Chapter 6 Learning Classical Conditioning Ivan Pavlov 1901

- Slides: 44

Chapter 6: Learning

Classical Conditioning � Ivan Pavlov (1901) was a Russian physiologist renowned for his work on digestive processes. In the late 1890’s he was doing some r and e (research and experimentation) on canine salivary processes and digestion when he stumbled onto what became the biggest discovery of his career. Ironically enough, it had nothing to do with digestion or physiology. He unwittingly trained his dog subjects to act in an unnatural way toward a previously neutral stimulus. Dogs do not normally salivate to the sound of a bell ringing. However, when Pavlov paired a bell signaling a new subject to enter with a stimulus that would make the dog salivate (meat for example), the animals soon began to salivate before the meat was displayed, because the dog associated the bell and the appearance of the meat together. In the dog’s mind, the bell became synonymous with the meat. In doing so, he discovered classical, sometimes called Pavlovian, conditioning.

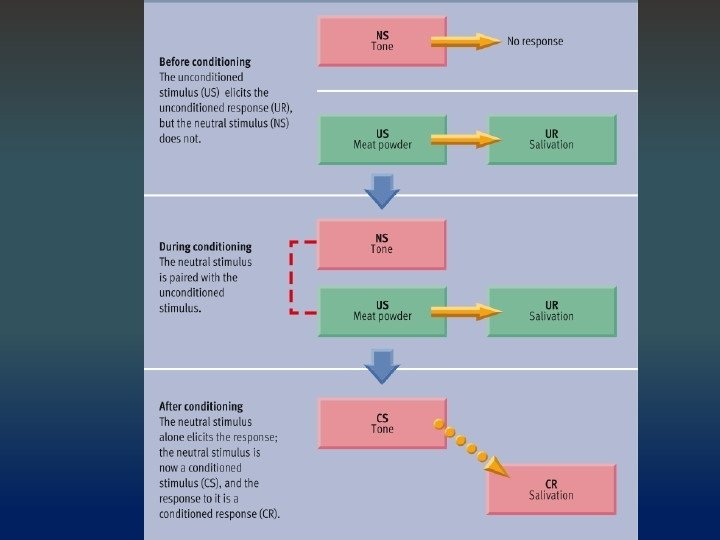

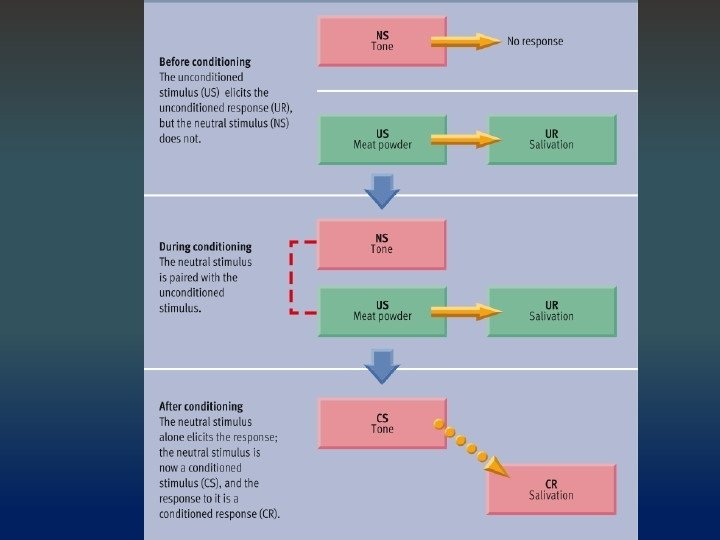

Classical Conditioning � Terminology �Unconditioned Stimulus (UCS) – the stimulus that naturally evokes the desired response �Conditioned Stimulus (CS) – originally, this is a neutral stimulus (NS) the stimulus that doesn’t naturally evoke the desired response; this is the stimulus a trainer must teach the subject to respond to. �Unconditioned Response (UCR) – whenever the unconditioned stimulus is present, any response made by the subject will be unconditioned. A conditioned response only occurs when the UCS is removed and the subject responds to the CS alone. �Conditioned Response (CR) – once the UCS is removed, if the subject performs the desired behavior with only the CS present, we now have a CR. The subject has been trained to respond to the CS in a way that it normally would not (a dog salivating to the sound of a bell for example).

Classical Conditioning There are four steps in the classical conditioning process: 1. The trainer must prove that the CS is neutral. In other words, the CS will not cause the subject to act in the way the trainer is attempting to train the subject to act (i. e. a bell will not, prior to training, cause a dog to salivate). 2. Put the CS and UCS together back to back, causing a response from the subject: CS + UCS >>>>> UCR 3. Repeat step #2 until the association between the bell and the meat is fully ingrained. 4. Remove the UCS and only present the CS to the subject. If the subject continues to respond the same as in step 2, you now have a CR, so… CS >>>> CR See next slide for a demonstration…

Classical Conditioning: Terminology Trial : the initial pairing of a CS and a UCS Acquisition: initial stage in learning, where the subject initially acquires a learned response. Stimulus contiguity: Pavlov and Watson’s notion that the reason the classical conditioning association happens is because the two stimuli (CS and UCS) occur closely together in time and space. Stimulus continuity: Robert Rescorla put forth an alternative view of why the classical conditioning association happens. He said that, in part, Watson and Pavlov were correct, but that there is another factor involved as well. Rescorla proposed that another reason why the learned association happens is because the CS reliably predicts the UCS (the dog learned, for example, that the bell predicted or announced that the meat would be along presently!)

Classical Conditioning Paradigms Simultaneous conditioning: CS and UCS begin and end at the same time. Delayed conditioning: UCS begins just as the CS ends, no gap between the two, seamless. This is the best of the paradigms. Trace conditioning: CS begins and ends before UCS is presented. There is a gap between the two, gap can be as long as the experimenter wants it to be. The longer the gap in time, the weaker the association. Temporal conditioning: Time becomes the CS Backward conditioning: UCS is presented before the CS Delayed conditioning promotes acquisition best. Trace conditioning can also be effective; ideally the delay between the end of the CS and the beginning of the UCS should be very brief, less than a second is best. The worst option is backward conditioning; in effect, it reverses the stimuli, and the order of presentation prevents the desired association from forming.

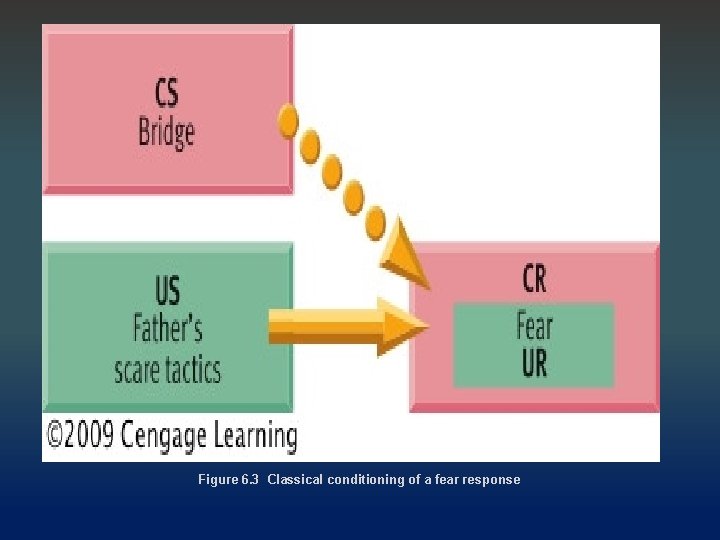

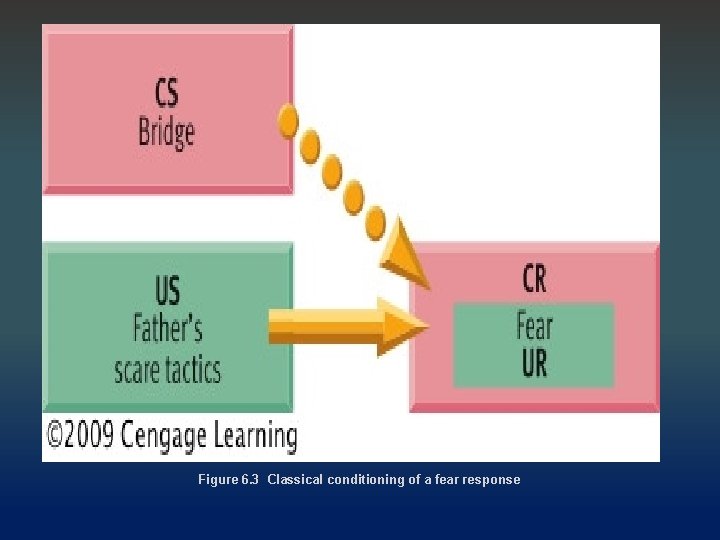

Classical Conditioning in Everyday Life Conditioned emotional responses can become a problem as people grow and develop. Often, experiences in life (conditioned stimuli) are accompanied by other events (unconditioned stimuli) that cause unnatural responses (conditioned responses). For example, say you’re 6 yrs. old and a dog comes up to you (CS). The dog then bites your booty (UCS). After this traumatic event, you now might learn to fear dogs (CR). Conditioning with drug effects is also commonplace. Let’s say you take a pill (CS), it makes you feel good (UCS) so you take more and more pills afterward (CR).

