Chapter 8 METABOLISM Copyright 2005 Pearson Education Inc

Chapter 8 METABOLISM Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

The living cell – Is a miniature factory – Where thousands of reactions occur – Converts energy in many ways Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

• Metabolism – The sum of all chemical reactions in an organism – Arises from interactions between molecules Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

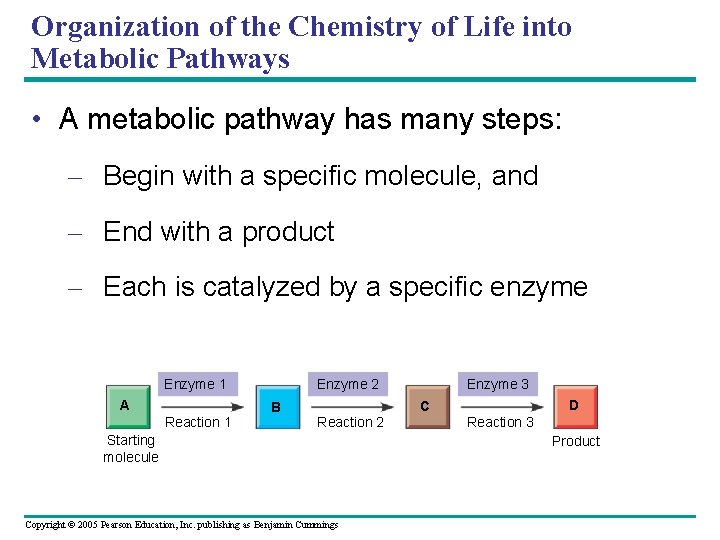

Organization of the Chemistry of Life into Metabolic Pathways • A metabolic pathway has many steps: – Begin with a specific molecule, and – End with a product – Each is catalyzed by a specific enzyme Enzyme 1 A Enzyme 2 D C B Reaction 1 Enzyme 3 Reaction 2 Starting molecule Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings Reaction 3 Product

• Catabolic (reactions) pathways – Break down complex molecules into simpler compounds – Also called hydrolysis reactions – Release energy • Anabolic (reactions)pathways – Build complicated molecules from simpler ones – Consume energy – Also known as dehydration reaction Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

Forms of Energy • Energy – Is the capacity to cause change – Exists in various forms – Some forms can perform work • Kinetic energy – Associated with motion • Potential energy – Stored in the location of matter – Includes chemical energy: • Stored in molecular structure Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

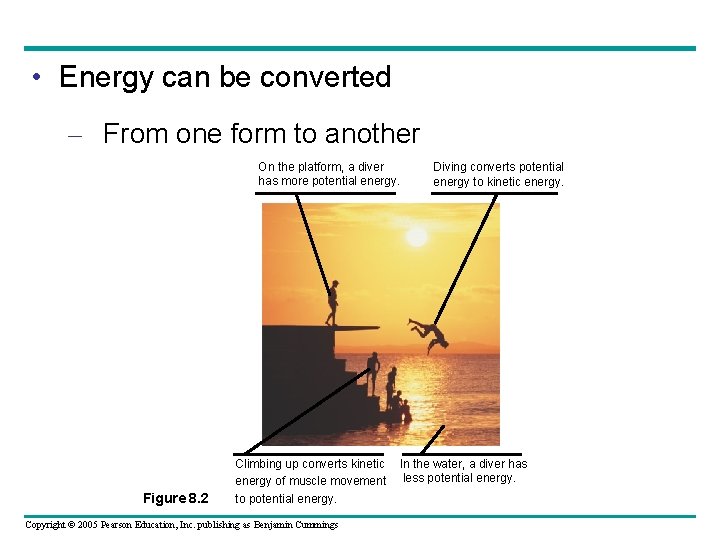

• Energy can be converted – From one form to another On the platform, a diver has more potential energy. Figure 8. 2 Climbing up converts kinetic energy of muscle movement to potential energy. Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings Diving converts potential energy to kinetic energy. In the water, a diver has less potential energy.

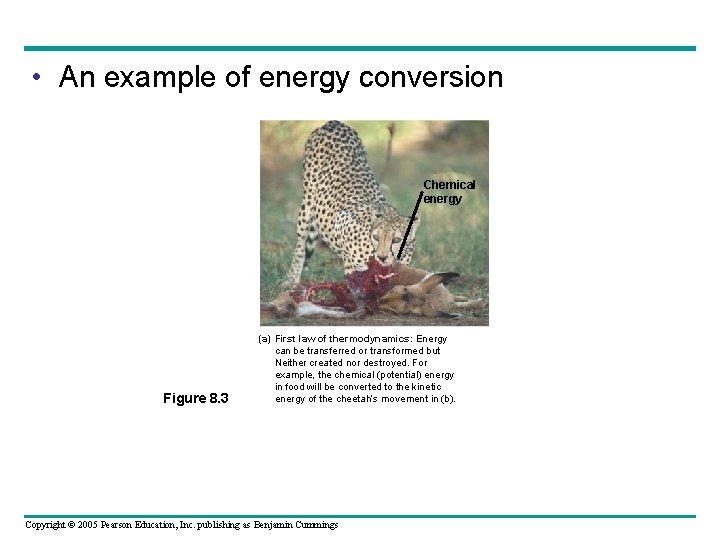

• An example of energy conversion Chemical energy Figure 8. 3 (a) First law of thermodynamics: Energy can be transferred or transformed but Neither created nor destroyed. For example, the chemical (potential) energy in food will be converted to the kinetic energy of the cheetah’s movement in (b). Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

