chapter 7 Cardiorespiratory Responses to Acute Exercise Learning

- Slides: 50

chapter 7 Cardiorespiratory Responses to Acute Exercise

Learning Objectives • Learn about the cardiovascular adjustments to acute exercise • Find out how the cardiovascular system responds to increased demands during exercise • Examine how the respiratory system functions during exercise and how it can sometimes limit physical performance (continued)

Learning Objectives (continued) • Learn how the respiratory system maintains acid–base balance • Find out why this acid–base balance is important during exercise

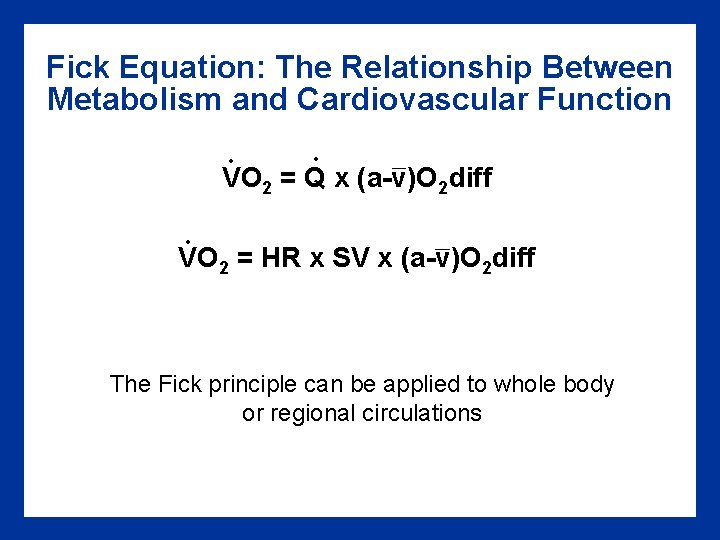

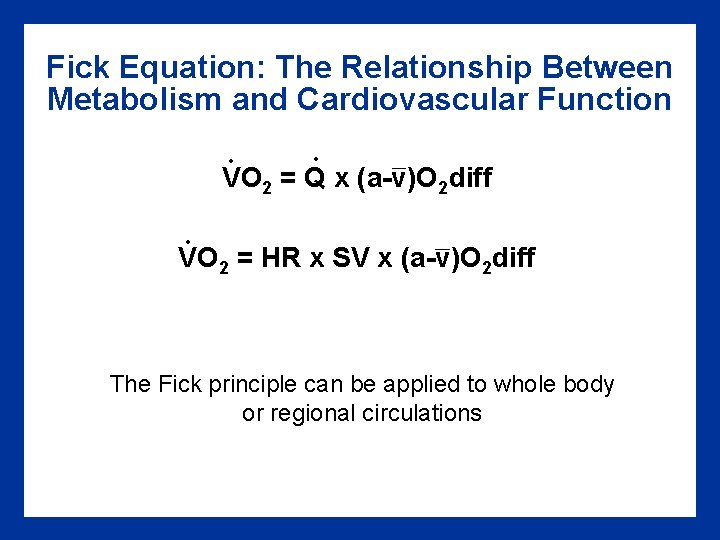

Fick Equation: The Relationship Between Metabolism and Cardiovascular Function. . VO 2 = Q x (a-v)O 2 diff. VO 2 = HR x SV x (a-v)O 2 diff The Fick principle can be applied to whole body or regional circulations

Cardiovascular Response to Acute Exercise The components of the cardiovascular system must meet the increased demands for blood flow to the exercising muscle • Heart rate (HR) • Stroke volume (SV). • Cardiac output (Q) • Blood pressure (BP) • Blood flow • Blood

Resting Heart Rate • Averages 60 to 80 beats per minute (bpm) • Highly trained athletes: 28 -40 bpm (increased vagal tone) • RHR is affected by environmental factors (extreme temperatures and altitude) and endocrine hormones • Preexercise heart rate is usually higher than RHR because of an anticipatory increase in sympathetic activity

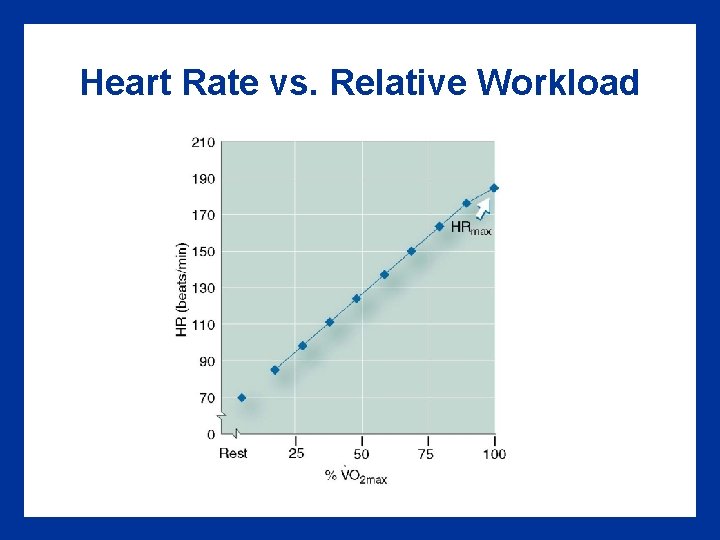

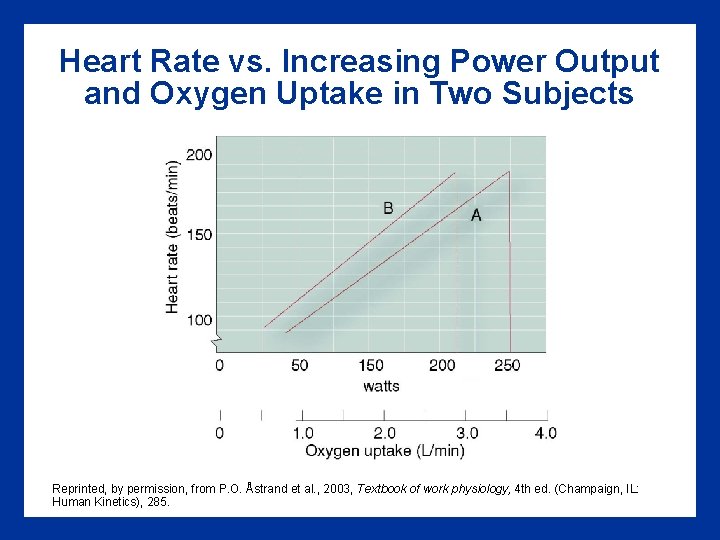

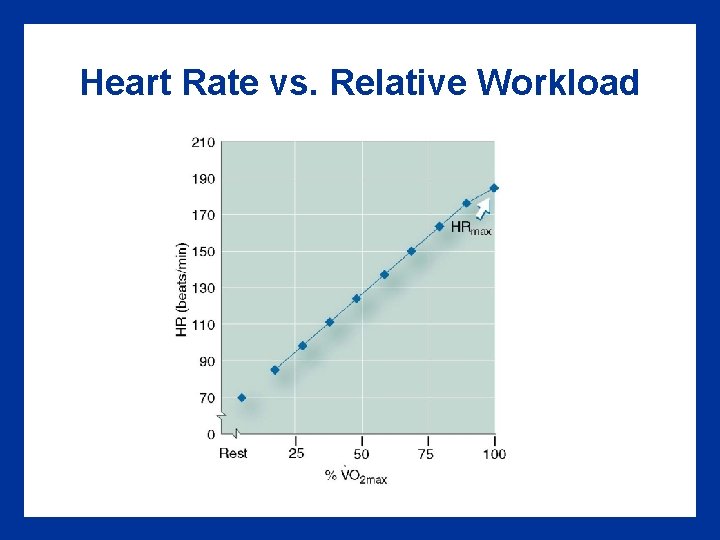

Heart Rate During Exercise • HR increases in direct proportion to the increase in exercise intensity • HR will plateau at a maximum even as workload continues to increase (HRmax) • HRmax remains constant day to day and declines ~1 beat per year • HRmax can be estimated: HRmax = 220 – age in years HRmax = 208 – (0. 7 x age in years)

Heart Rate vs. Relative Workload

Steady-State Heart Rate • When workload is constant, HR increases rapidly until it reaches a plateau (i. e. , steady state) • For each increase in workload, HR will increase to a new steady-state value in 2 -3 minutes • Exercise training decreases steady-state heart rate for a given submaximal workload

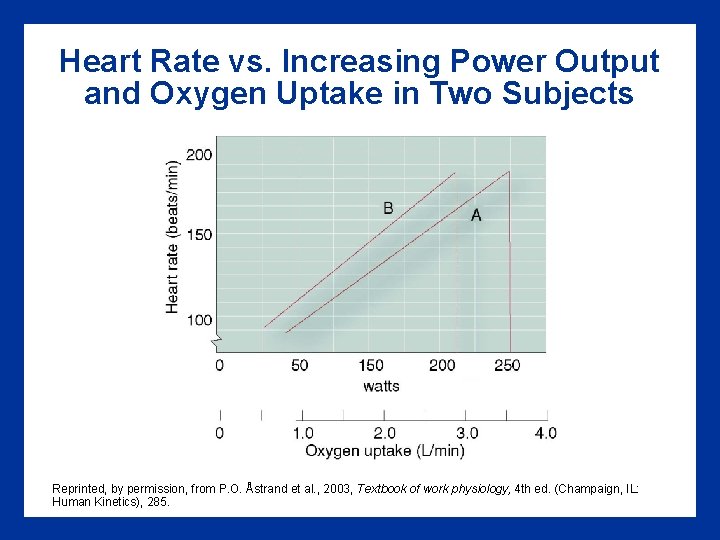

Heart Rate vs. Increasing Power Output and Oxygen Uptake in Two Subjects Reprinted, by permission, from P. O. Åstrand et al. , 2003, Textbook of work physiology, 4 th ed. (Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics), 285.