Figure 6. 3 Classical conditioning of a fear response

Processes in Classical Conditioning Acquisition is when the initial learning of a new behavior occurs. Extinction occurs when the CS and UCS are no longer paired and the response to the CS weakens and then disappears. We know that the learned response is still there somewhere in the mind of the subject, but it’s no longer active. We know this because of spontaneous recovery, when an extinguished response rapidly reappears after retraining. The renewal effect occurs if a response is extinguished in a different environment than it was acquired and the extinguished response reappears if the subject is returned to the original environment where acquisition took place. This is one of the reasons why conditioned fears and phobias are difficult to extinguish permanently.

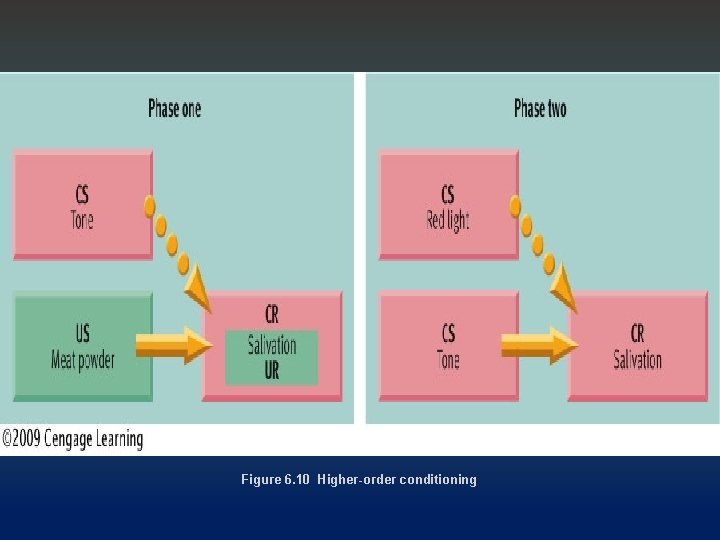

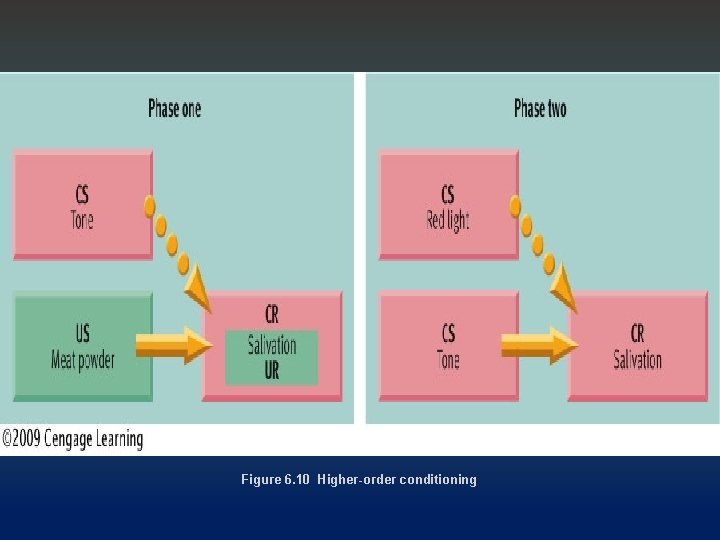

Processes in Classical Conditioning Generalization occurs when conditioning generalizes to additional stimuli that are similar to the CS; for example, recall Watson and Rayner’s Little Albert, who was conditioned to fear a white rat but later came to be afraid of all furry white objects. Discrimination is the opposite of generalization; that is, the response is to a specific stimulus and there is no response to similar stimuli. Higher order conditioning occurs when a CS functions as if it were a UCS to establish new conditioning. This condition can be used to stack CS’s on top of one another. For example, if after training the dogs Pavlov had initiated a green light prior to the bell ringing, the dogs would have learned to salivate to the light before the bell or meat was displayed.

Figure 6. 10 Higher-order conditioning

Operant Conditioning Edward L. Thorndike (1913) wrote about his experiments with cats (Cat in the Puzzle Box) in his doctoral dissertation. He discussed what he referred to as the law of effect, the idea that animals continue to act in ways that have provided favorable consequences for them in the past and are less likely to repeat behaviors that have led to unfavorable consequences in the past. He called this “instrumental learning”. This law later became the cornerstone of Skinner’s operant conditioning theory.

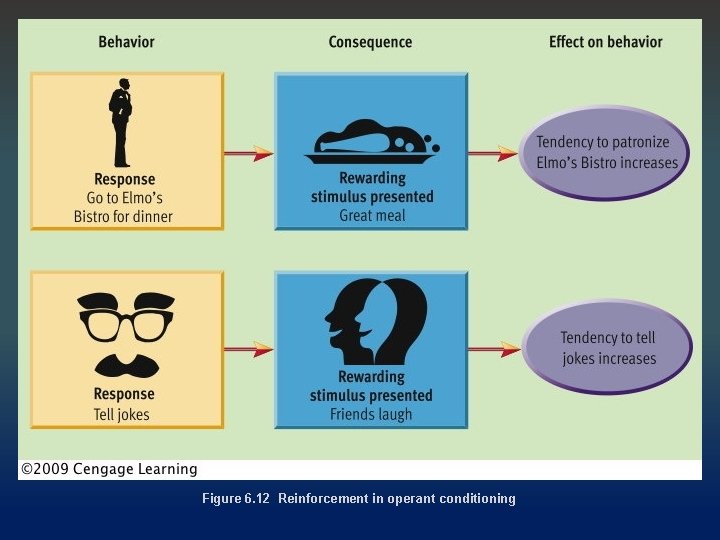

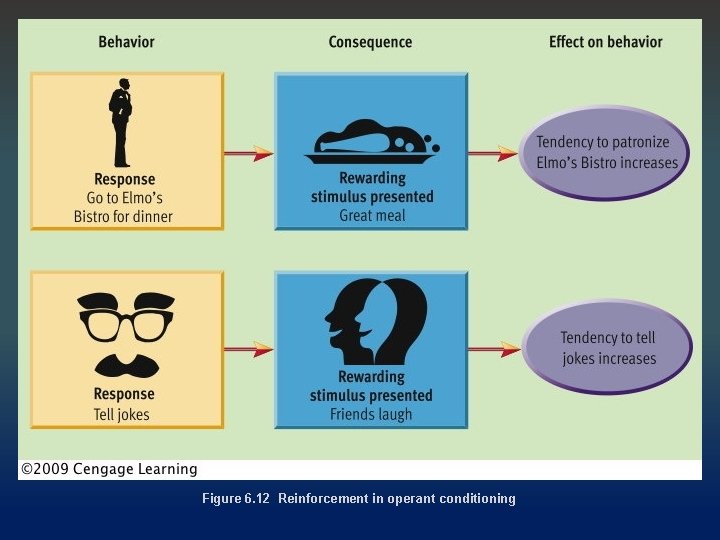

Operant Conditioning B. F. Skinner (1953) the law of effect was the root idea of his theory of operant conditioning. The other main ideas were the principles of reinforcement and punishment. Skinner’s principle of reinforcement holds that organisms tend to repeat those responses that are followed by favorable consequences, which he referred to as reinforcement. Skinner defined reinforcement as when an event following a response increases an organism’s tendency to make that response.

