Chapter 8 Mechanical Failure ISSUES TO ADDRESS How

- Slides: 67

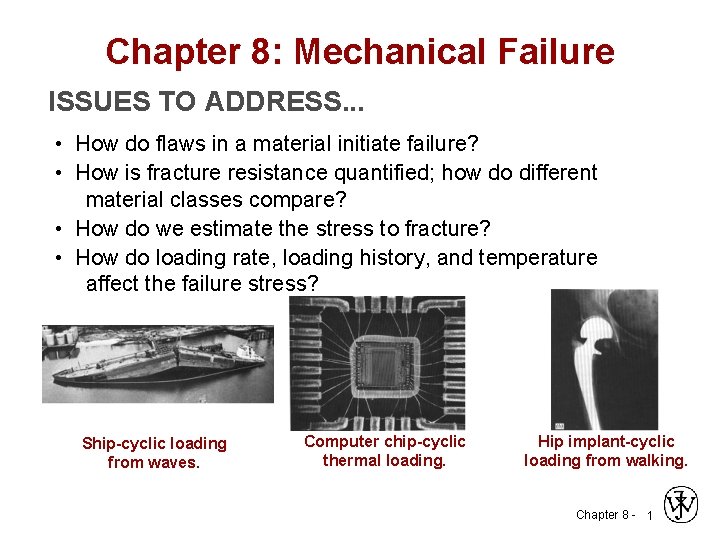

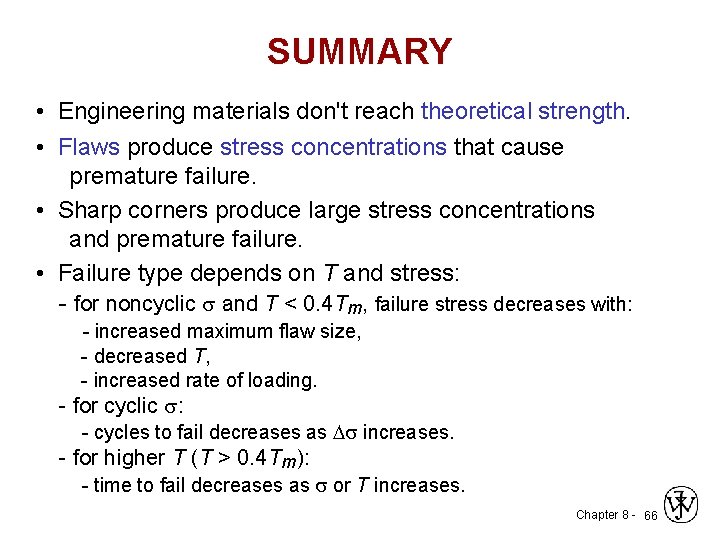

Chapter 8: Mechanical Failure ISSUES TO ADDRESS. . . • How do flaws in a material initiate failure? • How is fracture resistance quantified; how do different material classes compare? • How do we estimate the stress to fracture? • How do loading rate, loading history, and temperature affect the failure stress? Ship-cyclic loading from waves. Computer chip-cyclic thermal loading. Hip implant-cyclic loading from walking. Chapter 8 - 1

Failure mechanisms 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Fracture Fatigue Creep Corrosion Buckling Melting Thermal shock Wear Chapter 8 - 2

1. Fracture mechanisms Fracture is the separation of a body into two or more pieces in response to an imposed stress that is static (i. e. , constant or slowly changing with time) and at temperatures that are low relative to the melting temperature of the material. The applied stress may be tensile, compressive, shear, or torsional; • Ductile fracture – Occurs with plastic deformation • Brittle fracture – Little or no plastic deformation – Suddenly and catastrophic • Any fracture process involves two steps—crack formation and propagation—in response to an imposed stress Chapter 8 - 3

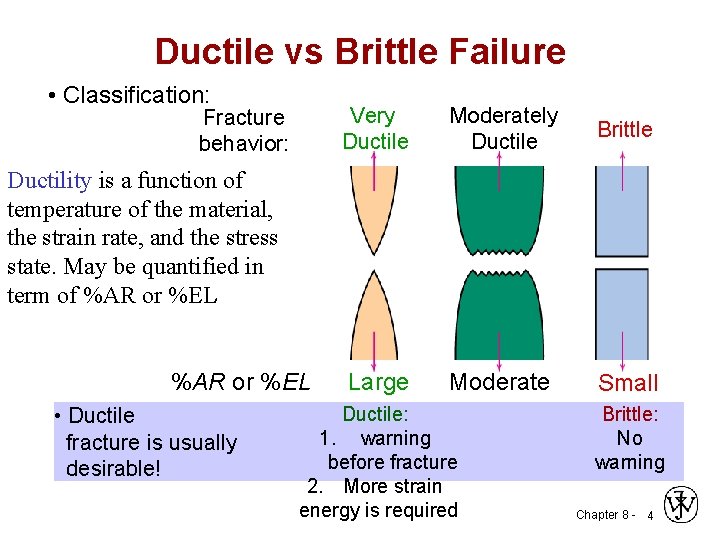

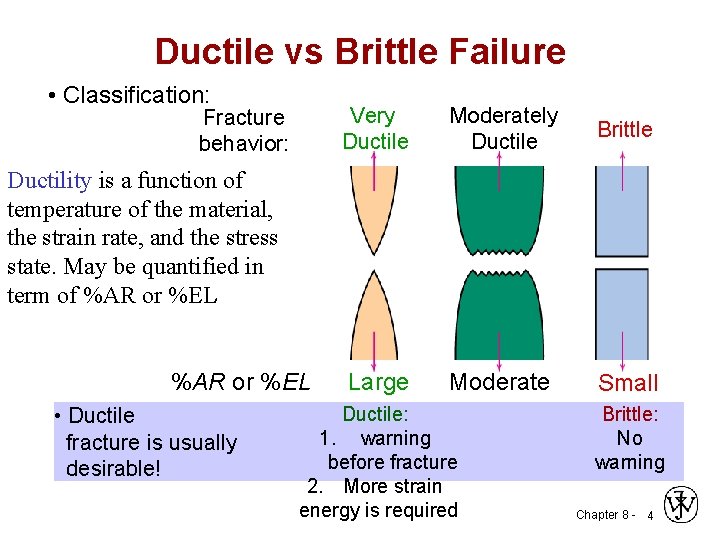

Ductile vs Brittle Failure • Classification: Fracture behavior: Very Ductile Moderately Ductile Brittle Large Moderate Small Ductility is a function of temperature of the material, the strain rate, and the stress state. May be quantified in term of %AR or %EL • Ductile fracture is usually desirable! Ductile: 1. warning before fracture 2. More strain energy is required Brittle: No warning Chapter 8 - 4

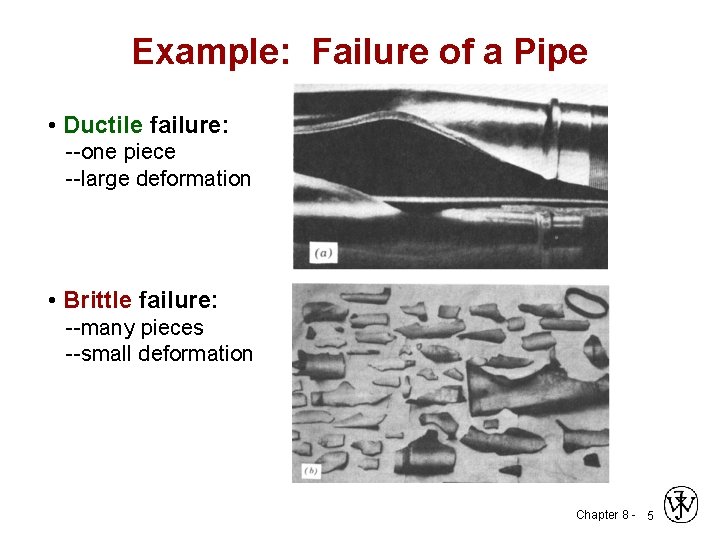

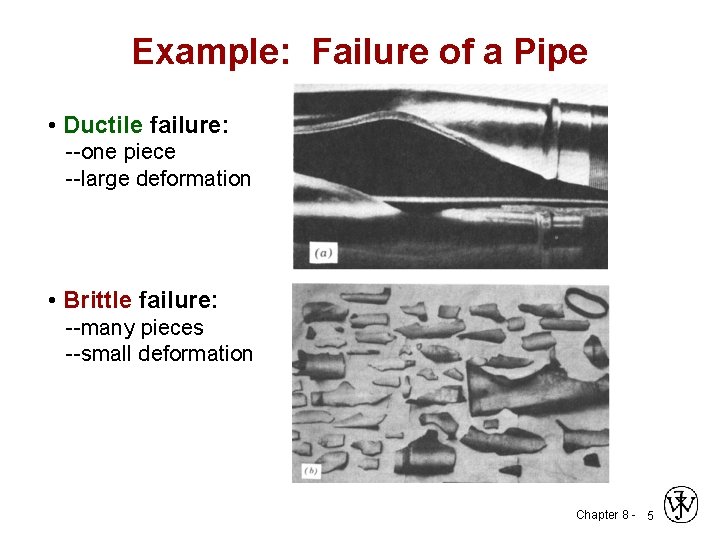

Example: Failure of a Pipe • Ductile failure: --one piece --large deformation • Brittle failure: --many pieces --small deformation Chapter 8 - 5

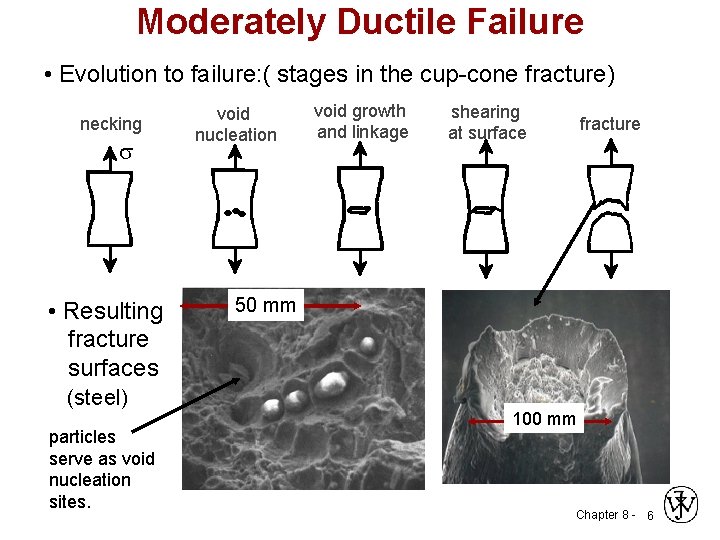

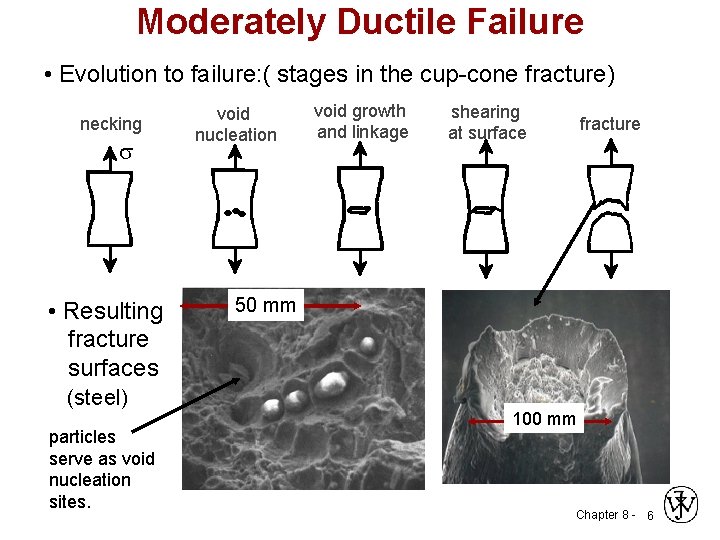

Moderately Ductile Failure • Evolution to failure: ( stages in the cup-cone fracture) necking s • Resulting fracture surfaces (steel) particles serve as void nucleation sites. void nucleation void growth and linkage shearing at surface fracture 50 50 mm mm 100 mm Chapter 8 - 6

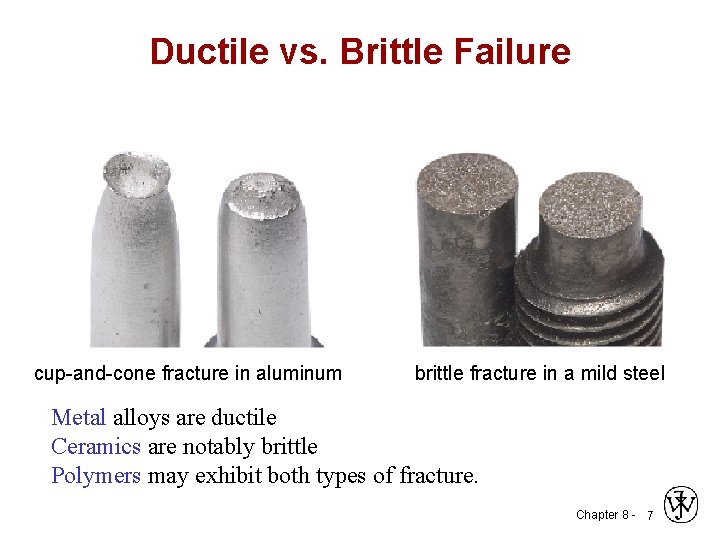

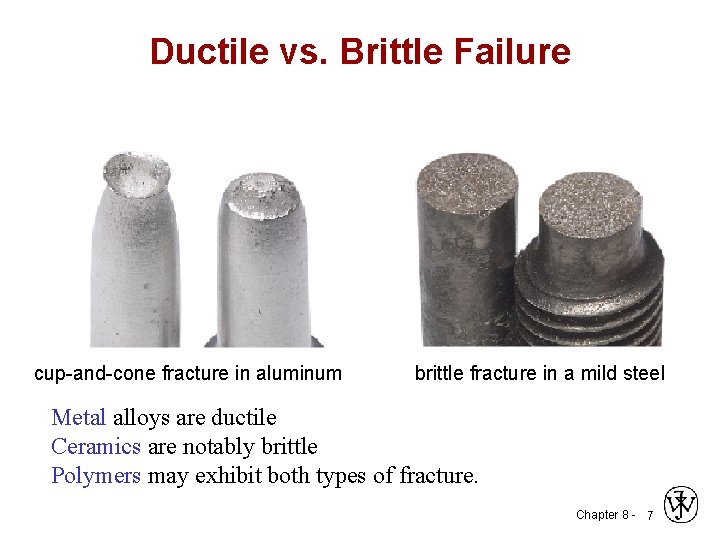

Ductile vs. Brittle Failure cup-and-cone fracture in aluminum brittle fracture in a mild steel Metal alloys are ductile Ceramics are notably brittle Polymers may exhibit both types of fracture. Chapter 8 - 7

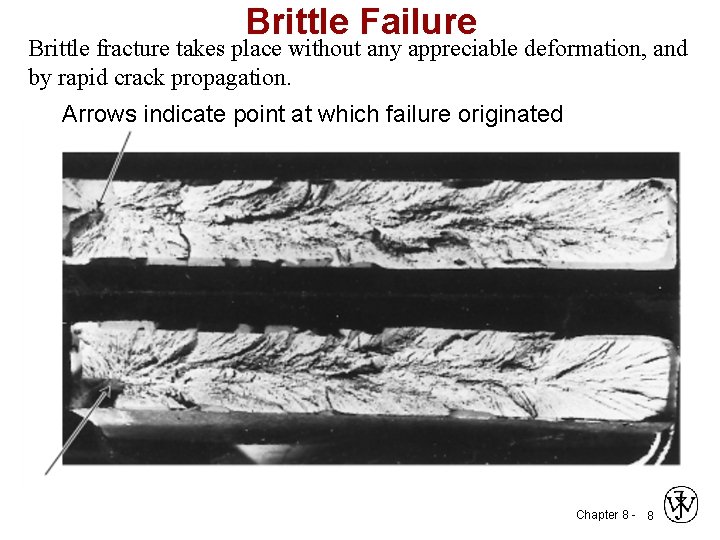

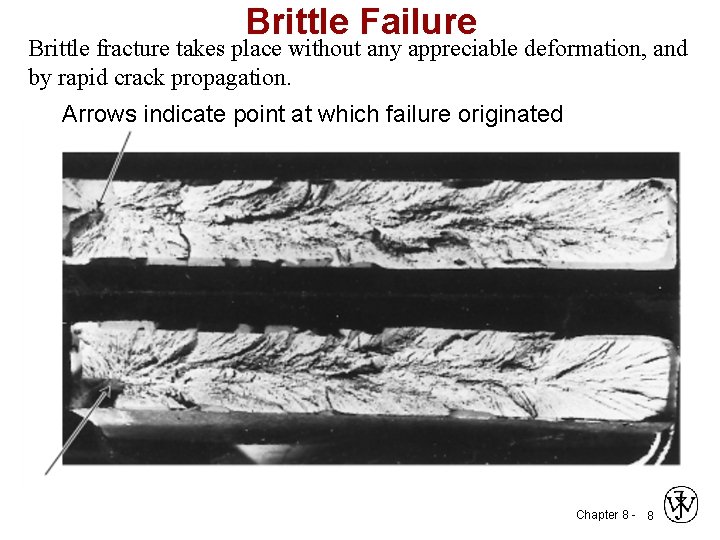

Brittle Failure Brittle fracture takes place without any appreciable deformation, and by rapid crack propagation. Arrows indicate point at which failure originated Chapter 8 - 8

