Chapter 8 Precambrian Earth and Life HistoryThe Archean

Chapter 8 Precambrian Earth and Life History—The Archean Eon

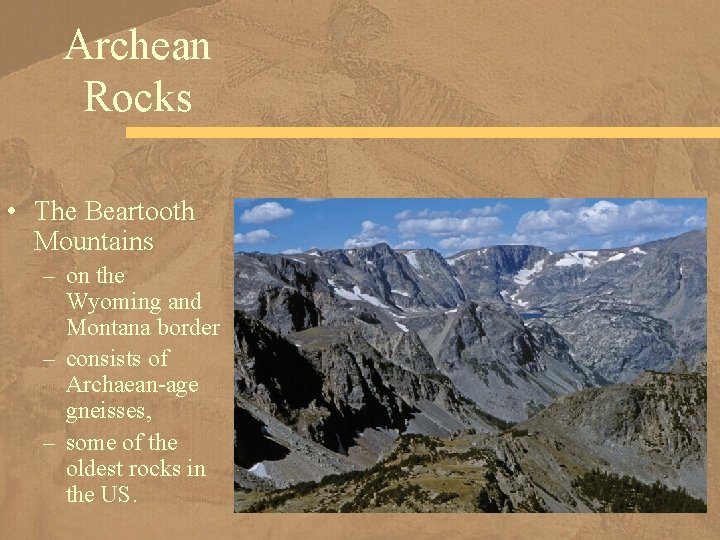

Archean Rocks • The Beartooth Mountains – on the Wyoming and Montana border – consists of Archaean-age gneisses, – some of the oldest rocks in the US.

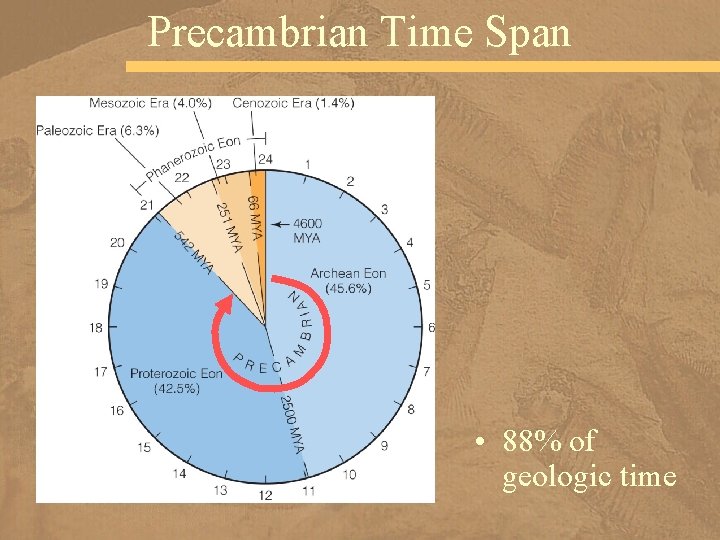

Precambrian • The Precambrian lasted for more than 4 billion years! – This large time span is difficult for humans to comprehend • Suppose that a 24 -hour clock represented – all 4. 6 billion years of geologic time – then the Precambrian would be – slightly more than 21 hours long, – constituting about 88% of all geologic time

Precambrian Time Span • 88% of geologic time

Precambrian • The term Precambrian is informal – but widely used, referring to both time and rocks • The Precambrian includes – time from Earth’s origin 4. 6 billion years ago – to the beginning of the Phanerozoic Eon – 542 million years ago • It encompasses – all rocks below the Cambrian system • No rocks are known for the first – 600 million years of geologic time – The oldest known rocks on Earth – are 4. 0 billion years old

Rocks Difficult to Interpret • The earliest record of geologic time – preserved in rocks is difficult to interpret – because many Precambrian rocks have been • • • altered by metamorphism complexly deformed buried deep beneath younger rocks fossils are rare, and the few fossils present are not of any use in biostratigraphy • Subdivisions of the Precambrian – have been difficult to establish • Two eons for the Precambrian – are the Archean and Proterozoic – which are based on absolute ages

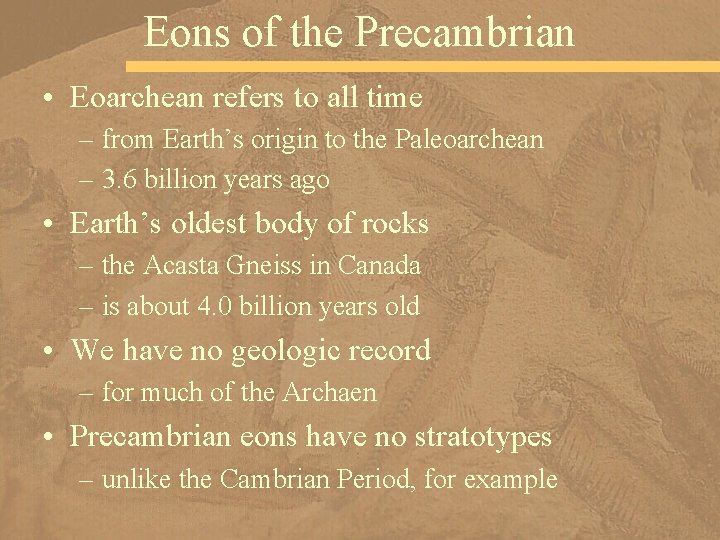

Eons of the Precambrian • Eoarchean refers to all time – from Earth’s origin to the Paleoarchean – 3. 6 billion years ago • Earth’s oldest body of rocks – the Acasta Gneiss in Canada – is about 4. 0 billion years old • We have no geologic record – for much of the Archaen • Precambrian eons have no stratotypes – unlike the Cambrian Period, for example

What Happened During the Eoarchean? • Although no rocks of Eoarchean age are present on Earth, – except for meteorites, • we do know some events that took place then – Earth accreted from planetesimals – and differentiated into a core and mantle • and at least some crust was present – Earth was bombarded by meteorites – Volcanic activity was ubiquitous – An atmosphere formed, quite different from today’s – Oceans began to accumulate

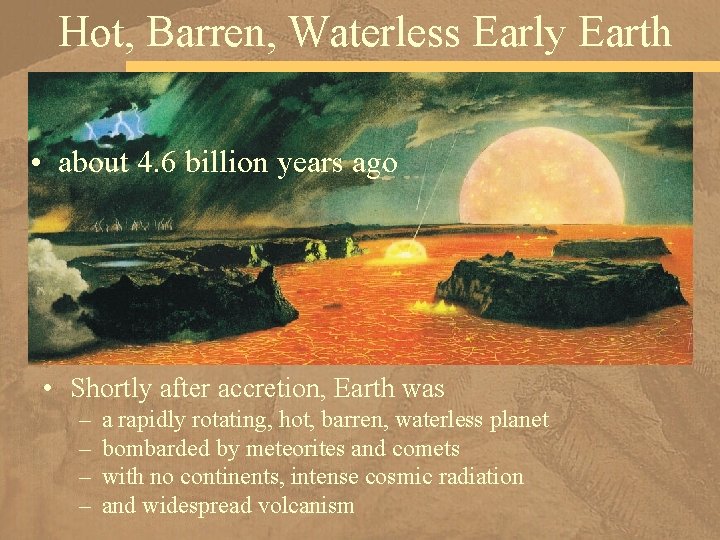

Hot, Barren, Waterless Early Earth • about 4. 6 billion years ago • Shortly after accretion, Earth was – – a rapidly rotating, hot, barren, waterless planet bombarded by meteorites and comets with no continents, intense cosmic radiation and widespread volcanism

Oldest Rocks • Continental crust was present by 4. 0 billion years ago – Sedimentary rocks in Australia contain detrital zircons (Zr. Si. O 4) dated at 4. 4 billion years old – so source rocks at least that old existed • The Eoarchean Earth probably rotated in as little as 10 hours – and the Earth was closer to the Moon • By 4. 4 billion years ago, the Earth cooled sufficiently for surface waters to accumulate

Eoarchean Crust • Early crust formed as upwelling mantle currents – of mafic magma, – and numerous subduction zones developed – to form the first island arcs • Eoarchean continental crust may have formed – by collisions between island arcs – as silica-rich materials were metamorphosed. – Larger groups of merged island arcs • protocontinents – grew faster by accretion along their margins