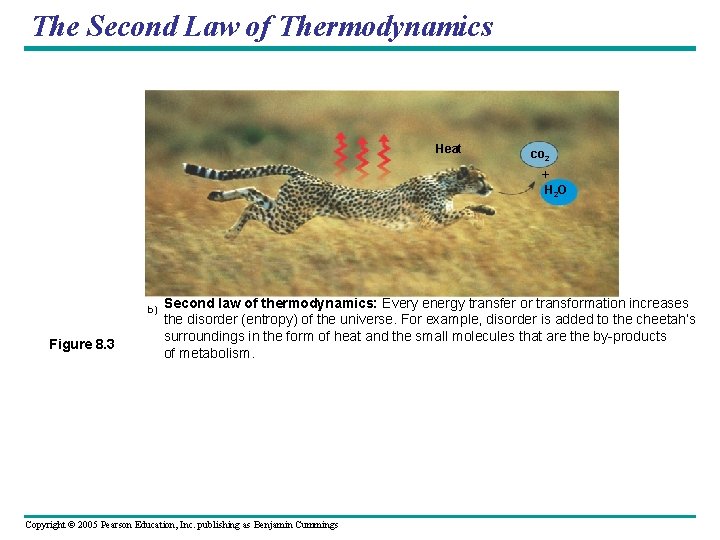

The Laws of Energy Transformation • Thermodynamics – Is the study of energy transformations • First law of thermodynamics: – Energy can be transferred and transformed – Energy cannot be created or destroyed • Second law of thermodynamics: – Spontaneous changes that do not require outside energy increase the entropy, or disorder, of the universe Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

The Second Law of Thermodynamics Heat co 2 + H 2 O b) Figure 8. 3 Second law of thermodynamics: Every energy transfer or transformation increases the disorder (entropy) of the universe. For example, disorder is added to the cheetah’s surroundings in the form of heat and the small molecules that are the by-products of metabolism. Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

Free-Energy Change, G • The free-energy change of a reaction: – It tells us whether the reaction occurs spontaneously • A living system’s free energy: – Is the portion of energy that can perform work under cellular conditions Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

Free Energy and Metabolism § Base on their free energy changes, chemical reaction are classified into: § Exergenic reactions: § Proceed with release of energy § Are spontaneous § Endergenic reaction: § Absorb energy § nonspontaneous Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

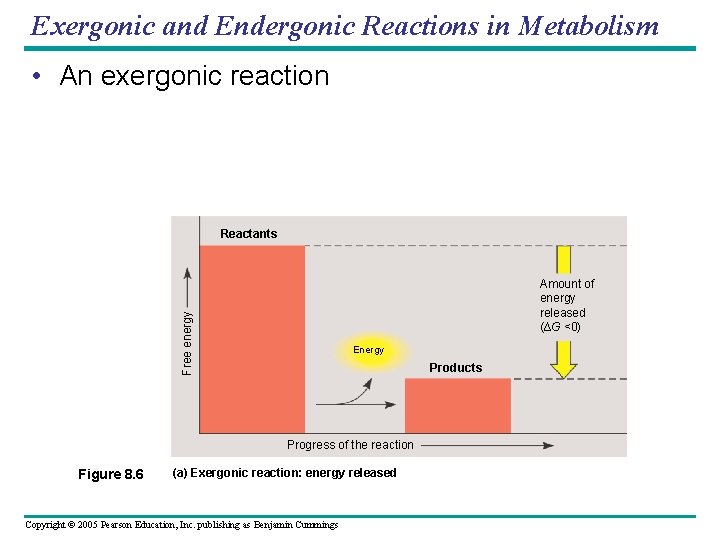

Exergonic and Endergonic Reactions in Metabolism • An exergonic reaction Reactants Free energy Amount of energy released (∆G <0) Energy Products Progress of the reaction Figure 8. 6 (a) Exergonic reaction: energy released Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

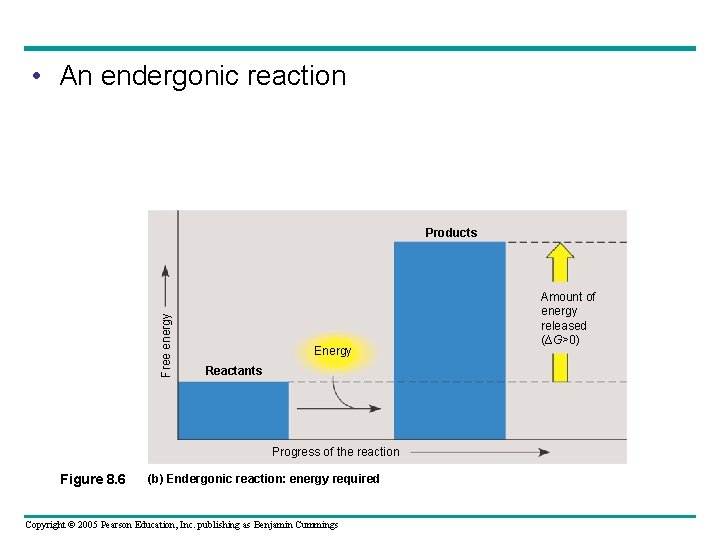

• An endergonic reaction Free energy Products Energy Reactants Progress of the reaction Figure 8. 6 (b) Endergonic reaction: energy required Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings Amount of energy released (∆G>0)

