CHAPTER 8 MECHANICAL FAILURE ISSUES TO ADDRESS How

- Slides: 48

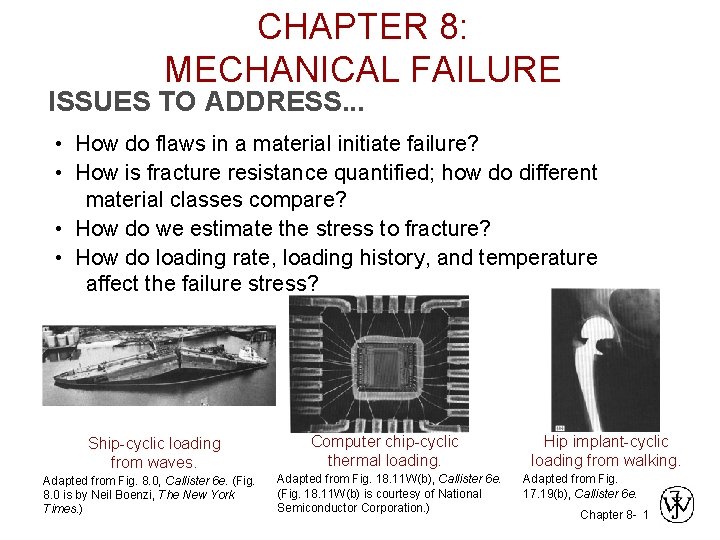

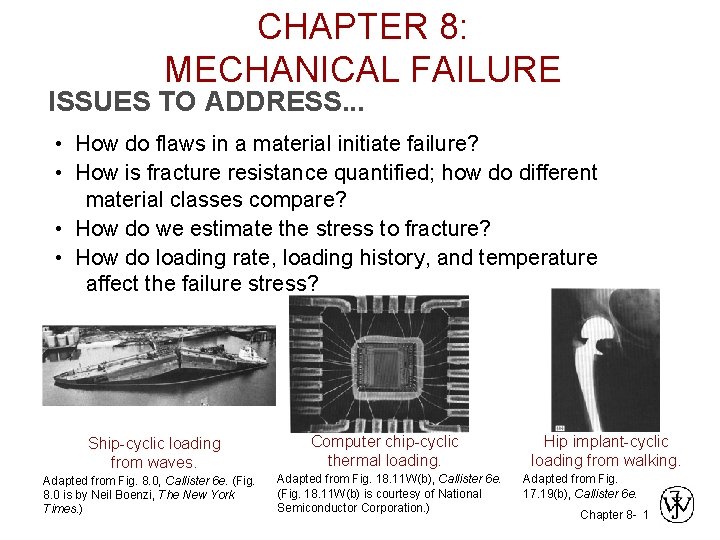

CHAPTER 8: MECHANICAL FAILURE ISSUES TO ADDRESS. . . • How do flaws in a material initiate failure? • How is fracture resistance quantified; how do different material classes compare? • How do we estimate the stress to fracture? • How do loading rate, loading history, and temperature affect the failure stress? Ship-cyclic loading from waves. Adapted from Fig. 8. 0, Callister 6 e. (Fig. 8. 0 is by Neil Boenzi, The New York Times. ) Computer chip-cyclic thermal loading. Adapted from Fig. 18. 11 W(b), Callister 6 e. (Fig. 18. 11 W(b) is courtesy of National Semiconductor Corporation. ) Hip implant-cyclic loading from walking. Adapted from Fig. 17. 19(b), Callister 6 e. Chapter 8 - 1

Mechanical Failure • The usual causes for failure are: – Improper materials selection and processing – Inadequate design – Misuse • Cost of failure – 1000 Billions of $ or YTL annually – Loss of human life ! Chapter 8 -

Fracture mechanisms • Ductile fracture – Occurs with plastic deformation • Brittle fracture – Little or no plastic deformation – Catastrophic Chapter 8 -

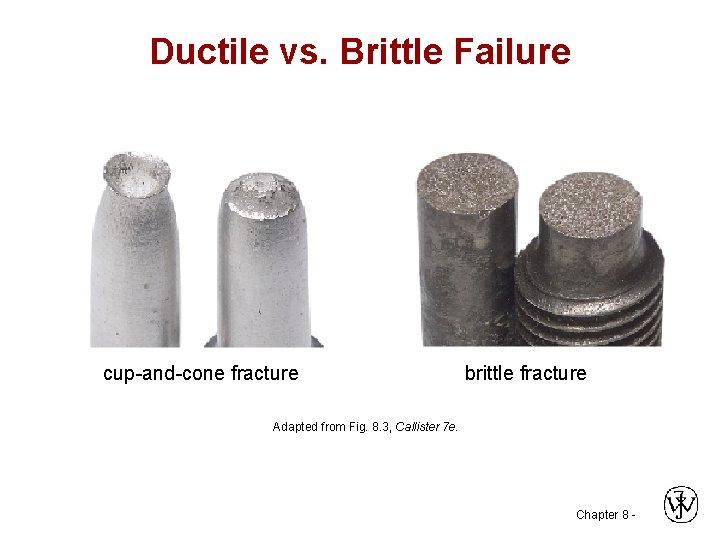

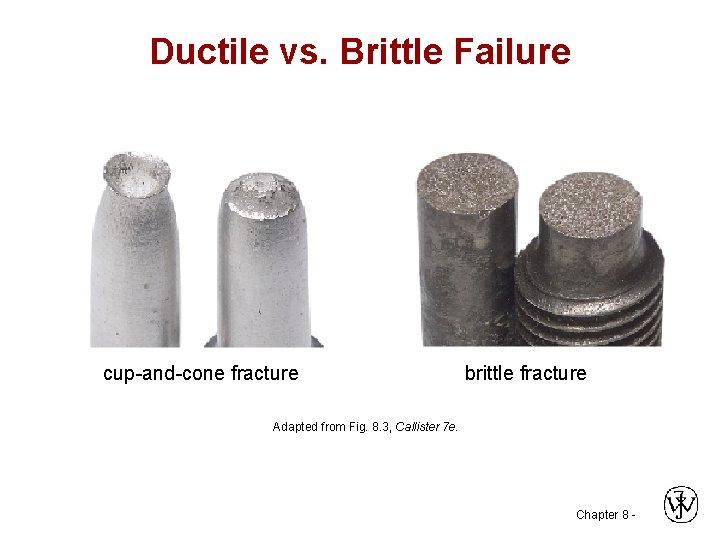

Ductile vs. Brittle Failure cup-and-cone fracture brittle fracture Adapted from Fig. 8. 3, Callister 7 e. Chapter 8 -

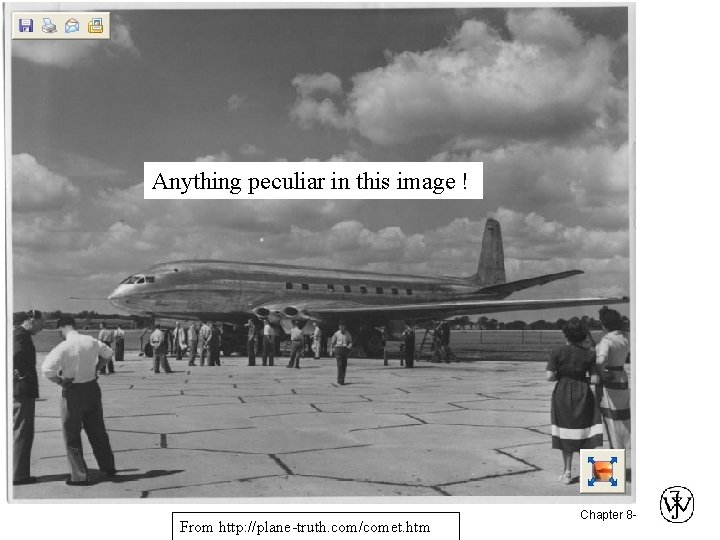

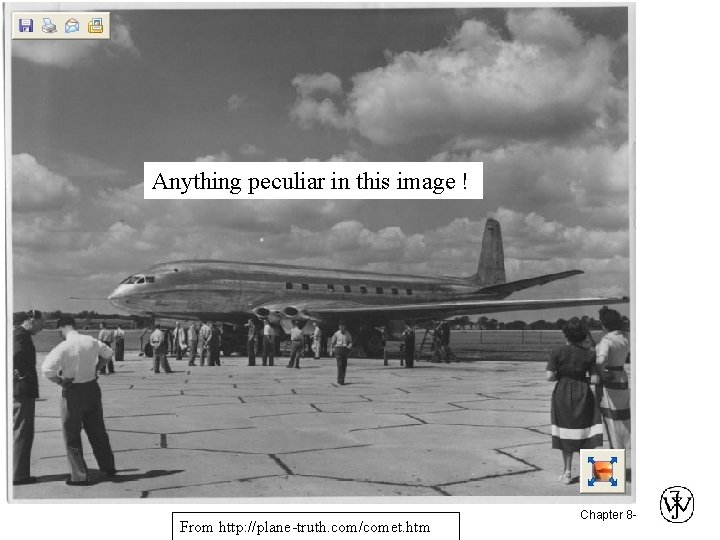

Heverill Fire Department aerial ladder failure from: http: //www. engr. sjsu. edu/Wof. Mat. E/Failure Analy. htm From http: //plane-truth. com/comet. htm Chapter 8 -

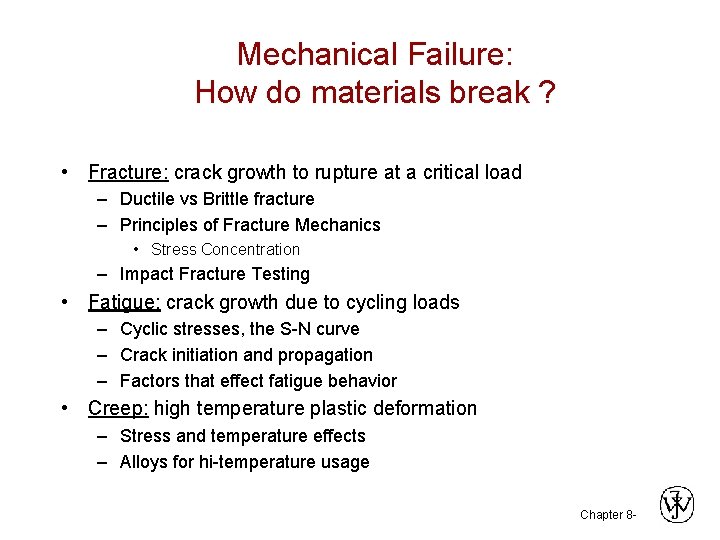

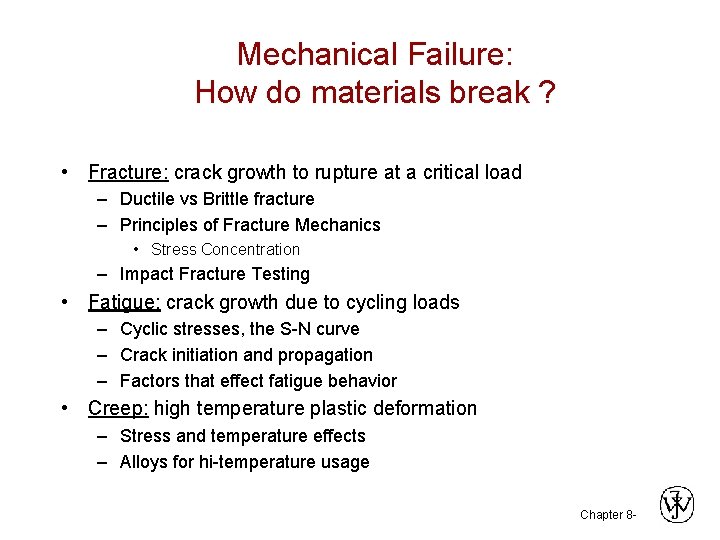

Mechanical Failure: How do materials break ? • Fracture: crack growth to rupture at a critical load – Ductile vs Brittle fracture – Principles of Fracture Mechanics • Stress Concentration – Impact Fracture Testing • Fatigue: crack growth due to cycling loads – Cyclic stresses, the S-N curve – Crack initiation and propagation – Factors that effect fatigue behavior • Creep: high temperature plastic deformation – Stress and temperature effects – Alloys for hi-temperature usage Chapter 8 -

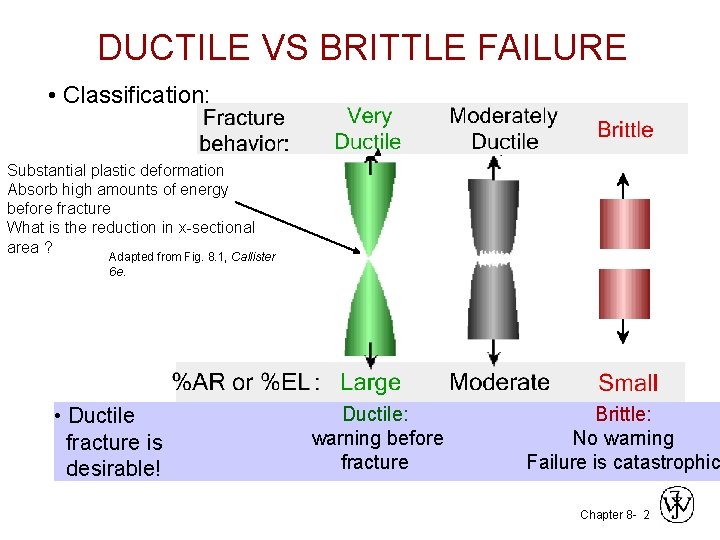

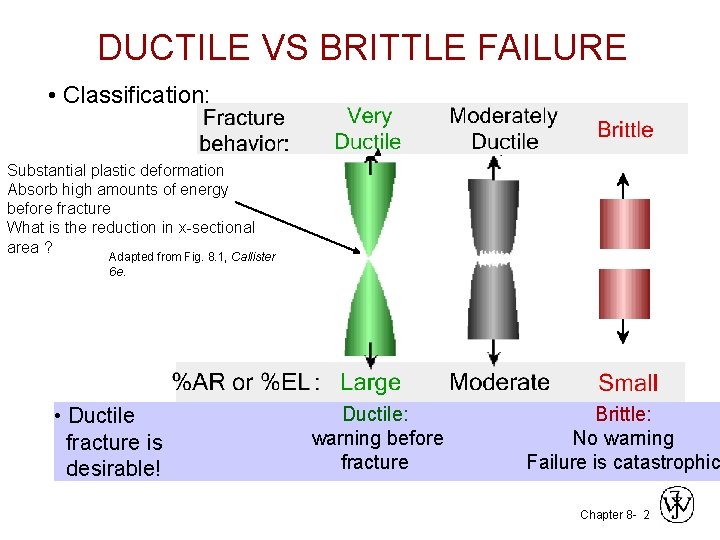

DUCTILE VS BRITTLE FAILURE • Classification: Substantial plastic deformation Absorb high amounts of energy before fracture What is the reduction in x-sectional area ? Adapted from Fig. 8. 1, Callister 6 e. • Ductile fracture is desirable! Ductile: warning before fracture Brittle: No warning Failure is catastrophic Chapter 8 - 2