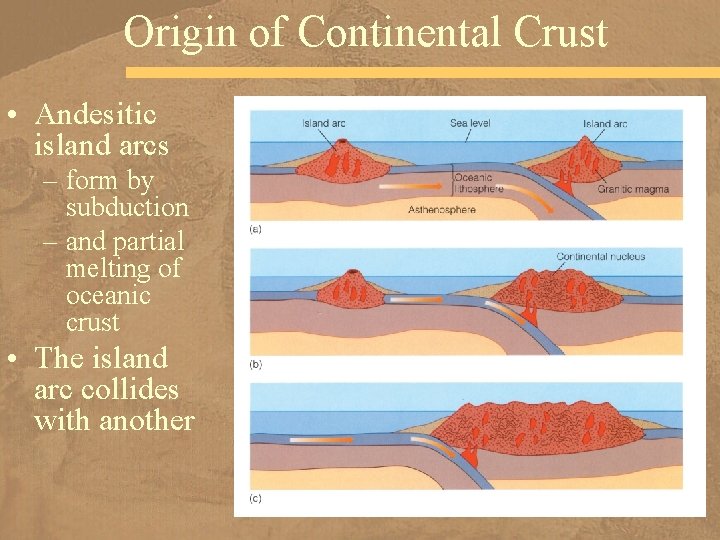

Origin of Continental Crust • Andesitic island arcs – form by subduction – and partial melting of oceanic crust • The island arc collides with another

Continental Foundations • Continents consist of rocks – with composition similar to that of granite • Continental crust is thicker – and less dense than oceanic crust – which is made up of basalt and gabbro • Precambrian shields – consist of vast areas of exposed ancient rocks – and are found on all continents • Outward from the shields are broad platforms – of buried Precambrian rocks – that underlie much of each continent

Cratons • A shield and its platform make up a craton, – a continent’s ancient nucleus • Along the margins of cratons, – more continental crust was added – as the continents took their present sizes and shapes • Both Archean and Proterozoic rocks – are present in cratons and show evidence of – episodes of deformation accompanied by – igneous activity, metamorphism, – and mountain building • Cratons have experienced little deformation – since the Precambrian

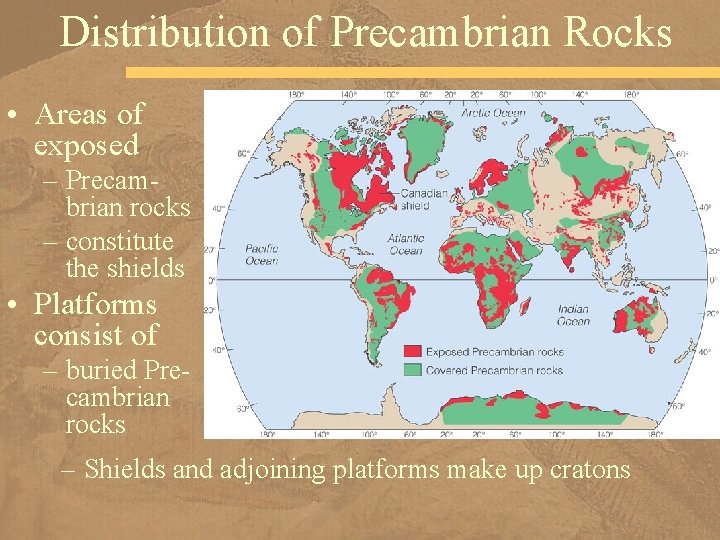

Distribution of Precambrian Rocks • Areas of exposed – Precambrian rocks – constitute the shields • Platforms consist of – buried Precambrian rocks – Shields and adjoining platforms make up cratons

Canadian Shield • The exposed part of the craton in North America is the Canadian shield – which occupies most of northeastern Canada – a large part of Greenland – parts of the Lake Superior region • in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan – and the Adirondack Mountains of New York • Its topography is subdued, – with numerous lakes and exposed Archean – and Proterozoic rocks thinly covered – in places by Pleistocene glacial deposits

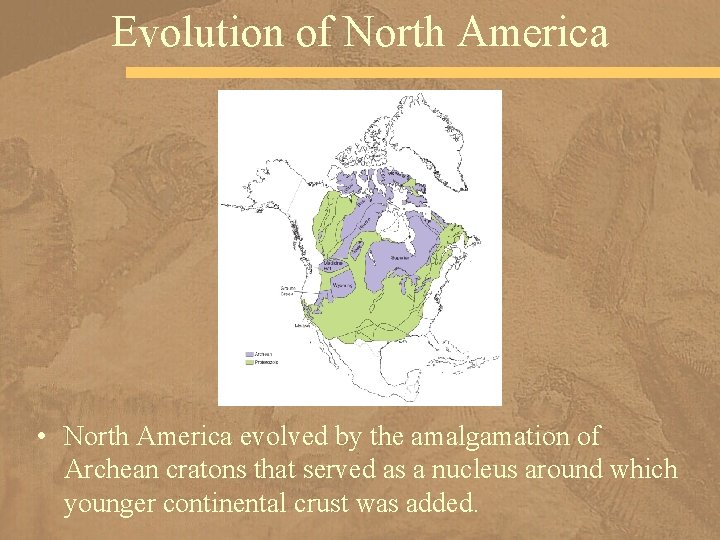

Evolution of North America • North America evolved by the amalgamation of Archean cratons that served as a nucleus around which younger continental crust was added.

North American Craton • Drilling and geophysical evidence indicate – that Precambrian rocks underlie much – of North America, – exposed only in places by deep erosion or uplift

Archean Rocks • Only 22% of Earth’s exposed Precambrian crust is Archean • The most common Archean rock associations – are granite-gneiss complexes • Other rocks range from peridotite – to various sedimentary rocks – all of which have been metamorphosed • Greenstone belts are subordinate in quantity, – account for only 10% of Archean rocks – but are important in unraveling Archean tectonic events

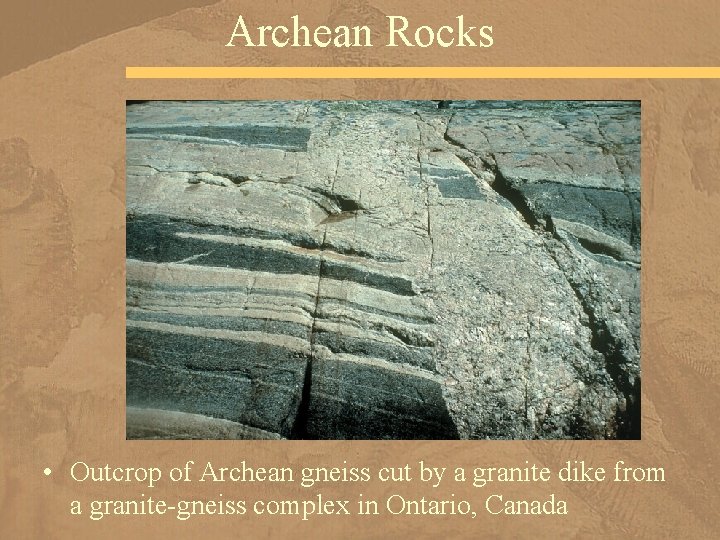

Archean Rocks • Outcrop of Archean gneiss cut by a granite dike from a granite-gneiss complex in Ontario, Canada

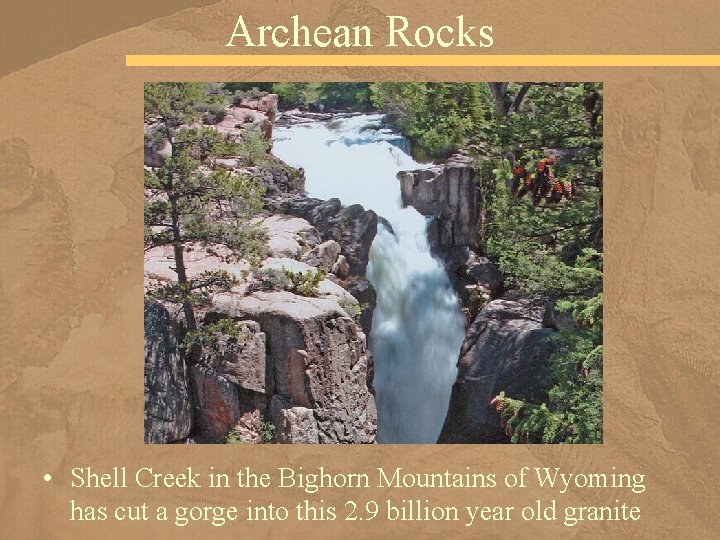

Archean Rocks • Shell Creek in the Bighorn Mountains of Wyoming has cut a gorge into this 2. 9 billion year old granite

Greenstone Belts • A greenstone belt has 3 major rock units – volcanic rocks are most common – in the lower and middle units – the upper units are mostly sedimentary • The belts typically have synclinal structure – Most were intruded by granitic magma – and cut by thrust faults • Low-grade metamorphism – makes many of the igneous rocks green – Because they contain chlorite, actinolite, and epidote