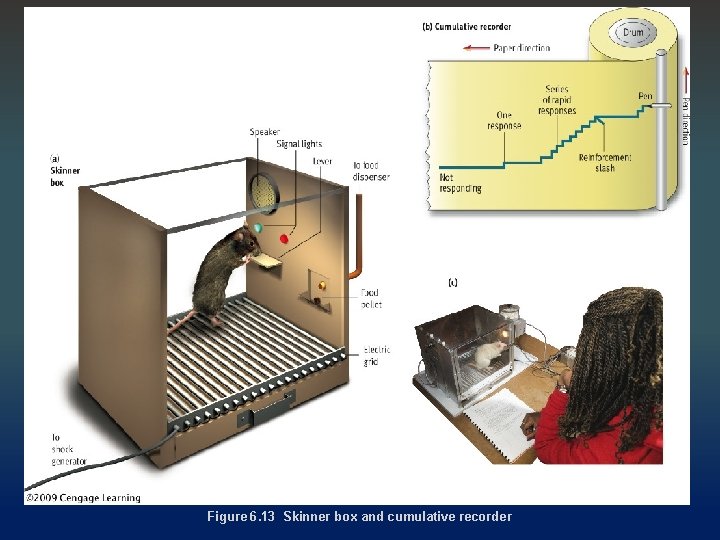

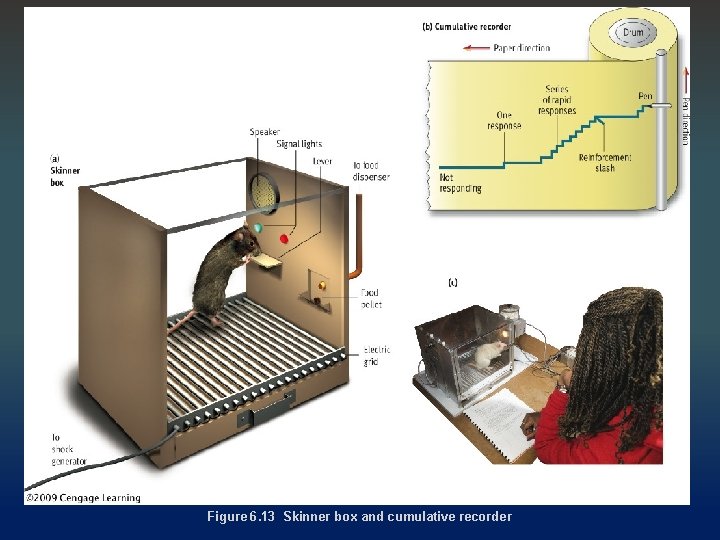

Operant Conditioning Operant chambers (Skinner Boxes): Skinner created a prototype experimental procedure, using animals and an operant chamber or “Skinner box. ” This is a small enclosure in which an animal can make a specific response that is recorded, while the consequences of the response are systematically controlled. Rats, for example, press a lever. Emission of response: Because operant responses tend to be voluntary, they are said to be emitted rather than elicited. Reinforcement contingencies are the circumstances, or rules, that determine whether responses lead to the presentation of reinforcers. Cumulative recorders create a graphic record of responding and reinforcement in a Skinner box as a function of time (how many responses/reinforcements in a set amount of time).

Figure 6. 12 Reinforcement in operant conditioning

Figure 6. 13 Skinner box and cumulative recorder

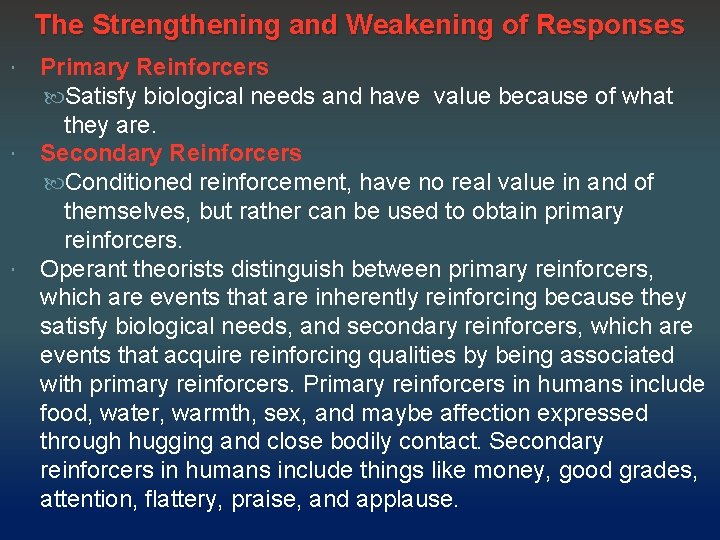

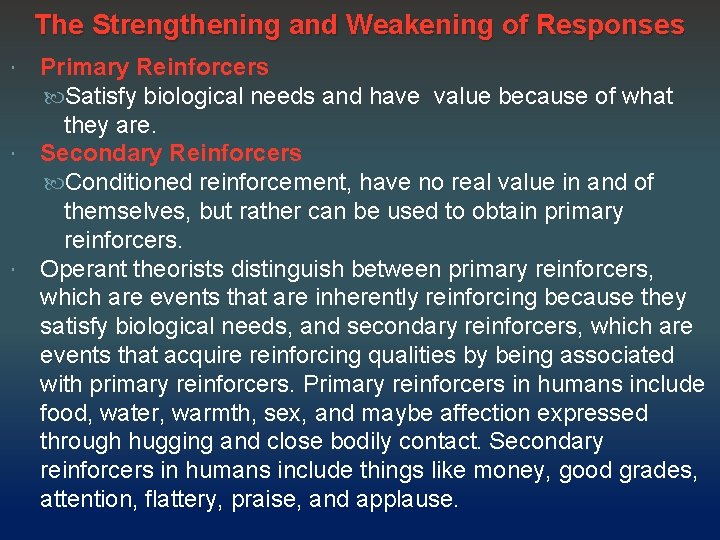

The Strengthening and Weakening of Responses Primary Reinforcers Satisfy biological needs and have value because of what they are. Secondary Reinforcers Conditioned reinforcement, have no real value in and of themselves, but rather can be used to obtain primary reinforcers. Operant theorists distinguish between primary reinforcers, which are events that are inherently reinforcing because they satisfy biological needs, and secondary reinforcers, which are events that acquire reinforcing qualities by being associated with primary reinforcers. Primary reinforcers in humans include food, water, warmth, sex, and maybe affection expressed through hugging and close bodily contact. Secondary reinforcers in humans include things like money, good grades, attention, flattery, praise, and applause.