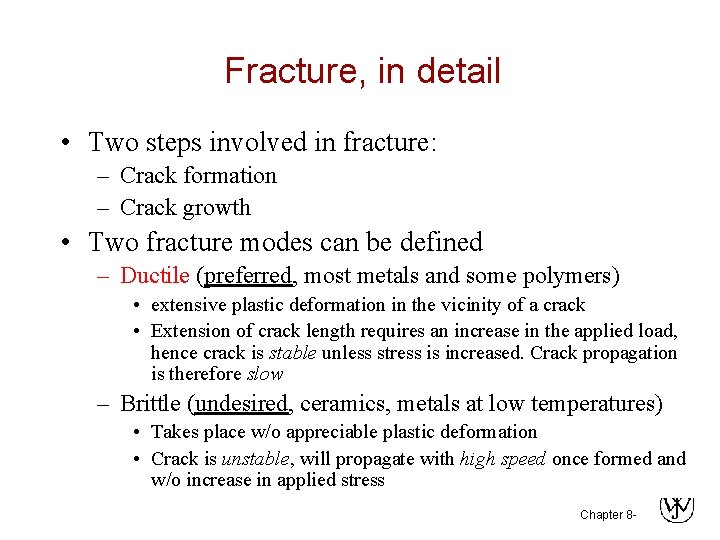

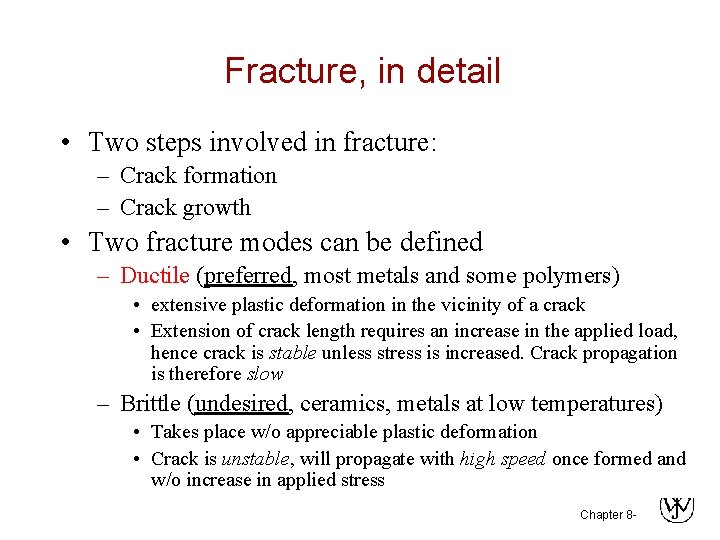

Fracture, in detail • Two steps involved in fracture: – Crack formation – Crack growth • Two fracture modes can be defined – Ductile (preferred, most metals and some polymers) • extensive plastic deformation in the vicinity of a crack • Extension of crack length requires an increase in the applied load, hence crack is stable unless stress is increased. Crack propagation is therefore slow – Brittle (undesired, ceramics, metals at low temperatures) • Takes place w/o appreciable plastic deformation • Crack is unstable, will propagate with high speed once formed and w/o increase in applied stress Chapter 8 -

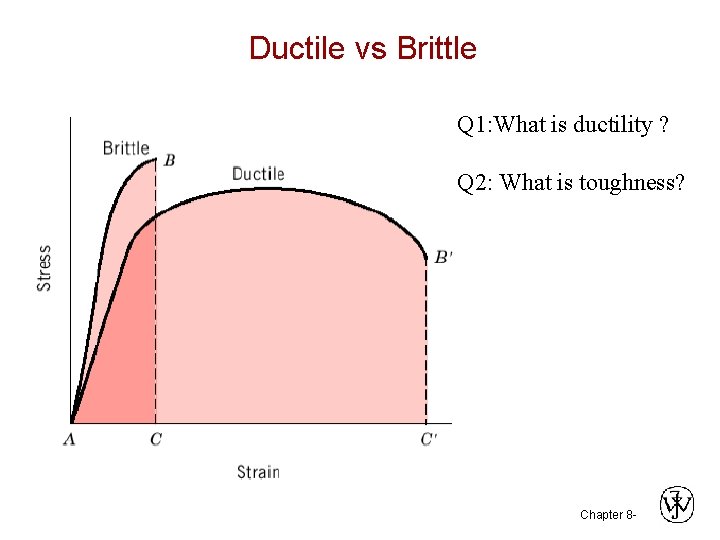

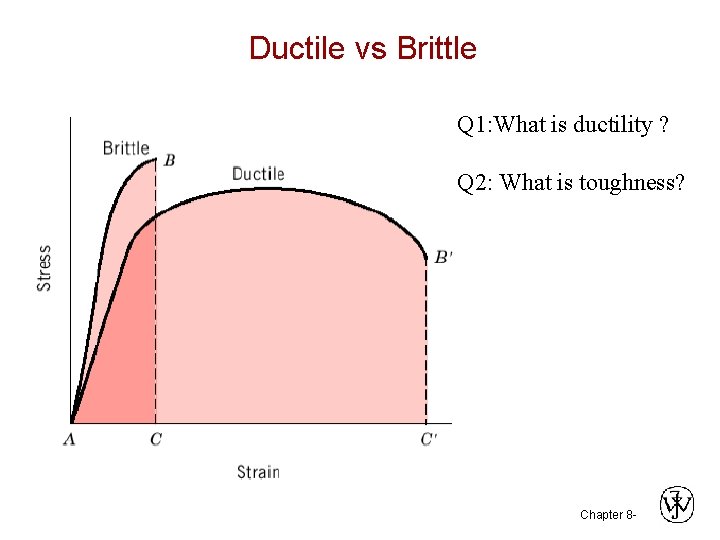

Ductile vs Brittle Q 1: What is ductility ? Q 2: What is toughness? Chapter 8 -

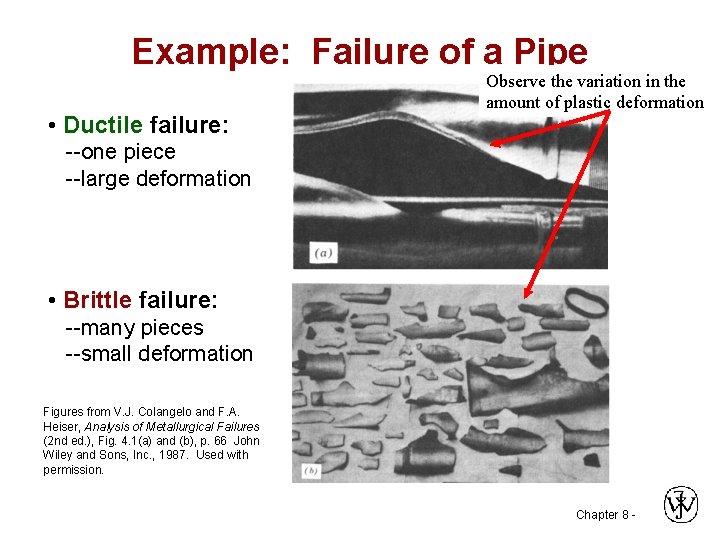

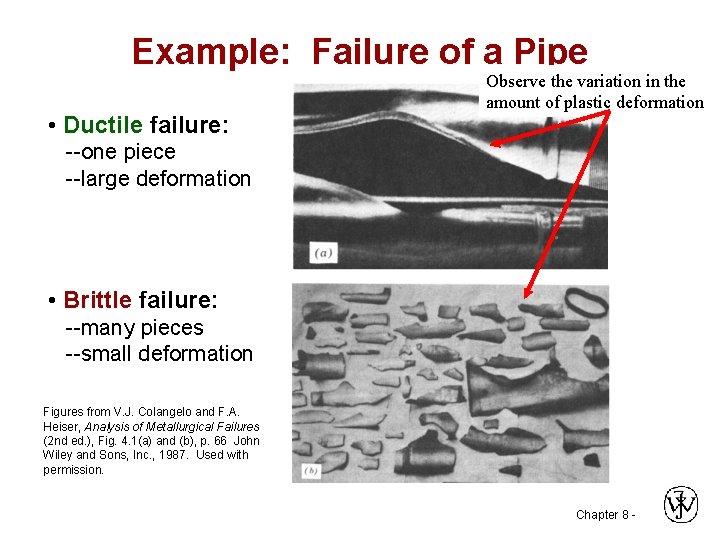

Example: Failure of a Pipe • Ductile failure: Observe the variation in the amount of plastic deformation --one piece --large deformation • Brittle failure: --many pieces --small deformation Figures from V. J. Colangelo and F. A. Heiser, Analysis of Metallurgical Failures (2 nd ed. ), Fig. 4. 1(a) and (b), p. 66 John Wiley and Sons, Inc. , 1987. Used with permission. Chapter 8 -

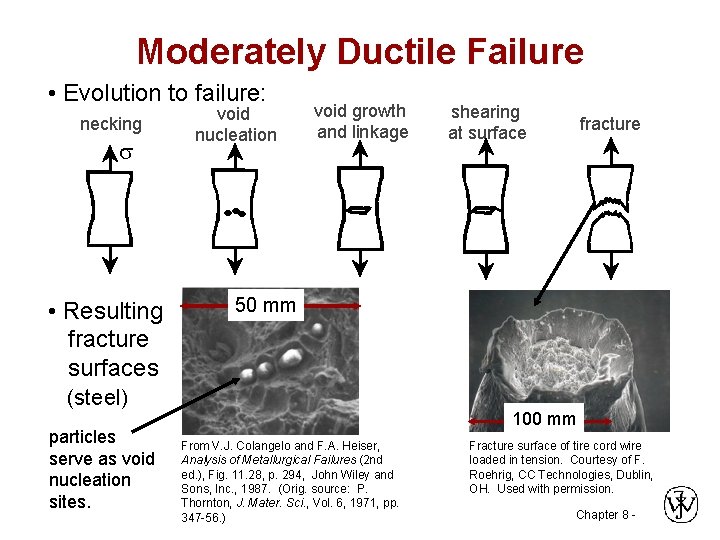

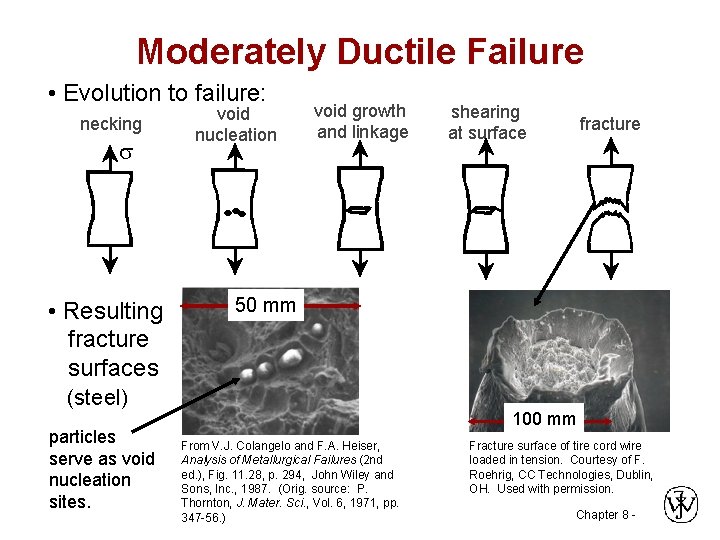

Moderately Ductile Failure • Evolution to failure: necking s • Resulting fracture surfaces void nucleation void growth and linkage fracture 50 50 mm mm (steel) particles serve as void nucleation sites. shearing at surface 100 mm From V. J. Colangelo and F. A. Heiser, Analysis of Metallurgical Failures (2 nd ed. ), Fig. 11. 28, p. 294, John Wiley and Sons, Inc. , 1987. (Orig. source: P. Thornton, J. Mater. Sci. , Vol. 6, 1971, pp. 347 -56. ) Fracture surface of tire cord wire loaded in tension. Courtesy of F. Roehrig, CC Technologies, Dublin, OH. Used with permission. Chapter 8 -

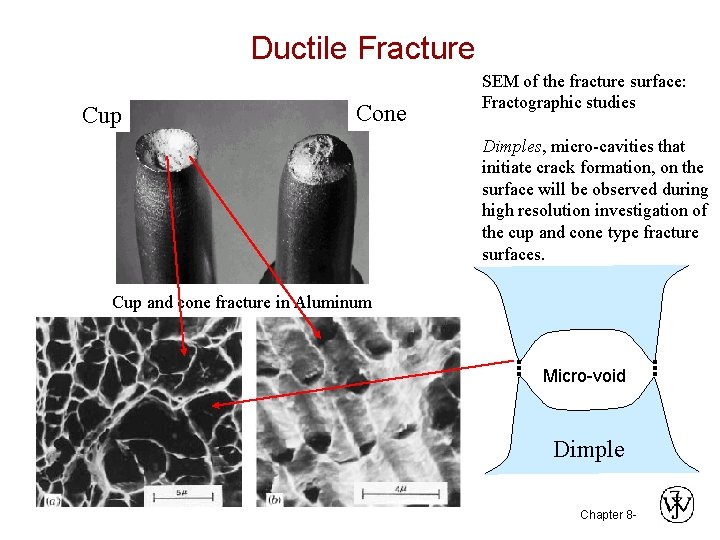

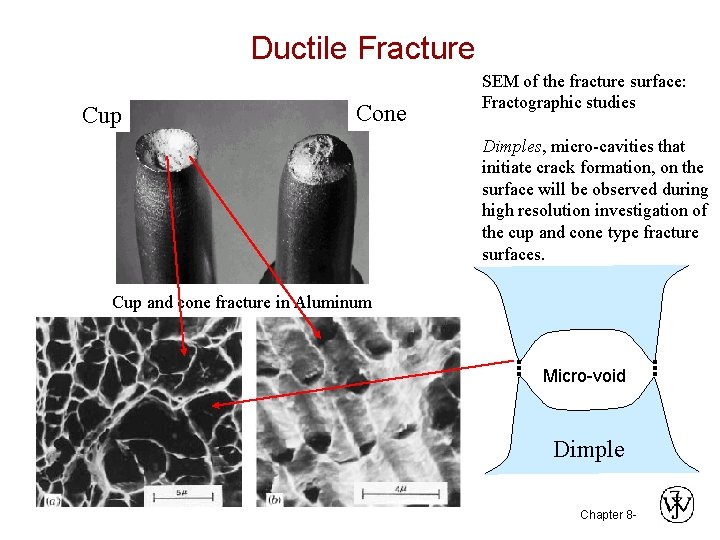

Ductile Fracture Cup Cone SEM of the fracture surface: Fractographic studies Dimples, micro-cavities that initiate crack formation, on the surface will be observed during high resolution investigation of the cup and cone type fracture surfaces. Cup and cone fracture in Aluminum Micro-void Dimple Chapter 8 -