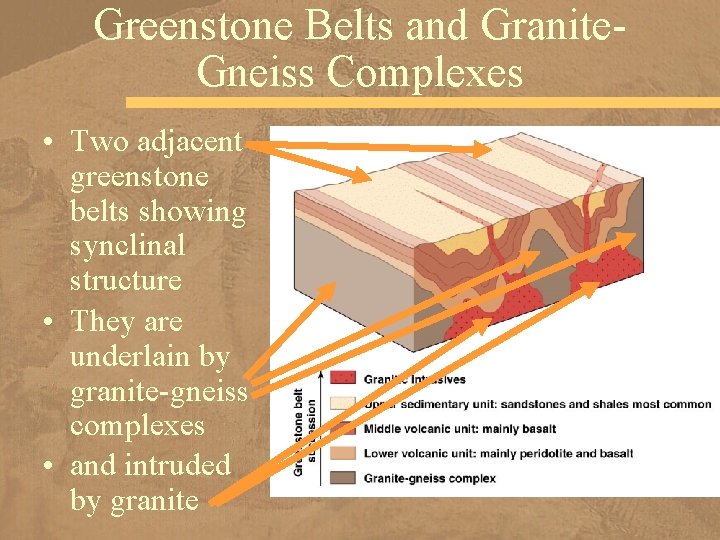

Greenstone Belts and Granite. Gneiss Complexes • Two adjacent greenstone belts showing synclinal structure • They are underlain by granite-gneiss complexes • and intruded by granite

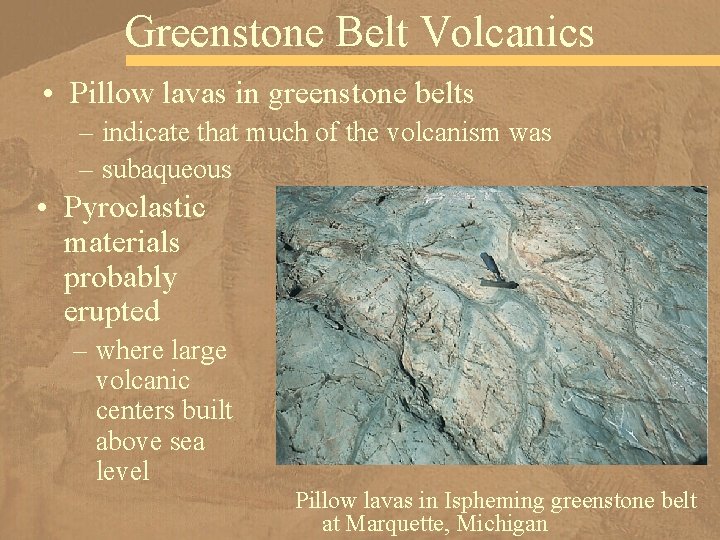

Greenstone Belt Volcanics • Pillow lavas in greenstone belts – indicate that much of the volcanism was – subaqueous • Pyroclastic materials probably erupted – where large volcanic centers built above sea level Pillow lavas in Ispheming greenstone belt at Marquette, Michigan

Ultramafic Lava Flows • The most interesting rocks – in greenstone belts are komatiites, – cooled from ultramafic lava flows • Ultramafic magma (< 45% silica) – requires near surface magma temperatures – of more than 1600°C – 250°C hotter than any recent flows • During Earth’s early history, – radiogenic heating was greater – and the mantle was as much as 300 °C hotter – than it is now • This allowed ultramafic magma – to reach the surface

Ultramafic Lava Flows • As Earth’s production – of radiogenic heat decreased, – the mantle cooled – and ultramafic flows no longer occurred • They are rare in rocks younger – than Archean and none occur now

Sedimentary Rocks of Greenstone Belts • Sedimentary rocks are found – throughout the greenstone belts – although they predominate – in the upper unit • Many of these rocks are successions of – graywacke • sandstone with abundant clay and rock fragments – and argillite • slightly metamorphosed mudrock

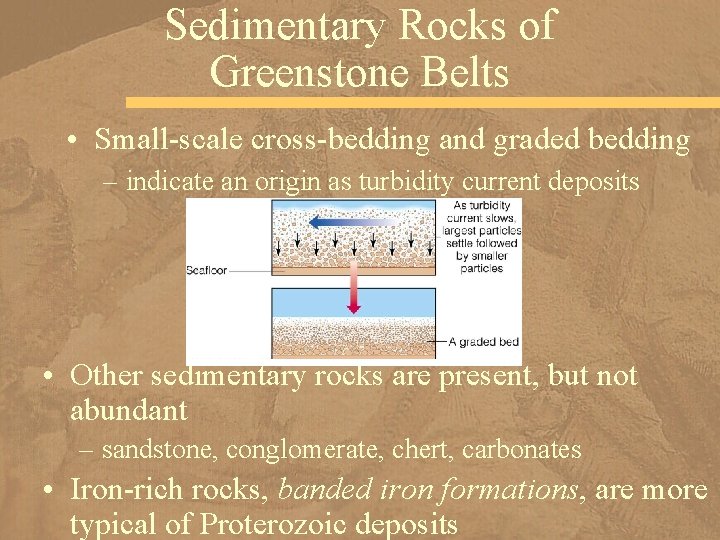

Sedimentary Rocks of Greenstone Belts • Small-scale cross-bedding and graded bedding – indicate an origin as turbidity current deposits • Other sedimentary rocks are present, but not abundant – sandstone, conglomerate, chert, carbonates • Iron-rich rocks, banded iron formations, are more typical of Proterozoic deposits

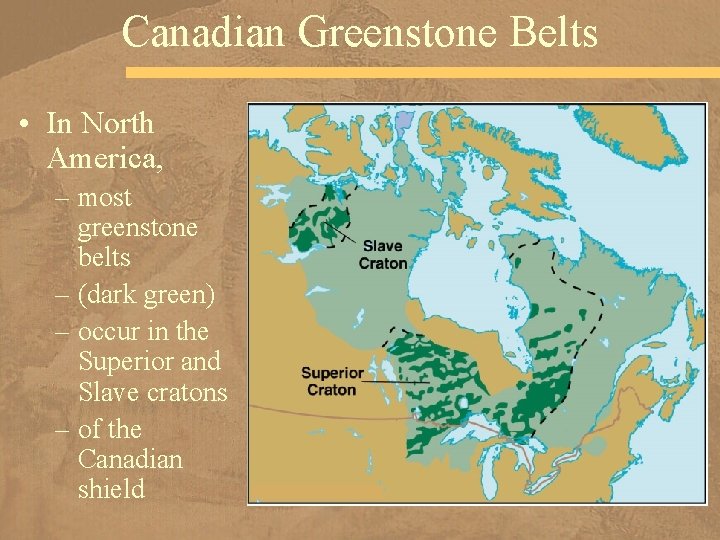

Canadian Greenstone Belts • In North America, – most greenstone belts – (dark green) – occur in the Superior and Slave cratons – of the Canadian shield

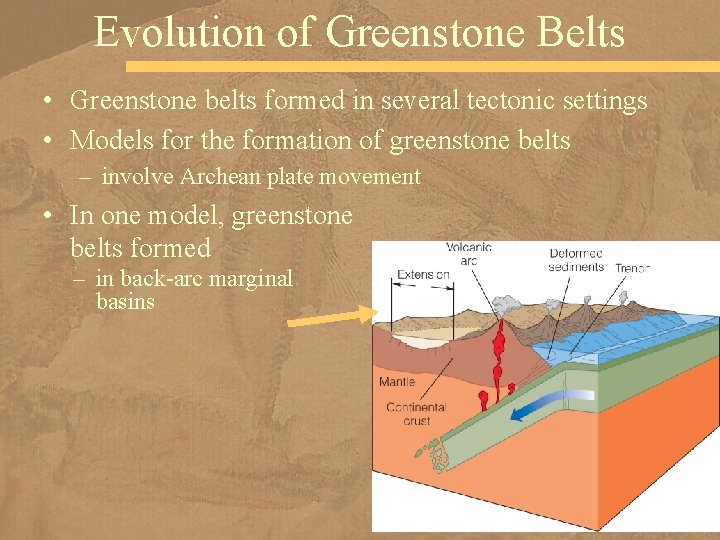

Evolution of Greenstone Belts • Greenstone belts formed in several tectonic settings • Models for the formation of greenstone belts – involve Archean plate movement • In one model, greenstone belts formed – in back-arc marginal basins

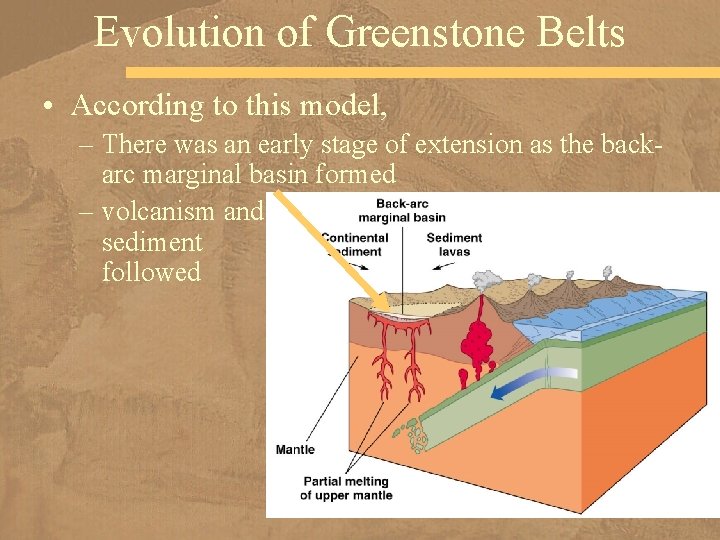

Evolution of Greenstone Belts • According to this model, – There was an early stage of extension as the backarc marginal basin formed – volcanism and sediment deposition followed