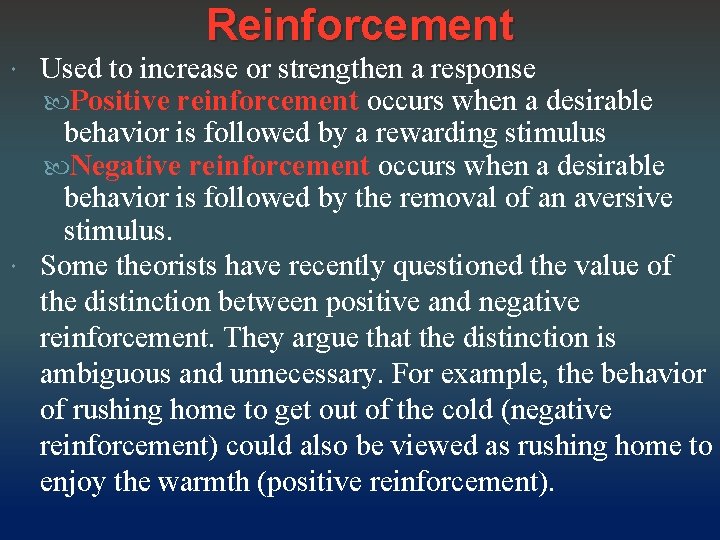

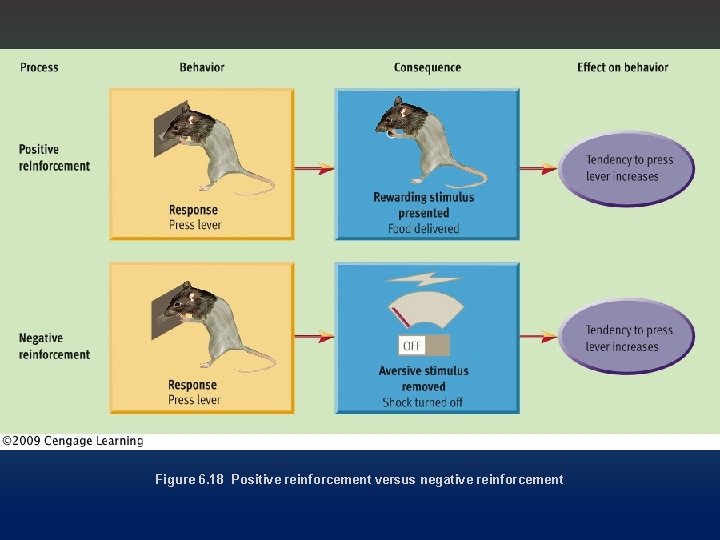

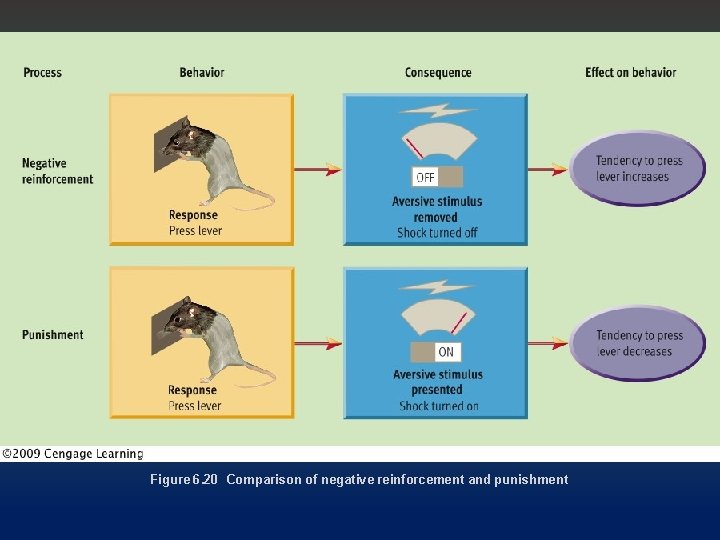

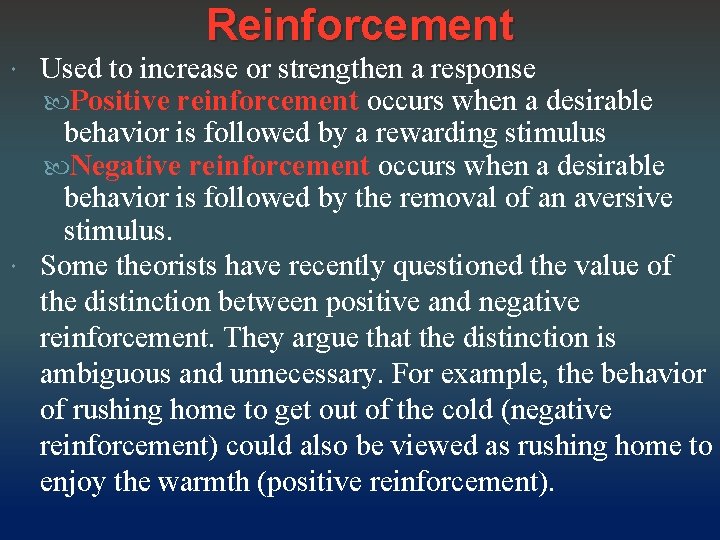

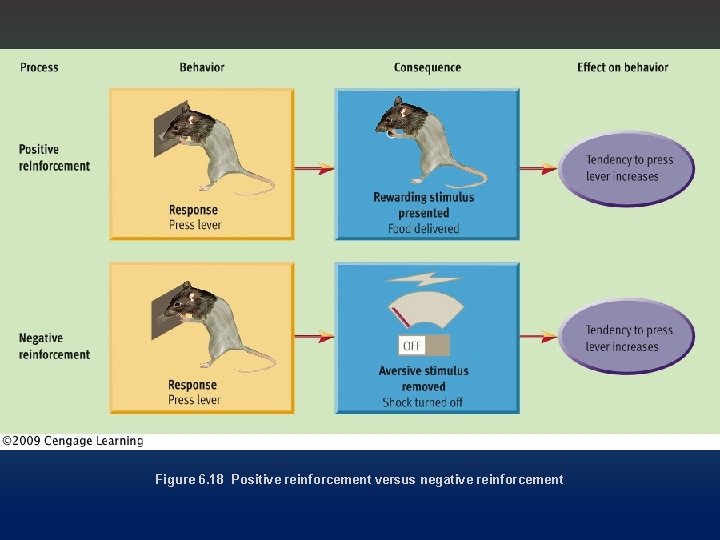

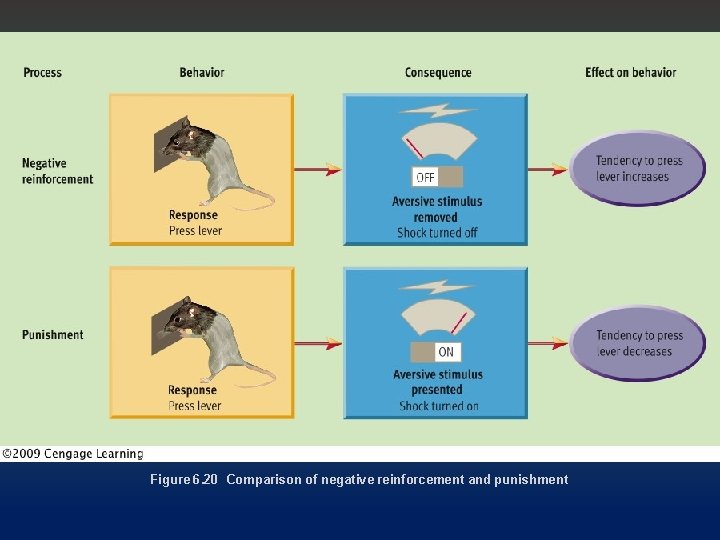

Reinforcement Used to increase or strengthen a response Positive reinforcement occurs when a desirable behavior is followed by a rewarding stimulus Negative reinforcement occurs when a desirable behavior is followed by the removal of an aversive stimulus. Some theorists have recently questioned the value of the distinction between positive and negative reinforcement. They argue that the distinction is ambiguous and unnecessary. For example, the behavior of rushing home to get out of the cold (negative reinforcement) could also be viewed as rushing home to enjoy the warmth (positive reinforcement).

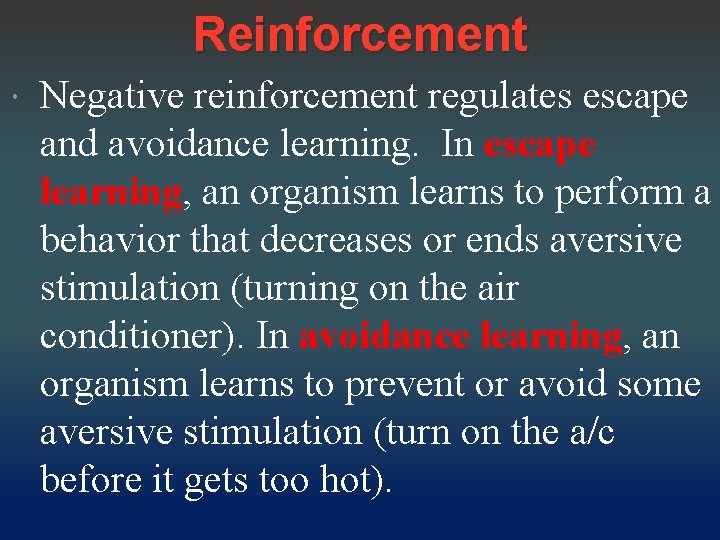

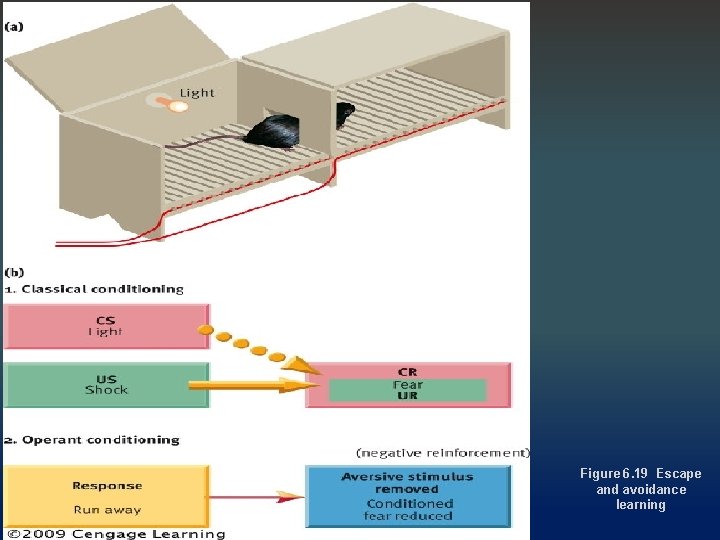

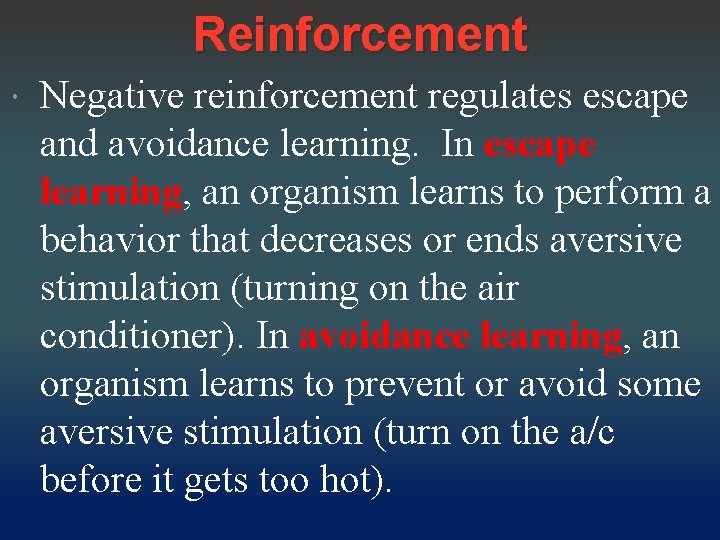

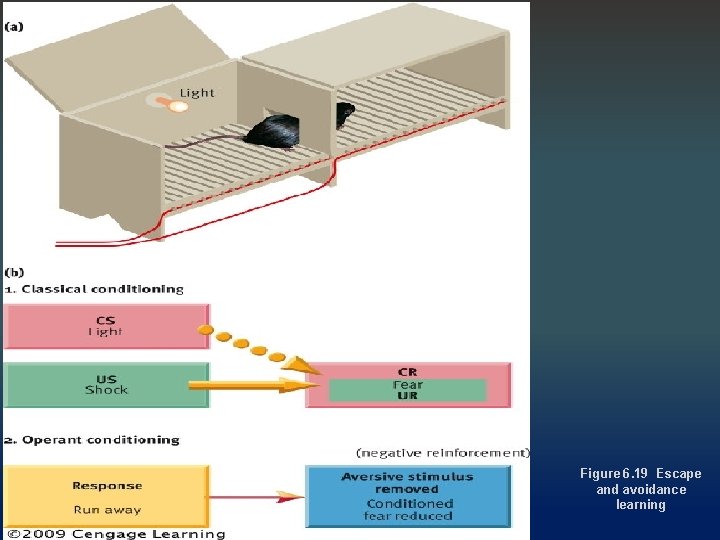

Reinforcement Negative reinforcement regulates escape and avoidance learning. In escape learning, an organism learns to perform a behavior that decreases or ends aversive stimulation (turning on the air conditioner). In avoidance learning, an organism learns to prevent or avoid some aversive stimulation (turn on the a/c before it gets too hot).

