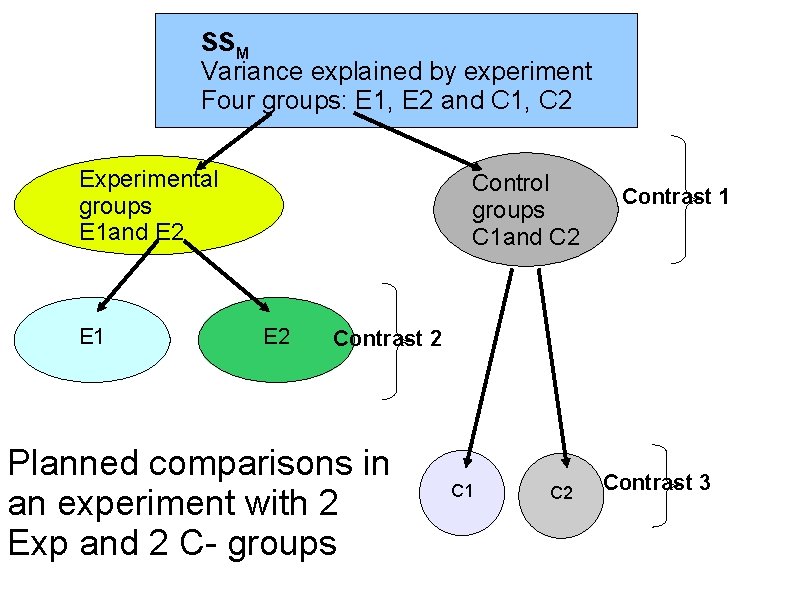

SSM Variance explained by experiment Four groups: E 1, E 2 and C 1, C 2 Experimental groups E 1 and E 2 E 1 Control groups C 1 and C 2 E 2 Contrast 1 Contrast 2 Planned comparisons in an experiment with 2 Exp and 2 C- groups C 1 C 2 Contrast 3

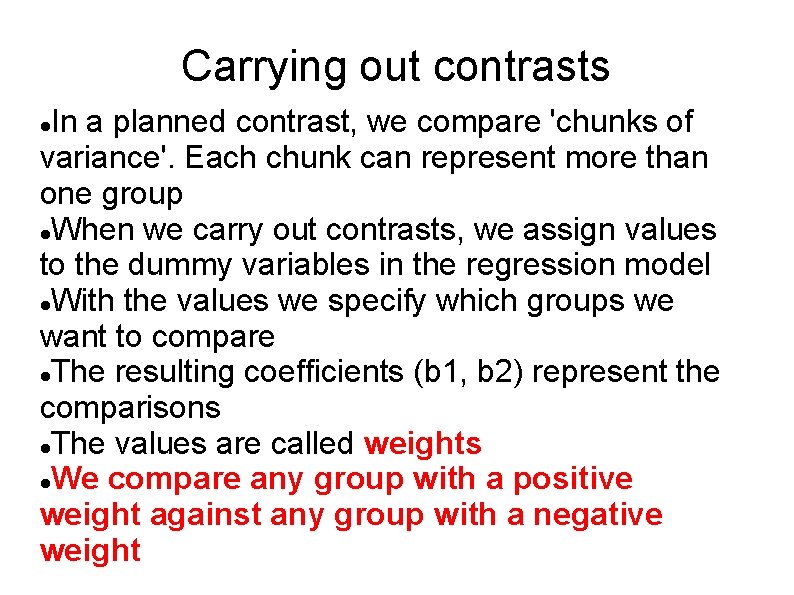

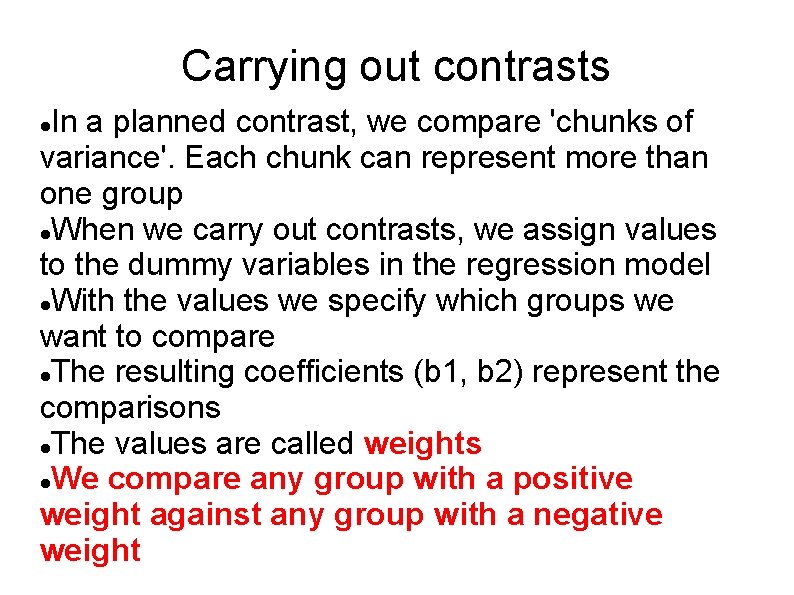

Carrying out contrasts In a planned contrast, we compare 'chunks of variance'. Each chunk can represent more than one group When we carry out contrasts, we assign values to the dummy variables in the regression model With the values we specify which groups we want to compare The resulting coefficients (b 1, b 2) represent the comparisons The values are called weights We compare any group with a positive weight against any group with a negative weight

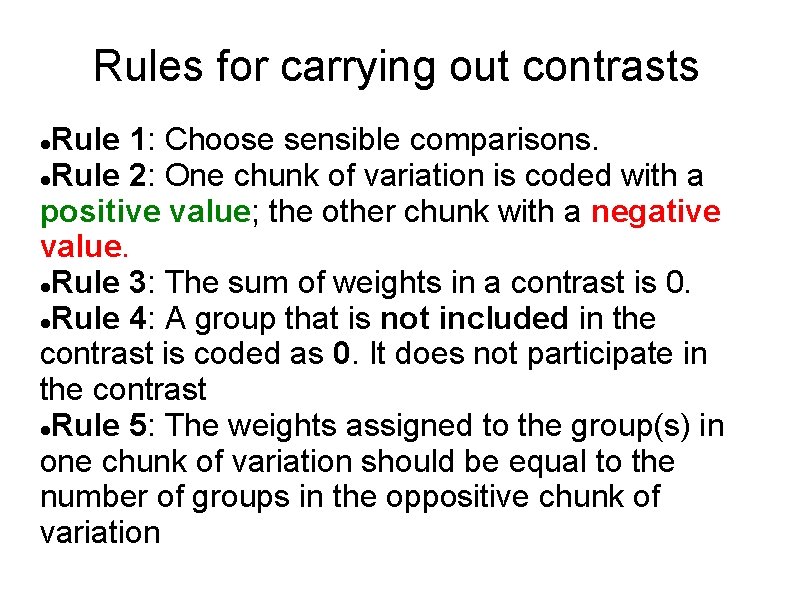

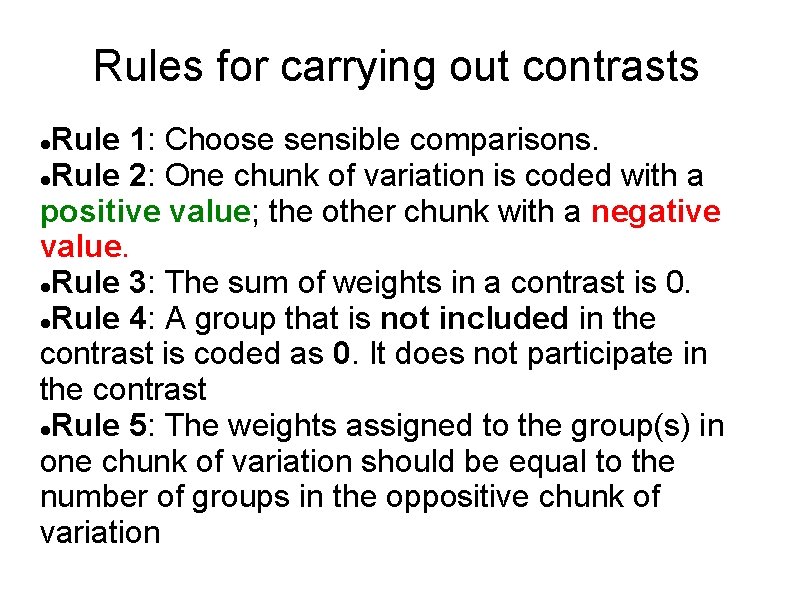

Rules for carrying out contrasts Rule 1: Choose sensible comparisons. Rule 2: One chunk of variation is coded with a positive value; the other chunk with a negative value. Rule 3: The sum of weights in a contrast is 0. Rule 4: A group that is not included in the contrast is coded as 0. It does not participate in the contrast Rule 5: The weights assigned to the group(s) in one chunk of variation should be equal to the number of groups in the oppositive chunk of variation

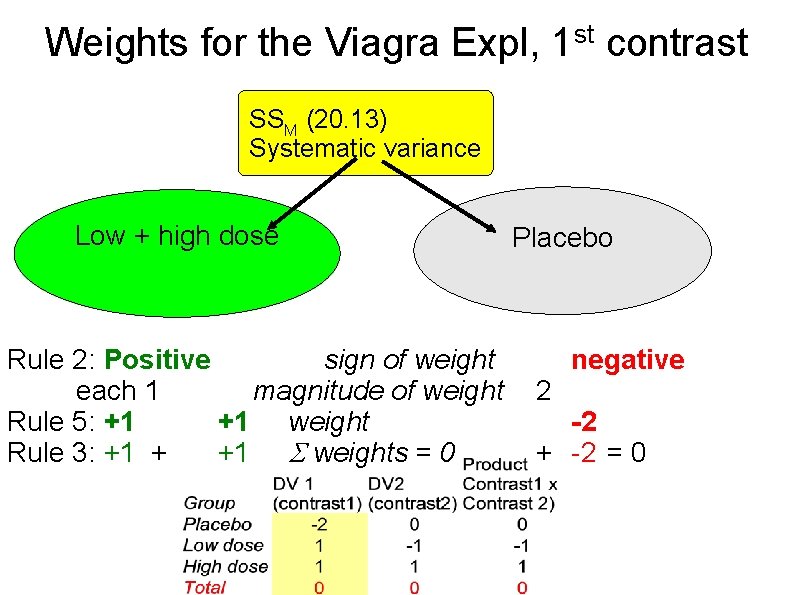

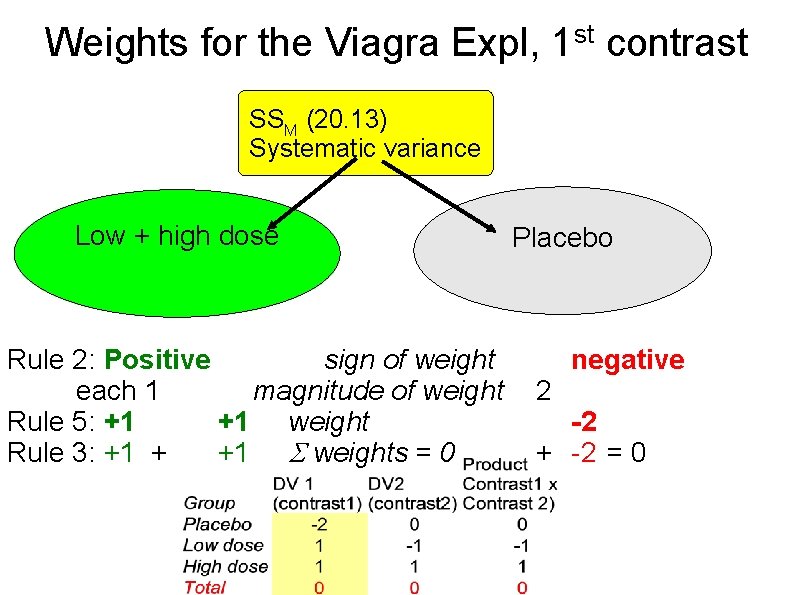

st Weights for the Viagra Expl, 1 contrast SSM (20. 13) Systematic variance Low + high dose Rule 2: Positive sign of weight each 1 magnitude of weight Rule 5: +1 +1 weight Rule 3: +1 + +1 weights = 0 Placebo negative 2 -2 + -2 = 0

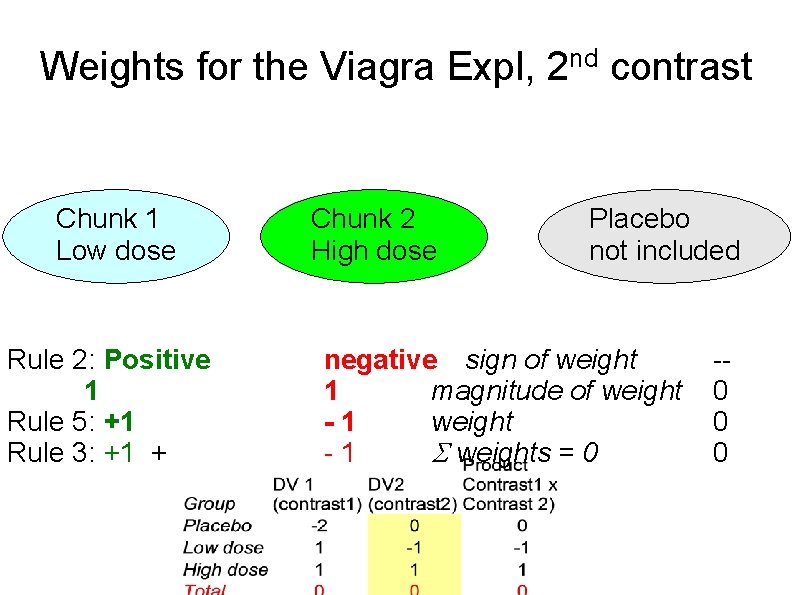

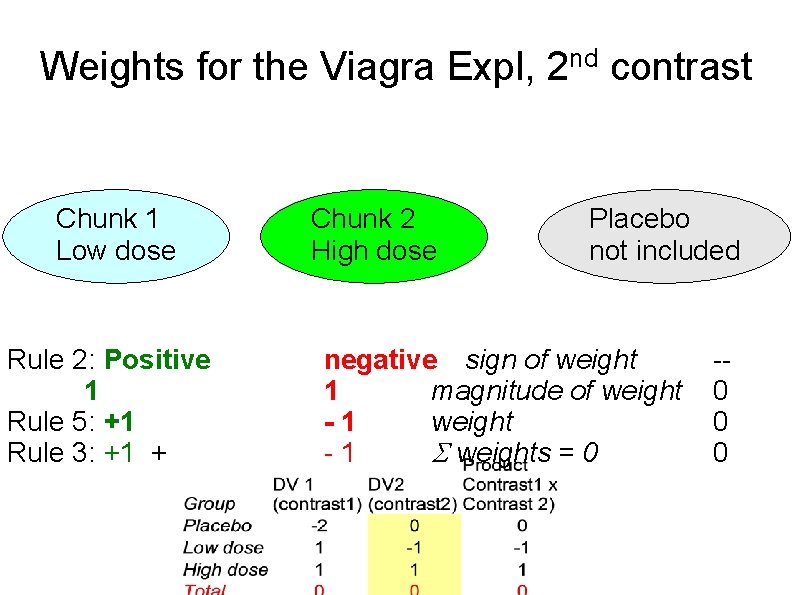

Weights for the Viagra Expl, 2 Chunk 1 Low dose Rule 2: Positive 1 Rule 5: +1 Rule 3: +1 + Chunk 2 High dose nd contrast Placebo not included negative sign of weight 1 magnitude of weight -1 weights = 0 -0 0 0