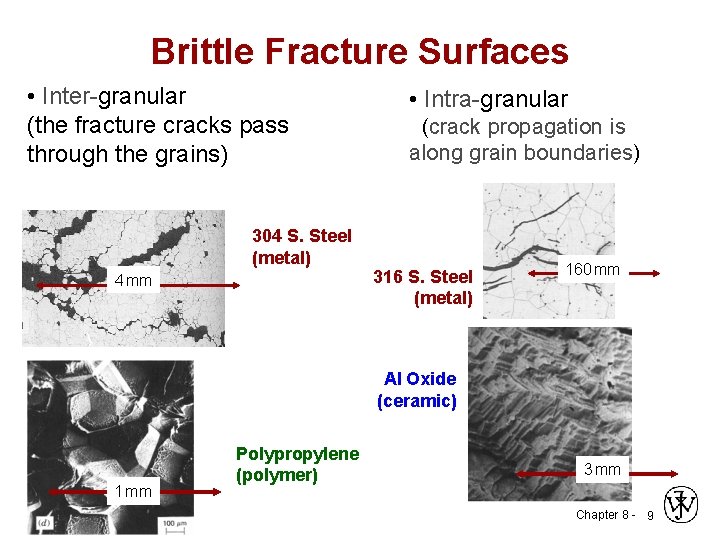

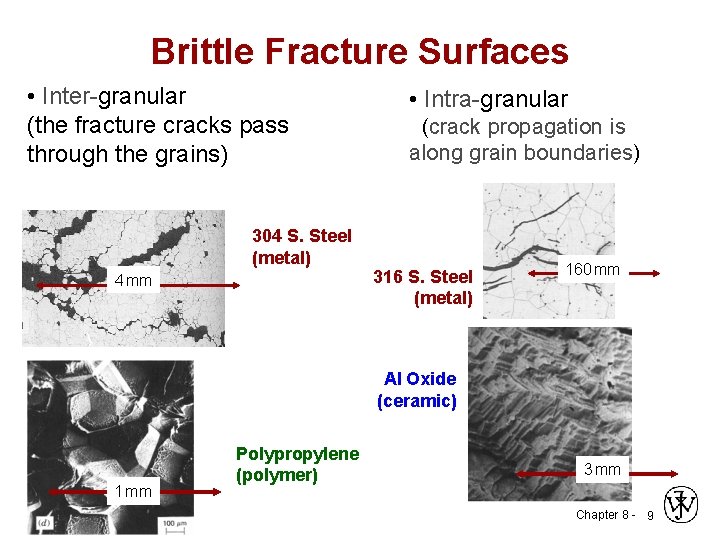

Brittle Fracture Surfaces • Inter-granular (the fracture cracks pass through the grains) 304 S. Steel (metal) 4 mm • Intra-granular (crack propagation is along grain boundaries) 316 S. Steel (metal) 160 mm Al Oxide (ceramic) 1 mm Polypropylene (polymer) 3 mm Chapter 8 - 9

Principles of fracture mechanics This subject allows quantification of the relationships between material properties, stress level, the presence of crackproducing flaws, and crack propagation mechanisms. 1. stress concentration 2. Fracture toughness 3. Design using fracture mechanics 4. Impact fracture testing Chapter 8 - 10

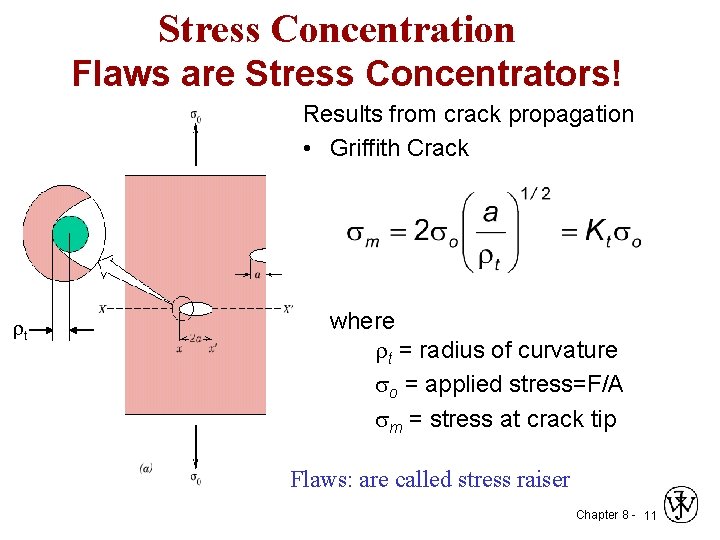

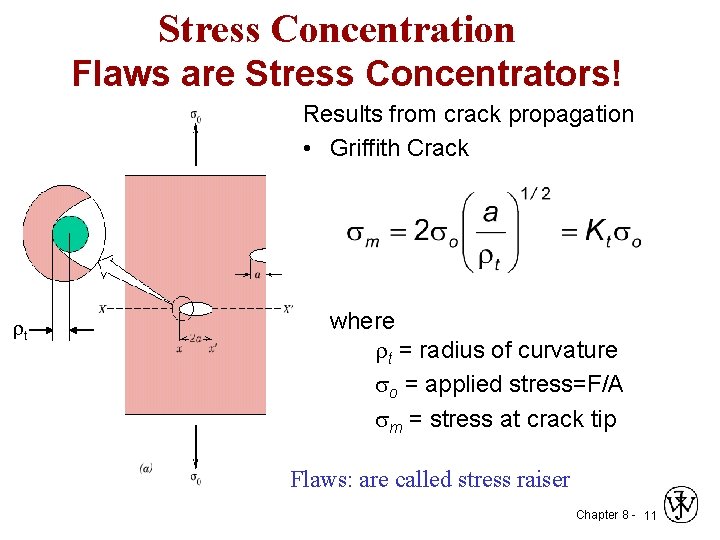

Stress Concentration Flaws are Stress Concentrators! Results from crack propagation • Griffith Crack t where t = radius of curvature so = applied stress=F/A sm = stress at crack tip Flaws: are called stress raiser Chapter 8 - 11

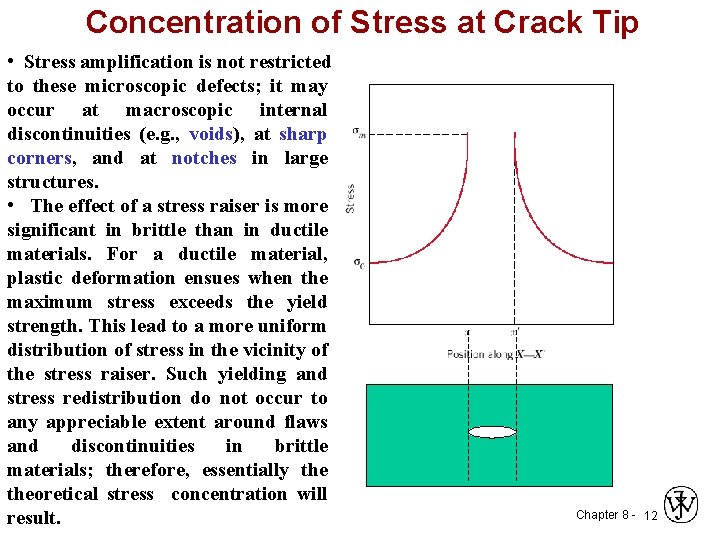

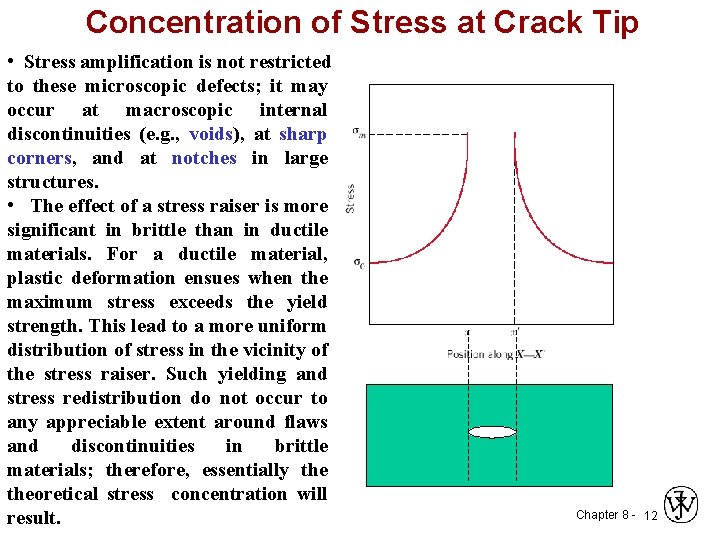

Concentration of Stress at Crack Tip • Stress amplification is not restricted to these microscopic defects; it may occur at macroscopic internal discontinuities (e. g. , voids), at sharp corners, and at notches in large structures. • The effect of a stress raiser is more significant in brittle than in ductile materials. For a ductile material, plastic deformation ensues when the maximum stress exceeds the yield strength. This lead to a more uniform distribution of stress in the vicinity of the stress raiser. Such yielding and stress redistribution do not occur to any appreciable extent around flaws and discontinuities in brittle materials; therefore, essentially theoretical stress concentration will result. Chapter 8 - 12

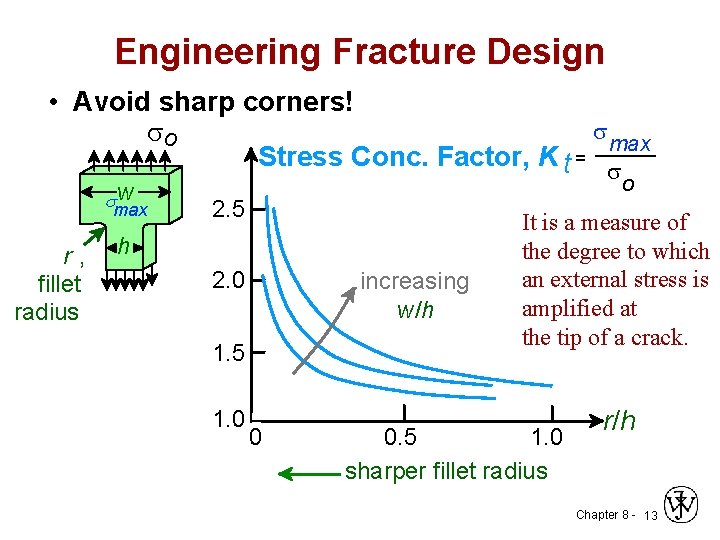

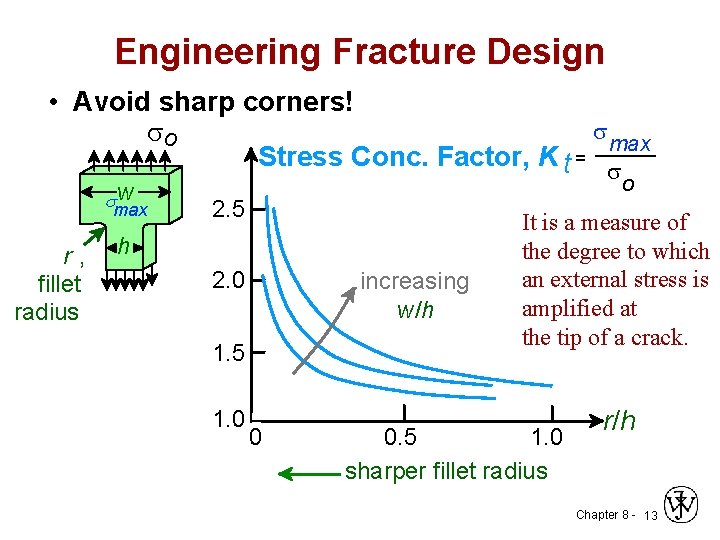

Engineering Fracture Design • Avoid sharp corners! s so max Stress Conc. Factor, K t = s sw max r, fillet radius o 2. 5 h 2. 0 increasing w/h 1. 5 1. 0 0 It is a measure of the degree to which an external stress is amplified at the tip of a crack. 0. 5 1. 0 sharper fillet radius r/h Chapter 8 - 13

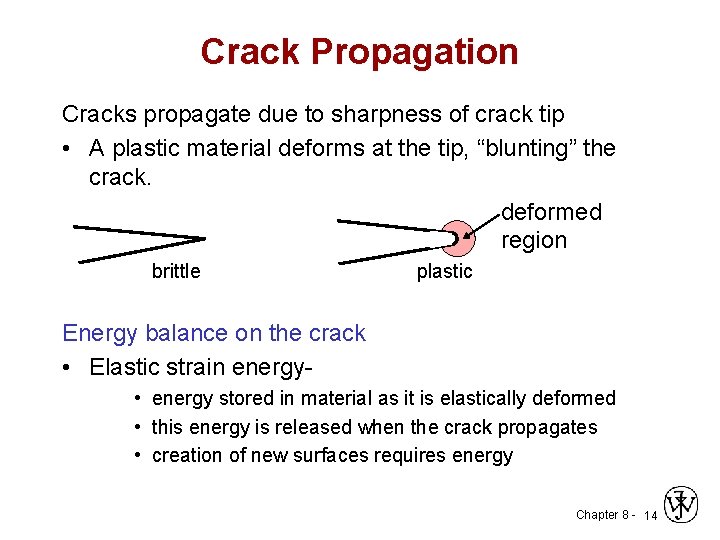

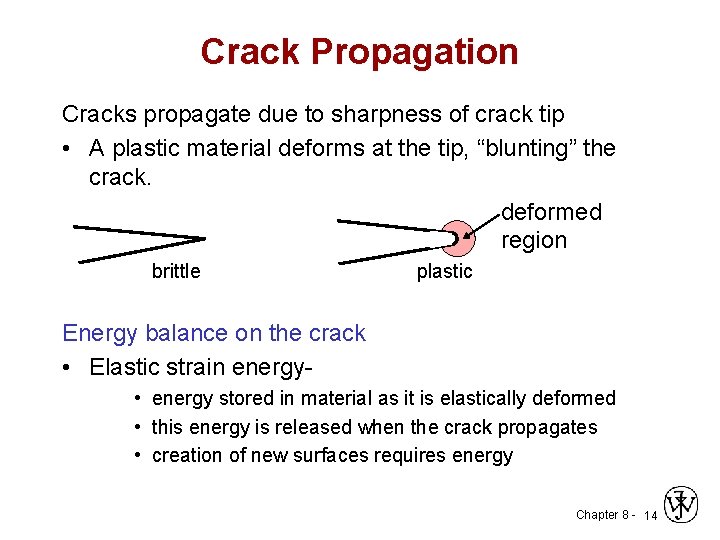

Crack Propagation Cracks propagate due to sharpness of crack tip • A plastic material deforms at the tip, “blunting” the crack. deformed region brittle plastic Energy balance on the crack • Elastic strain energy • energy stored in material as it is elastically deformed • this energy is released when the crack propagates • creation of new surfaces requires energy Chapter 8 - 14