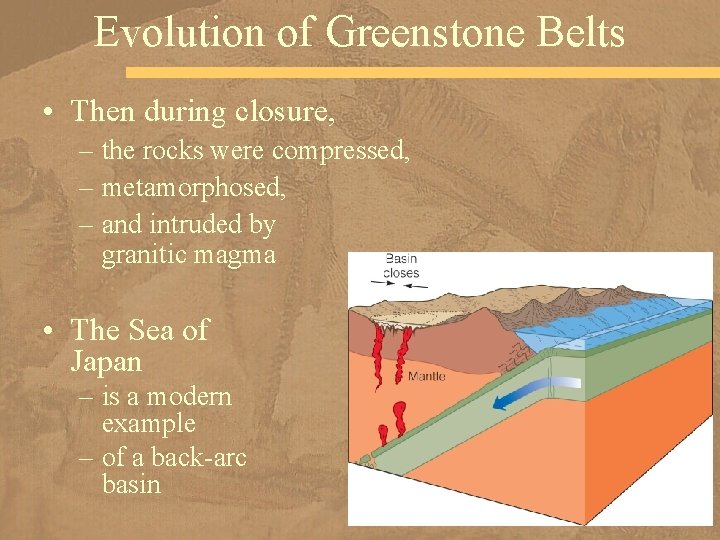

Evolution of Greenstone Belts • Then during closure, – the rocks were compressed, – metamorphosed, – and intruded by granitic magma • The Sea of Japan – is a modern example – of a back-arc basin

Another Model • In another model accepted by some geologists, – greenstone belts formed – over rising mantle plumes in intracontinental rifts • As the plume rises beneath sialic crust – it spreads and generates tensional forces – The mantle plume is the source – of the volcanic rocks in the lower and middle units – of the greenstone belt – and erosion of volcanic rocks and flanks for the rift – supply the sediment to the upper unit • An episode of subsidence, deformation, – metamorphism and plutonism followed

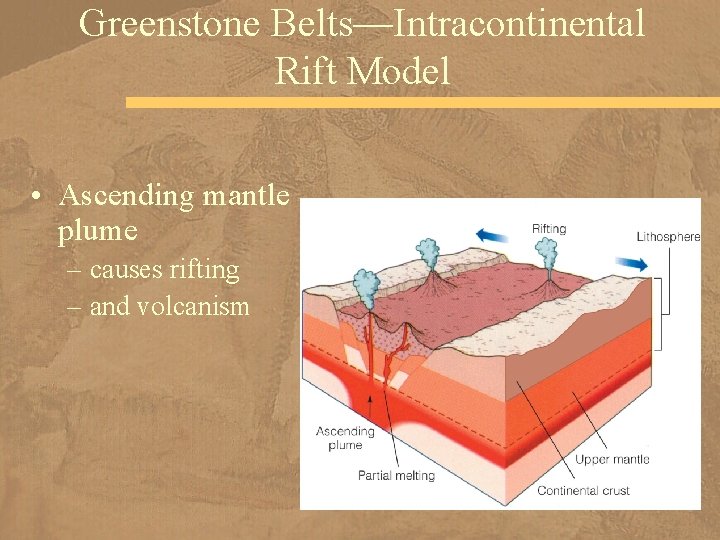

Greenstone Belts—Intracontinental Rift Model • Ascending mantle plume – causes rifting – and volcanism

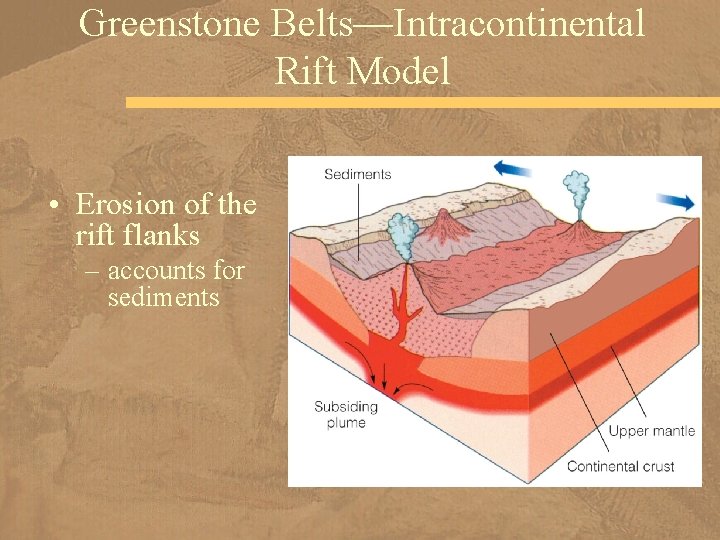

Greenstone Belts—Intracontinental Rift Model • Erosion of the rift flanks – accounts for sediments

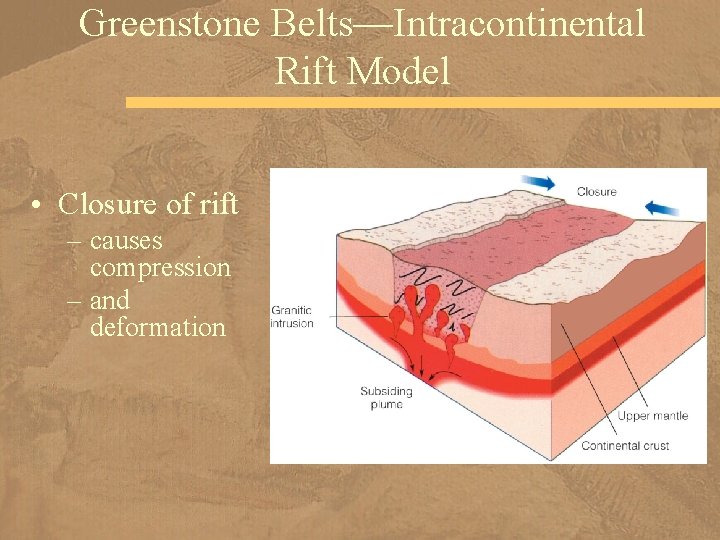

Greenstone Belts—Intracontinental Rift Model • Closure of rift – causes compression – and deformation

Archean Plate Tectonics • Plate tectonic activity has operated – since the Paleoproterozoic or earlier • Most geologists are convinced – that some kind of plate tectonic activity – took place during the Archean as well – but it differed in detail from today • Plates must have moved faster – with more residual heat from Earth’s origin – and more radiogenic heat, – and magma was generated more rapidly

Archean Plate Tectonics • As a result of the rapid movement of plates, – continents grew more rapidly along their margins – a process called continental accretion – as plates collided with island arcs and other plates • Also, ultramafic extrusive igneous rocks, – komatiites, – were more common

Archean World Differences • The Archean world was markedly different than later – We have little evidence of Archean rocks – deposited on broad, passive continental margins – Deformation belts between colliding cratons – indicate that Archean plate tectonics was active – but associations of passive continental margin sediments – are widespread in Proterozoic terrains – but the ophiolites so typical of younger convergent plate boundaries are rare, – although Neoarchean ophiolites are known

The Origin of Cratons • Certainly several small cratons – existed during the Archean – and grew by accretion along their margins • They amalgamated into a larger unit – during the Proterozoic • By the end of the Archean, – 30 -40% of the present volume – of continental crust existed • Archean crust probably evolved similarly – to the evolution of the southern Superior craton of Canada

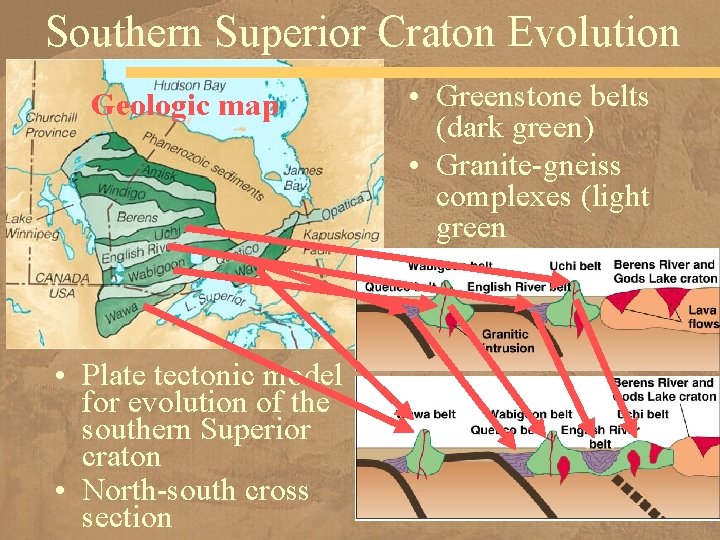

Southern Superior Craton Evolution Geologic map • Plate tectonic model for evolution of the southern Superior craton • North-south cross section • Greenstone belts (dark green) • Granite-gneiss complexes (light green