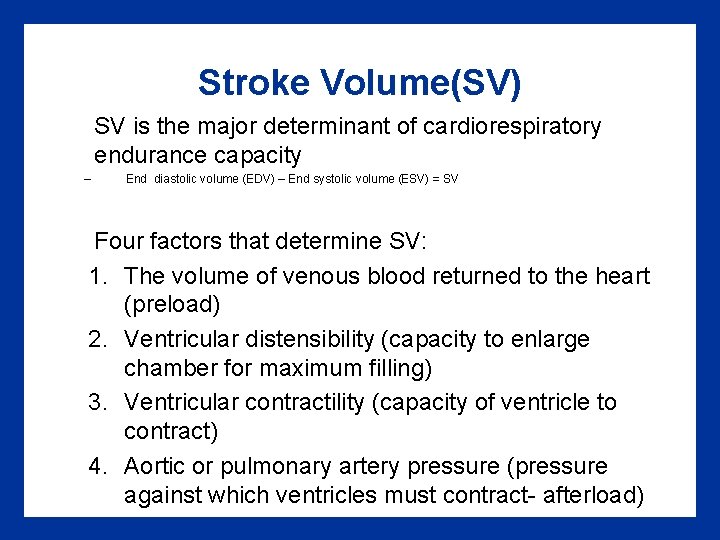

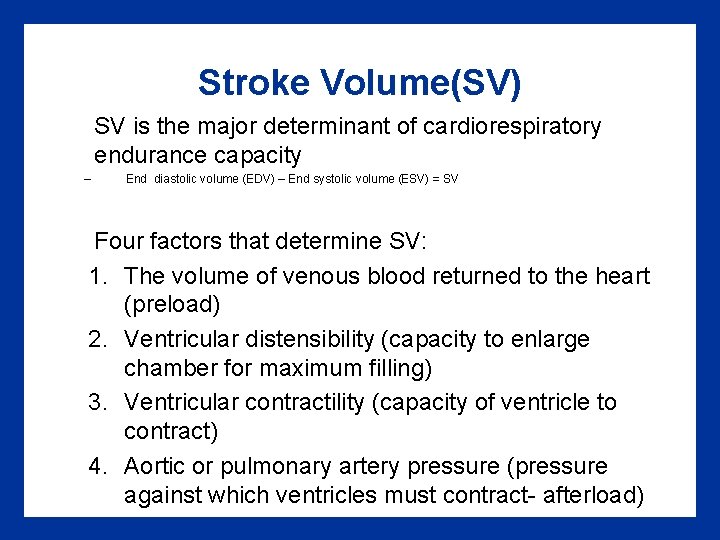

Stroke Volume(SV) SV is the major determinant of cardiorespiratory endurance capacity – End diastolic volume (EDV) – End systolic volume (ESV) = SV Four factors that determine SV: 1. The volume of venous blood returned to the heart (preload) 2. Ventricular distensibility (capacity to enlarge chamber for maximum filling) 3. Ventricular contractility (capacity of ventricle to contract) 4. Aortic or pulmonary artery pressure (pressure against which ventricles must contract- afterload)

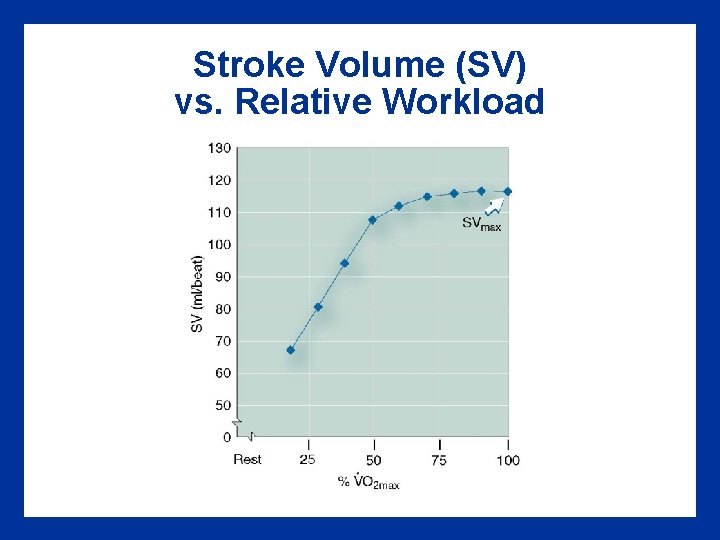

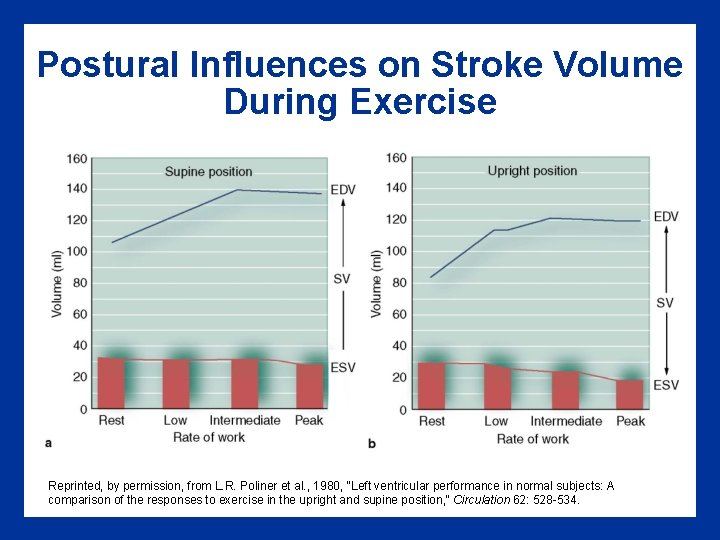

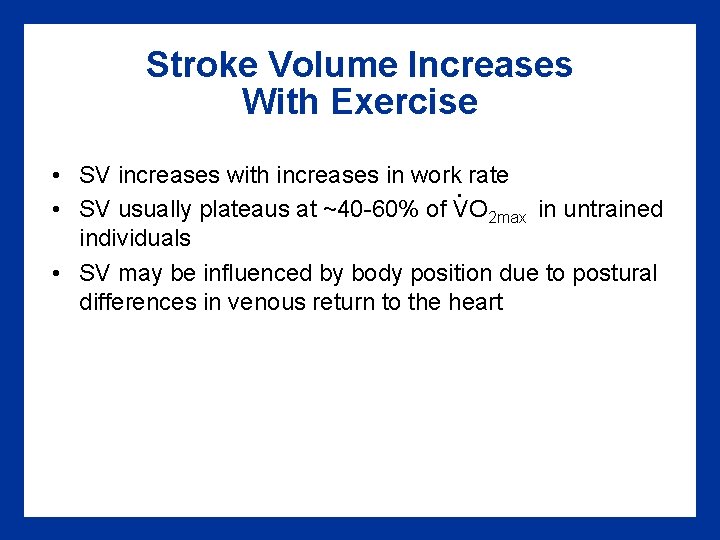

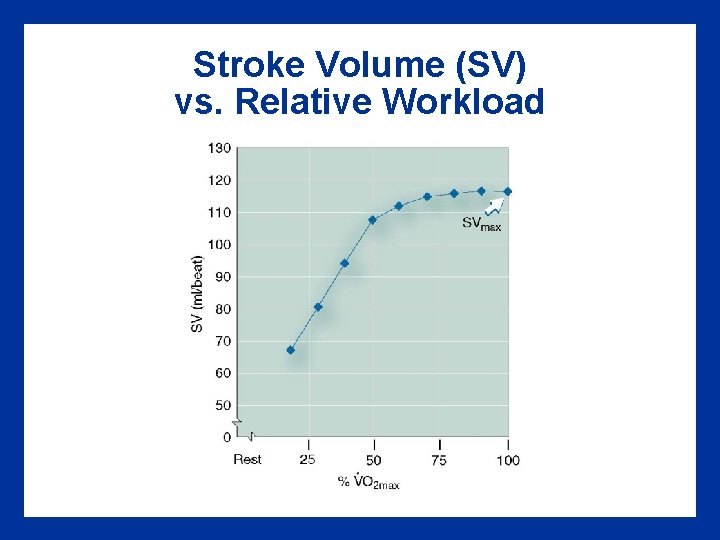

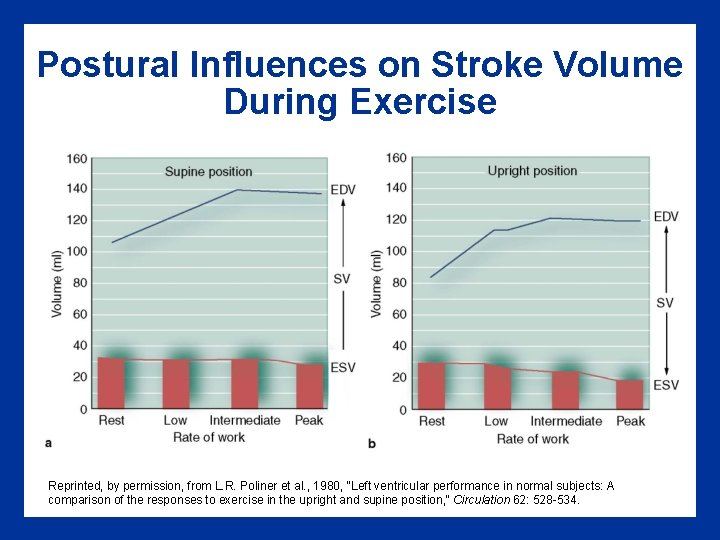

Stroke Volume Increases With Exercise • SV increases with increases in work rate. • SV usually plateaus at ~40 -60% of VO 2 max in untrained individuals • SV may be influenced by body position due to postural differences in venous return to the heart

Stroke Volume (SV) vs. Relative Workload

Postural Influences on Stroke Volume During Exercise Reprinted, by permission, from L. R. Poliner et al. , 1980, "Left ventricular performance in normal subjects: A comparison of the responses to exercise in the upright and supine position, " Circulation 62: 528 -534.