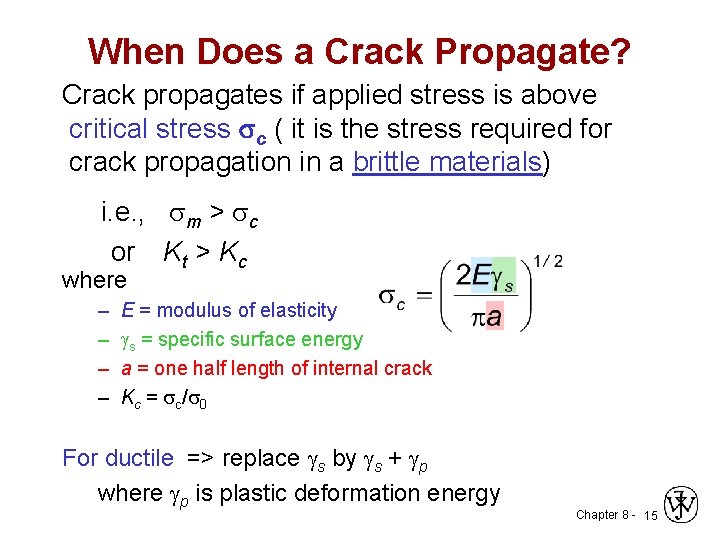

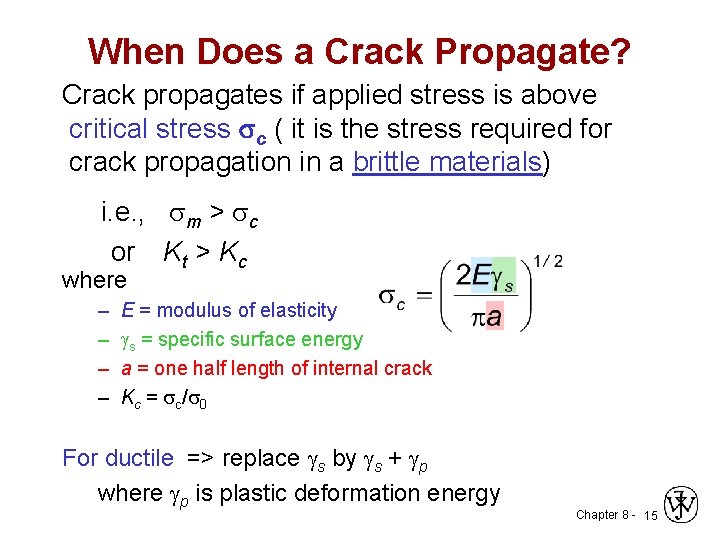

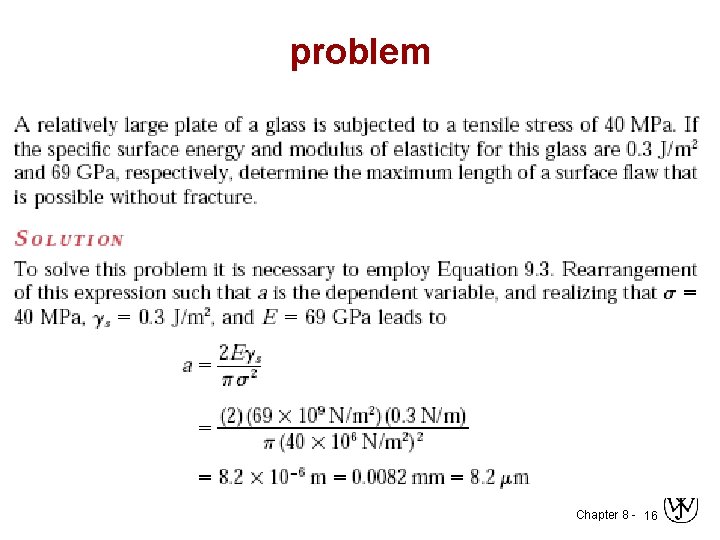

When Does a Crack Propagate? Crack propagates if applied stress is above critical stress c ( it is the stress required for crack propagation in a brittle materials) i. e. , sm > sc or Kt > Kc where – – E = modulus of elasticity s = specific surface energy a = one half length of internal crack Kc = sc/s 0 For ductile => replace s by s + p where p is plastic deformation energy Chapter 8 - 15

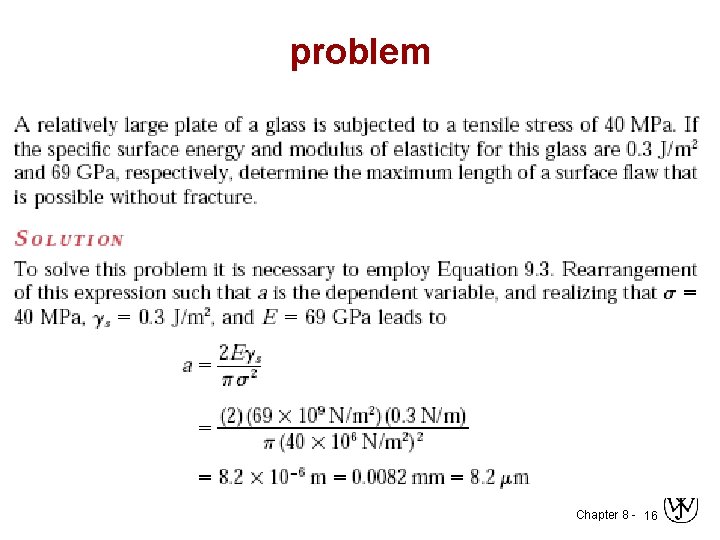

problem Chapter 8 - 16

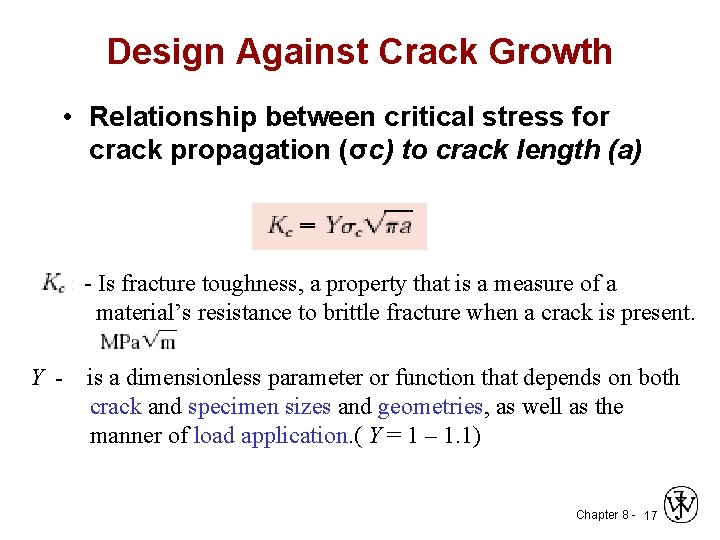

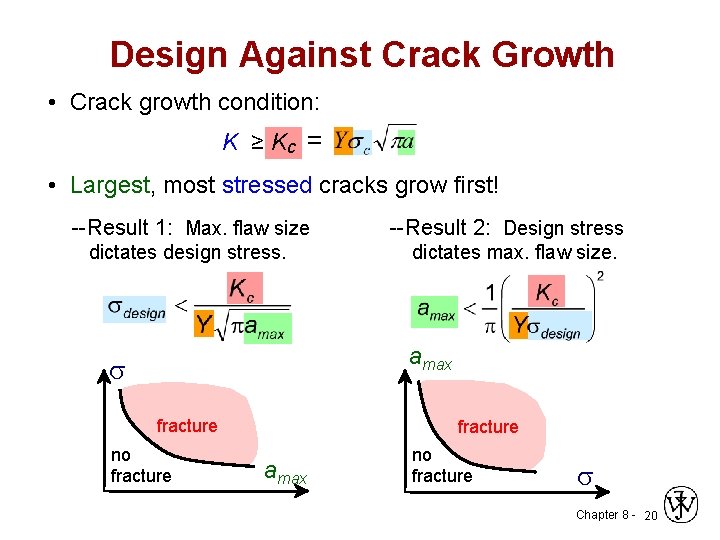

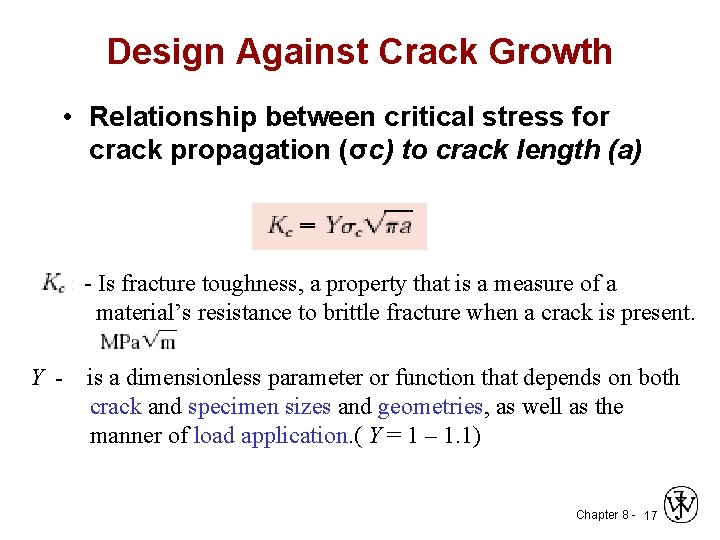

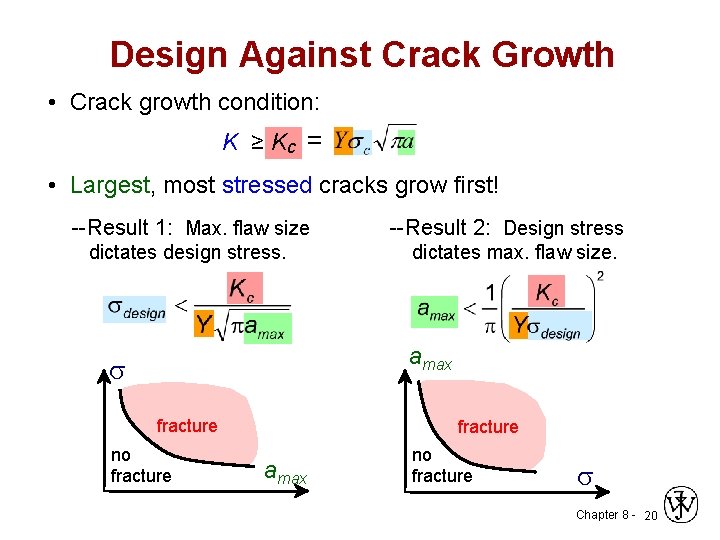

Design Against Crack Growth • Relationship between critical stress for crack propagation (σc) to crack length (a) - Is fracture toughness, a property that is a measure of a material’s resistance to brittle fracture when a crack is present. Y - is a dimensionless parameter or function that depends on both crack and specimen sizes and geometries, as well as the manner of load application. ( Y = 1 – 1. 1) Chapter 8 - 17

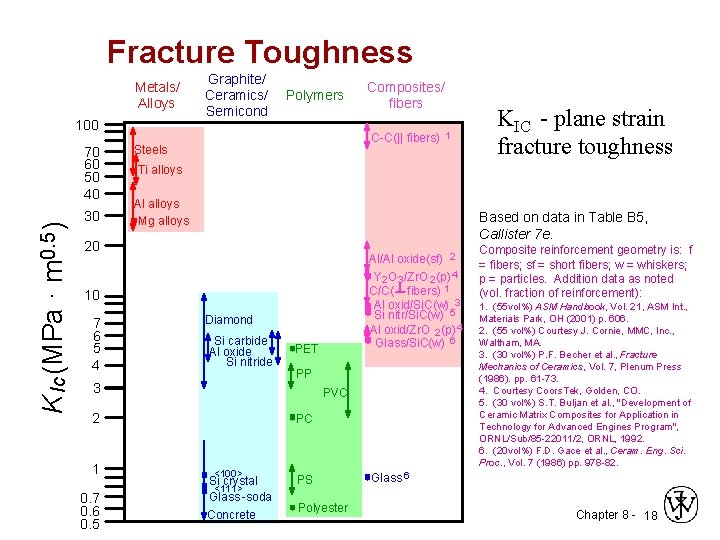

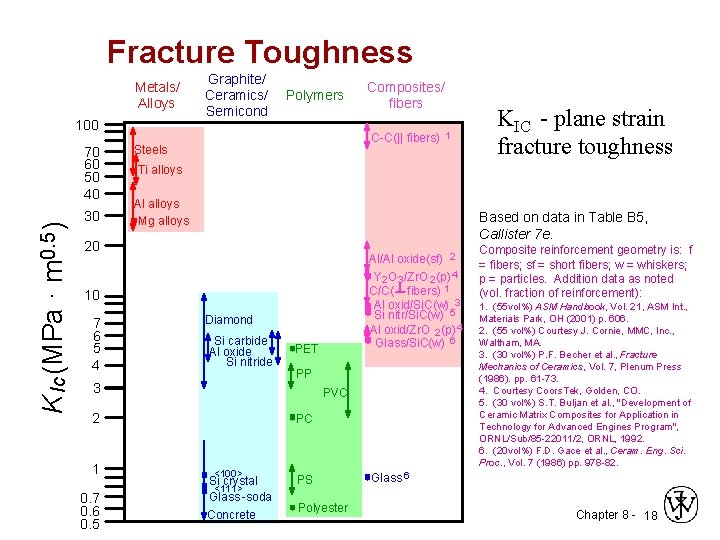

Fracture Toughness Metals/ Alloys 100 K Ic (MPa · m 0. 5 ) 70 60 50 40 30 Graphite/ Ceramics/ Semicond Polymers C-C(|| fibers) Steels Al alloys Mg alloys Al/Al oxide(sf) 2 Y 2 O 3 /Zr. O 2 (p) 4 C/C( fibers) 1 Al oxid/Si. C(w) 3 Si nitr/Si. C(w) 5 Al oxid/Zr. O 2 (p) 4 Glass/Si. C(w) 6 Diamond Si carbide Al oxide Si nitride 3 PET PP PVC 2 0. 7 0. 6 0. 5 KIC - plane strain fracture toughness Based on data in Table B 5, Callister 7 e. 10 1 1 Ti alloys 20 7 6 5 4 Composites/ fibers PC <100> Si crystal <111> Glass -soda Concrete PS Polyester Composite reinforcement geometry is: f = fibers; sf = short fibers; w = whiskers; p = particles. Addition data as noted (vol. fraction of reinforcement): 1. (55 vol%) ASM Handbook, Vol. 21, ASM Int. , Materials Park, OH (2001) p. 606. 2. (55 vol%) Courtesy J. Cornie, MMC, Inc. , Waltham, MA. 3. (30 vol%) P. F. Becher et al. , Fracture Mechanics of Ceramics, Vol. 7, Plenum Press (1986). pp. 61 -73. 4. Courtesy Coors. Tek, Golden, CO. 5. (30 vol%) S. T. Buljan et al. , "Development of Ceramic Matrix Composites for Application in Technology for Advanced Engines Program", ORNL/Sub/85 -22011/2, ORNL, 1992. 6. (20 vol%) F. D. Gace et al. , Ceram. Eng. Sci. Proc. , Vol. 7 (1986) pp. 978 -82. Glass 6 Chapter 8 - 18

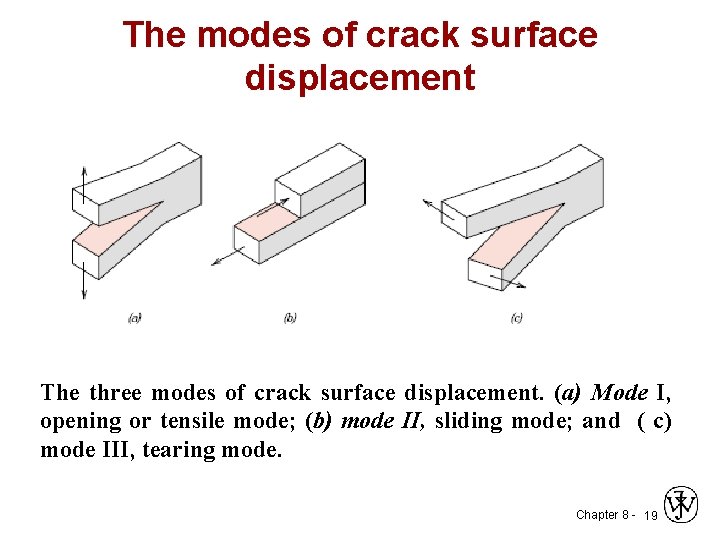

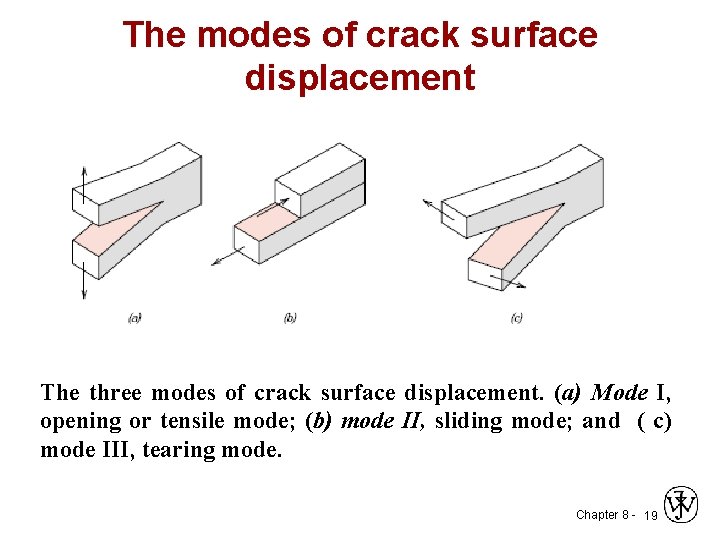

The modes of crack surface displacement The three modes of crack surface displacement. (a) Mode I, opening or tensile mode; (b) mode II, sliding mode; and ( c) mode III, tearing mode. Chapter 8 - 19

Design Against Crack Growth • Crack growth condition: K ≥ Kc = • Largest, most stressed cracks grow first! --Result 1: Max. flaw size dictates design stress. --Result 2: Design stress dictates max. flaw size. amax s fracture no fracture amax no fracture s Chapter 8 - 20

