Chapter 7 Representing Information Digitally Learning Objectives Explain

Chapter 7 Representing Information Digitally

Learning Objectives • Explain the link between patterns, symbols, and information • Compare two different encoding methods • Determine possible Pand. A encodings using a physical phenomenon • Give a bit sequence code for ASCII; decode • Represent numbers in binary form and hexadecimal • Explain how structure tags (metadata) encode the Oxford English Dictionary Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Digitizing Discrete Information • The dictionary definition of digitize is to represent information with digits. • Digit means the ten Arabic numerals 0 through 9. • Digitizing uses whole numbers to stand for things. Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

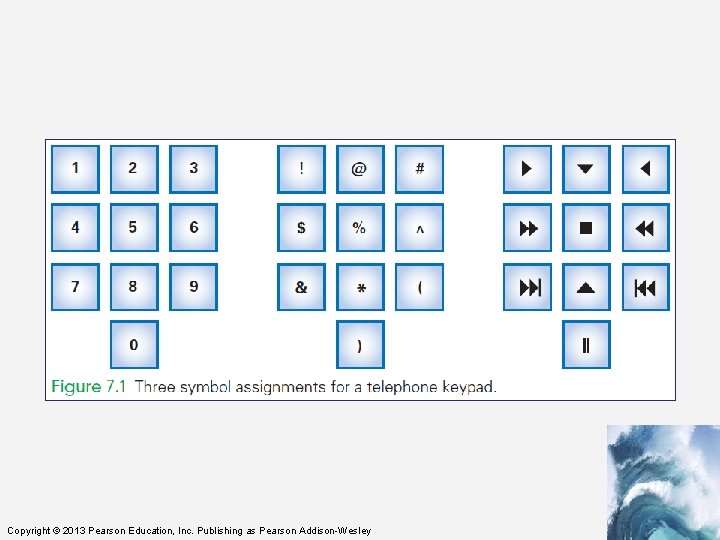

Limitation of Digits • A limitation of the dictionary definition of digitize is that it calls for the use of the ten digits, which produces a whole number • Alternative Representations – Digitizing in computing can use almost any symbols – Any ten distinct symbols will work as long as items are labeled properly. Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Symbols, Briefly • One practical advantage of digits is that digits have short names (one, two, nine) • Imagine speaking your phone number the multiple syllable names: – “asterisk, exclamation, closing parenthesis” • IT uses these symbols, but have given them shorter names: – exclamation point. . . is bang – asterisk. . . is star Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Ordering Symbols • Another advantage of digits is that the items can be listed in numerical order • Sometimes ordering items is useful • To place information in order by using nondigit symbols, we need to agree on an ordering for the basic symbols – This is called a collating sequence • Today, digitizing means representing information by symbols Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Fundamental Information Representation • The fundamental patterns used in computing come into play when the physical world meets the logical world • In the physical world, the most fundamental form of information is the presence or absence of a physical phenomenon Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Fundamental Information Representation • From a digital information point of view, the amount of a phenomenon is not important as long as it is reliably detected – Whethere is some information or none; – Whether it is present or absent • In the logical world, concepts of true and false are important Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Fundamental Information Representation • Logic is the foundation of reasoning • It is also the foundation of computing • The physical world can implement the logical world by associating “true” with the presence of a phenomenon and “false” with its absence Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

The Pand. A Representation • Pand. A is the name used for two fundamental patterns of digital information: – Presence – Absence • Pand. A is the mnemonic for “Presence and Absence” • A key property of Pand. A is that the phenomenon is either present or not Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

The Pand. A Representation • The presence or absence can be viewed as “true” or “false” • Such a formulation is said to be discrete • Discrete means “distinct” or “separable” – It is not possible to transform one value into another by tiny gradations – There are no “shades of gray” Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

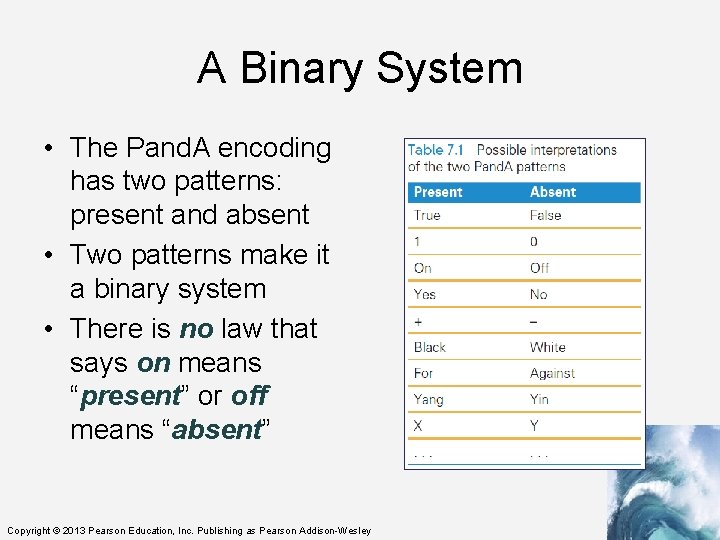

A Binary System • The Pand. A encoding has two patterns: present and absent • Two patterns make it a binary system • There is no law that says on means “present” or off means “absent” Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Bits Form Symbols • In the Pand. A representation, the unit is a specific place (in space and time), where the presence or absence of the phenomenon can be set and detected. • The Pand. A unit is known as a bit • Bit is a contraction for “binary digit” • Bit sequences can be interpreted as binary numbers • Groups of bits form symbols Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Bits in Computer Memory • Memory is arranged inside a computer in a very long sequence of bits • Going back to the definition of bits (previous slide), this means that places where the physical phenomenon encoding the information can be set and detected Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

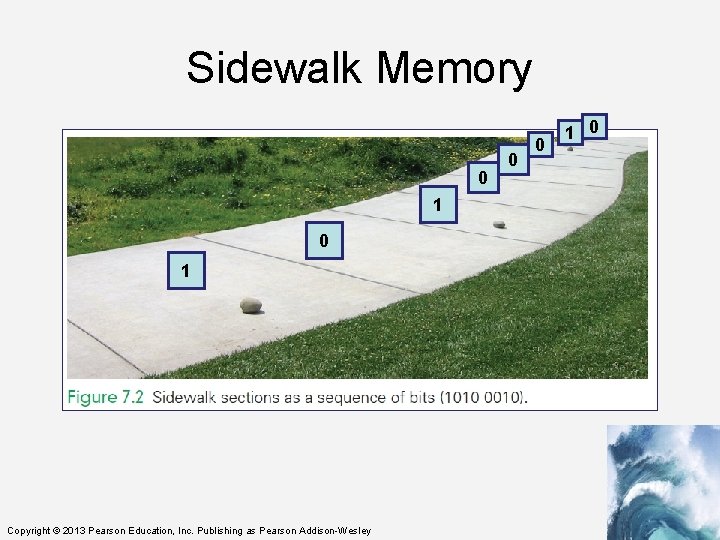

Sidewalk Memory • Imagine a clean sidewalk made of a strip of concrete with lines across it forming squares • The presence of a stone on a square corresponds to 1 • The absence of a stone corresponds to 0 • This makes the sidewalk a sequence of bits Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Sidewalk Memory 0 1 Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley 0 0 1 0

Sidewalk Memory • Bits can be set to write information into memory • Bits can be sensed to read the information out of memory – To write a 1, the phenomenon must be made to be present (put a stone on a square – To write a 0, the phenomenon must be made to be absent (sweep the sidewalk square clean) Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Alternative Pand. A Encodings • There is no limit to the ways to encode two physical states – stones on all squares, but with white (absent) and black (present) stones for the two states – multiple stones of two colors per square, more white stones than black means 1 and more black stones than white means 0 – And so forth Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

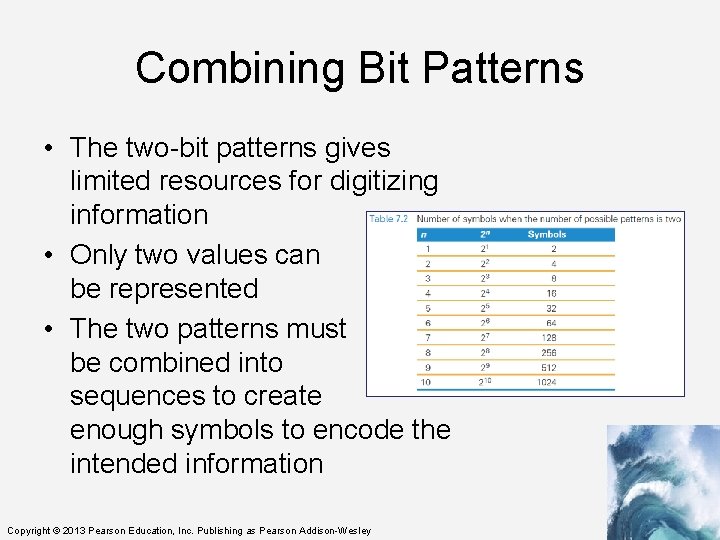

Combining Bit Patterns • The two-bit patterns gives limited resources for digitizing information • Only two values can be represented • The two patterns must be combined into sequences to create enough symbols to encode the intended information Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