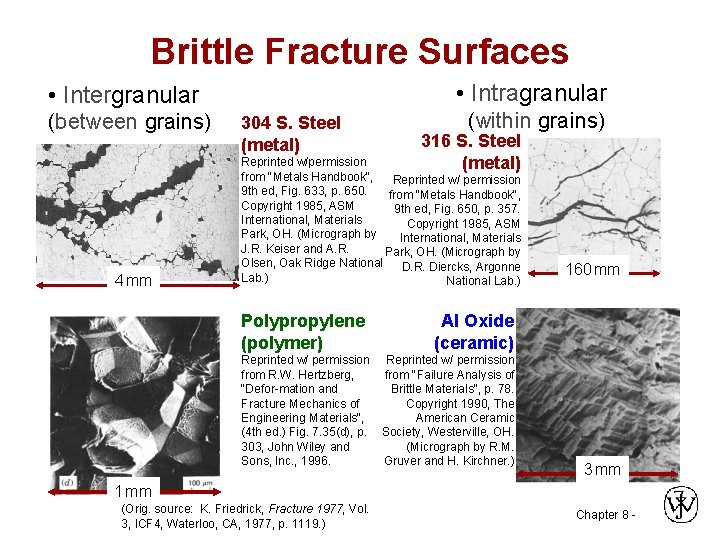

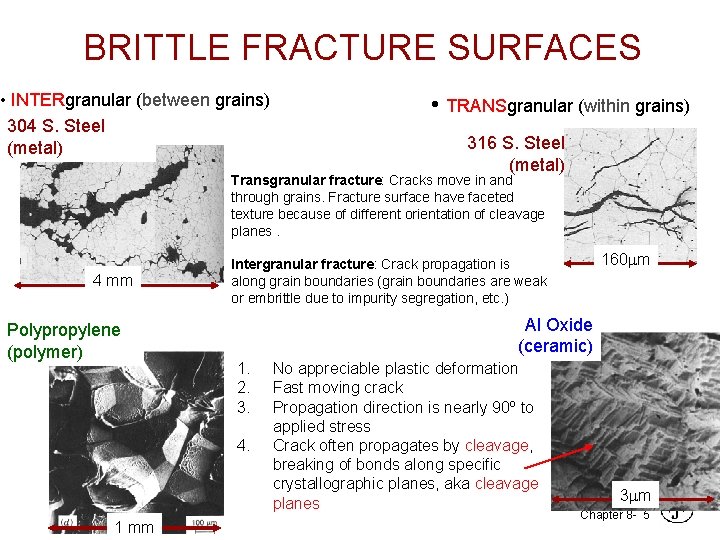

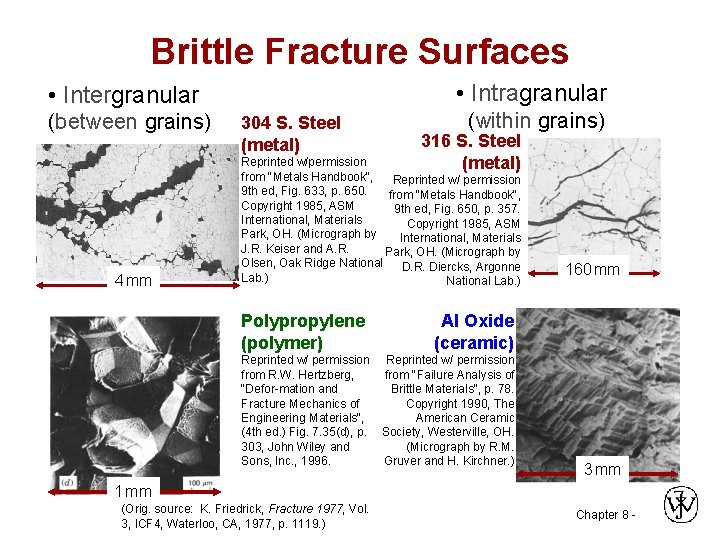

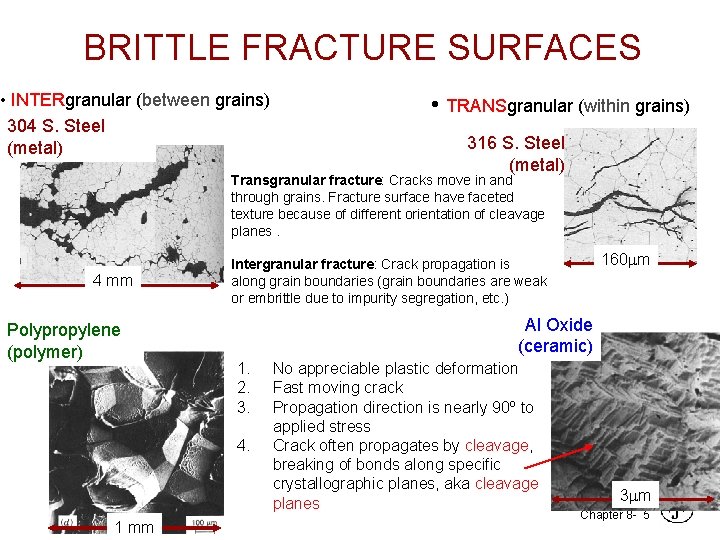

Brittle Fracture Surfaces • Intragranular • Intergranular (between grains) 4 mm 304 S. Steel (metal) (within grains) 316 S. Steel (metal) Reprinted w/permission from "Metals Handbook", Reprinted w/ permission 9 th ed, Fig. 633, p. 650. from "Metals Handbook", Copyright 1985, ASM 9 th ed, Fig. 650, p. 357. International, Materials Copyright 1985, ASM Park, OH. (Micrograph by International, Materials J. R. Keiser and A. R. Park, OH. (Micrograph by Olsen, Oak Ridge National D. R. Diercks, Argonne Lab. ) National Lab. ) Polypropylene (polymer) 160 mm Al Oxide (ceramic) Reprinted w/ permission from R. W. Hertzberg, from "Failure Analysis of "Defor-mation and Brittle Materials", p. 78. Fracture Mechanics of Copyright 1990, The Engineering Materials", American Ceramic (4 th ed. ) Fig. 7. 35(d), p. Society, Westerville, OH. 303, John Wiley and (Micrograph by R. M. Sons, Inc. , 1996. Gruver and H. Kirchner. ) 3 mm 1 mm (Orig. source: K. Friedrick, Fracture 1977, Vol. 3, ICF 4, Waterloo, CA, 1977, p. 1119. ) Chapter 8 -

BRITTLE FRACTURE SURFACES • INTERgranular (between grains) 304 S. Steel (metal) • TRANSgranular (within grains) 316 S. Steel (metal) Transgranular fracture: Cracks move in and through grains. Fracture surface have faceted texture because of different orientation of cleavage planes. 4 mm Polypropylene (polymer) Al Oxide (ceramic) 1. 2. 3. 4. 1 mm 160 mm Intergranular fracture: Crack propagation is along grain boundaries (grain boundaries are weak or embrittle due to impurity segregation, etc. ) No appreciable plastic deformation Fast moving crack Propagation direction is nearly 90º to applied stress Crack often propagates by cleavage, breaking of bonds along specific crystallographic planes, aka cleavage planes 3 mm Chapter 8 - 5

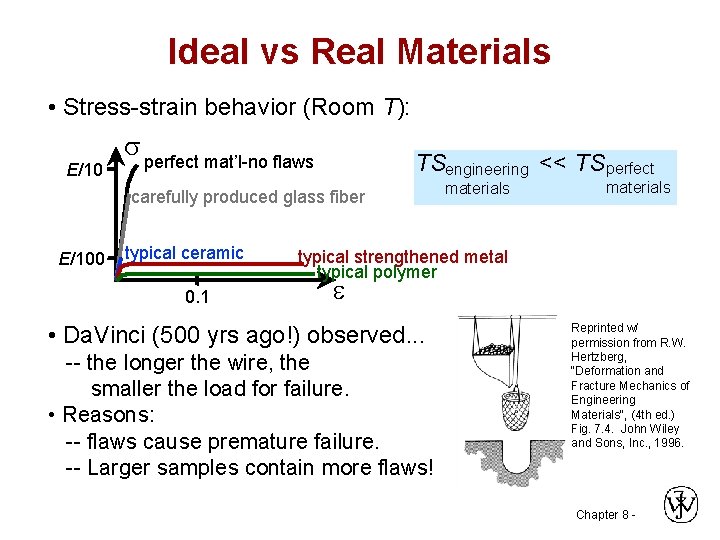

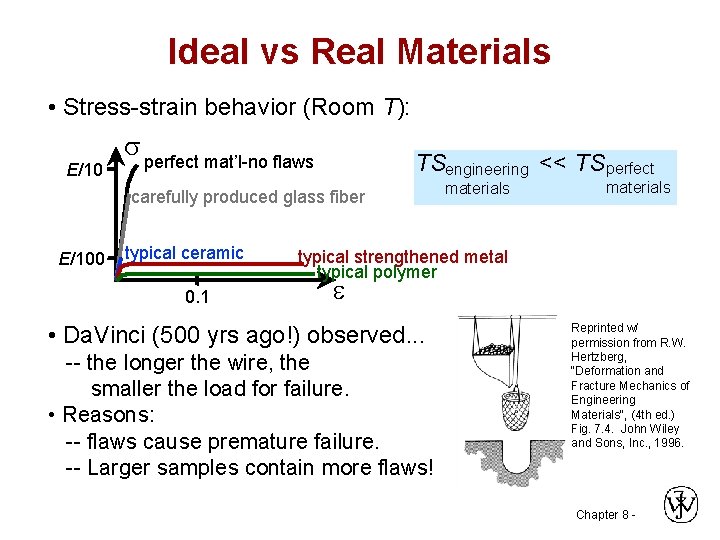

Ideal vs Real Materials • Stress-strain behavior (Room T): E/10 s perfect mat’l-no flaws TSengineering << TS perfect carefully produced glass fiber E/100 typical ceramic 0. 1 materials typical strengthened metal typical polymer e • Da. Vinci (500 yrs ago!) observed. . . -- the longer the wire, the smaller the load for failure. • Reasons: -- flaws cause premature failure. -- Larger samples contain more flaws! Reprinted w/ permission from R. W. Hertzberg, "Deformation and Fracture Mechanics of Engineering Materials", (4 th ed. ) Fig. 7. 4. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. , 1996. Chapter 8 -

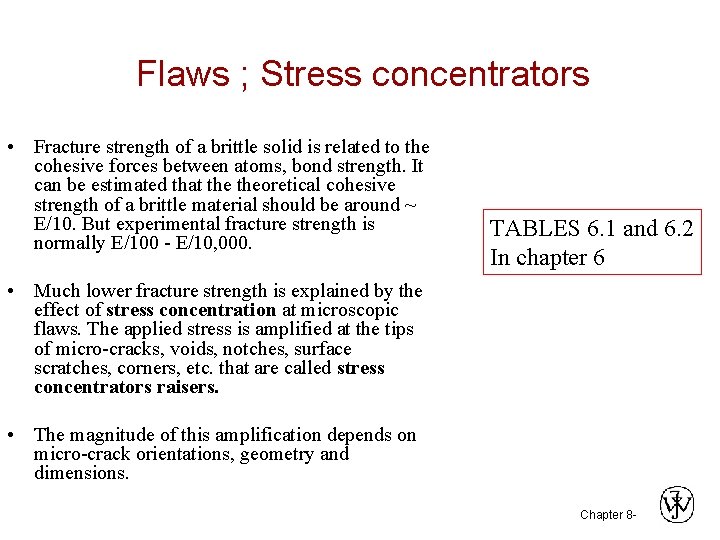

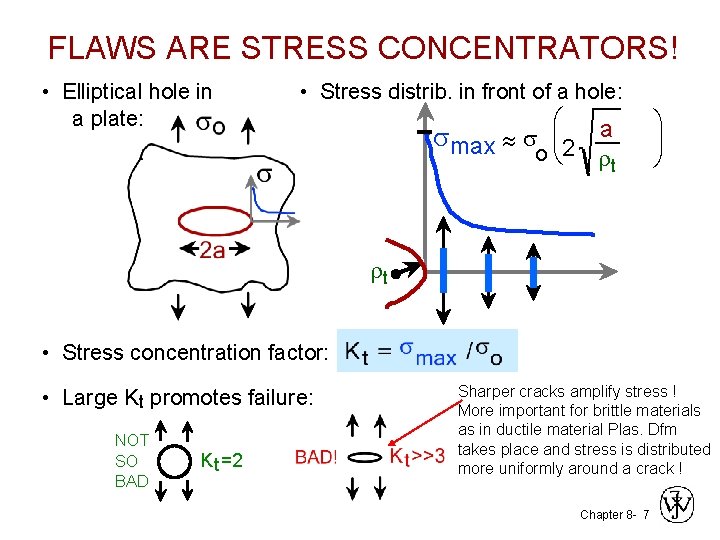

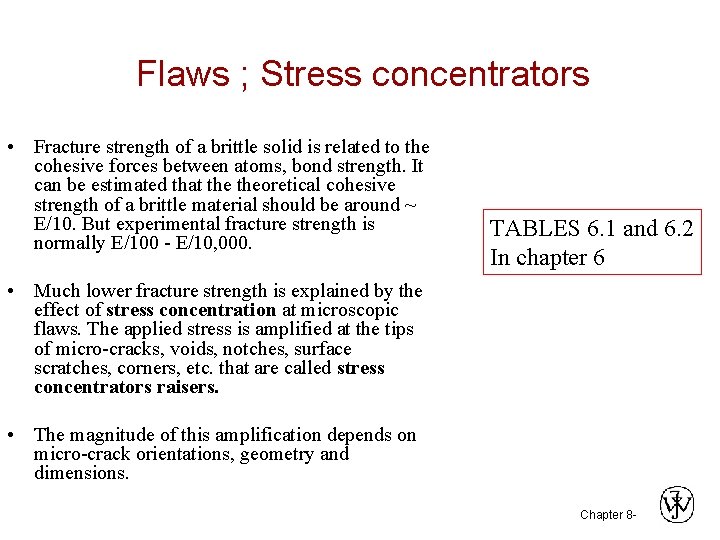

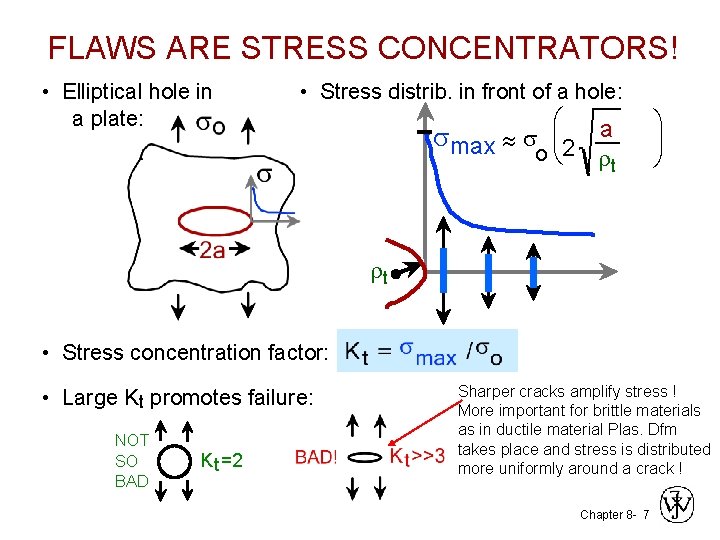

Flaws ; Stress concentrators • Fracture strength of a brittle solid is related to the cohesive forces between atoms, bond strength. It can be estimated that theoretical cohesive strength of a brittle material should be around ~ E/10. But experimental fracture strength is normally E/100 - E/10, 000. TABLES 6. 1 and 6. 2 In chapter 6 • Much lower fracture strength is explained by the effect of stress concentration at microscopic flaws. The applied stress is amplified at the tips of micro-cracks, voids, notches, surface scratches, corners, etc. that are called stress concentrators raisers. • The magnitude of this amplification depends on micro-crack orientations, geometry and dimensions. Chapter 8 -

FLAWS ARE STRESS CONCENTRATORS! • Elliptical hole in a plate: • Stress distrib. in front of a hole: æ smax » s ç 2 a oè t ö ÷ ø t • Stress concentration factor: • Large Kt promotes failure: NOT SO BAD K t =2 Sharper cracks amplify stress ! More important for brittle materials as in ductile material Plas. Dfm takes place and stress is distributed more uniformly around a crack ! Chapter 8 - 7

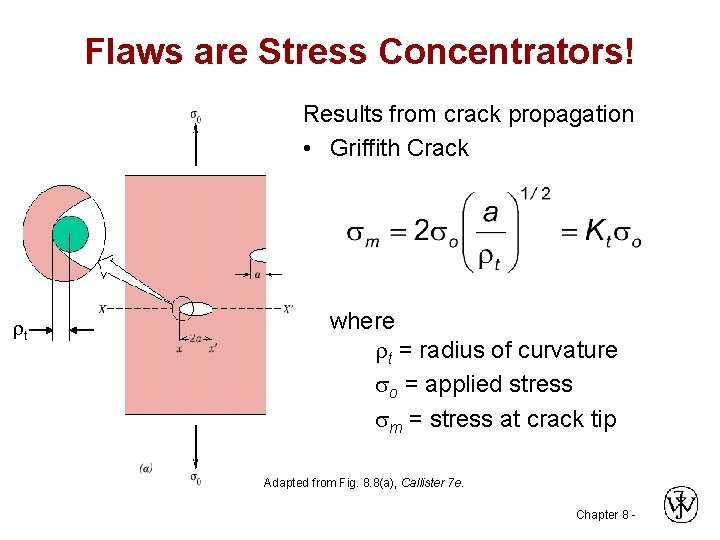

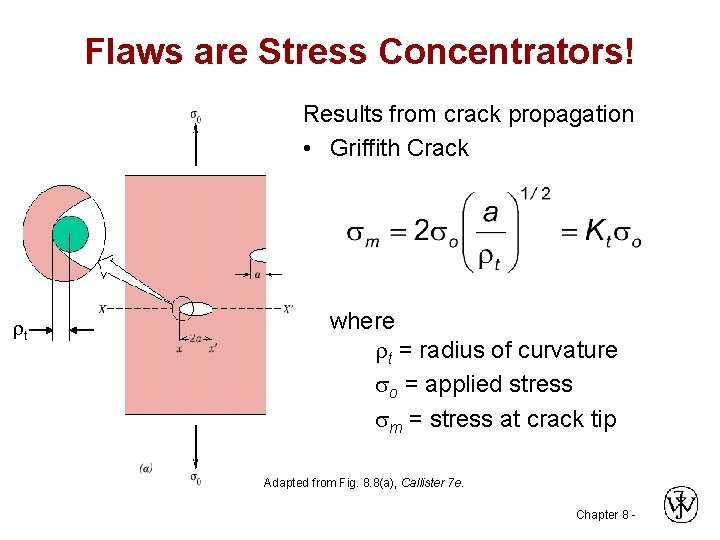

Flaws are Stress Concentrators! Results from crack propagation • Griffith Crack t where t = radius of curvature so = applied stress sm = stress at crack tip Adapted from Fig. 8. 8(a), Callister 7 e. Chapter 8 -