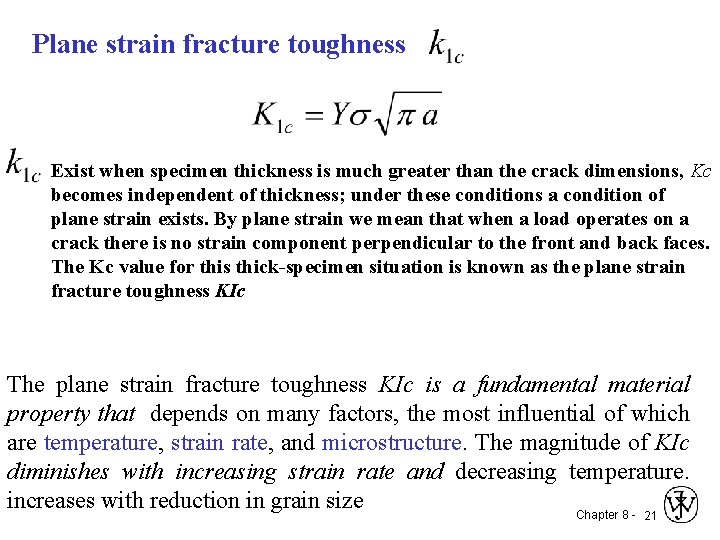

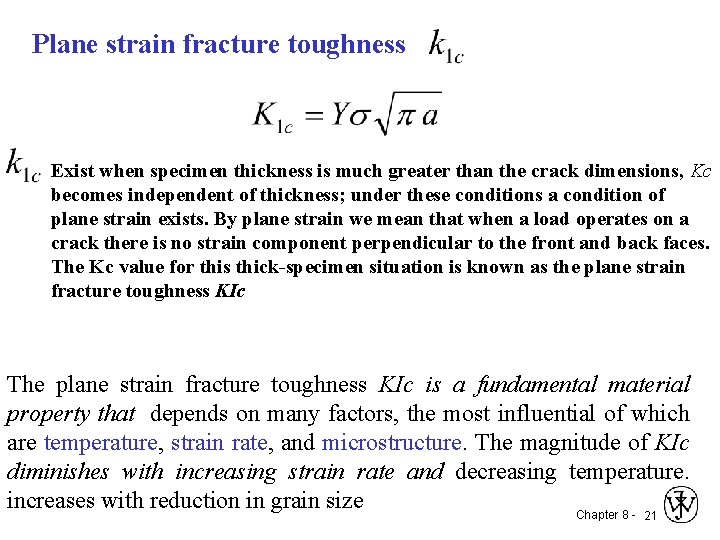

Plane strain fracture toughness Exist when specimen thickness is much greater than the crack dimensions, Kc becomes independent of thickness; under these conditions a condition of plane strain exists. By plane strain we mean that when a load operates on a crack there is no strain component perpendicular to the front and back faces. The Kc value for this thick-specimen situation is known as the plane strain fracture toughness KIc The plane strain fracture toughness KIc is a fundamental material property that depends on many factors, the most influential of which are temperature, strain rate, and microstructure. The magnitude of KIc diminishes with increasing strain rate and decreasing temperature. increases with reduction in grain size Chapter 8 - 21

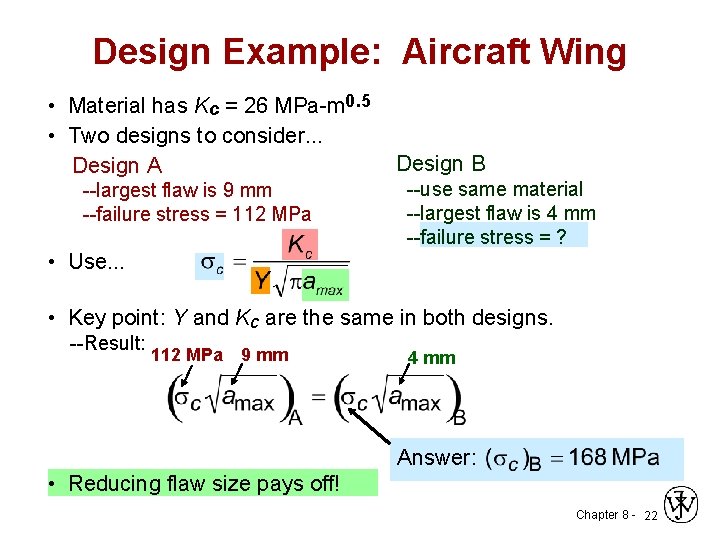

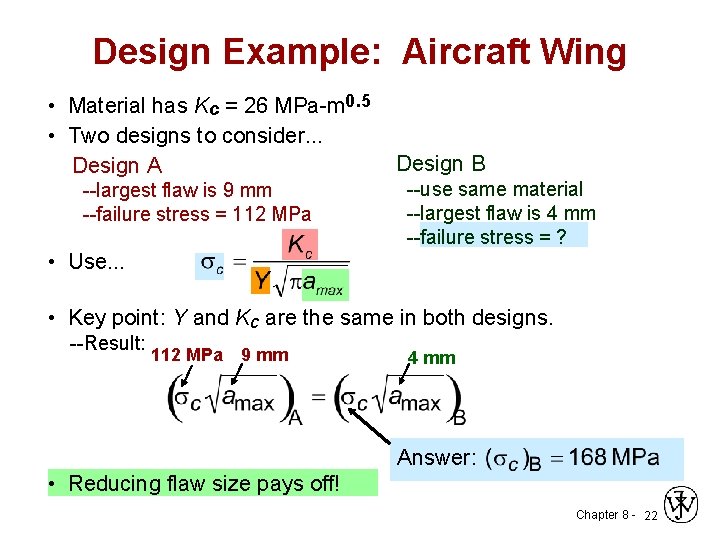

Design Example: Aircraft Wing • Material has Kc = 26 MPa-m 0. 5 • Two designs to consider. . . Design A --largest flaw is 9 mm --failure stress = 112 MPa Design B --use same material --largest flaw is 4 mm --failure stress = ? • Use. . . • Key point: Y and Kc are the same in both designs. --Result: 112 MPa 9 mm 4 mm Answer: • Reducing flaw size pays off! Chapter 8 - 22

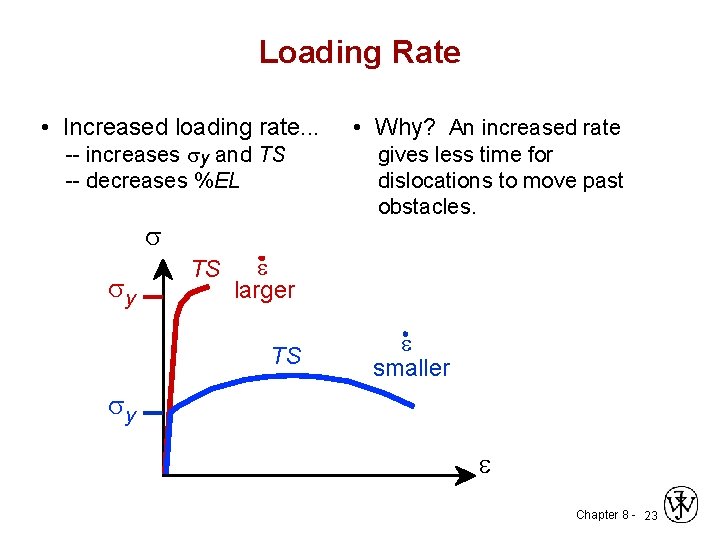

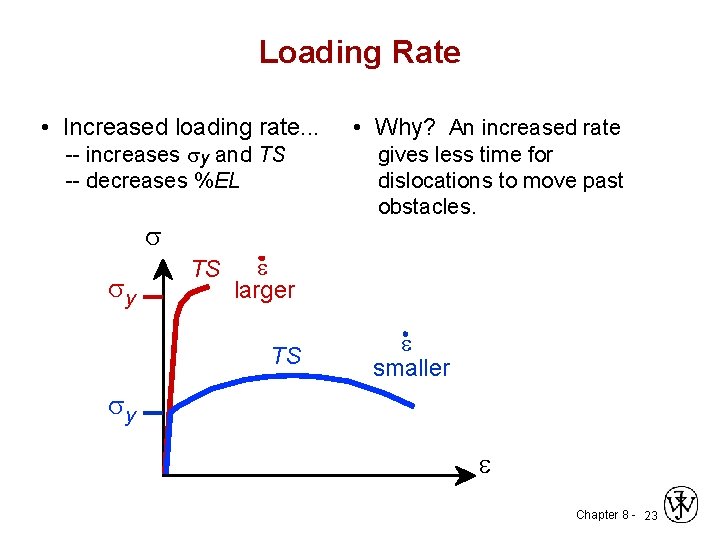

Loading Rate • Increased loading rate. . . -- increases sy and TS -- decreases %EL s sy TS • Why? An increased rate gives less time for dislocations to move past obstacles. e larger TS e smaller sy e Chapter 8 - 23

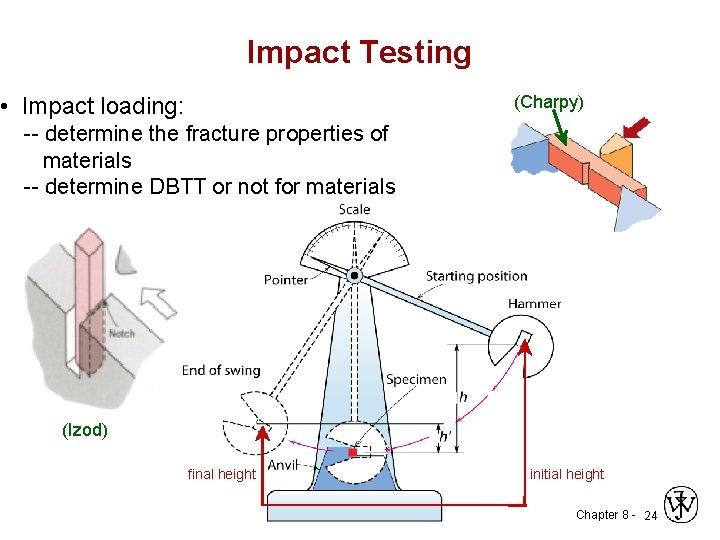

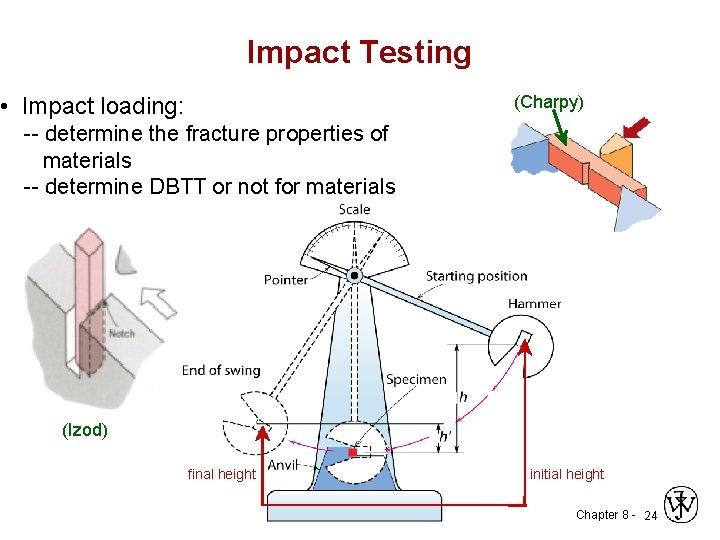

Impact Testing (Charpy) • Impact loading: -- determine the fracture properties of materials -- determine DBTT or not for materials (Izod) final height initial height Chapter 8 - 24

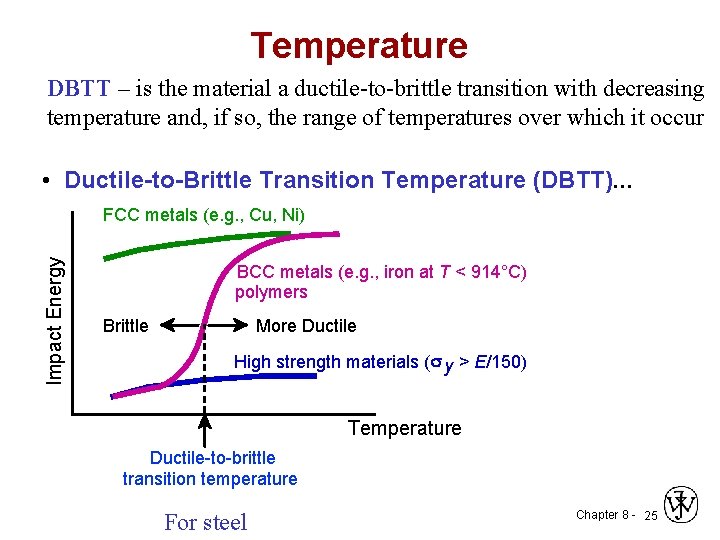

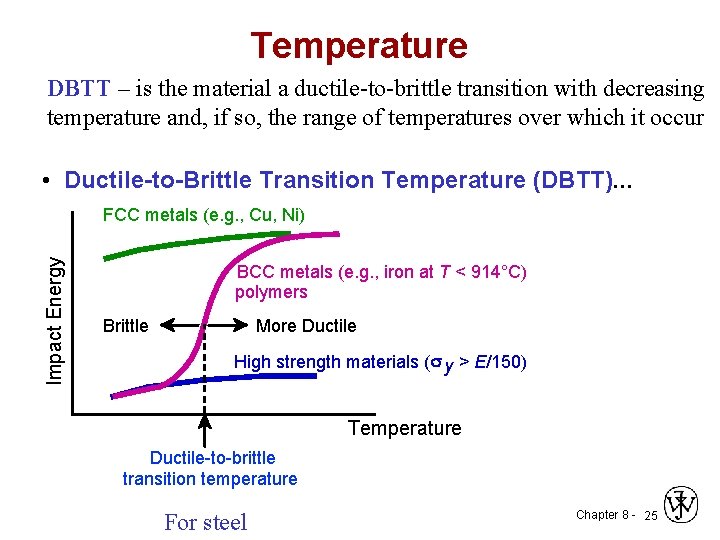

Temperature DBTT – is the material a ductile-to-brittle transition with decreasing temperature and, if so, the range of temperatures over which it occur • Ductile-to-Brittle Transition Temperature (DBTT). . . Impact Energy FCC metals (e. g. , Cu, Ni) BCC metals (e. g. , iron at T < 914°C) polymers Brittle More Ductile High strength materials ( y > E/150) Temperature Ductile-to-brittle transition temperature For steel Chapter 8 - 25

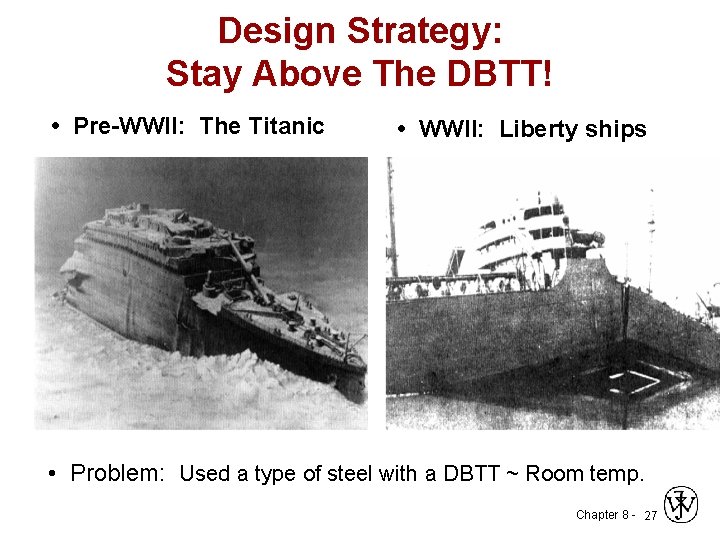

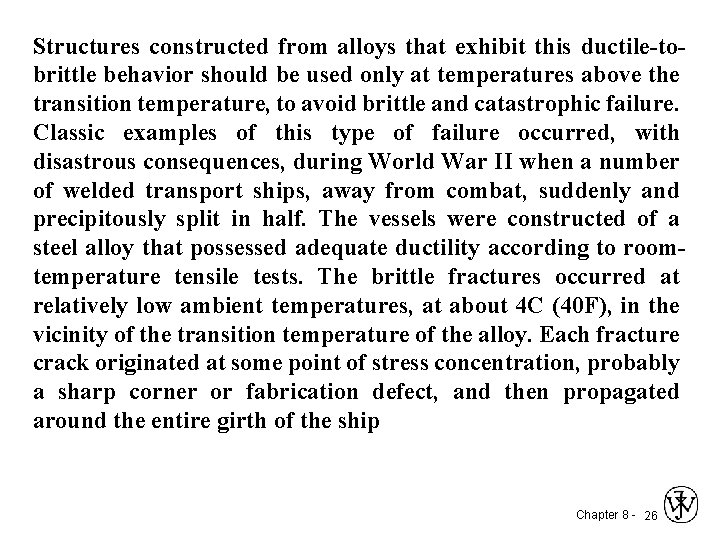

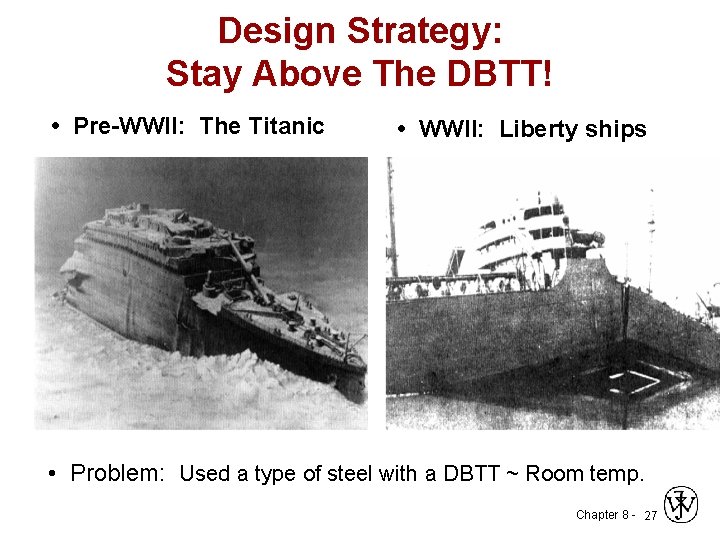

Structures constructed from alloys that exhibit this ductile-tobrittle behavior should be used only at temperatures above the transition temperature, to avoid brittle and catastrophic failure. Classic examples of this type of failure occurred, with disastrous consequences, during World War II when a number of welded transport ships, away from combat, suddenly and precipitously split in half. The vessels were constructed of a steel alloy that possessed adequate ductility according to roomtemperature tensile tests. The brittle fractures occurred at relatively low ambient temperatures, at about 4 C (40 F), in the vicinity of the transition temperature of the alloy. Each fracture crack originated at some point of stress concentration, probably a sharp corner or fabrication defect, and then propagated around the entire girth of the ship Chapter 8 - 26