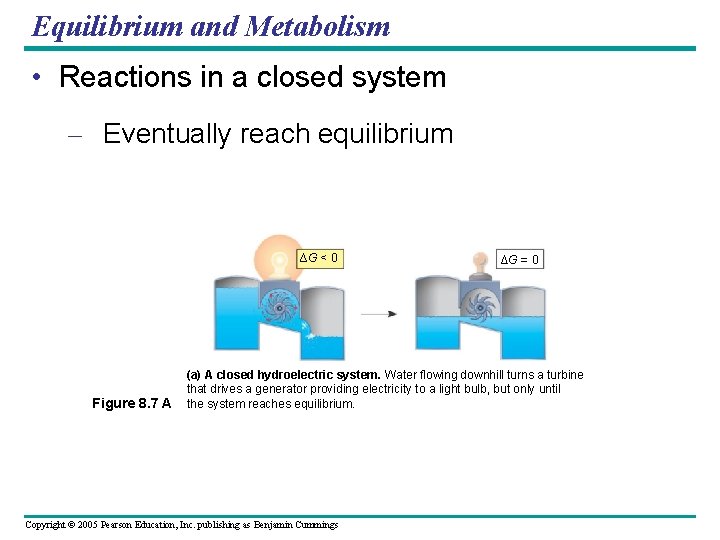

Equilibrium and Metabolism • Reactions in a closed system – Eventually reach equilibrium ∆G < 0 Figure 8. 7 A ∆G = 0 (a) A closed hydroelectric system. Water flowing downhill turns a turbine that drives a generator providing electricity to a light bulb, but only until the system reaches equilibrium. Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

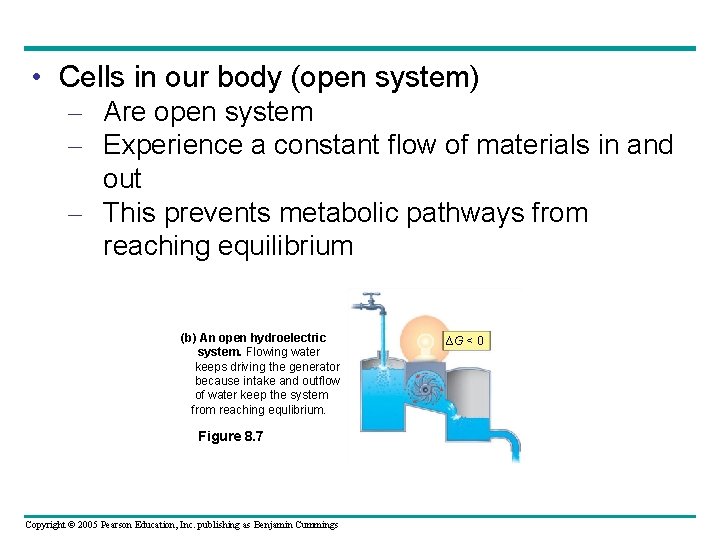

• Cells in our body (open system) – Are open system – Experience a constant flow of materials in and out – This prevents metabolic pathways from reaching equilibrium (b) An open hydroelectric system. Flowing water keeps driving the generator because intake and outflow of water keep the system from reaching equlibrium. Figure 8. 7 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings ∆G < 0

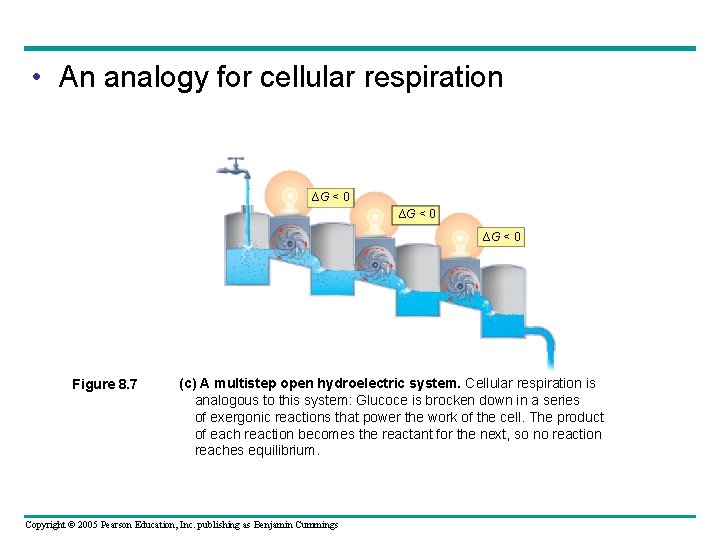

• An analogy for cellular respiration ∆G < 0 Figure 8. 7 (c) A multistep open hydroelectric system. Cellular respiration is analogous to this system: Glucoce is brocken down in a series of exergonic reactions that power the work of the cell. The product of each reaction becomes the reactant for the next, so no reaction reaches equilibrium. Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

• ATP powers cellular work by coupling: – Exergonic reactions to endergonic reactions • A cell does three main kinds of work: – Mechanical – Transport – Chemical Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