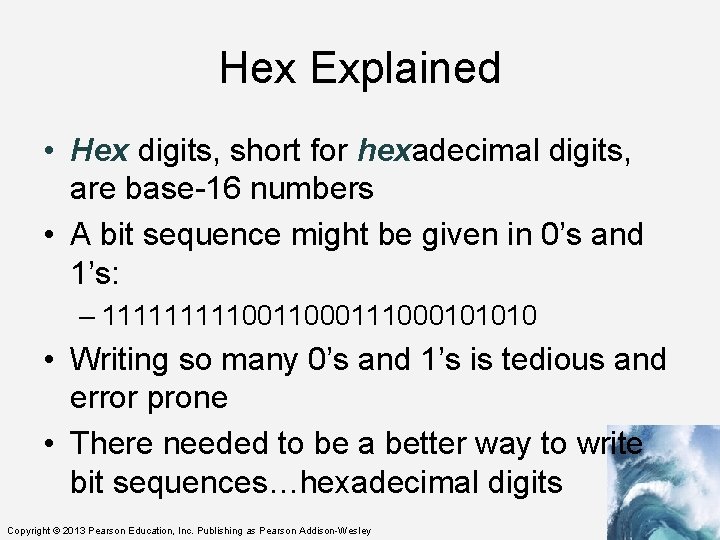

Hex Explained • Hex digits, short for hexadecimal digits, are base-16 numbers • A bit sequence might be given in 0’s and 1’s: – 111110011000101010 • Writing so many 0’s and 1’s is tedious and error prone • There needed to be a better way to write bit sequences…hexadecimal digits Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

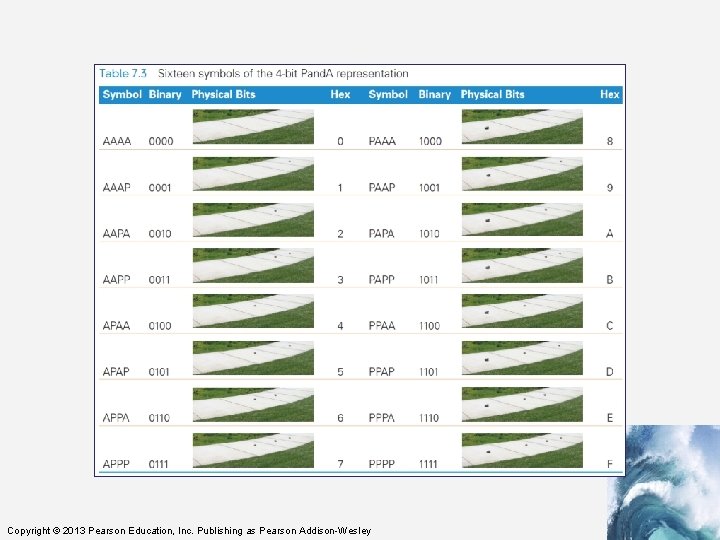

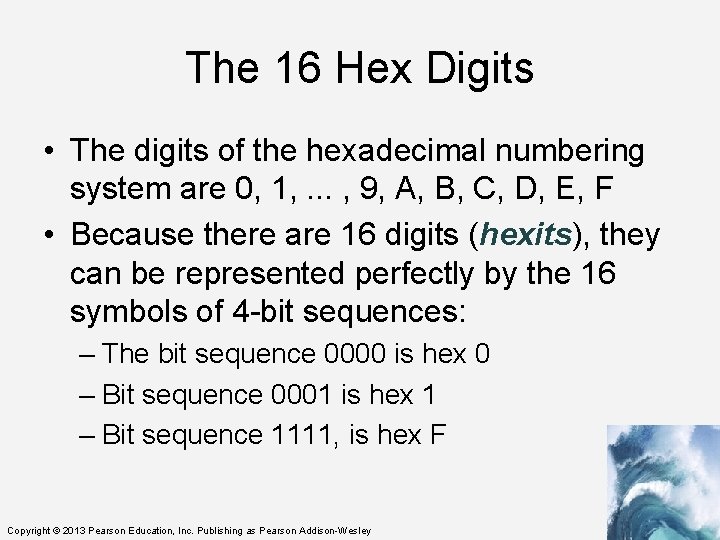

The 16 Hex Digits • The digits of the hexadecimal numbering system are 0, 1, . . . , 9, A, B, C, D, E, F • Because there are 16 digits (hexits), they can be represented perfectly by the 16 symbols of 4 -bit sequences: – The bit sequence 0000 is hex 0 – Bit sequence 0001 is hex 1 – Bit sequence 1111, is hex F Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Hex (0 -9, A-F) Decimal 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Hex 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F Binary 0000 0001 0010 0011 0100 0101 0100 0111 1000 1001 1010 1011 1100 1101 1110 1111 Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

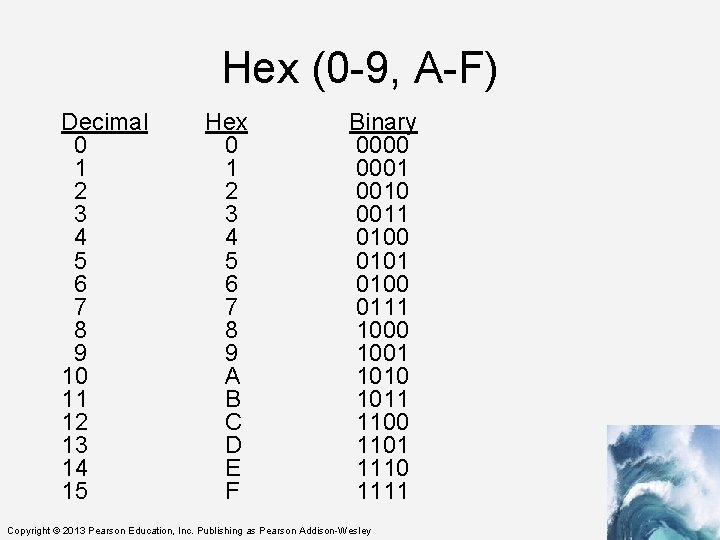

Hex to Bits and Back Again • Because each hex digit corresponds to a 4 -bit sequence, easily translate between hex and binary – 0010 1011 1010 1101 2 B A D – F A B 4 1111 1010 1011 0100 Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

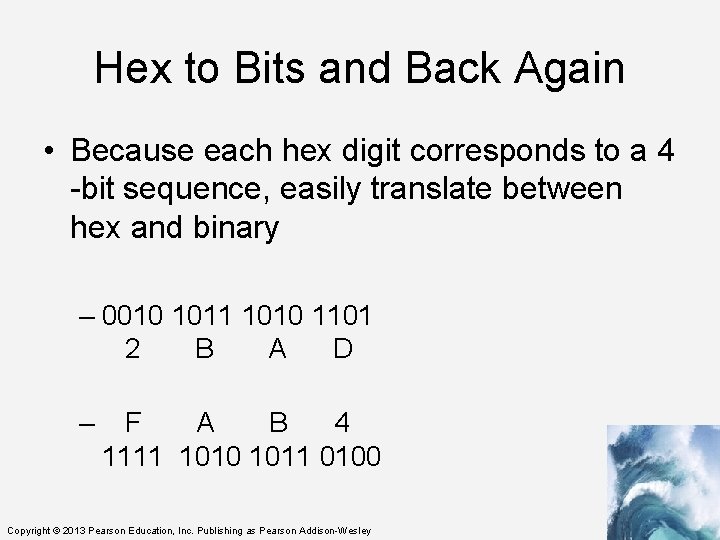

Digitizing Numbers in Binary • The two earliest uses of Pand. A were to: – Encode numbers – Encode keyboard characters • Representations for sound, images, video, and other types of information are also important Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