Design Strategy: Stay Above The DBTT! • Pre-WWII: The Titanic • WWII: Liberty ships • Problem: Used a type of steel with a DBTT ~ Room temp. Chapter 8 - 27

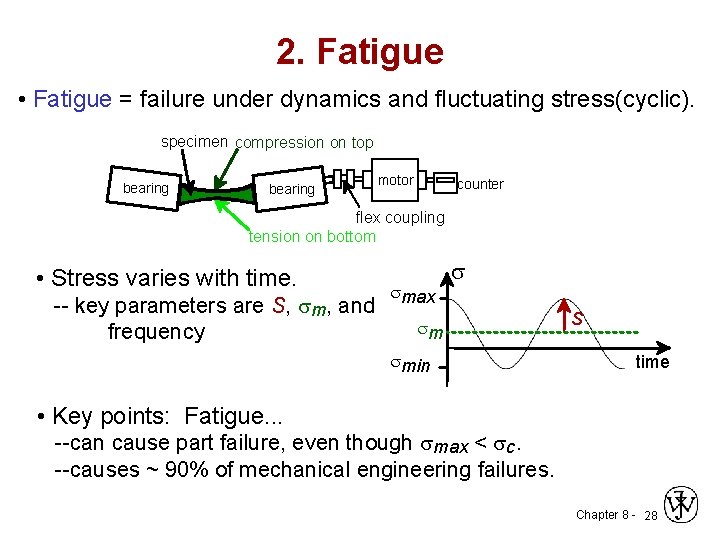

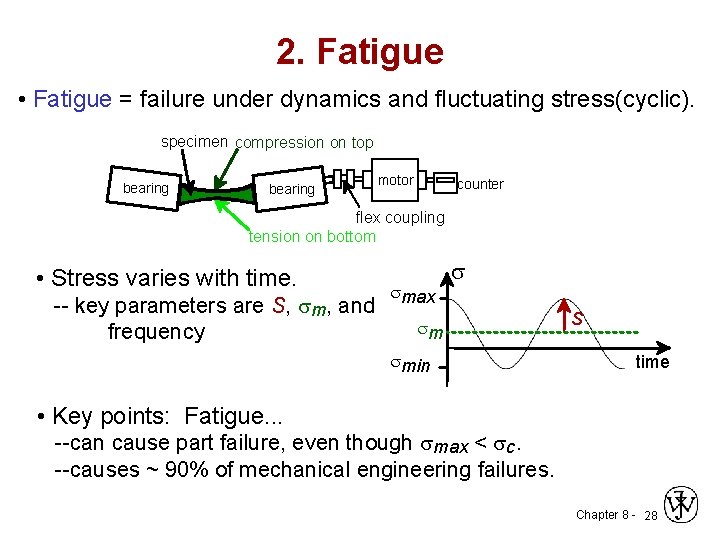

2. Fatigue • Fatigue = failure under dynamics and fluctuating stress(cyclic). specimen compression on top bearing motor counter flex coupling tension on bottom • Stress varies with time. -- key parameters are S, sm, and frequency smax s sm smin S time • Key points: Fatigue. . . --can cause part failure, even though smax < sc. --causes ~ 90% of mechanical engineering failures. Chapter 8 - 28

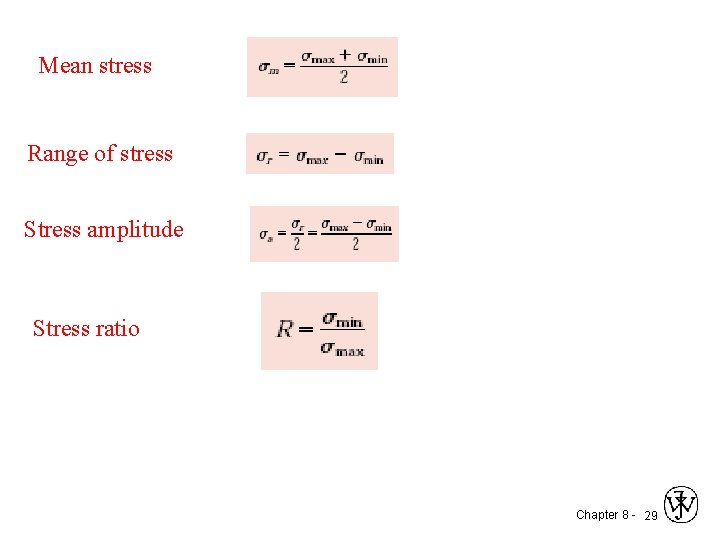

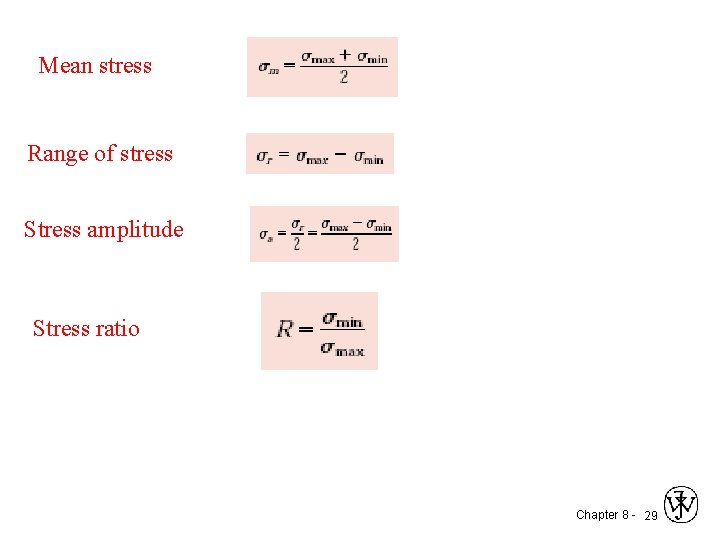

Mean stress Range of stress Stress amplitude Stress ratio Chapter 8 - 29

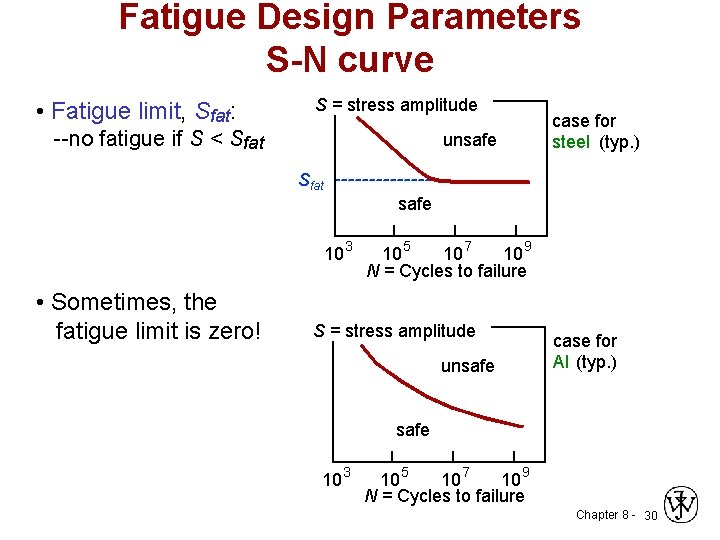

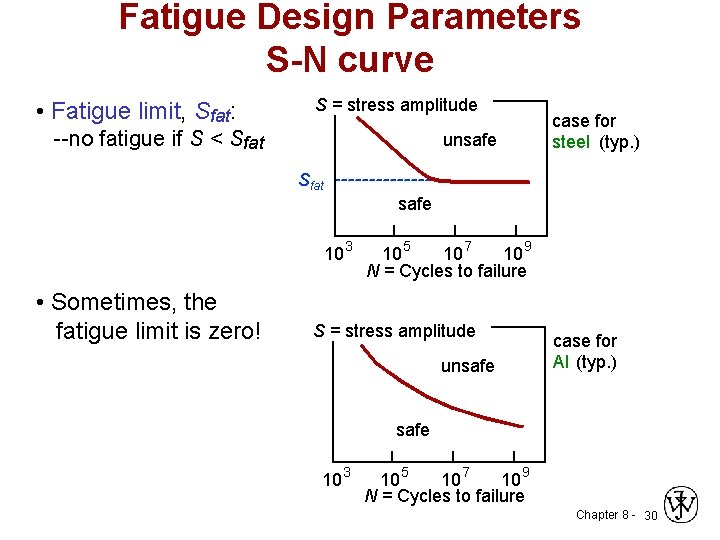

Fatigue Design Parameters S-N curve • Fatigue limit, Sfat: S = stress amplitude --no fatigue if S < Sfat unsafe case for steel (typ. ) Sfat safe 10 3 • Sometimes, the fatigue limit is zero! 10 5 10 7 10 9 N = Cycles to failure S = stress amplitude unsafe case for Al (typ. ) safe 10 3 10 5 10 7 10 9 N = Cycles to failure Chapter 8 - 30

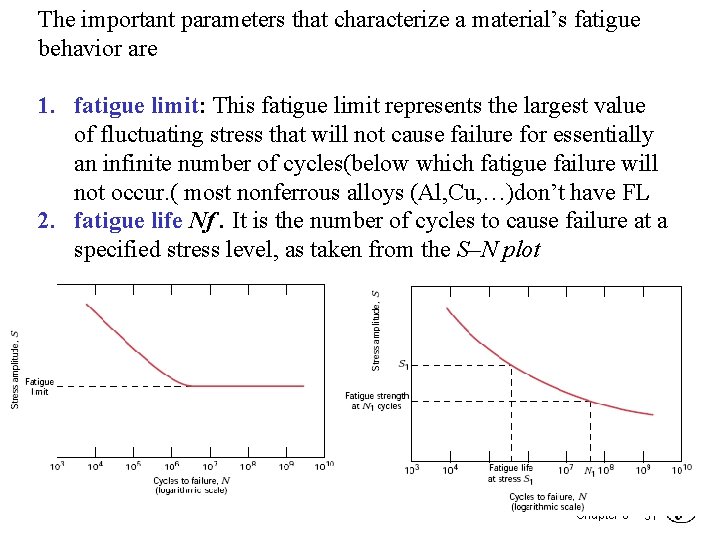

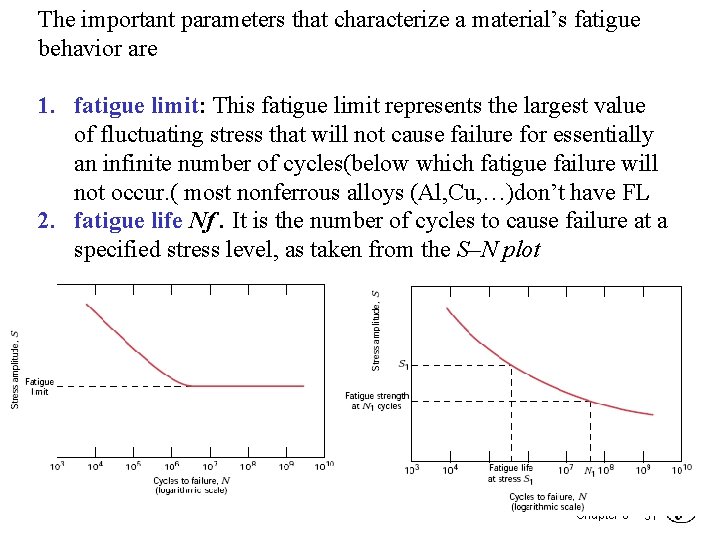

The important parameters that characterize a material’s fatigue behavior are 1. fatigue limit: This fatigue limit represents the largest value of fluctuating stress that will not cause failure for essentially an infinite number of cycles(below which fatigue failure will not occur. ( most nonferrous alloys (Al, Cu, …)don’t have FL 2. fatigue life Nf. It is the number of cycles to cause failure at a specified stress level, as taken from the S–N plot Chapter 8 - 31

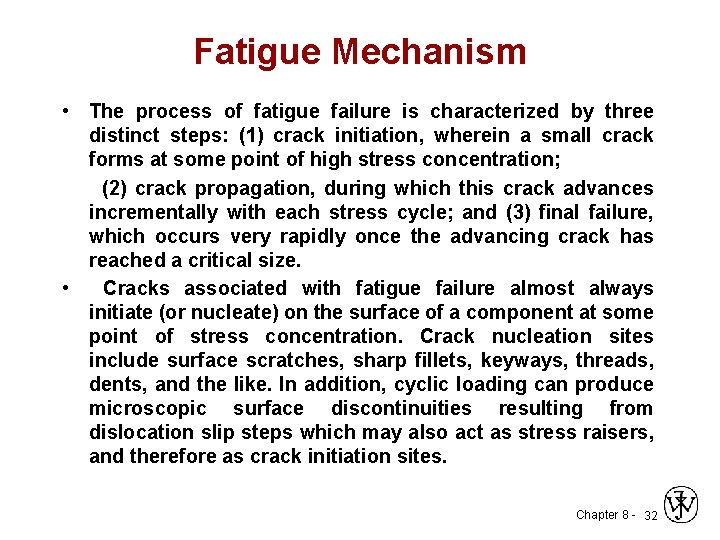

Fatigue Mechanism • The process of fatigue failure is characterized by three distinct steps: (1) crack initiation, wherein a small crack forms at some point of high stress concentration; (2) crack propagation, during which this crack advances incrementally with each stress cycle; and (3) final failure, which occurs very rapidly once the advancing crack has reached a critical size. • Cracks associated with fatigue failure almost always initiate (or nucleate) on the surface of a component at some point of stress concentration. Crack nucleation sites include surface scratches, sharp fillets, keyways, threads, dents, and the like. In addition, cyclic loading can produce microscopic surface discontinuities resulting from dislocation slip steps which may also act as stress raisers, and therefore as crack initiation sites. Chapter 8 - 32

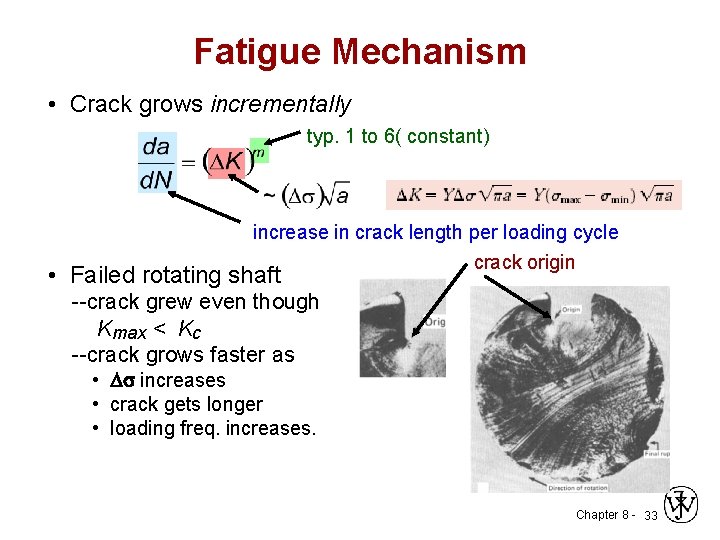

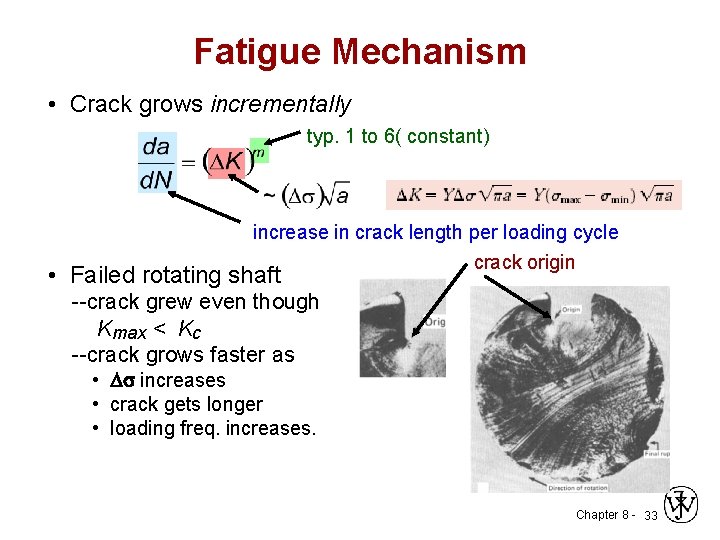

Fatigue Mechanism • Crack grows incrementally typ. 1 to 6( constant) increase in crack length per loading cycle crack origin • Failed rotating shaft --crack grew even though Kmax < Kc --crack grows faster as • D increases • crack gets longer • loading freq. increases. Chapter 8 - 33