• Energy coupling – Is a key feature in the way cells manage their energy resources to do this work Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

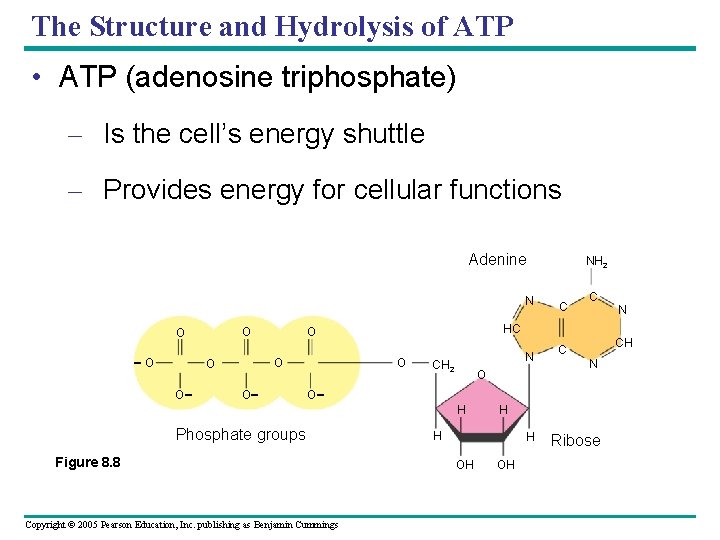

The Structure and Hydrolysis of ATP • ATP (adenosine triphosphate) – Is the cell’s energy shuttle – Provides energy for cellular functions Adenine N O O - O - O O C C N HC O O O NH 2 - Phosphate groups Figure 8. 8 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings N CH 2 O H N H H H OH CH C OH Ribose

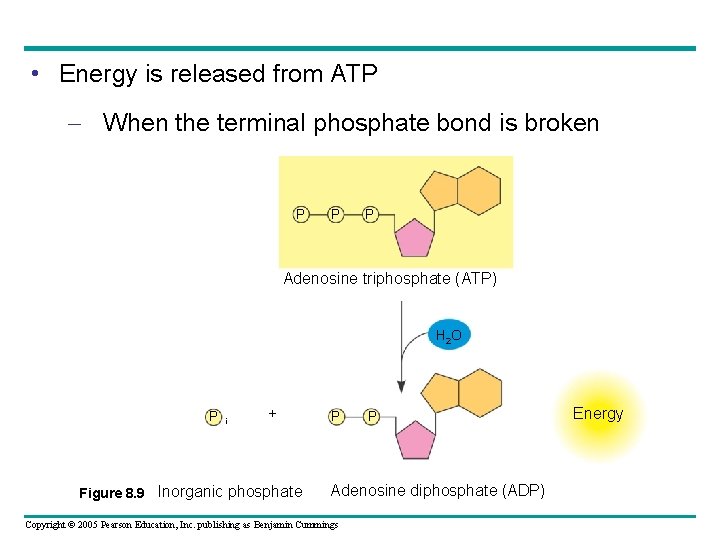

• Energy is released from ATP – When the terminal phosphate bond is broken P P P Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) H 2 O P i + Figure 8. 9 Inorganic phosphate P P Adenosine diphosphate (ADP) Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings Energy

How ATP Performs Work • ATP drives endergonic reactions by: – Phosphorylation of (transferring a phosphate to) other molecules Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

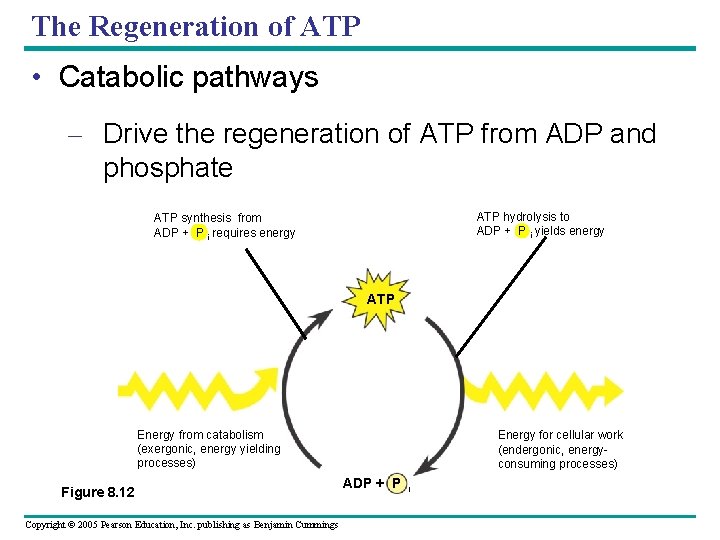

The Regeneration of ATP • Catabolic pathways – Drive the regeneration of ATP from ADP and phosphate ATP hydrolysis to ADP + P i yields energy ATP synthesis from ADP + P i requires energy ATP Energy from catabolism (exergonic, energy yielding processes) Figure 8. 12 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings Energy for cellular work (endergonic, energyconsuming processes) ADP + P i