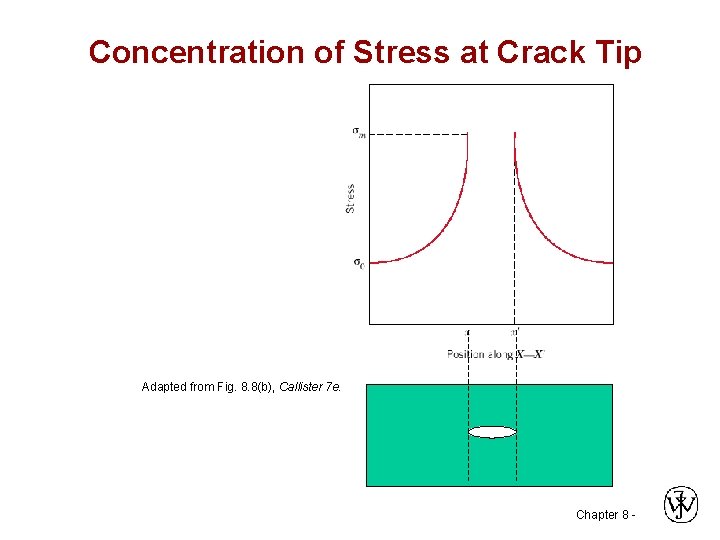

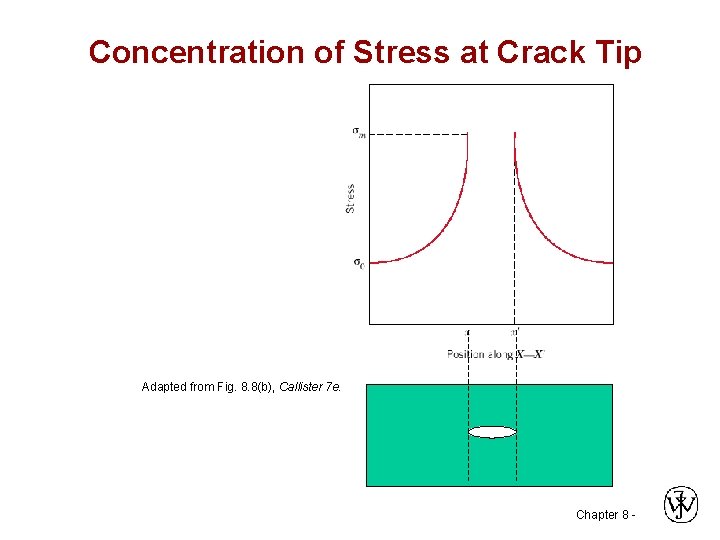

Concentration of Stress at Crack Tip Adapted from Fig. 8. 8(b), Callister 7 e. Chapter 8 -

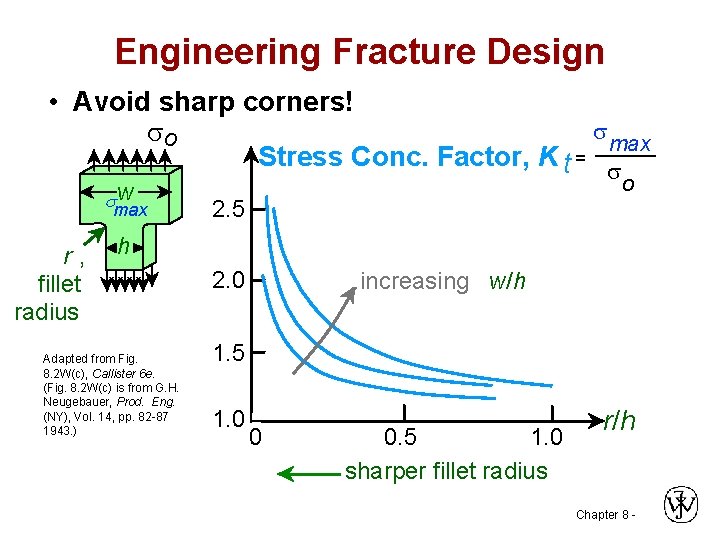

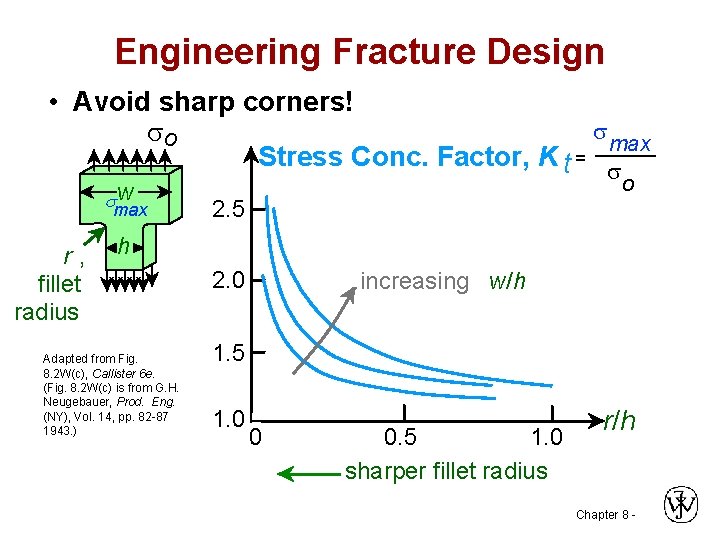

Engineering Fracture Design • Avoid sharp corners! s so max Stress Conc. Factor, K t = s sw max r, fillet radius o 2. 5 h Adapted from Fig. 8. 2 W(c), Callister 6 e. (Fig. 8. 2 W(c) is from G. H. Neugebauer, Prod. Eng. (NY), Vol. 14, pp. 82 -87 1943. ) 2. 0 increasing w/h 1. 5 1. 0 0 0. 5 1. 0 sharper fillet radius r/h Chapter 8 -

Anything peculiar in this image ! From http: //plane-truth. com/comet. htm Chapter 8 -

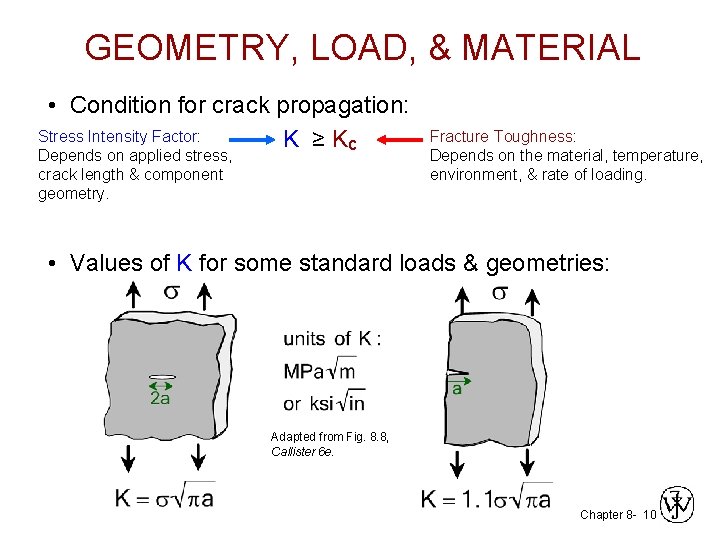

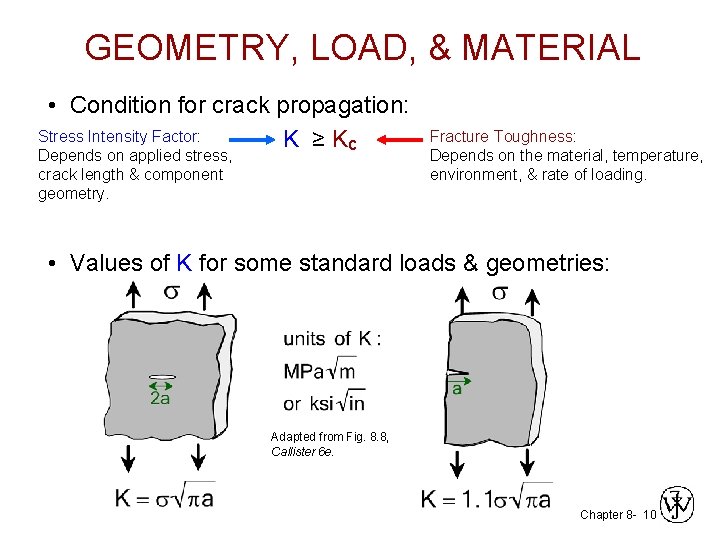

GEOMETRY, LOAD, & MATERIAL • Condition for crack propagation: Stress Intensity Factor: K ≥ Kc Depends on applied stress, crack length & component geometry. Fracture Toughness: Depends on the material, temperature, environment, & rate of loading. • Values of K for some standard loads & geometries: Adapted from Fig. 8. 8, Callister 6 e. Chapter 8 - 10

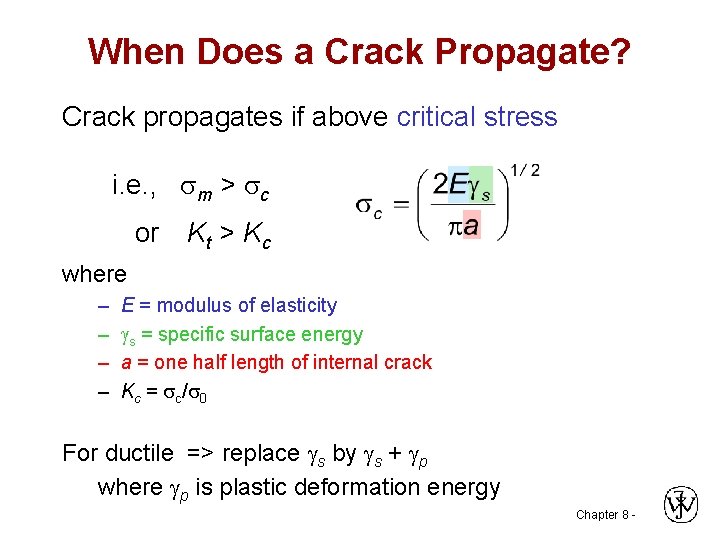

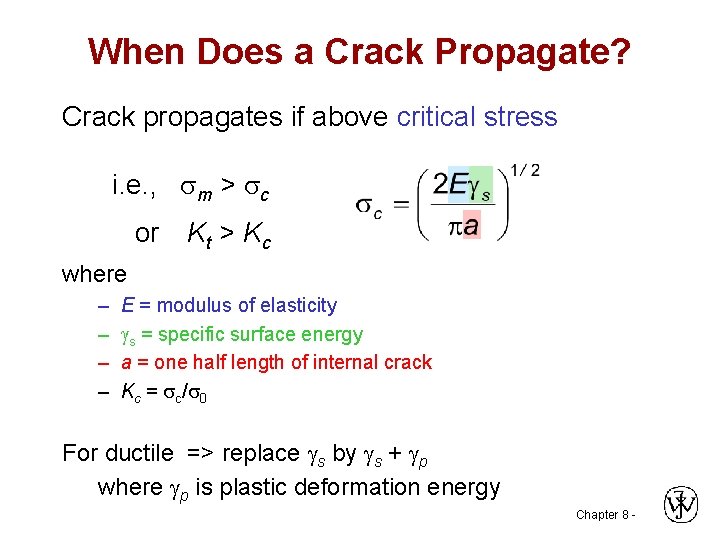

When Does a Crack Propagate? Crack propagates if above critical stress i. e. , sm > sc or Kt > Kc where – – E = modulus of elasticity s = specific surface energy a = one half length of internal crack Kc = sc/s 0 For ductile => replace s by s + p where p is plastic deformation energy Chapter 8 -

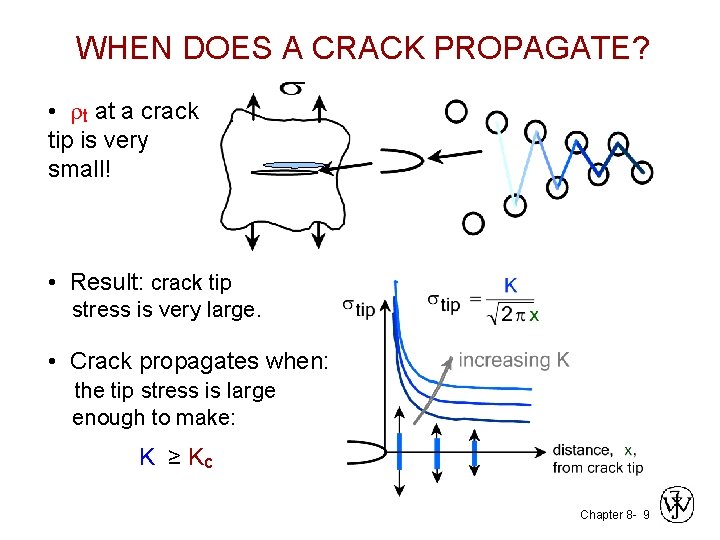

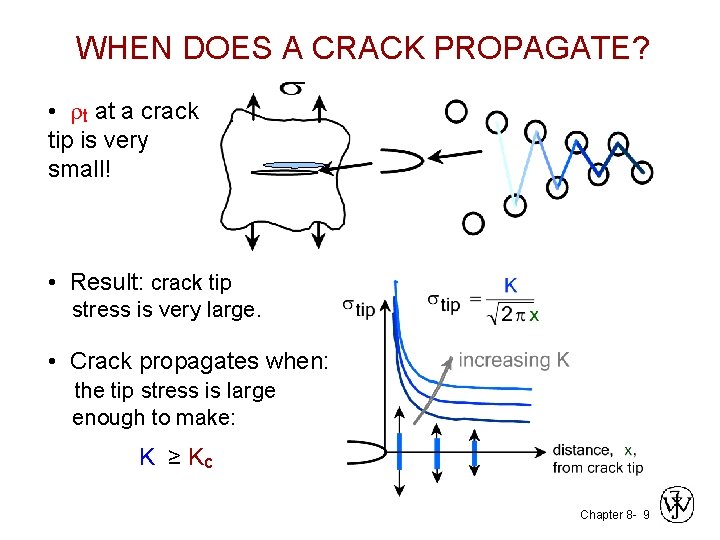

WHEN DOES A CRACK PROPAGATE? • t at a crack tip is very small! • Result: crack tip stress is very large. • Crack propagates when: the tip stress is large enough to make: K ≥ Kc Chapter 8 - 9

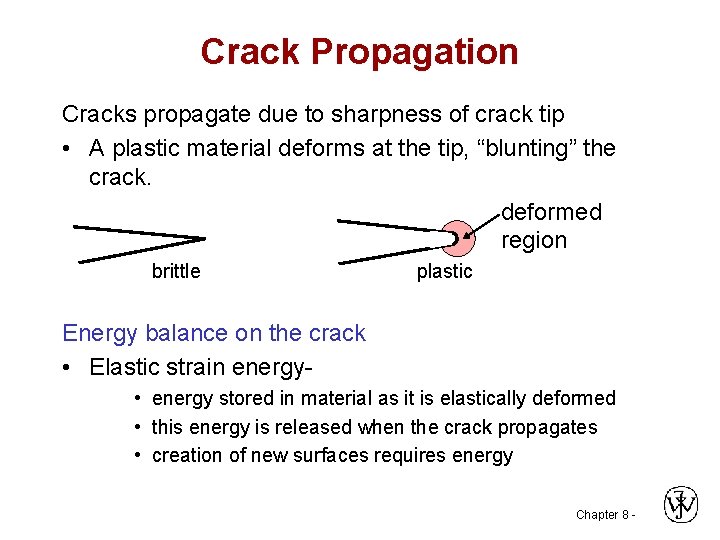

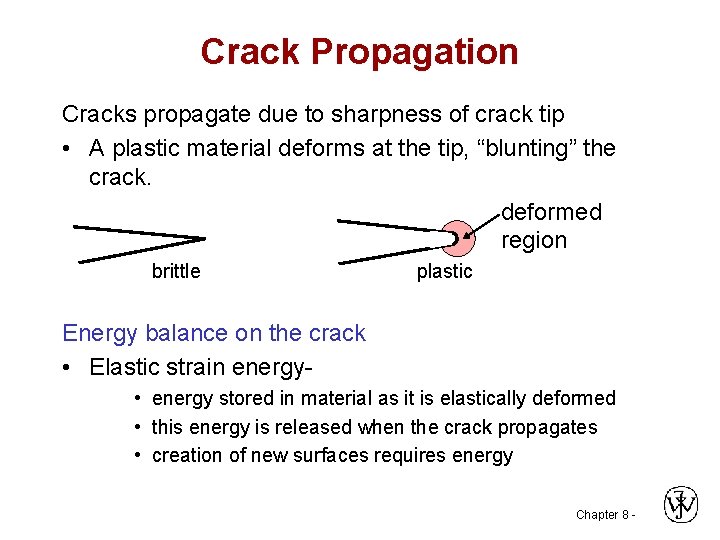

Crack Propagation Cracks propagate due to sharpness of crack tip • A plastic material deforms at the tip, “blunting” the crack. deformed region brittle plastic Energy balance on the crack • Elastic strain energy • energy stored in material as it is elastically deformed • this energy is released when the crack propagates • creation of new surfaces requires energy Chapter 8 -