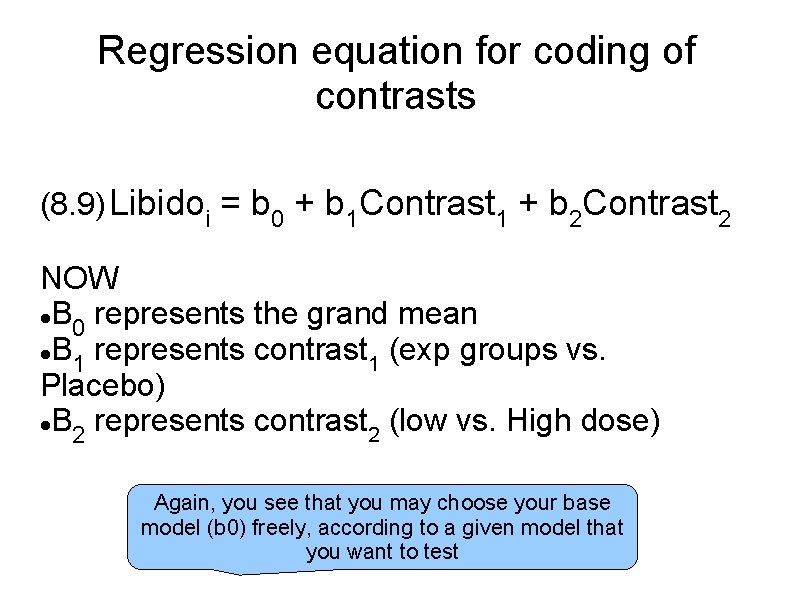

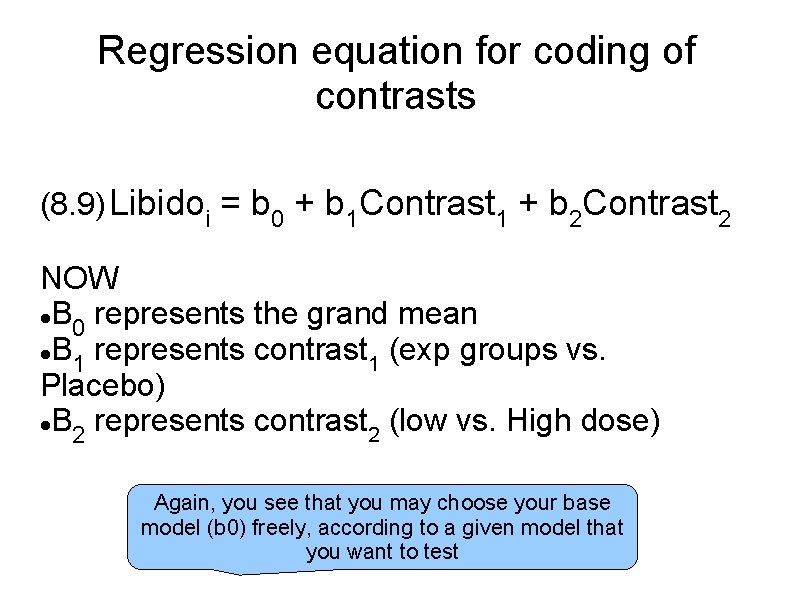

Regression equation for coding of contrasts (8. 9) Libidoi = b 0 + b 1 Contrast 1 + b 2 Contrast 2 NOW B represents the grand mean 0 B represents contrast (exp groups vs. 1 1 Placebo) B represents contrast (low vs. High dose) 2 2 Again, you see that you may choose your base model (b 0) freely, according to a given model that you want to test

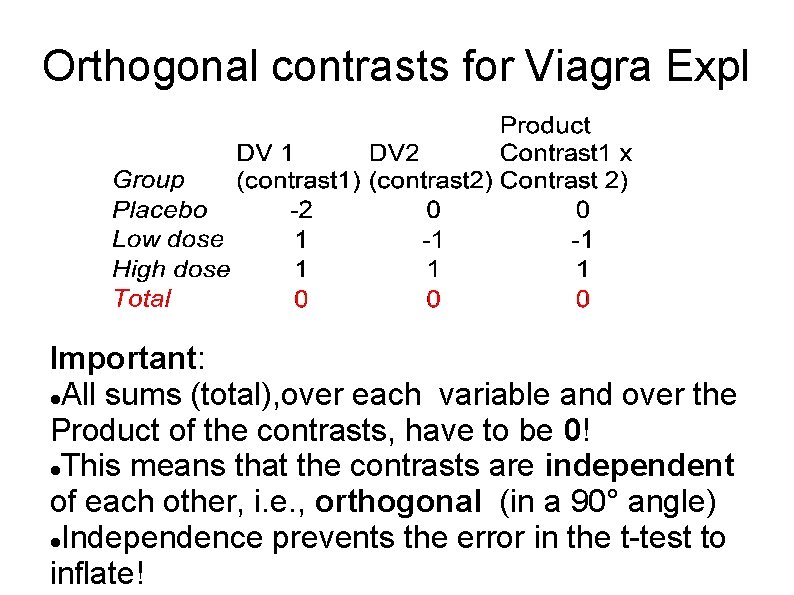

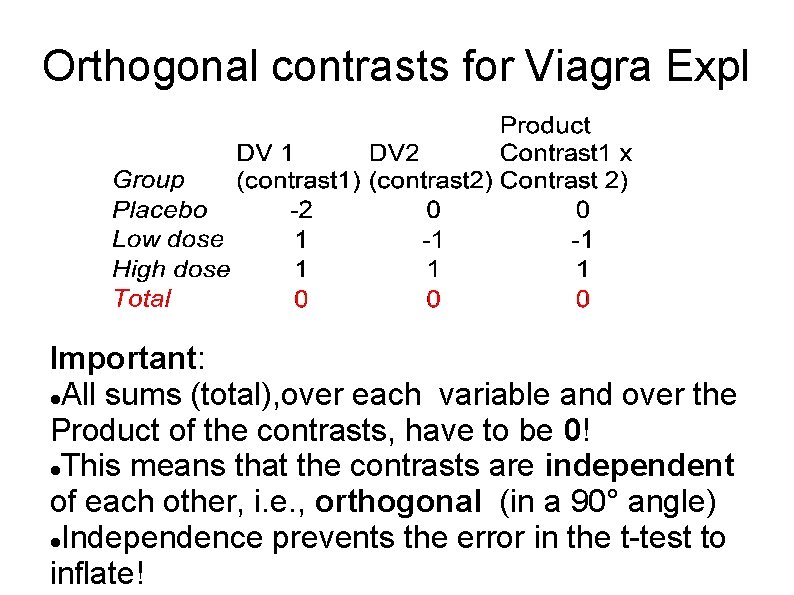

Orthogonal contrasts for Viagra Expl Important: All sums (total), over each variable and over the Product of the contrasts, have to be 0! This means that the contrasts are independent of each other, i. e. , orthogonal (in a 90° angle) Independence prevents the error in the t-test to inflate!

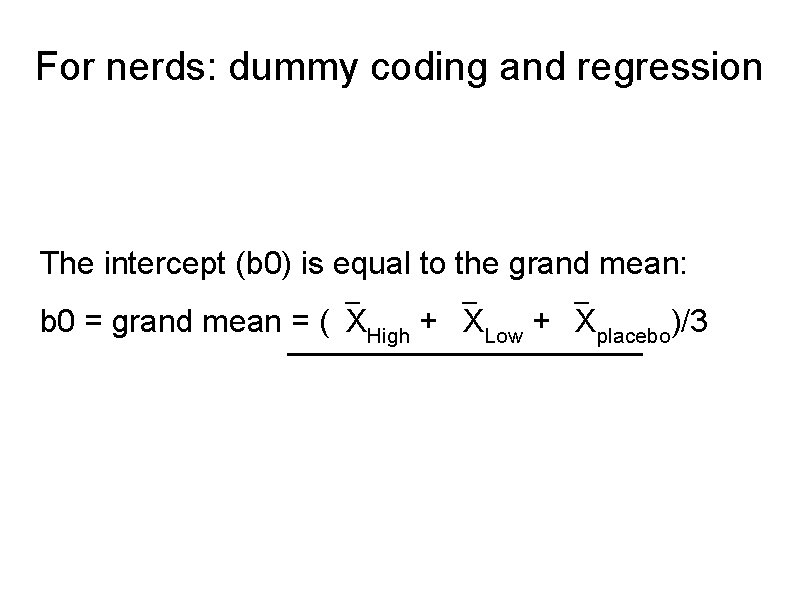

For nerds: dummy coding and regression The intercept (b 0) is equal to the grand mean: b 0 = grand mean = ( XHigh + XLow + Xplacebo)/3

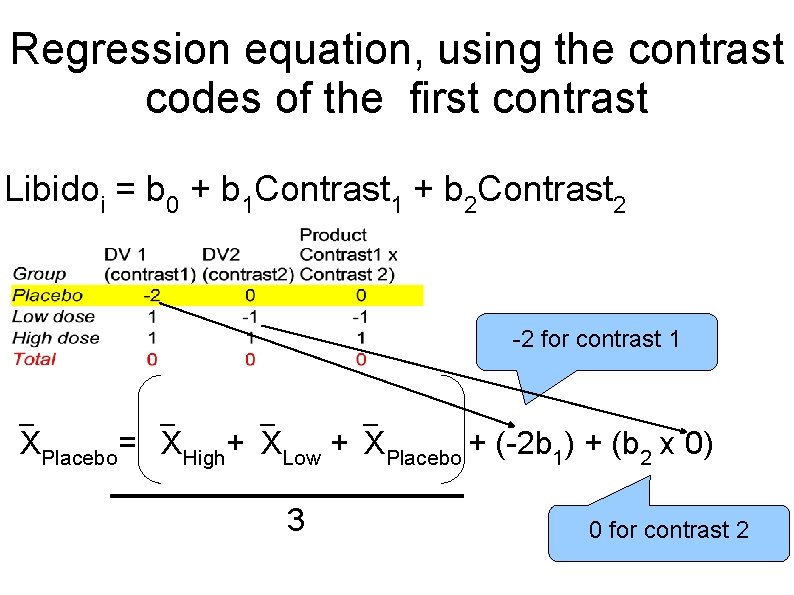

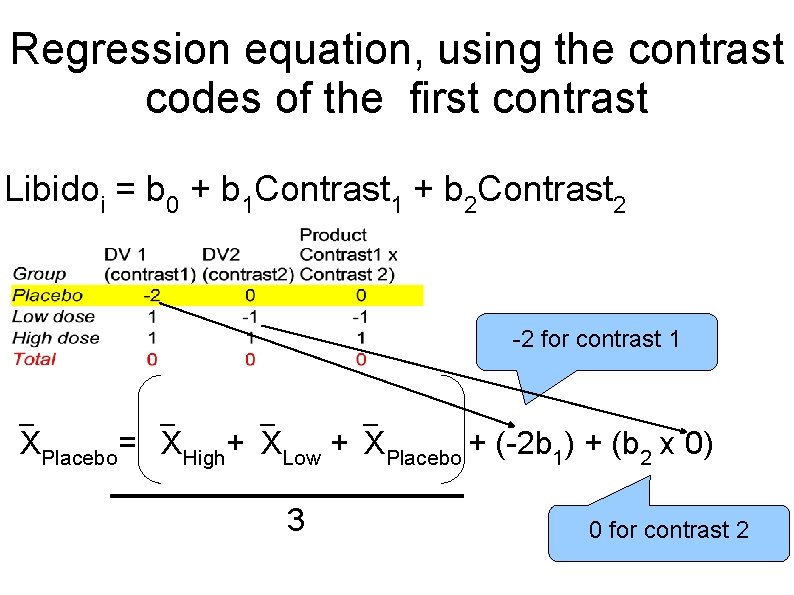

Regression equation, using the contrast codes of the first contrast Libidoi = b 0 + b 1 Contrast 1 + b 2 Contrast 2 -2 for contrast 1 XPlacebo= XHigh+ XLow + XPlacebo + (-2 b 1) + (b 2 x 0) 3 0 for contrast 2

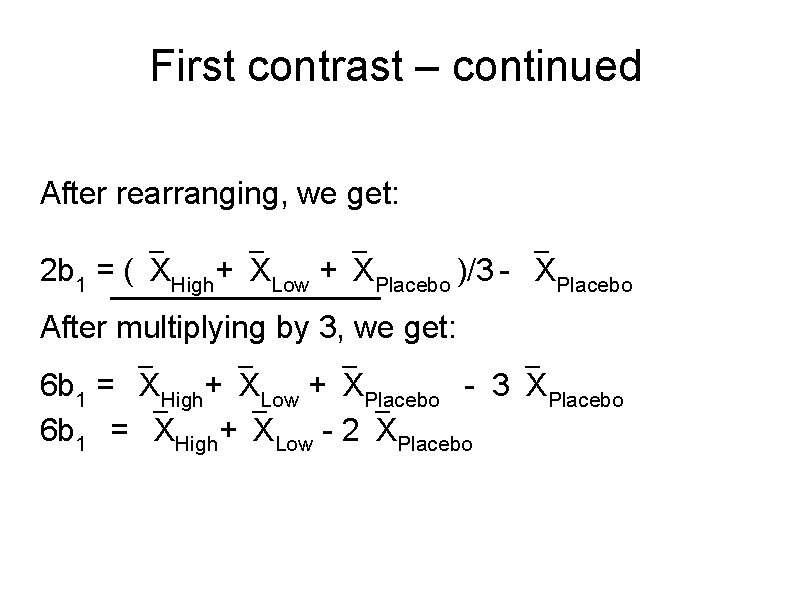

First contrast – continued After rearranging, we get: 2 b 1 = ( XHigh+ XLow + XPlacebo )/3 - XPlacebo After multiplying by 3, we get: 6 b 1 = XHigh+ XLow + XPlacebo - 3 XPlacebo 6 b 1 = XHigh+ XLow - 2 XPlacebo

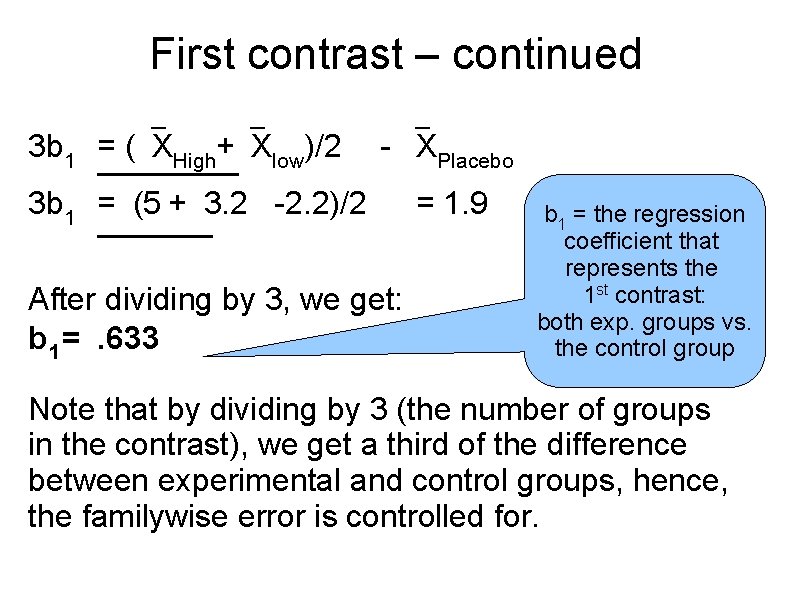

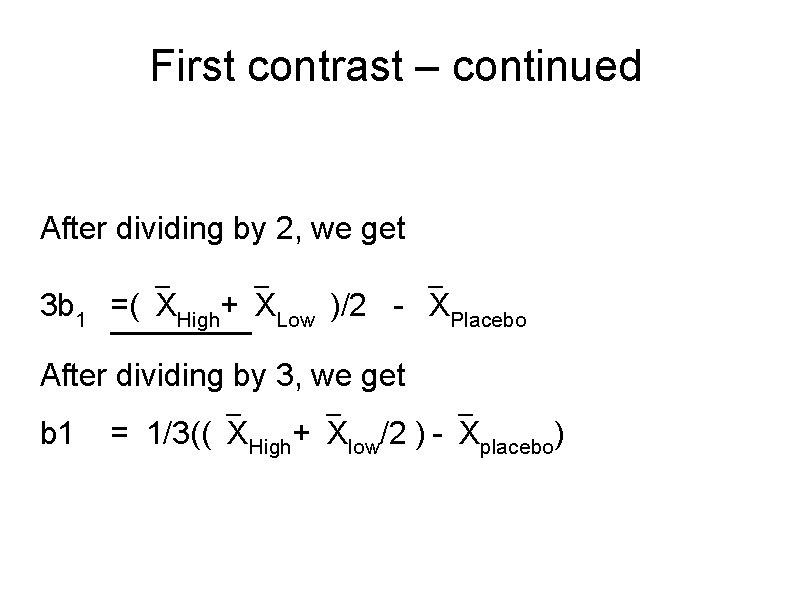

First contrast – continued After dividing by 2, we get 3 b 1 =( XHigh+ XLow )/2 - XPlacebo After dividing by 3, we get b 1 = 1/3(( XHigh+ Xlow/2 ) - Xplacebo)