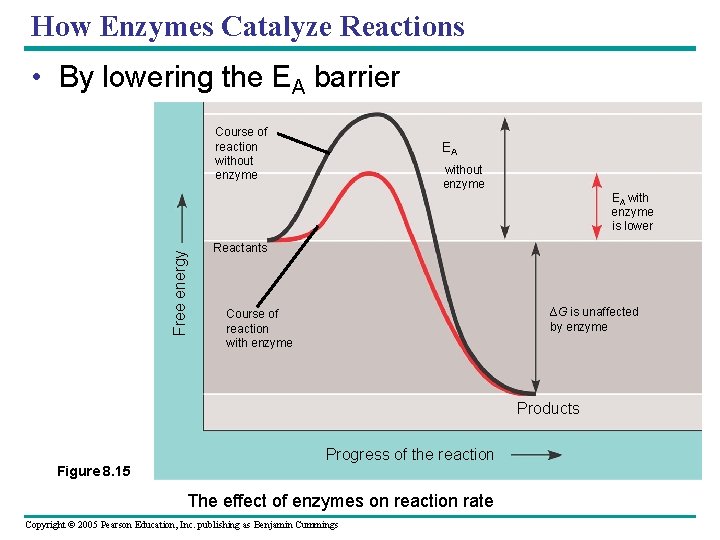

• Enzymes speed up metabolic reactions by: – Lowering the activation energy • A catalyst – A chemical agent that speeds up a reaction – Not consumed by the reaction • An enzyme – A catalytic protein Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

The Activation Barrier • Every chemical reaction between molecules Involves both: – Bond breaking, and – Bond forming Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

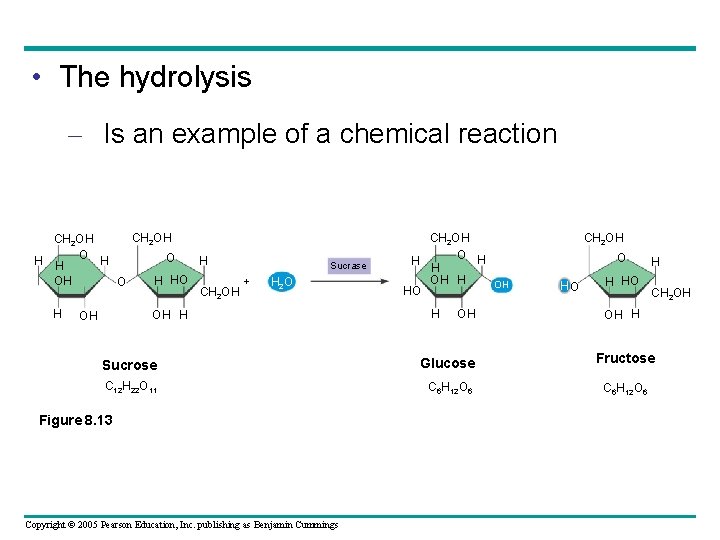

• The hydrolysis – Is an example of a chemical reaction CH 2 OH O O H H OH H HO O + CH 2 OH H Sucrase H 2 O OH H OH CH 2 OH O H H H OH HO H OH CH 2 OH O HO H CH 2 OH OH H Sucrose Glucose Fructose C 12 H 22 O 11 C 6 H 12 O 6 Figure 8. 13 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

• The activation energy, EA – Is the initial amount of energy needed to start a chemical reaction – Is often supplied in the form of heat from the surroundings in a system Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

How Enzymes Catalyze Reactions • By lowering the EA barrier Free energy Course of reaction without enzyme EA with enzyme is lower Reactants ∆G is unaffected by enzyme Course of reaction with enzyme Products Progress of the reaction Figure 8. 15 The effect of enzymes on reaction rate Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

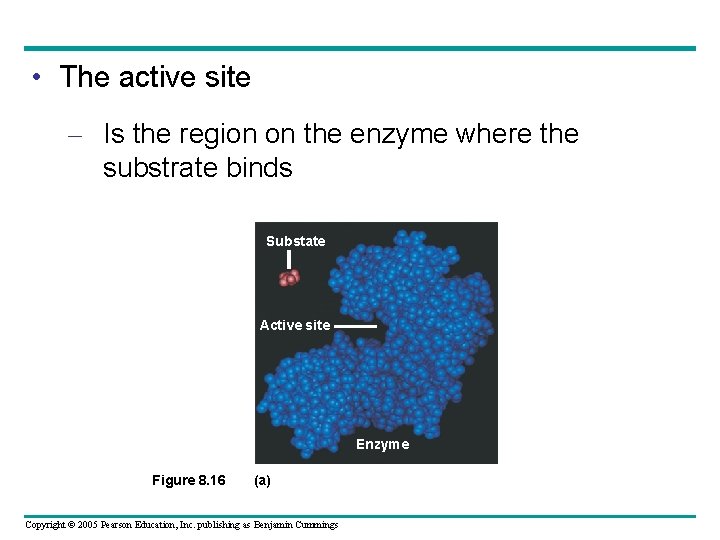

Substrate Specificity of Enzymes • The substrate – The reactant that an enzyme acts on • The enzyme – Binds to its substrate – Forms an enzyme-substrate complex Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

• The active site – Is the region on the enzyme where the substrate binds Substate Active site Enzyme Figure 8. 16 (a) Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

