Chapter 8 Experimental Studies in Epidemiology Objectives Discuss

Chapter 8 Experimental Studies in Epidemiology

Objectives �Discuss the role of randomization in controlled trials �Discuss the role of blinding in controlled trials �Identify the general strengths and weaknesses of controlled trials �Identify the advantages to using a run-in design, a factorial design, a randomized matched pair design, or a group-randomized design �Discuss some of the ethical issues associated with experimental studies

Epidemiologic Experimental Studies �Resemble controlled experiments performed in scientific research �Best reserved for relatively mature questions �Best for establishing cause-effect relationships and for evaluating the efficacy of prevention and therapeutic interventions

Experimental Studies �Also called intervention studies �Investigators influence the exposure of the study subjects �Two types of experimental trials �Controlled trials �Community trials

Between-Group Design �The strongest methodological design is a betweengroup design, where outcomes are compared between two or more groups of people receiving different levels of the intervention

Within-Group Design �May be used where the outcome in a single group is compared before and after the assignment of an intervention �Strength – Individual characteristics that might confound an association (e. g. , gender, race, genetic susceptibility) are controlled �Weakness – Susceptible to confounding from time-related factors such as the media but may be adjusted for in the analysis

Controlled Trial �The unit of analysis is the individual �A randomized controlled trial in a clinical setting is referred to as a clinical trial

Community Trial �The unit of analysis is the group or community �An experimental epidemiologic study where one group of people, or one community, receives an intervention and another does not is a community trial

Natural Experiment �In some rare situations in nature, unplanned events produce a natural experiment �Levels of exposure to a presumed cause differ among a population in a way that is relatively unaffected by extraneous factors so that the situation resembles a planned experiment

Example of Natural Experiment �Screening and treatment for prostate cancer in the Seattle-Puget Sound area differed considerably from that in Connecticut during 1987 -90 �Specifically, prostate-specific antigen testing was 5. 39 (95% confidence interval: 4. 76 to 6. 11) times higher in Seattle than in Connecticut, and the prostate biopsy rate was 2. 20 (1. 81 to 2. 68) times higher than in Connecticut

Example of Natural Experiment �Ten-year cumulative incidences of radical prostatectomy and external beam radiation up to 1996 were � 2. 7% and 3. 9% for those in Seattle � 0. 5% and 3. 1% for those in Connecticut

Example of Natural Experiment �Did mortality from prostate cancer from 1987 to 1997 differ between Seattle and Connecticut? �The adjusted rate ratio of prostate cancer mortality during the study period for Seattle vs. Connecticut was 1. 03 (0. 95 to 1. 11) �In other words, the 11 -year follow-up data showed no difference in prostate cancer mortality between the two areas, despite much more intensive screening and treatment in Seattle

Experimental Studies �Experimental studies may be �Between-group designs �Within-group designs

Between Group Design �When a comparison is made between outcomes observed in two or more groups of subjects that receive different levels of the intervention, we call this a between-group design

Within Group Design �When we compare the outcomes observed in a single group before and after the intervention, it is called a within-group design

Random Assignment �Random assignment makes intervention and control groups look as similar as possible �Chance is the only factor that determines group assignment �Neither the patient or the physician know in advance which prevention program or therapy will be assigned �Confounding and sample size

Non-Randomized Study �Also called convenience sample �Concurrent comparison group is allocated by a non-random process �Assignment �Problems � Not effective at controlling unmeasured confounding variables � Measured confounding variables; however, may be adjusted through analytic methods

Advantages and disadvantages of randomized controlled clinical trials �Advantages of randomization �Eliminates conscious bias due to physician or patient selection �Averages out unconscious bias due to unknown factors �Groups are “alike on average” �Disadvantages of randomization �Ethical issues �Interferes with the doctor-patient relationship

Blinding �Three levels of blinding �Single blind – Subjects �Double blind – Investigators �Triple blind – Analyses

Single-Blinded Study �In a single-blinded placebo-controlled study, the subjects are blinded but investigators are aware of who is receiving the active treatment

Double-Blinded Study �In a double-blind study, neither the subjects nor the investigators know who is receiving the active treatment

Triple-Blinded Study � In a triple-blind study, not only are the treatment and research approaches kept a secret from the subjects and investigators, but the analyses are completed in a manner that is removed from the investigators

Blinding Patients �Why blind patients? �Patients try to get well/please physicians �Minimize potential bias from a placebo effect �A placebo effect is defined as the effect on patient outcomes (improved or worsened) that may occur due to the expectation by a patient (or provider) that a particular intervention will have an effect