Figure 6. 18 Positive reinforcement versus negative reinforcement

Figure 6. 19 Escape and avoidance learning

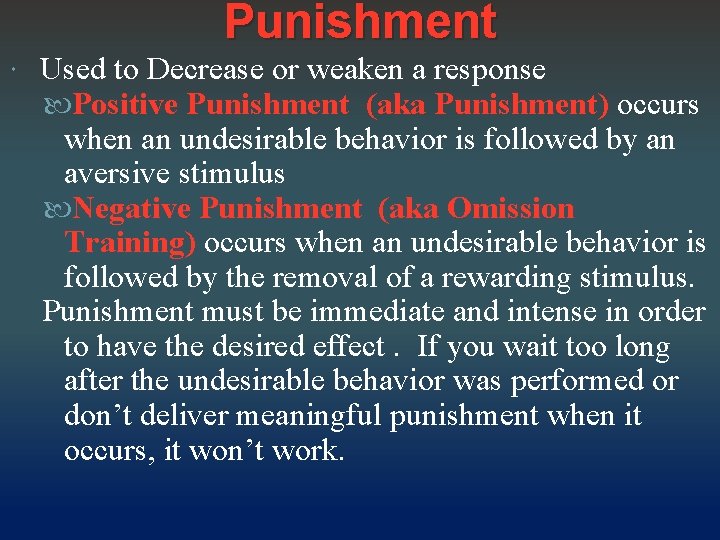

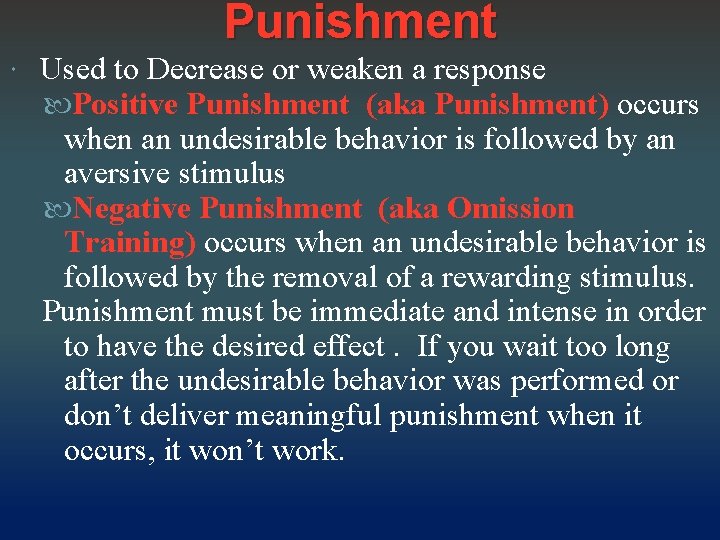

Punishment Used to Decrease or weaken a response Positive Punishment (aka Punishment) occurs when an undesirable behavior is followed by an aversive stimulus Negative Punishment (aka Omission Training) occurs when an undesirable behavior is followed by the removal of a rewarding stimulus. Punishment must be immediate and intense in order to have the desired effect. If you wait too long after the undesirable behavior was performed or don’t deliver meaningful punishment when it occurs, it won’t work.

Figure 6. 20 Comparison of negative reinforcement and punishment

Problems With Using Punishment in Training Problems with using punishment as a training tool 1. PUNISHMENT OFTEN FAILS TO STOP, AND CAN EVEN INCREASE THE OCCURRENCE OF, THE UNDESIRED RESPONSE. Since attention is one of the most potent rewards available, and since it is difficult to punish without paying attention to the offender, punishing may serve more as a reward than as a punishment. 2. PUNISHMENT AROUSES STRONG EMOTIONAL RESPONSES THAT MAY GENERALIZE. Once the strong emotional responses are aroused the degree and direction of generalization is largely uncontrollable. The result may be excessive anxiety, apprehension, guilt, and selfpunishment.

Reinforcement vs. Punishment Strengthening and Weakening of Responses 3. USING PUNISHMENT MODELS AGGRESSION. The meaning of "social power is exemplified. 4. INTERNAL CONTROL OF BEHAVIOR IS NOT LEARNED. The offender may learn to inhibit the punished response during surveillance, but once surveillance ends there is no internal control mechanism to continue inhibiting the behavior. 5. PUNISHMENT CAN EASILY BECOME ABUSE. Most parents who abuse children do not intend to do the damage they inflict. Most of the damage and injury occurs when the parent loses control, and goes beyond the boundaries of reasonable behavior.

Reinforcement vs. Punishment Strengthening and Weakening of Responses 6. PAIN IS STRONGLY ASSOCIATED WITH AGGRESSION. The pain of punishment often leads to a display of aggression against either the source of the pain or, in some cases, an innocent scapegoat. 7. PUNISHMENT WORKS BEST WHEN IT OCCURS EVERY TIME. While reward works best when given on an intermittent basis, punishment works best when a continuous basis. The degree of vigilance required to constantly monitor behavior so that every occurrence of the undesired behavior can be punished is rarely possible. The undesired behavior is, therefore, intermittently reinforced when it is not punished, and the behavior continues.

Operant Conditioning - Basic Processes � Shaping: gradually bringing the subject closer and closer to the desired behavior by rewarding successive approximations of the desired behavior. � Chaining: linking together individually shaped behaviors to form a more complex behavior � Think of a child learning to potty train. There are several steps that must be learned in sequence in order to perform the whole task properly. A parent will shape individual behaviors and then chain them together in a sequence, ending with washing hands.

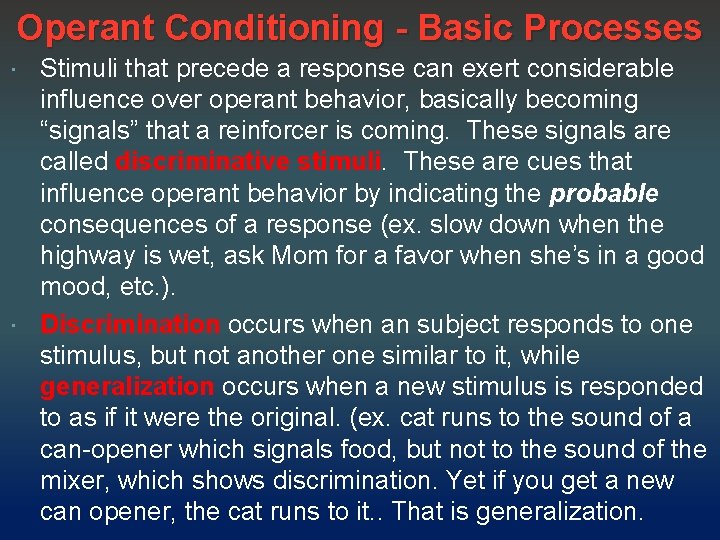

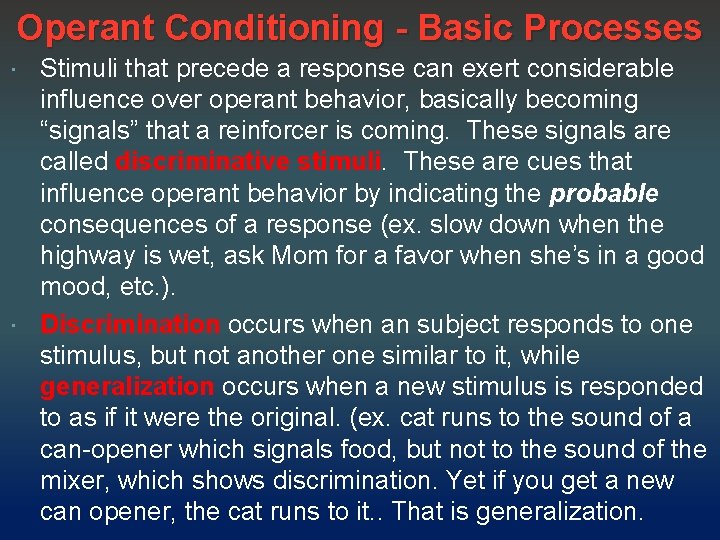

Operant Conditioning - Basic Processes Stimuli that precede a response can exert considerable influence over operant behavior, basically becoming “signals” that a reinforcer is coming. These signals are called discriminative stimuli. These are cues that influence operant behavior by indicating the probable consequences of a response (ex. slow down when the highway is wet, ask Mom for a favor when she’s in a good mood, etc. ). Discrimination occurs when an subject responds to one stimulus, but not another one similar to it, while generalization occurs when a new stimulus is responded to as if it were the original. (ex. cat runs to the sound of a can-opener which signals food, but not to the sound of the mixer, which shows discrimination. Yet if you get a new can opener, the cat runs to it. . That is generalization.