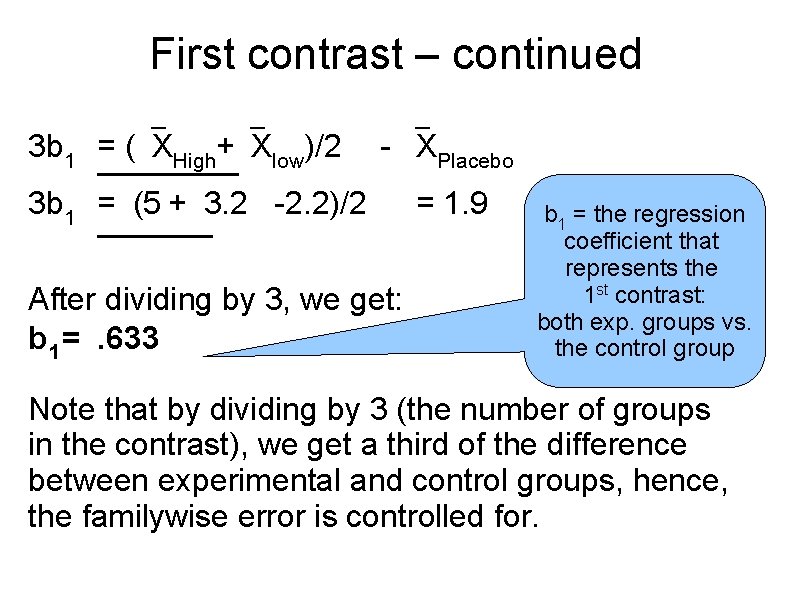

First contrast – continued 3 b 1 = ( XHigh+ Xlow)/2 - XPlacebo 3 b 1 = (5 + 3. 2 -2. 2)/2 After dividing by 3, we get: b 1 =. 633 = 1. 9 b 1 = the regression coefficient that represents the 1 st contrast: both exp. groups vs. the control group Note that by dividing by 3 (the number of groups in the contrast), we get a third of the difference between experimental and control groups, hence, the familywise error is controlled for.

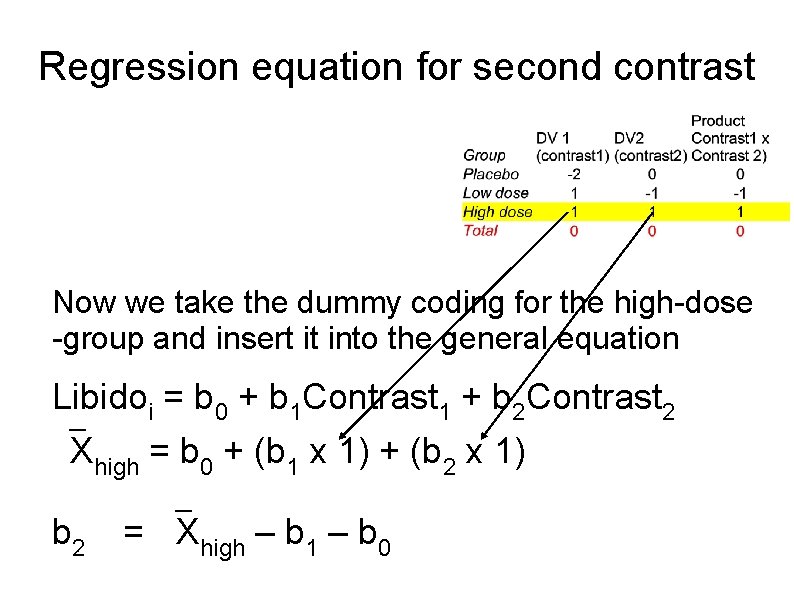

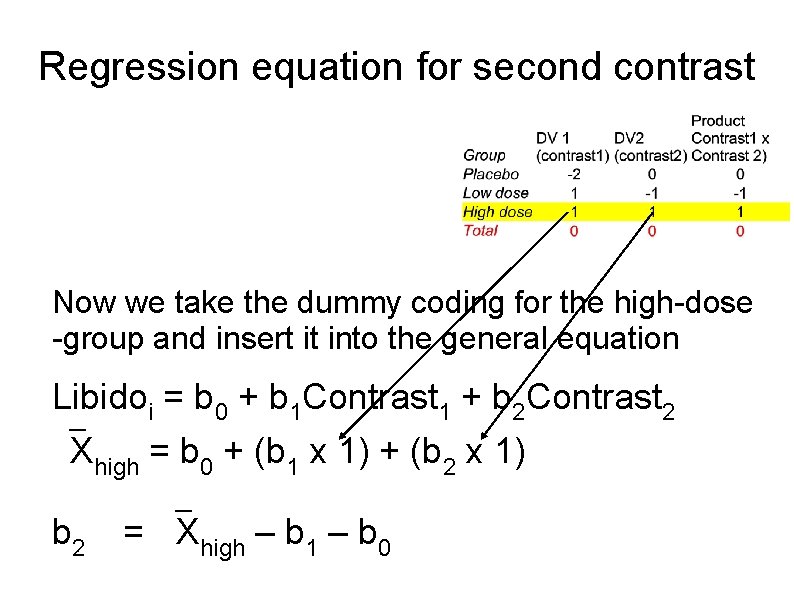

Regression equation for second contrast Now we take the dummy coding for the high-dose -group and insert it into the general equation Libidoi = b 0 + b 1 Contrast 1 + b 2 Contrast 2 Xhigh = b 0 + (b 1 x 1) + (b 2 x 1) b 2 = Xhigh – b 1 – b 0

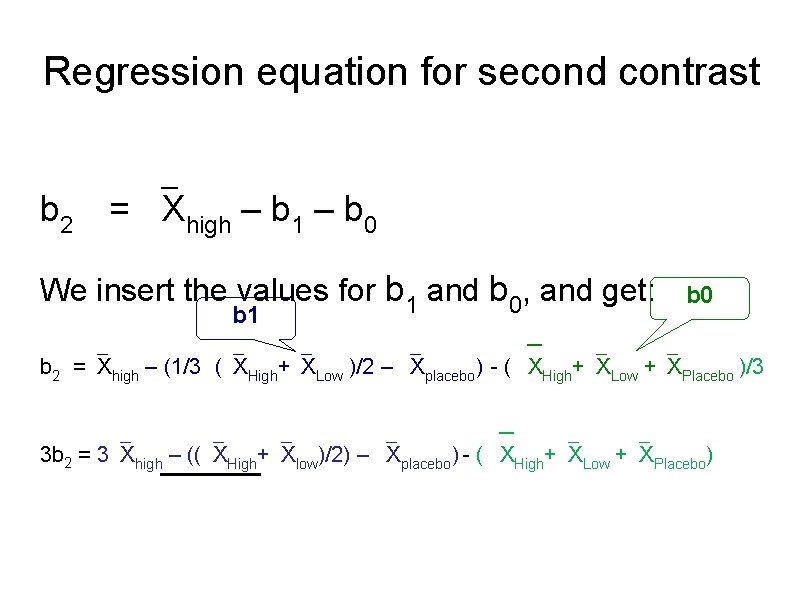

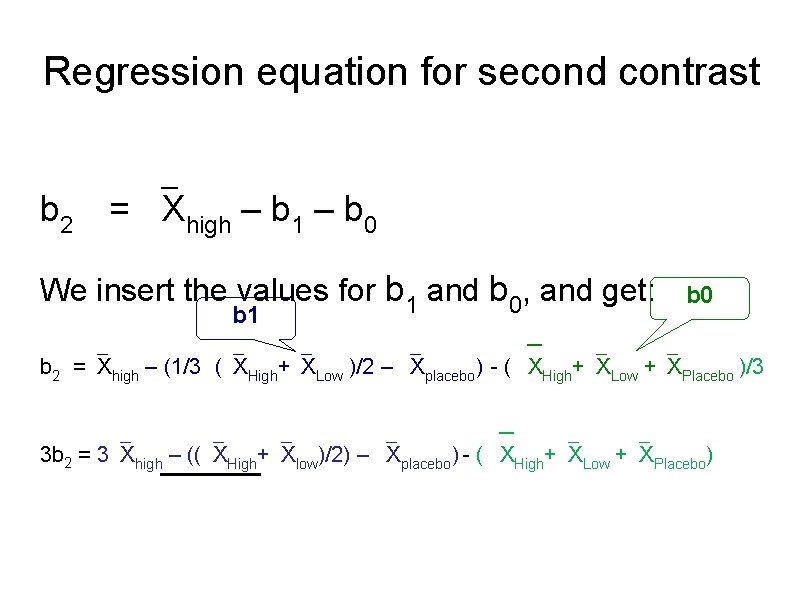

Regression equation for second contrast b 2 = Xhigh – b 1 – b 0 We insert the values for b 1 and b 0, and get: b 1 b 0 b 2 = Xhigh – (1/3 ( XHigh+ XLow )/2 – Xplacebo) - ( XHigh+ XLow + XPlacebo )/3 3 b 2 = 3 Xhigh – (( XHigh+ Xlow)/2) – Xplacebo) - ( XHigh+ XLow + XPlacebo)

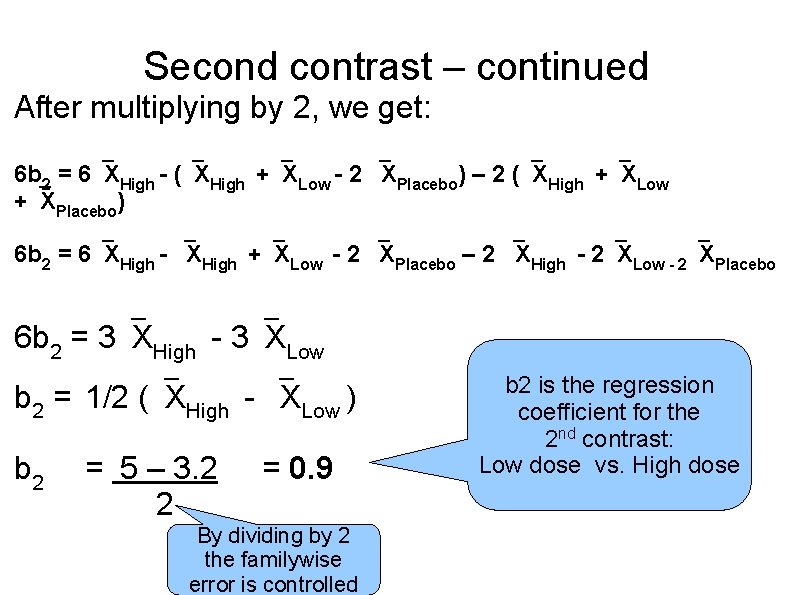

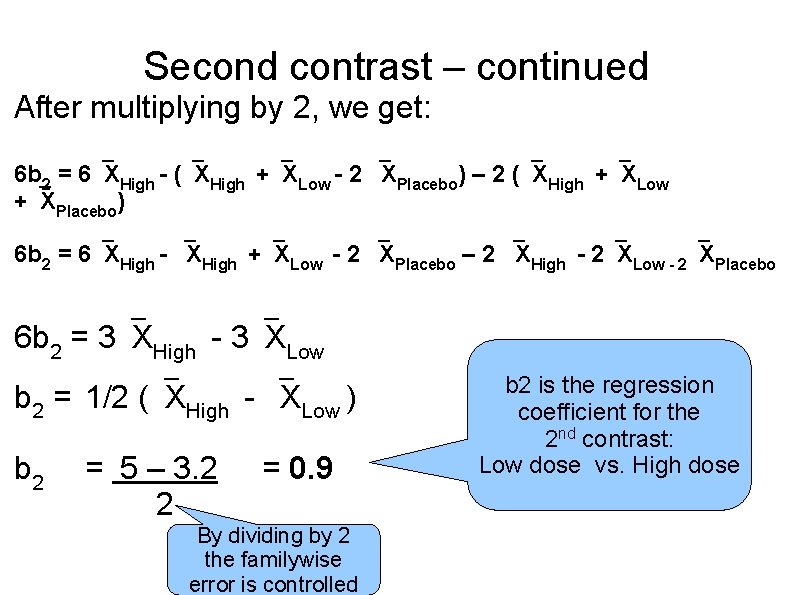

Second contrast – continued After multiplying by 2, we get: 6 b 2 = 6 XHigh - ( XHigh + XLow - 2 XPlacebo) – 2 ( XHigh + XLow + XPlacebo) 6 b 2 = 6 XHigh - XHigh + XLow - 2 XPlacebo – 2 XHigh - 2 XLow - 2 XPlacebo 6 b 2 = 3 XHigh - 3 XLow b 2 = 1/2 ( XHigh - XLow ) b 2 = 5 – 3. 2 2 = 0. 9 By dividing by 2 the familywise error is controlled b 2 is the regression coefficient for the 2 nd contrast: Low dose vs. High dose