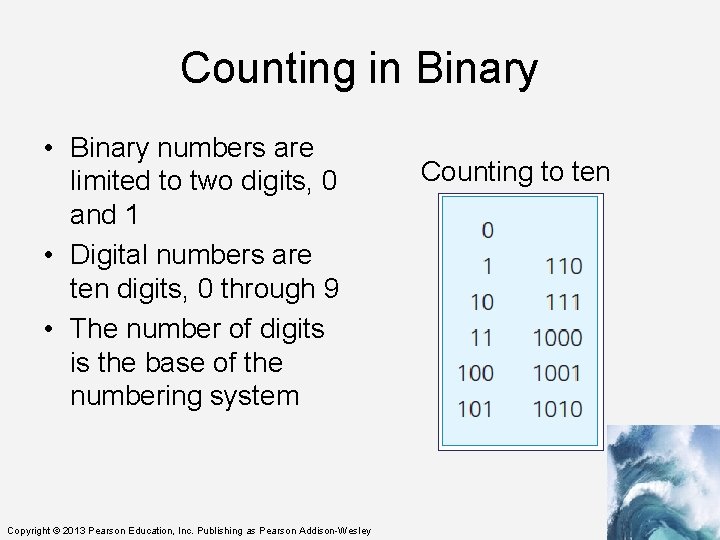

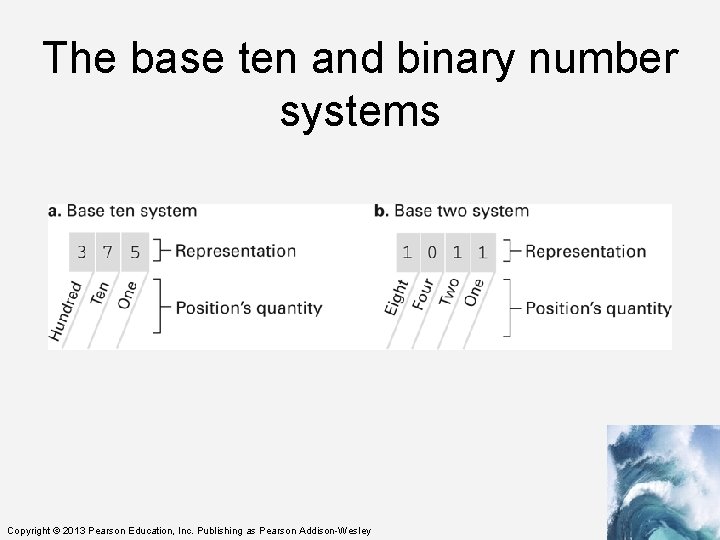

Counting in Binary • Binary numbers are limited to two digits, 0 and 1 • Digital numbers are ten digits, 0 through 9 • The number of digits is the base of the numbering system Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley Counting to ten

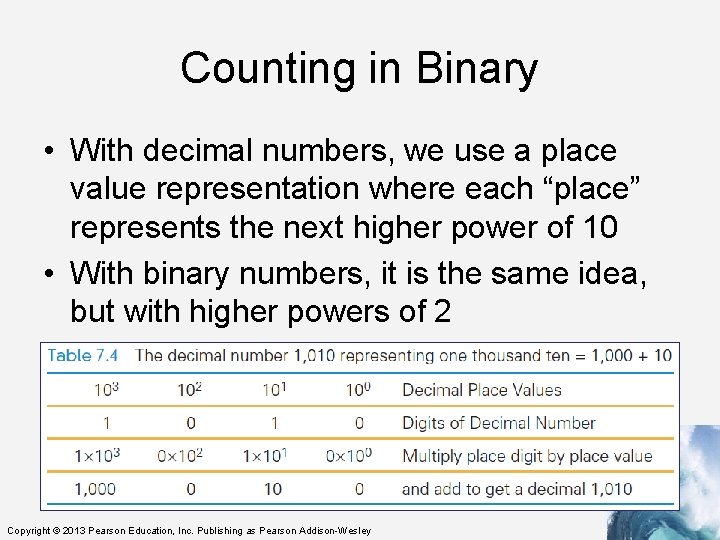

Counting in Binary • With decimal numbers, we use a place value representation where each “place” represents the next higher power of 10 • With binary numbers, it is the same idea, but with higher powers of 2 Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

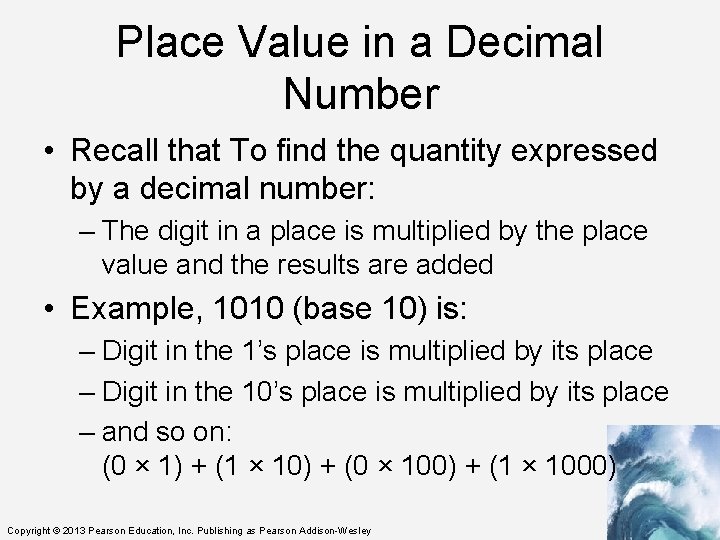

Place Value in a Decimal Number • Recall that To find the quantity expressed by a decimal number: – The digit in a place is multiplied by the place value and the results are added • Example, 1010 (base 10) is: – Digit in the 1’s place is multiplied by its place – Digit in the 10’s place is multiplied by its place – and so on: (0 × 1) + (1 × 10) + (0 × 100) + (1 × 1000) Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

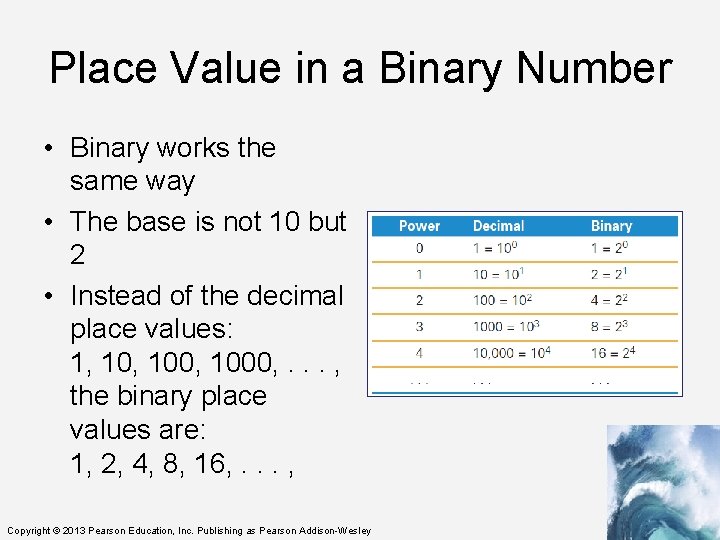

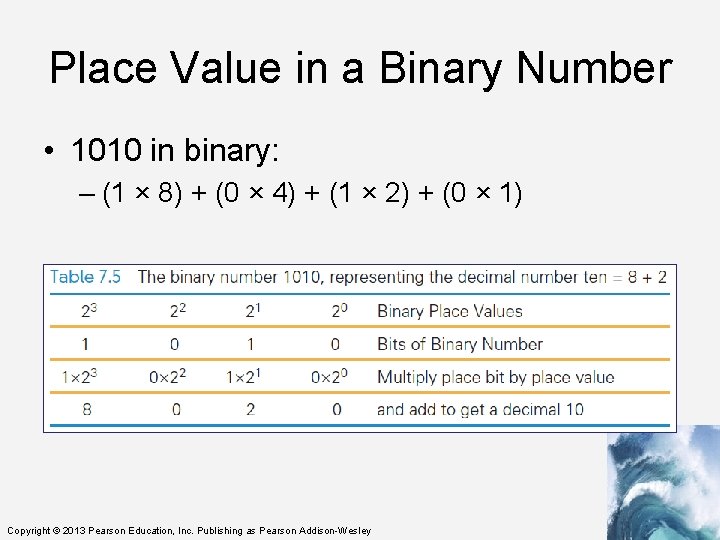

Place Value in a Binary Number • Binary works the same way • The base is not 10 but 2 • Instead of the decimal place values: 1, 100, 1000, . . . , the binary place values are: 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, . . . , Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Place Value in a Binary Number • 1010 in binary: – (1 × 8) + (0 × 4) + (1 × 2) + (0 × 1) Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

The base ten and binary number systems Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