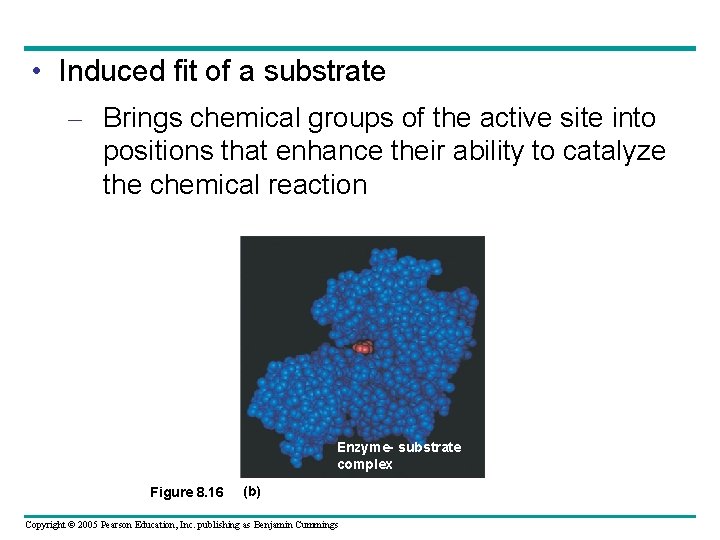

• Induced fit of a substrate – Brings chemical groups of the active site into positions that enhance their ability to catalyze the chemical reaction Enzyme- substrate complex Figure 8. 16 (b) Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

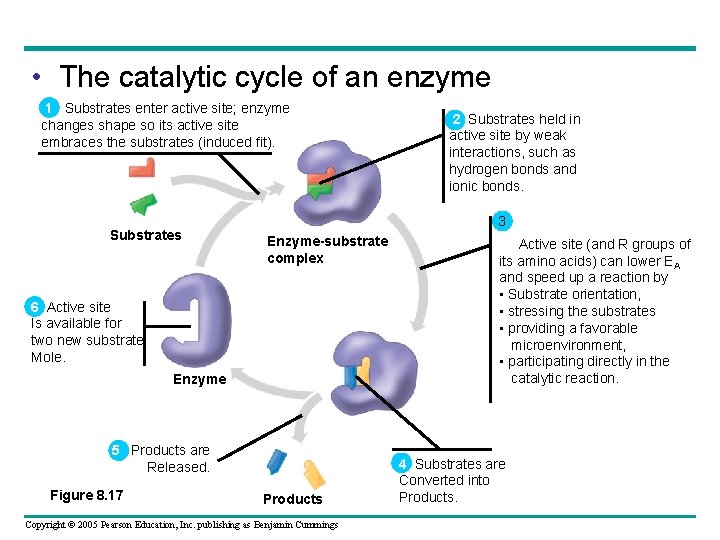

• The catalytic cycle of an enzyme 1 Substrates enter active site; enzyme changes shape so its active site embraces the substrates (induced fit). Substrates 3 Enzyme-substrate complex 6 Active site Is available for two new substrate Mole. Enzyme 5 Products are Released. Figure 8. 17 2 Substrates held in active site by weak interactions, such as hydrogen bonds and ionic bonds. Products Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings 3 Active site (and R groups of its amino acids) can lower EA and speed up a reaction by • Substrate orientation, • stressing the substrates • providing a favorable microenvironment, • participating directly in the catalytic reaction. 4 Substrates are Converted into Products.

• The active site can lower an EA barrier by – Orienting substrates correctly – Straining substrate bonds – Providing a favorable microenvironment – Covalently bonding to the substrate Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

Effects of Local Conditions on Enzyme Activity • The activity of an enzyme – Is affected by general environmental factors: • Temperature • p. H • Ionic concentration Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

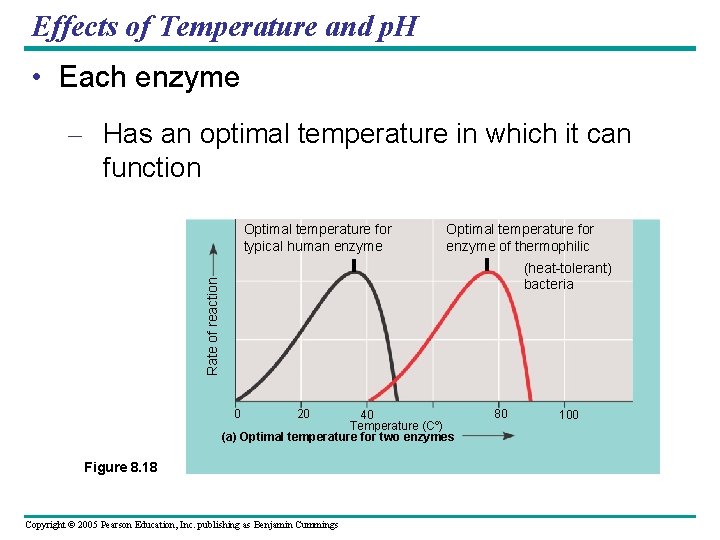

Effects of Temperature and p. H • Each enzyme – Has an optimal temperature in which it can function Optimal temperature for typical human enzyme Optimal temperature for enzyme of thermophilic Rate of reaction (heat-tolerant) bacteria 0 20 40 Temperature (Cº) (a) Optimal temperature for two enzymes Figure 8. 18 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings 80 100