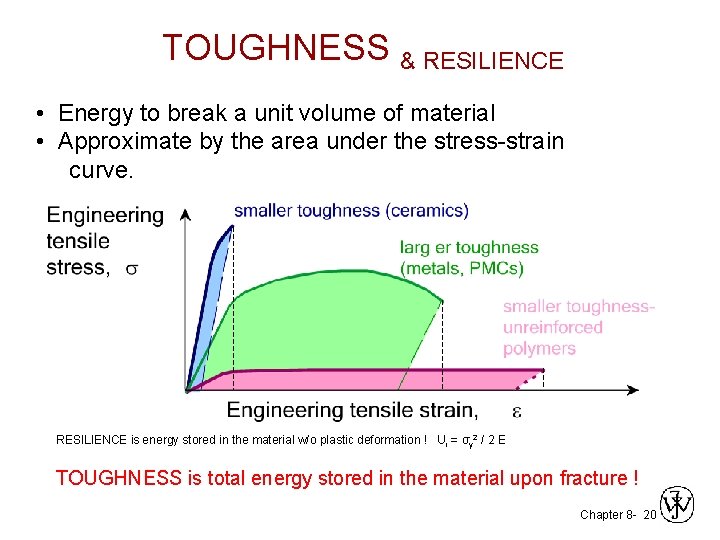

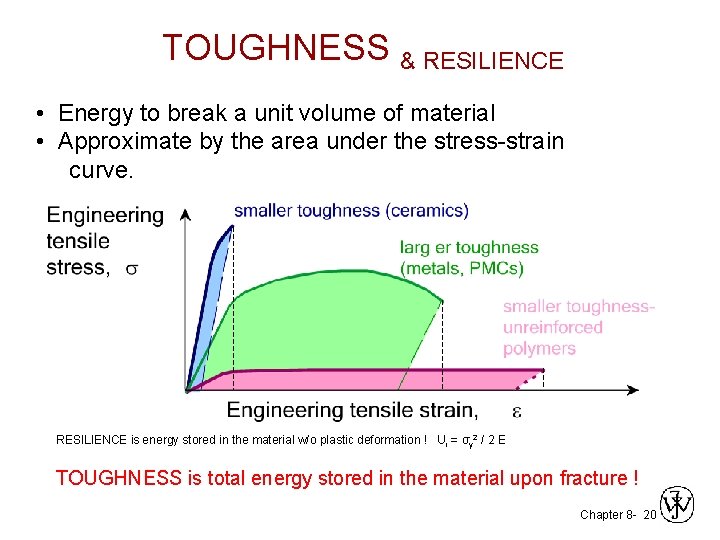

TOUGHNESS & RESILIENCE • Energy to break a unit volume of material • Approximate by the area under the stress-strain curve. RESILIENCE is energy stored in the material w/o plastic deformation ! Ur = σy 2 / 2 E TOUGHNESS is total energy stored in the material upon fracture ! Chapter 8 - 20

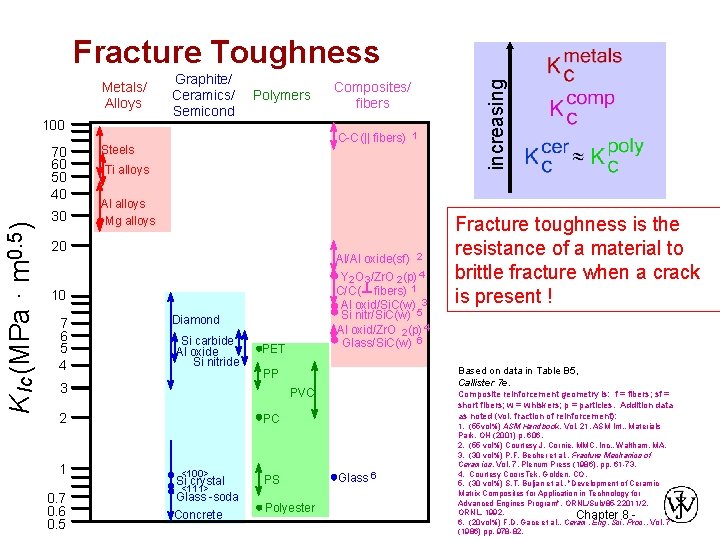

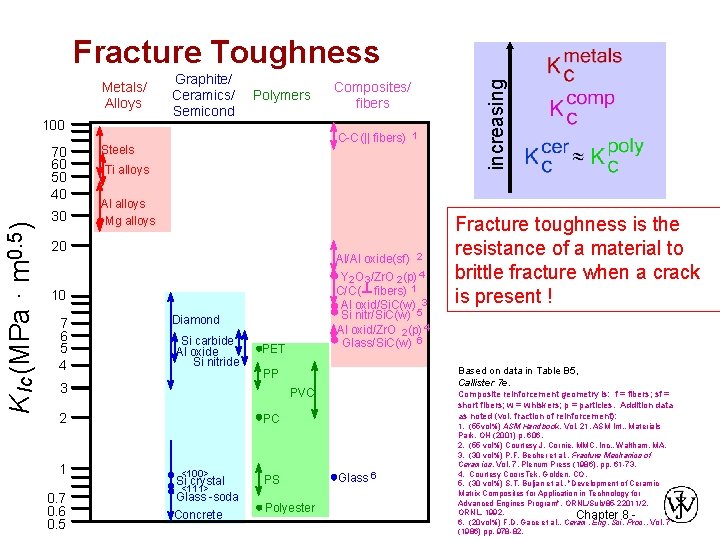

Metals/ Alloys 100 K Ic (MPa · m 0. 5 ) 70 60 50 40 30 Graphite/ Ceramics/ Semicond Polymers C-C(|| fibers) 1 Steels Ti alloys Al alloys Mg alloys 20 Al/Al oxide(sf) 2 Y 2 O 3 /Zr. O 2 (p) 4 C/C( fibers) 1 Al oxid/Si. C(w) 3 Si nitr/Si. C(w) 5 Al oxid/Zr. O 2 (p) 4 Glass/Si. C(w) 6 10 7 6 5 4 Diamond Si carbide Al oxide Si nitride 3 0. 7 0. 6 0. 5 PET Composite reinforcement geometry is: f = fibers; sf = short fibers; w = whiskers; p = particles. Addition data as noted (vol. fraction of reinforcement): PC <100> Si crystal <111> Glass -soda Concrete PS Polyester Fracture toughness is the resistance of a material to brittle fracture when a crack is present ! Based on data in Table B 5, Callister 7 e. PP PVC 2 1 Composites/ fibers increasing Fracture Toughness Glass 6 1. (55 vol%) ASM Handbook, Vol. 21, ASM Int. , Materials Park, OH (2001) p. 606. 2. (55 vol%) Courtesy J. Cornie, MMC, Inc. , Waltham, MA. 3. (30 vol%) P. F. Becher et al. , Fracture Mechanics of Ceramics, Vol. 7, Plenum Press (1986). pp. 61 -73. 4. Courtesy Coors. Tek, Golden, CO. 5. (30 vol%) S. T. Buljan et al. , "Development of Ceramic Matrix Composites for Application in Technology for Advanced Engines Program", ORNL/Sub/85 -22011/2, ORNL, 1992. Chapter 8 6. (20 vol%) F. D. Gace et al. , Ceram. Eng. Sci. Proc. , Vol. 7 (1986) pp. 978 -82.

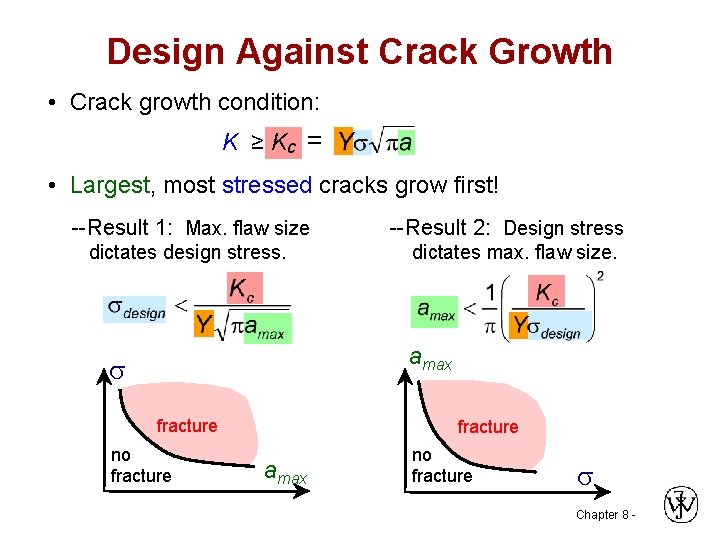

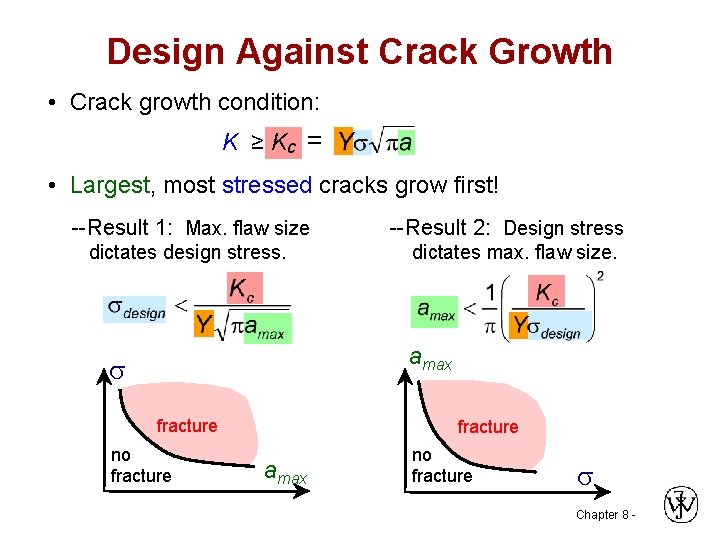

Design Against Crack Growth • Crack growth condition: K ≥ Kc = • Largest, most stressed cracks grow first! --Result 1: Max. flaw size dictates design stress. --Result 2: Design stress dictates max. flaw size. amax s fracture no fracture amax no fracture s Chapter 8 -

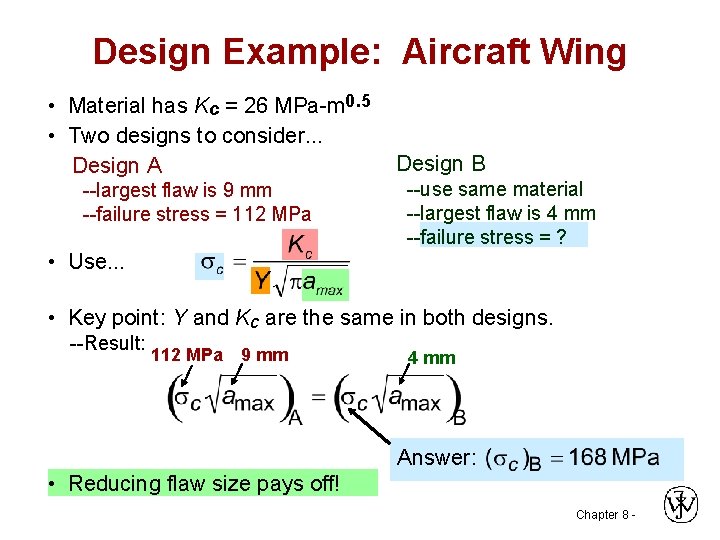

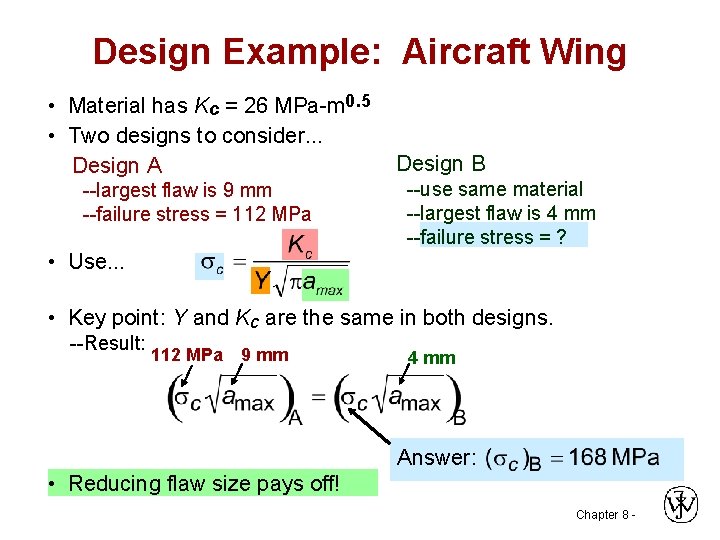

Design Example: Aircraft Wing • Material has Kc = 26 MPa-m 0. 5 • Two designs to consider. . . Design A --largest flaw is 9 mm --failure stress = 112 MPa Design B --use same material --largest flaw is 4 mm --failure stress = ? • Use. . . • Key point: Y and Kc are the same in both designs. --Result: 112 MPa 9 mm 4 mm Answer: • Reducing flaw size pays off! Chapter 8 -

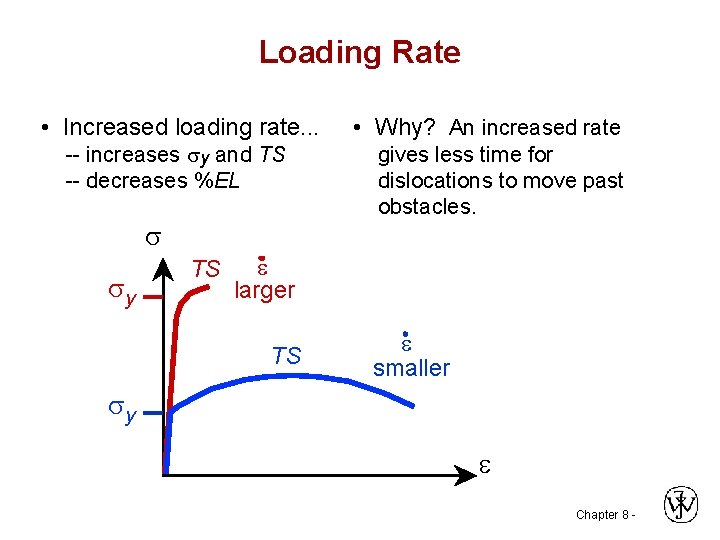

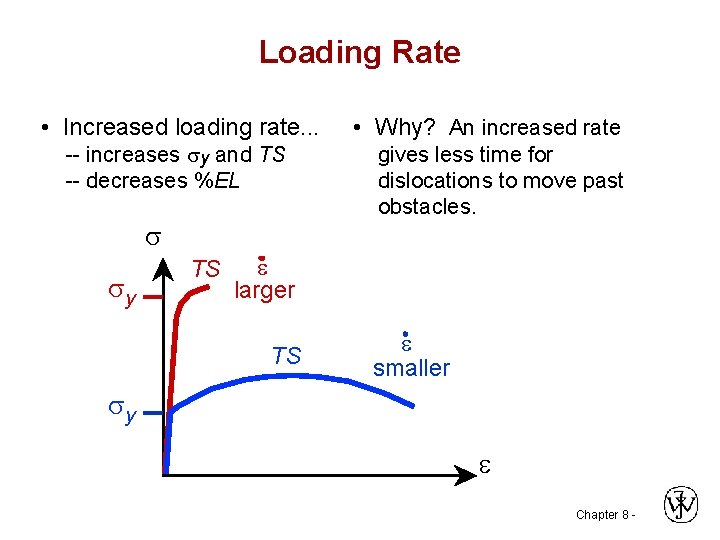

Loading Rate • Increased loading rate. . . -- increases sy and TS -- decreases %EL s sy TS • Why? An increased rate gives less time for dislocations to move past obstacles. e larger TS e smaller sy e Chapter 8 -