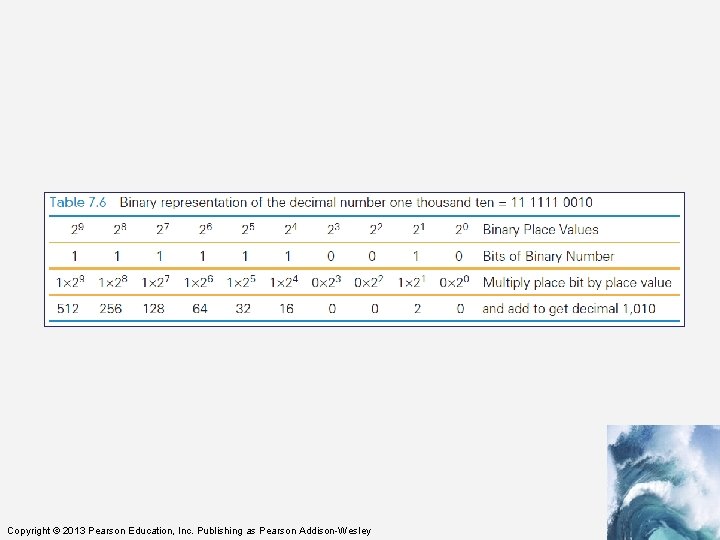

Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

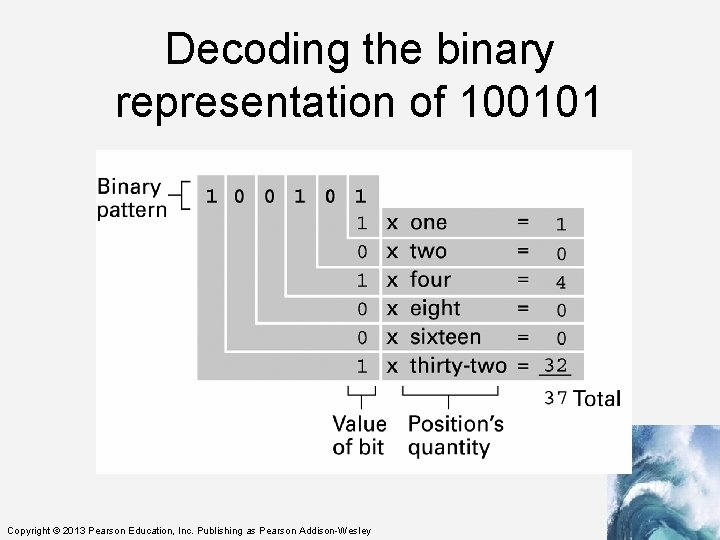

Decoding the binary representation of 100101 Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

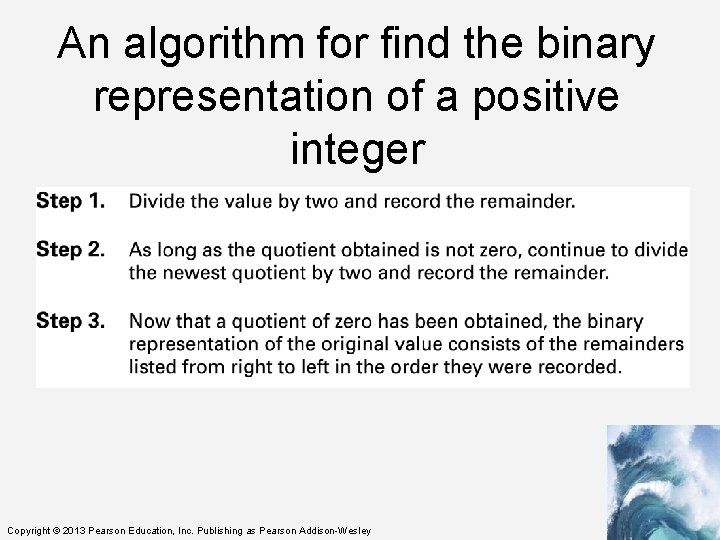

An algorithm for find the binary representation of a positive integer Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

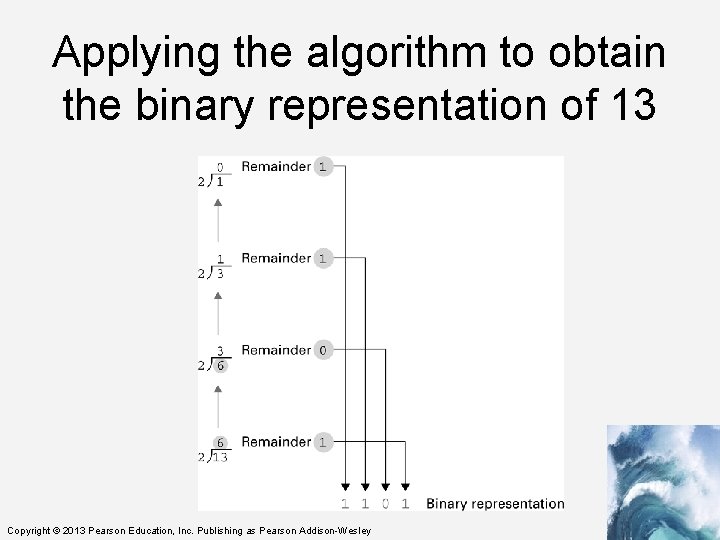

Applying the algorithm to obtain the binary representation of 13 Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

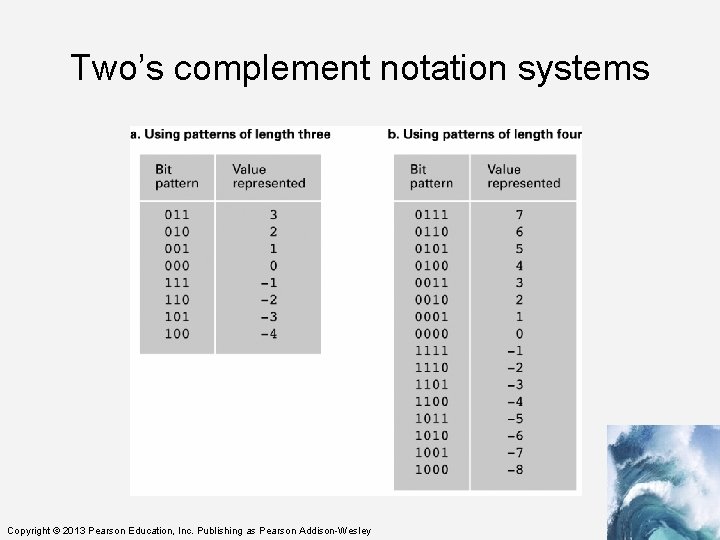

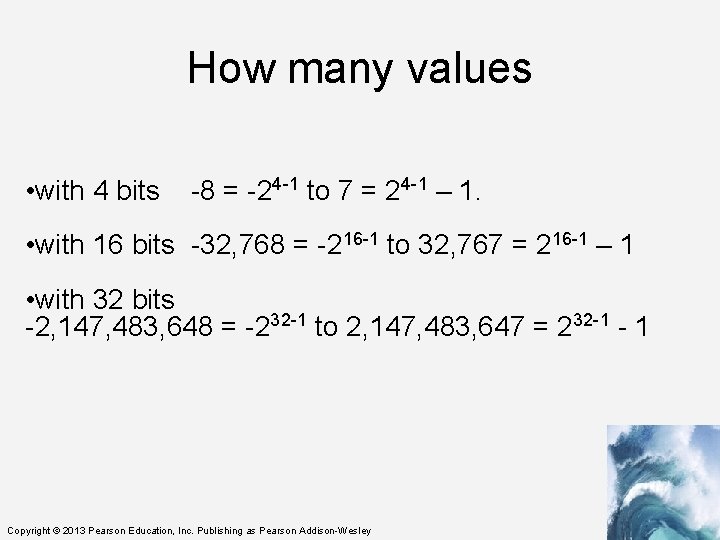

Finite Precision Binary Arithmetic • We can store two different values in 1 bit: 0 or 1. • In general, in n bits, you can store 2 n different values. • So with 4 bits, we can store 16 values - 0 to 15, but there are no negative values. • Common sense says to split the number of values in half, making half positive, half negative, not forgetting zero. • Two's complement notation Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Storing Integers • Two’s complement notation: The most popular means of representing integer values – standard use is with 8 bits • Excess notation: Another means of representing integer values – used in floating point notation • Both can suffer from overflow errors. Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Two’s complement notation systems Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

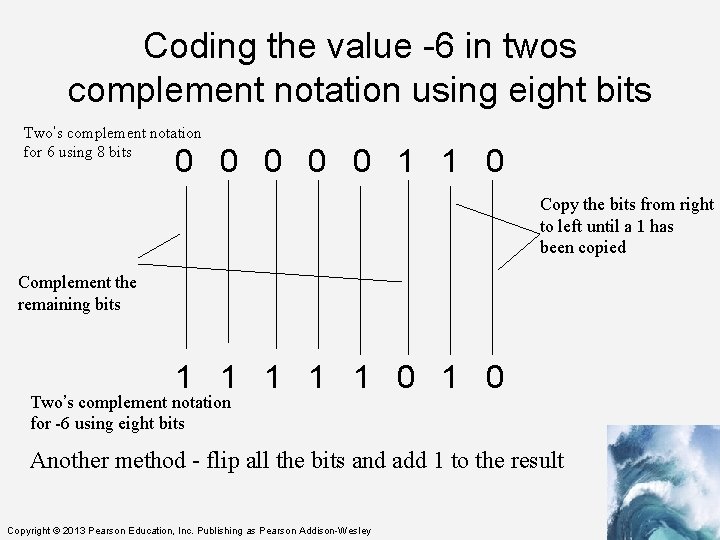

Coding the value -6 in twos complement notation using eight bits Two’s complement notation for 6 using 8 bits 0 0 0 1 1 0 Copy the bits from right to left until a 1 has been copied Complement the remaining bits 1 1 1 0 Two’s complement notation for -6 using eight bits Another method - flip all the bits and add 1 to the result Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