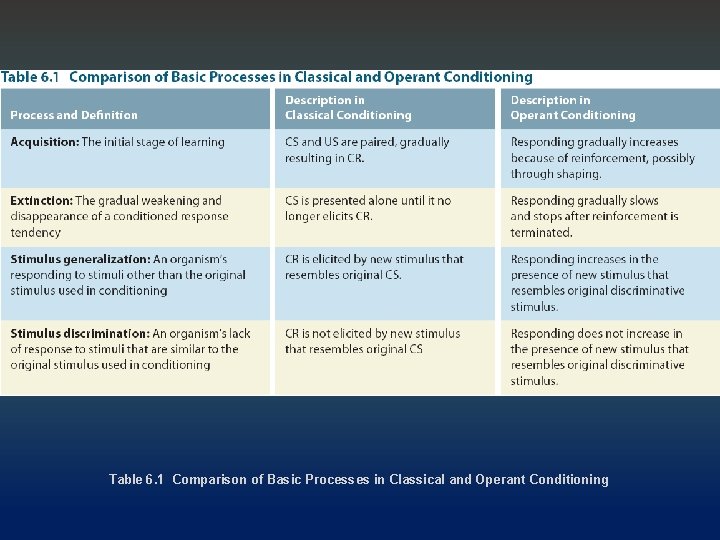

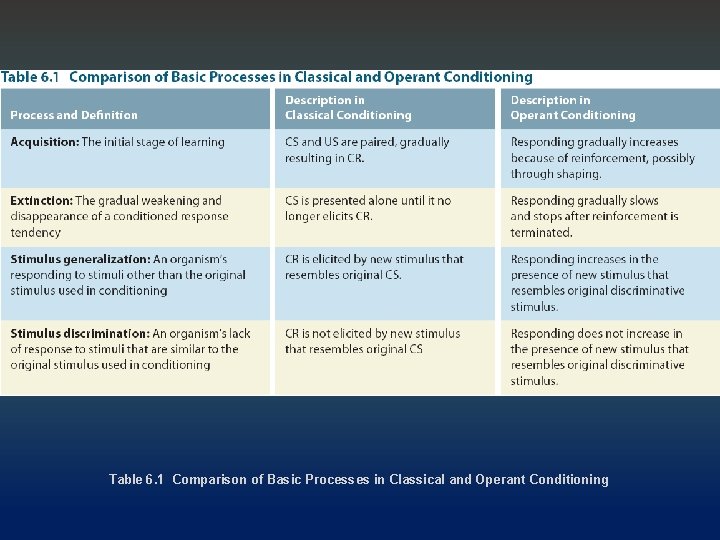

Table 6. 1 Comparison of Basic Processes in Classical and Operant Conditioning

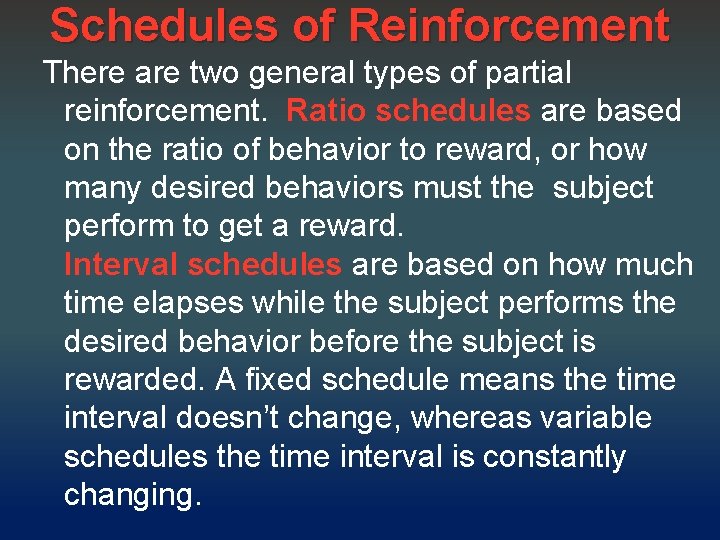

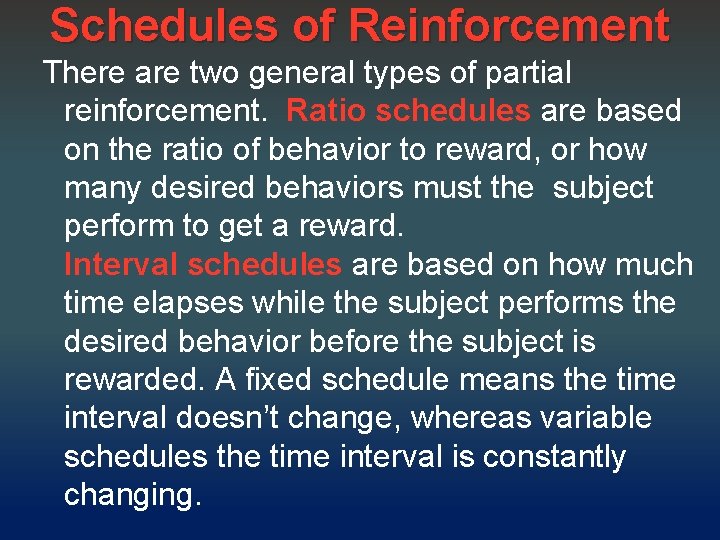

Schedules of Reinforcement There are two general types of partial reinforcement. Ratio schedules are based on the ratio of behavior to reward, or how many desired behaviors must the subject perform to get a reward. Interval schedules are based on how much time elapses while the subject performs the desired behavior before the subject is rewarded. A fixed schedule means the time interval doesn’t change, whereas variable schedules the time interval is constantly changing.

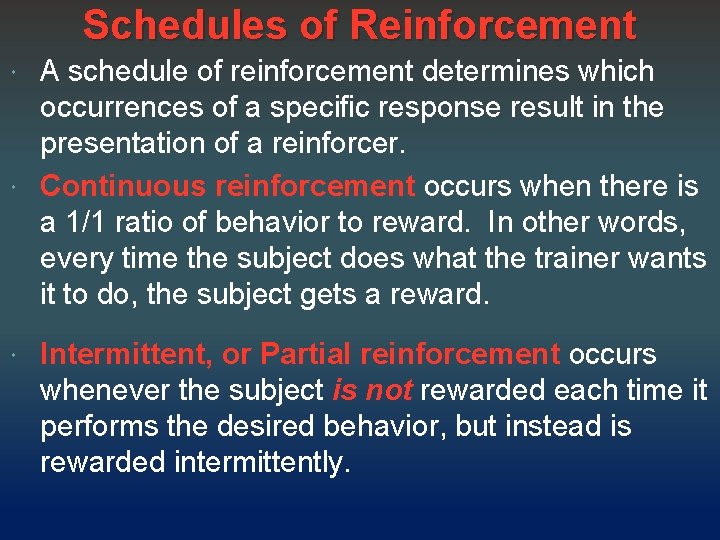

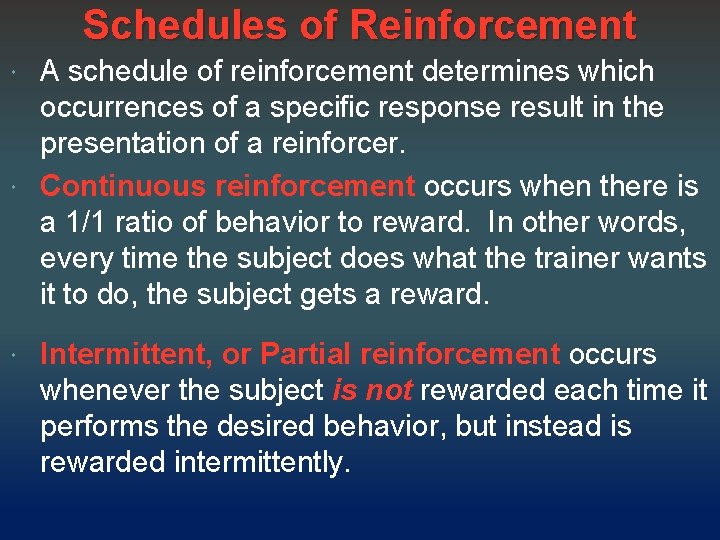

Schedules of Reinforcement A schedule of reinforcement determines which occurrences of a specific response result in the presentation of a reinforcer. Continuous reinforcement occurs when there is a 1/1 ratio of behavior to reward. In other words, every time the subject does what the trainer wants it to do, the subject gets a reward. Intermittent, or Partial reinforcement occurs whenever the subject is not rewarded each time it performs the desired behavior, but instead is rewarded intermittently.