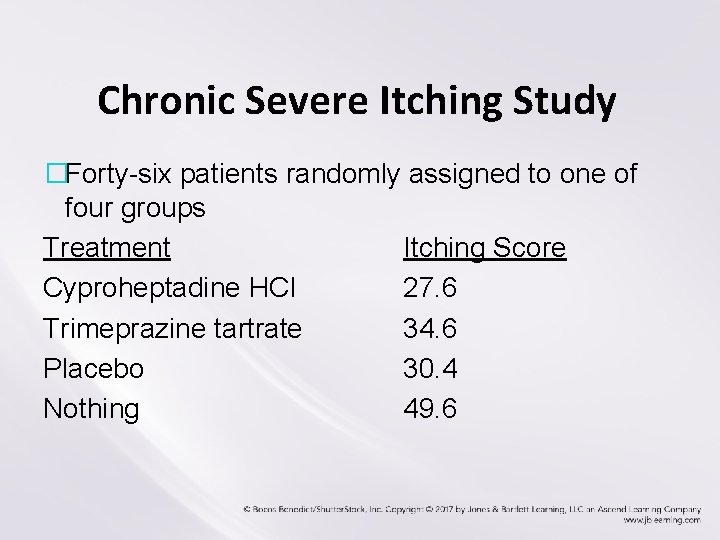

Chronic Severe Itching Study �Forty-six patients randomly assigned to one of four groups Treatment Itching Score Cyproheptadine HCI 27. 6 Trimeprazine tartrate 34. 6 Placebo 30. 4 Nothing 49. 6

Blinding Patients �To blind patients, use a placebo; for example, �Pill of same size, color, shape as treatment �Sham operation (anesthesia and incision) for angina relief (unethical) �Problems �In non-drug studies may be impossible/unethical �In drug studies if treatment has characteristic side effects

Blinding Patients �More subjective outcomes call for more serious consideration of placebo �For example, time to death vs. pain relief �Placebos improve comparability of treatment groups in terms of compliance and follow-up �For example, if patient perceives improvement because of medication, more likely to remain in study

Blinding physician or outcome assessing investigator �Best way to avoid unconscious bias is to blind �Physicians – don’t know which patient is taking the placebo and which patient is taking the drug �Assessors – of the outcome; are not the treating doctors, and are not told which treatment was used �What if physician blinding is not possible (e. g. , surgery or radiation trial)?

Problems with Blinding �For non-drug studies, such as those involving behavior changes or surgery, it may be impossible or unethical to blind �It may also be problematic to blind in drug studies where a treatment has characteristic side effects

Purpose of Experimental Studies �To identify clinical and public health approaches to solving public health problems (how to prevent or treat)

Strengths of blinded randomized controlled clinical trials �Demonstrate cause-effect relationships �May produce a faster and cheaper answer than observational studies �Only appropriate approach for some research questions �Allow investigators to control the exposure levels as needed

Weaknesses of blinded randomized controlled clinical trials �Often more costly in time and money �Many research questions are not suitable for experimental designs because of ethical barriers and because of rare outcomes �Many research questions are not suitable for blinding �Standardized interventions may be different from common practice �May have limited generalizability due to the use of volunteers, eligibility criteria, and loss to follow-up

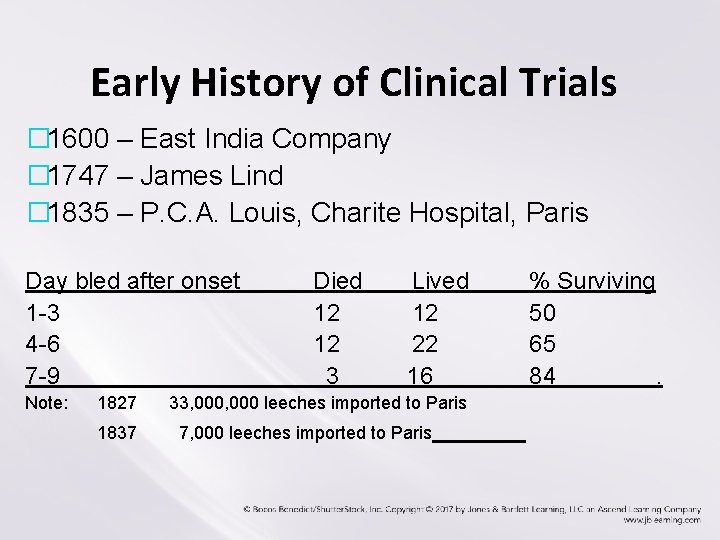

Early History of Clinical Trials � 1600 – East India Company � 1747 – James Lind � 1835 – P. C. A. Louis, Charite Hospital, Paris Day bled after onset 1 -3 4 -6 7 -9 Note: 1827 1837 Died 12 12 3 Lived 12 22 16 33, 000 leeches imported to Paris 7, 000 leeches imported to Paris % Surviving 50 65 84.

Designing a Clinical Trial �Assembling study cohort �Measuring baseline variables �Choosing comparison group �Assuring compliance �Selecting treatment �Selecting patient population �Selecting outcome (endpoint) �Ethical considerations

Assembling Study Cohort �Inclusion criteria �Broad vs. specific – related to the extent of generalization �Is the outcome rare (e. g. , CHD incidence)? Then recruit from populations at high risk such as males.