How many values • with 4 bits -8 = -24 -1 to 7 = 24 -1 – 1. • with 16 bits -32, 768 = -216 -1 to 32, 767 = 216 -1 – 1 • with 32 bits -2, 147, 483, 648 = -232 -1 to 2, 147, 483, 647 = 232 -1 - 1 Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

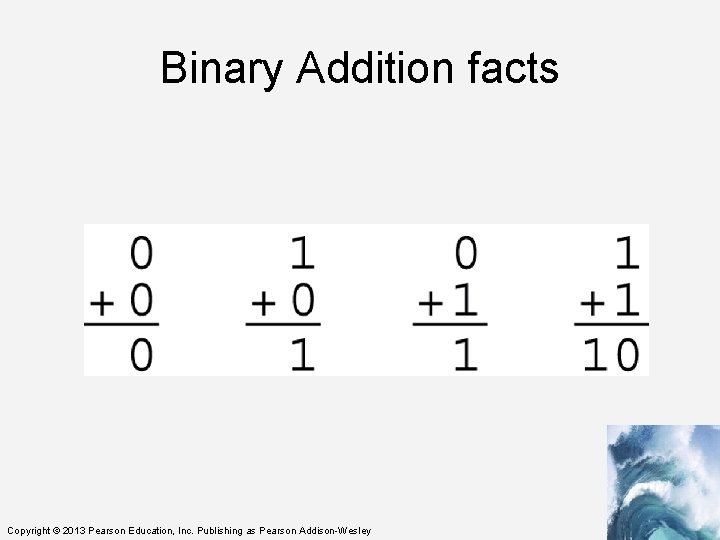

Binary Addition facts Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

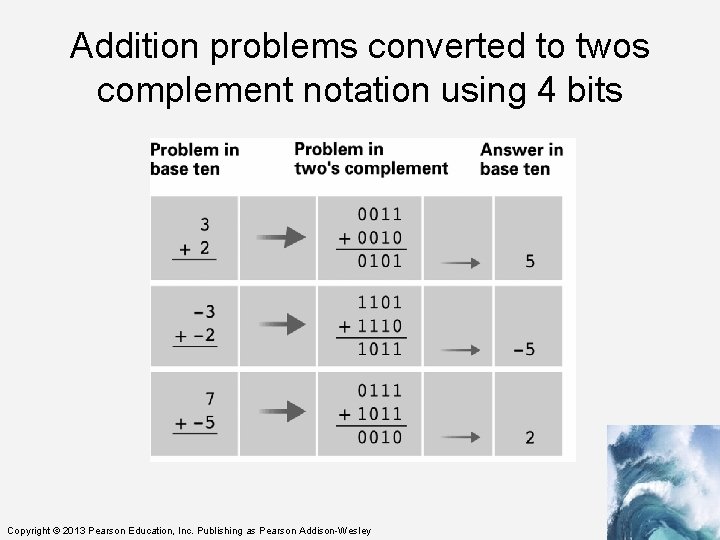

Addition problems converted to twos complement notation using 4 bits Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

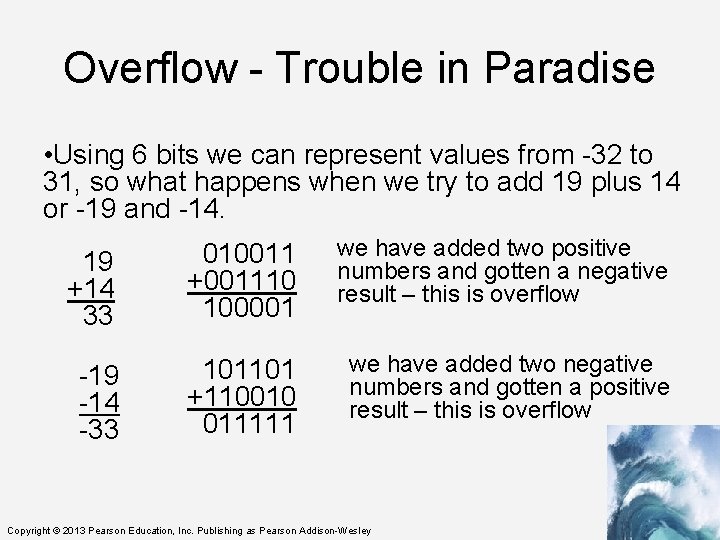

Overflow - Trouble in Paradise • Using 6 bits we can represent values from -32 to 31, so what happens when we try to add 19 plus 14 or -19 and -14. 19 +14 33 010011 +001110 100001 we have added two positive numbers and gotten a negative result – this is overflow -19 -14 -33 101101 +110010 011111 we have added two negative numbers and gotten a positive result – this is overflow Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

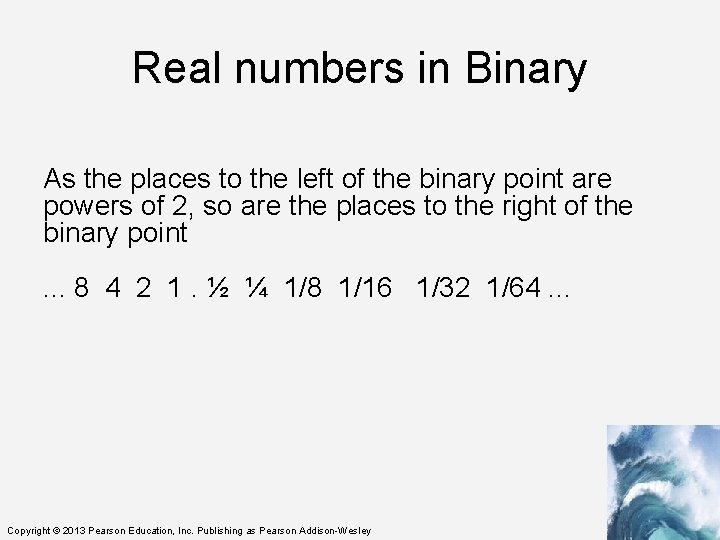

Real numbers in Binary As the places to the left of the binary point are powers of 2, so are the places to the right of the binary point. . . 8 4 2 1. ½ ¼ 1/8 1/16 1/32 1/64. . . Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

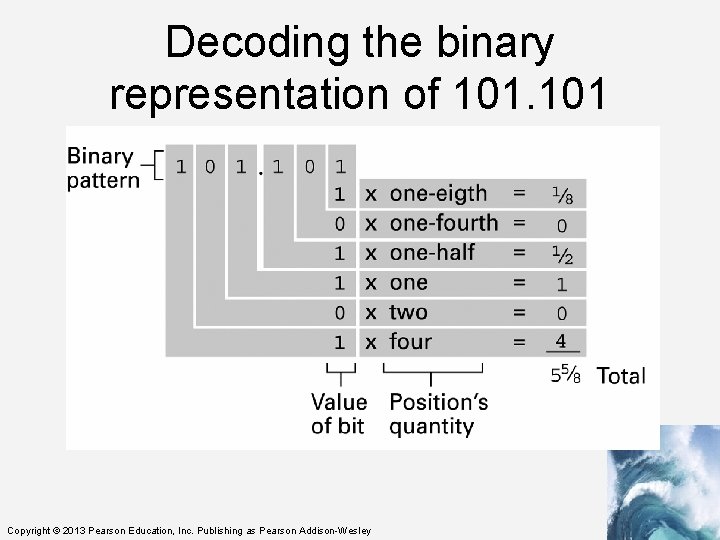

Decoding the binary representation of 101 Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

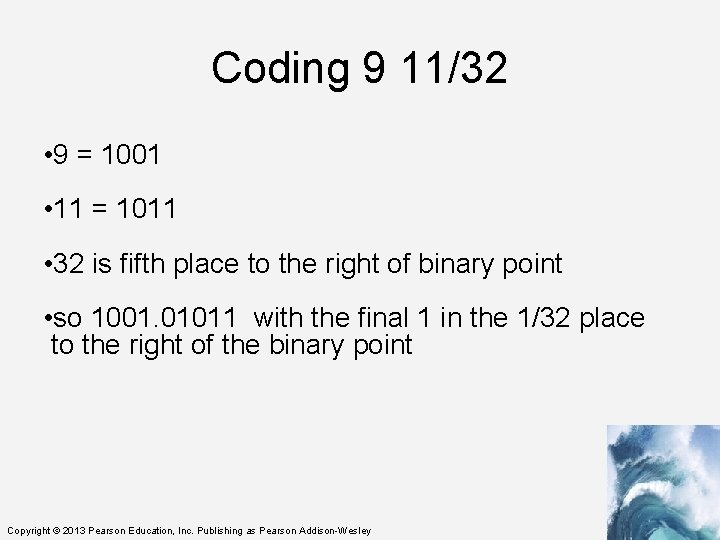

Coding 9 11/32 • 9 = 1001 • 11 = 1011 • 32 is fifth place to the right of binary point • so 1001. 01011 with the final 1 in the 1/32 place to the right of the binary point Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