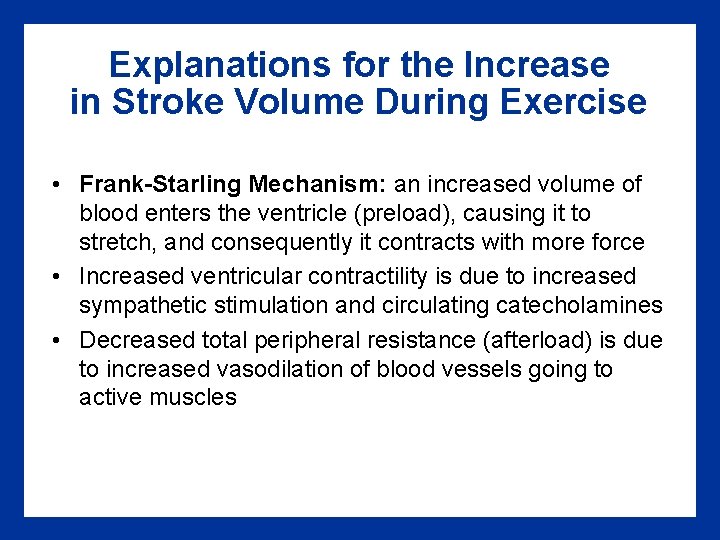

Explanations for the Increase in Stroke Volume During Exercise • Frank-Starling Mechanism: an increased volume of blood enters the ventricle (preload), causing it to stretch, and consequently it contracts with more force • Increased ventricular contractility is due to increased sympathetic stimulation and circulating catecholamines • Decreased total peripheral resistance (afterload) is due to increased vasodilation of blood vessels going to active muscles

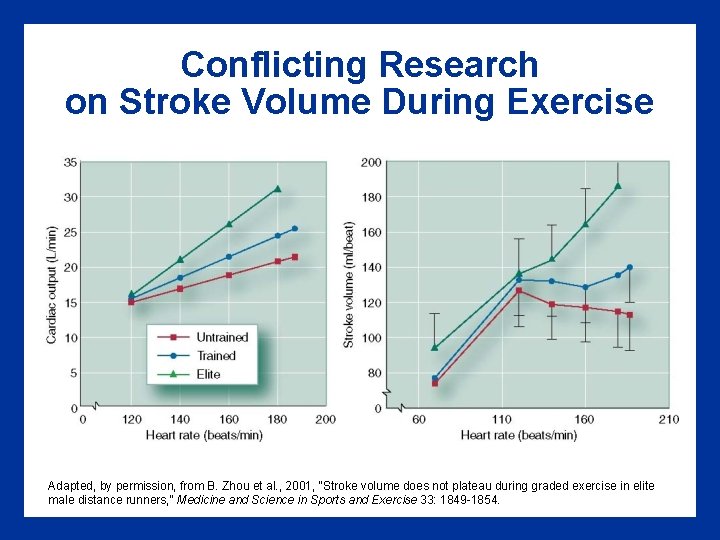

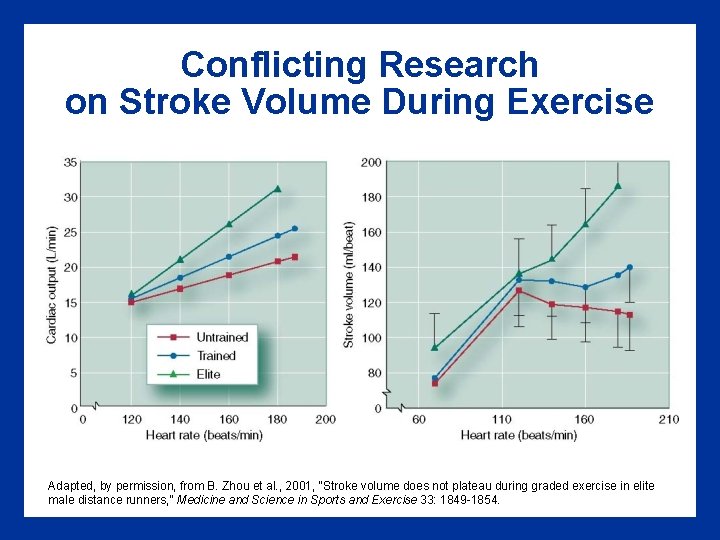

Conflicting Research on Stroke Volume During Exercise Adapted, by permission, from B. Zhou et al. , 2001, “Stroke volume does not plateau during graded exercise in elite male distance runners, ” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 33: 1849 -1854.

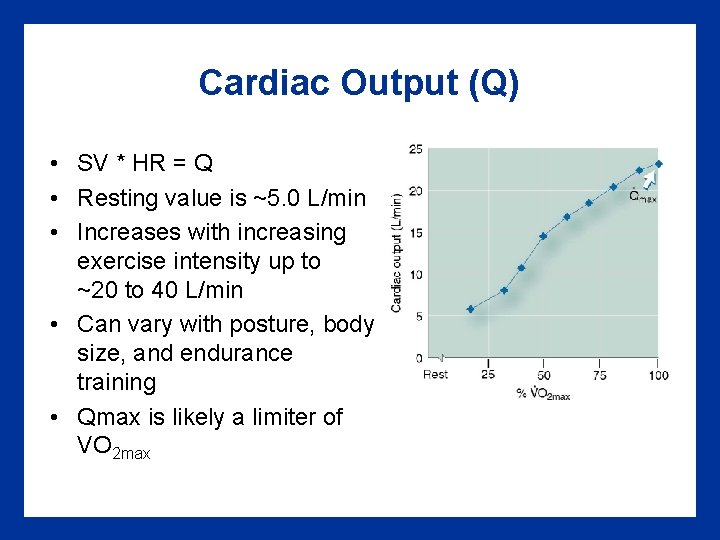

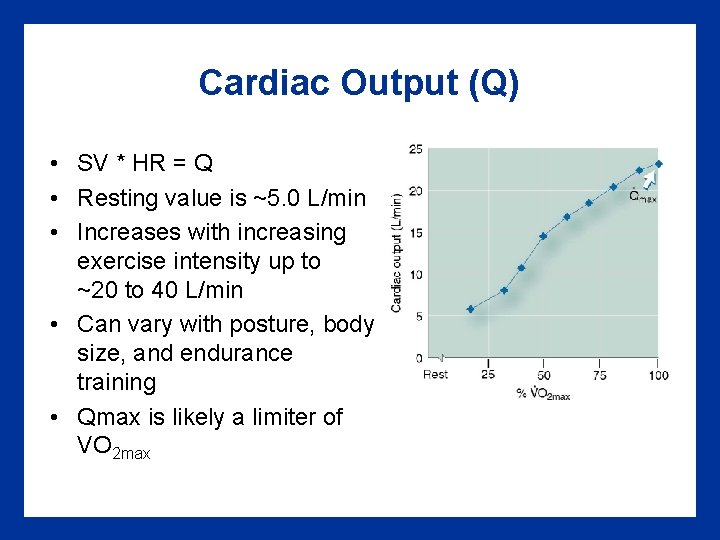

Cardiac Output (Q) • SV * HR = Q • Resting value is ~5. 0 L/min • Increases with increasing exercise intensity up to ~20 to 40 L/min • Can vary with posture, body size, and endurance training • Qmax is likely a limiter of VO 2 max

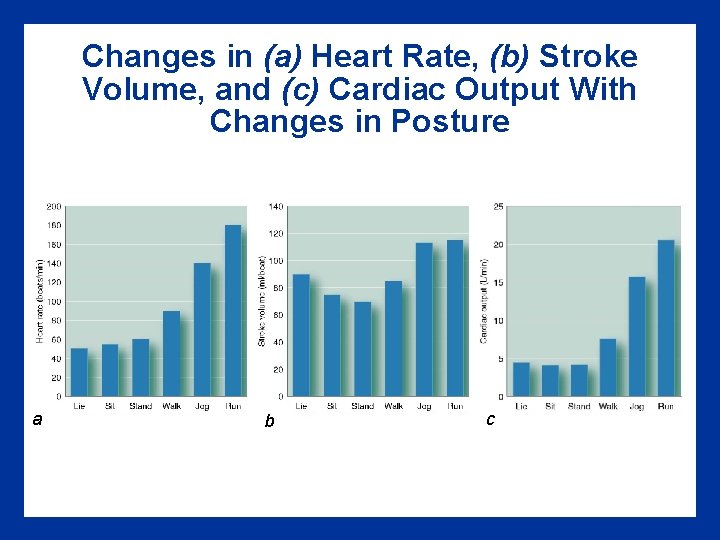

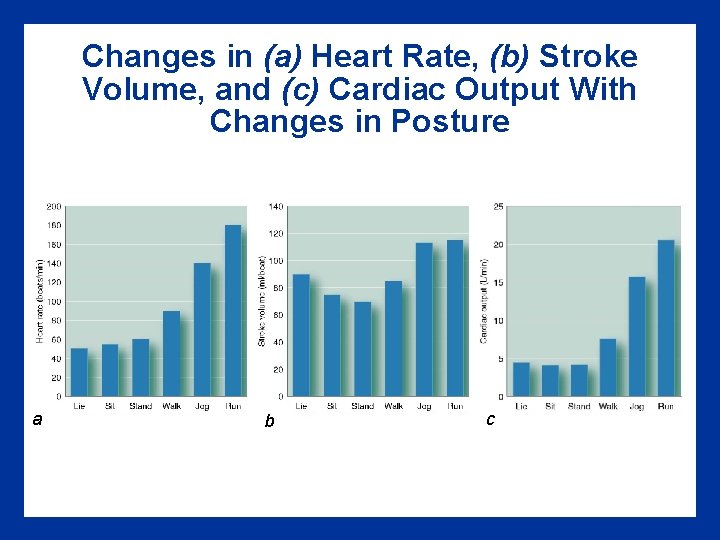

Changes in (a) Heart Rate, (b) Stroke Volume, and (c) Cardiac Output With Changes in Posture a b c

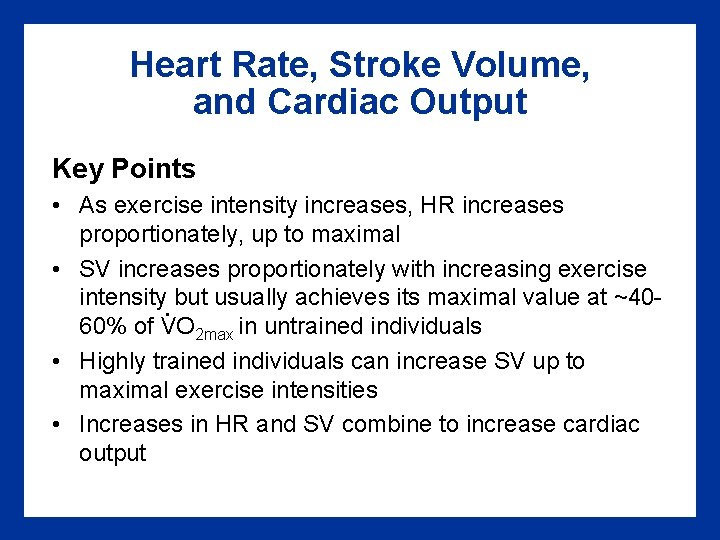

Heart Rate, Stroke Volume, and Cardiac Output Key Points • As exercise intensity increases, HR increases proportionately, up to maximal • SV increases proportionately with increasing exercise intensity. but usually achieves its maximal value at ~4060% of VO 2 max in untrained individuals • Highly trained individuals can increase SV up to maximal exercise intensities • Increases in HR and SV combine to increase cardiac output