Factors that affect fatigue life 1. Mean stress 2. Surface effects 3. Environmental effects Chapter 8 - 34

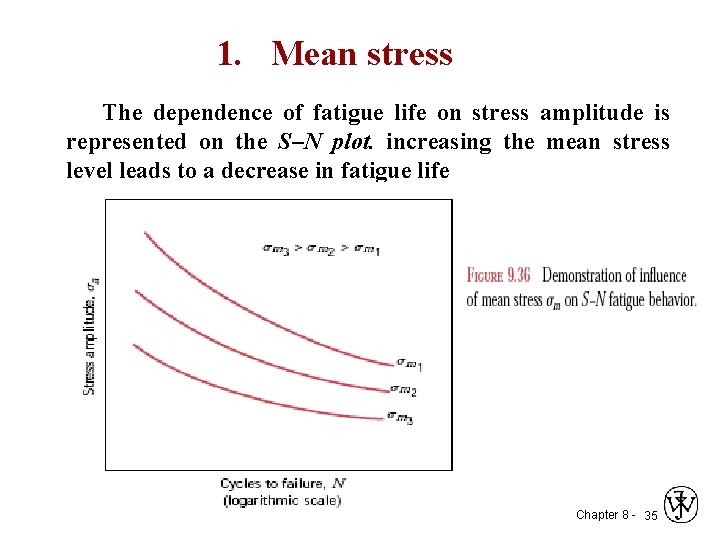

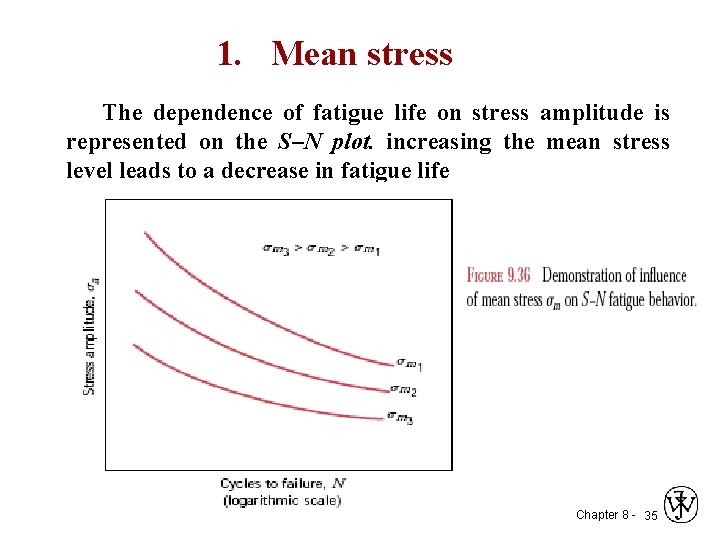

1. Mean stress The dependence of fatigue life on stress amplitude is represented on the S–N plot. increasing the mean stress level leads to a decrease in fatigue life Chapter 8 - 35

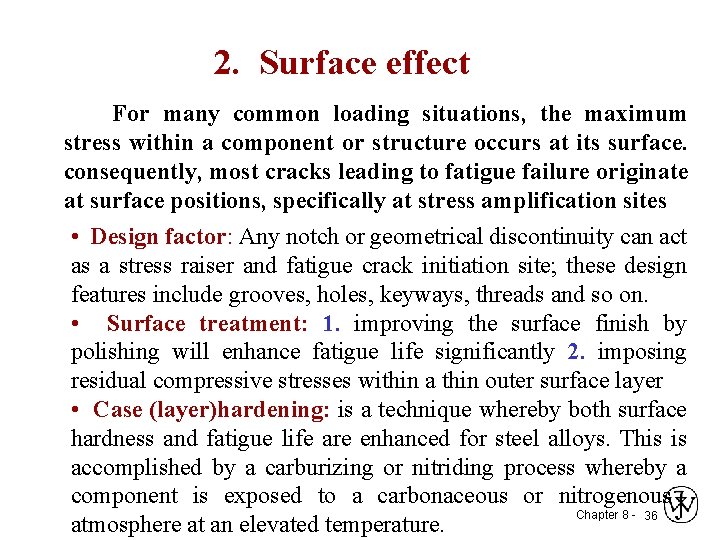

2. Surface effect For many common loading situations, the maximum stress within a component or structure occurs at its surface. consequently, most cracks leading to fatigue failure originate at surface positions, specifically at stress amplification sites • Design factor: Any notch or geometrical discontinuity can act as a stress raiser and fatigue crack initiation site; these design features include grooves, holes, keyways, threads and so on. • Surface treatment: 1. improving the surface finish by polishing will enhance fatigue life significantly 2. imposing residual compressive stresses within a thin outer surface layer • Case (layer)hardening: is a technique whereby both surface hardness and fatigue life are enhanced for steel alloys. This is accomplished by a carburizing or nitriding process whereby a component is exposed to a carbonaceous or nitrogenous Chapter 8 - 36 atmosphere at an elevated temperature.

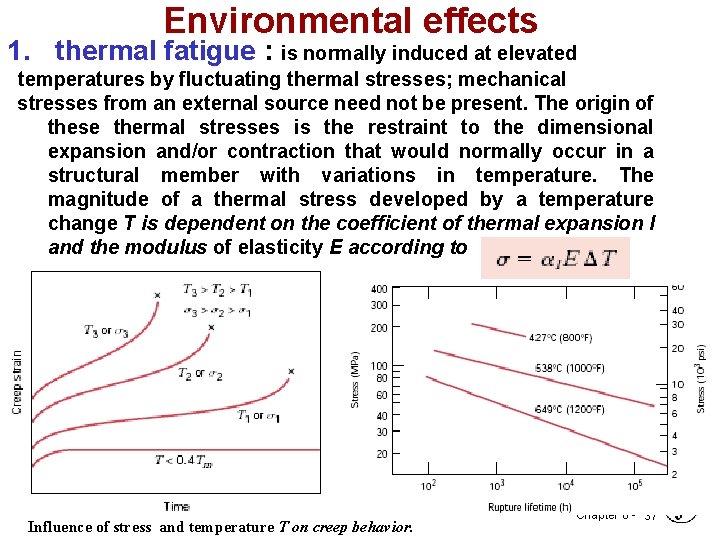

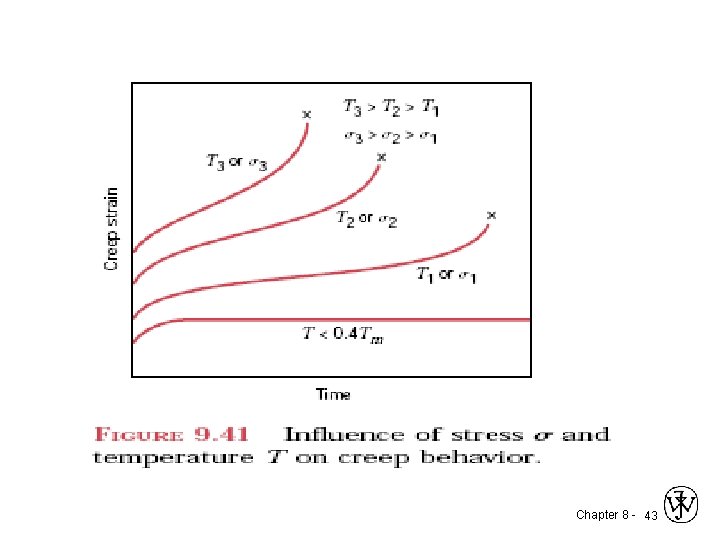

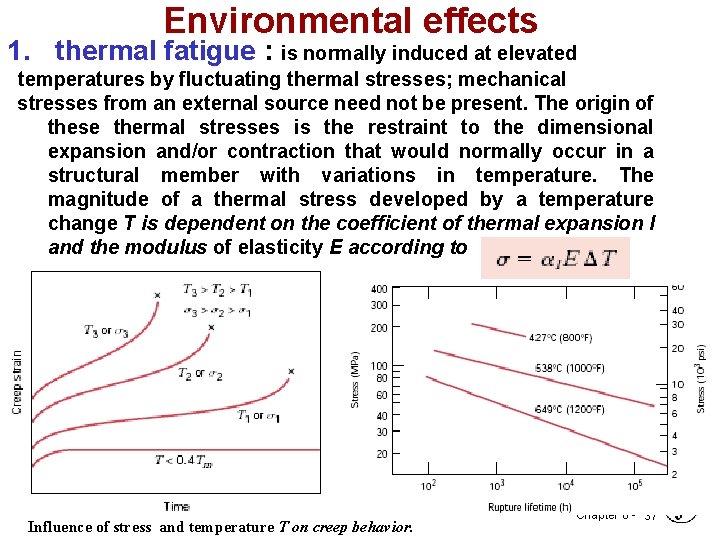

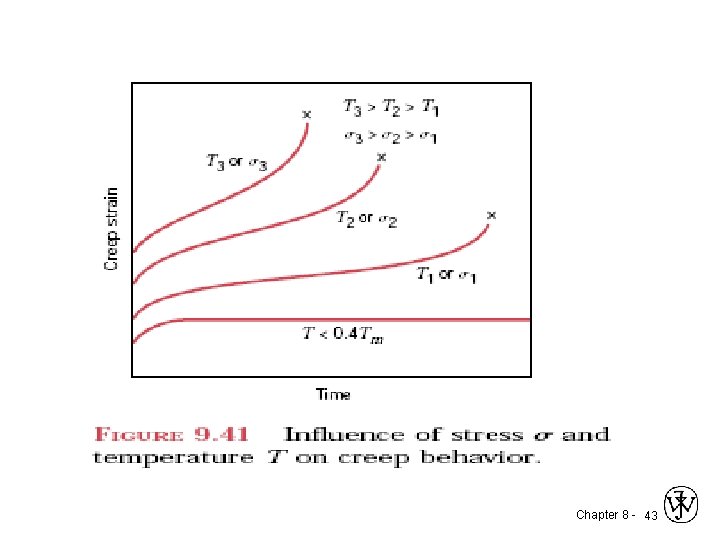

Environmental effects 1. thermal fatigue : is normally induced at elevated temperatures by fluctuating thermal stresses; mechanical stresses from an external source need not be present. The origin of these thermal stresses is the restraint to the dimensional expansion and/or contraction that would normally occur in a structural member with variations in temperature. The magnitude of a thermal stress developed by a temperature change T is dependent on the coefficient of thermal expansion l and the modulus of elasticity E according to • Influence of stress and temperature T on creep behavior. Chapter 8 - 37

2. Corrosion fatigue: Failure that occurs by the simultaneous action of a cyclic stress and chemical attack • Small pits may form as a result of chemical reactions between the environment and material, which serve as points of stress concentration, and therefore as crack nucleation sites. • Several approaches to corrosion fatigue prevention exist: - apply protective surface coatings, - select a more corrosion resistant material - reduce the corrosiveness of the environment. Chapter 8 - 38

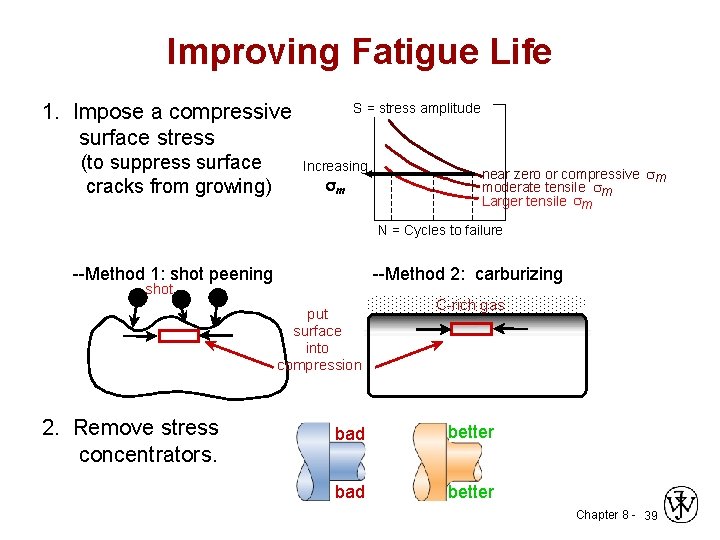

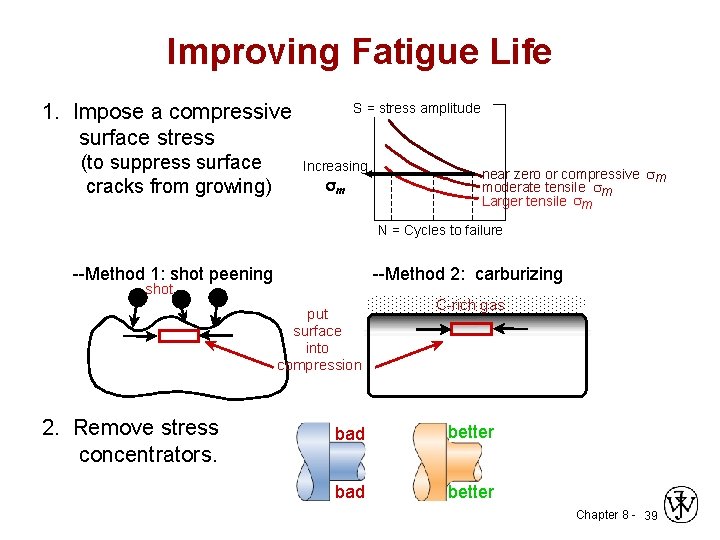

Improving Fatigue Life 1. Impose a compressive surface stress (to suppress surface cracks from growing) S = stress amplitude Increasing m near zero or compressive sm moderate tensile sm Larger tensile sm N = Cycles to failure --Method 1: shot peening --Method 2: carburizing shot put surface into compression 2. Remove stress concentrators. C-rich gas bad better Chapter 8 - 39

3. Creep • The time-dependent permanent deformation that occurs when material are subjected to a constant load or stress; for most materials it is important only at elevated temperatures. • For metals it becomes important only for temperatures greater than about 0. 4 Tm (Tm absolute melting temperature). Chapter 8 - 40

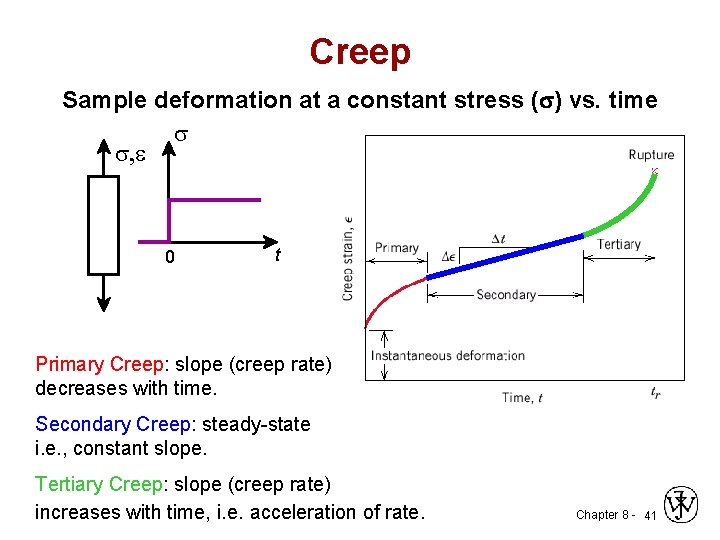

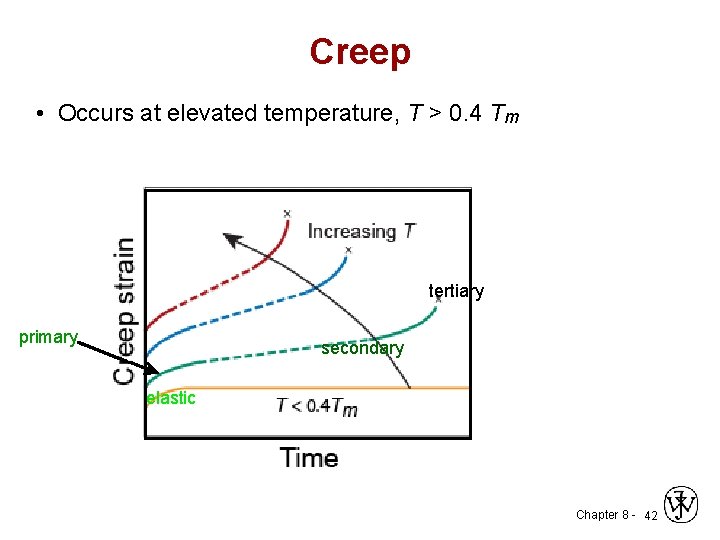

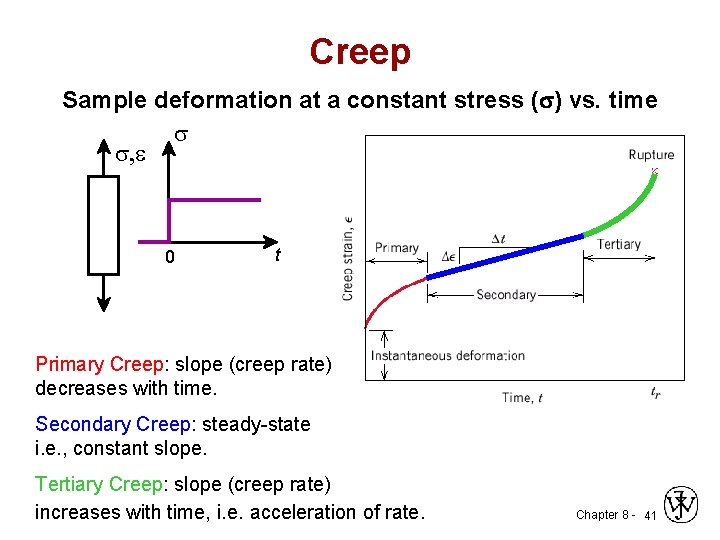

Creep Sample deformation at a constant stress ( ) vs. time s s, e 0 t Primary Creep: slope (creep rate) decreases with time. Secondary Creep: steady-state i. e. , constant slope. Tertiary Creep: slope (creep rate) increases with time, i. e. acceleration of rate. Chapter 8 - 41