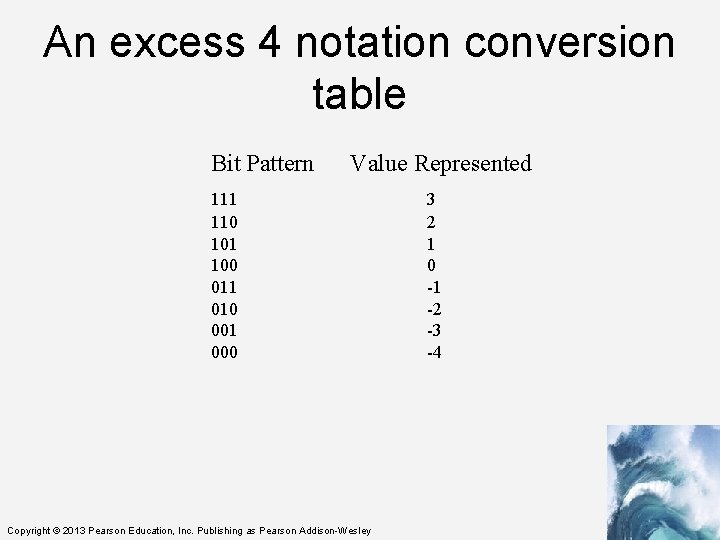

An excess 4 notation conversion table Bit Pattern Value Represented 111 110 101 100 011 010 001 000 Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley 3 2 1 0 -1 -2 -3 -4

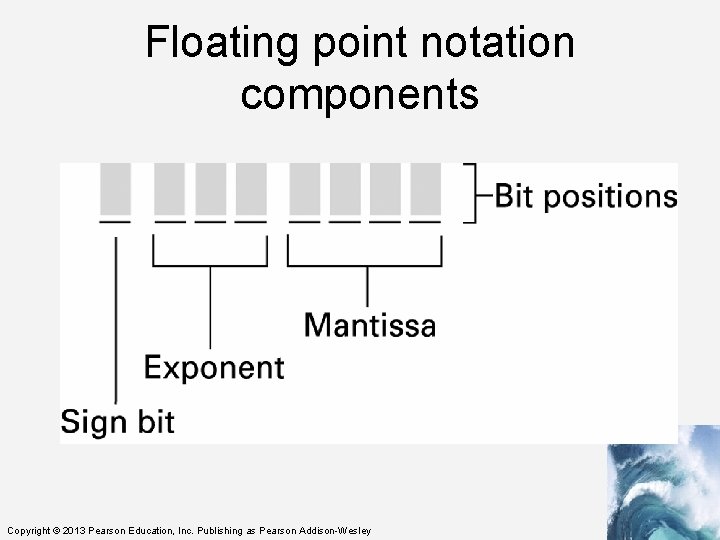

Storing Fractions • Floating-point Notation: Consists of a sign bit, a mantissa field, and an exponent field. • Related topics include Normalized form Truncation errors Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Floating point notation components Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

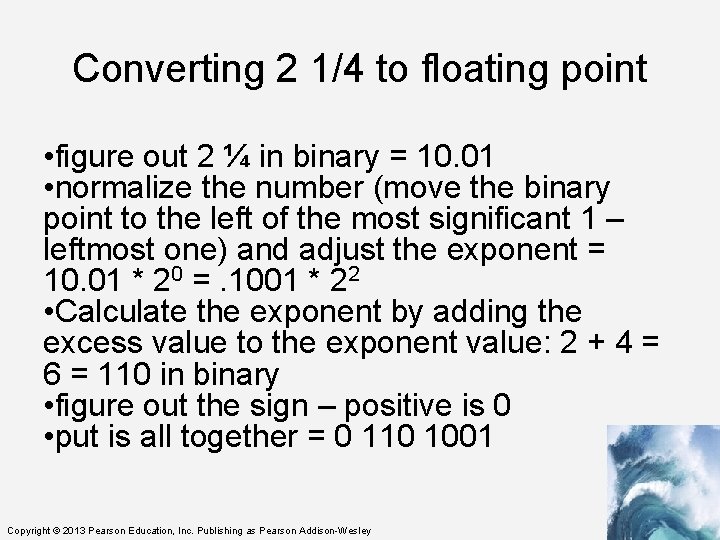

Converting 2 1/4 to floating point • figure out 2 ¼ in binary = 10. 01 • normalize the number (move the binary point to the left of the most significant 1 – leftmost one) and adjust the exponent = 10. 01 * 20 =. 1001 * 22 • Calculate the exponent by adding the excess value to the exponent value: 2 + 4 = 6 = 110 in binary • figure out the sign – positive is 0 • put is all together = 0 110 1001 Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

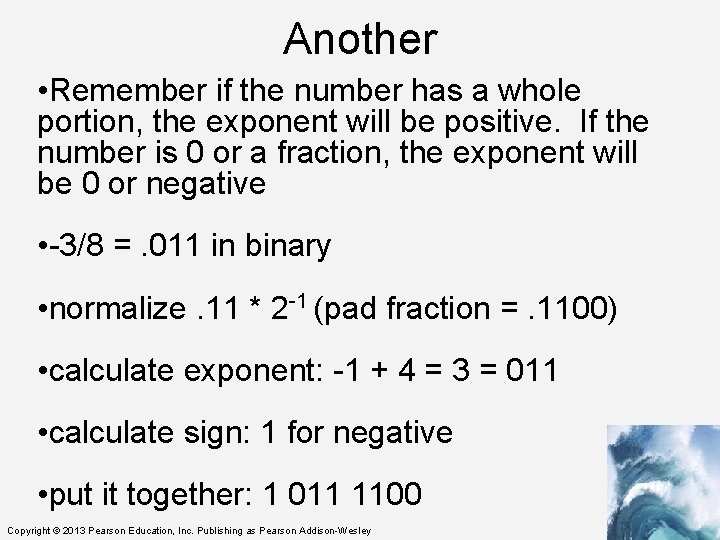

Another • Remember if the number has a whole portion, the exponent will be positive. If the number is 0 or a fraction, the exponent will be 0 or negative • -3/8 =. 011 in binary • normalize. 11 * 2 -1 (pad fraction =. 1100) • calculate exponent: -1 + 4 = 3 = 011 • calculate sign: 1 for negative • put it together: 1 011 1100 Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

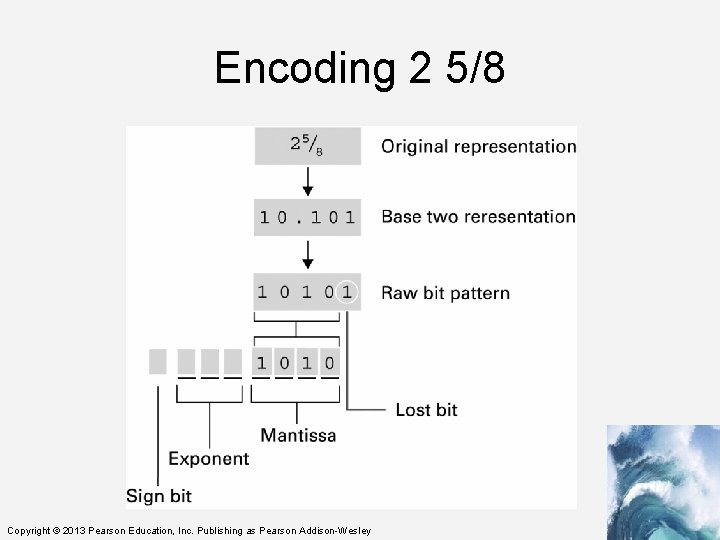

Encoding 2 5/8 Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Digitizing Text • The number of bits determines the number of symbols available for representing values: – n bits in sequence yield 2 n symbols • The more characters you want encoded, the more symbols you need Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Digitizing Text • Roman letters, Arabic numerals, and about a dozen punctuation characters are about the minimum needed to digitize English text • What about: – Basic arithmetic symbols like +, −, *, /, =? – Characters not required for English ö, é, ñ, ø? – Punctuation? « » , ¿, π, ∀)? What about business symbols: ¢, £, ¥, ©, and ®? – And so on. Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Assigning Symbols • We need to represent: – 26 uppercase, – 26 lowercase letters, – 10 numerals, – 20 punctuation characters, – 10 useful arithmetic characters, – 3 other characters (new line, tab, and backspace) – 95 symbols…enough for English Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Assigning Symbols • To represent 95 distinct symbols, we need 7 bits – 6 bits gives only 26 = 64 symbols – 7 bits give 27 = 128 symbols • 128 symbols is ample for the 95 different characters needed for English characters • Some additional characters must also be represented Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