Canadian Shield • Deformation of the southern Superior craton – was part of a more extensive orogenic episode – during the Mesoarchean and Neoarchean – that formed the Superior and Slave cratons – and some Archean rocks in Wyoming, Montana, – and the Mississippi River Valley • By the time this Archean event ended – several cratons had formed that are found – in the older parts of the Canadian shield

Atmosphere and Hydrosphere • Earth’s early atmosphere and hydrosphere – were quite different than they are now • They also played an important role – in the development of the biosphere • Today’s atmosphere is mostly – nitrogen (N 2) – abundant free oxygen (O 2), • or oxygen not combined with other elements • such as in carbon dioxide (CO 2) – water vapor (H 2 O) – small amounts of other gases, like ozone (O 3) • which is common enough in the upper atmosphere • to block most of the Sun’s ultraviolet radiation

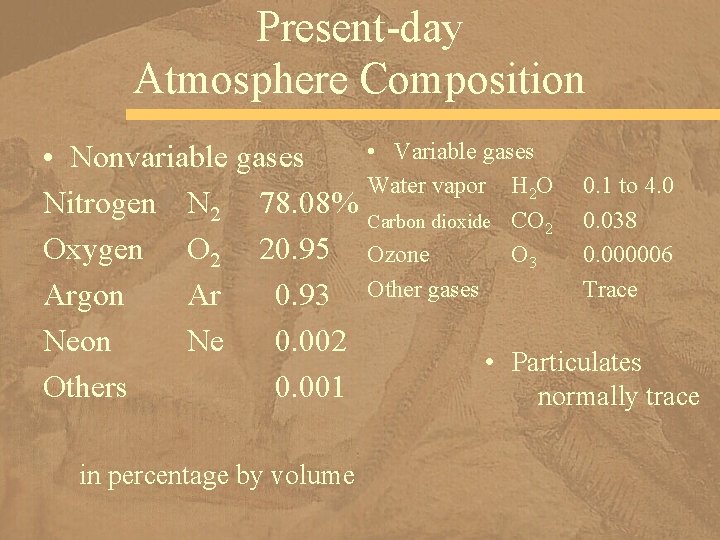

Present-day Atmosphere Composition • Variable gases • Nonvariable gases Water vapor H 2 O 0. 1 to 4. 0 Nitrogen N 2 78. 08% Carbon dioxide CO 0. 038 2 Oxygen O 2 20. 95 Ozone O 3 0. 000006 Trace Argon Ar 0. 93 Other gases Neon Ne 0. 002 • Particulates Others 0. 001 normally trace in percentage by volume

Earth’s Very Early Atmosphere • Earth’s very early atmosphere was probably composed of – hydrogen and helium, • the most abundant gases in the universe • If so, it would have quickly been lost into space – because Earth’s gravity is insufficient to retain them – because Earth had no magnetic field until its core formed (magnetosphere) • Without a magnetic field, – the solar wind would have swept away – any atmospheric gases

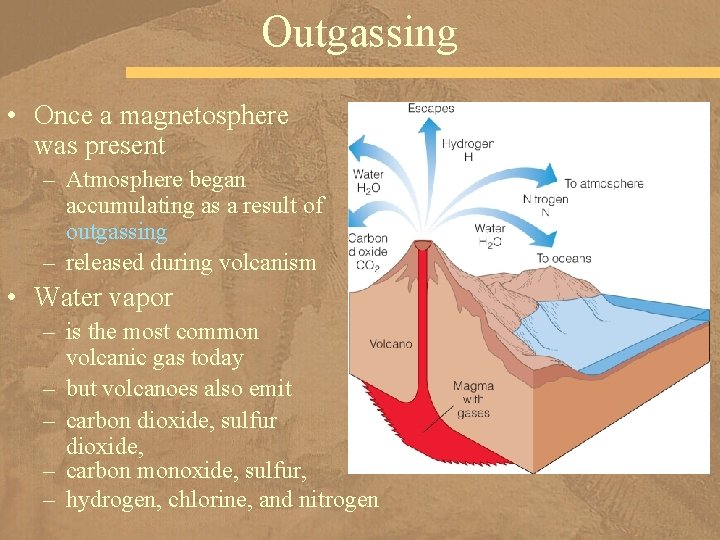

Outgassing • Once a magnetosphere was present – Atmosphere began accumulating as a result of outgassing – released during volcanism • Water vapor – is the most common volcanic gas today – but volcanoes also emit – carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, – carbon monoxide, sulfur, – hydrogen, chlorine, and nitrogen

Archean Atmosphere • Archean volcanoes probably – emitted the same gases, – and thus an atmosphere developed – but one lacking free oxygen and an ozone layer • It was rich in carbon dioxide, – and gases reacting in this early atmosphere – probably formed • ammonia (NH 3) • methane (CH 4) • This early atmosphere persisted – throughout the Archean

Evidence for an Oxygen-Free Atmosphere • The atmosphere was chemically reducing – rather than an oxidizing one • Some of the evidence for this conclusion – comes from detrital deposits – containing minerals that oxidize rapidly – in the presence of oxygen • pyrite (Fe. S 2) • uraninite (UO 2) • But oxidized iron becomes – increasingly common in Proterozoic rocks – indicating that at least some free oxygen – was present then

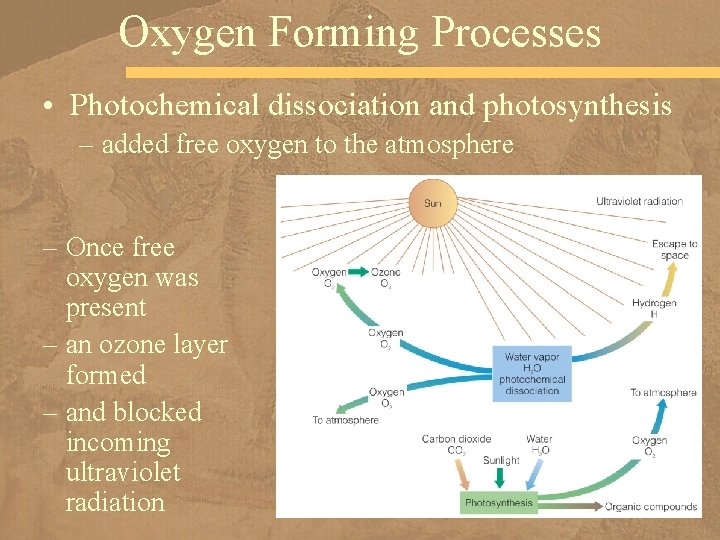

Introduction of Free Oxygen • Two processes account for – introducing free oxygen into the atmosphere, • one or both of which began during the Eoarchean. 1. Photochemical dissociation involves ultraviolet radiation in the upper atmosphere • The radiation disrupts water molecules and releases their oxygen and hydrogen • This could account for 2% of present-day oxygen • but with 2% oxygen, ozone forms, creating a barrier against ultraviolet radiation 2. More important were the activities of organisms that practiced photosynthesis

Photosynthesis • Photosynthesis is a metabolic process – in which carbon dioxide and water – to make organic molecules – and oxygen is released as a waste product CO 2 + H 2 O ==> organic compounds + O 2 • Even with photochemical dissociation – and photosynthesis, – probably no more than 1% of the free oxygen level – of today was present by the end of the Archean

Oxygen Forming Processes • Photochemical dissociation and photosynthesis – added free oxygen to the atmosphere – Once free oxygen was present – an ozone layer formed – and blocked incoming ultraviolet radiation

Earth’s Surface Waters • Outgassing was responsible – for the early atmosphere – and also for some of Earth’s surface water • the hydrosphere – most of which is in the oceans • more than 97% • Another source of our surface water – was meteorites and icy comets • Numerous erupting volcanoes, – and an early episode of intense meteorite and comet bombardment • accounted for rapid rate of surface water accumulation

Ocean Water • Volcanoes still erupt and release water vapor – Is the volume of ocean water still increasing? – Perhaps it is, but if so, the rate – has decreased considerably – because the amount of heat needed – to generate magma has diminished