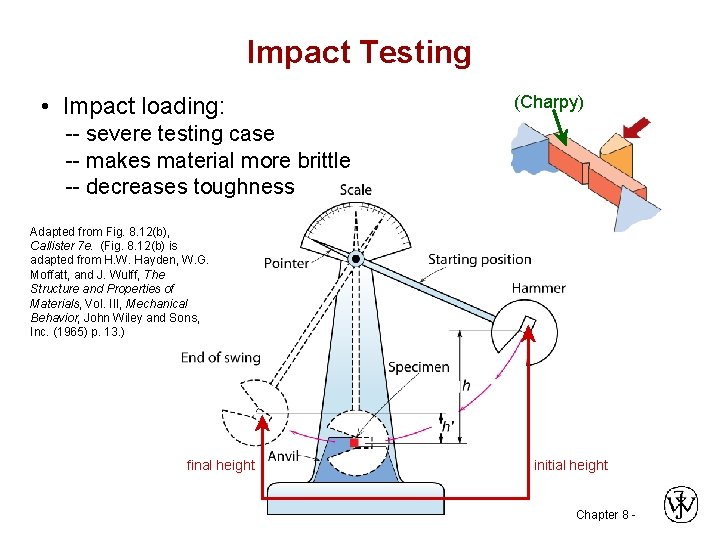

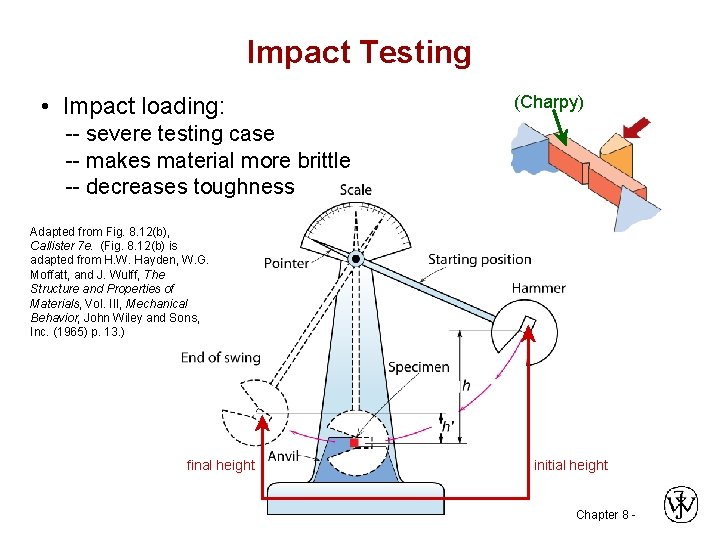

Impact Testing • Impact loading: (Charpy) -- severe testing case -- makes material more brittle -- decreases toughness Adapted from Fig. 8. 12(b), Callister 7 e. (Fig. 8. 12(b) is adapted from H. W. Hayden, W. G. Moffatt, and J. Wulff, The Structure and Properties of Materials, Vol. III, Mechanical Behavior, John Wiley and Sons, Inc. (1965) p. 13. ) final height initial height Chapter 8 -

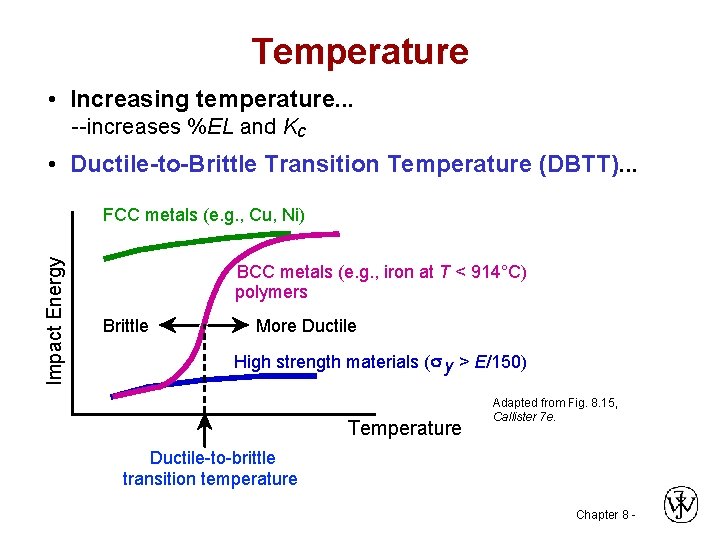

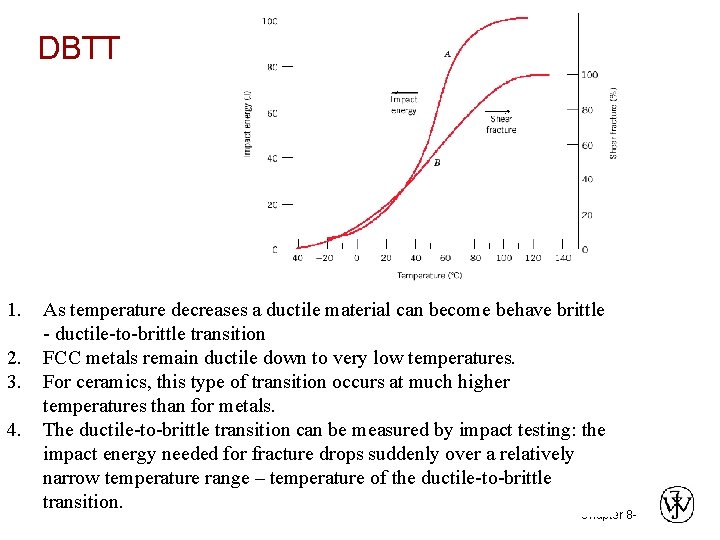

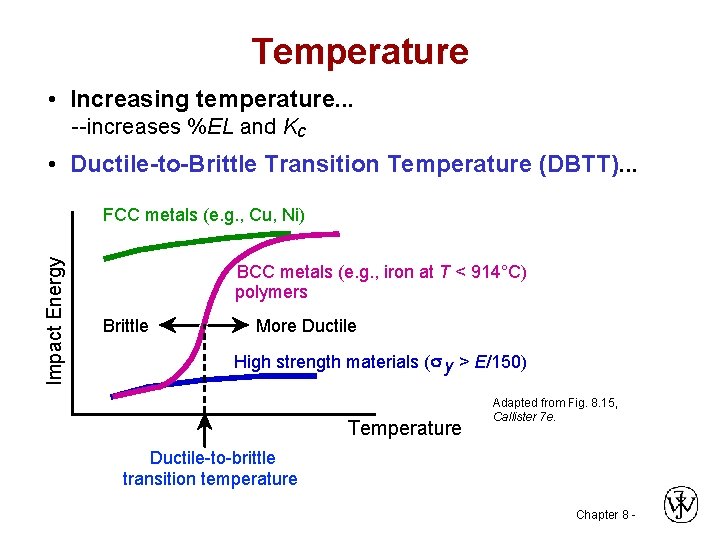

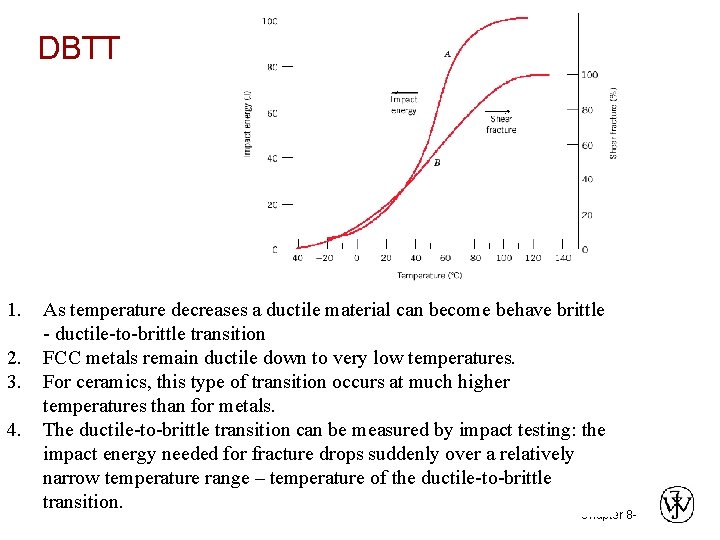

Temperature • Increasing temperature. . . --increases %EL and Kc • Ductile-to-Brittle Transition Temperature (DBTT). . . Impact Energy FCC metals (e. g. , Cu, Ni) BCC metals (e. g. , iron at T < 914°C) polymers Brittle More Ductile High strength materials ( y > E/150) Temperature Adapted from Fig. 8. 15, Callister 7 e. Ductile-to-brittle transition temperature Chapter 8 -

DBTT 1. 2. 3. 4. As temperature decreases a ductile material can become behave brittle - ductile-to-brittle transition FCC metals remain ductile down to very low temperatures. For ceramics, this type of transition occurs at much higher temperatures than for metals. The ductile-to-brittle transition can be measured by impact testing: the impact energy needed for fracture drops suddenly over a relatively narrow temperature range – temperature of the ductile-to-brittle transition. Chapter 8 -

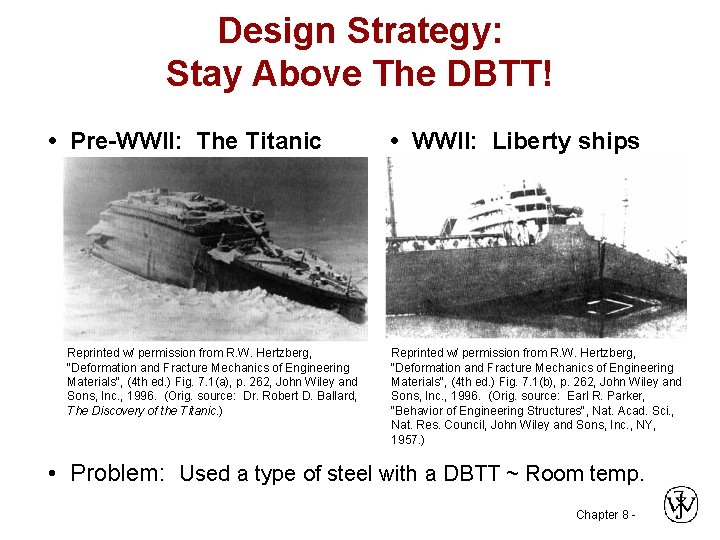

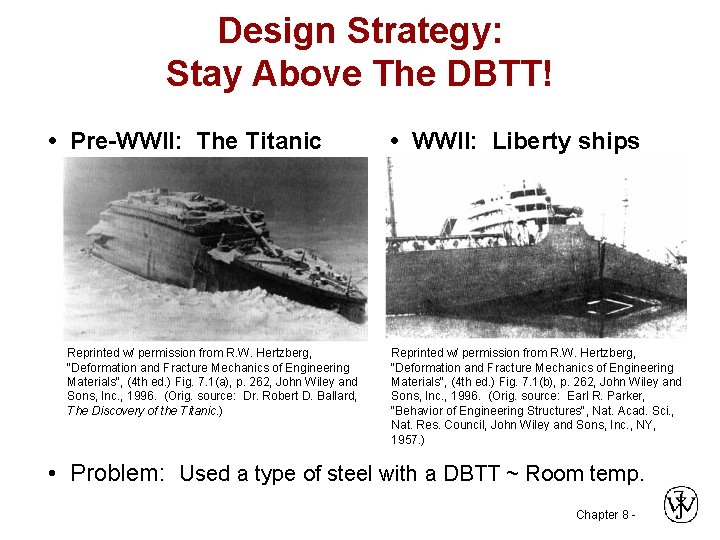

Design Strategy: Stay Above The DBTT! • Pre-WWII: The Titanic Reprinted w/ permission from R. W. Hertzberg, "Deformation and Fracture Mechanics of Engineering Materials", (4 th ed. ) Fig. 7. 1(a), p. 262, John Wiley and Sons, Inc. , 1996. (Orig. source: Dr. Robert D. Ballard, The Discovery of the Titanic. ) • WWII: Liberty ships Reprinted w/ permission from R. W. Hertzberg, "Deformation and Fracture Mechanics of Engineering Materials", (4 th ed. ) Fig. 7. 1(b), p. 262, John Wiley and Sons, Inc. , 1996. (Orig. source: Earl R. Parker, "Behavior of Engineering Structures", Nat. Acad. Sci. , Nat. Res. Council, John Wiley and Sons, Inc. , NY, 1957. ) • Problem: Used a type of steel with a DBTT ~ Room temp. Chapter 8 -

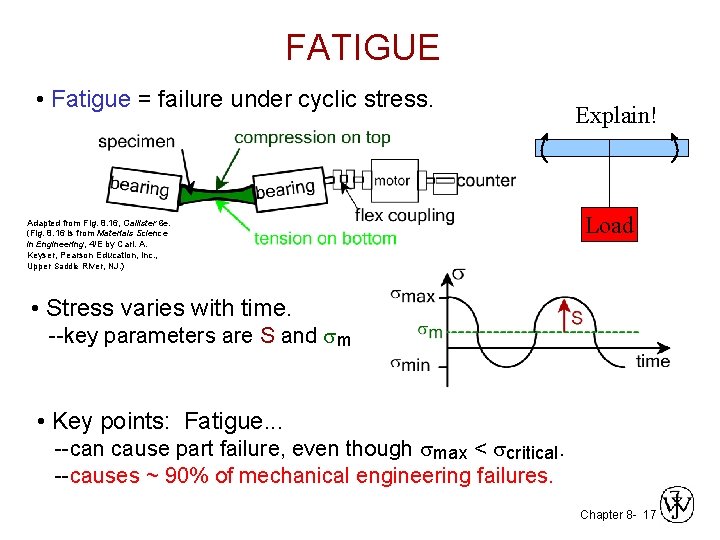

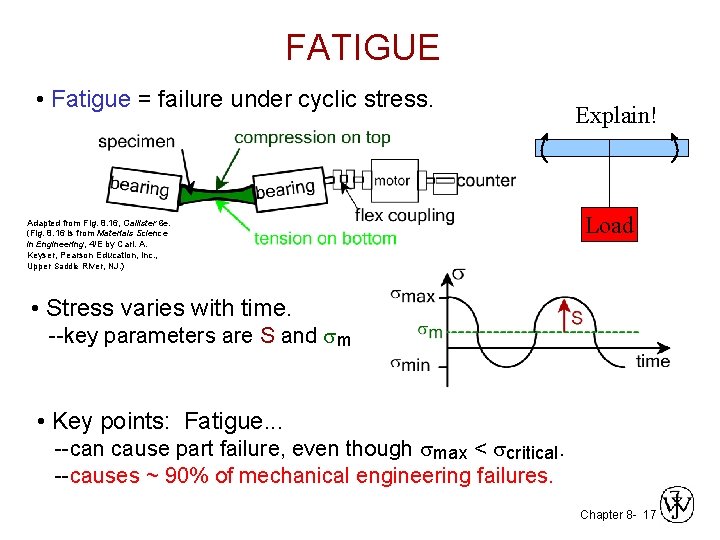

FATIGUE • Fatigue = failure under cyclic stress. Adapted from Fig. 8. 16, Callister 6 e. (Fig. 8. 16 is from Materials Science in Engineering, 4/E by Carl. A. Keyser, Pearson Education, Inc. , Upper Saddle River, NJ. ) Explain! Load • Stress varies with time. --key parameters are S and sm • Key points: Fatigue. . . --can cause part failure, even though smax < scritical. --causes ~ 90% of mechanical engineering failures. Chapter 8 - 17