Assembling Study Cohort �Exclusion criteria �Define exclusion criteria that will help control error. � Example: An advanced cancer that may be fatal before the end of the follow-up period in a subject entering a CHD-prevention study �Exclude those with difficulty in complying �Examples: Alcoholics, psychotic patients, individuals planning to move out of state �Sample size

Measuring Baseline Variables �Characterize the study cohort �Identifying information (name, address, ID#) �Demographics (age, race, gender, etc. ) �Clinical factors �The first table of a final report of any randomized blinded trial typically compares the level of baseline characteristics in the two study groups

Measuring Baseline Variables �Consider measuring the outcome variable �Change (appropriate for within-group design) �To assure disease is or is not present at baseline (appropriate for between-group design) �Measure various predictors of outcomes (e. g. , smoking habits) to allow for statistical adjustment �Be parsimonious (i. e. , keep simple)

Choosing Comparison Group �Not contaminated by treatment �Ideal – possible to blind, usually meaning placebo used �Status quo vs. new treatment

Assuring Compliance �Calling the day before clinical visit �Providing reimbursement �Adhering to the intervention protocol �Drug or behavioral intervention should be well tolerated �Taking once a day vs. complex schedule �Measuring compliance (self-report, pill counts, urinary metabolite levels)

Selecting Treatment �What is the research objective? �Are therapies safe and active against the disease? �Is there evidence that one therapy is better than another? �Is the intervention likely to be implemented in a clinical practice? �Is the intervention “strong” enough to have a chance of producing a detectable effect?

Selecting Patient Population � Often a compromise between 1. The population most efficient for answering the clinical question 2. The population best for generalizing the study findings � For example, many CHD-prevention trials do not include subjects over age 60 because such elderly subjects might already have extensive atheriosclerosis of their coronary arteries that would no longer be responsive to preventive efforts.

Selecting Outcomes (Endpoints) �Primary endpoint �For example, the primary endpoint for most phase III clinical trials in HIV disease is an AIDS-defining event or death � Major AIDS-defining events are: parasitic infections; fungal infections; bacterial infections; viral infections; neoplastic disease; HIV dementia; HIV wasting syndrome �Selection of the “best” endpoint is often complicated �Surrogate endpoint

Phase I Trial �Unblinded, uncontrolled study with typically fewer than 30 patients �The purpose of phase I trials is to determine the safety of a test in humans �Patients in phase I trials often have advanced disease and have already tried other options �They often undergo intense monitoring

Phase II Trial �Relatively small (up to 50 people) randomized blinded trials that test �Tolerability �Safe dosage �Side effects �How the body copes with the drug �Also evaluate which types of disease a treatment is effective against, further assess side effects and how they can be managed, and reveal the most effective dosage level

Phase III Trial �Typically much larger and may involve thousands of patients �These trials typically involve random assignment and are used to evaluate the efficacy of a new treatment �Different dosages or methods of administration of the treatment are often part of the evaluation

Phase IV Trial �A large study conducted after therapy has been approved by the FDA to assess the rate of serious side effects, and explore furtherapeutic uses

Selected special types of randomized designs �Basic randomized designs �Run-in designs �Factorial design �Randomization of matched pairs �Group randomization

Run-In Design �All subjects in the cohort are placed on placebo (or treatment), followed for some period of time (usually a week or two), and then those who have remained in the study are randomly assigned to either the treatment or placebo arms of the study �A limitation of this study design is that the subjects in the cohort at the time of randomization may no longer reflect the population of interest

Factorial Design �Subjects are randomly assigned to one of four groups. The groups represent the different combinations of the two interventions.

Randomization of Matched Pairs �Improves covariate balance on potential confounding variables �Matched randomization provides more accurate estimates than unmatched randomization, and may involve matching on several potential confounders

Randomization of Matched Pairs �Subjects are matched in pairs according to some confounding factor (e. g. , age, sex, race/ethnicity) �One subject is then randomly assigned the study group (e. g. , a dietary program, a drug) and the other is assigned to the comparison control group

Group Randomization �Groups or naturally forming clusters are randomly assigned the intervention �Groups may involve �Practices �Schools �Hospitals �Communities �Individuals or patients within a cluster are likely to be more similar to each other compared to those in other clusters

Summary of Ethical Principles �Benefits – Maximize good �Risks – Avoid doing harm �Subject – Respect for all persons �Society – Fairness to all �Is consent necessary? �Is it necessary to disclose to the subject the fact that they will be determined by chance? �Should subjects be compensated for injury? �Who should be permitted (or encouraged) to participate in clinical research? �When and how should a clinical trial be stopped?

Tuskegee Syphilis Study �The Tuskegee study had nothing to do with medical experiments �No treatment was offered for syphilis �No new drugs were tested, nor were any efforts made to establish the efficacy of older chemical treatments

Summary of Ethical Principles �Competent investigators and good research design lead to a greater likelihood of benefits, protect subjects from harm, ensure that peoples’ time is not wasted, and their desire to participate in a meaningful activity not frustrated. Source: Levine and Labacqz

- Slides: 55