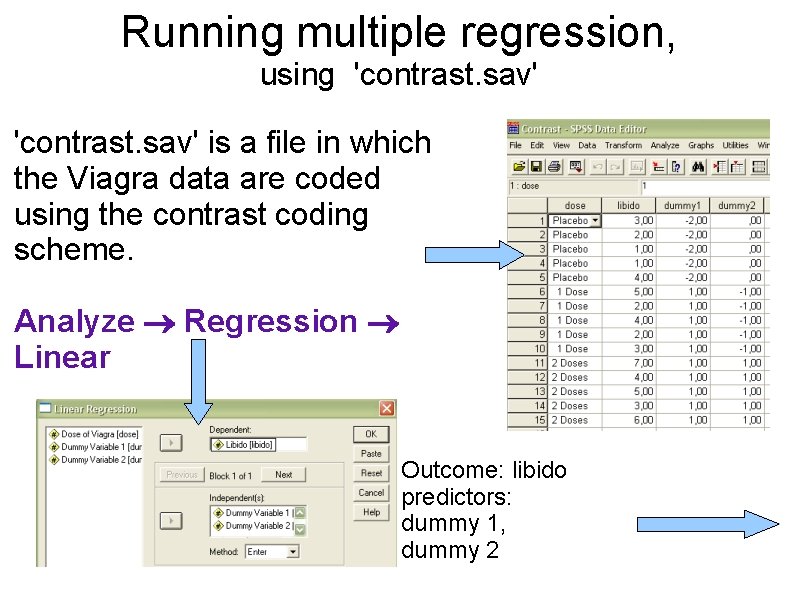

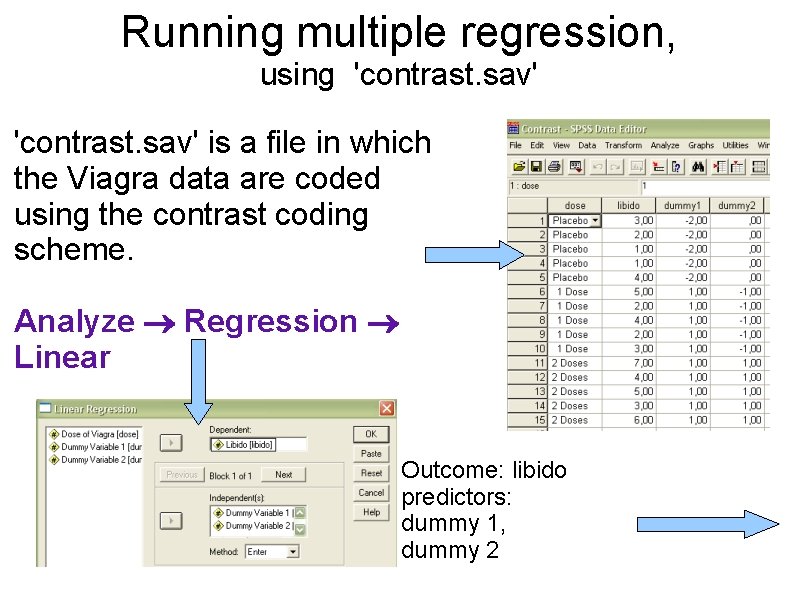

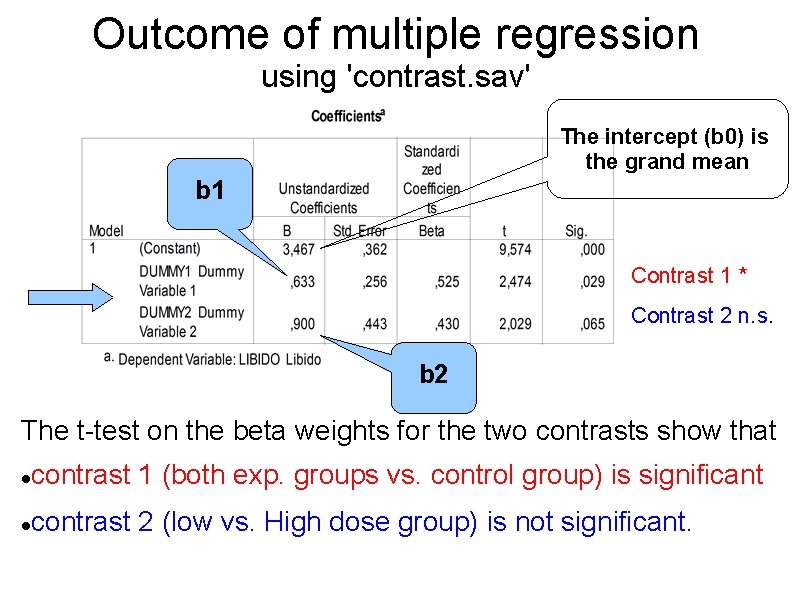

Running multiple regression, using 'contrast. sav' is a file in which the Viagra data are coded using the contrast coding scheme. Analyze Regression Linear Outcome: libido predictors: dummy 1, dummy 2

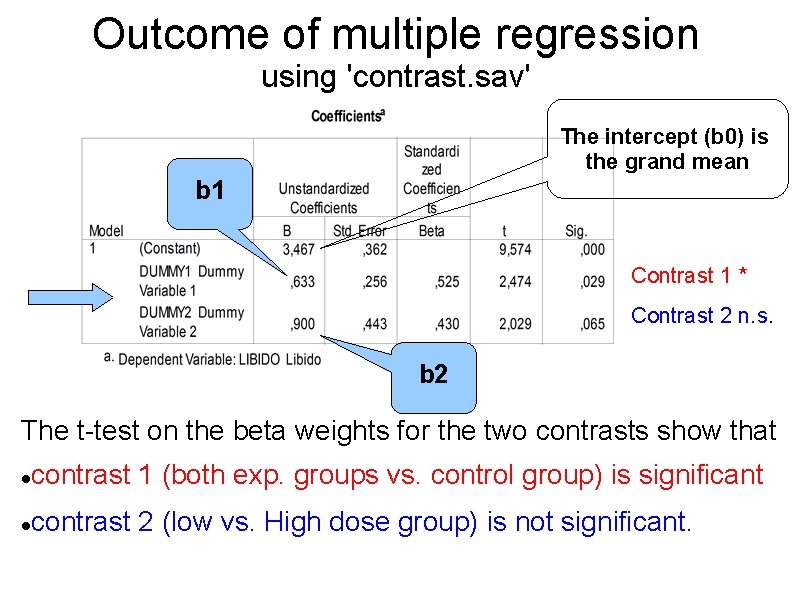

Outcome of multiple regression using 'contrast. sav' The intercept (b 0) is the grand mean b 1 Contrast 1 * Contrast 2 n. s. b 2 The t-test on the beta weights for the two contrasts show that contrast 1 (both exp. groups vs. control group) is significant contrast 2 (low vs. High dose group) is not significant.

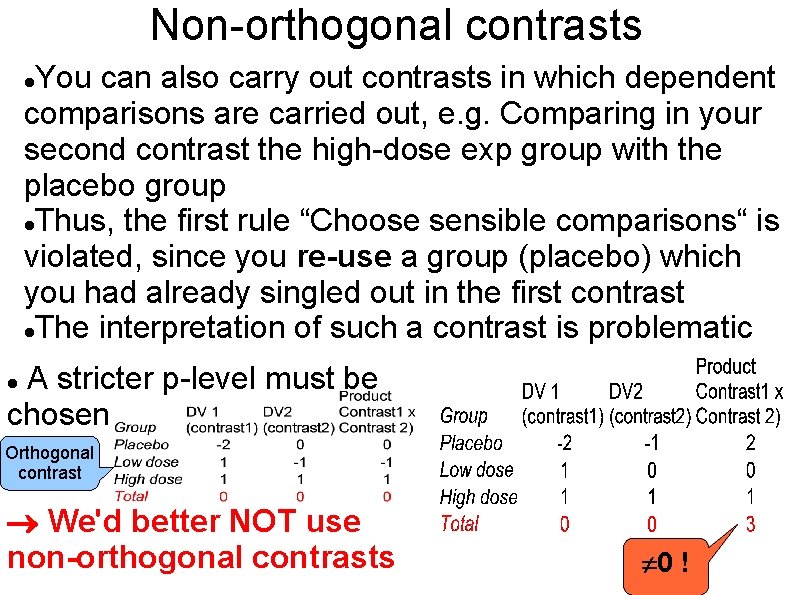

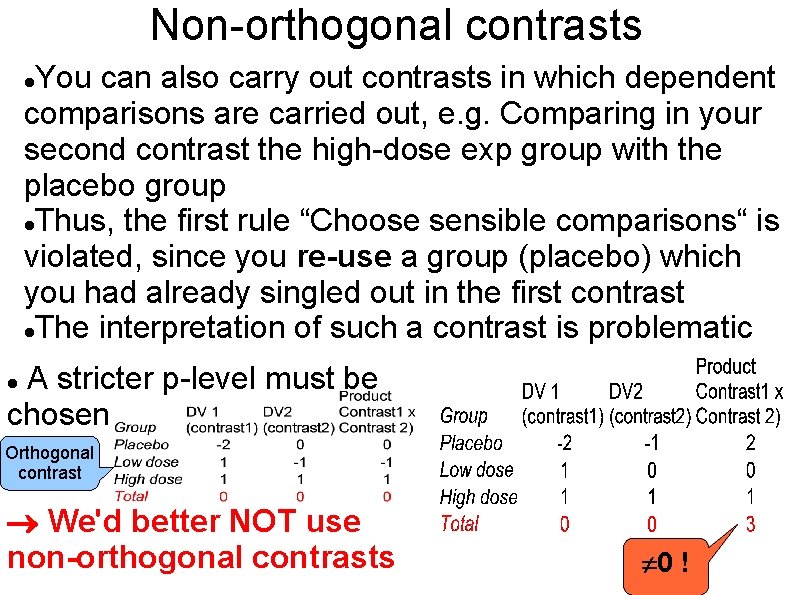

Non-orthogonal contrasts You can also carry out contrasts in which dependent comparisons are carried out, e. g. Comparing in your second contrast the high-dose exp group with the placebo group Thus, the first rule “Choose sensible comparisons“ is violated, since you re-use a group (placebo) which you had already singled out in the first contrast The interpretation of such a contrast is problematic A stricter p-level must be chosen Orthogonal contrast We'd better NOT use non-orthogonal contrasts 0 !

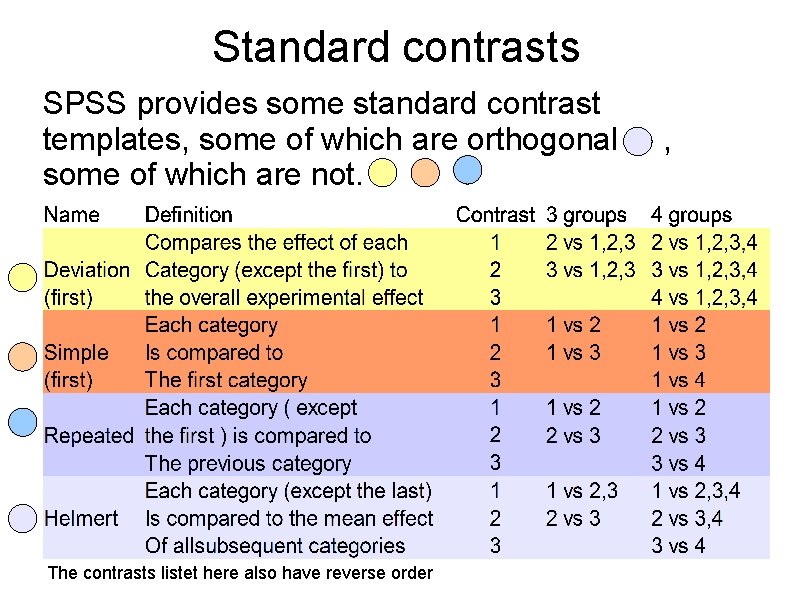

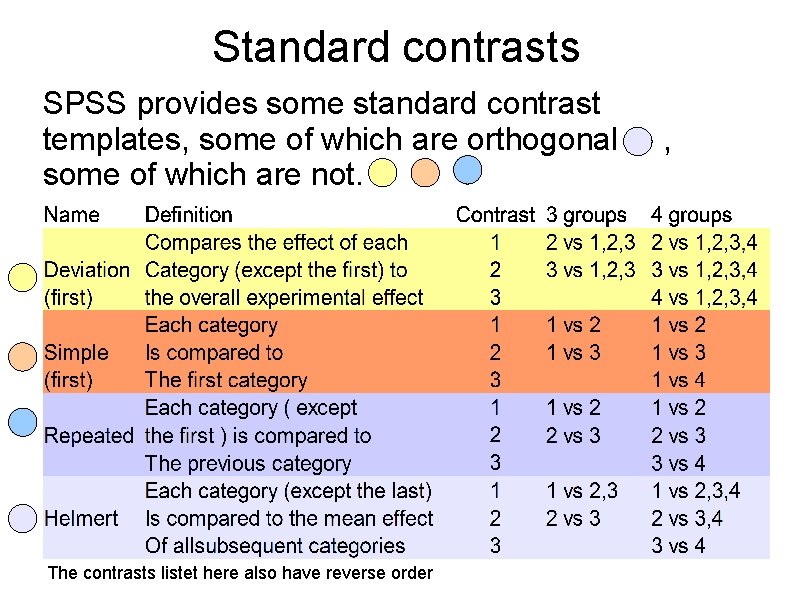

Standard contrasts SPSS provides some standard contrast templates, some of which are orthogonal some of which are not. The contrasts listet here also have reverse order ,

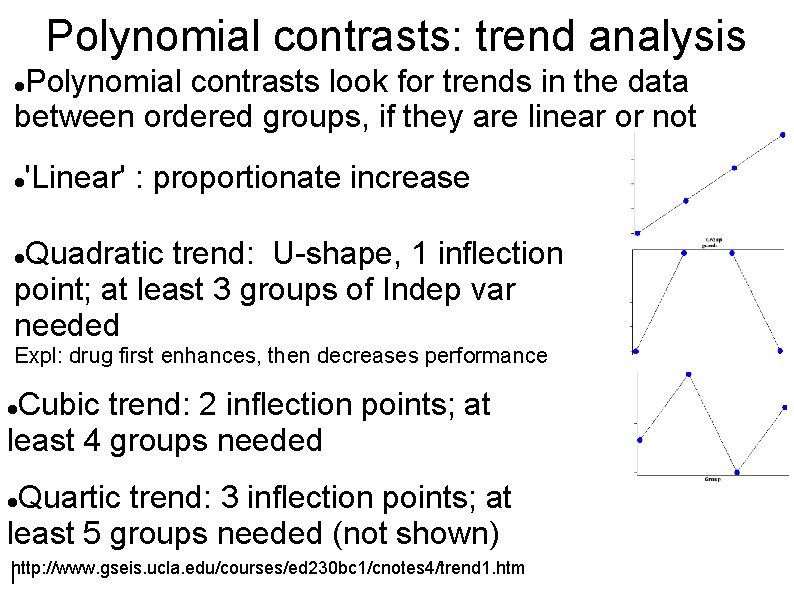

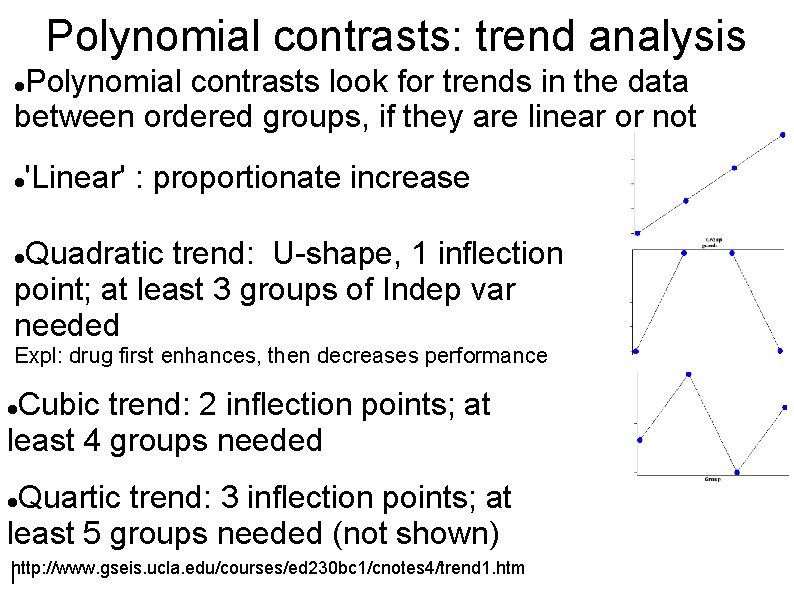

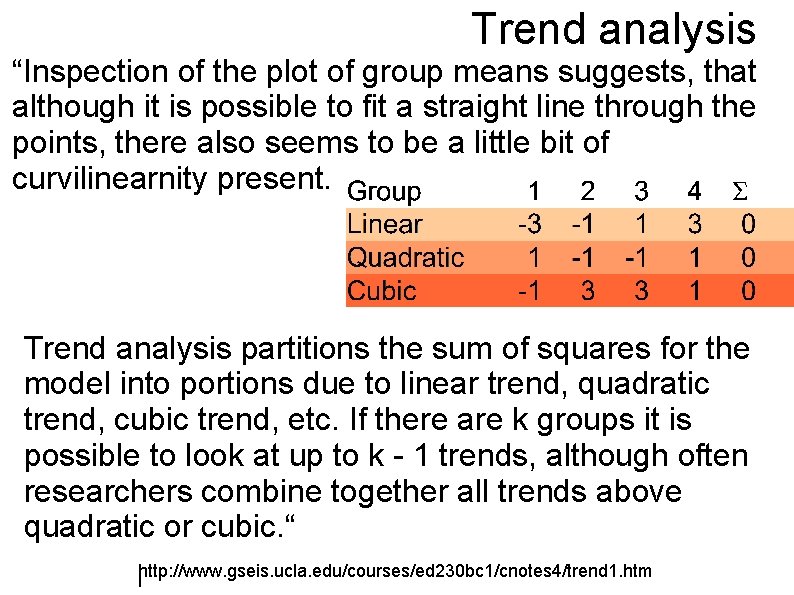

Polynomial contrasts: trend analysis Polynomial contrasts look for trends in the data between ordered groups, if they are linear or not 'Linear' : proportionate increase Quadratic trend: U-shape, 1 inflection point; at least 3 groups of Indep var needed Expl: drug first enhances, then decreases performance Cubic trend: 2 inflection points; at least 4 groups needed Quartic trend: 3 inflection points; at least 5 groups needed (not shown) http: //www. gseis. ucla. edu/courses/ed 230 bc 1/cnotes 4/trend 1. htm l