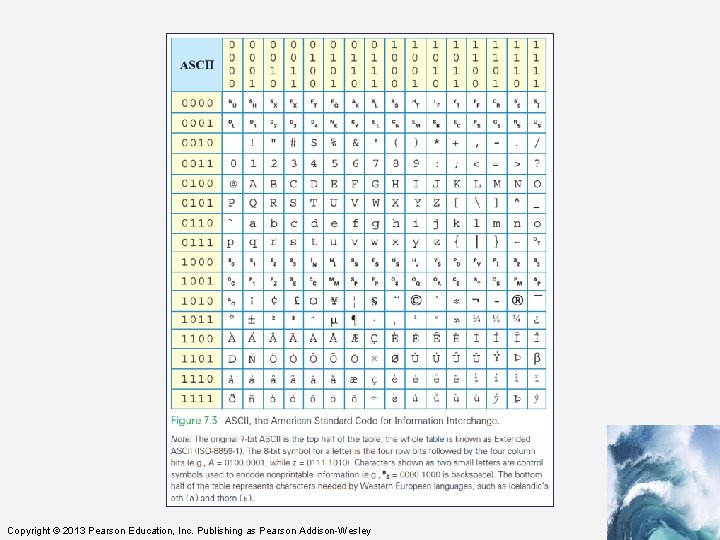

Assigning Symbols • ASCII stands for American Standard Code for Information Interchange • ASCII is a widely used 7 -bit (27) code • The advantages of a “standard” are many: – Computer parts built by different manufacturers can be connected – Programs can create data and store it so that other programs can process it later, and so forth Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

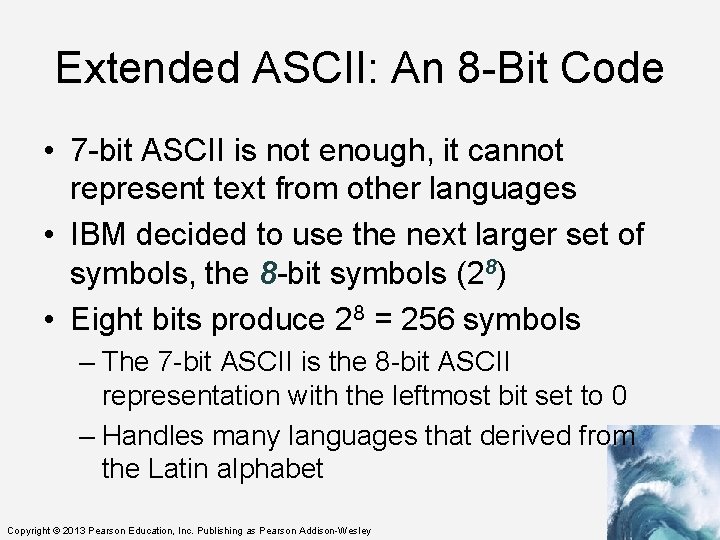

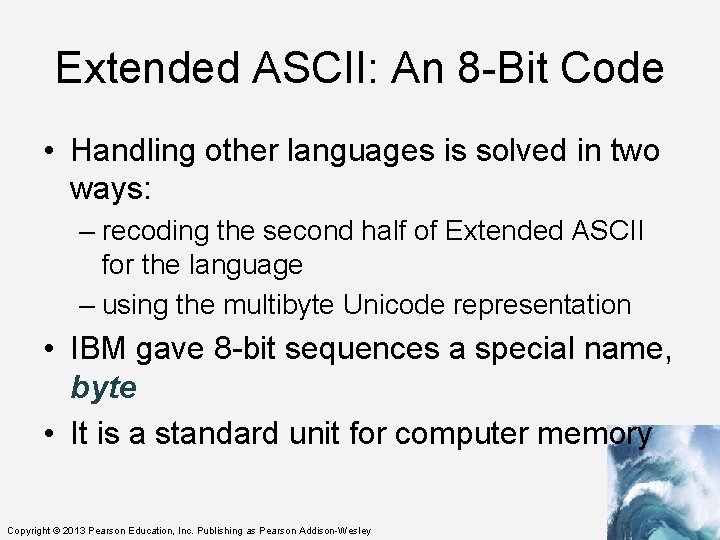

Extended ASCII: An 8 -Bit Code • 7 -bit ASCII is not enough, it cannot represent text from other languages • IBM decided to use the next larger set of symbols, the 8 -bit symbols (28) • Eight bits produce 28 = 256 symbols – The 7 -bit ASCII is the 8 -bit ASCII representation with the leftmost bit set to 0 – Handles many languages that derived from the Latin alphabet Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Extended ASCII: An 8 -Bit Code • Handling other languages is solved in two ways: – recoding the second half of Extended ASCII for the language – using the multibyte Unicode representation • IBM gave 8 -bit sequences a special name, byte • It is a standard unit for computer memory Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Advantages of Long Encodings • With computing, we usually try to be efficient by using the shortest symbol sequence to minimize the amount of memory • Examples of the opposite: – NATO Broadcast Alphabet – Bar Codes Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

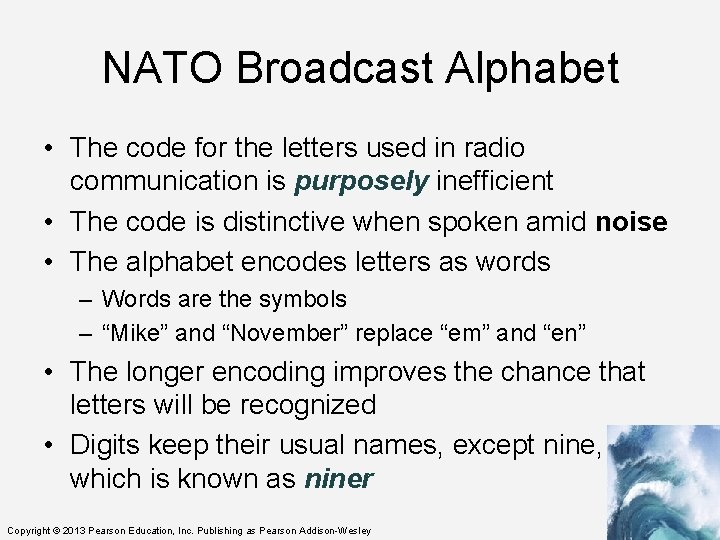

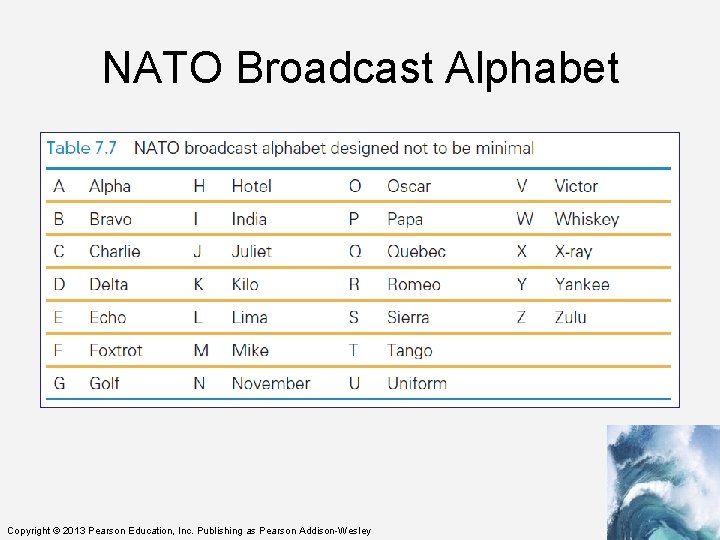

NATO Broadcast Alphabet • The code for the letters used in radio communication is purposely inefficient • The code is distinctive when spoken amid noise • The alphabet encodes letters as words – Words are the symbols – “Mike” and “November” replace “em” and “en” • The longer encoding improves the chance that letters will be recognized • Digits keep their usual names, except nine, which is known as niner Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