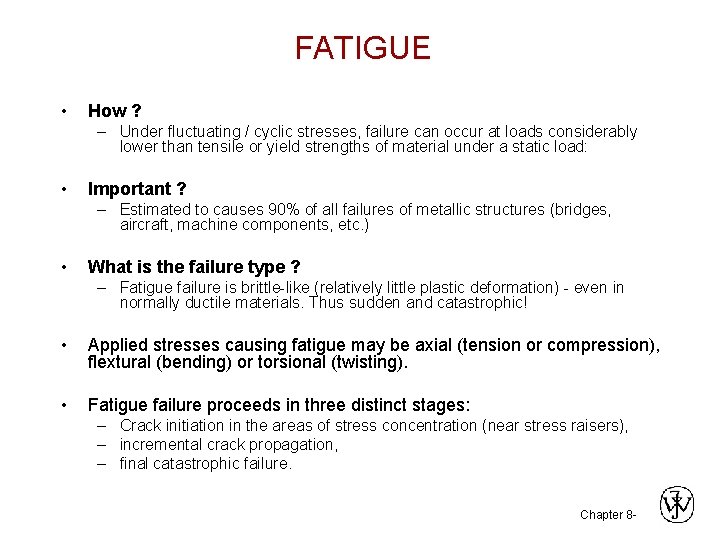

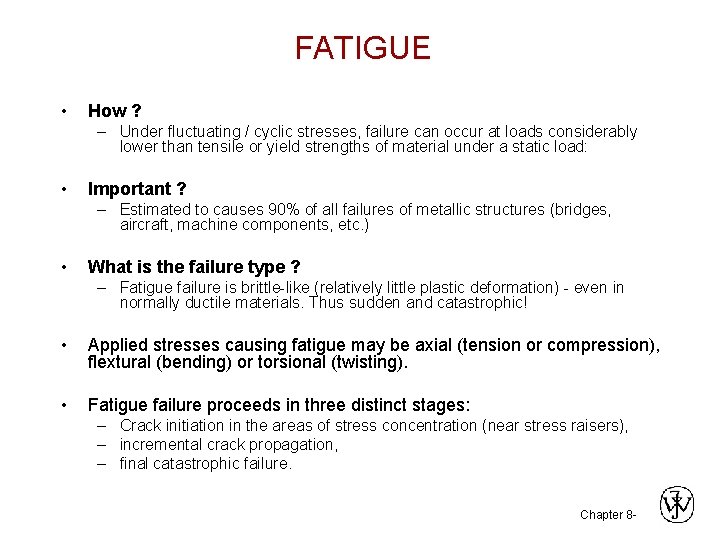

FATIGUE • How ? – Under fluctuating / cyclic stresses, failure can occur at loads considerably lower than tensile or yield strengths of material under a static load: • Important ? – Estimated to causes 90% of all failures of metallic structures (bridges, aircraft, machine components, etc. ) • What is the failure type ? – Fatigue failure is brittle-like (relatively little plastic deformation) - even in normally ductile materials. Thus sudden and catastrophic! • Applied stresses causing fatigue may be axial (tension or compression), flextural (bending) or torsional (twisting). • Fatigue failure proceeds in three distinct stages: – Crack initiation in the areas of stress concentration (near stress raisers), – incremental crack propagation, – final catastrophic failure. Chapter 8 -

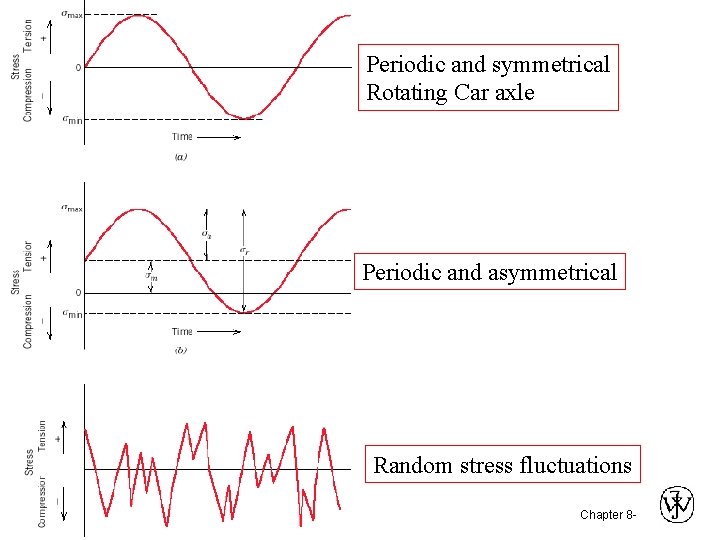

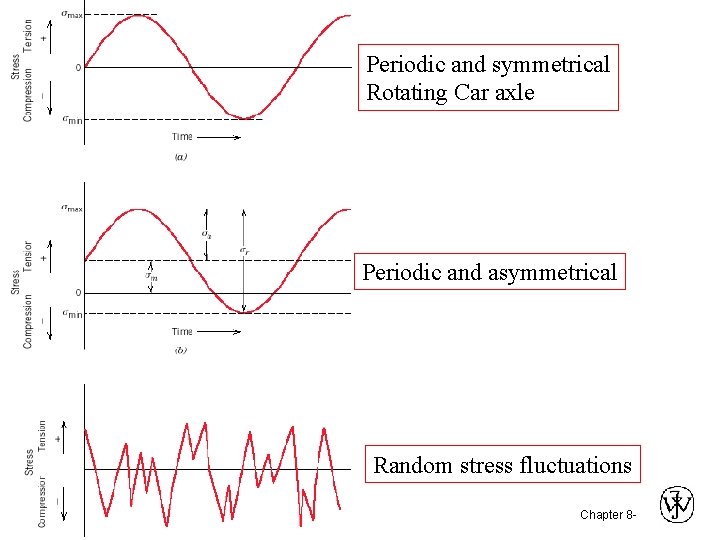

Periodic and symmetrical Rotating Car axle Periodic and asymmetrical Random stress fluctuations Chapter 8 -

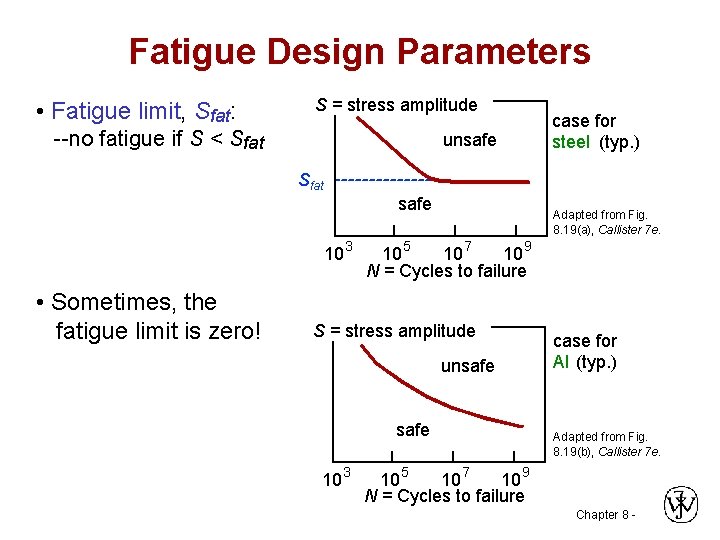

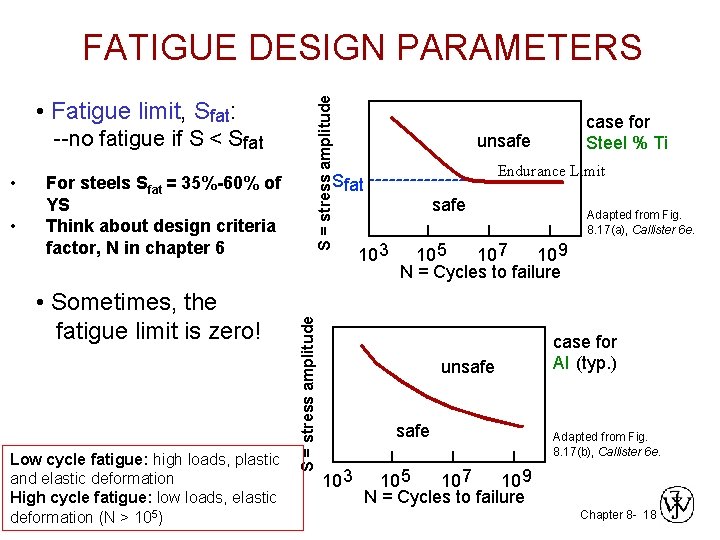

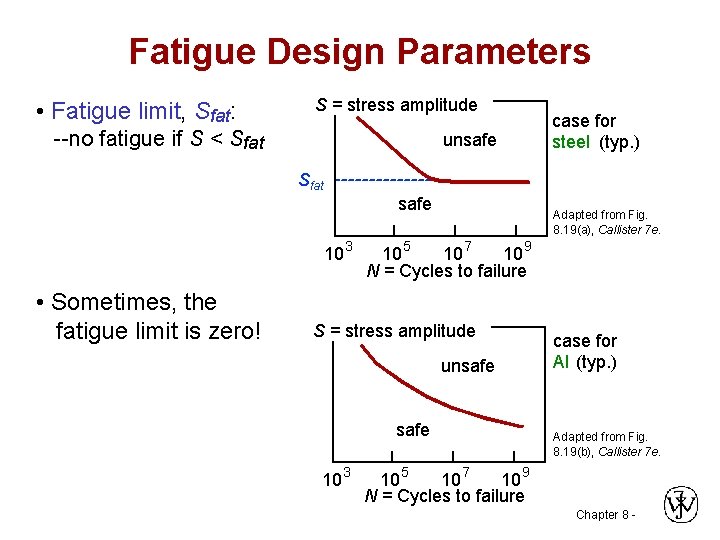

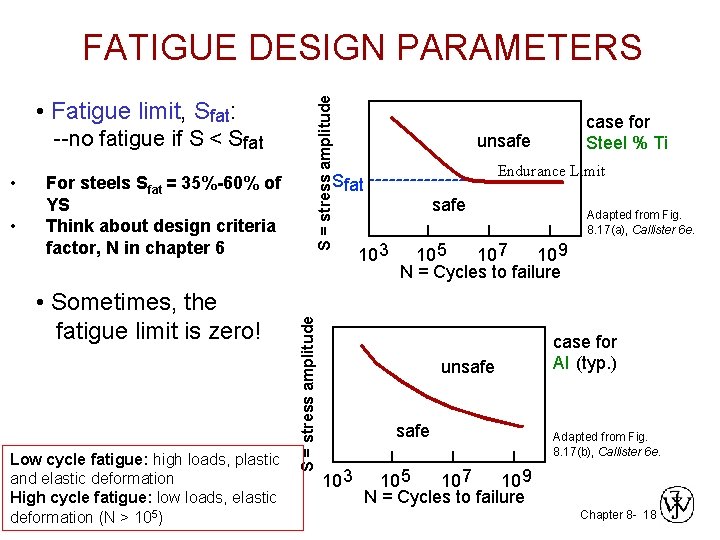

Fatigue Design Parameters • Fatigue limit, Sfat: S = stress amplitude --no fatigue if S < Sfat unsafe case for steel (typ. ) Sfat safe 10 3 • Sometimes, the fatigue limit is zero! Adapted from Fig. 8. 19(a), Callister 7 e. 10 5 10 7 10 9 N = Cycles to failure S = stress amplitude unsafe 10 3 case for Al (typ. ) Adapted from Fig. 8. 19(b), Callister 7 e. 10 5 10 7 10 9 N = Cycles to failure Chapter 8 -

--no fatigue if S < Sfat • • For steels Sfat = 35%-60% of YS Think about design criteria factor, N in chapter 6 • Sometimes, the fatigue limit is zero! Low cycle fatigue: high loads, plastic and elastic deformation High cycle fatigue: low loads, elastic deformation (N > 105) Endurance Limit safe 10 3 Adapted from Fig. 8. 17(a), Callister 6 e. 10 5 10 7 10 9 N = Cycles to failure unsafe 10 3 case for Steel % Ti unsafe Sfat S = stress amplitude • Fatigue limit, Sfat: S = stress amplitude FATIGUE DESIGN PARAMETERS case for Al (typ. ) Adapted from Fig. 8. 17(b), Callister 6 e. 10 5 10 7 10 9 N = Cycles to failure Chapter 8 - 18

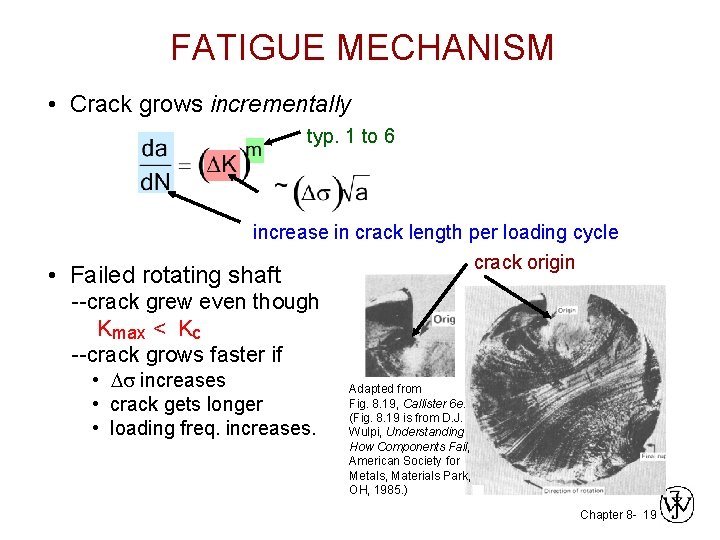

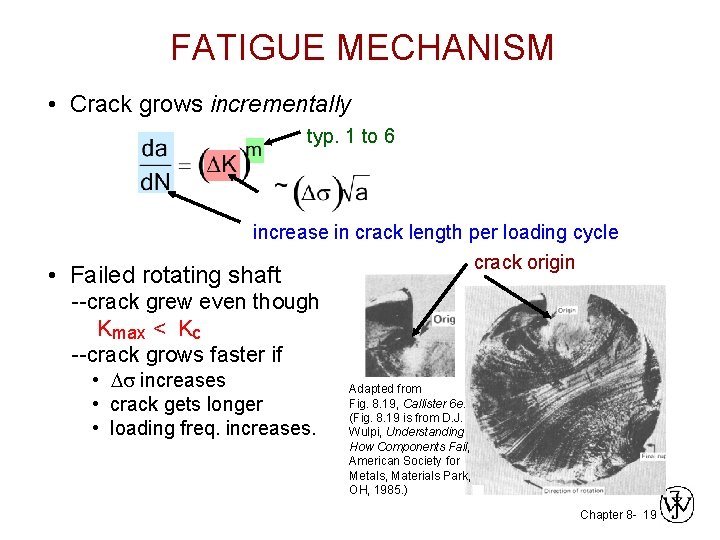

FATIGUE MECHANISM • Crack grows incrementally typ. 1 to 6 increase in crack length per loading cycle crack origin • Failed rotating shaft --crack grew even though Kmax < Kc --crack grows faster if • Ds increases • crack gets longer • loading freq. increases. Adapted from Fig. 8. 19, Callister 6 e. (Fig. 8. 19 is from D. J. Wulpi, Understanding How Components Fail, American Society for Metals, Materials Park, OH, 1985. ) Chapter 8 - 19