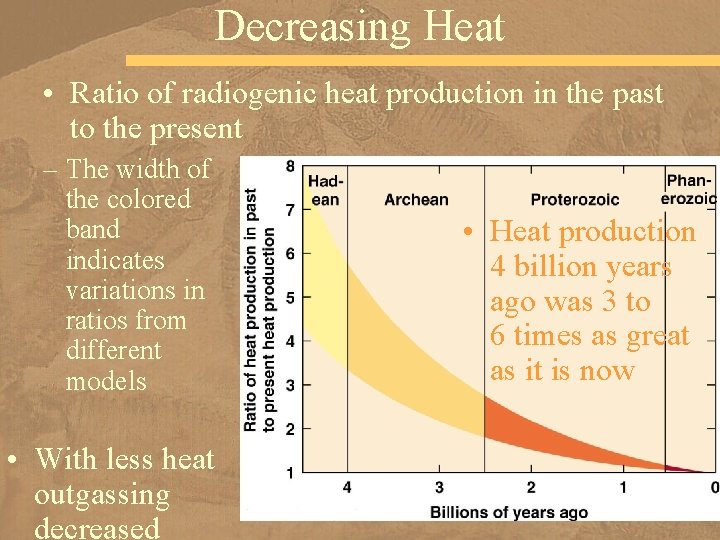

Decreasing Heat • Ratio of radiogenic heat production in the past to the present – The width of the colored band indicates variations in ratios from different models • With less heat outgassing decreased • Heat production 4 billion years ago was 3 to 6 times as great as it is now

First Organisms • Today, Earth’s biosphere consists – of millions of species of archea, bacteria, fungi, – protists, plants, and animals, – whereas only bacteria and archea are found in Archean rocks • We have fossils from Archean rocks – 3. 5 billion years old • Chemical evidence in rocks in Greenland – that are 3. 8 billion years old – convince some investigators that organisms were present then

What Is Life? • Minimally, a living organism must reproduce – and practice some kind of metabolism • Reproduction ensures – the long-term survival of a group of organisms • whereas metabolism – maintains the organism • The distinction between – living and nonliving things is not always easy • Are viruses living? – When in a host cell they behave like living organisms – but outside they neither reproduce nor metabolize

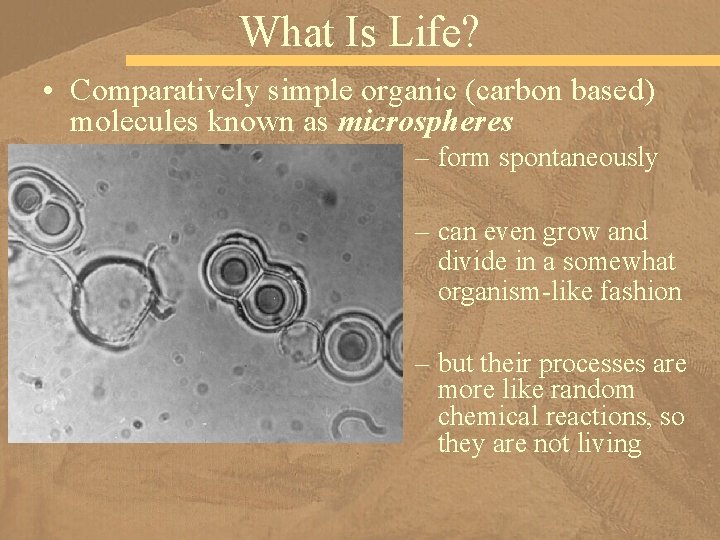

What Is Life? • Comparatively simple organic (carbon based) molecules known as microspheres – form spontaneously – can even grow and divide in a somewhat organism-like fashion – but their processes are more like random chemical reactions, so they are not living

How Did Life First Originate? • To originate by natural processes, – from non-living matter (abiogenesis), life must have passed through a prebiotic stages – in which it showed signs of living – but was not truly living • The origin of life has 2 requirements – a source of appropriate elements for organic molecules – energy sources to promote chemical reactions

Elements of Life • All organisms are composed mostly of – carbon (C) – hydrogen (H) – nitrogen (N) – oxygen (O) • all of which were present in Earth’s early atmosphere as – carbon dioxide (CO 2) – water vapor (H 2 O) – nitrogen (N 2) – and possibly methane (CH 4) – and ammonia (NH 3)

Basic Building Blocks of Life • Energy from • Lightning, volcanism, • and ultraviolet radiation – probably promoted chemical reactions – during which C, H, N, and O combined – to form monomers • such as amino acids • Monomers are the basic building blocks – of more complex organic molecules

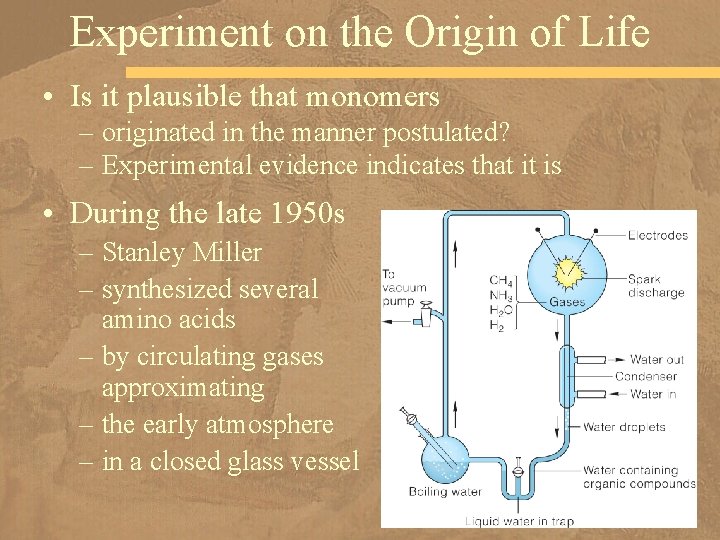

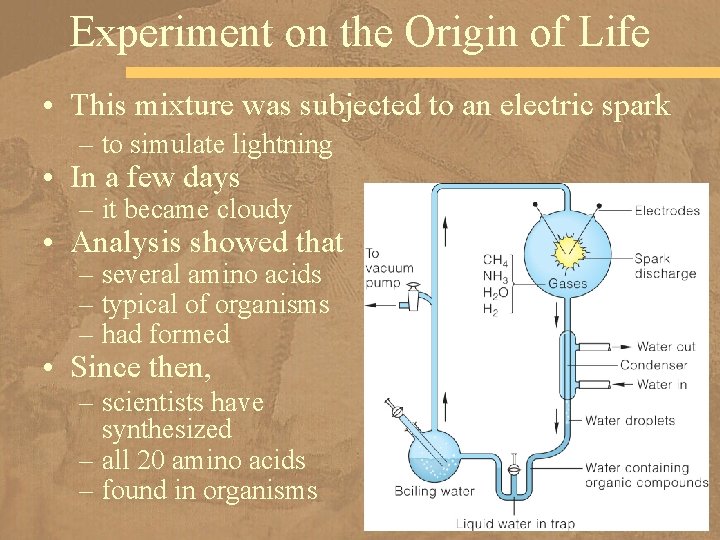

Experiment on the Origin of Life • Is it plausible that monomers – originated in the manner postulated? – Experimental evidence indicates that it is • During the late 1950 s – Stanley Miller – synthesized several amino acids – by circulating gases approximating – the early atmosphere – in a closed glass vessel

Experiment on the Origin of Life • This mixture was subjected to an electric spark – to simulate lightning • In a few days – it became cloudy • Analysis showed that – several amino acids – typical of organisms – had formed • Since then, – scientists have synthesized – all 20 amino acids – found in organisms

Polymerization • The molecules of organisms are polymers – such as proteins – and nucleic acids • RNA (ribonucleic acid) and DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) – consisting of monomers linked together in a specific sequence • How did polymerization take place? • Water usually causes depolymerization, – however, researchers synthesized molecules – known as proteinoids or thermal proteins – some of which consist of – more than 200 linked amino acids – when heating dehydrated concentrated amino acids