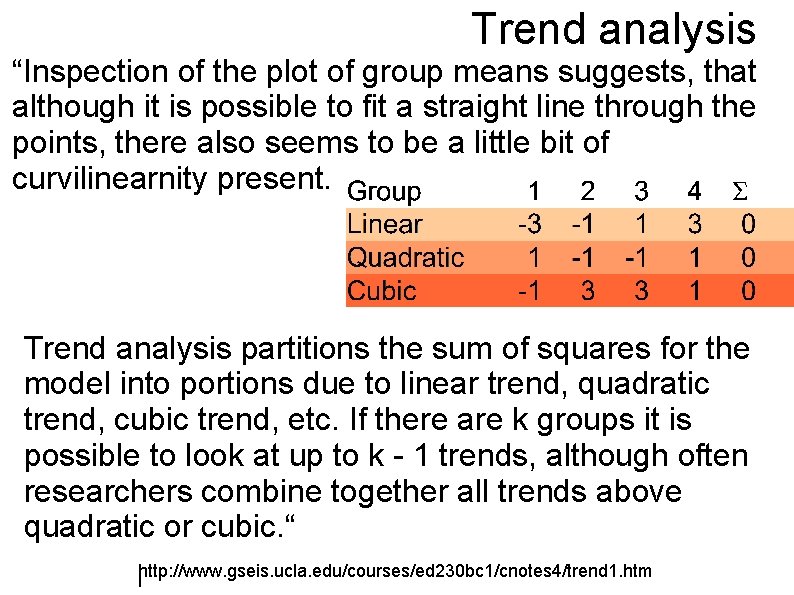

Trend analysis “Inspection of the plot of group means suggests, that although it is possible to fit a straight line through the points, there also seems to be a little bit of curvilinearnity present. Trend analysis partitions the sum of squares for the model into portions due to linear trend, quadratic trend, cubic trend, etc. If there are k groups it is possible to look at up to k - 1 trends, although often researchers combine together all trends above quadratic or cubic. “ http: //www. gseis. ucla. edu/courses/ed 230 bc 1/cnotes 4/trend 1. htm l

Post-hoc procedures When you do not have a prediction about which groups will contrast in what way, you might want to explore any difference between groups that exists. Then you do an exploratory data analysis or data mining. Posthoc tests are a suitable way to do pairwise comparisons between all different combinations of groups. On each of those pairs, a t-test is performed.

Keeping the familywise -error small Problem: with each pairwise test, the familywise error rate increases. Solution: dividing by the number of comparisons. Example: If we do 10 comparisons and want to maintain an overall -level of 0. 05, we have to conduct single comparisons at the 0. 005 level. This procedure is called Bonferroni correction. Problem: we loose statistical power by raising the error (erroneously rejecting our exp. hypothesis)

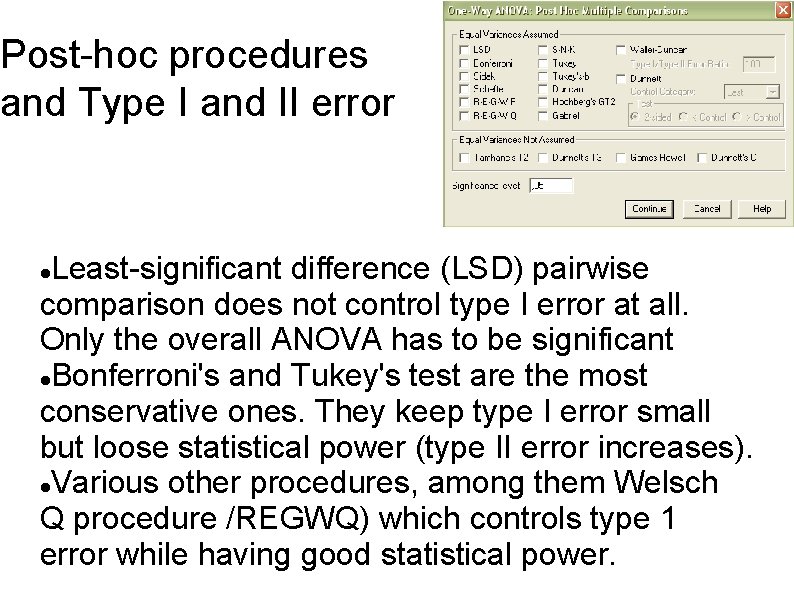

Post-hoc procedures and Type I and II error Least-significant difference (LSD) pairwise comparison does not control type I error at all. Only the overall ANOVA has to be significant Bonferroni's and Tukey's test are the most conservative ones. They keep type I error small but loose statistical power (type II error increases). Various other procedures, among them Welsch Q procedure /REGWQ) which controls type 1 error while having good statistical power.

Post-hoc procedures and violations of assumptions What if between the groups the assumptions are not met (normality, equality of variance)? Most multiple comparison procedures tolerate small deviations from normality They do not tolerate unequal group sizes and different population variances SPSS has 4 tests for dealing with different population variances: Tamhane's T 2, Dunnett's T 3, Games-Howell, Dunnet's C

Guidelines for post hoc comparisons When the sample sizes are equal and population variances similar: REGWQ or Tukey Take Bonferroni if you want to cotrol Type I error tightly When sample sizes differ: Gabriel's procedure When equality of variances is doubtful: Games. Howell

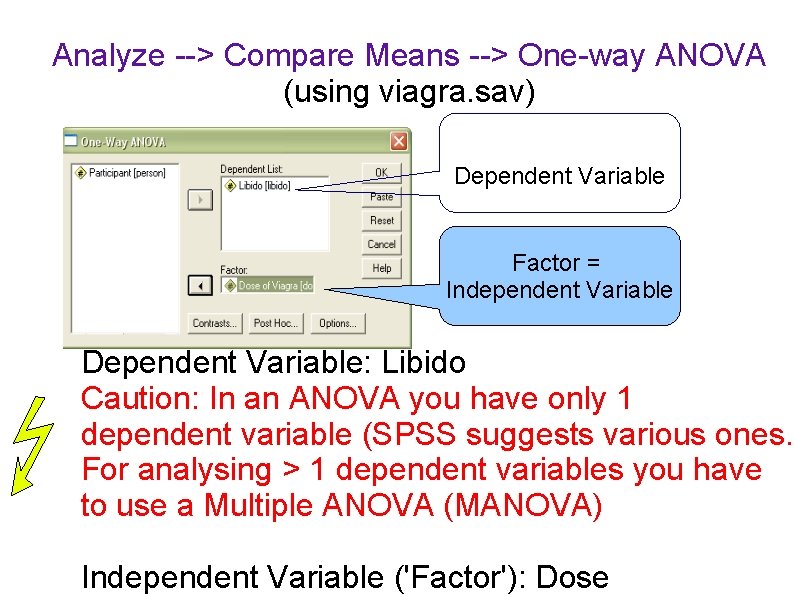

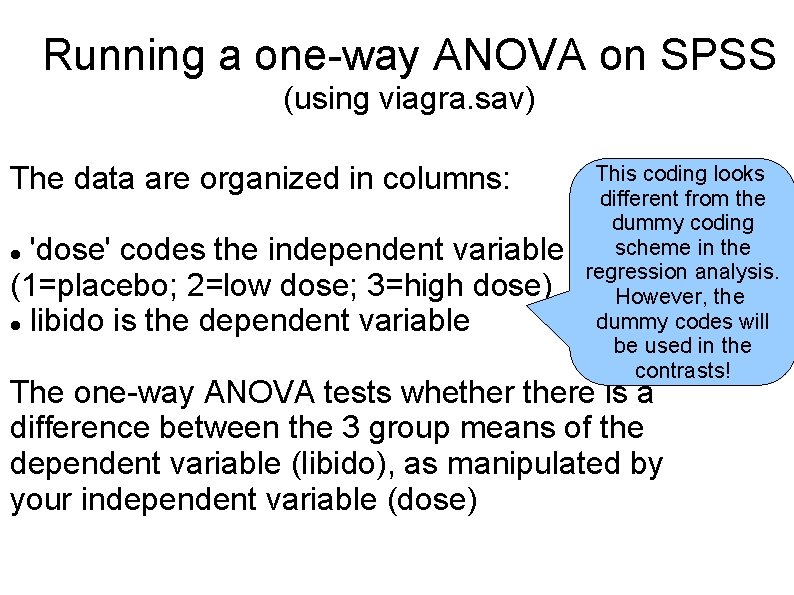

Running a one-way ANOVA on SPSS (using viagra. sav) The data are organized in columns: 'dose' codes the independent variable (1=placebo; 2=low dose; 3=high dose) libido is the dependent variable This coding looks different from the dummy coding scheme in the regression analysis. However, the dummy codes will be used in the contrasts! The one-way ANOVA tests whethere is a difference between the 3 group means of the dependent variable (libido), as manipulated by your independent variable (dose)

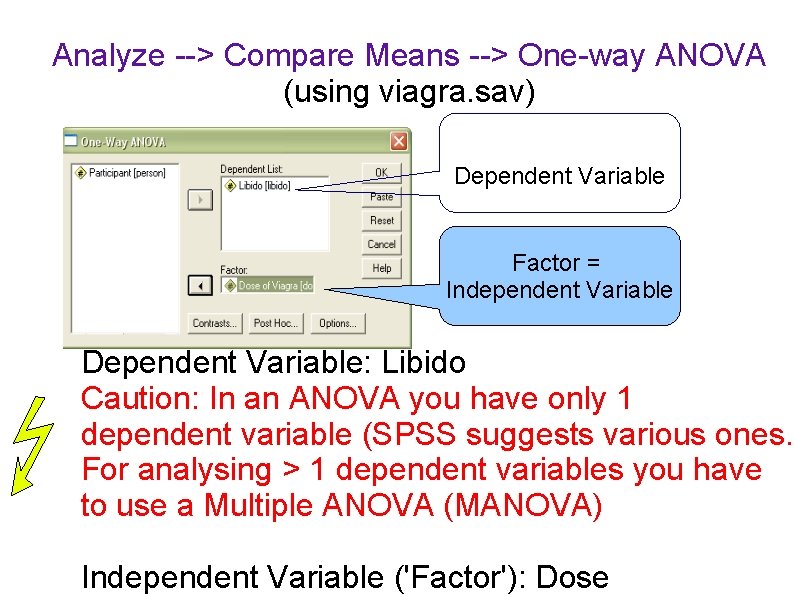

Analyze --> Compare Means --> One-way ANOVA (using viagra. sav) Dependent Variable Factor = Independent Variable Dependent Variable: Libido Caution: In an ANOVA you have only 1 dependent variable (SPSS suggests various ones. For analysing > 1 dependent variables you have to use a Multiple ANOVA (MANOVA) Independent Variable ('Factor'): Dose

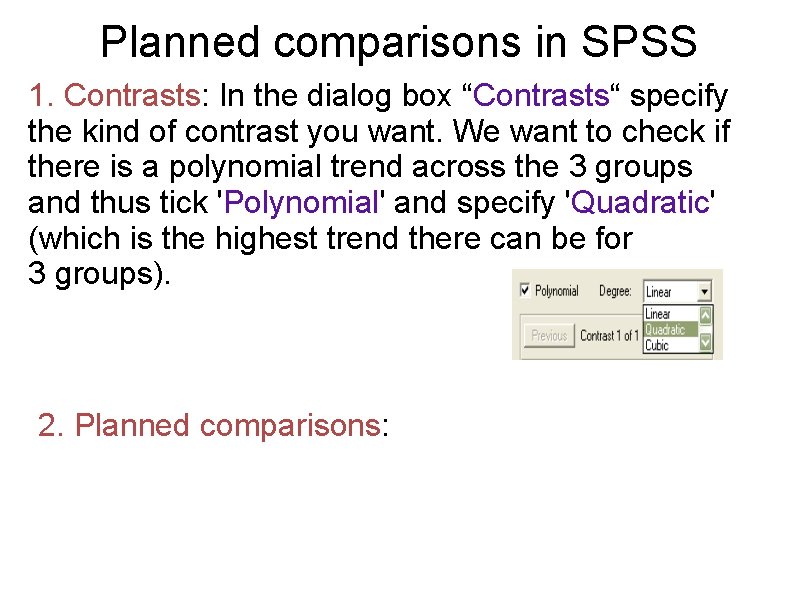

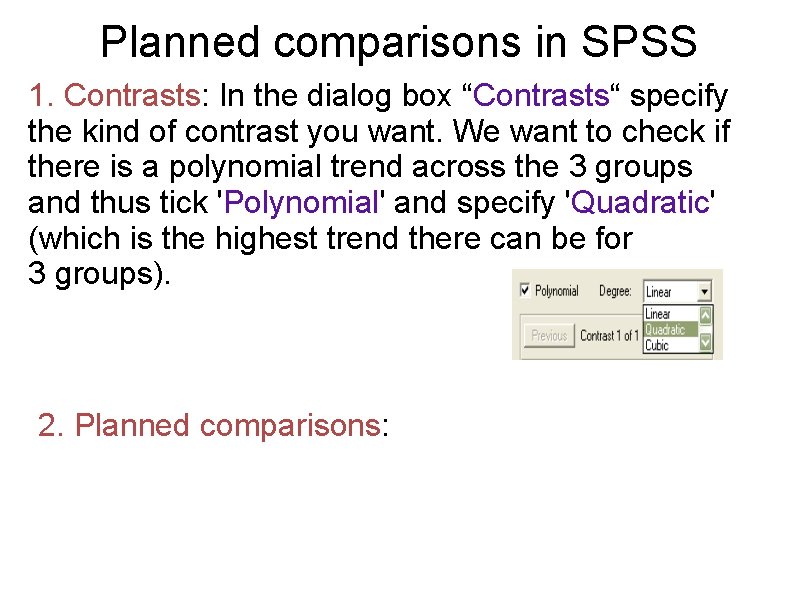

Planned comparisons in SPSS 1. Contrasts: In the dialog box “Contrasts“ specify the kind of contrast you want. We want to check if there is a polynomial trend across the 3 groups and thus tick 'Polynomial' and specify 'Quadratic' (which is the highest trend there can be for 3 groups). 2. Planned comparisons:

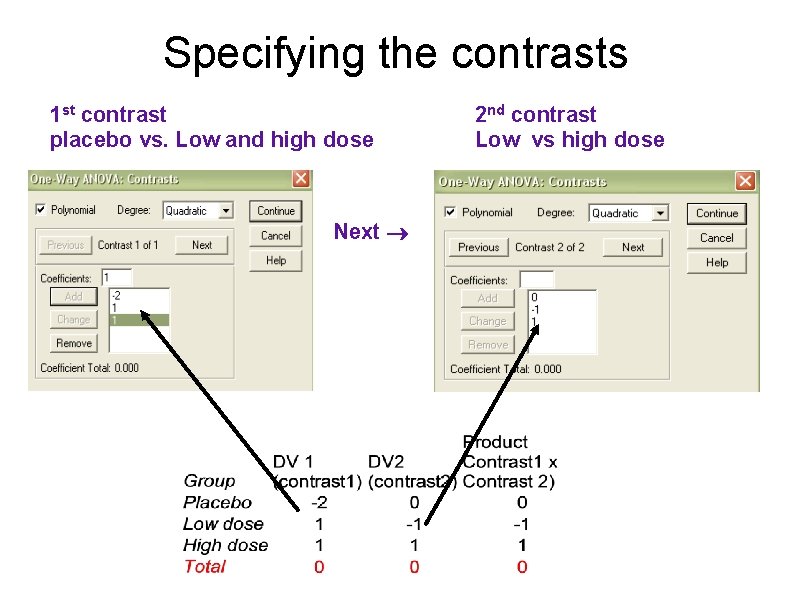

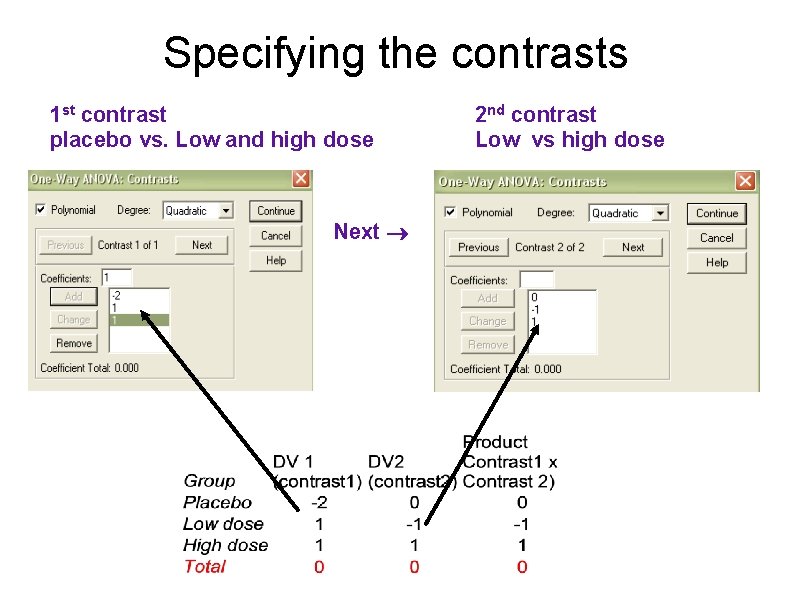

Specifying the contrasts 1 st contrast placebo vs. Low and high dose Next 2 nd contrast Low vs high dose

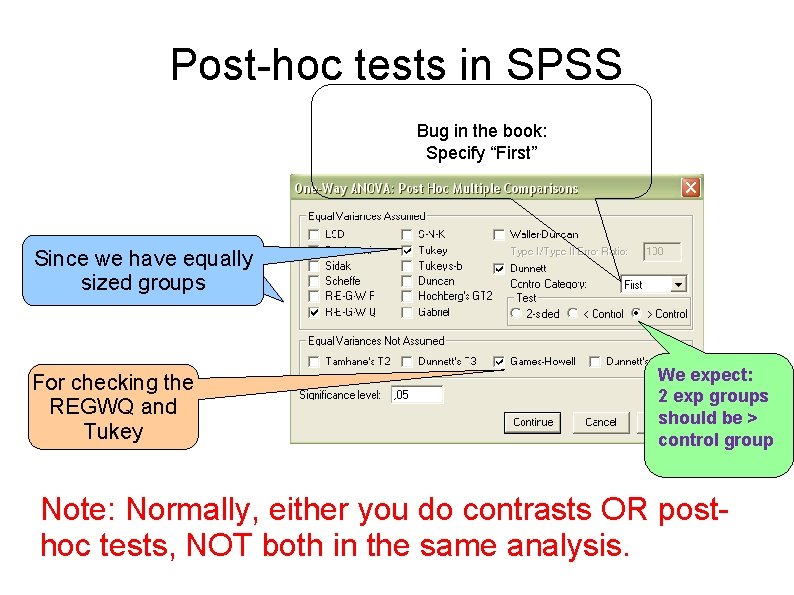

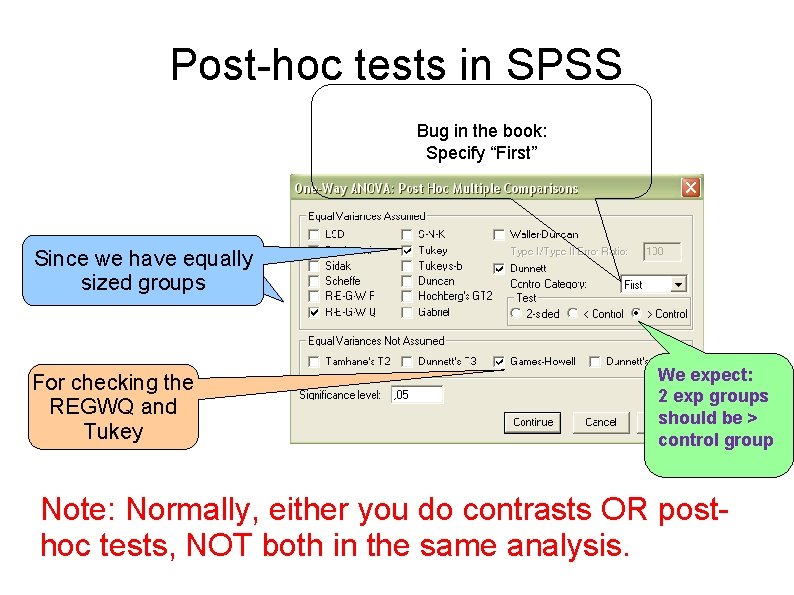

Post-hoc tests in SPSS Bug in the book: Specify “First” Since we have equally sized groups For checking the REGWQ and Tukey We expect: 2 exp groups should be > control group Note: Normally, either you do contrasts OR posthoc tests, NOT both in the same analysis.

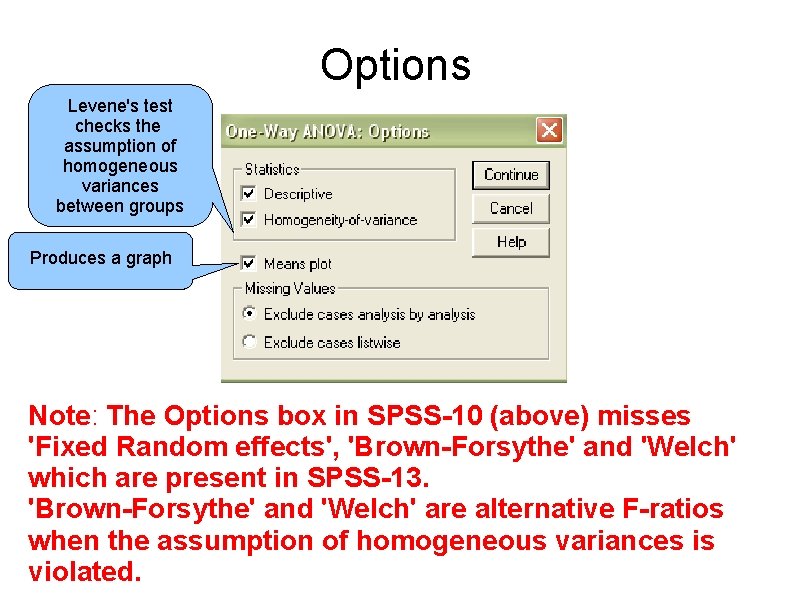

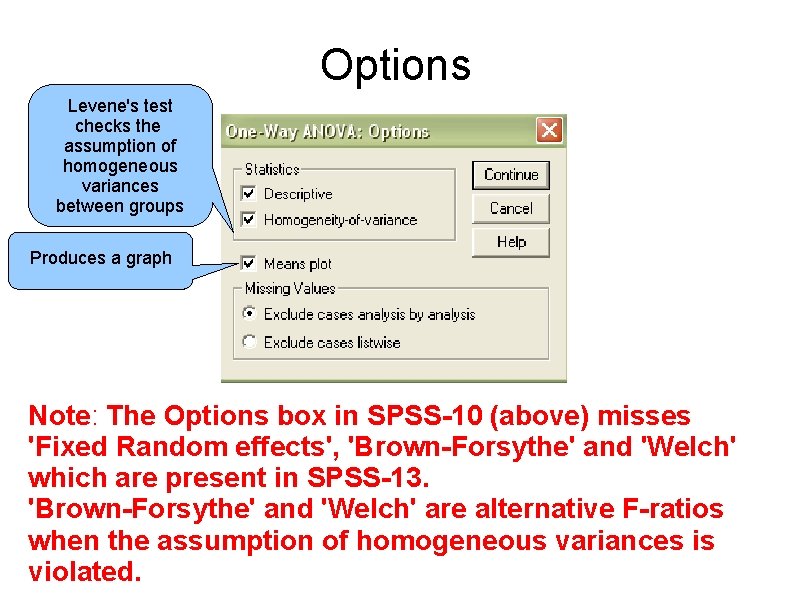

Options Levene's test checks the assumption of homogeneous variances between groups Produces a graph Note: The Options box in SPSS-10 (above) misses 'Fixed Random effects', 'Brown-Forsythe' and 'Welch' which are present in SPSS-13. 'Brown-Forsythe' and 'Welch' are alternative F-ratios when the assumption of homogeneous variances is violated.

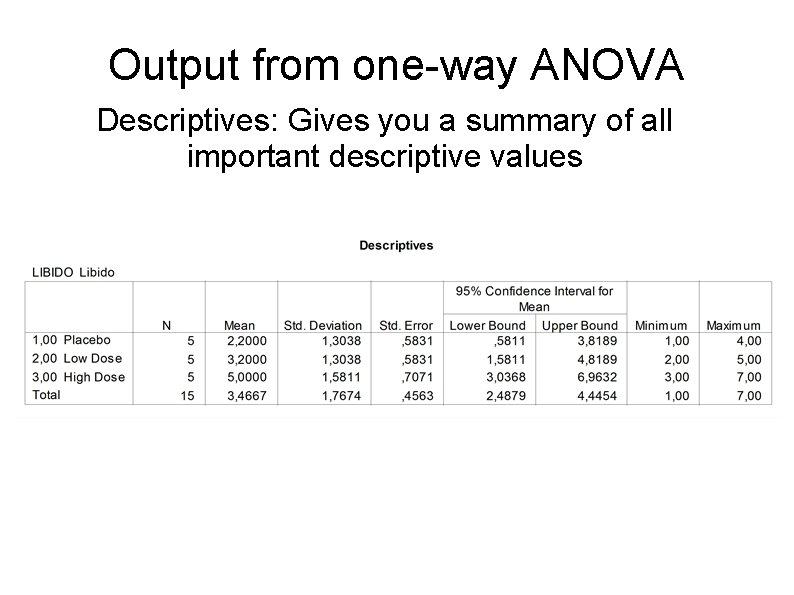

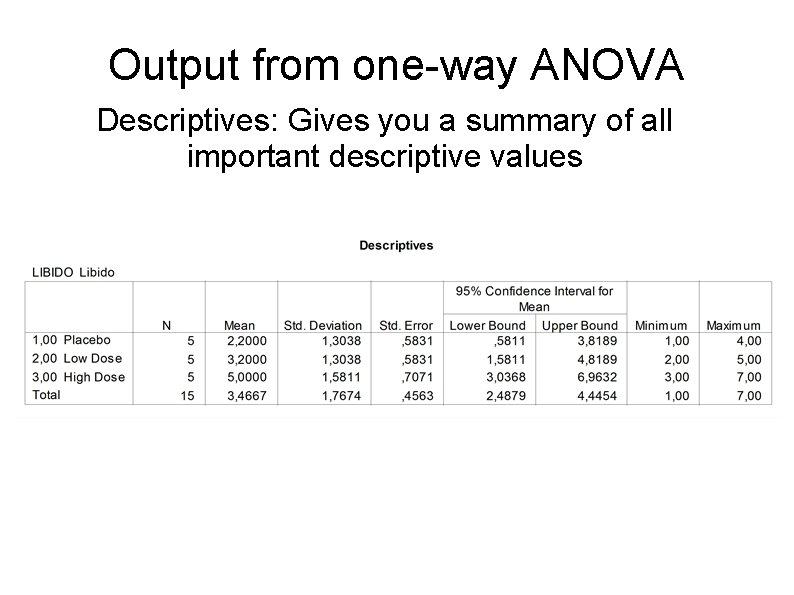

Output from one-way ANOVA Descriptives: Gives you a summary of all important descriptive values

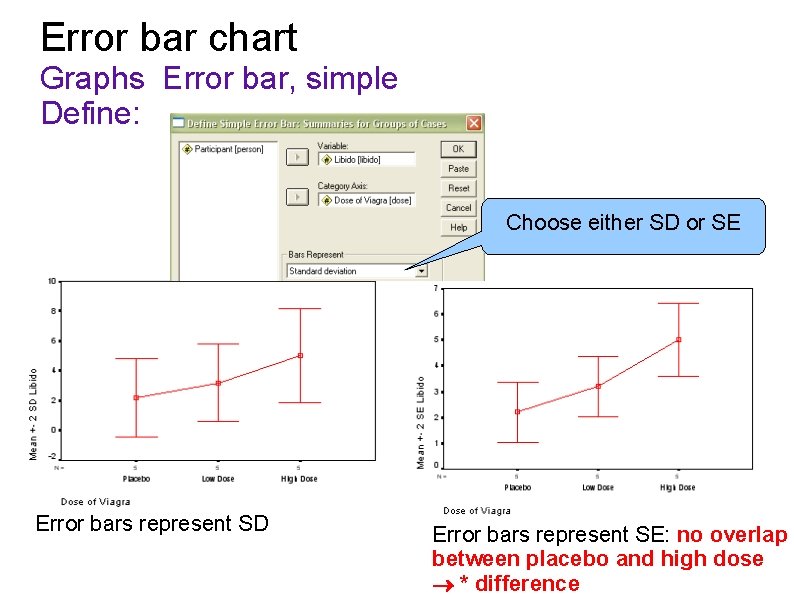

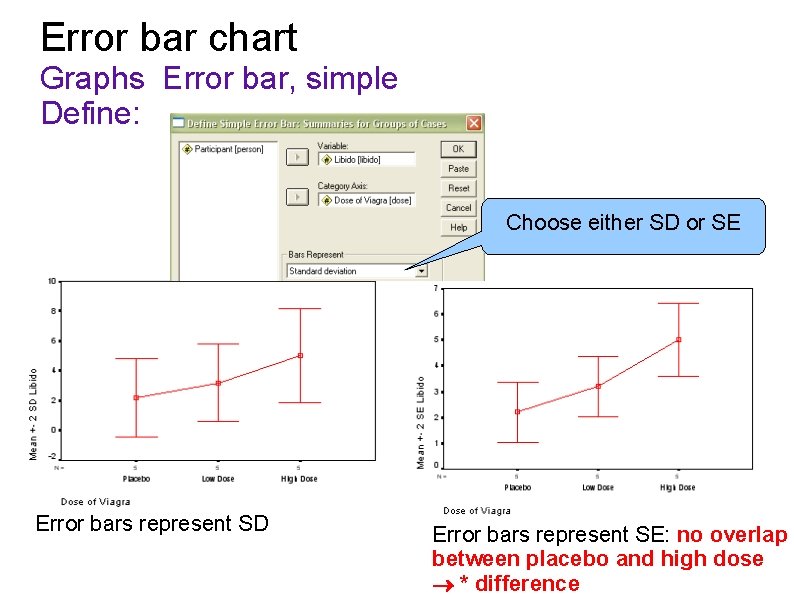

Error bar chart Graphs Error bar, simple Define: Choose either SD or SE Error bars represent SD Error bars represent SE: no overlap between placebo and high dose * difference