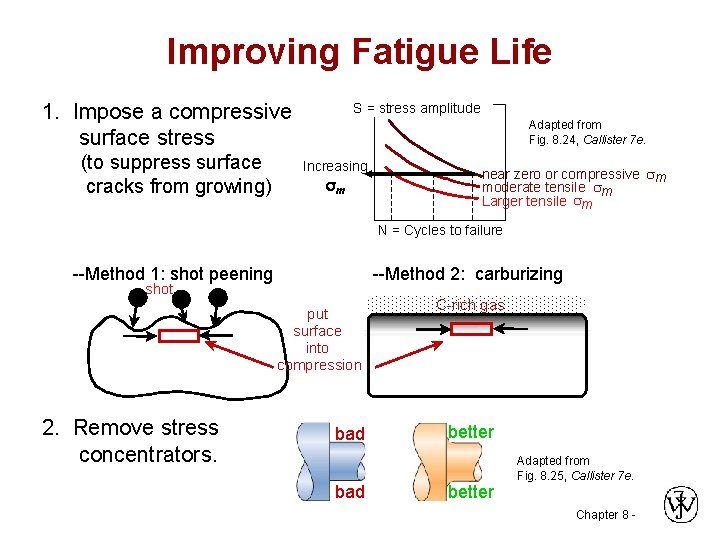

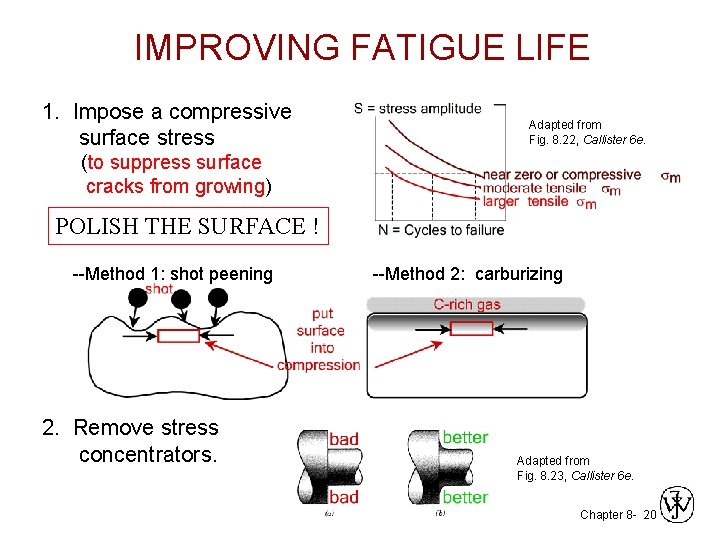

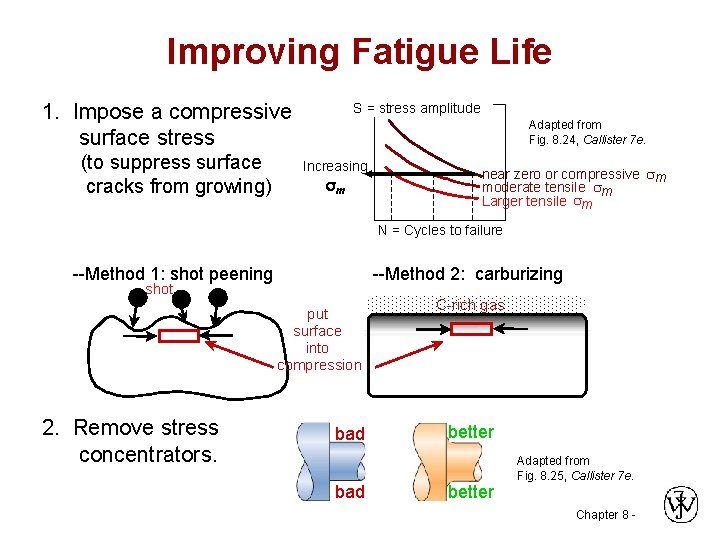

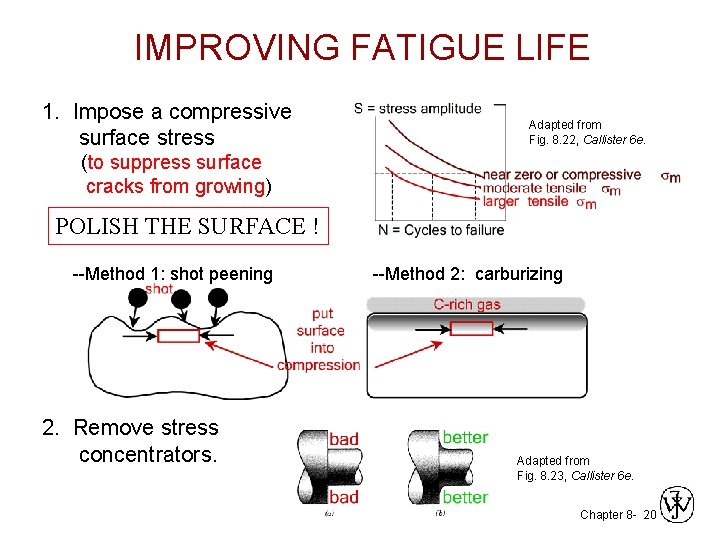

Improving Fatigue Life 1. Impose a compressive surface stress (to suppress surface cracks from growing) S = stress amplitude Adapted from Fig. 8. 24, Callister 7 e. Increasing m near zero or compressive sm moderate tensile sm Larger tensile sm N = Cycles to failure --Method 1: shot peening --Method 2: carburizing shot put surface into compression 2. Remove stress concentrators. bad C-rich gas better Adapted from Fig. 8. 25, Callister 7 e. Chapter 8 -

IMPROVING FATIGUE LIFE 1. Impose a compressive surface stress Adapted from Fig. 8. 22, Callister 6 e. (to suppress surface cracks from growing) POLISH THE SURFACE ! --Method 1: shot peening 2. Remove stress concentrators. --Method 2: carburizing Adapted from Fig. 8. 23, Callister 6 e. Chapter 8 - 20

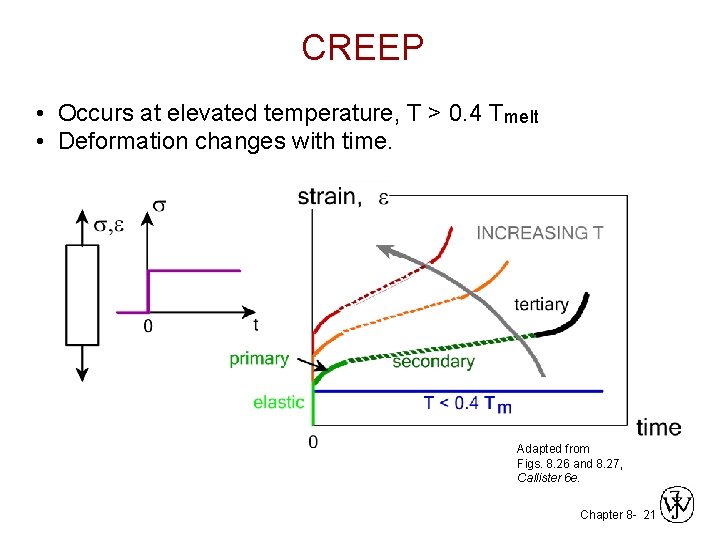

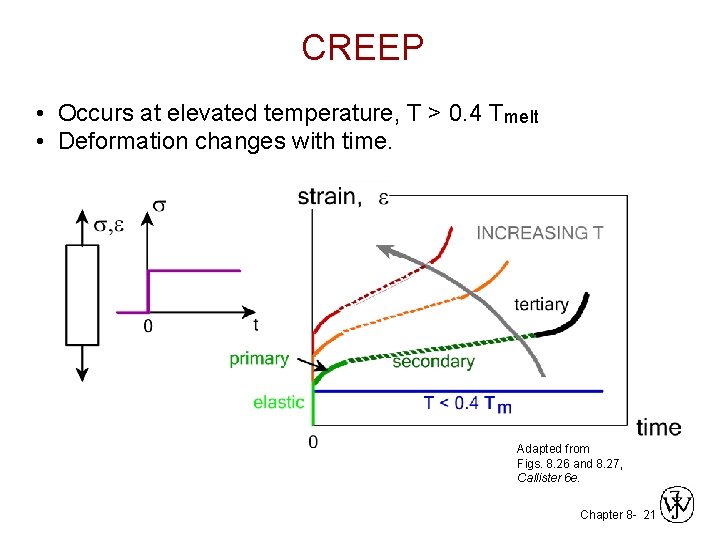

CREEP • Occurs at elevated temperature, T > 0. 4 Tmelt • Deformation changes with time. Adapted from Figs. 8. 26 and 8. 27, Callister 6 e. Chapter 8 - 21

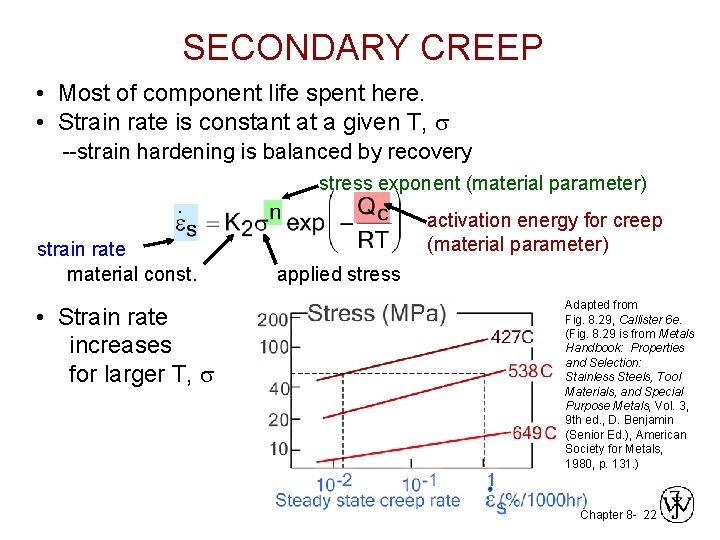

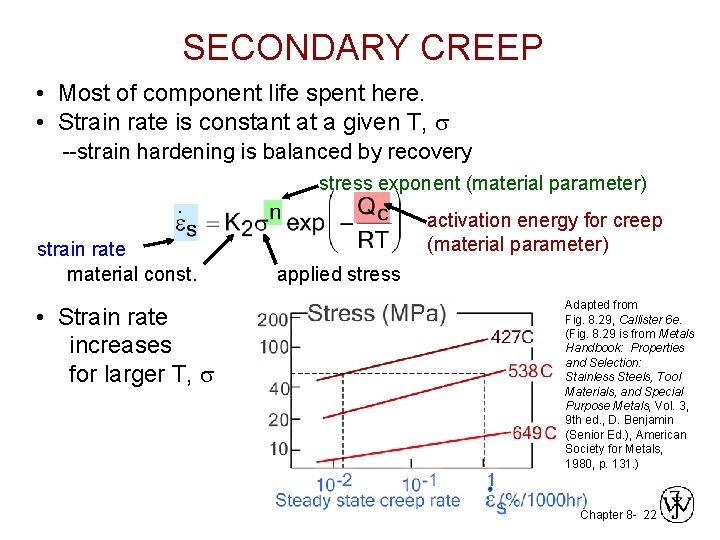

SECONDARY CREEP • Most of component life spent here. • Strain rate is constant at a given T, s --strain hardening is balanced by recovery . strain rate material const. • Strain rate increases for larger T, s stress exponent (material parameter) activation energy for creep (material parameter) applied stress Adapted from Fig. 8. 29, Callister 6 e. (Fig. 8. 29 is from Metals Handbook: Properties and Selection: Stainless Steels, Tool Materials, and Special Purpose Metals, Vol. 3, 9 th ed. , D. Benjamin (Senior Ed. ), American Society for Metals, 1980, p. 131. ) Chapter 8 - 22

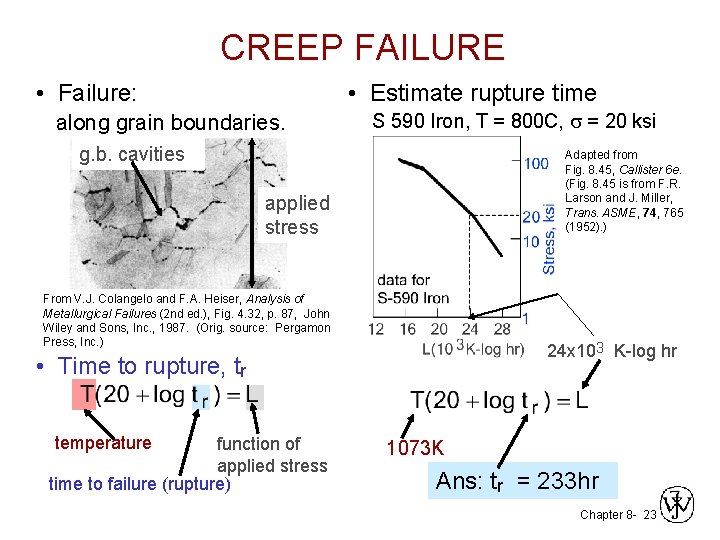

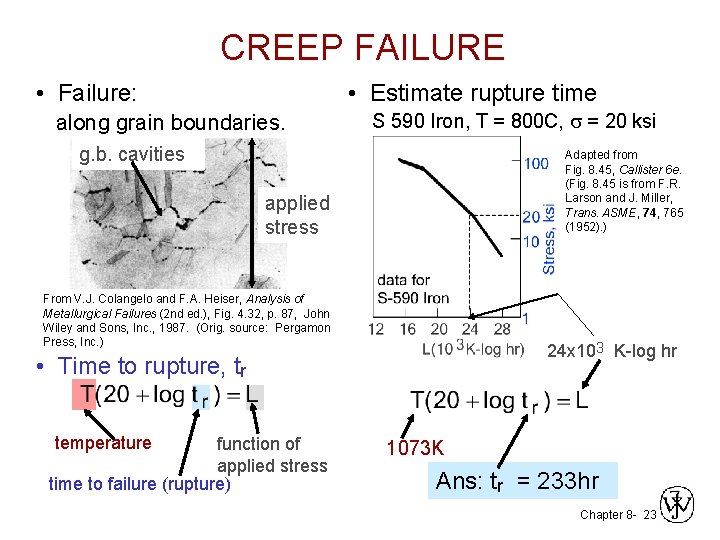

CREEP FAILURE • Failure: • Estimate rupture time along grain boundaries. S 590 Iron, T = 800 C, s = 20 ksi g. b. cavities Adapted from Fig. 8. 45, Callister 6 e. (Fig. 8. 45 is from F. R. Larson and J. Miller, Trans. ASME, 74, 765 (1952). ) applied stress From V. J. Colangelo and F. A. Heiser, Analysis of Metallurgical Failures (2 nd ed. ), Fig. 4. 32, p. 87, John Wiley and Sons, Inc. , 1987. (Orig. source: Pergamon Press, Inc. ) 24 x 103 K-log hr • Time to rupture, tr temperature function of applied stress time to failure (rupture) 1073 K Ans: tr = 233 hr Chapter 8 - 23

SUMMARY (I) • Engineering materials don't reach theoretical strength. • Flaws produce stress concentrations that cause premature failure. • Sharp corners produce large stress concentrations and premature failure. • Failure type depends on T and stress: -for noncyclic s and T < 0. 4 Tm, failure stress decreases with: increased maximum flaw size, decreased T, increased rate of loading. -for cyclic s: cycles to fail decreases as Ds increases. -for higher T (T > 0. 4 Tm): time to fail decreases as s or T increases. Chapter 8 - 24

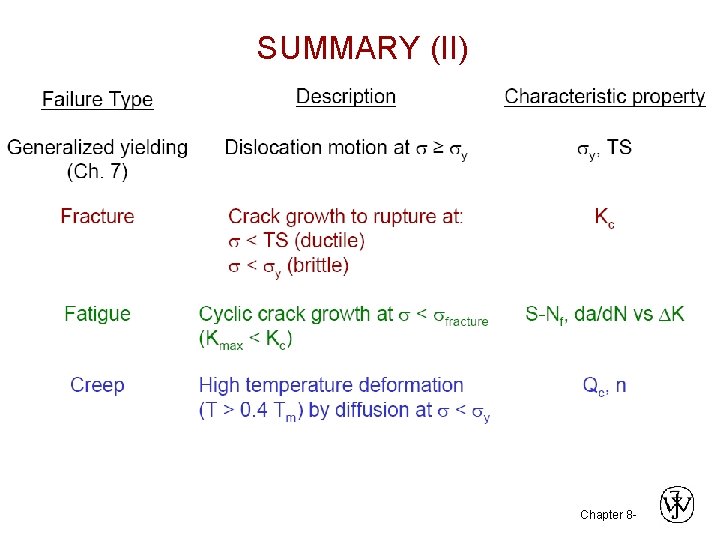

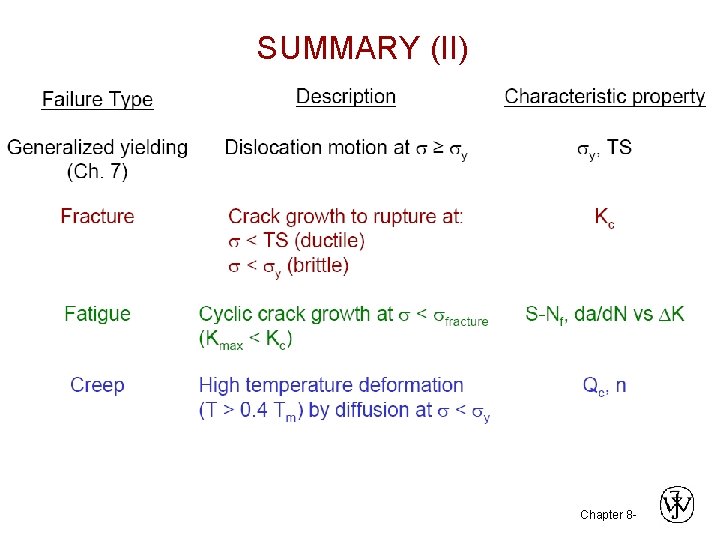

SUMMARY (II) Chapter 8 -

ANNOUNCEMENTS Reading: Chapter 8 and Chapter 9 at least twice ! Use the CD and review Chapter 7 and 8 ! Core Problems: 8. 7, 8. 10, 8. 13, 8. 17, 8. 22 Self-help Problems: 8. 1, 8. 2, 8. 3, 8. 15, 8. 20, 8. 21 Homework due 23 Nov. 2006 Chapter 8 - 0