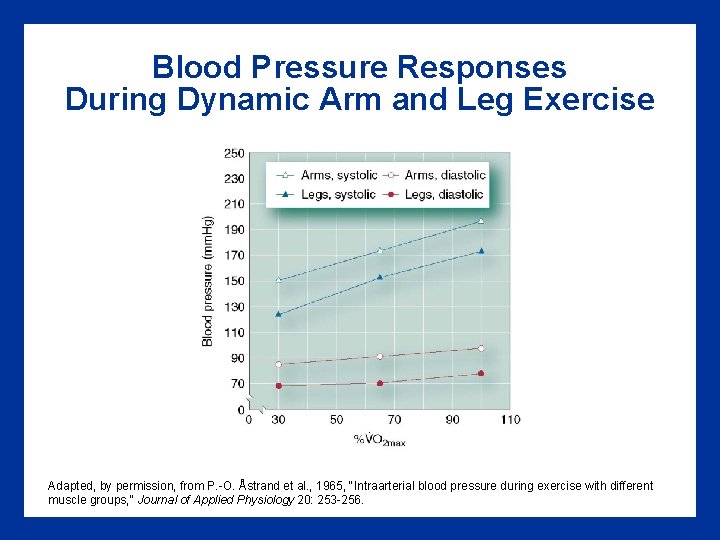

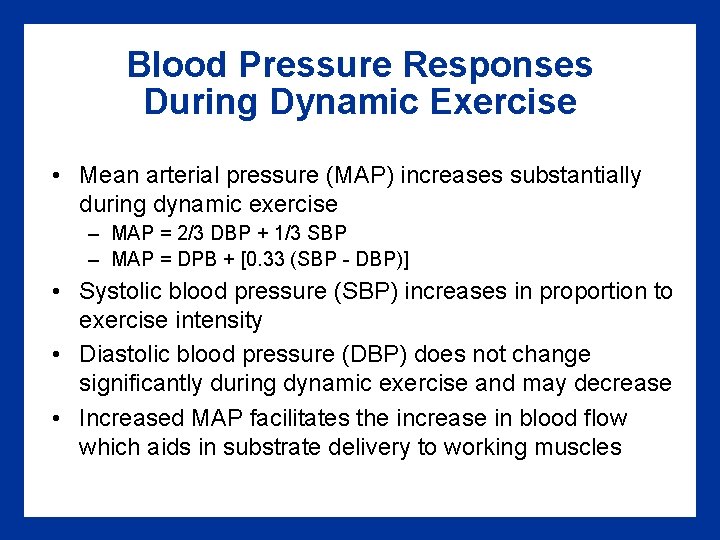

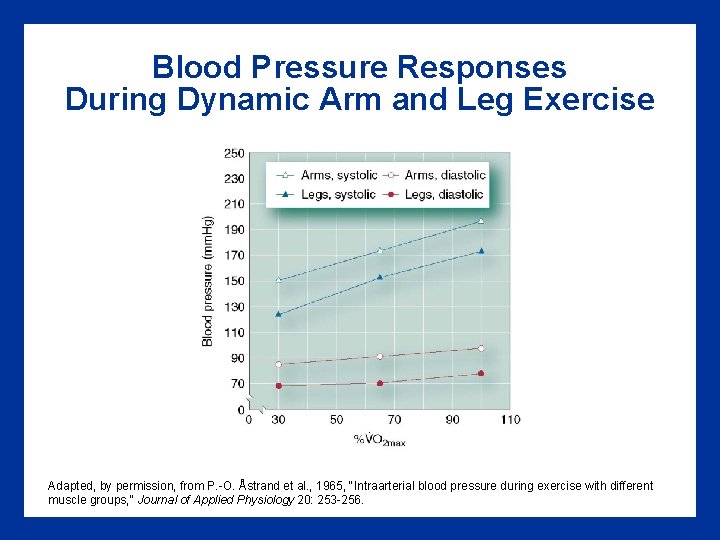

Blood Pressure Responses During Dynamic Exercise • Mean arterial pressure (MAP) increases substantially during dynamic exercise – MAP = 2/3 DBP + 1/3 SBP – MAP = DPB + [0. 33 (SBP - DBP)] • Systolic blood pressure (SBP) increases in proportion to exercise intensity • Diastolic blood pressure (DBP) does not change significantly during dynamic exercise and may decrease • Increased MAP facilitates the increase in blood flow which aids in substrate delivery to working muscles

Blood Pressure Responses During Dynamic Arm and Leg Exercise Adapted, by permission, from P. -O. Åstrand et al. , 1965, "Intraarterial blood pressure during exercise with different muscle groups, " Journal of Applied Physiology 20: 253 -256.

Blood Pressure Responses During Static Exercise • BP responses can be exaggerated during static exercise (as high as 480/350 mm. Hg) • Performing the Valsalva maneuver, which increases BP, is common in these types of exercise (e. g. , lifting very heavy weights)

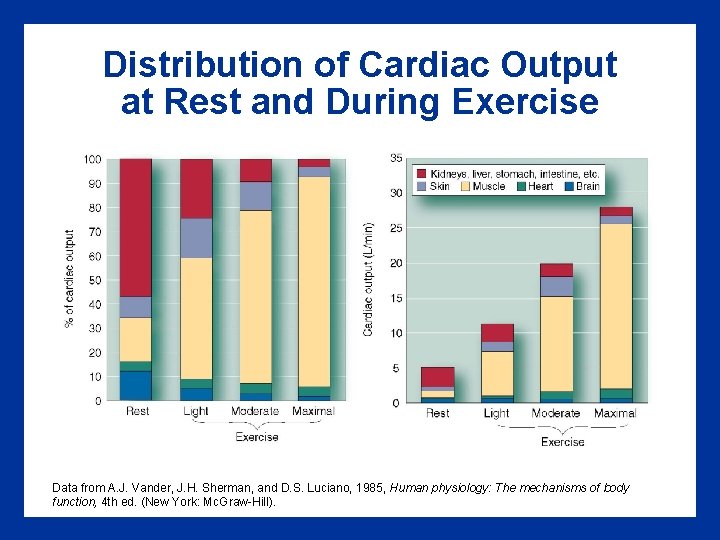

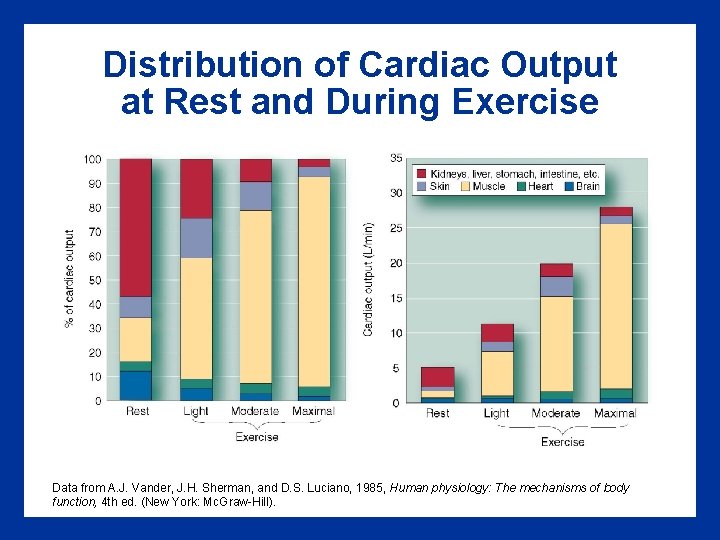

Redistribution of Blood Flow During Exercise • Blood flow is redirected away from areas where elevated flow is not essential to areas that are active during exercise – ↑ Muscle blood flow – ↑ Skin blood flow (especially in hot environments) – ↓ Kidney blood flow – ↓ Splanchnic blood flow (liver, stomach, intestines) • Redistribution of blood flow is accomplished through the actions of the sympathetic nervous system

Distribution of Cardiac Output at Rest and During Exercise Data from A. J. Vander, J. H. Sherman, and D. S. Luciano, 1985, Human physiology: The mechanisms of body function, 4 th ed. (New York: Mc. Graw-Hill).

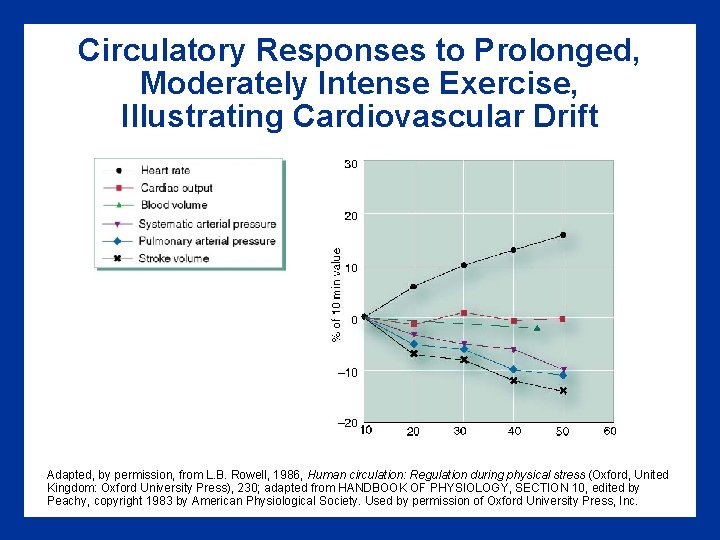

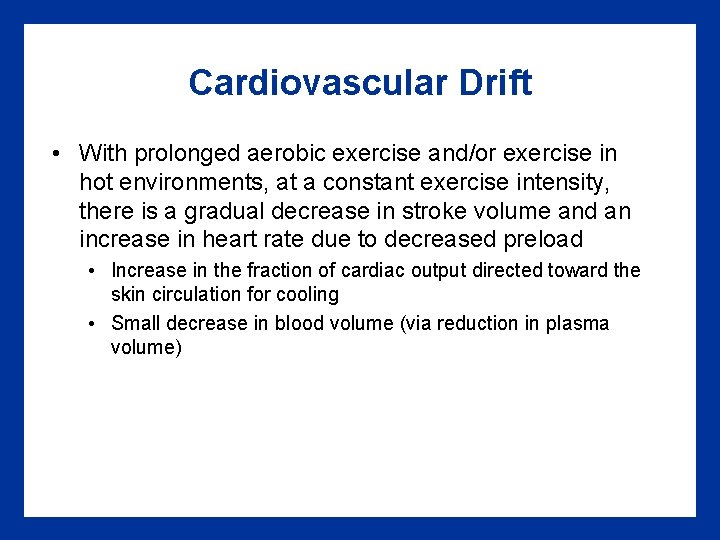

Cardiovascular Drift • With prolonged aerobic exercise and/or exercise in hot environments, at a constant exercise intensity, there is a gradual decrease in stroke volume and an increase in heart rate due to decreased preload • Increase in the fraction of cardiac output directed toward the skin circulation for cooling • Small decrease in blood volume (via reduction in plasma volume)