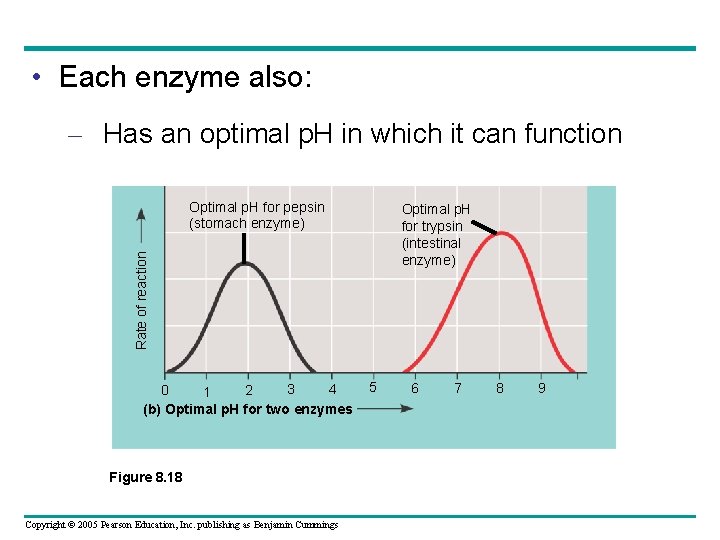

• Each enzyme also: – Has an optimal p. H in which it can function Optimal p. H for pepsin (stomach enzyme) Rate of reaction Optimal p. H for trypsin (intestinal enzyme) 3 4 0 2 1 (b) Optimal p. H for two enzymes Figure 8. 18 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings 5 6 7 8 9

Cofactors • Cofactors – Are nonprotein enzyme helpers • Coenzymes – Are organic cofactors Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

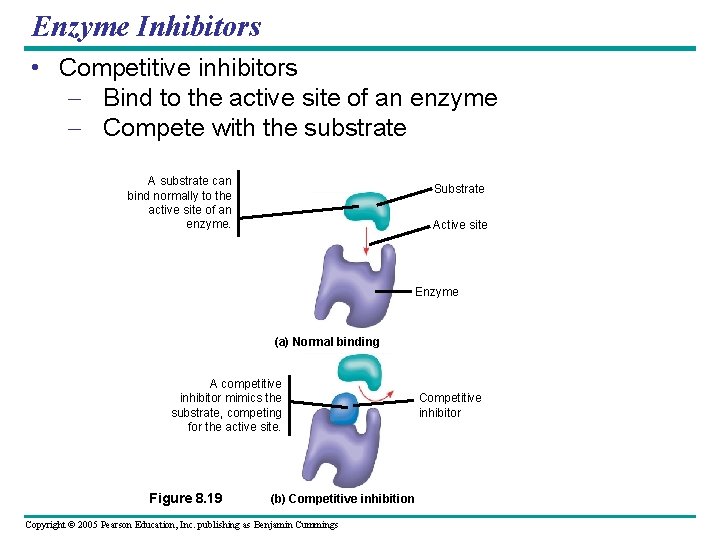

Enzyme Inhibitors • Competitive inhibitors – Bind to the active site of an enzyme – Compete with the substrate A substrate can bind normally to the active site of an enzyme. Substrate Active site Enzyme (a) Normal binding A competitive inhibitor mimics the substrate, competing for the active site. Figure 8. 19 (b) Competitive inhibition Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings Competitive inhibitor

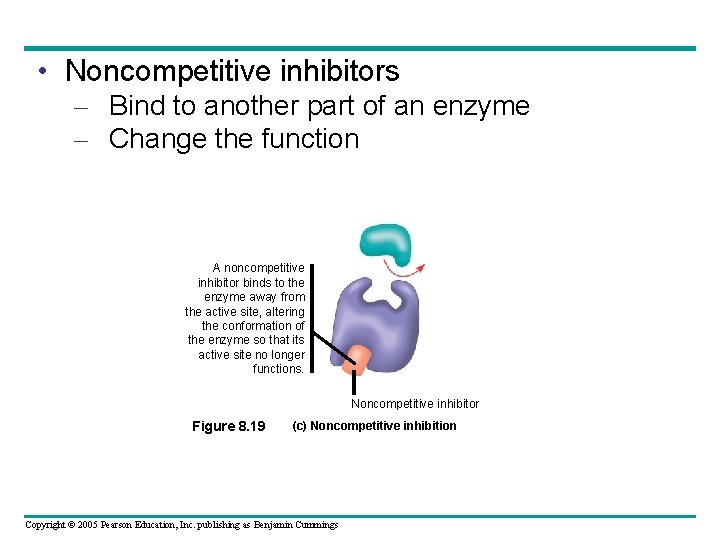

• Noncompetitive inhibitors – Bind to another part of an enzyme – Change the function A noncompetitive inhibitor binds to the enzyme away from the active site, altering the conformation of the enzyme so that its active site no longer functions. Noncompetitive inhibitor Figure 8. 19 (c) Noncompetitive inhibition Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

Regulation of enzyme activity: • A cell’s metabolic pathways: – Must be tightly regulated • Regulation of enzyme activity: – Helps control metabolism Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