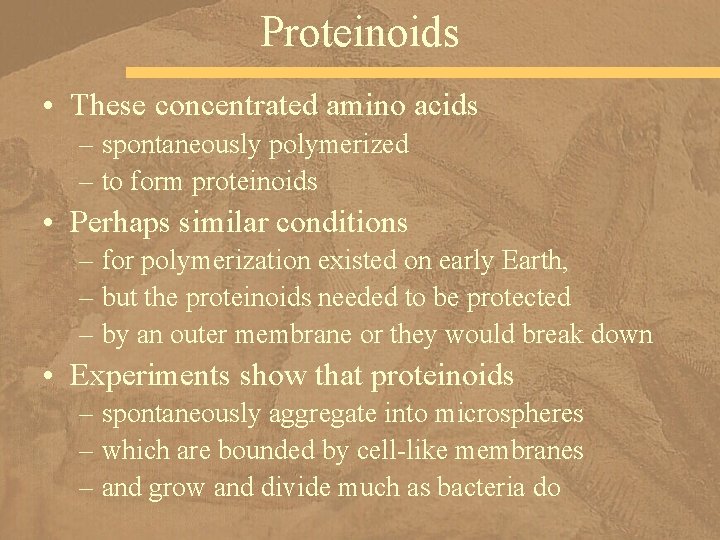

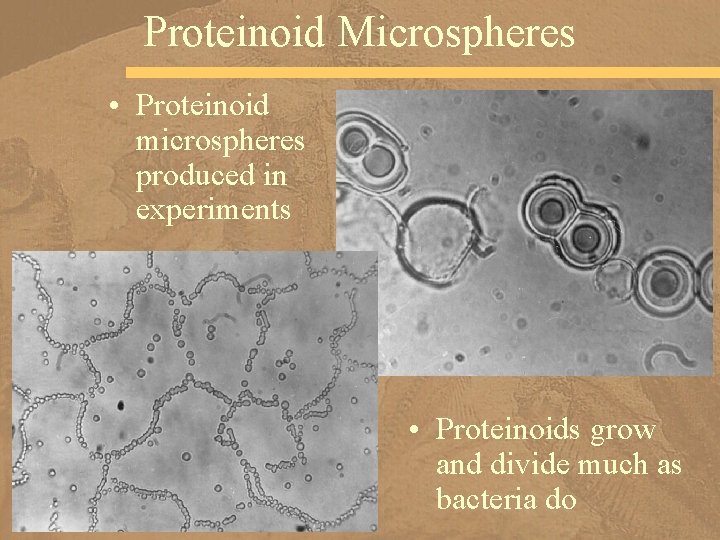

Proteinoids • These concentrated amino acids – spontaneously polymerized – to form proteinoids • Perhaps similar conditions – for polymerization existed on early Earth, – but the proteinoids needed to be protected – by an outer membrane or they would break down • Experiments show that proteinoids – spontaneously aggregate into microspheres – which are bounded by cell-like membranes – and grow and divide much as bacteria do

Proteinoid Microspheres • Proteinoid microspheres produced in experiments • Proteinoids grow and divide much as bacteria do

Protobionts • These proteinoid molecules can be referred to as protobionts – that are intermediate between – inorganic chemical compounds – and living organisms

Monomer and Proteinoid Soup • The origin-of-life experiments are interesting, – but what is their relationship to early Earth? • Monomers likely formed continuously and by the billions – and accumulated in the early oceans into a “hot, dilute soup” – The amino acids in the “soup” – might have washed up onto a beach or perhaps cinder cones – where they were concentrated by evaporation – and polymerized by heat • The polymers then washed back into the ocean – where they reacted further

Next Critical Step • Not much is known about the next critical step – in the origin of life • the development of a reproductive mechanism • The microspheres divide – and may represent a protoliving system – but in today’s cells, nucleic acids, • either RNA or DNA – are necessary for reproduction • The problem is that nucleic acids – cannot replicate without protein enzymes, – and the appropriate enzymes – cannot be made without nucleic acids, – or so it seemed until fairly recently

RNA World? • Now we know that small RNA molecules – can replicate without the aid of protein enzymes • Thus, the first replicating systems – may have been RNA molecules • Some researchers propose – an early “RNA world” – in which these molecules were intermediate between • inorganic chemical compounds • and the DNA-based molecules of organisms • How RNA was naturally synthesized – remains an unsolved problem

Much Remains to Be Learned • Scientists agree on some basic requirements – for the origin of life, – but the exact steps involved – and significance of results are debated • Many researchers believe that – the earliest organic molecules were synthesized from atmospheric gases – but some scientist suggest that life arose instead – near hydrothermal vents on the seafloor

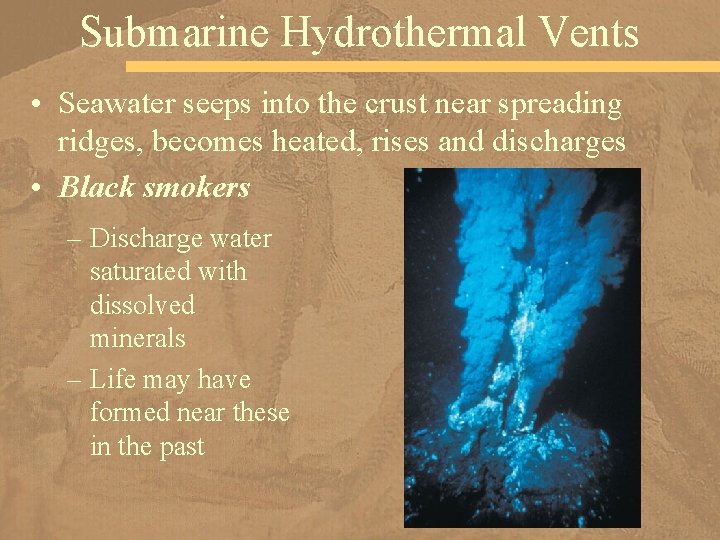

Submarine Hydrothermal Vents • Seawater seeps into the crust near spreading ridges, becomes heated, rises and discharges • Black smokers – Discharge water saturated with dissolved minerals – Life may have formed near these in the past

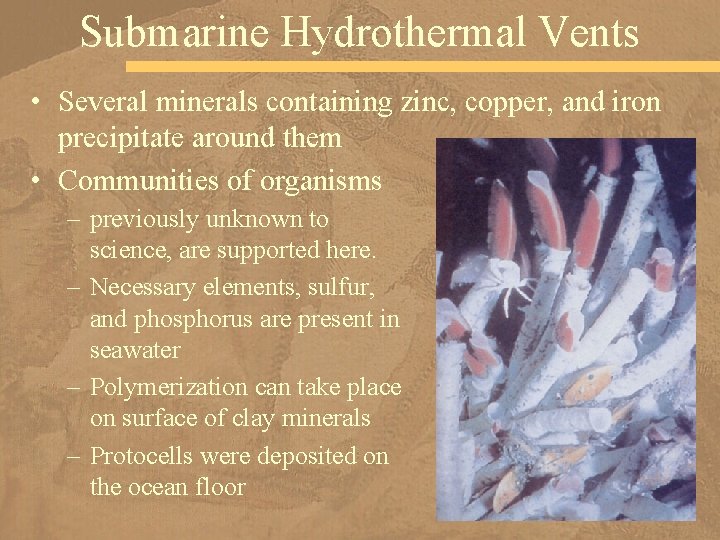

Submarine Hydrothermal Vents • Several minerals containing zinc, copper, and iron precipitate around them • Communities of organisms – previously unknown to science, are supported here. – Necessary elements, sulfur, and phosphorus are present in seawater – Polymerization can take place on surface of clay minerals – Protocells were deposited on the ocean floor

Oldest Known Organisms • The first organisms were archaea and bacteria – both of which consist of prokaryotic cells, – cells that lack an internal, membrane-bounded nucleus and other structures • Prior to the 1950 s, scientists assumed that life – must have had a long early history – but the fossil record offered little to support this idea • The Precambrian, once called Azoic – (“without life”), seemed devoid of life

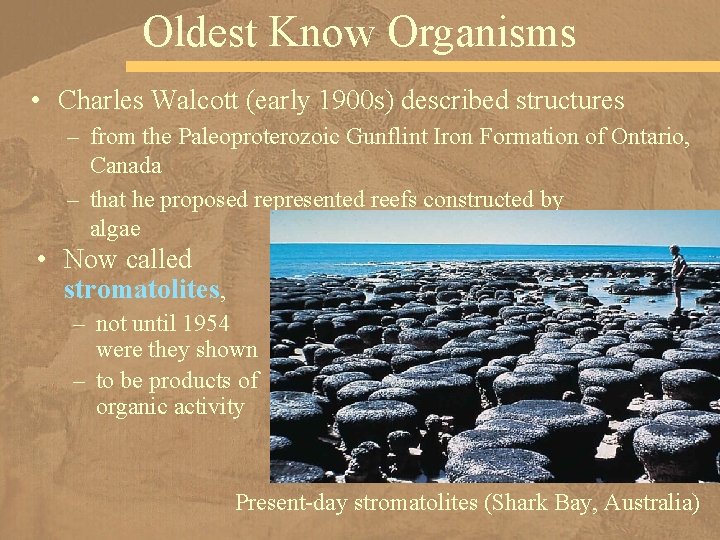

Oldest Know Organisms • Charles Walcott (early 1900 s) described structures – from the Paleoproterozoic Gunflint Iron Formation of Ontario, Canada – that he proposed represented reefs constructed by algae • Now called stromatolites, – not until 1954 were they shown – to be products of organic activity Present-day stromatolites (Shark Bay, Australia)