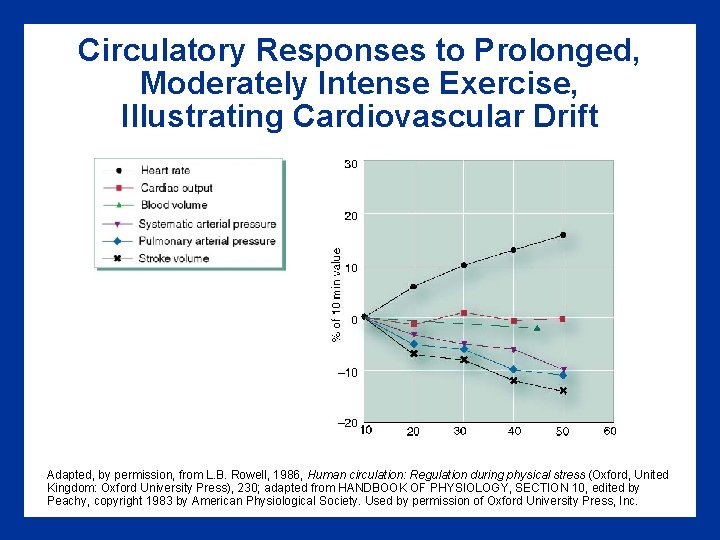

Circulatory Responses to Prolonged, Moderately Intense Exercise, Illustrating Cardiovascular Drift Adapted, by permission, from L. B. Rowell, 1986, Human circulation: Regulation during physical stress (Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press), 230; adapted from HANDBOOK OF PHYSIOLOGY, SECTION 10, edited by Peachy, copyright 1983 by American Physiological Society. Used by permission of Oxford University Press, Inc.

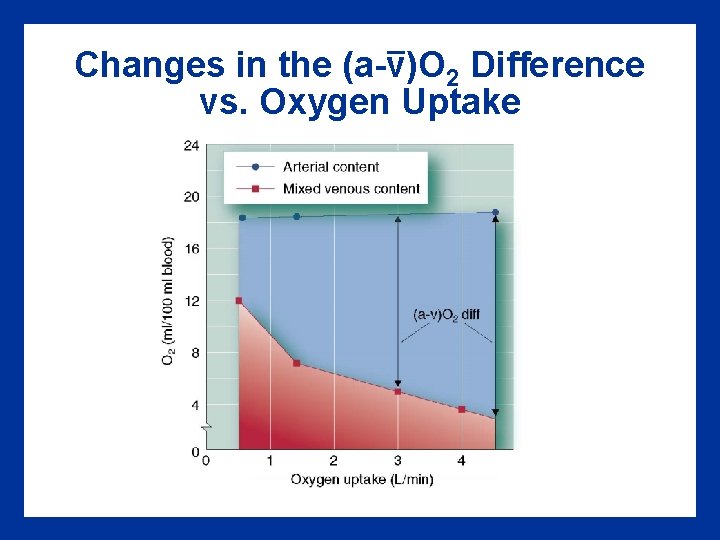

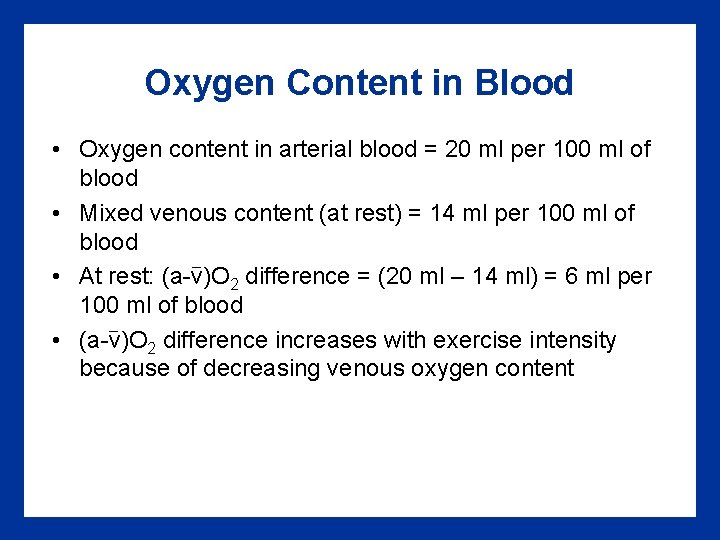

Oxygen Content in Blood • Oxygen content in arterial blood = 20 ml per 100 ml of blood • Mixed venous content (at rest) = 14 ml per 100 ml of blood • At rest: (a-v)O 2 difference = (20 ml – 14 ml) = 6 ml per 100 ml of blood • (a-v)O 2 difference increases with exercise intensity because of decreasing venous oxygen content

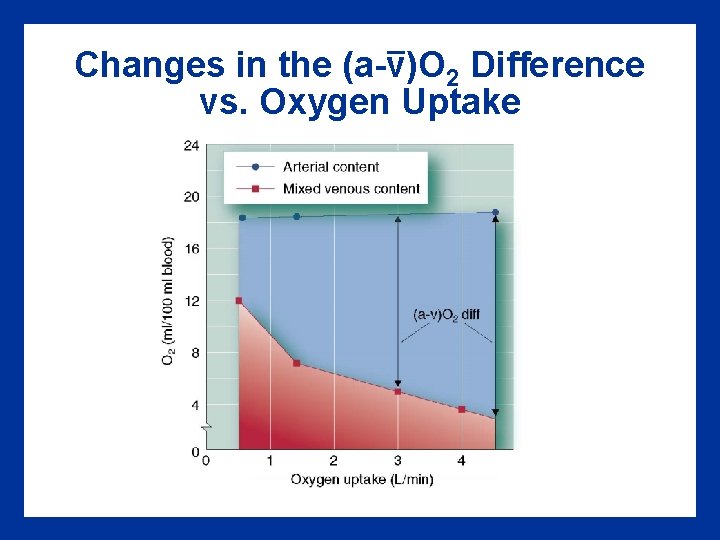

– Changes in the (a-v)O 2 Difference vs. Oxygen Uptake

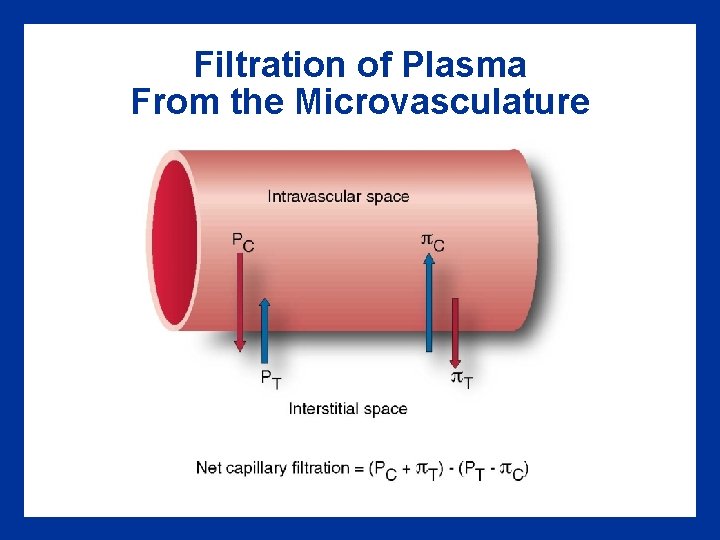

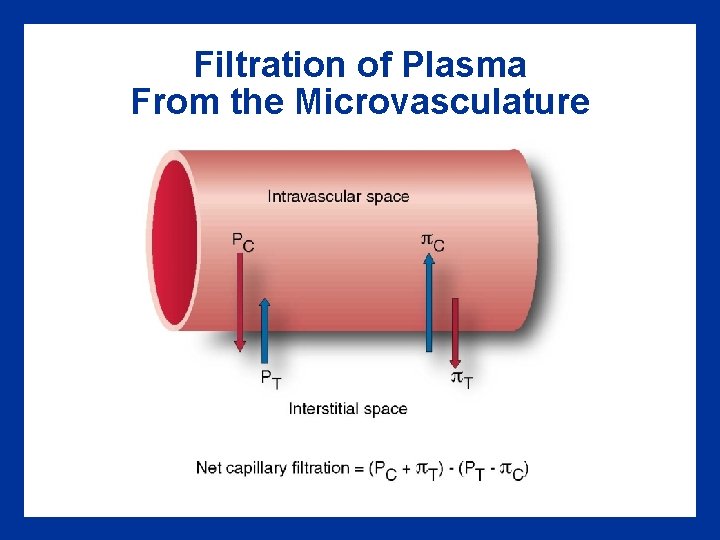

Plasma Volume (PV) During Exercise • • Plasma moves from the blood to the interstitial space PV is lost through sweat, especially in hot environments 10 -15% reduction in PV with prolonged exercise PV loss is proportional to intensity with resistance exercise • Excessive PV loss can result in impaired performance • PV loss results in hemoconcentration (a reduction in the fluid component of the blood)

Filtration of Plasma From the Microvasculature

Blood Pressure, Blood Flow, and Plasma Volume Changes With Exercise Key Points • MAP increases immediately and in proportion to exercise intensity • Endurance exercise: SBP, ↔ DBP • Resistance exercise: SBP, DBP • Blood flow is redistributed during exercise from inactive areas to exercising muscle to meet its metabolic needs • Cardiovascular drift is a progressive decrease in SV and increase in HR during prolonged exercise and/or exercise in the heat (continued)

Blood Pressure, Blood Flow, and Plasma Volume Changes With Exercise (continued) Key Points • The (a-v)O 2 difference increases as venous oxygen concentration decreases during exercise • Plasma volume decreases during exercise through hydrostatic forces and through sweating • Hemoconcentration occurs as plasma volume decreases