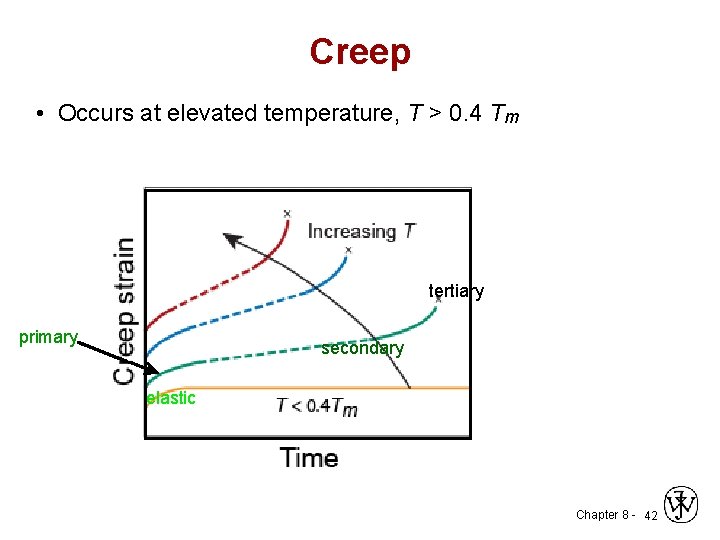

Creep • Occurs at elevated temperature, T > 0. 4 Tm tertiary primary secondary elastic Chapter 8 - 42

Chapter 8 - 43

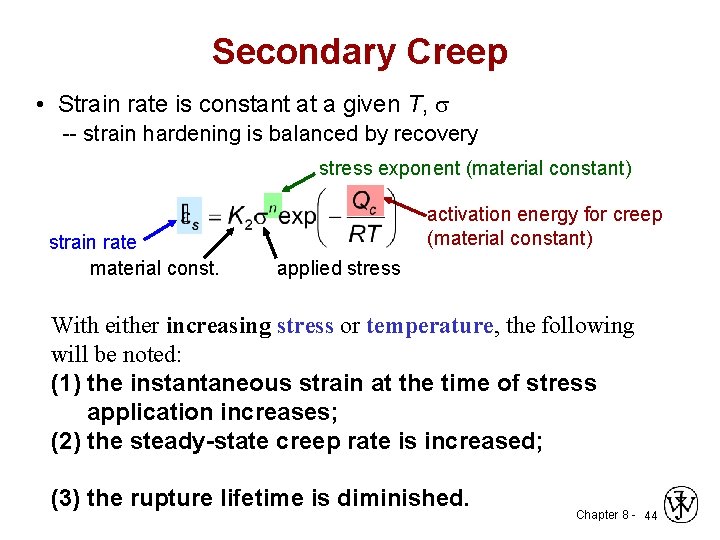

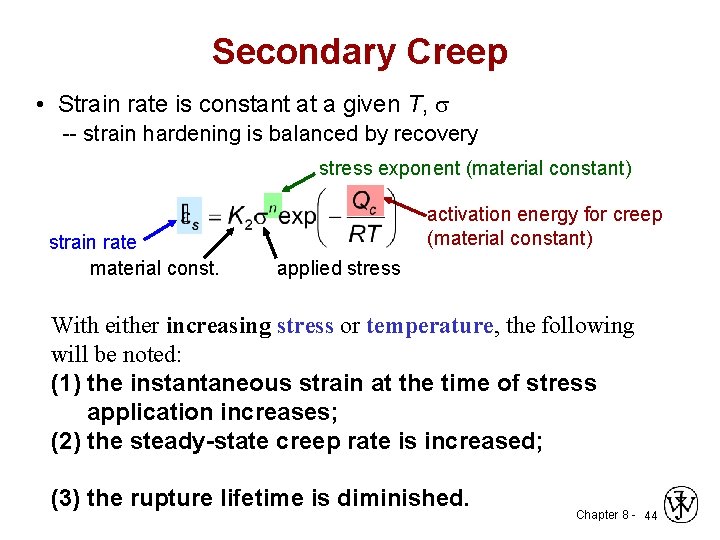

Secondary Creep • Strain rate is constant at a given T, s -- strain hardening is balanced by recovery stress exponent (material constant) strain rate material const. activation energy for creep (material constant) applied stress With either increasing stress or temperature, the following will be noted: (1) the instantaneous strain at the time of stress application increases; (2) the steady-state creep rate is increased; (3) the rupture lifetime is diminished. Chapter 8 - 44

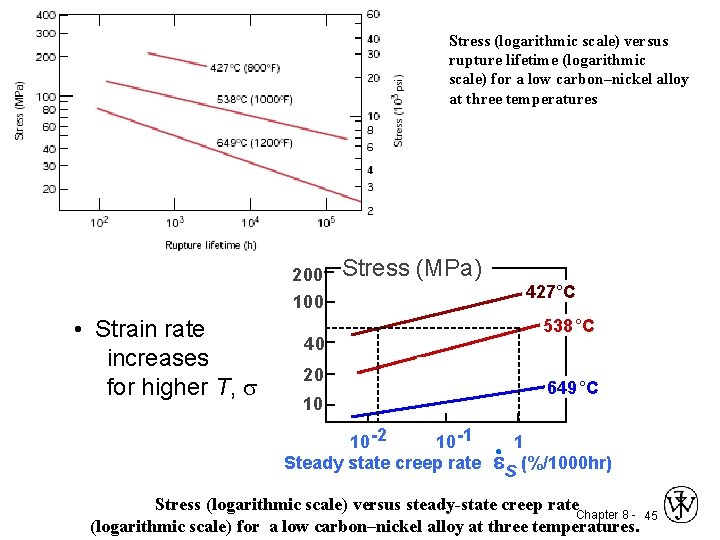

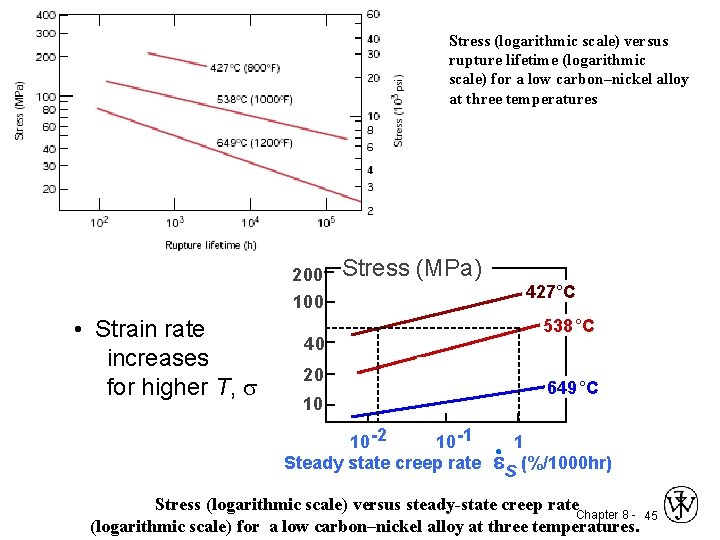

Stress (logarithmic scale) versus rupture lifetime (logarithmic scale) for a low carbon–nickel alloy at three temperatures 200 100 • Strain rate increases for higher T, s Stress (MPa) 40 20 10 10 -2 10 -1 Steady state creep rate 427°C 538 °C 649 °C 1 es (%/1000 hr) Stress (logarithmic scale) versus steady-state creep rate Chapter 8 - 45 (logarithmic scale) for a low carbon–nickel alloy at three temperatures.

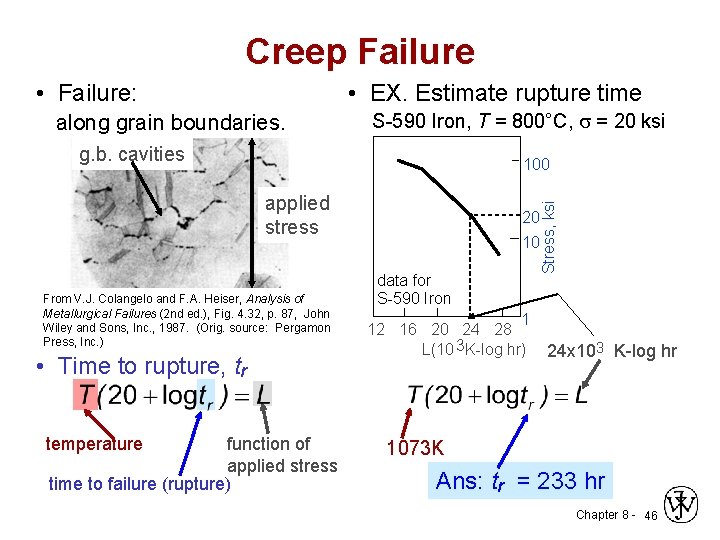

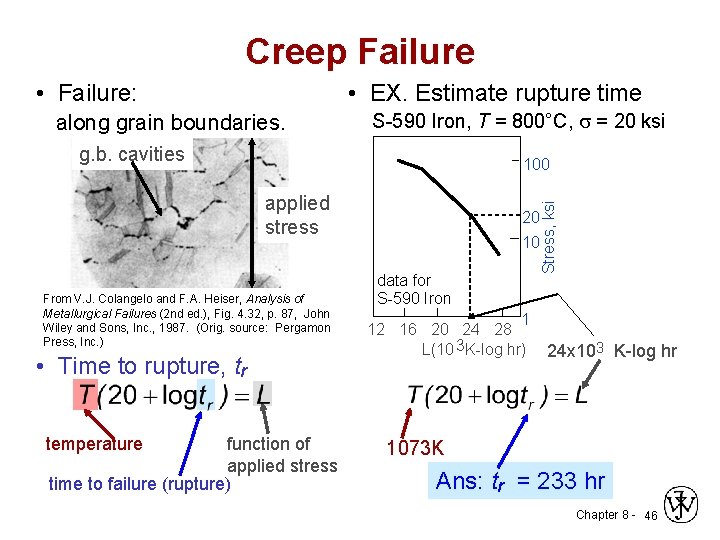

Creep Failure • EX. Estimate rupture time • Failure: along grain boundaries. S-590 Iron, T = 800°C, s = 20 ksi g. b. cavities applied stress From V. J. Colangelo and F. A. Heiser, Analysis of Metallurgical Failures (2 nd ed. ), Fig. 4. 32, p. 87, John Wiley and Sons, Inc. , 1987. (Orig. source: Pergamon Press, Inc. ) • Time to rupture, tr function of applied stress time to failure (rupture) temperature Stress, ksi 100 20 10 data for S-590 Iron 1 12 16 20 24 28 L(10 3 K-log hr) 24 x 103 K-log hr 1073 K Ans: tr = 233 hr Chapter 8 - 46

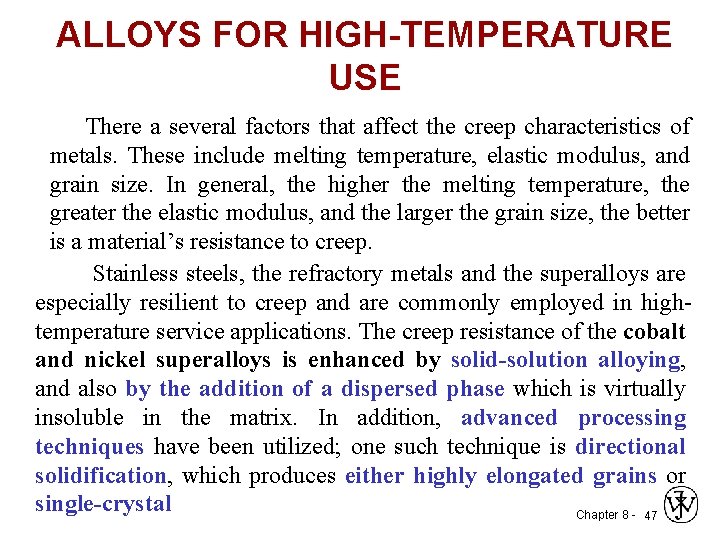

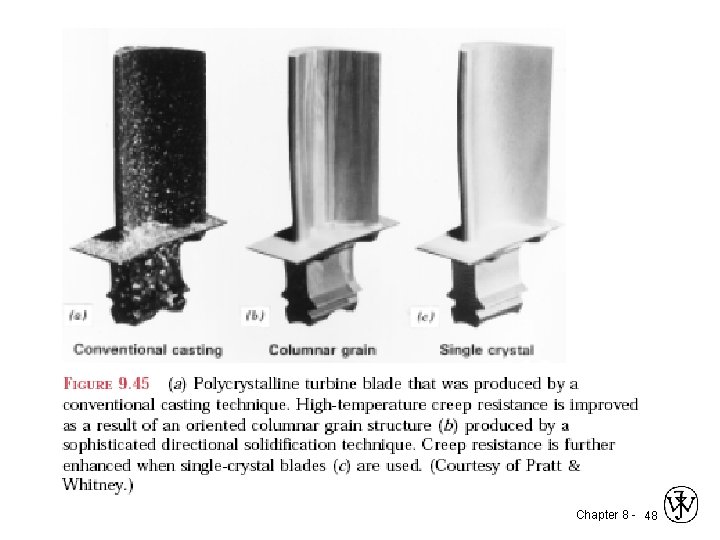

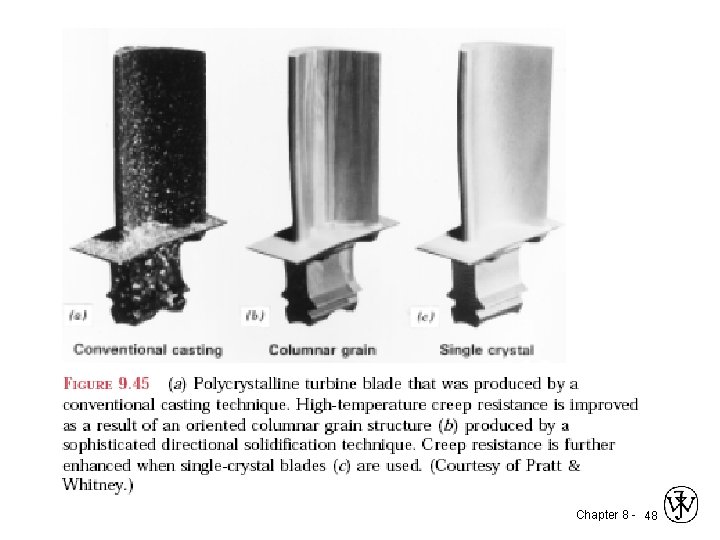

ALLOYS FOR HIGH-TEMPERATURE USE There a several factors that affect the creep characteristics of metals. These include melting temperature, elastic modulus, and grain size. In general, the higher the melting temperature, the greater the elastic modulus, and the larger the grain size, the better is a material’s resistance to creep. Stainless steels, the refractory metals and the superalloys are especially resilient to creep and are commonly employed in hightemperature service applications. The creep resistance of the cobalt and nickel superalloys is enhanced by solid-solution alloying, and also by the addition of a dispersed phase which is virtually insoluble in the matrix. In addition, advanced processing techniques have been utilized; one such technique is directional solidification, which produces either highly elongated grains or single-crystal Chapter 8 - 47