Schedules of Reinforcement ○Fixed Ratio – # of behaviors needed for reward stays constant. ○Variable Ratio - # of behaviors for reward keeps changing ○Fixed Interval – elapsed time for reward stays constant ○Variable Interval - elapsed time for reward keeps changing

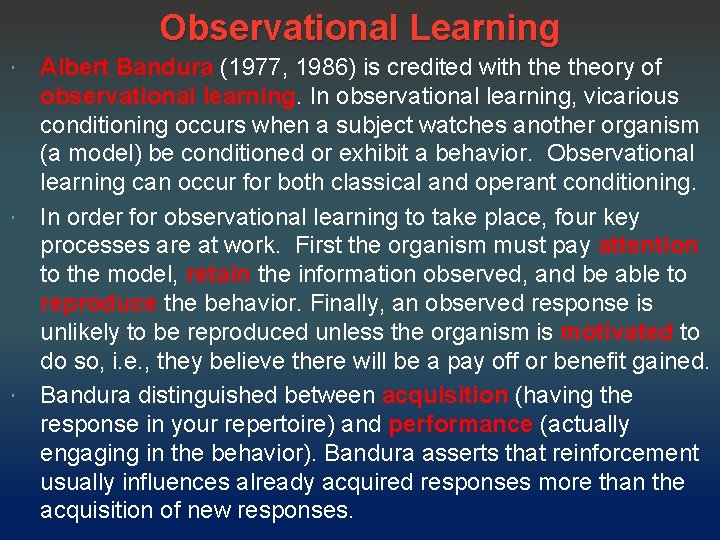

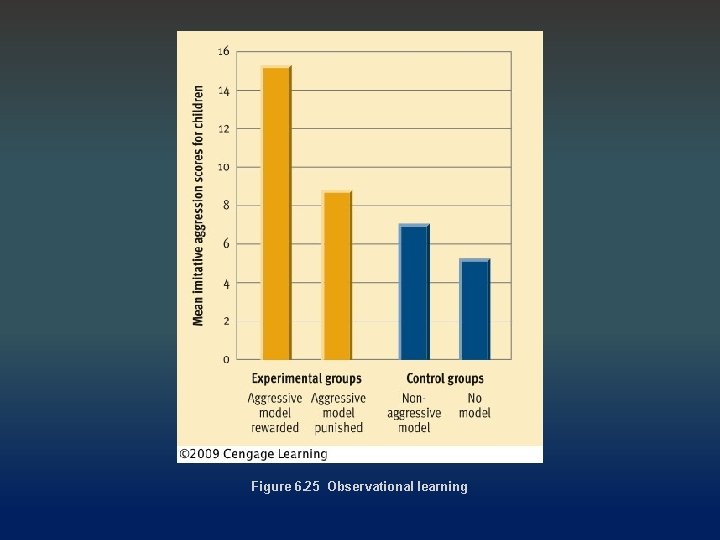

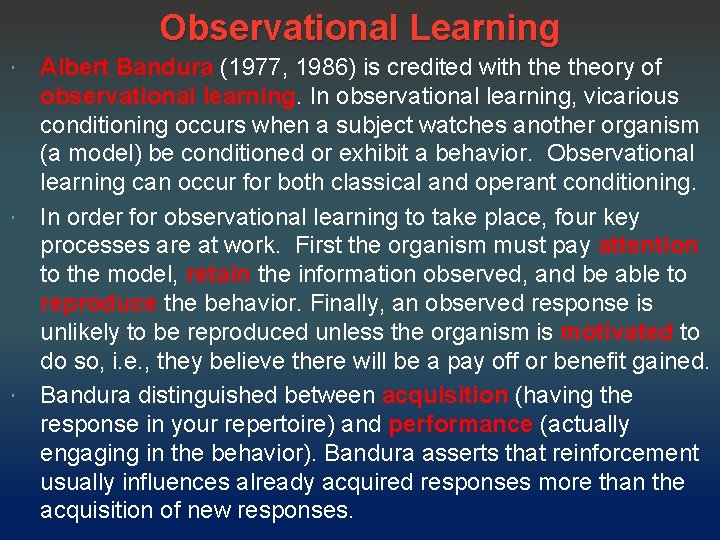

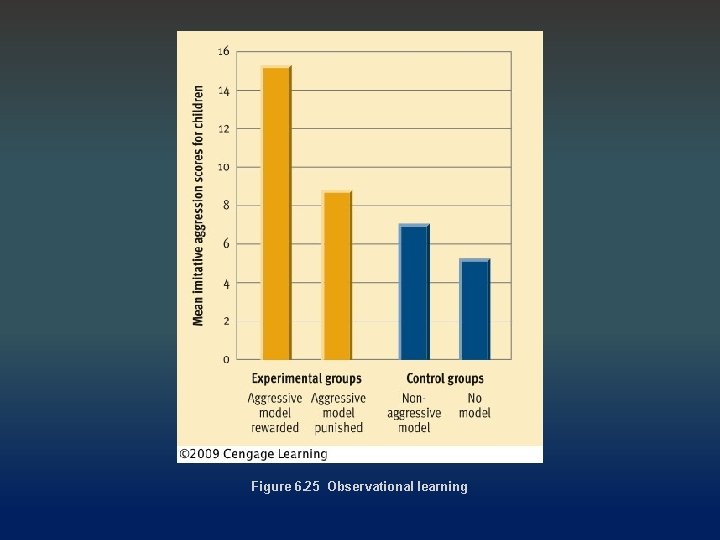

Observational Learning Albert Bandura (1977, 1986) is credited with theory of observational learning. In observational learning, vicarious conditioning occurs when a subject watches another organism (a model) be conditioned or exhibit a behavior. Observational learning can occur for both classical and operant conditioning. In order for observational learning to take place, four key processes are at work. First the organism must pay attention to the model, retain the information observed, and be able to reproduce the behavior. Finally, an observed response is unlikely to be reproduced unless the organism is motivated to do so, i. e. , they believe there will be a pay off or benefit gained. Bandura distinguished between acquisition (having the response in your repertoire) and performance (actually engaging in the behavior). Bandura asserts that reinforcement usually influences already acquired responses more than the acquisition of new responses.

Figure 6. 25 Observational learning

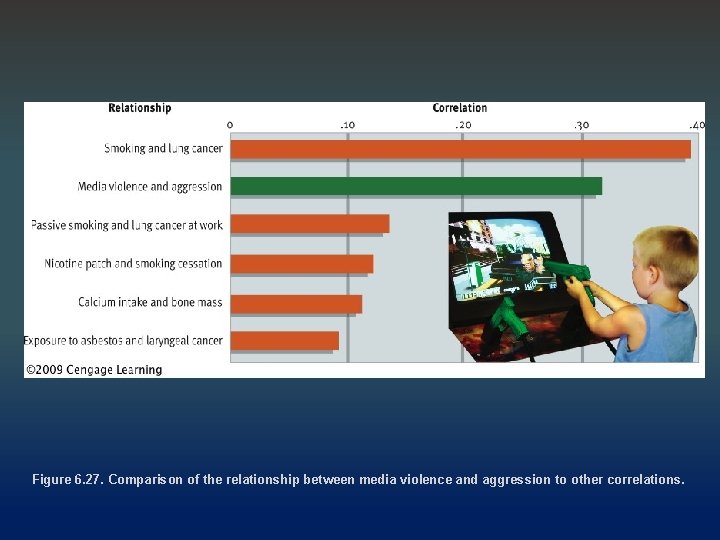

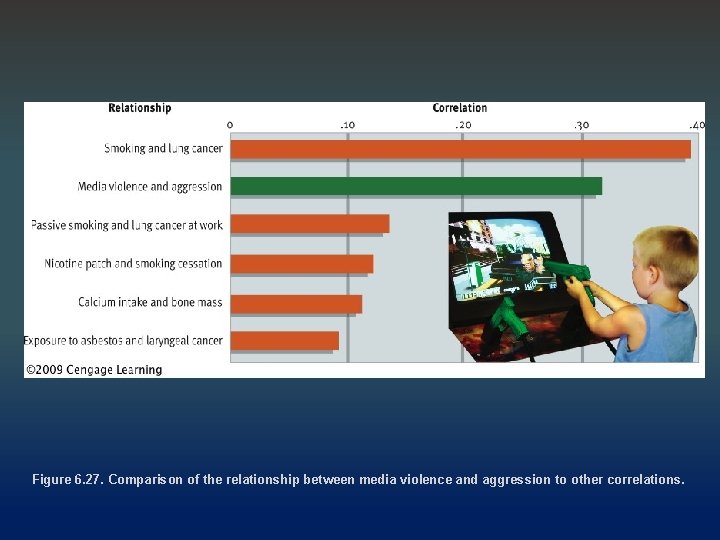

The Media Violence Controversy Studies demonstrate that exposure to TV and movie violence increases the likelihood of physical aggression, verbal aggression, aggressive thoughts, and aggressive emotions. The correlation between media violence and aggression is almost as strong as the correlation between smoking and cancer Thus controlling what movies, TV shows, and video games your child is exposed to can go a long way toward protecting it from developing a violent and aggressive nature.