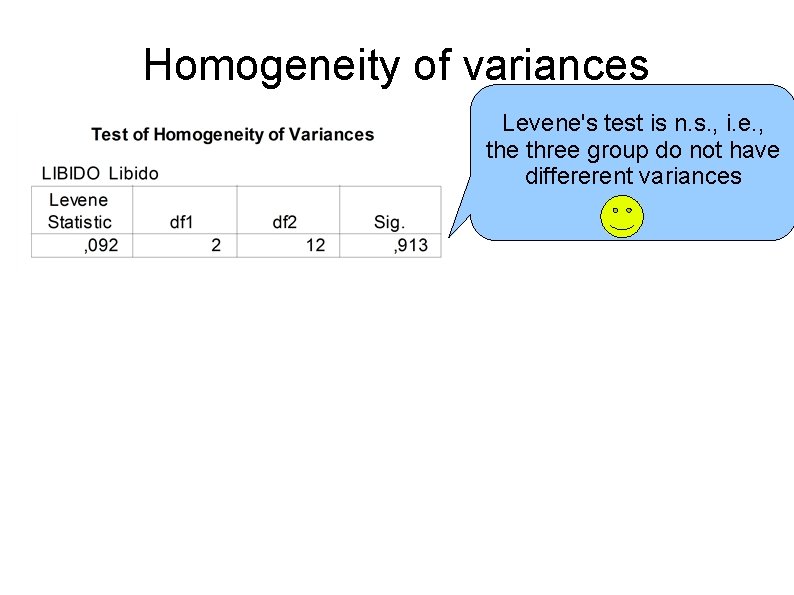

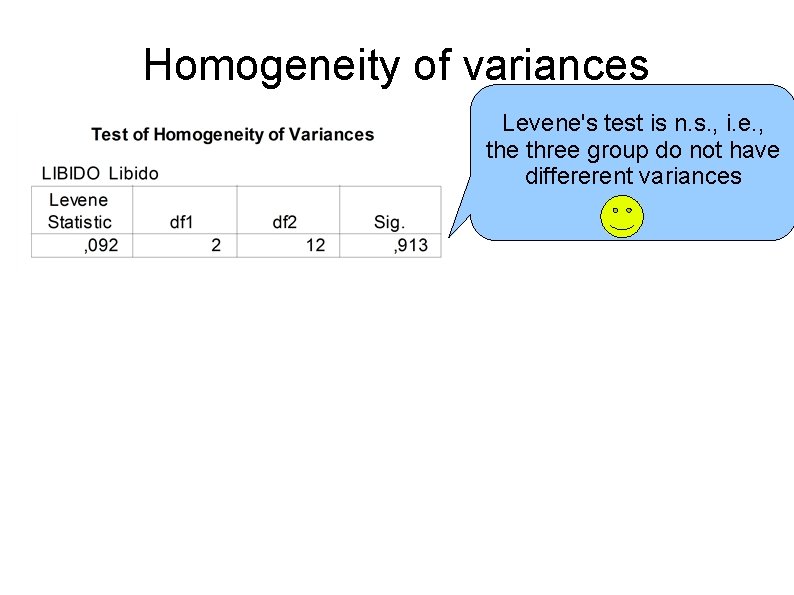

Homogeneity of variances Levene's test is n. s. , i. e. , the three group do not have differerent variances

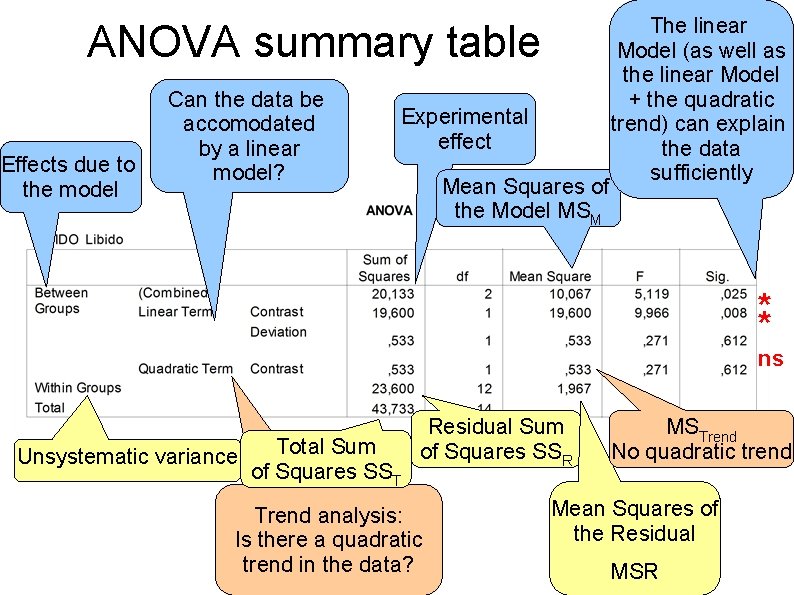

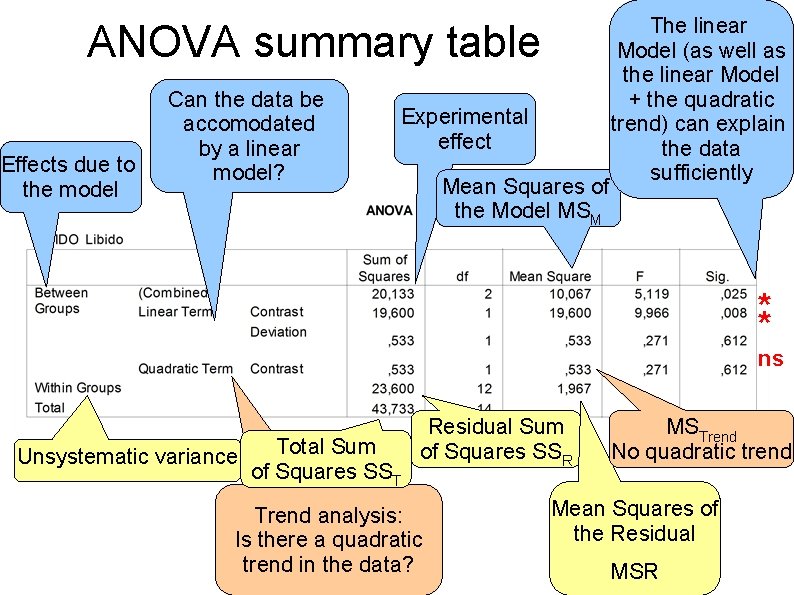

ANOVA summary table Effects due to the model Can the data be accomodated by a linear model? Experimental effect Mean Squares of the Model MSM The linear Model (as well as the linear Model + the quadratic trend) can explain the data sufficiently ** ns Unsystematic variance Total Sum of Squares SST Residual Sum of Squares SSR Trend analysis: Is there a quadratic trend in the data? MSTrend No quadratic trend Mean Squares of the Residual MSR

Result There is a significant effect of the experimental conditions (placebo, low, high dose) By looking at the error bars representing SD's, we would not have been able to tell. However, if we take error bars to represent SE's, there is no overlap between placebo and high dose. This corresponds to the significant overall effect.

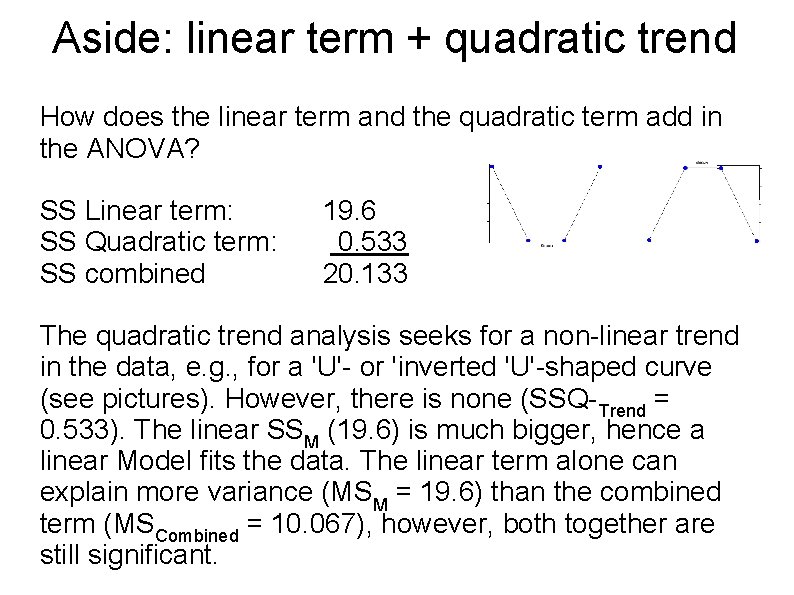

Aside: linear term + quadratic trend How does the linear term and the quadratic term add in the ANOVA? SS Linear term: SS Quadratic term: SS combined 19. 6 0. 533 20. 133 The quadratic trend analysis seeks for a non-linear trend in the data, e. g. , for a 'U'- or 'inverted 'U'-shaped curve (see pictures). However, there is none (SSQ-Trend = 0. 533). The linear SSM (19. 6) is much bigger, hence a linear Model fits the data. The linear term alone can explain more variance (MSM = 19. 6) than the combined term (MSCombined = 10. 067), however, both together are still significant.

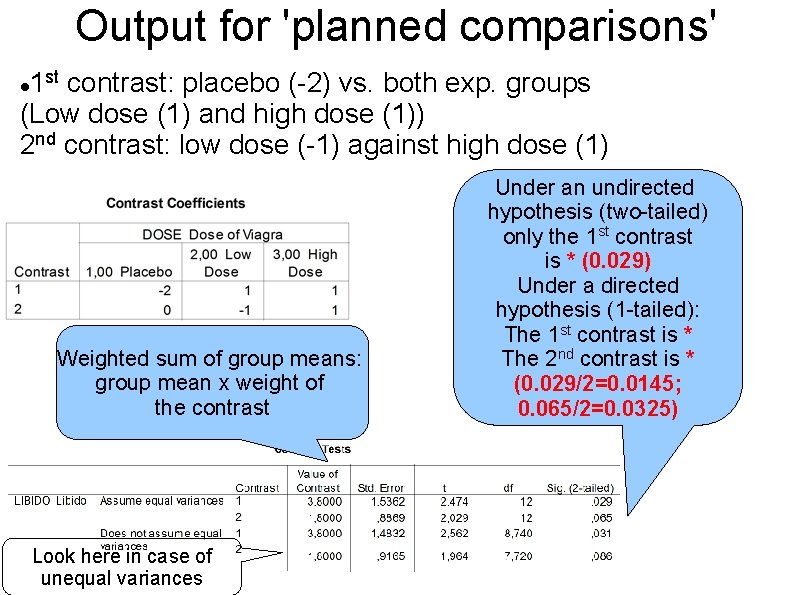

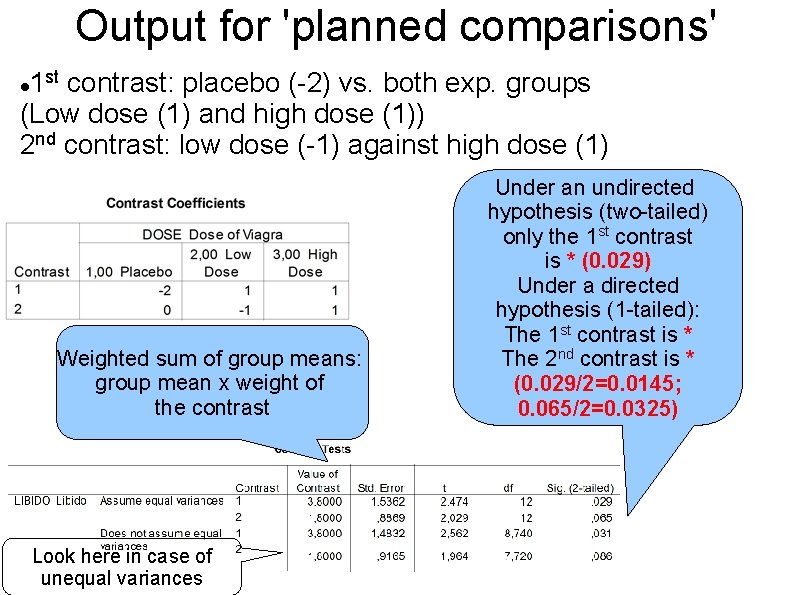

Output for 'planned comparisons' 1 st contrast: placebo (-2) vs. both exp. groups (Low dose (1) and high dose (1)) 2 nd contrast: low dose (-1) against high dose (1) Weighted sum of group means: group mean x weight of the contrast Look here in case of unequal variances Under an undirected hypothesis (two-tailed) only the 1 st contrast is * (0. 029) Under a directed hypothesis (1 -tailed): The 1 st contrast is * The 2 nd contrast is * (0. 029/2=0. 0145; 0. 065/2=0. 0325)

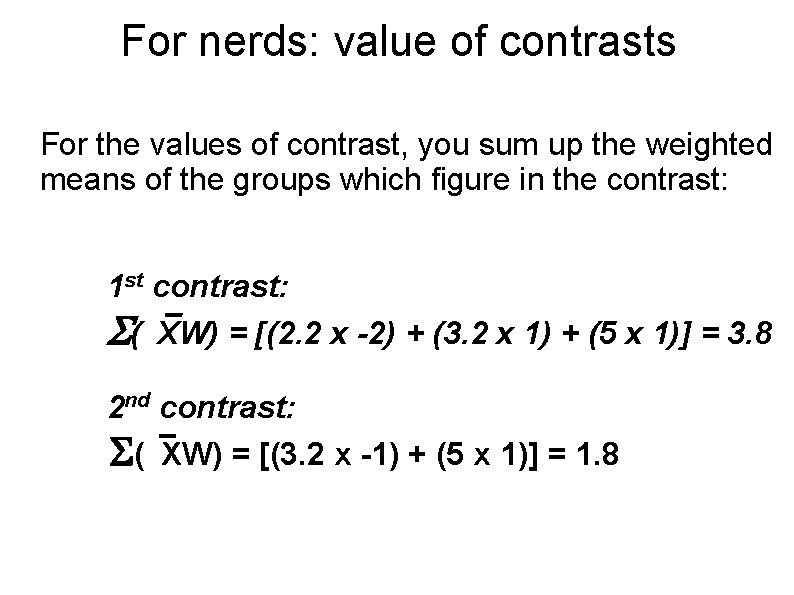

For nerds: value of contrasts For the values of contrast, you sum up the weighted means of the groups which figure in the contrast: 1 st contrast: ( XW) = [(2. 2 x -2) + (3. 2 x 1) + (5 x 1)] = 3. 8 2 nd contrast: ( XW) = [(3. 2 x -1) + (5 x 1)] = 1. 8

Summary ANOVA 1 st contrast: There is a general effect of the experimental treatment: taking viagra increases the libido 2 nd contrast: There is a special effect of the two experimental groups: Taking a high dose of viagra increases the libido more than taking a low dose