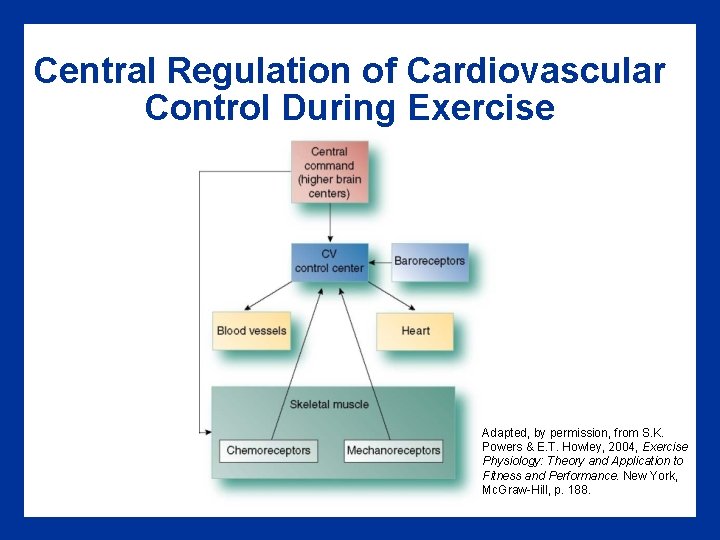

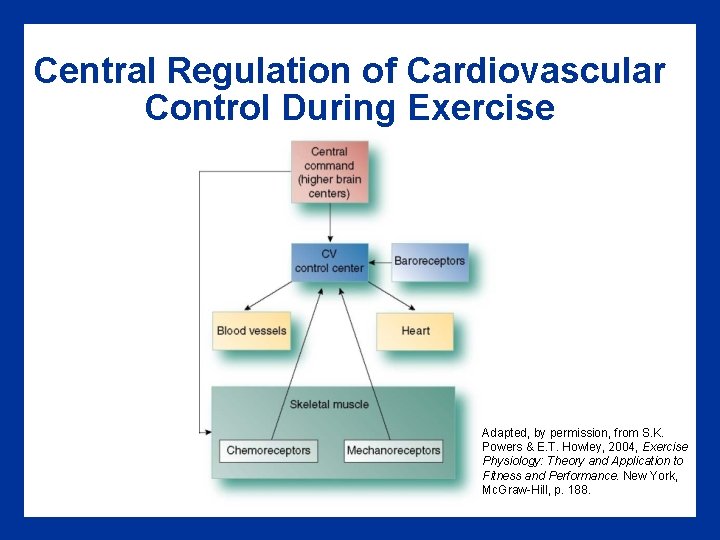

Central Regulation of Cardiovascular Control During Exercise Adapted, by permission, from S. K. Powers & E. T. Howley, 2004, Exercise Physiology: Theory and Application to Fitness and Performance. New York, Mc. Graw-Hill, p. 188.

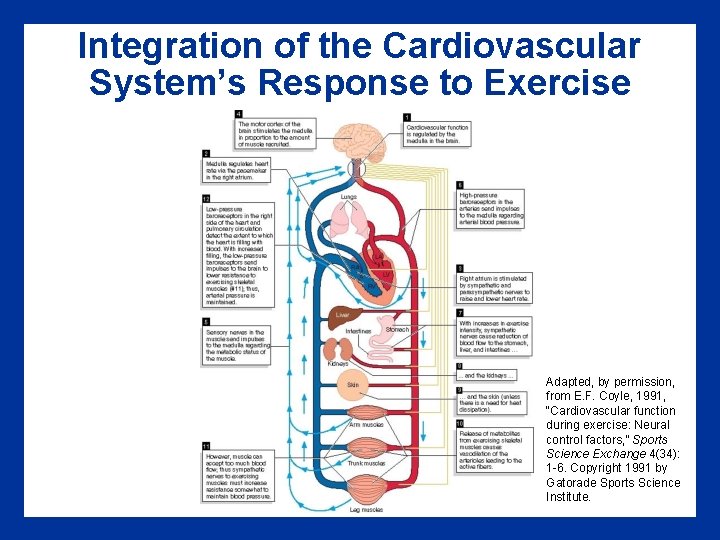

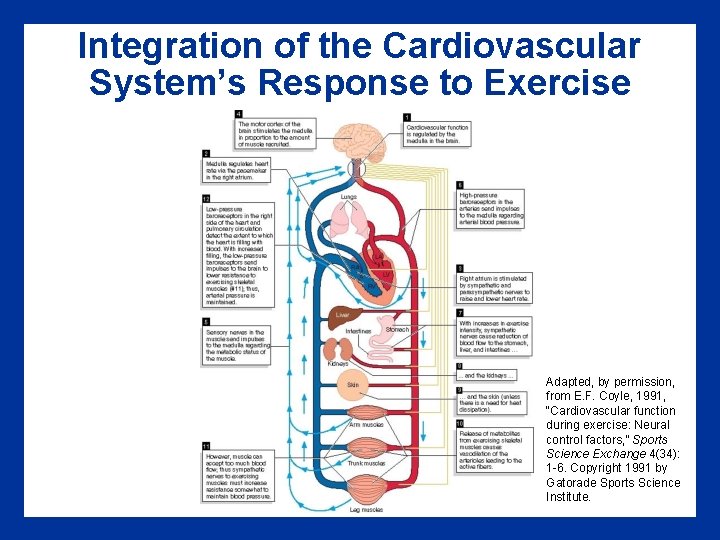

Integration of the Cardiovascular System’s Response to Exercise Adapted, by permission, from E. F. Coyle, 1991, “Cardiovascular function during exercise: Neural control factors, ” Sports Science Exchange 4(34): 1 -6. Copyright 1991 by Gatorade Sports Science Institute.

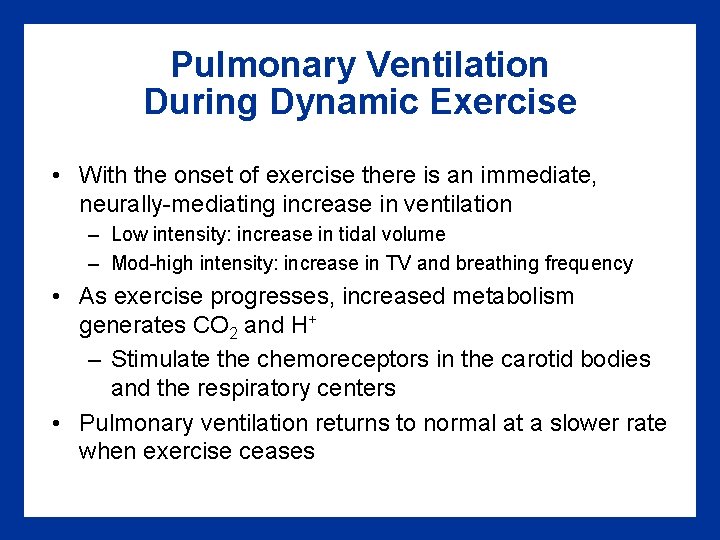

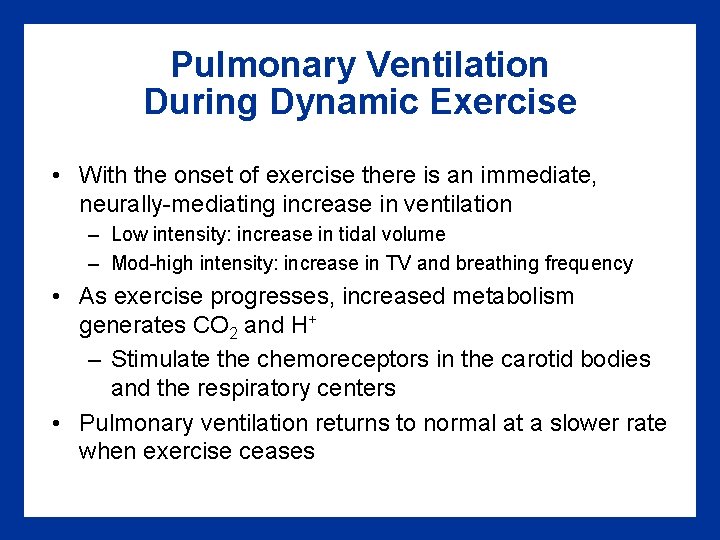

Pulmonary Ventilation During Dynamic Exercise • With the onset of exercise there is an immediate, neurally-mediating increase in ventilation – Low intensity: increase in tidal volume – Mod-high intensity: increase in TV and breathing frequency • As exercise progresses, increased metabolism generates CO 2 and H+ – Stimulate the chemoreceptors in the carotid bodies and the respiratory centers • Pulmonary ventilation returns to normal at a slower rate when exercise ceases