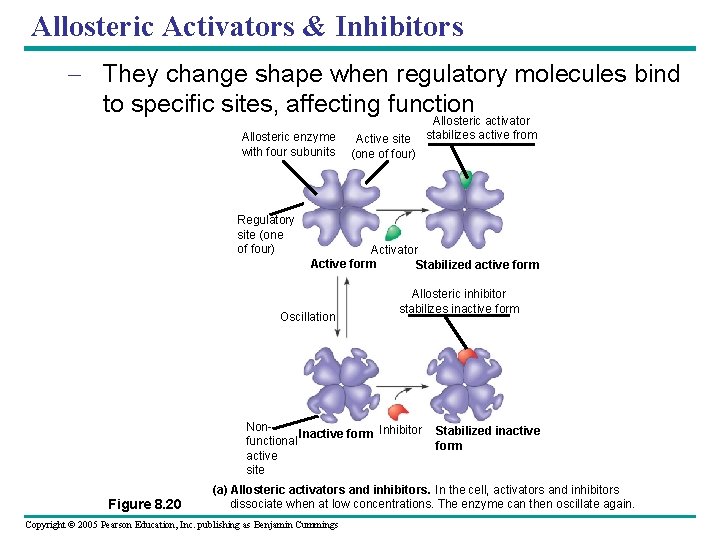

Allosteric Regulation of Enzymes • Allosteric regulation – Binding of a regulatory molecule at one site affecting the function at another site – Binding affect shape Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

Allosteric Activators & Inhibitors – They change shape when regulatory molecules bind to specific sites, affecting function Allosteric enzyme with four subunits Regulatory site (one of four) Active site (one of four) Activator Active form Stabilized active form Oscillation Allosteric inhibitor stabilizes inactive form Non. Inactive form Inhibitor functional active site Figure 8. 20 Allosteric activator stabilizes active from Stabilized inactive form (a) Allosteric activators and inhibitors. In the cell, activators and inhibitors dissociate when at low concentrations. The enzyme can then oscillate again. Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

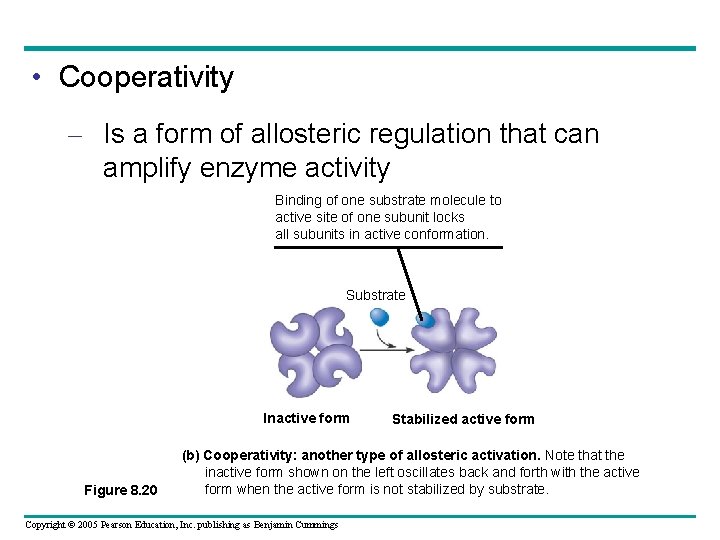

• Cooperativity – Is a form of allosteric regulation that can amplify enzyme activity Binding of one substrate molecule to active site of one subunit locks all subunits in active conformation. Substrate Inactive form Figure 8. 20 Stabilized active form (b) Cooperativity: another type of allosteric activation. Note that the inactive form shown on the left oscillates back and forth with the active form when the active form is not stabilized by substrate. Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

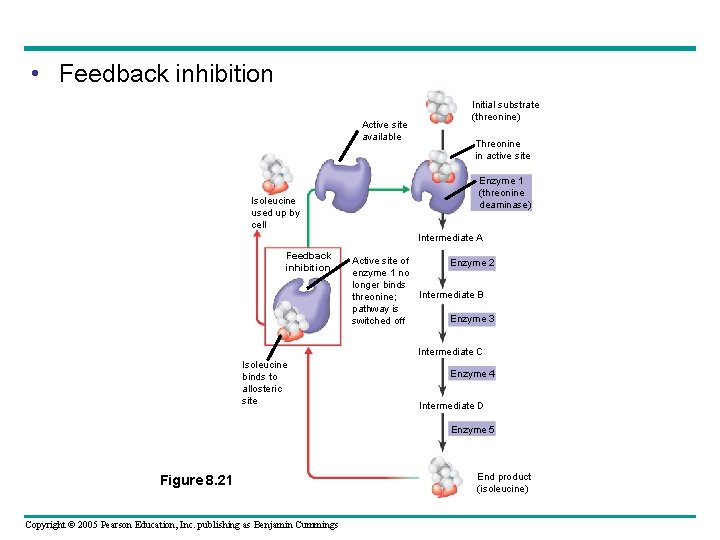

Feedback Inhibition • In feedback inhibition – The end product of a metabolic pathway shuts down the pathway Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

• Feedback inhibition Active site available Isoleucine used up by cell Initial substrate (threonine) Threonine in active site Enzyme 1 (threonine deaminase) Intermediate A Feedback inhibition Active site of Enzyme 2 enzyme 1 no longer binds Intermediate B threonine; pathway is Enzyme 3 switched off Intermediate C Isoleucine binds to allosteric site Enzyme 4 Intermediate D Enzyme 5 Figure 8. 21 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings End product (isoleucine)

- Slides: 45