Chapter 8 - 48

4. Corrosion • Corrosion is breaking down! of essential properties in a material due to reactions with its surroundings. In the most common use of the word, this means a loss of an electron of metals reacting with water and oxygen • Weakening of iron due to oxidation of the iron atoms is a well-known example of electrochemical corrosion. This is commonly known as rust This type of damage usually affects metallic materials, and typically produces oxide(s) and/or salt(s) of the original metal Chapter 8 - 49

Rust, the most familiar example of corrosion -- Most structural alloys corrode merely from exposure to moisture in the air, but the process can be strongly affected by exposure to certain substances. Corrosion can be concentrated locally to form a pit or crack, or it can extend across a wide area to produce general deterioration Chapter 8 - 50

Resistant to corrosion 1. Intrinsic chemistry: GOLD nuggets do not corrode, even on a geological time scale. The materials most resistant to corrosion are those for which corrosion is thermodynamically unfavorable. Any corrosion products of gold or platinum tend to decompose spontaneously into pure metal, which is why these elements can be found in metallic form on Earth, and is a large part of their intrinsic value Chapter 8 - 51

2. Passivation: Given the right conditions, a thin film of corrosion products can form on a metal's surface spontaneously, acting as a barrier to further oxidation. When this layer stops growing at less than a micrometre thick under the conditions that a material will be used in, the phenomenon is known as passivation Passivation in air and water is seen in such materials as aluminum, stainless steel, titanium, and silicon Chapter 8 - 52

3. surface treatment ( coating ): Plating, painting, and the application of enamel are the most common anti-corrosion treatments. They work by providing a barrier of corrosion-resistant material between the damaging environment and the (often cheaper, tougher, and/or easier-to -process) structural material Example: chromium on steel Chapter 8 - 53

5. Buckling • In engineering, buckling is a failure mode characterized by a sudden failure of a structural member subjected to high compressive stresses, where the actual compressive stresses at failure are smaller than the ultimate compressive stresses that the material is capable of withstanding. This mode of failure is also described as failure due to elastic instability Chapter 8 - 54

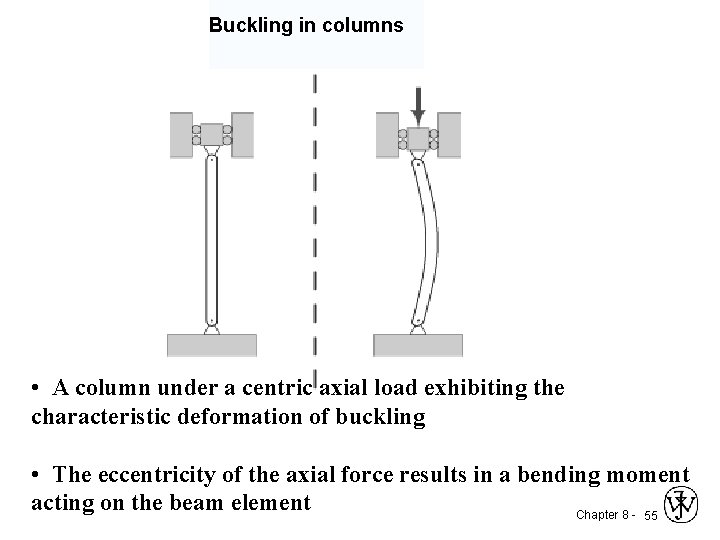

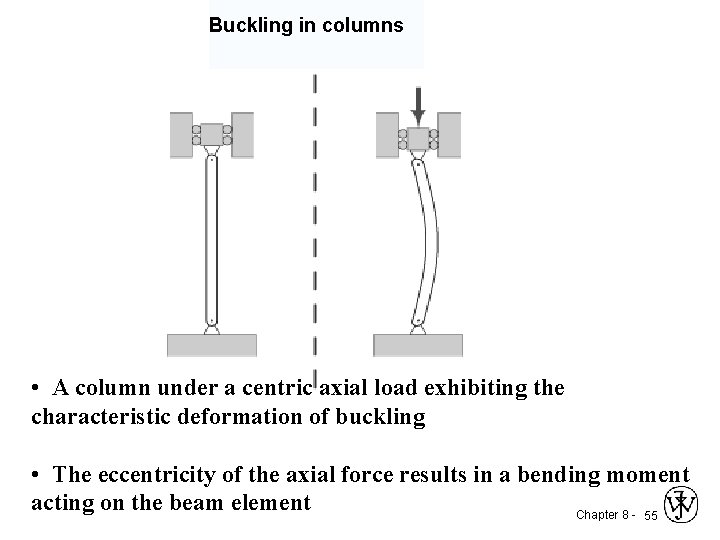

Buckling in columns • A column under a centric axial load exhibiting the characteristic deformation of buckling • The eccentricity of the axial force results in a bending moment acting on the beam element Chapter 8 - 55

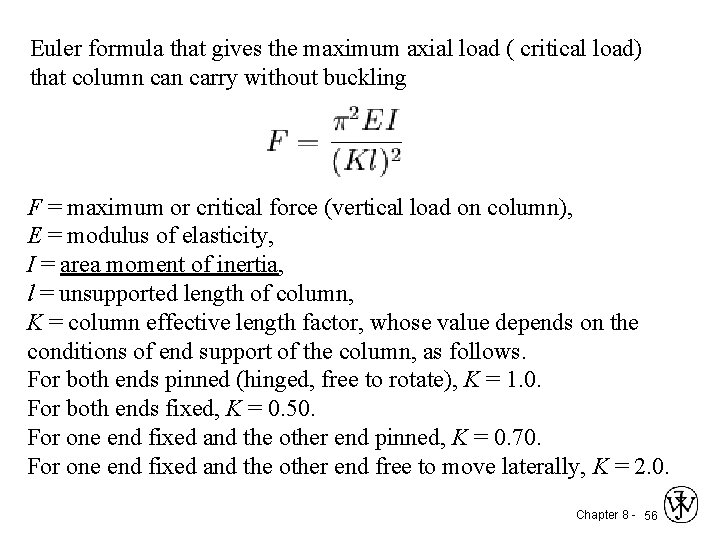

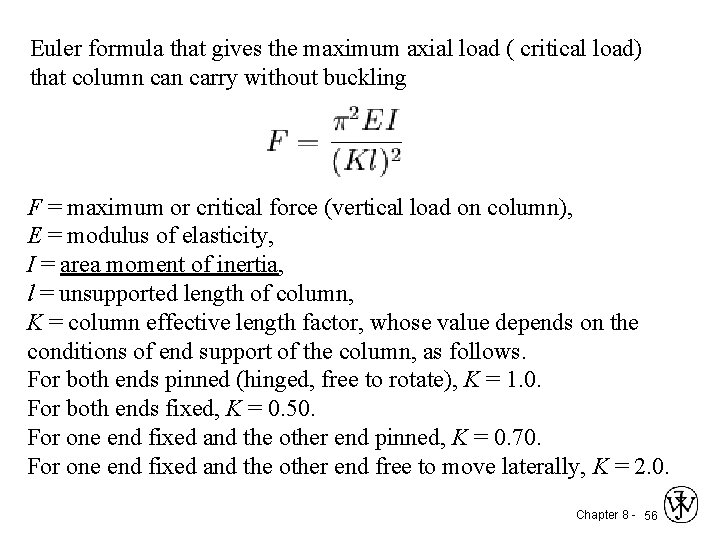

Euler formula that gives the maximum axial load ( critical load) that column carry without buckling F = maximum or critical force (vertical load on column), E = modulus of elasticity, I = area moment of inertia, l = unsupported length of column, K = column effective length factor, whose value depends on the conditions of end support of the column, as follows. For both ends pinned (hinged, free to rotate), K = 1. 0. For both ends fixed, K = 0. 50. For one end fixed and the other end pinned, K = 0. 70. For one end fixed and the other end free to move laterally, K = 2. 0. Chapter 8 - 56

6. Melting • Melting is a process that results in the phase change of a substance from a solid to a liquid. The internal energy of a solid substance is increased (typically by the application of heat) to a specific temperature (called the melting point) at which it changes to the liquid phase. An object that has melted completely is molten • The melting point of a substance is equal to its freezing point Chapter 8 - 57

• Molecular vibrations When the internal energy of a solid is increased by the application of an external energy source, the molecular vibrations of the substance increases. As these vibrations increase, the substance becomes more and more disordered • Constant temperature Substances melt at a constant temperature, the melting point. Further increases in temperature (even with continued application of energy) do not occur until the substance is molten Chapter 8 - 58

7. Thermal chock • Thermal shock is the name given to cracking as a result of rapid temperature change. Glass and ceramic objects are particularly vulnerable to this form of failure, due to their low toughness, low thermal conductivity, and high thermal expansion coefficients • Thermal shock occurs when a thermal gradient causes different parts of an object to expand by different amounts. This differential expansion can be understood in terms of stress or of strain, equivalently. At some point, this stress overcomes the strength of the material, causing a crack to form. If nothing stops this crack from propagating through the material, it will cause the object's structure to fail Chapter 8 - 59

Thermal shock can be prevented by: 1. Reducing thermal gradient seen by the object, by a) changing its temperature more slowly b) increasing the material's thermal conductivity 2. Reducing the material's coefficient of thermal expansion 3. Increasing its strength 4. Increasing its toughness, by a) crack tip blunting, i. e. , plasticity or phase transformation b) crack deflection Chapter 8 - 60

Example. Borosilicate glass such as Pyrex is made to withstand thermal shock better than most other glass through a combination of reduced expansion coefficient and greater strength, though fused quartz outperforms it in both these respects. Some glass-ceramic materials include a controlled proportion of material with a negative expansion coefficient, so that the overall coefficient can be reduced to almost exactly zero over a reasonably wide range of temperatures Chapter 8 - 61

8. wear • Wear is the erosion of material from a solid surface by the action of another solid, or it is a process in which interaction of surface(s) or bounding face(s) of a solid with the working environment results in the dimensional loss of the solid, with or without loss of material • Wear environment includes loads(types include unidirectional sliding, reciprocating, rolling, impact), speed, temperatures, counter-bodies(solid, liquid, gas), types of contact (single phase or multiphase in which phases involved can be liquid plus solid particles plus gas bubbles) Chapter 8 - 62

principal wear processes • There are four principal wear processes: a. Adhesive wear b. Abrasive wear c. Corrosive wear d. Surface fatigue Chapter 8 - 63

a. Adhesive wear is also known as scoring, galling, or seizing. It occurs when two solid surfaces slide over one another under pressure. Surface projections, or asperities, are plastically deformed and eventually welded together by the high local pressure. As sliding continues, these bonds are broken, producing cavities on the surface, projections on the second surface, and frequently tiny, abrasive particles, all of which contribute to future wear of surfaces b. Abrasive wear When material is removed by contact with hard particles, abrasive wear occurs. The particles either may be present at the surface of a second material or may exist as loose particles between two surfaces Chapter 8 - 64

c. Corrosive wear Often referred to simply as “corrosion”, corrosive wear is deterioration of useful properties in a material due to reactions with its environment d. Surface fatigue is a process by which the surface of a material is weakened by cyclic loading, which is one type of general material fatigue Chapter 8 - 65

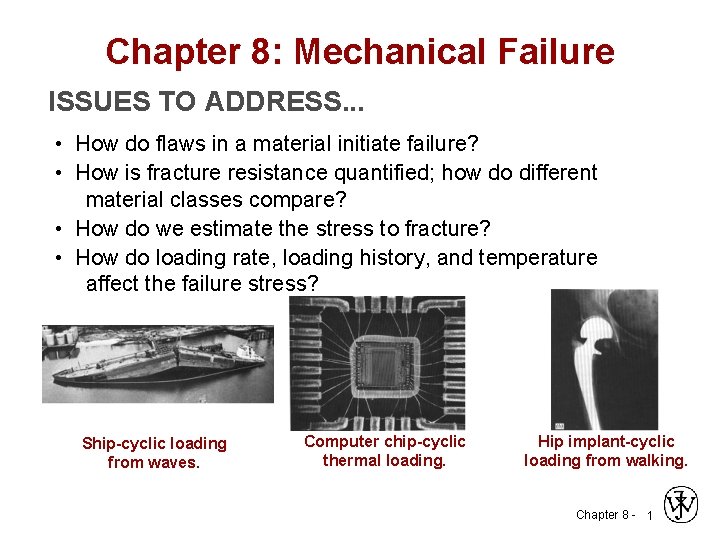

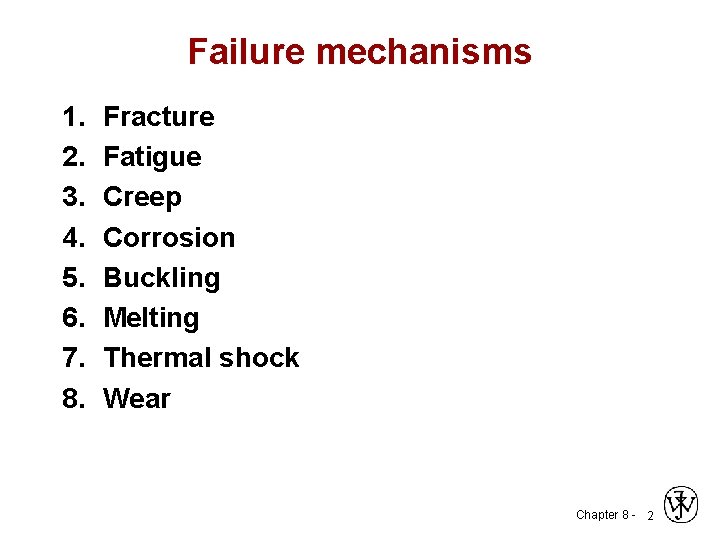

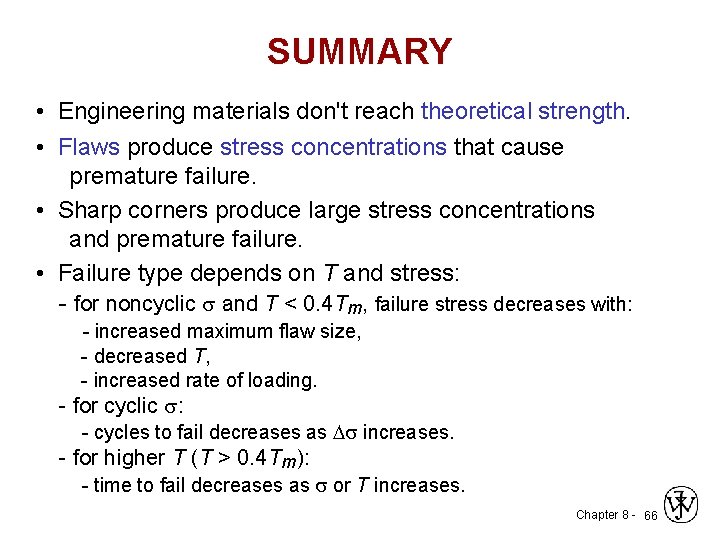

SUMMARY • Engineering materials don't reach theoretical strength. • Flaws produce stress concentrations that cause premature failure. • Sharp corners produce large stress concentrations and premature failure. • Failure type depends on T and stress: - for noncyclic s and T < 0. 4 Tm, failure stress decreases with: - increased maximum flaw size, - decreased T, - increased rate of loading. - for cyclic s: - cycles to fail decreases as Ds increases. - for higher T (T > 0. 4 Tm): - time to fail decreases as s or T increases. Chapter 8 - 66

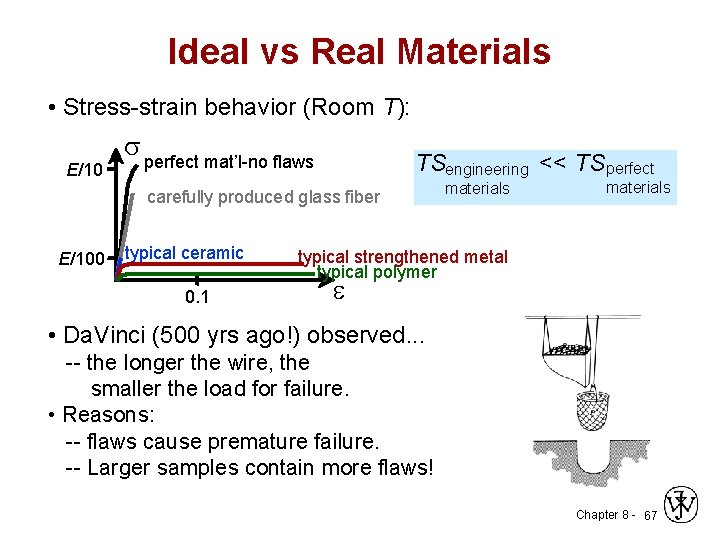

Ideal vs Real Materials • Stress-strain behavior (Room T): E/10 s perfect mat’l-no flaws TSengineering << TS perfect carefully produced glass fiber E/100 typical ceramic 0. 1 materials typical strengthened metal typical polymer e • Da. Vinci (500 yrs ago!) observed. . . -- the longer the wire, the smaller the load for failure. • Reasons: -- flaws cause premature failure. -- Larger samples contain more flaws! Chapter 8 - 67