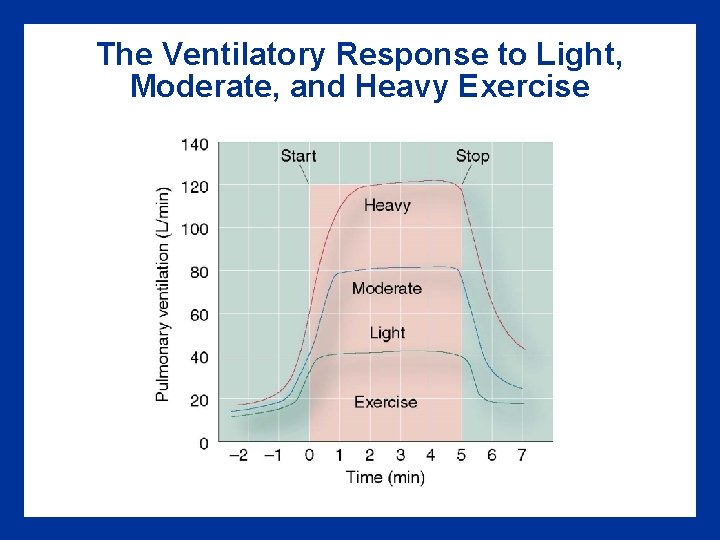

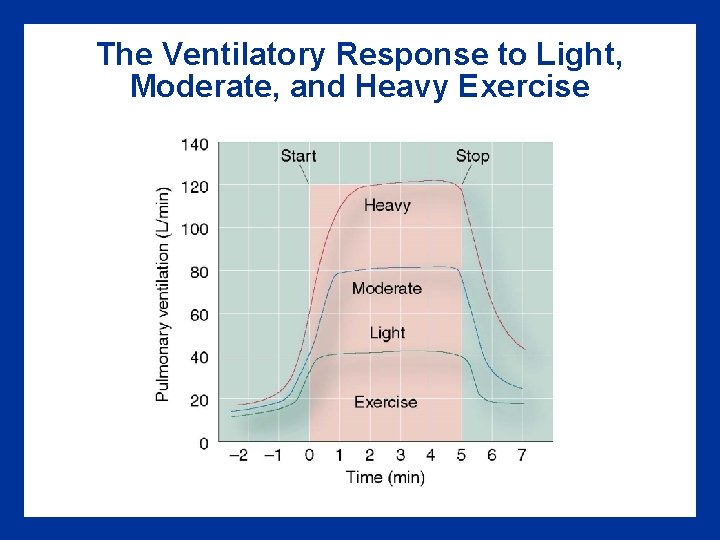

The Ventilatory Response to Light, Moderate, and Heavy Exercise

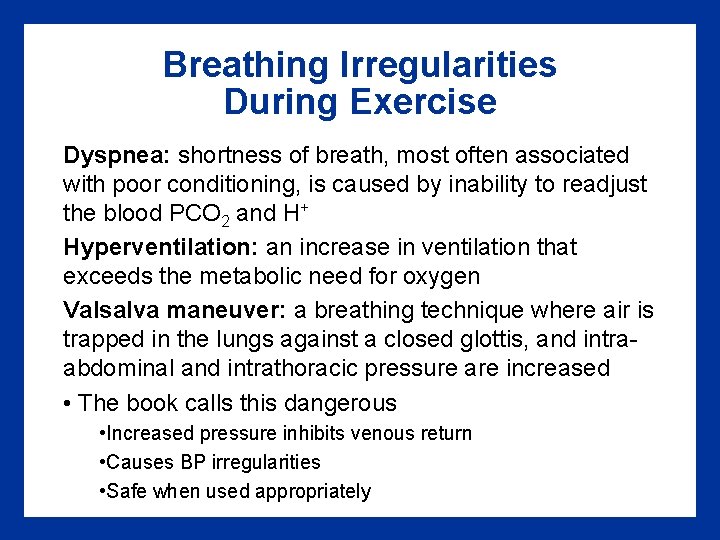

Breathing Irregularities During Exercise Dyspnea: shortness of breath, most often associated with poor conditioning, is caused by inability to readjust the blood PCO 2 and H+ Hyperventilation: an increase in ventilation that exceeds the metabolic need for oxygen Valsalva maneuver: a breathing technique where air is trapped in the lungs against a closed glottis, and intraabdominal and intrathoracic pressure are increased • The book calls this dangerous • Increased pressure inhibits venous return • Causes BP irregularities • Safe when used appropriately

Ventilatory Equivalent for Oxygen • • • . . The ratio between VE and VO 2 (i. e. , hyperventilation) Indicates breathing economy. . Rest VE/VO 2 = 23 to 28 L of air per L O 2. . Maximal exercise VE/VO 2 = 30 L of air L O 2. . Generally VE/VO 2 remains relatively constant over a wide range of exercise levels

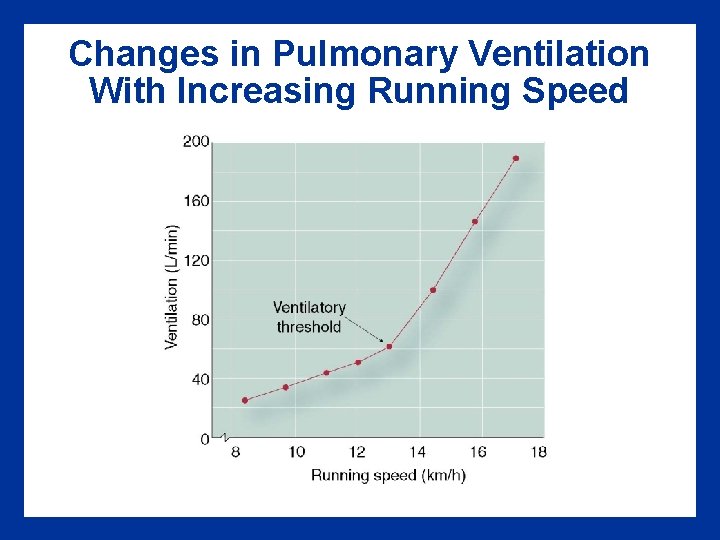

Ventilatory Threshold • Point during exercise when ventilation increases disproportionately to oxygen consumption • At approximately the same point lactate begins to accumulate in the blood • Lactic acid is buffered by sodium bicarbonate and ventilation increases due to increased CO 2 stimulating the chemoreceptors

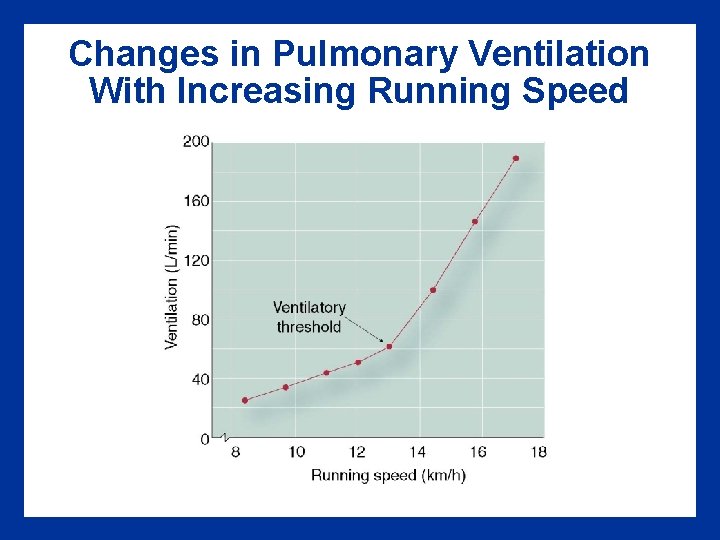

Changes in Pulmonary Ventilation With Increasing Running Speed

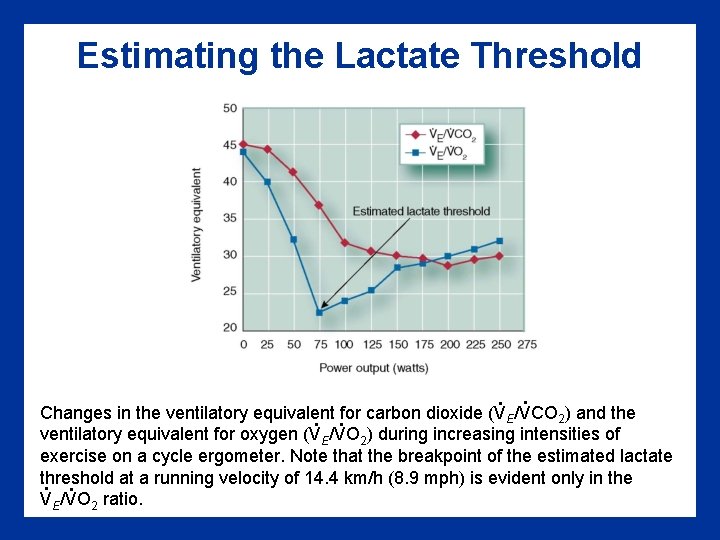

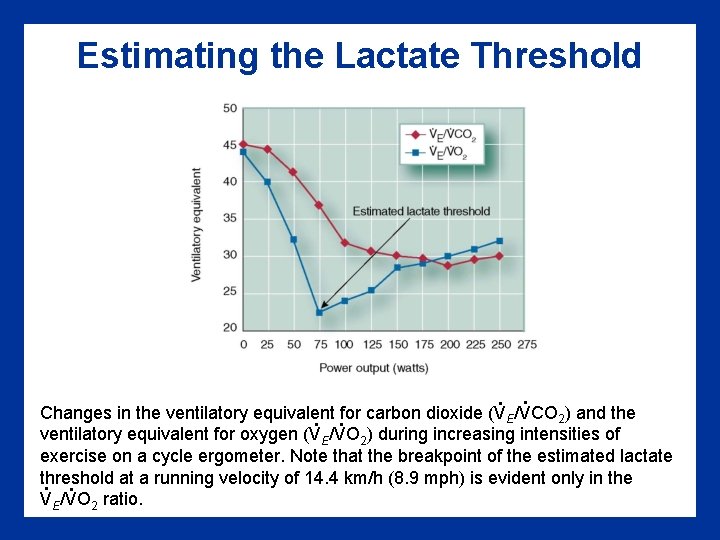

Estimating the Lactate Threshold . . Changes in the ventilatory equivalent for carbon dioxide (V E/VCO 2) and the. . ventilatory equivalent for oxygen (VE/VO 2) during increasing intensities of exercise on a cycle ergometer. Note that the breakpoint of the estimated lactate threshold at a running velocity of 14. 4 km/h (8. 9 mph) is evident only in the. . VE/VO 2 ratio.

Respiratory Limitations to Performance • Respiratory muscles consume ~11% of oxygen consumed during heavy exercise and can receive up to 15% of cardiac output • Pulmonary ventilation is usually not a limiting factor for performance in most individuals • Respiratory muscles have a high oxidative capacity and are relatively fatigue resistant (continued)

Respiratory Limitations to Performance (continued) • Airway resistance and gas diffusion usually do not limit performance in healthy individuals, but they can in people with restrictive or obstructive respiratory disorders • Pulmonary ventilation may limit performance in some highly trained athletes due to exercise-induced arterial hypoxemia – High Q means that blood flows so quickly though the lungs that it may not have time to get fully oxygenated