NATO Broadcast Alphabet Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

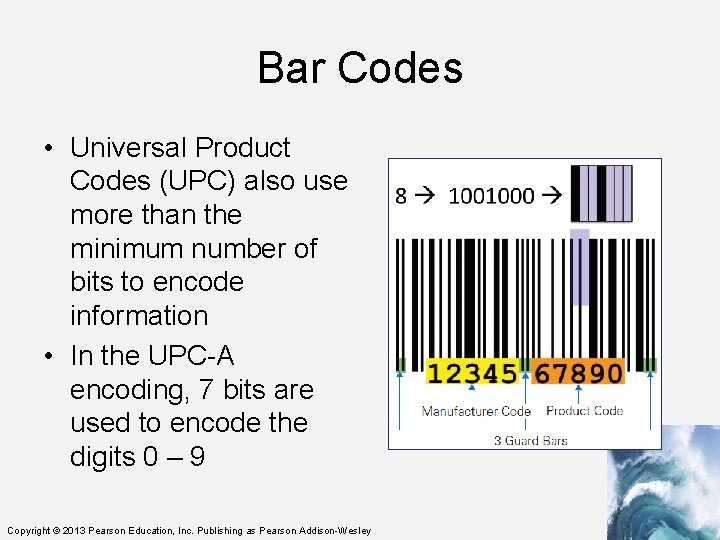

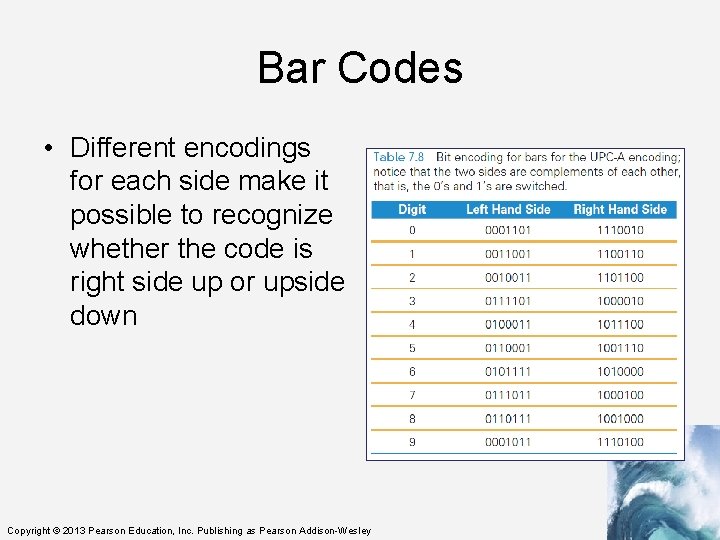

Bar Codes • Universal Product Codes (UPC) also use more than the minimum number of bits to encode information • In the UPC-A encoding, 7 bits are used to encode the digits 0 – 9 Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Bar Codes • UPC encodes the manufacturer (left side) and the product (right side) • Different bit combinations are used for each side • One side is the complement of the other side • The bit patterns were chosen to appear as different as possible from each other Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Bar Codes • Different encodings for each side make it possible to recognize whether the code is right side up or upside down Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

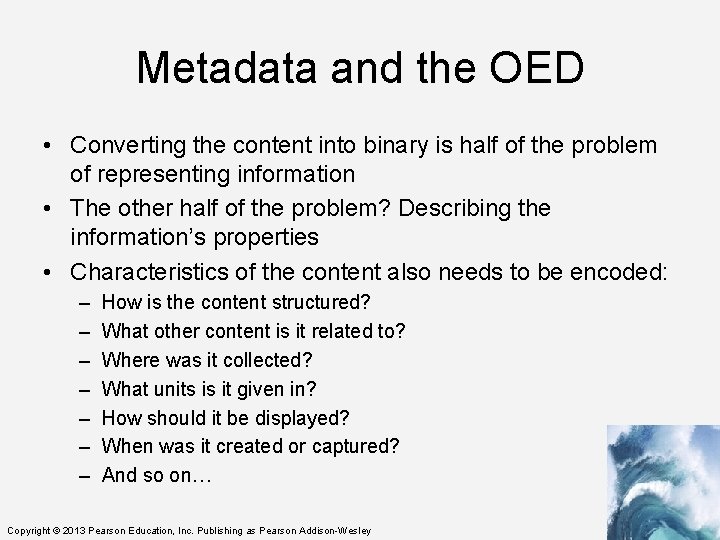

Metadata and the OED • Converting the content into binary is half of the problem of representing information • The other half of the problem? Describing the information’s properties • Characteristics of the content also needs to be encoded: – – – – How is the content structured? What other content is it related to? Where was it collected? What units is it given in? How should it be displayed? When was it created or captured? And so on… Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Metadata and the OED • Metadata: information describing information • Metadata is the third basic form of data • It does not require its own binary encoding • The most common way to give metadata is with tags (think back to Chapter 4 when we wrote HTML) Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

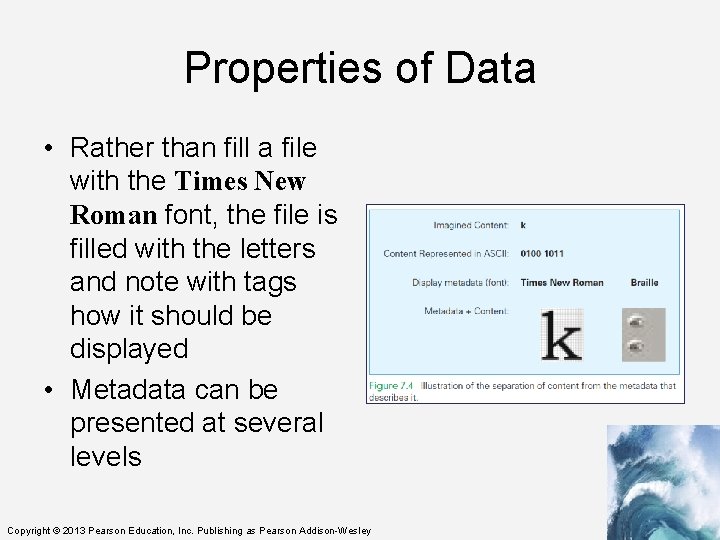

Properties of Data • Metadata is separate from the information that it describes • For example: – The ASCII representation of letters has been discussed – How do those letters look in Comic Sans font? – How they are displayed is metadata Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Properties of Data • Rather than fill a file with the Times New Roman font, the file is filled with the letters and note with tags how it should be displayed • Metadata can be presented at several levels Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Using Tags for Metadata • The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is the definitive reference for every English word’s meaning, etymology, and usage • The printed version of the OED is truly monumental is 20 volumes, weighs 150 pounds, and fills 4 feet of shelf space Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Using Tags for Metadata • In 1984, the conversion of the OED to digital form began • Imagine, with what you know about searching on the computer, finding the definition for the verb set: – “set” is part of many words – You would find closet, horsetail, settle, and more • Software can help sort out the words Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

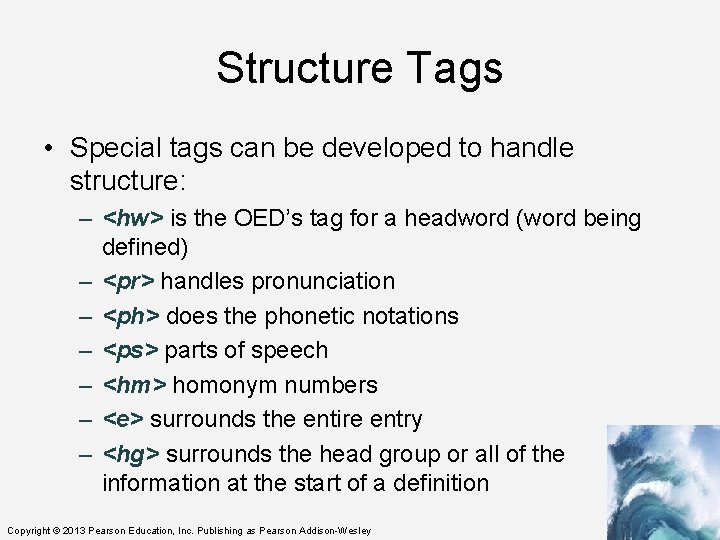

Structure Tags • Special tags can be developed to handle structure: – <hw> is the OED’s tag for a headword (word being defined) – <pr> handles pronunciation – <ph> does the phonetic notations – <ps> parts of speech – <hm> homonym numbers – <e> surrounds the entire entry – <hg> surrounds the head group or all of the information at the start of a definition Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Structure Tags • With structure tags, software can use a simple algorithm to find what is needed • Tags do not print • They are included only to specify the structure, so the computer knows what part of the dictionary to use • Structure tags are also useful formatting…for example, boldface used for headwords • Knowing the structure makes it possible to generate the formatting information Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Parity • Computer memory is subject to errors • An extra bit is added to the memory to help detect errors – A ninth bit per byte can detect errors using parity • Parity refers to whether a number is even or odd – Count the number of 1’s in the byte. If there is an even number of 1’s we set the ninth bit to 0 Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Parity • All 9 -bit groups have even parity: – Any single bit error in a group causes its parity to become odd – This allows hardware to detect that an error has occurred – It cannot detect which bit is wrong, however Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Why “Byte”? • IBM was building a supercomputer, called Stretch • They needed a word for a quantity of memory between a bit and a word” – A word of computer memory is typically the amount required to represent computer instructions (currently a word is 32 bits) Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Why “Byte”? • Then, why not bite? • The ‘i’ to a ‘y’ was done so that someone couldn’t accidentally change ‘byte’ to ‘bit’ by the dropping the ‘e’ ” – bite – byte bit byt (the meaning changes) (what’s a byt? ) Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Summary • We began the chapter by learning that digitizing doesn’t require digits—any symbols will do • We explored the following: – Pand. A encoding, which is based on the presence and absence of a physical phenomenon. Their patterns are discrete; they form the basic unit of a bit. Their names (most often 1 and 0) can be any pair of opposite terms. Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Summary • We explored the following: – 7 -bit ASCII, an early assignment of bit sequences (symbols) to keyboard characters. Extended or 8 -bit ASCII is the standard. – The need to use more than the minimum number of bits to encode information. Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

Summary • We explored the following: – How documents like the Oxford English Dictionary are digitized. We learned that tags associate metadata with every part of the OED. Using that data, a computer can easily help us find words and other information. – The mystery of the y in byte. Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley

- Slides: 82