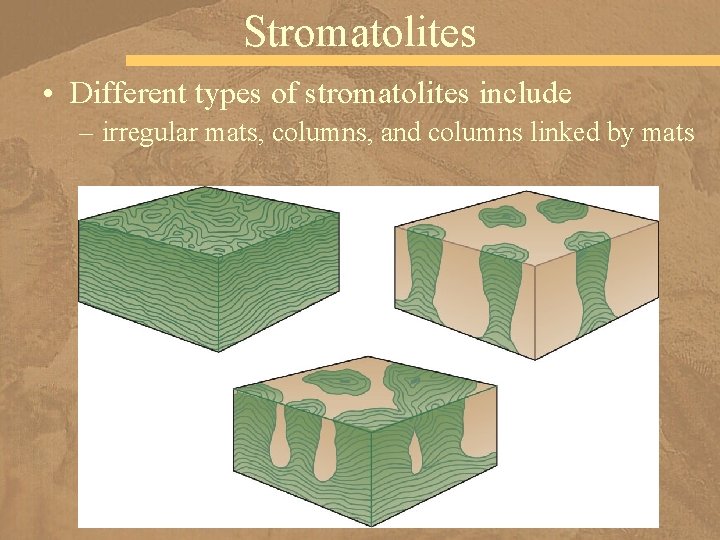

Stromatolites • Different types of stromatolites include – irregular mats, columns, and columns linked by mats

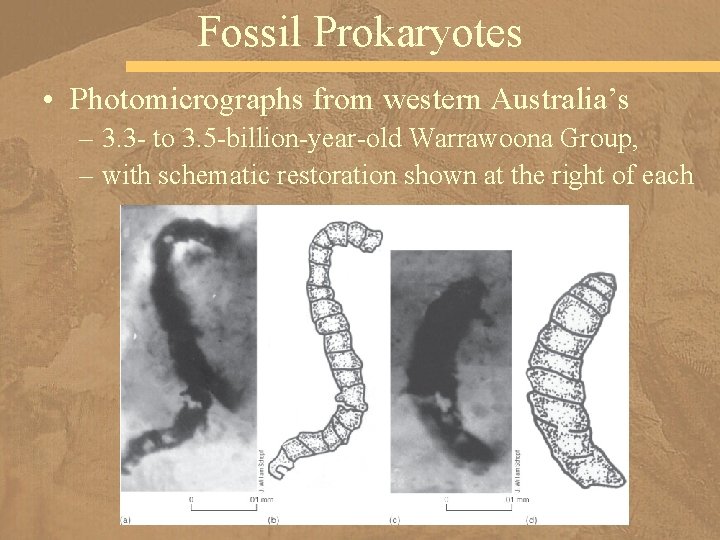

Stromatolites • Present-day stromatolites form and grow – as sediment grains are trapped – on sticky mats – of photosynthesizing cyanobacteria – although now they are restricted – to environments where snails cannot live • The oldest known undisputed stromatolites – are found in rocks in South Africa – that are 3. 0 billion years old – but probable ones are also known – from the Warrawoona Group in Australia – which is 3. 3 to 3. 5 billion years old

Other Evidence of Early Life • Chemical evidence in rocks 3. 85 billion years old – in Greenland indicate life was perhaps present then • The oldest known cyanobacteria – were photosynthesizing organisms – but photosynthesis is a complex metabolic process • A simpler type of metabolism – must have preceded it • No fossils are known of these earliest organisms

Earliest Organisms • The earliest organisms must have resembled – tiny anaerobic bacteria – meaning they required no oxygen • They must have totally depended – on an external source of nutrients – that is, they were heterotrophic – as opposed to autotrophic organisms • that make their own nutrients, as in photosynthesis • They all had prokaryotic cells

Earliest Organisms • The earliest organisms, then, – were anaerobic, heterotrophic prokaryotes • Their nutrient source was most likely – adenosine triphosphate (ATP) – from their environment – which was used to drive – the energy-requiring reactions in cells • ATP can easily be synthesized – from simple gases and phosphate – so it was available – in the early Earth environment

Fermentation • Obtaining ATP from the surroundings – could not have persisted for long – because more and more cells competed – for the same resources • The first organisms to develop – a more sophisticated metabolism – probably used fermentation – to meet their energy needs • Fermentation is an anaerobic process – in which molecules such as sugars are split – releasing carbon dioxide, alcohol, and energy

Photosynthesis • A very important biological event – occurring in the Archean – was the development of – the autotrophic process of photosynthesis • This may have happened – as much as 3. 5 billion years ago • These prokaryotic cells were still anaerobic, – but as autotrophs they were no longer dependent – on preformed organic molecules – as a source of nutrients

Fossil Prokaryotes • Photomicrographs from western Australia’s – 3. 3 - to 3. 5 -billion-year-old Warrawoona Group, – with schematic restoration shown at the right of each

Archean Mineral Resources • A variety of mineral deposits are of Archean-age – but gold is the most commonly associated, – although it is also found – in Proterozoic and Phanerozoic rocks • This soft yellow metal is prized for jewelry, – but it is or has been used as a monetary standard, – in glass making, electric circuitry, and chemical industry • About half the world’s gold since 1886 – has come from Archean and Proterozoic rocks – in South Africa • Gold mines also exist in Archean rocks – of the Superior craton in Canada

Archean Sulfide Deposits • Archean sulfide deposits of • zinc, • copper • and nickel – occur in Australia, Zimbabwe, – and in the Abitibi greenstone belt – in Ontario, Canada • Some, at least, formed as mineral deposits – next to hydrothermal vents on the seafloor, – much as they do now around black smokers

Chrome • About 1/4 of Earth’s chrome reserves – are in Archean rocks, especially in Zimbabwe • These ore deposits are found in – the volcanic units of greenstone belts – where they appear to have formed – when crystals settled and became concentrated – in the lower parts of plutons – such as mafic and ultramafic sills • Chrome is needed in the steel industry • The United States has very few chrome deposits – so must import most of what it uses

Chrome and Platinum • One chrome deposit in the United States – is in the Stillwater Complex in Montana • Low-grade ores were mined there during war times, – but they were simply stockpiled – and never refined for chrome • These rocks also contain platinum, – a precious metal, that is used • in the automotive industry in catalytic converters • in the chemical industry • for cancer chemotherapy

Iron • Banded Iron formations are sedimentary rocks – consisting of alternating layers – of silica (chert) and iron minerals • About 6% of the world’s – banded iron formations were deposited – during the Archean Eon • Although Archean iron ores – are mined in some areas – they are neither as thick – nor as extensive as those of the Proterozoic Eon, – which constitute the world’s major source of iron

Pegmatites • Pegmatites are very coarsely crystalline igneous rocks, – commonly associated with granite plutons • Some Archean pegmatites, – such in the Herb Lake district in Manitoba, Canada, – and Rhodesian Province in Africa, – contain valuable minerals • In addition to minerals of gem quality, – Archean pegmatites contain minerals mined – for lithium, beryllium, rubidium, and cesium

Summary • Precambrian encompasses all geologic time – from Earth’s origin – to the beginning of the Phanerozoic Eon – The term also refers to all rocks – that lie stratigraphically below Cambrian rocks • The Precambrian is divided into two eons – the Archean and the Proterozoic, – which are further subdivided • Rocks from the latter part of the Eoarchean indicate crust must have existed, – but very little of it has been preserved

Summary • All continents have an ancient stable nucleus – or craton made up of • an exposed shield • and a buried platform • The exposed part of the North American craton – is the Canadian shield, – and is make up of smaller units – delineated by their ages and structural trends • Archean greenstone belts are linear, – syncline-like bodies found within – much more extensive granite-gneiss complexes

Summary • Greenstone belts typically consist of – two lower units dominated by igneous rocks – and an upper unit of mostly sedimentary rocks • They probably formed in back-arc basins – and in intracontinental rifts • Many geologists are convinced – some type of Archean plate tectonics occurred, – but plates probably moved faster – and igneous activity was more common – because Earth had more radiogenic heat

Summary • The early atmosphere and hydrosphere – formed as a result of outgassing, – but this atmosphere lacked free oxygen and – contained abundant water vapor and carbon dioxide • Models for the origin of life by natural processes require – an oxygen deficient atmosphere, – the necessary elements for organic molecules, – and energy to promote the synthesis – of organic molecules

Summary • The first naturally formed organic molecules – were probably monomers, – such as amino acids, – that linked together to form – more complex polymers such as proteins • RNA molecules may have been – the first molecules capable of self-replication – However, how a reproductive mechanism evolved is not known

Summary • The only known Archean fossils – are of single-celled, prokaryotic bacteria or cyanobacteria – but other chemical evidence may indicate presence of archaea • Stromatolites formed by photosynthesizing bacteria – are found in rocks as much as 3. 5 billion years old • Archean mineral resources include gold, chrome, zinc, copper, and nickel

- Slides: 94