Figure 6. 27. Comparison of the relationship between media violence and aggression to other correlations.

Cognitive Learning Theory Cognitive learning theories developed in the 1920’s and 1930’s, and continue to be useful to this day. In fact, these theories exerted a primary influence on Albert Bandura’s movement away from traditional S-R Behaviorism and toward a more flexible and eclectic paradigm (Cognitive Behaviorism and Reciprocal Determinism). The two most prominent cognitive learning theorists were the great Gestalt psychologist Wolfgang Kohler and Edward C. (E. C. ) Tolman.

Cognitive Learning Kohler and Insight learning “The Mentality of Apes” and Sultan Demonstrated that learning many times occurs as a “flash of insight’ whereby a subject, w/o any reinforcement, simply figures out the answer to a problem. Tolman’s Latent Learning, his maze and his concept of cognitive maps: Tolman put rats in a maze and timed how quickly they made their way to the finish. After they finished, he put them back at the start and retimed them. With each successive trial, the rat’s times became faster, showing that they learned the maze simply by experiencing it over and over again. Tolman referred to the learning as a development of a “cognitive map”, or mental layout of the environment, which develops naturally, w/o any reinforcement.

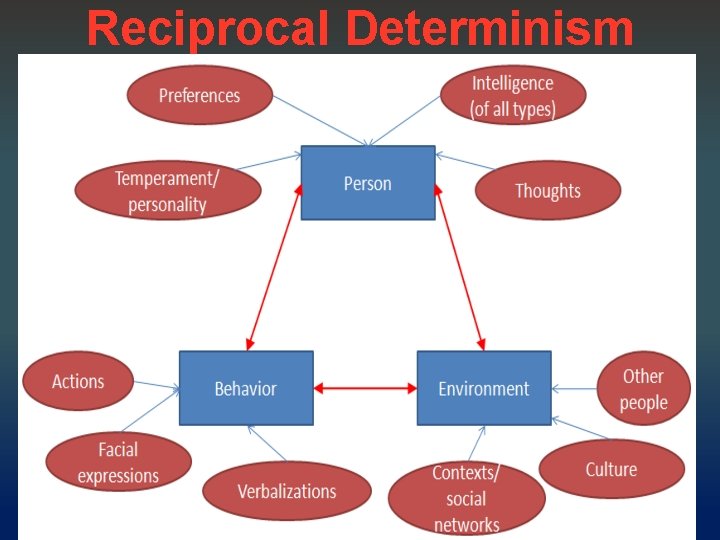

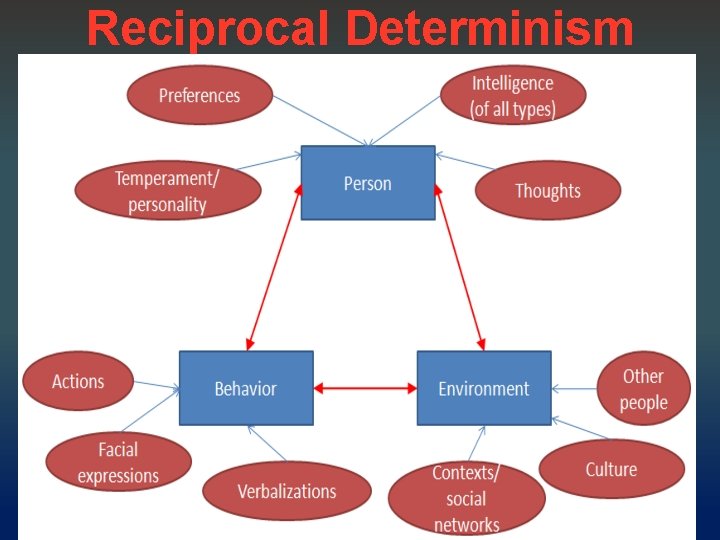

Cognitive Learning Bandura became a Cognitive-Behaviorist, leaving strict behaviorism behind as he evolved academically. His theory of Reciprocal Determinism (aka Triadic Reciprocality) introduced his combining of the two perspectives, and is considered by many to be his most important theory, even if it isn't as well known as his social learning theory. On the next slide is a detailed graphical description of Bandura’s theory of reciprocal determinism.

Reciprocal Determinism

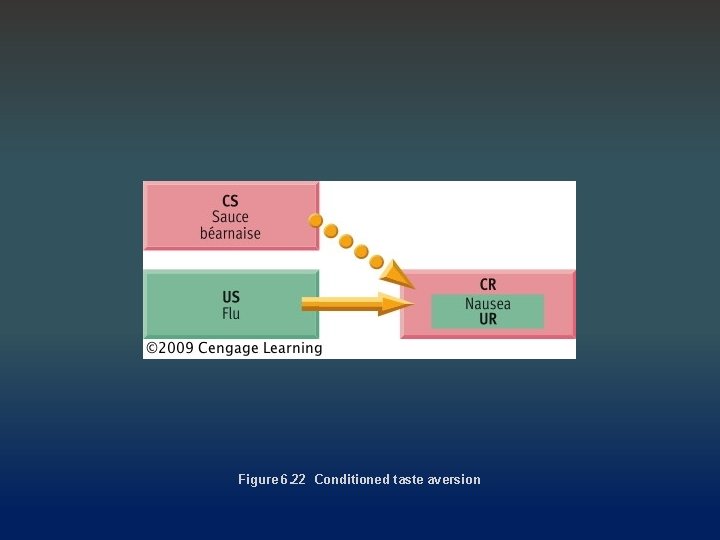

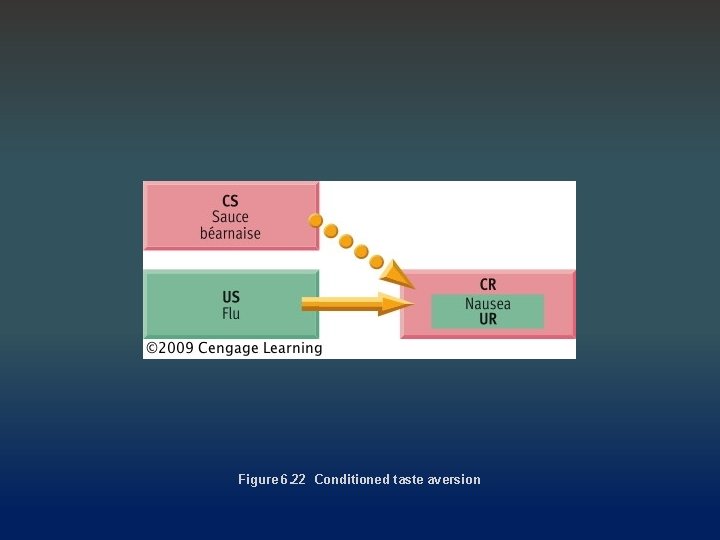

Constraints on Conditioning New research has greatly changed the way we think about conditioning, with both biological and cognitive influences having been discovered. Instinctive Drift occurs when an animal ignores training and drifts back to instinctive behavior (like when a well trained horse sees/smells a wolf, it rears up, throws the rider, and then gallops away). Conditioned Taste Aversion – aka the “Garcia Effect”. Conditioned taste aversions can be readily acquired, after only one trial and when the stimuli are not contiguous (i. e. , becoming ill occurs hours after eating a food), suggesting that there is a biological mechanism at work.

Constraints on Conditioning Martin Seligman has outlined the fact that some phobias are more easily conditioned than others, suggesting the concept of preparedness, ie. that we are biologically prepared to learn to fear objects or events that have inherent danger. Signal relations theory (Rescorla) illustrates that the predictive value of a CS is an influential factor governing classical conditioning. Response-outcome relations - when a response is followed by a desired outcome, it is more easily strengthened if it seems that it caused or predicted the outcome. You study for an exam while listening to Lil Wayne and make an A. But what is strengthened, the potential for you to study or your potential to listen to Lil Wayne?

Figure 6. 22 Conditioned taste aversion