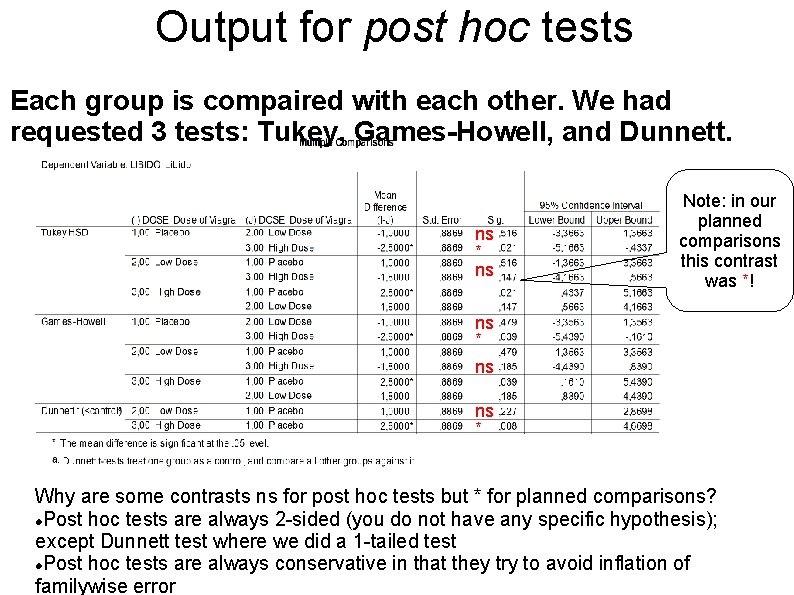

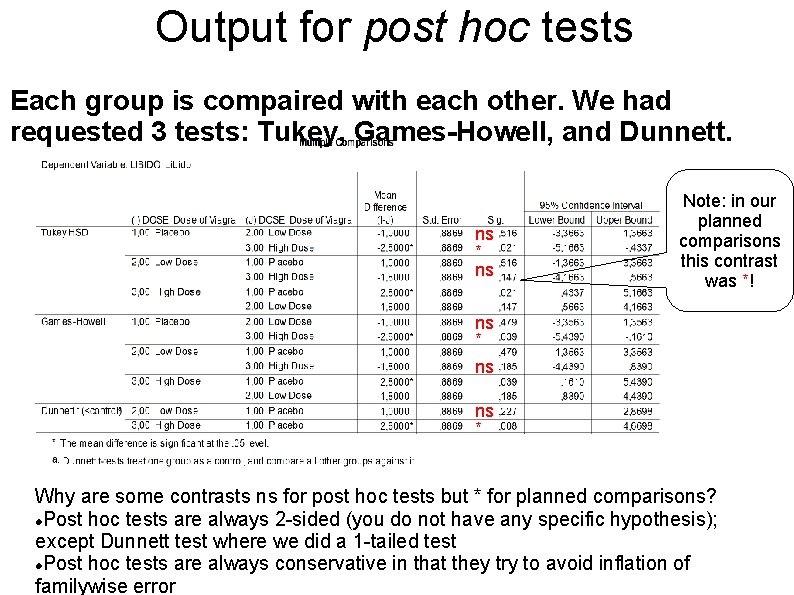

Output for post hoc tests Each group is compaired with each other. We had requested 3 tests: Tukey, Games-Howell, and Dunnett. ns * ns Note: in our planned comparisons this contrast was *! ns * ns ns * Why are some contrasts ns for post hoc tests but * for planned comparisons? Post hoc tests are always 2 -sided (you do not have any specific hypothesis); except Dunnett test where we did a 1 -tailed test Post hoc tests are always conservative in that they try to avoid inflation of familywise error

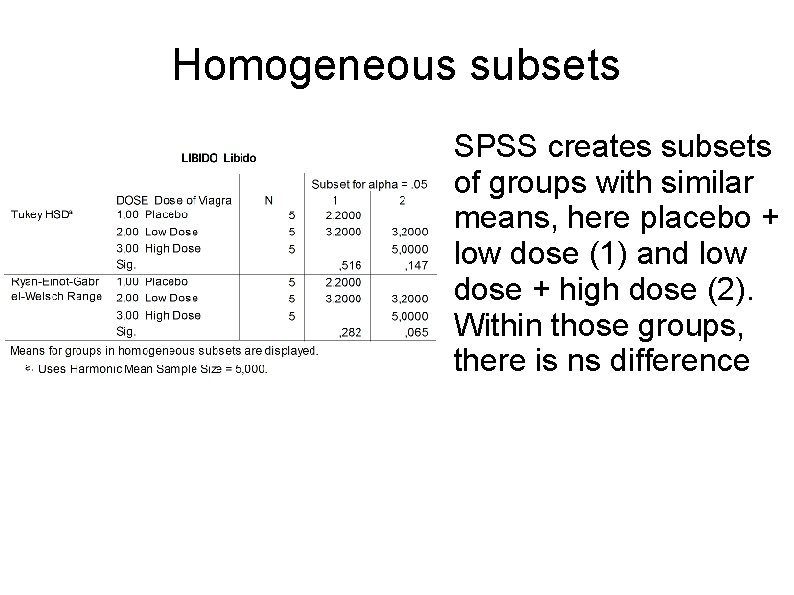

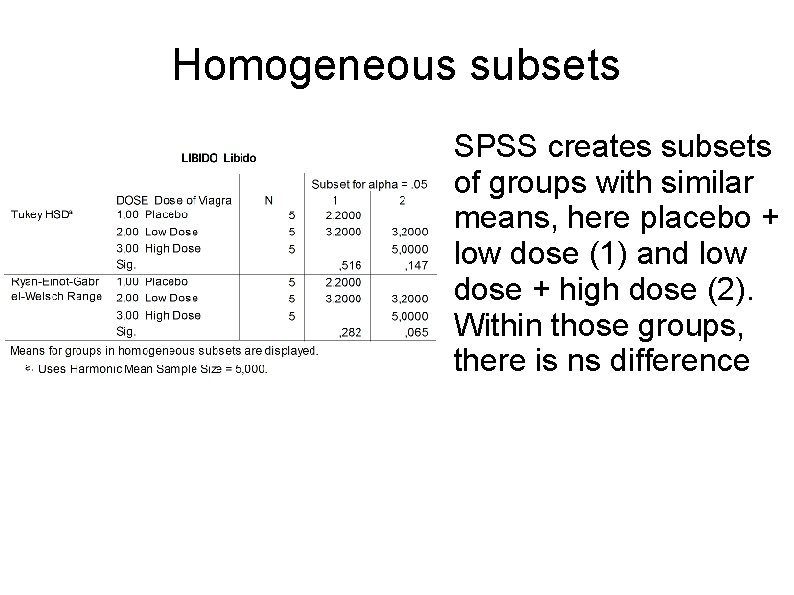

Homogeneous subsets SPSS creates subsets of groups with similar means, here placebo + low dose (1) and low dose + high dose (2). Within those groups, there is ns difference

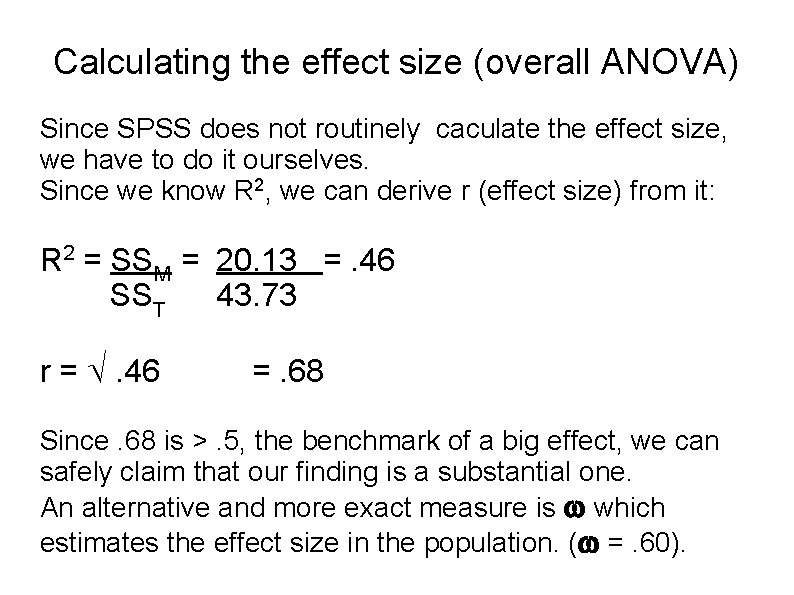

Calculating the effect size (overall ANOVA) Since SPSS does not routinely caculate the effect size, we have to do it ourselves. Since we know R 2, we can derive r (effect size) from it: R 2 = SSM = 20. 13 =. 46 SST 43. 73 r = . 46 =. 68 Since. 68 is >. 5, the benchmark of a big effect, we can safely claim that our finding is a substantial one. An alternative and more exact measure is which estimates the effect size in the population. ( =. 60).

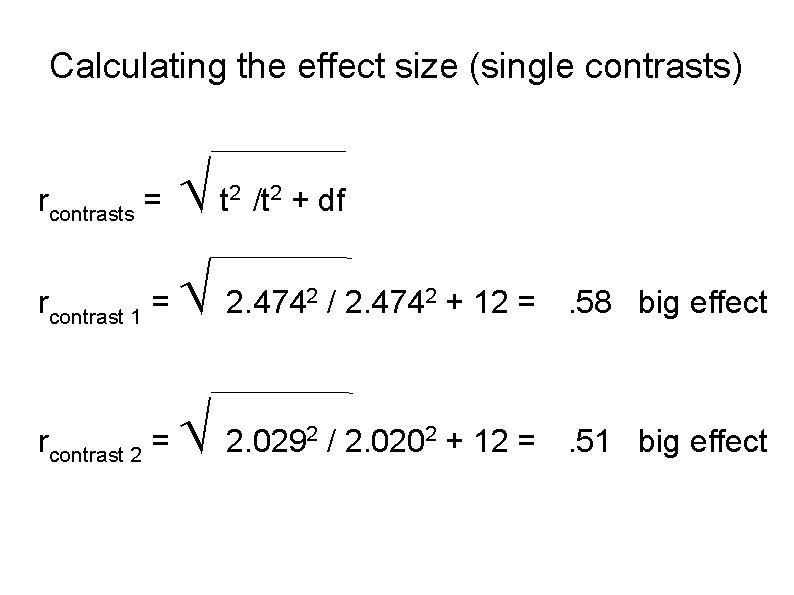

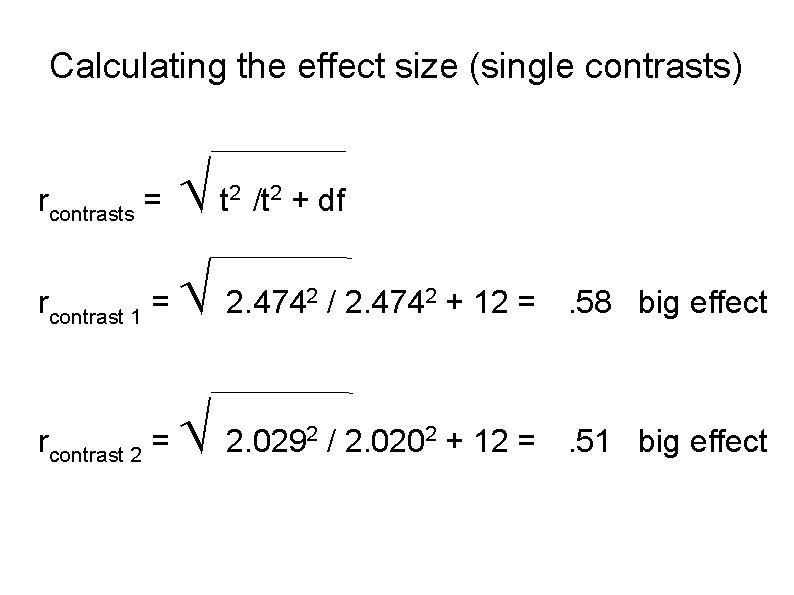

Calculating the effect size (single contrasts) rcontrasts = t rcontrast 1 = 2. 474 2 / 2. 4742 + 12 =. 58 big effect rcontrast 2 = 2. 029 2 / 2. 0202 + 12 =. 51 big effect 2 /t 2 + df

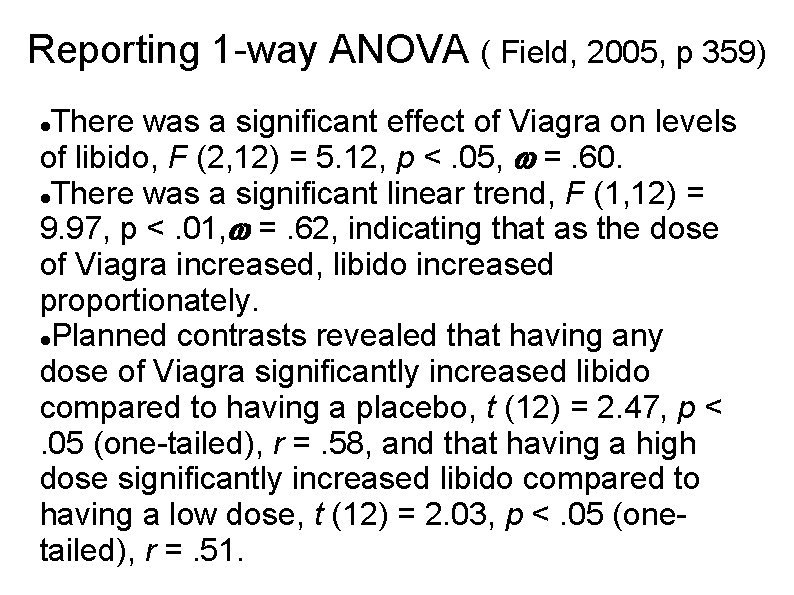

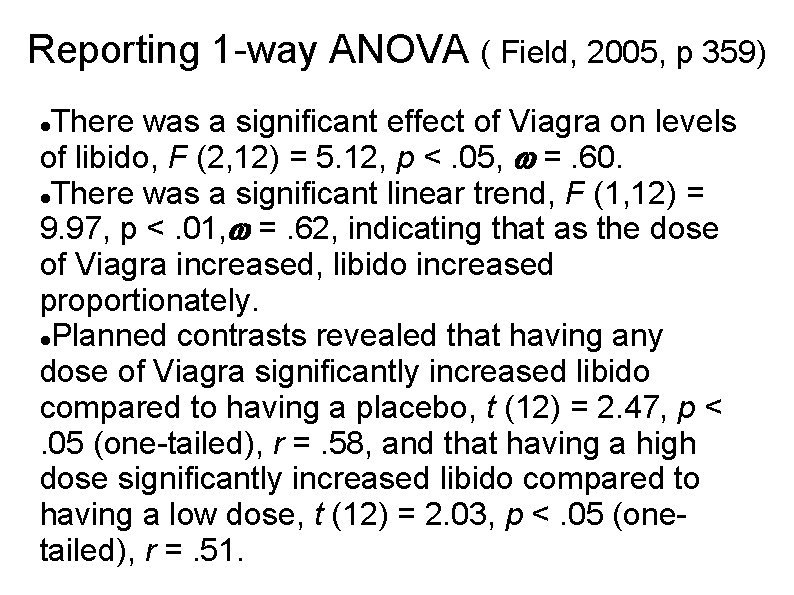

Reporting 1 -way ANOVA ( Field, 2005, p 359) There was a significant effect of Viagra on levels of libido, F (2, 12) = 5. 12, p <. 05, =. 60. There was a significant linear trend, F (1, 12) = 9. 97, p <. 01, =. 62, indicating that as the dose of Viagra increased, libido increased proportionately. Planned contrasts revealed that having any dose of Viagra significantly increased libido compared to having a placebo, t (12) = 2. 47, p <. 05 (one-tailed), r =. 58, and that having a high dose significantly increased libido compared to having a low dose, t (12) = 2. 03, p <. 05 (onetailed), r =. 51.