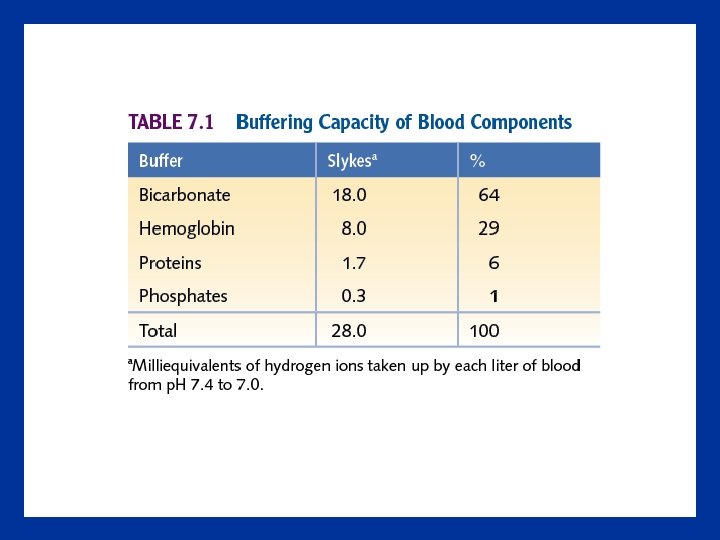

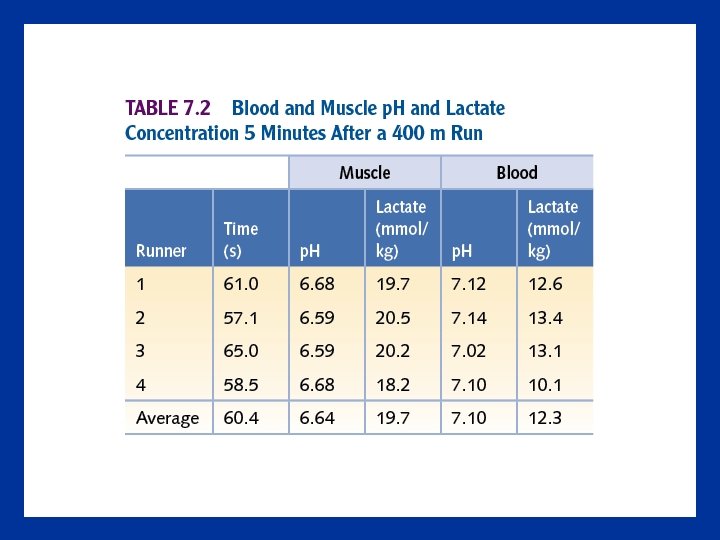

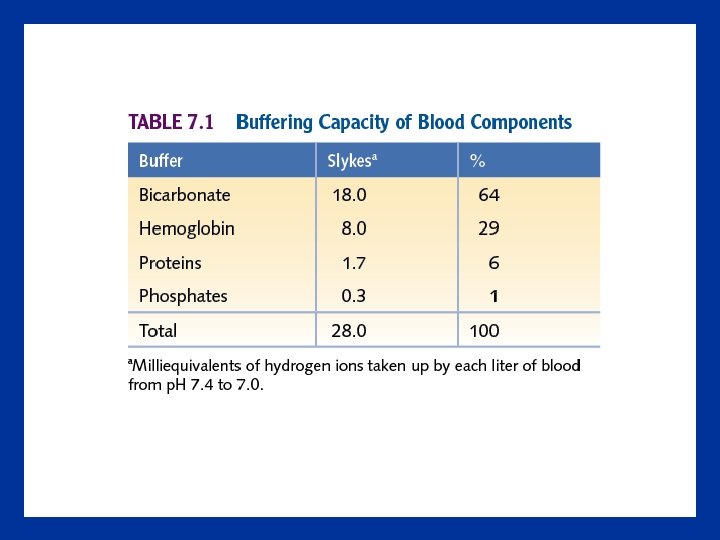

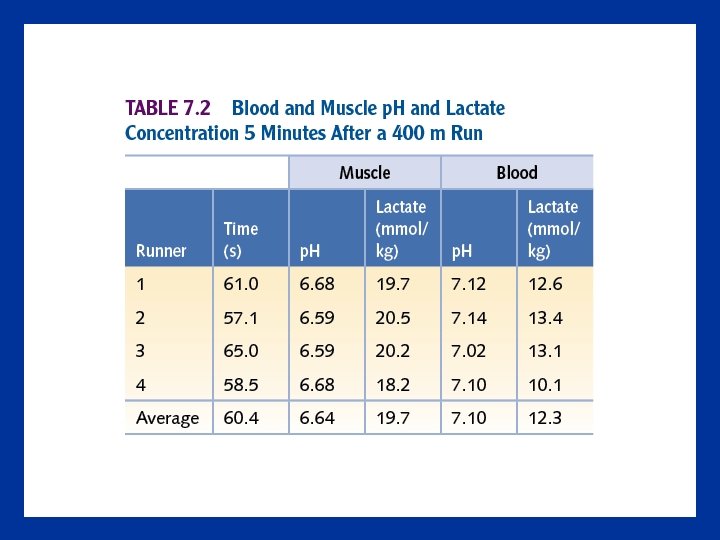

Respiratory Regulation of Acid–Base Balance • • Normal Ph is slightly alkaline: 7. 1 (muscle), 7. 4 (blood) Lactic acid releases H+ (hydrogen ions) H+ + buffer → H-buffer Examples of buffers: – Bicarbonate: combines w/ H+ , forms carbonic acid, which forms CO 2 & water @ the lungs – Phosphate: in muscles & kidneys (excreted in urine) – Proteins – Hemoglobin • Acidosis: H+ concentration above normal • Alkalosis: H+ concentration below normal

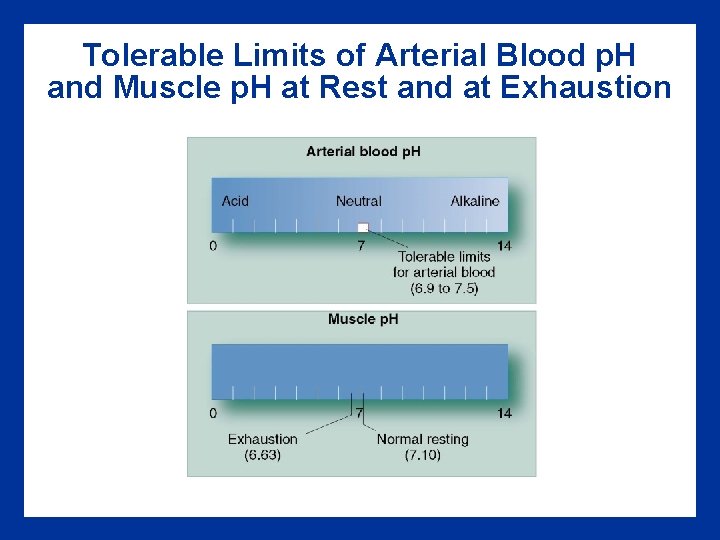

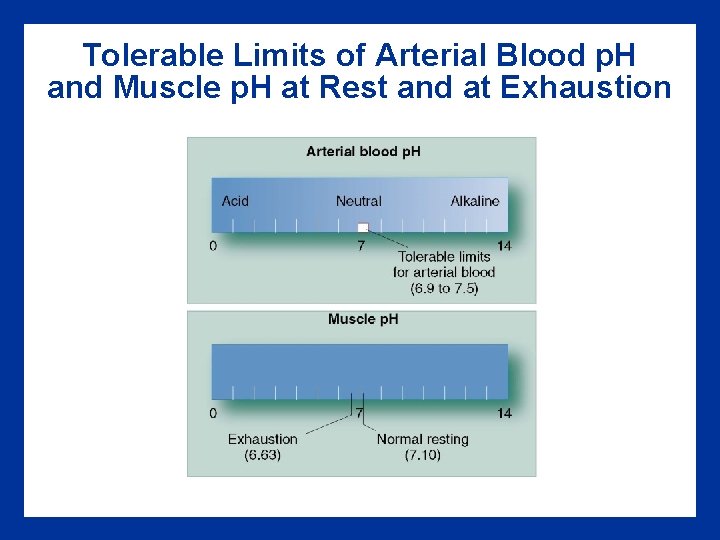

Tolerable Limits of Arterial Blood p. H and Muscle p. H at Rest and at Exhaustion

Regulating p. H • Chemical buffers in the blood • Pulmonary ventilation • Kidney function

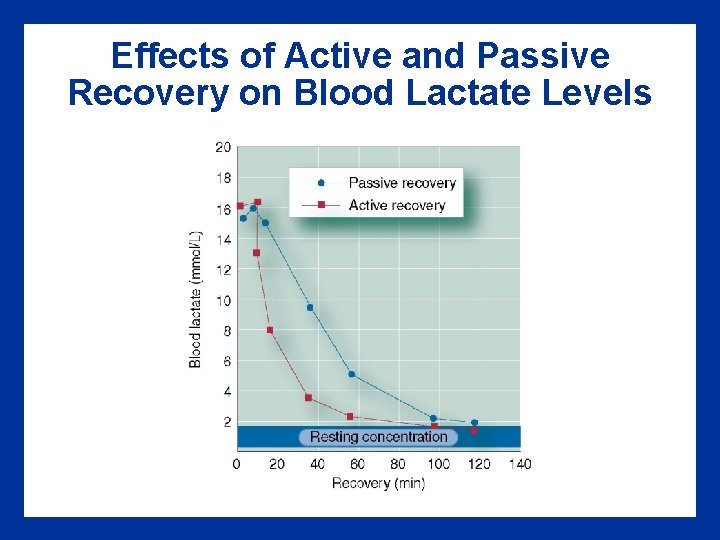

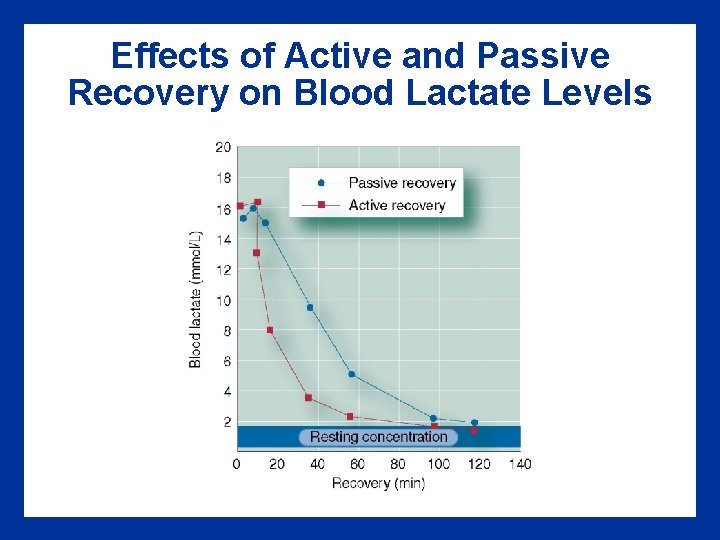

Effects of Active and Passive Recovery on Blood Lactate Levels

Respiratory Regulation of Acid–Base Balance • Excess H+ (decreased p. H) impairs muscle contractility and ATP generation • The respiratory and renal systems help regulate acid– base balance – Respiratory: short-term – Renal: long-term • Increased H+ concentrations stimulate respiratory centers to remove CO 2 • Whenever H+ levels begin to rise, from carbon dioxide or lactate accumulation, bicarbonate ions can buffer the H+ to prevent acidosis